ABSTRACT

Using the centennial anniversary of TS Eliot’s The Waste Land as an opportune moment to reconsider the reflexive and the discursive in addressing themes occupying critical and creative thought, this document discusses the collaboration between a social scientist and a playwright during and in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Its main output, a play titled Wasteland, had an understory framed by the problem-event of the lockdown as it confronted not only the negativity of wasteland but also the possibility of negating it simultaneously. The play situates itself in the privileged UCL Student Centre to probe its ‘storied matter’ through repeated re-enactments. As an encounter between words and worlds across a temporal threshold marked by ‘becoming-events’, the play draws the building into focus, diffracting it, blurring it, and finally opening it up as a wasteland. Based on the Ancient Greek theatrical tradition of City Dionysia, it relies on ‘preplays’, multiple ‘draft’ readings, to emphasise less a staged performance and more an identity text that is unhurried, unfinished, improvised and provisional. For, in the inter-subjective exchanges within this text we find ‘the sense of ongoingness’ (Berlant 2008) to inhabit the now of our (post)pandemic present.

What does a city theatre of the future really look like? Who works in it, how do you rehearse in it, how is it produced and toured? How can the desire for free modes of production, for collective and contemporary authorship, for an ensemble theatre that not only discusses a globalized world but also reflects it and influences it, be brought into a set of rules? How do you force an institution that has grown old to free itself and become again the boards that ‘mean the world’?. Rau Citation2021, 21–22

We write to conjure a poetics of scenes at once social, dreamy, mattering, and incidental. Our collaborative project is about feeling and testing out the moments we move around in and the speculations we bring to them, generating scenes of life that are ideas of life. We try out practices of looser and sharper processing what we’ve seen, smelled, overheard, conjured. To move and conceptualize from within worlds is preferable to drawing a plane above them. Toggling across what’s starting up or falling away in a present closely noted creates a fractal, fractious narrative, if there’s a narrative at all. It might produce a story sense that stretches the social and political into a resource for living. Berlant and Stewart Citation2022, 1 (emphasis added)

In this sense, Eliot’s Waste Land resonates closely with the way the term is invoked outside of its literary field, especially in the critical realm of social sciences, where wasteland stands in as a metonym for the persistent onslaught of capitalist restructuring. Despite an excess of meaning that is largely (and unfortunately) a catalogue of negatives, critical social science endeavours to engage wasteland as more than a rhetorical device, an analytical lens instead, to show how this ecological shorthand can expose the skewed nature of socio-political realities and imaginaries, both historical and contemporary.Footnote1 For instance, in identifying wasteland as one priority research area of UCL Urban Laboratory (our academic ‘home’), we go beyond its moral ascription, utilising its ideological potency, to query the disenfranchising vagaries of uneven urbanisation. As a thematic interjection, its association with a range of supposedly unviable human activities is deliberately turned around to chart a critical commentary on not only the land politics around its designation or its insidious reference to appropriate modes of social behaviour but to critique the broader trends of surplus accumulation and its accompanying dispossession.Footnote2

The challenge with such an undertaking however is a methodological bind requiring us to think critically through the language we employ for exegesis (Gidwani Citation1992). While there is no dearth of rigorous academic research and scholarship that have pursued studies of the wasteland in its multiple empirical hues, there is an elusive performative blueprint to its material ontology, an indeterminacy that derives from its constant ‘liveliness’ or a state of becoming that is not easily captured.Footnote3 It calls for a scrutiny into its disposition as more than just a landscape (physical or imagined) via a creative register that engages and probes wasteland’s liminality, similar to how Eliot handles his ecological awareness but perhaps not quite like his disorienting poetic techniques. Recognising the wasteland as an object-thing of creative becoming, the opportunity offered by the UCL Creative Fellowship for a social scientist and a playwright to work collaboratively led to an exercise in probing the ‘storied matter’ of wasteland (Iovino and Oppermann Citation2012), thinking of it not as inert but a ‘vibrant matter’ dense with stories (Bennett Citation2010). While a prominent outcome of the fellowship was a play written by the playwright, it cannot be read as a straightforward dramaturgy – it seeks to go beyond the agency of conventional theatre to produce an embodied performative narrative of ‘social and power relations, biological balances and imbalances, and the concrete shaping of spaces, territories, human, and nonhuman life’ (Iovino 2016 cited in Oppermann Citation2016, 89), not an easy endeavour either.

Against this contextualisation, this document unfolds at two levels. Firstly, it delves into the critical reflections and creative impulses of the two collaborators that coalesced through the play’s subject matter – a fictionalised narrative of a contemporary wasteland pixelated by complex socio-spatial–temporal relations, interactions that transformed the intertextual space of the script itself into a textured performance. What emerged was an authorial process drawing on a mode of uncertain dramaturgy that has become a prominent way of creatively responding to the speculative future of the Anthropocene. Secondly, it addresses the way this collaborative venture cast open challenges around literally situating the play not just in scene but in site as well, evolving from conventional staging aspirations to more experimental possibilities. For those familiar with avant-garde theatre, the medium-specificity of a play that is drawn to performing apparatuses outside of the stage might not be so novel (see for instance, Ferdman Citation2018) but it took on new dimensions that became particularly significant within the temporality of a (post)pandemic situation where we wanted to go beyond the obvious option of viral digital theatre (cf. Mosse Citation2022). Rethinking carefully the idea of ‘live’ performance, especially one that is a vital act of transferring social knowledge while also conveying its associated frictions, we viewed the pandemic as one that has indeed interrupted the status quo but, in a context, where this status quo needs to be unsettled, especially along the lines of decolonial, desire-based narrative-making (Capece and Scorese Citation2022).

