Abstract

Objectives: To observe and analyse the range and nature of behaviour change techniques (BCTs) employed by audiologists during hearing-aid fitting consultations to encourage and enable hearing-aid use. Design: Non-participant observation and qualitative thematic analysis using the behaviour change technique taxonomy (version 1) (BCTTv1). Study sample: Ten consultations across five English NHS audiology departments. Results: Audiologists engage in behaviours to ensure the hearing-aid is fitted to prescription and is comfortable to wear. They provide information, equipment, and training in how to use a hearing-aid including changing batteries, cleaning, and maintenance. There is scope for audiologists to use additional BCTs: collaborating with patients to develop a behavioural plan for hearing-aid use that includes goal-setting, action-planning and problem-solving; involving significant others; providing information on the benefits of hearing-aid use or the consequences of non-use and giving advice about using prompts/cues for hearing-aid use. Conclusions: This observational study of audiologist behaviour in hearing-aid fitting consultations has identified opportunities to use additional behaviour change techniques that might encourage hearing-aid use. This information defines potential intervention targets for further research with the aim of improving hearing-aid use amongst adults with acquired hearing loss.

Key Words:

Introduction

It is acknowledged that rates of hearing-aid use are sub-optimal and that the reasons for this are complex and multi-factorial (Gopinath et al, Citation2011; McCormack & Fortnum, Citation2013; Ng & Loke, Citation2015). The study of the factors that influence hearing-aid use is important because hearing-aid use is a behaviour that has been linked to outcome in terms of improved quality of life (Mulrow et al, Citation1990; Chisolm et al, Citation2007). In the context of this research, behaviour is defined as ‘anything a person does in response to internal or external events’ (Michie et al, Citation2014, p. 234).

Many studies have investigated reasons for non-use of hearing-aids. McCormack and Fortnum (Citation2013) collated results from 10 individual studies and identified a number of reported reasons for non-use including: hearing-aid value; fit and comfort and maintenance of the hearing-aid; attitude; device factors; financial reasons; psychosocial/situational factors; healthcare professionals’ attitudes; ear problems; and appearance of the hearing-aids. In a systematic review, Ng & Loke (Citation2015) identified 22 studies relating to hearing-aid use and found both audiological and non-audiological factors affected hearing-aid usage. Audiological factors included: the severity of hearing loss; the type of hearing-aid; background noise acceptance; and insertion gain relative to prescription target. Non-audiological factors included: self-perceived hearing problems; expectations of hearing-aids; demographics such as age; whether the hearing-aid was fitted in a group or individual consultation; support from significant others; self-perceived benefit; and satisfaction with hearing-aids.

Some of the reported determinants of hearing-aid use could be influenced by the behaviour of the audiologist with whom the person with hearing loss interacts. For example, audiologists can ensure that a hearing-aid is comfortable to wear and that they have provided instruction and practice at using it. They could also work with patients and their significant others to address expectations and attitudes to hearing-aid use. Audiologist behaviour which supports hearing-aid use is a type of self-management support (Pearson et al, Citation2007). Self-management support, particularly support that encourages the active involvement of people with hearing loss in their own care, is potentially important in changing behaviour and improving outcome in the context of hearing healthcare (Pearson et al, Citation2007; Grenness et al, Citation2014; Barker et al, Citation2014, Citation2015). Audiologists may offer self-management support pre-, per- or post- hearing-aid fitting. Examples of pre-fitting interventions include those that seek to explore the expectations of the prospective hearing-aid user or that offer counselling regarding acknowledgement of hearing loss (e.g. Brooks & Johnson, Citation1981; Norman et al, Citation1994). Post-fitting interventions might include additional hearing-aid orientation or communication training (e.g. Hickson et al, Citation2007; Thoren et al, Citation2014; Ferguson et al, Citation2015). Studies suggest that there are opportunities for audiologist behaviour change in pre- and post-fitting consultations. For example, Ekberg et al (Citation2015) highlight that audiologists could be more proactive in involving significant others in assessment consultations, and Grenness et al (2015b) suggest that opportunities exist for audiologists to communicate in a more patient-centred way with their patients. Per-fitting interventions have received relatively little attention in the literature to date (Knudsen et al, Citation2010). The fitting consultation is the point at which a change in behaviour on the part of the person with the hearing loss is expected to begin. They are expected to start using a hearing-aid from that point. The behaviour of audiologists during hearing-aid fitting consultations is therefore of interest. Studying how audiologists and patients interact may reveal opportunities to introduce more effective interventions to improve hearing-aid use.

