ABSTRACT

In a post-Covid context, the term presence has become the subject of renewed academic focus, amplified by mass phenomena such as Zoom fatigue and online classroom teaching. The prism of new materialism allows for a new reading of relationships between technology and human sensing, physical and virtual presence and copresence, with possible design implications: Current research in public health and social-environment discourse is interested in the effect of presence on well-being. As a theoretical framework, new materialism provides a lens that foregrounds complex relations between affect and technology, enabling us, through interventions like the KIMA: Colour participatory artwork, to interrogate the broad discourse on mediated presence and social connectivity. This paper provides an overview of the AHRC-funded research project, 'p_ART_icipate!', which is a collaborative investigation led by the University of Greenwich, CNWL NHS Foundation Trust, and Brunel University. This paper describes one of the case studies within the project, ‘KIMA Colour’, a collaboration with the art collective Analema Group, the National Gallery and the Royal National Institute of the Blind (RNIB). The case study explores the effect of collective cultural experiences and participatory art on a sense of social connectivity and copresence. In collaboration with RNIB and a group of visually impaired individuals, the team asked how we can design meaningful and accessible online interfaces that actively contribute to a sense of ‘participatory presence’. Findings suggest a possible link between the experience, presence and social connectedness. This research aims to contribute to our understanding of participatory art and to provide recommendations for accessibility and facilitation designc for participatory online interfaces.

Introduction

In today’s increasingly digital world, the concept of presence has taken on new significance. With the rise of online communication and virtual interactions, presence has taken on renewed conceptual parameters. In this paper, we explore the recent history and evolution of the term (tele-)presence, examining its relationship with copresence and social connectedness and its relevance in a post-Covid context. Furthermore, we examine the role of participatory arts in fostering social connectedness, copresence and the potential impact on health and well-being ().

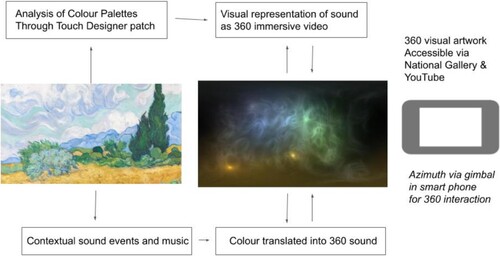

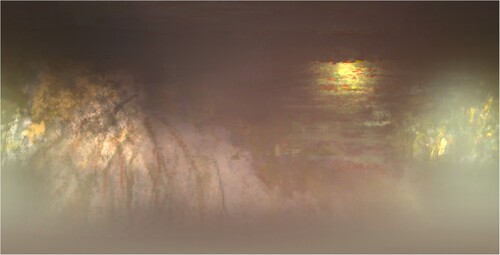

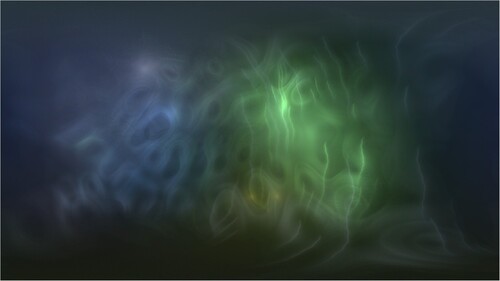

Figure 1. KIMA Colour: Van Gogh – Still from the artwork – Analema Group 2020. The artwork maps colour palettes in Vincent VanGogh’s A Wheatfield with Cypresses onto sound events and visualises these as a 360 video with corollary 360 soundscape. The Analema Group created the artwork in a residency at National Gallery, London and revisited them in focus groups with Royal National Institute of the Blind in 2022 to inform design decisions on participation, facilitation and accessibility.

The study was comprised of two strands: the conception and realisation of an interactive, accessible artwork, and a focus group that sought to draw meaningful data from the participants’ experiences. By utilising their smartphones, visually impaired participants were able to translate three selected paintings from The National Gallery into 360 sounds. Using their phones’ cameras and a specially designed application allowed visually impaired participants to navigate their own audio-visual paths of understanding through the reinterpreted artworks. The colours of the original masterpieces were translated into OSC values that in turn triggered visual and sonic events, offering a new aurally-centric means of exploring paintings. Following the engagement with the artwork, participants came together to respond to the experience through a small participatory exercise. Pre- and post-focus groups were held, with discussions and questionnaires structured around existing participatory arts research themes and models. Importantly, participants informed questions around accessibility, contextualisation and further development of the KIMA Colour artworks. Associated data concerning engagement with the artwork and its relation to perceived social connectedness was extrapolated from these focus groups by means of qualitative and quantitative statistical analysis tools. This research was informed by a theoretical framing situated within new materialism (Parikka Citation2012), which foregrounds the relevance and materiality of social, perceptual human events as much as the multi-layered materiality of tech design and interaction processes. Converging concepts from different schools of thought such as new feminist materialism Haraway (Citation1988), Braidotti (Citation2013), Barad (Citation2007), queer theory (Butler Citation1990) and actor-network theory (Latour Citation1999), new materialism signals a shift towards materiality as having agentive values entangled with social constructs, practices and affects (compare: Folx and Alldred Citation2015; Serafinelli and Villi, Citation2017). Deleuze and Guattari theorised the importance of social affect – a concept that is central to most new materialists (Deleuze and Guattari, Citation1987).

In her text on critical vitalism, Delitz (Citation2021, p.120) states,

Technical or material vitalism posits a new idea of technical beings, and of human (i.e. cultural) activity. It thus gives rise to a new notion of ‘liberty’: as an affective resonance between the human actor and matter – unlimited by social norms – in which creativity lies with matter itself …

Since the term (tele-)presence was coined by Marvin Minsky (Citation1980), academic definitions of the concept have experienced multiple evolutions. Influenced by cybernetic theory, early academic discourse around telepresence focused on concepts such as agency, control, and distance communication. However, as technology advanced and new forms of virtual interaction emerged, the central role of human perception moved into the foreground of academic debate. Presence came to be understood as a psychological state or subjective perception, mediated through technology but experienced as an illusionary perceptual experience.

In a post-Covid world, where online communication has become even more prevalent, research across various disciplines continues to explore the links between presence experience, user experience design, social connectedness, and health and wellbeing. The term social presence has emerged as a means of defining presence as a social phenomenon, not limited to mediated environments, but inclusive of the environments within which practices take place. In this interdisciplinary context, the notion of social connectedness as a measurable and fluid concept has become highly relevant. Through our analysis, we aim to contribute to the ongoing academic discourse on presence and its role in our progressively digital society, while shedding new light on user experience, accessibility and interaction design.

Theoretical background

Presence, social presence and copresence

Academic definitions of the concept of (tele-)presence have experienced multiple evolutions, not least due to the many seismic technological shifts that have occurred. In the Nineteenninetees, Roy Ascott asked whether there is ‘love in the telematic embrace’ (Ascott Citation1990). Ascot conceptualised presence as a means to ensure intimacy so as to bridge a digital disconnect between technology and humanity, but also between humans. This dilemma remains at the core of academic discussion in presence research and public health alike. Influenced by cybernetic theory, 1980s academic discourse around telepresence was frequently characterised by a techno-centric definition, focusing on concepts of agency, control and distance communication. Only in the 1990s did the role of human perception moved into the foreground of academic debate: Paul Sheridan famously described telepresence as the ‘experience of being there’, shifting the focus onto the individual and the notion of embodiment (Sheridan Citation1992). In 1997, Lombard and Ditton’s publication ‘At the Heart of it All’ promoted an influential definition that described presence as the ‘perceptual illusion of non-mediation’. Lombard and Ditton’s conceptual prism understands presence as a form of mediation through technology that recedes behind an ‘illusionary perceptual experience of non-mediation, in which the experience of the technological method becomes secondary to the interaction’ (Lombard and Ditton Citation1997). The International Society of Presence Research built on this idea, describing ‘presence as a psychological state or subjective perception in which even though part or all of the individuals’ current experience is generated by or filtered through a human-made technology’ ‘part or all of the users’ experience fails to acknowledge this experience accurately’ (ISPR Citation2000). From an interdisciplinary, new materialist perspective the role of technology is not necessarily secondary to human perception, but a central event with a complex set of interrelations with human (I.e. perceptual and social) factors which warrants further analysis.

