ABSTRACT

This paper focuses on vocabulary development in oral language productions of three elementary school-age sibling pairs growing up in a trilingual setting. This longitudinal study describes the development of the children's narrative competence over three years. The corpus analysed consists of retellings of animated films. The contribution deals with the lexical development in the three languages of the children, in particular the length of the productions, lexical diversity and lexical sophistication. Lexical diversity is measured by the Guiraud Index. It is assumed that the children's vocabulary becomes more diverse with increasing age. Lexical sophistication is examined by measuring the average frequency of words used by the participants. It is assumed that as children's vocabularies grow, they will include more and more ‘rare’ low-frequency words in their productions. Assuming that the school language is the dominant language, the question is whether lexical diversity and sophistication increase with age in all three of the children's languages, or whether this is only the case in the school language. The results show that lexical development varies from child to child. However, a certain trend can be observed, indicating that school vocabulary is becoming more sophisticated.

Introduction

In this article we discuss analyses of the words that six trilingual children use in oral narratives. The results are part of a longitudinal study on narrative skills in trilingual children (Reiser-Bello Zago, Citation2019). Retellings of animated films by three pairs of elementary school-aged siblings provide the data basis. These oral narratives were collected in two different settings, one with a monolingual and one with a multilingual listener. The data were collected over three years. At T1, the children are between 5;0 and 9;7 years old, and at T3, between 7;6 and 11;8. Four of the six children grow up with GermanFootnote1, French, and Spanish. The two others with English, French and Spanish. They all use their respective three languages in their daily life.

To study the lexical development of the children, we analysed the length of the productions, the lexical diversity, and the lexical sophistication.

Literature on trilingual children

Following Hoffmann (Citation2001a) we can group studies of trilingualism in three groups: the acquisition of the third language in formal contexts, sociolinguistic aspects of trilingualism and trilingualism in children. As has been noted repeatedly (Barnes, Citation2011; Chevalier, Citation2015; Kazzazi, Citation2011; Montanari, Citation2009a, Citation2009b, Citation2010, Citation2011, Citation2013 and Quay, Citation2001, Citation2008, Citation2011b), unlike studies of bilingual children and Bilingual First Language Acquisition (BFLA), there is little research in trilingual first language acquisition.

Several relatively recent studies have focused on the factors that influence active bi- or trilingualism (e.g. Arnaus Gil et al., Citation2021; Chevalier, Citation2015) or on how bilingual and trilingual families try to maintain heritage languages (Cantone, Citation2022).

Montanari (Citation2013, p. 62) outlines that studies on TFLA (Trilingual First Language Acquisition) are rare, not very systematic and limited to case studies dealing with specific topics such as cross-linguistic influence (Kazzazi, Citation2011), code-switching (Edwards & Dewaele, Citation2007; Hoffmann & Stavans, Citation2007; Stavans & Muchnik, Citation2008; Stavans & Swisher, Citation2006) or the relationship between input and language development (Barnes, Citation2006, Citation2011). Montanari (Citation2013, p. 63) sees the reasons for the small number of studies on trilingual children, on the one hand, in the fact that it is very time-consuming to document the development of three languages. On the other hand, Montanari regrets that TFLA is often considered a variant of BFLA. Hoffmann (Citation2001b) also argues along these lines, explaining that most studies on trilingualism are conducted within the theoretical framework of research on bilingualism. ‘No attempt has been made to delimit trilingualism as a concept in its own right, and often it has been assumed to be an extension of bilingualism’ (p. 1). Unsworth (Citation2013) states: ‘Recent research suggests that trilingual first language acquisition proceeds in much the same fashion as bilingual and monolingual first language acquisition’ (p. 35). Quay (Citation2011a, p. 6), by contrast, sees TFLA as a unique phenomenon with its own characteristics. Quay (Citation2011b), Barnes (Citation2011), Kazzazi (Citation2011) and Montanari (Citation2011) show that, just as the ‘perfectly balanced’ bilinguals are a rather scarce species, trilinguals do not usually master the three languages equally well, but that there are typically one dominant and two weaker languages.

Another characteristic of trilingual speakers is that the community language (which is often not their family language) is usually the most important and most frequently used language for them (Hoffmann, Citation2001b). Furthermore, the quality of input and language-specific characteristics can strongly influence the respective language skills of trilinguals (Montanari, Citation2013, p. 63).

Hoffmann (Citation2001b) hypothesises that – apart from quantitative differences – there are no fundamental differences between bilinguals and trilinguals. In contrast, ‘certain social, cultural and, above all, psychological and personality-related factors may assume disproportionately high significance in influencing trilingual competence, as compared with their influence in the case of bilingual competence’ (p. 2). Moreover, as the second author of this contribution argues (Berthele, Citation2021), there are good reasons to question simplistic ideas of counting languages in the multilingual repertoire, which implies also that strong claims about fundamental differences between bi – and multilingualism are problematic both conceptually and empirically. When, under which circumstances, and for whom learning a child’s third or nth (n > 2) language is fundamentally different from learning a second language is an empirical question and the object of ongoing inquiries. Given the absence of converging evidence in the field, we take an agnostic stance regarding this question. What is certain, however, is that emerging trilingual repertories. as those described in the present study involve more degrees of freedom for cross-linguistic influence and lower average exposure times per language compared to bilingual repertories.

