ABSTRACT

This article critically examines the discourses concerning historical and transnational linguistic and cultural diversity in the semiotic landscape of a new teacher education building in Norway. In 2020, this building, housing the Department of Education, opened at UiT The Arctic University of Norway, in the city of Tromsø. Designing, constructing, and decorating a new building for a national teacher education was taken as an opportunity to reflect on and negotiate the institution’s role in relevant contemporary, as well as historical, educational discourses and to mark a current standpoint. Taking a nexus analytical approach, we analyse how linguistic and cultural diversity are represented in the department’s public space and how this is interwoven with the construction of the institution’s position in a multilingual and multicultural environment. Our analysis shows that this diversity is constructed through various contrasts. Sámi identities and regional roots of knowledge are emphasised in the official part of the semiotic landscape – framed as learnings from diversity. However, by analysing meta-sociolinguistic discourses about diversity, we show that this is accompanied by the erasure of other aspects of linguistic and cultural diversity, in particular Kven culture and identity, transnational diversity, and children and their lifeworld.

1. Introduction

This article is a critical examination of the discourses concerning historical and transnational linguistic and cultural diversity in the semiotic landscape of a new teacher education building in Norway. In 2020, a new building for the Department of Education opened at UiT – The Arctic University of Norway (UiT), in the city of Tromsø. The building houses teacher training and education programmes, including a three-year bachelor programme in Early Childhood Teacher Education (ECTE). Designing, constructing, and decorating a new building for a national teacher education programme was taken as an opportunity to reflect on and negotiate the institution’s role in contemporary and historical educational discourses and to mark a current standpoint. In this article, we focus on the artwork on display to construct a view of diversity and to position the institution in linguistically and culturally diverse surroundings.

Located in the North of Norway, Tromsø is geographically peripheral to more central parts of Norway and Europe. However, following Pietikäinen et al. (Citation2016) centre-periphery relations are not static. Tromsø’s linguistic and cultural diversity is influenced by global scale processes, such as urbanisation, transnational mobility (including tourism, work and study migration, and refugee resettlement), and the ethnopolitical mobilisation of Indigenous peoples and national minorities. Tromsø is therefore also a centre where people from the region, other parts of Norway and the rest of the world meet. There is growing recognition of the Indigenous Sámi people and the national minorities of Norway, such as the Kven/Norwegian Finns, who have historical roots in Tromsø and the surrounding region. Responding to these processes, ECTE in Tromsø and in Norway in general are allocated responsibility for educating new Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) teachers for a changing world and a future characterised by linguistic and cultural diversity (Forskrift om rammeplan for barnehagelærerutdanning, Citation2012). A central task for ECEC teachers is to support the language development of all mono- and multilingual children and to ‘help ensure that linguistic diversity becomes an enrichment for the entire group of children’ (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, Citation2017, p. 23). Simultaneously, ECTE is important for enacting state policies and values, with respect for, for example, democracy, language, culture, social justice, and sustainability.

Higher education institutions like UiT are social and cultural arenas for implementing politics for future knowledge and competences, including the tasks described above. Therefore, like kindergartens (e.g. Pesch et al., Citation2021; Straszer & Kroik, Citation2021) and schools (e.g. Androutsopoulos & Kuhlee, Citation2021; Sollid, Citation2019; Szabó, Citation2015), the educational spaces of higher education institutions are interesting sites for analysing circulating educational discourses on language and culture. Brown (Citation2012, p. 282) refers to educational spaces as arenas ‘where place and text, both written (graphic) and oral, constitute, reproduce, and transform language ideologies’. In this article, we use the term semiotic landscape, as the focus of the analysis is on curated artwork and its representation in physical space. We also highlight that discourses in place (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003; Citation2004) reside in the interplay between artefacts, visual discourses, spatial practices and the historical dimensions of the place (cf. Blommaert, Citation2013).

The new building is owned by the Norwegian state, through the government’s building commissioner and property manager. It is used by UiT, mainly by the Department of Education. KORO (Kunst i det offentlige rom – ‘Art in public space’), Norway’s national body responsible for curating, producing and activating art in public space, with responsibility delegated from the Ministry of Culture and Equality, was in charge of decorating the publicly accessible areas of the building. Artists, owner and users also took part in the process. Here, we will not look at the processes behind, but rather, like Pietikäinen et al. (Citation2011), we view the curated artwork in the semiotic landscape as ‘frozen action’, i.e. a material manifestation of actions taken by someone in the past, ‘frozen’ in time and space. For people encountering the semiotic landscape, the past social action is less important than the here-and-now effect of its material manifestation. We examine how the institution’s historical past and the contemporary multilingual and multicultural context are represented in the semiotic landscape of the new building. To follow up this descriptive enquiry, we ask which discourses about linguistic and cultural diversity are present in the landscape, and what these discourses do in terms of language ideological processes.

We begin by introducing the local historical and contemporary sociolinguistic context surrounding our case. Then we outline our theoretical perspectives, followed by a description of data and data collection procedures. Next, we present the analysis, followed by our discussion and concluding remarks.

2. Our case: historical and sociolinguistic contexts

Tromsø is located above the Arctic circle and is the largest city in Northern Norway. The city has a growing and diverse population. In 2022, Statistics Norway (Citation2023) counted 77,992 inhabitants, representing around 140 different nationalities. With many inbound and visiting students and faculty, UiT is a diverse, international workplace.

