ABSTRACT

In this short report, I share my experience of getting to know the choreographic practice of choreographer Jonathan Burrows and composer Matteo Fargion using the Motion Bank digital annotation tool Piecemaker. My report narrates the process of coming from a place of not knowing their practice at all to a deeper understanding through listening to interviews and deciphering their scorebooks. I present some of the thought processes and steps I took using Piecemaker, and how this led me to explore different references (e.g. other composers, historical performance forms, etc.) they draw upon to create their choreographies. I then share the results of my study using the Motion Bank publishing tool MoSys.

Introduction

Motion Bank Footnote1 started as a four-year project of The Forsythe Company providing a broad context for research into choreographic practice (deLahunta Citation2016, 131). Since 2016, the Motion Bank project is located at Mainz University of Applied Sciences and is co-directed by Florian Jenett and Scott deLahunta. One of Motion Bank’s key contributions to the fields of contemporary dance and annotation software is the development of the Motion Bank Web Systems.Footnote2 The Motion Bank Web Systems offer a digital annotation tool Piecemaker and a publication tool MoSys. Piecemaker supports the creation of text-based annotations linked to particular moments of any time-based media.Footnote3 MoSys is a publishing tool that hosts a grid-environment that can be filled with material such as Piecemaker annotations, videos, images, and links to other grids.

This report narrates the process of using these systems to open up the notation system of choreographer Jonathan Burrows and composer Matteo Fargion, who were invited in 2011 to embark on a research collaboration with Motion Bank. This collaboration concluded in 2013 with the publication of the Online Score Seven Duets – Fragments, Movements and Insights from the Interplay Between Jonathan Burrows and Matteo Fargion.Footnote4 During this time, Motion Bank acquired an extensive video archive consisting of recordings of live performance videos, recordings of specific movements from Burrows and Fargion’s vocabulary, interviews with the makers, recorded panel discussions, and the digitised versions of their scorebooks. In 2019, I was invited to explore and analyse this large pool of research material and publish my insights using the Motion Bank Web Systems.

Meeting the Both Sitting Duet

Before taking on this research project, I was not aware of Burrows and Fargion’s practice beyond Motion Bank’s Online Score. I started by delving into the Motion Bank archives where I found a playlist of 183 short video snippets from an interview Burrows and Fargion gave to the Motion Bank team in 2013. I watched and annotated these clips by creating summaries and making notes of key concepts or explanations of their choreographic practice and how they combine and respect their differences (as choreographer and composer). For example, Burrows always thinks that Fargion is the soloist and himself is the chorus – but in turn, Fargion thinks the same. This process offered me an insightful introduction to their creative practices and the meeting points in their collaboration. I learnt that Burrows and Fargion have built a combined approach that respects their individual practices by following specific ‘Choreographic Principles’ such as ‘each gives leverage to the other’ or ‘counterpoint assumes a love between the parts’ (in ‘Both Sitting Duet’ Burrows and Fargion Citation2013, 26) ().

Figure 1. Matteo Fargion (left) and Jonathan Burrows (right) recording Both Sitting Duet with the Motion Bank team. Photo Courtesy of Motion Bank.

In the past two decades, Fargion and Burrows have built ‘a body of duets which straddle the line between dance, music, performance art and comedy’ (Burrows and Fargion Citation2020). Motion Bank recorded eight of these duets with the aim to ‘read the links between them’ (Motion Bank Citation2013b). My next step was to explore these performance videos starting with the first recorded performance, Both Sitting Duet by adding it to Piecemaker (see ). I decided to start this way, considering it could allow me to perform multiple waves of annotation later in the process. In other words, I intended to include multiple layers of annotations, such as one that recorded my first impressions and another more informed that would explore patterns. I watched Both Sitting Duet multiple times and during my first viewings, I sought to capture my initial impressions and create a first layer of annotations. I tried to heighten my observational capacity and make notes (annotate) of anything that would give me a certain impression. Next to this, I tried to make sense of the piece: any goals, any specific focus, or statement. However, this method did not work for me at the time. I was not able to read the piece. I believe this derives from my lack of context around their choreographic practice and from the cryptic nature of their performance. As explained in following sections, Burrows and Fargion’s pieces can be further unlocked when key aspects of their choreographic practice become evident.Footnote5

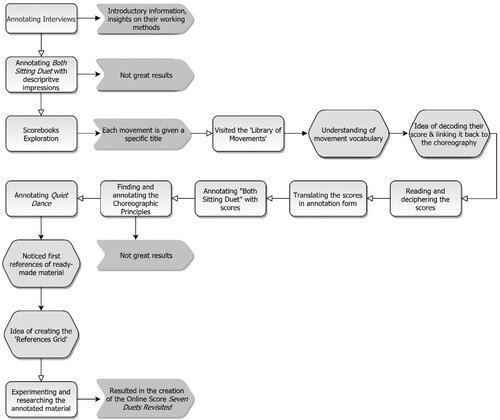

Figure 2. This flow chart illustrates the steps I took for this project. Rectangles depict actions, curved rectangles results, and hexagons key moments and ideas.

