ABSTRACT

This article focuses on the visibility and position of different languages in semiotic space, namely the linguistic landscape provided by textbooks. The aim is to determine to what extent the linguistic landscape of textbooks supports the multilingual emphasis of the Finnish national core curriculum and the multilingualism of Finnish classrooms. The data include 34 textbooks on five of the mandatory subjects and covers the different grades of comprehensive schools in Finland. The presence of different languages was mapped quantitatively by coding all languages that were mentioned or made visible in the textbooks. Further, a qualitative analysis of the most representative parts of the data was carried out. The results of this study show that different contexts and categories are constructed for different languages. Moreover, multilingualism is marginalised and monolingual practices appear as the norm. As a conclusion, this study reveals that the paradigm shift to multilingual approaches and practices in textbooks is under construction, and much is left to be done.

Introduction & context

Textbooks play a central institutional role and are an established part of education. They explicitly aim to mediate knowledge as well as construct conceptions, attitudes and values. Therefore, textbooks have a crucial role in constructing and filtering discourses, and through them the ideologies, of a wider textual world. In this article, the focus is on the representation of different languages and multilingualism in textbooks for basic education in Finland. This study also aims to discover how textbooks reflect the language policies set in the national core curriculum as well as the multilingual reality of Finnish classrooms. The textbooks chosen for analysis are textbooks on five of the mandatory subjects (environmental studies/geography, Finnish language and literature, mathematics, religion/ethics, and social studies) in comprehensive schools in Finland. In this study, textbooks are examined in the framework of the study of linguistic landscapes. Hence, textbooks are viewed as an influential forum that mediates a certain linguistic landscape and thereby conceptions of linguistic diversity.

This research draws on both quantitative and qualitative approaches. First, the quantitative approach is employed when tracing the frequency of named and cited languages in the textbooks. In the research process, not only written texts and exercises but also pictures, graphs and tables are analyzed. The qualitative approach is employed when analyzing in more detail the textual contexts and the pictures where languages or multilingualism are portrayed or defined.

This article offers knowledge for the educational field by making visible the display of languages and multilingualism in textbooks and the language ideologies and policies that they expose. By focusing on languages and multilingualism, this paper sheds light on issues rarely studied in textbooks. The questions examined in this research are relevant both in the local context of Finland as well as globally.

Multilingualism and language policies in Finnish schools

The language policies and practices of schools display the wider political and linguistic situation of the surrounding society. In Finland, language policies are rooted in national bilingualism. Since Finnish independence in 1917 and the establishment of the Language Act in 1922, Finnish and Swedish have shared the status of the official national languages of Finland. These days Swedish is registered as the mother tongue for 5.2 percent and Finnish for 87.3 percent of the population (OSF, Citation2019b). In addition to the two national languages, speakers of three other languages, Sámi, Finnish Romani and sign language, enjoy particular rights in the Constitution. In addition, all ‘other groups’ have a constitutional right to maintain and develop their own languages (The Constitution of Finland, Citation2000, paragraph 17). The category of ‘other groups’ applies, for example, to the long-standing minority group of Russian speakers, who are at the moment the third largest language group in Finland (OSF, Citation2019a). In addition to Russian speakers, Estonian speakers have also been a permanent language group in Finland for centuries and are now the fourth largest language group in Finland (OSF, Citation2019a).

Among the minority languages of Finland, the Sámi languages have a special status as European indigenous languages. Thus, Finland, together with Sweden and Norway, has a particular responsibility to keep these languages vital. Altogether three of the nine different Sámi languages reside in Finland, namely Inari, Skolt and Northern Sámi. The Sámi Language Act (1086/Citation2003) protects the rights of the use of the Sámi languages especially in northern Finland, where they have an official status. In addition to the Sámi languages, the Sign Language Act (359/Citation2015) confirms the status of Finnish and Finnish-Swedish sing languages. On the contrary, for Finnish Romani there exists no special act, although the status of the language is critical. Most of the Finnish Romani speakers speak Finnish or Swedish as their mother tongue and the use of Romani is limited to very specific situations (Hedman, Citation2016).

The national bilingualism of Finland has also been at the centre of school language policies. The tradition has been to protect bilingualism by offering different schools and educational paths for both Finnish and Swedish speakers (e.g. From, Citation2020). Thus, Finnish schools have followed the norm of parallel monolingualism (see Heller, Citation2006; Jonsson, Citation2017). In parallel monolingualism, languages are treated as separate units and schools are seen as monolingual spaces where only the school language should be spoken. However, over the last few decades Finnish schools have become notably multilingual, especially in large urban areas. This has raised new questions concerning language policies and linguistic norms in schools. Meanwhile, in the study of school multilingualism there have been strong proposals for a paradigm shift towards a more holistic view of multilingualism and against the ‘monolingual bias’ (Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2011, p. 2; Gorter & Cenoz, Citation2017a, p. 237–239).

The change in school multilingualism in Finland can be dated from the 1990s when, as a result of migration, new minority languages started to change the linguistic situation in Finland. The turning point was in 2014 when the population speaking other languages than Finnish, Swedish or Sámi as their mother tongue exceeded the population of Swedish speakers. It is currently 7.5 percent of the population (OSF, Citation2019b). This has affected the linguistic diversity of Finnish society in general but particularly that of schools, since the majority of newcomers are from younger age groups. The population of students not speaking Finnish, Swedish or Sámi as their first language has increased steadily during the last ten years and is currently nearly 45,000 (Vipunen, Citation2019). The most common first languages among these students are Russian, Arabic, Estonia, Somali, Kurdish, English, Albanian, Farsi and Chinese (Vipunen, Citation2019). However, the linguistic diversity of the student population differs significantly regionally. The majority of the multilingual students live in southern Finland and in large urban areas; while the majority of the schools are still linguistically rather homogeneous (OSF, Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Citation2019c).