Collaboration

… the great pleasure of any collaboration is multiplying idioms and infrastructures for further thought that neither of us could have generated alone. (Berlant and Edelman Citation2014, 111)

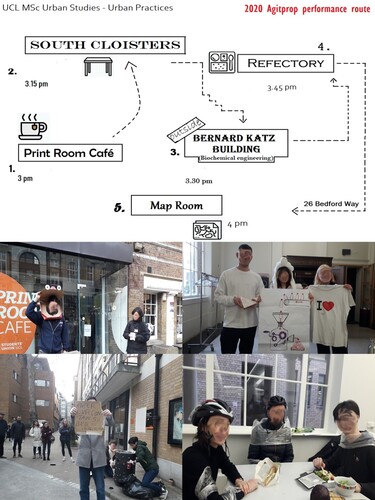

Our proposal titled City Dionysia: Narrating Wasteland in Urban Life invoked the ancient Greek practice of CITY DIONYSIA where plays fuelled public debate to explore how twenty-first century theatre can create new audiences for academic research while promoting creative inquiry into urban problems. Our attempt to ‘perform’ waste through the reference of theatre was set against a larger concern of visualising a prominent problem of contemporary urban life whose intersections with the global scale of the Anthropocene couldn’t be ignored. Initially, our proposal intended to encompass the notion of WASTELAND by producing a trilogy of performance-oriented interactive pieces drawing on plural practices within a dramaturgical frame. The first was a play (draft) tentatively titled WASTELAND which sought to bring together critical research methodology into playwriting by pushing the notion of the ‘performative’ towards one that is not reducible to those commonly designated qualities such as mimesis, intentionality or rehearsal. First and foremost, it was to be a strong piece of dramaturgy experimenting with the representational and narrative aspects of critical urban enquiry. In addition, agit-prop enactments were envisioned as a second output, fleshing out key sub-themes within the broader query of WASTELAND. This was more of a pedagogic exercise in line with what Klich (Citation2012) has referred to as posthuman pedagogies using theatre practices. Here, MSc Urban Studies students within a particular module (Urban Practices) drew on street theatre, combining it with the activist culture of rallies and demonstrations, to write a series of short texts which were play-read live across a loose ensemble of UCL sites. Based on the notion of free theatre that is flexible and portable, this exercise transformed campus locations into unorthodox performance spaces relying on a spontaneous participation of passers-by as players (). Original aspiration for developing these agit-props as interactive audio plays however had to be abandoned for a more simplified analogue style. As the ‘real’ urban environment responding to descriptions of waste became the scenography, we felt that there was little to be gained by a sophisticated form of immersive transaction here. In fact, our decision against a digitally contrived auditory experience was taken with the view of keeping the somatosensory modalities of engagement in this context simple. Relying on the absurd, the realism of singular (and simpler) meanings worked better rendering unnecessary the need for advanced technical effects.

Figure 1. Agit-prop performance by MSc Urban Studies students, February 2020; Performance route map prepared by students; photos by Nicola Baldwin.

This was partially the reason why we didn’t pursue the third component of the application to stage site-specific events using multimedia formats where ‘waste hotspots’ would be identified across the university campus, transforming into a series of ‘watchful’ spaces to textualise different aspects of waste. This was intended as a different kind of scopic approach to playwriting, using short scenes written in parts, not necessarily to be read together but nevertheless crucial to revealing the multiple meanings and experiences of waste. This was eventually dropped when our collaboration did not evolve into a collective endeavour as we had anticipated, compelled to remain more speculative. It would have required a complex process and dynamic of affecting and being affected, which we were unable to probe as the fellowship unfolded during the pandemic. Paradoxically, this mode of emphasising corporeal sensation, affect and embodiment was set aside precisely at a moment when it became critical to rethink the nature of performance during the pandemic. Instead, our focus was on the play whose narrative shifted away from predictive modes of writing, responding to an overlapping sense of the crisis in the present, involving both the Anthropocene and the pandemic.

Early on, we had envisioned our collaboration as a genuine exchange with a dialogic give-and-take (Berlant and Edelman Citation2014), aware that we might have different anxieties about wasteland as a site of hopes and expectations even if it is often experienced as otherwise. Half-way through the 2019–2020 academic year, months of lockdown and strictures of social isolation that followed the Covid-19 pandemic constrained the nature of our exchange and our efforts to be in relation to each other and our ideas. Collaboration now was as much as that which could be shared as left unshared while we were constantly absorbing new rules of social relations. Neither of us were able to play the other’s interlocuter. Instead, we were now trying our best to stay in sync, checking in when possible. Wasteland as a play still emerged, taking shape in this absence of live encounters, unfolding as a fictocritical story (Muecke Citation2002) amidst the temporal vagrancy of specific becoming-events (and not just the pandemic here). Building on tactics developed by the playwright in earlier work, WASTELAND was conceived as a ‘hyperfiction’ gathering the ordinary and extraordinary aspects of waste as a socio-political concern into a sensitive dramaturgical narrative without sensationalising it. An added challenge was to think of engaging and actively involving not only the audience in a theatrical work driven by zoom protocols, but also the expectations of productivity and efficiency in a translocal artistic collaboration that, as a performative process, extended to include the actors and audience. This had a clear bearing on the way WASTELAND’s scenography evolved. For, a non-delineated digital space can be experimentally interesting but also challenging in terms of acknowledging and addressing simultaneously the heightened sensory self of both the actors and the audience.

Wasteland’s scenography

Having eschewed the impulse to cast the wasteland literally as a barren site, desolate and unvalued, there is an ensemble of usual suspects within the vast expanse of UCL whose milieu in and of itself could easily have been construed as a wasteland. And yet, most of these were eliminated through an undeniable twist in an understory triggered by the problem-event of the lockdown giving an all-new spin to the wasteland as an ontological being. The play, in a pique, situates itself in a privileged site, the UCL Student Centre, to not only confront the negativity of the wasteland but also create the possibility of perhaps negating it simultaneously. In fact, once the play settles in, there is something intuitively persuasive about the Student Centre as it plays the missing minstrel in our deliberations about the wasteland.

