ABSTRACT

The study investigates the reflections on tempo-aspectual morphology in Italian expressed by undergraduate multilingual learners with previous knowledge of Swedish and a Romance language (N = 22). The reflections of the participants, who were divided into four groups depending on a combination of proficiency in their background Romance language and in Italian, were analysed using a qualitative content analysis. From the analysis categories and subcategories emerged, and their occurrences served to display group tendencies. Four categories (explicit rules, intuition, other languages and uncertainty/unknown), and seven subcategories were found and their occurrence was differently distributed across groups. Further, the reflections of the learners became more sophisticated as proficiency in Italian increased. In fact, the reflections progressively incorporated different layers of information connected to explicit knowledge about tenses: temporal, aspectual and, finally, lexical, that is, the inherent semantics of the predicates. Finally, while the reflections of low-proficiency learners referred to different L2s (e.g. English and French), high-proficiency learners made comparisons with Swedish more consistently, regardless of their proficiency level in the Romance language. These results are discussed in the light of research on second/additional language learning of aspectual distinctions in Romance languages.

1. Introduction

The L2 acquisition of past tense verb morphology in Romance languages is a complex process because Romance past tenses simultaneously express temporal and aspectual information. That is, a Romance past tense form such as ‘mangiava’ in Italian (he/she ate) provides a past temporal frame and, additionally, an aspectual perspective, telling us that the situation is viewed from the inside (Giacalone Ramat, Citation2002). Research on the L2 acquisition of past verb morphology in Romance languages, also known as tempo-aspectual verb morphology, has traditionally focused on influences from the L1 alone, although learners oftentimes had knowledge of other non-native languages and were therefore not learning a true second language, but an additional language (e.g. Kihlstedt, Citation1998).

However, with the recent upsurge of third language acquisition studies (e.g. Angelovska & Hahn, Citation2017; Bardel & Sánchez, Citation2020; Cabrelli Amaro et al., Citation2012; Puig-Mayenco et al., Citation2020) and the ‘multilingual turn’ in language education (Conteh & Meier, Citation2014; May, Citation2013), the scope of second language acquisition (SLA) research has progressively incorporated the influence from all previously known languages and underscored features peculiar of multilingual learning. By having previous experience of learning a foreign language, multilingual speakers usually possess enhanced metalinguistic knowledge, namely their ability to ‘reflect upon and manipulate linguistic features, rules or data’ (Falk et al., Citation2015, p. 3). In order to gain insights into how multilinguals make sense of the grammar of a new language, it is fundamental to use methodologies tapping into their metalinguistic knowledge, such as introspection.

However, there is a scarcity of studies examining the learners’ introspective reflections about how they make sense of tempo-aspectual verb morphology (Collins, Citation2005; Izquierdo & Collins, Citation2008; Liskin-Gasparro, Citation2000). Still fewer studies have looked at how learners consciously exploit their previously learned languages (Bardel, Citation2005; Comajoan, Citation2019), although a few recent studies have provided evidence that both the L1 and the L2s may contribute to transfer of aspectual contrasts in an additional language (Diaubalick et al., Citation2020; Eibensteiner, Citation2019; Vallerossa, Citation2021; Vallerossa et al., Citation2021). Finally, it is important to investigate how the way multilingual learners make sense of verb morphology is mediated by L2 proficiency and by target language proficiency.

The present study aims to fill important research gaps, by exploring how multilingual learners (N = 22) with varying proficiency levels in a Romance language, and in Italian as an additional language, make sense of tempo-aspectual morphology. The learners were enrolled in undergraduate courses of Italian in Sweden. They completed two proficiency tests, one in Italian and one in their Romance language, and an interpretation test of aspectual knowledge in Italian, during which they provided written reflections motivating their choices of inflectional morphology.

2. Target structure

The structure investigated here is grammatical aspect, which conveys the perspective through which a situation is presented. Two types of aspect are distinguished in the literature (Comrie, Citation1976). The perfective aspect refers to a concluded situation viewed from the outside and the imperfective aspect refers to an uncompleted situation viewed from the inside. Imperfective aspect can convey two major meanings; habitual aspect refers to a recurrent situation whereas progressive aspect defines an ongoing situation. These meanings (perfective, imperfective progressive, imperfective habitual) are not expressed consistently across languages. In below, the codification of aspect (perfective, imperfective progressive, imperfective habitual) in Italian and Swedish is presented, with a specific focus on the four Italian verb forms elicited in the study.

Swedish belongs to the group of Germanic languages codifying aspect lexically. That is, besides tenses, there are lexical structures, such as adverbials and different types of constructions, conveying aspect. Swedish has an ambiguous past tense, the preteritum, expressing perfective and imperfective aspect, and different constructions for habitual and progressive aspect. Habitual aspect is expressed by the modal bruka (‘to use to’) followed by an infinitive and progressive aspect by the periphrasis with hålla på att (‘to be in the process of –ing’).

Table 1. Realisation of aspect (perfective, imperfective progressive, imperfective habitual) in Italian and Swedish. PP: passato prossimo; PR: passato remoto; IMPF: imperfetto; PROG: progressive periphrasis stare + gerund; PRET: preteritum; HÅLLA: hålla på att; BRUKA: bruka.

Romance languages, including Italian, codify aspect morphologically, meaning that inflectional morphology also encodes aspectual information. Perfective tenses convey perfective aspect while imperfective tenses convey imperfective aspect, progressive and habitual (passato prossimo/imperfetto in Italian, passé composé/imparfait in French, pretérito indefinido/imperfecto in Spanish). There are generally two perfective verb forms in Romance and their use varies (Squartini & Bertinetto, Citation2000): in Italian, the analytic passato prossimo is the most common, while a less common synthetic tense, passato remoto, conveys situations located in a remote past. It must be mentioned, however, that the use of passato remoto varies diatopically, as it is more frequent in Southern varieties than in Northern varieties, and diastratically, as it is typical of formal registers (Squartini & Bertinetto, Citation2000). Italian also has a periphrastic construction expressing progressive aspect (stare + gerund).

