ABSTRACT

This special issue consists of five original research papers from four European countries. By applying different methodologies (qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods), the contributions aim to better understand teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism in a time of increasingly globalised societies and intensified migration flows. The studies cover all educational stages and include pre-service as well as in-service teachers, and teacher educators. Both individual and collective beliefs are considered. While two of the studies are cross-sectional, the other three apply a pre-post study design in order to investigate whether teachers’ beliefs can be influenced through adequate learning opportunities. The special issue is wrapped up by a commentary piece that links the findings and issues raised by the individual papers and addresses four pressing matters which should be considered to advance further research on teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism. In this editorial, we briefly introduce the concept of teachers’ beliefs and explain its relevance for teaching and learning in multilingual settings. Based on an ongoing review study, we provide a summary of the most commonly used methodologies in research on teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism. We conclude with a summary of the five original papers as well as the commentary piece in this special issue.

1. Introduction

Ever more globalised societies and migration flows have led to a growing sociolinguistic complexity and diversification of student populations around the world, which has intensified the challenge of dealing with multilingualism in education. Here, ‘the deep-seated habit of assuming monolingualism as the norm of a nation’ (Gogolin, Citation1997, p. 41), has increasingly been described as a major reason for linguistic injustice through an educational system’s ‘latent function […] to instill linguistic insecurity, to discriminate linguistically, to channel children in ways that have an integral linguistic component, while appearing open and fair to all’ (Hymes, Citation1996, p. 84). In fact, the needs of linguistically and culturally diverse pupils, often termed multilingual learners (MLLs) or English language learners (ELLs) in English-dominant contexts, are not to be neglected when striving for social justice in education. Because their language practices are often marginalised and portrayed as deviations from the local norm or standard (Flores & Rosa, Citation2015), these students have also been described as ‘language-minoritized learners’. As a result, the quality of their education might be jeopardised (Piller, Citation2016) or they might be disadvantaged due to the monolingual norm that still serves ‘as a yardstick for measuring learning progression linearly’ (Barros et al., Citation2021, p. 250). Not least since the so-called multilingual turn (Conteh & Meier, Citation2014; May, Citation2014), the awareness of multilingualism as an individual and social practice on the one hand, and the pivotal issue needed to be addressed in dealing with discrimination and inequality associated with language in education (Salzburg Global Seminar, Citation2018) on the other hand, has been raised immensely.

Because every subject is understood to be a language subject, in the sense that language does not necessarily need to be the (overt) purpose of the lesson, but simply the medium of instruction, the enactment of educational language policies is a ubiquitous aspect of every teacher’s daily work. As key policy arbiters (Johnson, Citation2013; Menken & García, Citation2010), teachers dynamically manage and plan language use in the classroom through their professional teaching practices (Lo Bianco, Citation2010). Even though more research is needed to better understand how, it is relatively uncontested in research that what teachers believe, informs their decision-making and drives their professional practice (Bandura, Citation1986; Pajares, Citation1992; Richardson, Citation1996; Skott, Citation2014). Consequently, teachers’ beliefs have been addressed by educational researchers for more than half a century (Gill & Fives, Citation2014).

The concept of teachers’ beliefs has been used and defined in a multitude of ways (Song, Citation2015). For this special issue, we apply a rather broad definition that includes ideologies, attitudes, views, perspectives, perceptions, dispositions, judgements, conceptions, or preconceptions. This superordinate conceptualisation serves our intention to discuss the concept more holistically (Borg, Citation2019) and allowed us to invite contributors from various contexts and traditions with different theoretical concepts. What seems to be the common denominator of all these concepts, however, is the fact that they are subjective. In other words, individuals, such as teachers, consider them to be true (Richardson, Citation1996), even if they are objectively seen as false. Nevertheless, studies in a recent special issue on socially just plurilingual education in Europe (Erling & Moore, Citation2021), suggested that increased awareness of their own beliefs allows teachers to be more reflective and prone to act toward educational equity for linguistically and culturally diverse pupils.

