Abstract

Aim: To evaluate health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in cemiplimab-treated patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma (laBCC). Materials & methods: Eighty-four patients with laBCC received cemiplimab 350 mg every 3 weeks (up to 9 cycles). HRQoL was assessed using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Core 30 (QLQ-C30) and Skindex-16 questionnaires at baseline and each cycle. Mixed-effects repeated-measures models evaluated change from baseline across cycles. Results: Clinically meaningful improvement or maintenance was reported by 62–90% of patients on QLQ-C30 scales and by approximately 80% on Skindex-16 scales at Cycle 2, with consistent results at Cycle 9 except fatigue. Conclusion: Most cemiplimab-treated patients with laBCC reported improvement or maintenance of HRQoL with low symptom burden except fatigue.

Clinical Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03132636, registered 28 April 2017.

Plain language summary

Locally advanced basal cell carcinoma (laBCC) is a type of skin cancer that has the potential to invade surrounding tissues including bone, cartilage, nerve and muscle. Cemiplimab-rwlc is approved in the US for patients with laBCC following a therapy called hedgehog inhibitor (HHI) treatment or for whom HHIs are not appropriate. In a Phase II clinical trial, intravenous (in the vein) cemiplimab 350 mg every 3 weeks for up to nine treatment cycles resulted in clinically meaningful antitumor activity in patients with laBCC who progressed on or were intolerant to HHIs.

This analysis evaluated health-related quality of life, symptom burden, emotions and functional status in these patients using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Core 30 (QLQ-C30) and Skindex-16 questionnaires. Baseline scores (scores at the start of the clinical trial) showed moderate to high levels of functioning and low symptom burden that, except for fatigue, were maintained or improved over the course of cemiplimab treatment. These results show that despite the presence of fatigue, health-related quality of life and functional status were maintained with cemiplimab across the study duration.

TWEETABLE ABSTRACT

In patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma treated with cemiplimab every 3 weeks for nine treatment cycles, health-related quality of life and functional status were maintained despite the presence of fatigue.

In a Phase II trial, intravenous cemiplimab 350 mg every 3 weeks for up to nine treatment cycles resulted in clinically meaningful antitumor activity in patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma who progressed on or were intolerant to hedgehog inhibitors.

Since an important component in cancer clinical trials is the measurement of patient-centric outcomes, this analysis evaluated patient-reported health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among participants in the clinical trial.

HRQoL was evaluated using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ-C30), which consists of a global health status/quality of life (GHS/QoL) scale, five functional scales and eight symptom scales; and the Skindex-16, which assesses the impact of skin disease on HRQoL based on symptom, emotional and functional subscales.

Mixed-effects repeated-measures models were used to estimate overall least-squares (LS) mean (95% confidence interval [CI]) change from baseline across Cycles 2–9; absolute changes ≥10 points from baseline were considered clinically meaningful.

Overall changes from baseline indicated maintenance for QLQ-C30 GHS/QoL, functioning and symptom scales, except for clinically meaningful worsening of fatigue (LS mean change: 12.0; 95% CI: 4.3–19.6).

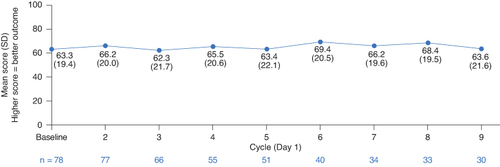

Clinically meaningful improvement or maintenance on QLQ-C30 GHS/QoL, functioning and symptom scales were reported at Cycle 2 by 88%, 69–81% and 62–90% of patients, respectively, with similar proportions at Cycle 6 (∼1 year of treatment) and consistent results at Cycle 9 except for fatigue.

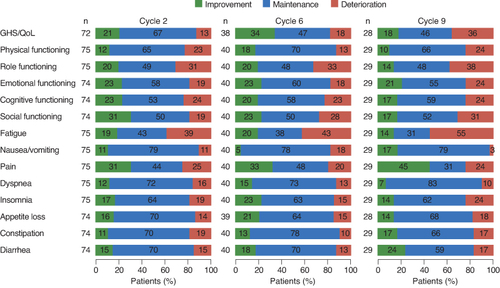

On the Skindex-16, overall change showed clinically meaningful improvement on the emotional subscale (LS mean change, -13.8; 95% CI: -21.4 to -6.2), with maintenance on symptom and functional subscales; clinically meaningful improvement or maintenance across all three subscales was reported by approximately 80% of patients at Cycle 2 that was generally maintained at Cycles 6 and 9.