3. Literature review

3.1. Learning aspect in a Romance second or additional language

Research on the L2 acquisition of aspect in Romance languages has shown that the intrinsic meanings entailed by verb predicates, also referred to as lexical aspect, are fundamental in orienting the learners’ selection of inflectional morphology. This line of thought is connected to the ‘Lexical Aspect Hypothesis’ (LAH), which postulates that learners of languages marking aspect morphologically, at least initially, choose past inflectional morphology based on aspectual distinctions and according to the predicates’ lexical aspect (Andersen, Citation1993; Shirai & Andersen, Citation1995). Learners would acquire first perfective morphology and associate it with telic predicates, those verbs entailing an intrinsic culmination, as ‘to finish’. Imperfective morphology is acquired subsequently and combined with atelic predicates, those lacking an endpoint as ‘to play’. The learners’ reliance on these types of associations between grammatical and lexical aspect, defined as prototypical, is determined by input frequency, saliency, and a semantic symmetry between lexical and grammatical aspect (Andersen, Citation1993). Moreover, according to the One-to-One principle, learners tend to be conservative in their tense selection, as they assume that ‘each grammatical morpheme […] has one and only one meaning, function, and distribution’ (Andersen, Citation1993, p. 329).

The LAH has, however, undergone a few changes. It was noted that learners initially rely on a default tense form expressing past temporality, and not aspect, also referred to as the ‘Default Past Tense Hypothesis’ (henceforth, DPTH, Wiberg, Citation1996) while prototypical associations emerge among advanced learners (Salaberry, Citation2000). In addition, the DPTH accounts for L1 transfer. Indeed, the fact that the first distinction made by English (Salaberry, Citation2000, Citation2008) and Swedish (Wiberg, Citation1996) speakers learning a Romance language is temporal and not aspectual could be due to the non-grammatical realisation of aspect in the learners’ L1.

With the recently increased interest in multilingual learning, it has been suggested that the entire linguistic repertoire is activated when learning a new language and may potentially contribute to transfer (Angelovska & Hahn, Citation2017; Hufeisen, Citation2018). In particular, studies focusing on the acquisition of morphosyntax from a multilingual perspective have identified a few factors that are fundamental for the selection of a background language as a privileged source for transfer. For example, the relationship of (perceived) linguistic proximity understood either on the whole (Rothman, Citation2011, Citation2015) or in terms of specific linguistic structures (Westergaard et al., Citation2017) has been adduced as crucial for the activation of background languages. Another relevant component in multilingual transfer is linguistic status, intending whether the potentially influencing language is a native or a non-native language. In fact, several studies attested preferential transfer from a L2 – rather than from the L1 – into an additional language. This tendency is explained by the fact that the L2s and the additional language are characterised by similar processes of language appropriation (Bardel & Falk, Citation2007; Citation2012; Falk et al., Citation2015; Williams & Hammarberg, Citation1998). Furthermore, L2 proficiency and target language proficiency are responsible for different transfer outcomes. For example, low proficiency level in the target language can determine a more extensive influence from prior L2s as a compensatory strategy (Williams & Hammarberg, Citation1998). Also, a certain proficiency in a L2 is likely to be necessitated if transfer to an additional language is to take place, although evidence for the opposite outcome has also been found (e.g. Lindqvist & Bardel, Citation2014).

This interest in multilingual grammar learning has also affected the research field with regard to grammatical aspect, with recent studies attesting both L1 and L2 influences in the acquisition of specific aspectual meanings (Diaubalick et al., Citation2020; Eibensteiner, Citation2019; Salaberry, Citation2020; Vallerossa, Citation2021; Vallerossa et al., Citation2021; Vallerossa & Bardel, Citationwork in progress). Four major conclusions can be drawn based on studies on learning grammatical aspect in a Romance language as L2/Ln: first, transfer from previously known languages is strongest during the initial stages of acquisition and it eventually flattens out as target language proficiency increases (McManus, Citation2015). Second, there is transfer of verb forms that are similar in previously known languages, either the L1 or the L2s, and in the target language (Diaubalick et al., Citation2020; Eibensteiner, Citation2019; Foote, Citation2009; Salaberry, Citation2005). Third, there is transfer of aspectual meanings, as long as previously known languages and the target language have grammatical means expressing aspect (for L1 influence: Kihlstedt, Citation1998; Labeau, Citation2005; for L2 influence: Eibensteiner, Citation2019; Vallerossa et al., Citation2021). Finally, studies conducted on multilinguals found that high proficiency in a non-native language was essential to facilitate its transferability into a subsequent language (Diaubalick et al., Citation2020; Eibensteiner, Citation2019; Vallerossa et al., Citation2021).

To sum up, background languages (L1/L2) and semantic principles have been idenified, among other factors (see Bardovi-Harlig & Comajoan-Colomé, Citation2020 for a review), as important for the learners’ selection of tempo-aspectual morphology in Romance languages. In the following section, introspective studies on the acquisition of verb morphology are reported.

3.2. Introspective studies on the acquisition of verb morphology

There are four cross-sectional studies on learning grammatical aspect (Collins, Citation2005; Comajoan, Citation2019; Izquierdo & Collins, Citation2008; Liskin-Gasparro, Citation2000) and one longitudinal case study (Bardel, Citation2005) on learning verb morphology adopting introspective methodologies.Footnote1 The introspective material consisted of retrospective interviews about data of various type, for instance retelling story tasks (Bardel, Citation2005; Liskin-Gasparro, Citation2000), interviews (Bardel, Citation2005), multiple choice judgement tasks (Collins, Citation2005; Comajoan, Citation2019) and a cloze-test (Izquierdo & Collins, Citation2008). Bardel (Citation2005) had additional retrospective diary data. The studies by Collins (Citation2005), Izquierdo and Collins (Citation2008) and Liskin-Gasparro (Citation2000) were conducted from a traditional L2 perspective, while Bardel (Citation2005) and Comajoan (Citation2019) explicitly investigated the influence from all of the background languages. Three studies had a Romance language as target language, and English (Liskin-Gasparro, Citation2000), Swedish (Bardel, Citation2005), or several different L1s (Comajoan, Citation2019). Collins (Citation2005) analysed L1 speakers of Chinese and Japanese learning English while Izquierdo and Collins (Citation2008) contrasted two groups of learners of L2 French, one with Spanish as L1 and one with English as L1.