The term copresence was coined by Goffman (Citation1966), initially to describe the effect of human presence on behaviour. However, as presence discourse over the following decades has shown, the effect of copresence is not limited to the physical or spatial presence of other actors (Campos-Castillos and Hitlin Citation2013). Copresence has been observed across virtual interactions as well as non-human agents (ibid), and consequently describes the social and perceptual effect of the presence of others within a given situated interaction. Its very notion reaches beyond the binaries, a key objective of new materialist theories. New materialism focuses on matter as alive, socially charged and ‘agentive’ (Gamble, Hanan and Nail Citation2019), and its fascination with the sciences (ibid)have led to a new reading of copresence as a direct result of technological engagement with potentially quantifiable impact. In the context of a new materialist discussion of copresence and social presence, the notion of social connectedness as a measurable concept seems therefore highly relevant for discourse and analysis.

From a humanist, social constructivist and critical theory point of view, the concept of social presence has emerged as a way to understand presence as a social phenomenon, distinct from technical parameters and purely conceptual descriptors. Social presence is defined as a sense of ‘being together with one another’ (Biocca et al. Citation2003, 9). From a new materialist point of view, social connectedness is not distant from technology, but an interconnected event with its own ‘materiality’ that is the result of technological mediation resulting in a state of ‘being as mediated’ (Couldry Citation2004; Kember and Zylinska Citation2012).

Social connectedness, social presence and participatory arts

Social connectedness has been conceptualised by Lee and Robins as the relationship between oneself and other people as well as ‘the feeling of including how emotionally distant or connected one feels to individuals and society’ (Lee and Robins Citation1995; Perkins et al. Citation2021, 2). A large-scale study spearheaded by the Centre for Performance Science at Imperial College and the Royal College of Music revisited this concept in the context of arts engagement. The HEartS study (N = 5982) has shown a strong link between artistic engagement and social connectedness, with possible effects on perceived loneliness (Perkins et al. Citation2021).

Social connectedness is seen as a response to short-term social interactions, and as such has been clearly delineated from loneliness which is conceptualised as more long-term. Researchers at Eindhoven University of Technology defined social connectedness as ‘a short-term experience of belonging and relatedness, based on quantitative and qualitative social appraisals, and relationship salience’ (Bel et al. Citation2009). On an individual level, social connectedness has been correlated with higher self-esteem (Ashida and Heaney Citation2008), reduced loneliness (O’Rourke and Sidani Citation2017), lower cortisol indicating lower stress levels (Turner-Cobb et al. Citation2000), higher oxytocin levels (Knox and Uvnas-Moberg Citation1998) and ultimately to higher life expectancy (Berkman and Syme Citation1979; Seeman et al. Citation1987). On a collective, societal level, social connectedness has been shown to lead to higher trade flow, cross-county migration and increase of patents (Bailey et al. Citation2018).

A new materialist understanding of social connectedness would suggest a more complex reading, in which technical parameters and social presence/copresence form an interdependent event or assemblage. In her book Affective Connections Golańska (Citation2017, p191) suggests that the act of engaging in participatory arts can problematise anthropocentric versions of copresence, stating that ‘Such processes necessarily bring back the questions of connectivity and entangled coexistence, which are about being open to experimental transformations or unexpected reconfigurations’. In this vein, new materialists propose a complex interplay between materials, physical and tangible forces and immaterial, psychological and social factors (Barad Citation1996, 181; Braidotti Citation2013, 3). A more complex model of underpinning relationships between technology and mental wellbeing might help to elicit new insights into potential material multiplicities and reflexive dynamics between participants, their well-being and technology and in particular in the field of arts and health, participatory arts and social connectedness.

For example, these theories have been demonstrated in empirical research where a meta-analysis of participatory arts projects covering 44 studies points to the positive effect of participatory arts on social connectedness, and as a potential tool to reduce loneliness (Dadswell et al. Citation2017). Multiple studies also referred to the potential of participatory arts practices to support well-being (Giordano and Lindstrom Citation2010) as well as community cohesion and social connectedness (Bigby and Anderson Citation2021; Gingrich et al. Citation2019; Hiltunen et al. Citation2020).

Furthermore, a growing body of research attests to the effect of participatory arts on the recovery from mental well-being challenges (Gallant et al. Citation2016; Secker et al Citation2018) and the All-Parliamentary Creative Health Report (Citation2017) cites evidence for the impact of participatory arts on the well-being of older people including issues related to aging, loneliness and social isolation (APCHR Citation2017). The Mental Health Foundation linked participatory arts in care homes to opportunities for meaningful social contact, support and friendship, improved relationships, and increased social cohesion for dementia patients (Mental health foundation, Citation2011: Compare Dadswell et al. Citation2020). Participatory arts have been shown to lead to collective enjoyment, supporting and encouraging others, developing a sense of camaraderie and community and strengthening friendships (Dadswell et al. Citation2020).

In recent academic debate, particular research focus has been given to the effect of arts engagements on perceived social connectedness (Perkins et al. Citation2021, Toepel Citation2013), such as communal singing and humming (Fancourt and Perkins Citation2018; Lagacé et al. Citation2016; Bullack et al. Citation2018), museum visits (Bennington et al. Citation2016), or textile crafting (Nevay et al. Citation2019). While there is ample evidence to suggest that participatory arts have a direct effect on social connectedness, new materialist analysis of participatory arts, technology-related events, and human perception might help to shed light on interaction design factors that can inform the development of (specifically) digital participatory arts interfaces, and offer input on significant knowledge gaps on the design and facilitation of participatory arts practices in an online context.

From the perspective of this research, social connectedness is conceived of as a pragmatic attempt to utilise participatory and accessible art interventions to counteract the perceived dislocation of technologically-mediated communication. Early media theorists were quick to recognise the potential relationship between technological dissemination and social isolation – what Guy Debord described as the ‘vicious circle of isolation’’, in which ‘technologies are based on isolation, and they contribute to that same isolation’’ (Debord Citation1977, 10). Whilst contemporary technologies offer a far more complex reading of social interaction, it is nonetheless pertinent – particularly as with further extend our online lives – to continue to seek ways to respond to this fundamental paradox routed in a technological condition.

Design process for a digital participatory artwork: kima colour

The KIMA Colour research project focuses on the effect of participatory arts on social connectedness in distributed networks. We focused on the design of digital participatory arts that aimed to promote collective and collaborative arts engagements, copresencing and social connectedness.

These theoretical propositions led us to pose the following question: ‘How can participatory arts facilitated by digital media, strengthen social connectedness and social presence in the post-COVID era?’ This query is especially pertinent considering the enduring difficulties presented by the COVID-19 pandemic that has emphasised the importance of creative methods to encourage social presence in an increasingly digital age.

The KIMA Colour artworks were originally commissioned by National Gallery X as part of a residency, a collaborative initiative between The National Gallery and King’s College London. The art pieces were produced by The Analema Group, an art collective known for their innovative approach to blending arts and technology. The central objective of the project was to translate three well-known artworks from the National Gallery’s collection, specifically works by Monet, Van Gogh, and Van Eyck, into immersive 360 visual soundscapes ().

Figure 2. KIMA Colour: Monet – Still from the artwork – Analema Group 2020. This is a still from the 360 video and soundscape as commissioned by National Gallery as part of the Analema Group’s residency at National Gallery X in June 2020.