These results show that most patients with laBCC treated with cemiplimab reported clinically meaningful improvement or maintenance in GHS/QoL and functioning while maintaining low symptom burden, except for fatigue.

1. Background

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common human malignancy, and estimates suggest up to 4.3 million cases are diagnosed per year in the US [Citation1]. While BCC is generally associated with favorable outcomes using surgery or other localized treatments (radiotherapy or topical agents), a small proportion of patients develop locally advanced disease (i.e., laBCC). Patients who are no longer eligible for curative surgery or radiotherapy may require systemic therapy with inhibitors of the hedgehog signaling pathway, which is homeostatic in specific cells and tissues but aberrantly activated in BCC [Citation2]. However, intolerance to or disease progression on hedgehog inhibitors (HHIs) occurs in a proportion of these patients [Citation2].

Although few studies have comprehensively evaluated the disease burden in laBCC, patients report impairment of health-related quality of life (HRQoL), daily function and emotional well-being [Citation3,Citation4]. Treatment effects on HRQoL have been reported for first-line systemic treatment with HHIs [Citation5–8], but data are lacking in other treatment settings of laBCC.

Cemiplimab (cemiplimab-rwlc in the US), a fully human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that acts as a checkpoint inhibitor targeting programmed cell death-1 [Citation9], received full approval from the US FDA and the European Medicines Agency for treatment of laBCC and accelerated approval for metastatic BCC in patients previously treated with an HHI or for whom HHIs are not appropriate [Citation10,Citation11]. In a Phase II trial in patients with laBCC who progressed on or were intolerant to HHIs, cemiplimab resulted in clinically meaningful antitumor activity. The overall response rate (complete + partial) based on Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST 1.1) was 31.0%, and 48.8% had stable disease [Citation12]. Cemiplimab is also approved for the treatment of patients with metastatic or locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma who are not candidates for curative surgery or curative radiation, and as monotherapy or in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy for first-line treatment of patients with metastatic or locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer who are not candidates for surgical resection or definitive chemoradiation, and are negative for actionable molecular markers.

From multiple healthcare stakeholder perspectives, an important component in cancer clinical trials is the measurement of patient-centric outcomes [Citation13,Citation14], especially since patient experience data are often used by clinicians and patients for making treatment decisions. Regulatory authorities, including the FDA, also note the importance of considering the patient’s perspective of the effects of therapy on HRQoL when evaluating therapies [Citation15–17]. The objective of this analysis was to evaluate, HRQoL, functioning and symptom burden in patients with laBCC who were treated with cemiplimab.

2. Materials & methods

2.1. Study design & population

This was an open-label, nonrandomized, multicenter, Phase II clinical trial that evaluated cemiplimab monotherapy for treatment of adult patients (≥18 years old) with metastatic BCC or laBCC (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03132636). The current patient-reported outcome (PRO) analyses use data from an interim analysis of the subset of patients who were diagnosed with laBCC; the metastatic cohort was not included because the timepoint for the primary efficacy analysis (according to the statistical analysis plan) had not yet been reached. Patients were required to have histologically confirmed disease and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status ≤1, and were not candidates for HHI therapy due to progression of disease on or intolerance to prior HHI therapy or had no better than stable disease after 9 months on HHI therapy. Complete inclusion and exclusion criteria and study results for clinical outcomes have been previously described [Citation12].

2.2. Treatment

Patients were treated with up to nine cycles of intravenous cemiplimab 350 mg every 3 weeks until the 93-week treatment period was completed or until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or withdrawal of consent, whichever occurred first. Cycle length was 9 weeks for Cycles 1–5 and 12 weeks for Cycles 6–9.

