ABSTRACT

This paper discusses home as a stage and its intersection with new technologies through an autoethnographic recollection and analysis of practice research, whose processes and methods are entangled with both digital and domestic environments on the virtual stage of Flanker Origami, a live online performance on Zoom devised by Organic Theatre. Premiered as part of the digital programme of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe 2021, the performance is discussed as a case study of shifts in practice driven by the COVID19 pandemic in the real home of the two devisers/performers. This enquiry introduces and discusses home-specific performance as a practice research methodology, which exploits the deep nexus between home, identity and gender in the digital staging of the domestic in Flanker Origami. Analysing online training, hybrid scenography and digital performativity specific to the performers’ home, this practice-based investigation evaluates the benefits and challenges of developing online theatre in a situation of social confinement. The conclusion evidences that home as a digital stage was instrumental in reconfiguring notions of self and authenticity in performance processes driven by the pandemic, while creatively reframing the familiar and the domestic to expand and innovate artistic practice at a critical point of social and personal vulnerability.

Introduction

In The Poetics of Space Gaston Bachelard (Citation1964, xxxvi) states that ‘on whatever theoretical horizon we examine it, the house image would appear to have become the topography of our intimate being’. Indeed the notion of home which Michel de Certeau, Giard, and Mayol (Citation1998, 145) defines as ‘the territory […] to which one longs to “withdraw” […] one's own place, which, by definition, cannot be the place of others’ has been widely investigated in performance making. As Gene Bawden (Citation2011) notes ‘this narrative power of “home” is well exploited in literature and film, but equally we “write” and “read” our own domestic stage sets’. According to Scott Cummings (Citation2013) performing at home obscures ‘the boundaries between dramatic event and daily life’, while exploring home as a set and a site for performance upsets the conventional separation between private and public spheres. This paper discusses the entanglement between creative processes and home environments during the shift of devising practice from studio spaces onto digital platforms in my house during the COVID19 pandemic. Moreover, it draws upon a long history and legacy of performance situated in domestic spaces – both in presence and on digital – linked to feminist and queer practices. These have sought to re-frame the notion of womanhood in relation to domesticity, adapting private home spaces as performance stages, both as physical sets and in the realm of digital and networked performance, where the thresholds between liveness and virtuality in home settings have been widely explored. In reference to my own practice, this article discusses Flanker Origami by Organic Theatre, a digital, home-specific performance I co-created with actor, director and life partner John Dean, to which I will also refer as a case study within a longitudinal practice research project with the same name.

Supported by Queen Margaret University in Edinburgh, this practice-based investigation started in 2020, at the onset of the first UK lockdown, with a focus on digital liveness, and on the possibility of building its foundations through digital performance training and making at home. As a practitioner, I have been performing and creating in and for a variety of sites for over three decades. These have ranged from theatres, ad-hoc festival venues, pop-up shops, museums, village halls, art galleries, barns and streets. I am therefore accustomed to being sensitive and specific to a given site, as well as flexible enough to re-locate my practice within different environments. Moreover, growing up with artist parents, both Dean and I have first-hand knowledge of how living spaces can be transformed by artistic intervention. In my case, as a daughter of an Italian theatre family, during my teenage years I was shaped in my notion of home by the experience of working and living in the theatre space my parents Pina Cipriani and Franco Nico founded in 1972 in Naples. The theatre acted as my home for a period of time, as well as the place I had my very first apprenticeship as a performance maker. During the pandemic, the embodied memory of a theatre building doubling as a family dwelling gave me the courage to playfully subvert my living space and be creative with/in it. I recognise that recalling and re-using the memorable experience of living in my family theatre to engender performance in my current home, I am still ‘inhabiting that particular house, and all the other houses are but variations on a fundamental theme. The word habit is too worn a word to express this passionate liaison of our bodies, which do not forget, with an unforgettable house’ (Bachelard Citation1964, 15).