Despite the regional variation, it is clear that the linguistic situation in Finnish schools has changed. This has affected the language policies of schools as well. In the newest national core curriculum for basic education (National Agency for Education, Citation2014), which came into effect in 2016, linguistic diversity is highly emphasised. The core curriculum advocates all languages as valuable resources for learning and obligates teachers to use and support the linguistic resources of their multilingual students (see e.g. Alisaari, Vigren, et al., Citation2019). Thus, the norm of parallel monolingualism (see above) is contested in the newest curriculum. However, the rhetoric of the core curriculum supporting more heterogeneous and multilingual language norms has not yet reached school practices. Instead, monolingual norms and ideologies are still routinely accepted as the norm in schools. In Finnish schools, home language use is controlled by teachers and opportunities for multilingual students to use their whole linguistic repertoire seem limited (e.g. Alisaari, Heikkola, et al., Citation2019; Tarnanen & Palviainen, Citation2018). There are similar results in studies from other countries too (e.g. Agirdag, Citation2010; Cunningham, Citation2019; Panagiotopoulou & Rosen, Citation2018; Pulinx et al., Citation2017).

The textbook as a linguistic landscape

Textbooks are part of the linguistic landscape of schools. Brown (Citation2005) was the first to propose the more specific term schoolscape to study not only the physical but also the social setting in which teaching and learning takes place. Brown (Citation2012, p. 282) further defines schoolscapes as ‘the school-based environment where place and text, both written (graphic) and oral, constitute, reproduce, and transform language ideologies’. Schoolscapes have been analysed in various ways (see e.g. Dressler, Citation2015; Laihonen & Tódor, Citation2017), applying and developing further the methods of the broader field of linguistic landscape research. This study focuses on a specific and essential part of the linguistic landscape of schools, namely textbooks.

Textbooks have attracted the attention of researchers for more than a century and it is a field of study that is still evolving (Fuchs & Henne, Citation2018). This study is parallel to many recent textbook studies that discuss the cultural and ideological politics of textbooks (e.g. Hahl et al., Citation2015; Mills & Mustapha, Citation2015). However, the presence of named languages have not been the focus of previous textbook research and thus this study can offer new insights into the field of textbook studies. In addition, this study is unique in combining textbook studies and linguistic landscape studies.

As a key language item, textbooks are a relevant, albeit a limited, ‘landscape’ for the study of the linguistic landscape of the school. Moreover, textbooks, where they are mandated or frequently used, are highly essential for teaching and for students. Yet despite the existence of resources now available online, textbooks are still the cornerstone of education as the primary textual material available for instruction (e.g. Gay, Citation2018, pp. 144–145; PIRLS, Citation2016). Physical textbooks, despite their limitations, present the result of authoritative selection and the organisation of legitimate and essential knowledge (Apple, Citation1993, p. 49). Therefore, they offer a perspective on the values and representations of the world that are seen as most central and valid.

Research aim

This study takes place in the context of changing and competing views about the use of languages in Finnish schools. This change can be observed in a paradigm shift away from monolingual norms and practices to more multilingual approaches. The latest textbooks, then, should reflect the multilingual paradigm and guide students to use and value their linguistic repertoire, including languages they use at home and during their free time. Within this context, our aim is to determine to what extent the linguistic landscape of textbooks supports the multilingual emphasis of the national core curriculum and the multilingualism of Finnish classrooms. This aim is accomplished by answering two research questions:

What languages are included or disregarded in the textbooks?

How are languages and multilingualism represented in the textbooks?

In this study, we are especially interested in how the minority languages of Finland are displayed in the linguistic landscape of textbooks. As the results of this study show, there are significant differences in the visibility and representation of minority languages in Finnish textbooks. Moreover, the distribution of language items among different subjects is steeply uneven.

Research design

To answer our research questions, we have analysed 34 textbooks from five different subjects in comprehensive school in Finland. The textbook sample chosen for analysis is aimed to cover the disciplinary spectrum of subjects from science to humanities taught in Finnish comprehensive schools. In addition, the sample spans over the different grades of comprehensive school, since the textbooks are from three different grade levels: from the early stage (2nd grade), from the middle phase (6th grade) and from the end (9th grade) of basic education. Thus, the data offer an encompassing, though not exhaustive, view on basic education textbooks.

Data

In January 2019, requests were sent to five important school textbook publishing companies in Finland (Edita, Edukustannus, Otava, Opetushallitus, and SanomaPro). We asked for a copy of each of their textbooks for grades 2, 6 and 9 in environmental studies/geography, Finnish language and literature (FLL), mathematics, religion/ethics, and social studies. We only asked for books that had been updated after the curriculum was revised in 2014. In addition, the data were limited to only textbooks written primarily in Finnish.

All five publishing companies responded positively and sent us the requested books. To make it possible to analyse our sample within our project time, we decided to choose no more than two parallel books from every subject. Thus, if there were more than two books from one subject sent to us, the books for analysis were chosen randomly. With some subjects the problem was the opposite. For the 6th grade there was only one textbook for ethics printed after 2014 and there were a few gaps for minor religions as well. For Orthodox religion there was only one textbook available (for the 2nd grade) and for Islam two books (for the 2nd and 6th grade). For other minor religions mentioned in the core curriculum (the Catholic religion and Judaism), no books that fit the demands of our study were available. In Finland, social studies start from the 6th grade, thus textbooks for the 2nd grade naturally do not exist. Altogether, our research data include 34 textbooks. However, some of the books were combined volumes for several classes. This was the case with Islam (one book for 1st to 2nd grade and one book for 5th to 6th grade) and Ethics (one book for 3rd to 6th grade and two books for 7th to 9th grade). summarises the distribution of the material.

Table 1. Textbook sample distributed according to school subject and grade level.

Method

The textbooks were coded using ATLAS.ti 8-software, suitable for managing qualitative data. We set out to examine the linguistic landscape of textbooks from both the quantitative and the qualitative perspective. To facilitate the quantitative survey, all languages that were mentioned by name or made visible by citing language in the texts, images, tables and graphs were coded. Since co-coding boosts the reliability of the analysis, both article’s authors were involved in coding. However, the first author was mainly responsible for quantitative coding. The reliability of the quantitative analysis was verified with computer-assisted auto-coding.