Teacher education, be it pre-service or in-service, is an excellent context to critically discuss beliefs and support educators’ awareness and ability to review and revise their beliefs and to potentially act in alignment with them (Borg, Citation2011). The goal to prepare teachers to work with multilingual students is not novel (Lucas & Villegas, Citation2013; Wernicke et al., Citation2021). Several studies applying a pre-post research design illustrate the welcoming effects of initial teacher training concerning teachers’ positive beliefs about multilingualism (see, e.g. Portolés & Martí, Citation2020; Schroedler & Fischer, Citation2020). Others ask for more structured opportunities for professional development in new teachers’ introduction year (Cajkler & Hall, Citation2012) or during a later stage in their career (Lundberg, Citation2019b). On the one hand, valuable time during teacher education should be spent on critically reflecting individual beliefs (Fischer & Lahmann, Citation2020) or collective beliefs (Camenzuli et al., Citation2022) about multilingualism. On the other hand, teachers need to receive hands-on support concerning methods and tools to use with linguistically diverse student groups. The call for more teacher awareness regarding the specific needs of multilingual students, which will eventually support teachers’ more complex understanding of multilingualism as a concept that goes beyond ‘simply positive or negative’ (Lundberg, Citation2019a) has been voiced clearly in recent research. Furthermore, teacher educators are demanded to more intensively collaborate with parents and community members (Back, Citation2020) to better illustrate the importance of a holistic understanding of the issue at hand. What potentially has not received sufficient attention is a focus on teachers’ own multilingualism (Calafato, Citation2022), investigated, for instance, through visual narratives (Melo-Pfeifer & Chik, Citation2022). This is particularly important as empirical research points to multilingual teachers showing more positive beliefs about multilingualism and integrating it into their teaching practices than monolinguals (Brandt, Citation2021; Lorenz et al., Citation2021).

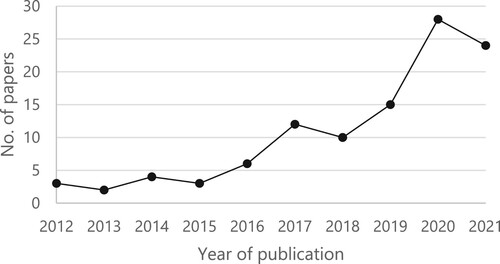

Our ongoing work to systematically review research on teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism shows that teachers’ beliefs in the context of multilingualism have received increasing attention from empirical research in the last 10 years: While a computerised search of major databases (ScienceDirect, ERIC, APA PsychInfo, EBSCOhost) only returned three peer-reviewed journal articles on the topic for the year 2012, almost 30 papers that were published in 2020 could be included in the review (see ).

Figure 1. Number of peer-reviewed journal articles on teacher beliefs about multilingualism by year of publication (n = 107).

At this stage, a total of 107 journal articles have been selected for data extraction – which surely is an underestimation of published work on the matter as we only included papers that were written in English. Even though the majority of papers represented research from the global North (especially the United States, United Kingdom, Spain, and Germany), we found a considerable amount of studies from the global South (e.g. Kenya, South Africa, the Philippines, and Hong Kong). Teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism, therefore, are by no means a research area that is restricted to Western countries. The extraction phase of the systematic review has not been completed yet, but so far, we have made the following observations: Most of the studies in the ongoing review study have a cross-sectional design. Semi-structured interviews seem to be the most prominent among qualitative studies, while the use of questionnaires seems to be the method of choice in quantitative research. The use of alternative methods to assess (pre-service) teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism, e.g. Q-methodology which is particularly suitable for a sociocultural approach to teachers’ beliefs (Camenzuli et al., Citation2022), or mixed-method approaches which may help to gain a better and deeper understanding of what educators believe about multilingualism, still seem to be scarce. Qualitative studies tend to operate with extremely small (convenience) samples. Sampling procedures, sample composition and size are not necessarily discussed in the papers we have analysed so far. In quantitative studies, beliefs are often assessed with Likert scales and thus face the problem of how to deal with socially desirable answering tendencies. The use of advanced statistical methods of data analysis which are commonly used in sociological and psychological research, e.g. multilevel modelling for repeated measures (also known as linear mixed models) for pre-post data, does not seem to have become established in research on teacher beliefs about multilingualism yet. Moreover, most of the studies focus on the beliefs of individuals. Despite awareness about local school traditions and peers playing a role in the formation and development, especially of novice teachers’ beliefs, studies on collective teacher beliefs (England, Citation2017) are still rare. The question of whether and how teacher beliefs are modifiable as well as the relationship between beliefs and actual practice remains a desideratum for empirical research. This special issue aims to tackle some of the described issues.

