ABSTRACT

This article advances thinking around the semiotic repertoire by exploring how resources are negotiated in the course of interactions mediated by mobile messaging apps, and how this process of co-constructing repertoires is shaped by the affordances and constraints of the virtual spaces in which these interactions take place. Drawing on micro-analysis of ethnographic data from a large funded project, we focus on the closed online networks of two women of Polish origin living and working in the UK, looking specifically at their uses of mobile messaging apps including WhatsApp and Viber. We show how resources come into being through talk and how emergent semiotic repertoires take shape in processes of repertoire assemblage. In particular, we explore the ways in which technological affordances and pre-programmed signs are harnessed and exploited by mobile interlocutors for making meaning in the course of an immediate interaction, often with longer term impact within a network’s emergent repertoire. The study highlights the importance of a dynamic conceptualisation of the semiotic repertoire.

Introduction

This article advances thinking around the semiotic repertoire by exploring how resources are negotiated in the course of interactions mediated by mobile messaging apps, and how this process of repertoire assemblage is shaped by the affordances and constraints of the virtual spaces in which these interactions take place. An individual’s semiotic repertoire is not an internalised construct but exists only as ‘constraints and potentialities’ (Busch, Citation2014, p. 14) which are realised within an interactional encounter. As such, the ways in which semiotic resources are taken up are shaped both by the interactional dynamics and by people, objects and activities in the wider material and social environment (Pennycook, Citation2018).

Based on analysis of ethnographic data from a large funded project, our article builds on these observations to show how emergent semiotic repertoires are shaped in the course of mobile messaging interactions. We focus on the closed online networks of two women from Poland living and working in the UK, looking specifically at their use of mobile messaging apps such as WhatsApp and Viber for one-to-one chats and private groups. In these online spaces, interlocutors draw on pre-programmed signs made available through the app (Androutsopoulos, Citation2019) and on elements of their physical contexts brought into interactions through such functionalities as images and locating devices (Lyons & Ounoughi, Citation2020). Through moment-by-moment analysis of the process of repertoire assemblage, we explore the ways in which interlocutors collaborate in – or challenge – the co-construction and curation of semiotic repertoires and the potential longer-term impact of this process on their practices. Our contribution to the existing literature is twofold: firstly, we evidence how semiotic resources are not simply brought along to any one moment of interaction by individual interlocutors, but are discursively co-constructed in the course of unfolding interactions, thus highlighting the importance of a dynamic conceptualisation of the semiotic repertoire; secondly, we show how this process of repertoire assemblage is shaped by the affordances and constraints of the virtual spaces in which these interactions take place.

The semiotic repertoire

The concept of the semiotic repertoire – the array of communicative resources available to an individual as selectively deployed across interactional encounters – has enabled a fluid understanding of how people make meaning across multiple language varieties and semiotic modes in everyday interaction. As understood by Blommaert and Backus (Citation2013, p. 19), an individual’s semiotic repertoire includes all the ‘bits of language’ which individuals ‘pick up’ as they move through varied contexts and navigate interpersonal networks, as well as a range of other acquired semiotic resources, from gestures and posture to ‘knowledge of communicative routines, familiarity with types of food or drink … and mass media references’ (Rymes, Citation2014, p. 303; cf Blackledge & Creese, Citation2018; Kusters et al., Citation2017). Building on the notion of the repertoire as biographical, Busch (Citation2014) argues that the lived experience of language – particularly in contexts of mobility, migration and displacement – may in part determine the resources that an individual uses to position themselves. As this suggests, repertoires are not fixed but fluctuate across an individual’s lifetime as resources are enabled, unused or forgotten.

One limitation of this conceptualisation of the semiotic repertoire is the tendency to focus attention on what an individual brings to an interaction, potentially downplaying the significance of the wider interactive context (Pennycook, Citation2018). From Busch’s (Citation2014, p. 7) perspective, repertoires are ‘formed and deployed in intersubjective processes located on the border between the self and the other’. Pennycook (Citation2018, p. 454) adds interactions with ‘artefacts and space’ to his reconceptualisation of repertoire. In the context of the busy commercial spaces explored in Pennycook and Otsuji (Citation2015), for example, the deployment of repertoires is shaped by noise and bustle, flows of customers, artefacts in use and products being sold. Their notion of the ‘spatial repertoire’ (cf Canagarajah, this collection) reflects a wider recognition of the sociocultural importance of space, conceived not only as physical or material but also as socially constructed or produced (Lebefvre, Citation1991) through a range of semiotic resources (Hua et al., Citation2017a).

Here, we propose a view of a semiotic repertoire as co-constructed in the process of repertoire assemblage, an emergent construct shaped by interactions between the self, the other and the (technologically) mediated context. Our analysis of unfolding interactions shows how repertoires emerge from the interplay between material affordances and interlocutors’ attempts to exploit the available resources to make meaning.

Repertoires and the networked individual

Alongside the semiotic and material resources discussed above, repertoires in the twenty-first century increasingly include signs used primarily or exclusively in digital media. In fact, as we argue elsewhere (Tagg & Lyons, Citationforthcoming), digital media themselves constitute elements of an individual’s semiotic repertoire. Choices regarding device (e.g. mobile phones and laptops), platform (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp) and channel or mode of communication (voice calls, texting) are meaningful both in the sense that the use of one rather than another imparts social meaning, and because the meaning of embedded or nested resources (e.g. words, emoji, photos) can be shaped by the social connotations of the resource (e.g. platform) into which they are embedded, and vice versa (Tagg & Lyons, Citationforthcoming). In digitally mediated interactions, then, the deployment of semiotic repertoires is shaped by a complex interplay between resources at different levels, with their associated affordances.

In comparison to open digital spaces, private digital contexts – defined by the closed nature of the channel, and often characterised by a smaller number of participants and by expectations of privacy – have generally received less scholarly attention in the discussion of digital repertoires, not least because of difficulties in accessing data (Androutsopoulos & Juffermans, Citation2015, p. 3). Nonetheless, a focus on so-called private contexts – such as one-to-one online exchanges and closed WhatsApp groups – is important to the study of repertoire as it enables researchers to focus on networked individuals (Papacharissi, Citation2010), rather than larger-scale communities, and thus to explore the different ways in which individuals exploit contexts, affordances and resources across multiple offline and digitally mediated spaces in order to achieve communicative purposes. We conceptualise the networked individual in two related ways: firstly, as being connected to distributed others within complex social networks stretching online and offline; and, secondly, as being embedded in the wider hyperlinked digital text with access to locally and globally circulating networked resources (cf. Androutsopoulos, Citation2015). Although particularly evident in the deployment of repertoires in online spaces, repertoires are always networked in this sense: reliant on the ways in which available resources are taken up and shaped by people’s complex social connections.