The codification followed the traditional principles of linguistic landscape studies (see Gorter & Cenoz, Citation2017b; Karam et al., Citation2020; Tang, Citation2020) applied to the context of textbooks. The unit of analysis, then, was not the language item in the sense of a physical item, such as a sign or an establishment in the street as in traditional linguistic landscape studies. Instead, in our study a language ‘item’ refers to one mention of a named language like Somali or a cited language form like hooyo in the textbooks. A cited language form can be a linguistic example or a picture in which a certain language or certain languages are visible. If a picture included different languages or citations, all of them were coded and counted as one unit or item of analysis. This quantitative approach offered us the answer to our first research question about the exposure of different languages in the linguistic landscape of textbooks.

However, it should also be noted that one text example like a piece of news about the Karelian language in one of the FLL textbooks raised the number of mentions significantly and influenced the statistics. Therefore, the results needed to be interpreted carefully in their textual context. Moreover, in our results the units of analysis e.g. ‘language items’ are not fully comparable since one citation may refer to a half-page comic strip, which naturally is much more visible in a textbook than one mention of a language or a citation of one word. However, this is the compromise also made in earlier linguistic landscape studies, where all signs were counted as one unit whether they were big or small.

In the process of coding the textbooks, we also identified the most relevant parts from our data where languages or multilingualism were discussed. We tracked especially parts, where the multilingualism of Finland was confirmed or contested. Both of the researchers made these observations independently and using open coding. We then went through our coding notes, consolidated our understanding, and identified the key parts in our mutual understanding. The analytical process was carried out by applying the methods of qualitative content analysis where the interpretations are made in dynamic interaction with the data and the theory (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008). The aim of the qualitative analysis is to provide a close-up view of how languages and multilingualism were portrayed in the textbooks. Together with the quantitative results they offer the answer to our second research question, how languages and multilingualism are represented in the textbooks.

Languages included or disregarded

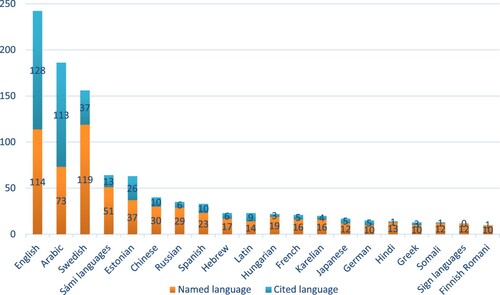

The first research question about the languages that were included or disregarded concerns the number of mentions and citations of a certain language in the textbooks. Graph 1 gives the results. The total number of all the language items in our data was 1247, of which 853 were language mentions and 394 language citations. In the graph, language mentions and language citations are separated by means of different colours. Blue is for ‘named language’ and orange for ‘cited language’. For all other languages, except English and Arabic, there were more mentions than citations. With Arabic, most of the citations were in the Islam religion textbooks (106 out of 113).

All languages, except Finnish, were included in the analysis. However, only languages that were mentioned more than 10 times were included in the table. The bar for Chinese includes mentions of ‘Chinese’ and also mentions of ‘Mandarin’ and ‘Wu Chinese’. Similarly, the bar for the Sámi languages includes mentions of ‘Sámi’ or ‘the Sámi languages’ and mentions of the three different Sámi languages spoken in Finland: Inari, Skolt, and Northern Sámi. In addition, the bar for Sign languages includes mentions of Finnish and Finnish-Swedish sign languages.

Considering the results of our study, it should be noted that languages were mostly visible in the FLL textbooks for the 9th grade (528 mentions out of 1247). In the FLL books for the 6th and 2nd grades the presence of different languages was significantly lower, whereas in the FLL books for the 9th grade there was a special chapter on world languages and the languages of Finland. Thus, most of the mentions came from these specific chapters. In addition to the FLL textbooks, the most mentions of different languages were in geography books for the 9th grade (a total of 84 mentions). In geography books, the number of mentions was almost in line with the biggest languages in the world, since English, Arabic, Hindi, Chinese, Spanish and Portuguese got most mentions.

In the following sections, the results of the quantitative analysis are explicated in more detail. The results have been arranged into three different sections that discuss the visibility of the traditional Finnish minority languages, new minority languages and the status of English in the textbooks.

Traditional minority languages

The visibility of the traditional minority languages of Finland in the textbooks reflects the language policies of Finnish society (see the introduction section). As a national language of Finland, Swedish was mentioned and cited frequently in the textbooks. Hence, it had a strong presence in the linguistic landscape of textbooks. This reflects the firm position of Swedish in Finnish society, where public services and road signs as well as various media from newspapers to a TV channel are available in Swedish and make it a relatively visible language in the Finnish linguistic landscape. Moreover, learning Swedish is compulsory for all pupils in Finnish-medium schools and vice versa, except for the monolingually Swedish Åland Islands (see From & Holm, Citation2019; Ihalainen & Saarinen, Citation2015).

According to Ihalainen and Saarinen (Citation2015, p. 39) the formulations in Finnish legislation show that Swedish has often been framed in a position of ‘the one and only minority language’ in Finland, whereas other minorities are omitted. Thus, Swedish tends to occupy the discursive domain of Finnish multilingualism, while Sámi, Finnish Romani, Sign languages and ‘other languages’ are treated solely in relation to groups of people rather than being treated as languages in their own right (Ihalainen & Saarinen, Citation2015, p. 52). The results of our study reinforce this interpretation, since the Sámi languages as well as Finnish Romani are mainly named in the specific chapters where Sámi or Romani people are discussed.

