ABSTRACT

The last 20 years have seen numerous claims and suggestions to overcome purely text-based research. In this article I will describe the RESEARCH VIDEO project, that dedicated itself to the exploration of annotated videos as a new form of publication in artistic research. (1) Software development: One part of our team developed a software tool that was optimized for artistic research and allows for a publication as an annotated video. I will describe the features of the software and explain the design decisions that were made throughout the project. I will also point out future demands for this tool. (2) Research standards: Our team continually reflected on the questions of how to meet both academic and artistic needs, trying to shape the research process accordingly. We decided to minimize academic claims to two basic claims – “sharability” and “challengeability” and explored how the research process changes, when these claims are informing each step of the research process. Finally I will discuss suggestions to make a publication as a Research Video comparable to a research paper.

1. Introduction

1.1. Excluded forms of knowledge

The project ‘Research Video’ started in 2017 with questions about different types of knowledge that we felt were excluded from research – like subjective knowledge, tacit knowledge, performative knowledge and embodied knowledge.Footnote1 Our hypothesis was that traditional systems of knowledge-generation were dominated by forms of knowledge that could be expressed either in text or in numbers. In our specific field, artistic research in the performing arts, this leads to a disadvantage for alternative forms of knowledge, which is significant, since tacit, performative and embodied knowledge might well be the core of our research. In the community of artistic research, there is a discussion about the role of publication formats in this process (Schwab and Borgdorff Citation2014), as they might shape not only the outcome of a research but also the mindsets of the researchers, providing a specific frame that is hard to act and think against. We hypothesized that the anticipated form of publication will inform the whole process of knowledge generation. If this is the case the publication is not only the bottleneck through which researchers have to squeeze the new knowledge, but it also has a huge impact on each phase of the research, from finding a research question to defining methods of data-collection, data-analysis and discussion. Every step, we assumed, will be informed by the possibilities and limitations of the planned output. Turning this argument around: If we change the mode of the publication, every step of the research will take a different form and the whole mindset will change. This is, in general, what we wanted to explore.

1.2. Video and film in research

The one medium that, at this point in history, can challenge text, is video. For more than 100 years film and video have been an important part of research in various fields like ethnography, sport science and behavioral sciences, and increasingly in the field of artistic research (Reutemann Citation2017). Today, with the rise of digitalization, video platforms and annotation practices can unfold their whole potential as ways to generate new knowledge, to share results and to challenge traditional, text-based publications. Different formats have evolved, namely the format of the documentary and the video essay; both of them appear in a multitude of forms, ranging from low-budget productions to ‘high gloss’ image films. As this process is picking up speed, it is a good moment to investigate on its possible implications. How will this scenario change the way we generate new knowledge? Will it influence the way we perceive and reflect on performative acts? Can a video (or an annotated video) be the sole output of an academic investigation? How will it change the way we share and challenge new knowledge with other researchers and with the public? How can we build up trustworthiness within video-based research and how can we validate it?

1.3. Annotations

On a more specific level we came across a rather new technical possibility – annotated videos. They allow for a wide spectrum of combinations of video and text. In qualitative and, less important in our field, quantitative research annotation tools for analyzing video material appear in different scientific contexts such as anthropology, sociology, linguistics, behavior science and psychology, providing possibilities of coding and commenting (Moritz and Corsten Citation2018). Standards and frameworks have evolved in the single disciplines (Lausberg and Sloetjes Citation2009; Ramey et al. Citation2016; Hagedorn, Hailpern, and Karahalios Citation2008). In the arts, the discipline of dance studies has been leading in introducing annotated videos as a research tool (DeLahunta, Whatley, and Vincs Citation2015). While we found a variety of tools for video analysis, there were none or almost none optimized for the publication of research results. What if we used annotated videos to make video the primary medium of a research output with text as secondary medium? Can we create a situation where it is actually possible to publish the results of this kind of research?

