ABSTRACT

The study aimed to analyse the production of plosive sounds by trilingual speakers of L1 Polish – L2 English – L3 Norwegian. The main objective was to trace any changes in the VOT production of fortis and lenis stops in all three languages (Polish, English and Norwegian) produced by novice L3 learners with a focus on possible cross-linguistic interactions. The investigation was conducted across three testing times throughout the first year of L3 learning. The results show that participants maintained separate VOT patterns in all three languages. What is more, VOT production patterns changed over time, but only in the voiced series of stops. The study also provides evidence for asymmetry between voiced and voiceless stops, as the two series turned out to be affected by CLI in a different manner.

Introduction

Research on cross-linguistic influence (CLI) in multilinguals has been in its prime for a few decades now. However, compared to other language domains, investigations into CLI in phonological acquisition have not been so comprehensive. What is more, the majority of studies in this domain seem to be centred on CLI from previously learnt languages on the L3, whereas any potential impact on the L1 or L2 has been less studied. From a phonological perspective, the acquisition of stops by foreign language learners has been a rather popular research agenda for some time now. Nevertheless, the L3 literature to date has focused mostly on the voiceless series of stops (e.g. Amengual, Citation2021; Llama & López-Morelos, Citation2016; Sypiańska, Citation2013; Wrembel, Citation2015). More recent investigations also include the voiced counterparts (e.g. Gabriel et al., Citation2018; Geiss et al., Citation2022), but the body of literature on this matter is still rather scarce. What is more, the area that remains largely unexplored concerns the developmental aspects of the acquisition of stops by multilingual learners over time, especially when it comes to a holistic approach to investigating interactions between all the languages in a speaker’s repertoire (but see Nelson, Citation2022 for a notable exception). Hence, the current study aims to fill these gaps by analysing the production of plosives by L1 Polish – L2 English – L3 Norwegian speakers at the early stages of learning their L3 throughout three testing times. The main objective is to explore whether early-stage multilingual learners keep their categories apart while they advance in their L3 proficiency and to trace the development of voice onset time (VOT) acquisition in all three languages in both series of stops (/p,t,k/ and /b,d,g/).

This paper is structured in the following manner. It begins with a discussion of the state of the art in VOT production research in the context of L2 and L3 acquisition. Further, the VOT parameter is discussed from the point of view of the three languages under investigation, namely Polish, English and Norwegian. The following sections feature the research design and methodology description. Finally, the results are presented and discussed with reference to the extant literature on multilingualism.

VOT in bi-/multilingualsFootnote1

VOT is a feature of plosive consonants that is a measure of the time between the stop release and the voicing onset (Lisker & Abramson, Citation1964). This parameter is said to be the most salient cue that allows to distinguish between voiced (/b, d, g/) and voiceless (/p, t, k/) plosives and, what is more, it is considered to be one of the most commonly researched phonetic features in the L2 speech literature (Hansen Edwards & Zampini, Citation2008). Lisker and Abramson (Citation1964) distinguish three main types of VOT, namely (1) voicing lead or prevoicing in which voicing starts before the release of a plosive; (2) short-lag VOT in which voicing begins with or just after the release of a stop (VOT duration between 0 and 35 ms); (3) long-lag VOT in which voicing begins later after a stop release (VOT durations longer than 35 ms).

VOT has been widely researched in the last decades, being a parameter relatively comparable across languages and easy to measure. Not only has it been measured by phoneticians to make comprehensive descriptions of specific languages, but its analysis has also been employed in research on foreign language acquisition to investigate possible cross-linguistic interactions during the process of L2 and L3 acquisition.

From the SLA perspective, a number of studies resorted to VOT for an analysis of cross-linguistic influence. In one of his seminal studies, Flege (Citation1987) examined VOT durations of /t/ produced by L1 English speakers who were proficient in L2 French. The obtained results indicated that VOT values for L2 French /t/ were in between the target values for English and French, suggesting an occurrence of CLI between the two languages. Similar trends were also attested for speakers of different linguistic repertoires (cf. Flege, Citation1991; Flege & Eefting, Citation1987; Flege & Hillenbrand, Citation1984; Hazan & Boulakia, Citation1993; Thornburgh & Ryalls, Citation1998; Williams, Citation1977). What is more, this trend was also observed for reverse settings. In Flege’s (Citation1987) study, L1 French speakers who resided in the L2 English-speaking country produced L1 French /t/ with VOT values in between those of English and French, giving the evidence for the existence of L1 drift, which refers to phonetic changes in the native language (L1) caused by recent experience in another language (L2) (Chang Citation2019).Footnote2

More recent studies on VOT acquisition in bilinguals, however, tend to provide more comprehensive analyses, as they focus on both series of stops more often than multilingual studies. Moreover, they point to an interesting asymmetry between voiced and voiceless stops in which the voiced stopsFootnote3 seem to be more prone to CLI than the voiceless ones (e.g. Antoniou et al., Citation2010; Bless, Citation2015; Chionidou & Nicolaidis, Citation2015; Herd et al., Citation2015; Newlin-Łukowicz, Citation2014; Schwartz et al., Citation2020; Sučková, Citation2018). As far as research on Polish speakers is concerned, Zając (Citation2015) found that they experienced problems suppressing pre-voicing in voiced stops but managed to converge with aspirated voiceless plosives. This asymmetry between voiced and voiceless series of stops was also observed more recently by Schwartz (Citation2020) who examined VOT production in speakers’ L1 Polish and L2 English. Experiment 1 focused on L1 phonetic drift and included two groups of L2 English speakers – learners at B2 level of proficiency who underwent an extensive phonetic training in L2 and L1 Polish quasi-monolinguals who had approximately A1-A2 level of proficiency in English. The findings revealed that VOT values for both groups were almost identical for voiceless stops; however, the more proficient group exhibited shorter pre-voicing in the voiced series and fewer prevoiced items in general. Experiment 2 analysed speakers’ L2 English performance across two groups – Polish learners of L2 English at B1 level of proficiency and staff members in the English department at C2 level of proficiency in English, both of whom were phonetically trained. Again, the findings revealed an asymmetry in the realisation of the two series of stops. The VOT values for both groups were almost identical for voiceless stops; however, the more proficient group exhibited less and shorter pre-voicing in the voiced series. However, between-group differences were not found to be significant. The author interpreted the findings based on the framework of the Speech Learning Model (SLM; Flege, Citation1995), which posits three-way similarity classification between pairs of sounds into identical, similar and different with varied degrees of the resulting equivalence classification. It was suggested that the bidirectional CLI observed in the voiced stops may be indicative of these sounds being treated as equivalents in Polish and English, which means that the voiced stops in these languages were perceived as similar by the participants. It is worth noting that this tendency has also been reported for longitudinal data on L1 drift and L2 production. Wojtkowiak (Citation2022) analysed L1 and L2 productions of word-initial stops by three groups of L1 Polish L2 English speakers and a group of Polish functional monolinguals. L1 drift results showed that voiceless stops were rather unaffected by the intensive acquisition of L2 English, while the voiced category turned out to be more vulnerable to the influence of the foreign language. What is more, a comparison with L2 data revealed that participants must have formed a new category for voiceless stops in English that was separate from the Polish ones. On the other hand, voiced plosives were found to be more affected by the L2, which may mean that the sounds in the two languages were perceptually assimilated to a single, shared category (Wojtkowiak, Citation2022). The author accounts for the finding claiming that lenis stops are more vulnerable to CLI than the fortis ones due to their different phonological status (see Schwartz, Citation2020). This claim is embedded in the Onset Prominence framework, according to which aspiration in voiceless stops is a phonological feature ([fortis]), while pre-voicing is considered to be a phonetic detail.