Consequently, how repertoires are deployed in digital interactions can only be understood in relation to an individual’s wider social networks and identity performances across offline and online spaces. From this perspective, digital media users are seen to draw creatively on a broad range of available graphic resources to position themselves in relation to their interlocutors and fulfil pragmatic functions associated with the use of bodily and gestural resources in face-to-face interactions (Georgakopoulou, Citation1997; McSweeney, Citation2018).

One aspect of digital interaction with implications for the co-construction and deployment of repertoires is the array of pre-programmed signs made available within different apps and platforms, including emoji, stickers, gifs and videos (Androutsopoulos, Citation2019). These ‘graphicons’ (Herring & Dainas, Citation2017) fulfil a range of pragmatic functions (Ge & Herring, Citation2019; Panckhurst & Frontini, Citation2019) that do not necessarily correspond to their – often ambiguous – semantic meanings. Graphicons have been seen to increase the sense of social connection and intimacy between users (Janssen et al., Citation2014), especially in the case of detailed stickers resembling non-verbal cues in offline contexts (Wang, Citation2016). Although different graphicon sets (such as emoticons and emoji) are sometimes conflated, there are differences in how they are perceived and used by users; for example, emoji may be seen as semantically richer than emoticons (Chen et al., Citation2018); and stickers are potentially perceived as more ‘expressive’ (Tang & Hew, Citation2019, p. 2459) than emoji. As this suggests, choices occur both within one set of resources – selecting one emoji rather than another – as well as across different sets – choosing a Bitmoji, for example, if an appropriate emoji cannot be found. The multiple modes thus available to users might be seen to enhance the potential for communicative fluidity, effectiveness and precision in the digital space (Lim, Citation2015). The selection and use of pre-programmed signs emerges from a dialectic between users’ communicative goals on the one hand and, on the other, the commercial interests, in-built assumptions and prevailing semiotic and cultural ideologies which drive software design (Djonov & van Leeuwen, Citation2017). The ways in which pre-configured artefacts are appropriated and relocalised are thus shaped not only by software design but by social processes of (dis)identification, indexicality and sociolinguistic authentication. This dynamic can be seen as contributing to the ‘evolution’ of graphicon use, as their pragmatic meaning shifts and becomes conventionalised (Konrad et al., Citation2020).

What also becomes apparent through the study of closed online networks – particularly those mediated by the mobile phone – is the fluidity with which people move between online and offline spaces in their daily lives, often while interlocutors are physically on the move (Cohen, Citation2015; Lyons & Ounoughi, Citation2020). Despite initial assumptions of an online/offline divide, research suggests that users often make physical contexts relevant in online settings, for example through posting photos or sharing location information (Lyons & Ounoughi, Citation2020), as well as their use of deictic information (Lyons, Citation2014). Opening a window into geographically distant interlocutors’ physical worlds can in turn increase involvement in interactions (Tagg & Hu, Citation2017) and heighten feelings of intimacy across distance (Miller & Sinanan, Citation2014). The functionalities of digital media – pasting, copying, embedding – make possible this fluid intermingling of contexts which increasingly forms an essential part of many people’s semiotic repertoires ‘on the move’.

The current study builds on the above insights to explore processes of repertoire assemblage in selected instances of digital communication mediated through mobile messaging apps – that is, the repertoire choices that networked individuals make in interactions which often unfold whilst they are engaged in other physical activities and on the move – focusing on one-to-one interactions and closed groups. We show how our participants’ selection and deployment of multilingual and multimodal resources from across their semiotic repertoires not only reflect their individual migration histories and post-migration experiences but also respond to their engagement with their interlocutors, as well as being shaped by the affordances of the digital space. Importantly, through close empirical analysis, we also show how repertoires are shaped through interaction and how resources themselves come into being – either implicitly or explicitly – through digital talk in processes of repertoire assemblage: through the adoption and manipulation of pre-programmed signs and the emergence of apparently new semiotic resources.

Context, data and methods

Post-digital linguistic ethnography

The data for this study was collected as part of a large linguistic ethnography Translation and Translanguaging: Investigating Linguistic and Cultural Transformations in Superdiverse Wards in Four UK Cities.Footnote1 The project was carried out across four UK cities. Each city case study worked predominantly with speakers of selected languages: Polish was the language investigated in London. Key participants were observed and then audio- and video-recorded at work, where we also interviewed them, before being asked to record domestic and social interactions. Digital data was collected as part of the ‘home data’ collection stage, usually in the form of screenshots of participants’ mobile phones taken by a team member or the participant, in order to capture how participants’ repertoires and practices extend across physical and digitally enabled spaces. Given our intrusion into multiple aspects of their lives and the extensive personal data collected on individuals, our ethical responsibilities to our participants remained central to the project throughout its duration, and we worked closely with participants in (re)negotiating their consent and making ethically informed decisions on a case-by-case process at what Markham (Citation2003) calls ‘critical junctures’ (cf Tagg et al., Citation2017). Formal ethical approval for the project was granted by the Humanities & Social Sciences Ethical Review Committee, University of Birmingham (ERN_13-0963).

This project design allows for a post-digital linguistic ethnography approach which recognises that digital technologies have ceased to be a novel or disruptive influence, but are instead experienced as an inherent part of being human (Cramer, Citation2015). In a post-digital society, digital technologies are embedded in wider social practices and relationships and intertwined with offline activities and physical contexts (Marsh, Citation2019), while semiotic repertoires are structured and organised around the intersections between language and media choices (Tagg & Lyons, Citationforthcoming; Vold Lexander & Androutsopoulos, Citation2019). Our post-digital ethnographic approach assumes the importance of understanding online interactions within the context of their physical settings, as well as participants’ personal histories and language ideologies. The approach builds on existing (linguistic) ethnographies which combine online data with interviews and (sometimes) offline observations in order to gain an emic understanding of people’s online lives (e.g. Androutsopoulos, Citation2008; Dovchin et al., Citation2018; Jonsson & Muhonen, Citation2014). Our methodology departs from these approaches in terms of the balance between offline and online data. Rather than combining offline and online ethnography, we collected digital data as part of an otherwise offline ethnography. This project design prompted us to interpret the digital data not primarily in the context of its online setting but rather in the context of the networked individual’s wider milieu and social networks. Our focus was thus not on understanding people’s online practices through insights gathered in offline contexts, but rather to understand individuals’ (networked) practices across the many social spaces they inhabit, including online ones; that is, to understand digital practices as part of networked individuals’ lived experiences across contexts (cf Bagga-Gupta et al., Citation2019).

Participants

This article focuses on data collected in London from two key participants who had grown up in Poland and moved to London as adults, and for whom being Polish was, in different ways, very salient to their sense of identity. Despite this shared national and migratory background, the two women differed in terms of their current occupation and lifestyle: Marta was an actor and translator, and Edyta ran a Polish shop (both names are pseudonyms).

