ABSTRACT

Using data from the National Sports and Society Survey (N = 3,993), this study described and analyzed U.S. adults’ reports of their youth sports experiences. We considered patterns in ever having played a sport regularly while growing up, ever having played an organized sport, and then relative likelihoods of having never played an organized sport, played and dropped out of organized sports, or played an organized sport continually while growing up. We used binary and multinomial logistic regressions to assess the relevance of generational, gender, racial/ethnic, socioeconomic status, and family and community sport culture contexts for youth sports participation experiences. Overall, the findings highlight general increases in ever playing organized sports and ever playing organized sports and dropping out across generations. Increasing levels of female sports participation, emerging disparities by socioeconomic statuses, and the continual salience of family and community cultures of sport for participation are also striking.

Résumé

À l’aide des données du National Sports and Society Survey (n = 3 993), cette étude a décrit et analysé les rapports des adultes américains sur leurs expériences sportives dans la jeunesse. Nous avons examiné les tendances concernant la pratique régulière d’un sport pendant l’enfance, la pratique d’un sport organisé et les probabilités relatives de n’avoir jamais pratiqué un sport organisé, d’avoir pratiqué et abandonné un sport organisé ou d’avoir pratiqué un sport organisé de façon continue pendant l’enfance. Nous avons utilisé des régressions logistiques binaires et multinomiales pour évaluer la pertinence des contextes générationnels, de genre, raciaux/ethniques, de statut socio-économique et de culture sportive familiale et communautaire pour les expériences de participation sportive des jeunes. Dans l’ensemble, les résultats révèlent une augmentation générale du nombre de personnes ayant déjà pratiqué un sport organisé et du nombre de personnes ayant déjà pratiqué un sport organisé et ayant abandonné le sport, d’une génération à l’autre. Les niveaux de participation sportive de plus en plus élevés chez les femmes, les disparités émergentes en fonction du statut socio-économique et l’importance continue des cultures sportives, familiales et communautaires pour la participation sont également frappants.

Youth sports participation is commonly thought to yield a multitude of physical, psychological, and social benefits – and access and support for it is widely recognized to be unequal (Black et al., Citation2022; Project Play, Citation2015; Sabo & Veliz, Citation2008; Zarrett & Veliz, Citation2021). But, despite some research that documents fairly steady increases in the number of children who have participated in sports since the 1950s in the U.S., historical trends of different aspects of sports participation (e.g., informal participation, formally organized sports participation, dropout rates), which may have differing implications, and their precipitating factors are not well understood (Knoester & Allison, Citation2022; Knoester & Randolph, Citation2019; Project Play, Citation2015, Citation2022; Wiggins, Citation2013). For instance, specific trends in having ever played a sport regularly, having ever played an organized sport, and having ever dropped out versus having played organized youth sports continually are not typically specified or disaggregated, over time (Knoester & Allison, Citation2023; Knoester & Fields, Citation2020; Nothnagle & Knoester, Citation2022; Project Play, Citation2015, Citation2022). These nuances are important to consider as historical changes are frequently assumed to have led to rises in organized, versus informal, sport participation – and there is some concern about the implications of such trends. Moreover, there have been mounting concerns expressed over dropout rates from sports participation (Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Knoester & Allison, Citation2022; Project Play, Citation2015, Citation2022; Zarrett & Veliz, Citation2021). But, there is relatively little empirical evidence – much less comprehensive evidence – that documents these trends and how they may be structured by generational experiences, gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES), and family and community sport cultures (Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Knoester & Allison, Citation2022; Knoester & Fields, Citation2020; Project Play, Citation2015, Citation2022; Sabo & Veliz, Citation2008).

Indeed, sports participation opportunities, and the extent to which youth commit to taking advantage of them, appear to look quite different these days when compared to the youth sports contexts in the U.S. that existed across previous generations. Expectations for players and coaches, definitions of and pressures for athletic success, and priorities placed upon investing in sports skill development and participation opportunities have all evolved. For instance, parents have appeared to have become more intensively involved in directing their children’s sports participation pursuits and specialized and organized sports opportunities have become more plentiful–albeit at higher costs – as part of a youth sports industry (Coakley, Citation2016; Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Project Play, Citation2022; Tompsett & Knoester, Citation2022; Tompsett et al., Citation2023). Seemingly, sports-linked social mobility opportunities have become highlighted and it is increasingly recognized that informal and formal sports investments that affect sports participation patterns have critical health, well-being, and social stratification implications (Albrecht & Strand, Citation2010; Heffer & Knoester, Citation2021; Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Hyde et al., Citation2020; Knoester & Randolph, Citation2019; Project Play, Citation2015). Nonetheless, young people with different background characteristics, across generations, have not been afforded the same opportunities and support to participate in sports. For example, research that focuses on gender often underscores the powerful impact that Title IX has had on the aspirations and activities of females. Analyses of race/ethnicity have commonly noted segregated and non-inclusive sports and society contexts. Studies that have scrutinized SES point to social class and parental education differences in especially organized sports (Cairney et al., Citation2015; Hartmann & Manning, Citation2016; Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Knoester & Fields, Citation2020; Zarrett & Veliz, Citation2021). The salience of family and community cultures of sport have also been highlighted – but few empirical estimates of their influence exist because they are not easily measured (Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Sabo & Veliz, Citation2008; Wheeler, Citation2012).

Therefore, this study aimed to build up the extant body of research on youth sports participation across generations and examine how gender, race/ethnicity, SES, and family and community cultures of sport structure opportunities and participation patterns in the U.S. To do so, we analyzed unique and comprehensive national survey data from a large sample of adults who reported on their youth sports experiences while growing up as part of their participation in hourlong surveys. First, we described patterns in adults’ recollections of ever having played a sport regularly (i.e., any informal or formal sport), ever having played organized sports, and ever having dropped out of organized sports (i.e., distinctions between never playing, playing and dropping out, or playing continually) while growing up. Then, we employed binary and multinomial logistic regression analyses to scrutinize how generational contexts (i.e. age when interviewed, linked to birth years in different decades), gender, race/ethnicity, SES (i.e., childhood social class and parental education), and family (e.g., reports of parent fandom and athleticism) and community (e.g., recollections of passions for sport in one’s community while growing up) cultures of sport, while growing up, patterned youth sports participation.

Our approach was especially innovative because we were able to draw from unparalleled one hour sports and society surveys with an opt-in quota sample of 4,000 U.S. adults that offer information about life history experiences (i.e., social status ascriptions at birth; self-reports of particular and typical family, community, and sports offering-linked contexts while growing up; childhood sports participation patterns from ages 6–18) across generations that are matched to different indicators of youth sports participation that are of great interest, instead of the typical annual reports about participation that are presented that frequently do not assess peoples’ experiences over time. We traced the experiences reported by adults who were born in the 1950ʹs through the 1990ʹs. We also went beyond common reports of youth sports participation that are only disaggregated by one or two characteristics and considered the combined implications of a variety of social factors with our logistic regression analyses. Central to this, was our ability to not only account for the social structuring influences of social statuses (e.g., age, gender, race/ethnicity, SES), but also our integration of unusual measures of family and community cultures of sport that tap powerful social forces that can direct sports participation – in addition to our inclusion of control variables that related to nativity, urbanicity, and family structures into our analyses (Project Play, Citation2015; Sabo & Veliz, Citation2008; Sutton & Knoester, Citation2022; Zarrett & Veliz, Citation2021).