Diversity is not a new characteristic of Tromsø. For the Sámi people, Tromsø has been their home area for centuries. Some Sámi had their summer homeland in Tromsø, moving here with the reindeer from the winter pastures inland. Others had Tromsø as their permanent home, with a combination of fisheries and farming as their main livelihood, while others again moved here more recently for study or work. Nowadays, Tromsø is an important city for both the Sámi and Kven people. Linguistic and cultural diversity came under pressure during the eighteenth century, as the Danish-Norwegian king initiated processes of internal colonisation (cf. Olsen & Sollid, Citation2022). Starting with missionary work among the Sámi, the aim was to homogenise Norway’s population, demonstrate ownership of the land and identify the region as Norwegian – and not Sámi. After the Danish-Norwegian union ended in 1814, Norway promoted the idea of the new nation state without including the historical diversity. National security concerns towards Finland were used as the basis for promoting national and social cohesion. Education became the main arena for colonising the minds (cf. Minde, Citation2003; Ngũgĩ, Citation1986) of coming generations of citizens, promoting Norwegian ways of thinking and doing, and silencing Sámi and Kven voices and experiences. In many ways, this policy was successful, as many people were linguistically and culturally assimilated into Norwegian ways.

Since the 1950s, there has been a growing ethnopolitical mobilisation, first among the Sámi and later, in around the 1980s, also among the Kven. This mobilisation resulted in a shift of direction in Norway’s politics towards the Sámi and Kven people, by granting the two minoritised groups different political and juridical status. The Sámi people have the status of Indigenous people, according to the International Labour Organization’s Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, ratified in 1990. The Kven/Norwegian Finns (together with Jews, Roma, Romani people/Taters and Forest Finns) are acknowledged as a national minority, according to the Council of Europe’s Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, ratified in 1999. Both Sámi and Kven are protected by the Council of Europe’s European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Norway has extended obligations under part III for Sámi, with three different Sámi languages, North Sámi, Lule Sámi and South Sámi, and, on a more limited basis, under part II for Kven, Romani and Romanes. The varying juridical status given to Sámi and Kven is also reflected in Norwegian education and language policies, granting wider rights to the Sámi compared to the Kven (cf. Education Act, Citation1998; Kindergarten Act, Citation2005; Language Act, Citation2021).

Tromsø has been an educational centre since the mid-nineteenth century and houses the oldest teacher education programme in Norway. A teacher education seminar first began in Trondenes in 1824, and was relocated to Tromsø in 1848. Christianity and the Norwegian language, history, geography and teaching skills were core subjects (cf. Dahl, Citation1976, p. 32), giving the students Norwegian perspectives on content, teaching and education, leaving little space for Sámi and Kven viewpoints and knowledge. This Norwegian profile was based on nationalism and social Darwinism and corresponds well with ideas of colonisation and assimilation. Seemingly paradoxically, the institution also offered the opportunity to study Sámi and Kven, for example through state-funded scholarships for student teachers who made a commitment to teach in Sámi districts for at least seven (later five) years (Dahl, Citation1976, p. 33). At the beginning, these scholarships were mostly for Sámi students, but later Norwegian students were prioritised. Looking back, the Tromsø teacher seminar, on the one hand, was key to implementing assimilation politics. On the other hand, it was an important institution for distributing knowledge about the languages and for using Sámi and Kven as a pedagogical tool when teaching children with little or no Norwegian language competence. The primary goal, however, was not to support Sámi or Kven as important languages for future generations, but to use these languages as an instrument to transition the students into Norwegian.

From the outset, the teacher education programme in Tromsø was connected to colonisation and assimilation, but eventually the ideological underpinnings of the teacher education programme changed, providing room for various viewpoints, including decolonialisation. The first ECTE programme in Tromsø started in 1972 at a time of Sámi ethnopolitical mobilisation. Simultaneously, Norway became more relevant for labour migration. Today, the national regulations for ECTE in Norway require the education programme to promote an understanding of Sámi culture as part of the national culture, and to emphasise indigenous peoples’ rights both nationally and internationally. Moreover, increasing attention is paid to diversity in ECEC in general and to multilingualism specifically (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, Citation2017).

Johansen and Bull (Citation2012) studied the semiotic landscape at UiT about a decade ago. They showed how official language policies for Sámi and Kven left traces in the semiotic landscape and argue that North Sámi is ranked higher at UiT than in Norway in general, signalling a Sámi identity through both signage and art. Despite being taught at UiT, Kven was rather invisible in the semiotic landscape.

3. Theoretical perspectives

In our study, we view the semiotic landscape as a nexus of discourses that circulate across time and space and intersect, here, in physical space (Hult, Citation2017; Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004). Some discourses circulate on rather slow or long timescales, for example connected to the building, ideologies, or historical developments, while others develop on much faster scales of time, for example connected to human action (Hult, Citation2017; Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004; Lemke, Citation2000). A semiotic landscape, with signs, artwork, and architecture, etc., is thus a process emerging from people’s actions (including frozen actions, cf. Pietikäinen et al., Citation2011), which are historically and geographically situated (Hult, Citation2017). In addition to timescales, highlighting the interplay of various spatiotemporal dimensions, we use the concepts of voice and heteroglossia (Bakhtin, Citation1981) to deal with the expression of multiple people’s and agents’ actions and histories. This includes viewing the art exhibition as a cohesive whole and, at the same time, a multitude of artistic voices and ways of expression in dialogue with each other, audiences, and surrounding contexts. Moreover, the concept of geosemiotics is an important theoretical underpinning. We study ‘the social meaning of material placement of signs and discourses and our actions in the material world’ (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003, p. 2). Signs derive their meaning from how and where they are placed, their materiality and content, and how people use the space.