Marta was born in the north-east of Poland. She first came to the UK in 2003 to visit a friend, and decided to stay. She has a BA degree in acting from a drama school affiliated to a UK university and had been working towards a diploma in translation in a London university. At the time of our study, she was in her early 30s and worked as a self-employed artist and artistic director of an East London non-profit art organisation. Marta also had a portfolio of part-time jobs including ‘front of the house’ duties at two arts centres, and translating and interpreting work.

Marta carried her iPhone and an 11-inch Macbook Air wherever she went. She was an experienced and confident technology and social media user, and was active on Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr where she presented herself as a performer and artist who crossed linguistic, cultural and artistic boundaries. As well as her public social media posts, we also collected her work-related emails and WhatsApp and SMS interactions with friends and family alongside other datasets ().

Table 1. Marta’s data.

At the time of our study, Edyta ran a Polish shop on the high street in Newham, London with her husband, Tadeusz. Edyta and Tadeusz came from south-eastern Poland and moved to the UK in 1997. The couple’s then-10-year-old daughter had been born in the UK. A Polish speaker, Edyta did not learn English until arriving in the UK, where she took classes.

Edyta had a mobile phone contract with inclusive data transfer allowance on an iPhone. While Edyta appeared to be constantly connected via various mobile messaging apps (she always carried her phone with her and used it throughout her time in the shop – see Hua et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017b), she was a much less frequent user of Facebook or email. The vast majority of her messages (see ) include predominantly Polish-oriented resources, reflecting the ethnic homogeneity of Edyta’s translocal network across London and Poland. The English-language resources used by Edyta tended to be limited to a few words and fixed phrases. For example, in response to a customer’s query in English about the shop’s opening times, sent by SMS text message, she offered a brief Close 8, omitting the standard preposition (at).

Table 2. Edyta’s data.

Data

The digital data is summarised in .

Table 3. Edyta and Marta digital data overview.

Rather than transcribing the digital data, we worked with anonymised screenshots – with parallel translations into English – aiming to preserve the original context of the interactions. We recognise the importance of reflexivity in ensuring the visibility of translation in ethnographic research and in critiquing its ‘assumed neutralness’ (Bagga-Gupta et al., Citation2019, p. 338). Our data translation was mediated by the second author, a Polish speaker who was closely involved in observing and interviewing both research participants. However, we see our translation activities as a team endeavour, by which, in Bassnet’s (Citation2014, p. 57) words, ‘discursive transformations occur as different groups endeavour to represent themselves to one another’. As such, we have found it useful to conceptualise our translation activities with reference to ‘translation zones’ (Apter, Citation2006); that is, ‘areas of intense interaction across languages, spaces defined by an acute consciousness of cultural negotiations and often host to the kinds of polymorphous translation practices characteristic of multilingual milieus’ (Cronin & Simon, Citation2014, p. 120). Applied to a research team, the concept of the translation zone highlights the multiple repertoires, cultures, and ideologies brought to bear on the process of selecting, producing and disseminating translations (cf Tagg & Hu, Citation2015). The notion of the translation zone is also useful in foregrounding a paradox evident in our team translations: on the one hand, translation zones are spaces of hybridity in which translators adopt a range of ‘polymorphous’ translation strategies; on the other hand, the act of translating itself reaffirms established boundaries between named languages (Barry, Citation2013, p. 416). For example, in our translations of the Polish data we highlighted with italics what we saw as words of English origin – or which we felt our participants would perceive as ‘English’ – decisions that required us to police the boundaries of the two languages and evaluate any overlap. We hope that, given our aim of exploring how these forms coincide and combine in our participants’ meaning making, our translation practices do not lead to distancing – that is, they do not ‘underscore the differences that prevail among cultures and languages’ (Cronin & Simon, Citation2014, p. 122) – but to furthering, where translations are ‘revivifying and expansive … with influences, alterations and combinations which would not have been possible’ (Grossman, Citation2010, p. 16) without the presence of other languages.

Subsequent analysis of the data was also a team endeavour which took two main strands. The first comprised a thematic analysis of the digital data, audio data, fieldnotes and interviews, by the London city team (see Hua et al., Citation2015, Citation2016, Citation2017a) which identified broad themes across the datasets. The second comprised a moment analysis (Li Wei, Citation2011; cf Androutsopoulos, Citation2014) of selected extracts from the digital data by the authors of this article, informed by the thematic analysis and our ethnographic experience in the field. The selection of extracts for the second stage drew on the principles of moment analysis in that we identified ‘critical and creative moments of individuals’ actions’ (Li Wei, Citation2011, p. 1224) in the data. Like Li Wei's, our focus is on the development of fleeting everyday ‘spur-of-the-moment’ episodes within interactional encounters which are nonetheless characterised by distinctiveness and the potential for transformation as resources come into being. As Hua et al. (Citation2017a, p. 417) point out, moment analysis recognises people’s active agency by focusing on how larger social structures and linguistic patterns emerge from everyday practices.

Our analysis of repertoire assemblage in the participants’ mobile messaging interactions is also guided by Bagga-Gupta and colleagues’ concept of chaining, which provides an analytical framework for mapping how social action is accomplished through the ‘interconnectedness’ of multiple named languages and modalities (e.g. Bagga-Gupta, Citation2017; Bagga-Gupta et al., Citation2019). Chaining across semiotic resources is not only synchronised (with named languages and modalities being used in parallel) and local (linked to one another within and across turns), but also unfolds across wider trajectories of time and space through activity-chaining (Bagga-Gupta, Citation2017, p. 11). In our analysis, we explore how repertoire assemblage, as a phenomenon, is accomplished through processes of chaining.

In what follows, we draw on two data extracts selected from our wider analysis to illustrate two types of repertoire assemblage: one which is implicit and unremarked upon (Edyta), and another which emerges from a more deliberate instance of language play (Marta). In both cases, we see how the pragmatic meaning of resources is interactively co-constructed in processes of chaining shaped both by the digital spaces and wider social contexts.