The innovative artistic intervention sought to reinterpret the colour palettes and visual elements of the original paintings into ambisonic sound experiences. This transformation allowed participants to experience the artworks through ‘visual’ sound, offering a novel and accessible way for the visually impaired to engage with art remotely. The 360 videos of these soundscapes were made available through National Gallery's YouTube channel, ensuring widespread accessibility and ease of participation.

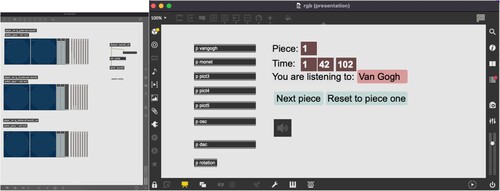

The development of these artworks was supported by the team at the National Gallery, and a pilot study was conducted with RNIB to evaluate the appropriateness of the survey questionnaire and the artistic intervention. By exploring the role of the arts as a nexus between participatory, accessible, and inclusive experiences, this project aimed to investigate the use of digital technologies to foster collective and collaborative art engagements and social connectedness among participants. The artistic intervention was designed to offer a unique multi-sensory experience, providing individuals with visual impairments the opportunity to connect with arts in more meaningful, social and personal ways. The integration of arts, technology, and inclusivity in these digital participatory artworks opens up new possibilities for engagement and appreciation of the arts in a remote context. The seamless blend of visual elements from iconic artworks into auditory experiences () allowed participants to experience art beyond the traditional visual medium.

Figure 3. KIMA Colour: Max MSP patch translating colour into sounds – Analema Group 2020. This image shows the Max MSP interface for ambisonic sound that receives OSC messages on colour values from the original paintings in the National Gallerys collection that are then translated into sound events. These sound events are then forwarded via OSC messages back to Analema Group’s Touchdesigner patch that reciprocally translates these sounds into visual events – effectively creating an audio-visual feedback loop for the participants.

Using original code developed in Touchdesigner (Derivative.ca), and MaxMsp (cycling74), () the Analema Group translated colour palettes into sounds across three paintings – Monet’s ‘Water Lillies, Setting Sun’, Van Gogh’s ‘Wheatfield with Cypresses’ and Van Eyck’s ‘Arnolfini Portrait’. Moving the phone, sounds and colours derived from these paintings can be discovered interactively. Embellished through a non-narrative sound journey based on discussions with curators and researchers at National Gallery, these three artworks were accessible via National Gallery’s website and YouTube channel while the National Gallery itself was closed due to the UK national lockdown.

Methods

The research methodology employed a mixed methods approach to investigating the impact of collaborative and participatory online art engagement on social connectedness, with a particular focus on consideration of accessibility needs. This small-scale user study aimed to shed light on best practices in the design and facilitation of online arts engagement. The methods encompassed focus groups (n = 12), surveys (n = 17), self-reporting, and observation, each contributing a unique dimension to the study. Positing that a more pronounced engagement with the artwork would foster a stronger sense of social connection, the researchers took on the role of facilitators, framing the experience through the use of onboarding discussions, descriptive tools, and tutorials. Whilst it is expected that this process might result in increased social connectedness in and of itself (by, for instance, relaxing and familiarising a group of participants in advance of using the application), such activities were primarily undertaken with a view to galvanise the social qualities of the artistic engagement itself. Such discussions exemplified the New Materialist grounding of the project as a whole, working to create the conditions by which participants could more autonomously explore the artworks on offer. Building upon the criterion for performative new materialism (Gamble et al. Citation2019), the role of the facilitators was to encourage emergence and pedesis, a framing in which participants’ contributions were both indeterminate and developmental, freely moving between the staging posts – in this case artworks and cultural contexts – presented by the research team, and as such able to autonomously explore the concepts presented.

Focus groups

A series of focus group sessions were organised as a pivotal component of the study. Focus group sessions centred around best practices in the design and facilitation of these participatory online experiences, as well as measuring the effect of participatory online art on social connectedness. The participants were recruited from the visually impaired community through RNIB. These sessions were facilitated collaboratively by the research team and RNIB project coordinators. The primary objective of the focus groups was to describe the experiences and perceptions of the participants, with a specific focus on their impact on social connectedness and copresence. The sample size for each focus group ranged from 6 to twelve participants (n = 12).

Surveys and self-reporting

Survey instruments were employed to gather structured quantitative data, supplemented by self-reporting from the participants. The surveys aimed to capture a broad range of responses related to participants’ engagement, emotional experiences, and perceived levels of social connectedness during the online art interventions. Self-reporting allowed participants to provide subjective insights, shedding light on their personal experiences and reflections. The total number of survey responses was (n = 17) across three focus group sessions out of a sample size of (n = 12).

Observation

Observation served as a vital method to gather qualitative data in real time. The research team engaged in observing the participants’ interactions, expressions, and behaviours during the online art engagement activities. This method provided valuable contextual information, enabling a more nuanced understanding of participants’ engagement beyond what was self-reported.

Ethics approval

Prior to the commencement of data collection, the research project adhered to rigorous ethical guidelines. Ethics approval was sought from both University of Greenwich and University of Roehampton, with input from Brunel University and CNWL NHS Foundation Trust. This collaborative approach ensured that the research was conducted ethically and transparently, with due consideration to the welfare and rights of the participants.

Pilot study

Following the attainment of ethics approval, a pilot study was conducted. The pilot aimed to assess the suitability of the artworks for implementation and identify any potential issues that needed to be addressed before the commencement of the focus group sessions. This preliminary investigation involved twelve participants (n = 12).

Whereas the original KIMA Colour artworks were geared towards the general public, the p_ART_icipate research project revisited the artworks so as to make them more accessible to visually impaired audiences. In a co-creation workshop, the team received valuable feedback in three areas on accessibility, contextualisation and participation – feedback that was implemented prior to the focus group sessions:

Accessibility: Originally designed for the general public, the three artworks were lacking any audio description on how to access the experience. Important information regarding the use of headphones had been discarded and a ‘How to video’ for iPhone and Android users was absent. In collaboration with RNIB and CNWL NHS Foundation Trust, the decision was made to create instructional videos to help with onboarding. For one of the experiences, KIMA Colour Van Eyck, an optional technical feature was added: using a ‘Woojer’ belt, low frequencies were amplified so they can be felt on the body through the use of a strap-on belt. This Woojer belt allows low frequencies to be felt as ‘tangible’ sound, adding a new multi-sensory layer for users with visual impairments.

Context: The artworks were designed to provide contemplative immersive experiences. However, they lacked context, which diminished the impact of the sound experience that drew heavily from historical and contextual inspirations within the original masterpieces. To address this issue, Professor of Practice in Arts Therapy, Professor Dominik Havsteen-Franklin at Brunel, provided feedback and input. As a result, three onboarding and offboarding videos were created to provide historic and artistic context, and to support the experience on a psychological and cognitive level.

Interaction Design: To support a shared online experience of the artworks, the Analema Group created additional forms of interaction to follow on from the engagement, including word clouds and a collaborative poem to strengthen the participatory aspect of the experience.

Following a pilot with RNIB staff to assess the suitability and clarity of the survey, as well as the practicability of administering the survey online for the visually impaired, a total of four focus group sessions provided insights into perceived social connectedness:

Four focus groups with varying sample sizes of between 6–12 participants each consisting of adults 18–55 years of age with varying degrees of visual impairments, as well as two RNIB staff, artists of the collective Analema Group, as well as CNWL NHS Foundation Trust specialist Claire Grant, attended sessions.

Focus groups were taking place online synchronously (Fox et al., Citation2007), allowing for a heterogenous group of visually impaired participants from across the United Kingdom including Northern Ireland, Scotland, England and Wales – and were guided and led by the principal investigator following principles for synchronous online focus groups proposed by Moore, McKee and McLoughlin (Citation2015): Discussions were participant-led, and reflexive in nature and encouraged group conversations (Goss and Leinbach Citation1996).