In sum, studies in the field of childhood trilingualism are so far few in number, many are limited to a short period of time and use data from only one or two still very young children (e.g. Barnes, Citation2006; Cruz-Ferreira, Citation2006; Dewaele, Citation2000; Hoffmann, Citation1985; Kazzazi, Citation2007, Citation2011; Montanari, Citation2005, Citation2010; Quay, Citation2001, Citation2008). Bonvin et al. (Citation2018, p. 136) argue that the older the learners, the more diverse the lexical repertoires become, which might be one of the reasons why many studies are conducted with very young children.

Studies reporting on very young children are undoubtedly important to determine if and how trilingual development is different from bilingual development. Nevertheless, studies of older children are also needed to document their language acquisition. This article aims to contribute to this by studying the lexical development of six elementary school children who grow up speaking three languages in their daily lives.

Method

In order to obtain as complete a picture as possible of the development of language acquisition and narrative competence in trilingual learners, it would undoubtedly be useful to analyse spontaneous speech data. As it is complicated to collect and analyse spontaneous authentic speech data from several children in three languages, we opted for a more controlled genre and data collection setting. We decided to create a situation in which the children had to retell the narratives of short video stimuli to a person who pretends to ignore those stories. The setting chosen thus comes with certain constraints, but we still deem it relatively natural as the children are familiar with similar settings and tasks from the school context. If this is the case, it is possible that our setting is particularly suitable to elicit data in the children’s school language. Regardless of this potential bias, the setting chosen elicits largely comparable oral productions. If, on the other hand, spontaneous speech data had been used, the different subsamples would have depended on the different contexts and the topics of the respective situations of the recordings, which would have led to data subsets whose vocabulary is hardly comparable in any meaningful way. Another reason for this choice is also because the narrative framework is well researched (Berman & Slobin, Citation1994; Strömqvist & Verhoeven, Citation2004).

Study participantsFootnote2

The study involves three pairs of siblings of primary school age. Various researchers noticed that it is difficult to compare data from multilinguals or to draw general conclusions because it is difficult to find subjects whose language acquisition takes place under comparable conditions (e.g. Barron-Hauwaert, Citation2000; Grosjean, Citation1998). Hence the idea of sibling pairs. The situation of siblings is more comparable than if one were to work with children from different families, even if their language acquisition is not always the same. It is possible, for example, that younger children do not receive the same input as older ones. Or, as a recent study showed, in bilingual families the first born seems to have no preference for one of the two languages while 60% of the younger siblings prefer the language of the environment (Jiménez Gaspar & Arnaus Gil, Citation2022). Nevertheless, the sibling pairs should allow for interesting comparisons within and across specific family environments. The six children who participated in the study all live near the bilingual (French and German) town of Fribourg/FreiburgFootnote3 in Switzerland and have a comparable socio-economic status. The dominance ratio between the languages was determined through interviews and conversations with the parents and the children ().

Table 1. Language settings of the study participants.

The brothers Ben (7;4 – 9;10) and Neil (9;2 – 11;8) live in a French speaking village and visit the local school in French. The father is a French-Spanish bilingual and speaks Spanish to the boys when he’s alone with them. The family language is English which is also the first language of the mother. Neil is the oldest participant of the study.

The second sibling pair are the sisters Ana and Elsa (6;5 – 8;11). They live in a French speaking village but go to school in German which is also the language of the mother. Their father speaks Spanish with the girls, and Spanish is also the language the whole family uses when they are all together. The girls are twins. Twins that are raised together are interesting as they share both age and family environment (and, depending on the type of twins, all or half of the genetic predispositions). They occasionally display characteristic delays in language development (for an overview, see Lui, Citation2011, p. 11f).

The third sibling pair consists of Laura (5;0 – 7;6), the youngest participant and her brother Peter (7;0 – 9;5). Just like Ana and Elsa, they speak Spanish with the father or when the whole family is together. They live in a French speaking village and go to the local school in the same language. When the mother is alone with the two children, she speaks Swiss German to them.

When selecting the stories to be retold to the children, the choice fell on Pingu, a stop motion children’s television series created by Otmar Gutmann and Erika Brueggemann (https://www.youtube.com/user/pingu). Since this is a longitudinal study and the children were to tell the same story in their three languages at least once a year, it seemed important to choose a medium that was as engaging as possible. We wanted the children to enjoy the task. The short 5-minute Pingu-films seemed attractive for children, especially since similar things happen to Pingu that can also happen to the study participants. Another advantage of this template is the classic narrative structure and Pingu speaks an onomatopoeic language which avoided the problem that the language used in the film could influence the children.

shows an example of how the data collection was done for a child speaking German, French and Spanish.