Conceptual framework

Historical contexts and trends in the evolution of youth sports in the U.S

Historically, the term ‘youth sports’ has been widely applied. But, the expectations and demands placed on children often vary significantly depending on the sport context. Whether or not a sport is a formally organized activity is frequently key. Still, children may engage infrequently or regularly in sports offered in a variety of settings such as those provided through their schools, in community-based organizations, as part of private clubs that commonly charge high fees and demand year-round participation, or in informal games with other kids who live in their neighbourhoods. All of these sports activities generally fall under the broad umbrella of youth sports, yet they differ significantly in the ways they shape children’s development (Coakley, Citation2016; Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Knoester & Allison, Citation2022; Knoester & Randolph, Citation2019; Project Play, Citation2015; Sabo & Veliz, Citation2008). It is therefore important to consider some basic patterns in youth sports participation and how they may have emerged from historical circumstances and particular social contexts. Given the focus of the present study, we are particularly concerned with the patterns of and contexts for sports participation among U.S. youths born in the 1950ʹs-1990ʹs.

Prior to 1954, most organized sports for youth were provided by entities such as the YMCA. The YMCA was connected to religious organizations that were motivated to promote and intertwine sport and spiritual development. The number of children who participated in sports expanded rapidly during the 1950ʹs and 1960s, as members of the Baby Boom generation became involved in and enraptured by informal and formal sports (Coakley, Citation2016; Wiggins, Citation2013). State-sponsored and privately-funded organizations created new opportunities for young men and women to develop their athletic skills and engage in competition (Albrecht & Strand, Citation2010). By the early 1960ʹs, Little League baseball branches had been established in all 50 states and in many countries around the world (Wiggins, Citation2013).

Throughout the 1970ʹs, the number of youth sports programmes and participants continued to grow. Most commonly, children took part in local, neighbourhood-based programs that charged minimal fees. Practices and games were held in public parks or on school fields, overseen by volunteer coaches. As children entered adolescence, they often signed up to play for school teams that demanded little of them in terms of cost or parental involvement. Although athletes competed against their peers, the opportunities available to them were fairly homogenous. The point at which athletic pathways diverged tended to occur near the end of high school, when individuals decided if they were going to compete at the college level, if that opportunity was available to them, and, if so, for what type of programme (Coakley, Citation2016; Eckstein, Citation2017; Wiggins, Citation2013).

Conditions began to change in the 1980ʹs, when it became increasingly common for athletes, and their parents, to seek ways to distinguish themselves from potential competitors. At that point, cuts in government support for youth sports created opportunities for private entities to capture a larger share of the market. Alongside recreational leagues that had anchored the world of youth sports for decades, private leagues and tournaments attracted paying customers motivated to distinguish youth, and families, from their competitors. Early childhood specialization and year-round competition became normalized (Coakley, Citation2016; Eckstein, Citation2017).

This resulted in ‘the emergence and growth of privatized youth sports organized to promote progressive skills development through training and competition’ (Coakley, Citation2016, p. 88). Sports entrepreneurs capitalized on growing demand for supplemental training and competition. Increased attention was placed on the identification and development of athletes with the potential to become successful at the highest levels of their sport (Wright et al., Citation2019). Opportunities for individualized coaching, personal training, elite club participation, regional tournaments, and special events designed to attract college scouts expanded rapidly. At younger and younger ages, athletes were encouraged to sign up for activities with the potential to enhance their athletic profiles. The number of children who participated in sports apparently continued to grow throughout the 1980ʹs and 1990ʹs, with organizations and entrepreneurs driving that expansion (Coakley, Citation2016; Eckstein, Citation2017; Wiggins, Citation2013). Overall, organized youth sports programmes in the U.S. ‘evolved into an enterprise that stressed victories and the performance ethic, yet never stopped rationalizing their existence based on the lessons learned by children who worked hard to hone their talents’ (Wiggins, Citation2013, p. 72).

As youth sports developed into an industry, the demands placed on families also escalated (Coakley, Citation2006; Day, Citation2023; Quarmby, Citation2016; Schneider et al., Citation2018). Parents were required to provide more financial and logistical support for their offspring. These changes were exacerbated by shifting societal views about parenting. An intensification of parenting resulted in adults spending more time supervising their children’s leisure activities and taking a more strategic approach to overseeing participation in sports (Day, Citation2023; Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Knoester & Fields, Citation2020). Growing numbers of parents encouraged their children to enrol in private sports programmes and to specialize at younger ages both because this seemed rational for skill development but also because of fears that their children could become omitted from the mobility pipeline in a sport or otherwise disadvantaged if they opted out of a programme for a season or decided to sample another sport (Coakley, Citation2016). This was especially prevalent among middle- and upper-class families who could afford to pay for activities that emphasized performance and competitive success and within families that were led by parents who played sports themselves (Clark, Citation2008; Haycock & Smith, Citation2016; Quarmby, Citation2016).

But, after a period of sustained expansion, participation in youth sports seemingly began to slow after the turn of the twenty-first century. Data collected by the Sports & Fitness Industry Association (SFIA) indicated that between 2008–2013, the number of children between the ages of 6–12 who played youth sports on a regular basis dropped by 44.5%. For children ages 13–17, participation rates were slightly higher. Consequently, in 2021, 41.7% of such teenagers indicated that they played a team sport on a regular basis and 51.8% played an individual sport. Yet, while participation in some sports had grown, on average, athletes did not seem to be playing as much as they used to (Project Play, Citation2022). Some reasons for why this might have become the case included the rise of technology and alluring opportunities to engage with screen-based entertainment, realized disparities in skill levels and commitments in hyper-competitive environments at early ages, and parents’ work commitments and safety concerns for their children that may have restricted their opportunities for sports participation (Coakley, Citation2016; Heffer & Knoester, Citation2021; Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Project Play, Citation2015).

Still, the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) has emphasized that the total number of students who have played for their school each year has largely grown over time – from 3,960,932 in 1971–72 to 7,628,377 in 2009–10. For girls, the registered growth has been particularly impressive (294,015 to 3,172,637 participants). The total number of athletes competing peaked at 7,980,886 during the 2017–18 academic year, before dipping to 7,937,491 in 2018–19 and then dropping to 7,618,054 in 2021–22 (National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS), Citation2021).

Furthermore, information from large national samples of high school students from the Monitoring the Future (MTF) data has complemented the aforementioned findings. Recent MTF data have indicated that more than 65% of all teens participated in some form of organized sports within the past year, with about a 15 percentage point gap between girls and boys. About 16% of 9th graders appeared to drop out of organized sports by the 12th grade, however. Moreover, about 30% of teen girls stopped participating between 9th-12th grade. These attrition rates operated in addition to findings from other research that suggested that about 8% of students dropped out of organized sports between the 3rd-5th grades (Zarrett & Veliz, Citation2021; Zarrett et al., Citation2018). Altogether, previous research suggests that organized youth sports are now more commonly seen as not very fun relative to other pursuits. In addition, there are now more heightened financial and logistic barriers that dampen parents’ abilities and inclinations to encourage and support persistent sports participation. Finally, hyper-competitive environments and restricted opportunities to play and succeed on preferred teams turn some potential participants away (Coakley, Citation2016; Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Project Play, Citation2015; Tompsett & Knoester, Citation2022; Zarrett et al., Citation2018).

Nonetheless, despite some knowledge of basic trends and useful data points from recent decades, there remains a need to further refine understandings of historical patterns of regular youth sports participation (i.e., informal or formal), organized sports participation, and the extent to which youth never play organized sports, play and then drop out, or play organized sports continually while growing up. In addition, understandings of how not only generational contexts have mattered, but also gender, race/ethnicity, SES, and family and community sport cultures need to be improved.

Disparities in access and support for young athletes

Not all children have been provided the same opportunities, support, and encouragement to take part in sports. Disparities have often been linked to gender, race/ethnicity, SES, and family and community sport cultures.