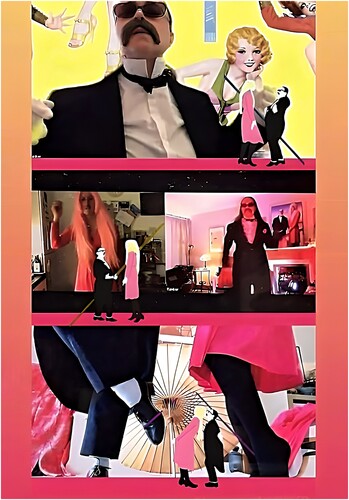

For Dean too, growing up in a fine art gallery-style home, doubling as a working studio for his visual artist parents, it was straightforward to imagine our shared domestic space as a temporary rehearsal room. The most evident limitation was the compact size of our house – a terraced two-storey 1990′s building with a small back garden – and the friction of the everyday with the worlds conjured by our theatrical imagination. As Anne Massey and Penny Sparke (Citation2013, 3) point out ‘there is a very close, two-way relationship […] between people’s lives and the spaces they have inhabited’. They argue that ‘central to that relationship is “identity”, a social and psychological concept, the formation of which is closely intertwined with the environments – interior spaces (especially those of the “home”) in particular – in which people live their lives’(Citation2013, 3). In my definition of home-specific performance, the deep nexus between home and identity is therefore a predominant line of autoethnographic enquiry, given that ‘the house images move in both directions: they are in us as much as we are in them’ (Bachelard Citation1964, xxxvii). Adapting pre-pandemic creative processes to digital exploration at home, the first step was therefore to destabilise the relationship between our identity and our home environment. Re-using performance material Dean and I were developing pre-Covid, this was achieved by altering our gendered identities and socially constructed heteronomy, as we reworked two characters inspired by Renée and Renato, a British-Italian female/male vocal duo, known for their 1982 pop hit ‘Save Your Love’. In embodying these performance personas through cross-dressing, we were exploring our roots as a bi-cultural artist couple – one European and one British – ironically and metaphorically trying to ‘save our love’ at the time of the divisive Brexit process. With digital experimentation on the Zoom platform during the pandemic, the singing couple transformed into Flanker and Origami, two alter egos trapped at home in a dystopian online connection. Between May and August 2021, the alter egos developed into the protagonists of Flanker Origami, which premiered live online at the first hybrid programme of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in August 2021 ().

Figure 1. Flanker Origami, Organic Theatre, August 2021. Social media advert for the Edinburgh Festival Fringe 2021. Designed by Ariane Oiticica. © 2023 Organic Theatre.

In considering home environments as alternatively supporting or hindering the performers’ dramaturgy, my analysis of Flanker Origami as a home-specific performance evaluates that ‘home embodies powerful and emotive qualities’ (Bawden Citation2011). I also seek to acknowledge how interior spaces influence our lives (Massey and Sparke Citation2013), whilst taking into account the strongly gendered dimension of domestic interiors (McKellar and Sparke Citation2004), and questioning notions of authenticity in a process which involves re-writing personal memories and identities. Throughout this enquiry, the house as a digital staging was assessed as an act of resistance to the pandemic standstill, and of creative resilience towards the emotional and cognitive impact of social restrictions. Practical research methodologies highlighted an underlying health discourse related to the need of counteracting the repetitive nature of lockdown routines. As neuroscientist Dean Burnett (Citation2021) explains:

The pandemic has caused a lot of people to be a lot more stressed for longer periods […] and the usual avenue for reducing stress in healthier ways, like going out, travelling or experiencing new things, or just getting out and about or seeing friends and family […] have been blocked. […] It’s like a double whammy of increased stress for everyone.

Flanker Origami background

Flanker Origami was a glitch name which appeared on my iPhone while transcribing audio-feedback of a research workshop on Zoom. As a product of technological agency, these two accidental words, once adopted as a performance title, did not hold any specific meaning and so contained the potential of open-ended creative directions.

Livestreaming on a Zoom webinar, Flanker Origami enacted the strains of lockdown intimacy between Flanker (my male alter ego) and Origami (Dean’s female performance persona), an artistic, cross-dressed couple confined at home due to a global health crisis, in search of social bonding through the digital medium. Involving digital spectators on the webinar, through an absurdist and ritualistic sequence of wellbeing routines, Flanker and Origami socially groomed each other and their online audience, to counteract the isolation and the anxiety of home confinement. Their playfulness and complicity progressively descended into an online manipulative home-game, amplifying a power dynamic ‘which exploits gender inequality, hints at domestic abuse and reveals the fragility of their day-to-day existence caused by lack of social contact’ (Mastrominico Citation2023). Flanker Origami built on mask work and intermedial practice in Organic Theatre’s previous work, the use of autobiographical material in devising, as well as experimenting with camera work in pre-pandemic training and rehearsals. In an interview released during the 2021 Edinburgh Festival Fringe, for the first time in the process I defined the performance as ‘a home-specific show inviting our audiences to gaze, imagine and be voyeurs of personal spaces in a real house’ (Mastrominico and Dean Citation2021) ().

Figure 2. Flanker Origami, Organic Theatre. June 2022. Bianca Mastrominico as Flanker in the kitchen, with empty living room. Screenshot from Zoom recording. © 2023 Organic Theatre.

I was conscious that beyond the unprecedented circumstances which provoked my shifts in practice, I was creatively tapping into historical and experimental legacies of performance at home, to which I will now bring my focus.