Compared to the extensive body of literature on VOT acquisitionin L2, to date,this parameter has received considerably less attention from a multilingual perspective. Yet, with multilingualism being the norm in today’s world, it seems vital to examine more linguistically diverse groups of participants. There have been attempts to apply the explanatory frameworks put forth in the context of L3 morphosyntax to account for L3 phonological acquisition (see, e.g. Kopečková et al., Citation2023 for an overview); however, in the present contribution we refer only to the L2 status model by Bardel and Falk (Citation2007), as the most applicable one for the interpretation of the current data. On the whole, the existing L3 studies in this area seem to be rather limited, focusing mostly on the main source of CLI in the third language and pointing to L2 influence, combined L1-L2 effect or providing mixed results (e.g. Llama & López-Morelos, Citation2016; Tremblay, Citation2007). For example, Llama et al. (Citation2010) analysed L3 Spanish spoken by two mirror groups, i.e. L1 English L2 French and L1 French L2 English speakers to determine whether it is L2 status or linguistic typology that playsx a role in shaping VOT patterns in voiceless stops. The results demonstrated that the L2 status was the main predictor of L3 VOT values; however, there was also some evidencepointing to the interaction of L1 and L2 influence. Mixed results were also obtained by Wunder (Citation2010), who analysed voiceless stops produced by L1 German L2 English L3 Spanish speakers performing a reading task. The findings suggested either an L1 influence or a combined CLI stemming from both L1 and L2. In fact, in most cases, the data showed hybrid VOT values in L3 Spanish that could not be classified as either L1 or L2 influence. Wrembel (Citation2011) studied voiceless stops production by L1 Polish, L2 English, L3 French speakers, demonstrating that L2 English VOT was produced on a target, but L3 values were in-between those of Polish and English. These data suggest the co-existence of L2 status effect and L1 influence thus attesting combined CLI. In a further study Wrembel (Citation2015) revealed similar trends showing that L3 might be influenced by both the first and the second language. It was also concluded that this influence is gradual, structure-dependent and can only partially be accounted for by the existing models of L3 acquisition. Gabriel et al. (Citation2016) compared the L3 French VOT patterns of German/Mandarin-Chinese multilingual learners to two control groups of monolingual learners and found no significant differences; neither in the production of /t, d/ nor the learners’ perceived accent. The authors interpret these results as the lack of confirmation of any potential advantage of multilinguals when acquiring the phonology of an additional foreign language. However, the source of L1-based transfer was hard to determine since the selected background languages (German and Mandarin-Chinese) align in terms VOT target values. A more recent study by Amengual (Citation2021), however, demonstrated a slightly different trend in terms of possible cross-linguistic interactions. The author examined the production of /k/ by two groups of participants: English-Japanese bilinguals and L1 Spanish, L2 English, L3 Japanese speakers. The findings revealed that both the bilingual and trilingual speakers were able to maintain language specific VOT categories, however, only the latter showed significant differences between VOT values across languages.

VOT in multilinguals has also been investigated from a more holistic point of view, providing evidence also for regressive CLI. For example, Sypiańska (Citation2013) investigated the production of word-initial voiceless stops in L1 Polish L2 Danish L3 English speakers. She found combined CLI stemming from L1 and L2 to L3 VOT values, but also longer VOT values in L1 and L2, which pointed to the possibility of regressive CLI from the L3 to L1 and L2. Another important contribution was recently made by Nelson (Citation2022), who investigated regressive phonological CLI in voiceless stops produced by adolescents and adults speaking L1 German, L2 English, L3 Polish. The study explored the development of all three languages over four testing times. The author observed significant changes to both L1 and L2 over time in the adolescent group and relatively stable L1 and L2 systems in the adults group suggesting that the stability of background languages might depend on age, at least at a group level.

Surprisingly, only a handful of studies to date have investigated the voiced category of stops in L3 in a systematic way. From what has been established, however, it can be assumed that a similar asymmetry, as attested in the L2 data, will also be observed in L3. Liu (Citation2016) investigated VOT in bilabial stops /p/ and /b/ in L1 Mandarin – L2 English participants compared to L1 Mandarin – L2 English – L3 Spanish speakers. L3 learning turned out to influence the productions of the voiced stop in L1, as well as voiced and voiceless stops in L2. What is more, it was revealed that L3 learners maintained three separate systems for the production of the voiceless stop and one system for the production of L1 and L2 voiced stops, but a different one for L3. Gabriel et al. (Citation2018) examined word-initial fortis and lenis stops produced in L3 French by multilingual learners speaking Russian or Turkish as a heritage language alongside German, their dominant language. The results showed that compared with monolingual data, multilinguals produced voiceless stops closer to the target, but it was not the case for the voiced stops. It is explained that the learners might perceive aspiration as more salient than the presence or absence of prevoicing. On the other hand, slightly different results were reported by Geiss et al. (Citation2022) who analysed voiced and voiceless stops produced by Italian-German heritage speakers with L3 English. The findings pointed to separate VOT patterns in both series of stops in all three languages.

summarises the literature review regarding the multilingual acquisition of VOT. All in all, current evidence showsan asymmetry in the acquisition of the two series of stops in both L2 and L3 learning contexts. However, the L3 studies have remained quite narrow in focus so far dealing mostly with voiceless plosives and not taking into consideration all three languages and directions of CLI, nor the developmental aspects of L3 acquisition. To the best of our knowledge, no study to date has tackled all of the aforementioned aspects jointly. Therefore, the present contribution aims to bridge this gap and offer new insights by exploring longitudinally the acquisition of VOT in voiceless and voiced stops by trilinguals in all of their three languages in order to trace CLI patterns over the first year of learning a new L3.