Data analysis

Także zabdejtujcie sobie mózgi (So update your brains)

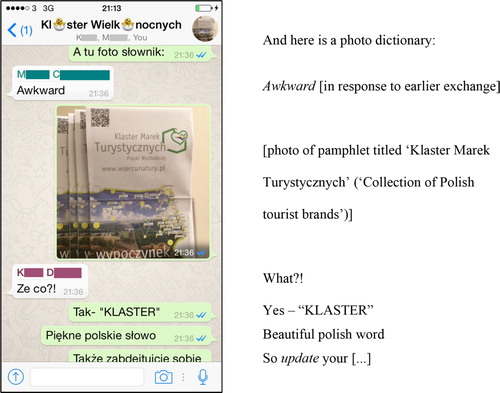

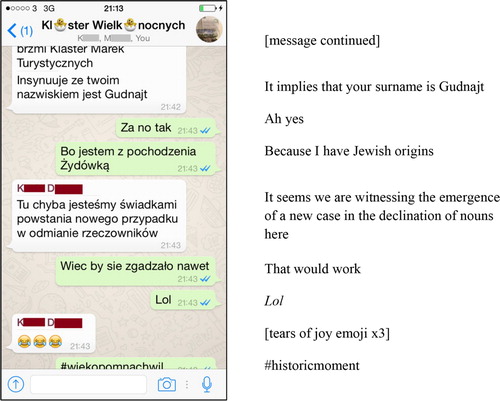

This extract (dated 14/04/2015-15/04/2015) is from Marta’s ongoing exchange in WhatsApp with former classmates on her translation diploma who shared an interest in language and in keeping up to date with changes to the Polish language (). Their semiotic repertoires thus overlapped in significant ways: all had access to a wide range of English-related resources, as well as Polish, and the linguistic terminology to discuss them; and they were actively and collaboratively engaged in expanding and updating their repertoires. In the extract, as part of this explicit repertoire assemblage, an image not only becomes a semiotic resource for meaning-making within (and eventually beyond) the moment of interaction, but serves as a means for generating other semiotic resources. These, in turn, serve to bolster their relationships and perform their linguistic and cultural identities.

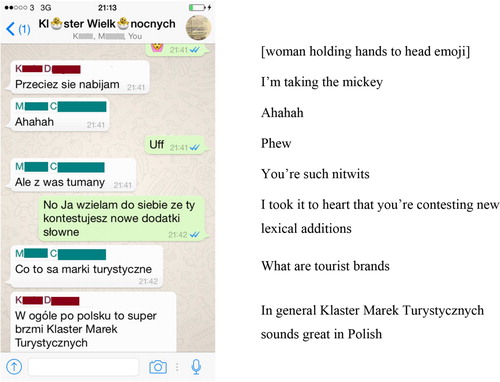

In and , Marta updates her two linguistically curious friends about the use of the word ‘klaster’ in Polish. Through sending a photo of the word used in a pamphlet, she brings her physical context to her digital interlocutors’ attention and invites them to share her perspective – and her embodied experience – through the use of gaze, proximity and choice of frame (cf. Jones, Citation2019; Zhao & Zappavigna, Citation2018). The Polish title on the pamphlet translates as ‘Collection of Polish tourist brands’. Marta draws her friends’ attention to the word ‘klaster’ (Tak- ‘KLASTER’) in order to ironically suggest that it is not a true Polish word but an Anglicised one (Piekne polskie slowo – ‘Beautiful Polish word’). As if to parallel this Anglicisation, Marta then uses a similarly Anglicised Polish ‘hybrid’ word zabdejtujcie (a Polish respelling of ‘update’ + Polish prefix z- + Polish suffix –ujcie) to suggest her friends ‘update their brains’ with this new language use, marking her suggestion as playful with the English-derived acronym Lol. By holding up an instance of language use for evaluation, Marta is engaged in the self-assigned task of explicitly expanding the group’s semiotic repertoire, adding a serious element to what is framed as an everyday performance.

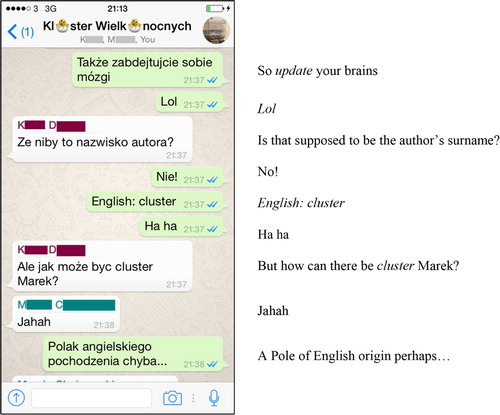

However, Klara subverts Marta’s intended objective by picking up on other aspects of the language used, recasting Klaster as a surname (a suggestion also motivated by the fact that Marek is a Polish name, the equivalent of English ‘Mark’). Her suggestion is grammatical, rather than lexical. Whilst acknowledging the joke (Ha ha), Marta refutes Klara’s interpretation (Nie!) and reasserts her own (English: cluster). Nonetheless, Klara pursues her interpretation, asking Ale jak moze byc cluster Marek? (‘But how can there be cluster Marek?’) – that is, a cluster of Marek. Marta finally picks up on her friend’s attempt at a joke (Polak angielskiego pochodzenia chyba, ‘A Pole of English origin perhaps … ’). Although her utterance has potential relevance for their own identities as Londoners from Poland, it appears primarily intended as a playful comment on language form, rather than an attempt to index social meaning. Importantly, its utterance at this moment in the unfolding interaction links back to the photo and the multilingual language play in processes of synchronised and local chaining across modalities and two named languages.

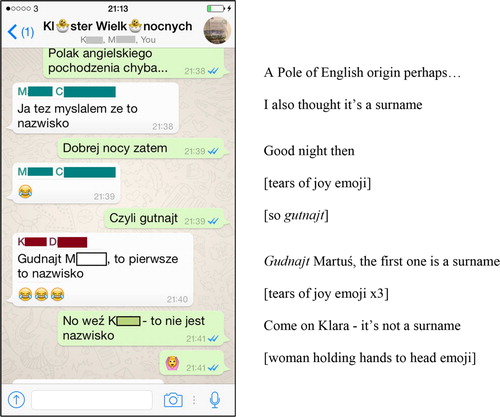

When Marcel also picks up on Klara’s interpretation, first laughing (Jahah) and then agreeing (Ja tez myslalem ze to nazwisko, ‘I also thought it was a surname’), Marta performs an act of dismissal or resignation (Dobrej nocy zatem, ‘Good night then’) (). Her recasting of this message in English written according to the rules of Polish orthography (gutnajt) is a reference back to her point regarding Klaster. Again, Klara puts her own spin on it, by wishing her friend Gudnajt Martuś before pointing out that gudnajt in this construction must be a surname according to her new grammatical rules (thus making a parallel between Gudnajt Martuś and Klaster Marek). Marta’s subsequent emoji selection (depicting a woman holding her head in her hands) visually reinforces the frustration expressed verbally (No weź Klara – ‘Come on Klara’) by suggesting the nonverbal action she could be performing in response to Klara’s contributions (Herring & Dainas, Citation2017). Marta’s emoji thus serves as a potential trigger for her friends to visualise her physical response to the situation (Lyons, Citation2014, Citation2018). This brief window into her immediate physical context – and the likely playfulness of the graphicon (Hsieh & Tseng, Citation2017) – works to bridge the physical distance and thus increase social proximity.

