ABSTRACT

This paper examines the interaction of sound and vision in audiovisual works for solo electric guitar, providing an overview of existing compositions before exploring in depth the approaches utilised in two new works commissioned by the author. Multimedia works which combine sound and vision represent a minority of the contemporary western art music repertoire, and are rarer still in works involving the electric guitar. The use of visuals in the small literature of audiovisual works for solo electric guitar varies widely, ranging from pre-recorded videos which simply play back over the course of a performance with no temporal alignment between sound and vision, to complex lighting mechanisms which respond to the music in real-time with clear parameter mapping. The bulk of the repertoire, however, demonstrates limited gestural synchronisation between the two media, with composers creating audiovisual cohesion through extra-temporal means. The works commissioned by the author – Svart-Hvít Ský á Himni by Icelandic composer Gulli Björnsson, and especially Akrasia by Australian composer Victor Arul – run counter to this trend, situating them as outliers which push the boundaries of parametric mapping in the repertoire for solo electric guitar and visuals.

1. Context

Once relegated to the fringes of the classical music industry, the electric guitar has gained increasing acceptance among composers of contemporary western art music.Footnote1 Prized for its expressive possibilities and the ease with which it can be manipulated through electronic processing, the electric guitar has amassed a substantial repertoire of solos, chamber works, and concerti by composers as diverse as Karlheinz Stockhausen, George Crumb, Morton Feldman, Steve Reich, Elena Kats-Chernin, and Jacob TV.Footnote2 While principally a classical guitarist, I have become increasingly attracted to the opportunities afforded by the electric guitar, particularly its pairing with visual elements to create immersive, multimedia works greater than the sum of their parts.Footnote3

The combination of visual elements with musical performance is by no means a recent development, dating back at least to the eighteenth century with the invention of the clavecin oculaire, a modified keyboard instrument on which depressing a key would cause a small shutter to open and a predetermined colour to be projected (Peacock Citation1988, 399). Technological advances in the twentieth century, especially the advent of the computer, have of course expanded the possibilities for visual manipulation exponentially. While interdisciplinary works which combine sound and vision present the opportunity to develop new compositional approaches and expand the viewer-listener experience, multimedia compositions represent a minority of the existing contemporary art music repertoire.

This general lack of repertoire is reflected in the very small number of works for solo electric guitar and visuals. While there is no single comprehensive catalogue of compositions for electric guitar, the German-based web database Sheer Pluck Database of Contemporary Guitar Music (https://www.sheerpluck.de) and Zane Banks’ Citation2013 dissertation The Electric Guitar in Contemporary Art Music are excellent resources, together classifying nearly 8000 works involving the electric guitar. Of the approximately 750 electric guitar compositions catalogued by Banks, only three include a visual element, and each of these utilises the guitar as an instrument in a larger chamber ensemble. Of the 7530 works featuring electric guitar identified in the Sheer Pluck Database, only 134 include a visual element, and of those only 20 are for solo electric guitar.Footnote4 In total, I have identified less than 100 worksFootnote5 for solo electric guitar with a visual component, and I have been unable to find a single work by an Australian composer.

This paucity of repertoire presents an exciting opportunity to develop new works in an area which has yet to be fully explored, and prompted me to undertake a commissioning project to expand the repertoire of this underrepresented genre. As I am a performer, not a composer, I rely on the expertise of specialists to create new works, as opposed to experimenting with the creation of new works myself. I thus commissioned Australian composer Victor Arul and Icelandic composer Gulli Björnsson to each create a new multimedia composition for solo electric guitar and visuals. I will discuss these compositions in detail by positioning them within the context of the existing repertoire, and examining their treatment of audio and visuals through an analytical approach that draws heavily on audiovisual taxonomies which interrogate the relationship between sound and vision in creating a shared temporal structure (Fuxjäger Citation2012, 120).

2. Audiovisual taxonomies

At present, there exists little scholarly literature that examines the electric guitar’s use in works that incorporate a visual element, almost certainly because there are so few of them. The study of audiovisual works more broadly, however, is an immense field with rich literature, and has served to guide this inquiry.Footnote6 Terminology and classification of works can vary widely by the individual, and thus requires some preliminary discussion to establish a common lens through which to view the repertoire for solo electric guitar and visuals.

‘Visual music’ is a term that recurs throughout this study, and indeed is often used to refer to audiovisual works more generally. Traditional visual music dates back to the early twentieth century, and is primarily associated with an artist's abstract visual representation of sound, as in the silent Lumia works of Thomas Wilfred or the paintings of Kandinsky.Footnote7 In contemporary practice, however, it has become something of an umbrella-term encompassing nearly any work with both an auditory and visual component (Lund Citation2016). While numerous scholars and practitioners have proposed new definitions of contemporary visual music, for the present study I will adopt the view espoused by Brian Evans: an art form that combines sound and time-based imagery in works which are typically, but not exclusively, non-narrative and non-representational (Citation2005, 11).

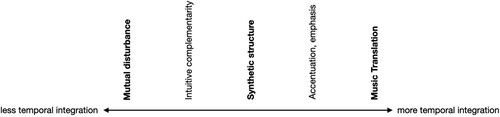

These broad classifications are instructive, but much more detailed descriptors are needed to interrogate the relationship between music and visuals. How are they integrated? To what degree do the visuals reflect musical events, or vice versa? How does the disparate information transmitted on audio and visual channels combine to create a cohesive, singular artistic output? Many taxonomies have been developed to further describe and categorise the relationship between sound and moving image, dating back to the 1920s.Footnote8 While there are multiple lenses through which to view audiovisual works, I will focus primarily on what Fuxjäger argues is the ‘central aesthetic feature’ of visual music: the relationship between sonic and visual gestures, which together create a ‘total temporal structure … in the eyes and ears of the recipient’ (Citation2012, 120). To that end, I will utilise a combination of the taxonomies developed by Anton Fuxjäger and Diego Garro () which will provide a higher degree of granularity than either system on its own, and prove the most useful in examining the relationship between sound and vision in the repertoire for solo electric guitar and visuals.