2. This special issue

2.1. Purpose and aims

The fruitful discussion during a symposium on Researching Teacher Beliefs on Multilingualism at the online European Conference for Educational Research (ECER) in 2021, focusing on the difficulty to investigate beliefs and the often too generally held implications for teacher education, led to the present special issue. The purpose of this editorial introduction, the five research papers, and the concluding commentary piece is to gain a better understanding of what teachers in various contexts think and believe about multilingualism, in order to do justice to the increasing linguistic diversity in educational settings. The special issue’s contributors discuss the significance, opportunities, and challenges of their novel findings for teacher education in and beyond their local context(s). With a focus on different methodological approaches, this special issue further contributes to the discussion regarding the potential need for methodological advancements in the field.

2.2. Overview of the contributions

The five original contributions in this special issue stem from four different European countries (Austria, Germany, Luxembourg, and Sweden). The contributions cover a wide range of educational stages: early childhood, primary, secondary and tertiary education. They include pre-service as well as in-service teachers, and teacher educators. The research teams applied various approaches, ranging from quantitative surveys over qualitative group discussions and video observations to mixed-method approaches. While two of the studies are cross-sectional, the other three applied a pre-post study design in order to evaluate whether the participants’ beliefs changed through the participation in learning opportunities.

The first article by Schroedler, Rosner-Blumenthal, and Böning reports findings from a study among pre-service teachers in Germany and applies a mixed-method pre-post study design, in order to investigate whether professional beliefs about multilingualism can change over the course of one semester. The beliefs of 259 pre-service (middle school) teachers in North Rhine-Westphalia were assessed with a quantitative survey (three Likert scales) before and after a compulsory module on multilingualism. The instrument being used covered three dimensions of teacher beliefs about multilingualism: (i) epistemological beliefs about multilingual language use in the home of learners, (ii) beliefs about teachers and their responsibility for language support in the teaching process, and (iii) beliefs about teaching and multilingualism in the teaching and learning process. In addition, the authors investigated the relationship between background variables and the pre-service teachers’ beliefs. Qualitative interviews with five participants then helped to observe deeper facets of the beliefs. The study shows that learning opportunities can indeed trigger a change in pre-service teachers’ professional beliefs: the participants’ beliefs about multilingualism were significantly more positive after they had attended the module than before. Overall, being female, the number of semesters studied, studying a language subject, and being multilingual is positively and significantly correlated with more positive beliefs about multilingualism. On closer inspection, however, multilingual pre-service teachers seem to recognise the responsibility of supporting multilingual learners to a lower extent than monolinguals. The interview data support the observation that pre-service teachers’ generally feel responsible to support multilingual learners. However, it becomes evident that the participants are insecure about how to translate their positive attitudes towards multilingual learners into practice.

Drawing on findings from three group discussions (n = 4–7) and the sociologically informed documentary method, Lengyel and Salem investigate team beliefs on multilingualism in early childhood education and care facilities in Germany. The paper adds the concept of shared beliefs to what is often investigated on an individual level. Data collection took place in ECEC facilities in different areas of the federal state of Hamburg. Two childcare centres with a very high proportion of multilingual children and one with a comparatively low percentage were selected for the study. The educators were asked to discuss a multi-layered prompt in order to thematically frame the discussion and to help the team members submerge into an imaginary but typical setting. The discussions were recorded. The researchers did not participate in the discussion to avoid impeding or influencing the discussion. The analyses of the discussion transcripts show that German was the organisational language in all of the participating ECEC facilities, i.e. the focus was set on the children’s German skills. Organisational policies for dealing with the children’s home languages were not in place. Even though the educators had developed pedagogical practices that included the children’s home languages, they oriented to the institutional norm which attributes the greatest importance to the acquisition and the development of the German language. There were facility-specific differences in the team member’s collective beliefs about the inclusion of the children’s home languages into their pedagogical practices. However, due to the lack of official guidelines, the team beliefs in all facilities were determined by arbitrariness, as well as the preferences, language skills, and the knowledge about multilingualism and language education of the educators.

