ABSTRACT

The main aim of the article is to identify Slovenian children’s attitudes towards foreign languages (FL), their motivation for learning languages, the influence of different significant others (teachers, parents, peers) on their language attitudes, and the ways they perceive languages which they are exposed to. The focus is on FLs in general rather than on a particular FL. The study is linked to the project ‘Languages Matter’ whose principal goal is to determine which factors support the creation of a supportive learning environment for the development of plurilingualism in the Slovenian school context. The article presents the results of a survey conducted in different primary schools in Slovenia on a population of 472 pupils aged 8/9 (n = 472). The survey questionnaire consists of two parts. The first part uses the LANGattMini scale (Bratož et al., 2021) to investigate the following factors: FL learning motivation, FL attitudes, and importance of significant others. The second part uses a qualitative paradigm and aims to gain an insight into the respondents’ perceptions of FLs. The results of the study indicate that children‘s attitudes towards FLs are generally positive but at the same time build a complex picture of interdependence between attitudes, motivation, and significant others.

Introduction

The role and significance of language diversity in educational contexts has been investigated from a variety of perspectives and contexts, extending to research areas, such as language awareness, multilingualism, plurilingual education, and others. What all these fields have in common is the underlying notion that we should promote positive attitudes not towards a particular language, but towards languages in general. This is also the principal goal of the project ‘Languages Matter’Footnote1 which has been founded by the European Social Fund and the Ministry of Education in Slovenia. As elsewhere in Europe, teachers in Slovenia are today increasingly faced with the challenges of teaching linguistically and socio-culturally diverse classrooms which requires from them both new competences and understandings of the teaching and learning situation. Therefore, the project’s main aim is to determine which factors support and which hinder the creation of a supportive learning environment for the development of plurilingualism in the Slovenian school context. Individual perceptions and attitudes towards different languages, those who speak them and the cultures to which they are linked have been found to be one of the most powerful obstacles to establishing efficient policies of linguistic diversity (Council of Europe, Citation2000). An important aspect of the project has thus been the identification of language attitudes and perceptions of different stakeholders, including learners at different levels of schooling (from pre-school to university level). The research presented in this article focuses on third-grade pupils aged 8/9 and their attitudes towards foreign languages in general, their motivation for learning languages, the importance of significant others (teachers, parents, peers) and the ways they perceive foreign languages which they are exposed to and have experience with.

Language awareness and language diversity

As Sayers and Láncos (Citation2017) point out, linguistic diversity is a complicated concept which incorporates both an inventory of languages as well as all the possible variations within and between them. One of the fields that has put language diversity at the centre of its concern is the area of language awareness (LA). Several authors (Cots, Citation2008; Finkbeiner & White, Citation2017; Oliveira & Ançã, Citation2009; Svalberg, Citation2007) argue that LA plays an important role in the development of multilingualism and plurilingual competence. An important aspect of LA is thus the promotion of positive attitudes towards both different varieties of a language and other languages spoken by learners at school. Indeed, one of the most valuable benefits of raising LA in school is to promote positive attitudes towards all languages (Little et al., Citation2013).

With the introduction of the concept of plurilingual competence, the perspective has shifted from focusing on linguistic diversity in terms of different languages on offer in a particular school or education system to focusing on the individual and the range of linguistic means available to him or her. However, as Beacco and Byram (Citation2007) amply argue, the idea of plurilingualism needs to transcend the narrow sense of managing language diversity to include both the people’s positive attitudes towards their mother tongue and other languages as well as an openness to other cultures. This also implies an increased motivation and curiosity about other languages as a pre-requisite for the development of people’s own linguistic repertoires. At the same time, an important assumption of plurilingual education is that learning different languages and expanding learners’ linguistic repertoires does not necessarily lead to positive attitudes towards other languages and cultures. That is why ‘plurilingual education should be a component of all language teaching and have a more clear-cut place in the curriculum the more the language(s) taught is(are) dominant, legitimate or considered decisive in social representations’ (Citation2007, pp. 68–69).

A concept which also promotes linguistic diversity and is seen as partly overlapping with plurilingualism is translanguaging (Carbonara & Scibetta, Citation2020; García & Otheguy, Citation2020). While the primary focus of plurilingual education has been making sure that learners develop a ‘repertoire of languages’, translanguaging goes beyond the perception of language from a traditional perspective by focusing on ways bilinguals perform their bilingualism and identify with the role of bilingual beings (García & Otheguy, Citation2020, p. 24). In this sense, translanguaging reflects a strong socio-political dimension as it challenges the power hierarchies which position languages in a certain way according to their status in a society (García & Otheguy, Citation2020).

Another initiative, which focused on promoting language diversity, emerged in France in the 1990 and became known as the evlang or ‘language awakening’ (éveil aux langues) approach. It was aimed at promoting the appreciation of language diversity in the classroom (Candelier & Kervran, Citation2018; Darquennes, Citation2017; Finkbeiner & White, Citation2017; Svalberg, Citation2007). The main idea behind the notion of awakening to languages was not to teach and learn different foreign or second languages but rather to encourage learners to consciously reflect on language as a system and on a variety of different languages (including the learners’ home languages, dialects, sign languages, etc.), thus considering the role of language diversity in their own lives and society as a whole. Darquennes (Citation2017) argues that the language awakening approaches are inclusive in character as their aim is not language learning as such but, above all, raising awareness of linguistic diversity.

