ABSTRACT

Locative media art has been a popular topic to study, yet the focus tends to be on examining the artworks themselves, which have challenged us to think about the complex interrelations of space, place and time in novel ways. In this paper we offer a different view of locative media art by examining the community practices that can emerge through the production of this work. By highlighting how the social media platform, WhatsApp, facilitated communication and arts practice during a recent summer school on the theme of locative media, we demonstrate how cultures of enthusiasm can emerge from the adjacent digital spaces of locative media art. Our reflections highlight the ways that enthusiasm for locative media art and towards other participants was produced through WhatsApp spaces, through both enthusiastic language practices and atmospheres of enthusiasm. Ultimately, we aim to reveal that locative media is not only a technology that is used to shape our relationship to space, place and time, but that it is also a technology which encourages a set of community driven practices. In doing so we contribute to the literature on locative media art by giving attention to the communities of practice that form around it.

Introduction

A great deal has been said and written about location-based media-arts. This work has covered its inception during the situationist movement of the 1950s, its first period of audio-walking following the birth of portable audio devices in the 1970s, the spree of art works that followed the publication of Ben Russell’s Headmap Manifesto in 1999 (Russell Citation1999) and the public offering of GPS in 2000. In recent years, there has been a wide variety of mobile-led work following the popularisation of the smartphone and easy to use digital mapping software (see Hemment Citation2006; O'Rourke Citation2013; Townsend Citation2006; Tuters Citation2012; and Zeffiro Citation2012 for detailed genealogies and overviews).

Much of this work has asked important questions about how locative media and walking arts can (re)tune our attention to place and people (San Cornelio Esquerdo and and Ardèvol Citation2011), how it can be used to tell stories (Özkul and Gauntlett Citation2013), map sensations and emotions (Nold Citation2009), and engage us with the cultural heritage of place (Armstrong Citation2012). Further work has shown how locative media can shape the aesthetics and politics of place (Wilken Citation2020), provide a means to interact playfully with place (Hjorth Citation2011; Hjorth and Richardson Citation2014) and augment our socio-spatial relations in place (Gordon and de Souza e Silva Citation2011).

Throughout these studies, the multiple dimensions and temporalities of place as a socio-spatial, material and sensorial site of everyday life have been said to be exposed and laid bare by locative media technology through the ‘doubling of place’ (Moores Citation2012), the ‘augmenting of place’ (Graham, Zook, and Boulton Citation2013), the ‘layering of place’ (Didur and Fan Citation2018) and by revealing the ‘palimpsest of place’ (Frears, Geelhoed, and Myers Citation2017). In doing so, this work has brought together many disciplines to produce a rich interdisciplinary field of mediated place studies comprised of theories, methods and practices from across the arts, humanities and social sciences (de Souza e Silva and Sheller Citation2015; Rieser Citation2011; Wilken Citation2012; Wilken and Goggin Citation2015).

Readers will also note the close connection between how locative media art has understood place and how scholars of place and locative media have conceptualised place, as a multi-dimensional and always becoming space for life to emerge (see for example, Frith Citation2015; Thielmann Citation2010; Wilken and Goggin Citation2012, Citation2015). It should come as no surprise that the two can often be found working together. For example, Frears, Geelhoed, and Myers (Citation2017) represent a collective of artist-academics that developed a locative media project designed to challenge our thinking about place from a regional perspective.Footnote1

Today, it sometimes seems that there is little left say about locative media art, that there is not much left to add about how this seemingly simple but effective technology has significantly affected art works interested in exploring people’s engagement with place. And yet, as researchers still interested in the topic, we do not think now is the time to call it a day. Following Tuters (Citation2012) assertion that we should not be complacent with our modes of investigating locative media, that new technological iterations and practices constantly require us to refocus our attention in new ways, we propose asking different questions that begin to probe at the people and practices involved in producing and experiencing locative media art, and ask how and why these elements come to shape how locative media is being used. Building on Zeffiro’s (Citation2012) work, which proposed a different way of thinking about locative media, as an always-emerging field of cultural production, we seek to provide a socio-technical analysis of one locative media community to address how communities of practice are developing around locative media today.

At the same time that work on locative media and place has developed, so too has the work examining how communities of practice have been shaped by digital technologies (see Lippert Citation2013; Wenger, White, and Smith Citation2009). As digital technologies such as social media continue to proliferate in everyday life, we are witnessing more and more elements of community practice being shaped by a range of platforms. In this article we bring these two bodies of work together to highlight how locative media artist communities are being shaped by social media practices, and in our case study, by those mediated through WhatsApp. We argue that locative media art can emerge from a culture of enthusiasm that is developed through social media spaces, which are adjacent to the spaces of locative media technology itself – the mapping software, mobile hardware, sensor technology, etc. that are commonly associated with it. By doing so, we aim to add a further dimension to Wenger’s (Citation1999) notion that learning to become a community group happens through an engagement with social practices, by highlighting the role that enthusiasm – which we situate as an affective and socialising force – can play in bringing people together to learn and become a unified group.

