Abstract

On March 17, 2010, the United States Federal Communications Commission identified broadband as “the great infrastructure challenge of the early twenty-first century.” One month earlier, on February 10, 2010, in anticipation of the FCC's announcement, Google announced its intent to build ultra-high-speed broadband networks across the United States to serve as a model for overcoming this challenge. Since then, Google Fiber, as it is called, has succeeded in being recognized as a model for other communities interested in establishing ultra-high-speed broadband infrastructure. This article serves as an analysis of the political economic consequences of this particular configuration of broadband infrastructure, and argues that Google Fiber operates as a mechanism of flexible capital whereby the emphases on short- over long-term relationships, meritocracy over craftsmanship, and the devaluation of past experience in favor of potential outcomes are embedded in the institutional and technical infrastructure of ultra-high-speed Internet.

Google Fiber and Flexible Capitalism

Like so many others, I have been interested in understanding what the rollout of Google's ultra-high-speed Internet infrastructure, known as Google Fiber, means for the Kansas City region. Popular press coverage of this infrastructure read like press releases, replicating many of the talking points included in Google's original announcement of its planned fiber-optic network.Footnote1 Elise Ackerman of Forbes and Jeff Bertolucci of PCWorld expressed the widely shared sentiment that Kansas had “won the Google Fiber jackpot” and that “if you're not a resident of Kansas City, be jealous. Be very jealous.”Footnote2 This warm reception of Google Fiber was the result of three intersecting processes: (1) a general dissatisfaction with major Internet service providers and the comparatively favorable public opinion of Google; (2) the United States Federal Government had just brought the need for a national Internet infrastructure upgrade into popular consciousness with the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 and the Federal Communications Commission's 2010 National Broadband Plan; and (3) the Google Fiber project announcement was a magnificent public relations campaign, with Google treating the rollout like a nationwide lottery. The result of this convergence of interest was such that applications representing nearly 1,100 cities were submitted hoping to be the first city to receive Google Fiber, with one city going so far as to unofficially change its name to “Google.”Footnote3

Though public sentiment remains favorable, some have begun to express concern regarding the process and consequences of this infrastructure rollout. Commentators noted that the planned Google Fiber rollout threatened to further entrench Kansas City's race and class divide, as early rollout plans generally did not include the historically impoverished Kansas City east side.Footnote4 Others began to question the legitimacy of the political and economic concessions made to attract Google to the region.Footnote5 And still others became disillusioned as Google made a series of public relations missteps over the course of the rollout.Footnote6 I sympathize with these concerns, but it seems that commentary surrounding Google Fiber tends to gravitate toward two poles: those who celebrated the promises of Google Fiber (as a startup incubator) and those who critiqued Google Fiber for failing to live up to its promises (due to further entrenchment of the digital divide). Though these perspectives are valid, my interest in Google Fiber is somewhat different; I am interested in understanding what Google Fiber means in and of itself.

My interest in Google Fiber and the Kansas City region stems from two reasons: First, Google Fiber's mode of privatization has been hailed as a model for future Internet infrastructure advancementFootnote7; second, the Kansas City region is representative of many other mid-sized metropolitan areas in the United States. Like many other mid-sized metropolitan areas across the United States, Kansas City is under substantial political economic pressure to reconfigure itself in line with the economic rationality of the global city.Footnote8 Though this is true of all cities, major metropolitan regions, such as New York and London, already possess much of the urban infrastructure required of being a global city, and thus there is substantially more political economic upheaval experienced by mid-sized metropolitan regions in contrast to already established global cities.Footnote9 As it pertains to Google Fiber, for instance, Kansas City needed Google more than the Los Angeles and San Francisco metropolitan regions did, respectively, and hence Kansas City was willing to sacrifice the political and economic concessions that these other regions were not. This is why Kansas City was ultimately selected by Google to serve as the initial site for Google Fiber.Footnote10 These developments suggest that the promise of Google Fiber is that it will work to reconfigure the political economic infrastructure of Kansas City in terms amicable to what Richard Sennett has called “flexible capitalism,” no matter what the cost.Footnote11

The concept of flexible capitalism offers a powerful heuristic for thinking through the relationship between Google Fiber and the Kansas City region. Though the term shares much in common with the framework of neoliberalism, I believe that flexible capitalism offers a more grounded heuristic than that of the more popular political economic concept. Theorists of neoliberalism often speak of it as a totalizing political economic regime that has come to be entrenched at every level of politics: national, international, and even local.Footnote12 Flexible capitalism, however, emphasizes the mechanics of late capitalism vis-à-vis the ideology of late capitalism, as opposed to the other way around.Footnote13 This has the effect of reminding us that, though neoliberalism may exert hegemonic influence, this new economic rationality “is still only a small part of the whole economy.”Footnote14 Hence, flexible capital operates as a powerful analytic for thinking through late capitalism precisely because the concept orients our attention to the political economic rationalities mobilized by the policies of late capitalism: the privileging of short- over long-term relationships; the emphasis on meritocracy over craftsmanship; and the devaluation of past experience in favor of potential outcomes. These three processes operate as axiological challenges to the subjects of late capitalism, as they dictate which subjectivities are to be valued and how we are to relate to one another. This article, as such, is an exploration of how the infrastructure and political economy of Google Fiber is working to reconfigure the Kansas City region's economic value system in terms amenable to flexible capitalism.

Though flexible capital precedes the advent of Google Fiber, my argument is that this infrastructure contributes to a system of uneven development whereby populations are being segregated as candidates for entrepreneurial innovation, replete with all the risk—or political economic trash—and the absolute precarity that being classified as such entails. To make this argument, this paper is structured as follows: (1) I illustrate how the implementation of Google Fiber operates as a form of uneven technological development along race, gender, and class lines; (2) I discuss how Google Fiber operates as a pressure chamber of innovation, whereby the risk and reward of entrepreneurialism is intensified; and (3) I document how this precarious valuation of the entrepreneur as the model citizen of flexible capital treats “non-entrepreneurial” populations as political economic trash.

Race, Gender, Class, and Uneven Technological Development

The myth of the entrepreneur is that we live in an economy of scope rather than scale, wherein small, flexible firms are leading the way toward niche marketing and decentralization. The reality, as Doreen Massey reminds us, is that “within the economic system power is related to size.”Footnote15 Indeed, we live in a moment when multinational corporations have consolidated their influence at multiple economic layers: global, national, regional, and local.Footnote16 The consequence of this consolidation is that there is ever greater pressure for “flexibility” exerted on the worker, as the locus of economic control has—in contrast to the rhetoric of entrepreneurialism—shifted from local and regional markets to national and international markets.Footnote17 This is owing to a number of reasons. First, the concentration of wealth has resulted in a shift from managerial to shareholder power. Second, the rise in finance capital has placed greater emphasis on short- rather than long-term wealth generation. Third, new communication technologies have resulted in more powerful forms of surveillance and control at distance. Combined, these three developments mean that workers must continually respond to the pressures of a perpetual present, whereby the ability to plan for the future in terms of long-term employment, income stability, and technical employability is hindered.Footnote18 That said, the burdens (and rewards) of flexible capital operate unevenly across the parameters of race, gender, class, and other markers of identity.Footnote19 It is this unevenness that requires further introspection as we reflect upon those bodies who, however tentatively, take up the title of entrepreneur.