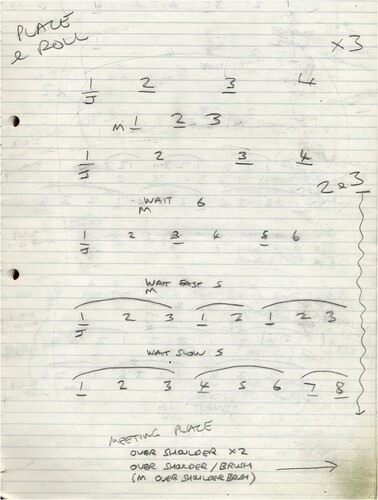

Considering the above, I tried a different approach and went back to the Seven Duets online publication to explore the ‘Score Books’ section.Footnote6 I started with the scorebook of Both Sitting Duet, to see how Burrows and Fargion scored movements and whether it would be possible to interpret their language. By spending time with the notebook, I understood that each movement was given a specific title, for example, ‘Brush Out’ and ‘Small Petals.’ The titles the makers give to their movements can sometimes be literal, and others quite abstract. For instance, the title ‘Place & Roll’ symbolises a literal placement and rolling of the hands. On the other hand, ‘Mad’ and ‘Double Mad’ stand for a sequence of movements of fist-clenching that does not portray what would be understood as a ‘mad’ dynamic.Footnote7 After getting acquainted with their movement vocabulary, it occurred to me the idea of decoding their score and linking it back to the choreography. My intention was to show the connection of their scorebooks – which are also present and visible on stage – with their movements.

Decoding their notation system

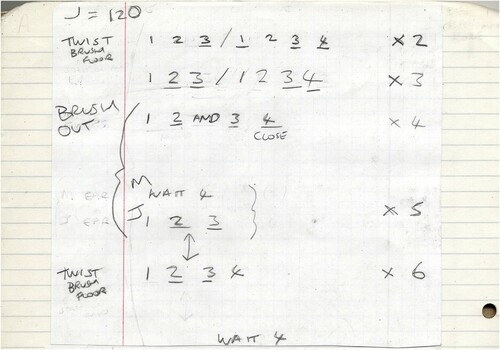

The annotation process started by creating timestamps in the moments I thought the movement combinations altered. The first movement of the first page, ‘Twist, Brush, Floor,’ was especially challenging to figure out. That is because I was unaware of the counted rhythm; hence, I could not make sense of where and when the scored movement began or ended. This is where the ‘Library of Single Movements’ helped a lot: ‘Twist, Brush, Floor’ was individually recorded so I could see exactly how they think about it.Footnote8 However, the second title, ‘Brush Out,’ made sense immediately because, in the score, there is the ‘x4’ sign (see ). This symbol made me imagine that Burrows and Fargion should perform this movement four times; and they did. In the next line, they score the same movement but differently (see ). There is an M (for Matteo) ‘WAIT 4’, and J (for Jonathan) ‘1 2_ 3_ x5.’ After figuring out this movement, I realised this was Burrows’ book and not Fargion’s. Burrows performs this movement five times while Fargion should wait for four counts. I then started interpreting the movements and their timings more easily.

Figure 3. First page of Burrows’s Both Sitting Duet scorebook. First movement: ‘Twist Brush Floor,’ second movement: ‘Brush Out’ – Digitised notebook by Motion Bank.