2.3. Patient-reported outcomes

Patient-reported HRQoL was evaluated and collected as a predefined secondary end point at baseline and day 1 of each treatment cycle using paper versions of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ-C30, version 3.0) [Citation18] and Skindex-16 [Citation19] questionnaires. The QLQ-C30 is a general oncology PRO measure that consists of a global health status/quality of life (GHS/QoL) scale, five functional scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional and social), and eight symptom scales (fatigue, pain, nausea/vomiting, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation and diarrhea) with a recall period of “during the past week”. Functioning and symptoms are assessed on a four-point Likert scale, and GHS/QoL is assessed on a seven-point Likert scale. Scores are subsequently transformed to a 0–100 scale, with high scores on GHS/QoL and functional scales and low scores on symptom scales reflecting better outcomes. A commonly used change in scale score of ≥10 points absolute value is considered clinically meaningful [Citation20–22].

The Skindex-16 is a dermatology-specific PRO instrument that assesses the impact of skin disease on patients’ HRQoL based on symptom, emotional and functional subscales [Citation19]. It consists of 16 items (four questions on the symptom subscale, seven on the emotional subscale and five on the functional subscale) that measure the level of bother over the previous week on a seven-point Likert scale (0 = never bothered to 6 = always bothered). Scores are transformed to a 0–100 scale with lower scores on all subscales reflecting better outcomes. An absolute change of ≥10 points is considered clinically meaningful [Citation23].

2.4. Statistical analysis

The population evaluated consisted of the full analysis set of the patients with laBCC who passed screening and were enrolled. Completion rates for both the QLQ-C30 and Skindex-16 were calculated among those patients who were expected to complete the instrument (i.e., alive and on study treatment). Mixed-model repeated-measures (MMRM) analysis with a missing-at-random (MAR) assumption was used to estimate least-squares (LS) mean change from baseline with a 95% confidence interval (CI) on all scales of the QLQ-C30 and Skindex-16 for patients with baseline and at least one postbaseline value for both instruments. No imputations were made for missing data; scores of domains with missing items were calculated as per the EORTC scoring algorithm (i.e., ≥50% of the items were required to be answered in order to calculate the domain score) [Citation24]. Overall changes from baseline were evaluated across Cycles 2–9. The covariates included in the model were time, baseline value, age group, sex, ECOG performance status, number of prior systemic therapies, geographic region and time by baseline PRO scores. Two-sided nominal p-values were calculated, with no adjustments made for multiple comparisons. Significance testing was set at α = 0.05.

A responder analysis was also conducted in patients with nonmissing data to determine the proportions of patients who reported clinically meaningful improvement or deterioration from baseline, or maintenance at Cycles 2, 6 and 9; Cycle 6 represents approximately 1 year (54 weeks) of treatment. An absolute change from baseline ≥10 points was considered clinically meaningful for both instruments, and maintenance was defined as neither improvement nor deterioration that was clinically meaningful.

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Patient population

A total of 84 patients with laBCC met the entry criteria and were enrolled, at data cut off of 20 May 2021. Patients were mostly male (66.7%) with a median age of 70 years (). The head and neck region was the primary tumor site in most patients (89.3%), and the most frequent reason for discontinuation of prior HHI therapy was disease progression (71.4%) ().

Table 1. Patient characteristics at baseline (N = 84).

In the total laBCC cohort, baseline completion rates for the QLQ-C30 and Skindex-16 were >90% in all scales. Postbaseline completion rates were >80% through Cycle 7 among the patients who completed the baseline assessment, and decreased to approximately 55% by the end of treatment.

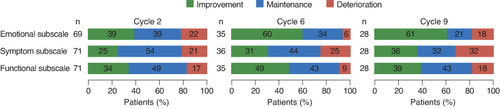

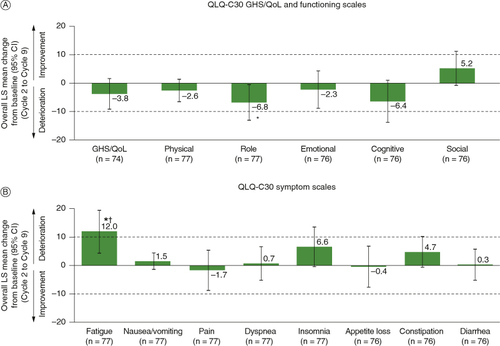

3.2. QLQ-C30

Baseline scores on the QLQ-C30 showed moderate to high levels of functioning and low symptom burden (), which were slightly better than QLQ-C30 reference values for overall patients with cancer [Citation25] but poorer than reference values for a general European population [Citation26]. In the MMRM analysis, the overall change from baseline across the study period showed that GHS/QoL and the majority of functional scale scores were maintained (A). Symptom scale scores, with the exception of fatigue, were also maintained (B). For fatigue, the LS mean change of 12.0 (95% CI: 4.3–19.6) indicated a clinically meaningful and statistically significant worsening relative to baseline.