Domestic stages in feminist and queer performance

Symbolically connected with the female body, home as a stage has been constantly reinvented. In literary fiction and play-texts as well as devising and digital performance practice, staging the house has often become, as Ann M. Shanahan (Citation2013, 129) notes, ‘the metaphor [which] advocates for female autonomy within domestic space’, marking the notion of home ‘as a repressive container of female creativity’. Historically, feminist and queer performance has re-addressed the patriarchal discourse of house as the golden cage of the feminine, staging home as a place where the authentic and contradictory experience of women’s bodies are included (136). Feminist and queer practitioners have engendered strategies to break free from the model of the house-as-a-set, exemplified in the works of playwrights such as Anton Chekhov and Henrik Ibsen, and which rests on ‘the traditional mimetic relationship of observer/observed’ (131), objectifying female characters. In the play Fefu and Her Friends (1977), inspired by her experience in a women’s group in the 1970s, playwright María Irene Fornés pushes the ‘boundaries of the realistic conceit to border and intersect with real life, loosening the gender biases of the fourth wall and linear structure’ (136). Set in the 1930s, the central character, a wealthy woman named Stephanie (Fefu) Beckmann invites a group of other women to her country house to discuss and prepare for an unspecified fundraising event related to education. Spectators become part of the action when, split into four groups, they move from different rooms of the house (the lawn, the study, the bedroom and the kitchen) to witness intimate exchanges, which reveal the backstories of each woman-character. In the site-specific performance Kitchen Show (Citation1991) made in collaboration with Polona Boloh Brown, live artist Bobby Baker made a choice of opening ‘her kitchen to the public to display and perform one dozen routine kitchen actions’ (https://www.dailylifeltd.co.uk/projects/kitchen-show-). The work invited audiences ‘to consider the lack of social transformation in women’s lives’ and to experience performance happening in a real, working kitchen. As Gay McAuley (Citation2005, 37) observes, ‘when the performance is occurring in a “real place” rather than a theatre, and the conventional markers are missing, the stakes are higher, and the risk is greater’. In cyberformance practice, pioneered by Helen Varley Jamieson since 2000, home is where cyberformers and their online audiences are most often situated and connect from through the Internet in real time. In their networked performance series make-shift (2010–2012) Paula Crutchlow and Jamieson (Citation2014, 2) dramatised and problematised ‘the private actions of our domestic lives […] in relation to ecological themes of plastic marine pollution’. Crutchlow and Jamieson, each located in one of ‘two ordinary houses (usually in different countries)’ worked collaboratively with proximal and online participants to ‘stage’ the event:

As a site responsive work, make-shift is reliant on its domestic settings to produce and anchor its meaning, relevance and resonance. Proximal participants in the houses take part in a two to three hour experience in someone's home, sharing food and discussion as well as contributing to the performance action itself. Online participants often tell us they are also in their own home. (4)

There is no (digital) place like home

As Jennifer Parker-Starbuck (Citation2011, 8) observes in her definition of Cyborg Theatre:

Like a laboratory, the theatre is a space for trying things out, for introducing old ideas anew […]. This positioning is more philosophic than pragmatic – it relies on the theatrical space itself as a site for people to go to, to leave their homes for.

In drawing comparisons with the experience of making Flanker Origami, to counteract the cage-like feeling of the Zoom ‘framed boxes’ mentioned by Sermon, Dean and I developed techniques of auto-framing, creating a live and dynamic cinematic montage between our two Zoom windows. We also struggled with the poverty of means highlighted by Liodaki and Velegrakis, and found it useful to evoke Jerzy Grotowski (Citation1969) and his notion of stripping the performance of ‘all that is not essential to it’, realising our own version of ‘poor (digital) theatre’. While the relation of Langgam Performance Troupe with domestic/public environments and their online/social media audience was filtered through the repetition of individually performed actions and tasks, in our devising process Dean and I focused on exploring our intersecting dramaturgies on two or more digital screens. Fandom and online intimacy conjured by comedians like Chowdhry on social media inspired us to display our house-set, while interacting with our spectators and exploring digital liveness through the chat box. Despite differences in digital format and spectatorship, performance which occurs within domestic environments is site-specific in the sense that, according to Mike Pearson and Michael Shanks (Citation2001, 23), ‘site-specific performances […] are inseparable from their sites, the only contexts within which they are intelligible’. Re-contextualised through performance making, sites become more than ‘just an interesting, and disinterested, backdrop’. However, the specificity of the home stage as a site is not just in that it is not a theatre space, rather it derives from the assemblage of personal objects and belongings through what Jennifer A. González defines as ‘autotopography’ (Citation1995, 134). This manifests as ‘a careful, visual arrangement of mementos and heirlooms […] a material memory landscape [which] forms a spatial representation of important relations, emotional ties, and past events’. In making and performing Flanker Origami in my Edinburgh house, I sought to retrieve memories of the theatre-house I once inhabited in Naples, recalling and re-making the daily actions I used to perform in a public space, which was also my home. Re-contextualising items belonging to my professional background, from costumes to instruments, artefacts and props, I became mindful that ‘the collection and arrangement of objects into a visible space creates a representative reconstruction of personal memory’ (144). Bachelard noted that ‘the house we were born in is more than an embodiment of home, it is also an embodiment of dreams’ (Citation1964, 15). Under lockdown in Scotland, I dreamt that my house was the theatre that once had been my home. The function of my present home was therefore subverted, while boundaries between life and fiction, art and reality, past and present were destabilised. In hindsight, I decided to coin the term ‘home-specific performance’ to underline that making the house into a stage raised ‘the question of the biographical role of property’ (González Citation1995, 134). While dealing with personal stories and memories, the staging of the domestic demanded home to be read and experienced as ‘a visible and tactile map of the subjectivity’.