In contrast to the common refrain that the entrepreneurial subject is a self-made individual, labor historians and sociologists note that the bourgeois class sustains itself through a system of uneven development, whereby certain entrepreneurial subjects are enabled and others are disabled.Footnote20 Moreover, as Doreen Massey notes, it is not enough to speak of the uneven support for some entrepreneurial subjects over others in terms of that there is better support “in some places than others,” but rather that “uneven development must be conceptualized in terms of the basic [relations] society”:

The term “relations” is important, and is actually much more appropriate than “building-blocks.” For the classes are not structured as blocks which exist as discrete entities in society, but are precisely constituted in relation to each other.Footnote21

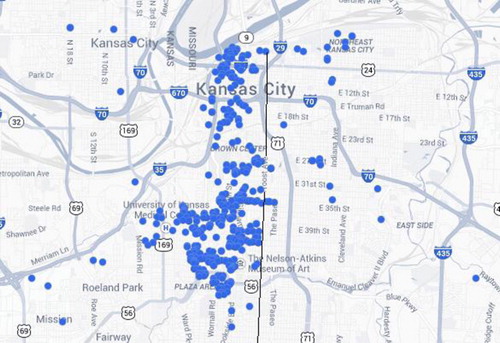

Contrary to journalistic accounts and press releases, the Kansas City startup community did not emerge ex nihilo. Rather, Google, Kansas City, and finance capital worked together to position the startup community as a centerpiece of the Google Fiber experiment. When it was announced that Google Fiber would be coming to Kansas City, the promise was that this infrastructure would position Kansas City to become a leader in education, health, and economic development.Footnote22 Yet, as residents began to pre-register for Google Fiber (which was necessary for the service), it quickly became clear that some communities were at a structural disadvantage for receiving the service; to register, residents needed a credit or debit card, a Google Wallet account, a Gmail account, and to pay a $300 startup fee, all economic barriers to residents in many neighborhoods that “don't even have bank accounts.”Footnote23 Equally disabling, for those renting a house or apartment, Google required landlords to pay the $300 startup fee for each rental unit. This would cost a mid-sized apartment complex of 50 units $15,000 to install Google Fiber for its tenants; for landlords with multiple properties or a large complex, the cost can quickly rise to over $100,000.Footnote24 As a result, it is not surprising that as of December 2014, only a handful of Google Fiber-ready apartments exist on the east side of Troost Avenue, the city's historical racial and class divide, in contrast to the abundance of fiber-ready apartments on the much wealthier and racially white west side (see ).

This absence is particularly damning as Kansas City is a hypersegregated metropolitan area, with a white racial isolation index of 90.52 percent in 2000 and a racial index of dissimilarity of 61.2 percent (vis-à-vis blacks) in 2010, meaning that over 60 percent of the white population would need to relocate to black neighborhoods for racial integration to exist.Footnote25 This hypersegregation is compounded by the fact that black “residents are more likely than poor whites to live in neighborhoods plagued by extreme and concentrated poverty, economic and physical deterioration, and poor schools,” and thus “black residents are likely to be separated, both socially and spatially, from the areas of expanding job growth and economic development.”Footnote26 Considering that only 41.1 percent of blacks are homeowners in the Kansas City region, this means that the vast majority of the Kansas City black population is heavily restricted in their access to an infrastructure that was courted by the city on the basis of its transformation of Kansas City into an economic powerhouse.Footnote27 In contrast, since “poor whites are much more dispersed throughout the metropolitan area and more likely to live in economically viable neighborhoods,” the 26.9 percent of whites who are not homeowners in Kansas City are much more likely to have both private and public access to Google Fiber infrastructure.Footnote28 And, again, this is all evidenced by the significant imbalance between fiber-ready rental units available on the historically white west side vis-à-vis the historically black east side.

If African Americans and people of color are at a structural disadvantage when it comes to access to Google Fiber, however, an abundance of resources have been made available to facilitate access for white populations, particularly white, middle class men. The much touted Kansas City Startup Village, for instance, is located within the neighborhoods of Hanover Heights/Spring Valley, Frank Rushton, West Plaza North, and West Plaza South. Though whites only represent 51.4 percent of the Kansas City region, whites constitute roughly 70.9 percent of the neighborhoods surrounding the Startup Village.Footnote29 Considering that the majority of the Startup Village is located near State Line Road, which is adjacent to the West Plaza North neighborhood (86.1 percent white), the white isolation index of this community is likely higher.Footnote30 Likewise, the Kauffman Foundation (one of the largest private foundations in the United States) regularly hosts entrepreneurial workshops in the Southmoreland neighborhood, which with its white isolation index of 83.9 percent is another hypersegregated part of the Kansas City region.Footnote31 Indeed, a Kauffman Foundation survey found that whites constituted 96 percent of its entrepreneurial community (with only 16 percent being female).Footnote32 Evidence of this uneven racial and gendered support extends to the free housing and office space programs offered for entrepreneurs. For instance, The Homes for Hackers Program offers entrepreneurs three months of free rent at a house in the Kansas City Startup Village. As of this writing, the home has officially hosted twenty-two entrepreneurs: sixteen whites (72.7 percent) and five Asians (22.6 percent [three were international residents]); of these, twenty were male (90.9 percent), and only one was female (4.5 percent); notably no official residents were of African or Latino descent.Footnote33 This ratio holds true for another free housing program, Brad Feld's Fiberhouse (which offers one year of free residence), with three white male and one Asian female residents, and hence may hold true for other hosting programs as well.Footnote34

So, although Kansas City is home to a vibrant community of activists and civil servants dedicated to public service, the political economic resources available to marginalized communities pales in comparison with those made available to white populations.Footnote35 For instance, the Plaza Branch Library and Central Library, two of Kansas City's largest public libraries (and both recently renovated), are located within or immediately adjacent to business districts hostile to black populations.Footnote36 In contrast, the Lucile H. Bluford and Southeast Branch, which are located in heavily segregated and impoverished black communities, with 44.1 percent and 41.9 percent of their residents living below poverty respectively, were constructed in 1988 and 1995, and combined possess less than half as many computers for their adult patrons as the Plaza Branch Library and Central Library, even though computer/Internet use at these two libraries are amongst the highest of all Kansas City branches.Footnote37