As elsewhere in Europe, the language awakening approach has been disseminated in Slovenia with the Ja-Ling Comenius – Janua Linguarum project which was aimed at raising primary school pupils’ awareness of the significance of linguistic and cultural diversity through developing efficient plurilingual materials (Fidler, Citation2006). A number of projects and initiatives carried out in Europe in the last two decades have promoted the principles of plurilingual and intercultural education. However, as Candelier et al. (Citation2012) point out, there is a considerable discrepancy between the plurilingual concepts laid out in the EU documents and the reality of everyday language teaching and learning in schools. An important aspect of this reality are the attitudes and perceptions of the learners of different age groups and in different linguistic environments towards foreign languages and the languages which surround them.

Language attitudes and children

In researching attitudes towards foreign languages (FL) and FL learning, it is necessary to consider the relationship between attitudes, motivation and language performance as well. Especially motivation is seen as a variable of individual learners’ differences that is closely related to language attitudes. Gardner (Gardner, Citation1985; Masgoret & Gardner, Citation2003) identified five attitude/motivation variables, namely integrativeness, attitudes towards the learning situation, motivation, integrative orientation, and instrumental orientation. The last two variables that focus on the reasons for learning the target language are especially relevant for our research. Integrative orientation refers to the reasons which are related to the extent to which learners are willing to identify with the target language community, while the concept of instrumental orientation refers to the desire to learn a language for practical reasons, such as getting a job or living abroad. The research conducted by Gardner and his associates implied that students who are integratively motivated for learning a FL will be better language learners than those who are instrumentally motivated. However, as Ehrman et al. (Citation2003) point out, integration with the target culture and community is not always possible. Other researchers (e.g. Mihaljević Djigunović, Citation2012; Noels, Citation2001; Žefran, Citation2015) suggest considering other relevant variables, such as travel, friendship, achievement or language aptitude, language anxiety, language learning styles, and others. According to Dörnyei et al. (Citation2004, p. 89), the motivation to learn a second language is a ‘multifaceted construct’ which encompasses several aspects, such as the learner's attitudes towards the target language and their culture, personality and identity issues, and other factors.

The growing interest in plurilingual education has given rise to a wave of research on the role of attitudes in language learning. There is convincing evidence that language awareness develops from age four to six (Aboud, Citation1976; Mercer, Citation1975). When studying the ways in which multilingual children construct their reading identities, Wagner (Citation2020) found out that 4/5-year-olds not only demonstrated awareness of their own languages but were also able to express language preferences and show emerging metalinguistic awareness. However, Garrett et al. (Citation2003) point out that when it comes to language attitudes, conclusions on the attitudinal development of young children or even young adults should be considered in perspective as language attitudes may change during a child's formative years and may not be fully developed before puberty, especially when it comes to perceiving the social significance of a particular language or language dialect. Attitudes and motivation are therefore dynamic phenomena which change over time. Children’s language attitudes towards FLs have been found to be generally very positive (Enever, Citation2011; Nikolov & Mihaljević Djigunović, Citation2019). Young learners are both intrinsically and extrinsically motivated to learn FLs although they have been observed to experience various levels of anxiety related to FL learning which may have a negative effect on their motivation (Mihaljević Djigunović & Nikolov, Citation2019).

Parents, teachers, and peers are seen as important external factors which affect language learning motivation. In an analysis of the language learning attitudes and motivation of Hungarian children between the ages of 6 and 14, Nikolov (Citation1999) concluded that the most important motivating factors included positive attitudes towards the learning context and the teacher, as well as intrinsically motivating activities. At the same time, the study showed that classroom practice presented a stronger motivating factor than integrative or instrumental reasons. It is clear from the study that the teacher has a dominant influence especially in the early years, while peers become increasingly important between aged 8 and 11 as they gradually turn into ‘motivational role models’ (Nikolov & Mihaljević Djigunović, Citation2019, p. 285).

Most studies in this field analysed attitudes towards a particular language or languages, and the majority of these dealt with English as a FL (Carreira, Citation2006; Masgoret et al., Citation2001; Nagy, Citation2009; Nikolov, Citation1999, Citation2009; Takada, Citation2003). A few studies focused on comparing attitudes to specific languages. Mihaljević Djigunović and Bagarić (Citation2007) compared children’s attitudes towards English and German, while Dörnyei et al. (Citation2006) conducted a large survey on motivation in second language learning in which they explored Hungarian learners’ interest in learning English, German, French, Italian, and Russian. On the other hand, ELLiE (Enever, Citation2011), a transnational longitudinal study which focused on the policies and implementation processes for early FL learning programmes in Europe did consider FLs in general. The study primarily investigated the impact of various individual and environmental factors on language achievement and elements of FL learning, such as the learning environment and the learning situation. Another relevant study was conducted by Prasad (Citation2020) who investigated 9–11-year-old children’s perceptions of linguistic diversity and their ideas of what it felt to be plurilingual. To this end, the author decided to explore children’s collages as research artefacts and at the same time tools for reflecting on their experience as plurilingual individuals. This art-based inquiry method enabled them to gain valuable insights into the ways children perceive and conceptualise linguistic diversity. Other studies which also include children’s attitudes and perceptions concentrate on bilingual experiences. The study conducted in Scotland by Peace-Hughes et al. (Citation2021) explored pupils’ perceptions of their own bilingualism and stressed both the key role of parents and family as well as a variety of community-based support systems for developing active bilingual practices.