Three common categories were found in these studies. In the studies dealing with the learning of grammatical aspect, learners relied on congruence between lexical and grammatical aspect, especially with states (Collins, Citation2005; Liskin-Gasparro, Citation2000) and punctual verbs (Izquierdo & Collins, Citation2008). Further, learners fell back on rules they came up with or pedagogical rules. Input frequency was an often-mentioned category by the learners, especially for less-frequent combinations, which sounded incorrect (Collins, Citation2005, p. 214; Liskin-Gasparro, Citation2000, p. 836).

Izquierdo and Collins (Citation2008) found three more categories: form-function indicating the learners’ awareness of the aspectual meanings connected to perfective and imperfective morphology. The category ‘discourse’ referred to ‘elements from other sentences […] to supply tense-aspect marking (p. 362)’. Finally, the L1 was an impeding factor for L1 English speakers while it was a facilitating source of transfer for L1 Spanish speakers.

Furthermore, Comajoan (Citation2019) found nine strategies among 18 multilingual beginner learners of Catalan. Some of the strategies corresponded to those found in previous studies, as the category ‘aspect’ which roughly corresponded to the ‘form-function’ category in Izquierdo and Collins (Citation2008). The strategies were classified into four general strategies (i.e. translation, contrast, classroom instruction, intuition) and five tense-aspect specific strategies (i.e. aspect, tense, adverbial, discourse grounding, lexical aspect). In Comajoan's study, different strategies, oftentimes occurring in clusters and not in isolation, were connected to specific tenses: for example, the choice of preterite was generally sustained by an aspect strategy, namely the fact that the situation described was concluded, while translation strategies motivated the choice of imperfect although the translation was not always felicitous. Further, learners selected different source languages to make sense of different tenses and aspectual meanings: English was helpful for the habitual meaning of imperfect and Spanish for the perfect.

The study by Bardel (Citation2005) expanded on the positive role of previous non-native languages: the single learner rapidly acquired the Italian verbal system, due to a strategic deployment of her advanced knowledge of French. In fact, she had a high degree of cross-linguistic awareness, namely the ‘learners’ awareness of the links between their language systems expressed tacitly and explicitly during language production and use’ (Jessner, Citation2006, p. 116), which helped her develop sophisticated strategies with respect to her relatively low proficiency level.

4. The study

Introspective studies on the acquisition of verb morphology have been cross-sectional studies focusing on learners at a specific proficiency level (Collins, Citation2005; Comajoan, Citation2019; Izquierdo & Collins, Citation2008; Liskin-Gasparro, Citation2000) or longitudinal case studies (Bardel, Citation2005). While case studies provide information about learners’ interlanguage over time, they do not lend themselves well to the results’ generalizability. Cross-sectional studies offer a snapshot of learners’ reflections at a certain stage but are less informative about developmental trajectories.

The present study investigates whether and, if that is the case, how the way multilingual learners make sense of verb morphology develops depending on L2 proficiency and target language proficiency. In order to do this, we explore how multilingual learners with varying proficiency levels in a Romance language, and in Italian as an additional language, make sense of aspectual morphology.

The following research questions are addressed:

RQ1: How do multilingual learners of Italian as an additional language make sense of Italian past tense forms?

RQ2: How do their reflections on Italian past tense forms vary depending on proficiency in a Romance language and in Italian?

5. Method

5.1. Participants

The learner sample consists of undergraduate students of Italian as additional language (N = 22) with knowledge of Swedish and a Romance language. Overall, there were 14 female and 8 male participants. Their age ranged from 20 to 76 (M = 41.8; SD = 19.2). The majority of the participants were L1 Swedish speakers with a Romance language as L2 (n = 16). Three participants had both Swedish and a Romance language as L1s. Finally, three participants had another L1 than Swedish (i.e. Finnish, Romanian, Russian), but they were highly proficient in Swedish.Footnote2 Additionally, all the participants had advanced knowledge of English as L2.Footnote3

5.2. Instruments

The participants completed three tests: two proficiency tests inspired by the C-test format (henceforth, C-tests) and an interpretation test. The C-tests consisted of two passages of 31 blanks each for a total of 62 blanks (Ågren et al., Citation2021; Bardel et al., Citationwork in progress), providing a measure of general proficiency in Italian and in the Romance language (Spanish or French) (Klein-Braley, Citation1985).

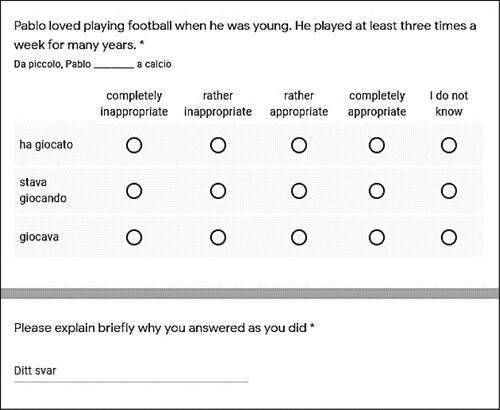

The Italian interpretation test (henceforth, IIT) was inspired by a test used by the SPLLOC research team (e.g. Domínguez et al., Citation2013). The IIT consisted of 16 tasks, of which 12 tested the three aspectual meanings (perfective, imperfective progressive, imperfective habitual) and four filler tasks. For perfective aspect, the three verb forms supplied in each context were passato prossimo, imperfetto and passato remoto. For habitual and progressive aspect, passato prossimo, imperfetto and the periphrasis stare + gerund were supplied.