Table 1. Summary of studies investigating multilingual acquisition of VOT.

VOT in Polish, English and Norwegian

As far as the languages under investigation are concerned, they differ considerably in terms of their VOT characteristics. Polish is a true voicing language, which means that it has prevoicing in voiced stops (/b, d, g/) and short-lag VOT in voiceless stops (/p, t, k/) (e.g. Jassem, Citation2003; Keating et al., Citation1981). The occurrence of prevoicing in Polish voiced stops is high, for example, Sypiańska (Citation2021) reported 100% of prevoiced items in Polish control group, while in Wojtkowiak (Citation2022) fully prevoiced items constituted over 95% of the tokens. English, on the other hand, is an aspirating language that has short-lag VOT invoiced stops (/b, d, g/) and long-lag VOT in voiceless plosives (/p, t, k/) (e.g. Docherty, Citation1992; Lisker & Abramson, Citation1964). It is important to note that some sources report prevoicing in English voiced stops. However, its occurrence is rather limited, for example Docherty (Citation1992) reports prevoicing in 7% of the items, most of which came from one speaker. For this reason, we still treat English as exceptional for its prevoicing status compared to the remaining two languages. Considering Norwegian, this language has not received as much attention in the literature in terms of VOT as English and Polish. Nevertheless, Czarnecki (Citation2016) claims that the purely phonological difference between /p, t, k/ and /b, d, g/ pertains to aspiration or lack thereof, which might suggest that it is an aspirating language. However, the measurements taken by Halvorsen (Citation1998) as well as Ringen and van Dommelen (Citation2013) suggest the presence of voicing lead in the lenis stops in about 80% and 40% of the tokens, respectively, as well as aspiration in the fortis series. Based on that, in the current paper Norwegian is treated as a language with both prevoicing and aspiration.

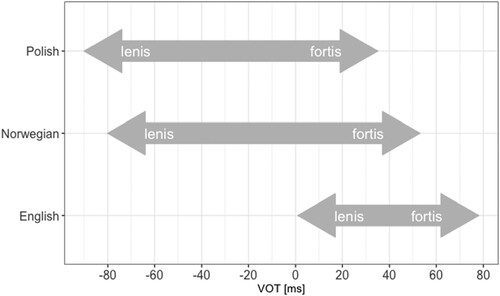

shows approximate VOT ranges of stops in the three languages under investigation. Yet, it is important to note that due to differences in methodologies, i.e. the durations having been measured in various contexts and by different researchers, the cross-linguistic comparison should be approached with some caution. For this reason, the values presented in reflect general VOT durational tendencies for the plosive sounds in the three languages generated from the overview of previous literature. Furthermore, specific baseline values are not provided as reference points in the subsequent analysis as participants investigated longitudinally are treated as their own controls (cf. e.g. Cabrelli Amaro, Citation2012).

A potential learning scenario for L1 Polish L2 English L3 Norwegian would be as follows: as native speakers of a voicing language (such as Polish), learners acquiring an aspirating language (such as English) as L2 would need to readjust their phonetic realisation of fortis/lenis distinction in such a way that short-lag voiceless stops would be realised as long-lag and, on the other hand, in voiced stops, prevoicing would need to be generally suppressed (with a potential caveat that English and Norwegian voiced stops are sometimes realised inconsistently in this regard). While learning a language with both prevoicing and aspiration (as in the case of Norwegian) as L3, learners would need to rely on their L1 to maintain prevoicing in the voiced stops, and on their L2 to realise long-lag voiceless stops.

The current study

Aim

The aim of this study is to analyse the production of plosive sounds by L1 Polish – L2 English – L3 Norwegian speakers. In particular, the goal is to trace the development of VOT acquisition in voiceless and voiced stops (/p, t, k/ and /b, d, g/) of all three languages (Polish, English and Norwegian) produced by novice L3 learners throughout their first year of learning the third language across three testing times. In each session, the participants were recorded reading word lists with stop sounds (voiced and voiceless) placed in stressed onset positions followed by a vowel in all three languages. The goal was to explore possible cross-linguistic interactions in the oral productions of multilingual speakers with a focus on both progressive and regressive CLI.

RQs and hypotheses

The following research questions were posed in order to investigate VOT development and possible cross-linguistic interactions in L3 learners:

RQ1: What sources of CLI can be traced in the VOT patterns in the three languages?

In relation to the first research question, predictions were formed based on certain factors that were attested in the literature for determining types of CLI. From the perspective of second language acquisition research, the most prevalent source of influence was ascribed to the first language. L1 status cannot, thus, be excluded from the current predictions, as it is assumed to rely on well-established neuro-motor articulatory routines in the first language. Taking into consideration typological (genetic) proximity, English and Norwegian are Germanic languages, thus we would expect more CLI between L2 and L3 than either of them and Polish which is a Slavic language. If we allow for the L2 status effect (see e.g. Bardel & Falk, Citation2007), more CLI could be predicted between L2 and L3, due to similar (formal) settings and routes of acquisition as foreign languages, as opposed to the naturalistically acquired L1. On the other hand, based on purely phonological similarity between the stops in the three languages, we could expect a twofold scenario. Since the voiced series /b, d, g/ exhibits closer similarity between L1 Polish and L3 Norwegian, we predict more CLI to occur between L1 and L3 in this category of stops. Moreover, as the voiceless series /p, t, k/ demonstrate closer proximity between L2 English and L3 Norwegian, bidirectional CLI should be attested between L2 and L3. Additionally, taking into account the assumptions of the Phonological Permeability Hypothesis (PPH, Cabrelli & Rothman, Citation2010), according to which the L1 system is more stable than the L2 that is acquired later in life, we do not expect major changes to affect the L1, but we foresee more CLI from L3 to L2.

RQ2: How does the acquisition of VOT in trilinguals change over time in the respective languages?

With regard to the second research question, we divided our predictions according to the three languages under investigation. In L3 Norwegian, we foresee the change in VOT values towards more target-like values, as a function of increasing language proficiency in this emerging phonological system as well as the frequency of exposure to the L3 input (cf. Dziubalska-Kołaczyk & Wrembel, Citation2024 forthcoming). On the other hand, L2 English is the language that the participants are already quite proficient in, thus it constitutes a more established system. Consequently, we predict that this language may be less prone to changes (cf. Wrembel et al., Citation2022), so that participants will produce stops with VOT close to the target English values at T1 and that these values will not change considerably over time. If any, the change would be observed in voiced stops, as this category is more affected by CLI even in proficient learners (e.g. Schwartz, Citation2020). As far as L1 Polish is concerned, there may be a potential L1 drift effect as a result of the L2/L3 frequency of use (cf. Chang, Citation2013; Wojtkowiak, Citation2022). Overall predictions of the degree of development in the three languages under investigation stem from their varying status, as L1, L2, L3. Because of that we expect the greatest changes towards target-like realisation in the L3 (due to intense exposure and sensitivity to change); moderate changes in the L2 (due to its relative stability and the L2 status which predicts some impact of the newly learnt L3), and little or no changes in the L1 (due to its being acquired the earliest as the first language).