Gender

For most of the 20th century, youth sports catered to the needs of boys, and directed attention and resources to them; girls were largely excluded due to stereotypes about their physical and emotional needs and capabilities (Albrecht & Strand, Citation2010; Wiggins, Citation2013; Wright, Citation2016). Things began to primarily change after 1972, when the Title IX Educational Amendment was enacted. Adoption of Title IX helped to support an explosion in girls’ participation in youth sports. Spurred by this legislation, as well as broader movements for women’s rights and an emphasis on health and fitness, schools, local recreation programmes, and private organizations expanded the opportunities afforded to young girls and women (Coakley, Citation2016; Eckstein, Citation2017; Sabo & Veliz, Citation2008). Quantitative measures of girls’ participation in organized sports indicated rather dramatic increases, too (National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS), Citation2021; Simon & Uddin, Citation2018).

In fact, between 1973–74 and 1994–95, the percentage of female participants, compared with their male peers, approximately doubled (Seefeldt & Ewing, Citation1997). Simon and Uddin (Citation2018) analyzed the 1999–2015 Youth Risk Behaviour Survey and found a narrowing gender gap such that 53% of U.S. high school girls participated in team sports, compared to 62% of boys. Nonetheless, girls’ participation rates did not grow over this time span. Black et al. (Citation2022) discovered an even more modest gender gap among children ages 6–17 in their community and school sports participation. According to the National Health Interview Survey data that they analyzed, 52% of girls and 56% of boys participated.

Statistics that document general trends in sports participation often fail to capture differences among female athletes, though. This is important to address, for example, because Black et al. (Citation2022) found that approximately 60% of non-Hispanic White girls participated in sports, with lower rates of participation occurring among Asian (51%), Hispanic (47%), and Black (42%) girls. Participation rates among both girls and boys are also differentiated by family SES (Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Sabo & Veliz, Citation2008; Zarrett & Veliz, Citation2021).

Race/ethnicity

Longstanding discrepancies in youth sports participation based on race/ethnicity have also existed. Until the middle of the 20th century, organized sports were mostly offered to White boys. Deeply entrenched racism essentially forced Black boys to compete against themselves, only (Wiggins, Citation2013). Things began to change around 1974, following the desegregation of Little League Baseball. After that, opportunities for boys and girls across the country expanded exponentially (Albrecht & Strand, Citation2010).

However, although the number of children from racial/ethnic minority groups who played sports may have increased, disparities in participation rates apparently persisted (Black et al., Citation2022; Hyde et al., Citation2020). White children took part in organized sports at higher rates than their African American, Hispanic, or Asian peers despite the enaction of legislation designed to break down barriers between children of different backgrounds (Pate et al., Citation2000). The historical shift from the offering of mostly school-based sports to increasing numbers of private clubs and travel teams has exacerbated these divisions (Pandya, Citation2021). Financial challenges, linked to race/ethnicity, as well as racial/ethnic prejudices and related barriers have deterred many young athletes from engaging in organized sports. The perception of certain sports as ‘White’ or ‘Black’ may explain some participation patterns; also, differences in perceptions and experiences of being welcomed seem to have shaped the decisions made by African American, Latinx, and other Non-white youth who could be sports participants (Bopp et al., Citation2017; Goldsmith, Citation2003; Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Tompsett & Knoester, Citation2022).

SES

Moreover, SES implications for youth sports participation trends seem to have been somewhat underestimated (Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Scheerder & Vandermeerschen, Citation2016; Tompsett & Knoester, Citation2022). Growing economic inequality over the past 40 years, as well as parenting logics that have increasingly emphasized the importance of extracurricular activities, has resulted in substantial differences in parental expenditures on children’s activities and those gaps seem to have been widening over time. Furthermore, as the costs of participating in youth sports have risen, the options available to parents with limited financial means have contracted. Yet, parents have often been eager to invest in activities with the potential to enhance their children’s talents and skills (Eckstein, Citation2017; Friedman, Citation2013). Consequently, the common upper-middle class approach to parenting that emphasizes organized youth activities as concerted cultivation, enabled by higher SES-linked resources, appears to have differentially shaped the organized youth sports participation patterns of higher SES children (Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Lareau, Citation2003, Citation2015).

In fact, SES differences in sports participation seem to persist throughout childhood (Cairney et al., Citation2015; Zarrett & Veliz, Citation2021). Black et al. (Citation2022) noted that children’s participation in sports appears to be influenced by both parental education and family income. They found that 68% of children who had a parent with a college degree played organized sports compared to only 37% of children who did not have a parent with at least some college education. Also, 70% of children with a family income of 400+% of the federal poverty level (FPL) participated in sports, while only 31% of children with family income levels <100% of the FPL did so. Relatedly, sports participation rates among youth living in households with incomes of $25,000/year were half those evident among youth in homes with incomes greater than $100,000/year, in other data (Project Play, Citation2015).

Cairney et al. (Citation2015) identified family income as an important predictor of sports participation in both organized and informal settings. Yet, Scheerder and Vandermeerschen (Citation2016) concluded that although parental education and income levels influenced youth sports participation, family SES was more closely related to organized compared to informal sports participation. This finding is consistent with other work (Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Knoester & Fields, Citation2020; Knoester & Randolph, Citation2019).

Family and community sport cultures

Finally, family and community sport cultures influence youth sports participation. (Day, Citation2023; Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Knoester & Allison, Citation2022; Wheeler, Citation2012). A parent’s ability to engage in concerted cultivation parenting approaches via sport is seemingly shaped not only by their SES, but also by their own experiences playing and following sports. Children whose parents value sports and encourage sports participation appear to be likely to participate in sports at especially high levels. Relatedly, parents who are comfortable in sports settings are more likely to promote sports participation (Coakley, Citation2006; Haycock & Smith, Citation2016; Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Knoester & Fields, Citation2020; Knoester & Randolph, Citation2019).

According to Birchwood et al. (Citation2008), family culture is a primary determinant of sports participation patterns. The influence is transmitted through a combination of direct and indirect, intentional and unintentional, goals, strategies, and practices that are linked to sports (Wheeler, Citation2012). Not only are views that parents communicate to their children largely formed in response to their own sports participation experiences, they are also shaped by numerous other factors (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, SES). Through socialization, children develop different inclinations towards and opportunities for sports participation (Coakley, Citation2006; Eriksen & Stefansen, Citation2022; Green & Smith, Citation2016). The most influential processes primarily appear to occur during the early formative years of child development and lay the foundation for subsequent sports participation (Mirehie et al., Citation2019; Trussell & McTeer, Citation2007).

Nevertheless, parents who invest heavily in their children’s sports participation may place excessive pressures on their children to perform (Baker et al., Citation2009; Legg et al., Citation2015). This may lead to negative consequences. Fraser-Thomas et al. (Citation2016) found that when parents offer rewards to their children for their sports accomplishments and coach from the sidelines, their children become more likely to drop out of organized sports. These results show that parents who are passionate about sports and recognize the benefits of sports participation may sometimes undermine their children’s interest in organized sports, too.

Community sport cultures also seem to matter. If youth grow up in environments where plentiful sport opportunities exist and participation is encouraged and rewarded, they tend to get more involved. Although, oftentimes, such cultures are linked to SES (Eckstein, Citation2017; Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Tompsett & Knoester, Citation2022).

In sum, the information presented above highlights how, and to what extent, researchers have examined with increasing sophistication an array of factors that influence the sports participation opportunities provided, and denied, to young athletes. It also details knowledge about organized and informal sports participation patterns and how they may have differed across generational, gender, SES, and racial/ethnic lines – although the nature of these patterns and how they have evolved remain understudied topics (Deng & Fan, Citation2022; Hextrum et al., Citation2024). Therefore, we sought to move this literature forward with our own comprehensive investigation of how and to what extent youth sports participation patterns have developed by focusing on reports of having played a sport regularly, ever played organized sports, and never played organized sports, played and dropped out, or played continually while growing up. In the process, we considered how generational contexts, gender, race/ethnicity, SES, and family and community cultures of sport have mattered for sports participation patterns.