This conversation regarding the political economic and racial segregation of the Kansas City region vis-à-vis Google Fiber is not intended to merely suggest that some communities in Kansas City are better prepared for Google Fiber than others, but rather to emphasize the relational nature of the uneven development that undergirds this level or lack of preparedness. The combination of Google's registration policies, the hostility to black populations, and the allocation of investment toward white communities and business districts relative to others constitute political and economic choices that grant white populations access to certain opportunities while denying those same opportunities to black populations. Likewise, we must remain sensitive to the fact that entrepreneurial spaces are almost always structured for a particular configuration of masculinity absent of familial and community obligations.Footnote38 So, although it is admirable that the Kansas City public library system was able to raise one thousand dollars to help the Lucile H. Bluford and Southeast Branch communities meet their Google Fiber registration requirements, it is important to keep this struggle for one thousand dollars in mind as we continue to think through the problem of predominantly white, middle class men receiving free rent and other forms of institutional support to establish high-tech startups in Kansas City.

A Pressure Chamber of Innovation

Joseph Schumpeter, the great theorist of entrepreneurialism, recognized that the entrepreneur did not exist for herself but rather lived for the “entire bourgeois stratum.”Footnote39 The entrepreneur did not constitute a social class but rather, in cases of entrepreneurial success, “the bourgeois class absorbs them and their families and connections, thereby recruiting and revitalizing itself.”Footnote40 To this end, capitalism not only establishes a series of institutions designed to condition the performance of “the individuals and families that at any given time form the bourgeois class, [but also] ipso facto […] selects the individuals and families that are to rise into that class or to drop out of it.”Footnote41 Though material wealth would seem to be a marker of existing in the bourgeois stratum, class constitutes not just an economic threshold but a whole way of life. Indeed, we live in both a material and affect economy, with our affect economy outpacing our material economy.Footnote42 In fact, since the emergence of neoliberalism as a political economic policy in the 1980s, the value of financial assets increased from 120 percent worldwide GDP in 1980 to 355 percent of in 2007.Footnote43 In this faith-based economy, confidence in one's ability to “dwell in disorder” has emerged as a requisite of the bourgeois lifestyle.Footnote44

The fabrication of confidence that is so necessary for our contemporary economic system, however, introduces a contradiction. First, Schumpeter believed confidence to be a good thing in and of itself, as this attribute enables the entrepreneurial subject to operate “beyond the range of familiar beacons and to overcome that resistance [through] aptitudes that are present in only a small fraction of the population” and thus “revolutionize the economic organism.”Footnote45 Yet, if confidence is a requisite of healthy capitalist functioning and, over time, the production of confidence is increasingly needed for a healthy political economic system, then confidence is untethered from the very material conditions needed to warrant confidence. To illustrate this contradiction, entrepreneurialism is increasingly valorized as the future of the global economy even though the failure rate ranges from 30 to 80 percent depending upon how failure is defined (with complete liquidation resulting 30–40 percent of the time and failure to see a return on investment resulting 70–80 percent of the time).Footnote46 Second, the consequence of this contradiction is that the confidence fabricated is not just unwarranted but results in a negative cumulative effect: entrepreneurs who failed in the past are as likely, if not more likely, to fail in subsequent projects than first-time entrepreneursFootnote47; likewise, though serial entrepreneurs are more likely to succeed in future endeavors than first-time entrepreneurs, the success rate between first- and second-projects diminishes from 37 percent to 29 percent respectively.Footnote48 This means that there exists substantial pressure to get it right the first time as past success does not necessarily beget future success and first-time failure jeopardizes one's ability to procure future venture capital funding. Nevertheless, echoing the earlier work of Schumpeter, many continue to discount this rate of failure as a necessary consequence of healthy capitalist development.Footnote49

The valorization of entrepreneurial precarity is well in line with the logic of bourgeois ideology outlined by Joseph Schumpeter, and which has been further refined by neoliberalism and the processes of flexible capitalism. Schumpeter feared that since “capitalist enterprise, by its very achievements, tends to automatize progress,” it would oust the entrepreneur and expropriate from “the bourgeoisie as a class […] not only its income but also what is infinitely more important, its function.”Footnote50 This anxiety was echoed by the influential economist, W.W. Rostow, who worried that the fruits of late capitalism would breed economic apathy: “what to do when the increase in real income itself loses its charm? Babies, boredom, three-day weekends, the moon, or the creation of new inner, human frontiers in substitution for the imperatives of scarcity”?Footnote51 If Schumpeter and Rostow feared that capitalism would buckle under the weight of its own success, but struggled in conceiving of a possible solution to this presumed calamity, the proponents of neoliberalism and flexible capitalism have offered precarity itself as the new economic frontier; as Harvard Business Professor Shikhar Ghosh approvingly notes, “in Silicon Valley, the fact that your enterprise has failed can actually be a badge of honor.”Footnote52

The campaign surrounding Google Fiber is a part of this positive repositioning of precarity, as a series of public and private institutions have coalesced to establish the infrastructure as an entrepreneurial incubator. Google, Kansas City, and the Kauffman Foundation have invested a substantial amount of resources so as to attract venture capital and entrepreneurial labor to the Kansas City region.Footnote53 These resources, however, operate as incentives meant to procure the energy of entrepreneurial labor but do not address the consequence of this entrepreneurial activity—which is massive failure rates and elevated precarity. To do so, in fact, would be counterproductive from the perspective of flexible capital, for as Kauffman Foundation senior fellow Paul Kedrosky argues, “Kansas City is on the verge of an opportunity for unprecedented waste. And that […] could be a wonderful thing.”Footnote54 Like Schumpeter before, Kedrosky believes that capitalism must resist the public pressure to minimize the production of waste, for to do so would be to undermine the engine of capitalism. Flexible capital conceives of waste as the excess of experimentation required of economic growth. The implication, of course, is that waste operates as a euphemism for the 30–80 percent of entrepreneurial activities that result in complete liquidation or failure to see a return on investment: Waste is the term used to refer to those populations whose usefulness has run its course.