Scollon and Scollon (Citation2003, p. 170 f.) describe four different zones in public spaces that encourage or limit certain activities: exhibit or display spaces, passage spaces, special use spaces and secure spaces. Exhibit and display spaces are spaces to be looked at as people pass through or walk by them, while doing other things or heading somewhere. An important aspect of such spaces is that they are not meant to be altered by the public. Passage spaces, such as stairs, are reserved for passage and are not explicitly marked for other use. They do not invite people to pause or stop, so they implicitly invite people to pass. Passage spaces may also be exhibit spaces. For example, stairways might be decorated with artwork, so that the distinction between passage and exhibit spaces is sometimes blurred. Special use spaces indicate a purpose for certain activities, for example seats in a café. Secure spaces relate to nationalism and terrorism discourses and are less relevant for our analysis.

Szabó (Citation2015, p. 28 f.) argues that there is a difference between spaces in schools connected to their functional characteristics and the audience at which they are directed. While outside walls often address general audiences and provide basic information about the institution, some inner parts are used by insiders and outsiders, while others are mainly used by insiders. For example, classrooms usually address insiders and involve certain types of discourses and material environments. Rooms targeted at both insiders and outsiders, such as entrance areas, corridors, and stairways, are important for the institution’s official and often top-down self-identification. As our study is concentrated on these spaces in the department building, discourses on diversity connected to overarching political levels and the institution’s self-identification are the focus of analysis. The fact that the task of decorating the building’s semi-public spaces was delegated to a government service institution – KORO – supports this connection.

In our analysis, we focus on how linguistic and cultural diversity is represented in discourses in the semiotic landscape and what these discourses achieve in terms of language ideological processes (cf. Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004, p. 2). To take a closer look at these processes, we apply the three concepts of iconization, fractal recursivity and erasure (Irvine & Gal, Citation2000, p. 37 f.). Iconization involves the process of connecting linguistic features to social groups, so that linguistic features or activities begin to index these groups to the extent that this relationship is perceived as normalised and an inherent quality. Fractal recursivity means projecting an opposition that exists at some level of relationship to other levels. For example, a process of partitioning or creating hierarchies between groups, linguistic varieties, or communities at one level may recur at other levels. Erasure is the ideological process of simplifying the sociolinguistic field in a way that renders sociolinguistic phenomena, persons or activities that do not fit into the ideological scheme invisible.

4. Analytical framework, methods, and data

The analytical framework of this paper is Scollon and Scollon’s (Citation2004) nexus analysis (see also Hult, Citation2017). Nexus analysis is a discourse-ethnographic approach to social action and social practice (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004), with theoretical underpinnings from interactional sociolinguistics, linguistic anthropology, and critical discourse analysis, emphasising the scales of interpersonal relationship, community and society (cf. Hult, Citation2017, p. 91). In this framework, data collection takes place as the researchers engage and navigate the nexus of practice. The analysis, in turn, starts with social action, which is seen as a nexus of practice where discourses with past, present, and future are bundled together to a layered simultaneity. In Scollon and Scollon’s (Citation2004) framework, the intersecting discourses are the historical body, the interaction order, and the discourses in place. The historical body is connected to an individual’s personal beliefs and experiences. The interaction order refers to the norms, expectations and possibilities that affect human interaction in a situation. Here, this includes how the placement of objects in space might facilitate certain types of action. Discourses in place describe the discourses that surface in and circulate through any social action, with particular histories, values and ideologies (see also Hult, Citation2017, pp. 93–98; Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003).

The process of collecting and analysing data is extended in time and set in different spaces. Our ethnographic approach aims to uncover some of the complexity of space and timescales (cf. Hult, Citation2017; Lemke, Citation2000; Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004) in the semiotic landscape. To explore our research questions, we combined different methods, producing different types of data. The core method is three systematic research walks, one in the old and two in the new building, together lasting about six hours. This method is inspired by Szabó (Citation2015), highlighting the dialogic co-construction of meanings, narratives and ideologies, while surveying the material environment together. As researchers, who knew each other, we walked together in buildings with which we were already familiar. During the research walks, we discussed our observations and documented the semiotic landscape through pictures. This picture collection was supplemented on different occasions and now contains about 800 pictures. After the first walk in the new building, we wrote fieldnotes and recorded a field conversation between the three of us (about one hour).

In this process, we noticed that the semiotic landscape of the building reflects a multitude of discourses, and not only about linguistic and cultural diversity. At the same time, we recurrently talked about who and what was represented in the curated artwork and how such representation related to the overall semiotic landscape. This emerged as an ethnographic ‘rich point’ (Hornberger, Citation2013, p. 102; Agar, Citation2008), a point at which we became aware that our previous assumptions were insufficient to explain our observations, and where new questions arouse. The curated art exhibition, entitled Nordnorsk lærdom (‘Northern Norwegian learnings’) emerged as a confusing, yet important, space for analysing how an impression of linguistic and cultural diversity in an educational context was constructed, in terms of official representation and self-identification, and the presence and absence of certain aspects. Keeping the complexity and layers of discourses in mind, we chose to narrow the focus of analysis to the curated artwork in the building’s publicly accessible spaces on the two lower floors. On these two floors there are two entrance areas, a stairway, a café, hallways, and classrooms. As there is no artwork in the classrooms, they are not part of our analysis. The two floors are documented by around 200 pictures. The analysis of these spaces is based on what we saw, discussed and documented during the research walks (e.g. content, material properties and placement of artwork, and properties of space), i.e. the geosemiotics and discourses in place of the artwork. The analysis is supplemented by two published texts about the artwork in the new building (KORO, Citation2020; Sørstrøm, Citation2020).