The Slovenian context

In order to gain an insight and a broader understanding of the learners’ attitudes towards FLs, we need to look at the linguistic situation in the Slovenian context. Slovenia is a small country characterised by a relatively high language diversity. Slovenian is the official language of the Republic of Slovenia. However, in areas populated by Italian and Hungarian ethnic communities, Italian and Hungarian have the status of co-official languages. In the area with the Italian national community, children attend kindergartens and schools with either Italian as the language of instruction and Slovene as one of the compulsory school subjects or Slovene as the language of instruction and Italian being taught as the language of the environment. In the ethnically mixed area with the Hungarian national community, children attend bilingual schools (in Slovene and Hungarian).

The first FL, English (or German in parts along the Austrian border) is introduced already in the first grade of primary school (for 6-year-olds) as an elective subject and becomes part of the obligatory curriculum in the second grade. From fourth grade (9-year-olds) onwards, children can choose to learn a second FL as an elective subject. The most frequently selected languages taught as a second FL in primary school are German, French, Spanish, and Italian.

Study and procedure

Research design

In the last decades, the view of the role of children in research has changed and contemporary research methods have begun to involve children as active participants, obtaining children's opinions directly from them and not through intermediaries, i.e. parents, teachers, etc. Children are seen as a credible source of data for things related to them (Fuchs, Citation2005; Kuchah & Pinter, Citation2012; Read & Fine, Citation2005). Using a direct approach for researching children’s attitudes and beliefs, it is necessary to take into account their cognitive, communicative, and social development. Special attention should be paid to the design of the survey and the way it is conducted (Bratož et al., Citation2021). One of the key factors to consider is the child's cognitive development (Bell, Citation2007; Borgers et al., Citation2000), especially the ability for abstract thinking, understanding concepts and logical sequences, and language memory. Several authors (Bell, Citation2007; De Leeuw, Citation2011) point out that when designing surveys for this age group, one should follow certain language requirements, such as avoiding vague and ambiguous formulations, negative and complex sentences, and complex expressions, but also using short, simple sentences and questions with fewer possible answers or the yes/no option.

In the present study, we decided to use a direct approach to identify Slovene children’s attitudes towards FLs in general. With respect to attitudes, we were especially interested in different aspects of children’s motivation for learning FLs, their attitudes towards FLs, and the influence of different significant others (teachers, parents, peers) on their language attitudes. Besides their attitudes towards FLs, we were also interested in the ways they perceive the FLs they are exposed to and have experience with.

Since the mixed-methods approach provides a more complete understanding of a research problem (Creswell, Citation2014), it was decided to use the convergent parallel mixed-methods model which converges or merges quantitative and qualitative data in order to provide a comprehensive analysis of the research problem. In this approach, both forms of data are collected simultaneously and the information is integrated into the interpretation of the overall results. The benefit of such a method is that one dataset might help explain the other or shed light on the research topic from different angles.

A survey was carried out based on a questionnaire designed in the Slovene language and consisting of two parts. In the first part, we used the LANGattMini scale, an instrument which was constructed and validated with an aim of identifying three dimensions: children’s FL learning motivation, FL attitudes, and significant others. (Bratož et al., Citation2021). The FL learning motivation dimension consists of 6 statements, while the FL attitudes and Significant others dimensions each consist of 5 statements to which participants responded on a 3-point Likert scale (1-I disagree, 2-I partly agree, 3-I agree) following the recommendation by Borgers et al. (Citation2000) to use a limited set of response options (up to three) with children before the age of ten. Cronbach’s alpha shows the acceptable reliability of the dimension FL attitudes (α = .702) and the Significant others dimension (α = .725), whereas the dimension FL learning motivation (F1) (α = .801) demonstrates good reliability.

The second part of the questionnaire consists of two sentence completion tasks, an open-ended question, a question with a drop-down list of answers and a personal question asking respondents about their gender. In the two sentence completion tasks (‘It's good to know foreign languages because … ’ and ‘A person who knows more foreign languages is … ’) children elaborated on their FL attitudes, motivation and importance of significant others. In the open-ended question, children were asked to think of an interesting word in a FL. This question was intentionally left open in order to gain an insight into the ways they perceive FLs. We were especially interested in the variety of languages the respondents would include in their answers and in how they would present them. In addition, to get a picture of the languages the children are exposed to, we included a question with a drop-down list of answers (‘Which foreign languages do you know?’). The decision to use the term ‘foreign languages’ rather than other expressions (second, other or additional languages) was based on the results of the questionnaire piloting in which children expressed confusion when terms other than ‘foreign language’ were used.

Following the advice for surveying children in this age group, the original questionnaire was pretested and subsequently modified on the basis of the feedback received from the participants. For example, the statement ‘if you speak more languages, you are cool’ turned out to be ambiguous so it was reformulated to ‘those who speak more languages are cool’ as in the piloting stage one of the respondents commented that ‘he did not speak more languages’, evidently understanding ‘if you speak more languages’ as referring to himself rather than to people in general (see Bratož et al., Citation2021).

The schools were given the choice to conduct the survey online (199 respondents) or offline (273 respondents). The process of completing the questionnaire was supervised and assisted by the pupils’ teachers who read the questions aloud to the participants and helped them use the computer in the online survey.

Participants

The participants in our study were third-grade pupils (aged 8/9) from different primary schools in Slovenia (n = 472) which participated in the ‘Languages matter’ project.

Data analysis

Basic descriptive statistics (Minimum, Maximum, Mean, Standard Deviation) were first used to analyse the individual items which were then combined into three dimensions: FL learning motivation, FL attitudes, and Importance of significant others. To determine if and how each of these three dimensions predict the other two dimensions, we conducted multiple regressions using the Stepwise method. Lastly, the data generated from the sentence completion tasks were analysed using a qualitative analysis approach.