Hypotheses

Our conceptual framework and previous research led to the following hypotheses:

H1: Reports of having played (informal or formally organized) sports regularly, as well as having played organized sports specifically, will be higher among recent generations. Yet, playing organized sports and dropping out will be more prevalent among more recent generations, too. We will focus our comparisons on retrospective reports from adults born in the 1990ʹs relative to reports from those born in previous decades dating back to the 1950ʹs.

H2: There will be socially structured differences in youth sports participation that evidence social inequalities.

H2a. Women will be less likely to report having played a sport(s) regularly, played an organized youth sport, and played organized youth sports continually while growing up.

H2b. Higher levels of SES while growing up will be positively associated with having played a sport(s) regularly, played an organized youth sport, and played organized youth sports continually while growing up.

H2c. White youths, compared to Youths of Colour, will be more likely to report having played a sport(s) regularly, played an organized youth sport, and played organized youth sports continually while growing up.

H3: Generational contexts will interact with social inequalities such that:

H3a. Girls among more recent generations became more likely to have played a sport(s) regularly, played an organized youth sport, and played organized youth sports continually while growing up.

H3b. SES differences in having played a sport(s) regularly, played an organized youth sport, and played organized youth sports continually while growing up became more pronounced in more recent generations.

H3c. Racial/ethnic differences in having played a sport(s) regularly, played an organized youth sport, and played organized youth sports continually while growing up became diminished among more recent generations.

H4. Family and community cultures of sport will shape youth sport participation patterns. Specifically, having a parent(s) who was perceived to be more of a sports fan and perceived to be more athletic will lead to higher levels of having played a sport(s) regularly, played an organized youth sport, and played organized youth sports continually while growing up. Also, having had more sports made available to play regularly and having lived in a community that was perceived to be more passionate about sports will be positively associated with having played a sport(s) regularly, played an organized youth sport, and played organized youth sports continually while growing up.

Methodology

Data for our analyses came from the National Sports and Society Survey (NSASS). The NSASS is a novel, comprehensive sports and society survey that was administered in 2018–19 to a large national sample (N = 3,993) of U.S. adults who signed up to be part of the American Population Panel (APP) and take part in social science research studies. The APP consists of 20,000+ members, recruited from in-person pitches, mailings, flyers, and online outreach, and is the product of efforts from the Center for Human Resource Research (CHRR), a leading survey research organization. CHRR also provided support for the NSASS via consultation services, survey instrument editing, programming, and data collection and curating. Although different means of taking the survey were offered, all respondents completed the NSASS online and did so in one hour, on average. Invitations to participate emphasized that the survey was for everyone regardless of their interest and experience with sports. Respondents typically answered well over 400 questions and were compensated with $35. Questions were carefully scrutinized, tested, and edited during the creation of the survey instrument, and were commonly informed by previously used constructs in publicly available surveys and academic papers. Due to time and financial constraints, and the emerging development of the APP in tandem with the recurrent sampling from it for the NSASS, it was realized that a sample that fully reflected U.S. population characteristics could not be obtained in combination with the intended 4,000 person quota design. Thus, in the end, the NSASS sample was built upon the full quota of intended respondents and scholars now commonly draw upon its substantial subgroup sizes and utilize a variety of statistical techniques to enable useful research approaches and attempts at approximating representativeness with the data, when appropriate. Essentially, the demographics of the NSASS mirror those of the APP as it grew from 11,000–21,000+ members during NSASS fielding in 2018–19 and reflect common differential survey response rates: NSASS respondents were disproportionately, White, female, and college educated. Overall, nearly 20% of invitations to take the NSASS resulted in completed surveys. From among those who clicked through an invitation and onto the survey landing page, the response rate was 55% (Knoester & Cooksey, Citation2020).

The sample for the present study was based on the number of NSASS respondents who provided substantive answers to questions about playing a sport(s) regularly while growing up, playing an organized sport while growing up, and ever dropping out of organized sports while growing up. This led to slightly different sample sizes (i.e., n= 3,908 to n= 3,935) for our corresponding binary and multinomial logistic regression analyses. We used multiple imputation with chained equations to address modest amounts of missing data on our predictor variables.

Dependent variables

Descriptive statistics for all variables used in the analyses are presented in . Correlations between variables () and the survey questions used to create the variables are displayed as part of an appendix (). Dependent variables included two dichotomous variables and one three-category variable. Did not play a sport regularly, while growing up, is a dichotomous variable that indicates if a respondent selected ‘I did not play any sports regularly’ when asked about which sport(s) they played, while growing up. Specifically, the NSASS asked: ‘While growing up, which sports did you play, regularly (i.e., more than occasionally for 1+ years)? Please consider both informal (i.e., in the backyard, amongst friends, or pick-up) and formally organized sports (i.e., with coaches, adults in charge, and uniforms).’ Then, a picklist of dozens of common sports was offered, as well as an option to select an ‘other sport(s).’ Early in the NSASS, ‘while growing up’ was defined as between the ages of 6 and 18 because of this age range’s correspondence with youth sports participation. For this sport participation question, 22 respondents refused to answer (REF) and 38 replied with ‘don’t know’ (DK).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for all variables used in the analyses.

The next two variables focus on organized sports participation, while growing up. Organized sports participation reflects affirmative responses to the question: ‘Did you ever play any formally organized sport while growing up (i.e., with coaches, adults in charge, and uniforms)?’ There were 7 REF and 51 DK responses to this question. Finally, our three-category organized sports participation variable further split those who reported participating in organized youth sport into those who participated continually versus those who participated and dropped out, based on responses to the question: ‘While growing up, did you ever completely drop out of or stop playing organized sports?’ In sum, there were 11 REF and 74 DK responses to one of the relevant questions used to determine whether respondents never played organized youth sports, played and dropped out, or played continually while growing up.

Independent variables

Independent variables reflect gender, generational experiences, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES) while growing up, and family and community cultures surrounding sports. We employed a dichotomous indicator of gender based on respondents’ self-identities of being female (1 = female). Age categorizations (dummy variables for < 29 – used as the reference category, 29–38, 39–48, and 59+ years old) were used to tap different generational experiences. Although we could not specify precise dates of birth, age categorizations were linked to presumed ages, based on reported birth years, at the end of 2018. This enabled consideration of the relevance of being born in the 1950ʹs, 60ʹs, 70ʹs, 80ʹs, and 90ʹs and best set apart pre-Title IX experiences from others, to the extent possible. Race/ethnicity was categorized with mutually exclusive dummy variables (White (only) – used as the reference category, (any) Black, (nonblack) Latinx, and Other race/ethnicity). Two measures of childhood SES were used. First, childhood social class (1 = poor; 5 = wealthy) was derived from answers to the question: ‘While growing up, was your family ….?’ Also, parent education refers to the highest level of education that a parent obtained (categorized into dummy variables for: a) no parent with at least some college, b) a parent with some college, and c) a parent with a college degree or more – used as the reference category). Parent indicators were based on responses about up to two parental figures that respondents identified as being their most important parental figures while growing up. Finally, family and community sport culture variables consisted of the maximum reported values for parent sports fandom (0 = not at all; 4 = very much so) and athleticism (0 = not at all; 4 = very much so) in reference to identified parental figures, based on respondents’ perceptions. They also included reports of the number of sports (capped at 20) respondents indicated were made available for them to play regularly (e.g., in your school, in your community, and by your family) and perceptions of how passionate one’s high school community was about sports (1 = not passionate at all; 4 = very passionate), while growing up.