Figure 1. A continuum showing the degree of temporal integrationFootnote9 between sound and vision, with points of delineation drawn from a combination of the taxonomies defined by Fuxjäger and Garro.

While Fuxjäger and Garro approach audiovisual works from different backgrounds – the former as a visual artist and the latter as a composer – both propose categorisation along a continuum distinguished by the extent of temporal-gestural synchronisation between music and visuals. Fuxjäger groups works into three broad categoriesFootnote10 delineated by the temporal relationship between sound and vision (Citation2012, 120). Similarly, Garro (Citation2005, revised 2012) identifies four roughly parallel categories, spanning the same continuum as Fuxjäger's, which describe the degree of gestural association between sonic and visual events. It is important to note, however, that these categories are not ironclad, but merely points of delineation along a ‘continuous spectrum of possibilities’ (Fuxjäger Citation2012, 124).

2.1. The extremes – music translation and mutual disturbance

At one boundary (see ) are works with the most direct temporal relationship between sound and vision. Called ‘music translations’, these are compositions in which specific parameters of the music are ‘transcoded’ into specific visual parameters, so that musical events are also represented visually.Footnote11 The music is thus responsible for creating the temporal structure of the work, which is simply doubled by the visuals (Fuxjäger Citation2012, 120). Garro refers to such works as ‘parametric mapping’, characterised by a clear temporal coupling between one or more visual parameters and one or more sonic parameters which cause sound and vision to ‘behave in synergy’ (Citation2005, 4). This transcoding could be very straightforward and immediately recognisable – for example, the louder a sound, the bigger a visual object – or so complex that the viewer-listener is unaware of the underlying relationship. In the purest form of music translations, all visual events can be paralleled with musical events and the parameter-mapping – that is, which audio elements correspond to which visual elements – remains consistent throughout the work (Fuxjäger Citation2012, 122, 126).

On the opposite end of the spectrum from music translations are works that feature no discernible relationship between sonic and visual channels, each of which proceed on their own independent temporal timelines (Garro Citation2012, 107). Fuxjäger calls this ‘mutual disturbance’, arguing that the lack of gestural synchronisation between sound and vision will not only inhibit the viewer-listener's ability to ‘mentally synthesise’ a coherent audiovisual structure, but that the music will actually ‘disrupt the recognition of the temporal structure of the images and vice versa’ (Fuxjäger Citation2012, 120, 126).

2.2. Intuitive complementarity

Most audiovisual compositions, however, fall somewhere on a continuum between the poles of music translation and mutual disturbance. Works on the mutual disturbance end of the spectrum, with limited gestural integration between sound and vision, can still be unified through other means to create a coherent, convincing work of art – ‘visual music is more than a mapping exercise; the absence of a relationship is itself a relationship’ (Garro Citation2012, 106). Even without direct temporal synchronisation, works of intuitive complementarity feature audio and visual material which are mutually supportive in creating an intuitive psychological response that combines audio and visual events, not unlike in film music (Garro Citation2005, 4). Myriam Boucher and Jean Piché argue that the audio-visual relationships in such works are ‘anchored in complex metaphorical links where coherent meaning is assigned by the viewer-listener’; merely presenting a sound and image together is sufficient to ‘trigger a desire in the viewer-listener to make sense of the association, even if there isn't an obvious one’ (Citation2020, 14).

2.3. Synthetic structures

Occupying a position on the continuum equidistant between translation and disturbance are ‘synthetic structures’, works in which audio and visual events do not always align, but nonetheless feature enough instances of temporal correlation between them that the viewer-listener is able to synthesise sound and vision into a coherent whole (Fuxjäger Citation2012, 120). Compositions of this nature produce a more complex viewer-listener experience, where music and images work together to create an aggregate audiovisual structure from a combination of ‘different temporal informations transmitted on the auditory and the visual channel’ (Citation2012, 124).

Watkins argues that such works are the most artistically desirable: ‘If the audio and visual elements have no mapping and remain separate the work will fail to be a coherent piece of Visual Music, but if the audio-visual mapping is too close the piece will generate uninteresting perceptual relationships and at best mediocre aesthetical relationships’ (Citation2018, 62). Similarly, Garro asserts that strict parameter mapping can result in ‘audiovisual redundancy’, while the most compelling audiovisual works often achieve coherency through other means, creating sonic and visual relationships which are ‘almost immediately satisfactory and self explanatory even without any formal mapping’ (Citation2005, 6–7).

2.4. Accentuation, emphasis

Fuxjäger proposes a final category, ‘accentuation, emphasis’, which adds an additional layer of distinction halfway between synthetic structures and music translations. These works lack the consistent parameter mapping of music translations, yet nonetheless feature visual changes which coincide temporally with musical events. The aesthetic result is thus an ‘accentuation’ or ‘emphasis’ of the music's temporal structure by the images, and vice versa, as each change in one medium is doubled by the other (Fuxjäger Citation2012, 124).

Michel Chion famously describes this amalgamation of disparate audio and visual stimuli as ‘synchresis’,Footnote12 the ‘spontaneous and irresistible weld produced between a particular auditory phenomenon and visual phenomenon when they occur at the same time’ (Citation1994, 63). Chion notes that this bond can occur even when the sound and vision are totally unrelated, yet nonetheless form ‘inevitable and irresistible agglomerations in our perception’. Synchresis is, however, not an ineluctable outcome of audiovisual simultaneities, but instead a ‘function of meaning’ dependant upon ‘gestaltist laws and contextual determinations’ (Chion Citation1994, 63).

2.5. Summary

While these categories provide a useful starting point, and will indeed heavily inform our discussion, temporal-gestural synchronisation alone does not create a coherent, convincing audiovisual work. Instead, a cohesive aggregate is the result of a complex interaction of many elements, thus demanding the qualitative evaluation of sound and vision ‘within the artistic contexts established in the work’ in order to distinguish a meaningful link between them (Garro Citation2005, 7). Indeed, no single classification system comprehensively elucidates the audiovisual relationships in works for electric guitar and visuals, which range from improvisations against static fixed-media projections to interactive visuals that respond in real-time, with a direct a 1:1 relationship, to the sounds of a precisely notated live performance. Consequently, in my analysis the categories delineated by Fuxjäger and Garro will be employed within the context of a more holistic analytical approach, including additional descriptors where further differentiation proves necessary.