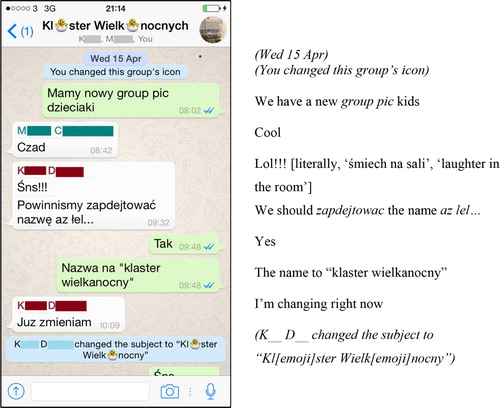

Klara’s insistence on her grammatical interpretation of Marta’s language point comes to a head in her declaration Tu chyba jesteśmy świadkami powstania nowego przypadku w odmianie rzeczowników (‘It seems we are witnessing the emergence of a new case in the declination of nouns here’, ). Although not making much sense grammatically, Klara’s declaration refers to her grammatical interpretation of Klaster marek turystycznych in their previous discussion and relates to their identities as language specialists. This, according to Marta, is a #wiekopomnachwil (‘#historicmoment’), a humorous reference to a classic Polish film ‘Sami Swoi’. The inclusion of a hashtag suggests an affective alignment around a shared cultural value – in other (more public) contexts, hashtags are used to align around shared affective stances and collective understandings (Bourlai, Citation2018). In analogy with tagging on Twitter (cf Lee, Citation2018; Zappavigna, Citation2012), the referential meaning of the phrase suggests that the remark is of wider relevance, whilst simultaneously heightening the intended irony: their off-the-cuff banter does not equate to a socially important event.

Interestingly, the following day, the emergence of Klara’s faux new case becomes a semiotic resource for group meaning-making in an instance of activity-chaining (Bagga-Gupta, Citation2017), as the friends rename their WhatsApp group (dated 15/04/2015). The online space is constructed through the use of in-built tools, including group image icon and name choice, which can be changed to reflect the subject of the ongoing conversation. Although clearly marked through font size and background colour as automated information referring to space modification, messages about these changes appear on the screen and, as such, form part of the ongoing conversation flow and are referred to in the interaction itself.

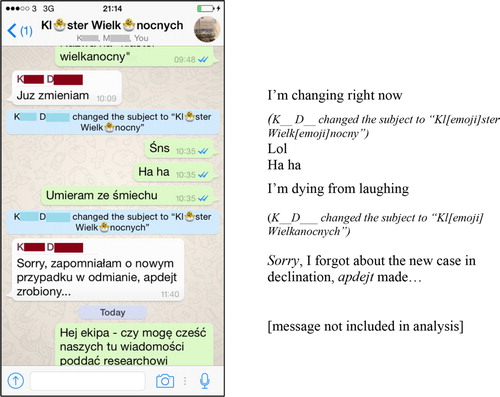

In this case, the changes to the group name pick up on the semiotic resources co-constructed the previous day: the group was at the time labelled Wielkanocny (‘Easter’) and as this interaction unfolds the friends change it first to Klaster Wielkanocny and then to Klaster Wielkanocnych, with embedded emoji playfully signalling Easter. Their previous exchange is also referenced in the conversation that occurs around these name changes. Klara announces Powinnismy zapdejtować nazwę az łel (‘We should update the name as well’), picking up on Marta’s use of the Anglicized zapdejtować – as with apdejt (‘update’) in a subsequent turn. She also reflects Marta’s earlier spelling of Gudnajt with the Polish spelling of the English ‘as well’ (az łel) and then picks up on her earlier declaration of a ‘new case in declination’ (nowym przypadku w odmianie). Here, we see a complex chaining of resources across the trajectory of the group’s ongoing interactions, as their co-construction of the new case – an emergent resource – draws simultaneously on multiple named languages and modalities whilst linking back across previous episodes of multilingual and multimodal language play to Marta’s initial posting of the image.

These communication phenomena are not new: repetition has long been recognised as an important interpersonal resource which structures everyday conversation (Tannen, Citation1984) and enables the (re)forming of patterns (Carter, Citation2004), while the development of in-group resources is an established humour strategy. However, by reconceptualising these observations as instances of chaining and repertoire assemblage, we can see that, while participants have shared access to Polish, English, a metalinguistic vocabulary, and a range of digital literacy resources, their semiotic resources can also be co-created through interaction, shaped and facilitated both by the technological affordances of the digital space and the physical contexts in which interlocutors are situated. New forms emerge through language play and are given particular meanings as the group builds on and exploits them as resources for interpersonal bonding and identity construction. In this case, the repertoire assemblage is explicit and subject to metalinguistic comment and critique. Elsewhere, as with Edyta and her interlocutors, this process remains implicit and unremarked upon.

Meet at the pub?

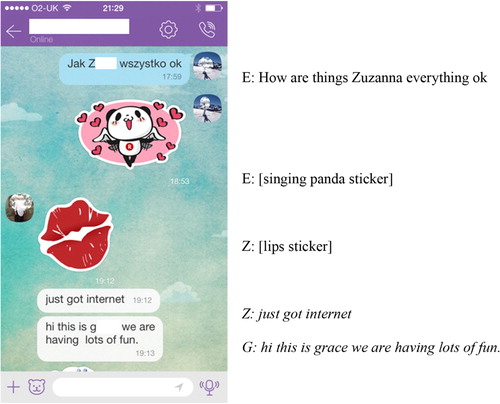

Below we analyse an exchange between Edyta and her daughter, Zuzanna (dated 27/11/2014). Edyta kept in contact with her daughter through mobile messaging when she was at the shop and Zuzanna was home from school. It seems their preferred social medium was Viber, a popular mobile messaging app with a particularly wide array of features including text messages, photo messages, video messages and location sharing (Sutikno et al., Citation2016).

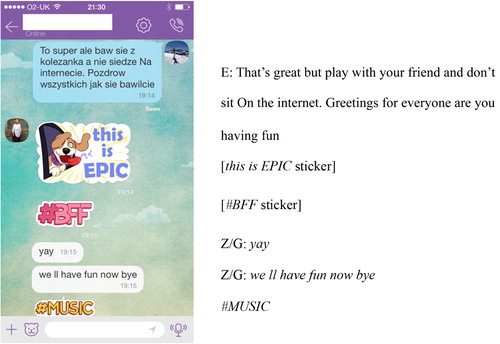

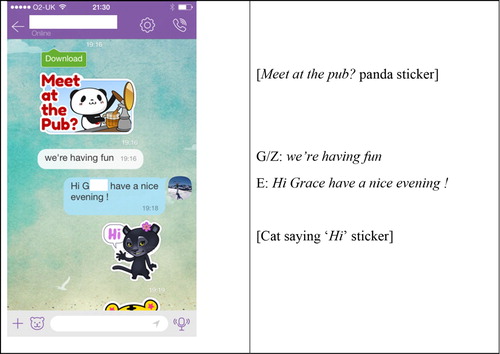

The analysed exchange took place between Edyta and Zuzanna during Zuzanna’s sleepover at her English-speaking friend Grace’s house (). Our focus is on the interlocutors’ use of ‘stickers’, one set of preconfigured resources in the form of ‘elaborate, character-driven illustrations or animations to which text is sometimes attached’ (Konrad et al., Citation2020, p. 217) made available through messaging apps. Unlike emoji, stickers are not supported by Unicode nor standardised, meaning there are no restrictions on their creation or production, potentially limiting the development of widespread conventions of use (Seargeant, Citation2019, p. 19). In our dataset, stickers occur in the vast majority of messages sent though Viber, and the fact that they occur mainly in interactions with Zuzanna, friends and certain customers suggests that, as likely intended by their designers, they index close, friendly and informal relations.

