ABSTRACT

Professionals working in international companies in Sweden are expected to speak, read, and write in Swedish and English in their daily work. This article discusses professional writing in different languages. Through the use of methods from linguistic ethnography, we aim to enrich the understanding of workplace literacy by studying writing and texts in multilingual business contexts. Our results show that professionals are expected to navigate between a translanguaging mode and a more monolingual mode in everyday communication. Also, when they opt for producing monolingual texts, literacy practices that surround those texts are often multilingual. Moreover, they imagine a future, secondary audience for their texts, often resulting in the choice of English for reaching out, or in the choice of Swedish as a way of keeping matters local. Knowing when to choose a translanguaging mode or a more monolingual mode is a necessary skill or competence in this type of workplace. Our results also show that the use of multimodal resources includes the material placement of texts, and that old materialities such as pen and paper are still essential. Different linguistic and semiotic resources are used, including resources from academic, business and personal discourse.

Introduction

Today work life is often mobile, multilingual and complex. Professionals working in international companies in Sweden are expected to speak, read, and write in at least Swedish and English in their daily work. They attend meetings where both languages are used in writing and in speech; they read different sources in both languages; and they write notes, professional documents and emails in both languages. In this article the mosaic of writing in different languages, using different modalities, is discussed.

During the last years, common perceptions about communication and language have been revised. This has led to a move away from starting assumptions such as ‘homogeneity, stability and boundedness’ (Blommaert & Rampton, Citation2011, p. 3) and towards a view of ‘mobility, mixing, political dynamics and historical embedding’ (Blommaert & Rampton, Citation2011). In modern white-collar workplaces, communication is often characterised by the use of different discourses (e.g. professional and private), different modes (e.g. images, verbal language), different genres (e.g. PowerPoint presentations) and different media (e.g. paper documents, digital tools).

Previous research has examined workplace writing and literacy, language choice and multilingualism in writing (Angouri & Miglbauer, Citation2014; Incelli, Citation2013; Kankaanranta, Citation2006), revealing how writers target texts to different audiences (Brown & Herndl, Citation1986; McNely, Citation2019), and the role of digital media (Darics, Citation2017; Golden & Geisler, Citation2007). However, research has tended to focus on either texts as artifacts, or on meetings and oral communication, thus disregarding the role of texts as embedded in meetings and communication. In this article, we aim to enrich the understanding of workplace literacy by taking a multimodal literacy practices perspective, studying writing and texts within the flow of specific workplace communication. Through linguistic ethnography we have access not only to texts but also to the complex literacy practices that surround them.

The article begins with an outline of theoretical perspectives which inform the study. Afterwards, our methodology, data and analytical framework are discussed, followed by descriptions of companies and key participants. Thereafter, overall results are presented with different texts and key participants discussed in relation to literacy practices. Our analysis attends to the ways in which these participants engage in multilingual and multimodal writing as part of their daily work practices. We highlight how they shift between monolingual and translanguaging modes, and consider both current and future audiences arguing that the ability to translanguage in several domains is a necessity in these workplace settings.

Conceptualising literacy practices in the workplace

In our analysis of workplace texts, and in relating texts to literacy practices, we draw on the theoretical concepts of linguistic repertoires (Busch, Citation2012; Gumperz, Citation1964), literacy practices (Barton et al., Citation2000), multimodality (Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2001), materiality (Björkvall & Karlsson, Citation2011), translanguaging (García & Li Wei, Citation2014) and translanguaging space (Li Wei, Citation2011). A person’s linguistic repertoire can include languages, dialects, registers (Busch, Citation2012), words/expressions in different languages (cf. ‘linguistic features’, Jørgensen, Citation2008), signs, and emoticons. The concept of repertoire opens up for viewing a person’s linguistic and semiotic resources as ‘a whole’ (Busch, Citation2012, p. 521), regardless of the status of the different languages involved. It also moves away from a view of languages as bounded entities, similar to the concept of translanguaging (see also Räisänen, Citation2018), discussed below. The concept of linguistic repertoire has typically included multimodal resources, such as gesture, expression and social semiotics, often referred to as an individual’s communicative repertoire (Rymes, Citation2014). Professionals in this study make use of their linguistic repertoires in their daily work life as they speak, read, and write in at least two languages, often drawing upon other linguistic and semiotic resources.

An important modality or resource in our workplace setting is writing. Literacy practices are ‘the general cultural ways of utilising written language which people draw upon in their lives’ (Barton et al., Citation2000, p. 7). These practices are linked to ‘social structures, institutional conventions, and relations of power’ (Martin-Jones et al., Citation2009, p. 46) and are developed over time to achieve different social goals now and in the future (Tusting Citation2000). Social structures linked to literacy practices concern who is included or excluded from certain discourses or from specific terminology (Lillis & Curry Citation2013). In other words, literacy practices are also social practices. As we are interested in the social roles of languages and multimodality in writing, this concept is relevant to our analysis. Time, social goals of literacy practices, and inclusion/exclusion are also relevant issues to examine in their social contexts.

Research into the multimodality of human communication has grown in the era of digital communication. When first introduced, multimodal analyses mainly focused on young people and school settings (e.g. Kress, Citation2010). More recent studies have also covered professional settings, showing how organisations attempt to control the actions of readers of certain texts, e.g. Ledin & Machin (Citation2015) on academic management, and Höllerer et al. (Citation2019) on how Corporate Social Responsibility is multimodally legitimised in relation to business stakeholders. Thurlow and Jaworski (e.g. Citation2012) have directed attention to multimodal communication in high status and elite settings. Inspired by such studies, we turn attention to the emic perspectives of high status professionals who produce texts as part of their everyday work processes. We apply a social semiotic approach to multimodality (e.g. Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2001; Ledin & Machin, Citation2020). As Kress (Citation2010) points out, multimodality in the web era is not merely an issue about how texts look. Digital media and access to an immense amount of web resources also influence people’s processes and choices when designing texts, resulting in ‘more collectively produced texts’, ‘multi-“authored” chains of semiosis’ (p. 192).