3. Existing repertoire

To fully consider the new works by Arul and Björnsson and position them within a broader context, it would be instructive to first examine the existing repertoire, focusing particularly on the works’ relationship between music and visuals. This is not intended to be a comprehensive categorisation of every composition for solo electric guitar with a visual element, but merely to provide an overview which illustrates the diversity of approaches that span nearly the entire spectrum of possibilities identified by Fuxjäger and Garro. While there are works situated close to either pole, the bulk of the repertoire falls somewhere in the middle, with most tending to skew towards the mutual disturbance/intuitive complementarity side of the continuum. I will briefly examine several examples in the existing repertoire before moving on to a more comprehensive discussion of the new works I have commissioned.

3.1. cords (2013) – Adam Scott Neal

Situated firmly on the mutual disturbance end of the spectrum is American composer Adam Scott Neal's cords (Citation2013b) for electric guitar, computer, and video.Footnote13 Musically, the work consists of a single-line guitar part accompanied by a drone of swelling and decaying computer-generated chords. This is paired with a video of pre-recorded footage that switches between various shots of a boat and tyres tied up with ropes on the bank of a lake, clips of a guitarist, and abstract white lines against a black screen. The vision shares no instances of temporal alignment with the audio, each of which unfold on their own separate temporal trajectories.

While the general character of both sound and vision help to create at least some degree of cohesion – the relaxed feel (Neal has indicated a tempo of crotchet equals 44) and sparse texture of the music reflects the tranquil vision of the boat and tyres gently bobbing up and down in calm water – this tenuous connection is frequently disrupted visually by the line structures and guitarist. Neither have any temporal relationship to the music, but the latter is particularly jarring, as what the performer on screen is playing bears no resemblance to what the viewer-listener is hearing. cords [sic] is thus an example of mutual disturbance: the temporal structure of the visuals disrupts the temporal structure of the music, and vice-versa. ‘Pure’ mutual disturbance works in which there is no discernible relationship between sonic and visual channels, however, are quite rare in the existing repertoire for solo electric guitar and visuals.

3.2. La escritura del dios (2010) – Alessandro Perini

At the other end of the spectrum are works with visuals and audio that are directly related and interdependent, featuring strong temporal relationships and clear parameter mapping. I have been unable to find a single example of a pure music translationFootnote14 in the existing repertoire for solo electric guitar and visuals, likely due to the artistic challenges that arise in mitigating audiovisual redundancy and maintaining engaging sonic and visual relationships in such a work. The closest is La escritura del dios (God's writing) (Citation2010b) by Italian composer Alessandro Perini,Footnote15 which lies somewhere between accentuation/emphasis and music translation. Scored for electric/MIDI guitar, live electronics and interactive video, the work utilises multiple screens and lighting effects created with VVVV, software that facilitates the programming of live interactive graphics, audio and video. The guitar features both standard audio and MIDI outputs, making possible the real-time translation of the musical performance into MIDI data for precise parameter mapping.

A quasi-programmatic composition, La escritura del dios takes inspiration from a literary work of the same name in El Aleph, a collection of short stories by Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges. Delineated into clear sections, each with distinct parameter mapping and/or gestural association, Perini conceived of La escritura del dios as a series of ‘impressions’ derived from the story, as opposed to a continuous ‘narrative thread’ (Citation2010c, 14).

After a short introduction featuring an aggressive, distorted guitar paired visually with a black screen, what look like drips of liquid (Perini calls them ‘tears’) begin falling down vertically one by one, each set in motion by a note on the guitar. The trail of each drip forms a line that remains permanently, with every pitch creating a new drip until the screen is completely full.Footnote16 The relationship between sound and vision is explicit and unambiguous: each ‘tear’ is triggered in real-time response to the sound of the guitar.

Once the screen has been saturated by the line structures, the next section with a new gestural association begins: strummed chords and string scrapes cause the lines to become increasingly bent and contorted, until an abstract amorphous structure slowly appears superimposed on the deformed lines. This new structure gradually comes in focus to reveal a jaguar, which is parameter mapped to link the opacity of the cat's image to the volume of the guitar. While the mapping has now twice changed, the new relationships are unmistakable, and help to clearly delineate sections within the work. The piece continues in this manner, and concludes by slowly disintegrating, ending in short flashes of light which are again triggered by sound.

While not always a precise 1:1 relationship, it is immediately clear to the viewer-listener that visual events are explicitly linked to sonic events. The parameter mapping is not fixed, but evolves over the course of the work, utilising a variety of shapes, textures, images and lighting mechanisms which respond in various ways to the sounds of the guitar so that the relationship never becomes sterile or predictable. The parameter mapping does, however, remain relatively consistent within each section, creating a clear temporal-gestural coupling between sound and vision which also serves to formally delineate the piece. Sonic and visual gestures that are not mapped specifically, but nevertheless occur as simultaneities, are also fused in the viewer-listener's experience through synchresis. This interactive, interdependent relationship between sound and vision stands in stark contrast to the static video employed by Neal, and would be best described as sitting on the continuum somewhere between accentuation/emphasis and music translation, or simply a music translation that is not especially ‘pure’.

Other works on the accentuation/emphasis end of the spectrum include Dan Tramte's degradative interference: wipe down equipment after use (Citation2014) for table-top electric guitar, vine videos, pedals and objects.Footnote17 The pre-recorded video is treated like a separate performer, featuring stylised video fragments of a guitar being manipulated with a variety of objects, essentially turning the work into a duo for live performer and tape.

3.3. Until it Blazes (2001) – Eve Beglarian

While the works by Neal and Perini represent the boundaries, most fall somewhere in the middle. Eve Beglarian's Until it Blazes (Citation2001a, Citation2001b), a minimalist work of variable duration for piano or plucked string instrument, digital delay and optional visuals, is an example of an intuitive complementarity. Musically, the piece unfolds via a simple procedure: a stereo delay sets up a perpetual antiphonal cross rhythm, against which short melodic patterns are repeated an unspecified number of times in a manner reminiscent of Terry Riley's In C. By accenting different pitches within each repeating pattern, new melodies emerge from the accents, and the work is structured around the gradual growth and decay of these shifting melodic patterns. The pre-recorded visuals, by contemporary American multimedia artist Cory Arcangel, are essentially a data reduction that presents an abstracted, black and white pixelated view of a streetscape that slowly increases in resolution over the course of the work.