However, the quantitative visibility of the Sámi languages in the textbooks was somewhat positive. Similar to Sámi, the state of Finnish Romani is also critical and locally crucial. Yet, unlike Sámi, Finnish Romani was rather invisible and cited only once in the textbooks. These observations are in line with the legal status of these languages: there is a special act for Sámi languages, whereas there is no act for Romani (see the introduction section). The Basic Education Act (628/Citation1998) gives Sámi speaking children living in the Sámi home area the right to have the main part of the education in Sámi. However, the problem is that already over 60% of the Sámi are living outside the official Sámi areas, and their linguistic rights are rather weak there (Pasanen, Citation2019). Overall, the position of the Sámi languages is protected and recognised in Finnish society; however, it is not ideal.

Unlike in Ihalainen and Saarinen (Citation2015, cited above), in our textbooks, Swedish is referred to without mentioning its position as a minority language in Finland, whereas the Sámi people and Sámi languages tend to be pictured as a ‘representative minority’. This can be seen to reflect the salient position that Sámi people and Sámi languages have attained in Finnish public discussion. This is justified, as the Sámi languages are indigenous languages and minority languages globally, not only locally. However, when Sámi languages are referenced as ‘default’ minority languages, the diversity of (old and new) minorities in Finland easily remains invisible.

New minority languages

In , the results of the visibility of Arabic may seem surprisingly strong. However, the results would look very different if Islam religion textbooks were excluded from the analysis, since most of the mentions (144 out of 186 mentions) were found in those textbooks. Therefore, Arabic was mostly presented in the context of Islam and was strongly visible only for students who participated in Islam classes. In 2018, around 2% of the pupils in basic education were opting for Islam education (Vipunen Citation2018–Citation2019). The result is similar with Hebrew, which is mentioned mostly in Lutheran religion textbooks and is connected to Judaism. Latin and Greek are mainly cited as ancient languages for example in famous idioms such as ‘Carpe diem!’.

Arabic was mentioned in figures and chapters describing big world languages and the minority languages of Finland. The visibility was similar with Chinese and Russian. Arabic and Chinese both belong to the group of the ‘new local-only’ minority languages of Finland, like Somali, Kurdish, Albanian and Persian. These language groups have grown since the 1990s and they are minority languages only locally in Finland, although they are majority languages in other countries. However, the last four were much less visible in the textbooks than Arabic and Chinese. This was especially the case with Kurdish (4 mentions), Albanian (2 mentions) and Persian (1 mention), which were almost invisible in the textbooks. This could suggest that the global status of a language is more recognised in the textbooks than the local status.

The cognate languages of Finnish (Estonian, Hungarian and small languages like Karelian) were mostly visible only in the FLL textbooks. Estonian is also a neighbouring language of Finland and among the most spoken languages in Finland, like Russian.

In the Finnish curriculum, the students’ mother tongues other than Finnish, Swedish, Sámi or Finnish Romani are referred as ‘home languages’ or ‘own mother tongues’. The providing for home language instruction is not binding for municipalities and thus the practices vary regionally. In 2019, there were 57 different languages learned as ‘home languages’ in Finnish schools. The most learned languages were Russian, Arabic, Somali, and Estonia (National Agency for Education, Citation2019).

In the textbooks, among the most visible other languages (Spanish, French and German) are the most common foreign languages studied in school in Finland (Vipunen Citation2018–Citation2019). In line with this, these languages were often cited and presented as foreign languages that Finnish students may know or study, along with English and Swedish, e.g. in job applications, school reports and timetables (e.g. CitationKärki, p. 78, CitationSärmä, p. 57, CitationGeoidi, p. 20).

Admiration for Japanese pop culture, which has risen globally in the twenty-first century, was also reflected in the textbooks. Japanese was especially visible in pictures of the street scenes of Tokyo (e.g. CitationKärki, p. 21, CitationSärmä, p. 109, CitationGeoidi, p. 6).

Omnipresent English

As Graph 1 shows, English was the most mentioned and cited language in the textbooks. This reflects the status of English, as in Finland English is often called ‘the third domestic language’ because of its strong position in the society (e.g. Leppänen et al., Citation2008). The omnipresence of English in linguistic landscapes is one of the most obvious markers of the process of globalisation, and the expansion of English has been one of the major subjects within linguistic landscape studies (Gorter & Cenoz, Citation2017b).

In the textbooks, English was especially dominant in pictures, where it was portrayed as the language that ‘everyone knows’. Moreover, the reader was regularly advised to make Internet searches with English keywords across the spectrum of subjects (e.g. CitationKipinä, p. 46, CitationTaitaja, p. 123; CitationMaa, p. 93, 133). This creates the impression that English is the language of real and valid knowledge, that is, the language of the Internet. In a similar vein, lists of key concepts at the end of two environmental studies books also include the concepts in English with no reason given (Pisara Citation2, pp. 100–101; Pisara Citation6, pp. 114–121).

While it is true that a knowledge of English is important for increasing opportunities in the global environment, it is also known that English represents a form of inequality, creating a world division between those who know it and those who do not (Shohamy, Citation2006, p. 142). Hence, the unquestioned overrepresentation of English in the textbooks can be seen as problematic, although English is by far the most studied foreign language in Finnish schools (Vipunen Citation2018–Citation2019). However, from the point of view of recently arrived students, those students who already know some English are in many ways in a much better position than those who do not know the language, and this is further legitimised through the textbooks. Moreover, the high visibility of English increases its status even more, while at the same time Finland is worried about the narrowing language resources of its people (Finnish Language Board, Citation2018; Pyykkö, Citation2017). We will discuss the role of English in the textbooks in more detail and with examples in further sections.

Representation of languages and multilingualism

Quantitative analysis of the data gave us a general picture of the linguistic landscape of textbooks. However, to deepen this analysis, we examined in more detail some of the most representative parts of our data. In this section, we present the results of our detailed qualitative analysis, especially focusing on four pictures from the data as well as on observations about the multilingual exercises.