Such meaning making processes of putting together pieces from different sources highlight the character of language as material (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2001). Apart from language itself, the role of place (e.g. placement of signs) and physical artefacts (e.g. paper, computers) in meaning making, have been theorised and analysed (Björkvall & Karlsson, Citation2011; Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003). The concept of affordance (Gibson, Citation1979, Räisänen, Citation2018) can be used to describe the possibilities that a certain material artefact or linguistic means offers the users; verbal language affords telling stories, images afford showing things (Kress, Citation2015). When analysing text products, a relevant concept is text element, defined as relatively delimited parts of a text, such as a title or an image (Björkvall, Citation2019, Van Leeuwen, Citation2004). How text elements are combined in texts will be analysed and discussed in this paper in terms of their layout (Kress, Citation2014, pp. 65–70). Sebba (Citation2012) suggests ‘parallelism’ and ‘complementarity’ as two ways to describe multilingual textual compositions. Parallelism is when ‘twin texts’ are offered in different languages (p. 14), whereas complementarity refers to when ‘two or more textual units with different content are juxtaposed’ (p. 15).

In addition to the conceptual tools from literacy and multimodality studies, the concept of translanguaging is useful in describing the communication practices observed. Translanguaging is ‘the ability of multilingual speakers to shuttle between languages, treating the diverse languages that form their repertoire as an integrated system’ (Canagarajah, Citation2011a, p. 401). The integratedness of communicative repertoires is central. Instead of viewing languages as separate entities that can be in contact, the focus is on how people use their linguistic repertoires – at times in an integrated manner and other times by separating languages (Jonsson, Citation2013). Translanguaging is used as an overarching term that encompasses translations and what could be referred to as code-switching (Jonsson, Citation2017). In a translanguaging perspective, language is seen as ‘a repertoire of multilingual, multimodal, multisensory and multi-semiotic resources that language users orchestrate’ (Zhu Hua et al., Citation2017, p. 413). In our analysis, we take an interest in how multilingual and multimodal resources are used, seeing this all as translanguaging (García & Li Wei, Citation2014).Footnote1 We adopt a translanguaging lens to our data, but still use language labels (e.g. Swedish and English) since these emic perspectives are salient for participants.

Translanguaging practices create a social space – a ‘translanguaging space’ (Li Wei, Citation2011) – where speakers bring together dimensions of their experiences, histories, and ideologies (p. 1223). A translanguaging space is ‘transformative’ since it offers the possibility to create ‘new configurations of language practices’ (Zhu Hua et al., Citation2017, p. 412). According to a monolingual orientation, speakers should ‘employ a common language with shared norms’ to ensure ‘efficient and successful’ communication (Canagarajah, Citation2013, p. 1). Our study shows that it is often the translingual nature of communication that enables efficient and successful communication in the contexts we examine.

Translanguaging has gained much attention within the field of education but not equally so in studies of business communication. Lately, however, there has been an increase in publications about translanguaging in the workplace. For instance, Creese et al. (Citation2018) show how translanguaging can be used as ‘a profitable involvement strategy’ (p. 846) and as a salient tool for business (p. 850). Nearly a decade ago, Canagarajah (Citation2011b, p. 6) claimed that translanguaging in writing is an under-researched field. With this article, we wish to contribute to the development of translanguaging as a theoretical concept in both workplace settings and literacy practices, and to enrich the understanding of workplace literacy in elite multilingual contexts.

The research questions guiding this study are informed by our interest in translanguaging and workplace literacy practices. Through observations of workers in elite multilingual settings in Sweden, we ask:

How are different communicative resources used in the workplace literacy practices of Swedish professionals?

o How is translanguaging used in workplace literacy practices?

What factors influence the choice of communicative resources in workplace literacy practices?

The following section provides an overview of the methods used to explore these questions.

Methods, data and analysis: an ethnographic study of two workplaces

The data comes from a linguistic ethnography conducted from September 2016 to June 2018 at two companies, which we call ‘H&H’ and ‘Verona Medical’.Footnote2 In addition to an approved ethical vetting, individual confidentiality agreements were signed with each company. These companies were chosen because they are international workplaces where we expected to find examples of multilingual literacy practices. The data collection methods consisted of interviews with professionals; one focus group discussion; observations of meetings, other work-related activities, lunches, and breaks; shadowing of two key participants in their daily work; field notes; collection of written texts; and linguistic landscaping (See for overview). Data collection and analysis was carried out by both authors. The authors were both outsiders in the companies studied, but share several characteristics with the participants, including high levels of education and use of multiple languages in daily work communication. The key participants were our first contacts in the two companies, and volunteered to take a central role in the study. They were informed of the purpose of the research, and gave us access to their ordinary communication practices, including oral and written communication during meetings and in personal work.

Table 1. Data.

Both companies are located in the Stockholm area. Several professionals are from other countries, and the companies have many and frequent international contacts. The company H&H’s core business is technological product development. The corporate language is Swedish; however, they also use English regularly. The key participant at H&H is Per who is approximately 50 years old and holds a PhD. Per is the manager at one of the units at H&H. His first language is Swedish. He later learnt English in school, which is common in Sweden. Per regards himself as ‘fluent in English’. He has also studied French, some Spanish and Russian.

Medicine is the core business of the second company, Verona Medical. Verona is part of an international pharmaceutical conglomerate and their corporate language is English. They also use Swedish regularly. The key participant at Verona is Richard, a manager, who is approximately 50 years old and also holds a PhD. His first language is Swedish and he learnt English in school. Richard describes his English as ‘very Americanized’. He has also studied German and French but explains that the only languages he would put on his CV are Swedish and English.

For this article, we have selected textual data, interactional data and interview data linked to the literacy practices of these and other professionals. The texts include: digitally produced and handwritten texts, formal texts and more private/personal texts, individually produced texts and collectively produced texts. The interactions include interviews and observations in different meetings. Following an ethnographic approach where the aim is to gain insight into the emic perspectives and lived practices of the participants, we focus on the following in the analysis: (1) texts that the participants have shared with us, and photos we took of texts and, (2) literacy practices observed during the shadowing of key participants, meetings, and reports in interviews. In addition to gaining a broad picture of workplace literacy, we identified texts that included elements of at least two languages, which we analysed in detail to answer the research question on how translanguaging is used in workplace literacy, and what may motivate shifts among different communicative resources.