In , Edyta begins the conversation in an informal and intimate register of Polish which reflects her usual digital language practices. Her verbal ‘check-in’ (Rainie & Wellman, Citation2012), Jak Zuzanna wszystko ok (‘How are things Zuzanna everything ok’) is followed up nearly an hour later when Zuzanna does not reply. The modal shift from written Polish to a sticker means that Edyta can draw on the meaning afforded by image in contrast with text – probably the more indirect or equivocal conveying of emotion (Takahashi, Citation2014, p. 200) – and on the particular associations that stickers have accrued in the course of these interlocutors’ interactional history. In this instance, the sticker apparently serves to attract Zuzanna’s attention and to prompt her to reply, without explicitly demanding that she do so. This can be seen as fulfilling a pragmatic function of ‘softening’ (Herring & Dainas, Citation2017) and might be experienced as non-face-threatening, thus enhancing communicative fluidity (Lim, Citation2015). The semantic content of this particular sticker selected from the wider set – hearts surrounding a singing panda – corresponds to the immediate pragmatic meaning, serving to further soften Edyta’s imposition on her daughter whilst indexing their close relationship – conveying, in Takahashi’s (Citation2014, p. 200) words, ‘a form of indirect phrasing showing her love’.

Zuzanna responds with a sticker representing a kiss (likely to be interpreted as a virtual action according to Herring & Dainas, Citation2017), acknowledging her mother’s sticker and matching its pragmatic connotation, before explaining her lack of response using verbal English language resources. This linguistic choice is motivated not by the nature of her relationship with her mother – Edyta reports that she usually communicates with Zuzanna in Polish (Hua et al., Citation2015) – but by her response to the physical space where she is situated – her English-speaking friend Grace’s house. This physical context – and the linguistic choices it entails – is also brought into the conversation through a message apparently written by Grace using Zuzanna’s phone (hi this is grace, ) and understood as such by Edyta (Hi Grace have a nice evening!, ). In these ways, the chained use of more than one named language and modality within this digital interaction is shaped by parallel online contexts and ongoing offline activities.

The exchange continues as follows in and . Edyta again messages in Polish (her message may have crossed with Grace’s), and the girls (probably Zuzanna) immediately respond with multiple turns containing a stream of stickers. In the course of these turns, we see an apparent loosening of the relationship between the semantic and pragmatic meanings that the stickers imply: while the verbal message in the dog-sticker sent by Zuzanna – this is EPIC – serves to respond to Edyta’s question about whether they are having a good time, the subsequent semantic content (#BFF, #MUSIC and Meet at the Pub?) appears increasingly less directly relevant but rather intended to indirectly index a particular mood or stance (cf Takahashi, Citation2014), namely the intimate and light-hearted atmosphere of the sleepover. In this case, the stickers likely provide an easier and arguably more effective way of reconstructing the contextual ambience than a verbal description. As in Marta’s exchange with her friends, the semiotic use of hashtags rests on a shared (or assumed) understanding of the wider significance of the digital resource. Through the hashtags #BFF and #MUSIC, the interactants draw not only on their annotating function to define the context in which the stickers are to be interpreted (Lee, Citation2018; Zappavigna, Citation2012) but also, as in Marta’s exchange, on their interpersonal function of enabling alignment around shared stances (Bourlai, Citation2018). By playfully drawing on and extending this shared element of their repertoires, Zuzanna works to decrease the physical distance with her mother by heightening their social intimacy (Janssen et al., Citation2014).

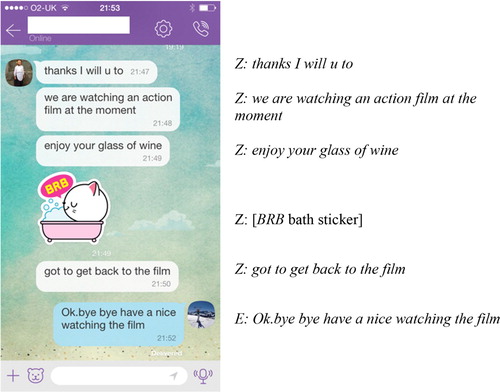

The sticker Meet at the pub stands out because of its apparent inappropriateness in the context of this conversation between a mother and her 10-year-old daughter (who would not typically meet her mother in a pub). However, the pragmatic significance of this sticker is primed by the preceding stickers, in that together they signal an outpouring of affection – a kind of ‘riffing’ (Herring & Dainas, Citation2017), perhaps, or an intimate form of ecstatic sharing focused on ‘the affective intensity of the here-and-now’ (Giaxoglou, Citation2018, p. 19). In this context, the pragmatic meaning of the pub sticker arises from a contrast between its locally conventionalised role in signalling casual social relations and its immediate irrelevance to this conversation with her daughter. The arbitrary symbolic nature of the sticker is thus central to its meaning in this unfolding interaction. As this suggests, the stickers that appear throughout this exchange are used variously as iconic signs – as in the ‘singing panda with hearts’ sticker, this is EPIC and BRB in the final extract of the exchange (), in which the sticker semantics correspond to varying degrees to its pragmatic meaning – and as conventionalised symbols whose form and content is more arbitrarily related to the intended pragmatic meaning. This latter use appears to take advantage of the potential ambiguity of graphicons, suggesting this as a strength rather than an impediment to effective communication (Pohl et al., Citation2017).

This emergent symbolic use appears to reflect a shift in what and how stickers mean to this network of Viber users, to the point where it is the random or clever choice of sticker, rather than its actual content, which comes to take on interpersonal meaning (cf Konrad et al., Citation2020). There are parallels between this symbolic use of stickers, and Marta’s and her interlocutors’ playful focus not on ideational content but on the interpersonal significance of playing around with form, a complex local chaining across modalities.