Figure 1. Baseline scores on the QLQ-C30 among patients in the full analysis set who had baseline and at least one postbaseline assessment, relative to reference values for general patients with cancer [Citation25] and a general population derived from six European studies..

![Figure 1. Baseline scores on the QLQ-C30 among patients in the full analysis set who had baseline and at least one postbaseline assessment, relative to reference values for general patients with cancer [Citation25] and a general population derived from six European studies..](/cms/asset/d46fe10c-ce96-4d43-81aa-667c932e3431/ifon_a_2358670_f0001_c.jpg)

Figure 2. Overall change from baseline (MMRM) on the QLQ-C30 (A) GHS and functioning scales, and (B) symptom scales among patients in the full analysis set who had baseline and at least one postbaseline assessment. Broken horizontal lines indicate threshold of clinically meaningful change.

*Nominal p < 0.05 versus baseline. †Clinically meaningful change.

CI: Confidence interval; GHS/QoL: Global health status/quality of life; LS: Least squares; MMRM: Mixed-model repeated measures; QLQ-C30: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30.

Mean as-observed QLQ-C30 GHS/QoL scores at each evaluated timepoint showed that patient-reported HRQoL was maintained across the study duration ().

Figure 3. QLQ-C30 GHS/QoL score by treatment cycle in the full analysis set. Cycle length was 9 weeks for Cycles 1–5 and 12 weeks for Cycles 6–9.

GHS/QoL: Global health status/quality of life; QLQ-C30: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30; SD: Standard deviation.

In the responder analysis, the majority of patients at Cycle 2 reported clinically meaningful improvement or maintenance on GHS/QoL (88%) and functional scales (69–81%), and for all symptoms, which ranged from 62% for fatigue to 90% for nausea/vomiting (). After approximately 1 year of treatment (Cycle 6), the proportion of patients who reported clinically meaningful improvement or maintenance in symptoms was 58–91%, similar to Cycle 2 (). Responder analysis findings at Cycle 9 were generally consistent with those observed at Cycles 2 and 6 except for fatigue, with 45% of patients reporting improvement or maintenance.

Figure 4. Proportion of patients who reported clinically meaningful improvement, clinically meaningful deterioration, or maintenance on the QLQ-C30 in the full analysis set who had baseline and at least one postbaseline assessment. Cycle length was 9 weeks for Cycles 1–5 and 12 weeks for Cycles 6–9. Totals may exceed 100% due to rounding.

GHS/QoL: Global health status/quality of life; QLQ-C30: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30.

On the key symptom of pain, approximately a third of patients at Cycle 2 (31%) and Cycle 6 (33%) reported clinically meaningful improvement, and approximately half reported maintenance (44% at Cycle 2, 48% at Cycle 6) (). At Cycle 9, more patients reported a clinically meaningful improvement (45%) and fewer reported maintenance (31%). At all three cycles (cycles 2, 6 and 9), approximately one-quarter of patients reported a clinically meaningful worsening ().

3.3. Skindex-16

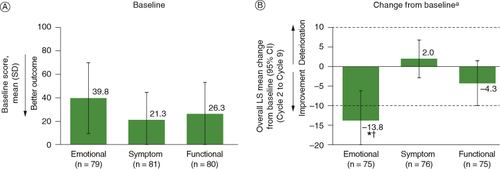

Among the three subscales of the Skindex-16, patients reported the greatest impact at baseline on the emotional subscale (A). This subscale also showed an overall clinically meaningful and statistically significant improvement in the MMRM analysis, with an LS mean change from baseline of -13.8 (95% CI: -21.4 to -6.2). Both the symptom and functional subscales were characterized by overall maintenance (no clinically meaningful change) (B). A clinically meaningful improvement on the emotional subscale was observed as early as Cycle 2 and was maintained until Cycle 9 (data not shown).

Figure 5. (A) Baseline scores, and (B) overall change from baseline (MMRM) on the Skindex-16 among patients in the full analysis set who had baseline and at least one postbaseline assessment.

*Nominal p < 0.05 versus baseline. †Clinically meaningful change. aBroken horizontal lines indicate threshold of clinically meaningful change.

