ABSTRACT

In the current revival of Gumperz’ notion of the verbal repertoire, which today is rather termed as communicative or semiotic repertoire, some scholars tend to locate repertoires with individual speakers whereas others see them primarily as emerging from particular spatial arrangements. What is often underestimated in both approaches is the importance of the bodily and emotionally lived experience of communicative interaction. This experience, however, can be critical in preventing resources from being deployed even though they are individually available and appropriate to the situation as well as in mobilising unexpected resources to achieve understanding. Conceiving the repertoire as holding an intermediate and mediating position between situated interactions, (sometimes competing) discourses, and subjects’ lived experiences of communicating, in this paper, I examine the interplay of these instances by introducing the notion of the ‘body image’: an imaginary, affectively loaded representation of the own body in relation to others. Finally, I discuss the language portrait (in which participants visualise their semiotic resources with reference to the outline of a body silhouette) as a window onto the body image and as a method to empirically investigate how people evaluate their resources and position themselves with regard to ideologies of communication.

Introduction

In the current revival of Gumperz (Citation1964) notion of the verbal repertoire, which today is rather labelled as linguistic or communicative or semiotic repertoire, some scholars tend to locate the repertoire with individual speakers and their life trajectories, whereas others see it primarily as emerging from particular social or spatial arrangements in which interactions take place. Also, when conceptualising repertoires as spatial, authors bring in the notion of a personal repertoire (Canagarajah, Citation2018; Pennycook, Citation2014) to conceptualise the resources participants have acquired along their life trajectory. These personal resources, however, seem to be more than a toolbox from which one can choose according to the needs of the moment, as sometimes there is a perceivable gap between acquired and accessible resources.

The underlying problem is that the repertoire is not an object or a fact that can be perceived by itself and that it, therefore, is difficult to grasp empirically. Only approximations are possible and these can be achieved from different perspectives: (i) a focus on interaction (methodologically corresponding to interactional linguistics and conversation analysis) that concentrates on the observation of situated communicative events and helps to understand how repertoires are enacted and contextually specified in situ, and how communicators position themselves and align with each other; (ii) a focus on discourse (methodologically, this corresponds to discourse analysis and language ideology research) primarily interested in enregistered ideologies of communication (Spitzmüller, Citationaccepted) and in particular in metadiscourses on language and language use; (iii) a focus on the subject (methodologically corresponding to phenomenological, language biographical approaches and positioning theory) that foregrounds how people experience and evaluate their communicative resources in relation to others and to language ideologies, and how such bodily-emotional experiences condensate into what can be called the body image. Aiming at shedding some light on what impacts on whether a person’s acquired resources are actually accessible or remain sealed in a particular communicative event, it is the third of these perspectives that I concentrate on in this contribution.

As I developed earlier (Busch, Citation2012, Citation2017a), the repertoire should not simply be understood as located ‘in’ the individual speaker nor as determined by particular time–space constellations regimented by certain expectations and rules, nor as emerging from a particular interactional event. Instead, repertoires can be conceived of as holding an intermediate and mediating position between interactions situated in time and space, (sometimes competing) discourses on linguistic appropriateness, and subjects’ emotionally and bodily lived experience of language. With this conceptualisation, I draw on approaches to studying phenomena of language and language practices as developed in literary theory, philosophy and sociology: especially, on Bakhtin’s (Citation1981, p. 294) dialogic principle that conceives language as lying ‘on the borderline between oneself and the other’; on Merleau-Ponty’s (Citation1962) phenomenology of perception that understands language as an intersubjective, inter-corporeal gesture; and on Bourdieu’s (Citation1991) practice theory which understands language use as a component of the habitus that ties actors to specific practices and social spaces shaped by power relations.

When discussing semiotic repertoires beyond the strictly verbal, bodies and embodiment need special attention. So far, however, these phenomena have – with some exceptions (e.g. Busch, Citation2017a; Kusters & De Meulder, Citation2019; Rymes, Citation2014) – rarely been treated explicitly in connection with the repertoire. Investigating this connection, in this contribution, I will argue that bodies do not only matter on the level of how they are deployed in interactions and how they are conceived of in enregistered discourses, but also on the level of embodied experience. To get a better understanding of how embodied experience and enregistered discourses impact on repertoires deployed in interaction, I suggest to introduce the notion of the body image understood as an imaginary (mostly not conscious) representation of the embodied self in interaction with others and the world – a notion borrowed mainly from phenomenology. Empirically, approximations to the body image can be made through biographical work; among others through the language portrait (LP), a creative visual method that I will discuss later in this contribution.

Why bodies matter

For a long time, physical and/or emotional aspects were considered mainly as epiphenomena in the analysis of communicative acts. Only more recently, a number of approaches have appeared in sociolinguistics and in applied linguistics which, although committed to different theoretical and methodological orientations, concur in moving the idea of the subject as being bodily and emotionally involved in interactions with other subjects, to the centre of their interest (Busch, Citation2020). The recent focus on the role of bodies and affects in sociolinguistics, conversation analytical and discourse analytical research correlates with an understanding of meaning-making as a cooperative, dialogical process across different modes and sign systems (including making use of objects and spatial arrangements). This entails a growing interest in the ‘material’ quality and the spatial embeddedness of the linguistic/communicative sign as emphasised in ‘post-human’ and process-based approaches that embrace a ‘concept of affective practice’ (Wetherell, Citation2012, p. 3). In Mondada’s (Citation2016) words, the challenge confronted is to overcome ‘a logo-centric vision of communication, as well as a visuo-centric vision of embodiment’ (p. 336). However, this re-orientation is still in its early stages and, as noted by Bucholtz and Hall (Citation2016), current sociocultural linguistics is lacking a broad discussion about the theoretical relationship between language and embodiment. As already noted above, looking at semiotic repertoires beyond a logocentric understanding of communication requires paying special attention to bodies and embodiment; and attention devoted to different levels: to (i) the level of situated interaction in which bodies are involved in (dialogic) meaning-making; (ii) the level of discourses and ideologies that link enregistered expectations on communicative practices and physical appearances to typified social personae; and (iii) the level of subjects experiencing and evaluating their bodily being in relation to others.