Conclusion

This article explored moments of interaction as they unfolded in mobile messaging exchanges between Polish women living and working in London and their interlocutors. Building on the argument that semiotic repertoires are neither static nor predetermined but are shaped by the immediate space and co-constructed in interaction, we adopted a moment analysis approach to trace how repertoire assemblage takes place in the course of everyday actions through processes of chaining, shaped by the affordances of the digital space. Interestingly, in both exchanges these meanings often emerged from randomness; that is, their randomness was inherent to their meaning, something we also observed elsewhere in the data. In Edyta’s exchanges, stickers acquired pragmatic meanings that not only arbitrarily related to the semantic content of the sticker, but drew on this random association for meaning. In Marta’s case, new semiotic resources emerged through the explicit and playful manipulation of language forms which were selected and held up for evaluation. As the friends appropriated, negotiated and contested their interlocutors’ metalinguistic comments, not only did semiotic resources come to take on new meaning, but new language forms emerged and became available for subsequent meaning-making within the group. Previous research has shown how repertoires are constructed over an individual’s lifetime, and how the deployment of resources is shaped in part by the social space and the relationships between interlocutors. Our analysis shows how interlocutors collaborate in the co-creation of semiotic resources, leading to an in-the-moment assemblage of repertoire distributed across participants. This highlights that the dynamic nature of the semiotic repertoire must be understood and investigated at an interactional level.

Our post-digital linguistic ethnographic approach allows us to situate these instances of repertoire assemblage within the wider picture of these women’s post-migration lives, social networks and identity projects. The negotiation and jostling of resources in the context of a micro-level interaction feeds into macro-level changes in a migrant’s repertoire as they adapt to the dominant language of their host country and negotiate their own post-migration identities. In Edyta’s case, reconfiguration of the social space prompted by the presence of her daughter’s English-speaking friend Grace sanctions the use of English-oriented resources with which Edyta is less comfortable and which forces her to reposition herself sociolinguistically (Busch, Citation2014). This is a fleeting but potentially transformational moment in which Edyta adjusts to the developing social reality in which she and her daughter interact, with implications for how Edyta positions herself as a Pole living and working in London and as the mother of a bilingual daughter. In the case of Marta and friends, their playful manipulation of Polish-related resources is driven and shaped by perceived tensions between Polish and English, which are central to their reimagining of themselves as linguistically aware Polish-speaking Londoners. Like Edyta, Marta repositions herself through her everyday interactions; in contrast to Edyta, she is not only defined by linguistic and cultural boundaries, but is engaged in actively and knowingly challenging and reshaping them. Our analysis thus highlights the importance of everyday repertoire assemblage in understanding wider social processes, structures and transformation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Translation and Translanguaging: Investigating Linguistic and Cultural Transformations in Superdiverse Wards in Four UK Cities, 2014-2018. (AH/L007096/1). Angela Creese (PI). With CIs Mike Baynham, Adrian Blackledge, Frances Rock, Lisa Goodson, Li Wei, James Simpson, Caroline Tagg, Zhu Hua.

References

- Androutsopoulos, J. (2008). Potentials and limitations of discourse-centred online ethnography. Language@Internet, 5, article 9.

- Androutsopoulos, J. (2014). Moments of sharing: Entextualisation and linguistic repertoires in social networking. Journal of Pragmatics, 73, 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2014.07.013

- Androutsopoulos, J. (2015). Networked multilingualism: Some language practices on Facebook and their implications. International Journal of Bilingualism, 19(2), 185–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006913489198

- Androutsopoulos, J. (2019, June 6–7). Mediational repertoires and diasporic connectivity: From Senegal to Oslo and back again. Keynote paper presented at Digital Diasporas: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, University of Westminster, London.

- Androutsopoulos, J., & Juffermans, K. (2015). Digital language practices in superdiversity: Introduction. Discourse, Context & Media, 4–5, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2014.08.002

- Apter, E. (2006). The translation zone. Princeton University Press.

- Bagga-Gupta, S. (2017). Going beyond oral-written-signed-irl-virtual divides: Theorizing languaging from mind-as-action perspectives. Writing and Pedagogy, 9(1), 49–75. https://doi.org/10.1558/wap.27046

- Bagga-Gupta, S., Messina Dahlberg, G., & Gynne, A. (2019). Handling languaging during empirical research: Ethnography as action in and across time and physical-virtual sites. In S. Bagga-Gupta, G. Messina Dahlberg, & Y. Lindberg (Eds.), Virtual Sites as Learning spaces (pp. 331–382). Palgrave.

- Barry, A. (2013). The translation zone: Between actor-network theory and international relations. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 41/3(3), 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305829813481007

- Bassnet, S. (2014). Translation. Routledge.

- Blackledge, A., & Creese, A. (2018). Interaction ritual and the body in a city meat market. Social Semiotics, 30(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2018.1521355

- Blommaert, J., & Backus, A. (2013). Superdiverse repertoires and the individual. In I. de Saint-Georges, & J.-J. Weber (Eds.), Multilingualism and multimodality: Current challenges for educational studies (pp. 11–32). Sense Publishers.

- Bourlai, E. (2018). ‘Comments in tags, please!’: Tagging practices on Tumblr. Discourse, Context & Media, 22, 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2017.08.003

- Busch, B. (2014). Building on heteroglossia and heterogeneity: The experience of a multilingual classroom. In A. Blackledge, & A. Creese (Eds.), Heteroglossia as practice and pedagogy (pp. 21–40). Springer.

- Carter, R. (2004). Language and creativity: The art of everyday talk. Routledge.

- Chen, Z., Lu, X., Shen, S., Ai, W., Liu, X., & Mei, Q. (2018, April 23–27). Through a gender lens: Learning usage patterns of emojis from large-scale Android users. WWW ‘18: Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference (pp. 763–772).

- Cohen, D. (2015). World attending in interaction: Multitasking, spatializing, narrativizing with mobile devices and Tinder. Discourse, Context & Media, 9, 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2015.08.001

- Cramer, F. (2015). What is ‘post-digital’? ARRJA, 3(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137437204_2

- Cronin, M., & Simon, S. (2014). Introduction: The city as translation zone. Translation Studies, 7(2), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2014.897641

- Djonov, E., & van Leeuwen, T. (2017). The power of semiotic software: A critical multimodal perspective. In J. Flowerdew, & J. E. Richardson (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of critical discourse studies (pp. 566–581). Routledge.

- Dovchin, S., Pennycook, A., & Sultana, S. (2018). Popular culture, voice and linguistic diversity: Young adults on- and offline. Palgrave.

- Ge, J., & Herring, S. C. (2019). Communicative functions of emoji sequences on Sina Weibo. First Monday, 23, 11. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v23i11.9413

- Georgakopoulou, A. (1997). Self-presentation and interactional alignments in e-mail discourse: The style and code-switches of Greek messages. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 7(2), 141–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.1997.tb00112.x

- Giaxoglou, K. (2018). #JeSuisCharlie? Hashtags as narrative resources in contexts of ecstatic sharing. Discourse, Context & Media, 22, 13–20.

- Grossman, E. (2010). Why translation matters. Yale University Press.