Results

The results of the study are presented following the dimension analysed. The results for the first two dimensions, FL learning motivation and FL attitudes, are presented by combining the quantitative and qualitative paradigm. For the third dimension, in which we look at the importance of significant others, we present the results of descriptive statistics for individual items as well as a regression analysis indicating the most important predictors of attitudes towards FLs. The last section, which is related to the qualitative part of the survey, shows the results of the analysis of the reflections of children’s own linguistic repertoires and the ways in which they perceive FLs. This is an important aspect of our inquiry as it foregrounds the significance of the children’s own perspective and the ways they make sense of the languages which they are exposed to and have experience with.

FL learning motivation

The results in show that, on average, the children are generally highly motivated for FL learning (the mean varies from M = 2.63 (SD = 0.63) to M = 2. 92 (SD = 0.31)). For the individual items, it can be noted that the respondents express the highest level of agreement with the statements that relate to the practical aspect of language use. Specifically, they report they are highly motivated to learn FLs because you can speak with people from other countries (M = 2.93, SD = 0.31), because you can get a better job (2.81, SD = 0.48) and because you can travel more (M = 2.78, SD = 0.53). A slightly lower (but still high) motivation is reported for other reasons: because you can watch cartoons, play games, and listen to music in these languages (M = 2.72, SD = 0.85), because they like learning languages at school and outside school (M = 2.67, SD = 0.57), and because people who speak foreign languages are interesting (M = 2.63, SD = 0.63).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for individual items of FL learning motivation dimension.

We were interested in getting an additional insight into the pupils’ motivation for learning a FL with the sentence completion task ‘It’s good to know foreign languages because … ’.

As we can see from , the largest number of respondents (179) believe that it is good to know FLs because they can talk to people from other countries. It is also clear from their responses that they often have a specific person or persons in minds, such as ‘children who are not Slovenian’, ‘relatives’, or ‘mum’s colleagues’. The second most frequently cited reason, mentioned by 168 pupils, is travelling around the world or to other countries. Also here the respondents referred to specific situations, such as going on holidays, buying something or getting lost (‘you can get lost in America’, ‘you don't have to be afraid when you're in other countries’). We may conclude from these answers that they recognise the advantages of knowing FLs for travelling which is not necessarily related to their experience of visiting other countries but perceived also from a more abstract perspective as a hypothetical situation. Several pupils also mentioned getting a job, getting more friends and watching media content or listening to music. As we can see from the pupils’ responses their reasons why it is good to know FLs are often linked to a concrete situation or idea, such as watching a favourite TV programme (‘you can watch Soy Luna’), speaking a FL if you do not want others to understand you, being able to express yourself in a specific situation (‘I can apologize in a foreign language’), or being more successful (‘you can get more money’). As we can see, the results of the qualitative part of the survey partly mirror the data obtained in the quantitative part above, especially when the children pointed out talking to people from other countries and travelling as the main advantages of knowing FLs.

Table 2. Answers to sentence completion task ‘It’s good to know foreign languages because … ’

FL attitudes

The results in show that in general, children hold positive attitudes towards FLs. They report they would also like to speak other languages, not only the ones they learn at school (M = 2.73, SD = 0.56). In addition, they also express positive attitudes and interest toward FLs (M = 2.63, SD = 0.63). The results also indicate they generally enjoy English lessons (M = 2.50, SD = 0.69). However, despite the generally positive attitudes towards FLs, the relatively high scores for items ‘When I speak in foreign languages, I feel awkward and strange’ (M = 2.33, SD = 0.81) and ‘I prefer speaking in my mother tongue’ (M = 1.98, SD = 87) raise a question about the relationship between positive attitudes towards FLs on the one hand and their emotions or feelings connected with their use on the other. This suggests a certain level of FL anxiety which is often seen as the negative side of motivation. At the same time, the results of standard deviation also indicate that the negative feelings related to the actual language use should not be generalised, as the standard deviation is relatively high, which indicates a relatively wide distribution of answers.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for individual items of FL attitudes dimension.

In the qualitative part of the survey, the second sentence completion task ‘A person who knows more foreign languages is … .’ was aimed at identifying the pupils’ attitudes towards someone who speaks different FLs based on the assumption that attitudes towards the speakers of a particular language reflect the attitudes towards the language itself. Their answers fall into three major categories, those highlighting positive personal characteristics, the characteristics of a language learner and referring to a specific person.

As we can see from , the vast majority of answers reflects someone with positive personal characteristics, a person who knows more FLs is ‘cool’ and ‘smart’ but also ‘generous’ and ‘a good person’. Several respondents pointed to the characteristics of a learner – both a language learner and a learner in general, someone who ‘helps others’ or is ‘excellent at school’. The third category of responses refers to specific people, in most cases the teacher, but also other individuals, such as ‘sales person’ or ‘Justin Bieber’. In their attempt to provide a good answer, three respondents coined new Slovenian words: ‘jezikolog’ (Eng. languigist), ‘večznalec’ (Eng. more-knower), ‘več govornik’ (Eng. more-speaker). Also here we can see that the positive attitudes expressed in the qualitative part of the survey agree with the quantitative data. While most responses in this task were overtly positive, there were also a few responses in which pupils expressed their opinion that a person who knows more FLs is ‘just an ordinary man’, ‘nothing special’ (8 respondents), and one pupil wrote that this person is ‘interesting but can also be a show-off’. One of the participants completed the sentence with the word ‘Bosanjko’ (Eng. Bosnian. neg.) which can be interpreted as being overtly negative.