Table 2. Method example of one child/one year.

One of the assumptions was that the children would behave differently if they knew that their interlocutor was either monolingual or also spoke the child's other languages. Therefore, the child was supposed to tell a story once to a monolingual listener and once to a multilingual listener, in each language. The listeners were acquaintances of the respective families and thus not complete strangers. Surprisingly, retelling to a mono- or plurilingual interlocutor had no impact on the narrations. In the remainder of this paper we will therefore analyse the data in aggregated fashion over these two conditions.

Since there are three languages involved and it would probably have become too monotonous if each child always had to tell the same story, we decided that each child should tell two stories in each setting, language, and measurement point. One story was always the same (‘Pingu pretends to be ill’), while the other varied (see ). The identical story was elicited to maximise comparability of the data collected. Thus, every year, each child had to watch two videos and tell these two stories in each of his three languages to a monolingual listener and two stories to a multilingual listener. The instructions were always given in the language in which the child was to retell the story. After watching the episode, the listener asked the child, ‘Can you please tell me the story?’. The study was conducted over three years. The resulting corpus contains twelve retellings (four in each language) per child per year.

While this paper focuses on lexical development, other aspects of narrative skill development were analysed in this longitudinal study. For example, we examined the strategies the children used to compensate for lexical gaps and found that there was only occasional switching or mixing patterns; these aspects were discussed elsewhere (Reiser-Bello Zago, Citation2019).

In order to get a better insight into the development of trilingual vocabulary in the narratives of the six children, the length of the productions, the lexical diversity and the lexical sophistication was analysed. Lexical diversity is a metric that captures the number of different words used in the oral production. We opted for the simple version of Guiraud’s R (Daller et al., Citation2003) as this metric has shown to be valid and reliable and representing relatively well human raters’ assessment of lexical diversity of texts (Vanhove et al., Citation2019). Lexical sophistication, on the other hand, is a metric for the rarity of the words the children use. Below we use corpus frequencies to assess this construct.

Results and discussion

The length of the production

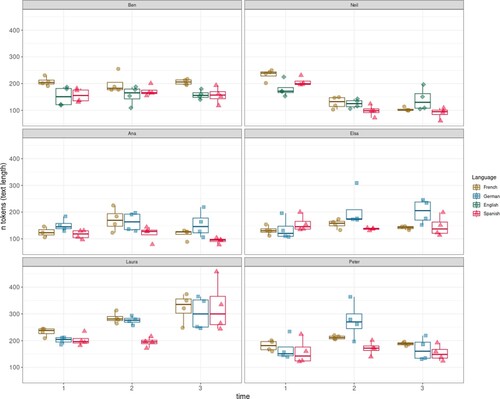

The length of the retellings was analysed as a general index of fluency. The productions are very different in length. The longest story was told by Laura in the third year of the recordings in Spanish with 458 tokens, while Neil, the oldest participant, told the same story with only 61 tokens. There is also no clear picture in terms of age or the different languages. It is for example not the case that the stories are generally shorter in what we supposed to be the weakest language of the child.

Helms-Park et al. (Citation2022) found in their study on narrative organisation skills in trilingual Canadian children, that those who produced more word types in their native language also tended to produce longer narratives in all three languages. The same trend can be observed among the children in our study. Laura, for example, generally produces longer narratives than the other children in all her three languages, while Neil’s stories get shorter from year to year (also in all his three languages).

The longest production

Laura (7;5) T3 Pingu as a Babysitter. 4:48 min

Primero Pingu estaba en su casa con su mamá después su mamá se lavaba los pies y Pingu estaba jugando después su mamá le dice Pingu ven a lavarte los pies después vamos con mi amiga después va Pingu a lavarse los pies después tiene una mancha sobre la panza y dice su mamá Pingu lávate tu mancha aquí sobre tu panza después se lava la mancha después dice bueno Pingu ven conmigo con mi amiga después viene después su amiga la mamá de Pingu dice toca a la puerta después abre la amiga de la mamá de Pingu la puerta y dice Hola entran después entran los dos y después hablan un poco juntas y Pingu ve los bebés después se sienta en una silla después viene un señor abren la puerta y dice por favor pueden venir rápido y después dice si la amiga de la mamá de Pingu después la mamá de Pingu le dice a Pingu vas a dar la comida y así a los bebés nosotros nos vamos cuida los bebés después se van las mamás y después están en su cama los bebés después un bebé empieza a llorar y el otra se va y quiere hacer caer una maceta que esta sobre la mesa después dice Pingu no no no después va con el bebé y dice está bien está bien después el bebé que lloraba va en la cocina y mueve la un algo después dice Pingu no no no después otra vez levanta el bebé después le dice no Pingu después y van en su cama y empiezan a llorar después los pone en sus sillas Pingu pone los bebés en sus sillas y después pues les da comida da comida a uno después el otro llora y va a dar la comida al otro y el otro llora muchas veces así después otra vez da comida y después ya acabaron de comer y después uno hace chis entonces le cambia el pañal al bebé y después le pone un nuevo pañal y los pone y ve al otro si también hizo chis y no hizo y después dice muy bien después los pone en su cama y después pues les dice duerman bien después él va a leer un libro y lloran entonces otra vez viene y les mueve un poco la cama después otra vez lloran otra vez mueve la cama otra vez lloran otra vez mueve la cama después tiene una idea toma un hilo lo amarra a la cama y a su pie después lloran y después mueve su pie se mueve la cama después lee y otra vez mueve su pie cuando lloran y después se duerme y las mamás vienen y se ríen

