ABSTRACT

Homicide involving multiple victims is relatively rare in England and Wales. When it does occur, mental illness is assumed to have played a significant role. However, reliable evidence to support this is often lacking. We aimed to describe the prevalence of multiple homicide and its subgroups: serial murder, mass murder and familicide and the presence of mental disorder. Data were obtained from the Home Office, HM Court Service, the Police National Computer and NHS Trusts. In England and Wales 470 killed multiple victims between 1997 and 2018. Most did not have evidence of mental health symptoms at the time of offence (85%) or a recorded history of mental disorder (69%). Mental disorder was also not found in most serial homicides (90%), mass murders (94%), or familicides (70%). A tenth of all multiple homicide perpetrators had been under the care of mental health services a year before the incident. This finding challenges commonly held views about mental disorders and the stigma that is perpetuated when multiple-victim homicides occur. Low prevalence and low levels of contact with mental health services make preventing multiple homicide difficult. Reducing violence across society by adopting a multi-agency public health approach is recommended.

Introduction

It has been estimated that 3–4% of homicide incidents involve multiple victims in the United States (US); however, little is known about the prevalence of these incidents in England and Wales as few empirical studies have been undertaken with this population (Fox & Zawitz, Citation2003; Gresswell & Hollin, Citation1994). One of the main difficulties in establishing accurate prevalence has been a lack of consensus in how to define these incidents. Whilst the term multiple-victim homicide is widely accepted to refer to events involving more than one victim, defining crimes such as serial homicide and mass murder has proven to be more problematic. To address this issue for serial homicides, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) convened a panel of experts to synthesise knowledge from law enforcement, mental health and academia (National Centre for the Analysis of Violent Crime NCAVC, Citation2008). The definitions agreed were subsequently widely adopted. Adding to this, Douglas et al. (Citation2013) published a crime classification manual which defined homicide subtypes based on motivation, victimology, type, style and the number of victims and included groupings such as criminal enterprise, extremism, arson/bombing, and personal cause homicide (Douglas et al., Citation2013). These definitions are now commonly used in research and can be seen in . For clarification, the definition for serial ‘murder’ describes a series of two or more victims, which is the most commonly used threshold. Whereas the definition of serial ‘killing’ (three or more victims) has a more limited application. This is primarily used in the US as a criterion to request the involvement of federal law enforcement agencies (Douglas et al., Citation2013).

Table 1. Homicide classification system used by the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) Behavioural Analysis Unit (source: Douglas et al. Citation2013).

A large proportion of research has focused on serial homicide and its subtypes, as opposed to mass murder and other forms of multiple homicide offending (Fox & Levin, Citation2003). Academic attention has focused disproportionately on serial murder motivated by paraphilic interests, but not all serial homicides are sexually motivated. Equating sexual homicide with serial homicide in this way limits the development of research (Petee & Jarvis, Citation2000). Other forms of serial homicide offending, though reported in the media, receive less scientific attention such as homicides in healthcare settings or a domestic context, or within organised crime groups, where power, perceived altruism, or financial gain are the motivators. Although these homicides fall within the FBI definition, they do not fit what is conventionally perceived to be a serial homicide and are often excluded from analyses (Yaksic, Citation2020). There are arguments for an overarching classification incorporating all forms of multiple homicide to strengthen our understanding of the phenomena and improve the comparability and generalisability of the data (Hickey, Citation2002; Petee & Jarvis, Citation2000). However, it is also important to be able to delineate between psychological processes which differentiate these individuals (Yaksic, Citation2020).

The availability of reliable antecedent information is one factor that makes the analysis of psychological characteristics and mental disorders problematic (Dowden, Citation2005). One of the difficulties in eliciting symptoms of emotional distress or mental disorder is the high proportion of perpetrators who immediately take their own life after the incident. Without a mental state examination and access to reliable medical information, assumptions are often made about the perpetrator's mental state in the absence of other explanations (Skeem & Mulvey, Citation2020). Speculation around a perpetrator's state of mind can perpetuate stigma associated with mental illness and violence (Corner et al., Citation2018). Studies have found that the implied association between mental health and mass shootings, for example, has a deleterious effect on attitudes toward people with serious mental illness (McGinty et al., Citation2013; Wilson et al., Citation2016).