In the observation of situated communicative events at the micro-level, several scholars have looked at bodies and emotions as resources on which actors rely in dialogical processes of meaning-making. An early point of reference is Goffman’s work, who in his seminal book ‘The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life’ (Citation1959) drew attention to the importance of bodily and emotional aspects in face-to-face encounters. In his view, individuals try to control the impressions others receive of the self in a situation. Goffman is mainly concerned with the participants’ staging problems and the techniques they employ to sustain the intended impressions. He addresses the bodily dimension of social interaction under the term social portraiture. This refers to ‘individuals’ use of ‘faces and bodies’ in social situations’ (Goffman, Citation1979, p. 6) so as to present themselves in the way they want to be seen. In doing so, individuals are seen to be drawing on models provided, e.g. by commercial advertisements. Duranti’s (Citation1992) pioneering anthropological study based on audio-visual recordings of ceremonial greetings in Western Samoa investigates ‘the interpenetration of words, body movements, and living space in the constitution of a particular kind of interactional practice’ (p. 657). He pays special attention to sighting, conceived of as an interactive step by which interactants engage in a process of negotiation that results in their finding themselves physically located in the relevant social hierarchies. With his empirical findings, Duranti (Citation1992) contests the idea of supremacy of the verbal mode: ‘The body (e.g. body postures, gestures, eye gaze) not only provides the context for interpretation of linguistic units (words, morphemes, etc.), as argued by linguists working on deixis, but helps fashion alternative, sometimes complementary, sometimes contradictory messages’ (p. 663). Goodwin (Citation2000), in his famous and detailed analysis of the video recording of a conflictual interaction between three young girls playing hopscotch, shows how the participants deploy a range of different semiotic resources and that their gestures are not necessarily ‘simply a visual mirror of the lexical content of the talk, but a semiotic modality in their own right’ (p. 1498). Thus, he pleads for an analysis of human action that ‘takes into account simultaneously the details of language use, the semiotic structure provided by the historically built material world, the body as an unfolding locus for the display of meaning and action, and the temporally unfolding organisation of talk-in-interaction’ (p.1517). These early works point to the fact that repertoires also encompass knowledge on how bodies are displayed and can be read in situated interactions.

This knowledge in turn is informed by discourse. Ways of positioning others and ourselves in situated interactions depend largely on ideologies of communication (Spitzmüller, Citationaccepted), including ideologies of how bodies are expected to look like, move, and act. Such expectations are based on assumptions of how a particular group should communicate ‘naturally’ (in specific contexts), as well as on (assumptions about) ‘natural’ links between embodied ways of communicating and typified social personae. Referring to Agha (Citation2007), the process of linking and ‘naturalising’ can be understood as enregisterment, a process by which communicative ‘difference’ gets tightly linked with social subjects, and often also projected onto them. Consequently, particular forms of communication might be construed as symptoms of bodily dispositions (Bucholtz & Hall, Citation2016). Such ideologies are extremely powerful as, regardless of whether one aligns or objects to them, one cannot evade them. They exert a performative constitutive power in the formation of the subject, as Butler (Citation1997) put forward. Ways of construing bodies (e.g. as female) are part of the process of becoming a subject. This process operates not only through disciplinary power, interdictions and restrictions but also by ‘technologies of the self’ used by human beings to address and understand themselves – to effect operations ‘on their own bodies and souls, thoughts, conduct, and way of being’ (Foucault, Citation1988, p. 17). Butler also refers to Bourdieu’s concepts of habitus, constituting ‘a tacit form of performativity, a citational chain lived and believed at the level of the body’ (Butler, Citation1997, p. 155). According to Bourdieu (Citation1991), speaking is always oriented towards a specific linguistic market. On this market, specific ways of speaking are evaluated according to their symbolic value and judged upon as acceptable or not, whereby the sense of acceptability which orients linguistic practices ‘is inscribed in the most deep-rooted of bodily dispositions’ (Bourdieu, Citation1991, p. 86). It is the whole body that is responding with its posture and inner articulary reactions. Through socialisation and habitualised practice, language becomes a ‘body technique’, ‘a life style ‘made flesh’’ (Bourdieu, Citation1991).