In this paper we reflect on a recent summer school of our design, which explored how locative media could be used in a digital educational context during the COVID-19 pandemic, to highlight alternative ways that locative media might be studied. We argue that enthusiasm for locative media art and towards other participants, was produced through WhatsApp spaces, through both enthusiastic language practices and atmospheres of enthusiasm. Ultimately, we aim to reveal that locative media is not only a technology that is used to shape our relationship to place, but that it is also a technology that encourages a set of community driven practices.

The article is split into four sections. The first maps out our reading and use of enthusiasm, and how in recent years it has contributed to studies of community practice. Following this, we introduce our case study of a locative media summer school as a way into a discussion about how locative media artist communities emerged through different social media practices. We then discuss two examples from the school to show how enthusiastic language practices and atmospheres of enthusiasm can be shaped by WhatsApp and participating members. The first focuses on group conversations among the school participants, and the second on a walking activity that was developed during the course.

Enthusiasm

Building on the sociology of emotions (see Collins Citation1990; Hochschild Citation1979) Geoghegan (Citation2013) suggests enthusiasm is worthy of analysis when studying social groups and what holds them together. Situated within the field of emotions, enthusiasm can be understood as an affective force with varying degrees of intensity, which has the capacity to shape our experiences to each other and the world. To be enthusiastic about or towards someone or something is more than just an attachment; it is an affective attachment characterised by feelings and actions that demand a degree of interest, investment, care, excitement, passion, and joy, and result in atmospheres that can be characterised by feelings of belonging and togetherness. Like much of the work on emotions and affect (Ahmed Citation2004; Gregg and Seigworth Citation2010; Pile Citation2009), it is a concept that could easily be disregarded as a nebulous concept. It is without doubt, difficult to measure, describe or represent on the page. To discuss and reflect on enthusiasm is always as process of trying to evoke it, rather than represent it in full, which we understand as an impossibility due to the multi-sensorial form it can take as we are living it.

Examining what enthusiasm is or what it can do is perhaps best done by focusing on specific contexts or community practices. This can help us understand how it is manifested – enthusiasm towards what and for whom – and what affect it has in the world. Geoghegan (Citation2013), for example, has shown how enthusiasm for hobby’s can be seen to bind a group together. Her work on the socio-material practices of telecommunications and heritage leisure communities demonstrates how enthusiasm can produce a sense of belonging amongst group members. More recently, her work on museum curators (Citation2015) and that with citizen science groups (Everett and Geoghegan Citation2016) has demonstrated how enthusiasm is an affective force that flows through both the mundane and exciting socio-material practices of these communities, whether it be in regular group meetings or through everyday practices of curation and data collection. Taking up these ideas, Duggan (Citation2019) explored how cultures of enthusiasm emerged in the open-source humanitarian mapping communities. In his ethnographic analysis, he found that social bonds in this community were produced through a mix of enthusiastic atmospheres of place, shared understandings of worthy humanitarian causes and the shared material practices of digital map making. Collectively this work highlights how enthusiasm is both tied to specific places and practices, but also that it can be carried well beyond the sites in which it is associated with. Take for example, the enthusiasm one might feel towards a sports club and how that becomes a feeling that is carried through various socio-spatial practices including those far removed from the spaces associated with that club.

To date, there has been little analysis of how enthusiasm works through digital spaces, though there has been a considerable effort to understand how emotions and affect are translated through these spaces (see Serrano-Puche Citation2018). Gerbaudo (Citation2016) is one of the few to examine ‘digital enthusiasm’ on social media in relation to social movements. His study, which focused on emotional contagion within Facebook communities during the Arab Spring and Spanish Indignados movements of 2011, highlighted how enthusiasm can be used to frame an understanding about how and why people become involved in political and activist spaces online. Nevertheless, there has been no critical reflection that we can find on how enthusiasm plays a role in locative media artist communities, nor in how the social media platform, WhatsApp, might shape cultures of enthusiasm within this group.

With this in mind, we now turn to how enthusiasm towards locative media projects and each other emerged from the WhatsApp practices of our summer school participants. We argue that enthusiasm was nurtured through these social media spaces, specifically through language practices and a walking activity associated with the summer school curriculum. In doing so we build on the aforementioned studies by adding further reflection to how enthusiasm can be produced as it is directed towards something or someone, and how it can shape our experiences with each other and the world. Moreover, we contribute a reflective account of how social media shapes enthusiasm in terms of its production, affect and the geographies of those involved, which were globally distributed during the summer school. Firstly, however, we lay out the details of our summer school to provide some context for this discussion.

Locative Media for Earthlings in a Changing World

Between the 2nd-16th July 2020, thirty-six participants from around the world attended an online summer school entitled ‘Locative Media for Earthlings in a Changing World’.Footnote2 This course was designed and run by a four-person interdisciplinary team of academics and artists. Mike Duggan (an academic geographer), Fred Adam (an artist specialising in technology and ecology), and Geert Vermeire (a curator, artist and poet with a focus on spatial writing, locative sound & performance and social practices) were responsible for designing and running the course, and Cristina A. G. Kiminami (a PhD researcher) was responsible for auditing the course and writing an evaluation report.