The link between mental illness and violence has been extensively researched and it has been established that most people with mental illness are not violent (Elbogen & Johnson, Citation2009; Fazel et al., Citation2009; Swanson et al., Citation1990; Walsh et al., Citation2002). However, few empirical studies on people who commit multiple homicide have used robust clinical data from clinical records to report mental health history. Researchers commonly rely on third-party data sources such as accounts from family, friends, and eyewitnesses to determine mental state at the time leading up to the offence, which are commonly reported in the media (Duwe, Citation2016; Hill et al., Citation2007). There is considerable variation in the prevalence of mental disorders reported in the literature. In mass shooting incidents, for example, Duwe (Citation2016) reported that of 160 people committing a mass shooting, 60% had either been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia or were said to have exhibited symptoms of mental disorder prior to the incident (Duwe, Citation2016). In contrast, Peterson et al. (Citation2022) examined 172 mass shootings in the US and reported that psychosis played a major role in only 11% of the offences and no role in 69% (Peterson et al., Citation2022). Similarly, the US Secret Service’s National Threat Assessment Center analysed 34 homicides that occurred in public or semi-public spaces during 2019 in the US (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2020). Seventeen (46%) had symptoms of mental illness prior to the incident, including psychosis, depression, suicidal thoughts and aggression. Twelve (32%) had been diagnosed with a mental health disorder or had previously received treatment any time since childhood to within months of the offence (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2020). However, almost 70% had not been diagnosed or treated for a mental disorder. In a recent synthesis of the literature, Skeem & Mulvey (Citation2020) concluded that there appears to be a modest link between serious mental illness and mass violence, but this was not as strong as often portrayed (Skeem & Mulvey, Citation2020). Similar variations in mental health prevalence rates have been reported in studies of serial homicide. (Mullen, Citation2004; NCAVC, Citation2008).

The first aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of multiple homicide in England and Wales and the subgroups of serial murder, mass homicide and familicide. The second aim was to examine the presence of mental disorder in those who commit multiple homicide.

Method

Study design

A cross-sectional study describing the statistical differences between multiple-victim homicide using data from the Home Office in England and Wales.

Definitions

The current study has defined multiple homicide as an incident where a person killed two or more victims. The objective of this study was to describe the characteristics of individual perpetrators, not individual events. We adopted the Douglas et al.’s (Citation2013) classification for all forms of multiple homicide, serial murder, and mass murder as presented in (Douglas et al., Citation2013). Malmquist (Citation1980) defined familicide as more than one family member being killed by another family member, which is the definition adopted in this study (Malmquist, Citation1980). These incidents typically involve victims who were a spouse/partner/ex-spouse/partner, sons and daughters (including step and adopted children), siblings, parents, and other relatives. Relationship difficulties, financial and mental health problems are common features in these incidents (Karlsson et al., Citation2021). Recent research to develop typologies of intra-familial homicide provides a useful conceptual framework which can be used to further our understanding of this phenomenon (Cullen & Fritzon, Citation2019).

Classifying multiple homicide

Within the group of people who committed multiple homicide, there were several individuals whose offences fell into more than one classification. Douglas et al. (Citation2013) described an example where domestic homicides such as familicides can also be classified as mass murders or serial murder. For example, in a familicide involving the deaths of two or more familial victims, if the deaths occurred in separate events, separated by a period of time, by definition they could also be classed as serial homicides. Similarly, if the victims numbered four or more and they occurred in a single incident these could also be considered mass murders. Thirteen people who committed mass homicide and six committing serial homicide met the criteria for familicide, with most of the victims being family members. As the features of these incidents more closely resembled familicide, the authors SF and SI agreed to categorise these cases accordingly. The same crossover can occur between other types of homicide, such as filicide (the killing of a child/children by parents). There were three spree killers; these have been combined with the mass murder group in this analysis, as the number was too small to analyse as a separate group.