1.4. Publication platforms

Publishers have slowly caught up on the trend by accepting video articles, for example Elsevier (CitationElsevier), and several journals accept video contributions. JoVE (Journal of Visual Experiments) claims to be ‘the world-leading producer and provider of science videos with the mission to improve scientific research and education’ with more than 10,000 videos available (CitationJoVE). It is not a journal in a classic sense, but rather a repository, and it offers no peer review. The platform ‘Latest Thinking’ gets much closer to being a journal as it proposes a format called ‘Academic Video’ (CitationLatest Thinking) and presents the research in a structured way with chapters analogous to a research paper, following the IMRaD Modell: Introduction, Method, Results and Discussion. The ‘Journal for Embodied Research’ claims to be ‘ the first peer-reviewed, open access, academic journal to focus specifically on the innovation and dissemination of embodied knowledge through the medium of video.’ (CitationJER). It relies on the format of video essays and provides a peer review process. The viewer finds an abstract as text and can view the embedded video essay.

While these platforms grant certain academic standards and transfer them to video, the accepted formats are not very innovative but rely on conventions already established in film and video. There seems to be no ambition to develop them further. Furthermore none of the platform will accept annotated videos or has the technical possibility to do so. The displayed formats also have very limited interactivity: The viewer can navigate the academic video as much or as little as any other video, using features like ‘play’, ‘stop’, ‘jump’. The possibilities for adding text are basic, taking the form of subtitles and voice-over. This is a severe limitation as it means that the added information is time dependent: it must be perceivable in exactly the time of the video being played. This limits the amount and precision of information attached to a specific moment of the video.

1.5. Research question

Taking this as a starting point we asked the following questions:

What if we had a video annotation tool that is optimized for the publication of artistic research? What would it look like?

If this form of publication was the primary output of a research project, how would this transform the whole research process?

Could we change the hierarchy of forms of knowledge and come up with a form of research that is more sensitive to embodied knowledge?

2. Materials and methods

There are quite a lot of annotation tools available and used in research, but they focus on video analysis – not on the publication of results. This of course makes sense, since you don’t need a publication tool if there are no publication platforms where you can publish your results. So even researchers who rely heavily on annotated videos in the analysis have to switch to a text-based form of publication in the end. Of course this is not completely true: you can insert links or embed videos in articles. However, the primary structure will still be dominated by the text – with the video serving as illustrations or appendix of what has already been said in the text. The real reflective work will be inside the text. The text can stand for its own, while the accompanying video in general needs explanation.

Our developers, Martin Grödl and Moritz Resl, started by testing seven tools for annotating videos including ELAN and ANVIL,Footnote2 each with the same simple use-case of opening a short video file and annotating a certain region. They made a number of important observations, which allowed us to formulate our own goals more clearly.

Most of the tools were hard to even get running, due to technical restrictions like operating system requirements or dependencies on other software or libraries.

Some were based on closed or unsupported/outdated systems like Flash.

Video format support was generally lacking.

Most of the tools were focused on certain use cases, like transcription or linguistics, and made by experts of the respective fields for other experts.

In general, user experience was unsatisfying. User interfaces were unresponsive and conventional keyboard shortcuts (e.g. for play/pause, copy/paste) were often unsupported.

It was surprisingly hard to get started using those programs, even with our minimal use-case. In many situations it was impossible to complete the task intuitively, without studying the user manuals (Grödl & Resl, Handbook Research Video, to be published 2021).

In opposition to this we wanted to create a more intuitive user experience. The new tool should be

Easy to use.

Easily accessible. Our application should run in a popular web browser, requiring no installation.

Open. Being part of a research project, we decided to use open technologies as much as possible as well as an open source development model. The complete source code of the application is open and can be studied, modified and extended freely.

Based on best-practices. We decided to follow well-established conventions, regarding user interfaces and the video medium.