Owing to the arts background of the organisers and the networks from which participants were recruited, the summer school participants were mainly artists, designers and scholars that were interested in locative media, mobility and technology. The main focus of the course was organised around a group activity whereby six groups of six people were tasked with designing and remotely creating a locative media artwork with a mobile/desktop locative media software, called CGeomap.Footnote3 These groups were curated by the course designer's and intentionally made up of experienced practitioners of locative media through to moderate users and those that had little to no experience in using it. Many of the participants had a background in walking and site-specific art, whilst others came from backgrounds in geography, sociology, archaeology and urban planning. Each group was given access to an online workflow tool (Trello) to aid collaboration, and a WhatsApp group was set up for each group to provide a means of communication between members.

Participants were asked to create locative media projects that addressed the four key themes of the school; place, (im)mobility, climate change and COVID-19, by combing site specific stories, texts, images and sounds on an interactive online map.Footnote4 This activity ran for the duration of the course and was supplemented by online guest lectures, group seminars and social gatherings held through video conferencing platforms. The result was an intensive period of learning and knowledge exchange amongst participants, guest lecturers and organisers.

Cumulatively, the summer school gave us a window into the world of locative media communities, which would become significant for shaping our understanding of who was using the technology for their practice, and how and why it was being used. In the following we reflect on this community by drawing from our observations and a participant survey. By doing so, we offer a different view of locative media practices, which has tended to focus on the artworks rather than the communities that produce them.

An audit was carried out by Cristina A. G. Kiminami throughout the course, which culminated in a written report that evaluated all the activities of the course, and took qualitative and quantitative note of participant engagement throughout the various sessions. In addition, a survey was sent to all 36 participants, from which we received 15 responses. The objective, at first, was to gather feedback and identify aspects that needed improvement and to provide more information for the evaluation report. Nevertheless, drawing from these responses and our observations, we began to understand how enthusiasm become central to how participants experienced the course.

The following is a critical reflection and not an out-right empirical study. It is limited by the specific time frame, scale of the course, and our interpretation of it. However, our intention here is not to provide generalisations about the locative media arts community, but rather to provide a snapshot of how a locative media community of practice formed and acted over the duration of this course. This follows Zeffiro’s assertion that ‘locative media is a field of cultural production that is perpetually evolving and continuously reproduced vis-à-vis struggles between technological interpretations and different visions of future use’. (Citation2012, 251). Our analysis is based on one locative media community emerging at a particular moment in time. Moreover, because the course coincided with home and remote working, it certainly offers different aspects when compared to courses or events held in other time-spaces where physical interaction in the norm.

We believe our approach, albeit over a relatively short period of time and taking place in a socially distanced world, offers a view into locative media community practices that other methods do not. Moreover, as we were both participants ourselves in the summer school, we were afforded a view from the inside, which significantly shaped the way we understood how enthusiasm towards the project work emerged. As discussed above, enthusiasm can be considered an affective force that is difficult to study and represent. By being active participants in the school, we were in a position where the affective force of enthusiasm could be felt and experienced by ourselves. The following reflections must be read with this in mind; what is represented on these pages cannot fully convey the enthusiastic practices that we were witness to, but we hope that we can go some way to evoking a sense of enthusiasm felt by us and the course participants ().

Languages of enthusiasm: WhatsApp conversations

From all the platforms utilised during the summer school, WhatsApp is the one that caught our attention, simply because it was the platform that participants engaged with the most. This was not surprising considering how the platform has permeated social communications over the past decade. WhatsApp has evolved considerably during this time and now has a host of features and functions that make it attractive for many different forms of communication. Following Madianou and Miller (Citation2013) theory of polymedia, which highlights how social media offers a range of socio-technical affordances that can be used to shape communication, WhatsApp has multiple features and functions that users can take into account when communicating with others in a diverse range of social situations. In the following, we will show how these affordances were used to shape communication and enthusiasm amongst our group of participants. Similarly, this follows Jason Farman, who states that, ‘Mobile interfaces are often designed with particular uses in mind; however, our practices dictate the role the technology will play in culture and in the relationship between individual and community modes of engagement’ (Citation2012, 120).

At the beginning of the event, a WhatsApp group was set up for each of the six groups participating in the course. Included in each group were six participants, all course leaders and ourselves. Not knowing exactly how this form of communication would work for people in different countries, time zones, with different backgrounds and ways of working, it was always going to be an experiment that worked for some and not for others. Generally, most of the groups used the tool to greet and get to know each other at first, and then for exchanges about the project work. Throughout the two weeks we saw flurries of activity leading up to key points in the project work, and lulls in activity on quieter course days (e.g. Sundays or a day without a scheduled lecture). As the course went on, collegial atmospheres could be seen emerging in each of the groups as they worked towards their project goals. In and amongst the administrative messages for setting up video conference calls and sharing documents, was a lot of mutual respect and admiration for each other’s contributions. We assumed this was the norm for a group of strangers working together for the first time, which is something evidenced in other studies of WhatsApp groups where social support was found to be a common element of this social media (see Gazit and Aharony Citation2018). Elsewhere, Cetinkaya (Citation2017) has argued that social media platforms are increasingly permeating the education process. They suggest ‘[…] these applications have potential to increase learning, learners’ being active in their studies, interaction between students on personal, school, and course related topics, create sense of belonging, eliminate social barriers, and increase students’ motivation’. (Cetinkaya Citation2017, 60).