We acknowledge that we are not neutral interpreters of the semiotic landscape. As users of both the previous and new building, both the data collection and analysis are influenced by our everyday use of these spaces, as well as our own connections to historical and transnational diversity. Following this, our own historical bodies are important during fieldwork and analysis, not least for the emergence of ethnographic rich points. We see our positionality as an asset guiding us in documenting and critically analysing diversity.

Simultaneously, we acknowledge that some perspectives might be overlooked. We did not trace the perspectives of other historical bodies involved in the semiotic landscape, such as the curators of the art project, artists, students, other members of staff and visitors. Even though interaction order is part of the nexus analysis approach, we did not systematically observe how people engaged with the art or the rest of the semiotic landscape. Our analysis of the interaction order is based on our interpretation of the possibilities for interaction opened up by material aspects of the space (cf. Androutsopoulos & Kuhlee, Citation2021; Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003).

5. Findings

The analysis concerns the curated artwork and its position in the surrounding semiotic landscape. The exhibition consists of old and new artwork. Most of the newly curated art is shown on KORO’s website (KORO, Citation2020). We highlight some of the pieces of art that we find particularly relevant for our research question. Pictures 1–4 were chosen from among the 200 pictures to illustrate our findings.

5.1. General description of the semiotic landscape

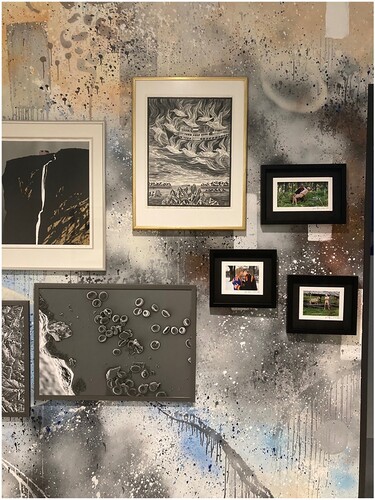

A first, general impression is that the semiotic landscape in these spaces visually appears as rather tidy and orderly. It is dominated by artwork and the building’s architecture, which together appear as a planned and frozen action, with a unitary and yet heteroglossic voice. Artwork (mainly paintings and photographs, but also a few other installations) is mostly placed on walls with colourful graffiti paintings (covering major parts of the two hallways), but also white or grey walls (see picture 1). The selection and composition of the artwork and its placement in physical space is part of a curated art project with the title Nordnorsk lærdom (‘Northern Norwegian learnings’) .

We find very few posters and notices on the walls that would represent other voices. Rather, a small notice in Norwegian states that putting up posters is not allowed, which seems to strictly govern the space (see picture 2). This notice points to a policy and efforts to centrally organise the presence of voices in the exhibit space, (cf. Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003) .

5.2. Representation of diversity

Our first research question deals with how the ECTE institution’s historical past and the contemporary multilingual context are represented in the semiotic landscape of the new building. It is clear from both the artwork presented and written descriptions of the art project that a central intention is to represent diversity. To mirror Tromsø’s diversity, to display a dialogue between multiple political and aesthetic positions, and to make visible various sources of learning and knowledge from the North, are mentioned as important aims of the exhibition (KORO, Citation2020; Sørstrøm, Citation2020). Diversity is visualised through contrasts, as well as symbolic representation. First, tradition and modernity are put into relation by placing pictures showing aspects of traditional life on graffiti-painted walls. Artwork from different times is presented in close vicinity to each other. Also, the use of techniques from traditional handicraft side-by side with modern working techniques brings tradition and modernity into dialogue with each other. Second, the graffiti-painted concrete walls transmit a stereotypical impression of urbanity. At the same time, there are numerous paintings of rural landscapes or ways of living. Although stereotypical, locating these together suggests a dialogue between rural and urban life, which can be transferred to the institution’s location in the urban centre of Tromsø and its responsibility for the whole region. It also suggests regional rootedness. Third, the exhibition includes multiple expressions of Sámi culture, ranging from well-known symbols of Sámi identity, such as traditional clothes and duodji (traditional handicraft), to political discourses and Sámi livelihood. Fourth, some photographs combine symbols of Sámi identity and Northern Norwegian nature with expressions of sexuality and homosexual love. Picture 3 illustrates these contrasts .

The exhibition suggests that diversity in a Northern Norwegian context involves a set of quite different components and relations, including a connection to the past. The department’s own history is addressed in pictures of buildings which housed the institution in earlier times, as black and white photographs of teaching situations, and historical artefacts used in teaching, as well as portraits of earlier leaders, which are found at several places in the building. Making visible the timescales of the department contributes to the complexity of discourses in place (cf. Hult, Citation2017; Lemke, Citation2000).

The art exhibition, as part of the semiotic landscape of the building, is heteroglossic in a Bakhtinian sense: ‘[…] a diversity of social speech types (sometimes even diversity of languages) and diversity of individual voices, artistically organized’ (Bakhtin, Citation1981, p. 262). The exhibition expresses an authorial voice, which artistically organises an overall narrative of diversity, regional rootedness, knowledge and learnings in and from the North (cf. Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003, p. 170; and Blommaert, Citation2013, p. 43) on public signs, as a demarcation of spaces. At the same time, each artist and piece of art in the exhibition expresses their own voice and are, according to KORO’s (Citation2020) description, meant to be part of a dialogue with audiences such as students and staff.