Control variables

Control variables referenced birthplace, community type, and family structure contexts, while growing up. Born outside of the U.S. indicated if respondents reported being born in another country. No parent born in the U.S. signalled if respondents only identified parental figures who they reported were born outside of the U.S. Community type upbringing referred to the usual or typical type of community that respondents reported growing up in (dummy variables for urban – used as the reference category, suburban, small city or town, and rural). Family structure context indicators included reports of the number of brothers and sisters that one had while growing up as well as whether or not one grew up in an intact two parent household (1 = yes).

Analytic strategy

Our analytic strategy involved the use of binary and multinomial logistic regression analyses, nested models, and tests for interaction effects. Essentially, we began with reduced form additive models and then interaction models that focused on our main social structural independent variables and thus included social structural factors, and other background characteristics we wished to control, that are generally thought to be time invariant and reflective of ascribed characteristics. Next, we proceeded to create our full additive and interaction models by including our family and community sport culture independent variables, and some additional control variables, that more explicitly tapped sports-focused factors and also involved some potential changes (e.g., family structures) that may have emerged over time and as a function of the mostly time invariant social structural conditions identified in the reduced form models. Binary logistic regressions were used to predict any regular sports participation and organized sports participation, while growing up. Multinomial logistic regression was used to predict the likelihood of either never playing organized sports or playing and dropping out, compared to playing organized sports continually while growing up. We complemented the traditional presentations of coefficients for these models, signifying findings in terms of log odds, with marginal effects estimates based on setting all other variables at their mean values (MEM). Relatedly, we used marginal effects calculations from our models to present predicted probabilities at means and some predicted probabilities at other representative values to especially help make sense of emergent interaction effects.

First, we focused on our hypotheses about generational, gender, SES, and racial/ethnic differences in youth sports participation patterns in a model that contained social structural background characteristics. Then, we added indicators of family and community cultures of sport to the equation. We present evidence of interaction effects after each additive model, if such effects emerged. To test for interaction effects, we included multiplicative terms for each hypothesized interaction in separate models that were variations of the initial social structural background characteristics models that were first examined (separate model interaction effects results not shown). We first present results from any significant interaction effect that previously emerged as part of our first interaction effects model results – although all related terms were included in the corresponding model (e.g., all combinations of gender x age even if only one gender x age term is presented as significant in a model). We followed this up by testing for changes in the presence and sizes of these interaction effects after adding our indicators of family and community cultures of sport. We offer detailed descriptions, and graphical representations of the effects when they involve interactions, of the marginal effects presented in the full (i.e., final) models for each dependent variable, based on predicted probabilities at representative values or otherwise at the means of other variables, to better understand them.

Results

First, we noted the typical patterns of childhood sports participation that NSASS respondents reported. As shown in , the vast majority of adults in our sample indicated that they played a sport(s) regularly while growing up – only 18% never did. Playing organized youth sports was less common, but still normative, as 65% of adults reported having done so. Finally, after disaggregating those who dropped out of organized youth sports versus those who participated continually, we found that 35% of respondents never played an organized sport, 41% played but then dropped out, and 23% played an organized sport continually, while growing up.

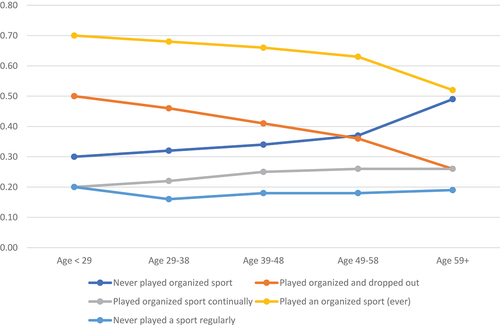

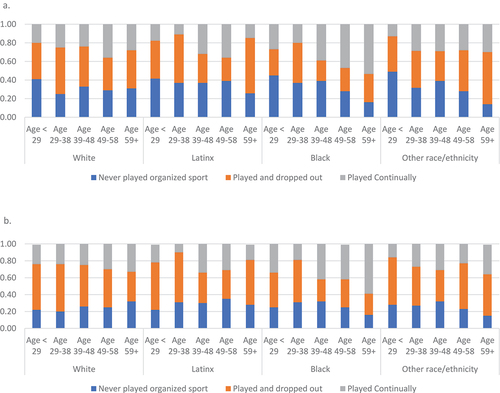

Next, since our focus and analysis highlight generational differences and H1 relates to such differences, we present an overview of the generational trends relating to never playing a sport regularly, playing an organized sport (ever), and then the mutual exclusive categories of never playing an organized sport, playing an organized sport and dropping out, or playing an organized sport continually, while growing up. These sport participation patterns by generation are displayed in and indicate patterns after accounting for gender, racial/ethnic, and socioeconomic status contexts (i.e., predicted probabilities after all other forthcoming Model 1 variables are set to their means). Notably, across generations, the trendlines reveal rather stable risks of never playing a sport regularly, increased likelihoods of ever playing an organized sport (along with declining likelihoods of never playing an organized sport), increased likelihoods of playing an organized sport and dropping out, and some decline in likelihoods of playing an organized sport continually, while growing up.

Figure 1. Initial predicted probabilities of different patterns of sport participation while growing up, across generations, after accounting for gender, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status differences.

Table 2. Results from Logistic Regressions of Never Playing a Sport Regularly, While Growing Up.

Table 3. Marginal Effects for Never Playing a Sport Regularly, While Growing Up.

Table 4. Results from Logistic Regressions of Playing an Organized Sport, While Growing Up.

Table 5. Marginal Effects for Playing an Organized Sport, While Growing Up.

Table 6. Results from Multinomial Logistic Regressions that Include Findings for Never Playing an Organized Sport versus Playing an Organized Sport Continually, While Growing Up.

Table 7. Results from Multinomial Logistic Regressions that Include Findings from Playing an Organized Sport and Dropping Out versus Playing an Organized Sport Continually, While Growing Up.

Table 8. Marginal Effects for the Predicted Probabilities of Never Playing an Organized Sport, Playing an Organized Sport and Dropping Out, and Playing an Organized Sport Continually, While Growing Up.

Never played a sport regularly

Next, we turn to our regression analyses. In , we present the binary logistic regression results from predicting the likelihood that respondents reported never playing a sport regularly, while growing up. The corresponding marginal effects estimates for the variables in these models, with all other variables set to their mean values, are displayed in . As shown in Model 1, consistent with , we did not find support for H1, which anticipated that more recent generations would report higher levels of playing a sport regularly. In fact, there was evidence that those born in the 1990ʹs had .27 higher log odds than those born in the 1980ʹs (b = −.27, p < .05) of having never played a sport regularly while growing up. As indicated in Model 1 of , the corresponding marginal effect for the predicted probability difference in never playing a sport regularly was −.04. However, we did find evidence that gender and SES mattered for sports participation, consistent with H2a and H2b. Adults who identified as female (b = 0.47, p < .001) were more likely to have reported never playing a sport regularly compared to those who did not identify as female. The marginal effect of gender was .06. Also, compared to having a parent with a college degree, having no parent with some college (b =.48, p < .001) or having a parent with some college but no degree (b =.27, p < .05) led to higher likelihoods of never playing a sport regularly and marginal effects of .07 and .04 for parental education, respectively. Higher levels of childhood social class (b = −.17, p < .001) led to reduced likelihoods of never playing a sport regularly, while growing up. The marginal effect for the continuous variable childhood social class was −.03, indicating the associated instantaneous rate of change in the dependent variable. There was no evidence of racial/ethnic differences in regular sport participation in line with our H2c prediction. Moreover, we did not find evidence that gender, socioeconomic status, or race/ethnicity moderated associations between respondents’ age categorizations and their likelihoods of never playing a sport regularly (results not shown). That is, we found no evidence of the interaction effects anticipated by H3a-c when we looked for them, one at a time, as an extension of our reduced form additive model (i.e., Model 1).