Opened in February 2019, UCL Student Centre is a newly constructed building of nearly 6000sm, spread across 8 floors and serving as a large-scale social learning space to meet the needs of new pedagogical approaches. With 1000 learning spaces of varied types alongside a Prayer Room, a Meditation Room, ablution facilities, a student enquiries centre incorporating disability, mental health and wellbeing support providing 24-hour all year around access, the programmatic brief has been lauded as visionary (). With at least 11 awards to ratify it as an architectural marvel, the building is frequently referenced as a development model for new learning spaces such as those on the UCL East Campus. Soon after its inauguration, it was supposedly the most used building on campus, fulfilling its objectives of catering to a significant aspect of university growth, increasing student population and their rising demands. And yet, a year later, when the pandemic hit, the building closed in line with the state-enforced lockdown. Reopening few months later, it had to put in place reduced access to students with part of its civic space converted temporarily into a covid test site. Over the last year as the campus strives to return to a semblance of the ‘new normal’, the building’s estate team has worked hard to recover its purpose, that buzz of active usage.

Figure 2. Grand civic space: Central atrium of the UCL Student Centre. Image courtesy: Nicholas Hare Architects © Alan Williams photography and Richard Chivers Photography: Photographer owns copyright.

But in what possible way is this pristine architectural form expedient to bringing wasteland into focus, fictional or factual? It was too tempting to ignore this enchanted architectural space emptied suddenly of human presence serving as a superb foil for a social discourse on disillusionment that has become an almost normalised state of the (post)pandemic condition. But it was not the building’s dramatic spatiality but its temporality that was invoked to stage a rather preternatural encounter with this fraught ‘historical present’ (Berlant Citation2008).Footnote6 Its 24-hour operative logic is used to frame, akin to Eliot’s Waste Land, multiple temporalities in a spectral sense of the ever-present. Thus, using the building’s design philosophy to reveal hidden and inverted connotations, the play sought to link wasteland not just to the building’s physicality but also to establish a socio-spatial scenario that goes beyond this materialised wonder. The play unfolds over a period of 24 h beginning in the middle of the night as an encounter between words and worlds across a temporal threshold that draws the building and its many spaces into focus, diffracting it, blurring it, and finally opening it up as a wasteland.

Rosa, a contract cleaner from Mexico, sprints through a service entrance into the University’s new building, changing into her overall. It is 4.30am.

(THE PLAY): If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around, does it make a sound?

If a woman’s job is to clean a building when it is empty, and no one sees her, does she exist? Albert Einstein once asked Niels Bohr whether he believed the moon does not exist if nobody is looking at it. Bohr replied that, he would never be able to prove that it does. The moon and the woman are an infallible conjecture – their existence cannot be either proved or disproved.

And that fallen tree … ? Is taken to a factory to be manufactured into 3-ply quilted toilet tissue. One night, an exhausted employee mistakenly shunts 144 rolls of newly manufactured premium quilted paper into 2-ply economy tissue multipacks. As Rosa starts her shift, cleaning manager Mr Blunt, bulky in his hooded jacket, grabs a roll of this rogue toilet paper and hurries towards the basement. He does not notice a woman in an animal-print coat …

Lou picks up her phone. Spools through twitter. Instagram. Dawn sunshine flooding the glass atrium. Fresh faced young women, sun-tanned, determined, green. It looks so beautiful, so ideal. Hashtag #OurBuilding. Laughter, home-made cakes and signs.

Euggh, is that the blocked toilet?

We need to get this sorted or they’ll smell it in the atrium

So … you don’t really want the protesters to leave … ?

I mean for the launch.

Lou carefully studies the plan of the sub-basement. Searching for a way out … .. Through twists and turns they come at last to an underfloor ‘void’ on the architect’s plans; an area the size of an auditorium, left empty to allow ventilation for temperature regulation and air … In fact, it is densely packed forest of discarded and mismatched chairs.

And she does. Jess abandons them in the void and heads back to join the protest. Rosa and Lou climb into the ventilation duct, and, so long as Rosa goes first and Lou keeps reminding herself that she has no choice, they crawl along the gently sloping channel. It’s wide; not too bad. Eventually, it reaches a traverse section, stretching on one side to microbiology and engineering; on the other towards the university’s museum – one of the world’s leading collections of treasures from Egypt and Sudan. They keep tunnelling, excavating, along and under Lou’s plans of the building. They follow their noses, navigating back round to the main atrium by the smell of the blocked drains. At last, they hear the singing of Extinction Rebels. Soon, they will crawl under the glass atrium itself, through underfloor wiring and pipes, out into the street. Briefly visible, Lou will press her fingers against her own glass ceiling to drag her body through the narrowest section of their escape. If she dies here, she thinks, her final moments in a glass coffin will be live streamed on Instagram. Rosa senses her anxiety and pulls Lou aside to rest.

Outside, Superstar academic Simeon Blunt, headhunted by the University and waiting for his moment to be parachuted into the top job, is the first to notice the flames from the basement as the flood waters short circuit the electrics and the tower of quilted toilet paper ignites …

‘Drafting’ City Dionysia

The festival of the Great Dionysia in fifth century Athens was essentially a drama festival in a civic setting with a range of performances known for ironic and subtle questioning from dangerous tragedy to uproarious comedy (Goldhill Citation1987). Its dramaturgy not only implied a formal relation between a literary text and its staging but also drew together space and movement in a composition of particular theatrical events. Through an interplay of norm and transgression, the festival both lauded the polis as well as depicted the stresses and tensions of a polis society in conflict by creating a ‘civic discourse’ not just through the plays in performance but by creating a social space for readings of the play to take place (Finkelberg Citation2006). The latter were as important as the spectacle itself which had ‘an emotional attraction of its own’ (Finkelberg Citation2006, 20), pointing to the emergence of a new critical literary sphere. It was this dramaturgical potential of the ‘preplay’ that became crucial to our version of Wasteland where we sought a similar artistic illusion of a dramatic performance. This was, of course, triggered largely by the pandemic that made an audience attached to a conventional stage impossible, but not the only reason.