There are no instances of direct temporal alignment between sound and vision. The video is fixed, but the aleatoric nature of the score precludes the possibility of a consistent or repeatable musical performance, resulting in music and vision which each unfold independently on their own separate timelines. Without a single point of temporal synchronisation between audio and video, one might reasonably assume that Until it Blazes is a work of mutual disturbance. Yet there is nonetheless a sense of cohesion for the viewer-listener not only in the general character of both audio and video, but also through the compositional processes applied to each. The feeling of stasis created by the incessantly repeating melodic fragments is visually paralleled in the unchanging view of a street corner. Melodies slowly come into focus and fade away with each new accent pattern, a musical process which is visually paralleled, on a different temporal trajectory, in the gradually increasing resolution of the pixelated streetscape.

As such, this work would squarely fit Garro's definition of an intuitive complementarity. The commonalities of mood and process can be intuitively interpreted by the viewer-listener, joining together audio and video despite the complete absence of temporal synchronisation: we are reminded that a convincing aggregate is the result of the complex interaction of many elements beyond mere parameter mapping. Far from the audio disturbing the temporal timeline of the video, or vice-versa,Footnote18 I would argue that Until it Blazes is a cohesive audiovisual work which creates a coherent viewer-listener experience greater than the sum of its parts.

Other examples of intuitive complementarity include MiR (Citation2006) by Karsten Brustad,Footnote19 Manuel Rodríguez Valenzuela's Light Circle (Citation2009),Footnote20 and Lies the Snake (Citation2018) by Emilio Guim.Footnote21 Sonic events are not represented visually, nor is there any consistent temporal relationship between audio and video. The overall direction of these works, however, are through various means represented on both sonic and visual channels. This relatively loose relationship between sound and vision is the most common approach in the works that I have examined, and there are seemingly endless ways to create such a piece.

3.4. Summary

These represent a synopsis of the audiovisual approaches utilised in the existing repertoire for solo electric guitar and visuals. At one end are works with no temporal or gestural synchronisation between sonic and visual events, but which through other means still create a cohesive aggregate result. At the opposite end are works with a direct temporal relationship in which sonic events are also expressed visually. Utilising a variety of compositional procedures, the majority of the repertoire falls somewhere between these two poles, but skews heavily towards the mutual disturbance/intuitive complementarity side of the continuum with limited gestural synchronicity.

4. Examination of new works

In contrast, the works that I have commissioned feature a high degree of temporal integration between sound and vision. Akrasia (Citation2021) by Victor Arul is the purest music translation of any work for solo electric guitar and visuals that I have identified, featuring consistent parameter mapping throughout the entire piece. While Gulli Björnsson's Svart-Hvít Ský á Himni (Citation2020) is best described as a synthetic structure, its consistent and immediately recognisable parameter mapping situates it squarely on the side of music translations. It should be noted, however, that these were not pre-determined outcomes. The composers were given complete artistic freedom to create an audiovisual work in whatever way they chose, and I imposed no constraints on their compositional choices nor provided any feedback between when the work was commissioned and the final version delivered.

While I was the performer of these works,Footnote22 I will discuss them from the perspective of the viewer-listener. As a player in the act of performing, there was virtually no engagement with the visual component: projected on a screen at the back of the stage, it was impossible for me to even see the visuals. And unlike the high demands of playing an instrument live, the pre-programmed patch in Max/MSP/JitterFootnote23 produced the visuals autonomously in real-time with no need for active manipulation. Nevertheless, having recorded Akrasia and Svart-Hvít Ský á Himni and spent many hours viewing and engaging with the final audiovisual product as a viewer-listener, the following discussion is from that perspective.

4.1. Akrasia (Citation2021) Victor Arul

Victor Arul is an early career composer currently pursuing a PhD in composition at Harvard University. Written for electric guitar, live electronic processing in Ableton, and live visuals in Max/MSP/Jitter, Akrasia marks Arul's first venture into composing a multimedia work, and is what I believe to be the first work for solo electric guitar and visuals by an Australian composer. Inspired by the late period works of Morton Feldman, Akrasia explores ways in which one can deviate from the goal-directed nature of historically conventional formal structures, but on a dramatically smaller scale than Feldman's mammoth multi-hour compositions.

The entire 11-minute work features a direct 1:1 relationship between sound and vision, making Akrasia the most extreme example of a music translation of any piece for solo electric guitar and visuals that I have examined. The visuals are audio-reactive three-dimensional objects in black space which respond in real-time to the sounds of the live performance. The direct sound of the guitar is sent via an interface to a laptop running Ableton for audio processing; the processed sound is then fed to a second laptop controlling the visuals via Jitter. While chance operations play a role in the final visual output of the latter parts of the work, the parameter mapping remains consistent throughout the piece: an object's size is directly correlated to the input amplitude – the louder the sound, the bigger the object.

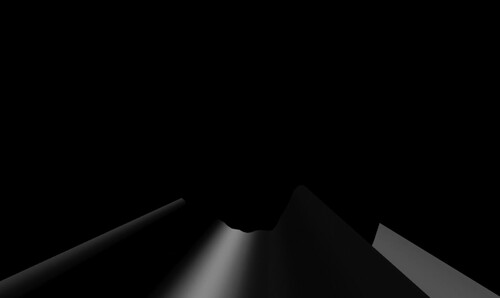

Akrasia is divided into three discrete sections which are clearly delineated both sonically through the use of different playing techniques, and visually through the use of different objects and colours. The outer sections feature preparations on the guitar, while in the middle section the guitar is played conventionally. Consequently, for ease of performance we have opted to use two electric guitars: one prepared guitar laying flat on a table in front of the performer, and a second unprepared guitar held ‘normally’ by the performer with a strap ().

Figure 2. Video still from the world premiere of Akrasia, 19 January 2022. Performed by Jonathan Fitzgerald (electric guitar) and Victor Arul (electronics).