This is all consistent with the tenants of flexible capital, in that contrary to the concept of the incubator, the infrastructure in Kansas City operates more as a pressure chamber. As Richard Sennett has noted, flexible capitalism is impatient and as such values short- over long-term relationships, meritocracy over craftsmanship, and potential outcomes over past experience.Footnote55 The Kansas City region has worked to normalize these practices by acquiescing to many of the political economic demands of private capital relative to public interests. For instance, Milo Medin, Vice President of Access Services at Google, notes that the Kansas City region was selected because the city streamlined its rights-of-way oversight for the company.Footnote56 Rights-of-way oversight matters for, as Medin continues:

laws like the California Environmental Quality Act can make it prohibitively expensive for companies to invest in new projects […]. Many fine California city proposals for the Google Fiber project were ultimately passed over in part because of the regulatory complexity here brought about by CEQA and other rules.Footnote57

If the consequence of precarity and the emphasis on short- over long-term relationships is that some populations will be euphemistically conceived as waste, the byproducts of capitalist progress, the concept of meritocracy disavows the responsibility of institutions toward their respective publics. This principle of meritocracy is being embedded in the institutional infrastructure of the Kansas City region. First, the local governments of the Kansas City region acquiesced to Google's build-to-demand marketplace approach as opposed to the traditional universal service/public good approach.Footnote62 This demand-based approach, which requires a particular percentage of one's community to register for service in order to obtain individual eligibility, places the onus of the digital divide on those who suffer from the divide as opposed to those institutions who establish the divide. Second, though concern about the digital divide matters, the conversation is often dominated by a sense of techno-utopianism: The argument that the digital divide is bad often leaves uninterrogated the question of what is it that we are hoping to close. To be clear, the digital divide is a problem. But it is a problem precisely because in a society dominated by short- over long-term relationships, meritocracy over craftsmanship, and potential outcomes versus past experience, lacking access to the Internet categorically denies impoverished populations the possibility of accessing even these limited pleasures. And yet, instead of rushing to bring these populations into the fold, and purposefully or inadvertently transforming them into the standing reserve of flexible capital, as candidates for class promotion (highly unlikely) or productive waste (highly likely), we ought to incorporate an analysis of how digital environments operate into our critique of the digital divide.

As it stands, the environment being established in the Kansas City region is one whereby the production of entrepreneurial waste is being accelerated. This pressure chamber of innovation has been institutionalized through a series of interlocking private mechanisms. First, the Kauffman Foundation established the 1 Million Cups speaker series (in 2012), where each week two local entrepreneurs give six-minute presentations (with twenty minutes for questions) about their startups to an audience of other aspiring entrepreneurs, potential investors, and others. Though the event is not meant to solicit financial support from investors, entrepreneurs are often under pressure “to find solutions for their problems with limited time and knowledge,” and thus it is highly likely that presenters are using this venue to promote their business.Footnote63 Second, the startup community, with support from venture capitalists and the Kauffman Foundation, has established a handful of short-term, rent free homes to attract entrepreneurs to the region. Though this opportunity would appear to be of benefit to would-be entrepreneurs, these opportunities are positioned in relation to conventional mechanisms of social mobility. For instance, the Kansas City startup community is heavily influenced by Brad Feld, co-founder of the Foundry Group venture capital firm, who has argued that “government officials, university professors, and people at support organizations are ‘feeders,’ not leaders, of the entrepreneurial community.”Footnote64 This antagonistic relationship with conventional public interests encourages would-be entrepreneurs to let go of conventional support structures and instead embrace precarity.

The consequence of this precarity, as Sennett argues, is that of living in a constant state of relative anxiety and uncertainty regarding the present and near-future.Footnote65 For those who are fortunate enough to win short-term, rent free housing in the Kansas City region, the timeline of progress is measured in terms of three to twelve months. This is in contrast to conventional institutions of social advancement, such as public universities, which typically privilege craftsmanship over meritocracy, and thus often grant four to five years for intellectual and technical maturation. Hence, we must understand the public and private support for Google Fiber and high-tech entrepreneurialism to operate as part of a larger shift in political support for the mechanisms of flexible capital. This means that conversations about the digital divide must move beyond questions of mere access and instead consider what it is that we are accessing: an incubator, or a pressure chamber of innovation? To the extent that it is the latter, conversations about the digital divide ought to be concerned about the consequence of conceiving of progress as the production of waste. For if flexible capital operates as the second coming of social Darwinism, then what does it have to say about those populations who have little hope of even aspiring to be conceived as waste?

High-Tech Waste/Low-Tech Trash

In her analysis of the concept of pollution, the anthropologist Mary Douglas denied dirt the status of being an ontological absolute and instead reconfigured the label as an axiological judgment by one population toward another group or thing.Footnote66 Waste occupies a specialized form of dirt in that even the most well-functioning of systems is unable to account for all that it produces. Economic systems, like all systems, are not immune and hence different economic systems account for and process matter more or less ethically than others. Flexible capital and neoliberal economic policies are particularly notorious for simultaneously valorizing the production of excess waste (in terms of both economic disparity and environmental degradation) and condemning the consequence of this excess waste (in terms of a failure of personal responsibility and the justification for the deconstruction and reconstruction of social institutions along race, gender, and class lines).Footnote67 Kauffman Foundation senior fellow Paul Kedrosky illustrates this stance when he valorizes the advent of Google Fiber as an “opportunity for unprecedented waste.”Footnote68 The question remains, however, as to how flexible capital responds to and operates upon those populations who have already been defined as waste in advance; that is, if high-tech “waste” is valorized as a necessary byproduct of capitalist progress, then what of that low-tech “trash” that is of little entrepreneurial value in the first place?

Though the precarity experienced by the candidates for high-tech entrepreneurialism is substantial, it matters whether one is considered a candidate for high-tech waste rather than treated as a form of low-tech trash. The first means that though one's individual welfare may be disregarded, as a whole this population is valued as an essential part of the political economic system, and hence worthy of some collective investment. The second means that both one's individual and collective welfare is disregarded as an unessential part of the political economic system, and hence unworthy of any substantial form of collective investment. That is, the first population is afforded the opportunity, however marginal, to reap the rewards of flexible capital, whereas the second population is confined to maintaining the inflexible substructure of flexible capital as the low-paid and disrespected service workers and manual labors with minimal prospects for financial security nor upward mobility. Though this fate of financial insecurity and economic immobility may await those in the first category, for those in the second, this fate is all but guaranteed. As Dean Starkman notes:

Due to historic factors, black workers predominate in fields less likely to offer employer-based health insurance, sick leave, child care, retirement plans, and other benefits. So black resources are much more often needed to cover emergencies and day-to-day expenses, while whites are able to put more of their earnings aside. As a result […] every extra dollar of income earned by whites generates $5.19 in new wealth over 25 years, while another dollar of income for a black family adds a mere 69 cents to its bottom line. A penny saved is a nickel earned for whites—but less than 1 cent for blacks.Footnote69

