ABSTRACT

Site-specific performances are shows created for a specific location and can occur in one or more areas outside the traditional theatre. Social gathering restrictions during the Covid-19 lockdown demanded that these shows be shut down. However, site-specific performances that apply emergent and novel mobile digital technologies have been afforded a compelling voice in showing how performance practitioners and audiences might proceed under the stifling constraints of lockdown and altered live performance paradigms, however they may manifest. Although extended reality (XR) technologies have been in development for a long time, their recent surge in sophistication presents renewed potentialities for site-specific performers to explore ways of bringing the physical world into the digital to recreate real-world places in shared digital spaces. In this research, we explore the potential role of digital XR technologies, such as volumetric video, social virtual reality (VR) and photogrammetry, for simulating site-specific theatre, thereby assessing the potential of these content creation techniques to support future remote performative events. We report specifically on adapting a real-world site-specific performance for VR. This case study approach provides examples and opens dialogues on innovative approaches to site-specific performance in the post-Covid-19 era.

1. Introduction

The Covid-19 coronavirus was first identified in December 2019, resulting in a sustained global pandemic. In the following weeks – January through April 2020 – the virus spread throughout the globe, causing governments to issue strict lockdown guidelines to delay the spread of the virus. Since then, the pandemic and lockdown have drastically disrupted society. Among the economies catastrophically affected by the restrictions is the live performance sector. The impact on theatre and its stakeholders has been substantial, and as a result, in 2020, the global live events industry collapsed. In a worldwide context, it is estimated that in the eight months that the sector ‘remained dark’ (April – December 2020), artists, technicians, and industry professionals suffered a combined loss of $9bn (August Brown, Los Angeles Times), with other economists insisting that the figure is as high as $10bn (Brambilla Hall Citation2020).

In an Irish context (the focus of the presented research), over 12,000 cultural events were cancelled, and about 10,000 directly related contract-based jobs, to the value of more than €10 million in revenue, were lost (Gaffney Citation2020). Deirdre Falvey (of the Irish Times) says: ‘The ‘arts recession’ will be five times worse than the rest of the economy … Recovery may take until 2025 as the sector is hit far harder than other areas of the economy’ (Falvey Citation2020). Therefore, in 2020/21, not only has there been a biological pandemic but so too has there been what may be described as a psycho-social pandemic, that is, a sociological pathology that has affected individuals and collectives similarly all over the globe. This pandemic-induced tension is constituted by a pathology that manifests the psychological traumas suffered by communities due to the isolation, loneliness and deprivation of the right to work, all stemming from the cancellation of all collective gatherings and public events involving physical presence. More-or-less, the psycho-social pandemic covered the entire globe in the space of 88 days – from January 21st to April 18th, 2020 (Hale et al. Citation2021). Since then, the industry was shut for about 18 months, depending on the country.

The effect of the Covid-19 lockdown on the mental and emotional health of the general public has been documented in numerous studies (Fiorillo and Frangou Citation2020; Kelly Citation2020; Singh et al. Citation2020; Ahrens et al. Citation2021). Currently, there is very little research specifically concerning the closure of theatres and cultural institutions. However, one apt quantitative study relates expressly to the mental health of performing arts students between September 2019 and May 2020. Stubbe et al. (Citation2021) clearly show that mental health complaints were ‘significantly higher during the Covid-19 lockdown compared to the two pre-Covid-19 periods.’ Additionally, professional-sector publications featuring subjective opinions of industry experts maintain that ‘theatre workers are facing long-term mental health problems' because many are at an all-time psychological low (Masso Citation2021). Our presented research practice resoponds to this situation of acute depression endured by artists and cultural actors in the event of their being silenced or rendered inert.

As vaccines are rolled out, and employers execute plans to return to ‘new social norms,’ we present XR Ulysses, which consists of two ongoing research strands developed in response to stymied live theatre during the pandemic: 1) MR Ulysses (Citation2020), an immersive prototype experience that uses live-action volumetric video (VV) technology and presents the footage in 3D in virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) (see ), and 2) VR Ulysses Live in AltSpaceVR (2021), an experimental live social VR performance in which remotely networked actors embody stylised, animated avatars and convene in a centralised simulated space (see ). XR Ulysses is an umbrella term for the two projects. Harnessing these technologies for performance practice, we present innovative approaches to site-specific digital storytelling that seek to engage audiences through the combined use of open-source tools, site-specific 3D data, volumetric video techniques, social VR, and a free-to-use game engine.

2. Case study: Bloomsday and XR ulysses

Bloomsday, one of the most important Irish annual literature festivals, is a cultural event that is deeply dependent on live performance. Taking place annually on June 16th, it involves site-specific re-enactments of scenes from James Joyce's literary masterpiece, Ulysses (Citation1922). The festival usually attracts thousands of literature tourists, scholars, and artists to the country's capital city to perform at multiple locations in and around Dublin. It involves singular performances at specific locations or promenade performances that move between several locations. In the latter case, performers employ various performative methods for engaging audiences and transferring them from site to site. This approach includes performance materials such as printed instructions, maps, pamphlets, human ushers, instructions articulated by actors, or prompts communicated via digital telecommunications devices, such as mobile phones, tablets, and, more recently, extended reality (XR) head-mounted displays (HMDs). However, such productions often pack many participants into relatively small rooms or cultural heritage sites. In 2020, in the interests of public health and welfare, such shows and associated sites were shut down – Bloomsday was cancelled. This sociological turn determined that Bloomsday celebrants innovate by engaging with digital media to sustain and continue to breathe life into the intangible cultural heritage tradition of performatively enacting, interpreting and responding to Ulysses annually on June 16th.Footnote1 Reflecting on the significance of a live (c.30-hour) Zoom-reading organised by the Sweny centre (a Bloomsday institution), Nastaise Leddy (company secretary) described it as ‘a lifeline for many "slightly eccentric" Joyce enthusiasts … "a place for lonely hearts; anyone you meet here is a friend for life. The Zoom event means we can connect with people who are completely on their own’’' (Pollak Citation2020). Bloomsday's particular case represents a profound new emphasis on the general need for theatre and performance practitioners to engage audiences through online (networked) formats. While video-conferencing helped ease the loneliness and permitted limited rehearsals, it was not by any means an adequate substitute for embodied interaction; the disconnect created by the rectangular framing of the subject, the lack of eye contact, and the frontal stereo sound make it very difficult for interlocutors to forego the remote connection and imagine that they are interacting in the same space. However, XR technologies have largely overcome these factors, and this article aims to show the potential this opens for the performing arts.