The shortest production

Neil (11;8) T3 Pingu as a Babysitter. 1:12 min

Pingu estaba iba a guardar los bebés y pero cuando llego los bebés estaban llorando y estaban cogiendo las tocando las cosas calientes entonces Pingu les puso en la silla para comer y estaban comiendo pero después tenían que cambiarlos y había después los puso en la cama pero no se dormían entonces los hizo dormir con su pie y ya ()

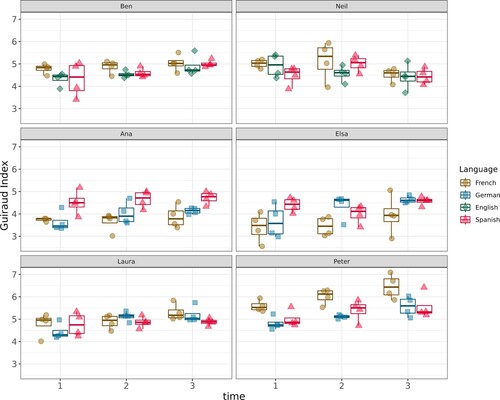

Lexical diversity

The lexical diversity of the retellings was measured by the Guiraud index (Guiraud, Citation1954). Jarvis (Citation2002) and Daller et al. (Citation2003) showed that the Guiraud index (Types divided by √ Tokens) is a reliable measure for texts up to 300 words. Some of Laura’s third year narratives contain slightly more than 300 words, the remaining productions however are below this value.

To calculate the simple Guiraud index, all words used in the productions of the children were included as soon as they were recognisable, even if, for example, a verb was incorrectly inflected, or a preposition was not used according to the norm of the target language. For the present study, all inflected forms of verbs and nouns were considered as one type.

As such metrics of lexical diversity underlie language-specific constraints (e.g. differences in compoundingFootnote4), the comparison of scores across languages needs to be done with great caution. However, within a language, indices such as Guiraud’s R validly reflect differences in lexical richness, both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. Thus, we hypothesised that the Guiraud index for a given child within each of her three languages increases from year to year, most reliably so in the school language.

As shows, this is the case for many children, if not for all. For instance, Peter’s values for two of his three languages steadily increase across time. In his school language French (blue), the values are higher than in the other languages. Whereas Peter’s values for German also increase steadily over time, his Spanish seems to stagnate between T2 and T3.

The results show that for all children – apart from Neil, the oldest one – the productions become more lexically diverse over the three years in the respective school language, which is reflected in a higher Guiraud Index. For the three boys the values are higher in the school language than in the other two languages, but again these cross-language differences must not be overinterpreted. Laura’s school language French seems to develop mostly between T2 and T3, and her German seems to develop mostly between T1 and T2. No clear tendency is visible for Spanish in her case. The results of the twin sisters (Ana and Elsa) show that the family language Spanish, their dominant language certainly in the first year, does not develop much, whereas the other two languages show some increase in lexical diversity across time. The low values in particular for German at T1 can be explained by the fact that the two girls just started school in German when the first recordings took place. Before first grade, they had both attended Kindergarten in French. While the school language quite dramatically increases regarding lexical diversity from the first to the second year on for Elsa, the increase is comparably inferior for her twin sister Ana. Surprisingly, her family language Spanish is the one with the highest Guiraud Index over all three years.

Lexical diversity indicates how rich the vocabulary used in a production is. However, measurements such as the Type Token Ratio or the Guiraud index only quantify the number of different words used but do not consider further aspects of which words are chosen, for example whether they are very common or rather elaborate.

Based on the observation that the vocabulary of some children seems to evolve towards the use of more and more specific terms, we tried to find a way to account for more qualitative dimensions of vocabulary development. This can be illustrated with a detailed analysis of the descriptions of a specific event in the stimuli as provided by Laura, the youngest participant.