The research protocol was shared with participants ahead of time, and informed consent was sought prior to session start to record sessions, which were transcribed and fully anonymised following the session. Each session was preceded by a pre-session questionnaire before facilitation videos and arts experiences were shared with the audience. Finally, the artwork and audience participation was facilitated. This shared experience was then followed up with a post-questionnaire and some time for feedback and outlook. As intended, the focus groups allowed for an in-depth evaluation of the development, participant-led discourse on the nature of digital participatory arts, as well as the notion of accessibility in this context.

A thematic analysis (Braun and Clark Citation2006) was conducted on focus group transcripts and observation. In phase 1 verbal data was transcribed, so for researchers to familiarise themselves with the data. Using an inductive, data-driven mode, this data was then coded in phase 2, and analysed for themes and thematic clusters in the following phases, with several consistent themes emerging in the analysis. The findings bring together statistical findings from the survey as well as the thematic analysis of focus groups and observation. The analysis involved several well-defined phases, ensuring a systematic and comprehensive examination of the data:

Phase 1: Transcription and familiarisation.

In the initial phase, the verbal data from the focus group sessions were transcribed by trained researchers. Transcription ensured that the researchers had a comprehensive written record of the participants’ discussions and responses, enabling them to engage closely with the data. Familiarisation with the transcribed data allowed the researchers to engage with the richness of the participants’ narratives, gaining an intimate understanding of their perspectives.

Phase 2: Inductive coding.

With a familiarity with the data established, the researchers embarked on the inductive coding process. Inductive coding is a data-driven approach, where themes and patterns emerge from the data itself rather than being imposed based on preconceived categories. The researchers systematically reviewed the transcriptions, identifying meaningful units of information, and assigning descriptive codes to capture the essence of each unit. This process allowed the researchers to maintain openness to the diverse range of responses and experiences shared by the participants.

Phase 3: Identification of themes and thematic clusters.

In the subsequent phase, the researchers clustered the coded data into coherent themes and thematic clusters. This involved grouping similar codes together, identifying recurring patterns, and exploring connections between different codes. The emergence of multiple themes and thematic clusters from the data indicated the richness and complexity of the participants’ experiences. The researchers ensured that the themes were both internally consistent and distinct from one another, providing a nuanced portrayal of the participants’ perceptions.

Phase 4: Thematic analysis.

Having identified the themes and thematic clusters, the researchers engaged in a comprehensive thematic analysis. They delved deeper into each theme, examining the underlying meanings, nuances, and variations within them. This process enabled a holistic understanding of the participants’ engagement with the artwork, and shed light on the factors that influenced their perceptions. Following Braun and Clark’s methodology for thematic analysis (Citation2006), the research team analysed transcripts using the Dedoose software packages for coding, with several clusters and themes emerging across the focus groups.

Integration of statistical findings and thematic analysis.

The researchers combined the statistical findings from the surveys with the results of the thematic analysis. The statistical data provided quantitative insights, while the thematic analysis offered qualitative depth and richness. By integrating these two types of data, the researchers ensured a comprehensive and robust examination of the research question, enriching the overall interpretation of the findings.

Results

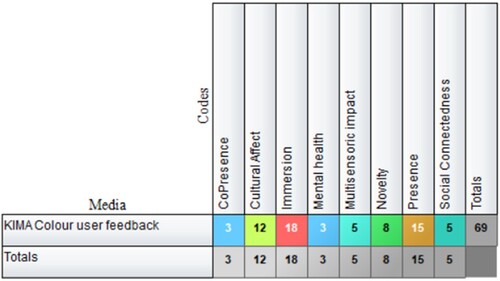

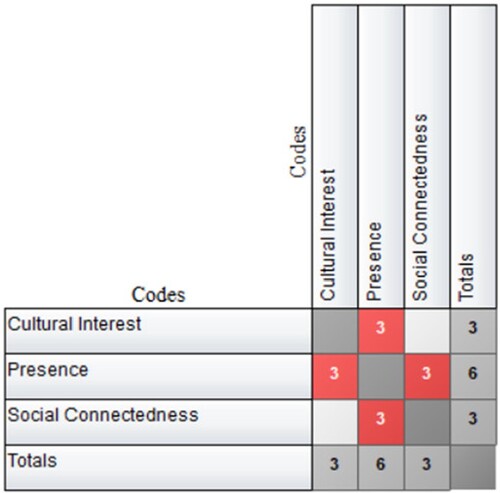

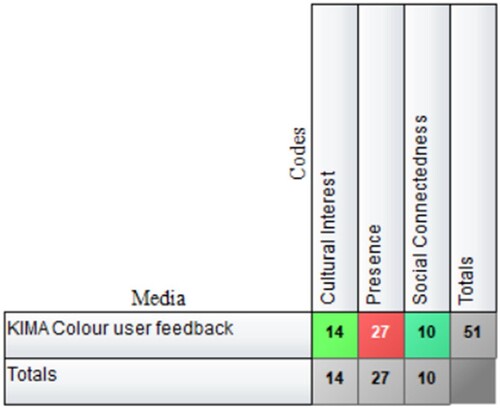

In line with new materialist considerations, research findings are considered as ‘‘research assemblages’’ (Fox and Alldred Citation2015) – a series of insights consisting of connections and clusters of events. Following Braun and Clark’s methodology (Citation2006), during the first and second stages, transcripts were inductively coded into several groups to produce thematic clusters across a total of 69 excerpts. The following stages resulted in the identification of three overarching themes. In phase 3 of the thematic analysis, three overarching themes emerged through the coding of focus group and observation transcripts ( and ).

In the following phases, these thematic clusters were synthesised, summarised and analysed in three groups: Multi-sensory Presence and Immersion, Novelty and Cultural Recontextualisation, and Social Connectedness. Mediating factors were identified both in the group and pilot phases, including accessibility, contextualisation and interaction design.

Multisensory presence and immersion

The facilitation of a 360 visual sound experience in the artwork led to a heightened degree of immersion, which was possibly amplified by its multisensory nature. Participants reported an impact on their spatial perception, mood, atmosphere, and submergence within the artistic experience. Interestingly, they also noted a sense of ‘being there’ that went beyond mere description and suggested a real sense of presence.

It sounded as if it was different stages in the day, like getting up, it sounded like a dawn.

you could really sense it. I felt like I was within the actual art itself.

These responses suggest that the spatial component of the sound as a 360 ambisonic experience played a key role in supporting the sense of immersion. In addition, the translation of colour into sound appears to have contributed to a shared cultural experience of the artwork.

You get a sense of the room as quite airy, nearly like a conservatory with quite high ceilings.

I really felt I could really picture the colours.

The participant statements suggest that by combining multiple sensory inputs in an artistic experience, it is possible to create a heightened sense of immersion and presence. This appears to have had a significant impact on the participants’ experience, enhancing their sense of connectedness and engagement with the artwork. Overall a strong feeling of both multi-sensory immersion and presence could be observed with a large number of mentions (27/69) relating to this theme. Such responses might well be read as the actualisation of co-presence, an embodied feeling of Barad’s ‘intra-action’ (2007), wherein it is the agential encounter between human and non-human actors that brings matter to life, and from which its potential emerges. The participants of KIMA: Colour don’t simply experience the effect of remediation (framed here as a prioritisation of the sonic as means to enliven the visual), but rather the sense of being that comes from their role within the enlivening process.

Novelty and cultural recontextualisation

The integration of contextual information in the immersive 360 visual soundscapes project played a pivotal role in facilitating a transformative experience for the participants. The contextualisation served as a gateway, inviting participants to transcend traditional boundaries of art appreciation and immerse themselves in the world of the artists.