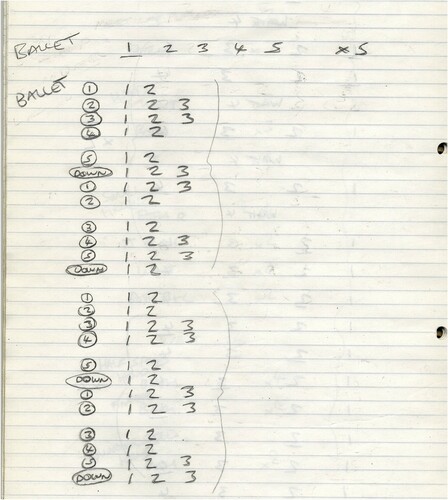

What also helped to comprehend their scores and annotate their performances was my music background and my experience in ‘decoding’ dance notation scores and systems.Footnote9 As expressed in their interviews, their counting is quite particular, they are not always showing the rhythm they are counting, but they are very much playing with it. According to Burrows, they are constantly contradicting rhythms and playing in the gaps of each other (Motion Bank Citation2013d). My dance background helped in decoding the scores by noticing some details in the names of the movements. For instance, in the movement ‘Ballet’ (See ), you can see that Burrows is passing through the classical ballet British arm positions (and not Russian) and that he names them as such in his scores.

Another critical part of the interpretation process was the realisation of the music element. In one of the interview snippets, Burrows and Fargion mention that Both Sitting Duet is a direct translation of the composer Morton Feldman’s For John Cage (1982) into choreographic patterns (Motion Bank Citation2013d). This sparked the idea to find the piece and listen to it in sync with the performance video. Watching the performance while listening to Feldman’s piece was, in a way, a ‘magical’ performance moment. Suddenly, what they describe in the interviews about how they work and about the ‘counterpoint’ element made sense. The first musical metres sync with the performance video and somehow make visible the dialogue between Burrows and Fargion. However, as the recording’s tempo is not the same as theirs, the synchronisation gets gradually lost, and it becomes impossible to synchronise long sequences. However, I think it is exciting to experience them simultaneously, even for a brief period of time.Footnote10

Annotating with scores

After being able to make sense of the scores, it was time to decide how to translate them into annotations. When beginning an annotating process, every person develops a personal system or uses another pre-existing one to make notes or note down fragments of movement. The most common way is to annotate with descriptions, impressions – in other words: written language that corresponds to what one is seeing in the video. However, I wanted to see their scores running alongside the choreography. I wanted to make visible which movement is happening at what time, read what they are reading, and get insights into how they think about their choreographic material along with language and scores.

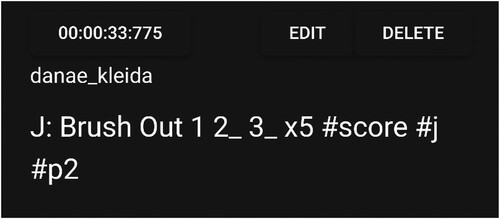

Although this was Burrows’ notebook, there were not only his movements inscribed but also many of Fargion’s movements. On that account, I decided to note ‘J:’ or ‘M:’ depending on whom this score and movement refer to. Following the name description, I annotated the main title of the movement, e.g. ‘Twist,’ and after this, the counting ‘1 2 3_’ with the underscore signing the dash they include underneath their numbers in the scorebooks (the underscore connected to the number it belongs to) (see ). Lastly, I added the times ‘x’ signifier, which is also inscribed in their notebooks (see and ). Since these were no longer descriptive annotations, I wanted to distinguish them from the previous annotations I had created. With Piecemaker, this can be done by creating a hashtag, e.g. ‘#score.’ That way, it is possible to filter and retrieve these specific entries at a later time ().

While creating the first score annotations, I realised that it would also be useful to note down which page the annotation refers to, thus I added the relevant hashtag (e.g. ‘#p1’). This became indeed useful when I showcased specific annotations in MoSys, the publishing tool of Motion Bank’s Web Systems. Next to this, I noticed that at times movements were not exactly performed, as noted in the scorebooks – or at least to my understanding of it. This finding piqued my curiosity to explore why or when this does happen. Hence, I added in the annotations the hashtag ‘#score’ (when in the scorebook) or ‘#notscore’ (when not in the scorebook) to help me explore this matter after finishing the annotation process. Following this series of actions, my annotations took their final form (see ).

Figure 6. ‘Place & Roll’ score from Jonathan Burrows’s Both Sitting Duet scorebook – Digitised notebook by Motion Bank.

Annotating the entire video performance of Both Sitting Duet took about four days of work. I tried to annotate all scored movements from Burrows’ scorebook, and in the end, I managed to decipher nearly all of them. Some movement combinations were exceptionally challenging to understand, e.g. ‘Place and Roll.’ Although the movement was clear, I could not make sense of how it synced with the scored counting and rhythm. An additional symbol that Burrows and Fargion use is an ellipsis above some of the numbers (see ). I believe that it represents the rolling movement they perform with their hands and the movement’s duration. However, this is one of the symbols that remained a mystery to me. ‘Double Mad’ was a movement impossible to understand, mostly because of its swift pace. However, it did not create an obstacle in the annotating process, as I could at least understand the duration it was taking in the scores and performance. ‘Clapping’ was also particularly difficult to understand because it was all based (probably) on their particular ‘communal’ rhythm and counting system, which I could not figure out.