While Laura’s family language is Spanish which is also the language of the father, the mother speaks Swiss German with the child. At the time of the first recording, Laura had just started school (Kindergarten) in French since the family lives in a French-speaking village. Previously, she spent most of the day with her mother and about two days a week with a French speaking nanny. In this example, Laura had to describe a scene where Pingu is in danger of being late for school. To arrive in time, Pingu runs, slides on the snow, and jumps onto his chair, thus he manages to arrive just in time. It is the reference to the ground elements (the chair and the desk) of this dramatic motion event we are interested in.

G: German; S: Spanish; F: French; M: Monolingual listener; P: Plurilingual listener

Laura T1 5;0 – 5;6

In the 1st year, the 5-year-old uses the word for school in all the languages. In French she uses once siege (seat) which is not appropriated for the situation. Siège would be rather used for a seat in an airplane for example.Laura T2 6;4 – 6;6

In the second year, Laura still says Schule (school) in German, mesa (table) in Spanish and once bureau, which means desk in French which is already more specific.Laura T3 7;3 – 7;6

In the third year, the 7-year-old uses once Schule (school) and once Platz (place) in German, escuela (school) and silla (chair) in Spanish. And again chaise (chair) in French and once pupitre which is the most specific word one can use to name a desk in school.To summarise we can observe that there are no big changes in German and Spanish. Hence, in the school language French the nouns become more and more specific. Laura goes from ‘école’ to ‘bureau’ to ‘pupitre’ a clear increase regarding the sophistication of the vocabulary.

This example shows how the child, certainly in the school language French, starts using increasingly specific and therefore also statistically rarer words to refer to the scene’s events and elements. In our final analysis we thus investigate to which extent there is a general tendency in the trilinguals’ languages to integrate such more specific words. In other terms, we ask whether there is a longitudinal tendency towards more ‘rarity’ in the children’s narratives. We hypothesise that this should be the case most clearly in the language of schooling.

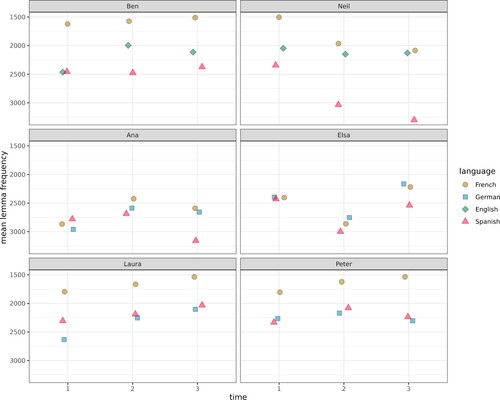

Lexical sophistication

To measure lexical rarity or sophistication, the average frequency of the types that the children use in their productions were calculated. For German, Spanish and English the SUBTLEX (compiled by Brysbaert & New, Citation2009) word frequency database was used and for French Lexique 3 (version 3.80). These lists are based on subtitles of films and series which seemed to be the appropriated for oral language productions. All the types used by the children were listed and their average frequency was calculated. The frequency per million words was used (SUBTLwf); this is a standardised value that is independent of the corpus size. As there is no such database in Swiss-German, Laura and Peter’s productions in this language were translated into standard German.

In general, one would expect children's vocabulary to grow steadily with age, with an increasing number of relatively rare words being acquired as the child keeps being exposed to rich language input (e.g. Harley, Citation1992, p. 169). The average frequency of the words they use should therefore decrease from year to year, since the children – at least this is what can be assumed – use more and more specific and less frequent words, words with low frequency, as their vocabulary increases. As a consequence, the average frequencies of the narrations would be expected to decrease from year to year. Based on the hypothesis that school language is the dominant language of children, the question is whether lexical diversity and sophistication in all three of the children's languages increases with age, or whether this is only the case in the children's school (and increasingly dominant) language.

shows the average frequencies per child, language, and year of data elicitation. In the case of Laura, the results correspond exactly to our expectations. Not only does the average rarity of words used increase from year to year in the school language French, but the same evolution can be observed in the girl's other two languages. For the other five children, however, the results are less clear. For Ben and Peter, lexical variety and differentiation in their school language French also increases from year to year. Peter's Spanish and German sophistication increases from T1 to T2 but decreases again at T3. This is also the case for Ben's productions in the home language, English. His values for Spanish do not change much. If we compare only the values for T1 and T3, the average rarity of the school language German also increases for the twin sisters. Ana's German and French narrations become more sophisticated from T1 to T2, but then again less sophisticated and thus more frequent words are used on average at T3. Elsa's use of rarer words in German and Spanish decreases from T1 to T2, but her vocabulary seems more sophisticated again in the third year. For the oldest participant in the study, Neil, the development in his three languages shows exactly the opposite of what was expected. As mentioned earlier, Neil's productions became shorter and shorter over time, and his lack of enthusiasm for the narrative task may well also express itself in the lack of lexical elaboration.