Setting

Multiple homicide in this study refers to incidents occurring in England and Wales between 1997 and 2018. Due to a change in The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health (NCISH) remit in 2018, clinical data were only obtained up to 2016. NCISH no longer compiles detailed patient homicide data. This study therefore utilised the most up-to-date clinical dataset available.

Inclusion criteria

The main eligibility criteria for this study were people convicted of homicide, which is murder, manslaughter, and infanticide. People found not guilty by reason of insanity or unfit to plead were also included. We also included people who took their own life within 3 days of the offence. As these homicide-suicide suspects were not convicted, these perpetrators were selected by date of offence occurring between 1 January 1997 and 31 December 2018 to align with the convicted perpetrators’ offence dates. Data collection in this study started in 1997, as this was the first full year that data were available from NCISH. Where incidents involved co-accused, all perpetrators were included in the analysis. The age of criminal responsibility in England and Wales is 10 years old.

Participants

Four hundred and seventy were identified as committing multiple homicide in England and Wales between 1 January 1997 and 31 December 2018.

Data collection

Data were obtained from The Home Office Statistics Unit of Home Office Science (Homicide Index), His Majesty’s Court Service, National Health Service (NHS Trusts) and Greater Manchester Police (GMP). The Homicide Index records all suspected homicides in England and Wales. It contains variables on the victim’s and suspect’s characteristics, the offence, and court outcome. Sex was recorded in the data obtained from the above sources.

The individual’s mental health history was established by two methods. First, NCISH contacted NHS Trusts to determine if the person had been under the care of mental health services prior to the offence. NCISH’s response rate from NHS Trusts has been shown to be high (95%) (National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness NCISH, Citation2013). NHS Trusts provided information on 371 of 376 (99%) between 1997 and 2016, confirming contact with mental health services and providing clinical data on 74 (20%) individuals. It is acknowledged this approach to defining mental health history may result in an underestimation due to issues with individuals being able to access services or seek support. To address this, we also obtained psychiatric reports from HM Court service for all those who received a pre-trial psychiatric assessment, 142 (37%). Psychiatric reports provided information on mental state at the time of the offence. Not all individuals who underwent a psychiatric assessment had a mental disorder. In total, combining data from NHS Trusts and psychiatric reports, we identified and obtained clinical information on 143 (38%) people who committed multiple homicide between 1997 and 2016.

We acknowledge that the data presented on mental disorders may not capture all those with mental health conditions at the time of the offence. The use of HM Court service, NCISH, and NHS trusts is reliant on people receiving an assessment or treatment for a mental health condition from secondary care services. Whilst this method is arguably one of the most robust approaches for determining mental disorder, the true prevalence rates of mental disorders may still be under-reported.

Finally, for each individual, GMP provided NCISH with a record of previous criminal offences, extracted from the Police National Computer. NCISH datasets of people convicted of homicide and suspected of homicide-suicide were merged. New variables identifying multiple homicide, serial, mass and familicide were created.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented as frequency counts and proportions with 95% confidence intervals. The mean and standard deviation were provided for age. We compared the characteristics of individuals who committed serial murder, mass murder and familicide using Pearson’s chi-square tests, Fisher’s Exact tests adjustments were applied where cell counts were < 5. Chi square tests were also conducted to explore features of familicide cases as the number of individuals in this classification was larger than other groups. If data were missing for a variable, the case was removed from the analysis. Therefore, the denominator is the number of valid cases. Furthermore, clinical data were only available for years 1997–2016, and the denominator does not include cases from 2017 to 2018 for this analysis. As the denominator may vary from variable to variable, the N for denominators were provided in tables for further clarity and to aid transparency. Values <3 have not been presented.

Ethical considerations

The study received ethical approval from the North West Research Ethical Committee (ERP/96/136), Health Research Authority Confidential Advisory Group (HRA-CAG), and is registered under the Data Protection Act (2018).