Table 4. Responses to the sentence completion task ‘A person who knows more foreign languages is … .’

Importance of significant others

The results in show that parents are an important significant other from the children’s perspective. They report on their parents’ positive attitudes towards knowing FLs (M = 2.80, SD = 0.49) and generally agree that their parents are happy if they hear them using a FL (M = 2.77, SD = .49). The results also indicate that children like FL teachers (M = 2.67, SD = 0.60). At the same time, they agree to a lesser extent that they sometimes talk to friends in a FL (M = 2.06, SD = 0.87) or that people who speak more languages are cool (M = 2.05, SD = 0.86). Also here the standard deviation analysis shows that the children’s opinion cannot be considered homogeneous, as their answers are widely distributed. These results should also be compared against the qualitative data above (see ) in which the respondents described a person who speaks more languages. The results showed overtly positive characteristics of such a person but also exposed the role of significant others as several respondents saw their teachers or parents as the person who speaks more FLs.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics for individual items of the dimension Perceptions of valuable others.

Multiple regression analysis

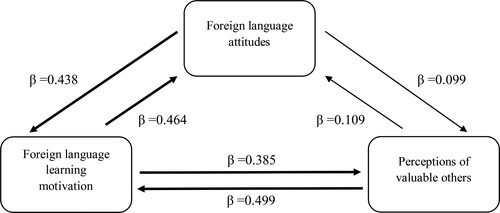

We carried out a multiple regression analysis to determine if and how the three analysed factors predict each other. The first analysis was aimed at predicting FL learning motivation based on FL attitudes and Importance of significant others. Using the stepwise method, both predictors entered the model. indicates that we found a significant regression equation (F(3.633) = 54.523, p < .000), with an R2 of .287 which led to the conclusion that FL attitudes (β = 0.438, p < .001) and Importance of significant others (β = 0.385 p < .001) significantly predict self-reported FL learning motivation.

Table 6. Summary of Multiple regression for FL attitude and Perceptions of valuable others predicting FL learning motivation.

In addition, we conducted a multiple linear regression to predict self-reported FL attitudes based on FL learning motivation and Importance of significant others. Using the stepwise method, both predictors entered the model. As we can see from , we found a significant regression equation (F(3.943) = 34.999, p < .000), with an R2 of . 353. The results indicate that FL learning motivation (β = .464, p < .001) and Importance of significant others (β = .109, p < .005) are statistically significant predictors of self-reported FL attitudes.

Table 7. Summary of Multiple regression for FL learning motivation and Perceptions of valuable others predicting FL attitude.

We also calculated a multiple linear regression to predict the Importance of significant others based on FL learning motivation and FL attitudes. Using the stepwise method, both predictors entered the model. shows that we found a significant regression equation (F(5.613) = 45,750 p < .000), with an R2 of .316. The results show that both, FL learning motivation (β = 0.499, p < .01) and FL attitudes (β = 0.099, p < .05) are statistically significant predictors of Importance of significant others.

Table 8. Summary of Multiple regression for FL learning motivation and FL attitudes predicting Perceptions of valuable others.

Based on the regression analysis, we designed a pattern of relationships between attitudes’ predictors (). As we can see, the strongest predictor is Importance of significant others which highly predicts the EL learning motivation dimension which is in turn a significant predictor for the FL attitudes dimension.

Children's perceptions of different languages

Children’s attitudes towards foreign languages, their motivation to learn them and the image they have of people who speak more foreign languages reflect their general perceptions of language diversity. One of the aims of the study was also to gain a deeper insight into the children’s perceptions of foreign languages. For this purpose, the respondents were asked two further questions: whether they could think of an interesting word in a FL and which languages they know. With respect to the first question, the results show that the vast majority of respondents (397) provided an answer in the form of one or more words in a FL, 53 provided no answer, 20 respondents answered that they did not know any interesting words, one respondent wrote ‘not yet’ and one ‘I do but I don't know how to write it down’. Of all the examples provided, the majority of the words or phrases are in the English language, followed by words in German, Spanish, and Croatian. Other languages which could be recognised in their answers are Italian, Hungarian, French, Chinese, Russian, Thai, and Arabic. In a few cases, the language was impossible to identify owing to spelling inaccuracies.

It is clear from the answers that the respondents tried to give an answer even if they did not know how to spell the words: wainahatscman (German ‘Weihnachtsmann’), bonžu (French ‘bonjour’), gracjas (Spanish ‘gracias’), činkue (Italian ‘cinque’), barčurno (Italian ‘buon giorno’), bolšit (English ‘bullshit’). A notable example are also the different spelling varieties used for the Chinese greeting ‘konnichiwa’: koniči va, keničiva, konjičiva, koonjičju va, koničiva. Some of the answers were in the form of full phrases which were a little harder to interpret, such as ha varju fajn tenkiv (How are you? Fine, thank you.). In fact, several answers provided by the respondents were not merely words but phrases or complete communication patterns, such as šta radiš (‘what are you doing’ in Croatian), Hallo, wie geht es? (‘Hello, how are you?’ in German), como teljamas (‘what's your name’ in Spanish).