Participant responses exemplify the impact of contextualisation on their artistic encounter. One participant expressed, ‘It was fascinating, a first-time experience of something like this in my life’. This sentiment reflects the novelty introduced by the amalgamation of sight and sound, providing participants with a multisensory artistic experience.

Moreover, participants’ accounts underscore the immersive and dramatic nature of the experience. One participant remarked, ‘It was very different to what I expected it to be, a very creative approach’. The interplay of visual soundscapes produced a vitality within the artworks, transcending the confines of the canvas and transforming the art encounter. As the artworks unfolded through participation, participants were no longer passive observers but active participants in a multidimensional interaction.

In the case of Van Gogh's works, contextualisation was described by participants as an emotional and empathetic exploration of the artist's vision. As expressed by one participant, ‘I experienced Van Gogh differently, it was like I went to the theatre’. The contextualisation allowed them to connect with the ‘artist's emotions and mindset, transporting them to an embodiment of Van Gogh's creative act'. Furthermore, the contextualisation served as a gateway to the artists’ intentions. One participant remarked, ‘I looked at his work in a whole ‘nother way/ I felt his (Van Gogh's) mood and his mindset a lot’. This insight suggests that contextualisation allows participants to empathise with the emotions and thoughts that may have motivated Van Gogh's expressions.

Participants left the experience with new perceptions and enriched appreciation for arts, culture, and history. The social significance of the artworks became apparent, drawing participants closer to the art and the worlds it recreated. Engagement is not simply confined to knowledge accumulation, however. The affordance of the emergent, inter-medial process is, as with any dialogic pedagogy, to advance being. The resonance of matter, as per the New Materialist position, amounts to a bilateral process of becoming born of the encounter with Other, what Gilbert Simondon described a ‘individuation’ (Scott, Citation2014), and in which ‘each act of knowledge [is] an ontoepistemological process of individuation emerging from physical, biological, technical and psychosocial processes’ (Bardin, Citation2021, p.37).

Social connectedness and mental health

The collective facilitation and shared engagement with artworks, accompanied by ensuing discussions, played a pivotal role in amplifying social connectedness and fostering a stronger sense of community among participants. Activities designed to encourage participation, such as the collaborative poem and the word cloud, appeared to enable a sense of agency, notably contributing to a heightened sense of copresence.

Participants reflected on their experiences, highlighting the potential for identification with other participants. They expressed that their engagement naturally evolved into social relationships and emphasised the essential role of the group dynamic, not merely as something pleasant but as a necessary component of meaningful engagement. This process even sparked in-depth discussions about the artworks, enriching the collective experience of co-presence.

Participants noted ‘You could identify yourself with the people’ that they would ‘organically progress into a social relationship’ and that ‘the group aspect’ in participation of the artwork (wordcloud) was not just ‘nice, but necessary’ and that this process ‘led to a discussion of the art’. Furthermore the effect of the experience on mental health was explored, with one participant noting that they thought that ‘I do think having art in this way is more therapeutic’. Many participants also characterised the experience as ‘soothing’.

Qualitative exploration of social connectedness was supported through pre – and post-participation questionnaires. However, the relatively limited sample size constrains the extent to which conclusive insights can be drawn from this data.

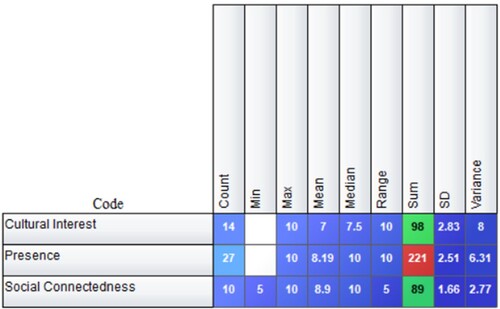

Quantitative data

The sense of community and social connectedness is backed up by small-scale quantitative surveys that were conducted as pre – and post-intervention questionnaires. Although these user surveys, the feeling of social connectedness increased overall: SSocial connectedness was measured through the a validated survey, the ‘‘Inclusion of the Other in the Self-’ (IOS) questionnaire (IOS) devised by Aron, Aron and Smollan (Citation1997). In addition to this standardised visual method, we asked the question about feelings of social connectedness: While the IOS survey (n = 17) indicated a relative increase in social connectedness with a mean average value of 3.8/7 post engagement compared to a mean of 3.52/7 pre-engagement, the IOS-results remained statistically insignificant (p < 0.2). However, the direct question ‘How close do you feel to the other participants’ yielded significant results. The question was posed to a small sample of participants (n = 17) pre – and post engagement with Likert scale responses ranging from values of 1–7. The mean average for this survey question post response was 3.975 post engagement compared to a mean average value of 3 pre-engagement. This change in perceived social connectedness constitutes a significant effect with a measured p-value of 0.03383.

While the feeling of social connectedness increased overall, some users reported feeling less connected with each other following the experience. This could also be attributed to the fact that the nature of the artwork was essentially immersive, with the participatory aspect of the artwork being the only component of the interaction design. Overall, social connectedness increased through audience participation – evidence that is further supported through observation and thematic analysis of the data. But the findings also point to a tension and ambiguity between presence design and social connectedness: Could highly immersive experiences affect a sense of social connectedness and community building negatively?

The utilisation of mixed methods yielded evidence indicating a correlation between participatory online arts engagement and social connectedness. Qualitatively, a comprehensive analysis was conducted on a set of 67 excerpts generated by 12 participants. These excerpts were systematically coded, weighted, and subjected to thematic analysis to determine their frequency.

Among the emergent themes, ‘Multi-sensory Presence and Immersion’ was prominent, with a total of 27 excerpts coded. This prevalence of the presence and immersion theme was even more noteworthy considering that its frequency exceeded the combined total of the other two themes (, and ).

While this analysis does not allow for a clear understanding of interdependencies of these factors, it is clear that the artwork design and facilitation resulted in perceived presence and immersion for the focus groups, and the effect of artistic engagement on social connectedness is further supported by the quantitative analysis. Such findings suggest that framing participatory artworks with structured methods of auxiliary engagement – particularly coupled with a degree of autonomy – might not simply provide added value to the experience, but create the conditions of far more meaningful contextualisation. This, in turn, poses a fruitful question for online contexts – how might such contextual facilitation be further integrated in a virtual or mediated environment? And further, how do digital mediated environments advance or complexify notions of materiality and presence?

Discussion – participatory presence design

New materialist theories point to a complex relationship between matter, perception and affect through a multiplicity of events, considered an assemblage (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1987; Haraway Citation1991) that constitute the triangular relationship between agentive bodies, things and ideas, or more specifically in the context of this research, matter (technology), human perception (presence/immersion) and affects (social connectedness). New materialist theorists frequently ask the question of where (and when) the materiality of media happens (Parikka, Citation2012, 98). This research project focuses on participation design for online interaction as a key element of this materiality – with the aim to gain new insights into the complex relationship between interaction design, technology and human affect, in which digital spaces amount to ‘hybrid configurations of bodies, selves, and technologies’ (Lupton and Maslen Citation2018, 198). Our findings support existing research on the effect of participatory art on social connectedness, and point to the relevance of presence design in creating a sense of immersion. While these two phenomena are currently mostly considered discreetly in contemporary academic debate, questions need to be asked about how much user immersion contributes to a sense of social connectedness in shared online experiences or whether there could be a negative relationship between feeling absorbed in an experience, and perceived connectedness with others. If this was the case, how could interaction design compensate?

Whereas research into social presence has yielded important findings in this context, future research might consider participatory presence as a sub-category of social presence. Reflexive thematic analysis following Braun and Clark (Citation2006) of this research project points to a potential intrinsic relationship between presence and social connectedness, which could be highly relevant for future design considerations. While the statistical power of questionnaire data and focus group analysis remains insufficient to provide concrete evidence for such a correlation, discussions with participants shed light on the role of mediating factors. The pilot addressed three key areas for participatory presence design through a focus on accessibility, contextualisation and interaction design, and the thematic analysis points to the relevance of presence, affect and social connectedness in this context. As a concept, participatory presence can be seen as a shared feeling of being in the moment through creative practice – an exciting prospect that links artistic engagement and shared creative and cultural experiences with the potential for social connectedness, community building and social cohesion.