Results

Multiple homicide perpetrator characteristics

Of the total number of people who committed homicide between 1997 and 2018, 470 (4%) killed more than one person. Most were male (419, 89%) with a mean age of 33 (SD = 11.86, range 13–82). Seventy-two (15%) took their own lives following the incident. A sharp instrument (150, 33%) and fire setting (90, 20%) were the most common methods used. Almost two-thirds had previous convictions (201 of 324, 62%). One hundred and thirty-six (31%) had a history of violence. There was no evidence of symptoms of mental illness at the time of the offence (319/376, 85%) or a lifetime history of mental disorders in most individuals (258/376, 69%). For those with a mental health diagnosis, this was recorded as schizophrenia or other delusional disorder in 38/376, (10%) or personality disorder (28/376, 7%). Few had clinical diagnoses of alcohol dependence/misuse (9/376, 2%) or drug dependence/misuse (7/376, 2%). A tenth had been mental health patients in contact with mental health services within 12 months of the offence (44/376, 12%).

shows the number of people who committed multiple homicide and the number of victims per multiple homicide incident. The majority killed two people; the highest number of victims recorded in a single incident was 58.

Table 2. Number of all homicide perpetrators and victims.

Serial homicide

Of the 41 people committing a serial homicide, 95% were male. The mean age was 32 years. Half had a previous history of violence. Most killed two victims (33, 80%), eight killed three or more (20%), with the highest number being 15. It is likely that the true number of victims is underestimated, as this data is based on recorded convictions, as opposed to ‘suspected’ victims of homicide.

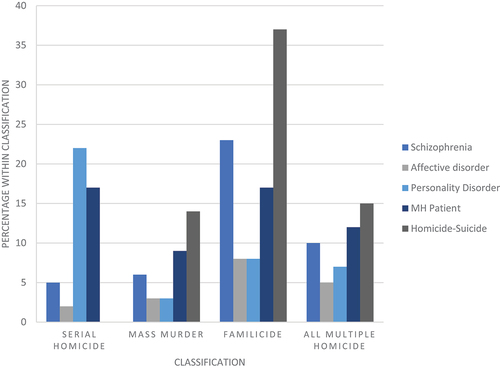

There was a total of 103 victims, over half were female (52, 50%). The most common relationship for victims was friend or acquaintance (48, 47%) followed by strangers (25, 24%) and 11 (10%) were sex workers. The most common method of homicide used by individual perpetrators was a sharp instrument (8, 20%). Twenty-four (59%) had no diagnosed lifetime history of mental disorder. Of those with a mental health diagnosis, personality disorder, and schizophrenia or other delusional disorder were most common (). Almost a fifth (17%) had contact with mental health services in the year before the first offence ().

Table 3. Descriptive characteristics of multiple homicide typologies.

Mass murder

Forty-four people were classified as mass murderers, having killed four or more people in a single incident, including 3 spree killings. Most were male (93%), the mean age was 29 years. Over 40% had a history of previous violence. Of the 324 victims, 55% were male and 78% most strangers. The number of victims ranged from 4 to 58. The circumstances of these incidents varied and included deliberate fire setting in a domestic context, terrorist attacks, and human trafficking. Almost a third of the victims died as a result of arson (96, 30%), 89 (27%) died following an explosion. Most did not have any known symptoms of mental illness at the time of the offence, and over three-quarters had no diagnosed lifetime history of mental disorder (). Few had been in contact with mental health services a year before the offence (9%). Around 14% took their own life following the incident. Where a diagnosis had been made, schizophrenia or other delusional disorder, affective disorder and personality disorder were reported ().

Familicide

One hundred and sixty-eight incidents were categorised as familicides, involving the deaths of two or more family members. Most familicides were committed by males (78%). The mean age was 37 years (SD 11.79). A fifth had a previous history of violence. There were 413 victims, of which half were the perpetrator’s child/children (208, 50%) and a fifth were a spouse/partner/ex (80, 19%). Perpetrators who killed their children were more likely to be mothers rather than fathers (84% v 42%, X (Gresswell & Hollin, Citation1994) (1) = 20.175, p < 0.001). Those who killed their spouse/partner/ex were more likely to be males compared to females (24% v 5%, X (Gresswell & Hollin, Citation1994) (1) = 6.467, p < 0.011). The number of victims killed in familicide incidents ranged from 2 to 12. Sharp instruments were the most common method, followed by arson. The majority were not known to have mental illness at the time of the offence. Half had no diagnosed lifetime history of mental disorders. Of those that had a diagnosis, this was most commonly schizophrenia or other delusional disorder. Almost a fifth had been in contact with mental health services within a year of the offence (). Sixty-two (37%) took their own lives after the homicide ().