When focusing on the subject’s lived experience of interaction – a perspective taken, for example, by cognitive linguistics and phenomenology – we have to bear in mind that neither ‘subject’ nor ‘experience’ can be thought of as pre-given and outside of specific historical discourse and practice formations. While until very recently cognitive linguistics was mainly oriented towards mentalist theories locating language in the brain, there is an increasing recognition that the mind is inherently embodied and grounded in senso-motoric experience and in emotionally loaded intersubjective relation to others (Schwarz-Friesel, Citation2015). In this context, the work of Lakoff and Johnson (Citation1980) paved the way for a shift towards embodied cognition. In their view, which brings elements of Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological thinking to cognitive linguistics, the human conceptual system follows, to a considerable extent, processes of metaphor-formation through which the meaning of bodily lived experiences is transferred to other levels of thinking. Merleau-Ponty (Citation1962) sees the bodily being as the foundation of the subject. The body positions the subject in the world and the movement of the body is the basis of the faculty that allows us to relate to the world and engage with it. Language is thus, first and foremost, about projecting oneself towards the other – only then it is also a mental act of representation and symbolisation. ‘The spoken word is a genuine gesture, and it contains its meaning in the same way as the gesture contains it. This is what makes communication possible’ (Merleau-Ponty, Citation1962, p. 212). Through repeated interaction with other subjects and the world, the subject acquires what Merleau-Ponty calls a senso-motoric style, understood as ‘the power to respond with a certain type of solution to situations of a certain general form’ (p. 164). He makes a terminological distinction between the physical body [corps physique] as an object that is observable and measurable, and the living body [corps vivant] as the subject of perception, feeling, experience, action, and interaction. The ambiguity of the body as the simultaneously observing and observed, the affecting and affected, is illustrated with the example of the left subject hand that touches and feels the right object hand. In his later work, Merleau-Ponty (Citation1968) developed the notion of intercorporeity, meaning that subjects in interaction attune to one another. It is the shared experience of the reciprocity between the touched and the touching, between seeing and visible existence, that ‘founds transitivity from one body to another’ (p. 143). This reciprocity can be seen as the foundation for the search for common ground, for the deployment of a spatial repertoire.

Following these considerations, in connection with semiotic repertoires bodies matter in several respects: on the level of how they are deployed and read in situated interactions, on the level of how they are conceived of in enregistered discourses and not least on the level of bodily stored experiences. In what follows I will focus on this third level as this is so far the least discussed in sociolinguistics. I suggest to introduce the concept of the body image to grasp the aspect of repertoire that ‘sticks’ to the subject and that some authors refer to as the individual repertoire.

Introducing the notion of the body image

The notion of the body image is currently debated in different disciplines such as psychological, social, medical, and health sciences and has, to some extent, made its way also into more popular discourse. Since 2004, a special academic journal published by Elsevier under the title ‘Body Image’ serves as a forum to discuss the multi-facetted concept that refers to persons’ perceptions and attitudes about their own body (www.journals.elsevier.com/body-image/). The dominating topics in this journal are linked to satisfaction and dissatisfaction with body image and physical appearance (as eating disorders) as well as the effects of idealised body images created for and spread through social media and other channels. The current revival of the notion of body image and of concerns linked to body image disorders can be seen in connection with the neoliberal requirement for self-optimisation. Considering current developments, it may also be the case that the notion will gain further attention, as due to Corona-induced physical distancing, the role of the bodily presence for communication has become more tangible. First approaches to the idea of the body image already date back to the first half of the twentieth century, when psychoanalysts, psychologists, neuroscientists, and phenomenologically oriented philosophers engaged with what Schilder (Citation1935/2000), one of the main promotors of the concept, described as ‘the picture of our own body which we form in our mind, that is to say the way in which the body appears to ourselves’ (p. 11).

In the following, I will highlight some points raised in body image research that seem particularly relevant in connection with body dimensions of the repertoire.

Generally, the body image is defined in relation to what is called the body schema, which, seen from a neuroscience perspective, is a set of neural representations of the body and the bodily functions in the brain, a sort of inborn toolkit (Stamenov, Citation2005). Taking a psychodynamic-phenomenological position, Küchenhoff and Agarwalla (Citation2012) define the body schema as a figuration of the body composed of senso-motoric impressions. The body image by contrast is seen as an imaginary and evaluative representation of the own body.

Schilder (Citation1935/2000) already insisted on the social dimension of the body image. Depending on the disciplinary perspective, this social dimension is framed either in terms of the mirror neuron system, of intercorporeity, or of inter-human emotional relations. As explained above, the notion of intercorporeity draws on Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology. In this notion, intersubjectivity is less constituted by a mutual recognition of (visible or audible) similarities between two subjects, than by the directedness towards a common sharable object ‘found’ in the external world. Thus, the recognition of similarity is seen not as a precondition for intersubjectivity, but as a result of it (De Preester, Citation2005). From this point of view, the body as body image is not solipsistic, but a body-in-relation-to-others (Küchenhoff, Citation2013). Before we can verbalise our intention, we are already corporally tuned to the other, there is a kind of pre-reflexive intersubjectivity of the body. What cannot be verbalised can manifest itself as a somatic symptom. From a psychoanalytical perspective Dolto (Citation1984), one of the leading figures in body image research insists on the emotional dimension of the body image which she sees as ‘the synthesis of our emotional, inter-human, repetitively lived experiences’, as the ‘symbolic unconscious incarnation of the desiring subject [my translation]’ (p. 22).

Assuming that the body image is the synthesis of repeatedly lived inter-human experiences, Dolto sees it as an unconscious memory that is present in any relation in the here and now which can be expressed (or camouflaged) through language, mimics, gestures, artistic expression etc. Following Dolto (Citation1984), all contact with the other, whether this contact is communication or avoidance of communication, ‘is underpinned by the image of the body; for it is in the image of the body (…) that time intersects with space, that the unconscious past resonates in the present relationship [my translation]’ (p. 23). Similarly, Fuchs (Citation2011), drawing on Merleau-Ponty, analyses how in body memory situations and interactions experienced in the past fuse together and through repetition and superimposition, form a structure, a style that sticks to the subject – usually without the subject’s knowledge. According to Fuchs, body memory forms an ensemble of dispositions and potentials for perceiving the world, for social action, communication, and desire. It functions as an intersubjective system in which bodily patterns of interacting with others are established and constantly updated.