For the interviews, observations, and data from the focus group, close readings of transcripts and field notes were carried out in the research group. Thereafter, the group chose to delimit the vast material by conducting searches of keywords in English and Swedish. A list of keywords was compiled with relevance to the aspects of literacy practices we aimed to analyse, including metalinguistic terms, and literacy practices (see Appendix 1).Footnote3 Searching for occurrences of these terms allowed us to focus in particular on the instances of translanguaging and explicit literacy practices present in the data. Data triangulation allowed us to detect overall tendencies with regards to literacy practices, translanguaging, and choices in workplace communication. Key participants and other representatives at the companies have approved our analyses. For the discussion of results, we have chosen instances that illustrate the broader tendencies that our analysis identified.

‘You should be able to hold your presentations in both languages’: working in a translanguaging space

Our analysis shows that professionals draw on their linguistic repertoires in their writing and that they use their repertoire both in integrated and in separated manners (see also Jørgensen, Citation2008). At times, they integrate English and Swedish in the same text, which we consider translanguaging. At other times, languages are separated in monolingual texts. However, in cases where only one language is used in the actual texts, we argue that it is likely that the professionals have also made use of their linguistic repertoire in an integrated manner. This is the case when presentations produced in one language are presented in another, or through translanguaging, as observed in our data. Our data also include presentations in English and/or Swedish, in Swedish with technical terms in English, and in Swedish with manuscript notes in English. Thus even when a text is monolingual, the literacy practices around that text – the writing of the text, the notes to the presentations, the oral presentation – are often translingual. In these practices, the linguistic repertoires of the professionals are used in an integrated manner.

The importance of both Swedish and English, and the ability to use them in integrated ways was highlighted in interviews with participants at both companies. One of the people who emphasised this was Mads, an innovation strategist at H&H:

Extract 1: ‘you should be able to hold your presentations in both languages’Footnote4

Mads: you know you come to a conference and then just then you just have to ask excuse me but should I do this in Swedish or in English (.) so I haven’t like even prepared before

[…]

but (.) so for me it works it it is like no problem it is maybe one of the (.) unspoken challenges or situations in today’s work life that you (.) you should be able to hold your presentations in both languages (interview, Dec. 20th, 2016)

Flexible translanguaging practices, such as writing a PowerPoint in Swedish and quickly being able to present it in English without preparation, are thus expected in these work settings. In fact, we found that at both companies professionals need to use both English and Swedish daily, in speech, in reading and in writing.

Translanguaging practices

Translanguaging practices are frequent in speech, in writing, as well as in the linguistic landscape of the two companies. Both companies can be seen as offering, creating and being translanguaging spaces (Li Wei, Citation2011). Professionals use translanguaging to different degrees and in different contexts, and they have different opinions about it, but it is generally a common, ordinary everyday practice. In writing, translanguaging occurs in notes from meetings, notes in calendars, lists, emails and presentations. In the linguistic landscape of the companies, texts in English, Swedish or both are frequent. Examples of both ‘parallelism’ and ‘complementarity’ (Sebba, Citation2012) are found in texts, with a clear preference for complementarity.

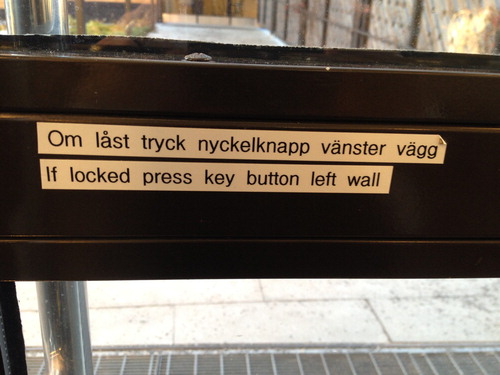

Parallelism is visible already at the signs at the entrance of H&H (see Image 1). The translation is arranged in a word by word manner with the Swedish text placed above the English version. The languages are represented in the same format but in separate plastic tape signs. The imagined readers of the text are visitors to the company who read Swedish or English. Swedish could be said to be given preference, as it is placed above the English text element in the material layout of the sign (Scollon & Scollon Citation2003).

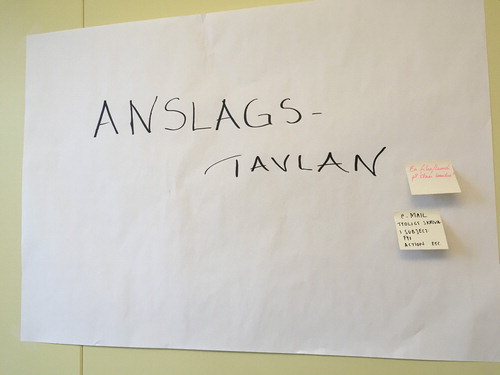

This notice board was set up at the wall of an open office area to invite colleagues to share ideas on how the workplace could become more efficient (see Image 2). The largest text element on the notice board reads ‘ANSLAGS-TAVLAN’ (‘notice board’). The two post-it notes represent suggestions. The post-it note placed slightly higher, written in pink pen, reads ‘En fika/lunch på stan kanske’ (‘A snack/lunch in the city maybe’). The specific connotations of the word fika, however, makes the term difficult to translate into an English word like ‘snack’. The term ‘fika’ represents a central socio-cultural practice that is indexed with particularly high value within Swedish society on a national level, regardless of individuals’ socio-economic status. Traditionally the Swedish fika consisted of coffee and pastries. Despite changes in the rhythms of everyday life, the socio-cultural importance of fika has remained as it marks a social break in the workday. Due to its relevance in Swedish culture, fika is a term that new visitors to Sweden encounter early. At Verona, Sebastian, the head of unit, was given a tray with an illustration of the term described. During our interview, Sebastian, whose first language is English, mentions that he is learning Swedish and that ‘fika’ is one of the few words that he knows. Considering these two instances of data, we can disclose some of the multifaceted dimensions of connotations and of identity work connected to certain words used in a translanguaging space. The word fika can be used in different manners by speakers of Swedish and speakers of English in their joint social practices.

The second post-it includes words in both Swedish and English: ‘e-MAIL TYDLIGT SKRIVA I SUBJECT FYI ACTION ETC’. (‘e-mail clearly write in subject FYI action etc.’), suggesting that people should clearly write in the subject lines of their emails regarding what the email is about. The text is written in uppercase letters and includes abbreviations. Together the texts on the notice board represent how languages can be used in a complementary manner. The imagined readers are able to read both languages and therefore translations are not necessary. However, in reality not everyone reads Swedish, implying that these literacy practices are intended mainly for the participation of Swedish-speaking colleagues, which inevitably excludes others.