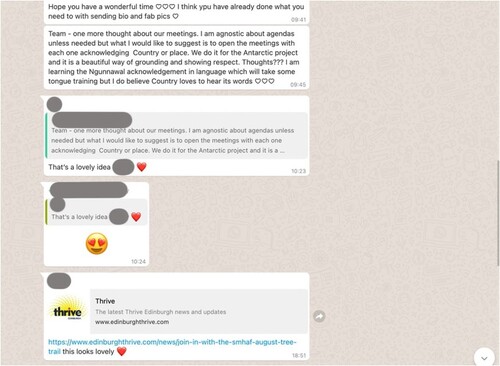

There was one group, which we will call the Earth team, made up of six women of varying ages based in Europe and Oceania, where a sense of excitement and enthusiasm for the topic and the project work was much more palpable than the others. This group exchanged 10s and sometimes 100s of messages each day, all throughout the day and night. Coming from a range of time zones, it sometimes seemed that the ping of new messages was non-stop. Developed within this flow of synchronous and asynchronous communication were a set of shared norms, practices and a sense of enthusiasm that the work being produced satisfied their reasons for joining the course. This was fostered through the sharing of ideas, expertise and encouragement, as well as through the sharing of images, sound clips and short videos. The following is taken from a discussion about the course project and is just one example of these enthusiastic exchanges in the WhatsApp group:

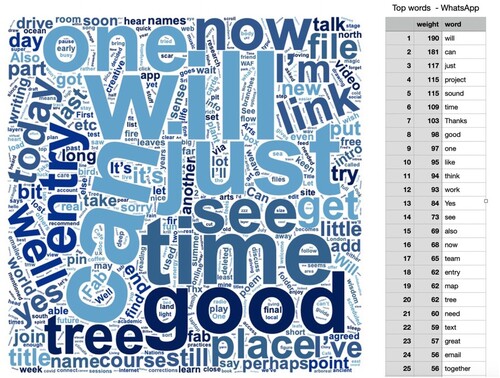

From this stream of messages, we can see a lively exchange of text and symbolism that captures how enthusiasm in this group emerged through WhatsApp. The tone of this discussion is similarly expressed in the word cloud created from the entire group chat (see ). With the consent of all members of the group, we downloaded the entire exchange, anonymised it, and created a text file from which the word cloud was produced. From the 25 most frequently used words in the chat, the top nine words could all be regarded as carriers of enthusiasm. They are Will; Can; Thanks; Good; Like; Yes; Team; Great; Together. These, from our observations, are words that helped produce an atmosphere of positivity and collectiveness amongst the group.

Figure 2. This word cloud was generated from all the content in the Earth team’s WhatsApp chat. The 25 most frequently used words can be seen in the table to the right. (n.b this word cloud was created after cleaning the WhatsApp data of names, times, dates and connective words) Footnote6

This selective evidence offers us a different lens to understand social bonds compared to the aforementioned work on enthusiasm, which is largely based on an analysis of people congregating in offices, workplaces and concrete community spaces. Here we observed how digital messaging spaces create new ways for enthusiasm to bond a group together; through the asynchronous and synchronous exchange of information, images, encouragement, pleasure, respect and affinity for one another.

In two further examples (see and ), we can see how a similar sense and manifestation of enthusiasm shaped and evolved to a shared consensus about the project work. In these cases, we can see a shared affinity for the recognition of place and the importance of acknowledging land rights for Indigenous people(s). It has been fostered here as part of a community led discussion, whereby the language used evokes a sense of enthusiasm towards this work.

Paolo Gerbaudo (Citation2016) has examined ‘moments of digital enthusiasm’ to understand how emotional responses to protest movements can become contagious on social media. Albeit in a different context, using different methods, we see something similar happening here, as the group develops an affinity for a way to acknowledge the land rights of people and the places that they are speaking from. Once a member introduces the notion, the group comes together, and an emotional response is collectively formed with language and emojis. By the time this flow of messages ends with ‘important work for us all’, the group appears unified in their decision on how to acknowledge land rights of Indigenous people(s).