RQ3: Do voiced and voiceless plosives exhibit similar trends across languages in the multilinguals’ repertoire?

With respect to the third research question, based on previous research (e.g. Cal & Wrembel, Citation2022 Wojtkowiak, Citation2022;), we predict separate, language-specific patterns of VOT acquisition in the voiceless stops. That is, we expect participants to maintain VOT values in their three languages specific to each respective language, which means short-lag VOT in their L1 and long-lag VOT in L2 and L3. Moreover, the voiced series /b, d, g/ are hypothesised to be more vulnerable to CLI than voiceless /p, t, k/ due to their different phonological status according to the Onset Prominence framework and predictions (see Schwartz, Citation2020).

All the predicted scenarios of CLI patterns are summarised in .

Table 2. Summary of CLI predictions for fortis and lenis stops.

Methods

Participants

The participants of this longitudinal study included 12 L1 Polish speakers, who had been learning English as their L2 and had recently started learning L3 Norwegian extensively as part of a Norwegian Studies programme at two Polish universities. The original pool of participants was larger (N = 24), yet the number was reduced over the period of investigation (due to drop-out and various exclusion criteria), thus we report only those participants with a complete data set for all the testing times. The group consisted of 8 females and 4 males, whose mean age was 19.9 years old (SD = 0.93).

The participants were asked to fill in the Language History Questionnaire (LHQ; Li et al., Citation2020) in order to obtain information about their language learning history and use. Their mean age of onset in L2 English and L3 Norwegian was 8.2 (SD = 4.2) and 19 (SD = 1) years, respectively. They were exposed to Norwegian extensively by taking part in Practical Norwegian classes as part of their study programme at a university. The undergraduate programme focused on literature, linguistics, history and practical knowledge of Norwegian.Footnote4 The Practical Norwegian classes included speaking, writing, listening as well as pronunciation. They were conducted nearly entirely in Norwegian by Polish university lecturers highly proficient in Norwegian, speaking what can be broadly described as Eastern Norwegian. At the first testing time, the participants had received approximately 80 h of intensive Norwegian instruction, followed by 195 h at the second testing time, and 300 at the third testing time. Before they attended the Norwegian programme, the participants had had limited, almost none, contact with L3 Norwegian, as declared in the LHQ. As far as L2 English is concerned, they reported exposure through social media and other media platforms, especially streaming services. Their study programme did not involve any English classes during the first year of studies. Additionally, they claimed not to be proficient in or use any other foreign languages apart from those under investigation at the time of the study.

Except for the LHQ, the participants also completed proficiency tests in both of their foreign languages. Their proficiency in English was measured by means of the LexTALE testFootnote5 (Lemhöfer & Broersma, Citation2012). Norwegian proficiency was measured using an adapted version of the Norwegian placement test that assessed proficiency up to the A2 level. Based on the grading criteria the participants were classified as intermediate (approximately B2 level) learners of L2 English and beginner (A1) learners of L3 Norwegian. summarises the participants’ profile data.

Table 3. Participants’ profile data.

Procedure

All in all, the participants took part in three testing times that included three separate sessions for all three languages under investigation. The first testing time (T1) was conducted after 8 weeks of learning the L3. The second testing time (T2) was carried out after the first semester of learning the L3, i.e. after approximately 5 months. The third testing time (T3) took place after two semesters, that is, after 7 months of learning L3 Norwegian.

Among a battery of production and perception tests, the participants performed reading tasks of three word lists separately for each language. The stimuli included isolated one-syllable words with stop sounds (fortis and lenis) placed in stressed onset positions followed by a vowel. The words with fortis and lenis stops constituted minimal pairs that were presented in random order. All in all, the participants read three language lists with 30 token words for Polish (5 per stop), 48 for English (8 per stop) and 66 for Norwegian (11 per stop). The number of selected tokens depended on possible vowel contexts. The participants were presented with the stimuli on a computer screen and were asked to read the words as they appeared on the screen. Recording sessions were carried out in the language blocks on separate consecutive days to avoid language mixing. Firstly, the participants took part in the Norwegian block, then English and, at the end, Polish. The order of experimental tasks remained unchanged across the blocks. Recordings were conducted in a sound-treated booth or a quiet room using Shure SM-35 unidirectional cardioid head-worn condenser microphone and Marantz PMD620 recording device. The speech rate of individual participants was controlled in a twofold manner: each individual token item was placed at a separate slide and the experimenter controlled for the displaying the slides at a steady pace of delivery. The procedure remained unchanged across all three testing times.

The obtained recordings were then force-aligned using WebMAUS (Kisler et al., Citation2017), and VOT boundaries were manually corrected in Praat (Boersma & Weenink, Citation2021). The measurements for voiced stops included prevoicing which was annotated from the first noticeable pulse of voicing to the release of the closure. The burst and release noise were not included. In the voiceless stops, the measurements focused on the duration of positive VOT, which was marked from the release of the closure until the onset of the subsequent vowel. All boundaries were placed at zero-crossings. The VOT durations were extracted with the use of a Praat script (Lennes, Citation2002).

Results

This section presents the results of VOT measurements in word-initial fortis and lenis stops (/p, t, k/ and /b, d, g/) in the three languages under investigation (L1 Polish, L2 English, L3 Norwegian) across three testing times (T1, T2, T3). Firstly, overall descriptive statistics are provided. Next, VOT measurements for the three languages are reported. Thereafter, the obtained results are compared across the three testing times. After that, a comparative analysis of the VOT values in the voiced and voiceless stops is presented. Finally, an analysis of individual trajectories of VOT development is offered.