Figure 3. Average frequencies per child, language, and year of data elicitation. The y-axis is reversed to map rarity to higher location of points.

Following Brysbaert et al. (Citation2011, p. 28), we assume that subtitle frequencies are a good proxy for children’s oral input, better than frequencies derived from written corpora in the same languages. Given the popularity of streaming services (including channels such as Netflix, Amazon Prime, and YouTube), this type of corpus seems particularly well suited to represent features of the audio-visual input the children are increasingly exposed to. Using such corpora, however, can be problematic when it comes to frequencies of specific words: We have observed that certain nouns have a very low frequency according to the SUBTLEX list, but they are very common at least in Swiss children's language and often used, for example words like luge (1,22) (sledge) or cartable (1,58) (schoolbag) have low frequencies compared to bébé (191,63) (baby). Bonvin et al. (Citation2018, p. 18) made the same observation. Especially in short texts such words can influence the frequency measure. Frequency based metrics of sophistication also do not always adequately reflect stylistic choices. For example, if a child is telling a story and addressing someone outside her family, – the less personal utterance ‘Pingu and his mother went to the doctor’ seems more communicatively appropriate and thus ‘better’ than ‘Pingu and his mum went to the doctor’. Nevertheless, the word mum has a lower frequency in our corpus, thus it would be considered more sophisticated, than the word mother. Thus, what would be considered a sign for increasing pragmatig and stylistic competence of the child, is paradoxically mirrored in corpus-based frequency measures. This may be another reason why the results of the frequency analysis were not always as we expected, and why any such result should be interpreted with great caution.

It seems therefore that the frequency measurement we applied is not ideal for an account of increasing lexical sophistication in the retellings. Ideally, reference corpora for children's speech would have to be used. However, a child's vocabulary is always strongly influenced by the environment, living conditions, and especially age. Therefore, it might be difficult to create reliable reference corpora for children's speech. The simple Guiraud index does not change when a speaker uses a word that is considered less frequent than a more frequent word (Treffers-Daller et al. (Citation2016) propose more advanced versions of the index that to some extent do reflect rarity). This means that it cannot be used to illustrate phenomena such as the example shown above of Laura using the word école in T1, the more specific term bureau in T2, and pupitre in T3. Overall, it seems that the Guiraud index may be used fruitfully to illustrate the lexical development of the children observed in this study, as long as we keep in mind that it does not capture lexical sophistication. Although the corpus-based metrics of sophistication, as demonstrated above, are problematic when it comes to the impact of age-specific (overall low frequency) vocabulary, adding such frequency metrics clearly enriches the description of lexical development.

Conclusion

There are two main results of our investigation: First, there is an overall tendency to more diverse and more sophisticated vocabulary use in the children’s languages over time. Second, this tendency is sometimes rather weak or even totally absent, in other words there is considerable inter-individual variability. The results are thus rather different from child to child, and even siblings do not always behave similarly, which indicates that multilingual development is highly individual (e.g. Berthele & Udry, Citation2021). More specifically, we observe the following tendencies:

First, decreasing average frequencies of types (if we only compare the results of the first with the third year, this is the case for five of the six children), as well as an increase in the Guiraud index and longer productions indicate that the children's vocabulary in the respective school language expands with increasing age. The language proficiency of the school language is the most advanced, and the other aspects of narrative skills studied are also best developed in the school language (in most cases). For trilinguals this was already shown by Hoffmann (Citation1985) or Stavans and Swisher (Citation2006, p. 205). The second tendency is, that children develop very individually, even if their language acquisition takes place under similar conditions. Silva-Corvalán (Citation2014) made the same observation with her bilingual grandchildren: they have different levels of competence in their minority language Spanish in spite of the fact that they are brothers.

One limitation of the study is the number of participants. While this is not unusual for a study of trilingual acquisition to work with (very) small samples, results from only six children do not allow us to make big generalisations. However, it is undoubtedly better to observe several children rather than just one. For example, if we had only observed the development of the youngest participant, the results regarding the lexical sophistication would be exactly what we expected. The results for the other five children force us to put this result into perspective. Further it is possible that the school language was favoured by the narrative task. Children are probably more used to solving such tasks in their respective school language. Finally, the template may not always have been age appropriate. While the other children seemed happy during the three years to watch and retell the Pingu stories, Neil, the oldest participant, was visibly bored by these videos from the second year on. Indeed, his productions were getting shorter and shorter. In the third year, he explicitly told us that these Pingu videos were rather something for younger children. Factors like this lack of motivation to do a task can strongly influence the results of a study and should be considered.