Landscapes of Finnish multilingualism

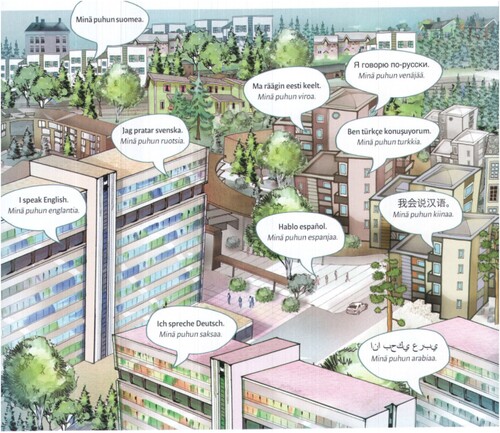

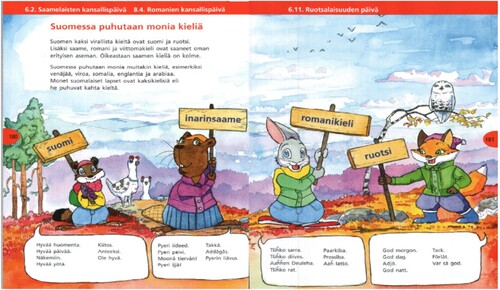

and were chosen as examples, because they offer an interesting pair to compare the representations of the linguistic landscape of Finland. is from the FLL textbook called ‘Kipinä’ (in English ‘Spark’) for the 6th grade, and from the FLL textbook called ‘CitationSeikkailujen lukukirja’ (in English ‘Adventure reading book’) for the 2nd grade.

represents an urban suburb where different languages are spoken. In the speech bubbles the same phrases are given in different languages, and translations in Finnish are provided in italics.

The probable intention of is to portray a Finnish multilingual neighbourhood and the exercises after the figure advise students to investigate their own linguistic surroundings. However, four of the most spoken languages in Finland: Somali, Kurdish, Albanian and Persian are excluded. This is a notable observation, since the same languages are neglected in the data in general, as the quantitative results of our data indicated.

also represents the linguistic landscape of Finland but the landscape of the picture is very different from ’s landscape. Whereas in languages are pictured in an urban environment, in languages belong to nature. The landscape in represents a traditional Finnish national landscape since Finland is known for its forests and nature. Compared to the urban landscape in with its many minority languages, in only ‘traditional’ minority languages (Inari Sámi, Finnish Romani, and Swedish) are included in the national landscape. In the speech bubbles, examples of these languages are presented in the form of greetings and other essential phrases, such as ‘thank you’. However, of other minority languages in Finland, the largest (Russian, Estonian, Somali, English, and Arabic) are mentioned in the text. Thus, different clusters of minority languages are presented within very different visual frames: traditional minorities belong in nature, new minorities in suburbs – only Swedish, in addition to Finnish, belongs to both.

Postcards from Europe

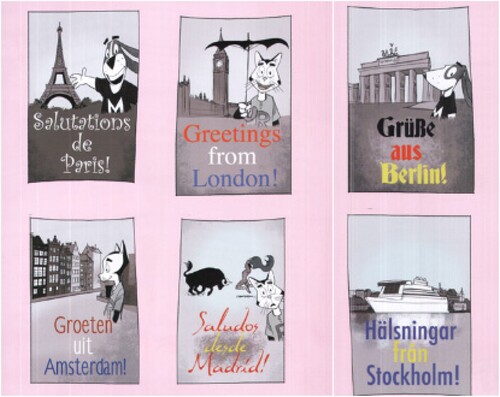

is from the FLL textbook ‘Välkky’ (in English ‘Brainy’ or ‘Sparky’) for the 6th grade. In , European languages are portrayed in stereotypical landscapes – in some cases famous sights like Big Ben or the Eiffel Tower are shown. They are also framed as relevant in relation to the act of tourism: in the pictures, familiar animal characters are sending their greetings from different countries.

The frame of reference can be understood from the Finnish point of view: these are traditional vacation resorts for Finns. In the textbooks, big European languages are connected with European national states, whereas newer Finnish minorities (such as Arabian or Estonian) are represented as being relevant to the Finnish context but less relevant in the geographical context of the Arabian Peninsula or Estonia. This is also in line with the observation about geography: European nation states were specifically represented through the notion of one country – one language, whereas African countries or India were offered as examples of multilingual areas (e.g. CitationGeoidi, p. 18, 63, 66). Naturally, it is justified that multilingualism in geography textbooks is observed as a worldwide phenomenon, and presenting African countries or India as multilingual countries in this context are relevant examples. However, this does reinforce the idea that multilingualism is something that does not belong to Finland and does not resonate with students in the classroom personally.

English as the language of films

is from the FLL textbook ‘Kipinä’ (in English ‘Spark’) for the 6th grade and it represents the visibility of English in our data. As discussed in the earlier sections, English is self-evidently present in the pictures of the textbooks. Interestingly, this was particularly seen in the pictures presenting films, like (also CitationKipinä, p. 180, CitationKärki, p. 67, CitationUniikki, p. 231).

The language choice in the pictures was not explicitly addressed, but it was, however, natural and self-evident. When reaching out for authentic expression, as in , English was presented as a natural choice. One of the FLL textbooks even listed famous movie lines, all of them in English (CitationVälkky, p. 112). As a result of these cases, the textbooks implied that English is the ‘real’ language of films. Language politics can, from one perspective, be seen as battles that are fought by conquering and defending different domains, and this battle is often fought between English as the global lingua franca and smaller national languages and other local languages (see e.g. Ferguson, Citation2007; Hultgren, Citation2012). In textbooks, films seemed to be the first domain that is lost to English. All in all, the use and visibility of English was not bound to any specific context – such as the frame of Finland’s minority languages or the world’s biggest languages – but was overall in the linguistic landscape of the textbooks represented as a language of the everyday.

Multilingual exercises

Exercises where students can use several languages to deal with curricular content are an essential practice when supporting a multilingual landscape of a classroom. With multilingual tasks, textbooks can open up a space for linguistically diverse ‘schoolscapes’. Multilingual ideologies and practices are also emphasised in the newest Finnish core curriculum (see e.g. Alisaari, Vigren, et al., Citation2019). However, as our observations proved, the textbook exercises very rarely offer possibilities for students to engage with their whole language repertoires.