Some combinations were expected to yield high acceptance rates (see Vallerossa et al., Citation2021, for a detailed description of the IIT). Passato prossimo and passato remoto rendered the perfective situations appropriate while imperfetto was the appropriate choice in habitual situations. Finally, imperfetto and the periphrasis were appropriate in progressive situations.

As shown in , learners had to evaluate how appropriately each verb form described the context on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from completely inappropriate to completely appropriate. Additionally, they left, after each task, a written reflection motivating their judgements, which they could write in Swedish, English, Italian, French or Spanish. These written reflections were used for the analysis.

5.3. Procedure

First, the researcher contacted instructors of Italian from seven different undergraduate courses at a Swedish university.Footnote4 Secondly, the researcher presented the project to the students enrolled in these courses. The students received oral and written information about the project. The students who wanted to participate gave their written consent. Prior to data collection, the researcher applied to the Swedish Ethical Review Authority for an ethical review of the project. Data were collected through video meetings on Zoom due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Each participant met the researcher individually or in small groups and completed the tests in two online sessions, each lasting approximately one hour. During the first session, the participants completed one C-test (either in Italian or in the Romance language). Depending on the C-test that they had received during the first session, the participants completed the other C-test in the second session. The IIT was completed during either the first or the second session. All tests were digitalised.

5.4. Data analysis

The results from the C-tests were used to create proficiency groups. Learners scoring higher than 49, i.e. 80% of 62, were considered to have high proficiency in Italian and in the Romance language.Footnote5 By combining the C-tests’ scores, learners were divided into four proficiency groups: the LowIta-LowRom group with low proficiency in both languages (n = 4), the LowIta-HighRom group, with low proficiency in Italian but high proficiency in Romance (n = 7), the HighIta-LowRom group, with low proficiency in Romance but high proficiency in Italian (n = 4), and the HighIta-HighRom group, highly proficient in both languages (n = 7).

shows descriptive statistic for the C-tests and the groups. The LowIta-LowRom group was less proficient in Italian than the LowIta-HighRom group, probably due to one outlier performing poorly in both C-tests. The HighIta-HighRom group was almost equally proficient in Italian and in their Romance language.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics (Mean; SD) for the C-tests in Italian and Romance languages.

The reflections from the IIT were first approached qualitatively, yielding categories, subcategories and codes, which were then counted to show their frequency and distribution across the groups. Qualitative Content Analysis (QCA) was applied, following Graneheim and Lundman (Citation2004). First, salient words and expressions, also referred to as condensed meaning units (CMU) in QCA, were extrapolated from each written reflection produced by the learners. From the CMU, codes were created aiming to maintain the original content. Codes were clustered into subcategories, which were subsequently grouped into higher-order categories (cf. ).

Two interpretative procedures were adopted: condensation, occurring horizontally from reflections to CMU, and aggregation, which occurred vertically, from codes to subcategories and from subcategories to categories. A category had to be externally exclusive and internally inclusive (Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004). exemplifies how the analysis of a reflection was carried out.

Table 3. Example of Qualitative Content Analysis.

In some cases, codes could correspond to subcategories, while in other cases subcategories further specified a category. The subcategory ‘aspect’ included several codes, for example ‘single’, ‘concluded’ and ‘habitual/iterative’, each referring to how verb forms express aspectual meanings. The same subcategory was in turn comprehended by the category ‘explicit rules’. Codes, subcategories and categories were created based on previous literature, drawing specifically on introspective studies (see Section 3.2).

The coding scheme was refined through an interpretative process of going through and comparing the reflections, the CMU, the codes and the (sub)categories multiple times (i.e. intrarater reliability). To guarantee interrater reliability, a random sample of 303 codes from the data set was submitted to another researcher for coding (Downe-Wamboldt, Citation1992, p. 314). A few codes were changed after discussing the cases of initial disagreement.

In total, there were 352 reflections (16 reflections for each participant), written in five languages. The reflections referring to filler items (n = 88) were excluded. The remaining reflections (n = 264) were analysed qualitatively. They yielded 545 CMU, which are the basis for the analysis. In each unit, one or several verb forms were commented on.

shows the occurrences of the reflections for each verb form. The reflections refer more often to why a verb form was chosen (e.g. ‘Here, the correct verb form is the imperfetto, because it describes Pablo as a person in the past and his habits [not a finite action]’) but not on why it was rejected. In the coding procedure, the rejected forms were preceded by ‘NOT’. There were 19 reflections not referring to specific verb forms.

Table 4. Occurrences of the groups’ reflections for each verb form.

6. Results

The results are divided into two sections corresponding to the two research questions. Data are first analysed qualitatively, creating categories, subcategories and codes (6.1) to investigate how the learners make sense of Italian past tense forms (i.e. RQ1). Group frequency and distribution are subsequently presented (6.2) in order to address how the nature of the learners’ comments varies depending on their proficiency levels in the Romance language and in Italian (i.e. RQ2).

6.1. Categories, subcategories and codes

Twenty-five codes were grouped into seven subcategories, which were in turn condensed into four categories. ‘Intuition’ and ‘uncertainty/unknown’ are counted as categories, while the codes ‘English’, ‘French’, ‘Swedish’ and ‘Romanian’ could refer to both the subcategories ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ (see Appendix 1).

As shown in , the majority of the reflections refer to the category ‘explicit rules’ (82.57%), followed by ‘other languages’ (6.24%) and ‘intuition’ (6.24%), and finally by ‘uncertainty/unknown’ (4.95%).

Table 5. Overall number of occurrences and percentage of categories and subcategories.