4.1.1. Section 1

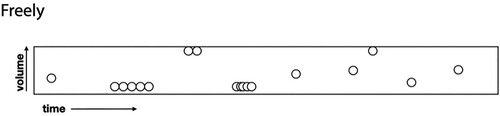

The opening section focuses exclusively on the sound created by alligator clips rebounding off the strings. With an approximate duration of three to four minutes, this first section is sparse and spacious, with conspicuous moments of silence between impulses to the clips. The notation is proportional and ambiguous, leaving much of the decision making to the performer, and ensuring that no two performances of the work will be exactly the same ().

The visuals reflect the character of the audio. As this section prominently features silence interrupted by the sound of rattling alligator clips, the visuals consist primarily of a black screen punctuated by faint, fleeting flickers of white (). The shapes here are abstract, taking the form of a constantly morphing, rotating white sheet which only appears when sound is present. There is clear, consistent parameter mapping throughout the section: in the absence of sound the screen is black; when a note is struck the sheet quickly grows from nothing, with its size directly correlated to volume. To help mitigate the predictability that can arise from such explicit parameter mapping, the object is constantly pulsating and shifting in transparency so that it never forms a solid shape, and slowly withers back to nothing as the sound decays.

4.1.2. Section 2

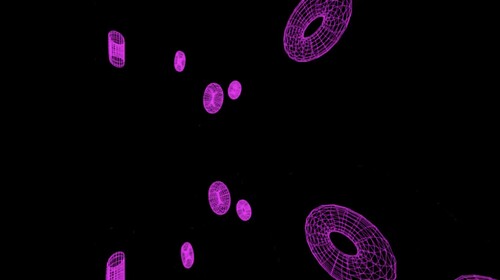

In contrast, the middle section is presented in standard notation, and played conventionally on the unprepared guitar. This drastic musical change is represented visually as a sudden shift from the morphing sheet of the previous section to multiple copies of a randomly generated geometric shape, rotating in black space and orbiting the viewer (). The volume-size transcoding of the first section, however, remains consistent: when there is no sound, the objects appear as tiny, almost imperceptible dots; when a note is struck, they suddenly increase in size proportional to the amplitude, and quickly contract back to their original form as the sound wanes.

Musically, this section is structured like a rondo, based around a precisely notated, predictable recurring ostinato figure (which heavily features the interval of a major second) alternating with unpredictable flourishes expressed in indeterminate notation (). Both visuals and audio effects help to reinforce the dichotomy of these opposing forces. The ostinato employs only a simple reverb, lending clarity and purity to the sound while dramatically increasing sustain. The aleatoric interjections, however, utilise heavy audio processing including a grain delay, low-frequency oscillator, ring modulation and timbral distortion. The visuals double this structure through the addition of a second layer of parameter mapping: the colour of the shapes change based upon the musical gesture, alternating between white for the recurring ostinato, and purple for the indeterminate phrases. Again, the relationship between sound and vision in this section is consistent and unambiguous, with the visuals duplicating and reinforcing the temporal structure of the music.

4.1.3. Section 3

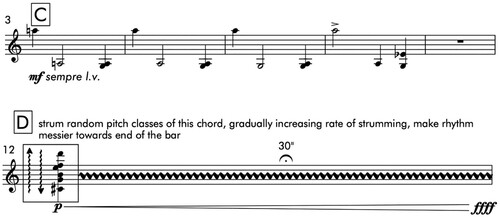

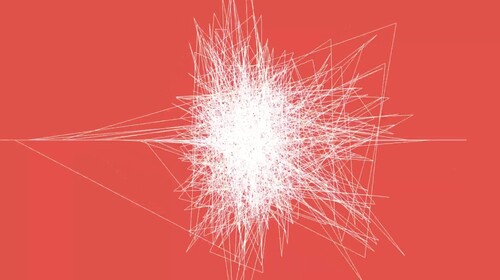

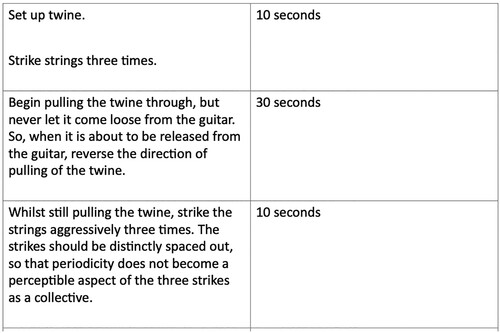

The third and final section brings the work to a climactic close with an intensely aggressive wall of sound created by the prepared guitar, matched visually by a chaotic, complex line structure (). The guitar is played with a variety of unconventional techniques and objects including running twine through the strings, striking the instrument, rattling and moving a metal rod up and down the fingerboard, shaking the alligator clips, and exciting the strings with a bass bow. These are notated as a simple set of written instructions with a timing for each action (). Heavy distortion, feedback loops and ring modulation create a sonic cacophony that intensifies over the course of the section.

This wall of sound is visually paralleled with a sudden shift to a red background, and a complex white line structure in the foreground that reacts to the saturation of inharmonic partials. In contrast to the familiar geometric shapes of the previous section, this seemingly random, frenzied object and stark red backdrop match the raw, unsettling aggression of this closing section. In spite of the highly contrasting visuals, the parameter mapping remains consistent with the rest of the work: the size of the line structure is volume dependant, and is the most sensitive to amplitude of all the visuals in the piece. The work concludes with a final ascending glissando, marking a dramatic musical shift from the inharmonic wall of sound to a single melodic line, paralleled visually by a shift in background colour from red back to the original black. This visual change not only aligns temporally with the glissando, but also provides a recapitulatory feel that creates a sense of closure on both audio and visual channels.

4.1.4. Summary

Akrasia is an example of a very pure music translation beyond what I have found in any other work for solo electric guitar and visuals. Featuring an extremely high degree of temporal and gestural synchronisation with consistent parameter mapping, the visual medium does not include any additional temporal information, but merely doubles and reinforces the temporal trajectory of the audio. That unchanging temporal relationship can become quite predictable, especially over the course of an 11-minute work. Arul has mitigated this to some degree by varying the visual objects between sections and introducing new parameter mapping as the piece unfolds, but in some ways Akrasia still falls victim to what is the primary criticism of ‘pure’ visual music – that a 1:1 direct relationship between sound and vision can quickly become sterile and predictable (Watkins Citation2018, 60).