The development of the body image as an integrative structure starts from earliest childhood. Following Dolto, it accomplishes different tasks according to subsequent phases of a child’s development and aggregates into a dynamic image that is open to the unknown and corresponds to a ‘desire for being [my translation]’ (Dolto, Citation1984, p. 58). In the mirror stage of the infant, a holistic body image emerges from the specular image: the other is recognised as a whole and identified as oneself. But, as Dolto specifies, the mirror alone does not suffice – the subject needs to be reflected in the other.

The body image is seen as conveying a (somehow illusionary) imagination of consistency and continuity, but at the same time as subjected to changes and as potentially multiple. Dolto (Citation1984) reports the case of a girl that drew very different pictures of a bunch of flowers: one in full bloom, the other with withered flowers. Thanks to hints given by the girl, Dolto understands the drawings as two stages of the child’s body image: one as the expression of her right for narcissistic blooming, the other as altered by the presence of the mother.

To summarise, the body image can be thought of as an imaginary, emotionally highly loaded representation of one’s body in relation to others. It is developing from early childhood onwards and forming a mostly unnoticed and constantly updated matrix that ‘sticks’ to the subjects allowing them to imagine themselves in terms of biographical continuity and coherence. The social, intersubjective, relational, inter-human quality of the body image is seen as a central characteristic, as due to this quality, the body image is formed and transformed in interaction with others, having an impact on the subject’s way of interacting.

Not only when understanding the repertoire as an individual set of resources and competences but also in conceptualisations of spatial repertoires, all authors, in one way or another, refer to what individual participants ‘bring into’ situated interactions in terms of personal repertoire (Canagarajah, Citation2018; Pennycook, Citation2014), linguistic baggage (Blommaert, Citation2007), an individual’s communicative repertoire (Rymes, Citation2014), a subject’s repertoire (Blommaert & Backus, Citation2013), or individuals’ semiotic repertoires (Kusters et al., Citation2017). The underlying assumption is that when participants engage in communication as situated in space and time, they bring with them the history of their life trajectories. A history in the course of which they have not only acquired competences and abilities but have also made bodily and emotionally lived experiences of language and communication (Busch, Citation2017a). The crucial question then is what makes somebody's acquired individual resources available and accessible as spatial repertoires unfold. When we investigate this question, the need for the notion of body image becomes apparent, for it does not simply designate bundles of communicative resources to a repertoire one ‘has’, but encompasses an evaluative stance vis-à-vis such resources. Such evaluation does not only take place with regard to current interactions but also depends on (sometimes competing) language and communication ideologies to which one is exposed and pre-formed by the history of a subject’s emotional experience, mapping out a space of potentialities (desires, aspirations) and constraints (anxiety, insecurity).

Perceiving oneself in communication with others

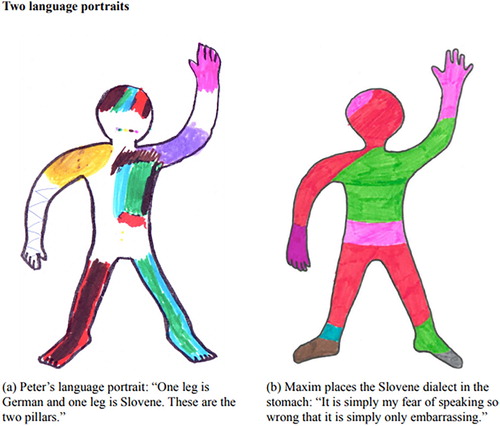

My interest in the body image stems from working with first-person accounts on language experience and in particular with the so-called language portrait in which participants visualise their communicative resources with reference to the outline of a body silhouette (see ). To present the LP approach and to discuss what empirical work with LPs can offer in connection with the body image and its implication for repertoires, I will present two LPs produced in the course of workshops held in a secondary school in Austria. The school was originally founded for the Slovene-speaking minority but with its plurilingual orientation attracts today a heterogeneous school population. The workshops were part of an ongoing research project in which students attending the stream, in which Slovene, German and Italian figure as media of teaching and learning, were asked to evaluate their language learning experiences.

The students were invited to draw an LP and to present it in a subsequent group discussion. In this approach, participants are provided with an A4 sheet and can either use the pre-printed body outline or turn the page and draw one of their own. The body outline currently in useFootnote1 was designed in cooperation with an art therapist who slightly modified earlier versions of the silhouette taking care to respect criteria of mindfulness established in art therapy. The body outline is represented schematically – with no gender or other specifications, and no clothing, but also not ‘naked’ (for example, no toes are visible). The figure does not look too ‘perfect’ to avoid discouraging participants from adding their own elements. Apart from a suggestion of fingers, no details (such as eyes, mouth, or ears) are indicated in order to preserve the possibility of completion. This stylised body outline certainly is somewhat biased towards a construction of an ‘average’ person, which is per definition constituted by exclusions. But the silhouette provides only a framework and can be interpreted in different ways ranging from rather schematised visualisations in the manner of a diagram to creative-artistic design, from a high degree of abstraction to a depiction imagined as a self-portrait. In the hundreds of portraits, I have collected in the past 20 years in pedagogical, therapeutical, and research settings, there are only very few cases in which participants did not make use of the framing offered by the body silhouette.