Unlike Gerbaudo’s finding that moments of digital enthusiasm can be short lived, there is evidence that this has not been the case with this particular group who, at the time of writing, over a year later, continue to engage enthusiastically with each other on the platform. Nevertheless, this group does follow Gerbaudo’s assertion that enthusiasm on social media is represented by peaks and troughs of activity that we might define as enthusiastic. There were, for instance, flows of messages that we could have shown that we much more subdued in tone, for example about the practical information relating to the course and project. Following Anderson’s (Citation2009) work on affective atmospheres, we suggest that there were varying intensities and temporalities to the way that the atmosphere of enthusiasm was manifested via the WhatsApp group chat. Some of the group’s chat would not be regarded as having a quality of enthusiasm towards the project or each other, whereas other parts such as those shown above could be regarded as having enthusiastic qualities. Ultimately, we cannot be sure how these varying intensities of enthusiasm were precisely felt by all members of the group, nor make a judgement on how long these atmospheres of enthusiasm were held together. However, from our view as participant observers, we certainly felt the ebb and flow of these enthusiastic intensities as they came and went throughout the duration of course.

So far, we have shown how enthusiasm flows through digital spaces in the form of language (text and symbols) shared on WhatsApp. In the following we turn our attention to a different context, when other forms of representation (photography, video, audio) were used to shape an atmosphere of enthusiasm in a synchronous walking activity mediated by WhatsApp. The point here is to demonstrate that digital enthusiasm and its affects are produced through socio-material practices that are not restricted by the spaces of the app, thus providing further evidence that social media spaces are always-already materially produced (see, for example, Hine Citation2015; Van Doorn Citation2011).

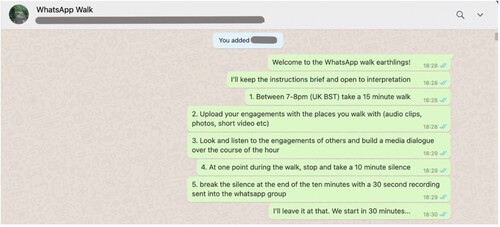

Atmosphere of enthusiasm: the WhatsApp walk

By the middle of the course, a common interest on the themes of ecology, arts and walking had been established. With the help of a guest lecturer on the course, the decision was made to organise a collective walking activity, to be carried out synchronously via WhatsApp over one hour. This was seen as an experiment in what we could do with the technology, people and pandemic context that we were living with at the time. WhatsApp was chosen specifically because it was familiar to our participants and could be used to simultaneously share messages, photos, audio recordings and videos.

We created a WhatsApp group, and issued the following instructions to 17 of the course participants who had signed up for the activity (see ):

In an intense one hour period of sharing, the walk produced a total of 135 audio and visual files and a stream of messages (see for a selection of composite images). Taken together, these media could be said to further reinforce the sense of community and enthusiasm amongst the group. After the walk, a video was created by Cristina A. G. Kiminami containing all photos, sounds and videos that were captured during the virtual activity (https://vimeo.com/500868218). The idea in creating the video was not only to generate a record of all the media that was produced but also to demonstrate the synchronicity and collaboration of the walking practice. The result was a video of almost six minutes long that was shared in the same WhatsApp group to all participants of this particular activity. It goes someway to showing how the walk unfolded between us and aims to evoke the enthusiasm for the activity in ways that add a further dimension to language practices discussed above.

Having both joined this walk, we can attest to the feelings of connection we experienced during the activity. Knowing that there was a group of us all walking at the same time, but in different places and time zones, created a shared atmosphere; at once an attachment to place and a feeling of distributed placelessness. During the pandemic lockdowns, we had all become very accustomed to walking around our local areas, but this felt distinctively different. We were given an opportunity to share our usually isolated walks with a group of strangers at a distance. This affective attachment to each other was discussed in later conversations as a special moment shared by the group of participants, and for us was one of the highlights of the course. It is once again difficult to convey exactly how enthusiasm for the walk was experienced by those involved, but we ask readers to watch the video to get a partial sense of how enthusiasm for the activity was expressed through WhatsApp. Clearly there is no way a video or WhatsApp transcript could completely convey the experience, nor is there a definitive way to label this activity purely based on our notion of enthusiasm. As many others have recognised, there are limits for language and visual media aiming to reflect intangible experiences and atmospheres (Vannini Citation2015).

Our walk follows a growing trend in mediated walking activities, spurred on by the global pandemic, that bring people in different space-times together through walking (see for example, the work of Blake Morris;Footnote5 Rose Citation2021). The act of walking alone but together through WhatsApp is said to reshape the space-times of walking in a different way than if we had all been walking together in person. As Rose notes, ‘walking together yet apart enables new, different connections, and the experience will shape my future psychogeography practice (Citation2021, 2014). We add a further dimension to this by foregrounding how enthusiasm for the walk (and towards each other) can be produced through these different connections. Hardley and Richardson (Citation2020) have written recently about how ‘stay home orders’ during the Covid-19 pandemic encouraged them to reckon with the ways that mobile media were used in ways that redefined the ‘net-localities’ (after Gordon and e Silva de Souza Citation2011) of domestic spaces. Writing about a similar time, the WhatsApp walk highlights how mobile media can also be used very locally to home (as was the case in most of our participants’ walks) and yet shape the ‘net-localities’ of others across time and space.