For this work, I believe that the theatrics of the live performance are essential for its effectiveness. The physical movements of the performer – the flicking of the alligator clips, the pulling of the twine through the strings, the movement of the bass bow, which are quite distinct from, yet still temporally aligned with the computer-generated visuals – create a vital source of visual interest for the viewer-listener and play a significant role in the successful reception of the work.Footnote24

4.2. Svart-Hvít Ský á Himni (Citation2020) - Gulli Björnsson

Icelandic guitarist/composer Gulli Björnsson has carved out a niche creating multimedia works that explore experiences in nature through the combination of live instruments, electronics and visuals. Svart-Hvít Ský á Himni (Black–White Clouds in the Sky) was inspired by the dual nature of clouds – they can be beautiful and peaceful, but can also quickly become an ominous source of fear and even destruction. Björnsson sought to traverse that beauty/terror threshold in this through-composed work, scored for solo electric guitar, live electronics and visuals. The visuals feature consistent parameter mapping combined with automation and randomisation that unfold independently of the music, making Svart-Hvít Ský á Himni a synthetic structure situated towards the music translation side of the continuum.

4.2.1. Audio processing

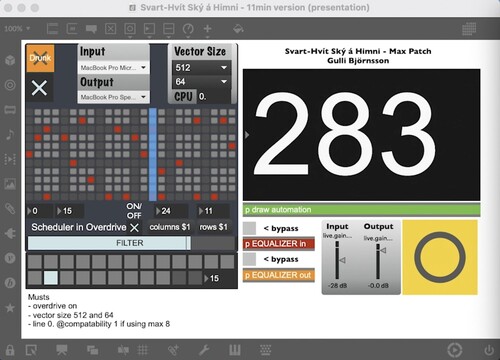

One consistent feature across many of Björnsson's compositions is the use of complex preprogrammed live audio processing effects via Max/MSP which play an integral role in shaping the formal structure of the piece. In Svart-Hvít Ský á Himni, the guitar is played traditionally and the work written entirely in standard notation (), but the instrument is processed to such a degree that it becomes unrecognisable as a guitar. The audio effects include the intricate interaction of feedback delays and polyrhythmic delays, distortion feedback, filter and wavetable distortion, pitch shift, automated panning, multiple reverbs and a rhythmic envelope generator. The latter utilises a step sequencer to create rhythmic patterns from sound disappearing from the texture – essentially rhythmicised silence – and is one of the most aurally prominent elements in the piece. The parameters of the individual effects are fully automated, which transform over the course of the work and are directly responsible for creating its dramatic trajectory. A counter on the Max/MSP patch allows the performer to line up specific moments in the score with the constantly changing effects, ensuring that the live performance and the patch's automation remain in sync ().

4.2.2. Visual elements

Svart-Hvít Ský á Himni features a more complex relationship between sound and vision than Akrasia, relying on a combination of parametric mapping and randomised video effects which to some degree delineate their temporal trajectories. The visuals, controlled by a second Max/MSP/Jitter patch that reacts to the sound of the processed guitar via an interface, are based around manipulations of a short 30-second stock footage clip of moving cloud formations.Footnote25 The clip is looped with the start and end points randomised, the colour altered to black and white, and the colour matrix inverted. The amount of inversion is the only visual element subject to parameter mapping, and like Akrasia, it is tied to input amplitude. When there is no sound, the screen is black; at the loudest points the screen is white; and in the middle the swirling ominous dark grey cloud formations emerge against a black backdrop (). The distinct pulsating rhythmic patterns which result from the step sequencer interact with the colour inversion, making the visuals pulse and strobe in sync with the audio, and thus doubling the music's surface-level temporal structure.

Figure 11. Video still of the stock footage after manipulation via Max/MSP/Jitter in Svart-Hvít Ský á Himni.

After the climax of the work,Footnote26 the consistent transcoding of colour matrix inversion to input amplitude ceases, and every element of the visuals proceeds independently. However, this change is itself a kind of synchretic temporal alignment: after reaching peak intensity, the music turns to a relaxed, meandering lyrical line which gradually fades out to silence and brings the work to a gentle close. This is paralleled separately in the visuals by abandoning the unsettling volume dependant strobe effect in favour of gracefully swirling, calm white clouds.

All the other visual elements are either preprogrammed or randomised, unfolding autonomously of any musical events. Throughout the work, the video spins and swirls using controlled randomisation before being processed with a kind of video ‘reverb’, lending a hazy, washy quality to the final result. While these elements have no discernible temporal alignment with any sonic events, neither do they disrupt them. Instead, the murky quality of the visuals matches and reinforces the character of the heavily processed, blurry reverberant sound, resulting in a high degree of audiovisual cohesion for the viewer-listener.

4.2.3. Summary

With its consistent and immediately recognisable parameter mapping between volume and colour inversion, Svart-Hvít Ský á Himni is a synthetic structure leaning towards the music translation end of the continuum. While the visuals have elements which unfold independently from the audio, the overall effect is one that complements and reinforces both the character and large-scale temporal structure of the music. Unlike Akrasia, a pure music translation in which the visuals simply double musical events, the approach taken in Svart-Hvít Ský á Himni creates a much more complex viewer-listener experience in which sound and vision work together to form a cohesive audiovisual structure from a combination of distinct temporal informations communicated on sonic and visual channels.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that temporal synchronisation can be useful as a taxonomic tool to provide a concrete starting point from which to understand the interaction of sound and vision, but also reveals its limitations – what makes a cohesive, compelling audiovisual work is not so straightforward. The viewer-listener experience arises from the complex interaction between elements which are readily recognisable – such as gestural synchronicity – but also intuitive psychological responses to metaphorical and contextual links which are not as easily quantifiable. The bulk of the limited repertoire for solo electric guitar and visuals, however, relies heavily on those intuitive responses to create cohesion, featuring limited temporal alignment between sound and vision, and thus falling on the mutual disturbance/intuitive complementarity end of the temporal-gestural continuum.