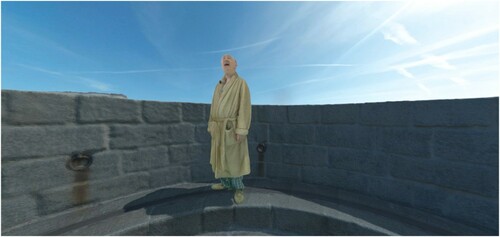

Our project combines photogrammetric, scenographic 3D data with volumetric video (VV) data to generate a site-specific immersive and performative virtual experience. Both VR performances reimagine the opening scene of Ulysses, which takes place on the roof-top of the James Joyce Martello Tower in Sandycove (Dublin). Paul O’Hanrahan (the actor) typically performed the piece on location during the annual Bloomsday celebrations, as well as on other cultural heritage occasions throughout the year. Due to the technical complexity of VV, the first iteration (MR Ulysses) consists of a three 3-minute monologue with some short (audio) voice-over interjections.Footnote2 The second iteration (VR Ulysses Live) is a lot longer and involves an entire dialogue between the two characters, Buck Mulligan and Stephen Dedalus.Footnote3 Both pieces are experimental pilot studies and explore the role of volumetric video, photogrammetry technologies and social VR in simulating site-specific performative representations of the text. Based on the premise that immersive virtual environments (IVEs) can create and sustain an illusion of reality where users can feel like they are ‘present’ within a virtual experience (Slater and Wilbur Citation2016), we hypothesise that these technologies can be applied to simulate audience experiences of site-specific performances remotely. This form of content creation might be called quasi-site-specific creative practice. Furthermore, at the crux of this research is the will to improve remote rehearsal processes, a theme evident in the months of rehearsals that initially took place on Zoom and then transitioned to AltSpaceVR, as we worked through the nuances of interpreting Joyce's novel for interactive digital media.

2. Background

2.1. Site-specific performance

Site-specific performances constitute a genre of theatre that breaks out of the dominant, traditional proscenium format of audience spectatorship by conceiving arrangements conceptually linked to specific geospatial locations. In the context of contemporary performance, the genre can be traced back to highly influential theatre figures like Agusto Boal, who developed the concept of ‘Invisible Theatre’ under his broader remit of Theatre of the Oppressed (Boal Citation1979), and Richard Schechner, who expounded his theory of ‘Environmental Theatre’ (Schechner Citation1968; Citation1973) as ‘six axioms’ to define ‘a new aesthetics of ‘interaction and transformation’ by reconfiguring theatre space and audience relationships and contradicting theatrical tradition’ (O’Dwyer Citation2021, 150). This renewed emphasis on spatial concerns was mirrored on the theoretical side by Marvin Carlson in his Places of Performance (1989) and by Una Chaudhuri, who called for a ‘geography of theatre’ in Staging Place: The Geography of Modern Drama (Chaudhuri Citation1997), an original, powerful and influential reimagining of the continuities of theatre history. Following these, there was a steady increase in practical and theoretical explorations of spatial matters in performance, including (but not limited to) Gay McAuley's Space in Performance (Citation1999), Nick Kaye’s Site-Specific Art (Citation2000), Mike Pearson and Michael Shanks’ Theatre/Archaeology (Citation2001), David Wiles’ A Short History of Western Performance Space (Citation2003), and Joanne Tompkins's Unsettling Space (Citation2006). Although all texts question spatial subjects of theatre, the focus of these studies varies across the performance spectrum of topics from theatre history to contemporary art to theatre and performance.

Following the mass intersection of digital mobile and ubiquitous technologies with site-specific processes in the early naughties, the genre has experienced a burgeoning of innovation. The technologies caused a disruption of the genre that manifested (practically) in the creations of makers like Blast Theory, Rimini Protokoll and Gob Squad, amongst others, and (theoretically) in the work of Benford and Giannachi (Citation2011), Christopher Baugh (Citation2005; Citation2017), Fiona Wilkie (Citation2012) and Sermon and Gould (Citation2013), amongst others.

Among the various definitions of site-specific performances is Pearson's clear and pithy statement maintaining they are ‘conceived for, mounted within and conditioned by the particulars of the location and its social situations (Pearson and Shanks Citation2001, 23). Pearson's thesis focuses on original artworks purposefully conceived (from scratch) for the site in question, whereas the works we present here are reinterpretations or re-enactments of an existing story: Joyce's Ulysses. As such, XR Ulysses is arguably more appropriately described as an innovative reactivation or transmission of (intangible) cultural heritage because it involved the study, treatment, representation, preservation and transmission of performative, ‘immaterial elements that are considered by a given community as essential components of its intrinsic identity’ (Lenzerini Citation2011, 102). However, Ulysses is not a fixed dramatic text; the book is deeply expressionistic; therefore, all performances of Joyce's text are interpretative and subjective as they are unique and original. Notwithstanding this taxonomic impasse, we can with the utmost certainty say that Joyce set the scene in the Martello tower in Sandycove, and the action is inseparably linked to the site. Our reinterpretation of it and its staging in a simulated virtual environment attempts to ‘articulate and define itself through properties, qualities or meanings produced in specific relationships between [the] ‘object’ or ‘event’ and [the] position it occupies’ (Kaye Citation2000, 1). As such, the focus of XR Ulysses was to explore various possibilities of simulating site-specific theatre in XR, over and above creating an original piece of theatre for XR; it was believed that Joyce's text allowed sufficient potential for creativity while also providing a concrete script to anchor the technological indeterminacy.