Digital inter-play and collaborative training methods

Prior to the pandemic, Dean and I had been devising with autobiographical materials, looking at the decade of our childhoods and relating current psychosomatic disorders to our upbringing. We instigated explorations through costuming and transformation, examining our gendered identities as embodiments of patriarchy. During the pandemic, the approach focussed on adapting and reworking these materials for the digital medium, reconfiguring our processes within the house as a virtual stage. Experimentation on the Zoom video-call application was underpinned by the practice of ‘working on […] affinity, rather than identifying ourselves with our performance personas, interpreting a role, or investing in becoming a character’ (Mastrominico and Dean Citation2020). This process was led by specific enquiries related to how body and domestic space entangle with connection and affect through the technology. In working digitally at home, my concern was ‘how to retain liveness and keep collaborative processes alive in a way that would contain the essence of the creative conditions I would normally experience in person’ (Mastrominico Citation2022b, 269).

Between August and October 2020, the shifts in practice evolved into six weekly online training sessions, set up as exploratory meetings between three performers connecting from their own houses via Zoom. Forming a small digital ensemble, London-based performer Madeleine Worrall, Dean, and myself explored how to creatively connect ‘through responsive interaction, while also testing the limits of the virtual space’ (Mastrominico and Dean Citation2020). The aim was to sustain our practice at home, investigating online ensemble play within the technical constraints – or new opportunities – of working through digital platforms. During these sessions we experimented with ‘bypassing physical timidity in front of the screen, also searching for ways to (re)create physical connectivity between participants’ (Mastrominico Citation2022b, 270). Invented exercises such as that of blowing each other over on screen were conceived as ‘simple action-reaction tasks which worked to trick participants’ brains into believing that there was no screen barrier in front of them’. Analysing the Zoom recordings of the sessions, I observed that:

In the continuum of our virtual process, we found ourselves reframing our relations through a practical methodology which I define as an ecology of becoming’ […] in that as performers we were fluidly accepting the changes and the impact of the hybrid working conditions on us. (Mastrominico Citation2021)

Almost a studio space created in this little bubble that links us. It brings a little bit of play into the room. A studio-frame. Magic box, childlike. In this unexplored space you can go without a main plan. Levelling the abilities and the experiences. Affect comes through the chat as well. (Stephanie Arsoska and Bianca Mastrominico, February 18, 2021, Zoom meeting)

Making performance while in lockdown at home for transmission via a video conference service brings a range of practical and conceptual challenges […] ‘Costumes’ must come from the performers’ own clothes, ‘scenery’ from their domestic environment, and lighting from combinations of interior daylight and desk-lamps. It is not that such poverty of means is inherently negative in its impact […] rather, a new process must be developed.

In the context of staging Flanker Origami, ‘a new process’ meant that in overwriting the domestic and the everyday, Dean and I needed to reconfigure the home-space as a ‘place for gesture’, engendering a praxis for ‘a conscious manipulation of the existing that is continuously transformed as its authenticity is disintegrated’ (Postiglione and Lupo Citation2007, 12). In so doing, we were re-building our sense of home as an extra-daily space, which toyed with our identities, while transforming and heightening the everyday ().

When the ordinary becomes extraordinary

In analysing and evaluating how home can become a reliable performance environment, it is useful to firstly observe how the brain perceives it as the place where we can be stress-free, and perform actions which are biologically significant. As Burnett (Citation2018) explains in his pre-pandemic writings about the influence of home environments on our brain, we are normally wired to find happiness in the notion and feeling of going, arriving and being at home. We see home as the place which allows us to release the threat-detection system, which according to Burnett is ‘incredibly useful when exploring new, unfamiliar locations’ (45) but not necessary when we are safely settled in our shelter. However, what Burnett also highlights is that ‘when we are at home, we can more easily focus on anything out of the ordinary […] our brain is used to ignoring the environment around us, so anything that differs from that gets our attention much faster’ (46). During lockdowns through the collective digital exposure of our private lives to family, friends, colleagues or strangers, we were already forced to un-relax, not being able to ignore where we positioned ourselves in the house for a video call, and how we would frame our personal spaces for others to watch. In conjuring home-specific performance, the sustained alertness towards extra-ordinary events in the midst of our habitat made our brain diverge from what it would normally perceive as a regulated, safe and calm environment. While acting out of the ordinary in our own house became a habitual behaviour, the exceptionality of that behaviour within the domestic environment was sensed to be less and less threatening and abnormal, as the brain adapted to it as the new familiar. Responding to an enquiry by a digital spectator about performing at home, I was compelled to validate ‘the danger [of becoming] affectionate to that world [of performance], which creates a public space in our private space, and the risk of exposing it continuously on digital, which also makes our personal space blurred and ephemeral’ (Mastrominico Citation2022c). I also noted that for a long time after each performance ‘we kept all the things there, we never did a get-out, and we live around everything else that is still standing in the house in a very uncomfortable way. We do not know if this is a house, a theatre or a film set’. Therefore, using our living space to engender digital performance generated new thresholds between domestic needs and creative intentions. As Dean (Citation2021) explained during a post-show Q&A on Zoom:

It is both very odd and very familiar, in that you feel at home because you are, but the everyday tends to creep in and get in the way, and it can get very complicated, for example, suddenly realising that you need to do those dishes now and you cannot delay, because the show must happen in that sink or next to it.

Figure 4. Flanker Origami, Organic Theatre, June 2021. The Flanker Origami teacup. Photo by Bianca Mastrominico. © 2023 Organic Theatre.

Despite being aware that I was seeing a family’s house on screen, I don’t think I fully realised that it was actually a home until I saw it in person. The knowledge that the backdrop of Flanker Origami’s most dramatic moment was actually a living room, where a family well and truly lives, only fully came to me once I was physically there. My digital presence […] sometimes even made me forget the fact that I was in my own home while following the cues, and yet the physical absence actually proved to be the winning force in my brain. (WhatsApp message to author, 14 February 2023)

Queering the living room

According to Sparke (in McKellar and Sparke Citation2004, 2) ‘the relationship between people and their interiors is not a static one: the constantly transforming nature of the domestic interior is such that neither it, nor the identities it represents, can ever be stable’. While the house in lockdown became subjected to constant reshuffling of its interiors, a sense of instability appropriated how Dean and I perceived our identity as a couple. The work on Origami, who rejects toxic masculinity, and Flanker, who embodies it, gave Dean and I the chance to reflect on the potential strain of our relationship, and on home-related gender aggression, which were surfacing in many (apparently) stable partnerships during the pandemic. In home confinement the social pressure to adhere to gendered dress codes diminished considerably, as without a social life it was left to our arbitrary decision what to wear daily (and why) in the house.

Embarking in a process of gender reversal to embody the vigorous and soft energies of our male/female alter egos, according to Judith Butler (Citation1990, 10), as performers and as a couple, Dean and I were exposing that:

When the constructed status of gender is theorized as radically independent of sex, gender itself becomes a free-floating artifice, with the consequence that man and masculine might just as easily signify a female body as a male one, and woman and feminine a male body as easily as a female one.

Performing home as a digital stage

Living in lockdown resulted in a cluttered domestic environment, therefore re-creating the space as a digital stage was an opportunity to re-claim it from the pandemic chaos and restore a sense of agency in our daily lives. In altering the house for the digital performance, domestic spaces were reshaped by a constant reshuffling of objects and technical equipment around the living areas. As Dean reflected ‘the domestic overlaps with creative work really make you think how you live, and bring a good discipline from the work into your daily life’ (Citation2021). A detailed mise-en-scène was staged in areas of the house which would be framed on Zoom. For example, the staircase leading from the living room to the bedrooms was laid out with stiletto heels, well-worn boots and golden tinsel. This installation would be captured by the camera eye when Dean as Origami would climb the stairs with the iPad pointing downwards at his feet. In moving from the upstairs bedroom onto the landing, my auto-framing would linger on two costumes and carnival masks hanging on the wall, as well as on the glittery tinsel backdrops mounted on curtains and doors. Through the reverberation of coloured lights, and a disco ball rotating in the living room, the space felt ready to host a themed costume party. Each room of the house where we performed had its specific ambience, with a mix of artificial and natural light, according to the relevant scene. There was no obvious place for props to be temporarily stored, so physical scores would need to incorporate the actions of making them available during the performance. What the digital audience would not see in the frame was this continuous adjustment of items around the home space, to reveal or hide them at the appropriate moment. Outside noises were not an immediate issue, though our approach was to integrate any accident, making the digital spectators as complicit as possible. Although the performance was highly scored, the need of remaining flexible and open to real life occurrences raised the level of alertness at which Dean, Menozzi and I were already operating, making us ready to improvise around unexpected situations in and out of the house.