‘Preplays’ involving multiple instances of reading the play at different locations (both virtual and real) became as crucial as the final staging of the play itself. The term ‘preplay’ is used by Goldhill (Citation1987) in reference to the ceremonial events that preceded the actual play. They were not necessarily connected to the play itself while here it is invoked as something that is very much hinged to the play. For us, preplay is a mode of anticipation that allowed us to work out how to respond to the uncertain and disruptive nature of the pandemic. For, what we were keen on was not only eliciting emotive reactions from the usual audience-at-a-distance but an intellectual involvement that at times turned the play into an academic exercise. In the very first online ‘reading’, the playwright acknowledged it as a draft, but by not finalising the text into a ‘finished’ performance, it was being opened up to an extended world of critical inquiry. Also, instead of opting for a live Q&A with the online audience, questionnaires were distributed after the event to the thirty-five viewers who had logged in to watch this first ‘reading’.Footnote7 At the risk of becoming abstract and self-absorbed, the text turns into a mediated encounter between the scene and the site, marked by what Berlant (Citation2011:, 2) has referred to as the becoming-event – ‘events are not self-present, but incidental, smaller dents that are always becoming-event’. This double movement of becoming and event borrows from Deleuze’s (1990 cited in Bankson Citation2017) understanding of the event as something that is indeterminant and incipient where ‘becoming is an emergent immersive process that exists in the liminal multiple lines of flight and multiple encounters that encourage experimentation and improvisation’ (LeBlanc et al. Citation2015, 356). Preplay, in this context, is an identity text for these becoming-events, intended as an invitation to explore, to affect and be affected. Given that the becoming-event does not reside in a single personal encounter – ‘it resides in a multiplicity of encounters that are social and collective … .as affect [it] resonates, reverberates, echoes across time and space within and beyond the event’ (Irwin Citation2013, 207), the preplay’s emphasis on ‘becoming’ turns it into a Barthesian ‘theatre of production’, where spatiality and intertexuality confirm the text itself as a performative event (Bushell Citation2007). Equally, they take incidental events from elsewhere converting them into ‘a scene of thought performed in unusual modes of critical intensity, theoretical acumen, or referential familiarity … an opportunity for surprise learning’ (Berlant Citation2004, 447). It involves a blurring, blending and reversing of theatre fictions and the reality of our built surroundings, inspired by Milo Rau’s ‘The City Theatre of the Future’ (Rau Citation2021). Our City Dionysia is conceived in this sense of the civic – the site specificity we employ is not simply in the way of experimental theatre practices but more about an urban storytelling where the site is recreated in endless possibilities of untold narratives within an ephemeral spatio-temporality of the city. It reminds us of Gertrude Stein’s ‘landscape play’ (Voris Citation2016) where, the continuous present of the pandemic structures the play (un)intentionally by privileging the recursive elements of becoming-events.

Becoming-event 1: Waste(d) labour

One such becoming-event that the play sets into creative motion is the Independent Workers’ Union of Great Britain (IWGB) strike action at UCL towards the end of 2019 against their employers, the outsourcing companies Sodexo and Axis. Formed in 2012 as an offshoot smaller independent union focussing more on precariously engaged migrant workers, the strikes in 2019 were organised to end the outsourcing of cleaners, security, and maintenance staff demanding instead direct employment by UCL (Cury Citation2021). The play steps into this terrain of collective action not quite mimicking real-life events even as it borrows certain references such as the targeting of the Student Centre by the strikers through subtle subversive tactics including fly-posting as a means of confrontation. It offers instead a more meditative take on the strike action employing a temporal register that is simultaneously diachronic and synchronic. Using Milo Rau’s tactic of a lecture-style voice-led performance, the play follows the twists and turns of the actors/characters’ own biographies to bring in questions of wasteland around body and labour. Thus, seen through the eyes of the cleaner Rosa, what we confront is the singularity of her own circumstances which doesn’t easily assume her complicity in such collective action. While there is a sense of the dramatic in the way the Student Centre is occupied in the play rather than the modest disruption attempted in reality, it is based on the communication of affect rather than emotion or as Berlant (Citation2008:, 4) explains, ‘the difference between the structure of an affect and the experience we associate with a typical emotional event’. Not taking for granted Rosa’s embodied relationality with the collective struggle, the play picks up the awkwardness of such assumptions through conversations between Rosa and Jess mainly, where Rosa’s aspirations for better social existence doesn’t necessarily see it happening via the becoming-event of protest. Having been nurtured within the academic environment, the play more critically sees the latter against an extended activist atmosphere, formulating the event within an historical present where there is no obvious ground for solidarity.

Later. Maybe half an hour. We are back in Lou’s office. All three women are here. Notes and post-its litter the floor. Rosa notices that they are everywhere except the bin. Lou stares at Jess; her face a picture of furious disbelief …

Have you heard of ‘Extinction Rebellion’, Rosa?

Revolution?

Environmento protesto?

This is the most sustainable fucking building on any campus in Europe!

Rosa, some students who care about the environment, think the new Urban Centre is all show. Too little, too late. They’d planned protest at the launch. My housemate invited me to a meeting. I couldn’t go because I have to work -

So you thought you’d just shut down the entire fucking building instead?

It’s not my fault! After you slagged off my outline –

Wait, what? I critiqued your incoherent garble …

You said travel. ‘Talk to people’. So, I talked to Rosa, who is in the Independent Workers Union of Great Britain, and then talked to my housemate.

Rosa? (forcing herself to remain calm) As I said, I am completely supportive of your strike and all the cleaners’ demands to be brought back in-house -

Oh no, no no! Protest is nothing to do with me!

Rosa gets no overtime or sick pay and they’re making her clean blocked toilets! Rosa, I messaged my housemate after my interview with you … They want to support you. So, they’ve occupied the building …

Is no support! Is bad for us! Very bad.

Take Rosa downstairs, and say she wants them to leave –

No, no. No quiero filmar mi cara -

They’re live streaming the occupation.

Se verá como las dejo! Me, protesta (it will look like I let them in)

Oh no, no. my boss – muy exigente. Mr Blunt, he is everywhere, como un fantasma – con un millon de ojos

A million ears?

A few scenes later:

Like an altar to the abandoned self; LED torches, a mirror. Piles of folded clothes. An imposing ziggurat of toilet paper, like an igloo … around

a huddled form

Dios mío, ¿un cadáver? (my God, a dead body?)

Is that a dead person?

Hello? Are you alright?

Don’t touch him -

(relief) It’s a … sleeping bag

Looks like a homeless person sleeping here.

(crosses herself) ¡Dios mío, es Jesús quien nos ha seguido hasta aquí!