At some point during the annotation process, I had to try the movements myself to decipher the scores and make sense of some of the movements. Otherwise, I could not find the moments the movement ended, and if my annotations were accurate enough. For instance, to understand the movement sequence ‘Flicks,’ I noted down on paper the detailed score of the movement ‘LRL/LRL/LRL/LLR/LLR/LLR/RLR/RLR,’ and then danced it with the recording of Burrows and Fargion.Footnote11 I danced several movements with them, such as ‘Flying,’ ‘Sign Language,’ ‘Yum,’ and ‘Counting Fingers,’ and while dancing with them, it was exciting to experience how some movement sequences were ordinary and easy to perform while others were quite complex. Nonetheless, the greatest difficulty I encountered decoding their scores was to tap into their counting technique and rhythm. It was manageable but also elusive.

Returning to the performance

Following this, I went back to watching the performance looking for little details, like movements, gazes, and other small moments that did not exist in the score. For instance, I observed the performance attentively and tried to see what took place on stage but was not recorded in the score. I annotated moments in which they look at each other, turn their gaze towards the audience, or laugh about what is happening on stage. I could not keep up annotating these moments for a long time due to two reasons. These movements lasted for a split-of-a-second, and they were becoming imperceptible in the form of annotation. Then, the annotations were so granular and frequent that the software was having issues handling them. However, I remembered Burrows and Fargion’s ‘Choreographic Principles’ and thought that perhaps all these moments that are not scored but seem so essential to their performance-making are the principles surrounding their choreographies. I decided then, to try and annotate these moments by identifying which principle was primarily evident at that moment. This exploration did not prove beneficial to the creation of annotations as there were not specific moments that I could link the principles to. However, having studied their ‘Choreographic Principles’ and keeping them in mind while watching them perform provided me with more profound levels of understanding. By looking at all these diverse brief happenings, such as gazes and pauses, through the lens of their principles, one can notice how these principles encompass their entire performative dialogue.Footnote12

Finding references

In the initial phases of this project, while annotating Burrows and Fargion’s interviews, they often mentioned that in their choreographies, there are many visible references playing a significant role in their creative practices. While annotating Both Sitting Duet, I had not noticed something specific to mirror this claim. However, when I annotated the performance, Quiet Dance, I noticed in the scorebook a reference to a movement named ‘Noces.’ When I reached the part of the performance that it belonged to, I realised it was referring to Bronislava Nijinska’s choreography Les Noces (1923). In this choreography, there are two quite recognisable movements for someone familiar with the performance and the era. ‘Noces’ stands for a three-step run with a leaning-forward torso and ‘Noces upright’ for a three-step sequence with fists held at ear-height.

This observation sparked the idea of creating with MoSys the grid of ‘References,’ a visual reference list for Burrows and Fargion’s choreographies. After observing the Les Noces reference, I went back to their interview videos and annotated moments in which they mention an inspiration, reference, or how they sometimes call it, ready-made material. Then, I tracked down these references and gathered a collection of material. In ‘References,’ visitors can find books, music, music videos, artwork, and choreographies that Burrows and Fargion mentioned as personal references that exist in their body of work. Next to the references, there are the interview excerpts in which Burrows and Fargion mention and discuss them. By clicking on the time-based annotations, visitors can watch the exact moments in which these references materialise in their performances in a (usually) modified variation. Ultimately, in this grid, users can simultaneously watch the references, the interviews in which they are mentioned, their ultimate actualisation on stage, and the scores that accompany them. As I will explain below, I believe that such a grid can quickly open up and make accessible insights into a body of work that is not so easily attainable as a performance spectator.

The online MoSys publication

Following the creation of the time-based annotations with Piecemaker, I used MoSys’s multimodalFootnote13 annotation environment and created an Online Publication that explores different aspects of Burrows and Fargion’s choreographic material and movement vocabulary. The Seven Duets Revisited begins with a starting grid that acts as the menu and entry point to other grids dedicated to a different exploration of the annotations, along with the performance material. There are grids that allow visitors to watch the performances Both Sitting Duet and Quiet Dance next to the score annotations. By clicking on each timestamped annotation, users can travel to the specific part of the video the annotations refer to.