- Herring, S. C., & Dainas, A. (2017, January 4–7). ‘Nice picture comment!’ Graphicons in Facebook comment threads. Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (pp. 2185–2194).

- Hsieh, S. H., & Tseng, T. H. (2017). Playfulness in mobile instant messaging: Examining the influence of emoticons and text messaging on social interaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 405–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.052

- Hua, Z., Wei, L., & Lyons, A. (2015). Language, business and superdiversity in London: Translanguaging Business. Working Papers in Translanguaging and Translation (WP. 5).

- Hua, Z., Wei, L., & Lyons, A. (2016). Playful subversiveness and creativity: Doing a/n (Polish) artist in London. Working Papers in Translanguaging and Translation (WP. 16).

- Hua, Z., Wei, L., & Lyons, A. (2017a). Polish shop(ping) as translanguaging space. Social Semiotics, 27(4), 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2017.1334390

- Hua, Z., Wei, L., & Lyons, A. (2017b). Intercultural moments in translating the socio-legal systems. Working Papers in Translanguaging and Translation (WP. 35).

- Janssen, J. H., IJsselsteijn, W. A., & Westerink, J. H. D. M. (2014). How affective technologies can influence intimate interactions and improve social connectedness. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 72(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2013.09.007

- Jones, R. (2019). Towards an embodied visual semiotics: Negotiating the right to look. In C. Thurlow, C. Dürscheid, & Diémoz (Eds.), Visualising digital discourse: Interactional, insitutional and ideological perspectives (pp. 19–42). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Jonsson, K., & Muhonen, A. (2014). Multilingual repertoires and the relocalization of manga in digital media. Discourse, Context & Media, 4–5, 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2014.05.002

- Konrad, A., Herring, S. C., & Choi, D. (2020). Sticker and emoji use in Facebook Messenger: Implications for graphicon change. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 25(3), 217–235. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmaa003

- Kusters, A., Spotti, M., Swanwick, R., & Tapio, E. (2017). Beyond languages, beyond modalities: Transforming the study of semiotic repertoires. International Journal of Multilingualism, 14(3), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2017.1321651

- Lebefvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Blackwell.

- Lee, C. (2018). Introduction: Discourse of social tagging. Discourse, Context & Media, 22, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2018.03.001

- Lim, S. S. (2015). On stickers and communicative fluidity in social media. Social Media + Society, 2015, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115578137

- Lyons, A. (2014). Self-presentation and self-positioning in text-messages: Embedded multimodality, deixis, and reference frame. London: School of Languages, Linguistics & Film, Queen Mary University of London PhD thesis.

- Lyons, A. (2018). Multimodal expression in written digital discourse: The case of kineticons. Journal of Pragmatics, 131, 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2018.05.001

- Lyons, A., & Ounoughi, S. (2020). Towards a transhistorical approach to analysing discourse about and in motion. In C. Tagg, & M. Evans (Eds.), Message and medium: English language practices across old and new media (pp. 89–111). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Markham, A. (2003). Critical junctures and ethical choices in internet ethnography. In M. Thorseth (Ed.), Applied ethics in internet research (pp. 51–63). NTNU University Press.

- Marsh, J. (2019). Researching young children’s play in the post-digital age. In N. Kucirkova, J. Rowsell, & G. Falloon (Eds.), The routledge international handbook of learning with technology in early years (pp. 157–169). Routledge.

- McSweeney, M. (2018). The pragmatics of text messaging: Making meaning in messages. Routledge.

- Miller, D., & Sinanan, J. (2014). Webcam. Polity.

- Panckhurst & Frontini. (2019). Evolving interactional practices of emoji in text messages. In C. Thurlow, C. Dürscheid, & Diémoz (Eds.), Visualising digital discourse: Interactional, insitutional and ideological perspectives (pp. 81–104). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Papacharissi, Z. (Ed.). (2010). A networked self: Identity, community, and culture on social network sites. Routledge.

- Pennycook, A. (2018). Posthumanist applied linguistics. Applied Linguistics, 39(4), 445–461. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amw016

- Pennycook, A., & Otsuji, E. (2015). Metrolingualism: Language in the city. Routledge.

- Pohl, H., Domin, C., & Rohs, M. (2017). Beyond just text: Semantic emoji similarity modeling to support expressive communication. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 24(1), Article 6. https://doi.org/10.1145/3039685

- Rainie, L., & Wellman, B. (2012). Networked: The new social operating system. MIT Press.

- Rymes, B. (2014). Marking communicative repertoire through metacommentary. In A. Blackledge, & A. Creese (Eds.), Heteroglossia as practice and pedagogy (pp. 301–316). Springer.

- Seargeant, P. (2019). The emoji revolution: How technology is shaping the future of communication. Cambridge University Press.

- Sutikno, T., Handayami, L., Stiawan, D., Riyadi, M. A., & Subroto, I. M. I. (2016). Whatsapp, Viber and Telegram: Which is the best for instant messaging? International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering, 6(3), 909–914. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijece.v6i3.10271

- Tagg, C., & Hu, R. (2015, November 13). Bilingual researchers as intermediaries of translation in a research team’. Paper presented at The Multilingual University, ESRC-funded seminar, University of Birmingham.

- Tagg, C., & Hu, R. (2017). Sharing as a conversational turn in digital interaction. Working Papers in Translanguaging and Translation (WP29).

- Tagg, C., & Lyons, A. (forthcoming). Polymedia repertoires of networked individuals: A day-in-the-life approach. Pragmatics and Society.

- Tagg, C., Lyons, A., Hu, R., & Rock, F. (2017). The ethics of digital ethnography in a team project. Applied Linguistics Review, 8(2–3), 271–292. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2016-1040

- Takahashi, T. (2014). Youth, social media and connectivity in Japan. In P. Seargeant, & C. Tagg (Eds.), The language of social media: Identity and community on the internet (pp. 186–207). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tang, Y., & Hew, K. F. (2019). Emoticon, emoji, and sticker use in computer-mediated communication: A review of theories and research findings. International Journal of Communication, 13, 2457–2483.

- Tannen, D. (1984). Talking voices: Repetition, dialogue and imagery in conversational discourse. Cambridge University Press.

- Vold Lexander, K., & Androutsopoulos, J. (2019). Working with mediagrams: A methodology for collaborative research on mediational repertoires in multilingual families. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2019.1667363

- Wang. (2016). More than words? The effect of line character sticker use on intimacy in the mobile communication environment. Social Science Computer Review, 34(4), 456–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439315590209

- Wei, L. (2011). Moment analysis and translanguaging space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(5), 1222–1235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.035

- Zappavigna, M. (2012). Discourse of Twitter and social media: How we use language to create affiliation on the web. Bloomsbury.

- Zhao, S., & Zappavigna, M. (2018). Beyond the self: Intersubjectivity and the social semiotic interpretation of the selfie. New Media & Society, 20(5), 1735–1754. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817706074