Aleksić and Bebić-Crestany investigated the beliefs of 40 Luxembourgish preschool teachers about children’s home languages and the use of translanguaging practices in the classroom. Similar to the study by Schroedler et al., the authors collected data before and after the teachers had participated in a professional development course on translanguaging pedagogy. The use of questionnaires (three Likert-scales), focus group discussions and classroom observations produced a rich data set. The analysis of the questionnaire data shows a significant positive development of the preschool teachers’ beliefs about children’s multilingualism, their home languages, and translanguaging over the course of six months. The focus group interviews provided a more detailed, but mixed pictured concerning the teachers’ beliefs about translanguaging: Before participating in the PD, very few teachers expressed either a clear monolingual stance (Luxemburgish-only classroom) or a true translanguaging stance (free use of the entire linguistic repertoire in class). The majority of the participants seemed to acknowledge that home language use in class is generally beneficial for the children’s progress and well-being, but expressed the fear that it could hinder their development in Luxembourgish. While the beliefs of teachers with a monolingual stance could not be changed through the PD, some of the teachers who did not have a clear stance in the beginning reported to have changed their view on multilingualism in the classroom. A comparison of survey, interview and classroom observation data reveals that (i) results differ depending on the method of data collection, and (ii) that the expressed beliefs are not necessarily translated or even contradicted in teaching practice.

Results from an interview study with teacher educators (n = 5), in-service (n = 5) as well as pre-service teachers (n = 8) in Sweden are presented by Paulsrud, Juvonen and Schalley. The authors carried out semi-structured interviews (individually and in groups) in order to (i) explore the participants’ attitudes and beliefs about multilingualism, and (ii) to identify similarities and differences in the expressed attitudes and beliefs between the different groups of stakeholders. The authors differentiate between educators’ attitudes and beliefs about multilingualism: Attitudes are defined as opinions and evaluations about the general value of multilingualism, linguistic diversity in the classroom, and the role of linguistic resources in education; beliefs, on the contrary, are being understood as the educators’ views about multilingualism in relation to learning. Qualitative content analysis was applied to analyse the transcripts of the recorded interviews. The study finds that the participating in-service teachers’ attitudes and beliefs about multilingualism were generally more positive than those of the teacher educators who consistently expressed more negative than positive attitudes and beliefs. Both groups believed that the majority language Swedish was the only legitimate language for learning in teacher education and in school, but in-service teachers viewed the pupil’s heritage languages as a vehicle in the process of learning the majority language. In comparison to the other two groups, pre-service teachers’ attitudes and beliefs about multilingualism were less pronounced, which may (at least partly) be due to their limited experience with linguistically diverse learners and the lack of learning opportunities in the area of multilingualism during the course of their university studies.

Finally, Döll and Guldenschuh examine the development of deficit perspectives on multilingual students among pre-service teachers (primary school bound) in Austria. The authors collected qualitative as well as quantitative survey data concerning the participants beliefs about and experiences with multilingual learners and (inner) multilingualism, and investigated whether the beliefs of two cohorts if pre-service teachers changed over the course of an obligatory two-semester university module on migration- and multilingualism-related topics. A pre-post comparison of the quantitative (Likert-scale) data of the first cohort of the study (n = 40) shows that the participating pre-service teachers’ moderate deficit perspectives towards multilingual students at the beginning of the module did not change significantly over the course of two semesters. As a consequence, the content of the teaching module was modified. In addition, the original scale for measuring deficit perspectives towards multilingualism was adapted and expanded as it had not met the expected quality (in terms of reliability) when used with the first cohort. The final scale was designed to measure (i) beliefs about multilingual children in general, and (ii) beliefs about teaching multilingual pupils. The second cohorts’ (n = 61) perspectives on (teaching) multilingual learners were initially also rather negative, but changed significantly into a positive direction after two semesters. The study also explores the relationship between the pre-service teachers’ background characteristics and their beliefs about multilingualism: While the language background (multilingual vs. monolingual) of the students did not have an effect on the pre-service teacher’s beliefs, the future teachers’ age was significantly and positively correlated with their beliefs.