The paper attached to the wall opens up for informal communication and for spontaneous ideas being scribbled down at any time, by oneself or together with a colleague. By putting up a piece of paper, someone has invited others to contribute to its creation, and by writing and sharing notes, the professionals add their voices. A similar process could also have been conducted via digital media, stimulating contributions that could have been more individual with the writers sitting behind their own screen.

As to the choice of modalities, we see that colour, materiality (post-it notes, flip chart paper) and layout (uppercase and lowercase letters, placement of letters) are used. The material placement of the noticeboard gives affordances (Björkvall & Karlsson, Citation2011, Gibson, Citation1979) to collaborate; the use of pen and paper gives the interaction an informal framing, and the materiality of post-it notes offers a character of flexibility as they can easily be moved. Additionally, the unconventional use of uppercase letters and colours can be seen as informal traits. The material artifact of post-it notes has connotations of brainstorming and workshops in modern organisational life; simultaneously, the limited space on a post-it note constrains the possibility for people to express longer arguments (see also Björkvall & Karlsson, Citation2011).

In what follows, we will zoom in on the literacy practices of several individuals with different linguistic repertoires to gain greater insight into their translanguaging practices and the choices they make about how to use their communicative resources.

Handwritten notes from a meeting: printing and stapling the digital into a notebook

Richard, a key participant, takes handwritten notes from meetings in an A4-sized notebook that he carries with him. His notes can be regarded as personal in the sense that he buys the notebooks, they are intended for his own reading, he keeps them at home, and regards them as his property. During one of our visits, he showed us his current notebook.

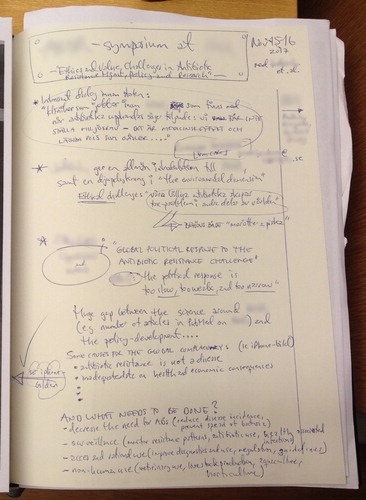

On the left hand side of the page, Richard has stapled a printout of a photo taken with his iPhone (not shown here) (see Image 3). The photo is of a PowerPoint slide and has text in English and an image. Lately, Richard has started printing and stapling photos in the notebook next to his notes from the corresponding meeting/presentation. Previously, when he did not have this habit, he would lose track of his photos (field notes). On the right hand side of the page spread, Richard has written text in English and Swedish and made some illustrations. The following description and analysis is based on the actual text that Richard has shared with us and not on the writing process itself.

Richard’s notes start with the heading of a symposium and the date. The heading is placed in a rectangle where he has drawn four circles as if the rectangle were a sign nailed on a wall. To the right he has written the date ‘Nov 15–16 2017’ according to a possible American ordering of dates – Month, Date, Year.Footnote5 The abbreviation of November is the same in Swedish and English so it is unclear which language it represents, but the order implies it might be English. The date is immediately followed by ‘med [a first name and the initial of a surname] et al.’ (‘with [a first name and the initial of a surname] et al.’). The abbreviation ‘et al.’ derives from Latin but can be regarded as an international academic practice in making reference to co-authors. Here, however, Richard has used ‘et al.’ for making reference to the presenters in a business context. The date in English, the word ‘med’ in Swedish, and the abbreviation ‘et al.’ thus include translanguaging both between languages and professional discourses.

In the main text, Richard has framed some of the text elements with circles and rectangles. He has drawn a cloudlike shape around a note to himself with the text ‘se iphone-bilder’ (‘see iphone photos’). Moreover, there are uppercase and lowercase letters, lots of underlining and different types of arrows in the text. The overall tense is the present, and noun phrases dominate.

When it comes to layout, Richard has divided his notes into different parts by marking them with stars (a practice also noticed in other data from Richard). There are dots and short lines (‘-’) marking the start of points in lists. Richard has also drawn a long line next to the right margin of the paper. To the left of the line are the main notes and to the right is an action list. When there is something he needs to do himself, he has written his initials. In this particular note, he has written an arrow after his initial followed by the names of four people, meaning that he needs to communicate with them. Richard’s illustrations serve as visual cues for him as a reader, marking different text elements, partly by separating the material space of the paper in order to separate and foreground the action list. In the action list, the arrows further show the order of communication (who is going to communicate with whom). The visual cues have potential to increase efficiency since they enable easy detection of actions points as well as the possibility to quickly navigate and search the text.

As to the use of different languages in these notes, some patterns can be observed. Swedish is used to broadly summarise something that has been said. For instance, Richard summed up a general introduction to the main subject of the symposium as well as a dialogue that took place before the start of the meeting – ‘*Intressant dialog innan starten:’, (‘Interesting dialogue before the start’). He used this as a heading, which is indicated by both a star and a colon sign. Swedish is also used for instructions to himself, e.g. ‘se iphone-bilder’. English is used for taking notes from the presentation, for instance when noting down central themes with bullet points (see also Ledin & Machin Citation2015). Richard has also written some buzz words in English, such as ‘Ethical challenge’, partly underlined. The text includes what seems to be quotes in Swedish and English, respectively, marked with quotation marks.

The use of linguistic and semiotic resources in Richard’s personal notes from one meeting shows how he navigates between and across English and Swedish using illustrations as central visual cues, mixing several semiotic resources. Richard’s insistence on using pen and paper for note-taking, as well as his practice of printing photos and stapling them into his notebooks, can be seen as a manner of creating space for ‘old-fashioned’ practices. This shows that, despite a digital turn in society, there is still relevance and need for such material and multimodal practices. The materiality of paper and pen gives affordances of freely placing and sizing text elements, but not of rearranging in the same way as digital media (see also Björkvall & Karlsson, Citation2011, Sellen & Harper, Citation2003). A possible constraint of digital media, avoided while using pen and paper, is the confusing influence of spell check when translanguaging. The key participant at H&H, Per, also used paper notebooks, and noted that variation was the rationale for switching between digital and paper writing (see below).