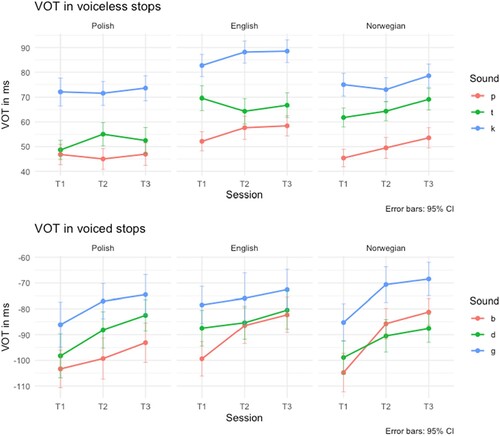

Out of the total 5400 tokens, 528 were discarded from the analysis due to them being realised without prevoicing or mispronounced. Thus, the total number of tokens, analysed for VOT durations, was 4872. Items lacking prevoicing are discussed later in this section. shows mean VOT values (in ms) for each stop consonant across the three languages and testing times. As can be seen, VOT values of voiceless stops have overall the shortest lag in L1 Polish and the longest lag in L2 English, while the values for L3 Norwegian stops seem to fall in-between the two. In the voiced stops, L1 Polish exhibited the longest pre-voicing values in /b/ and /g/ and L3 Norwegian in /d/, while the shortest pre-voicing was found in L2 English.

Table 4. Mean VOT values (in ms) and standard deviation (in brackets) for each stop consonant across three languages and testing times.

A logistic mixed-effects regression model was run in R (R Core Team, Citation2024) using a partially Baesian method within blme package (Chung et al., Citation2013) to avoid singularity. VOT values were included as the dependent variable and Sound, Language and Session were added as fixed factors. The model also included interaction between Sound, Language and Session as well as by-participant and by-item random slopes for Session. Post-hoc analyses were carried out with the use of the emmeans package (Lenth, Citation2023) by applying Tukey adjustments to compare a family of three estimates. This package was also used to calculate effect sizes. The model specification was as follows: VOT ∼ Sound*Language*Session + (Session|Participant) + (Session|Item). Obtained fixed effects are presented in . The output of the model is provided in the Appendix.

Table 5. Fixed effects generated in the statistical analysis.

The results of the analysis pointed to statistically significant main effects of Sound (F = 2355.93, p < .001), Session (F = 8.90, p = .005) and Language (F = 15.49, p < .001), along with a Sound by Session interaction (F = 2.06, p < .001).

A post hoc analysis for language revealed statistically significant differences between all three languages, that is: L2 English – L3 Norwegian (z = 3.011, p = .007), L2 English – L1 Polish (z = 5.555, p < .001) and L3 Norwegian – L1 Polish (z = 3.265, p = .003).

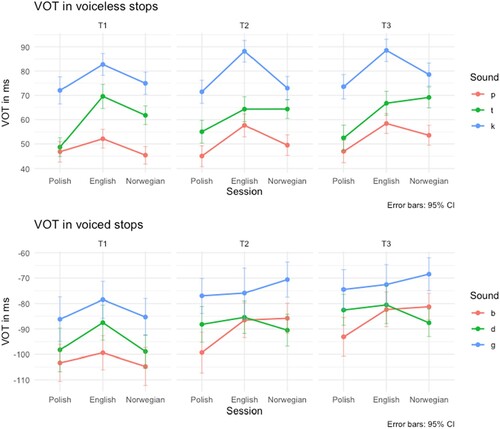

Mean VOT values generated across the three testing times are visualised in . The data obtained from the first testing time (T1)shows that VOT values in L3 Norwegian voiceless stops fall in-between those of L1 Polish and L2 English, while in the voiced series, they seem to approximate L1 Polish values. The values for L2 English are the shortest. In the second testing time (T2), L2 English values turned out to be the longest in /p/ and /k/, while L1 Polish and L3 Norwegian VOT values appear rather comparable. For /t/, L2 English and L3 Norwegian approximate one another, while Polish VOT remains the shortest. For the bilabial voiced plosive /b/, L1 Polish values turned out to be the longest, while in the rest of the sounds they are rather comparable. As far as the third testing time (T3) is concerned, it can clearly be observed that VOT values are considerably shorter in Polish than in L3 Norwegian and L2 English, which exhibits the longest lag for voiceless stops. The values generated for voiced stops seem to be rather comparable, with L1 Polish yielding the longest mean VOT in /b/ and L3 Norwegian in /d/. Pairwise comparisons across testing sessions pointed to statistically significant differences only between T1 and T3 (z = −4.082, p < .001).

Figure 2. Mean VOT values of voiceless and voiced plosives in L1 Polish, L2 English, L3 Norwegian across the three testing times (T1-T3).

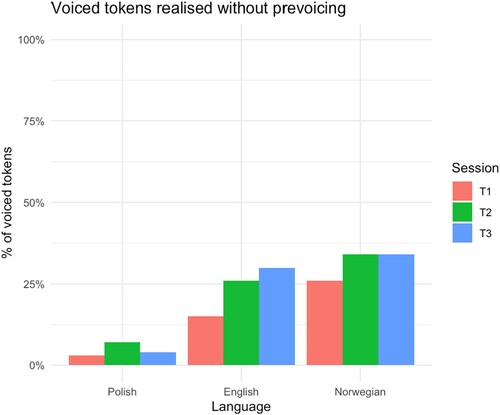

shows mean VOT values of voiceless and voiced plosives produced across the three testing times in L1 Polish, L2 English, L3 Norwegian. What can be seen is that, overall, in the voiceless series of stops, there is a tendency for VOT to increase with time, which is especially visible in L2 English and L3 Norwegian /p/ and /k/. On the other hand, in the voiced series, there is a decrease in prevoicing values with time in all three languages. What is more, as shown in , the number of unvoiced items increased considerably with time in L2 English and L3 Norwegian, but not in L1 Polish.

Figure 3. Mean VOT values of voiceless and voiced plosives in three testing times (T1-T3) across the three languages (L1 Polish, L2 English, L3 Norwegian).

A post hoc analysis of the interaction between sounds and testing sessions showed that only the voiced series of stops differed significantly across three testing times. More specifically, the differences between T1 and T2 were found for /b/ (z = −3.389, p = .002) and /g/ (z = −2.662, p = .021), while the difference between T1 and T3 was attested for all three voiced stops, namely /b/ (z = −5.911 < .001), /d/ (z = −3.681, p < .001) and /g/ (z = −3.908, p = <.001). This suggests that VOT values in these sounds generally increased over time, that is, prevoicing became shorter.