2.2. Digital Bloomsday projects

Chris Salter provides the valuable term ‘situated action’ to describe live events and performances that involve ‘physical, real-time situatedness involving collective, copresent spectating, witnessing and/or participation within the framework of a spatiotemporal event’ (Salter Citation2010, xxxiv). He posits this as a binary opposite to mediated performances. According to Salter's definition, we can say that in 2020/21, the global cultural phenomenon of ‘situated action’ collapsed. There were a few innovative attempts to stage live music/theatre events with situated action during the pandemic. For example, in the US, ‘The Flaming Lips’ held a live performance where each audience member and band members (including the drummer) were encased in inflatable plastic bubbles and, in the UK, international touring DJ, ‘Hot Since 82’, floated over the British landscape in a hot-air balloon.Footnote4

In terms of the Irish (Bloomsday) context, media institutions and independent artists alike responded to the lockdown in various ways. Ireland's national state-owned broadcaster, RTÉ Radio, re-broadcast a much-celebrated audio reading of the novel (‘Ulysses - Listen to the Epic RTÉ Dramatisation’ Citation2020). This performance featured many of Ireland's top-rated actors (of the time) and comprised a colossal c. 30 hours of continuous listening. Although innovative in its time, this does not represent a creative contribution to digital culture beyond being immediately and permanently accessible via digital archiving; it remains a monumental contribution to the performative remediations of the novel's cultural heritage. More innovative approaches to overcoming the Covid-imposed impediments to celebrating Bloomsday on-site were evident in the collection of independently produced Joycean work by artists, scholars, filmmakers and musicians. Most of these works can be reduced to either 1) pre-recorded filmic work posted or webcast on digital platforms facilitating user-generated content, or 2) live work performed online using the more recent and increasingly robust phenomenon of video conferencing technology that permits live dialogue between two or more remotely networked individuals. Noteworthy examples of pre-recorded user-generated-content circulated for Bloomsday Citation2020Footnote5 include, but are not limited to, the following projects:

The official Bloomsday Festival website quickly responded to the lockdown restrictions by establishing the first annual Bloomsday Film Festival (Citation2020), which included a collection of original and contemporary artistic responses to Joyce's novel by various emerging and established independent filmmakers.

The James Joyce Centre, which has its own Youtube channel, published a series of readings featuring home recordings by many of Ireland's contemporary acclaimed performing artists, including Aidan Gillen, Emmet Kirwin, Christine Dwyer Hickey, Camille O'Sullivan, and Glen Hansard, among others (The James Joyce Centre Dublin Citation2020).

The Museum of Literature Ireland (MoLI) organised a programme of artistic responses prepared for webcasting. Among these were Alan Gilsenan's Ulysses | Film (Gilsenan Citation2020), which ‘acts as a distillation of Ulysses, and may be viewed as a series of short films or as one long continuous piece’ (Gilsenan Citation2020).

The Office of the President of Ireland (Citation2020) hosted a virtual Bloomsday cultural performance at his residence (Áras an Uachtaráin) as part of a call to support Irish artists during the Covid-19 crisis (Citation2020).Footnote6

Noteworthy examples of the latter (live video-conferencing) format include:

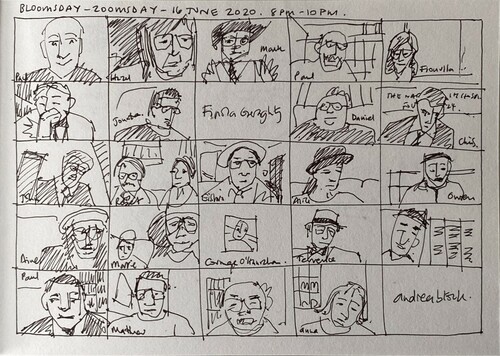

Humid Nightblue Fruit — a regular Bloomsday fixture organised by Paul O’Hanrahan (aka Balloonatics). The performance was moved to an online (Zoom) format to substitute the normal meeting at Wynn's Hotel (Dublin), where Joyce scholars and enthusiasts read excerpts of the text live. This format facilitated ‘a truly global gathering of readers and viewers’ from Portugal, Japan, Greece, Bulgaria, the UK, Mexico and the USA, and the Joyce Institute of Ireland members. This ‘Zoomsday’ event was artfully memorialised in illustrated format by Hazel Macmillan (see ).

PJ Murphy O’Brien, who runs the former Dublin chemist (Sweny's) renowned for its mention in the book and now a mainstay of the pilgrimage, organised ‘a 36-hour reading of Ulysses on Zoom and … had people from Buenos Aires, from Moscow, from Brazil, from all over the US taking part’ (Pollak Citation2020).

In 2021, one year on and still in lockdown, Bloomsday celebrants and institutions were more organised, producing a plethora of pre-recorded work. As well as re-broadcasting the full 30-hour reading, ‘RTE Drama On One’ broadcast The United States versus Ulysses, by Colin Murphy (Citation2021), a dramatisation telling the true story of the decade-long battle to publish Ulysses in America, culminating in the legendary Woolsey Judgement of 1933. The James Joyce Centre webcast the video, entitled ‘Readings and Songs’ (Brabazon Citation2021), which is an excellent compilation of many readings and performances by numerous well-known musicians, actors, and Joycean figures. This production was much more professional than the series of home videos disseminated during the first year of lockdown. Bloomsdayfestival.ie hosted their ‘Second Annual Bloomsday Film Festival,’ with a significantly expanded selection of Joyce-inspired films (Bloomsday Festival Citation2021). The expanded programme was a testament to the speed and versatility demonstrated by artists in turning to the video format as a creative outlet. Two projects worthy of a special mention are:

A reimagined version of The Fruit Smelling Shop by Scullion (one of Ireland's most influential bands), recorded as part of a new initiative commissioned by the James Joyce Centre Dublin and supported by Culture Ireland.Footnote7 This collaborative project features the words of Ulysses, set to music by Sonny Condell with strings performed by Crash Ensemble arranged by Gemma Doherty (Saint Sister), and a specially commissioned film by Myles O’Reilly (Scullion Citation2021).

Deirdre Mulrooney and Evanna Lynch's continued exploration and reclamation of ‘Lucia Joyce as an artist’ included a zoom reading of Michael Hastings’ outstanding 2004 play CalicoFootnote8 (Mulrooney and Lynch Citation2021).

All these artistic responses to (the lack of) Bloomsday have a significant common characteristic: the sense of ‘situated action’ – an experience of shared presence between audience and artist – is short-circuited by the televisual mode of engagement. Pre-recorded videos are every bit as alienating and disconnected from the audience as content piped over the cathode ray tube, even if the methods of dissemination have been democratised to some extent by internet video publishing platforms. By facilitating dialogue, live video conferencing software goes some way towards intensifying a shared sense of presence; however, the participants’ perception of sharing the same space is minimal.