Google Fiber is a part of this history of uneven development that ought to be understood as more than merely uneven support, but rather, categorical effacement. The digital divide is not about a gap in accessing new opportunities—such as reading and writing code, as important as that may be—but rather the implementation of artificial and often unnecessary political economic barriers to conventional means of accessing and participating in the public sphere and civil society. In terms of civil society, the promise of Google Fiber is that business, education, entertainment, and medicine will all benefit from the advent of ultra-high-speed Internet.Footnote71 Though this is perhaps true as a professional communications network—enabling professionals and intellectuals to exchange certain data intensive documents—the idea of conducting a medical exam or parent-teacher conference online (two specific examples mentioned by Google) represents an evacuation of the public from issues of public health and educationFootnote72; the immediacy and speed offered by the hypermediation of ultra-high-speed Internet treats communication as pure information and effaces the fundamental significance of contextual factors, such as culture and environment. Conceived as such, the conception of civil society offered by Google Fiber is the lie that one could believe himself connected because he is surrounded by glass and plastic.Footnote73

The advent of Google Fiber represents an infrastructural extension of the trend toward enclosure that we have been witnessing on the Internet. Indeed, though the Internet can be many things, the configuration desired by big data, big business, and big government is that physical place and all the messiness it entails might be replaced by a virtual space purified of those undesirable elements.Footnote74 Google Fiber complements this trend toward enclosure in that its uneven implementation creates a de facto infrastructural enclosure that serves as an alibi for existing trends toward political economic enclosure. For example, though members of the community have noted that communicating with the city is difficult, and that many prefer receiving information from the city through print, mail, and public broadcast channels—especially women, the elderly, low income earners, and those in the racially and economically segregated Third and Fifth Council Districts—Kansas City, Missouri has been promoting its online communication channels (favored by younger, wealthier, and white populations), in spite of a recent city report that found that “the new website makes it harder to find services.”Footnote75 Combined with Kansas City's promotion of the social media platform, Nextdoor, which restricts communication to those living within specific neighborhoods and requires members to offer proof of residence, Google Fiber contributes to the fragmentation and uneven support of Kansas City's public sphere.Footnote76

This might not be a problem if online platforms were merely one channel amongst others for communicating with the public, but increasingly offline channels are being closed in the name of government austerity, thereby offloading the infrastructural responsibilities of governance from the state to the citizen. As a result, citizenship is reconfigured in terms of meritocracy, with those who can afford the infrastructure being deemed as deserving of citizenship relative to others. Indeed, the adoption of the Nextdoor platform by “more than 100 neighborhoods, representing nearly 40 percent of the Kansas City metro,” in conjunction with the uneven implementation of Google Fiber along racial and economic lines, suggests a de facto return to Kansas City's past, when neighborhood and homeowner associations actively worked to discriminate against and undermine the political economic wellbeing of populations of color.Footnote77 Yet, whereas in the past these associations operated with legal and cultural legitimacy, today these discriminatory practices are being embedded in the communications infrastructure of the public sphere, and thus bypass the need for legal and cultural approval. This is what it means to suggest that infrastructure operates as a form of “politics by other means”Footnote78: The digital divide is not about a gap in accessing new opportunities but rather an often unnecessary political economic barrier constructed to prohibit those conceived as trash from accessing and participating in the public sphere and civil society.

Conclusion

In 2010, the United States Federal Communications Commission identified broadband as “the great infrastructure challenge of the early 21st century.”Footnote79 Because broadband “is transforming the landscape of America more rapidly and more pervasively than earlier infrastructure networks,” the FCC argued, it was imperative “to develop a National Broadband Plan ensuring that every American has ‘access to broadband capability.’”Footnote80 Though such connectivity surely matters, lost in the national conversation is the question of what such connectivity means in and of itself. Though the origin stories of the Internet are well known, it is common practice to treat the infrastructure as though it emerged ex nihilo as an ahistorical and agnostic medium: the Internet enables communication. Though it is true that the Internet enables communication, Paul Starr's compelling The Creation of the Media reminds us that “a new technology may have particular consequences because of its architecture, not because that is the only way it could be. Architectural choices are often politics by other means, under the cover of technical necessity.”Footnote81 Indeed, forty years ago, James Carey lamented that “because we have seen our cities as the domain of politics and economics, they have become the residence of technology and bureaucracy. Our streets are designed to accommodate the automobile, our sidewalks to facilitate trade, our land and houses to satisfy the economy and the real estate speculator.”Footnote82 This article, then, has been an analysis of a particular configuration of broadband infrastructure that has been advanced as a model for communities across the United States.Footnote83 Three observations from this analysis warrant reemphasis in this conclusion.

First, I have argued that the construct of flexible capitalism may operate as a more sensitive analytic for understanding the mechanics of late capitalism vis-à-vis the ideology of late capitalism. Though sharing much in common with neoliberalism, flexible capitalism orients our attention to the mechanisms by which late capitalism privileges short- over long-term relationships, positions meritocracy over craftsmanship, and devalues past experience in favor of potential outcomes. The point of this preference is not to privilege one analytic over the other, but rather to suggest that neoliberalism and flexible capital operate hand in hand. If neoliberalism orients our gaze toward the realm of policy and political processes, flexible capitalism orients our attention toward the material processes by which neoliberalism is embedded into civic infrastructure. As it pertains to Google Fiber, I argue that this infrastructure and other configurations like it operate as part of the growing infrastructure of flexible capital.

Second, I have argued that the digital divide operates through a system of uneven development whereby certain populations are not innocently left behind but rather actively segregated. Moreover, universal service does not mean merely offering ultra-high-speed Internet connections to every housing unit but rather offering the same form of infrastructure for all members of the public. The digital divide in Kansas City is not just the lack of Internet access; it includes the entrepreneurial support offered to predominantly white men in absence of other populations. Likewise, as Doreen Massey reminds us, it is not merely that white men are better supported than other populations but rather that, consistent with Kansas City's history of hypersegregation, populations are constructed in relation to each other so that “the different functions in an economy are held together by mutual definition and mutual necessity.”Footnote84 The digital divide will never be closed until this point is acknowledged. And again, I have argued that a series of political economic policies and practices have emerged regarding Google Fiber that work to keep the function of the digital divide intact.

Third, the prior point is perhaps made most explicit by the conception of ultra-high-speed Internet infrastructure as a pressure chamber of innovation. Advocates of entrepreneurialism see innovation as a form of creative destruction whereby existing socioeconomic structures are made obsolete in favor of those capable of operating in a state of perpetual precarity. Innovation creates waste in that: (1) those populations incapable of capitalizing on this form of precarity are denigrated as trash; and (2) entrepreneurial innovation conceives of work in terms of meritocracy in contrast to craftsmanship, whereby the obsolete innovation and innovator are confined to the dustbin of capitalist progress. In other words, the emphasis on short- over long-term relationships, meritocracy over craftsmanship, and devaluation of past experience in favor of potential outcomes means that investment is directed toward those populations capable of operating in such an environment, whereby those unable to do so (or continue doing so) are relegated to those spaces whereby capitalist “waste” and “trash” can continue to serve capitalist development: as the low-paid and disrespected service workers and manual laborers.