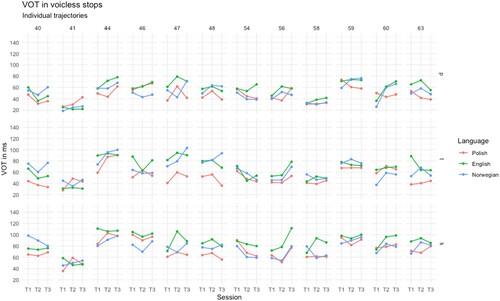

To provide a more nuanced understanding of the process of acquisition, we zoomed into individual variation by analysing separate trajectories of development, on the one hand, to see interactions between the three languages in particular individuals and, on the other hand, to observe the development over time. and demonstrate individual trajectories of VOT development of voiceless and voiced stops across the three testing times in the three languages under investigation. As can be seen, the plots point to a considerable individual variation, yet some stable patterns can be identified based on the data. Taking into account the relationships between languages, in the voiceless series some participants maintain more unified VOT values across languages (i.e. participants 41, 58 and 59), while others produce more distinct VOT values in their three languages (i.e. participants 47 and 63). What can also be noticed is that in some of the cases, foreign languages (L2 English and L3 Norwegian) are produced in a similar manner that is divergent from L1 Polish. This is visible, for example, in participants 46 (in /p/ and /k/) or 60 (in /p/). The voiced series appears to be more diverse, but still similar patterns of VOT trajectories can be identified. That is, unified VOT values across languages can be observed, for example in participants 47, 48 (in /d/ and /g/), 56 (in /d/) or 63 (in /d/), while more distinct VOT values in the three languages can be seen in participants 40, 41 or 60. Participant 44 maintained different VOT values for their foreign languages compared to L1 Polish. As far as the development over time is concerned, in the voiceless series some of the participants experienced an upward trend in the VOT values increasing with time in all three languages (e.g. participant 44 in /p/ and /t/, 56 in /t/ and /k/) or in the foreign ones (e.g. participant 60 in /p/). On the contrary, a downward trend in VOT durations was also attested (e.g. participant 54). Interestingly, a number of participants experienced the greatest downturn or upturn at T2.

Discussion

The aim of this paper was to analyse the production of plosive sounds by L1 Polish, L2 English, L3 Norwegian speakers and potential patterns of cross-linguistic interactions over time. Our particular objective was to trace the development of VOT acquisition in voiceless and voiced stops (/p, t, k/ and /b, d, g/) in all three languages (Polish, English and Norwegian) produced by novice L3 learners throughout their first year of learning of the third language across three testing times. To this end, three research questions were posed.

The first research question dealt with sources of CLI that could be traced for VOT patterns in the three languages. Predictions were formed based on selected factors that were attested in the literature for determining CLI directionality (cf. Puig-Mayenco et al. Citation2020 for a systematic overview of morphosyntactic transfer studies in third language acquisition), including typological proximity, L2 status factor (see e.g. Bardel & Falk, Citation2007), phonological similarity between the language systems and PPH (Cabrelli & Rothman, Citation2010). The present results do not confirm any of the predictions made with regards to potential sources of CLI. In fact, the VOT production patterns differed significantly across the three languages, thus indicating that multilingual learners regard the three systems as distinct. This finding is in line with previous research (Amengual, Citation2021; Geiss et al., Citation2022; Liu, Citation2016) which also attested separate language systems. Although Amengual’s study focused only on a velar plosive /k/, it clearly showed that language-specific VOT categories were maintained in multilingual learners to a higher degree than in bilinguals. What is more, the study by Geiss et al. (Citation2022) that analysed the production of voiced and voiceless stop sounds also indicated separate VOT patterns in both series of stops in all three languages pointing to the possibility of bilingual advantage. In turn, our participants were rather advanced in their second language (English) which might have led to a different realisation of VOT in their newly acquired L3.

The second question in this study sought to determine how VOT patterns in trilinguals change over time. We expected VOT durations in L3 Norwegian stops to change towards more target-like values, as a function of increasing language proficiency in this emerging phonological system as well as the frequency of exposure to the L3 input. We did not foresee any major changes in the L2 English stops because of the participants’ rather advanced proficiency in this language, but if any, we expected more change to affect the lenis series, which would be in line with the existing literature (e.g. Gabriel et al., Citation2018; Schwartz, Citation2020; Schwartz et al., Citation2020; Wojtkowiak, Citation2022). For L1 Polish we predicted a potential L1 drift effect as a result of the L2/L3 frequency of use (e.g. Wojtkowiak, Citation2022). The results, however, did not point to an interaction between Language and Session. Thus, we cannot explicitly state how particular languages were affected over time, yet we witness a change in progress between T1 and T3 in the overall system of multilingual learners. On the whole, we attested differences in VOT realisation between T1 and T3, which can be interpreted as indicating a potential influence of an additional language (i.e. L3) being added to the multilingual system in the VOT production patterns. Although we found that VOT values are significantly different in all three languages, it can be stated that the whole multilingual system changed with time in one direction, especially in terms of voiced stops, where we observed shortening of prevoicing across times. Adding Norwegian as a third language into the system might have caused that the participants associated it with L2 English (a voicing language) due to their typological proximity and as a result of the L2 status effect. This, in turn, could have led to the decrease of prevoicing in all three languages, as a gradual influence of L3 due to increasing exposure to this language with time. The overall decrease in the length of prevoicing shows that the multilingual system develops from L1 Polish-like values, towards more L2 English-like realisations. This is also visible in the number of unvoiced items (i.e. without prevoicing) which increased considerably with time, especially in L2 English and L3 Norwegian, suggesting more English-like realisation of the two languages. This attested dynamic change affecting the multilinguals’ system as a whole might be interpreted as a potential manifestation of a global language entity, as proposed by Sypiańska (Citation2017). The author postulates the existence of a global language system treating it as one entity, thus the dynamic shifts in system may impact all its component languages in a similar manner. In our case the influence is holistic and tacit, departing from a typical cross-linguistic interaction frequently reported in L3 phonological acquisition research.

The third research question aimed to determine whether fortis and lenis plosives exhibit similar trends across the languages in the multilinguals’ repertoire. Based on previous research outcomes (e.g. Cal & Wrembel, Citation2022; Wojtkowiak, Citation2022), we expected to observe separate, language-specific patterns of VOT acquisition in the voiceless stops and more CLI in the voiced series. The present findings support this prediction, but only to some extent. Indeed, the interaction between sound and session pointed to significant differences between sessions in all three voiced sounds (/b, d, g/), but not in the voiceless ones (/p, t, k/). It was shown that the voiced plosives changed significantly with time, by means of shortening of prevoicing across the three sessions, while there were no significant changes in the voiceless series. What is more, the number of unvoiced items decreased with time. Previous literature also attested similar asymmetry (e.g. Gabriel et al., Citation2018 Schwartz, Citation2020; Schwartz et al., Citation2020; Wojtkowiak, Citation2022), where both voiceless and voiced series were affected by CLI in a different manner. This might be because prevoicing is a less salient feature than aspiration and, therefore, the participants did not hear the difference between voiced stops in the three languages. Consequently, these sounds tend to be less stable and more prone to changes during the process of L3 acquisition.