Considering the diversity of voices and the representation of diversity through these voices, we want to point to some aspects of historical and contemporary diversity and the institution’s own history that are given little or no space in the art exhibition. Portraits of earlier leaders (older men in positions of power) constitute an important part of representations of persons in the semiotic landscape. There are also some more artistic representations of people in the art exhibition. Among these, there are practically no children. The absence of children or references to children’s lifeworld in the art exhibition stands in contrast to the central role of children in ECTE, teacher education and other fields of study and research at the Department. Furthermore, the art exhibition does not include explicit references to Kven language and identity, nor to transnational diversity and migration. While the institution’s history and its relation to the region are important motives, voices that address the institution’s role in the implementation of assimilation policies and its historical responsibility remain hidden in the semiotic landscape.

Part of the art project is a book containing poetry in Sámi and Norwegian and a luohti (traditional Sámi song, also called joik or yoik) by Sámi artist Mary Albmonieida Sombán Mari (Sombán Mari, Citation2020; see KORO, Citation2020). The title of the book, Beaivváš mánát/Leve blant reptiler, in Sámi and Norwegian, can be translated to ‘Children of the sun/Living among reptiles’. Beaivváš mánát links to Sámi mythology and usually refers to the Sámi people. In this context, it can also relate to Sámi children in Norwegian educational institutions, living among reptiles. The Sámi and Norwegian poems are not translations of each other. Especially the Norwegian texts explicitly and critically address the institution’s historical role in colonisation, linguistic and cultural assimilation, and the suppression of traditional knowledge and Sámi children’s ways of knowing and learning. No other part of the art project addresses the institution’s historical responsibility as explicitly as this book. Though part of the art project, neither the book nor the luohti are visible or accessible in the semiotic landscape. In online descriptions of the art project (e.g. KORO, Citation2020), the book is allocated a central position. Illustrations by the same artist, which are part of the exhibition, relate to illustrations in the book. The poetry and its critical voice are thus somewhat present, but at the same time invisible in the building and therefore have an ambiguous position.

The placement – and absence – of voices and artwork in physical space also affect the interaction order, i.e. which opportunities for interaction and dialogue with the artistic voices it opens up. While the poetry is invisible in the building, other voices in the semiotic landscape receive meaning through their positioning in space. Major parts of the artwork addressing regional rootedness and diversity are placed in a relatively narrow corridor, which leads to classrooms (see picture 1). Offering only narrow space, the corridor does not invite people to stay, but rather urges those who pass by to keep walking, bearing characteristics of a passage space, as well as a display space (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003). At the same time, we see that little art is placed in the areas where seats and tables invite students to stay and work (special-use spaces in Scollon and Scollon’s (Citation2003) terms). In some smaller seating areas, paintings are placed decoratively above the tables. However, the exhibition’s discourses of diversity do not become visible here.

Though connected, it seems that there is a relatively clear distinction between different spaces in the public parts of the building, not only with respect to different functions (Szabó, Citation2015), but also to how different voices emerge in the landscape. As Scollon and Scollon (Citation2003) stress, exhibit and display spaces are not meant to be altered by others. Spaces where art is exhibited do not invite the expression of other voices. As picture 2 shows, there are clear indications of desired patterns of behaviour (Blommaert, Citation2013; Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003) that do not allow altering by adding other voices to the landscape. Although there are examples of rapid changes in the semiotic landscapes of educational buildings (e.g. Laihonen & Tódor, Citation2017), the expression of official voices in the semiotic landscape is typically rather stable, and changes occur according to prolonged timescales.

Despite the dominance of the curated artwork and architecture, other voices are present in the building, but we find them in different spaces. The Department of Education, its staff and students contribute their own voices, making the semiotic landscape more heteroglossic. These voices operate on different timescales to the building’s architecture and the art exhibition, which are intended to be in place for a long time. Expressions range from a movable banner in the entrance area advertising the ECEC teacher education programme, with a short text at the bottom: ‘We educate ECEC teachers who are well-equipped to meet and contribute to the diversity that children and families with different cultural and linguistic backgrounds represent’, a Sámi and a Kven flag attached to the entrance door of a master’s students’ reading room, cardboard boxes, artwork and craft made by students, and post-its encouraging students before exams, to the use of stairs as a concert stage. These spaces create a different form of diversity which includes various voices of individuals and groups, as well as the department's voice, which is at a different level to the official UiT state institution presence .

5.3. Discourses in place and language ideological processes

Our second research question is: which discourses about linguistic and cultural diversity are present in the landscape, and what do these discourses do in terms of language ideological processes? In the previous section, we identified relations of urban and rural contexts, tradition, and modernity, as well as aspects of Sámi culture and identity as central motives of the art exhibition. Moving into a new building, and thereby creating new spaces for working and learning, offered the opportunity to reflect on the institution’s identity, and its present and future role, and to mark a new status quo.

Let us first underpin that both diversity, Sámi perspectives and regional rootedness are central to the construction of this new status quo. By addressing nordnorsk lærdom (‘Northern Norwegian learnings’) and highlighting the rootedness of such learnings in the region and history of Sámi and Norwegian encounters, the art exhibition also relates to ongoing global discourses on centres and peripheries in the production and validation of knowledge and power (e.g. Connell, Citation2007). This involves the articulation and acknowledgement of indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing, which had been silenced earlier. Though situated at the Norwegian and European periphery, UiT contributes to learning and knowledge production on indigenous topics by indigenous and non-indigenous academics, nationally and internationally. There are also mutual relations between Tromsø and UiT as urban and academic centres with people and communities in the surrounding rural peripheries. Research and education at UiT, including ECTE, thus contribute to decolonising and indigenising education (cf. Olsen & Sollid, Citation2022).