With this background, a prototype was created. The research was set up as a design research with the prototype being developed and optimized in several use cases with structured feedback to the developers. For this we set up several use-cases. On one hand there were two ‘big’ use-cases, a doctoral thesis in the field of dance by Marisa Godoy and another doctoral thesis in the field of visual anthropology by Lea Klaue. Both candidates based their research on video and used the Research Video tool for the analysis of their data and the presentation of results. These outputs are accepted as parts of their PHD by the according universities. Additionally a multitude of small use-cases were produced on each level of development, one milestone being the Research Academy 2018, a 8-day workshop in which international artists pursued small research projects with the RV tool. More small use-cases emerged within the project team and in curriculum of cast/Audiovisual Media at the Zurich University of the Arts, where it was used to analyze film dramaturgy.

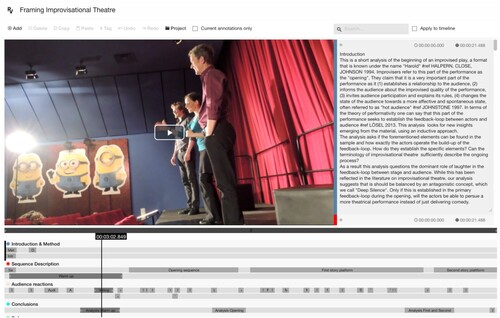

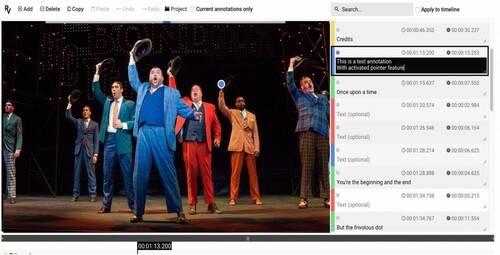

The user interface, after several iterations of user feedback, looks like this figure ().

The interface comprises of four components, which are similar to a video editing interface. The main window shows the video itself. Above this there is a toolbar, displaying the features for creating a project, especially adding and deleting annotations and tags. On the right side, in the ‘inspector’ the annotations are shown as a list. It is possible to activate the feature ‘current annotations only’ in order to only show the annotations at a specific point of the video. The section at the bottom displays the tracks that were created as long horizontal lines.

2.1. Annotations

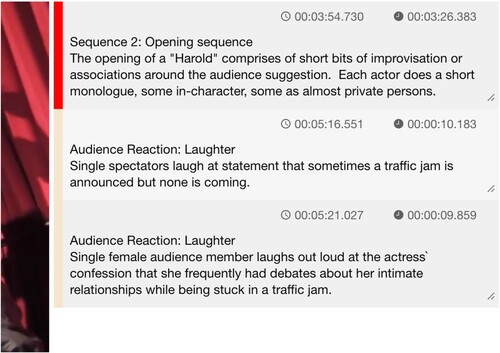

Annotations consist of text that refers to a specific part of the video, a certain moment or time span on the timecode. Every annotation thus has a clearly defined object or situation that is annotated. Every annotation appears in two forms: (1) as a small rectangle on a track and (2) as text in the inspector on the right, marked in the colour of the track it is sitting on. The text of the annotation can contain tags (see ) and links to other digital objects.

Additionally the user can point to a specific object in the video by using the pointer feature ().

2.2. Tracks

Most annotation tools provide a single visualisation of where the annotation is situated on the timeline, but we felt this had to be extended. In our design, it is possible to create numerous timelines (or tracks) on which the annotations can be visualised. Additionally the visualisation not only displays the location in time but also represents the duration of the time span that is being referred to in the annotation. This very soon proved to be a good decision because it allowed the users to detect and display their units of analysis. Quite often the analysis starts exactly with defining these sequences. Students from cast/Audiovisual Media for example started to use the tool to identify the story structure of fictional films, marking acts and scenes in their duration.

The user can create as many tracks as he or she wishes and finds necessary. The tracks, as it turned out, in many cases correspond with what in qualitative research is termed as ‘categories’ or as ‘codes’. They can be the basic parameters of the analysis. Each track can be seen as a time-based foil through which the researcher and the viewer can observe the video. He or she can hide tracks or only look at a single track in order to take this specific perspective on the material. The tracks create a multi-perspective view on the material.

Besides displaying categories the tracks can also be used to create a structure for the publication, similar to the sections of an article ().