shows results of chi-square tests comparing the differences between serial homicide, mass murder and familicide. The numbers are small and should be interpreted cautiously. There were significant differences in the demographic characteristics with people who committed familicide being older and less likely to be men. Personality disorder was more likely in serial homicide and schizophrenia and other delusional disorder was more likely to be diagnosed in familicide. Sharp instruments were most commonly used in familicide, whereas arson was more likely in mass murder incidents.

We also performed a chi-square test to compare the characteristics of serial homicides directly with mass murder. The numbers in these groups can be seen in . We found that people who committed serial homicide were more likely to have personality disorder (p = 0.020), evidence of previous mental illness (p = 0.017), to have killed an acquaintance (p < 0.004), and used sharp instruments (p = 0.03); or poisoning (p < 0.01). Victims of mass homicide incidents were more likely to be strangers (p < 0.01) compared to victims of serial homicide. Arson was also more common in mass homicide (p < 0.01).

Almost half of the incidents of multiple-victim homicide did not meet the criteria for serial murder, mass murder or familicide (217, 46%), the majority of these were double homicides (191, 88%). Where information was known on the relationship to the victims (n = 461), most were friends/social acquaintances (153, 33%) or strangers (117, 25%). In two-thirds of these incidents, the victims were male (299, 65%). The method of homicide was most frequently a sharp instrument (156, 34%) followed by arson (112, 24%) and firearms (79, 17%). The limited data available suggests these homicides were domestic incidents (19 of 123, 15%), long-running disputes (15 of 123; 12%) or occurred during other crimes (12 of 123; 10%). Twenty-one (10%) had recorded symptoms of mental illness at the time of offence, 17 (8%) had been under the care of mental health services within a year of the offence.

Discussion

The current study had two aims. First, to determine the prevalence of multiple homicide in England and Wales. Second, to examine the presence of mental disorders in those who commit multiple homicide. With respect to the first aim, the results of the study showed that 4% of the homicides in England and Wales between 1997 and 2018 led to the deaths of multiple victims. This information has not been officially reported by the Office for National Statistics annual homicide statistics (Office for National Statistics ONS, Citation2023), and therefore our findings make a valuable contribution to the literature. These findings are important as they demonstrate that the proportion of homicides involving multiple victims is similar in England and Wales to the estimates reported in the US (3–4%) and other European countries (Fox & Zawitz, Citation2003; Thomsen et al., Citation2019). We find that the main socio-demographic characteristics of multiple homicide perpetrators correspond with previous research, i.e. being male and aged 30–40 years. 30 Victims were mostly strangers, which is largely skewed by the mass murder group. Over a third of the incidents involved family members. While the proportion of incidents is similar to other countries, further exploration of the circumstances of these incidents is needed. Almost half of the multiple homicides did not fit the definitions of serial murder, mass murder or familicide. They were most often double homicides that were committed in the same location at the same time, and the victims were most often acquaintances or strangers, consistent with previous research (DeLisi & Scherer, Citation2006). Further research investigating the context of these incidents is needed to deepen our understanding of the psychological processes that underpin these acts.

For the second aim, overall, we found that few people who killed multiple victims had evidence of mental health problems at the time of the offence (15%). A higher proportion had previously experienced difficulties with their mental health over the course of their lifetime (31%). Our findings also showed that 88% of those who committed multiple homicide had not been in contact with mental health services within the year before the offence. These figures correspond with the known proportion of mental disorder in people who killed single victims (Flynn et al., Citation2011, Citation2021). Similarly, within each featured group, most of the perpetrators had no recorded symptoms of mental illness at the time of the offence (90% of the serial homicide group, 94% of mass murder group, and 70% of familicides).