CI: Confidence interval; LS: Least squares; MMRM: Mixed-model repeated measures; SD: Standard deviation.

In the responder analysis, clinically meaningful improvement or maintenance across all three subscales were reported by approximately 80% of patients at Cycle 2, and were generally sustained at Cycle 6 (75–94%) and Cycle 9 (68–82%) ().

4. Discussion

This analysis expands on previous clinical trial results and shows that, in addition to objective outcomes of clinically meaningful antitumor activity in patients with laBCC [Citation12], treatment with cemiplimab provides benefits of importance to patients in their daily life. These benefits include maintenance of HRQoL and moderate to high levels of functioning while also preserving low symptom burden, with the exception of fatigue. In patients with available data, the benefits were maintained at 1 year (six treatment cycles) and up to almost 2 years (nine treatment cycles).

The low symptom burden, as indicated by scores on the QLC-C30 and Skindex-16 scales, was consistent with the generally favorable safety and tolerability profile of cemiplimab in patients with laBCC [Citation12]. The presence and clinically meaningful worsening of fatigue was not surprising, given that fatigue was not only the most frequent treatment-related adverse event reported with cemiplimab [Citation12], but is also a common adverse event in clinical trials of patients with advanced BCC [Citation2]. Despite the overall clinically meaningful deterioration in fatigue, improvement or maintenance of fatigue scores was still reported by 45–62% of patients at Cycles 2, 6 and 9, suggesting there may be a subpopulation of patients who are more severely affected by fatigue. Given the nonrandomized nature of the trial, it could not be established whether deterioration in fatigue resulted from treatment or disease progression. Nevertheless, it is plausible that fatigue could have contributed to some of the observed deterioration in GHS/QoL, as fatigue has been shown to be a primary driver of GHS/QoL on the QLQ-C30 in patients with cancer initiating treatment [Citation27]. These observations suggest that such relationships may be an area for future research in those with laBCC. While it has also been reported that fatigue limits the ability to perform daily activities in patients with laBCC [Citation4], most patients in the current study reported improvement or maintenance of physical functioning throughout the study period. Indeed, most patients reported improvement or maintenance on all functional scales through the study duration. While moderate to high levels of functioning were reported at baseline, these levels were consistent with the inclusion criterion of ECOG performance status 0 or 1.

Results on the Skindex-16 showed that the greatest disease impact at baseline was on the emotional subscale, consistent with patient reports of the importance of emotional well-being in laBCC [Citation3,Citation4,Citation28]. The greatest benefits during treatment were also observed on the emotional subscale, with regard to both change from baseline and the proportion of patients who reported improvement or maintenance. While most patients reported improvement or maintenance on functional and symptom subscales, only for the emotional subscale was the change from baseline both clinically meaningful and statistically significant. Similar observations for clinically meaningful improvements on the emotional subscale, but not the functional or symptom subscales, have been reported in patients with laBCC treated with the HHI vismodegib as first-line treatment [Citation5].

Overall, maintenance of patient-reported HRQoL and functioning was consistent with that previously reported in clinical trials of patients with laBCC treated with HHIs [Citation5,Citation8,Citation29]. This consistency suggests that, even though patients in the current study previously progressed on or were intolerant to HHIs, treatment with cemiplimab provides benefits of importance to patients with respect to functioning, symptom burden and HRQoL.

Several study limitations should be noted, including that this study was single arm and open label. Similarly, while PROs were pre-specified secondary end points, and all analyses were described in a PRO statistical analysis plan, these analyses are hypothesis-generating given the nature of the trial design. The small sample size, especially at the final cycles, also represents a limitation, as does the fact that the MMRM analysis used a MAR assumption, which may not be true for all patients. Data after treatment discontinuation, especially due to disease progression, may not be MAR, and thus may not be optimally modeled under MAR where the model estimates missingness based on patients who are still on treatment. However, it could be argued that the last observed values before discontinuation may already indicate progression/worsening and are likely to be relatively poor, and thus the inferences of MMRM under the MAR assumption may be a conservative estimate of change from baseline. Additionally, PRO results were not stratified by tumor location. Although tumor location may affect HRQoL, as patients with head or neck lesions generally report worse pretreatment HRQoL than those with lesions in other areas [Citation6], there were only nine patients with lesions in locations other than the head or neck.