(… Jesus has followed us here!)

Rosa? Do you know who this is?

Is nothing to do with me. Es un fantasma.

She says its a ghost

How can it be? This is a brand new building.

Ghosts migrate …

Actually, it’s Malcolm Blunt who’s sleeping in the sub-basement. He’s discovered, since his wife chucked him out, that a SODUCO supervisor doesn’t earn enough to live near a central London university. Six years from retirement, he’s come to rely on the incentive bonuses he gets for sanctioning staff. Blocked toilets? Blame it on the cleaners, or the management deputising for cleaners during the strike. This story isn’t about Mr Blunt.

Estos fantasmas son mios. Cleaners’ ghosts … .

Are we to say that those who are excluded are simply unreal, disappeared, or that they have no being at all – shall they be cast off, theoretically, as the socially dead and the merely spectral?

Becoming-event 2: Encountering the Anthropocene

Another instance that ‘plays’ itself into the dramaturgy is less about one particular event where, following Deleuze’s (1990 cited in LeBlanc et al. Citation2015) reference to the event as a process, this becoming-event is shaped by liminal encounters between the play and the building where the differences between unstaged and staged activity is more than a matter of applying ‘transcription practices’ (Goffman 1974 cited in Smith Citation2013). The former (the play) engages the performative quality of the latter (the building) as an object-event transformed into a fluctuating ‘theatre of matter’ (cf. Deleuze 1993 cited in Hannah Citation2019). Noted for its rationale architecture in a conservative setting, almost every award has commended the building for its ‘green’ credentials, environmental excellence and commitment to exemplary sustainable design. To this end, elements such as the already noted atrium are visibly employed to facilitate convenient natural ventilation alongside other features such as the mandatory rooftop solar panels and ground pumps. Its sober aesthetics largely due to the extensive use of exposed concrete (in-situ and pre-cast) is also flagged as a material essential for the building’s thermal mass. For architects and builders involved in its realisation, the use of concrete was both functional and visual, involving complex co-ordination between the architect, engineer, main contractor and two specialist concrete contractors. Descriptions of the decision-making as well as construction processes explaining their installation itself recalls something performative (masculinity). What is more intriguing is their conviction that ‘concrete was key to our ‘fabric first’ environmental strategy’.Footnote8

The pervasive presence of concrete through its appeal to mass production and standard form within twentieth century’s modernisation blueprint has been noted by observers for not only its deliberate disruption of a bourgeois aesthetic of discrimination but also its robustness signifying the aesthetic of state power all over the world (Harvey Citation2010). And yet, it is also the dominant face of modern ruin landscapes marked by decaying and crumbling concrete, not dissimilar to Eliot’s ur-modern material and ideational environment of The Wasteland. Thus, against assumptions of its durability, critics have begun to discuss its manifestation as an unstable power (ibid.). Questions around its instability have arisen in recent years around its relentless use leading to concerns that as the second-most produced and consumed substance on earth after water, it is responsible for 8–9 percent of the total greenhouse gas emissions (Miller Citation2018). Behind its potent attribute of binding together elements that otherwise fail to cohere is the fact that the material processes involved in its production conceals the messier concerns of land appropriation, labour conditions, extraction of resources and devastating environmental impact (Fivez and Motylińska Citation2022). However, as an industry that relies on economies of scale and high capital investments for its huge profits, its ubiquity has an assured ally in architecture. As a result, instead of looking for alternative (natural) materials to concrete as a material choice, emphasis is on mitigating it through supplementary cementitious materials, which themselves are waste by-products from other industries.

Such measures persisting with the modern trope of concrete turns the building into a chimaera blithely ignoring the fact that concrete as a matter is the object source of accumulation in the Marxist sense. If we are to use it to address global environmental crisis, then its conspicuous materiality indexing clear ecological ambitions should be challenged and rejected, not simply modified. The harsher reality is the fact that the promise of durability that characterises modern uses of concrete marks not only the conclusion of the Holocene but more importantly the origin of the Anthropocene (Simonetti and Ingold Citation2018). Placing it within a geological timeframe highlights it as a politically and affectively charged aggregate whose ‘transformative outcome is very much the contingent result of an encounter, at a specific historical moment, between particular subjectivities and the materiality of cement and concrete’ (Archambault Citation2018, 694). It is this sense of encountering the disruptive inorganic ‘to attend to the situated, historicised, and political composition of both our materials and our experiences’ (Tironi et al. Citation2018, 187) that is addressed in the play when Lou (the academic) mockingly tells Jess (the student):

Ok … firstly (improvising until autopilot kicks in), interrogate more widely. Megacities? Some fascinating work on Rio, Mumbai, homeless people living literally underground. Pick a novel case study. Abuja? Nigeria? Replaced Lagos as the capital in 1991, the first completely planned modern city in West Africa. Bring in the cement industry – ‘grey gold’. Did you know, a popular wedding present in Nigeria is a bag of cement?

(Looks at Jess, but is practicing her speech)

(Re)enactment

The unfolding situation of the (post)pandemic has given a new meaning to ‘the sense of ongoingness in the durational present’ (Berlant Citation2008, 5), not because it is caught in a cyclical loop of an apocalyptic vision as some would argue but rather that we are trying hard to fully inhabit our present, cognitively and affectively, as our ‘now’ (Chakrabarty Citation2021). In an evasion of history and time, the now is inherently speculative, creating new norms, and keeping almost anything and everything we undertake open. And this is what happened to the play, so far. Opening it up critically risked turning it into an overdetermined exercise of mattering and inter-relating almost everything as contingent events. However, the drafts produced or what we refer to as the ‘preplays’ are not simply variations of the same but different iterations that coexist and enliven each other. They are the work of the draft that Higgins (Citation2022) alludes to – unhurried, unfinished, improvised and provisional. Privileging an open devising and rehearsal process over that of a formal production was necessary for the play to take gumption in not only the unpredictable consequence of events but also to come to terms with its situatedness. The play’s prompts for several emergent situations is clearly pre-figurative, drawing on the surrounding politics of dissent for a fictional mediation of troubled times (from the IWGB workers’ strike to the lockdown and contestations over practices of climate futures). It does this by opening up the material-discursive possibilities of enactments from pre-enactment to re-enactment in an effort to reconfigure dramaturgy. Here, rehearsal is equally the performance using affective strategies and embodied knowledge in a site-specific setting. Its iterative process provided a method of inquiry into the interactions between thinking and practice, bringing a tangibility to the play even without the benefit of a stage production. Even though text-based without the frills of visual effects, these re-enactments, as Mosse (Citation2020) deftly points out in her analysis of radical theatre director Milo Rau’s work, suggest an engaged theatre practice, a way of reconceptualising temporality in performance with an affective impact that is a form of social experience, fluid and mobile.