In LP workshops, participants are asked to think about their linguistic and other communicative resources and experiences; to recall people, places, situations, and activities which they associate with particular ways of communicating; to consider not only their current practices but also those important in the past and those linked to desires for the future; to choose colours that fit the different languages and ways of communication and to place them with regard to the body silhouette. When introducing the research activity particular care should be taken, as simplifications such as ‘use a different colour for every language that you speak’ can result in an undesired reduction of complexity overemphasising the idea of ‘named’ languages as bounded separate entities. Kusters and De Meulder (Citation2019) discuss different ways of introducing the LP activity as employed in previous studies and compare how, in their own work, different prompts, in combination with different research contexts, resulted in slightly different realisations of the portraits. The more openly formulated the invitation to produce an LP, the more wide-ranging and differentiated will be the spectrum of what participants present as semiotic repertoire.

What is seen as common ground in qualitative research concerning all kinds of narratives is equally valid for the LP: we do not understand it as a representation of an individual repertoire ‘as it is’, but as a situational and context-bound co-production framed by the inputs introducing and accompanying the activity. The picture is seen as a moment in a process of dialogic reflection, imagination and presentation are thus addressing an audience. It is produced to be looked at and serves as a point of reference in the subsequent discussion among the participants. The meaning of what is shown is collaboratively negotiated so that the power of interpretation ultimately remains with the authors who decide what they want to show without being urged to impart more than they want.

To illustrate the points made above, I chose the portraits () by two 17-year-old workshop participants – I will call them Peter and Maxim – because of the obvious similarities in their life trajectories and the striking differences in how they evaluated their linguistic resources. Both said that they grew up bilingually, speaking Slovene with one parent and German with the other, and attending bilingual classes since primary school and the trilingual stream in the secondary school from the fifth academic year onwards.

In his drawing and the subsequent group discussion, Peter presents Slovene and German as equivalent resources he relies on. He starts the presentation: ‘So the legs are/ one leg is German and one leg is Slovene. These are the two pillars’.Footnote2 In the drawing, the German regional dialect forms the core of one leg, while the Slovene dialect of his hometown forms the other. The two standard languages German and Slovene are arranged around the core. He assigns one pillar to the mother, the other to the father. Through the symmetrical arrangement, Peter emphasises that he wants to assign equal value to both ‘pillars’. He continues:

In the heart is actually the Slovene dialect and the German dialect/ and also some German. In the head the German language is actually predominant, because in Carinthia pretty much everything is German anyway, the media and so on. Therefore, I think mainly in German, unfortunately.

Maxim in turn positions himself quite differently vis-à-vis this discourse. In his drawing, the colours for German and English clearly dominate and in the presentation, he confirms that he structured the portrait according to the size of colour surfaces and adds ‘one sees that for me German and English are most important because simply I use both languages most in everyday life. Slovene is then ranked third and then come the for me more irrelevant languages’. Later he offers an explanation that refers to experiences in his father’s hometown:

On my father's side, everybody speaks Carinthian Slovene and actually everybody knows it, the Carinthian Slovene. I find Carinthian Slovene quite difficult, the [local] dialect, and I feel quite weird when I then speak the written Slovene, and therefore I feel/ therefore I sometimes simply speak Carinthian [German]. […] It is/ I don’t know/ I think it is simply my fear of speaking so wrong that it is simply only embarrassing.

Both, Peter and Maxim, enumerate other communicative resources at their disposal such as other languages they learn at school. Peter places Italian and English on his shoulders because they were a ‘burden’ but also a ‘backpack’ that could be unpacked when need be. He also mentions another local Slovene dialect, which he has drawn into his raised hand, indicating that he has learnt it to ‘stretch out a hand to my younger cousin’. Maxim adds Japanese referring, as he says, more to ‘Japanese series and animes’ than to the language as such. Beyond named languages Peter specifies that the zigzag line in his arm stands for ‘imitations and parody’ and the white space in his drawing stands for ‘own mixtures’ and ‘own creations’ and ‘for everything to come’.

Peter’s and Maxim’s LPs show a relatively similar set of resources corresponding to the similarities in their language learning trajectories. In what emerges from their presentations of features, however, their body images differ considerably. Peter presents different varieties of German and Slovene (the languages he grew up with) as the solid basis of his being in the world. This basis gives him confidence to build on, for example, by stretching out his hand to find a common ground with his younger cousin. Maxim by contrast finds his basis primarily in German and English, while for Slovene – although he assessed himself as highly competent during the workshop – he reports on feelings of embarrassment and fear when it comes to the variety spoken in his father’s family. This sometimes even pushes him, as he reports, to switch to German even tough Slovene would situationally be more appropriate. Both LPs shed some light on how experiences, ideologies and desires condense into a gestalt captured in the notion of body image, which in turn can help to understand the gap between acquired resources and the possibilities of realising them in situated interactions and bringing them into ‘spatial repertoires’. In other words, doing communication depends not simply on having resources and competencies one can situationally draw on but significantly also on self-conceptions of one’s being in the world.

The language portrait as a window onto the body image

The LP, initially developed as an instrument for language awareness exercises in school (Krumm & Jenkins, Citation2001), first found international resonance through research projects carried out by the Research Group Spracherleben [Lived Experience of Language] at the University of Vienna. In the context of the increasing interest in biographical approaches (for an overview, see Busch, Citation2017b) and in visual or art-based methods (for an overview, see Kalaja & Melo-Pfeifer, Citation2019; Reavey & Johnson, Citation2017), the LP quickly found international recognition as a research tool. Today, it is applied in diverse contexts and fields of interest in language-related research and practice such as in education research and teacher training (Coffey, Citation2015; Prasad, Citation2014), and in therapeutical and clinical settings (Busch & Reddemann, Citation2013). In the context of language use in education, scholars employ the LP to explore regional multilingualism and migration (Busch, Citation2010, Citationin press; Farmer & Naimi, Citation2019). Other topics addressed are family language policy (Obojska, Citation2019; Purkarthofer, Citation2019), indigenous languages (Singer, Citationaccepted), sign language (Kusters & De Meulder, Citation2019), raciolinguistics (Fall & Jones, Citation2018; Mashazi & Oostendorp, Citationaccepted), identity construction and social positioning (Botsis & Bradbury, Citation2018; Bristowe et al., Citation2014; Busch, Citation2012), and language and trauma (Busch, Citation2016; Park Salo & Dufva, Citation2018). Most of these studies follow a qualitative approach but some also combine the LP with corpus linguistic or other quantitative instruments. No matter to which epistemological orientation the studies are indebted, they all in some way embrace the notion of linguistic or semiotic or communicative repertoire – often emphasising the importance of emotions and embodiment.