3. Conclusion

In order to wrap up this special issue and to link the findings and issues raised by the individual papers, a commentary authored by Chik and Melo-Pfeiffer summarises the key ideas emerging from this special issue (concerning the settings, the samples and the methodologies of the different studies), and highlights the main findings of the five contributions by identifying similarities and differences between the studies. The two authors address four pressing matters they think need to be considered in order to advance further research on teacher beliefs about multilingualism: The first call they make is concerned with methodologies used to investigate teacher beliefs about multilingualism. As beliefs are not directly observable, their assessment usually relies on the interpretation of observations, spoken/written discourse, and/or questionnaire data – and therefore on words. The authors recommend the use of visual narratives which may be less prone to social desirability, could flatten hierarchical relations in a research situation, and potentially lead educators to express their beliefs more genuinely than otherwise. The authors criticise that research on teacher beliefs on multilingualism often adopts a Eurocentric perspective: Typically, researchers from the global North are engaged in the investigation of the beliefs of educators in the global North about the multilingualism of individuals coming from the global South. Their second call, therefore, is to broaden the current perspective by including and embracing the views of educators from the global South in research on teachers’ beliefs, and to engage in more inclusive ways of thinking about multilingualism. It is further argued that the pronounced focus on multilingualism and multilinguals in research on teacher beliefs might – inadvertently – contribute to multilingualism being marked, and as being deviant from the norm. They suggest a change of perspective which includes the assessment of teacher beliefs about (language-related) learning difficulties of monolingual pupils and the examination of the perspectives of multilinguals on monolingualism. Last but not least, the authors point out that beliefs about multilingualism are not only determined by linguistic categories, but that languages and multilingual repertoires are associated with different social, economic as well as political status, religious and ethnic identities, worldviews, and educational trajectories. They therefore call for intersectional perspectives to be considered, and raciolinguistic approaches to be included in the study of teacher beliefs about multilingualism.

As the present special issue was focusing on teachers’ beliefs and not necessarily on practice, we would like to close this introduction with an additional call for more research investigating how teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism and teachers’ practices dynamically interact and mutually inform each other. In addition, to create sustainable educational equity for linguistically and culturally diverse pupils, future research should be longitudinal.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all authors for their contributions to this special issue. We are grateful to the reviewers, who have further increased the quality of this special issue.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Back, M. (2020). ‘It Is a Village’: translanguaging pedagogies and collective responsibility in a rural school district. TESOL Quarterly, 54(4), 900–924. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.562

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

- Barros, S., Domke, L. M., Symons, C., & Ponzio, C. (2021). Challenging monolingual ways of looking at multilingualism: insights for curriculum development in teacher preparation. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 20(4), 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2020.1753196

- Borg, S. (2011). The impact of in-service teacher education on language teachers’ beliefs. System, 39(3), 370–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2011.07.009

- Borg, S. (2019). Language teacher cognition: Perspectives and debates. In G. Xuesong (Ed.), Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 1–23). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58542-0_59-2

- Brandt, H. (2021). Sprachliche Heterogenität im gesellschaftswissenschaftlichen Unterricht: Herangehensweisen und Überzeugungen von Lehrkräften in der Sekundarstufe I (Vol. 25).

- Cajkler, W., & Hall, B. (2012). Multilingual primary classrooms: an investigation of first year teachers’ learning and responsive teaching. European Journal of Teacher Education, 35(2), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2011.643402

- Calafato, R. (2022). Fidelity to participants when researching multilingual language teachers: A systematic review. Review of Educational Research, 10(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3344

- Camenzuli, R., Lundberg, A., & Gauci, P. (2022). Collective teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism in Maltese primary education. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2022.2114787

- Conteh, J., & Meier, G., eds. (2014). The multilingual turn in languages education: Opportunities and challenges. Multilingual Matters.