Notable for us is the non-linear way in which our re-enactments developed as ‘readings’, creating situations with political potential and even a utopian dimension (). In the first online reading of the draft, audience responses were collated as a questionnaire survey alongside a workshop with the actors. It was reassuring to see how quite a few grasped the onscreen enactment in a deliberately sequential manner as the character THE PLAY who would have been simply the narrator in a conventional format emerged here in a crucial role to single-handedly perceive and synthesise concurrently the various scenes. Soliciting audience responses here was not because we felt this was the way to do it, and neither was our intention to turn their subjectivities into performance material. It was a fine line asking questions in an evaluative manner, knowing very well the limited nature of such a transaction as we sought to refrain from ‘entrapping’ the audience into ‘getting involved’ or ‘becoming involved’ (cf. Kolesch and Schütz Citation2022). While obvious comments around their sensory modalities were made around technological glitches, an important revelation was around the precarity of the actors themselves against the demands of a digital infrastructure as one actor reminded us about the unreliability of an old and ageing laptop. The use of workshops rather than rehearsals made realism still viable in a pandemic condition, against the impossibility of staging worlds. In the second ‘reading’ which took place as part of a UCL Festival, instead of focussing our efforts on staging the play or building a mise-en-scéne in the traditional sense, we continued our focus on the draft as one that is imminently readable. Reading the draft, in fact, became a project as it was revised and updated continuously as often as new vectors of thinking were introduced, emerging as a form of practice that is ‘less interested in a relational aesthetic than in the creative rewards of collaborative activity’ (Bishop Citation2006: n.p.). This was a way of circumventing the rampant ‘experience industry’ that has emerged in the (post)pandemic digital theatre, forcing a hybrid subjectivity that we didn’t want to automatically embrace.

Figure 4. Becoming-events and ‘preplays’ – IWGB strike at UCL and on-site readings as ‘unfinished’ performance; © Nicola Baldwin.

At the same time, it is clear that re-enactments, at some point, will need the experiential dynamics of a tangible site-specific setting to ensure that the play doesn’t slip into a self-referential end-game. It requires theatre as an embodied place where, ‘we cannot just critique existing political structures but need to actively commit to rehearing their alternatives’ (Mosse Citation2020, 66). A theatre with such a narrative agency is one that is bound not by its ‘arts’ but its political-economic moment. Thus, the building, UCL Student Centre, is enlisted here as the subject(ive) site of re-enactment, the counterpoint for a lived, felt, phenomenological performance with its architecture serving conveniently as a theatre in disguise. In proposing to use its very structure as a narrative site, it is not that we are seeking commensurability with the building inside and outside the play. Neither is the use of a nontheater space a deliberate quest for a new theatre form because we might have to do away with the conventions of theatre-going. It is instead an acknowledgement that ‘theatre exists in varying degrees, in a continuous spectrum that ranges from ‘very theatre’ to ‘no theatre at all’’ (Ferdman Citation2018, 37). And this is what the building offers – a performative site for all the inter-subjective exchanges within the text, all the storied matter encoded with an array of meanings that challenge the cultural dominants of our present:

But the ‘ground’ is not just a backdrop or a context; it’s the sensed social-material-aesthetic atmospherics resonant in a scene, the threshold onto worlds of expressivity in a problematics. It’s what sends people bouncing at the drop of a hat or sets off a line of associations at the sound of an accent. It’s what’s already taking off, a space where dogs sometimes master the art of deadpan. (Berlant and Stewart Citation2019, 34)

Coda

In a more recent extension of our collaboration, we organised a roundtable in early December 2022 to mark the publication centenary of TS Eliot’s Waste Land. With a specific emphasis on Eliot’s Waste Land in the Anthropocene, we invited a range of speakers to subject the Waste Land to an analytic that is dominated by the Anthropocene’s sense of the deep-time present. Taking questions that emerged from the play, we returned to the idea of the Waste Land in its creative form, an embodiment of poetic modernism, carrying it forward a hundred years to read it not so much in retrospect but to know it again in the foreshadow of the Anthropocene. Accompanying this erudite discussion held at the UCL Student Centre was a monologue by one of the characters from the play (Jess, the student) en-acted for the first time ‘on-site’ while drawing attention to the building’s self-proclaimed ecological legacy. This was played out in a sense of ‘symbolic interaction’ with the scene/site without any audience scrutiny. And yet, its performativity exposes further questions of whether there can any longer be a pure theatrical fiat. What was reassuring for us was the way its unprogrammed non-digital enactment illuminated ‘the constructed, creative, contingent, collaborative dimensions of human communication’ (Conquergood 2002 cited in Alrefaai and Spangler Citation2022). This, for us, was the possibility of the posthuman theatre in the Anthropocene where the question of whether our collaborative ‘product’ as presented is a ‘play’ was irrelevant. As Jess’s words literally resonated off the concrete surfaces in the great atrium space, we came to view our collaboration as a ‘life process’ that is closely aligned with research methods of deep interpersonal and political engagement, sensitive to the power dynamics both within and outside the creative process.

Writing this piece has been essential to what we undertook as collaborators, crossing the domains of academic and fictional writing, finding something in-between (that hybrid text) enmeshing creative artistic practice with critical analysis. Both the play and this report constitute an act of experimental writing that confounds the distinctions between these different written worlds. In a sensitive review of Berlant and Stewart’s (Citation2019) The Hundreds, a young scholar Philbrick (Citation2019:, 344) notes how, for the authors, ‘humanist critique just keeps snapping at the world as if the whole point of being and thinking is just to catch it in a lie’ (42). It is

part of a practice of finding other ways to critique and create … give us tools to think, feel, and make our way through … ..there is another kind of invitation: to write together within the cracks of the new ordinary, to find alternative sources as institutions fall apart, and to keep in sync while taking in what isn’t.