As a method that is biographic in that it foregrounds the subject perspective, the LP has similar affordances and limitations as other biographic approaches. Addressing the dilemma inherent in biographical approaches, Butler (Citation2005) raises attention towards the fact that the (biographical) subject only emerges when it tells itself to others within the context of normative structures that actually constitute the conditions for the exposure of the subject. She sees this as a source of opacity that creates an undermining effect on a subject’s attempt to provide a narrative of the self. Autobiographical practices are thus understood as performative acts that, paradoxically, enact the biographical ‘I’ while trying to describe it. Autobiographic accounts should then be understood as sites of narrative identity construction and self-representation (De Fina, Citation2015) as much as of self-exploration.

Having these caveats in mind, the LP can be understood as a tool that encourages participants to engage in a metapragmatic reflection on their communicative practices and resources. As it includes an evaluative stance taking that relates particular resources to bodily and emotionally lived experiences, this reflection goes beyond a simple inventory of competences. Taking up the idea developed in this contribution, the LP can be seen as a window onto the body image – an image which usually operates only in the background and remains unnoticed but can play an important role with regard to which personal resources can or cannot be activated in the deployment of a spatial repertoire.

The body silhouette template is suited for tracing the multiple entanglements between body and language discussed above. From the perspective of arts theory, Schulz (Citation2005) views the body as an important reference point in pictorial representations because it acts as an interface between the inner and outer world, between subjects who see pictures and, in turn, objects that are seen as pictures. The metaphorical transformation of the body into a picture facilitates a momentum of self-distancing, which makes it possible to experience oneself as one’s counterpart. This possibility for self-distancing is vested in the duality of being a subject–body and having an object–body (Merleau-Ponty, Citation1962). This duality corresponds to different ways of positioning in relation to the ‘world’: the subject–body as centre of the here-and-now, to which the ‘world’ is related, and the object–body as an observable phenomenon. With its reference to the body, the LP offers the possibility for reflecting on one’s body image both from the ‘inner’ perspective of the experiencing subject–body and from an ‘external’ perspective onto oneself as an object–body.

The body silhouette also helps to scaffold the structuring of a metaphorical space for reflecting on one's repertoire. As Lakoff and Johnson (Citation1999) already flagged in the title of their book, they see metaphors as rooted ‘in the flesh’, i.e. in the bodily experience. Perception systems include basic orientation patterns such as up–down, centre–periphery, containment, and part–whole. These patterns are meaningful because of our bodily being in the world, our manipulation of objects and our movement through space. While rooted in the body, metaphors are understood as culturally and socially defined and context-sensitive. They do not only enable the reflection and communication of complex topics and the anticipation of new situations. Moreover, they allow for the use of different metaphor models, affecting further perception, interpretation of experiences, and possibly also subsequent actions.

In LPs, it is possible to observe various kinds of structuring that correspond to different frames for metaphors. The silhouette suggests a structuring according to parts of the body, which may refer to common, culturally enregistered metaphors such as the head as the place of reason, the belly as the place of emotions, the heart as the location of intimacy, and the hand as the site of social activity. Structuring is also frequently achieved with the help of spatial metaphors – internal/external for familiar and unfamiliar, above/below, for example, for current and more remote, large/small surfaces for important and less important. Working with the LP, only some researchers (e.g. Coffey, Citation2015) explicitly draw on metaphor analysis as practiced in cognitive linguistics, but there is a general agreement (Kusters & De Meulder, Citation2019; Obojska, Citation2019; Park Salo & Dufva, Citation2018; Prasad, Citation2014) that one of the assets of the LP is precisely that the body silhouette offers a frame for thinking with metaphors, or as Botsis and Bradbury (Citation2018, pp. 424–425) put it: ‘The metaphors become powerful signposts in the participants’ narratives, giving us hints about where and how power is negotiated, exerted and subverted’. In their study of linguistic repertoires of signers, Kusters and De Meulder (Citation2019) show how in videotaped group discussions participants presented and bodily enacted their LP and ‘literally mapped their body when signing and gesturing in their narratives, thus performing and becoming their language portrait’ (para [1]).

In sum, working with the LP showed that participants make ample use of the possibility to address feelings linked to particular languages, varieties and semiotic practices but also to address affects metaphorically, as if they were languages, expressed in syntagms like ‘the language of fear’, ‘the language of love’, ‘the language of joy’ (Busch & Reddemann, Citation2013). Kusters and De Meulder (Citation2019) note that when describing the multilingual experience, many of their participants focused on emotions related to particular societal or interactional contexts and to aspirations, desires, and memories.