In conclusion, I wish to reiterate that I do not mean to argue against the Internet. The point I wish to make is that, as others have argued, we must conceive of the Internet as a network of networks, and as such, an assemblage of overlapping and sometimes divergent architectural choices.Footnote85 Like other communication platforms, the relationship of this network of networks is constantly evolving and as communications researchers we have an obligation to discern and intervene upon the politics of those relationships as they are articulated in policy, production, and practice. As it regards broadband infrastructure, this moment is of particular importance, for as Bob McChesney has argued, communication policy, production, and practices have a history of crystallizing within the span of a decade or two, after which it becomes difficult to intervene upon the system due to the inertia of politics, economics, infrastructure, and culture.Footnote86 This may prove to be particularly true in the case of Google Fiber and other systems like it, as its build-to-demand marketplace approach as opposed to the model of universal service minimizes the production of “dark fiber” and means that this particular configuration of the Internet and digital divide may outlast the service providers who implement the system.Footnote87 As it stands, since the FCC's 2010 National Broadband Plan, net neutrality has been struck down by US Federal Courts, reinstated by the FCC, and now remains in legal limbo (policy), major content providers have signed interconnection agreements with major Internet providers (economics), and Google Fiber has emerged as a model for ultra-high-speed Internet (infrastructure). If culture is the last bastion of this communications juncture, then it seems imperative that communications researchers not squander this fading opportunity to discern and intervene upon the policies, economics, infrastructure, and practices of this network of networks. Five years have passed; we might not have five more.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

[1] Susan Crawford, “America Doesn't Need Google Fiber Everywhere—but We Do Need Its Buzz,” Wired, http://www.wired.com/opinion/2013/04/why-we-need-google-fiber-but-its-not-for-the-reasons-you-think/; Cyrus Farivar, “The Rest of the Internet Is Too Slow for Google Fiber,” Ars Technica, http://arstechnica.com/business/2012/11/the-rest-of-the-internet-is-too-slow-for-google-fiber/; Cecilia Kang, “Google Fiber Provides Faster Internet and, Cities Hope, Business Growth,” The Washington Post, http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/technology/google-fiber-provides-faster-internet-and-cities-hope-business-growth/2013/01/25/08b466fc-6028-11e2-b05a-605528f6b712_story.html; Lucie Robequain, “Welcome to ‘Silicon Prairie’—Google Ultra High-Speed Broadband Shakes up Kansas City,” World Crunch, http://worldcrunch.com/tech-science/welcome-to-quot-silicon-prairie-quot-google-ultra-high-speed-broadband-shakes-up-kansas-city/google-internet-fiber-ultrafast-kansas/c4s10584/#.UXQvhays1R0; Minnie Ingersoll and James Kelly, “Think Big with a Gig: Our Experimental Fiber Network,” Google, http://googleblog.blogspot.com/2010/02/think-big-with-gig-our-experimental.html.

[2] Elise Ackerman, “How Kansas Won the Google Fiber Jackpot and Why California Never Will,” Forbes, http://www.forbes.com/sites/eliseackerman/2012/08/04/how-kansas-won-the-google-fiber-jackpot-and-why-california-never-will/; Jeff Bertolucci, “Gigabit Paradise? Google Ready to Lay Fiber in Kansas City,” PC World, http://www.pcworld.com/article/249491/gigabit_paradise_google_ready_to_lay_fiber_in_kansas_city.html.

[3] Tim Hrenchir, “‘Topeka to Be Google, Kansas’,” The Topeka Capital Journal, http://cjonline.com/news/local/2010-03-01/topeka_to_be_google_kansas; Milo Medin, “Ultra High-Speed Broadband Is Coming to Kansas City, Kansas,” Google, http://googleblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/ultra-high-speed-broadband-is-coming-to.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+blogspot%2FMKuf+%28Official+Google+Blog%29&utm_content=Google+Feedfetcher.

[4] Alec Dubro, “Low-Income Areas Skipped by Google Fiber System,” Speedmatters.org, http://www.speedmatters.org/blog/archive/low-income-areas-skipped-by-google-fiber-system/#.UXRaZays1R1; John Eligon, “In One City, Signing up for Internet Becomes a Civic Cause,” The New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/10/us/in-one-city-signing-up-for-internet-becomes-a-civic-cause.html?hp&pagewanted=all&_r=0; Marcus Wholsen, “Google Fiber Splits Along Kansas City's Digital Divide,” Wired, http://www.wired.com/business/2012/09/google-fiber-digital-divide/.

[5] Timothy B. Lee, “How Kansas City Taxpayers Support Google Fiber,” Ars Technica, http://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2012/09/how-kansas-city-taxpayers-support-google-fiber/; Whitney Terrell and Shannon Jackson, “Only Connect,” Harper, 2013.

[6] Karl Bode, “Google Fiber Puts the Kibosh on Startups in Kansas City,” DSLReports.com, http://www.dslreports.com/shownews/Google-Fiber-Puts-the-Kibosh-on-Startups-in-Kansas-City-126153; Laura McCallister and Amy Anderson, “Neighborhood Angry with Tree Destruction to Make Way for Google Fiber,” KCTV5, http://www.kctv5.com/story/22441264/neighborhood-angry-with-tree-destruction-to-make-way-for-google-fiber.

[7] Scott Canon, “Google Fiber Construction Disrupts as It Modernizes Kansas City,” Government Technology, http://www.govtech.com/network/Google-Fiber-Construction-Disrupts-as-it-Modernizes-Kansas-City.html; Crawford, “American.” I appreciate the anonymous reviewers for pushing me further on this point. Google Fiber's public–private partnership represents a further entrenchment of a larger system of privatization, whereby not only is public infrastructure being configured in terms amicable to private capital but also this configuration is made possible by the transference of public resources to private enterprise.

[8] Throughout this paper I use “Kansas City” in reference to the Kansas City metropolitan region, which encompasses both Kansas City, Kansas and Kansas City, Missouri, as well as nearby suburbs. Though differences exist between state and local governments, there is much overlap and shared governance.

[9] Saskia Sassen, Cities in a World Economy (Los Angeles: Sage, 2006/2011); Saskia Sassen, Cities in Today's Global Age (Metropolis Congress, 2008); Richard Sennett, The Corrosion of Character: The Personal Consequences of Work in the New Capitalism (New York: Norton, 1998).