In this example, the tracks are used to display the structure of the research. The viewer can follow the steps the researcher has taken from the research question/research context, to the methods and the conclusions. This is similar to an academic paper, which follows the IMRaD model (which I am also following in this article), but there are important differences I will point out further down. Tracks in our use cases proved to be the most important aspect of the viewer's experience since they provide an overview over the project, almost like a list of contents.

2.3. Tagging

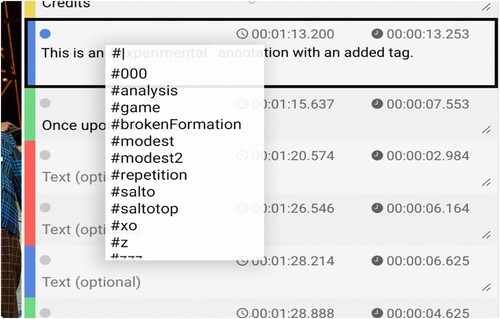

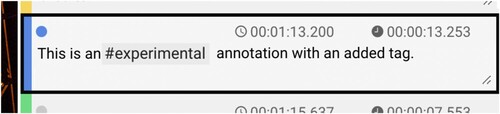

In the course of the project, we realised that our design was adequate for creating insight in temporal patterns in a chosen category, but it was less apt to detect and display connections that were not time-based and thus could not be displayed on the tracks. As we wanted to keep the researcher's minds as open as possible, we decided to introduce another feature that allows to detect patterns independent from their appearance in time: Tagging. In order to tag a specific phenomenon the researcher uses the established #-key and creates a new pattern, category, label or code, clustering phenomena that are scattered throughout the material. These tags can also serve as keywords for the research ().

Within any annotation text, a tag can be added by using the hashtag character (‘#’) followed by any word. Example: #experimental ().

Once a tag has been created it is searchable within the project. After a #-character is typed a dropdown list opens, which shows a scrollable list of all currently used tags sorted alphabetically.

This way all created tags can be easily re-used in the project and can function as additional categories (or codes) for the analysis.

With tags and tracks, the user finds a two-dimensional schema for annotations. Each annotation can be located on a track (and through this to the timeline of the video) and also be associated to a tag (and through this to a category that is independent of the timeline). Our use cases indicate that this two-dimensional setup allows for enough complexity to display the research results.

2.4. The publication workflow

In the last year of our project, we devised ways to actually publish the annotated video. As suitable platforms do not yet exist, we had to create our own workflow, making use of our institutional embedding. The Information Technology Center at the ZHdK made it possible to implement a process for uploading and hosting annotated videos. This completed the circle: it is now possible to actually publish an annotated video. The Research Catalogue is integrating this new form of publishing into its features - and from there it is only a short step to publishing an annotated video in the Journal for Artistic Research, providing a peer review process. Interested persons can find detailed information on how to publish a Research Video on the landing page of the project researchvideo.org.

3. Results

Complementing the development of our tool, we explored the demands of a publication based on annotated video in an academic context. One finding is that it is important to look at Research Videos as a new format. While in the academic world, text publications such as monographs, book sections and articles have a long tradition and specific structures, none of this is true for the new field of annotated videos. Standards and conventions cannot easily be transferred. An important thread of our discussions was on the question of in how far one could and should transfer conventions of a research paper to a research video. Probably every research community will find its own answer to this question, but after conducting numerous use cases, we can make some suggestions.

3.1. Size

Some of our results are simple. We asked about the size of an RV in relation to a text-based publication, for example. A classical scientific article (‘science paper’) has approximately the size of 5000–10000 words, starts with title and abstract and contains up to seven graphs and three tables in addition to the dominant text. The individual chapters are divided into introduction, methods, results, discussion and conclusion. In the appendix, such an article references up to 20–50 other articles and sources. Usually, an article summarizes a research project that has lasted 1–4 years. This is the traditional format for a ‘scientific article’ in a nutshell.