In this context, this study illustrates how much there is to learn from groups with accessibility needs – including the visually impaired. As designers, the clear and decisive feedback on access support needs, the need for further contextualisation of artistic practice and clear instructions on interaction design led to a co-created visual outcome that bears the signature of these participants. True participatory presence design will need to continue to consider the accessibility needs of vulnerable groups in our society, with opportunities for participatory co-creation and co-design to inform the participatory presence design of the future.

Limitations

This project was undertaken with the aim of exploring the design and facilitation of participatory art experiences in an online setting. However, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations that may impact the interpretation of the research findings. Firstly, the study employed a small-scale user study, conducting focus groups with sample sizes ranging from 6 to 12 participants. The limited number of participants might reduce the generalisability of the results to a broader population. Caution should be exercised when extending the findings to larger and more diverse audiences. To enhance the reliability and validity of the conclusions, future investigations could benefit from larger-scale studies.

Another potential limitation lies in the research methods utilised, which included self-reporting through surveys and focus group discussions. Participants’ subjective perceptions and memory biases may have influenced their responses, potentially affecting the accuracy and reliability of the data collected. Participants might have exhibited social desirability bias or struggled to articulate their experiences accurately. Although efforts were made to address self-reporting bias through anonymous data collection and open-ended questions, it remains a consideration in the analysis. Furthermore, the focus group sessions consisted of visually impaired participants recruited through RNIB. While this approach provided valuable insights into the experiences of visually impaired individuals, the homogeneity of the sample might limit the study's ability to capture diverse perspectives and experiences. Including participants with different types and degrees of visual impairments, as well as individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds, could offer a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of digital participatory art experiences.

The recruitment of participants through RNIB may introduce selection bias, as individuals already associated with the organisation may have different motivations and experiences compared to those unaffiliated with RNIB. Additionally, participants who volunteered to participate may possess a specific interest or prior exposure to participatory arts, potentially influencing the study's outcomes. A critical aspect missing from the research design is the absence of a control group for comparison. The study focused solely on evaluating the impact of participatory art experiences, lacking a control group that could provide insights into the potential effects of external factors or the passage of time. Incorporating a control group would strengthen the evaluation of the intervention's efficacy and aid in drawing more robust conclusions. Furthermore, the online nature of the focus groups may also introduce technological limitations, including connectivity issues or difficulties in fostering group dynamics. The absence of face-to-face interactions might impact the depth and quality of discussions, potentially affecting the richness of the qualitative data gathered.

However, despite the acknowledged limitations, the KIMA Colour research project offers valuable insights into the design and facilitation of participatory art experiences in an online context, with a keen focus on accessibility needs. The diverse combination of research methods, including focus groups, surveys, self-reporting, and observation, enabled a comprehensive exploration of participants’ experiences and perceptions. While the findings provide significant contributions to the field, further research utilising larger sample sizes, diverse participant groups, and control groups would augment the generalizability and reliability of the results.

Recommendations

Based on the results and findings from the study on the design of this study, several recommendations can be made to enhance the effectiveness and impact of similar initiatives in the future. We might consider these as talking points for practitioners developing similar digital participatory work in the future:

(1) Prioritise Accessibility: Ensure that participatory arts experiences remain accessible to diverse audiences, including individuals with disabilities. Embrace inclusive design principles to accommodate various needs and preferences, ensuring that everyone can engage fully with the artworks. By this framing, (digital) participation projects can be viewed as falling within the wider Inclusive Arts Practice discourse, an approach that expunges artist/participant and disabled/non-disabled hierarchies in favour of ‘mutually beneficial two-way creative exchange’ (Fox and Macpherson Citation2015, 2).

(2) Consider Facilitation: In the context of designing digital participatory arts experiences, facilitation cannot be an afterthought and needs to include onboarding and offboarding to artistic engagement. Perceptual, sensory, social and technical factors can support a profound facilitation strategy to support the experience. Adapting such approaches for digital settings – that is, maintaining a sense of communality despite the geo-dislocation of the technological medium – is vital to developing future research in order to build collaborative relationships and trust.

(3) Ensure Inclusive Immersive Design: Embrace multisensory immersion and presence as an accessibility strategy. Attempt to incorporate multiple sensory inputs, such as visuals and sound, to not only create a heightened sense of immersion and presence within the artistic experience, but to provide diverse points of entry to the participatory experience. The use of 360 visual soundscapes, as demonstrated in this study, can significantly enhance both sighted and visually-impaired participants’ engagement with the artwork and foster a deeper connection with the cultural and historical context. Furthermore, it must be considered that immersive digital design does not engender social connectivity in and of itself, but rather can create the conditions of its emergence (Biocca et al. Citation2003).

(4) Provide Contextualisation: Offer contextual information and background to the knowledge associated with the project to enrich participants’ understanding and appreciation. Co-created facilitation videos, like those utilised in this study, can serve as valuable tools to prepare participants for the experience and generate renewed interest in the artworks. Further contextualisation needs to consider cultural context and decolonisation, questions around sustainability, inclusivity, equality, and diversity.

(5) Embrace Novelty: Explore co-creative and innovative approaches in the design of digital participatory art experiences. Introducing novel techniques, such as translating colours into sound, can, evoke novel perspectives and an emotive response. While technical innovation can have implications for accessibility that need to be considered, novelty can contribute to making the encounter with the artwork a personal, unique and memorable experience.

(6) Foster Social Connectedness: Facilitate opportunities for collaboration and collective engagement during digital participatory art experiences. Activities like collaborative poems, word clouds, and allowing a sense of agency for participants can enhance social connectedness and community building. Shared experiences and resulting discussions cannot be an afterthought as they contribute to a stronger sense of connection among participants, as well as extend the salience of an experience beyond its temporal boundaries (Biocca et al. Citation2003). Adapting such strategies for online contexts is both vital and an area of ongoing research.

(7) Implement Quantitative and Qualitative Evaluation: Conduct both quantitative and qualitative evaluations to assess the impact of the participatory art interventions. Utilise pre – and post-intervention questionnaires to gauge changes in social connectedness and other relevant metrics. Supplement this data with thematic analysis to gain deeper insights into participants’ experiences and perceptions.

(8) Collaborate on Interdisciplinary Design: Foster collaborations between artists, researchers, technology experts, relevant organisations and audiences to bring diverse perspectives and expertise into the design process. Such interdisciplinary collaborations can lead to innovative and impactful digital participatory art experiences.

(9) Scale Up and Replicate: Consider scaling up successful participatory arts initiatives to reach broader audiences. Replicating these experiences in different cultural contexts or settings can provide valuable insights into the universality of the impact and the potential benefits across various communities. As exemplified through this case study, revisiting existing artworks with a focus on accessibility and inclusion can yield unexpected creative outputs, wellbeing benefits and deeper reflections into cultural contexts. New media offer new channels to increase public engagement, with accessibility as a key contributing factor in successful public reach;

By adopting these recommendations, designers of digital participatory arts projects can create meaningful and inclusive experiences that foster social connectedness, engage audiences on a deeper level, and contribute to the broader field of arts and culture. Additionally, further research and larger-scale studies could provide additional evidence to support existing research on the relationship between participatory arts and social connectedness and mental health, social and emotional wellbeing, with a view to developing specific strategies and approaches for digital and online contexts.