In 2020, VR projects responding to the Bloomsday cancellation were rare. However, apart from our research, there were two other projects of particular note: 1) Eoghan KidneyFootnote9 and Shane T. Odlum convened a virtual gathering in a custom-built scene that simulated the Sandycove Tower using Mozilla's social VR platform and included iconography from the book and fragments of the text printed in ‘The Little Review’Footnote10 (Kidney Citation2020), and 2) The Boston College produced a VR game called Joycestick, which allowed users to explore immersive, spatial 3D VR reinterpretations of some scenes (Smith Citation2018). These works were far closer to our project because they tried to create an immersive story experience. However, each project adopts a different strategy for encouraging users to engage with Ulysses. The former invited users to embody a procedurally animated social VR avatar and to engage with other avatars in real-time in a social VR platform. Despite the low fidelity graphics, the sense of ‘situated action’ – that is, the sense of being in the same space as the performer and other audients – is palpable. However, there is still a long way to go before there are naturalistic visuals in social VR platforms; the Firefox platform had very low-fidelity character representations, curtailing the sense of site-specific interaction that is typical of Bloomsday. The latter (gamified) version is based on the first-person, spatial exploration format specific to gaming. There was no attempt to represent or simulate human or quasi-human interaction; it was purely a solipsistic exploration of sets, props and trivia and, therefore, not comparable to our project, which concentrates on the performative reinterpretation of the text by an experienced Joycean actor. All projects were successful in their unique approaches. The radical differences in the way they each engage storytelling in VR is a testament to, on one hand, the plethora of exciting possibilities opened up by the emergence of new technologies and, on the other, the lack of a consistent and robust storytelling grammar for creative artists attempting to express themselves through these new media. This observation is precisely the findings of a survey of subject matter experts, carried out in 2020: XR technologies demand a paradigm shift from storytelling to storyworlding, but ‘further research is required to explore the idiosyncrasies of immersive technology that will dictate how this paradigm shift will affect the practice and consumption of creative cultural performances’ (O’Dwyer et al. Citation2020).

2.3. Extended reality (XR)

XR is a recent term that encapsulates all real-and-virtual collaborative environments generated by digital technology. A popular subset of XR is mixed reality (MR), a continuum that ranges from the completely real to the completely virtual, encompassing all possible variations and compositions in between (Paul Milgram et al. Citation1995). The ‘X’ in XR represents a variable that can be replaced depending on the applied technology, such as augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR). XR technology is currently experiencing a resurgence of interest within multiple application spaces, with both AR and VR HMDs being more readily available than ever before (Evans Citation2019).

The medium of VR provides multimodal stimulation — visual, audio, and haptic — surrounding (or immersing) the user within an artificial world. Immersion is further enhanced via the individual control of the camera's ‘point of view’ with six degrees of freedom (6DoF) – forward/backward (surge), up/down (heave), left/right (sway), yaw (normal axis), pitch (transverse axis), and roll. This effect gives the interactor a sense of being present in the virtual or augmented world, where the physical body may not currently be located, a phenomenon known as telepresence. In VR, an avatar is often mapped — in real-time — to the user's movements within the virtual space, creating a further sense of embodiment within the digitally constructed character. These avatars can vary in fidelity and articulation but are often cartoonish in an unrealistic or semi-realistic style. More in keeping with the site-specificity of performance art is AR technology. AR also has a long history of applications; however, the term was first coined in 1992 (Caudell and Mizell Citation1992) to describe systems that overlay computer-generated materials onto real-world scenes. AR can superimpose spatially accurate computer-generated images over a user's point of view in the physical world. These digital displays provide a spatially-aware composite view of both worlds.

The rise of immersive fantasy worlds extends from literary prehistory (the late Victorian period) to the mid-twentieth century (Saler Citation2012). Since the early 1980s many projects have been described as ‘virtual reality art’ (Laurel Citation2013). A few notable examples provided users with immersive, shared telepresent experiences mediated from within multiple XR technologies, such as the Interior Body Series (Davies Citation1990-Citation1993) and EVE (Extended Virtual Environment) (Shaw Citation1993). In the twenty-first century, social VR can now offer many types of collective interactions in one place — where users are connected via social networks to others with compatible devices. These shared worlds can host live events, reaching larger audiences than possible in the real world. Performances such as The Under Presents (Tender Claws, 2019), Finding Pandora X (Benzing Citation2021), etc., apply social VR platforms and primarily consist of user-generated worlds. Participants within social VR applications gather together as avatars in environments that can be life-like or completely abstract. Users can choose their avatars and interact together as if they are present in the simulated environment.

3. Technical description

The technical pipeline for XR Ulysses involved several unique steps, mostly involving free-to-use and open-source software. The process can be broadly categorised into two main strands: the scene's static capture for VR and the human subject's dynamic capture for VV reconstruction.

3.1. Static capture (photogrammetry)

The scene creation process for XR Ulysses involved the digital reconstruction of a complete 3D scene to be populated by telepresent or virtual actors. This approach to digital scenography was achieved via an open-source, step-by-step process (Dawkins and Young Citation2020a) that imparts the knowledge to build shared digital worlds from the bottom up. The empowerment of artists and amateurs with the necessary skills to create places within virtual worlds encourages them to share this knowledge with others via social VR (Dawkins and Young Citation2020b).

1. Capture Media / Ground Truth: The first step involved ‘Ground Truthing,’ where a site-specific field trip or representative location was visited. This physical place was explored first-hand and captured ‘as-is’ by taking digital images and recording ambient sound. In this way, we demonstrated the ‘ground truth’ of representing a physical place for a performance.

2. Photogrammetry: The next step applied a process known as ‘photogrammetry,’ using free and open-source software called Meshroom by AliceVision. This software automatically analysed the captured digital images and reconstructed a spatially accurate and textured 3D model.

3. Clean Up: The previous process invariably created a lot of visual noise. Therefore, model cleaning and preparation were required. A free-to-use 3D editing software called Blender was used to reduce unnecessary detail and complexity in the model.

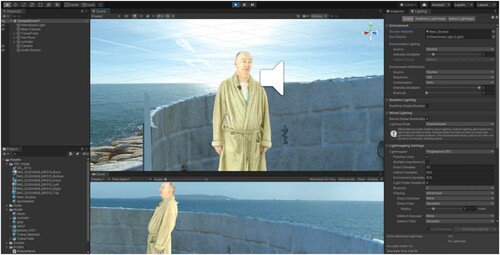

4. Scene Building: The next stage involved assembling the virtual environment in Unity, a game engine that is free to use for non-commercial projects. This step entailed creating a 3D scene, arranging 3D models, 360⁰ images, and adding spatial sound to the game engine (see ).

5. Social VR: This next step involved uploading the 3D scene to a social VR platform and inviting other project members to collectively populate the world to share their experiences and opinions of the set. Following this, the digital scenography was remodified and revisited accordingly. For Ulysses Live in AltspaceVR, the scene was uploaded to the platform ‘AltspaceVR’ to share with collaborators and remotely host embodied, telepresent rehearsals and the official performance (see ).