Richard’s habit of linking PowerPoints, notes, photos and to-do-lists opens up for the interpretation that the paper notebook may serve as a hub or control tool for keeping his complex work gathered. The ethnographic data indicates that both Richard and Per attribute value to their notebooks, choosing them with care and carrying them around everywhere; they represent something stable and physical in their complex workdays, characterised by mobility and diversity. The choice of which communicative resource to use for their personal recordkeeping can be influenced by factors such as the source of the content (quote in either language or a thought or summary of one’s own) and the need for stability and coordination.

Translanguaging spaces in digital and paper calendars

Richard uses both a digital and a paper calendar. During one of our visits, he showed us the current week (23–29 October 2017) in both of his calendars. His digital Outlook calendar was sober looking with every post represented in a square/rectangular box. The paper calendar was in A6 format, in a leather binder with notes in blue ink. Compared to his digital calendar, Richard’s paper calendar looked unruly.

The digital calendar shared with us consisted of 21 posts. Ten posts had mainly Swedish titles – e.g. ‘Introduktion nya medarbetare’, ‘Styrelsemöte’ (‘Introduction to new co-workers’, ‘Board meeting’) – and eleven posts had mainly English titles – e.g. ‘Work Place Strategy’, ‘Weekly chat’. Some titles included translanguaging e.g. ‘[EXTERNAL] … Projektmöte’ (‘Project meeting’), which combines the English word External with the Swedish word Projektmöte. Several abbreviations were used, in both languages. The meeting rooms located in the workplace were in English or Swedish, with the floor number written in English, e.g. ‘3rd Floor’. One meeting was located in ‘Fikahörn’ (the ‘fika’ corner). A meeting in Richard’s office was indicated by the Swedish phrase ‘Kom förbi hos mig’, (‘Come by my place [office]’). On the whole, Swedish and English were used in an integrated manner creating a translanguaging space in the calendar.

The paper calendar shared with us included over 30 posts, some of which had been crossed out. Some posts coincided with posts in the digital calendar whereas others were exclusive to the paper calendar, including private posts like ‘Hembygdsföreningen’, ‘Vinprovning’, ‘Kratta Höststäda’ (‘folklore society/association’, ‘wine tasting, ‘raking autumn clean’). Swedish was used for marking personal leisure time events (see also Sebba, Citation2013, pp. 101–102 for a discussion about language choice based on practical situations where a certain language would likely be used). Richard first writes job meetings and private posts in his paper calendar and later transfers only his job meetings into his digital calendar in order for others to be able to book meetings with him as well as to get reminders about his meetings.

Other participants also told us about their calendars. Celia, HR-responsible at Verona, says that she uses Outlook and a paper calendar for job meetings, and a paper calendar for private posts and To-do lists. Per, at H&H, has developed an individual practice which includes a digital calendar and a paper notebook. First, he writes dated meeting notes by hand in a paper notebook. When necessary he searches for the date of the meeting in his digital calendar and looks up this date in the notebook in order to remember any tasks he may need to perform. The calendar print screens he shared contain posts in English, Swedish and posts with translanguaging, e.g. ‘Uppföljning [Follow up] H&H [project name in English]’.

In both types of calendars, Swedish and English were used in an integrated manner with some posts in one language and others in both. The format of the calendars, as well as language choice, serve to mark the difference between private and workplace related posts, such as the use of paper calendars and Swedish for more private posts. Where the digital calendar is searchable by other co-workers, and offers structure and order, the paper calendar offers a space for the private and the personal (see also Blåsjö et al., Citation2019).

Emails and emoticons

In the six email correspondences from Verona (containing 19 emails and four attached documents), Swedish and English are used. Most of these emails are written in one language but some emails contain elements from both languages, like the greeting ‘Vänliga hälsningar/Kind regards’ written in a parallel manner, and the phrase ‘hör av er asap’ (‘get in touch asap’).

In one of the email correspondences, different languages are used in different emails. Translanguaging occurs across the email correspondence albeit not in the individual emails. English is used in the two first emails between Ofelia and John who are to meet for an interview. These two emails are then forwarded to Richard by Ofelia. Richard contacts John, writing to him in Swedish, and asks him to confirm the interview. John replies in Swedish that he will be available. Richard then writes back to Ofelia, writing in English to include her, copying John in the correspondence. He thanks John and writes that Ofelia will soon be in touch with him. The correspondence ends with an email where Ofelia thanks John and asks him for dates to set up the interview. Through a detour in the correspondence, in which Swedish is used for clarification purposes, communication is attained.

In two emails Richard uses an emoticon, a smiley. He has mentioned to us that some time ago he would never have used emoticons, but that nowadays he can use smileys for people he knows. An emoticon is also used in an email from the company H&H. Celia at Verona dwells on the practice of writing smileys in professional emails, questioning her own usage and asks ‘What does that mean?’. She says that she has even used smileys when writing to someone abroad whom she had never met. Written texts in general can be difficult to interpret, according to Celia. Smileys could possibly be used to clarify the message, as long as the smiley is in line with the message. They can also serve the function to lighten up a formal message (Skovholt et al., Citation2014). Smileys however seem to be perceived as too personal to be used in professional settings. Doing so therefore blurs the distinction between private and professional domains.

Giving preference to one language at a time

Professionals sometimes choose to use their linguistic resources in a separated manner in the production of monolingual texts. Here we will show how priority is given to English and Swedish, respectively.

Making it global: prioritising English

Our study shows that professionals writing to Swedish colleagues are quite willing to set aside Swedish if they think that the text they are producing may be needed in English later. Giving such precedence to a language can be seen as counter to a translanguaging stance. Whereas translanguaging represents an integrated use of different features from a person’s linguistic repertoire, giving priority to English in contrast assumes that one language needs to be dominant. These are two contradictory and simultaneous directions that we see in the results. This again represents the complexity in modern work life, where professionals are expected to navigate and know when to choose either a translanguaging mode or a more monolingual mode. Moreover, it concerns aspects of time in relation to literacy practices (Tusting, Citation2000). When imagining future consequences, professionals make the choices most likely to achieve their social goals (see Wenger, Citation1998 on imagination).