We could also say that the WhatsApp walk resembled a collective dérive in an era of digital culture. There is a long history to collective walking practices. Since the 1920s, starting with the Dadá movement, the act of walking started being appreciated as an art form. This was developed by the Situationists, an artistic movement of the 50's-60's, by positioning walking and wandering as an act of psychogeography. Guy Debord, one of the main protagonists of the Situationists, famously introduced the notion of the dérive (or the drift) as a way to conceptualise walking as an act of urban subversion, a remapping process aimed to disturb the common sense of spatiality in the city. For Debord, psychogeography was as real and accurate as maps that characterise cities and traditional geopolitical forces. Differently from the surrealists, the situationists presented drifting as experimentation of new spatial behaviours.

Today, this concept has become an umbrella for various contemporary walking arts and practice, much of which utilises locative media technology and has focused its attention on the mediated dérive as a political act of subversion towards cartographic and Euclidean urban norms (Pinder Citation2013; Tuters Citation2012). There is little recognition, however, that the dérive can also be an act of community bonding in this context. This is despite the fact that much locative media art is intentionally designed so that is experienced by groups of people walking together. Our WhatsApp walk was as much about sharing a moment together, each in our own situ, using the technology in a way that suited our ways of walking and communicating, as it was an exercise in subverting the social norms and practices of our local streetscapes. This approach is more in line with those that situate walking as an everyday socio-technical practice shaped by places, bodies and technologies (see Ingold and Vergunst Citation2008).

Finally, digitally mediated and synchronous group walks are further examples of practices that blur the lines between online and offline space. Though already debunked as a problematic binary (see Kinsley Citation2014; Leszczynski Citation2015), the act of walking alone-together through WhatsApp demonstrates how digital spaces are never only produced through the interfaces of the screen, even if that’s how they tend to be experienced and perceived (Berry Citation2014). As we demonstrate, they are instead produced at the point of multiple socio-material trajectories, assembling at the very least, corporeal movements, embodied experiences, environments, social norms and practices, media practices, interfaces and networked infrastructures. This further distorts the arguments that digital and global media simply lead to the death of distance because it highlights the ways that distance (and time) can be made meaningful in creating a sense of community through social media.

Conclusion

By reflecting on how WhatsApp was used to shape a locative media summer school community, we have shown how artist-academic communities can be bound together by a form of digitally mediated enthusiasm, which we saw manifest in language practices of group chats and the atmosphere produced during a mediated walking activity. In doing so we have examined locative media art as a socio-technical practice rather than concentrate on a finished piece of locative media artwork. This follows Couldry’s (Citation2012) assertion that media practices matter, and offers up a different account to those usually given to locative media art.

We believe that focusing on enthusiasm as a form of online engagement (but not fully representative of it) can open up new areas in the field of locative media arts and research. In studies of location-based services (LBS) more broadly, for example in studies of LBS games such as Pokémon Go (see Evans and Saker Citation2019; Hjorth and Richardson Citation2017), we have seen similar attempts to study community practices. We see no reason why this cannot also be done for studies of locative media art communities, which includes both artists, participants and the institutions and organisations that support them. Exploring the community dynamics of these groups using a guiding criteria of enthusiasm such as that presented in this paper may open us up to different ways of examining them and their work.

We have also shown how communities that use locative media for their work are also bound to other media ecologies that, in this case, encompassed the multi-functionality of WhatsApp. The ‘polymedia’ practices that are found in other areas of social life (Horst and Miller Citation2012) are equally present in the groups we reflected on here. Nevertheless, rather than focusing on different media platforms and how their affordances are realised by different social relations and situations, we have shown how one social media platform can have a diversity of internal affordances. In this case, we highlighted how WhatsApp affords different forms of language communication, media exchanges and synchronicity. By doing so, we suggest that research into polymedia should further consider the role of the internal affordances of social media platforms and how they shape enthusiastic social practices as one form of online engagement. As social media platforms continue to develop ever more functionality and centralise integration with other services, ideas of polymedia need to adapt to the changes in the technology and how they are used. Indeed, it is the goal of many technology companies to be the go-to app for all online interactions (see for example WeChat and it’s collection of ‘mini programs’) and our modes of enquiry should adapt to these changes. We have presented some reflections in the context of locative media art communities, but we also see this approach being useful for understanding enthusiastic community practices elsewhere.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our thanks to the two anonymous reviewers of this article, whose comments greatly improved its focus and direction. We also thank Fred Adam, Geert Vermeire and all of the summer school participants, without which our interest in enthusiasm towards locative media would not have been recognised.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cristina A. G. Kiminami

Cristina A. G. Kiminami is a PhD candidate in the Department of Digital Humanities at King's College London. Her previous research experience was in digital counter-cartography practice by contemporary artists and activists. Her current research is on spatial humanities, digital mediation relations and people perception of urban surroundings. Her Master's and Bachelor's Degree from the University of São Paulo on Architecture and Urbanism.