5. Conclusion

As laBCC typically affects an older population, maintenance of function with low symptom burden conveys clinically relevant benefits when associated with clinical response. During treatment with cemiplimab, the patient-reported benefits in maintaining HRQoL and function complement the objective clinical tumor response previously reported for cemiplimab as second-line treatment for patients with laBCC who progress on or are intolerant to HHIs, or for whom HHI therapy is not appropriate. Patients also reported maintenance of a low symptom burden except for fatigue; yet, despite the presence of fatigue, functional status was maintained across the study duration. These results support and expand the treatment effects of cemiplimab in patients with laBCC.

Author contributions

PR LaFontaine, G Konidaris, K Mohan and E Coates conceived and designed the study. AJ Stratigos, KD Lewis, K Peris, O Bechter and A Sekulic recruited patients and collected the data. C-I Chen, C Ivanescu, J Harnett, V Mastey, M Reaney, C Daskalopoulou, PR LaFontaine, G Konidaris, D Bury, S-Y Yoo, K Mohan, E Coates, T Bowler and MG Fury conducted data analysis. All authors had full access to and verified the data, contributed to the data interpretation, and provided critical review, revision and approval of the manuscript.

Financial disclosure

This study was funded by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Sanofi. AJ Stratigos reports research support from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genesis Pharma and Novartis. C-I Chen, V Mastey, S-Y Yoo, K Mohan, E Coates and MG Fury report stock and other ownership interests at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. C Ivanescu, M Reaney and C Daskalopoulou report stock and other ownership interests at IQVIA. KD Lewis reports research funding from Genentech and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. J Harnett reports stock and other ownership interests at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Pfizer Inc. PR LaFontaine reports stock and other ownership interests at Applied Genetic Technologies, Neos Therapeutics and Sanofi. G Konidaris and D Bury report stock and other ownership interests at Sanofi. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Writing disclosure

Medical writing support under the direction of the authors was provided by E. Jay Bienen and funded by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Sanofi according to Good Publication Practice guidelines.

Ethical conduct of research

The study protocol and all amendments were approved by the appropriate institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each participating study site. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Informed consent disclosure

All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients, their families, all other investigators and all investigational site members involved in this study.

Competing interests disclosure

AJ LaFontaine reports advisory board or steering committee roles with Janssen Cilag, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Roche, and Sanofi; C-I Chen, V Mastey, S-Y Yoo, K Mohan, E Coates and MG Fury report employment at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; C Ivanescu, M Reaney and C Daskalopoulou report employment at IQVIA;. K Peris reports advisory board roles with AbbVie, Almirall, Galderma, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi and Sun Pharma outside the submitted work. O Bechter reports advisory board roles with Almirall, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi and Ultimovacs. J Harnett reports employment at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; PR LaFontaine reports employment at Sanofi, G Konidaris and D Bury report employment at Sanofi. T Bowler reports being an employee of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. at the time of this study, and is currently employed by Pfizer Inc. A Sekulic reports advisory roles with Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Roche.

The authors have no other competing interests or relevant affiliations with any organization or entity with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Data availability statement

Qualified researchers may request access to study documents (including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form and statistical analysis plan) that support the methods and findings reported in this manuscript. Individual anonymized participant data will be considered for sharing once the product and indication has been approved by major health authorities (e.g., US FDA, European Medicines Agency, Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency, etc.), if there is legal authority to share the data, and there is not a reasonable likelihood of participant re-identification. Submit requests to https://vivli.org/.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Skin Cancer Foundation. Skin cancer facts. http://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancerinformation/skin-cancer-facts

- Migden MR, Chang ALS, Dirix L, et al. Emerging trends in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;64:1–10. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.12.009

- Mathias SD, Chren MM, Colwell HH, et al. Assessing health-related quality of life for advanced basal cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma nevus syndrome: development of the first disease-specific patient-reported outcome questionnaires. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(2):169–176. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.5870

- Steenrod A, Smyth E, Bush E, et al. A qualitative comparison of symptoms and impact of varying stages of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5(3):183–199. doi:10.1007/s13555-015-0081-6

- Hansson J, Bartley K, Karagiannis T, et al. Assessment of quality of life using Skindex-16 in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma treated with vismodegib in the STEVIE study. Eur J Dermatol. 2018;28(6):775–783. doi:10.1684/ejd.2018.3448