When making decisions about language choice in texts, professionals take account of different aspects. When writing emails, Per at H&H considers not only the primary recipient/s of his emails, but also potential recipients to whom his emails may be forwarded. English is useful if his emails are expected to be forwarded to someone who does not read Swedish (contextual interview). In Extract 2 Richard at Verona also considers the potential recipients of emails. Both these examples show how the addressee is considered when writing emails (see Bell, Citation1984 on Audience design).

Extract 2: Language choice in emails

Richard: very much of other correspondence per per email and so I do in English for the simple reason that it is almost always (.) that that if I also if I write to to several Swedes I know that some of these [people] will want to use the information from this email to her/his manager there and there and then you might as well write it in English from the beginning (Interview, Oct. 10th, 2017)

Here Richard specifically includes managers in his considerations. At the international company Verona, it is not rare that people have their nearest manager in another country. Thus, by writing the email in English, it becomes easier to share, without the need for translations. By choosing English, it is possible that Richard increases the likelihood of his emails being spread to managers around the globe, which could be an advantage for his career. Not only the primary recipient of a text is considered, but several future or secondary recipients influence his language choice. Here, language competence is pivotal. In a study on email correspondence, Incelli (Citation2013) concludes that lack of competence in English may affect the impression of companies’ business credibility, image (p. 522) and negotiating power (p. 529).

English is a language that the companies employ on an international level with respect to their commercial products and ideas. Besides the potential recipients, the prospective of a certain project can also influence language choice, as shown in Extract 3.

Extract 3: Language choice in PowerPoint presentations

Per: … it may be that I travel (.) together with colleagues and meet some small company down in Småland [a province of Sweden]

[…]

that is entirely Swedish (.) ehm (.) and I mean it seems silly to have the material in English (.) if it is something that is developed specifically for that visit (.) eh but if it is something that that has indeed (.) will start as a Swedish initiative but that has the potential to to pick in (.) many parts from all [over] the world then then it is obvious to start in in English (.) so it depends on how how (.) what the potential what the vision for it all is also and what [who] the (.) ehm audience is (Interview, Dec. 8th, 2016)

In Extract 3, Per shows that language choice is determined by the project’s potential, vision and by the audience. This and previous extracts can be interpreted as writers imagining (Wenger Citation1998) future consequences of their texts, thus shaping their literacy practices as to achieve important social goals (Tusting Citation2000) for themselves and their organisation. In the following section, we turn to examples when Swedish is given priority.

Keeping it local: prioritising Swedish

As a small, national language, Swedish represents other possibilities in the workplace. During a meeting at Verona, the presentation slide was mainly written in Swedish, with only parts in English. After the meeting, the person in charge of the meeting and of producing the slides said that she deliberately had chosen to write in Swedish in an attempt to keep the work in the group ‘internal’ eliminating any unsolicited interference or opinions from external, non-Swedish, speakers. She emphasised that this was their job, i.e. locally at the Swedish office, and not a concern to the entire international company (field notes). Swedish thus became a secret language for keeping the discussions local and exclusive. While English represents possibilities for outreach and inclusion, Swedish affords the opposite – possibilities of withdrawal, exclusion and of discussing matters in a private, in-house form of communication (see also Blåsjö et al., Citation2019).

Another PowerPoint document in our data stems from a sales meeting outside of the office. Isabella, a key account manager, whose first language is English, presented a specific product to professionals in their workplace. She told us that a product manager was responsible and put a presentation together in collaboration with a medical expert. Then an external PR agency designed it, after which Isabella checked and revised both the actual presentation and the manuscript items on which she was supposed to base her oral presentation. Several medical and legal experts eventually checked the text product.

Analysing this sales document – both the actual presentation pages and the manuscript notes – in the context of an oral presentation, we found that the slides shown to listeners are written in Swedish with instances of Latin, the manuscript notes mainly in Swedish, but also in English, and that the oral presentation was held solely in Swedish. The notes for the presenter include cues for physical actions such as ‘peka i figuren’ (‘point in the figure’). The slides include naturalistic photos, traditional figures such as diagrams and infographics. The slides combine scientific discourse (e.g. literature references) with commercial/advertising discourse (e.g. photos of happy people). A multitude of semiotic resources were thus drawn upon in the meetings, as well as in the PowerPoint and the literacy practices behind it. Although the presentation was held in Swedish, the example shows how the surrounding literacy practices often are translingual. Moreover, the process of producing the PowerPoint was ‘multi-authored’ (Kress, Citation2010), integrating different types of competence, text elements and languages in a translanguaging space, connecting the global English-speaking company with the local Swedish-speaking practitioners taking part in the presentation.

Filling gaps in repertoires: Google translate as literacy practice

Apart from the affordances of using a local language mentioned above, digital tools such as Google Translate offer new possibilities for using Swedish in new ways. Sebastian, head of unit at Verona, speaks only English but can access texts in Swedish with Google Translate. The employees at Sebastian’s unit are aware of his use of and reliance on Google Translate and can therefore include him in email correspondences in Swedish. An example of this is given in Extract 4.

Extract 4: ‘he does Google Translate’

Miranda: then they write to him in Swedish if he is [addressed] in an email and I can do the same ah it is for Sebastian he does google translate (Interview, Oct. 3rd, 2017)

During a lunch conversation, Sebastian told us that, besides using Google Translate on his computer, he uses Google Chrome, which offers a setting that translates web pages into English, and that he uses the Google Translate app on his mobile. He describes the app as an ‘augmented reality’ and shows an awareness of its limitations: ‘good for understanding, not so good for learning’. He realises that the app will not significantly improve his language skills, but he seems content with at least being able to get the gist of different texts in Swedish.

Whereas Sebastian depends on Google Translate, his colleague Isabella, whose first language is English and who also speaks Swedish, has other possibilities for understanding and writing texts. Due to her language competences, she is sometimes asked by colleagues to assist them in proof reading, translating or writing texts in English, although this is not part of her actual job description. She says that even though many Swedes speak ‘beautiful English’, not everyone masters the ‘finesse of writing English’ or has ‘flashy vocabulary’. Isabella refers to herself as ‘an asset’ in this sense. She hints at the limitations of Google Translate: ‘you know even if you got you know your Google app (.) and (.) I know immediately what the best the adjective is to use’ (interview), showing that writing is not just about direct translations. Isabella thus clearly contests the reliance on Google Translate, at least in the production of texts.