Notwithstanding the novelty of the contribution, there are some limitations that need to be mentioned. First of all, the major limitation of this study is a reduced pool of participants, due to a considerable drop-out rate in the original number at T1, which was the effect of the longitudinal investigation. A low number of participants, inevitably linked with longitudinal investigations in L3 acquisition, is also a limitation when it comes to fitting statistical models that include a three-way interaction. Another limitation was related to the task type as the participants read a list of words consisting of stop consonants in the stressed onset position followed by a vowel, as it has been the most frequent practice in previous related studies. However, free speech elicitation tasks might reflect the actual production performance with more ecological validity, yet lesser control over the target tokens.

Conclusion

The present investigation analysed the production of plosive sounds by L1 Polish, L2 English, L3 Norwegian speakers by tracing the development of VOT acquisition in voiceless and voiced stops in all three languages produced by novice L3 learners throughout their first year of learning of the third language. The paper investigated cross-linguistic interactions in their oral productions and the developmental trajectory of L1, L2 and L3 speech over three testing times. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first such longitudinal study investigating the voiced and voiceless stops in all three languages over time. The study revealed that the participants maintained language-specific VOT patterns in all three languages. What is more, it showed a change in VOT production patterns over time in the voiced series of stops, namely shortening of or even loosing prevoicing. Last but not least, the study confirmed previous findings regarding the asymmetry between voiced and voiceless stops, as both of the series turned out to be affected by CLI in a different manner.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this paper, the authors use the terms bilinguals and L2 learners, as well as multilinguals and L3 learners interchangeably.

2 In this paper, exposure to L3 Norwegian that lasted no more than 9 months is still considered by authors to be a recent exposure to the foreign language.

3 As suggested by the reviewer, to make the terminology more consistent, we tried to use the voiceless/voiced distinction to refer to phonetic voicing, and fortis/lenis to refer to phonological voicing.

4 Theoretical subjects, like Norwegian phonetics and phonology, Norwegian literature and introduction to linguistics, were taught in Polish. The pronunciation course covering both segmental and suprasegmental features was supplemented by a theoretical course in phonetics and phonology (30h/semester). The model accent taught in these classes was Eastern Norwegian.

5 We used LexTALE as a proxy to proficiency being aware that it should be used with caution (cf. Puig-Mayenco et al., Citation2023). It is important to stress that proficiency is not used as a variable in the study.

References

- Amengual, M. (2021). The acoustic realization of language-specific phonological categories despite dynamic cross-linguistic influence in bilingual and trilingual speech. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 149(2), 1271–1284. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0003559

- Antoniou, M., Best, C. T., Tyler, M. D., & Kroos, C. (2010). Language context elicits native-like stop voicing in early bilinguals’ productions in both L1 and L2. Journal of Phonetics, 38(4), 640–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wocn.2010.09.005

- Bardel, C., & Falk, Y. (2007). The role of the second language in third language acquisition: the case of Germanic syntax. Second Language Research, 23, 459–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658307080557

- Bless, M. (2015). Interference in early acquisition Dutch-English bilinguals: A phonetic examination of voice onset time in Dutch and English bilabial plosives. [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of Amsterdam.

- Boersma, P., & Weenink, D. (2021). Praat: Doing phonetics by computer [Computer software]. Version 6.1.50, retrieved 22 Jan 2021 from http://praat.org.

- Cabrelli, J., & Rothman, J. (2010). On L3 acquisition and phonological permeability: A new test case for debates on the mental representation of Non-native phonological systems. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 48(2–3), 275–296.

- Cabrelli Amaro, J. (2012). L3 Phonology: An understudied domain. In J. Cabrelli Amaro, S. Flynn, & J. Rothman (Eds.), Third language acquisition in adulthood (pp. 33–60). John Benjamins.

- Cal, Z., & Wrembel, M. (2022). Exploring the patterns of cross-linguistic influence in the acquisition of stops by L1 Polish – L2 English – L3 Norwegian speakers [Paper presentation]. The 10th International Symposium on the Acquisition of Second Language Speech (New sounds 2022), Barcelona, Spain.

- Chang, C. B. (2013). A novelty effect in the phonetic drift of the native language. Journal of Phonetics, 41(6), 520–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wocn.2013.09.006

- Chang, C. B. (2019). Phonetic drift. In M. S. Schmid & B. Köpke (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of language attrition (pp. 190–203). Oxford University Press.

- Chionidou, A., & Nicolaidis, K. (2015). Voice onset time in bilingual Greek-German children. Proceedings of the 18th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences. Glasgow, UK.

- Chung, Y., Rabe-Hesketh, S., Dorie, V., Gelman, A., & Liu, J. (2013). A nondegenerate penalized likelihood estimator for variance parameters in multilevel models. Psychometrika, 78(4), 685–709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-013-9328-2

- Czarnecki, P. (2016). The Phonology of Quantity in Icelandic and Norwegian. WydziałNeofilologii UAM w Poznaniu.

- Docherty, G. (1992). The timing of voicing in British English obstruents. de Gruyer.

- Dziubalska-Kołaczyk, K., & Wrembel, M. (2024, forthcoming). A revised natural growth theory of acquisition: Evidence from L3 phonology. In E. Babatsouli (Ed.), Multilingual acquisition and learning: An ecosystemic view to diversity. John Benjamins.

- Flege, J. E. (1987). The production of ‘new’ and ‘similar’ phones in a foreign language: Evidence for the effect of equivalence classification. Journal of Phonetics, 15(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0095-4470(19)30537-6

- Flege, J. E. (1991). Age of learning affects the authenticity of voice-onset time (VOT) in stop consonants produced in a second language. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 89(1), 395–411. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.400473

- Flege, J. E. (1995). Second language speech learning: Theory, findings, and problems. In W. Strange (Ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-language research (pp. 233–276). York Press.

- Flege, J. E., & Eefting, W. (1987). Cross-language switching in stop consonant perception and production by Dutch speakers of English. Speech Communication, 6(3), 185–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-6393(87)90025-2

- Flege, J. E., & Hillenbrand, J. (1984). Limits on pronunciation accuracy in adult foreign language speech production. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 76(3), 708–721. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.391257

- Gabriel, C., Krause, M., & Dittmers, T. (2018). VOT production in multilingual learners of French as a foreign language: Cross-linguistic influence from the heritage languages Russian and Turkish. Revue française de linguistiqueappliquée, 1(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.3917/rfla.231.0059

- Gabriel, C., Kupisch, T., & Seoudy, J. (2016). Vot in French as a foreign language: A production and PerceptionStudy with mono- and multilingual learners (German/mandarin-Chinese). In C. Gabriel, T. Kupisch, & J. Seoudy (Eds.), Shs Web of conferences (Vol. 27, pp. 1–14). EDP Sciences.