The equivalent to the number of pages must be translated into time needed for the reception: the estimated number of minutes for viewing the video while also reading the annotations. As reading the annotations takes some time, we estimate that a video length of 20–45 min plus 2500–5000 words is appropriate. It is long enough to provide the necessary depth of content in the presentation. Of course these numbers can vary. Additionally the author should provide references to 20–50 other sources – if we want it to be as academic as a classical research paper.Footnote3

3.2. Sharability and challengeability

When looking for requirements for academic publications, one will find varying conventions for each discipline and even for every publisher. We identified two minimal criteria, sharability and challengeability and several models for the structure of an article. Also we looked at the concept of scientific storytelling because at first glance this seemed to be close to the media of film and video. As in the artistic research community there is a noticeable distrust in academic conventions, we also took into consideration that there might be ways of researching that we don't even know about. As we aimed for an approach that is agnostic to theoretical backgrounds and research traditions, we focused on the lowest common denominator.

3.3. Sharability of research video

To meet this criterion, a publication must be transportable and immutable. A book meets these conditions in an exemplary manner: You can send it around the world and it will always display the same content, for many decades, even centuries, with the same content always in the same, precisely identifiable place. For digital object, this is not self-evident but has to be technically solved. While they are highly transportable, they are also highly unstable and open to changes. It is possible to send a Research Video to another researcher through file-sharing it. This is good for collaboration but is not enough for a publication as the file can still be changed.

3.4. Creating a permanent link

To transform it into a state of immutability, a Research Video must be uploaded to a repository or journal and given a permanent object identifier (such as a DOI number). From this point on, any modification must be impossible, i.e. the file must be technically ‘frozen’ and protected against subsequent modification. We created a workflow in which the Research Video can be uploaded in the repository of the Zurich University of the Arts, where it gets a permanent link. In a second step, this link is combined with a link to the RV Tool, which again generates a (very long) link. This link can be sent around and distributed and will open up the Research Video in view-only mode.

3.5. The view-only mode

In the view-only mode, most of the features are disabled. While the viewer sees the same interface that is used by the author, he or she cannot add or delete annotations, tracks or tags. Still the interface is interactive in a limited way: The viewer can move the playhead of the video, he or she can click on any annotation and have it displayed in the inspector. The viewer can hide tracks to look at specific threads of annotations and he or she can select tags by choosing from a drop-down menu. The tags will inform the viewer about connections and patterns the researcher generated in addition to the time-based tracks. This process grants sharability of any RV project.

3.6. Challengeability of Research Video

In order to meet this claim it must be possible for peer researchers to critically examine the contribution, i.e. the method and the exact procedure for generating knowledge. To become part of the scientific discourse, the research video must be citable and transparent in respect to the method used.

3.7. Citeability

The issue of citeability is rather easily solved by drawing on conventions of film studies. When referring to a specific moment in the movie, the formula is:

(director. year of production. time code)

Example:

(Christopher Nolan. 2005. TC: 00:14:03-00:15:52.)

director. Year of production. a. time code

Example:

(Nolan. US 2005. a.TC: 00:14:03)

3.8. Transparency of method

In a way the transparency of the analysis is high in a Research Video: the connection to the empirical data is quite evident to any viewer. Still transparency also means that the author is providing detailed information about the method used in the research. In a paper this is usually done in a section called ‘method’. Researchers must communicate the context of their research, i.e. the theories on which they draw, the concepts and terminology they use, and the research methods they apply. They must provide information about the exact processes of data collection and describe the process of data analysis. They must communicate their conclusions and discuss the implications for the field of research. All this information cannot easily be embedded in an annotated video and this was one of the hard challenges we met in our project.

Here are our proposed solutions:

Researchers as ‘talking heads': A very simple implementation is the researcher filming himself or herself while verbally giving the above information. The corresponding clips are then integrated into the research video and can be enriched by annotations. This implementation is technically simple, but requires the researchers to be willing to appear in front of a camera.