- England, N. (2017). Developing an interpretation of collective beliefs in language teacher cognition research. TESOL Quarterly, 51(1), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.334

- Erling, E. J., & Moore, E. (2021). Socially just plurilingual education in Europe: shifting subjectivities and practices through research and action. International Journal of Multilingualism, 18(4), 523–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2021.1913171

- Fischer, N., & Lahmann, C. (2020). Pre-service teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism in school: an evaluation of a course concept for introducing linguistically responsive teaching. Language Awareness, 29(2), 114–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2020.1737706

- Flores, N., & Rosa, J. (2015). Undoing appropriateness: raciolinguistic ideologies and language diversity in education. Harvard Educational Review, 85(2), 149–171. https://doi.org/10.17763/0017-8055.85.2.149

- Gill, M. G., & Fives, H. (2014). Introduction. In H. Fives & M. G. Gill (Eds.), International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs (pp. 1–10). Routledge.

- Gogolin, I. (1997). The ‘monolingual habitus’ as the common feature in teaching in the language of the majority in different countries. Per Linguam: A Journal of Language Learning, 13(2), 38–49. https://doi.org/10.5785/13-2-187

- Hymes, D. (1996). Ethnography, linguistics, narrative inequality: Toward an understanding of voice. Taylor & Francis.

- Johnson, D. C. (2013). Language policy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lo Bianco, J. (2010). Language policy and planning. In N. H. Hornberger & S. L. McKay (Eds.), Sociolinguistics and language education (pp. 143–176). Multilingual Matters.

- Lorenz, E., Krulatz, A., & Torgersen, E. N. (2021). Embracing linguistic and cultural diversity in multilingual EAL classrooms: The impact of professional development on teacher beliefs and practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105, Article 103428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103428

- Lucas, T., & Villegas, A. M. (2013). Preparing linguistically responsive teachers: laying the foundation in preservice teacher education. Theory Into Practice, 52(2), 98–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2013.770327

- Lundberg, A. (2019a). Teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism: Findings from Q method research. Current Issues in Language Planning, 20(3), 266–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2018.1495373

- Lundberg, A. (2019b). Teachers’ viewpoints about an educational reform concerning multilingualism in German-speaking Switzerland. Learning and Instruction, 64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101244

- May, S.2014). The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL, and bilingual education. Taylor and Francis.

- Melo-Pfeifer, S., & Chik, A. (2022). Multimodal linguistic biographies of prospective foreign language teachers in Germany: Reconstructing beliefs about languages and multilingual language learning in initial teacher education. International Journal of Multilingualism, 19(4), 499–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2020.1753748

- Menken, K., & García, O. (2010). Negotiating language policies in schools: Educators as policymakers. Routledge.

- Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62(3), 307–332. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543062003307

- Piller, I. (2016). Linguistic diversity in education. In I. Piller (Ed.), Linguistic diversity and social justice: An introduction to applied sociolinguistics (pp. 98–129). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199937240.003.0005

- Portolés, L., & Martí, O. (2020). Teachers’ beliefs about multilingual pedagogies and the role of initial training. International Journal of Multilingualism, 17(2), 248–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2018.1515206

- Richardson, V. (1996). The role of attitudes and beliefs in learning to teach. In J. Sikula (Ed.), Handbook of research on teacher education (2nd ed., pp. 102–119). Macmillan.

- Salzburg Global Seminar. (2018). The Salzburg statement for a multilingual world. Retrieved February 21, 2020 from https://www.salzburgglobal.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Documents/2010-2019/2017/Session_586/EN_SalzburgGlobal_Statement_586_-_Multilingual_World_English.pdf

- Schroedler, T., & Fischer, N. (2020). The role of beliefs in teacher professionalisation for multilingual classroom settings. European Journal of Applied Linguistics, 8(1), 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1515/eujal-2019-0040

- Skott, J. (2014). The promises, problems, and prospects of research on teachers’ beliefs. In H. Fives & M. G. Gill (Eds.), International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs (pp. 13–30). Routledge.

- Song, S. Y. (2015). Teachers’ beliefs about language learning and teaching. In M. Bigelow & J. Ennser-Kananen (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of educational linguistics (pp. 263–275). Routledge.

- Wernicke, M., Hammer, S., Hansen, A., & Schroedler, T., eds. (2021). Preparing teachers to work with multilingual learners. Multilingual Matters.