‘Intuition’ refers to learners expressing how certain forms sound or feel, as in reflection (1):

(1) I don't know the exact rule for this, but I can hear and intuit that the first option is the correct one

The category ‘explicit rules’ refers to learners exhibiting explicit knowledge about tenses. Within this category, five subcategories were found. Almost half of the reflections (46.61%) referred to the subcategory ‘aspect’, further divided into six codes: ‘single’ and ‘completed’ were often found in perfective contexts, ‘habitual/iterative’ in habitual contexts while ‘ongoing’, ‘interruption’ and ‘simultaneity’ generally occurred in progressive contexts. Reflection (2) provides an example of ‘aspect’ connected to the codes ‘single’ (once) and ‘habitual/iterative’ (often):

(2) Ha finito = hände en gång, men detta hände ofta = finiva

‘Ha finito = it happened once, but this happened often = finiva’

(3) happened not long ago = PP [passato prossimo]. PR [passato remoto] would be strange when the situation happened so close in time

(4) Passato prossimo because he handed in the exam at a certain point in time, not over a period of time like “during 3 years, always” etc.

(5) The time indication “last month” can give a hint that it should be passato prossimo as verb form here (emphasis added)

The category ‘other languages’ contained the subcategories ‘direct’ (1.83%) and ‘indirect’ (4.40%), depending on whether there was an explicit or implicit mention of reliance on other languages. The codes within the subcategories ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ were connected to the languages mentioned by the learners, namely English, French, Romanian and Swedish. Among indirect mentions, there were reflections containing terminology borrowed from other languages as in (6):

(6) She ate it and finished it, so I feel that passé composé is the best one. I think mangiò might be passé simple, which is more appropriate than imparfait (emphasis added)

6.2. Reflections categorised by proficiency groups

In the following section, the groups’ reflections are presented according to proficiency group. The 19 reflections not referring to any verb form were excluded. Further, only forms commented on positively were reported since they were the majority. The 40 instances commented on negatively were excluded. The analysis is therefore based on 486 reflections. The distribution of the reflections among the groups was uneven as there were more participants – and consequently more reflections – in the groups with high proficiency in the Romance language.

6.2.1. Low-proficiency learners

shows the occurrences of categories and subcategories in relation to verb forms commented on by low-proficiency learners.

Table 6. Categories and subcategories for low-proficiency learners and commented verb forms (IMP: imperfetto; PER: periphrasis; PP: passato prossimo; PR: passato remoto).

The category ‘explicit rules’ was the most common in both groups. Within the category ‘explicit rules’, the LowIta-LowRom group mainly employed the subcategory ‘tense’, connecting verb forms to a general notion of pastness. The second most-commented subcategory was ‘aspect’: passato prossimo was generally connected to a completed and single situation while imperfetto expressed a habitual situation. Finally, learners in the LowIta-LowRom group mentioned feelings about languages as in ‘I’d have used the 2nd mostly because it sounds better in my head’.

Moving to the LowIta-HighRom group, the subcategory ‘aspect’ was the most common within ‘explicit rules’: passato prossimo referred to concluded and single events while imperfetto was mostly connected to both habituality (n = 15) and ongoingness (n = 12). The periphrasis was connected to ongoingness, especially for events being interrupted. Generally, the mapping of aspectual meanings onto verb forms was felicitous but there were cases where it was target-deviant as in (7), where imperfetto and the periphrasis were both believed by the learner to be adequate to express habitual aspect:

(7) Imperfekt är ganska ok, […] gerund[i]um är bättre för den ger en [å]terkommande aktivitet

‘imperfekt is rather okay, […] the gerund is better because it gives a repeated activity’

(8) [I]mp. [imperfetto] går knappast, det är ju ingenting som pågår en längre tid

‘Imperfetto barely works, it is nothing that goes on for a longer period of time’

(9) These all sound appropriate to me, but they have a different tone and focus. Fu sounds very dramatic, è stato emphasises the trip as a whole, era more views the trip as a process (emphasis added)

(10) Här känns det som att passato prossimo är rätt eftersom det beskriver en enstaka händelse i dåtid. jag tänker att det borde vara som passé composé på franska

‘Here it feels like passato prossimo is correct because it describes a single event in the past. I think it should be like passé composé in French’ (emphasis added)

6.2.2. High-proficiency learners

shows the occurrences of categories and subcategories in relation to verb forms commented on by high-proficiency learners.

Table 7. Categories and subcategories for high-proficiency learners and commented verb forms (IMP: imperfetto; PER: periphrasis; PP: passato prossimo; PR: passato remoto).

Both high-proficiency learner groups consistently relied on explicit rules while the occurrences of the categories ‘intuition’ (n = 3) and ‘uncertainty/unknown’ (n = 3) were very limited. Moreover, the reflections of high-proficiency learners were rather sophisticated, as they often generated many subcategories. In (11), passato prossimo was chosen based on three cues: the event was located in the past, it happened once and there was a trigger, i.e. ‘last month’.

(11) […] passato prossimo […] describes an event in the past that happen[e]d only once (it is not a general description, etc). The time indication “last month” can give a hint that it should be passato prossimo as verb form here (emphasis added)

Further, both groups relied on the subcategories ‘tense’ and ‘lexical aspect’. The latter was consistently employed by the HighIta-HighRom group while the HighIta-LowRom group preferred the subcategory ‘tense’. Further, the subcategory ‘tense’ was generally used in combination with other categories, specifying the temporal location of a situation. Regarding lexical aspect, learners in the HighIta-HighRom group chose perfective morphology based on the semantic properties of telicity and punctuality, as in (12):

(12) È riuscito a inviare l'esame a un certo punto e l'ha fatto recentemente

‘He succeded in sending the exam at a certain point and he did it recently’

(13) mentre + imperfetto + passato prossimo. When an action in the past is interrupted by another action (in the same sentence) (emphasis added)

Although to a limited extent, both groups fell back on indirect mentions of previous languages, mostly Swedish, as they provided translations of Italian verb forms, as in Medan elle[r] när hon skickade (‘While or when she sent’), where both periphrasis and imperfetto were judged as correct, based on a Swedish translation.