As mentioned above, besides making visible various sources of learning and knowledge from the North, the art exhibition aims to mirror Tromsø’s diversity. We observe that the construction of diversity and local rootedness foregrounds some – and leaves out other – elements of contemporary diversity. Expressions of Kven identity and culture, as well as transnational diversity, are not explicitly included in the art exhibition, although equally part of Northern Norwegian society (cf. also Johansen & Bull, Citation2012). Representations of children and their lifeworld are almost completely absent. This is striking because childhood is an important topic in the work of the Department of Education. Working with diversity in contemporary society, of which transnational diversity is an important part, is central to the mandate for ECEC and teacher education. Regarding history, the institution’s heritage as Norway’s oldest higher education institution is clearly addressed, and obviously with pride. At the same time, the poetry book, which addresses the institution’s historical responsibility for its role in linguistic and cultural assimilation, remains hidden. The question of historical responsibility is not addressed in other ways.

In the construction of a new status quo of institutional identity that takes place in the semiotic landscape, we can identify ideological processes (Irvine & Gal, Citation2000) of erasure, in that certain aspects of reality are – consciously or unconsciously – left out of the construction of diversity. A second semiotic process, fractal recursivity, is also at work here: The (non-) visibility of diversity in the semiotic landscape reproduces hierarchies between people and languages which arose from official language policies. The Kven as a national minority and transnational migrants in Norway are granted more limited linguistic rights (or even none) than the Sámi population and the Norwegian majority. Finally, the construction of an institutional identity through the visual narration of history, diversity and regional rootedness also involves processes of iconization. This includes the perception of a strong relationship between institution, building, artwork, and narrated history, which is reinforced through its anchoring in physical space (cf. official top-down self-identification, Szabó, Citation2015). Timescales play an important role in this process. While other parts of the semiotic landscape and the expression of voices can change quickly, the art exhibition and architecture are meant to last for a much longer time. The constructed narrative about diversity becomes frozen in physical space (cf. Pietikäinen et al., Citation2011). Dynamic social and cultural processes of multilingual and multicultural encounters are turned into something permanent – which ‘inevitably contains the seeds of essentialism’ (Blommaert, Citation2013, p. 27). The physical and permanent character of the art exhibition do not immediately allow for stronger articulation of those voices which are currently subject to erasure.

To summarise, while the art exhibition is intended to be heteroglossic – and certainly is – by orchestrating a multitude of artistic voices, styles and expressions, there are also strong centripetal forces at work, ‘forces that serve to unify and centralize the verbal-ideological world’ (Bakhtin, Citation1981, p. 270). Besides such centralising forces in artwork and architecture, we see that voices of multiple other historical bodies engaging in the place are manifested in the landscape. Operating on much shorter timescales, these make the process of spatial sense-making more heteroglossic and dynamic.

6. Discussion and conclusion

In the analysis, we have shown that there are both heteroglossic and essentialising language ideological processes in the construction of a narrative of institutional identity that takes place in the semiotic landscape. Compared to the old teacher education building, diversity, Sámi identities and regional roots of knowledge are clearly emphasised. This emphasis is, however, accompanied by the erasure of particularly Kven culture and identity, transnational diversity, and children and their lifeworld. This finding resembles, for example, the observations made by Gal (Citation2012) in her analysis of the historical construction of linguistic standards and homogeneity by European nation-states, compared to the management of linguistic diversity in more recent EU policies. Gal (Citation2012, p. 24) argues that ‘the move to valorise multilingualism is not a grand change of sociolinguistic regime. It is rather the redeployment of the same value distinction – in fractal recursion […]’.

An interesting feature of the semiotic landscape has to do with discourses and processes of erasure and enunciation. The art project explicitly aims at foregrounding roots of knowledge and ways of knowing in the northern periphery and especially in Sámi culture. Historical processes of erasure and the silencing of Sámi ways of knowing are addressed explicitly in the poetry book, which is part of the curated art project. The art project thereby engages critically with global discourses of a grand erasure of experience and knowledge from global peripheries, while making universal claims from the viewpoint of some (western, metropolitan) centres (Connell, Citation2007, p. 46). While such processes of erasure are addressed explicitly, the art project simultaneously reproduces the same type of semiotic processes. The fact that the poetry book, which addresses these processes most explicitly, is not physically present, reinforces this impression. Further, while the construction of a new iconic picture of Northern-Norwegian diversity and identity stresses Sámi identity (cf. Johansen & Bull, Citation2012) and involves traces of decolonisation, other linguistic and cultural hierarchies are reinforced through the erasure of expressions relating to Kven and transnational diversity.

According to Gorter et al. (Citation2019), there is not necessarily a direct link between the visibility of a minority in the linguistic landscape and the vitality of the language and culture in the community. Language and other semiotic expressions in the linguistic landscape may indicate that the minority enjoys some degree of attention and raising of awareness but does not automatically ease the maintenance of language or culture. In a similar vein, the presence of minority languages and cultural expressions in educational institutions might be connected to internal policies supporting the minority and its language, (cf. Johansen & Bull, Citation2012). Moreover, the representation of minorities in semiotic landscapes may involve various voices that negotiate and contest official signage (Gorter et al., Citation2019, p. 488 f.). As pointed out above, the semiotic landscape in our analysis also includes a multitude of voices at other – official and non-official – levels. These voices might be understood as negotiating or contesting more dominant discourses in place. For example, taping a Kven flag on the door of the master’s students’ reading room could be understood as an act of negotiating the absence of Kven in the official landscape. The banner explicitly representing ECTE may negotiate the absence of transnational diversity. The post-its encouraging students before exams and the use of the stairs as a concert stage involve a different interaction order, for example, by re-shaping passage spaces to exhibit spaces and inviting their alteration (cf. Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003). In general, these voices negotiate the official self-identification present in the authorial voice and alter the idea of whose place the department is (cf. Blommaert, Citation2013).