- Villani A, Fabbrocini G, Cappello M, et al. Real-life effectiveness of vismodegib in patients with metastatic and advanced basal cell carcinoma: characterization of adverse events and assessment of health-related quality of life using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) test. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019;9(3):505–510. doi:10.1007/s13555-019-0303-4

- Migden MR, Khushalani NI, Chang ALS, et al. Cemiplimab in locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: results from an open-label, Phase II, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(2):294–305. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30728-4

- Dummer R, Gutzmer R, Migden MR, et al. Patient-reported quality of life (QOL) with sonidegib (LDE225) in advanced basal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(Suppl. 4):iv390. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdu344.41

- Burova E, Hermann A, Waite J, et al. Characterization of the anti-PD-1 antibody REGN2810 and its antitumor activity in human PD-1 knock-in mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16(5):861–870. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0665

- Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sanofi-Aventis US LLC. LIBTAYO® (cemiplimab-rwlc) injection, for intravenous use [prescribing information] 2021. https://www.regeneron.com/downloads/libtayo_fpi.pdf

- European Medicines Agency. Libtayo (cemiplimab) 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/libtayo

- Stratigos AJ, Sekulic A, Peris K, et al. Cemiplimab in locally advanced basal cell carcinoma after hedgehog inhibitor therapy: results from an open-label, Phase II, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(6):848–857. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00126-1

- Bhatnagar V, Hudgens S, Piault-Louis E, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in oncology clinical trials: stakeholder perspectives from the accelerating anticancer agent development and validation workshop 2019. Oncologist. 2020;25(10):819–821. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2020-0062

- Addario B, Geissler J, Horn MK, et al. Including the patient voice in the development and implementation of patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials [Research support, non-U.S. Gov't review]. Health Expect. 2020;23(1):41–51. doi:10.1111/hex.12997

- Kluetz PG, Slagle A, Papadopoulos EJ, et al. Focusing on core patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials: symptomatic adverse events, physical function, and disease-related symptoms. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(7):1553–1558. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2035

- European Medicines Agency. Appendix 2 to the guideline on the evaluation of anticancer medicinal products in man. The use of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures in oncology studies 2016. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/appendix-2-guideline-evaluation-anticancer-medicinal-products-man_en.pdf

- US Food and Drug Administration. Core patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials. Guidance for industry. Draft guidance. 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/149994/download

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376. doi:10.1093/jnci/85.5.365

- Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Sahay AP, et al. Measurement properties of Skindex-16: a brief quality-of-life measure for patients with skin diseases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5(2):105–110. doi:10.1177/120347540100500202

- King MT. The interpretation of scores from the EORTC quality of life questionnaire QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res. 1996;5(6):555–567. doi:10.1007/BF00439229

- Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, et al. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(1):139–144. doi:10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139

- Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G, et al. Quality, interpretation and presentation of European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire core 30 data in randomised controlled trials. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(13):1793–1798. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.05.008

- Chren MM, Sahay AP, Bertenthal DS, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes of treatments for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(6):1351–1357. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700740

- European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual 2001. https://www.eortc.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2018/02/SCmanual.pdf

- Scott NW, Fayers P, Aaronson NK, et al. EORTC QLQ-C30 reference values Brussels. EORTC Quality of Life Group, Belgium. 2008. https://www.eortc.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2018/02/reference_values_manual2008.pdf

- Hinz A, Singer S, Brahler E. European reference values for the quality of life questionnaire EORTC QLQ-C30: results of a German investigation and a summarizing analysis of six European general population normative studies. Acta Oncol. 2014;53(7):958–965. doi:10.3109/0284186X.2013.879998

- McCabe RM, Grutsch JF, Braun DP, et al. Fatigue as a driver of overall quality of life in cancer patients. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0130023. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0130023

- Konidaris G, Rofail D, Randall J, et al. Qualitative patient interviews to characterize the humanistic burden of advanced basal cell carcinoma following hedgehog inhibitor treatment. Las Vegas, Nevada.: Fall Clinical Dermatology Conference; 2021 October 21–24

- Migden MR. Quality of life for patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma treated with hedgehog signaling pathway inhibitors. J Clin Exp Dermatol Res. 2017;8(6):1000432. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000432