7. Discussion

In the present study, the learners’ reflections generated four categories, namely ‘explicit rules’, ‘intuition’, ‘other languages’ and ‘uncertainty/unknown’. ‘Other languages’ included the subcategories ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ while the category ‘explicit rules’ included five subcategories, that are ‘aspect’, ‘grounding/sociolinguistic varieties’, ‘lexical aspect’, ‘tense’ and ‘triggers’. Also, the distributions of these categories and subcategories varied depending on the learners’ proficiency level in Italian and in their Romance language.

On the one hand, and similar to the findings by Comajoan (Citation2019) concerning beginner learners of Catalan, the reflections of beginners with low proficiency in Romance languages were mostly time-related, as they undistinguishably connected past tense forms to a general notion of pastness. This result also corroborates the DPTH (Salaberry, Citation2000, Citation2008; Wiberg, Citation1996). On the other hand, beginners with high proficiency in Romance relied more consistently on ‘aspect’ than on temporal strategies. High proficiency in a Romance language resulted in an advantage in being able to interpret both the progressive and the habitual meanings of imperfetto. This outcome aligns with previous studies on learning aspect in an additional language, attesting positive L2 transfer from a typologically similar language (Diaubalick et al., Citation2020; Eibensteiner, Citation2019; Salaberry, Citation2005; Vallerossa, Citation2021; Vallerossa et al., Citation2021). The mapping of aspectual meanings onto verb forms is yet idiosyncratic (cf. Comajoan, Citation2019) and may lead to incorrect one form-one meaning associations (cf. the One-to-One Principle of Andersen, Citation1993). In line with Izquierdo and Collins (Citation2008), the predicates’ durativity, or lack thereof, was also crucial for the choice between imperfetto and passato prossimo.

Furthermore, learners in the LowIta-HighRom group in our study used different languages as resources for making sense of different tenses, which was attested in Comajoan (Citation2019): the Italian distinction passato prossimo/passato remoto was equated to the French one passé compose/passé simple, the Italian periphrasis was interpreted in the light of the English ‘be + V–ing’, and the imperfetto was connected to the French imparfait. Finally, learners in our LowIta-HighRom group made use of intuition more consistently than all other groups did. However, it is difficult to ascertain where these feelings about language originate (cf. Vallerossa & Bardel, Citationwork in progress).

Compared to low-proficiency learners, high-proficiency learners mentioned explicit rules more frequently, while they seldom relied on the category ‘intuition’. Such result confirms previous studies on the high-proficiency learners’ use of pedagogical rules or rules of thumb to make sense of inflectional morphology (Collins, Citation2005; Izquierdo & Collins, Citation2008). Unlike low-proficiency learners, the subcategory ‘tense’ did not occur in isolation but it functioned as a complement to other types of reflections for high-proficiency learners. The combination of several categories also reflects the strategy clusters identified in Comajoan (Citation2019). Furthermore, time-related reflections incorporated temporal distance, thus helping these learners locating a situation in the recent or remote past. High-proficiency learners in our sample consistently relied on Swedish rather than other L2s, arguably because they had already mapped aspectual functions onto target forms. A similar reliance on the L1 in concomitance with increased target language proficiency was found in a longitudinal case study and interpreted ‘as a compensatory strategy with the aim of overcoming lexical problems in Italian’ (Bardel & Lindqvist, Citation2007, p. 135). However, the same result needs to be cautiously interpreted in our case as not all learners had Swedish as L1.

The subcategory ‘lexical aspect’ also encompassed, among high-proficiency learners, the distinction between telic/atelic and dynamic/stative predicates, corroborating previous studies, where the imperfective tense was consistently connected to unchanging events (Collins, Citation2005; Liskin-Gasparro, Citation2000). Finally, within the high-proficiency group, the HighIta-HighRom group made reference to triggers and sociolinguistic varieties.

In the analysis reported here, it was not possible to connect the categories that emerged from the reflections to prototypical and non-prototypical associations because learners commented on tenses in general, regardless of the context. Future studies need to address how these categories vary depending on the type of context (see for example Vallerossa & Bardel, Citationwork in progress). Another limitation is that the study is based on interpretation data and it is therefore not illustrative of how learners use tenses in production (Vallerossa, Citation2021). Time-related constraints may be crucial for the type of categories, not least for the languages that are activated in real time processing vis-à-vis in offline tasks. Finally, in spite of common aspects regarding undergraduate studies of Italian in Sweden, for example the fact that Italian is almost never approached as a true second language (Bardel, Citation2006), there is considerable variation, not least related to age and linguistic background. The sample reflects this heterogeneity. Therefore, in spite of the limited sample, this study based on 22 learners can, at least partly, help shedding light on how multilingual learners with varying proficiency levels in two typologically similar languages resonate when they have to make sense of verb morphology.

8. Conclusion

This study explored the written introspective reflections on Italian past tense verb forms expressed by multilingual learners with varying proficiency levels in a background Romance language and in Italian as an additional language.

To conclude, the nature of learners’ reflections on tempo-aspectual morphology in our study depends on their proficiency in previously known Romance languages and Italian. Learners’ reflections become more sophisticated with increased target language proficiency, by incorporating different layers of information. The initially predominant temporal function of tenses is successively integrated by form-function mapping of aspectual meanings and lexical aspect. In this process, high proficiency in a previous Romance language results in an advantage among beginners of Italian, especially for progressive aspect. While our beginner learners with high proficiency in a Romance language rely on Romance languages and English, advanced learners refer to Swedish, which is the L1 of the majority of our learners, regardless of their proficiency level in a Romance language. Finally, learners become more decisive as target language proficiency increases. This is reflected in the fact that explicit rules progressively take over feelings and intuitions about languages, which instead are more typical of the reflections of low-proficiency learners.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Following Faerch and Kasper (Citation1986, p. 215), ‘introspection’ refers to a set of methodologies requiring the learners to reflect upon and comment, orally or in writing, on their performance in linguistic tasks of various types. Within introspective methodologies fall for example retrospection, where test-takers recollect what they were thinking when they responded, and think-aloud protocols where they are asked to verbalise their thoughts as they respond to items (Hughes, Citation2003, pp. 31–32).