As presented in Model 2 of and , there was consistent support for H4 and the relevance of family and community cultures of sport. That is, higher levels of parent fandom (b = −.13, p < .01), parent athleticism (b = −.30, p < .001), number of sports made available (b = −.14, p < .001), and community’s sport passion (b = −.17, p < .01) each reduced the likelihood that respondents reported never playing a sport regularly, while growing up. Again, we did not find support for H3a-c as we did not find evidence that gender, socioeconomic status, or race/ethnicity moderated associations between respondents’ age categorizations and their likelihoods of never playing a sport regularly (results not shown). The results from the full model led to marginal effects at means for the indicators of family and community cultures of sport that ranged from −.02 to −.04 and translated to maximum differences (i.e., differences when variables are set to their maximum and minimum values) in predicted probabilities based on parent fandom (.19 vs. .12 probability), parent athleticism (.20 vs. .07 probability), and community’s sport passion (.24 vs. .14 probability) that ranged from .07-.13. Number of sports available offered a marginal effect of −.02 and resulted in a .17 vs. .03 predicted probability of having never played, depending on if one reported having five or twenty sports made available.

The additional consideration of family and community cultures of sport in the full model appeared to render childhood social class nonsignificant, diminished the relevance of parental education, and resulted in some emerging generational differences. This suggests that family and community cultures of sport were linked to SES and were more prevalent for the youngest generation than for the oldest generations. Yet, gender still seemed to offer a marginal effect of .05 (i.e., .12 vs. 17 predicted probability of never having played a sport regularly) and a parent with a college education provided a −.03 marginal effect (i.e., a predicted probability of .14 versus one of .17 when having no parent with some college and one of .16, now at p < .10, when having a parent with some college). Generational differences seemed to expand, at equal levels of family and community cultures of sport, with persons born in the 1990ʹs not only being more likely than those born in the 1980ʹs to have never played (i.e., .19 vs. .14 predicted probability), but also becomingly more likely than those born in the 1970ʹs to have played by virtually the same amount – with some suggestive evidence (p < .10) that comparable differences may have also translated to older generations to some extent, too.

Ever played an organized sport

The binary logistic regression findings and corresponding marginal effects for organized sports participation are presented in and . Model 1 displays evidence of generational, gender, and SES differences in support of H1 and H2a-b. There was some evidence (p < .10) consistent with H2c’s anticipation of racial/ethnic differences. First, compared to adults born in the 1990ʹs, those born in the 1960ʹs (b = −.30, p < .01; MEM = −.07) and 1950ʹs (b = −.76, p < .001; MEM = −.18) were less likely to report playing organized sports while growing up. Females (b = −.35, p < .001; MEM = −.08) were also less likely to play organized sports than adults who did not identify as female. Higher SES youth were more likely to play organized sports as indicated by associations involving childhood social class (b =.15, p < .001; MEM =.03) and the relative implications of having no parent with some college education (b = −.54, p < .001; MEM = −.12) or a parent with some college (b = −.22, p < .05; MEM = −.05), as opposed to having a parent with a college degree. There was also some support for the expectation that White adults were more likely to have participated in organized sports while growing up than Black (b = −.22, p < .10; MEM = −.05) adults.

Model 2 of presents support for H3a-c as there was evidence that gender, race/ethnicity, and parental education interacted with respondents’ generational context to shape likelihoods of playing organized sports (recall that these interaction effects were first tested in separate models, then combined into a full interaction model for this reduced form Model 2; also, we only display the coefficients for the terms that emerged as significant when tested separately – the model still contained all combinations of the component interaction terms that pertained to a significant interaction effect, although the nonsignificant coefficients for interaction terms involving respondents’ age and gender, race/ethnicity, and parental education categories are not shown). Gender implications appeared to depend on generational experiences, as expected. For example, compared to adults who do not identify as female in the 1990ʹs, females reported particularly lower levels of organized sport participation in the oldest generation (e.g., .70 versus .60 and .44 predicted probabilities for females born in the 1960ʹs and 1950ʹs, respectively; females born in the 1990ʹs also had a .70 predicted probability of playing organized sports). Compared to those who had a parent with a college degree, those with no parent with some college education had smaller deficits in the likelihood of playing an organized sport in older generations (e.g., .24 deficits in predicted probabilities for those born in the 1990ʹs winnowing to .01 for those born in the 1950ʹs). There was a more modest and uneven change in the relative relevance of having a parent with some college (e.g., no major change in a .10-.08 predicted probability deficit except for evidence of a .05 advantage for those born in the 1960ʹs who had a parent with some college). Finally, Black and Other race/ethnicity respondents, relative to Whites, reported especially higher levels of organized sport participation in the oldest generation (e.g., Black and Other race/ethnicity respondents born in the 1950ʹs had predicted probabilities that were .04-.10 higher than those born in the 1990ʹs; White respondents had predicted probabilities that were .23 lower among those born in the 1950ʹs compared to the 1990ʹs; White respondents registered .08-.09 higher predicted probabilities than Black and Other race/ethnicity respondents born in the 1990ʹs). We return to considering these interaction effects and their implications for intersectional gender, racial/ethnic, and SES social structural locations after presenting the full interaction model that also contained measures of family and community cultures of sport in Model 4.

In Model 3 of and , support for H4 became apparent. Parent fandom (b =.11, p < .01; MEM =.02), parent athleticism (b =.26, p < .001; MEM =.06), number of sports made available (b =.13, p < .001; MEM =.03), and community’s sport passion (b =.26, p < .001; MEM =.06) were each positively associated with the likelihood of playing organized sports while growing up. Also, after accounting for family and community cultures of sport, there was no longer some (p < .10) support for the expectation that White adults were more likely to have participated in organized sports while growing up than Black adults; instead, some support for a White-Latinx disparity emerged (b = −.26, p < .10; MEM = −.06).

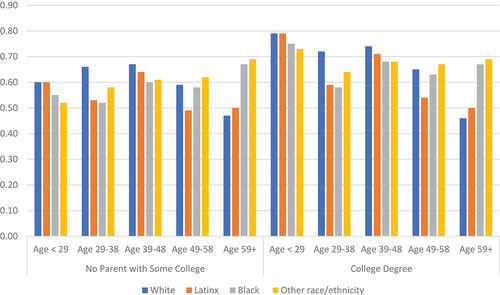

Finally, in Model 4, we present evidence of interaction effects that involved age with each of gender, socioeconomic status, and race/ethnicity. These appeared to mirror the findings from Model 2 and offered additional support for H3a-b. As shown in and , the findings resulted in particularly lower predicted probabilities of organized sports participation among (White and Latinx) females in the oldest generation (i.e., .70 vs. .49 predicted probability between the youngest and oldest generations of females). There was also support for H3b as parental education differences seemed to be most pronounced within the youngest generation (e.g., resulting in a .19 versus no predicted probability difference between those with a parent who had a college degree and those who had no parent with some college within the youngest generation as opposed to within the oldest generation). Overall, organized sports participation patterns suggested a narrowing of gender differences and an increasing gap based on parent education across generations. This seemed to primarily be a function of females with a college educated parent becoming much more likely to participate and declines occurring among those who did not identify as female and also did not have a college-educated parent. In addition, there was some evidence that White advantages have become more pronounced recently (e.g., White-Black and White-Other race/ethnicity differences of .05-.07 for those born in the 1990ʹs; White deficits in participation only occurred among those born in the 1950ʹs) – especially among females. But, the expected finding of White advantages in organized sport participation being elevated in older generations does not seem to be supported.

Figure 2. Predicted probabilities of having played an organized sport for females based on generational, racial/ethnic, and parents’ highest educational attainment contexts and interaction effects.

Figure 3. Predicted probabilities of having played an organized sport for those who did not identify as female based on generational, racial/ethnic, and parents’ highest educational attainment contexts and interaction effects.