In FLL textbooks and in one geography book, there were a few exercises where students were asked to observe the linguistic surroundings of their neighbourhood or reflect on their linguistic identities from the point of view of multilingualism (e.g. CitationSärmä, p. 90, 98–99; CitationKärki, p. 35, 68; CitationKipinä, p. 37; CitationGeoidi, p. 43). However, exercises where students could use their language repertoires as a medium for learning were missing from the textbooks. Instead, in some textbooks students were only asked to use English as an auxiliary language, for example when making searches from the web (e.g. CitationKipinä, p. 46, CitationTaitaja, p. 123; CitationMaa, p. 93, 133).

In the textbooks there were also a few exercises where students were guided to examine certain languages, e.g. the cognate language of Finland, Estonian, and minority languages of Finland, Finnish Romani and Sámi. However, in these exercises languages were presented as ‘foreign languages’ that no-one in the classroom could know (CitationKärki, p. 21, 23, 27; CitationHyvän elämän peili, p. 93, 97). This gives a clear message about the intended reader of the textbook, that is, a monolingual Finnish speaker.

Fluidity between languages was not encouraged in the textbooks in either the texts or in exercises. One exception was a poem cited in FLL books (CitationVälkky, p. 66, CitationKärki, p. 117) called ‘Oula, ota coca-cola’ (‘Oula, take a coca-cola’) which mixes three languages: Finnish, English and Swedish. This is a small example of a communication that is not defined through monolingual habits, but instead as ‘languaging’ or ‘translanguaging’, which refers to fluidity, switching and meshing between languages (see e.g. Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2011; García, Citation2009).

Although the textbooks do not support multilingual practices, teachers can work as key actors to develop further the exercises the textbooks offer and bring more languages-inclusive practices to classrooms. A transition from a monolingual to multilingual approach in education will be most successful when initiated by teachers at grass-roots level (see e.g. Pulinx et al., Citation2017). However, previous studies do not give encouraging picture about teachers’ attitudes towards multilingual pedagogy. As noted in the introduction, majority of teachers still stick to monolingual policies in education and do not see multilingualism as didactical capital or an asset for learning (e.g. Agirdag, Citation2010; Pulinx et al., Citation2017).

Conclusion & discussion

We can conclude that Finnish, English and Swedish are the dominant languages in the linguistic landscape of the textbooks. The results reflect the status of these languages in Finnish society, since Swedish is the national language and English ‘the third domestic language’ used extensively in many fields. The results also reflect the intensity of language policies for minority languages in Finland. The Sámi languages as indigenous languages have a clear presence, whereas other traditional minority languages are hardly visible. New local-only minority languages are visible only if they are significant globally. If not, they are rather invisible in the textbooks.

In the linguistic landscape of textbooks, different contexts are constructed for different languages. In textbooks, English has broken out of any narrow frame of reference, whereas minorities are confined to their own chapters and big European languages are represented within the frame of tourism. This framing is established powerfully with visual images. These diverse ways of representation offer very different kinds of positions for identification for readers with different linguistic identities. As Daly (Citation2018) has noted in their study of the linguistic landscape of multilingual picturebooks, this can have negative implications for the ethnolinguistic vitality of minority language groups.

An overwhelming share of actual text in other languages than in Finnish consists of greetings or mentions in the tables and graphs. These are a relatively limited sample of a language and can, therefore, even be seen as tokenism (e.g. Cunningham, Citation2019, p. 296). Instead, to value a language more completely, it should be a part of learning, and the use of different languages should be encouraged in classrooms through textbooks and other means.

In terms of ethnolinguistic vitality, languages vary from, globally speaking, non-endangered languages such as Arabic to seriously endangered languages such as the Sámi languages. However, we agree with Gorter et al. (Citation2012, p. 7) who argue that all languages are endangered languages in one way or another, at least in their specific minority settings. For example, when migrating to a new country the languages one has acquired before are not often seen as relevant in the new context. In the context of this study, that is, in Finland and in Finnish schools, local-only minority languages are threatened when a student speaking one or more of these languages faces the marginalisation and underestimation of their language skills and in the worst case scenario ends up losing competence in them. The results of this study reveal that some languages are notably less presented in the textbooks than others, and this can indicate the esteem given to these languages in Finnish society in general. Therefore, as Agirdag (Citation2010) points out in their study, some multilingualism is highly valued, as European languages such as English and French are seen enriching resources for students; whereas the non-European immigrant-languages are seen less valuable. This can even lead to institutional racism (see Gilborn, Citation2020) if linguistic minority students face the pressure to abandon their ‘less valuable’ languages in school system.

A trajectory can be seen between the reality of classrooms, education policy texts and textbooks, where multilingual reality is already reflected in the core curriculum but not yet entirely in textbooks. In the design of new textbooks, the paradigm shift from parallel monolingualism to multilingualism can be pushed further.

Acknowledgements:

This work is part of a broader research project called KUPERA – Cultural, Word View and Language Awareness in Basic Education at the University of Helsinki 2019–2021.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Primary sources (textbooks)

- Geoidi = Cantell, H., Jutila, H., Keskitalo, R., Moilanen, J., Petrelius, M., & Viipuri, M. (2019). Geoidi: Ihmiset ja kulttuuri. Helsinki: Sanoma Pro.

- Hyvän elämän peili = Calonius, L., Lehtinen, E., Lindfors, J., & Tuominen, R. (2019). Hyvän elämän peili. Helsinki: Opetushallitus.

- Kärki = Karvonen, K., Lottonen, S., & Ruuska, H. (2017). Äidinkieli ja kirjallisuus Kärki 9. Helsinki: Sanoma Pro.

- Kipinä = Arvaja, S., Kangasniemi, E., Konttinen, M., Lairio, S., Löyttyniemi, A., Pesonen-Kokko, S., & Teräs, M. (2016). Kipinä 6. Helsinki: Otava.