Graphical visualization: The information is given visually and recorded in a video. This can range from simply filming a panel picture to complex animations, depending on the technical possibilities. If possible, the information should be given sequentially, i.e. building on each other, in order to make full use of the temporal options of the medium video. Just like in (1), these clips must be edited into the video and provided with in-depth references.

In conclusion, one can state that our process of defining the affordances for a research video moved from applying a maximum of academic conventions (IMRaD) over applying dramaturgical models (Scientific Storytelling) to a reflection on minimal claims like sharability and challengeability. With a research video, it is not so much the task of the researcher to present a linear path or story through the research process, but to present the material in a clearly laid out way, leaving the navigation to the viewer. In a way this means letting go of control.

3.9. Structure and scientific storytelling

As a maximum position we asked: Could we transfer the IMRaD structure to an annotated video? Our answer today is: Probably not. In all our use cases, the IMRaD structure did not match the material presented in the video. Even when we tried to impose the model to the annotated video, the multi-temporal logic of the Research Video would never really support the chronological structure of an IMRaD structure. In our experimentation, it proved impossible to present the information, so that the reader/viewer can first see the ‘introduction’ then the ‘method’ and so on. Instead this information can be given in parallel, using the tracks. The IMRaD model, seen through the lens of Research Video seems highly artificial and one-dimensional. This came as a surprise and it can be interpreted as evidence that textual forms of publication create a mindset that is not compatible with the multi-perspective, multi-temporal mindset generated in the context of an annotated video. More experimentation would be necessary to validate this conclusion though.

While the IMRaD model did not meet the affordances of Research Video, it was possible to at least mimic its outer appearance. In several use cases, researchers created tracks for ‘methods’, ‘observations’, ‘analysis’ and ‘discussion’, which somehow matched the IMRaD model, but were not presented in a linear way. Instead of viewing the IMRaD as subsequent sections of the article, the viewer can see and read them as tracks, which means: in parallel. He or she can view the different sections in his or her own order, gaining more interactivity and individual readability.

Another focus of experimentation was exploring annotated video as a medium for academic storytelling. If film is an optimal method for storytelling, why not tell the research as a story? This approach seemed convincing at first, but again was not supported by our experimentation. Storytelling requires a temporal structure that is not best supported by annotated video. This might be a crucial difference to video essays: While in a video essay the control over time is in the hand of the filmmaker, in an annotated video this is not so: The viewer will usually not just run the video and watch it, but will frequently stop and get into his or her own process of going back and forth between text and video, thus creating his or her own experience. ‘Scientific Storytelling’ as we called it, might still be possible within this medium, but it seems closer to video essay than to annotated videos.

4. Discussion

While text-based formats of publication are highly formalized and conventions have emerged through centuries, entering the field of video-based publication confronts the researcher with a lot of uncertainties, ranging from simple questions like ‘What size should my contribution have?’ to complex questions of structuring the video contribution, and finding adequate tools and platforms for their publication.

Our first question ‘What if we had a video annotation tool that is optimized for the publication of artistic research? What would it look like?’ is answered by the prototype we created. It is optimized for the kind of research we pursue, artistic research, and at the same time agnostic to research traditions. The interface resembles a video editing interface and uses many of the conventions introduced in this area. It displays the annotations and finds a visualization of what part of the video the annotation is referring to. This brings with it a new form of reading with the reader will move back and forth between playing the video, stopping, and reading the annotations. Here our project goes beyond what already exists in tools for video analysis as they don’t have to reflect on their readability. The practice of reading becomes a practice of viewing which is somewhere in the middle between playing a video and reading a text. If annotated videos become a new standard for the publication of research they will have to find a balance between reading and viewing. One important observation is that, compared to video essay and documentary, the control of viewing shifts from the author to the reader/viewer, who will create his or her own path through the material.