Mike Duggan

Mike Duggan a cultural geographer and a Lecturer in Digital Culture, Society and Economy in the Department of Digital Humanities, King's College London. He has a PhD from Royal Holloway University of London, working in partnership with the Ordnance Survey on studying everyday digital mapping practices. He is primarily interested in the tensions and contradictions that emerge when we examine how digital society and technology is theorised alongside how everyday life is lived. He is the editor-in-chief of the Livingmaps Review, a bi-annual journal for radical and critical cartography, and a member of the recently established Mapping Futures Imaginaries network.

Notes

1 Based on an analysis of Hayle Churks app, created by Lucy Frears (see https://www.hayletowncouncil.net/2016/12/free-hayle-churks-mobile-app-on-itunes/).

2 The course was part of a wider research project called ‘Locally-global spatial narratives: exploring the potential of locative media as an educational tool for understanding climate change and forced migration’. Initially the summer school was designed to be held in a classroom setting in London, but due to COVID-19 we were forced to shift to an online-only model. By doing so we were able to attract participants from around the world, including people from Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, Sri Lanka, Switzerland, the UK and the USA. All participants are anonymised in this analysis and have given us permission to use data collected about them during the course. The course and wider project have undergone and passed an internal ethical review process at King’s College London (ref: MRA-19/20-18577).

3 CGeomap is a locative media and mapping platform. See https://cgeomap.eu for details.

4 To see the finished map, see https://cgeomap.eu/earthlings/.

6 The process of formatting the word cloud graph of this particular WhatsApp group (Earth Team) we started by exporting the conversation from a feature of the App itself into a text format. Subsequently, we began the process of withdrawing from the file: names of participants, numbers, media (photos/videos/audios) and websites links. This step was fundamental in order to keep the material focused as much as possible in the written content of the conversation and avoid multiples names and numbers of participants that are commonly exported from the WhatsApp. Ultimately, after the file was ready, the word count and the word cloud graph were possible to be created.

References

- Ahmed, S. 2004. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. New York: Routledge.

- Anderson, B. 2009. “Affective Atmospheres.” Emotion, Space and Society 2 (2): 77–81.

- Armstrong, N. 2012. “Historypin: Bringing Generations Together Around a Communal History of Time and Place.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 10 (3): 294–298.

- Berry, D. 2014. Critical Theory and the Digital. London: Bloomsbury.

- Cetinkaya, L. 2017. “The Impact of Whatsapp Use on Success in Education Process.” International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 18 (7): 59–74.

- Collins, R. 1990. “Stratification, Emotional Energy, and the Transient Emotions.” In Research Agendas in the Sociology of Emotions, edited by T. D. Kemper, 27–57. New York: State University of New York Press.

- Couldry, N. 2012. Media, Society, World: Social Theory and Digital Media Practice. London: Polity.

- de Souza e Silva, A., and M. Sheller. 2015. Mobility and Locative Media Mobile Communication in Hybrid Spaces. London: Routledge.

- Didur, J., and L.-T. Fan. 2018. “Between Landscape and the Screen: Locative Media, Transitive Reading, and Environmental Storytelling.” Media Theory 2 (1): 79–107.

- Duggan, M. 2019. “Cultures of Enthusiasm: An Ethnographic Study of Amateur Map-Maker Communities.” Cartographica 54 (3): 217–229.

- Evans, L., and M. Saker. 2019. “The Playeur and Pokémon Go: Examining the Effects of Locative Play on Spatiality and Sociability.” Mobile Media & Communication 7 (2): 232–247.

- Everett, G., and H. Geoghegan. 2016. “Initiating and Continuing Participation in Citizen Science for Natural History.” BMC Ecology 16 (1): 13.

- Farman, J. 2012. Mobile Interface Theory: Embodied Space and Locative Media. New York: Routledge.

- Frears, L., E. Geelhoed, and M. Myers. 2017. “Performing Landscape Using Locative Media Deep Map App: A Cornish Case Study.” In Reanimating Regions: Culture, Politics, Performance, Chapter 15. London: Routledge.

- Frith, J. 2015. Smartphones as Locative Media. Cambridge: Polity.

- Gazit, T., and N. Aharony. 2018. “Factors Explaining Participation in WhatsApp Groups: An Exploratory Study.” Aslib Journal of Information Management 70 (4): 390–413.

- Geoghegan, H. 2013. “Emotional Geographies of Enthusiasm: Belonging to the Telecommunications Heritage Group.” Area 45 (1): 40–46.

- Geoghegan, H. 2015. “Object-love at the Science Museum: Cultural Geographies of Museum Storerooms.” Cultural Geographies 22 (3): 445–465.

- Gerbaudo, P. 2016. “Rousing the Facebook Crowd: Digital Enthusiasm and Emotional Contagion in the 2011 Protests in Egypt and Spain.” International Journal of Communication 10: 254–273.

- Gordon, E., and A. de Souza e Silva. 2011. Net Locality: Why Location Matters in a Networked World. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Graham, M., M. Zook, and A. Boulton. 2013. “Augmented Reality in Urban Places: Contested Content and the Duplicity of Code.” Transactions for the Institute of British Geographers 38 (3): 464–479.