[10] Ackerman, “How Kansas”; Milo Medin, Testimony of Milo Medin, Vice President of Access Services, Google Inc., Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Field Hearing on Innovation and Regulation (April 18, 2011).

[11] Ackerman, “How Kansas”; Canon, “Google Fiber.”

[12] David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2007).

[13] Sennett, The Corrosion.

[14] Richard Sennett, The Culture of the New Capitalism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006), 10.

[15] Doreen Massey, Space, Place, and Gender (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994), 158.

[16] Massey, Space; Dan Schiller, How to Think About Information (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007).

[17] Sennett, The Culture.

[18] Sennett, The Culture.

[19] Sennett, The Corrosion.

[20] Paul Gompers et al., “Skill Vs. Luck in Entrepreneuriship and Venture Capital: Evidence from Serial Entrepreneurs,” in NBER Working Paper Series, 42 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2006); Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism, & Democracy (New York: Routledge, 1943/2003); Massey, Space; Sennett, The Corrosion; Sennett, The Culture.

[21] Massey, Space, 86 (emphasis in original).

[22] Medin, “Ultra High-Speed.”

[23] Michael Liimatta cited in Wholsen, “Google Fiber.”

[24] Alicia Stice, “For Apartment Building Owners, Google Fiber Can Be a Tough Sell,” The Kansas City Star, http://phys.org/news/2013-07-apartment-owners-google-fiber-tough.html.

[25] Kevin Fox Gotham, Race, Real Estate, and Uneven Development: The Kansas City Experience, 1900–2000 (New York: State University of New York Press, 2002); The Heller School for Social Policy and Management, “Kansas City, Mo-Ks: Profile Summary,” http://www.diversitydata.org/Data/Profiles/Show.aspx?loc=728.

[26] Gotham, Race, 19.

[27] See The Heller School, “Kansas City.”

[28] See: Gotham, Race, 19; The Heller School, “Kansas City.”

[29] These demographics were compiled by combining the census tract data for Missouri tracts 71, 72, and 73 with those of Kansas tracts 451 and 452, as the Kansas City Startup Village cuts across these five census tracts. See: Kansas City Startup Village, “Map,” http://www.kcstartupvillage.org/map/; United States Census Bureau, “Wyandotte County, KS,” 2010; United States Census Bureau, “KCMO Census Tract Data,” 2010.

[30] These demographics were compiled by combining the census tract data for Missouri tracts 71, 72, and 73 with those of Kansas tracts 451 and 452, as the Kansas City Startup Village cuts across these five census tracts. See: Kansas City Startup Village, “Map,” http://www.kcstartupvillage.org/map/; United States Census Bureau, “Wyandotte County, KS,” 2010; United States Census Bureau, “KCMO Census Tract Data,” 2010.

[31] United States Census Bureau, “KCMO.”

[32] Jared Konczal and Yasuyuki Motoyama, Energizing an Ecosystem: Brewing 1 Million Cups (Kauffman Foundation, 2013).

[33] The Home for Hackers program does not keep demographic records. This information was extrapolated from the Kansas City Startup Village Timeline with the assistance of social networking sites such as Linkedin and Twitter. Though the Startup Village records twenty-two official residents, the reason my extrapolation only accounts for twenty-one residents is because one guest stayed under the alias of “Flash,” and hence his identity could not be confirmed.

[34] Fred Bauters, “How Handprint Landed in Kc and Won Free Rent in Feld's Fiberhouse,” http://www.siliconprairienews.com/2013/05/how-handprint-landed-in-kc-and-won-free-rent-in-feld-s-fiberhouse; Sarah Gish, “Kansas City Fetches Fitbark, a Fitness Tracker for Fido,” http://www.kansascity.com/living/article1338317.html.

[35] See: Connecting For Good, “Connecting for Good.,” http://www.connectingforgood.org/; Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, “Who We Are,” http://www.kauffman.org/who-we-are/fact-sheet; Mid-America Regional Council, “Green Impact Zone of Missouri,” http://www.greenimpactzone.org/.

[36] Yael T. Abouhalkah, “Unruly Black Youths + the Plaza = More Trouble,” The Kansas City Star, http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/opn-columns-blogs/yael-t-abouhalkah/article339426/Unruly-black-youths--The-Plaza--more-trouble.html#/tabPane=tabs-603c299d-1; Brian J. Houston, Hyunjin Seo, Leigh Anne Taylor Knight, Emily J. Kennedy, Joshua Hawthorne, and Sara L. Trask, “Urban Youth's Perspectives on Flash Mobs,” Journal of Applied Communication Research 41, issue 3 (2013): 236–252; Steve Rose, “To Protect the Plaza, Tighten Teen Curfews All Year,” The Kansas City Star, http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/opn-columns-blogs/steve-rose/article340646/To-protect-the-Plaza-tighten-teen-curfews-all-year.html; DeAnn Smith, “New Kansas City Curfew Law in Effect,” KCTV5, http://www.kctv5.com/story/15298987/new-kansas-city-curfew-law-in-effect.

[37] Jason Harper, “How the Kc Library Got Google Fiber,” Kansas City Library, http://www.kclibrary.org/blog/kc-unbound/how-kc-library-got-google-fiber; United States Census Bureau, “KCMO.”

[38] Conor Dougherty, “Two Cities with Blazing Internet Speed Search for a Killer App,” The New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/06/technology/two-cities-with-blazing-internet-speed-search-for-a-killer-app.html?_r=0; Konczal and Motoyama, Energizing; Julianne Pepitone, “Black, Female, and a Silicon Valley ‘Trade Secret,’’’ CNN, http://money.cnn.com/2013/03/17/technology/diversity-silicon-valley/index.html.

[39] Schumpeter, Capitalism, 134.

[40] Schumpeter, Capitalism, 134.

[41] Schumpeter, Capitalism, 76.

[42] Antonio Negri, “Value and Affect,” Boundary 2 26, issue 2 (1999): 77–88.

[43] Susan Lund, Toos Daruvala, Richard Dobbs, Philipp Härle, Ju-Hon Kwek, and Ricardo Falcón, Financial Globalization: Retreat or Reset (McKinsey Global Institute, 2013).

[44] Sennett, The Corrosion, 62.

[45] Schumpeter, Capitalism, 132.

[46] Deborah Gage, “The Venture Capital Secret: 3 out of 4 Start-Ups Fail,” The Wall Street Journal, http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10000872396390443720204578004980476429190; Gompers et al., “Skill”; Carmen Nobel, “Why Companies Fail—and How Their Founders Can Bounce Back,” Harvard Business School, http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/6591.html.

[47] James Surowiecki, “Epic Fails of the Startup World,” The New Yorker, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/05/19/epic-fails-of-the-startup-world.

[48] Gompers et al., “Skill.”