Our second question relates to the researcher and the research process: ‘If this form of publication was the primary output of a research project, how would this transform the whole research process?’. After having conducted multiple use cases, we conclude that the hierarchy of forms of knowledge does change if the anticipated output is an annotated video. Even in early stages of a project, live annotations can help to structure observations, and moving back and forth between video and text is generating insight in a more finely grained way than without the tool. In this process, observations can slowly and gradually become explicit, with words emerging directly from looking at the material again and again. The artist-researcher is staying close to the visual material and will return to it often. The same is true for the process of analysis, for which the tool is highly applicable, slowly elaborating observational categories (tracks) and more abstract patterns (tagging). This process is very much in accord with other forms of qualitative research. The difference now is, that the researcher can present parts of this analysis in the publication in much more detail and concreteness. He or she can carefully select sequences that are worth presenting and will be aware that there is a high degree of transparency. The analysis can be reconstructed by the viewer and must be convincing both in a visual and an analytical way. While this is not easy at the beginning it also enforces a kind of ‘honesty’ and directness that is not as self-evident in text-based publications. He or she cannot ‘hide behind words’. A close connection between material and analysis stays present all the time, providing a high degree of transparency. A researcher who is publishing an annotated video must stay open to alternative interpretations and contradicting views on the material. This, overall, is probably a good thing and it certainly meets the claims of Open Science.

Our third question was ‘Could we come up with a form of research that is more sensitive to embodied knowledge?’. The answer is ‘yes, but … ’. Annotated videos have a high potential to evoke embodied knowledge, especially when the researcher is an artist himself or herself. Viewing and reflecting on bodily practices becomes an intense process with a high probability to create a valuable vocabulary that is suited for the specific project. Still, in a way, this bears the danger of re-establishing the predominance of words. While in the Research Video the knowledge stays tied to the artistic experience, referencing the output will probably resort to keywords – not ‘key video sequences’. Labeling in words will still be crucial in making the results findable, which is a crucial point in the ever growing archives of knowledge. It proves to be almost impossible to think of a way of sharing embodied knowledge that does not rely on words.

Research in fields such as artistic research might stand at the beginning of a long-term transformation from text-based to enhanced, multi-medial practices of research. The interplay of audiovisual material and language/text has already generated new formats such as video essays or annotated videos and will presumably lead to more formats, that will reshape our thinking.Footnote4 Among others they will enable new forms of looking and reflecting on performative practices like theatre, dance and performance, fostering particular modes of understanding tacit, embodied and performative knowledge that may help researchers arrive at fresh insights. Last but not least, new ways of publishing are on the horizon that might remix video and text, possibly altering hierarchies, turning video into the primary media and text into the secondary.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gunter Lösel

Gunter Lösel is a theatre scientist, actor and psychologist. In 2013, he received his doctorate in theatre studies at the University of Hildesheim on the performativity of improvisational theatre. Since 2014 he is head of the research focus Performative Practice at the ZHDK. His research interests are: cognition of acting, collaborative creativity, methods of artistic research, empirical aesthetics, liveness, acting theories and embodiment.

He heads the SNSF-funded research project ‘Research Video’ 2017–2021.

In addition to his research activities, he is active as a theatre maker; he is an artistic director of the IMPROTHEATER BREMEN and ensemble member of the STUPID LOVERS, Bremen and Karlsruhe. He regularly gives workshops on the topics of ‘spontaneous figure-finding’, ‘archetypes’ and ‘intuitive storytelling’, etc.

Notes

1 This project was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation SNF from 2017 to 2021.

2 It is worth noting that while this project was in progress, new tools for annotating videos were released or older ones were updated. Most of them are plugins for browsers and allow for annotations in the most popular platforms like youtube and vimeo. ‘Reclipped’, ‘YiNote’ and ‘Timeliney’ to name only three of them are free of payment and they have astounding features like drawing in the video, downloading notations as PDFs, tagging, and adding video and audio annotations. Still our analysis is valid: the tools are not optimized for the publication of research. They also depend on commercial platforms, which is a severe constraint for academic research and throws up questions on the confidentiality of the data and how it can be granted.

3 Actually journals in artistic research like the Journal for Artistic Research have softened the criteria and even allow for omitting them, if appropriate. As a frame for the expectations these thoughts about size still seem important to us, in order to give some orientation for researchers.