The new works by Arul, and to a lesser extent Björnsson, diverge from this trend, featuring an extremely high degree of temporal synchronisation through consistent and unambiguous parameter mapping. My intention, however, is not to make value judgements nor suggest any particular path forward for future audiovisual explorations. Indeed, the survey of existing repertoire demonstrates that artistically cohesive results can be achieved through wildly disparate compositional approaches. It is entirely by chance that both Akrasia and Svart-Hvít Ský á Himni utilised procedures that situate them on the music translation end of temporal-gestural spectrum, but their outlier status reveals that this is an area in the solo electric guitar repertoire that is yet to be thoroughly explored. It is my hope that these works will serve as an invitation for future composers and performers to consider the possibilities offered by this niche genre, and this article provides an aid to understanding and theorising such work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jonathan Fitzgerald

Jonathan Fitzgerald is a multi-award winning classical guitarist and Chair of Strings & Guitar at the University of Western Australia's Conservatorium of Music. Fitzgerald's artistic interests are diverse, ranging from traditional classical guitar repertoire to experimental compositions for electric guitar, with a keen interest in commissioning new works from Australian composers. Past projects include a residency at the National Trust of Western Australia, funded by a major grant from the Department of Culture and the Arts to develop a site-specific work at the historic East Perth Cemeteries. Entitled Sound from the Ground, the project won the Museums and Galleries National Award for Interpretation, Learning & Audience Engagement, and was a finalist for the WA State Heritage Award. More recently, Fitzgerald undertook Electroluminescence, a commissioning project which culminated in an immersive multimedia concert of new works for electric guitar, electronics and visual projections. An in-demand performer hailed as ‘a virtuosic talent in the guitar world’ (X-Press Magazine), he has presented concerts and lectures across the United States, Australia and Europe. Fitzgerald received his formal education in the United States, earning Bachelor and Master of Music degrees from the Cleveland Institute of Music, and a doctorate from the Eastman School of Music.

Notes

1 ‘Art music’ is a contentious term. In the context of this discussion, it refers to modern music in the western ‘classical’ tradition and its many subgenres such as minimalism, new complexity, noise music, etc.

2 Between 1950 and 2011, the number of art music compositions for electric guitar increased from 28 to 4,670, with the most rapid growth occurring after 1990 (Banks Citation2013, 2). In the last 10 years, that figure has nearly doubled – at present, there are almost 8,000 works for the instrument.

3 Ronald Pellegrino argues that ‘synergy’, the idea that whole is greater than the combination of its constituent parts, is ‘fundamental to the nature of complex interactive dynamic sound and light systems and their resulting forms’ (Citation1983, 208).

4 There is no straightforward way to comprehensively identify all audiovisual works in the Sheer Pluck Database. Numerous search terms were utilised to capture as many audiovisual works as possible, with results collated and crosschecked to identify and remove duplicates. These figures are accurate at the time of writing, but will immediately become outdated as new works are continually added to the database.

5 For individual works that form part of a larger set (for example Tim Brady's My 20th Century), I have counted the complete set as a single work.

6 See, for example, Chion Citation1994; Coulter Citation2010; Evans Citation2005; Hill Citation2013; Knight-Hill Citation2020; Watkins Citation2018.

7 Kandinsky claimed to be a synaesthete. His paintings often related colour and sound, inferred a temporal element, and drew on the language of music in their titles, such as Fuga (1914) (Cooke Citation2010, 198).

8 Among others, John Coulter proposes a classification system which categorises works into four main audiovisual ‘media pairs’, determined by whether the sound and vision are abstract or representational (Citation2010, 27); Andrew Hill defines four subcategories of audiovisual works distinguished by the compositional approach and artistic intention (Citation2013, 6); Myriam Boucher and Jean Piché adapt ideas from film theory to delineate works based around concepts of synchresis (the temporal synchronicity of sonic and visual events) and diegesis (the context, or ‘space and universe’ created by the work) (Citation2020, 14).

9 I use the terms ‘temporal integration’, ‘gestural integration’, ‘gestural synchronisation’, ‘temporal synchronisation’ and ‘temporal alignment’ variously to refer to the temporal paralleling of sonic events with visual events (or vice-versa). These events occur most often, but not always, on a moment-to-moment timescale. While a viewer-listener's perception of synchronisation between sound and vision can be subjective and influenced by many factors, my use of these different terms is not intended to distinguish those factors.

10 While Fuxjäger's categories deal primarily with the non-representational, abstract moving images associated with traditional visual music, his taxonomy still proves valuable in examining works that employ both representational and non-representational visuals.

11 Jack Ox and Cindy Keefer (Citation2008) similarly describes works with a 1:1 audiovisual mapping, in which ‘what you see is also what you hear’, as ‘direct translations’.

12 ‘Synchresis’ is Chion's own term, derived from a combination of the words ‘synchronism’ and ‘synthesis’.

13 The work can be viewed at https://youtu.be/uujWVWxxBd0, Neal (Citation2013a).

14 A ‘pure’ music translation is, according to Fuxjäger, a composition in which all musical events are paralleled with visual events, and the parameter-mapping remains consistent throughout the work (Fuxjäger Citation2012, 122).

15 The composer has graciously given me access to the full performance video of La escritura del dios, which is not publicly available, for this study. Selected excerpts from the work can be viewed at https://vimeo.com/20521063, Perini (Citation2010a).

16 Perini intends that this represents the part of the story in which the priest Tzinacán's prison cell is slowly filling with sand (Citation2010c).

17 Nico Couck's performance of degradative interference: wipe down equipment after use can be viewed at https://youtu.be/URyrT5Ca-80

18 It should be noted that the visual component's gradual transformation over the course of the work, lacking any noteworthy visual events to represent in the music, is certainly a critical factor in avoiding mutual disturbance between the two media.