Some changes in the children's vocabularies are beyond what could be discussed in this contribution. As a general point related to the paradoxical changes in sophistication discussed above, we noticed the tendency that certain expressions that are rare in adult language – such as faire pipi (to pee) instead of aller aux toilettes (to go to the toilet) – are only used by young children and disappear with age. A similar phenomenon seems to happen with diminutives, which are used mostly in the early productions of the children in Swiss-German and Spanish. However, in the analyses as we have conducted them here, these phenomena are not systematically considered. Other approaches to the description of vocabulary development, such as human ratings along different dimensions or more qualitative descriptions, would allow scholars to capture such phenomena and give a more complete picture in particular of lexical sophistication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Two of the children (Laura and Peter) speak Swiss-German with their mother. The mother of the twin sisters (Ana und Elsa) also speaks to her daughters in a Swiss German dialect, while they speak standard German at school and always respond in standard German, even when spoken to in Swiss-German.

2 Participants’ names were changed, and the data were anonymized where possible. These alterations have not distorted the scholarly meaning.

3 According to the official website of the Canton of Fribourg/Freiburg in 2019, 69% of the population was French-speaking and 26% German-speaking (https://www.fr.ch/etat-et-droit/statistiques/fribourg-en-chiffres). The communes of the Canton of Fribourg are officially either German- or French-speaking, but many communes are also home to members of the respective language minority.

4 For instance, a compound noun in German represents a unique lemma (‘Wasserflasche’, water bottle), whereas in French (‘bouteille d’eau’) it can be counted as a multiword unit or as three lemmas. Such differences arguably have an influence on type-token based metrics.

References

- Arnaus Gil, L., Müller, N., Sette, N., & Hüppop, M. (2021). Active bi- and trilingualism and its influencing factors. International Multilingual Research Journal, 15(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2020.1753964

- Barnes, J. (2006). Early trilingualism: A focus on questions. Multilingual Matters.

- Barnes, J. (2011). The influence of child-directed speech in early trilingualism. International Journal of Multilingualism, 8(1), 42–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790711003671861

- Barron-Hauwaert, S. (2000). Issues surrounding trilingual families: Children with simultaneous exposure to three languages. Zeitschrift für Interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht, 5, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.26083/tuprints-00012087

- Berman, R. A., & Slobin, D. I. (1994). Relating events in narrative: A crosslinguistic developmental study. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Berthele, R. (2021). The extraordinary ordinary: Re-engineering multilingualism as a natural category. Language Learning, 71(S1), 80–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12407

- Berthele, R., & Udry, I. (Eds.). (2021). Individual differences in early instructed language learning: The role of language aptitude, cognition, and motivation. EuroSLA Studies 5, 2021. Language Science Press. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5378471

- Bonvin, A., Vanhove, J., Berthele, R., & Lambelet, A. (2018). Die Entwicklung von produktiven lexikalischen Kompetenzen bei Schüler(innen) mit portugiesischem Migrationshintergrund in der Schweiz. Zeitschrift für Interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht (ZIF), 23, 135–148. http://tujournals.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/index.php/zif/

- Brysbaert, M., Buchmeier, M., Conrad, M., Jacobs, A. M., Bölte, J., & Böhl, A. (2011). The word frequency effect: A review of recent developments and implications for the choice of frequency estimates in German. Experimental Psychology, 58(5), 412–424. https://doi.org/10.1027/1618-3169/a000123

- Brysbaert, M., & New, B. (2009). Moving beyond Kučera and Francis: A critical evaluation of current word frequency norms and the introduction of a new and improved word frequency measure for American English. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers, 41(4), 977–990. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.977

- Cantone, K. F. (2022). Language exposure in early bilingual and trilingual acquisition. International Journal of Multilingualism, 19(3), 402–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2019.1703995

- Chevalier, S. (2015). Trilingual language acquisition: Factors influencing active trilingualism in early childhood. In Trends in language acquisition research, vol. 16. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Cruz-Ferreira, M. (2006). Three is a crowd? Acquiring Portugese in a trilingual environment. Multilingual Matters.

- Daller, H., van Hout, R., & Treffers-Daller, J. (2003). Lexical richness in the spontaneous speech of bilinguals. Applied Linguistics, 24(2), 197–222. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/24.2.197

- Dewaele, J.-M. (2000). Trilingual first language acquisition: Exploration of a linguistic ‘miracle’. LaChouette, 31, 41–45.

- Edwards, M., & Dewaele, J.-M. (2007). Trilingual conversations: A window into multicompetence. International Journal of Bilingualism, 11(2), 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069070110020401

- Grosjean, F. (1998). Bilingualism: Language and cognition. Cambridge University Press.

- Guiraud, P. (1954). Les caractéristiques statistiques du vocabulaire. Presses Universitaires de France.