4 Automated annotations: It is worth noting that creating annotations by hand might look very old-fashioned in a few years. The next big thing in video annotations might rely on machine learning (or AI as it is often called) with its rapidly increasing power to identify objects and patterns in images and videos. Existing tools comprise LABELME (Yuen et al. Citation2009), JAABA (Kabra et al. Citation2013), ViPER (Bianco et al. Citation2015) and ViTBAT (Biresaw et al. Citation2016). This will make the analysis of large corpi of video material much more cost efficient and a new field will arise – analogous to digital humanities that established itself in parallel to text-analysis but is dealing with much bigger data. Whenever a machine is able to detect an object, it automatically creates a text like ‘female figure entering from left’, which, of course, is an annotation. This will certainly change the landscape of video-based research. But just as digital humanities will not substitute interpretative qualitative research, automated annotation will not displace annotations by hand, but create an additional approach that is somewhere in the middle between quantitative and qualitative research.

References

- Bianco, Simone, Gianluigi Ciocca, Paolo Napoletano, and Raimondo Schettini. 2015. “An Interactive Tool for Manual, Semi-Automatic and Automatic Video Annotation.” Computer Vision and Image Understanding 131: 88–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cviu.2014.06.015.

- Biresaw, Tewodros A., Tahir Nawaz, James Ferryman, and Anthony I. Dell. 2016. “ViTBAT: Video Tracking and Behavior Annotation Tool.” 2016 13th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Video and Signal Based Surveillance, AVSS 2016 1 (August): 295–301. doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/AVSS.2016.7738055.

- DeLahunta, Scott, S. Whatley, and K. Vincs. 2015. “On An/Notations (Editorial).” Performance Research 20 (6): 1–2.

- Elsevier. n.d. “Video Articles: Publish, Share and Discover Video Data in Peer-Reviewed, Brief Articles.” Accessed July 14, 2020. https://www.elsevier.com/authors/author-resources/research-elements/video-articles.

- Hagedorn, Joey, Joshua Hailpern, and Kg Karahalios. 2008. “VCode and VData: Illustrating a New Framework for Supporting the Video Annotation Workflow.” Proceedings of the Workshop on Advanced Visual Interfaces AVI, 317–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/1385569.1385622.

- JER. n.d. “Journal of Embodied Research, Home.” https://jer.openlibhums.org.

- JoVE. n.d. “JoVE About Us.”.

- Kabra, M., A. A. Robie, M. Rivera-Alba, S. Branson, and K. Branson. 2013. “JAABA: Interactive Machine Learning for Au- Tomatic Annotation of Animal Behavior.” Nature Methods 10 (1): 64–67.

- Latest Thinking. n.d. “Latest Thinking, About Us.”.

- Lausberg, Hedda, and Han Sloetjes. 2009. “Coding Gestural Behavior with the NEUROGES-ELAN System.” Behavior Research Methods 41 (3): 841–849. doi:https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.3.841.

- Moritz, Christine, and Michael Corsten. 2018. Handbuch Qualitative Videoanalyse. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Ramey, K. E., D. N. Champion, E. B. Dyer, D. T. Keifert, C. Krist, P. Meyerhoff, K. Villanosa, and J. Hilppö. 2016. “Qualitative Analysis of Video Data: Standards and Heuristics.” In Researchgate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319965247_Qualitative_Analysis_of_Video_Data_Standards_and_Heuristics.

- Reutemann, Janine. 2017. “Into the Forest.” In Kunst Wissenschaft Natur, edited by Markus Maeder, 113–143. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

- Schwab, Michael, and Henk Borgdorff. 2014. The Exposition of Artistic Research: Publishing Art in Academia, edited by Michael Schwab, and Henk Borgdorff. Leiden: Leiden University Press.

- Yuen, J., B. C. Russell, C. Liu, and A. Torralba. 2009. “Labelme Video: Building a Video Database with Human Annotations. In, Pages 1451– 1458, September 2009. [30].” In Proc. of IEEE Int. Conf. on Computer Vision, 1451–58.