Our collaboration, in this sense, speaks to the ontological challenge of Wasteland’s performativity as a narrative form when the emphasis is on a process of storying, a lively and emergent technique that gestures towards interactional intricacies (Wardle Citation2018). Amidst the pressures of reconciling to a (post)pandemic now, this slow writing was essential to the way the play evolved – through a process of producing online performative readings and feedback sessions as well as a site-specific performance that took place beyond the frame of the play itself. Unfolding the play in this manner is an effort to escape our historical present that is entwined with a historical future (Chakrabarty Citation2021) and akin to Rose’s (Citation2013:, 6) explanation of slow writing as a way of writing about the Anthropocene: ‘slow work, not only in the sense of taking time, slowing down, and doing things carefully, but also in the sense of living in the present temporalities, localities, and relationalities of our actual lives’. Thus, unlike Eliot’s The Waste Land seen as a (quasi)apocalyptic icon, the play considers utopia not as some kind of fantasy magical levelling but one filled with emancipatory possibilities. Here, the play attempts two things – it explores the potential of oral storying dramatised via rehearsals/readings as well as using the draft as a process to bring what is within the play (the building/the scene) out as a means of staging its performance (the site). By converting the (building) object into a scene, it strives to hold open, not the door of the stage but that which is unstaged.Footnote9

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pushpa Arabindoo

Pushpa Arabindoo is an Associate Professor in Geography & Urban Design at the Department of Geography, University College London. She is also the co-director of UCL Urban Laboratory responsible for the priority research theme Wasteland.

Nicola Baldwin

Nicola Baldwin is a playwright and scriptwriter and Visiting Fellow at UCL’s Institute of Advanced Studies. She was UCL Creative Fellow (2019-2020) at Urban Lab and IAS for their joint research theme of ‘Waste’, working in collaboration with Dr Pushpa Arabindoo on “The City Dionysia”.

Notes

1 The work of geographer Vinay Gidwani (Citation1992) and sociologist Myra Hird (Citation2012) is a point of reference here.

3 There are a few exceptions such as Vittoria di Palma’s (Citation2014) meticulously researched and richly illustrated monograph, Wasteland, using a variety of mixed historical sources to chart the conceptual history of Wasteland, albeit in seventeenth and eighteenth-century Britain.

6 The building’s central feature is a giant wraparound stair with inhabited landings and loggias. While the building has been complimented for its sober, understated elegance, there is something equally dramatic in its meandering split stairs in the atrium that sets the scene for social interactions.

7 This was a deliberate decision in terms of not pushing too much the possibilities of an interactive platform in this instance with audience choice limited to either watching the actors or following the text that was pegged to the narrator of the play. This version can be watched here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BbtPPcKUIFQ

8 https://constructionmanagement.co.uk/sustainability-honours-concrete-ucl/; Accessed online 12 September 2022

9 Audio of this second reading at UCL’s Quo Vadis Festival in June 2022 can be heard here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E0IYZWa9EME

References

- Alrefaai, N., and M. Spangler. 2022. “The Beekeeper of Aleppo: A Transnational Collaboration.” Text and Performance Quarterly, doi:10.1080/10462937.2022.2088850:1-7.

- Archambault, J. S. 2018. “‘One Beer, one Block’: Concrete Aspiration and the Stuff of Transformation in a Mozambican Suburb.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 24 (4): 692–708. doi:10.1111/1467-9655.12912.

- Bankson, S. 2017. Delueze and Becoming. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Berlant, L. 2004. “Critical Inquiry, Affirmative Culture.” Critical Inquiry 30 (2): 445–451. doi:10.1086/421150.

- Berlant, L. 2008. “Thinking About Feeling Historical.” Emotion, Space and Society 1 (1): 4–9. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2008.08.006.

- Berlant, L. 2011. Cruel Optimism Becoming Event: A Response. New York: The Barnard Center for Research on Women and The Center for Gender and Sexuality Studies at NYU. http://bcrw.barnard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/Public-Feelings-Responses/Lauren-Berlant-Cruel-Optimism-Becoming-Event.pdf.

- Berlant, L., and L. Edelman. 2014. Sex, or the Unbearable. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Berlant, L., and K. Stewart. 2019. The Hundreds. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Berlant, L., and K. Stewart. 2022. “Some Stories, More Scenes.” The Sociological Review 70 (4): 856–859. doi:10.1177/00380261221106513.

- Bishop, C. 2006. “The Social Turn: Collaboration and its Discontents.” Artforum International 44 (6): 178–183.

- Bushell, S. 2007. “Textual Process and the Denial of Origins.” Textual Cultures: Text, Contexts, Interpretation 2 (2): 100–117. doi:10.2979/TEX.2007.2.2.100.

- Capece, K. C., and P. Scorese. 2022. “Introduction: Pandemic Performance and Aliveness as art.” In Pandemic Performance: Resilience, Liveness, and Protest in Quarantine Times, edited by K. Capece, and P. Scorese, 1–18. London: Routledge.

- Chakrabarty, D. 2021. “The Chronopolitics of the Anthropocene: The Pandemic and our Sense of Time.” Contributions to Indian Sociology 55 (3): 324–348. doi:10.1177/00699667211065081.

- Cury, T. 2021. “The Aesthetics of Protest in the UCL Justice for Workers Campaign.” Interface: A Journal for and About Social Movements 13 (1): 272–299.

- de Certeau, M. 2002. “Spatial Stories.” In In What is Architecture?, edited by A. Ballantyne, 72–87. London: Routledge.

- Edensor, T. 2005. “The Ghosts of Industrial Ruins: Ordering and Disordering Memory in Excessive Space.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 23 (6): 829–849. doi:10.1068/d58j.

- Eliot, T. 2002 [1922]. The Waste Land and Other Poems. London: Faber and Faber.