Hybrid scenography and digital performativity

Being in charge of re-arranging home interiors for the performance, I merged directorial decisions with scenographer and production manager tasks to achieve a specific Stimmung, a term coined by Italian scholar Mario Praz. This – as Patrizio Martinelli writes – summarises the ‘overlapping and accordance of space, environment, atmosphere, objects and furnishing, and the evocative representation of the character of the inhabitant in that specific space’ (Citation2020). However, the set was never fixed, instead spaces needed to be unfixed each time we performed and objects re-assembled in mini-installations, which included artefacts, personal items, costumes on a rail, musical instruments, and props. Moreover, while physically leading the iPad camera through the house, Dean and I conjured a hybrid scenography using digital backgrounds as a virtual set (), in counterpoint and/or as dramaturgical ruptures to the ‘real’ space, which as it was filmed, was concurrently operating as a virtual set. The house itself performed as a multi-layered location – a set, a stage and a digital environment. While manipulating screen technology to influence the digital spectators’ perception of our daily spaces, domestic items were framed as ready-mades, such as the boiling kettle juxtaposing with a dance routine on the adjacent Zoom window ().

Figure 5. Flanker Origami, Organic Theatre. June 2022. Bianca Mastrominico as Flanker. Screenshot from Zoom recording. © 2023 Organic Theatre.

Figure 6. Flanker Origami, Organic Theatre, June 2022. Bianca Mastrominico and John Dean as Flanker and Origami in the ‘Dance of the Seven Moves’. Performed live online at Transit 10th Festival – The Splendour of the Ages, Holstebro, Denmark. Screenshot from Zoom recording. © 2023 Organic Theatre.

The physical size of our living room conditioned our body movements, and dictated the type of physicality that was achievable when dancing in a restricted space. Flanker and Origami’s steps bore evidence of those limitations in their quirky and tight choreography. In this case the confinement opened the possibility of tapping into unpredictable forms of doing and embodying through the digital. As Jamieson (Citation2022) noted in her Mysteryclass talk, which followed the livestreamed performance of Flanker Origami at the Transit 10th Festival – The Splendour of the Ages in Denmark, ‘I find this idea of limits actually very helpful […] pushing against those limits to the point that they start to break and you find new interesting things’. In the performance these material limitations dictated by lack of space generated a digital aesthetic where glitches and close-ups were employed creatively and abundantly, engendering an online intimacy conducive to what Susan Broadhurst (Citation2021) terms as ‘somatic hybridity’ in [the] use of technology to extend the physical and sensual body into the virtual’. As the Wi-Fi in outdoor spaces of the house was not always reliable, technical constrictions were playfully acknowledged and alternative solutions adopted, such as recording a scene in the back garden, to be used as an intermezzo between the two live parts of the performance (). The integration of 2D rotoscope animations by artist and illustrator Cristiana Messina broke with the continuous streaming of domestic spaces, presenting a hyper-reality of the performers in a pop-up world, which extended their fantasies beyond the house. The animated versions of Flanker and Origami pushed the alter egos towards fandom and a celebrity status, which allowed the strand of a witnessing world outside the house to be present in and affect the digital performance ().

Conclusion

Creating performance in-between domestic environments and digital technology has proved to be as rich as it is an edgy proposition. This practice research has clearly pointed towards the challenges of sustaining full and regular productions at home, as the digital performance squats inside domestic life, becoming mentally and physically demanding to develop. While social restrictions forced performers to be adaptable and become more resourceful in every aspect of their pandemic life, home-specific performance required a flexible mind-set to counter an ever-changing and unpredictable pandemic timeline. Moreover, lack of external support and working in isolation with the tensions of a health threat on the doorstep – combined with the explorative nature of the digital adaptations – doubled the effort and energy expenditure needed to deal with the devising stages and production requirements. Flanker Origami was conceived to connect with digital spectators in their own houses. As people started to move and travel again, the work was experienced from different locations other than homes – a variety of devices and viewing conditions enabled a different kind of presence, participation and reading of the performance. As Burnett points out, home is not just ‘the actual physical structure we inhabit’ and that ‘the human sense of home […] doesn’t end at the four walls we reside in’ (Citation2018, 47). When Flanker and Origami could eventually leave the house as well, to perform hybrid and in person, going out became a symbolic act of marking our territory and ‘home-range’, extending the notion of home to the streets, the city and potentially the whole world. The digital staging of the domestic democratised processes of spectatorship through building a social media community, which followed the various iterations of Flanker Origami online. Performing on Zoom from/at home allowed Organic Theatre to connect globally with digital networks and communities, as well as initiate collaborations and exchanges with a low carbon footprint. If the sociomateriality surrounding the making of Flanker Origami exposed and transgressed boundaries between private/public and personal/shared, this enquiry has evidenced that exploring home as a digital stage was instrumental in reframing gender, identity and authenticity in performance processes driven by the pandemic, while expanding and innovating artistic practice at a critical point of social and personal vulnerability. In a fertile dialogue with digital technologies, home was the shelter which nurtured the dream of a more intimate experience through hybrid spaces of the imagination.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the input from John Dean as co-researcher, co-deviser and performer of Flanker Origami. My thanks go to Organic Theatre’s collaborators that made the project possible: Ariane Oiticica, Cristiana Messina, Chiara Menozzi, Massimo Alì Mohammad and Francesco Dean. I also wish to express my gratitude to all performers and researchers who joined Digital HotSpot to develop digital training at/from home, whom I name in this article. I am indebted to my colleagues in the QMU Practice Research Cluster for their generous responses at various stages, to Dr Vlad Butucea for his continuous feedback on various iterations of the project, and I wish to acknowledge the ongoing support of the Centre for Communication, Cultural and Media Studies at Queen Margaret University in Edinburgh for my practice research. I am grateful to Elena Masoero for ongoing discussions on the house-as-theatre, and to Margaret Rose and Sal Cabras for their support and their kind invitation to perform and lead workshops for English Theatre Milan in 2021. I am very grateful for the ongoing exchange of practice and visions I continue to have with the creative team who conceived Bodies:on:Live – Magdalena:On:Line, the first online Magdalena Festival in 2021. Heartfelt thanks to the team behind Along the Edge Arts Festival – Fear Not! for hosting Organic Theatre in Hong Kong in 2022. A special thanks to Julia Varley for inviting Flanker Origami to Transit 10th Festival – The Splendour of the Ages for a hybrid performance in Holstebro, Denmark in 2022, where the core themes of this article emerged through a post-show discussion with the artists-spectators. Finally, to my neighbours, for their silent presence and support during lockdowns.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bianca Mastrominico