[49] Nobel, “Why Companies”; Surowiecki, “Epic.”

[50] Schumpeter, Capitalism, 134.

[51] Walt Whitman Rostow, The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto, 3rd ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1960/1990), 16.

[52] Shikhar Ghosh cited in Nobel, “Why Companies.”

[53] Wendy Guillies, “Entrepreneurial Expert Brad Feld Buys House in Kansas City Startup Village, Launches Competition to Live in It,” Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, http://www.kauffman.org/newsroom/2013/03/entrepreneurial-expert-brad-feld-buys-house-in-kansas-city-startup-village-launches-competition-to-live-in-it; Motoyama et al., Think Locally, Act Locally: Building a Robust Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (Kauffman Foundation, 2014); Michael Stacy, “Kauffman Fellow Wilbanks Explores KC's Fiber Opportunity,” Silicon Prairie News, http://siliconprairienews.com/2012/03/kauffman-fellow-wilbanks-explores-kc-s-fiber-opportunity-video/; Terrell and Jackson, “Only Connect.”

[54] Paul Kedrosky cited in Michael Stacy, “Paul Kedrosky Touts Merits of ‘Waste’ in Latest Google Fiber Talk,” Silicon Prairie News, http://siliconprairienews.com/2012/04/paul-kedrosky-touts-merits-of-waste-in-latest-google-fiber-talk-video/.

[55] Sennett, The Culture.

[56] Medin, Testimony.

[57] Medin, Testimony.

[58] Sennett, The Culture, 4.

[59] Richard Maxwell and Toby Miller, “Ecological Ethics and Media Technology,” International Journal of Communication 2 (2008): 331–353.

[60] See Stacy, “Paul.”

[61] Paul Kedrosky cited in Stacy, “Paul”; see also Gage, “The Venture.”

[62] Alistair Barr, “Google Fiber Is Fast, but Is It Fair?” The Wall Street Journal, http://online.wsj.com/articles/google-fuels-internet-access-plus-debate-1408731700.

[63] Konczal and Motoyama, Energizing; Motoyama et al., Think Locally.

[64] Konczal and Motoyama, Energizing, 13; see also Motoyama et al., Think Locally.

[65] Sennett, The Corrosion.

[66] Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concept of Pollution and Taboo (New York: Routledge, 1966/2002).

[67] Cameron McCarthy, Heather Greenhalgh-Spencer, and Robert Mejia, “Introduction: Mapping the New Terrain,” in New Times: Making Sense of Critical/Cultural Theory in a Digital Age, ed. Cameron McCarthy, Heather Greenhalgh-Spencer, and Robert Mejia (New York: Peter Lang, 2011); Harvey, A Brief.

[68] Stacy, “Paul.”

[69] Dean Starkman, “The $236,500 Hole in the American Dream,” New Republic, http://www.newrepublic.com/article/118425/closing-racial-wealth-gap

[70] Thomas Shapiro, Tatjana Meschede, and Sam Osoro, “The Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap: Explaining the Black–white Economic Divide,” 8: Institute on Assets and Social Policy, 2013.

[71] Medin, Ultra High-Speed.

[72] Medin, Ultra High-Speed.

[73] This sentence is an update of Michel de Certeau's concluding remarks on the cultural consequences of railway transportation: “there comes to an end the Robinson Crusoe adventure of the travelling noble soul that could believe itself intact because it was surrounded by glass and iron.” Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980/1988), 115.

[74] Robert Mejia, “‘Walking in the City’ in an Age of Mobile Technologies,” in Race/Gender/Class/Media 3.0: Considering Diversity across Audiences, Content, and Producers, ed. Rebecca Ann Lind (Boston: Pearson, 2012), 113-118.

[75] KCStat, “Customer Service and Communication—June 3, 2014,” 77, 2014; City of Kansas City, Missouri, “Citizens Work Sessions: Non-Traditional Forums on the Budget,” 19, 2014.

[76] Syed Shabbir, “City of Kansas City Joins Nextdoor to Improve Communication with Public,” http://www.kshb.com/alarm-clock-showcase/city-of-kansas-city-joins-nextdoor-to-improve-communication-with-public; Crystal Thomas, “Localized Online Networks Are a New Way for Neighbors to Connect,” http://www.kansascity.com/news/business/technology/article1243314.html.

[77] Thomas, “Localized”; see Gotham, Race.

[78] Paul Starr, The Creation of the Media: Political Origins of Modern Communications (New York: Basic Books, 2004), 6.

[79] FCC, Connecting America: The National Broadband Plan. 2010: xi.

[80] FCC, Connecting America, 3.

[81] Starr, The Creation, 6.

[82] James W. Carey, “A Cultural Approach to Communication,” in Communication as Culture, ed. G. Stuart Adam (New York: Routledge, 1975/2009), 27.

[83] Brier Dudley, “Portland's Being a Pushover to Snag Google Fiber,” The Seattle Times, http://seattletimes.com/html/businesstechnology/2023420101_briercolumn21xml.html; Conner Forrest, “Google's Fiber Lottery: Predicting Who's Next and How Google Picks Winners,” Tech Republic, http://www.techrepublic.com/article/the-google-fiber-lottery/. As Google has announced plans to introduce Google Fiber to other communities throughout the United States, interested cities have adopted approaches similar to those advanced by Kansas City: specifically the fast-tracking of rights-of-way oversight and the exemption of universal service requirements.

[84] Massey, Space, 87.

[85] Yochai Benkler, The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006); Matthew Crain, “The Cultural Logic of Search and the Myth of Disintermediation,” in New Times: Making Sense of Critical/Cultural Theory in a Digital Age, ed Cameron McCarthy, Heather Greenhalgh-Spencer, and Robert Mejia (New York: Peter Lang, 2011).

[86] Robert W. McChesney, Communication Revolution: Critical Junctures and the Future of Media (New York: The New Press, 2007).

[87] Herman Wagter, “How Amsterdam Was Wired for Open Access Fiber,” Ars Technica, http://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2010/03/how-amsterdam-was-wired-for-open-access-fiber/. Dark fiber refers to the excess capacity of a broadband network. Internet service providers will often establish inactive nodes and fiber lines in anticipation of future network expansion. This practice is not a natural byproduct of the principle of economies of scale, whereby it is more cost efficient to lay multiple fiber lines at the same time (one estimate is that 80 percent of broadband infrastructure costs are labor related in contrast to 10 percent for fiber), but rather is also an outcome of policy: universal service requirements. Google's build-to-demand approach minimizes the production of dark fiber as the network is only being established for those who have pre-registered for the service. For those housing units and neighborhoods that fail to pre-register, Google Fiber will bypass those communities completely until Google decides when and if it will reopen pre-registration.