3.2. Dynamic capture (volumetric video)

Volumetric video (VV) is a logical progression of photogrammetry technology, in the same way that film was the logical progression of the photograph. A VV shoot captures a performance in three dimensions using an array of video cameras surrounding the subject and simultaneously capturing physical live-action gestures from multiple angles (O’Dwyer and Johnson Citation2019; O’Dwyer et al. Citation2018), see . The footage from all cameras is merged in postproduction processes that use a combination of advanced computer vision techniques, including ‘a novel, multi-source shape-from-silhouette (MS-SfS) approach’ and multi-view stereo (MVS) algorithms (Pagés et al. Citation2018). It is, subsequently, possible to reconstruct a 3D model for every video frame of the captured footage. Using a bespoke toolkit (Volograms Citation2021), the series of 3D models are loaded into the game engine software, and the player iterates through them at 30 frames per second, thus creating the illusion of live-action movement in three dimensions, see . The collection of 3D models represents a live-action dynamic, temporal object that can be displayed within various 3D extended-reality platforms. These platforms include mobile phones, tablets, VR HMDs (e.g. Oculus, HTC Vive, Valve Index), and AR glasses (e.g. Hololens, Magic Leap).

Figure 5. A collage of simultaneous stills (taken from all camera angles), from the VV capture of actor Paul O’Hanrahan.

The first production for XR Ulysses was a live-action representation of the opening scene of Ulysses, a performance that would typically have been performed on location at the Sandycove Martello Tower (in Dublin) during the annual Bloomsday celebrations. The original focus of our research was to support the festival and innovatively contribute to the preservation and celebration of intangible cultural heritage, that is, performative representations of Joycean literature. This goal was first conceptualised as a pilot episode for AR using our cutting-edge VV techniques to be premiered at the Joyce Tower on Bloomsday Citation2020. However, the incident of the Covid-19 lockdown demanded that we shift the focus of the work and prepare it firstly for the VR format to exhibit it remotely. The research, subsequently, took on a new primary objective — to explore and show the combined potentialities of VR and VV technologies to provide new ways for performance artists to reach audiences and, analogously, for audiences to engage with performance art and to experience (even if only an inkling) the much-missed sensation of situated action.

Our research endeavours resulted in a site-specific (photogrammetrically accurate) VR application in which a global audience could be immersively engaged. Additionally, the VV artefact can be later reappropriated for a physical on-location AR performance. What follows in the next section is a discussion of our project in terms of a formative exploration of the potential of this work to 1) support performing artists looking to create site-specific work and to engage audiences in novel ways, and 2) sustain access to performance culture during a time of global lockdown.

4. Discussion

XR technologies have excellent potential to support novel approaches to site-specific work and to sustain access to performance culture during times of lockdown because of the enhanced sense of physical presence they bring to remote interactions. In addition to existing mainstream audio-visual capabilities, they also harness gestural technologies that track hand and head movement. As explained in section 2.3, this affordance delivers a more natural sensation of movement within the digital environment, known as 6DoF. This inclusion of gestural expression and complete freedom of movement in 3-dimensions provides heightened feelings of presence, embodiment, and a better sense of inhabiting the same space as your interlocutor (Ryan Citation2015). In addition, they have integrated advanced user experience features such as synchronous voice chat, real-time movement, and the agency to custom design avatars, all of which make this an increasingly appealing platform for networked social gatherings. Compared to conventional video conferencing technologies, XR facilitates a more realistic sense of a social community, strengthening social cohesion.

Concerning our explorations of rehearsing and performing the Ulysses dialogue via social VR, we, as a performance collective, experienced an intimate sense of sharing the same space. The first couple of rehearsals were conducted over Zoom, limiting us to rudimentary dialogue readings. Then, once the scene was built and the equipment was distributed to the crew, we migrated to the ASVR platform. When this was up-and-running, we had a far more visceral sense of being in the same space as each other. As one of the actors stated in a post-show discussion:

First, you see the cartoonish aspect of the actual visuals, and they seem to simplify the text in some ways. But the more you actually start to rehearse in it … the more it becomes like acting in the real play … it felt more and more real. There's kind of a curious doubleness about it: the figures themselves seem quite simple, but, actually, when you are engaged with it, the actual drama comes out. (O’Hanrahan, Paul (actor/director), in post-performance Q&A seesion. June 16th 2021)

It's very, very different. You are missing many of your appendages. Like you are missing all of these parts (elbows, knees, etc.) and all of the bits that connect. So it's a whole different level of focus. And because it's disconnected, you don't really know exactly what the audience is seeing. Whereas when you have your whole body, you have a better idea of what's going on. It's just a matter of technology and how it will advance; I can only assume we’ll have our whole bodies in there and all the haptics, so it’ll be like being in our own skin. But yeah, it was really interesting. (Brady, Cameron (actor), in post-performance Q&A session. June 16th 2021)

Another widely agreed upon potential is the much wider national and international reach for global audiences taking part in virtual Bloomsday. This potential is, of course, also attainable through video-conferencing technologies (thoroughly documented in Section 2.1). However, despite the potential global reach of VR, there remain other obstacles around access, that is, access to the technologies – unless you have a VR headset, you cannot experience the performance in 6DoF. The democratisation of access is a challenge that will take a long time to overcome because XR technologies are expensive, and comparatively few people possess them. Furthermore, site-specific art and performance is a genre that is often framed as being highly accessible for communities and demographics that do not normally engage with art and theatre. Their social goal is to engage individuals in refreshing ways that aid the bonding of neighbourhoods or provide a geographic ‘point of convergence in which … expressions of community are articulated’ (Rugg Citation2010, 53). Therefore, any project aiming to subscribe to this aesthetic and conceptual basis also needs to adhere to its ethical conditions, and access remains a significant economic and technical challenge for XR projects.

O’Hanrahan also noted the generational gap between himself and the rest of the team, insisting that this was an excellent opportunity to work creatively with people from different generations, and this would be one of the exciting applications of AltspaceVR, Zoom and mixed reality technologies used in a creative context in the future (O’Hanrahan, Paul. Interview with actor/director, June 21st 2021).

Figure 6. Screenshot the VV asset playing in the Unity Game Engine with the photogrammetric set and a 360 image skybox (taken at the correct location).