Merleau-Ponty (Citation1962, p. 229) captures the double quality of language as a creative gesture and as a sedimented set of rules in the terms ‘speaking word’ (parole parlante) and ‘spoken word’ (parole parlée). In the LP, we find language in both dimensions: as a ‘found object’ (with its rules and conventions, its market value and the language ideologies that crystallise around it) and as ‘voice’ or ‘gesture’ intimately tied to subjective and intersubjective experience. This dual character allows participants to shift between their bodily and emotionally lived experience of language (e.g. I love speaking English) and the view on languages and language practices as objects (e.g. English is a useful language). The possibility of switching between the two perspectives ‘in the middle of one sentence’, enables participants to control and regulate how much of themselves and their body image they are ready to reveal. Of course, participants get involved in the activity in different ways: Some see it as a welcome opportunity to reflect on their body image and communication practices, others are more reserved in their drawing and explaining. For adults, the possibility to express themselves with crayons and paper is often unfamiliar, which can lead to a certain reluctance. Nevertheless, participants are often surprised themselves how much such a picture can mean.

Conclusions

At the centre of this contribution is what in the debate on repertoires is often referred to as personal resources, individual baggage, or individual repertoire – a notion that also figures in approaches that locate the repertoire primarily with particular spatial configurations. Repertoires unfold in concrete situated interactions in which participants do not engage as ‘blank pages’, but as human beings of flesh and blood. In connection with semiotic repertoires, as I argued, bodies matter in several respects: on the level of how they are deployed and read in situated interactions, on the level of how they are conceived of in enregistered discourses and not least on the level of bodily stored experiences. I introduced the notion of the body image to take account of the fact that what is brought into the interaction is more than a set of resources and competencies, as it includes an evaluative stance vis-à-vis these resources. The notion of the body image, borrowed from phenomenology, designates an emotionally highly loaded representation of one’s bodily being in the world, formed and transformed in interaction with others. I introduced the LP as an approach that invites participants to reflect on their body image. The two LPs discussed in this contribution illustrate the impact of bodily and emotional experience, of self-perception and perception by others, as well as of desires and projections towards the future. It is the body image that is responsible for whether communicative resources are available and accessible in a certain moment and can be deployed as part of the spatial repertoire.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Free download available under: http://heteroglossia.net/Sprachportraet.123.0.html.

2 All quotes from the presentations during the group discussions translated by myself from German.

References

- Agha, A. (2007). Language and social relations. Cambridge University Press.

- Bakhtin, M. (1981). Discourse in the novel (1934–35). In M. Holquist (Ed.), The dialogic imagination (pp. 259–422). University of Texas Press.

- Blommaert, J. (2007). Sociolinguistic scales. Intercultural Pragmatics, 4(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1515/IP.2007.001

- Blommaert, J., & Backus, A. (2013). Superdiverse repertoires and the individual. Current challenges for educational studies. In I. de Saint-Georges, & J.-J. Weber (Eds.), Multilingualism and multimodality (pp. 11–32). Sense.

- Botsis, H., & Bradbury, J. (2018). Metaphorical sense-making: Visual-narrative language portraits of South African students. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 15(2–3), 412–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2018.1430735

- Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Polity Press.

- Bristowe, A., Oostendorp, M., & Anthonissen, C. (2014). Language and youth identity in a multilingual setting: A multimodal repertoire approach. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 32(2), 229–245. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2014.992644

- Bucholtz, M., & Hall, K. (2016). Embodied sociolinguistics. In N. Coupland (Ed.), Sociolinguistics: Theoretical debates (pp. 173–197). Cambridge University Press.

- Busch, B. (2010). School language profiles: Valorizing linguistic resources in heteroglossic situations in South Africa. Language and Education, 24(4), 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500781003678712

- Busch, B. (2012). The linguistic repertoire revisited. Applied Linguistics, 33(5), 503–523. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/ams056

- Busch, B. (2016). Regaining a place from which to speak and to be heard: In search of a response to the “violence of voicelessness”. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics PLUS, 49(0), 317–330. https://doi.org/10.5842/49-0-675

- Busch, B. (2017a). Expanding the notion of the linguistic repertoire: On the concept of spracherleben – the lived experience of language. Applied Linguistics, 38(3), 340–358.

- Busch, B. (2017b). Biographical approaches to research in multilingual settings: Exploring linguistic repertoires. In M. Martin-Jones, & D. Martin (Eds.), Researching multilingualism: Critical and ethnographic approaches (pp. 46–59). Routledge.

- Busch, B. (2020). Discourse, emotions, and embodiment. In A. De Fina, & A. Georgakopoulou (Eds.), Handbook of discourse studies (pp. 327–349). Cambridge University Press.

- Busch, B. (in press). Children’s perception of their multilingualism. In A. Stavans, & U. Jessner (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of childhood multilingualism. Cambridge University Press.

- Busch, B., & Reddemann, L. (2013). Mehrsprachigkeit, trauma und Resilienz. Zeitschrift für Psychotraumatologie, 11(3), 23–33.

- Butler, J. (1997). Excitable speech. A politics of the performative. Routledge.

- Butler, J. (2005). Giving an account of oneself. Fordham University Press.

- Canagarajah, S. (2018). Translingual practice as spatial repertoires: Expanding the paradigm beyond structuralist orientations. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 31–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx041

- Coffey, S. (2015). Reframing teachers’ language knowledge through metaphor analysis of language portraits. The Modern Language Journal, 99(3), 500–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12235

- De Fina, A. (2015). Narrative and identities. In A. De Fina, & A. Georgakopoulou (Eds.), Handbook of narrative analysis (pp. 351–368). Wiley-Blackwell.