Sebastian, who is not bilingual in Swedish and English, resorts to getting by and attempts to at least understand Swedish with the support of digital tools. Isabella, on the other hand – being a bilingual in Swedish and English – has the possibility to exploit nuances in both languages, and to be a bilingual resource to others in the workplace.

Our results show that language choice and language use depend on several different factors such as language competence, personal preferences, position and role at the company. Whereas the importance of Swedish is emphasised in for instance national sales, professionals working as head of a unit can get by using only English, which in Sweden is a language that is taught from primary school and has high status both nationally and globally.

Discussion and conclusion

Everyday communication at the studied companies is translingual, multimodal, digital and complex. In their writing, professionals draw on many different linguistic and semiotic resources and often use their linguistic repertoires in an integrated manner that results in translanguaging practices. They also produce texts in which the languages are kept separate, giving precedence to one language at a time. Our analysis shows how linguistic repertoires include linguistic resources from Swedish, English and some Latin from an academic register. Additionally, multimodal semiotic resources such as photos, lists, emoticons, and drawings are used. These resources can be traced from different discourses – predominantly business discourse, medical discourse, general academic discourse and personal discourse – related to everyday practices at the workplace. Moreover, they represent both new and old technology such as stapling and handwriting.

At both companies, translanguaging spaces are created by the professionals as they navigate their linguistic repertoires in their daily work life. Translanguaging can be used to exploit subtle nuances and possibilities in and between different languages. Using languages in a more integrated manner or separating them in texts, represents two contradictory tendencies in our results. Also when the professionals opt for a monolingual text, the literacy practices that surround the text – such as the writing of the text, the notes of a presentation, and the oral presentation – are often translingual. A PowerPoint in one language may be presented in another, at times with translanguaging practices. The translingual nature of communication enables efficient and successful communication. Knowing when to choose a translanguaging mode or a more monolingual mode is a necessary skill or competence in this type of workplace.

Language choice and language use depends on several different factors such as language competence, personal preferences, position and role at the company, but also the imagined audience of a text and the expected future potential and usage of a text (Tusting Citation2000). Moreover, historical factors such as registers from discourses developed over time influence choice of communicative resources, such as the use of Latin from an academic discourse and post-it-notes as a conventional tool for brainstorming (see also Scollon & Scollon Citation2003). The choice of language can include or exclude an audience (Lillis & Curry Citation2013), as in the case of using Swedish as a secret language. The choice of other communicative resources depend on need of stability and coordination, both one’s own and within the workplace, such as the digital calendar needed for coordinating joint meetings.

Workplace literacy includes the ability to choose suitable language/s and modalities when writing different texts. This ability includes the competence to plan in several steps and foresee who is likely to read a text after the primary recipients. Multimodality in modern workplaces concerns not only layout of specific texts but also material aspects such as placement and movability. Older materialities such as pen and paper are still in use and complement digital media. Possible reasons to choose pen and paper could be to maintain control over complex work situations, attributing it to one’s identity and uniqueness, and tying together different digital and oral communication in one physical artifact such as a paper notebook. The ability to write across multiple languages with no interference from spell check is another possible motivation.

In society recently, we have witnessed a digital turn, through which writing emails, scheduling in digital calendars and using Google Translate have become everyday literacy practices in many workplaces (Jones & Hafner, Citation2012). Our results show that although this has had a great influence on work life, the use of pen and paper is still essential in literacy practices within these contexts. It is not only digital or only handwritten. It is not only modern or traditional. It is not one or the other, but both. This is in line with what we see regarding a translanguaging mode versus a more monolingual mode. It is not one or the other, but both, and a multitude of linguistic and semiotic resources are always involved.

The importance of offering professionals support in their daily languaging/translanguaging practices (e.g. by offering proofreading services and other language-related support), and of recognising and rewarding professionals’ skills in translanguing (e.g. in recruitment processes) are implications of this study. Our results that modern work life demands skills of knowing when and how to translanguage can also have certain implications for education, since the educational system prepares adolescents for the workplace. In future research, it is important to continue expanding the scope of professional communication from discrete texts and meetings to ethnographic studies in contexts. By taking such a perspective, our aim has been to enrich the image of what occurs within specific elite and modern workplaces, where translanguging became a valuable theoretical lens to study multilingual and multimodal workplace communication.

Transcription conventions

Italics: Swedish in original (our translations)

Bold: English in original

[ ]: Contextual detail

(.): short pause

Acknowledgements

The data comes from the research project ‘Professional Communication and Digital Media: Complexity, Mobility and Multilingualism in the Global Workplace’, [Marcus and Amalia Wallenberg Foundation, 2016–2019], under Grant number 2015.0093. We wish to thank participants at both companies for generously contributing to our project, Center for Multilingualism in Society across the Lifespan for the invitation to present the initial version of this paper, and the anonymous reviewers for valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The term multilingual is used as a broad term to refer to the coexistence of and use of more than one language.

2 All company and personal names have been replaced by pseudonyms.

3 The research group consisted of the two researchers Carla Jonsson and Mona Blåsjö, and the project assistant Sofia Johansson. The latter conducted the search of keywords.

4 For transcription conventions, see section below. Our translations from Swedish.

5 In Swedish, the dates would more generally be written either in the order Date, Month, Year or alternatively Year, Month, Date.

References

- Angouri, J., & Miglbauer, M. (2014). ‘And then we summarise in English for the others’: The lived experience of the multilingual workplace. Multilingua, 33(1–2), 147–172. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2014-0007

- Barton, D., Hamilton, M., & Ivanič, R. (Eds.). (2000). Situated literacies: Reading and writing in context. Routledge.

- Bell, A. (1984). Language style as audience design. Language in Society, 13(2), 145–204. https://doi.org/10.1017/S004740450001037X

- Björkvall, A. (2019). Den visuella texten: Multimodal analys i praktiken [ The visual text. Multimodal analysis in practice]. 2nd ed. Studentlitteratur.