Having analysed the representation of diversity in the semiotic landscape in detail, we may now ask how the semiotic landscape, its discourses in place and interaction orders facilitated by it, might socialise students, staff, and visitors into certain conceptualisations of diversity and identity. As educational space, students encounter the semiotic landscape whenever they enter the building. How semiotic landscapes are perceived varies depending on individual and collective perspectives. This will influence users’ actions and also the reconstruction of the landscape through action (Androutsopoulos & Kuhlee, Citation2021). As Androutsopoulos and Kuhlee (Citation2021, p. 44) show, occasional field conversations with students in their study revealed that they did not necessarily pay much attention to the artwork in school. Exploring student teachers’ perspectives of the curated artwork would therefore add interesting aspects to whether and how the artwork is perceived. While the building’s semiotic landscape conveys a meta-sociolinguistic stance, ECEC and school teachers are assigned a meta-sociolinguistic task, namely to transmit an understanding of diversity as enrichment for everybody. As Brown (Citation2012, p. 282) writes, ‘Schoolscapes project ideas and messages about what is officially sanctioned and socially supported within the school’. The erasure of both Kven and transnational diversity from the official voices of the landscape may provoke the impression that these forms of diversity are neglected or less valued. Likewise, the erasure of children contrasts the focus of the departments’ educational programmes. This would also lead to the question of whether or how students and others are invited to engage in, negotiate or contest the landscape. This perspective is raised by one of the curators quoted in Sørstrøm (Citation2020), who says that it is a dream that the artwork should be used to discuss everything from aesthetic choices to politics, and relations of power and myths about the North. In the light of this intention, the physical location of nordnorsk lærdom (‘Northern Norwegian learnings’), partly in a narrow corridor with a clear passage space character (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003), appears as an obstacle to creating these kinds of spatial educational practices. Using the research walk method and performing semiotic landscape analysis together with students might offer interesting pedagogical opportunities.

As teachers and former teachers at the department, we know that historical and transnational diversity are emphasised in teaching. In ECTE, children and their lifeworld are a central topic. Moreover, the multitude of other voices, operating on shorter timescales than the institution’s official self-identification, contribute dynamically to making sense of the physical space. It is important to keep these dynamics in mind, also with respect to our use of method. Turning ethnographic observations of the semiotic landscape into written text automatically involves freezing more dynamic processes in time and space (Blommaert, Citation2013). We have sought to counter this challenge by including different sources of information, and comparing and discussing our individual, subjective perceptions, and by conducting repeated research walks through the building at different points in time.

To conclude, on viewing the semiotic landscape from a nexus analytical perspective we observe a complex nexus of multiple discourses and policies. Among these are the institution’s history, regional history and culture, the local and regional rootedness of knowledge and ways of knowing, linguistic and cultural diversity in society and the institution’s mandate to prepare student teachers for work in multilingual settings. In the semiotic landscape, there is a fractal recursivity of the opposition and hierarchy between Norwegian and Sámi on the one hand, and Kven and transnational diversity on the other. In the official viewpoint, Kven and transnational diversity are erased from the constructed narrative of institutional identity.

With a view to diversity, the national framework plan for the content and task of kindergartens (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, Citation2017), in line with other educational policy documents, stresses that children must be given the opportunity to experience that there are many ways of thinking, acting, and living. Additionally, linguistic diversity should be experienced as an enrichment for all children. The semiotic landscape we have analysed makes some clear statements with respect to what this might imply – including the challenging of established, culture-centred worldviews. At the same time, our analysis brings to the fore a multitude of obstacles such an endeavour can encounter. An important learning is that, even with the best intentions, implicit language ideologies remain strong frames for social action.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agar, M. H. (2008). The professional stranger: An informal introduction to ethnography (2nd ed.). Emerald.

- Androutsopoulos, J., & Kuhlee, F. (2021). Die sprachlandschaft des schulischen raums: Ein diskursfunktionaler ansatz für linguistische schoolscape-forschung am beispiel eines hamburger gymnasiums. Zeitschrift für Angewandte Linguistik, 2021(75), 195–243. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfal-2021-2065

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). Discourse in the novel (C. Emerson & M. Holquist, transl.). In M. Holquist (Ed.), The dialogic imagination. Four essays by M. M. Bakhtin (pp. 259–422). University of Texas Press.

- Blommaert, J. (2013). Ethnography, superdiversity and linguistic landscapes: Chronicles of complexity. Multilingual Matters.

- Brown, K. D. (2012). The linguistic landscape of educational spaces: Language revitalization and schools in Southeastern Estonia. In D. Gorter, H. F. Marten, & L. Van Mensel (Eds.), Minority languages in the linguistic landscape (pp. 281–298). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230360235_16

- Connell, R. (2007). Southern theory. Polity Press.