A few respondents decided to add an explanation of the meaning of the word, such as muci (krava) po madžarsko (Eng. ‘muci cow in Hungarian’), po francosko pomeni wi wi ja (Eng. ‘in French wi wi means yes’), svada bi haa: tajščina dober dan (Eng. ‘svada bi haa: Thai good day’). It is also worth mentioning the answer of one of the pupils in which he/she points to the similarity in the pronunciation of the English word ‘cousin’ and the Slovene word ‘kazen’ (Eng. punishment): kazen izgovorjava za cousin (Eng. ‘kazen pronunciation for cousin’).

An important result is also the number of answers which contained examples of more than one language. Altogether 46 respondents provided words or phrases in more than one language, while in a few examples up to four languages could be identified: alfabeto, šokolade, bonžur, aloha, wi (Italian, German, French, Spanish), gracie, bonjur, danke, godina (Spanish, French, German, Croatian).

The analysis of the words provided by the respondents also shows that the words or phrases can be related to important situations in their lives or their personal experiences. This is especially evident from a number of words and phrases in Croatian which can be related to children's holiday experiences: idemo se igrati z lopto (Eng. ‘let's go play with the ball’), sunce, lopta, fudbal (Eng. ‘sun, ball, football’), može ti platiti jedno pivo (Eng. ‘he/she may pay for a beer’), jesi li dobro (Eng. ‘are you ok’), četridvadeset kuna (Eng. ‘twenty-four kuna’).

This can be related to the responses to the second question in which the pupils were asked which languages they know. As predicted, the majority of the respondents selected English (82%), followed by Croatian (61.4%), German (28.8%), Italian (24.2%), Bosnian (23.5%), Serbian (18.9%), French (14.4%), and Albanian (4.2%), while a number of other languages were mentioned in fewer cases. The result for English was expected as the majority of respondents learn English as their first FL in school. However, the fact that 61% of all students selected Croatian as the language they know is more surprising, especially considering that Croatian is not included in the primary school curriculum, not even as an elective subject. We may therefore conclude that pupils are exposed to the Croatian language in their family environment and on holidays.

Discussion and conclusion

One of the aims of the present study was to identify the respondents’ motivation for learning FLs. The results suggest that children of this age group are generally highly motivated for FL learning. We can also see that their motivation is primarily instrumental, as they have pointed out the practical aspect of language use, such as speaking with people from other countries or getting a better job. This is also reflected in the qualitative data which have shown that pupils in this age group perceive the reasons why it is good to know FLs in concrete terms, linking them to specific situations, events or ideas. On the one hand, this suggests that their perceptions are very much dependant on their experience and the context in which they have been or might be exposed to different languages, such as watching their favourite TV programme or going on holidays. This is also in line with the conclusions of several studies (Dörnyei, Citation1998; Mihaljević Djigunović, Citation2012; Noels, Citation2001) which suggest that there may be other relevant orientations not covered by the integrative/instrumental model, such as travel or friendship. On the other hand, we can see that some aspects of children’s motivation cannot be directly linked to their experience. For example, the belief that speaking FLs may mean getting a better job can be related to the strong influence of significant others, in this case most probably parents.

It is also clear from the results that children have overtly positive attitudes towards FLs which is consistent with the results of studies reported by Enever (Citation2011) and Nikolov and Mihaljević Djigunović (Citation2019). The respondents expressed their wish to learn other FLs, they find FLs interesting and enjoy FL lessons. At the same time, we can also see that some children have negative feelings (feeling awkward) when they speak in FLs which may be related to language learning anxiety. Also Mihaljević Djigunović (Citation2012) has observed that despite usually very positive attitudes, children may experience various levels of anxiety related to FL learning which may have a negative effect on their motivation. Their positive attitudes towards FLs were also reflected in their attitudes towards speakers of FLs. When asked to describe a person who knows more FLs, the vast majority of children emphasised very positive personal characteristics.

These results may be linked to the importance attributed to significant others. From the children’s perspective, the most important significant other are the parents, followed by the teachers and to a considerably lesser extent their peers which is consistent with related studies (Nikolov, Citation1999; Nikolov & Mihaljević Djigunović, Citation2019). We may conclude that with respect to attitudes towards FLs, children in this age group still largely rely on their parents’ and teachers’ opinions and beliefs. These conclusions can be compared to the results of the study conducted by Nikolov (Citation1999) according to which the teacher has a dominant influence on the pupils’ attitudes especially in the early years of language learning, while Nikolov and Mihaljević Djigunović (Citation2019) point out that parents influence pupils’ motivation indirectly, outside the classroom.

The regression analysis was conducted with the aim of identifying the most important predictors of attitudes towards FLs. An important conclusion which may be drawn from the relationships pattern which ensued from the analysis is that significant others are an important influence on the children's FL learning motivation, which in turn importantly predicts FL attitudes. What is the implication of this result? We could argue that in order to develop positive attitudes towards FLs, which are directly linked to high FL learning motivation, it is important to understand that a supportive environment (teachers, parents, and friends) plays a crucial role for the age group in question. The pattern also suggests that attitudes play an important role in building motivation, and vice versa, that motivation influences language learning attitudes. This is in line with the findings of several authors who have pointed to the complexity of the relationship between attitudes and motivation (Bratož, Citation2015; Noels, Citation2001) and the role played by other variables, such as language aptitude or language anxiety (Mihaljević Djigunović, Citation2012).