- Björkvall, A., & Karlsson, A. (2011). The materiality of discourses and the semiotics of materials: A social perspective on the meaning potentials of written texts and furniture. Semiotica, 2011(187), 141–165. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.2011.068

- Blåsjö, M., Johansson, S., & Jonsson, C. (2019). “Put meeting in my calendar!” The literacy practice of the digital calendar in workplaces. Sakprosa, 11(1), 1–47. https://doi.org/10.5617/sakprosa.5951

- Blommaert, J., & Rampton, B. (2011). Language and Superdiversity. Language and Superdiversities, 13(2), 1–22.

- Brown, R. L., & Herndl, C. G. (1986). An ethnographic study of corporate writing. In B. Couture (Ed.), Functional approaches to writing. Research perspectives (pp. 11–26). Pinter.

- Busch, B. (2012). The linguistic repertoire revisited. Applied Linguistics, 33(5), 503–523. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/ams056

- Canagarajah, S. (2011a). Codemeshing in academic writing: Identifying teachable strategies of translanguaging. The Modern Language Journal, 95(3), 401–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01207.x

- Canagarajah, S. (2011b). Translanguaging in the classroom: Emerging issues for research and pedagogy. Applied Linguistics Review, 2, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110239331.1

- Canagarajah, S. (2013). Translingual practice: Global English and cosmopolitan relations. Routledge.

- Creese, A., Blackledge, A., & Hu, R. (2018). Translanguaging and translation: The construction of social difference across city spaces. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(7), 841–852. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1323445

- Darics, E. (2017). E-leadership or “how to be boss in instant messaging?”. The Role of Nonverbal Communication. International Journal of Business Communication, 57(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488416685068

- García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Houghton-Mifflin.

- Golden, A. G., & Geisler, C. (2007). Work–life boundary management and the personal digital assistant. Human Relations, 60(3), 519–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726707076698

- Gumperz, J. (1964). Linguistic and social interaction in two communities. American Anthropologist, 66(6_PART2), 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1964.66.suppl_3.02a00100

- Höllerer, M. A., van Leeuwen, T., Jancsary, D., Meyer, R. E., Andersen, T. H., & Vaara, E. (2019). Multimodal legitimation and corporate social responsibility (CSR). In M. A. Höllerer, T. v. Leeuwen, D. Jancsary, R. E. Meyer, T. H. Andersen, & E. Vaara (Eds.), Visual and multimodal research in organization and management studies (pp. 162–179). Routledge.

- Hua, Z., Wei, L., & Lyons, A. (2017). Polish shop(ping) as translanguaging space. Social Semiotics, 27(4), 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2017.1334390

- Incelli, E. (2013). Managing discourse in intercultural business email interactions: A case study of a British and Italian business transaction. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 34(6), 515–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.807270

- Jones, R. H., & Hafner, C. A. (2012). Understanding digital literacies: A practical introduction. Routledge.

- Jonsson, C. (2013). Translanguaging and multilingual literacies: Diary-based case studies of adolescents in an international school. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2013(224), 85–117. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2013-0057

- Jonsson, C. (2017). Translanguaging and ideology: Moving away from a monolingual norm. In B. Paulsrud, J. Rosén, B. Straszer, & Å Wedin (Eds.), New perspectives on translanguaging and education (pp. 20–37). Multilingual Matters.

- Jørgensen, J. N. (2008). Polylingual languaging around and among children and adolescents. International Journal of Multilingualism, 5(3), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790710802387562

- Kankaanranta, A. (2006). “Hej Seppo, could you pls comment on this!”—internal email communication in Lingua Franca English in a multinational company. Business Communication Quarterly, 69(2), 216–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/108056990606900215

- Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. Routledge.

- Kress, G. (2014). What is a mode? In C. Jewitt (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis (2nd ed., pp. 60–75). London: Routledge.

- Kress, G. (2015). ‘Literacy’ in a multimodal environment of communication. In J. Flood, S. B. Heath, & D. Lapp (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching literacy through the communicative and visual arts (Vol. 2, pp. 91–100). Routledge.

- Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. Arnold.

- Ledin, P., & Machin, D. (2015). How lists, bullet points and tables recontextualize social practice: A multimodal study of management language in Swedish universities. Critical Discourse Studies, 12(4), 463–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2015.1039556

- Ledin, P., & Machin, D. (2020). Introduction to multimodal analysis (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury Academic.

- Lillis, T., & Curry, M. J. (2013). Academic writing in a global context: The politics and practices of publishing in English. Routledge.

- Martin-Jones, M., Buddug, H., & Williams, A. (2009). Bilingual literacy in and for working lives on the land: Case studies of young Welsh speakers in North Wales. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 195, 39–62. https://doi.org/10.1515/IJSL.2009.005

- McNely, B. (2019). Under pressure: Exploring agency–structure dynamics with a rhetorical approach to register. Technical Communication Quarterly, 28(4), 317–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2019.1621387

- Räisänen, T. (2018). Translingual practices in global business. A longitudinal study of a professional communicative repertoire. In G. Mazzaferro (Ed.), Translanguaging as everyday practice (pp. 149–174). Springer.

- Rymes, B. (2014). Communicating beyond language: Everyday encounters with diversity. Routledge.

- Scollon, R., & Scollon, S. W. (2003). Discourses in place: Language in the material world. Routledge.

- Sebba, M. (2012). Researching and theorizing multilingual texts. In M. Sebba, S. Mahootian, & C. Jonsson (Eds.), Language mixing and code-switching in writing: Approaches to mixed-language written discourse (pp. 1–26). Routledge.

- Sebba, M. (2013). Multilingualism in written discourse: An approach to the analysis of multilingual texts. International Journal of Bilingualism, 17(1), 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006912438301

- Sellen, A. J., & Harper, R. H. (2003). The myth of the paperless office. MIT Press.

- Skovholt, K., Grønning, A., & Kankaanranta, A. (2014). The communicative Functions of emoticons in workplace E-Mails::-). Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(4), 780–797. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12063

- Thurlow, C., & Jaworski, A. (2012). Elite mobilities: The semiotic landscapes of luxury and privilege. Social Semiotics, 22(4), 487–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2012.721592

- Tusting, K. (2000). The new literacy studies and time. An exploration. In D. Barton, M. Hamilton, & R. Ivanic (Eds.), Situated literacies: Reading and writing in context (pp. 33–50). Routledge.

- Van Leeuwen, T. (2004). Introducing social semiotics. Routledge.

- Wei, L. (2011). Moment analysis and translanguaging space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(5), 1222–1235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.035

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.