When we compared the characteristics of each of these groups, we found schizophrenia was most common in people who committed familicide, whereas there was a higher prevalence of personality disorder in serial homicide perpetrators. In mass homicide cases, victims were more likely to be strangers, and arson was common.

This is an important anti-stigma message as the results provide evidence which challenges the public perception of these incidents. Adding to the findings of Skeem & Mulvey (Citation2020), our study shows mental disorders have an important but modest link to extreme violence, which is not a prominent feature in most multiple homicides in England and Wales. Equally, we agree with the report of the National Council for Behavioral Health (Citation2019) that the emotional and mental distress which often underlie these acts is different from mental disorders (National Council for Behavioral Health, Citation2019). Previous research has shown difficulties with interpersonal or work relationships, with individuals harbouring grievances, feeling disconnected, lonely and isolated, having suicidal ideation and a desire for attention (Capellan et al., Citation2019; Lankford, Citation2018; Mullen, Citation2004). Indeed, studies have shown that there may be warning signs where intervention is possible, as in most cases these acts are premeditated (Lankford, Citation2018; Reid Meloy et al., Citation2012). The role of substance misuse has also been underreached as we know that co-morbid drug and alcohol use can elevate the risk of violent behaviour (Fazel et al., Citation2009).

Implications for researchers and clinicians

The findings must be interpreted cautiously, as the overall number of people with a psychiatric diagnosis who committed multiple homicide was small.

Multiple homicides are rare, and they are difficult to predict because the characteristics of people who perpetrate these acts are common to many people in the general population. With low prevalence rates and few people known to mental health services, it would be unrealistic to suggest that a single clinical intervention could prevent multiple homicide. Recently, the UK government has implemented a public health strategy aimed at addressing violence following the success of Violence Reduction Units (VRUs) in Scotland. Since VRUs were established over a decade ago, there has been a significant reduction in violent crime and knife possession (CitationHome Office). Although the introduction of VRUs was not the only reason for reduction in violence in Scotland as there has been a downward trend for some time, they have nonetheless played an important role. Eighteen VRUs have been established in England and Wales. Although no statistically significant reduction in homicides has been reported to date, there was an impact on police recorded violent crime (CitationHome Office).

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first to our knowledge to examine a national cohort of multiple homicide in England and Wales, with a specific focus on the mental health of perpetrators. However, there are several limitations that should be considered. Firstly, the descriptive design means we cannot establish causality. Second, due to a change in NCISH’s remit, clinical data identifying contact with mental health services within 12 months of the offence were unavailable for the final 2 years of the study period. Third, the sample used in this research could be criticised for being over-inclusive, for example, adopting the definition of serial homicide recommended by the FBI of two or more victims. Fourth, low incidents of multiple homicide, particularly mass murder and serial homicide in England and Wales, makes it difficult to perform advanced analysis and draw statistical conclusions. Finally, using contact with mental health services as a measure of mental disorder, even with the addition of psychiatric court assessments, will likely underestimate rates of mental disorder. It is therefore a common problem that mental disorder will often go unreported and diagnoses such as personality disorder and substance dependence and misuse may be underestimated.

Conclusion

In recent decades, serial homicide and mass murder, particularly school shootings in the US have attracted increasing media attention. However, this phenomenon still lacks reliable empirical research. Our study aimed to address the gap in our current understanding from a European perspective, by providing accurate prevalence rates and reporting on the mental health. With these reliable data we challenge the narrative that mental disorder is a major factor in these offences, as our data shows that it is not. Responsible reporting of multiple homicides in the media is also essential to avoid misunderstandings and prevent stigma, as people with mental illness are more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators. While mental disorder was shown to be a factor in a quarter of these incidents, for most people who commit these acts little evidence of mental disorder was found and only one-tenth were known to mental health services. As these incidents are rare, prevention for clinicians is challenging. Therefore, further research is needed to increase our understanding of the factors that underpin extreme violence and to evaluate the effectiveness of the recently established Violence Reduction Units.

Role of the study sponsor

The study was sponsored by the University of Manchester, which has insurance policies in place to cover design, management, and conduct of the research.