- De Preester, H. (2005). Two phenomenological logics and the mirror neurons theory. In H. De Preester, & V. Knockaert (Eds.), Body image and body schema: Interdisciplinary perspectives on the body (pp. 45–64). John Benjamins.

- Dolto, F. (1984). L'image inconsciente du corps. Éditions du Seuil.

- Duranti, A. (1992). Language and bodies in social space: Samoan ceremonial greetings. American Anthropologist, 94(3), 657–691. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1992.94.3.02a00070

- Fall, M., & Jones, P. (2018). Decolonizing methodologies: Through epistemic rupture. Paper presented at the American Educational research association, April 2018.

- Farmer, D., & Naimi, K. (2019). Penser l’engagement: Une démarche réflexive menée avec de jeunes élèves. Revue Jeunes et Société, 4(1), 24–41. https://doi.org/10.7202/1069167ar

- Foucault, M. (1988). Technologies of the Self. University of Massachusetts Press.

- Fuchs, T. (2011). Body memory and the unconscious. In D. Lohmar, & D. J. Brudzinska (Eds.), Founding psychoanalysis. Phenomenological theory of subjectivity and the psychoanalytical experience (pp. 86–103). Springer.

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday Anchor Books.

- Goffman, E. (1979). Gender advertisements. Harper & Row.

- Goodwin, C. (2000). Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 32(10), 1489–1522. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00096-X

- Gumperz, J. J. (1964). Linguistic and social interaction in two communities. American Anthropologist, 66(6/2), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1964.66.suppl_3.02a00100

- Kalaja, P., & Melo-Pfeifer, S. (eds.). (2019). Visualising multilingual lives: More than words. Multilingual Matters.

- Krumm, H.-J., & Jenkins, E.-M. (2001). Kinder und ihre Sprachen – lebendige Mehrsprachigkeit: Sprachenportraits gesammelt und kommentiert von Hans-Jürgen Krumm. Eviva.

- Küchenhoff, J. (2013). Zwischenleiblichkeit und Körpersprache. In E. Alloa, & M. Fischer (Eds.), Leib und Sprache. Zur Reflexivität verkörperter Ausdrucksformen (pp. 45–55). Velbrück.

- Küchenhoff, J., & Agarwalla, P. (2012). Körperbild und Persönlichkeit. Die klinische Evaluation des Körperlebens mit der Körperbildliste. Springer.

- Kusters, A., & De Meulder, M. (2019). Language portraits: Investigating embodied multilingual and multimodal repertoires. FQS, 20(3), Art. 10. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.3.3239

- Kusters, A., Spotti, M., Swanwick, R., & Tapio, E. (2017). Beyond languages, beyond modalities: Transforming the study of semiotic repertoires. International Journal of Multilingualism, 14(3), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2017.1321651

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to Western thought. Basic Books.

- Mashazi, S., & Oostendorp, M. (accepted). The interplay of linguistic repertoires, bodies and space in an educational context. In J. Purkarthofer & M.-C. Flubacher (Eds.), Speaking subjects – biographical methods in multilingualism research. Multilingual Matters.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of perception. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1968). The visible and the invisble. Northwestern University Press.

- Mondada, L. (2016). Challenges of multimodality: Language and the body in social interaction. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 20(3), 336–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.1_12177

- Obojska, M. A. (2019). Trilingual repertoires, multifaceted experiences: Multilingualism among Poles in Norway. International Multilingual Research Journal, 13(4), 257–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2019.1611337

- Park Salo, N. N., & Dufva, H. (2018). Words and images of multilingualism: A case study of two North Korean refugees. Applied Linguistics Review, 9(2–3), 421–448. doi:10.1515/applirev-2016-1066

- Pennycook, A. (2014). Principled polycentrism and resourceful speakers. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 11(4), 1–19.

- Prasad, G. (2014). Portraits of plurilingualism in a French International school in Toronto: Exploring the role of visual methods to access students’ representations of their linguistically diverse identities. The Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 17(1), 51–77.

- Purkarthofer, J. (2019). Building expectations: Imagining family language policy and heteroglossic social spaces. International Journal of Bilingualism, 23(3), 724–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006916684921

- Reavey, P., & Johnson, K. (2017). Visual approaches: Using and interpreting images. In C. Willig, & W. Stainton Rogers (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of qualitative research in psychology (pp. 354–373). Sage.

- Rymes, B. (2014). Communicating beyond language. Everyday encounters with diversity. Routledge.

- Schilder, P. (1935/2000). The image and appearance of the human body, studies in the constructive energies of the psyche. Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Schulz, M. (2005). Ordnungen der Bilder. Eine Einführung in die Bildwissenschaft. Wilhelm Fink Verlag.

- Schwarz-Friesel, M. (2015). Language and emotion. The cognitive linguistic perspective. In U. Lüdtke (Ed.), Emotion in language: Theory – research – application (pp. 157–173). John Benjamins.

- Singer, R. (accepted). Language portraits as a collaborative tool in research with an indigenous Australian community. In J. Purkarthofer & M.-C. Flubacher (Eds.), Speaking subjects – biographical methods in multilingualism research. Multilingual Matters.

- Spitzmüller, J. (accepted). Ideologies of communication: The social link between actors, signs, and practices. In J. Purkarthofer & M.-C. Flubacher (Eds.), Speaking subjects – biographical methods in multilingualism research. Multilingual Matters.

- Stamenov, M. (2005). Body schema, body image and mirror neutrons. In H. De Preester, & V. Knockaert (Eds.), Body Image and Body Schema: Interdisciplinary perspectives on the body (pp. 21–43). John Benjamins.

- Wetherell, M. (2012). Affect and emotion. A new social science understanding. Sage.