Finally, with specific relevance to the central argument of this paper, there was unanimous concurrence on the potentiality for VR to ease the collaborative–creative blockages imposed by epi-human factors, like pandemics, and the associated anxieties caused by isolation, loneliness and so on. In general, the team agreed that there was something exciting and almost childlike and innocent about using these technologies. Apart from their cartoonish aesthetic, they are also new and innovative, demanding exploration and inventiveness. These qualities made them interesting for the team, providing them with relief from the monotony of lockdown. XR technologies are inherently playful and ludic; the platforms provide us with ways of playing with each other, and play is, of course, central to drama and performance. Furthermore, ‘the seed of Ulysses, at the heart of Joyce's book, it is full of different styles of writing and different locations and those styles of writing and their variation show Joyce at play’ (O’Hanrahan, Paul. Interview with actor/director, June 21st 2021). In the same way that Joyce has played with words, it is fitting that XR Ulysses is the manifestation of playing with different media and technologies as we explore their convergence with creative literature and attempt to consolidate a new grammar of XR performance.Footnote11

Conclusion

This paper reviews the impact of the Covid-19 lockdown measures on creative expression by charting a cross-section of innovative artistic responses to the stifled celebrations of James Joyce's Ulysses (customarily held at site-specific locations) on the annual literary festival of Bloomsday. It introduces and describes a project developed by a collective of XR researchers and performing artists. XR technology can facilitate the creation of alternative, mixed realities and is defined by its ability to convey a sense of presence that promotes immersion in an activity. Unlike 2D linear media, such as traditional text or film, engagements via XR encourage exploration and discovery through immersion and presence. Unique performances can be shared and discussed through activities organised around virtual site-specific experiences via social VR and storytelling. Virtual site-specific performance can play an essential role in supporting and enhancing rehearsals and empowering creative performance artists stymied under the Covid-19 lockdown measures. We do not purport that XR is a panacea but, with its recent re-emergence and growing popularity, it is possible to deliver site-specific experiences to larger audiences without the need to travel physically. There is still some way to go in terms of the fidelity of audio-visuals for place-based simulations of face-to-face encounters. However, XR is beginning to trouble definitions of ‘situated action’ by establishing quasi-spatial locations and performance situations where the actors and audience can experience a sense of co-presence (of occupying the same space), a cherished condition of live performance. However, the technology needs to evolve further, and more research is necessary to define consistent XR performance strategies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Néill O’Dwyer

Néill O’Dwyer is a Research Fellow and the Principal Investigator ‘Performative Investigations into Extended and Augmented Reality Technologies’ (PIX-ART), in the School of Creative Arts (SCA) at Trinity College Dublin (TCD). He previously worked in V-SENSE project (Dept. of Computer Science) where he continues to be an associate researcher. He teaches Performance and Technology in the SCA. He is an awardee of the prestigious Irish Research Council (IRC) Government of Ireland Research Fellowship (2017 – 2019). He is the sole author of Digital Scenography: 30 years of experimentation and innovation in performance and interactive media (forthcoming in 2021) and a co-editor of The Performing Subject in the Space of Technology: Through the Virtual, Towards the Real (2015) and Aesthetics, Digital Studies and Bernard Stiegler (2021). He worked with Bernard Stiegler at the Institute of Research and Innovation (IRI), at the Pompidou Centre, Paris. Néill specialises in practice-based research in the field of scenography and design-led performance with a specific focus on digital media, computer vision, human–computer interaction, prosthesis, synergy, agency, performativity and the impact of technology on artistic processes.

Gareth W. Young

Gareth Young, as a postdoctoral research fellow on the V-SENSE project, Gareth's research focuses on evaluating creative uses of extended-reality (XR) technology by applying quantitative and qualitative human-computer interaction (HCI) evaluation techniques. This approach includes studying the design and use of XR technology in creative practices, focusing on the interface between users and the XR platform. His role is to observe and record how users interact with XR and design new methods to interact with XR in innovative and novel ways. Topics of exploration focus on using XR and volumetric video (VV) in cultural heritage, such as film, theatre, and performance practice, from the perspectives of both practitioners and the audience. The role of immersive content creation in mediated perspective-taking experiences of creative storytelling content is also investigated, including the use of XR as an 'empathy making machine' by facilitating perspective-taking and allowing users to experience another person's circumstances. Other duties include investigating the role of XR in the delivery of educational content in the context of higher education, research, and artistic practice and the influences of immersion and presence on students' overall experiences.

Aljosa Smolic

Prof. Aljosa Smolic is the SFI Research Professor of Creative Technologies at Trinity College Dublin (TCD) and lecturer in AR/VR in the Immersive Realities Research Lab of Hochschule Luzern (HSLU). Before joining TCD, Prof. Smolic was with Disney Research Zurich as Senior Research Scientist and Head of the Advanced Video Technology group, and with the Fraunhofer Heinrich-Hertz-Institut (HHI), Berlin, also heading a research group as Scientific Project Manager. At Disney Research he led over 50 R&D projects in the area of visual computing that have resulted in numerous publications and patents, as well as technology transfers to a range of Disney business units. Prof. Smolic served as Associate Editor of the IEEE Transactions on Image Processing and the Signal Processing: Image Communication journal. He was Guest Editor for the Proceedings of the IEEE, IEEE Transactions on CSVT, IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, and other scientific journals. His research group at TCD, V- SENSE, is on visual computing, combining computer vision, computer graphics and media technology, to extend the dimensions of visual sensation. This includes immersive technologies such as AR, VR, volumetric video, 360/omni-directional video, light-fields, and VFX/animation, with a special focus on deep learning in visual computing. Prof. Smolic is also co-founder of the start-up company Volograms, which commercializes volumetric video content creation. He received the IEEE ICME Star Innovator Award 2020 for his contributions to volumetric video content creation and TCD's Campus Company Founders Award 2020.

Notes

1 While Ulysses is a tangible product of Anglo-Irish literature, Bloomsday, as an annual festival composed of performative, temporal and ‘immaterial manifestations’ (Lenzerini Citation2011) of the book, is quintessentially representative of the intangible cultural heritage genre.

2 Project description (Youtube): https://youtu.be/km5SSDLBPlo

4 Alex Taylor gives a good sample-list for live music innovations during the lockdown here: https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-55947209

5 We respectfully acknowledge the plethora of quality international projects that commemorate Ulysses on Bloomsday since its inauguration, through 2020 and beyond; however, this article focuses on Dublin-based performers and institutions that would normally stage site-specific performances in the Dublin Area.

6 While this cannot be specifically referred to as an independent production (given the top-down state funding), it is certainly a testament to a president's enthusiasm for the arts and heritage.

7 Culture Ireland is a national funding agency set up to support the dissemination and touring of Irish culture abroad. It is interesting that even the funding agency has to flex its qualification criteria for eligible art projects during this period; as there was no touring of live work abroad at the time, distribution of video became a valid format for the dissemination of Irish culture.