An important aim of the study was also to gain a deeper insight into the participants’ perceptions of FLs. When children were asked to write an interesting word in a FL, most of them were able to provide words or phrases in one or more languages. It is important to note that although they were asked to provide a word, a number of their answers were in the form of phrases or interaction patterns which suggests that children at this stage are focused on the meaning and communicative value of language. The words and phrases provided by the pupils show that FLs in this age group are often perceived through their experience, which is seen by Maad (Citation2016) as key in developing awareness of linguistic and cultural diversity. In addition, the question was formulated using the phrase ‘interesting word’ which was meant to reflect an attitude of curiosity about languages. This can be related to the affective domain in language awareness which foregrounds positive attitudes towards linguistic diversity (James & Garrett, Citation1992). The results of this part show that the most frequently mentioned foreign language was English which was also the language in which most interesting words were provided. At the same time, while Spanish was not among the most frequently mentioned foreign languages, it was the third most frequently mentioned language in the pool of interesting words. This foregrounds the role of curiosity in developing linguistic awareness and positive attitudes towards language diversity. Moreover, as discussed by Beacco and Byram (Citation2007), curiosity is an important element in developing people’s own linguistic repertoires.

In addition, several examples provided by the children reflect an emergent metalinguistic awareness. As emphasised by Berry (Citation2014), metalanguage is a much more general concept which encompasses all the languages used to talk about language, not just technical linguistic terminology.

Finally, a number of pupils provided an answer even if they did not know how to spell the words. We may assume that they did not bother about spelling if the word they thought of seemed interesting to them. We would therefore like to argue that by including the children’s perceptions of FLs, which reflect their age-specific understandings of linguistic meaning and form, we are presented with the challenge of widening the scope of the concept of plurilingualism and the idea of linguistic repertoires.

In conclusion, while some valuable insights have been provided, there are some clear limitations to this study. An important drawback is related to the fact that we limited our scope to analysing attitudes towards and perceptions of FLs, thus excluding other relevant language varieties. In order to gain a more comprehensive picture of the ways children of this age perceive not just FLs but linguistic diversity more generally, we would need to include other languages (home languages, minority languages, dialects, etc.) the children are exposed to. Also, despite a large and representative sample, the researchers had only a limited knowledge of the children’s language background. A more extensive account of the participants’ linguistic repertoires would enable a broader and more in-dept interpretation of the results gained.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

References

- Aboud, F. E. (1976). Social developmental aspects of language. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 9(3-4), 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351817609370427

- Beacco, J. C., & Byram, M. (2007). From linguistic diversity to plurilingual education. Guide for the development of language education policies in Europe. Council of Europe.

- Bell, A. (2007). Designing and testing questionnaires for children. Journal of Research in Nursing, 12(5), 461–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987107079616

- Berry, R. (2014). Investigating language awareness: The role of terminology. In A. Łyda & K. Szcześniak (Eds.), Awareness in action (pp. 21–33). Springer International Publishing.

- Borgers, N., De Leeuw, E., & Hox, J. (2000). Children as respondents in survey research: Cognitive development and response quality. Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique, 66(1), 60–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/075910630006600106

- Bratož, S. (2015). Pre-service teachers’ attitude towards learning and teaching English to young learners. Revija za elementarno izobraževanje, 8(1/2), 181–198. https://journals.um.si/index.php/education/article/view/423

- Bratož, S., Pirih, A., & Štemberger, T. (2021). Identifying children's attitudes towards languages: Construction and validation of the LANGattMini scale. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 42(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2019.1684501

- Candelier, M., Daryai-Hansen, P., & Schröder-Sura, A. (2012). The framework of reference for pluralistic approaches to languages and cultures–a complement to the CEFR to develop plurilingual and intercultural competences. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 6(3), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2012.725252

- Candelier, M., & Kervran, M. (2018). 1997-2017: Twenty years of innovation and research about awakening to languages-Evlang Heritage. International Journal of Bias, Identity and Diversities in Education (IJBIDE), 3(1), 10–21. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJBIDE.2018010102

- Carbonara, V., & Scibetta, A. (2020). Integrating translanguaging pedagogy into Italian primary schools: Implications for language practices and children's empowerment. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 1–21. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1742648.

- Carreira, J. M. (2006). Motivation for learning English as a foreign language in Japanese elementary schools. JALT Journal, 28(2), 135–157. https://doi.org/10.37546/JALTJJ28.2-2

- Cots, J. M. (2008). Knowledge about language in the mother tongue and foreign language curricula. In N. H. Hornberger (Ed.), Encyclopedia of language and education (pp. 15–30). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-30424-3_136

- Council of Europe. (2000). Linguistic diversity for democratic citizenship in Europe. Proceedings. Council of Europe Publishing.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Sage.

- Darquennes, J. (2017). Language awareness and minority languages. In J. Cenoz, D. Gorter, & S. May (Eds.), Language awareness and multilingualism (pp. 297–308). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02240-6_19

- De Leeuw, E. (2011). Improving data quality when surveying children and adolescents: Cognitive and social development and its role in questionnaire construction and pretesting (Report prepared for the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Finland).

- Dörnyei, Z. (1998). Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Language Teaching, 31(03), 117–135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026144480001315X

- Dörnyei, Z., Csizér, K., & Németh, N. (2006). Motivation, language attitudes and globalisation: A Hungarian perspective. Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781853598876

- Dörnyei, Z., Durow, V., & Zahran, K. (2004). Individual differences and their effects on formulaic sequence acquisition. Formulaic Sequences, 9, 87–106. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.9.06dor

- Ehrman, M. E., Leaver, B. L., & Oxford, R. L. (2003). A brief overview of individual differences in second language learning. System, 31(3), 313–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(03)00045-9

- Enever, J. (2011). ELLie: Early language learning in Europe:[evidence from the ELLiE study]. British Council.