Bianca Mastrominico is a performance maker and a researcher. Since 2002 she has been co-artistic director of the performance laboratory Organic Theatre (www.organictheatre.co.uk). Bianca's practice centres on her artistic work with the company, and she has published her research in many international journals and edited collections. Bianca is Programme Leader for BA (Hons) Drama at Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, where she is also co-leading the Practice Research Cluster within the Centre for Communication, Cultural and Media Studies. She is active within the Magdalena Project network of women in contemporary theatre.

References

- Atkinson, Paul. 2017. “Amateur design: DIY as resistance”. Paper presented at the Design History Society Annual Conference, University of Oslo, Norway, September 6–9. https://shura.shu.ac.uk/16785/.

- Bachelard, Gaston. 1964. The Poetics of Space. New York, NY: Orion Press.

- Baker, Bobby. 1991. “Kitchen Show.” Daily Life Ltd. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.dailylifeltd.co.uk/projects/kitchen-show-.

- Bawden, Gene. 2011. “Home Theatre - Staging the Domestic Interior.” Double Dialogues 14, https://www.doubledialogues.com/article/home-theatre-staging-the-domestic-interior/.

- Bianchi, Victoria, Bianca Mastrominico, and Anthony Schrag. 2022. “Seminar Report: Not Fewer Resources, but Different: Creative Responses to Practice and Research During Covid-19.” Scottish Journal of Performance 7 (1): 115–128. doi:10.14439/sjop.2022.0701.08.

- Broadhurst, Susan. 2021. “Hybridity and Experimental Aesthetics in the Performances of Anne Imhof.” Body, Space & Technology 20 (1): 1–13. doi:10.16995/bst.358.

- Burnett, Dean. 2018. The Happy Brain. London: Guardian Faber.

- Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. London: Routledge.

- Chatzichristodoulou, Maria, Kevin Brown, Nick Hunt, Peter Kuling, and Toni Sant. 2022. “Covid-19: Theatre Goes Digital – Provocations.” International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media 18 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1080/14794713.2022.2040095.

- Crutchlow, Paula, and Helen Varley Jamieson. 2014. “make-shift.” Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies 10 (1): 2–12. http://liminalities.net/10-1/make-shift.pdf.

- Cruz, Jenny Logico, and Blonski Campos Cruz. 2022. “Thread/Warp.” Body, Space & Technology 21 (1): 1–9. doi:10.16995/bst.7969.

- Cummings, Scott T. 2013. María Irene Fornés. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Dean, John. 2021 “Flanker Origami Q&A.” Online speech on Zoom at along The Edge Arts Festival, Hong Kong, September 2, 2022.

- Dean Burnett. 2021. "What’s Been Going on with Our Brains During Lockdown? Neuroscientist Dr Dean Burnett on How to Make Sense of Mental Health Issues.” Published by Michael MacLennan. In Covid Matters, June 29, 2021. Podcast, 30:52. https://youtu.be/KDrwihOXLM4.

- de Certeau, Michel, Luc Giard, and Pierre Mayol. 1998. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Timothy J. Tomasik. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. De_Certeau_Giard_Mayol_The_Practice_of_Everyday_Life_Vol_2_Living_and_Cooking.pdf.

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. (original work published 1980).

- Gherardi, Silvia. 2017. “Sociomateriality in Posthuman Practice Theory.” In The Nexus of Practices: Connections, Constellations, and Practitioners, edited by S. Hui, E. Shove, and T. Schatzki, 38–51. London: Routledge. https://www.academia.edu/31226707/Silvia_Gherardi_SOCIOMATERIALITY_IN_POSTHUMAN_PRACTICE_THEORY?email_work_card=interaction-paper.