8 Commissioned by the Royal Shakespeare Company; originally directed by Edward Hall and starring Romola Garai as Lucia.

9 Kidney also (separately) produced an exploratory VR experience of Ulysses in 2014 in which hyper-linking and the spatial nature of VR was used as a way of focusing concentration and annotating experiences of literature.

10 ‘The Little Review’ was a transatlantic American literary magazine, founded by Margaret Anderson, that supported modern art and literature and operated from 1914 to 1929. It serialised Ulysses from 1918 until 1921. This, among other content, contributed to the editors going to trial for publishing obscene material. They lost their case, had to pay hefty fines and were ordered to tone down their content.

11 The need for develoing a new grammar of XR performance is a finding that emerged from the aforementioned series of subject matter expert interviews (O’Dwyer et al. Citation2020), and is the focus of a newly funded project (PIX-ART) lead by Néill O’Dwyer and guided by V-SENSE and the Dept. of Drama at Trinity College Dublin.

Bibliography

- Ahrens, K. F., R. J. Neumann, B. Kollmann, J. Brokelmann, N. M. von Werthern, A. Malyshau, D. Weichert, et al. 2021. “Impact of Covid-19 Lockdown on Mental Health in Germany: Longitudinal Observation of Different Mental Health Trajectories and Protective Factors.” Translational Psychiatry 11 (1): 392.

- Baugh, Christopher. 2005. Theatre, Performance and Technology: The Development of Scenography in the Twentieth Century. Theatre and Performance Practices. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Baugh, Christopher. 2017. “”Devices of Wonder”: Globalizing Technologies in the Process of Scenography.” In Scenography Expanded: An Introduction to Contemporary Performance Design, edited by Joslin McKinney, and Scott Palmer, 23–38. London; New York, NY: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

- Benford, Steve, and Gabriella Giannachi. 2011. Performing Mixed Reality. Cambridge: Mass: The MIT Press.

- Benzing, Kiira. 2021. Finding Pandora X. Social VR, Drama. Double Eye Productions.

- Bloomsday Festival. 2020. ‘Bloomsday Film Festival 2020’. Bloomsday Festival. 2020. http://www.bloomsdayfestival.ie/fringe-programme-2020/2020/6/11/bloomsday-film-festival.

- Bloomsday Festival. 2021. ‘BFF Official Selection 2021’. Bloomsday Festival. 2021. http://www.bloomsdayfestival.ie/new-page-2.

- Boal, Augusto. 1979. Theatre of the Oppressed. London: Pluto.

- Brabazon, Luke. 2021. The James Joyce Centre Dublin: Readings and Songs. Mpeg. Dublin: Fatale Events. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0LW635SlpdA.

- Brambilla Hall, Stefan. 2020. ‘This Is How COVID-19 Is Affecting the Music Industry’. World Economic Forum, 27 May 2020. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/this-is-how-covid-19-is-affecting-the-music-industry/.

- Brown, August. ‘Concert Industry Could Lose $9 Billion This Year Due to the Coronavirus Pandemic’. Los Angeles Times. 6 April 2020, sec. Music. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/music/story/2020-04-06/concert-industry-lose-9-billion-coronavirus.

- Caudell, T. P., and D. W. Mizell. 1992. “Augmented Reality: An Application of Heads-up Display Technology to Manual Manufacturing Processes.” Proceedings of the twenty-fifth hawaii International Conference on system sciences.

- Chaudhuri, Una. 1997. Staging Place the Geography of Modern Drama. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- ‘Covid-19 Pandemic Unemployment Payment’. 2020. Governmental. Government of Ireland. June 2020. https://www.gov.ie/en/service/be74d3-Covid-19-pandemic-unemployment-payment/#.

- Davies, Charlotte. 1990–1993. Interior Body Series.

- Dawkins, Oliver, and Gareth W. Young. 2020a. “Ground Truthing and Virtual Field Trips [Workshop].” At the immersive Learning network conference, iLRN Virtual Campus, VirBELA.

- Dawkins, Oliver, and Gareth W. Young. 2020b. “Engaging Place with Mixed Realities: Sharing Multisensory Experiences of Place Through Community-Generated Digital Content and Multimodal Interaction.” In Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality. Industrial and Everyday Life Applications, edited by Jessie Y. C. Chen, and Gino Fragomeni, 199–218. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Evans, Leighton. 2019. The Re-Emergence of Virtual Reality. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=1920352.

- Falvey, Deirdre. 2020. ‘The “Arts Recession” Will Be Five Times Worse than the Rest of the Economy’. The Irish Times. Accessed July 13th 2021. https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/the-arts-recession-will-be-five-times-worse-than-the-rest-of-the-economy-1.4376857.

- Fiorillo, A. and Frangou, S. 2020. “European Psychiatry 2020: Moving Forward.” European Psychiatry 63: 1.

- Gaffney, Sharon. 2020. ‘Covid Deals “fatal Blow” to Arts with €10 m Revenue Loss’. News. RTE (National Public Broadcaster). June 7th 2020. https://www.rte.ie/news/coronavirus/2020/0607/1145986-arts-ireland-Covid/.

- Gilsenan, Alan. 2020. ‘Ulysses | Film’. Museum of Literature Ireland (MoLI). June 16th 2020. https://moli.ie/digital/ulysses-film/.

- Hale, T., Angrist, N., Goldszmidt, R., Kira, B., Petherick, A., Phillips, T., Webster, S., Cameron-Blake, E., Hallas, L., Majumdar, S. and Tatlow, H. 2021. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nature Human Behaviour. – Last Updated 11 July 2021, OurWorldinData.org/coronavirus.

- Joyce, James. 1922. Ulysses. Paris: Shakespeare and Company.

- Kaye, Nick. 2000. Site-Specific Art: Performance, Place and Documentation. London: Routledge.

- Kelly, B. D. 2020. “Impact of Covid-19 on Mental Health in Ireland: Evidence to Date.” Irish Medical Journal 113 (10): 6.

- Kidney, Eoghan. 2020. ‘Bloomsday VR’. Virtual reality browser. Hubs by Mozilla. 2020. https://hubs.mozilla.com/m2mTHpM/bloomsday-vr.

- Laurel, Brenda. 2013. Computers as Theatre. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Addison-Wesley.

- Lenzerini, Federico. 2011. “Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Living Culture of Peoples.” European Journal of International Law 22 (1): 101–120.