- Maa = Fabritius, H., Jortikka, S., Mäkinen, L.-L., & Nikkanen, T. (2017). Maa: Kotina maailma. Helsinki: Otava.

- Pisara 2 = Asplund, J., Cantell, H., Suojanen-Saari, T., & Viitala, M. (2018). Pisara 2. Ympäristöoppi. Helsinki: Sanoma Pro.

- Pisara 6 = Cantell, H., Jutila, H., Laiho, H., Lavonen, J., Pekkala, E., & Saari, H. (2018). Pisara 6. Ympäristöoppi. Helsinki: Sanoma Pro.

- Särmä = Aarnio, R., Kaseva, T., Kuohukoski, S., Matinlassi, E., & Tylli, A. (2015). Särmä 9 Yläkoulun äidinkieli ja kirjallisuus. Helsinki: Otava.

- Seikkailujen lukukirja = Backam, A., Kolu, S., Lassila, K., Solastie, K., & Lumme, J. (2014). Seikkailujen lukukirja. Helsinki: Otava.

- Taitaja = Hieta, P., Johansson, M., Kokkonen, O., Piekkola-Fabrin, H., & Virolainen, M. (2018). Yhteiskuntaopin taitaja 9. Helsinki: Sanoma Pro.

- Uniikki = Käpylehto, K., Manner, M., Silfverberg, R., & Sakaranaho, T. (2019). Uniikki. 7–9 Elämänkatsomustieto. Helsinki: Edita.

- Välkky = Haviala, A., Kalm, M., Katajamäki, M., Siter, M., & Vepsäläinen, M. (2018). Välkky 6 Äidinkieli ja kirjallisuus. Helsinki: Sanoma Pro.

- Secondary sources

- Agirdag, O. (2010). Exploring bilingualism in a monolingual school system: Insights from Turkish and native students from Belgian schools. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 31(3), 307–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425691003700540

- Alisaari, J., Heikkola, L., Commins, N., & Acquah, E. (2019). Monolingual ideologies confronting multilingual realities: Finnish teachers’ beliefs about linguistic diversity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 80, 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.01.003

- Alisaari, J., Vigren, H., & Mäkelä, M.-L. (2019). Multilingualism as a resource: Policy changes in Finnish education. In S. Hammer, K. Viesca, & N. Commins (Eds.), Teaching content and language in the multilingual classroom: International research on policy, perspectives, preparation and practice (pp. 29–49). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429459443

- Apple, M. (1993). Official knowledge: Democratic education in a conservative age. Routledge.

- Basic Education Act. (1998). Perusopetuslaki 628/1998. https://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/1998/en19980628.pdf

- Brown, K. D. (2005). Estonian schoolscapes and the marginalization of regional identity in education. European Education, 37(3), 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/10564934.2005.11042390

- Brown, K. D. (2012). The linguistic landscape of educational spaces: Language revitalization and schools in southeastern Estonia. In D. Gorter, G. Hogan-Brun, H. Marten, & L. Van Mensel (Eds.), Minority languages in the linguistic landscape (pp. 281–298). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2011). A holistic approach in multilingual education: Introduction [Special issue: Toward a multilingual approach in the study of multilingualism in school contexts]. The Modern Language Journal, 95(3), 339–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01204.x

- The Constitution of Finland. (2000). Suomen perustuslaki 731/1999. https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/kaannokset/1999/en19990731.pdf

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage.

- Cunningham, C. (2019). The inappropriateness of language: Discourses of power and control over languages beyond English in primary schools. Language and Education, 33(4), 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2018.1545787

- Daly, N. (2018). The linguistic landscape of English–Spanish dual language picture books. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 39(6), 556–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2017.1410163

- Dressler, R. (2015). Sign geist: Promoting bilingualism through the linguistic landscape of school signage. International Journal of Multilingualism, 12(1), 128–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2014.912282

- Ferguson, G. (2007). The global spread of English, scientific communication and ESP: Questions of equity, access and domain loss. Ibérica, 13, 7–38. http://www.aelfe.org/documents/02%20ferguson.pdf

- Finnish Language Board. (2018). Suomi tarvitsee pikaisesti kansallisen kielipoliittisen ohjelman. [Finland rapidly needs a national agenda in language politics]. Statement of the Finnish Language Board. https://www.kotus.fi/ohjeet/suomen_kielen_lautakunnan_suosituksia/kannanotot/suomi_tarvitsee_pikaisesti_kansallisen_kielipoliittisen_ohjelman

- From, T. (2020). We are two languages here. The operation of language policies through spatial ideologies and practices in a co-located and a bilingual school. Multilingua, 39(6), 663–684. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2019-0008

- From, T., & Holm, G. (2019). Language crashes and shifting orientations: The construction and negotiation of linguistic value in bilingual school spaces in Finland and Sweden. Language and Education, 33(3), 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2018.1514045

- Fuchs, E., & Henne, K. (2018). History of textbook research. In E. Fuchs, & A. Bock (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of textbook studies (pp. 25–56). Palgrave Macmillan.

- García, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Teachers College.

- Gillborn, D. (2005). Education policy as an act of white supremacy: whiteness, critical race theory and education reform. Journal of Education Policy, 20(4), 485–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930500132346

- Gorter, D., & Cenoz, J. (2017a). Language education policy and multilingual assessment. Language and Education, 31(3), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2016.1261892

- Gorter, D., & Cenoz, J. (2017b). Linguistic landscape and multilingualism. In J. Cenoz, D. Gorter, & S. May (Eds.), Language awareness and multilingualism. Encyclopedia of language and education (pp. 233–245). Springer.