The Online Publication includes grids such as the ‘Petal Exploration,’ for which I detected and then presented a recurring movement in Burrows and Fargion’s choreographies: the petal. The petal movement, a swirling gesture between the right and left arm, is included in their choreographies in many variations such as ‘Ordinary Petal,’ ‘Small Petal,’ ‘Big Petals,’ and ‘Small Low Petals.’ With this grid, users can watch all segments from Both Sitting Duet that include a petal movement, along with the respective score annotations. By doing so, visitors can observe the reciprocal relationship between scores and movements. That is to say, users can explore how various descriptors such as small, big, or small low affect the performance of movements and, at the same time, get a glimpse of how the makers think of them.

The grid ‘Principles’ presents Burrows and Fargion’s ‘Choreographic Principles.’ As mentioned above, it was not possible to link the principles with specific moments in the choreographies. However, this grid includes snippets of their interviews in which they explain in their own words how their ‘Choreographic Principles’ underlie and form their collaboration and how someone could observe them on stage. The following grid, ‘Making Sound,’ is dedicated to moments of Both Sitting Duet, during which Burrows and Fargion produce sound. Both Sitting Duet is surprisingly silent, hence, for this grid, I decided to find movements in which sound was created either inadvertently or because of body percussion, singing, clapping, and other ways employed.

Conclusion

The revisit of the original Seven Duets online score was initiated by the Motion Bank team’s interest in exploring how researchers can use MoSys to study and publish materials (Jenett Citation2021). I was invited to study the original online score and the collection of private research material Motion Bank holds. My research was performed by annotating video recordings with Piecemaker and using MoSys to explore relations between the material and publish my discoveries. The Seven Duets Revisited did not start with a well-defined methodology, that was invented as I went along. However, I would argue it took the act of annotation as the method to close study material, highlight specific aspects of it and then, enhance and contribute to the knowledge that surrounds it. It performs a further exploration of choreographic patterns while focusing on the relationship between scores and movement, intending to provide context around Burrows and Fargion’s performances.

As previously mentioned, for an annotation process to start, a personal or another pre-existing system need to be used. For this project, I used the actual scores of Burrows and Fargion, which I translated into their annotated version with Piecemaker. I find this practice of translating a choreographer’s notes and placing them next to the corresponding performance recordings to be interesting for researchers and visitors of the online scores. While annotating with Piecemaker, I studied closely various video recordings and gained valuable insights. Piecemaker allowed me to subject the recordings in multiple viewings, catalog my findings, and in this case, create score annotations. However, I am finding the interaction with MoSys’s environment and possibilities the most exciting part of the research trajectory. By placing the Piecemaker annotations next to other material, I made connections and discovered patterns between elements of Burrows and Fargion’s performance that would not be observable otherwise. For instance, grids such as ‘Making Sound’ and ‘Petal Exploration’ showcase in the same place moments that relate to each other depending on sound or movement quality.

Among the grids I created, I see ‘References’ as the key contribution of my research for understanding Burrows and Fargion’s body of work. The process of creating it showed me that had I not re-watched, annotated, and then researched these references, I would have lost a significant understanding of their performance-making. Using MoSys’s mood board environment, I was able to place material according to their conceptual proximity as expressed through a spatial proximity. The process of finding and placing the references next to their corresponding happening on stage helped me discover how Burrows and Fargion use ready-mades for their choreographic practice. Next to this, it gave me context about their statement in dancemaking and offered me the information I initially lacked to enter their language and performance world.

Next to this, ‘References’ is a meaningful example of the potentialities multimodal annotation unlocks. Dance and/or embodied knowledge have been a rather closed and incomprehensible field of knowledge (deLahunta in, ‘Brainstorm Session Expert Meeting Organized by Maaike Bleeker’ Citation2018). The creation of the ‘References’ grid showed me the endless possibilities multimodal annotation can provide to access and explore dance knowledge. From my perspective, multimodal annotation opens up and makes accessible bodies of work that can be intimate or difficult to access without already maintaining substantial knowledge of the field or makers. While designing the grid, I found diverse ways to close study movement material, play with it, and highlight unusual aspects of it. Having said this, I aspire that the visitors of the Online Score can access and unlock at their pace aspects of this work that would have been unattainable otherwise.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Danae Kleida

Danae Kleida is a researcher and teacher in the department of Media and Culture Studies at Utrecht University and a research assistant at Motion Bank. She is also a guest lecturer at the Academy of Theatre and Dance of the Amsterdam University of the Arts. She graduated from Utrecht University (NL) with a Research Master’s (cum laude) in Media & Performance Studies (2018). Before her post-graduate studies, she studied media and culture at Panteion University (GR) and classical ballet & contemporary dance. Her research revolves around media theory, early modern dance, early cinema, gestures, and motion documentation systems. Her master’s thesis examined historical methods of dance notation and current practices of digital movement annotation.