Conclusion

This research has provided insights into the complex relationship between media arts, presence design, and social connectedness in participatory online experiences from a new materialist perspective. In particular, our strategies engage with a perforative and co-constructive framing of being, in which artworks act as a shared means of enacting and enhancing social connectedness. The encounter by which matter ‘matters’, is not simply that of the human to the human, one discrete sentience to another, but rather a relationship in which knowledge is wrought from the vibrancy of the external, and through which ‘ontology and epistemology are inherently co-implicated and mutually constituting’ (Gamble et al. 122).

The findings suggest that there is a potential intrinsic link between presence and social connectedness, which could have significant implications for future design considerations. Alongside recommendations for the design of participatory online experiences, one of the key findings is the importance of engaging with vulnerable groups and incorporating their feedback into the design process. By doing so, we can work towards creating more inclusive and accessible participatory online art that foster social connectedness, community building, and social cohesion. While the KIMA Colour case study revisited and upscaled an existing artwork by adding multi-sensory components, new contextual onboarding and offboard videos and not at least new participatory engagements, co-creation processes require a profound feedback loop between participants, designers and developers. In the case of KIMA Colour, design suggestions by RNIB participants substantially changed the nature of the artworks and their facilitation. This is recourse to multi-sensory co-design is particularly relevant in light of challenges in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has highlighted the need for innovative approaches to fostering social connectedness in an increasingly digital world. As viewed through the prism of New Materialism, co-creation is less a drive towards benevolence, than an integral part of social connectedness. The bilateral development of ontology and epistemology requires that knowledge emerges from the active properties of being together: inclusive design prioritises ‘a collaborative process based on shared power, flexibility, trust and willingness to engage in mutual learning’ (Montgomery et al. Citation2022, 11).

The case study KIMA Colour () addressed three key areas for participatory presence design: accessibility, contextualisation, and interaction design. In collaboration with visually impaired participants, these areas were identified as being crucial for enhancing the user experience and fostering a sense of social connectedness among interactants. Design recommendations emphasise the capacity of participatory design, multi-sensory, immersive artworks and facilitation to contribute to measurable wellbeing; The KIMA Colour case study has demonstrated the potential of participatory presence design as a tool for fostering a sense of togetherness, community and social connectivity in shared online experiences. While further research is needed to fully understand the complex relationship between presence and social connectedness, this study provides a starting point for future research and investigations. While this pilot only included a small sample size, design insights are profound: By continuing to engage in co-creation design directly with participants, incorporating their feedback into the design process from the outset (), we can work towards more inclusive and accessible online art – fostering wellbeing, social connectedness, and a new sense of ‘participatory presence’.

Figure 9. KIMA Colour Still from 360 Artwork, Analema Group 2020. Based on feedback from RNIB participants, visual sound representation of colour was aided by a contextual sound layer, featuring a voice recording of Vincent Van Gogh’s letters to his brother, which helped to provide a layer of cultural context.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Oliver Gingrich

Dr. Oliver Gingrich is a programme lead on the BA (Hons) Animation - teaching as a senior lecturer across all three cohorts, research and creative practice. With an engineering doctorate in Digital Media, and 15 years of professional practice in the Creative Industries as Creative Director, Artist and Art Director, Oliver's research and artistic practice centres around real-time animation and participatory art: As the holder of an AHRC-research grant for participatory media arts and its effect on social connectedness and public health, he is exploring the intersection between co-creation practices, art and wellbeing.

Dominik Havsteen-Franklin

Prof. Dominik Havsteen-Franklin is a Ppofessor of practice (Arts Therapies) at Brunel University, with a Ph.D. in art psychotherapy and metaphor. He is also the head of the International Centre for Arts Psychotherapies Training (ICAPT) for Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust, vice president for the European Federation of Art Therapy and a member of the Council for the British Association of Art Therapists.

Claire Grant

Claire Grant is the Trust Head of Arts Psychotherapies, Operational Lead Arts Psychotherapist and Chair of the National NHS Arts Therapies Leads Forum at Central North West London Foundation Trust.

Alain Renau

Dr. Alain Renaud is a senior lecturer at Vallais School of Art, Switzerland. As a member of the Analema Group, his research practice centres around ambisonic and spatial sound, networked participatory art and mixed reality.

Daniel Hignell-Tully

Dr. Daniel Hignell-Tully is a researcher and artist, with a research focus on participatory arts. At the University of Greenwichand Guildhall, he lectures on and researches participatory arts practices.

References

- All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing. 2017. Creative Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing. Report. London: All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing.

- Aron, A., E. N. Aron, and D. Smollan. 1992. “Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale and the Structure of Interpersonal Closeness.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 63 (4): 596.

- Ascott, R. 1990. “Is There Love in the Telematic Embrace?” Art Journal 49 (3): 241–247.

- Ashida, S., and C. A. Heaney. 2008. “Social Networks and Participation in Social Activities at a New Senior Center: Reaching Out to Older Adults Who Could Benefit the Most.” Activities, Adaptation & Aging 32: 40–58. doi:10.1080/01924780802039261.

- Bailey, M., R. Cao, T. Kuchler, J. Stroebel, and A. Wong. 2018. “Social Connectedness: Measurement, Determinants, and Effects.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 32 (3): 259–280.

- Barad, K. 1996. “Meeting the Universe Halfway: Realism and Social Constructivism Without Contradiction.” In Feminism, Science and the Philosophy of Science, edited by L. H. Nelson, and J. Nelson, 161–194. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway. Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Bardin, A.. 2021. “Simondon Contra New Materialism: Political Anthropology Reloaded.” Theory, Culture & Society 38: 026327642110120. doi:10.1177/02632764211012047.

- Bennington, R., A. Backos, J. Harrison, A. E. Reader, and R. Carolan. 2016. “Art Therapy in Art Museums: Promoting Social Connectedness and Psychological Well-Being of Older Adults.” The Arts in Psychotherapy 49: 34–43.

- Berkman, L. F., and S. L. Syme. 1979. “Social Networks, Host Resistance, and Mortality: A Nine-Year Follow-up Study of Alameda County Residents.” American Journal of Epidemiology 109: 186–204. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674.

- Bigby, C., and S. Anderson. 2021. “Creating Opportunities for Convivial Encounters for People with Intellectual Disabilities: “It looks like an Accident.” Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 46 (1): 45–57.

- Bigby, C., and I. Wiesel. 2021. “Performance, Purpose, and Creation of Encounter Between People with and Without Intellectual Disabilities.” Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability 46 (1): 1–5. doi:10.3109/13668250.2020.1856107

- Biocca, F., C. Harms, and J. K. Burgoon. 2003. “Toward a More Robust Theory and Measure of Social Presence: Review and Suggested Criteria.” Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 12 (5): 456–480. doi:10.1162/105474603322761270.

- Braidotti, R. 2013. The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

- Bullack, A., C. Gass, U. M. Nater, and G. Kreutz. 2018. “Psychobiological Effects of Choral Singing on Affective State, Social Connectedness, and Stress: Influences of Singing Activity and Time Course.” Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 12: 223.

- Campos-Castillo, C., and S. Hitlin. 2013. “Copresence: Revisiting a Building Block for Social Interaction Theories.” Sociological Theory 31 (2): 168–192. doi:10.1177/0735275113489811.

- Couldry, N. 2004. “Theorising Media as Practice.” Social Semiotics 14 (2): 115–132. doi:10.1080/1035033042000238295.

- Dadswell, A., H. Bungay, C. Wilson, and C. Munn-Giddings. 2020. “The Impact of Participatory Arts in Promoting Social Relationships for Older People within Care Homes.” Perspectives in Public Health 140 (5): 286–293.

- Dadswell, A., C. Wilson, H. Bungay, et al. 2017. “The Role of Participatory Arts in Addressing the Loneliness and Social Isolation of Older People: A Conceptual Review of the Literature.” Journal of Arts & Communities 9 (2): 109–128. doi:10.1386/jaac.9.2.109_1.