- Gorter, D., Hogan-Brun, G., Marten, H., & van Mensel, L. (2012). Minority languages in the linguistic landscape. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hahl, K., Niemi, P.-M., Johnson Longfor, R., & Dervin, F. (eds.). (2015). Diversities and interculturality in textbooks: Finland as an example. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Hedman, H. (2016). Suomen romanikielen asemaan ja säilymiseen vaikuttavia tekijöitä [Factors affecting the status and preservation of the Finnish Romani language]. In M. Huhtanen, & M. Puukko (Eds.), Romanikielen asema, opetus ja osaaminen: Romanikielen oppimistulokset perusopetuksen 7.-9. Vuosiluokilla 2015 (pp. 21–38). Kansallinen koulutuksen arviointikeskus (KARVI). https://karvi.fi/app/uploads/2016/03/KARVI_0416.pdf

- Heller, M. (2006). Linguistic minorities and modernity. Continuum.

- Hultgren, K. (2012). Lexical borrowing from English into Danish in the sciences: An empirical investigation of domain loss. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 23(2), 166–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2012.00324.x

- Ihalainen, P., & Saarinen, T. (2015). Constructing ‘language’ in language policy discourse: Finnish and Swedish legislative processes in the 2000s. In M. Halonen, P. Ihalainen, & T. Saarinen (Eds.), Language policies in Finland and Sweden: Interdisciplinary and multi-sited comparisons (pp. 29–56). Multilingual Matters.

- Jonsson, C. (2017). Translanguaging and ideology: Moving away from a monolingual norm. In B. Paulsrud, J. Rosén, B. Straszer, & Å Wedin (Eds.), New perspectives on translanguaging and education (pp. 20–37). Multilingual Matters.

- Karam, F. J., Warren, A., Kibler, A. K., & Shweiry, Z. (2020). Beiruti linguistic landscape: An analysis of private store fronts. International Journal of Multilingualism, 17(2), 196–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2018.1529178

- Laihonen, P., & Tódor, E. M. (2017). The changing schoolscape in a Szekler village in Romania: Signs of diversity in rehungarization. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 20(3), 362–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2015.1051943

- Leppänen, S., Nikula, T., & Kääntä, L. (Eds.). (2008). Kolmas kotimainen: Lähikuvia englannin käytöstä suomessa. [The third domestic language: Close-ups on the use of English in Finland]. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Tietolipas 224.

- Mills, S., & Mustapha, A. (Eds.). (2015). Gender representations in learning materials: International perspectives. Routledge.

- National Agency for Education. (2014). Perusopetuksen opetussuunnitelman perusteet [Finnish National Curriculum for Basic Education]. Määräykset ja ohjeet 2014:96. https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/perusopetuksen_opetussuunnitelman_perusteet_2014.pdf

- National Agency for Education. (2019). Maahanmuuttajien koulutuksen tilasto [Statistics of the immigrants’ education]. https://www.oph.fi/fi/tilastot/maahanmuuttajien-koulutuksen-tilastot

- Official Statistics of Finland (OSF). (2019a). Statistics Finland, Biggest numbers of foreign-language speakers 2019. https://www.stat.fi/tup/maahanmuutto/maahanmuuttajat-vaestossa/vieraskieliset_en.html

- Official Statistics of Finland (OSF). (2019b). Population structure [e-publication]. ISSN=1797-5395. 2019, Appendix table 2. Population according to language 1980–2019. Statistics Finland. http://www.stat.fi/til/vaerak/2019/vaerak_2019_2020-03-24_tau_002_en.html

- Official Statistics of Finland (OSF). (2019c). Foreign language students in basic education in 2019 (The statistics requested for the survey).

- Panagiotopoulou, J., & Rosen, L. (2018). Denied inclusion of migration-related multilingualism: An ethnographic approach to a preparatory class for newly arrived children in Germany. Language and Education, 32(5), 394–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2018.1489829

- Pasanen, A. (2019). Becoming a new speaker of a Saami language through intensive adult education. In A. Sherris, & S. D. Penfield (Eds.), Rejecting the marginalized status of minority languages: Educational projects pushing back against language endangerment (pp. 49–69). Multilingual Matters.

- PIRLS. (2016). Progress in International Reading Literacy Study. https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/pirls-landing.html

- Pulinx, R., Van Avermaet, P., & Agirdag, O. (2017). Silencing linguistic diversity: The extent, the determinants and consequences of the monolingual beliefs of Flemish teachers. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 20(5), 542–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2015.1102860

- Pyykkö, R. (2017). Monikielisyys vahvuudeksi. Selvitys Suomen kielivarannon tilasta ja tasosta [Multilingualism into a strength: A report on the status and levels of language competences in Finland]. OKM.

- Shohamy, E. (2006). Language policy: Hidden agendas and new approaches. Routledge.

- Sign Language Act. (2015). Viittomakielilaki 359/2015. https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/kaannokset/2015/en20150359.pdf

- Sámi Language Act. (2003). Saamen kielilaki 1086/2003. Retrieved from: https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/kaannokset/2003/en20031086.pdf

- Tang, H. K. (2020). Linguistic landscaping in Singapore: Multilingualism or the dominance of English and its dual identity in the local linguistic ecology? International Journal of Multilingualism, 17(2), 152–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2018.1467422

- Tarnanen, M., & Palviainen, Å. (2018). Finnish teachers as policy agents in a changing society. Language and Education, 32(5), 428–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2018.1490747

- Vipunen. Opetushallinnon tilastopalvelu. (2018–2019). Perusopetuksen kieli- ja muut ainevalinnat [Languages and other subject choices in basic education]. https://vipunen.fi/fi-fi/perus/Sivut/Kieli–ja-muut-ainevalinnat.aspx.

- Vipunen. Opetushallinnon tilastopalvelu. (2019). Väestö äidinkielen ja kansalaisuuden mukaan [Population by language and nationality]. Opetushallinnon ja Tilastokeskuksen tietopalvelusopimuksen aineisto. https://vipunen.fi/fi-fi/_layouts/15/xlviewer.aspx?id=/fi-fi/Raportit/V%C3%A4est%C3%B6rakenne%20%C3%A4idinkielen%20mukaan.xlsb