- Geiss, M., Gumbsheimer, S., Lloyd-Smith, A., Schmid, S., & Kupisch, T. (2022). Voice onset time in multilingual speakers: Italian heritage speakers in Germany with L3 English. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 44(2), 435–459. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263121000280

- Halvorsen, B. (1998). Timing relations in Norwegian stops. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Bergen.

- Hansen Edwards, J. G., & Zampini, M. L. (Eds) (2008). Phonology and second language Acquisition. John Benjamins.

- Hazan, V. L., & Boulakia, G. (1993). Perception and production of a voicing contrast by French-English bilinguals. Language and Speech, 36(1), 17–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/002383099303600102

- Herd, W., Walden, R., Knight, W., & Alexander, S. (2015). Phonetic drift in a first language dominant environment. Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics, 23(1), 060005. https://doi.org/10.1121/2.0000100

- Jassem, W. (2003). Polish. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 33(1), 103–107. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100303001191

- Keating, P., Mikoś, M., & Ganong III, W. (1981). A cross-language study of range of VOT in the perception of stop consonant voicing. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 70(5), 1260–1271. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.387139

- Kisler, T., Reichel, U. D., & Schiel, F. (2017). Multilingual processing of speech via web services. Computer Speech & Language, 45, 326–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csl.2017.01.005

- Kopečková, R., Gut, U., Wrembel, M., & Balas, A. (2023). Phonological cross-linguistic influence at the initial stages of L3 acquisition. Second Language Research, 39(4), 1107–1131. https://doi.org/10.1177/02676583221123994

- Lemhöfer, K., & Broersma, M. (2012). Introducing LexTALE: A quick and valid Lexical Test for advanced learners of English. Behavior Research Methods, 44(2), 325–343. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-011-0146-0

- Lennes, M. (2002). Praat script.

- Lenth, R. V. (2023). emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R package version 1.8.8.

- Li, P., Zhang, F., Yu, A., & Zhao, X. (2020). Language History Questionnaire (LHQ3): An enhanced tool for assessing multilingual experience. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 23(5), 938–944. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728918001153

- Lisker, L., & Abramson, A. (1964). A cross-language study of voicing in initial stops. Word, 20(3), 384–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/00437956.1964.11659830

- Liu, Z. (2016). Exploring cross-linguistic influence: Perception and production of L1, L2 and L3 bilabial stops by mandarin Chinese speakers. [Master’s thesis. UniversitatAutònoma de Barcelona].

- Llama, R., Cardoso, W., & Collins, L. (2010). The influence of language distance and language status on the acquisition of L3 phonology. International Journal of Multilingualism, 7(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790710902972255

- Llama, R., & López-Morelos, L. P. (2016). VOT production by Spanish heritage speakers in a trilingual context. International Journal of Multilingualism, 13(4), 444–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2016.1217602

- Nelson, C. (2022). Do a learner’s background languages change with increasing exposure to L3? Comparing the multilingual phonological development of adolescents and adults. Languages, 7(2), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020078

- Newlin-Łukowicz, L. (2014). From interference to transfer in language contact: Variation in voice onset time. Language Variation and Change, 26(3), 359–385. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394514000167

- Puig-Mayenco, E., Chaouch-Orozco, A., Liu, H., & Martín-Villena, F. (2023). The LexTALE as a measure of L2 global proficiency: A cautionary tale based on a partial replication of Lemhöfer and Broersma (2012). Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 13(3), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.22048.pui

- Puig-Mayenco, E., González Alonso, J., & Rothman, J. (2020). A systematic review of transfer studies in third language acquisition. Second Language Research, 36(1), 31–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658318809147

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Ringen, C., & van Dommelen, W. A. (2013). Quantity and laryngeal contrasts in Norwegian. Journal of Phonetics, 41(6), 479–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wocn.2013.09.001

- Schwartz, G. (2020). Asymmetrical cross-language phonetic interaction: Phonological implications. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 12(2), 103–132. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.19092.sch

- Schwartz, G., Wojtkowiak, E., & Dzierla, J. (2020). Laryngeal phonology and asymmetrical cross-language phonetic influence. In M. Wrembel, A. Kiełkiewicz-Janowiak, & P. Gąsiorowski (Eds.), Approaches to the study of sound structure and speech: interdisciplinary work in honour of Katarzyna Dziubalska-Kołaczyk (pp. 316–326). Routledge.

- Sučková, M. (2018). First language attrition and maintenance in the accents of native speakers of English living in the Czech Republic [Paper presentation]. The 12th conference on native and non-native accents of English (Accents 2018), Łódź, Poland.

- Sypiańska, J. (2013). Quantity and quality of language use and L1 attrition of Polish due to L2 Danish and L3 English. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań.

- Sypiańska, J. (2013). Quantity and quality of language use and L1 attrition of Polish due to L2 Danish and L3 English [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Adam Mickiewicz University.

- Sypiańska, J. (2017). Cross-linguistic influence in bilinguals and multilinguals. Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM.

- Sypiańska, J. (2021). Production of voice onset time (VOT) by senior Polish learners of English. Open Linguistics, 7(1), 316–330. http://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2021-0016

- Thornburgh, D. F., & Ryalls, J. F. (1998). Voice onset time in Spanish-English bilinguals: early versus late learners of English. Journal of Communication Disorders, 31(3), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9924(97)00053-1

- Tremblay, M. C. (2007). L2 influence on L3 pronunciation: Native-like VOT in the L3 Japanese of English-French bilinguals. [Paper presentation]. The Satellite Workshop of ICPhS XVI, Freiburg, Germany.

- Williams, L. (1977). The voicing contrast in Spanish. Journal of Phonetics, 5(2), 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0095-4470(19)31127-1

- Wojtkowiak, E. (2022). L1 phonetic drift in the speech of Polish learners of English: Phonological implications. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań.

- Wrembel, M. (2011). Cross-linguistic influence in third language acquisition of voice onset time. In Wai-Sum Lee, & Eric Zee (Eds.), Proceedings of the 17th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (pp. 2157–2160). City University of Hong Kong.

- Wrembel, M. (2015). In search of a new perspective: Cross-linguistic influence in the acquisition of third language phonology. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM.

- Wrembel, M., Gut, U., Kopečková, R., & Balas, A. (2022). The relationship between the perception and production of L2 and L3 rhotics in young multilinguals; An exploratory cross-linguistic study. International Journal of Multilingualism, 21(1), 92–111.

- Wunder, E. M. (2010). Phonological cross-linguistic influence in third or additional language acquisition. Proceedings of 6th New Sounds, 2010, 566–571.

- Zając, M. (2015). Phonetic convergence in the speech of Polish learners of English. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Łódź.