- Debord, G. 1977. Society of the Spectacle. Detroit: Black & Red.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Delitz, H. 2021. “Life as the Subject of Society: Critical Vitalism as Critical Social Theory.” In Critical Theory and New Materialisms, edited by H. Rosa, C. Henning, and A. Bueno, 107–122. London: Routledge.

- Fancourt, D., and R. Perkins. 2018. “The Effects of Mother–Infant Singing on Emotional Closeness, Affect, Anxiety, and Stress Hormones.” Music & Science 1: 2059204317745746.

- Fox, N. J., and P. Alldred. 2015. “New Materialist Social Inquiry: Designs, Methods and the Research-Assemblage.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 18 (4): 399–414. doi:10.1080/13645579.2014.921458.

- Fox, A. and H. Macpherson. (2015). Inclusive Arts Practice and Research: A Critical Manifesto. London; New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Fox, F. E., M. Morris, and N. Rumsey. 2007. Doing Synchronous Online Focus Groups with Young People: Methodological Reflections. Qualitative Health Research 17(4): 539–547.

- Gallant, K., B. Hamilton-Hinch, C. White, F. Litwiller, and H. Lauckner. 2016, October 8. “Removing the Thorns’: The Role of the Arts in Recovery for People with Mental Health Challenges.” Arts & Health 11 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1080/17533015.2017.1413397.

- Gamble, C. N., J. S. Hanan, and T. Nail. 2019. “What is New Materialism?” Angelaki 24 (6): 111–134.

- Gingrich, O., U. Tymoszuk, E. Emets, A. Renaud, and D. Negrao. 2019, July. “KIMA–The Voice: Participatory art as means for social connectedness.” In Proceedings of EVA London 2019. BCS Learning & Development.

- Giordano, G. N., and M. Lindstorm. 2010. “The Impact of Changes in Different Aspects of Social Capital and Material Conditions on Self-Rated Health Over Time: A Longitudinal Cohort Study.” Social Science & Medicine 70 (5): 700–710. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.044.

- Goffman, E. 1966. Behavior in Public Places. New York: Free Press.

- Golańska, D. 2017. Affective Connections: Towards a new Materialist Politics of Sympathy. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Goss, J., and T. Leinbach. 1996. “Focus Groups as Alternative Research Practice: Experience with Transmigrants in Indonesia.” Area 28 (2): 115–123.

- Haraway, D. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599. doi:10.2307/3178066

- Haraway, D. 1991. Simians, Cyborgs and Women. The Reinvention of Nature. London: Free Association Books.

- Hiltunen, M., E. Mikkonen, and M. Laitinen. 2020. Metamorphosis: Interdisciplinary Art-Based Action Research Addressing Immigration and Social Integration in Northern Finland. In Learning through art: International perspectives (pp. 380–405). International Society for Education Through Art (InSEA).

- International Society for Presence Research. 2000. The Concept of Presence: Explication Statement. Retrieved from https://ispr.info/.

- Kember, S., and J. Zylinska. 2012. Life After New Media: Mediation as Vital Process. Cambridge, Mass.; London: MIT Press.

- Knox, S. S., and K. Uvnas-Moberg. 1998. “Social Isolation and Cardiovascular Disease: An Atherosclerotic Pathway?” Psychoneuroendocrinology 23: 877–890. doi:10.1016/S0306-4530(98)00061-4

- Lagacé, M., C. Briand, and J. Desrosiers. 2016. “A Qualitative Exploration of a Community-Based Singing Activity on the Recovery Process of People Living with Mental Illness.” British Journal of Occupational Therapy 79 (3): 178–187. doi:10.1177/0308022615599171.

- Latour, B. 1999. On Recalling ANT’ in Actor Network Theory and After, edited by John Law, and John Hassard, 15–20. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lee, R. M., and S. B. Robbins. 1995. “Measuring Belongingness: The Social Connectedness and the Social Assurance Scales.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 42: 232–241. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.42.2.232.

- Lombard, M., and T. Ditton. 1997. “At the Heart of It All: The Concept of Presence.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 3: 0–0. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00072.x.

- Lupton, D., and S. Maslen. 2018. “The More-Than-Human Sensorium: Sensory Engagements with Digital Self-Tracking Technologies.” The Senses and Society 13 (2): 190–202. doi:10.1080/17458927.2018.1480177.

- Mental Health Foundation. 2011. An Evidence Review of the Impact of Participatory Arts on Older People Report. London: Mental Health Foundation. September 2011.

- Minsky, M. 1980. “Telepresence.” Omni 2 (9): 44–52.

- Moore, T., K. McKee, and P. McLoughlin. 2015. “Online Focus Groups and Qualitative Research in the Social Sciences: Their Merits and Limitations in a Study of Housing and Youth.” People, Place and Policy 9 (1): 17–28.

- Montgomery, L., B. Kelly, U. Campbell, et al. 2022. “'Getting our Voices Heard in Research: A Review of Peer Researcher’s Roles and Experiences on a Qualitative Study of Adult Safeguarding Policy.” Research Involvement and Engagement 8: 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-022-00403-4

- Nevay, S., L. Robertson, C. S. Lim, and W. Moncur. 2019. “Crafting Textile Connections: A Mixed-Methods Approach to Explore Traditional and e-Textile Crafting for Wellbeing.” The Design Journal 22(sup1): 487–501.

- O’Rourke, H. M., and S. Sidani. 2017. “Definition, Determinants, and Outcomes of Social Connectedness for Older Adults: A Scoping Review.” Journal of Gerontological Nursing 43 (7): 43–52. doi:10.3928/00989134-20170223-03.

- Parikka, J. 2012. “New Materialism as Media Theory: Medianatures and Dirty Matter.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 9 (1): 95100.

- Perkins, R., A. Mason-Bertrand, U. Tymoszuk, N. Spiro, K. Gee, and A. Williamon. 2021. “Arts Engagement Supports Social Connectedness in Adulthood: Findings from the HEartS Survey.” BMC Public Health 21 (1208): 1–15. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11233-6.

- Scott, D. 2014. Gilbert Simondon's Psychic and Collective Individuation. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Secker, J., K. Heydenrych, and L. Kent. 2018. “Why art? Exploring the Contribution to Mental Well-Being of the Creative Aspects and Processes of Visual art-Making in an Arts and Mental Health Course.” Arts & Health 10 (1): 72–84. doi:10.1080/17533015.2017.1326389.

- Seeman, T. E., G. A. Kaplan, L. Knudsen, R. Cohen, and J. Guralnik. 1987. “Social Network Ties and Mortality among Tile Elderly in the Alameda County Study.” American Journal of Epidemiology 126: 714–723. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114711.

- Serafinelli, E., and M. Villi. 2017. “Mobile Mediated Visualities an Empirical Study of Visual Practices on Instagram.” Digital Culture & Society 3 (2): 165–182. doi:10.14361/dcs-2017-0210

- Sheridan, T. 1992. “Musings on Telepresence and Virtual Presence.” Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 1: 120–126. doi:10.1162/pres.1992.1.1.120

- Toepel, V. 2013. “Ageing, Leisure, and Social Connectedness: How Could Leisure Help Reduce Social Isolation of Older People?” Social Indicators Research 113: 355–372.

- Turner-Cobb, J. M., S. E. Sephton, C. Koopman, J. Blake-Mortimer, and D. Spiegel, 2000. “Social Support and Salivary Cortisol in Women with Metastatic Breast Cancer.” Psychosomatic Medicine, 62: 337–345. doi:10.1097/00006842-200005000-00007

- Van Bel, D. T., K. C. Smolders, W. A. Ijsselsteijn, and Y. A. W. De Kort. 2009. “Social Connectedness: Concept and Measurement.” In Intelligent environments 2009, 67–74. IOS Press. doi:10.3233/978160750034667