Beyond the nature of the interaction effects, the results from the full Model 4 from and ndicated a marginal effect at means of gender of .07 (.65 vs. .73 predicted probability of organized sport participation), a .14 generational difference between the youngest and oldest generations (.70 vs. .56) with those born in the 1950ʹs being less likely than all other generations to play organized sport, and a −.08 MEM for those without a parent with some college compared to those with a parent who was college-educated (.63 vs. .71). There was some evidence of a −.06 MEM for Latinx, relative to White, individuals. The predicted probability differences at extreme values of parent fandom (.62 vs. .72; MEM =.03), parent athleticism (.60 vs. .81; MEM =.06), and community’s passion (.47 vs. .71; MEM =.06) ranged from .10-.24. Number of sports available led to a .28 gap in predicted probabilities (.65 vs. .93 probability; MEM =.03) when comparing the offering of five versus twenty sports to play regularly while growing up.

Never played an organized sport, played and dropped out, or played continually

Finally, we turn to our multinomial logistic regression analysis. This approach considered the likelihood of never playing an organized sport and playing and dropping out, relative to playing an organized sport continually while growing up. We present the first set of comparisons from this analysis in and the second set of comparisons in . We display the marginal effects for each outcome in . In discussing the results and implications of these models, we first focus on the traditional coefficients from , then turn to the coefficients from , and conclude with more detailed marginal effects and predicted probability implications as we review the MEM’s reported in .

As shown in , when we turned to predicting never playing an organized sport with our multinomial model instead of playing one as we did in our binary model, and the comparison group was changed to playing an organized sport continually, we still found evidence that females (b =.40, p < .001) and those with lower SES were more likely to never play an organized sport. Specifically, lower childhood social class status (b = −.23, p < .001) and having no parent with some college (b =.44, p < .001), compared to having a parent with a college degree, seemed to increase the relative risk of never playing an organized sport versus playing an organized sport continually, as presented in Model 1. In addition, there was some evidence of White advantage, relative to Latinx participation (b =.29, p < .10), in playing a sport continually. These findings offered additional support for H2a-c. In Model 2, initial evidence of interaction effects is presented that again offered some support for H3a-b and reflected results from predicting any organized sport participation in our binary logistic regressions. That is, females from older generations appeared more likely to have never played organized sports than to have played continually – at least among White and Latinx females. There was also some support for H3b as SES differences in organized sport participation seemed to be more pronounced within the youngest generation compared to at least one older generation, as evidenced in the displayed interaction term coefficient for not having a parent with some college. Finally, although there was some evidence of White advantages in (continual) organized sport participation relative to Other race/ethnicity respondents in this model, the interaction effects suggested that Black and Other race/ethnicity individuals seemed to have particularly been more likely to participate in organized sport (continually) in the oldest generation, on a relative basis. This latter finding was consistent with previous results displayed in (and aligned with the corresponding full model predicted probabilities shown in and ), although it was in contrast to H3c expectations.

The findings presented in Model 3 of offered more evidence that family and community cultures of sport were relevant, as anticipated by H4. Parent fandom (b = −.13, p < .01), parent athleticism (b = −.31, p < .001), number of sports made available (b = −.13, p < .001), and community’s sport passion (b = −.34, p < .001) were negatively associated with the relative risk of never playing an organized sport versus playing an organized sport continually. In addition, stronger evidence of White advantage relative to Latinx experiences emerged (b =.45, p < .05) and parental educational advantages appeared to diminish (b =.22, p < .10), after accounting for family and community cultures of sport. Finally, as displayed in Model 4, there was some evidence of interaction effects involving age and each of gender, race/ethnicity, and SES. Again, females appeared to have been especially less likely to have played an organized sport (continually) in the oldest generations. Parental education advantages appeared to have been less pronounced in some older generations. Other race/ethnicity adults seemed to have been particularly likely to have played an organized sport (continually) in the oldest generational context – but there was also some emerging evidence of higher levels of Latinx participation for those born in the 1970ʹs relative to the 1990ʹs. We return to further discuss these patterns and introduce evidence of the corresponding marginal effects and predicted probabilities for never playing an organized sport and playing continually after sharing the second half of our multinomial logistic regression results.

The second half of our multinomial results considered the relative risks for playing and dropping out of organized sports versus playing an organized sport continually. The log odds coefficients are presented in . As shown in Model 1, consistent with H1, older generations were less likely to drop out of organized sports versus playing continually until adulthood. Compared to those born in the 1990s, adults born in the 1970ʹs (b = −.43, p < .01), 1960ʹs (b = −.59, p < .001), and 1950ʹs (b = −.93, p < .001) were less likely to drop out. In accordance with H2b, higher levels of childhood social class (b = −.13, p < .01) led one to be more likely to play continually as opposed to dropping out, too. Unexpectedly, Black (b = −.61, p < .001) respondents seemed to have been much less inclined to drop out of organized sports, versus playing continually, relative to White youth. This may reflect the disproportionate encouragement, and relative perceived opportunity for success, that Black youth often experience in sport as opposed to other spheres of life (Hextrum et al., Citation2024; Tompsett & Knoester, Citation2022). In Model 2, we observed no evidence of significant interaction effects distinguishing the relative risks of dropping out of organized sports versus playing continually; the presented model included the same interaction terms as those represented in Model 2 of , however (i.e., we presented as two halves, one whole multinomial model).

In Model 3 of , indicators of family and community cultures of sport were highlighted. Consistent with H4, higher levels of parent athleticism (b = −.08, p < .05) and community’s passion for sport (b = −.13, p < .05) seemed to reduce the relative risk of dropping out of organized sport compared to playing continually. It was also striking that growing up in an intact two parent family (b = −.24, p < .05) apparently led to a lower relative risk of dropping out, which may speak to the challenges of supporting a child’s organized sport involvement, continually. Finally, as shown in Model 4, we again saw no evidence of significant interaction effects distinguishing the relative risks of dropping out of organized sports versus playing continually; although, the presented model included the same interaction terms as Model 4 from .

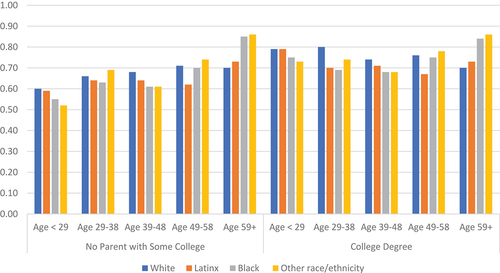

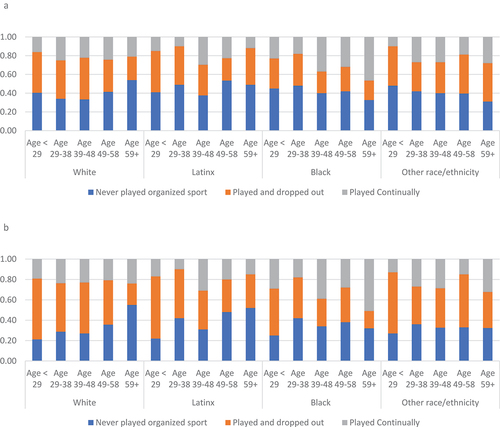

The marginal effects for our multinomial model results are presented in . Relatedly, the multinomial results were converted to predicted probabilities at representative values to better realize their implications for patterns of never playing organized sports, playing and dropping out, and playing continually. We present findings broken down by generation, gender, race/ethnicity, and parental education in in order to best represent the interaction effects from the full models (i.e., Model 4) displayed in and as well as our empirical focus on the implications of age, gender, SES, and race/ethnicity as part of our hypotheses.

Figure 4. (a) Predicted probabilities of never playing an organized sport, playing and dropping out, and playing continually among females with no parent with some college. (b) Predicted probabilities of never playing an organized sport, playing and dropping out, and playing continually among females with a parent with a college degree.