Data sharing

The data collected for the study will not be made available to others. Data from this study cannot be shared because of information governance restrictions in place to protect confidentiality. Access to data can be requested via application to the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (www.hqip.org.uk/national-programmes/accessing-ncapop-data/). The study protocol, statistical analysis plan, and analytic code are available on request from the corresponding author.

Authors and contributors

All authors were responsible and accountable for all parts of the work related to the study. SF and JS conceived the study. SF, SI, JS contributed to the design of the study. SF SGT and SI directly accessed and verified the underlying data reported in the manuscript. SF was responsible for the analysis. All authors had full access to all the data, interpreted the data, contributed to writing and revision of the manuscript, and accept responsibility to submit for publication.

Acknowledgements

The study was carried out as part of the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health. We acknowledge the help of the administrative staff in NHS Trusts, HM Crown Courts and Greater Manchester Police who helped with the NCISH processes and the clinicians who completed the questionnaires. We are grateful for the work of current staff at NCISH (in addition to the authors): Alison Baird, James Burns, Jane Graney, Isabelle M Hunt, Lana Bojanic, Rebecca Lowe, Pauline Rivart, Cathryn Rodway, Philip Stones. The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health is currently commissioned by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) on behalf of the four UK governments and the States of Jersey and Guernsey.

Disclosure statement

NK works with NHS England on national quality improvement initiatives for suicide and self-harm and sits on the Department of Health and Social Care’s National Suicide Prevention Strategy Advisory Group for England. LA is Chair, National Suicide Prevention Strategy Advisory Group, DHSC.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Capellan, J. A., Johnson, J., Porter, J. R., & Martin, C. (2019). Disaggregating mass public shootings: A comparative analysis of disgruntled employee, school, ideologically motivated, and rampage shooters. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 64(3), 814–823. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.13985

- Corner, E., Gill, P., Schouten, R., & Farnham, F. (2018). Mental disorders, personality traits, and grievance-fueled targeted violence: The evidence base and implications for research and practice. Journal of Personality Assessment, 100(5), 459–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2018.1475392

- Cullen, D., & Fritzon, K. (2019). A typology of familicide perpetrators in Australia. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 26(6), 970–988. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2019.1664276

- DeLisi, M., & Scherer, A. M. (2006). Multiple homicide offenders: Offense characteristics, social correlates, and criminal careers. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 33(3), 367–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854806286193

- Douglas, J. E., Burgess, A. W., Burgess, A. G., & Ressler, R. K. (2013). Crime classification manual: A standard system for investigating and classifying violent crime. John Wiley & Sons.

- Dowden, C. (2005). Research on multiple murder: Where are we in the state of the art. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 20(2), 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02852650

- Duwe, G. (2016). The patterns and prevalence of mass public shootings in the United States, 1915–2013. The Wiley Handbook of the Psychology of Mass Shootings, 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119048015.ch2

- Elbogen, E. B., & Johnson, S. C. (2009). The intricate link between violence and mental disorder: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(2), 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.537

- Fazel, S., Gulati, G., Linsell, L., Geddes, J. R., Grann, M., & McGrath, J. (2009). Schizophrenia and violence: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine, 6(8), e1000120. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000120

- Flynn, S., Abel, K. M., While, D., Mehta, H., & Shaw, J. (2011). Mental illness, gender and homicide: A population-based descriptive study. Psychiatry Research, 185(3), 368–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2010.07.040

- Flynn, S., Ibrahim, S., Kapur, N., Appleby, L., & Shaw, J. (2021). Mental disorder in people convicted of homicide: Long-term national trends in rates and court outcome. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 218(4), 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.94

- Fox, J. A., & Levin, J. (2003). Mass murder: An analysis of extreme violence. Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 5(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021051002020

- Fox, J. A., & Zawitz, M. W. (2003). Homicide trends in the United States: 2000 update. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- Gresswell, D. M., & Hollin, C. R. (1994). Multiple murder: A review. The British Journal of Criminology, 34(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a048379

- Hickey, E. W. (2002). Serial murderers and their victims (p. 448). Wadsworth Pub.