- Fidler, S. (2006). Awakening to languages in primary school. ELT Journal, 60(4), 346–354. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccl025

- Finkbeiner, C., & White, J. (2017). Language awareness and multilingualism: A historical overview. In J. Cenoz, D. Gorter, & S. May (Eds.), Language awareness and multilingualism. Encyclopedia of language and education (3rd ed.) (pp. 3–17). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02240-6_1

- Fuchs, M. (2005). Children and adolescents as respondents. Experiments on question order, response order, scale effects and the effect of numeric values associated with response options. Journal of Official Statistics, 21(4), 701–725.

- García, O., & Otheguy, R. (2020). Plurilingualism and translanguaging: Commonalities and divergences. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23(1), 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1598932

- Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning. The role of attitudes and motivation. Edward Arnold.

- Garrett, P., Coupland, N., & Williams, A. (2003). Investigating language attitudes: Social meanings of dialect, ethnicity and performance. University of Wales Press.

- James, C., & Garrett, P. (1992). Language awareness in the classroom. Longman.

- Kuchah, K., & Pinter, A. (2012). Was this an interview? Breaking the power barrier in adult-child interviews in an African context. Issues in Educational Research, 22(3), 283–297.

- Little, D., Leung, C., & Van Avermaet, P. (2013). Managing diversity in education: Languages, policies, pedagogies (Vol. 33). Multilingual matters.

- Maad, M. R. B. (2016). Awakening young children to foreign languages: Openness to diversity highlighted. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 29(3), 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2016.1184679

- Masgoret, A.-M., & Gardner, R. C. (2003). Attitudes, motivation, and second language learning: A meta–analysis of studies conducted by gardner and associates. Language Learning, 53(1), 123–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9922.00212

- Masgoret, A. M., Bernaus, M., & Gardner, R. C. (2001). Examining the role of attitudes and motivation outside of the formal classroom: A test of the miniAMTB for children. In Z. Dörnyei, & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition (pp. 281–295). University of Hawai’i Press.

- Mercer, G. V. (1975). The development of children’s ability to discriminate between languages and varieties of the same language [Unpublished master's thesis]. McGill University.

- Mihaljević Djigunović, J. (2012). Attitudes and motivation in early foreign language learning. CEPS Journal, 2(3), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.26529/cepsj.347

- Mihaljević Djigunović, J., & Bagarić, V. (2007). A comparative study of attitudes and motivation of Croatian. Studia Romanica et Anglica Zagrabiensia: Revue publiée par les Sections romane, italienne et anglaise de la Faculté des Lettres de l’Université de Zagreb, 52, 259–281.

- Mihaljević Djigunović, J., & Nikolov, M. (2019). Motivation of young learners of foreign languages. In M. Lamb, K. Csizér, A. Henry, & S. Ryan (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of motivation for language learning (pp. 515–533). Springer.

- Nagy, K. (2009). What primary school pupils think about learning English as a foreign language. In M. Nikolov (Ed.), Early learning of modern foreign languages: Processes and outcomes (pp. 229–242). Multilingual Matters.

- Nikolov, M. (1999). ‘Why do you learn English?’ ‘because the teacher is short.’ A study of Hungarian children’s foreign language learning motivation. Language Teaching Research, 3(1), 33–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/136216889900300103

- Nikolov, M. (2009). Early learning of modern foreign languages: Processes and outcomes. Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847691477

- Nikolov, M., & Mihaljević Djigunović, J. (2019). Teaching young language learners. In X. Gao (Ed.), Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 1–23). Springer.

- Noels, K. A. (2001). New orientations in language learning motivation: Towards a model of intrinsic, extrinsic, and integrative orientations and motivation. In Z. Dörnyei & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition (pp. 43–68). Natl Foreign Lg Resource Ctr.

- Oliveira, A. L., & Ançã, M. H. (2009). ‘I speak five languages’: Fostering plurilingual competence through language awareness. Language Awareness, 18(3-4), 403–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410903197355

- Peace-Hughes, T., de Lima, P., Cohen, B., Jamieson, L., Tisdall, E. K. M., & Sorace, A. (2021). What do children think of their own bilingualism? Exploring bilingual children’s attitudes and perceptions. International Journal of Bilingualism, 25(5), 1183–1199. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069211000853

- Prasad, G. (2020). ‘How does it look and feel to be plurilingual?’: Analysing children's representations of plurilingualism through collage. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23(8), 902–924. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1420033

- Read, J., & Fine, K. (2005). Using survey methods for design and evaluation in child computer interaction. Workshop on Child Computer Interaction: Methodological Research at Interact.

- Sayers, D., & Láncos, P. L. (2017). (Re) defining linguistic diversity: What is being protected in European language policy? SKY Journal of Linguistics, 30, 35–73.

- Svalberg, A. M. (2007). Language awareness and language learning. Language Teaching, 40(4), 287–308. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444807004491

- Takada, T. (2003). Learner characteristics of early starters and late starters of English language learning: Anxiety, motivation, and aptitude. JALT Journal, 25(1), 5–30. https://doi.org/10.37546/JALTJJ25.1-1

- Wagner, C. J. (2020). Multilingualism and Reading identities in prekindergarten: Young children connecting Reading, language, and the self. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 1–16. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2020.1810046

- Žefran, M. (2015). Students’ attitudes towards their EFL lessons and teachers. Journal of Elementary Education, 8(1/2), 167–180. https://journals.um.si/index.php/education/article/view/422