- Ferdman, B. 2018. Off Sites: Contemporary Performance Beyond Site-Specific. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Finkelberg, M. 2006. “The City Dionysia and the Social Space of Attic Tragedy.” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 49: 17–26. doi:10.1111/j.2041-5370.2006.tb02328.x.

- Fivez, R., and M. Motylińska. 2022. “Cement as Weapon: Meta-Infrastructure in the “World’s Last Cement Frontier’.” In The Routledge Handbook of Infrastructure Design, edited by J. Heathcott, 40–50. New York: Routledge.

- Gidwani, V. k. 1992. “Waste’ and the Permanent Settlement in Bengal.” Economic and Political Weekly 27 (4): PE39–PE46.

- Goldhill, S. 1987. “The Great Dionysia and Civic Ideology.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 107: 58–76. doi:10.2307/630070.

- Hannah, D. 2019. Event-space: Theatre Architecture and the Avant-Garde. London: Routledge.

- Harvey, P. 2010. “Cementing Relations: The Materiality of Roads and Public Spaces in Provincial Peru.” Social Analysis 54 (2): 28–46. doi:10.3167/sa.2010.540203.

- Higgins, M. 2022. “What is in the Draft: A Reflection on Precarity in Kivu Ruhorahoza’s Europa: ‘based on a True Story’.” Empedocles: European Journal for the Philosophy of Communication 13 (1): 11–24. doi:10.1386/ejpc_00038_1.

- Hird, M. J. 2012. “Knowing Waste: Towards an Inhuman Epistemology.” Social Epistemology 26 (3-4): 453–469. doi:10.1080/02691728.2012.727195.

- Iovino, S. 2010. “Ecocriticism and a non-Anthropocentric Humanism: Reflections on Local Natures and Global Responsbilities.” In Local Natures, Global Responsibilities: Ecocritical Perspectives on the new English Literatures, edited by L. Volkmann, et al., 29–53. Amsterdam, New York: Rodopi.

- Iovino, S., and S. Oppermann. 2012. “Material Ecocriticism: Materiality, Agency, and Models of Narrativity.” Ecozon@ 3 (1): 75–91. doi:10.37536/ECOZONA.2012.3.1.452.

- Irwin, R. L. 2013. “Becoming A/r/Tography.” Studies in Art Education 54 (3): 198–215. doi:10.1080/00393541.2013.11518894.

- Klich, R. 2012. “The ‘Unfinished’ Subject: Pedagogy and Performance in the Company of Copies, Robots, Mutants and Cyborgs.” International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media 8 (2): 155–170. doi:10.1386/padm.8.2.155_1.

- Kolesch, D., and T. Schütz. 2022. “Forced Experiences: Shifting Modes of Audience Involvement in Immersive Performances.” In Routledge Companion to Audiences and the Performing Arts, edited by M. Reason, L. Conner, K. Johanson, and B. Walmsley, 111–123. London and New York: Routledge.

- Lamb, J. B. 2021. “Storied Matter: Waste and Waste Lands in Thomas Hardy’s The Return of the Native.” ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 00 (0): 1–26. doi:10.1093/isle/isab077.

- LeBlanc, N., S. F. Davidson, J. Y. Ruy, and R. L. Irwin. 2015. “Becoming Through a/r/Tography, Autobiography and Stories in Motion.” International Journal of Education Through Art 11 (3): 355–374. doi:10.1386/eta.11.3.355_1.

- McIntire, G. ed. 2015. Introduction. In The Cambridge Companion to the Waste Land, 1–6. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Miller, S. A. 2018. “Supplementary Cementitious Materials to Mitigate Greenhouse gas Emissions from Concrete: Can There be Too Much of a Good Thing?” Journal of Cleaner Production 178: 587–598. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.01.008.

- Morrison, S. 2015. “Geographies of Space: Mapping and Reading the Cityscape.” In The Cambridge Companion to the Waste Land, edited by G. McIntire, 24–38. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Morton, T. 2013. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the end of the World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Mosse, R. 2020. “Re-enacting the Crisis of Democracy in Milo Rau’s General Assembly.” In Theatre Institutions in Crisis, edited by C. Balme, and T. Fisher, 56–69. London: Routledge.

- Mosse, R., et al. 2022. “Viral Theatres’ Pandemic Playbook - Documenting German Theatre During COVID-19.” International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media 18 (1): 105–127. doi:10.1080/14794713.2022.2031800.

- Muecke, S. 2002. “The Fall: Fictocritical Writing.” Parallax 8: 108–112. doi:10.1080/1353464022000028000.

- Oppermann, S. 2016. “Material Ecocriticism.” In Gender: Nature, edited by I. v. d. Tuin, 89–102. Farmington Hills MI USA: MacMillan Reference.

- Palma, V. D. 2014. Wasteland: A History. New Haven and. London: Yale University Press.

- Philbrick, E. 2019. “The Hundreds.” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 29 (3): 343–345. doi:10.1080/0740770X.2019.1671108.

- Rau, M. 2021. “Ghent Manifesto.” Theater 51 (2): 21–23. doi:10.1215/01610775-8920468.

- Rose, D. B. 2013. “Slowly ∼ Writing Into the Anthropocene.” TEXT 17 (Special 20): 1–14. doi:10.52086/001c.28826.

- Simonetti, C., and T. Ingold. 2018. “Ice and Concrete.” Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 5 (1): 19–31. doi:10.1558/jca.33371.

- Smith, G. 2013. “The Dramaturgical Legacy of Erving Goffman.” In In The Drama of Social Life: A Dramaturgical Handbook, edited by C. Edgley, 57–72. London: Routledge.

- Tironi, M., M. J. Hird, C. Simonetti, P. Forman, and N. Freiburger. 2018. “Inorganic becomings: Situating the Anthropocene in Puchuncaví.” Environmental Humanities 10: 187–212. doi:10.1215/22011919-4385525.

- Voris, L. 2016. The Composition of Sense in Gertrude Stein’s Landscape Writing. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wardle, D. 2018. Storying with Groundwater: Why we cry, School of Media and Communication. Melbourne.: RMIT University.

- Yusoff, K. 2018. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.