Figure 5 a. Predicted probabilities of never playing an organized sport, playing and dropping out, and playing continually among those who did not identify as female and had no parent with some college. b. Predicted probabilities of never playing an organized sport, playing and dropping out, and playing continually among those who did not identify as female and had a parent with a college degree.

First, in , we noted rather consistent evidence in support of H1 with older generations being associated with MEM’s that were .04-.18 higher for never playing an organized sport .05-.08 higher for playing an organized sport continually, and .07-.25 lower for playing and dropping out, relative to the 1990ʹs birth cohort. This contrasts with the absence of evidence for some of these associations in – suggesting that the interaction effects involving gender and the relative comparison between the likelihoods of never playing and playing and dropping out masked some of the underlying influences of generational contexts for organized youth sports participation patterns. There was typically some diminishment of these MEM’s after family and community cultures of sport were added to the equation, suggesting differences in these factors across generational experiences. Moreover, in support of H2a, identifying as female was linked to MEM’s that were .07-.08 higher for never playing an organized sport and .04 lower for playing a sport continually. We did not explicitly hypothesize about gender’s link to dropping out of organized sports, but the MEM’s associated with doing so of -.04 seemed to provide additional evidence that female sport participation opportunities have been relished and taken advantage of, when offered. In support of H2b, childhood social class had MEM’s that were .03 lower for never playing an organized sport and .02-.03 higher for playing a sport continually, diminishing after the consideration of family and community cultures of sport were considered. Also, relative to having a parent with a college degree, having no parent with some college resulted in MEM’s ranging from .07-.13 higher for never playing an organized sport, while having a parent with some college resulted in MEM’s ranging from .04-.05 higher, diminishing after the consideration of family and community cultures of sport were considered. These differences in MEM’s after the consideration of family and community cultures of sport suggested that SES was linked to such cultures. Finally, there was modest support for H2c in with some (p < .10) evidence of Black respondents being more likely to never play organized sports (MEM =.05) and Latinx respondents being less likely to play continually (MEM = −.04) in Models 1 and 2, relative to Whites. Stronger evidence of White-Latinx gaps emerged after accounting for differences in family and community cultures of sport (i.e., MEM =.07 and −.05 for never playing and playing continually, respectively, at p<.05). Again, although we did not explicitly hypothesize about SES and racial/ethnic links to dropping out of organized sports, the MEM’s for Black and not having a parent with some college appeared to indicate that sport participation opportunities have been particularly relished and taken advantage of, when offered, among such individuals.

The marginal effects estimates from also highlighted the relevance of family and community cultures of sport. Parent fandom, parent athleticism, number of sports available, and community’s sport passion all offered MEM’s that were supportive of H4 for never playing an organized sport (MEM’s = −.02 to −.06) and playing one continually (MEM’s =.01-.04). These translated to substantial differences in predicted probabilities, based on the full Model 4 results with all other variables set to their means, for never playing an organized sport and playing continually based on maximum differences (i.e., minimum versus maximum values) connected to parent fandom (.39 vs. .29 and .20 vs. .26, respectively), parent athleticism (.41 vs. .20 and .20 vs. .33, respectively), and community’s passion (.54 vs. .30 and .12 vs. .26, respectively) that ranged from .06-.24. Number of sports available led to impressive predicted probability differences when comparing the offering of five versus twenty sports to never playing an organized sport (.36 vs. .07) and playing continually (.23 vs. .33), too.

Substantively, in light of the interaction effects involving age, gender, SES, and race/ethnicity, the predicted probability implications involving age, gender, SES, and race/ethnicity became complicated. Consistent with H3a, the Model 4 results translated to a .22 (i.e., .31 vs. .53) decline in females’ predicted probabilities of never playing an organized sport if one was born in the 1990ʹs compared to the 1950ʹs. But, unexpectedly, increased organized sports participation did not translate to continual participation (i.e., evidenced a decline to .18 from .24 predicted probability). Instead, females born in the 1990ʹs became markedly more likely to play organized sports and drop out before adulthood (.51 vs. .23). Also, consistent with H3b, having a parent with a college degree led to a reduced .23 predicted probability in never playing an organized sport across generations born in 1950–1990 (.45 vs. .22). Meanwhile, having no parent with some college resulted in stable predicted probabilities of never playing an organized sport (.43-.42). Yet, again, the bulk of the change across generations resulted in increased predicted probabilities of playing and dropping out among those with a parent with a college degree (.27 to .57 vs. .32 to .41 change among those without a parent with some college); declines in predicted probabilities of playing continually actually occurred across generations regardless of parental education (.29 to .21 and .25 to .17, respectively). The interaction effects involving race/ethnicity did not seem to align very well with H3c, if at all. Mostly, what we saw were particularly low predicted probabilities of never playing an organized sport among Black and Other race/ethnicity individuals born in the 1950ʹs (e.g., .28 vs. .50 for Whites). We observed pretty consistent evidence of (nonsignificant) lower predicted probabilities of never playing an organized sport among White respondents across generations, with only White-Latinx disparities becoming apparent as indicated in Model 4 of . Black respondents especially had high predicted probabilities of playing continually within the oldest generation (.52) and Latinx predicted probabilities for playing continually seemed to be rather uneven, but commonly lower than White patterns. To allow for more detailed intersectional considerations, we broke down the predicted probabilities by generation, gender, race/ethnicity, and parental education in in order to best represent the interaction effects from the full model (i.e., Model 4).

Discussion

Using data from a large, unique national sample of U.S. adults who were born in the 1950s through the 1990s, this study examined patterns of different aspects of youth sports participation across generations and how they varied according to gender, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and family and community cultures of sport. We first described reports of having ever played a sport regularly, ever played an organized sport, and then having either never played an organized sport, played an organized sport and then dropped out, or played an organized sport continually while growing up. Then, we used binary and multinomial logistic regression analyses to assess how age, gender, socioeconomic statuses, race/ethnicity, and family and community cultures of sport shaped youth sports participation. Overall, we found evidence of increased likelihoods of ever playing an organized sport as well as playing an organized sport and dropping across generations. Although there was some evidence of a decline in playing a sport continually, playing a sport regularly remained an overwhelmingly common experience while growing up. In addition, results indicated some dwindling gender gaps in youth sports participation, but increasing socioeconomic status gaps. Racial/ethnic differences were more uneven, but there was some evidence of more dramatic participation declines across generations among Black and Other race/ethnicity respondents. Family and community sport cultures were consistent and meaningful predictors of youth sports participation patterns. These findings highlight social structural and cultural ramifications for youth sports.

Our first hypothesis anticipated increases across generations in any youth sports participation, organized sports participation, and dropping out of organized sports participation. Surprisingly, we initially found little evidence of differences across generations in the likelihood of ever playing sports regularly – either informally or formally. About 80% of respondents reported doing so, speaking to the normative experience of playing sports while growing up – even before enormous growth occurred in the youth sports industry and before the advent of Title IX (Knoester & Allison, Citation2022, Citation2023; Knoester & Randolph, Citation2019; Project Play, Citation2015; Sabo & Veliz, Citation2008). However, we found some evidence of an unanticipated decline in reports of ever having played sports regularly among respondents born in the 1990ʹs compared to those born in the 1980ʹs. This finding does seem to be in line with sport industry data that indicate that in recent years, young athletes have not been playing sports as much as they used to – although the data are focused on organized sports participation statistics (National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS), Citation2021; Project Play, Citation2015; Project Play, Citation2022). Additional evidence of generational differences emerged after accounting for family and community cultures of sport, which suggests that children born in the 1990ʹs may have been rather unique in having been less likely to have played sports regularly while growing up after accounting for different family and community cultures of sport that may have enabled sports participation to a greater extent for those born in the 1990ʹs.