Notes

1 See (Motion Bank Citationn.d.).

2 See (Motion Bank Citationn.d.).

3 See (Rittershaus Citation2020).

4 See the Seven Duets Online Score (Motion Bank Citation2013c). http://scores.motionbank.org/jbmf/#/set/sets.

5 See the grid of ‘References’ in Seven Duets Revisited. http://scores.motionbank.org/jbmf-revisited/

6 A score book is a notebook in which an artist keeps personal notes, drawings, score etc. For the Seven Duets project, Motion Bank digitised 12 score books of Burrows and Fargion (Burrows and Fargion Citation2013). See, http://scores.motionbank.org/jbmf/#/set/score-books.

7 See the movement in ‘Segment 0’ in Seven Duets Revisited. http://scores.motionbank.org/jbmf-revisited/

8 In Seven Duets, there is a ‘Library of Movements’ from Burrows and Fargion containing a collection of single movements used in their performances. See (Motion Bank Citation2013a).

9 Previously to this project, I annotated films and dance performances with other platforms and tools such as Mediathread (‘Mediathread’ Citationn.d.), and PM2GO (Motion Bank Citationn.d.).

10 See Seven Duets Revisited. http://scores.motionbank.org/jbmf-revisited/

11 LRL stands for left-right-left. See (in ‘Both Sitting Duet’ Burrows and Fargion Citation2013, 23).

12 See ‘Principles’ in Seven Duets Revisited. http://scores.motionbank.org/jbmf-revisited/

13 With MoSys it is possible to annotate dance with images, sounds, links, videos, additional dance videos, other grids, and other media elements.

References

- “Brainstorm Session Expert Meeting Organized by Maaike Bleeker.” 2018. Documented by Danae Kleida. Utrecht, Netherlands.

- Burrows, Jonathan, and Matteo Fargion. 2013. “Seven Duets – Score Books.” 2013. http://scores.motionbank.org/jbmf/#/set/score-books.

- Burrows, Jonathan, and Matteo Fargion. 2020. “Joint Biography 2020.” 2020. http://www.jonathanburrows.info/#/text/?id=196&t=content.

- deLahunta, Scott. 2016. “Motion Bank: A Broad Context for Choreographic Research.” In Transmission in Motion: The Technologizing of Dance Maaike Bleeker, 128–138. Milton: Taylor & Francis.

- Jenett, Florian. 2021. “Dance, Cells and Grids: The Story of MoSys.” Medium, 24 January 2021. https://medium.com/motion-bank/dance-cells-and-grids-the-story-of-mosys-92d2fa284230.

- ‘Mediathread’. n.d. Accessed July 22, 2020. https://mediathread.info/.

- Motion Bank. 2013a. “Seven Duets – Library of Single Movements – Jonathan Burrows.” 2013. http://scores.motionbank.org/jbmf/#/set/jonathan-burrows-single-movements.

- Motion Bank. 2013b. “Seven Duets – Motion Bank.” 2013. http://scores.motionbank.org/jbmf/#/set/sets.

- Motion Bank. 2013c. “Seven Duets (2013) – Fragments, Movements and Insights from the Interplay between Jonathan Burrows and Matteo Fargion.” 2013. http://motionbank.org/en/content/jonathan-burrows-matteo-fargion.html.

- Motion Bank. 2013d. Jonathan Burrows and Matteo Fargion Interviews September 2013 on Vimeo. (Unpublished).

- Motion Bank. n.d. Motion Bank Web Systems. Accessed December 5, 2020a. https://app.motionbank.org/.

- Motion Bank. n.d. “PM2GO: Easy to Use Video Annotation Tool.” Accessed August 9, 2020b. http://motionbank.org/en/event/pm2go-easy-use-video-annotation-tool.html.

- Motion Bank. n.d. “The Motion Bank Project.” Accessed July 22, 2020c. http://motionbank.org/en.html.

- Rittershaus, David. 2020. “Introduction to Annotation as a Research Practice in Dance.” Medium, 31 March 2020. https://medium.com/motion-bank/introduction-to-annotation-as-a-research-practice-in-dance-3a0884c5d720.