- González, Jennifer. 1995. “Autotopographies.” In Prosthetic Territories: Politics and Hypertechnologies, edited by Gabriel Brahm and Mark Driscoll, 133–150. Boulder: Westview. (PDF) Autotopographies | Jennifer A. Gonzalez - Academia.edu.

- Grima, Tyrone. 2022. “Zoom: A Case-Study.” Body, Space & Technology 21 (1): 1–21. doi:10.16995/bst.7964.

- Grotowski, Jerzy. 1969. Towards a Poor Theatre. London: Methuen.

- Jamieson, Helen Varley. 2022, June 9. “Mysteryclass.” Online speech on UpStage at Transit 10th Festival, Odin Teatret, Holstebro.

- Liodaki, Danai, and Giorgos Velegrakis. 2022. “Theatre Minus Physical Coexistence – A Glimpse Into Theatrical Experimentations in Greece During the Pandemic.” International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media 18 (1): 128–144. doi:10.1080/14794713.2022.2040290.

- Martinelli, Patrizio M. 2020. “The House as Theater of Memory: Mario Praz and his House of Life.” Home Cultures 17 (2): 117–143. doi:10.1080/17406315.2020.1863049.

- Massey, Anne, and Penny Sparke, eds. 2013. Biography, Identity and the Modern Interior. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Mastrominico, Bianca. 2021 “Towards an Ecology of Becoming: Digital Performance Research Under Covid-19.” Campus Life - Queen Margaret University (blog). January 18, 2021. https://www.qmu.ac.uk/campus-life/blogs/bianca-mastrominico/towards-an-ecology-of-becoming-digital-performance-research-under-covid-19/.

- Mastrominico, Bianca. 2022a. “Bodies:On:Live – Magdalena:On:Line.” International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media 18 (1): 196–199. DOI: 10.1080/14794713.2022.2028340.

- Mastrominico, Bianca. 2022b. “Embodying Essence Through Absence – Performance Practice and Pedagogy on Digital Platforms.” Journal of Theatre Anthropology 2: 266–281. doi:10.7413/2724-623X043.

- Mastrominico, Bianca. 2022c, September 2. “Flanker Origami Q&A.” Online speech on Zoom at English Theatre Milan, Italy.

- Mastrominico, Bianca. 2023. “Active Spectatorship and Co-Creation in the Digital Making of Flanker Origami.” Body, Space & Technology 22 (1): 100–127. doi:10.16995/bst.9737.

- Mastrominico, Bianca, and John Dean. 2020 “Live or Alive: A Reflection on Performance Practice in Pandemic (Digital) Times.” Campus Life - Queen Margaret University (blog). July 17, 2020 https://www.qmu.ac.uk/campus-life/blogs/bianca-mastrominico/live-or-alive-a-reflection-on-performance-practice-in-pandemic-digital-times/.

- Mastrominico, Bianca, and John Dean. 2021. “Bianca Mastrominico and John Dean: Flanker Origami.” Interview by Caro Moses. ThreeWeeks Edinburgh, August 20, 2021. https://threeweeksedinburgh.com/article/bianca-mastrominico-and-john-dean-flanker-origami/.

- McAuley, Gay. 2005. “Site-specific Performance: Place, Memory and the Creative Agency of the Spectator.” Arts: The Journal of the Sidney University Arts Association 27: 27–51. https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/ART/article/view/5667.

- McKellar, Susie, and Penny Sparke, eds. 2004. Interior Design and Identity. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Parker-Starbuck, Jennifer. 2011. Cyborg Theatre: Corporeal/Technological Intersections in Multimedia Performance. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pearson, Mike, and Michael Shanks. 2001. Theatre/Archaeology. London: Routledge.

- Postiglione, Gennaro, and Eleonora Lupo. 2007. “The Architecture of Interiors as Re-writing of Space: Centrality of Gesture.” Paper presented at the Thinking Inside the Box Interiors Forum Scotland, March 1–2. http://www.lablog.org.uk/wp-content/paper-insidethebox.pdf.

- Sermon, Paul, Steve Dixon, Sita Popat Taylor, Randall Packer, and Satinder Gill. 2022. “A Telepresence Stage: Or How to Create Theatre in a Pandemic - Project Report.” International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media 18 (1): 48–68. doi:10.1080/14794713.2021.2015562.

- Shanahan, A. M. 2013. “Playing House: Staging Experiments About Women in Domestic Space.” Theatre Topics 23 (2): 129–144. doi:10.1353/tt.2013.0028

- Shaw, Peggy, and Lois Weaver. 2020. “Last Gasp.” Split Britches. Accessed February 17, 2023. http://www.split-britches.com/last-gasp.