- Harley, B. (1992). Patterns of second language development in French immersion. Journal of French Language Studies, 2(2), 159–183. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959269500001289

- Helms-Park, R., Petrescu, M. C., Pirvulescu, M., & Dronjic, V. (2022). Canadian-born trilingual children’s narrative skills in their heritage language and Canada’s official languages. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2022.2059078

- Hoffmann, C. (1985). Language acquisition in two trilingual children. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 6(6), 479–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.1985.9994222

- Hoffmann, C. (2001a). The status of trilingualism in bilingualism studies. In J. Cenoz, B. Hufeisen, & U. Jessner (Eds.), Looking beyond second language acquisition. Studies in tri- and multilingualism (pp. 13–25). Stauffenburg.

- Hoffmann, C. (2001b). Towards a description of trilingual competence. International Journal of Bilingualism, 5(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069010050010101

- Hoffmann, C., & Stavans, A. (2007). The evolution of trilingual codeswitching from infancy to school age: The shaping of trilingual competence through dynamic language dominance. International Journal of Bilingualism, 11(1), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069070110010401

- Jarvis, S. (2002). Short texts, best-fitting curves and new measures of lexical diversity. Language Testing, 19(1), 57–84. https://doi.org/10.1191/0265532202lt220oa

- Jiménez Gaspar, A., & Arnaus Gil, L. (2022). The role of (older) siblings in the acquisition of heritage languages: Early Catalan-German bilingualism in Germany.

- Kazzazi, K. (2007). Man se tā baladam. Language awareness in a trilingual child. Presentation given at the “L3” Conference, 3–5 September 2007, Stirling, Scotland.

- Kazzazi, K. (2011). Ich brauche mix-cough: Cross-linguistic influence involving German, English and Farsi. International Journal of Multilingualism, 8(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790711003671879

- Lui, B. F. (2011). Trilingual development of a pair of twins in Hong Kong: Implications for the multilingual development of young children [Thesis]. University of Hong Kong. https://doi.org/10.5353/TH_B4659673

- Montanari, S. (2005, March 20–23). Phonological differentiation in early trilingual development: Evidence from a case study [Paper presentation]. Fifth International Symposium on Bilingualism, Barcelona, Spain.

- Montanari, S. (2009a). Pragmatic differentiation in early trilingual development. Journal of Child Language, 36(3), 597–627. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000908009112

- Montanari, S. (2009b). Multi-word combinations and the emergence of differentiated ordering patterns in early trilingual development. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 12(4), 503–519. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728909990265

- Montanari, S. (2010). Translation equivalents and the emergence of multiple lexicons in early trilingual development. First Language, 30(1), 102–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723709350528

- Montanari, S. (2011). Phonological differentiation before age two in a Tagalog–Spanish–English trilingual child. International Journal of Multilingualism, 8(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790711003671846

- Montanari, S. (2013). Productive trilingualism in infancy: What makes it possible? World Journal of English Language, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.5430/wjel.v3n1p62

- Quay, S. (2001). Managing linguistic boundaries in early trilingual development. In J. Cenoz, & F. Genesee (Eds.), Trends in bilingual acquisition [Trends in language acquisition research 1] (pp. S. 149–S. 199). John Benjamins.

- Quay, S. (2008). Dinner conversations with a trilingual two-year-old: Language socialization in a multilingual context. First Language, 28(1), 5–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723707083557

- Quay, S. (2011a). Introduction: Data-driven insights from trilingual children in the making. International Journal of Multilingualism, 8(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790711003671838

- Quay, S. (2011b). Trilingual toddlers at daycare centres: The role of caregivers and peers in language development. International Journal of Multilingualism, 8(1), 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790711003671853

- Reiser-Bello Zago, E. (2019). Un poco mucho? – Über die Entwicklung narrativer Fähigkeiten bei dreisprachigen Kindern [Dissertation]. Universität Freiburg. https://folia.unifr.ch/unifr/documents/308139

- Silva-Corvalán, C. (2014). Bilingual language acquisition: Spanish and English in the first six years. Cambridge University Press.

- Stavans, A., & Muchnik, M. (2008). Language production in trilingual children: Insights on code switching and code mixing. Sociolinguistic Studies, 1(3), 483–511. https://doi.org/10.1558/sols.v1i3.483

- Stavans, A., & Swisher, V. (2006). Language switching as a window on trilingual acquisition. International Journal of Multilingualism, 3(3), 193–220. https://doi.org/10.2167/ijm020.0

- Strömqvist, S., & Verhoeven, L. (2004). Relating events in narrative: Typological and contextual perspectives. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Treffers-Daller, J., Parslow, P., & Williams, S. (2016). Back to basics: How measures of lexical diversity Can help discriminate between CEFR levels. Applied Linguistics, http://applij.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2016/04/07/applin.amw009.abstract

- Unsworth, S. (2013). Current issues in multilingual first language acquisition. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 33, 21–50. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190513000044

- Vanhove, J., Bonvin, A., Lambelet, A., & Berthele, R. (2019). Predicting human lexical richness ratings of short French, German, and Portuguese texts using text-based indices. Journal of Writing Research, 10(3), 499–525. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2019.10.03.04