2 The fact that some participants had a Romance language as L1 or one of the L1s is a limitation of the study. We are aware that excluding these participants would have made the sample cleaner. However, in this study, we decided to include these learners in the final sample for two reasons. First, in order to ensure ecological validity. In fact, the sample represents the real composition of students’ background languages in the current context. Second, the decision to include these participants was connected to the aim of the study, namely to investigate how the way multilingual learners make sense of verbal morphology develops with increased target language proficiency.

3 Proficiency in English comparable to the B2.1 level in the Common European Framework for Languages (Council of Europe, Citation2001) is an eligibility requirement for undergraduate studies in Italian. Since all learners had high English proficiency, its effects are deemed similar across the groups.

4 The seven undergraduate courses from which the participants were recruited consisted of two preparatory courses of 15 ECTS each (preparatory I, preparatory II) and five courses of 30 ECTS each (Italian I, Italian II, Italian III, Italian IV and Kandidat ‘Bachelor thesis course’). In the most advanced course within undergraduate studies (i.e. Kandidat), students have to write a thesis about Italian literature or linguistics, which would approximately be equivalent to the advanced level C1 in the Common European Framework for Languages (Council of Europe, Citation2001). The distribution of the participants is as follows: four participants were recruited from the first preparatory course of Italian, five from the second preparatory course, four from Italian I, three from Italian II, three from Italian III, two from Italian IV and one from the Bachelor thesis course in Italian (Kandidat).

5 We are aware that the cut-off value can be considered too high for a threshold. However, learners were undergraduate students with rather high target language proficiency. Therefore, the threshold was considered adequate in relation to the learner sample investigated here.

References

- Ågren, M., Bardel, C., & Sayehli, S. (2021, June 9–11). Same or different? Comparing language proficiency in French, German and Spanish in Swedish lower secondary school [Paper presentation]. Conference Exploring Language Education (ELE) 2021: Teaching and Learning Languages in the 21st Century, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway.

- Andersen, R. (1993). Four operating principles and input distribution as explanation for underdeveloped and mature morphological systems. In K. Hyltenstam & Å Viberg (Eds.), Progression and regression in language (pp. 309–339). Cambridge University Press.

- Angelovska, T., & Hahn, A. (Eds.). (2017). L3 syntactic transfer: Models, new developments and implications. John Benjamins.

- Bardel, C. (2005). L’apprendimento dell’italiano come L3 di un apprendente plurilingue. Il caso del sistema verbale. In M. Metzeltin (Ed.), Omaggio a/Hommage à/Homenaje a Jane Nystedt (pp. 9–16). Drei Eidechsen.

- Bardel, C. (2006). DITALS di I e II livello per gli insegnanti di italiano in Svezia. In P. Diadori (Ed.), La DITALS risponde 3 (pp. 187–190). Guerra.

- Bardel, C., & Falk, Y. (2007). The role of the second language in third language acquisition: The case of Germanic syntax. Second Language Research, 23(4), 459–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658307080557

- Bardel, C., & Falk, Y. (2012). The L2 status factor and the declarative/procedural distinction. In J. C. Amaro, S. Flynn, & J. Rothman (Eds.), Third language acquisition in adulthood (pp. 61–78). John Benjamins.

- Bardel, C., & Lindqvist, C. (2007). The role of proficiency and psychotypology in lexical cross-linguistic influence. A study of a multilingual learner of Italian L3. In M. Chini, P. Desideri, M. E. Favilla, & G. Pallotti (Eds.), Atti del VI Congresso Internazionale dell'Associazione Italiana di Linguistica Applicata, Napoli 9−10 febbraio 2006 (pp. 123–145). Guerra.

- Bardel, C., & Sánchez, L. (Eds.). (2020). Third language acquisition: Age, proficiency and multilingualism. Language Science Press.

- Bardel, C., Sayehli, S., & Ågren, M. (work in progress). Developing a C-test for young learners of foreign languages at the A1-A2 level in Sweden. Methodological considerations.

- Bardovi-Harlig, K., & Comajoan-Colomé, L. (2020). The aspect hypothesis and the acquisition of L2 past morphology in the last 20 years. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 42(5), 1137–1167. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263120000194

- Cabrelli Amaro, J., Flynn, S., & Rothman, J. (Eds.). (2012). Third language acquisition in adulthood. John Benjamins.

- Collins, L. (2005). Accessing second language learners’ understanding of temporal morphology. Language Awareness, 14(4), 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410508668837

- Comajoan, L. (2019). Cognitive grammar learning strategies in the acquisition of tense-aspect morphology in L3 Catalan. Language Acquisition, 26(3), 262–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/10489223.2018.1534965

- Comrie, B. (1976). Aspect. Cambridge University Press.

- Conteh, J., & Meier, G. (Eds.). (2014). The multilingual turn in languages education: Opportunities and challenges. Multilingual Matters.

- Council of Europe. (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge University Press.