19 MiR, performed by Thomas Kjekstad, can be viewed at https://youtu.be/B_FoDLKT6SM

20 Light Circle, composed by Manuel Rodríguez Valenzuela with video by Yeni Harkányi, can be viewed at https://youtu.be/_r2YI2Naz7k

21 Emilio Guim's Lies the Snake can be viewed at http://youtu.be/b4nu1mbNuV8

22 Akrasia and Svart-Hvít Ský á Himni were premiered on 19 January 2022, alongside four other works for electric guitar and visual projections, on a concert entitled ‘Electroluminescence’ presented by Tura New Music as part of the 2022 Fringe World Festival in Perth, Western Australia.

23 Max/MSP (Max Signal Processing)/Jitter is a powerful computer environment and graphical programming language that facilitates complex real-time audio and video manipulation. Max/MSP processes audio, and Jitter processes video.

24 The author's own performance of Akrasia can be viewed https://youtu.be/wu8SsbsxEOQ

25 The public domain stock clip was sourced from http://www.pexels.com/video/footage-of-cloud-formation-855441/

26 Svart-Hvít Ský á Himni begins building to a climax at around 5:10 in the author's own performance of the work, which can be viewed at https://youtu.be/-T09OC4xRf8

References

- Arul, V. 2021a. Akrasia [Audiovisual Composition] Youtube. https://youtu.be/wu8SsbsxEOQ.

- Arul, V. 2021b. Akrasia [Guitar Score]. Unpublished.

- Banks, Z. 2013. . "The Electric Guitar in Contemporary Art Music." PhD thesis. University of Sydney. Sydney eScholarship Repository. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/11805.

- Beglarian, E. 2001a. Until it Blazes [Audiovisual Composition]. Youtube. https://youtu.be/Jr1cAfyfFG8.

- Beglarian, E. 2001b. Until it Blazes [Musical Score]. New York: EVBD Music, score 1097.2.

- Björnsson, G. 2020a. Svart-Hvít Ský á Himni [Audiovisual Composition]. Youtube. https://youtu.be/-T09OC4xRf8.

- Björnsson, G. 2020b. Svart-Hvít Ský á Himni [Guitar Score]. Unpublished. https://www.gullibjornsson.org/product-page/svart-hv%C3%ADt-ský-á-himni.

- Boucher, M., and J. Piché. 2020. “Sound/Image Relations in Videomusic: A Typological Proposition.” In Sound & Image: Aesthetics and Practices, edited by A. Knight-Hill, 13–29. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429295102.

- Brustad, K. 2006. MiR [Audiovisual Composition]. Youtube. https://youtu.be/B_FoDLKT6SM.

- Chion, M. 1994. Audio-Vision: Sound On Screen. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Cooke, G. 2010. “Start Making Sense: Live Audio-Visual Media Performance.” International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media 6 (2): 193–208. doi:10.1386/padm.6.2.193_1.

- Coulter, J. 2010. “Electroacoustic Music with Moving Images: The Art of Media Pairing.” Organised Sound 15 (1): 26–34. doi:10.1017/S1355771809990239.

- Evans, B. 2005. “Foundations of a Visual Music.” Computer Music Journal 29 (4): 11–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3681478. doi:10.1162/014892605775179955

- Fuxjäger, A. 2012. “Translation, Emphasis, Synthesis, Disturbance: On the Function of Music in Visual Music.” Organised Sound 17 (2): 120–127. doi:10.1017/S1355771812000040.

- Garro, D. 2005. "A Glow on Pythagora’s Curtain: A Composer’s Perspective on Electroacoustic Music with Video." Proceedings of the 2005 Electroacoustic Music Studies Network Conference - Sound in Multimedia Contexts. Montreal: EMSICS, 1–18.

- Garro, D. 2012. “From Sonic Art to Visual Music: Divergences, Convergences, Intersections.” Organised Sound 17 (2): 103–113. doi:10.1017/S1355771812000027.

- Guim, E. 2018. Lies the Snake [Audiovisual Composition]. Youtube. http://youtu.be/b4nu1mbNuV8.

- Hill, A. 2013. "Interpreting Electroacoustic Audio-visual Music, Volume One." PhD thesis, De Montfort University. De Montfort Open Research Archive. https://dora.dmu.ac.uk/handle/2086/9898.

- Knight-Hill, Andrew 2020. “Audiovisual Spaces: Spatiality, Experience and Potentiality in Audiovisual Composition.” In Sound & Image: Aesthetics and Practices. Sound Design, edited by Knight-Hill, Andrew. London, UK: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429295102-4.

- Lund, C. 2016. No More Umbrellas Or How to Talk About Visual Music Without Having your Fingers Burnt [Keynote]. Sound/Image Conference 2016, University of Greenwich.

- Neal, A. 2013a. cords [Audiovisual Composition]. Youtube. https://youtu.be/uujWVWxxBd0.

- Neal, A. 2013b. cords [Guitar Score]. https://adamscottneal.com/product/cords-electric-guitar-computer.

- Ox, J., and C. Keefer. 2008. On Curating Recent Digital Abstract Visual Music. Center for Visual Music. www.centerforvisualmusic.org/Ox_Keefer_VM.htm.

- Peacock, K. 1988. “Instruments to Perform Color-Music: Two Centuries of Technological Experimentation.” Leonardo 21 (4): 397–406. doi:10.2307/1578702

- Pellegrino, R. 1983. The Electronic Arts of Sounds and Light. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold International.

- Perini, A. 2010a. La escritura del dios [Audiovisual Composition]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/20521063.

- Perini, A. 2010b. La escritura del dios [Guitar Score]. Unpublished.

- Perini, A. 2010c. "Realizzazione di opere musicals and multimedia dai testi di Jorge Luis Borges." Masters thesis, Conservatorio di Musica di Como.

- Tramte, D. 2014. degradative interference: wipe down equipment after use [Audiovisual Composition]. Youtube. https://youtu.be/URyrT5Ca-80.

- Valenzuela, M. 2009. Light Circle [Audiovisual Composition]. Youtube. https://youtu.be/r2YI2Naz7k.

- Watkins, J. 2018. “Composing Visual Music: Visual Music Practice at the Intersection of Technology, Audio-Visual Rhythms and Human Traces.” Body, Space & Technology 17 (1): 51–75. https://doi.org/10.16995/bst.296.