- Hill, A., Habermann, N., Berner, W., & Briken, P. (2007). Psychiatric disorders in single and multiple sexual murderers. Psychopathology, 40(1), 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1159/000096386

- Home Office. Violence reduction unit year ending March 2021 evaluation report. 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/violence-reduction-unit-year-ending-march-2021-evaluation-report/violence-reduction-unit-year-ending-march-2021-evaluation-report#vru-design-focus-and-models-of-working

- Karlsson, L. C., Antfolk, J., Putkonen, H., Amon, S., da Silva Guerreiro, J., de Vogel, V., Flynn, S., & Weizmann-Henelius, G. (2021). Familicide: A systematic literature review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(1), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018821955

- Lankford, A. (2018). Identifying potential mass shooters and suicide terrorists with warning signs of suicide, perceived victimization, and desires for attention or fame. Journal of Personality Assessment, 100(5), 471–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2018.1436063

- Malmquist, C. P. (1980). Psychiatric aspects of familicide. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online, 8(3), 298–304.

- McGinty, E. E., Webster, D. W., & Barry, C. L. (2013). Effects of news media messages about mass shootings on attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness and public support for gun control policies. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(5), 494–501. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13010014

- Mullen, P. E. (2004). The autogenic (self‐generated) massacre. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 22(3), 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.564

- National Centre for the Analysis of Violent Crime (NCAVC). (2008. Serial murder: Multi-disciplinary perspectives for investigators. https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/serial-murder-multi-disciplinary-perspectives-investigators

- National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness (NCISH). (2013). Annual report. July. 2013. https://documents.manchester.ac.uk/display.aspx?DocID=37595:

- National Council for Behavioral Health. (2019, August). Mass violence in America. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Mass-Violence-in-America_8-6-19.pdf

- National Threat Assessment Center. (2020. Mass attacks in public spaces - 2019. U.S. Secret Service, Department of Homeland Security. https://www.secretservice.gov/sites/default/files/reports/2020-09/MAPS2019.pdf

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2023, March). ONS website, article, homicide in england and wales: Year ending. Retrived February 8, 2024, from file://nask.man.ac.uk/home$/Downloads/Homicide%20in%20England%20and%20Wales%20year%20ending%20March%202023.pdf

- Petee, T. A., & Jarvis, J. (2000). Analyzing violent serial offending: Guest editors’ introduction. Homicide Studies, 4(3), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767900004003001

- Peterson, J. K., Densley, J. A., Knapp, K., Higgins, S., & Jensen, A. (2022). Psychosis and mass shootings: A systematic examination using publicly available data. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 28(2), 280. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000314

- Reid Meloy, J., Hoffmann, J., Guldimann, A., & James, D. (2012). The role of warning behaviors in threat assessment: An exploration and suggested typology. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 30(3), 256–279. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.999

- Skeem, J., & Mulvey, E. (2020). What role does serious mental illness play in mass shootings, and how should we address it? Criminology & Public Policy, 19(1), 85–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12473

- Sturup, J. (2018). Comparing serial homicides to single homicides: A study of prevalence, offender, and offence characteristics in Sweden. The Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 15(2), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1500

- Swanson, J. W., Holzer, C. E., III, Ganju, V. K., & Jono, R. T. (1990). Violence and psychiatric disorder in the community: Evidence from the epidemiologic catchment area surveys. Psychiatric Services, 41(7), 761–770. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.41.7.761

- Thomsen, A. H., Leth, P. M., Hougen, H. P., Villesen, P., & Brink, O. (2019). Homicide in Denmark 1992–2016. Forensic Science International: Synergy, 1, 275–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsisyn.2019.07.001

- Walsh, E., Buchanan, A., & Fahy, T. (2002). Violence and schizophrenia: Examining the evidence. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(6), 490–495. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.180.6.490

- Wilson, L. C., Ballman, A. D., & Buczek, T. J. (2016). News content about mass shootings and attitudes toward mental illness. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 93(3), 644–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699015610064

- Yaksic, E. (2020). Addressing the challenges and limitations of utilizing data to study serial homicide. In D. Canter & D. Youngs (Eds.), Reviewing crime psychology (pp. 353–379). Routledge.