- Dahl, H. (1976). Tromsø offentlige lærerskole i 150 år. Lærerskolen. https://www.nb.no/items/URN:NBN:no-nb_digibok_2007060500037

- Education Act. (1998). Act relating to Primary and Secondary Education and Training (LOV-1998-07-17-61). Lovdata. https://lovdata.no/dokument/NLE/lov/1998-07-17-61

- Forskrift om rammeplan for barnehagelæreutdanning. (2012). Forskrift om rammeplan for barnehagelæreutdanning. (FOR-2012-06-04-475). Lovdata. https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2012-06-04-475

- Gal, S. (2012). Sociolinguistic Regimes and the management of «Diversity». In A. Duchene, & M. Heller (Eds.), Language in late capitalism: Pride and profit (pp. 22–42). Routledge.

- Gorter, D., Marten, H. F., & Van Mensel, L. (2019). Linguistic landscapes and minority languages. In G. Hogan-Brun, & B. O’Rourke (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of minority languages and communities (pp. 481–506). https://doi-org.mime.uit.no/10.1057/978-1-137-54066-9_19

- Hornberger, N. H. (2013). Negotiating methodological rich points in the ethnography of language policy. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2013(219), 101–122. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2013-0006

- Hult, F. M. (2017). Nexus analysis as scalar ethnography for educational linguistics. In M. Martin-Jones, & D. Martin (Eds.), Researching multilingualism. Critical and ethnographic perspectives (pp. 89–104). Routledge.

- Irvine, J. T., & Gal, S. (2000). Language ideology and linguistic differentiation. In P. V. Kroskrity (Ed.), Regimes of language. Ideologies, politics, and identities (pp. 35–83). School of American Research Press.

- Johansen, ÅM, & Bull, T. (2012). Språkpolitikk og (u)synliggjøring i det semiotiske landskapet på Universitetet i Tromsø. Nordlyd, 39(2), 17–45. https://doi.org/10.7557/12.2472

- Kindergarten Act. (2005). Act relating to Kindergartens (LOV-2005-06-17-64). Lovdata. https://lovdata.no/dokument/NLE/lov/2005-06-17-64

- KORO. (2020). UiT Norges arktiske universitet, Tromsø, Institutt for lærerutdanning og pedagogikk (ILP). https://koro.no/prosjekter/uit-norges-arktiske-universitet-institutt-for-lærerutdanning-og-pedagogikk-ilp/

- Laihonen, P., & Tódor, E. M. (2017). The changing schoolscape in a Szekler village in Romania: Signs of diversity in rehungarization. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 20(3), 362–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2015.1051943

- Language Act. (2021). Act relating to Language (LOV-2021-05-21-42). Lovdata. https://lovdata.no/dokument/NLE/lov/2021-05-21-42

- Lemke, J. L. (2000). Across the scales of time: Artifacts, activities, and meanings in ecosocial systems. Mind, Culture and Activity, 7(4), 273–290. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327884MCA0704_03

- Minde, H. (2003). Assimilation of the Sami – implementation and consequences. Acta Borealia, 20(2), 121–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/08003830310002877

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o. (1986). Decolonising the mind: The politics of language in African literature. James Currey.

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2017). Framework plan for kindergartens: contents and tasks. framework-plan-for-kindergartens2-2017.pdf.

- Olsen, T. A., & Sollid, H. (2022). Introducing indigenising education and citizenship. In T. A. Olsen & H. Sollid (Eds.), Indigenising education and citizenship. Perspectives on policies and practices from Sápmi and beyond (pp. 13–32). Scandinavian University Press. https://doi.org/10.18261/9788215053417-2022-02

- Pesch, A. M., Dardanou, M., & Sollid, H. (2021). Kindergartens in Northern Norway as semiotic landscapes. Linguistic Landscape, 7(3), 314–343. https://doi.org/10.1075//ll.20025.pes

- Pietikäinen, S., Jaffe, A., Kelly-Holmes, H., & Coupland, N. (2016). Sociolinguistics from the periphery. Small languages in new circumstances. Cambridge University Press.

- Pietikäinen, S., Lane, P., Salo, H., & Laihiala-Kankainen, S. (2011). Frozen actions in the Arctic linguistic landscape: A nexus analysis of language processes in visual space. International Journal of Multilingualism, 8(4), 277–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2011.555553

- Scollon, R., & Scollon, S. W. (2003). Discourse in place. Language in the material world. Routledge.

- Scollon, R., & Scollon, S. W. (2004). Nexus analysis. Discourse and the emerging internet. Routledge.

- Sollid, H. (2019). Språklig mangfold som språkpolitikk i klasserommet. Målbryting, 10(2019), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.7557/17.4807

- Sombán Mari, M. A. (2020). Beaivváš mánát/Leve blant reptiler. Mondo Books.

- Sørstrøm, H. (2020). Skal speile Tromsøs mangfold. Hakapik: Et nettmagasin innen kunstkritikk. https://www.hakapik.no/home/2020/8/29/skal-speile-tromss-mangfold

- Statistics Norway. (2023). Kommunefakta. Tromsø. https://www.ssb.no/kommunefakta/tromso

- Straszer, B., & Kroik, D. (2021). Promoting indigenous language rights in saami educational spaces: Findings from a preschool in southern saepmie. In E. Krompák, V. Fernández-Mallat, & S. Meyer (Eds.), Linguistic landscapes and educational spaces (pp. 127–146). Multilingual Matters.

- Szabó, T. P. (2015). The management of diversity in schoolscapes: An analysis of Hungarian practices. Apples – Journal of Applied Language Studies, 9(1), 23–51. https://doi.org/10.17011/apples/2015090102