- Gregg, M., and G. J. Seigworth. 2010. The Affect Theory Reader. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Hardley, J., and I. Richardson. 2020. ‘Digital placemaking and networked corporeality: Embodied mobile media practices in domestic space during Covid-19’, Convergence (online first) December 2020.

- Hemment, D. 2006. “Locative Arts.” Leonardo 39 (4): 348–355.

- Hine, C. 2015. Ethnography for the Internet: Embedded, Embodied and Everyday. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hjorth, L. 2011. “Locating the Online: Creativity and User-Created Content in Seoul.” Media International Australia 141: 118–127.

- Hjorth, L., and I. Richardson. 2014. Gaming in Social, Locative and Mobile Media. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hjorth, L., and I. Richardson. 2017. “Pokémon GO: Mobile Media Play, Place-Making, and the Digital Wayfarer.” Mobile Media and Communication 5 (1): 3–14.

- Hochschild, A. R. 1979. “Emotion Work, Feeling Rules, and Social Structure.” American Journal of Sociology 85 (3): 551–575.

- Horst, H. A., and D. Miller. 2012. Digital Anthropology. London: Berg.

- Ingold, T., and J. L. Vergunst. 2008. Ways of Walking: Ethnography and Practice on Foot. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Kinsley, S. 2014. “The “Matter” of Virtual Geographies.” Progress in Human Geography 38 (3): 364–384.

- Leszczynski, A. 2015. “Spatial Media/Tion.” Progress in Human Geography 39 (6): 729–751.

- Lippert, M. 2013. Communities in the Digital Age Towards a Theoretical Model of Communities of Practice and Information Technology. PhD Thesis. Företagsekonomiska institutionen Department of Business Studies. Uppsala University.

- Madianou, M., and D. Miller. 2013. “Towards a New Theory of Digital Media in Interpersonal Communication.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 16 (2): 169–187.

- Moores, S. 2012. Media, Place and Mobility. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nold, C. 2009. Emotional cartography: Technologies of the self. www.emotionalcartographies.net.

- O'Rourke, K. 2013. Walking and Mapping: Artists as Cartographers. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Özkul, D., and D. Gauntlett. 2013. “Locative Media in the City: Drawing Maps and Telling Stories.” In The Mobile Story: Narrative Practices with Locative Technologies, edited by J. Farman, 113–127. London: Routledge.

- Pile, S. 2009. “Emotions and Affect in Recent Human Geography.” Transactions for the Institute of British Geographers 35: 5–20.

- Pinder, D. 2013. “Dis-Locative Arts: Mobile Media and the Politics of Global Positioning.” Continuum 27 (4): 523–541.

- Rieser, M. 2011. The Mobile Audience: Media art and Mobile Technologies. New York: Rodopi.

- Rose, M. 2021. “Walking Together, Alone During the Pandemic.” Geography (sheffield, England) 106 (2): 101–104.

- Russell, B. 1999. Headmap Manifesto. http://www.technoccult.net/wpcontent/uploads/library/headmap-manifesto.pdf.

- San Cornelio Esquerdo, G., and E. and Ardèvol. 2011. “Practices of Place-Making Through Locative Media Artworks.” Communications 36 (3): 313–333.

- Serrano-Puche, J. 2018. “Affect and the Expression of Emotions on the Internet: An Overview of Current Research.” In Second International Handbook of Internet Research, edited by J. Hunsinger, L. Klastrup, and M. Allen, 529–547. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Thielmann, T. 2010. “Locative Media and Mediated Localities: An Introduction to Media Geography.” Aether: The Journal of Media Geography 5 (a): 1–13.

- Townsend, A. 2006. “Locative-Media Artists in the Contested-Aware City.” Leonardo 39 (4): 345–347.

- Tuters, M. 2012. “From Mannerist Situationism to Situated Media.” Convergence 18 (3): 267–282.

- Van Doorn, N. 2011. “Digital Spaces, Material Traces: How Matter Comes to Matter in Online Performances of Gender, Sexuality and Embodiment.” Media, Culture & Society 33 (4): 531–547.

- Vannini, P. 2015. Non-Representational Methodologies: Re-Envisioning Research. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Wenger, E. 1999. Communities of Practice Learning, Meaning, and Identity - Learning in Doing: Social, Cognitive, and Computational Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wenger, E., N. White, and J. D. Smith. 2009. Digital Habitats: Stewarding Technology for Communities. Portland: CPsquare.

- Wilken, R. 2012. “Locative Media: From Specialized Preoccupation to Mainstream Fascination.” Convergence 18 (3): 243–247.

- Wilken, R. 2020. Cultural Economies of Locative Media. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wilken, R., and G. Goggin. 2012. Mobile Technology and Place. London: Routledge.

- Wilken, R., and G. Goggin. 2015. Locative Media. London: Routledge.

- Zeffiro, A. 2012. “‘A Location of One’s Own: A Genealogy of Locative Media’.” Convergence 18 (3): 249–266.