- Masso, Giverny. 2021. ‘Mental Health Warning as Theatre Workers Dip to “Lowest Place Psychologically”‘. Profesional Theatre News. The Stage. February 2021. https://www.thestage.co.uk/news/mental-health-warning-as-theatre-workers-dip-to-lowest-place-psychologically.

- McAuley, Gay. 1999. Space in Performance: Making Meaning in the Theatre. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Milgram, Paul, Haruo Takemura, Akira Utsumi, and Fumio Kishino. 1995. Augmented Reality: A Class of Displays on the Reality-Virtuality Continuum’. In . Vol. 2351.

- Mulrooney, Deirdre, and Evanna Lynch. 2021. ‘CALICO by Michael Hastings (WATCH ONLINE)’. Bloomsday Festival. 2021. http://www.bloomsdayfestival.ie/fringe-programme-2020/2021/6/11/calico-by-michael-hastings-online-reading.

- Murphy, Colin. 2021. ‘The United States versus Ulysses’. National Radio Broadcaster. RTE Radio. June 13th 2021. https://www.rte.ie/radio/dramaonone/1227863-the-united-states-versus-ulysses-by-colin-murphy.

- O’Dwyer, Néill. 2021. Digital Scenography: 30 Years of Experimentation and Innovation in Performance and Interactive Media. 1st ed. Design & Production. London; New York: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama. https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/digital-scenography-9781350107335/.

- O’Dwyer, Néill, and Nicholas Johnson. 2019. “Exploring Volumetric Video and Narrative Through Samuel Beckett’sPlay.” International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media 115 (1): 53–69.

- O’Dwyer, Néill, Nicholas Johnson, Rafael Pagés, Jan Ondřej, Konstantinos Amplianitis, Enda Bates, David Monaghan, and Aljoša Smolić. 2018. “Beckett in VR: Exploring Narrative Using Free Viewpoint Video.” In ACM SIGGRAPH 2018 Posters on - SIGGRAPH ‘18, 1–2. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: ACM Press. doi:10.1145/3230744.3230774.

- O’Dwyer, Néill, Gareth W. Young, Nicholas Johnson, Emin Zerman, and Aljosa Smolic. 2020. “Mixed Reality and Volumetric Video in Cultural Heritage: Expert Opinions on Augmented and Virtual Reality.” In Culture and Computing, 195–214. Cham: Springer.

- Office of the President of Ireland. 2020. ‘Diary President And Sabina Celebrate Bloomsday 2020’. President of Ireland. May 16th 2020. https://president.ie/index.php/en/diary/details/president-and-sabina-celebrate-bloomsday-2020/video.

- Pagés, R., K. Amplianitis, D. Monaghan, J. Ondřej, and A. Smolić. 2018. “Affordable Content Creation for Free-Viewpoint Video and VR/AR Applications.” Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation 53: 192–201.

- Pearson, Mike, and Michael Shanks. 2001. Theatre/Archaeology: Disciplinary Dialogues. London; New York: Routledge.

- Pollak, Sorcha. 2020. ‘Bloomsday 2020 Goes Virtual as Joyceans Adapt to Covid-19’. The Irish Times, June 16th 2020. https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/bloomsday-2020-goes-virtual-as-joyceans-adapt-to-Covid-19-1.4280789.

- Rugg, Judith. 2010. Exploring Site-Specific Art: Issues of Space and Internationalism. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Ryan, M. L. 2015. Narrative as Virtual Reality 2. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Saler, Michael T. 2012. As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Pre-History of Virtual Reality. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press.

- Salter, Chris. 2010. Entangled: Technology and the Transformation of Performance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Schechner, Richard. 1968. “6 Axioms for Environmental Theatre.” The Drama Review: TDR 12 (3): 41.

- Schechner, Richard. 1973. Environmental Theatre. 1st edition. New York: Hawthorn.

- Scullion. 2021. Scullion | The Fruit Smelling Shop | In Celebration of Bloomsday. Music Video. Dublin: The Clinic Recording Studios. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HoiCGu-wMus.

- Sermon, Paul, and Charlotte Gould. 2013. “Site-Specific Performance, Narrative, and Social Presence in Multi-User Virtual Environments and the Urban Landscape.” In Digital Media and Technologies for Virtual Artistic Spaces, edited by Dew Harrison, 46–58. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Shaw, Jeffrey. 1993. EVE (Extended Virtual Environment).

- Singh, Shweta, Deblina Roy, Krittika Sinha, Sheeba Parveen, Ginni Sharma, and Gunjan Joshi. 2020. “Impact of Covid-19 and Lockdown on Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: A Narrative Review with Recommendations.” Psychiatry Research 293 (November): 113429.

- Slater, M., and M. V. Sanchez-Vives. 2016. “Enhancing Our Lives with Immersive Virtual Reality.” Frontiers in Robotics and AI 3: 74.

- Smith, Sean. 2018. ‘Joycestick: The Gamification of “Ulysses”‘. Boston College. 2018. https://www.bc.edu/bc-web/bcnews/humanities/literature/joycestick-ulysses-nugent.html.

- Stubbe, Janine H., Annemiek Tiemens, Stephanie C. Keizer-Hulsebosch, Suze Steemers, Diana van Winden, Maurice Buiten, Angelo Richardson, and Rogier M. van Rijn. 2021. “Prevalence of Mental Health Complaints Among Performing Arts Students Is Associated With Covid-19 Preventive Measures.” Frontiers in Psychology 12 (June): 676587.

- The James Joyce Centre Dublin. 2020. "Readings - YouTube". YouTube Channel. Ulysses Readings (blog). https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLud7Y6jSDvyxw9mesOQC7_oKOBzQv9AMW.

- Tompkins, Joanne. 2006. Unsettling Space: Contestations in Contemporary Australian Theatre. Basingstoke; New York: Palgrave Macmillan. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10487685.

- ‘Ulysses - Listen to the Epic RTÉ Dramatisation’. 2020. RTE Drama On One. Dublin, Ireland: RTE. https://www.rte.ie/culture/2020/0610/1146705-listen-ulysses-james-joyce-podcast/.

- Volograms. 2021. ‘Volograms Toolkit — Bitbucket’. Code Repository. Bitbucket.Org. May 19th 2021. https://bitbucket.org/volograms/vologramstoolkit/src/master/.

- Wiles, David. 2003. A Short History of Western Performance Space. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wilkie, Fiona. 2012. ‘Site-Specific Performance and the Mobility Turn’. Contemporary Theatre Review 22 (2): 203–212.