- Diaubalick, T., Eibensteiner, L., & Salaberry, M. R. (2020). Influence of L1/L2 linguistic knowledge on the acquisition of L3 Spanish past tense morphology among L1 German speakers. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2020.1841204

- Domínguez, L., Tracy-Ventura, N., Arche, M. J., Mitchell, R., & Myles, R. (2013). The role of dynamic contrasts in the L2 acquisition of Spanish past tense morphology. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 16(3), 558–577. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728912000363

- Downe-Wamboldt, B. (1992). Content analysis: Method, applications, and issues. Health Care for Women International, 13(3), 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399339209516006

- Eibensteiner, L. (2019). Transfer in L3 acquisition: How does L2 aspectual knowledge in English influence the acquisition of perfective and imperfective aspect in L3 Spanish among German-speaking learners? Dutch Journal of Applied Linguistics, 8(1), 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1075/dujal.19003.eib

- Faerch, C., & Kasper, G. (1986). Cognitive dimensions of language transfer. In E. Kellerman & M. Sharwood Smith (Eds.), Crosslinguistic influence in second language acquisition (pp. 49–65). Pergamon Press.

- Falk, Y., Lindqvist, C., & Bardel, C. (2015). The role of L1 explicit metalinguistic knowledge in L3 oral production at the initial state. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 18(2), 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728913000552

- Foote, R. (2009). Transfer and L3 acquisition: The role of typology. In Y.-K. I. Leung (Ed.), Third language acquisition and universal grammar (pp. 89–114). Multilingual Matters.

- Giacalone Ramat, A. (2002). How do learners acquire the classical three categories of temporality? Evidence from L2 Italian. In R. Salaberry & Y. Shirai (Eds.), The L2 acquisition of tense-aspect morphology (pp. 200–221). John Benjamins.

- Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- Hufeisen, B. (2018). Models of multilingual competence. In A. Bonnet & P. Siemund (Eds.), Foreign language education in multilingual classrooms (pp. 173–190). John Benjamins.

- Hughes, A. (2003). Testing for language teachers. Cambridge University Press.

- Izquierdo, J., & Collins, L. (2008). The facilitative role of L1 influence in tense-aspect marking: A comparison of Hispanophone and Anglophone learners of French. The Modern Language Journal, 92(3), 350–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2008.00751.x

- Jessner, U. (2006). Linguistic awareness in multilinguals: English as a third language. Edinburgh University Press.

- Kihlstedt, M. (1998). La référence au passé dans le dialogue. Étude de l’acquisition de la temporalité chez des apprenants dits avancés de français [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Stockholm University.

- Klein-Braley, C. (1985). A cloze-up on the C-test: A study in the construct validation of authentic tests. Language Testing, 2(1), 76–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/026553228500200108

- Labeau, E. (2005). Beyond the aspect hypothesis. Tense-aspect development in advanced L2 French. EUROSLA Yearbook, 5, 77–101.

- Lindqvist, C., & Bardel, C. (2014). Exploring the impact of the proficiency and typology factors: Two cases of multilingual learners’ L3 learners. In M. Pawlak & L. Aronin (Eds.), Essential topics in applied linguistics and multilingualism: Studies in honor of David Singleton (pp. 253–266). Springer International Publishing.

- Liskin-Gasparro, J. (2000). The use of tense-aspect morphology in Spanish oral narratives: Exploring the perceptions of advanced learners. Hispania, 83(4), 830–844. https://doi.org/10.2307/346482

- May, S. (Ed.). (2013). The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL and bilingual education. Routledge.

- McManus, K. (2015). L1/L2 differences in the acquisition of form-meaning pairings: A comparison of English and German learners of French. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 71(2), 51–77. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.2070.51

- Puig-Mayenco, E., González Alonso, J., & Rothman, J. (2020). A systematic review of transfer studies in third language acquisition. Second Language Research, 36(19), 31–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658318809147

- Rothman, J. (2011). L3 syntactic transfer selectivity and typological determinacy: The typological primacy model. Second Language Research, 27(1), 107–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658310386439

- Rothman, J. (2015). Linguistic and cognitive motivations for the typological primacy model (TPM) of third language (L3) transfer: Timing of acquisition and proficiency considered. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 18(2), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1017/S136672891300059X

- Salaberry, M. R. (2000). The development of past tense morphology in L2 Spanish. John Benjamins.

- Salaberry, M. R. (2005). Evidence for transfer of knowledge of aspect from L2 Spanish to L3 Portuguese. In D. Ayoun & M. R. Salaberry (Eds.), Tense and Aspect in Romance languages: Theoretical and applied perspectives (pp. 179–210). John Benjamins.

- Salaberry, M. R. (2008). Marking past tense in second language acquisition. A theoretical model. Continuum.

- Salaberry, M. R. (2020). The conceptualization of knowledge about aspect. In C. Bardel & L. Sánchez (Eds.), Third language acquisition: Age, proficiency and multilingualism (pp. 43–65). Language Science Press.

- Shirai, Y., & Andersen, R. (1995). The acquisition of tense-aspect morphology: A prototype account. Language, 71(4), 743–762. https://doi.org/10.2307/415743

- Squartini, M., & Bertinetto, P. M. (2000). The simple and compound past in Romance languages. In Ö Dahl (Ed.), Tense and aspect in the languages of Europe (pp. 403–440). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Vallerossa, F. (2021). The role of linguistic typology, target language proficiency and prototypes in learning aspectual contrasts in Italian as additional language. Languages, 6(4), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040184

- Vallerossa, F., & Bardel, C. (work in progress). “He was finishing his homework or il finissait ses devoirs”: A study of multilingual students’ reflections on Romance verb morphology.

- Vallerossa, F., Gudmundson, A., Bergström, A., & Bardel, C. (2021). Learning aspect in Italian as additional language. The role of second languages. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2021-0033

- Westergaard, M., Mitrofanova, N., Mykhaylyk, R., & Rodina, Y. (2017). Crosslinguistic influence in the acquisition of a third language: The linguistic proximity model. International Journal of Bilingualism, 21(6), 666–682. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006916648859

- Wiberg, E. (1996). Reference to past events in bilingual Italian-Swedish children of school age. Linguistics, 34(5), 1087–1114. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.1996.34.5.1087

- Williams, S., & Hammarberg, B. (1998). Language switches in L3 production: Implications for a polyglot speaking model. Applied Linguistics, 19(3), 295–333. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/19.3.295