The reviews of reasons for non-use of hearing-aids discussed above summarize the influence of different factors on hearing-aid behaviour. However, neither used behavioural theory to analyse or classify the data and they did not draw specific links between patient and audiologist behaviour. This makes it more difficult to decide where to target intervention efforts to change behaviour (Michie et al, Citation2005) and improve hearing-aid use. In addition, the individual studies included in both reviews collected data based on self-report and interviews. Doing this without reference to psychological theory risks underestimating the role of potential determinants of behaviour, particularly automatic motivational processes such as habit and impulse, into which participants may have little insight (Michie et al, Citation2014).

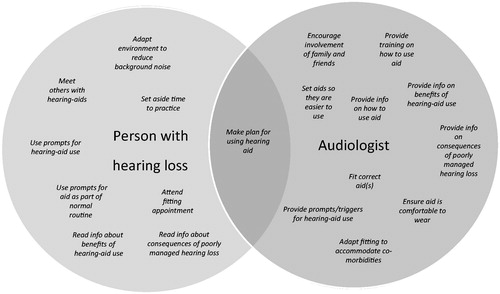

Barker et al (Citation2016) analysed the literature on reasons for non-use of hearing-aids using the COM-B model (Michie et al, Citation2014) and used this to generate a conceptual map of the patient and audiologist behaviours that might be relevant to hearing-aid use, as shown in (adapted from Barker et al, Citation2016).

Figure 1. Patient and audiologist component behaviours that interact and may contribute to long-term hearing-aid use (adapted from Barker et al, Citation2016).

Some of the audiologist behaviours are technical (such as selecting and setting a hearing-aid that is appropriate for the persons hearing loss) and some represent activities that aim to support the patient so that they are able to use their hearing-aid more effectively and as such can be classified as behaviour change techniques (BCTs). A BCT is a method for changing one or several determinants of behaviour such as a person’s capability, opportunity, or motivation (Michie et al, Citation2014). The extent to which such behaviours are being carried out is unknown because little research has been carried out into what happens in the fitting consultation (Knudsen et al, Citation2010).

There is a vast choice of BCTs covering the range of psychological theories and using different nomenclature (Michie et al, Citation2014). This range can be confusing for those developing and evaluating behaviour change interventions (Michie et al, Citation2005). A number of attempts have been made to standardize and organize BCTs within particular contexts (Leeman et al, Citation2007; Michie et al, Citation2011). This study used version 1 of the behaviour change technique taxonomy (BCTTv1). This taxonomy was developed using a formal process of expert consensus and consists of 93 behaviour change techniques (BCTs) that are applicable across contexts. Individual BCTs can be linked back to psychological theories and constructs but the taxonomy as a whole is not linked to a specific psychological theory or model. It allows those developing or evaluating interventions to specify, using a common language, the ‘active ingredients’ of an intervention and gives guidance on linking individual BCTs back to relevant psychological theory (Michie et al, Citation2013). It has been applied in a number of contexts, including weight loss and smoking cessation, to describe, develop, and evaluate behaviour change interventions (see Michie et al, Citation2014 for a range of examples). Its use has recently been recommended in hearing healthcare research (Coulson et al, Citation2016).

This study aimed to observe and categorize audiologist behaviour during routine adult hearing-aid fitting consultations. The aim was to produce a picture of BCTs in current use which can then be compared with the map of theoretically relevant behaviours shown in . Any differences may present potential targets for intervention development with the aim of increasing long term hearing-aid use (Michie et al, Citation2014).

Methods

This study employed non-participant observation using video recording (Caldwell & Atwal, Citation2005) in a random sample of English audiology services. Clinician behaviour during routine hearing-aid fittings was classified using version one of the behaviour change technique taxonomy (BCTTv1) (Michie et al, Citation2013). Audiology services were sampled from a comprehensive list of 127 NHS audiology departments in England, compiled by combining data from the British Academy of Audiology, voluntary groups working on behalf of people with hearing loss, and the Department of Health. Using a random number generator, five English NHS audiology services were selected and invited to take part in this study. Of the five departments originally approached to take part, two declined, citing pressure on service provision as the reason. Two further departments were randomly selected and both agreed to take part. Within each of the five departments, two audiologists were randomly sampled to take part in data collection by drawing their names out of a hat. Audiologists working autonomously in any NHS audiology department in England were eligible for inclusion. This included part-time staff and student audiologists who were working without direct supervision. It excluded student audiologists who were seeing patients but only with another member of staff present in a supervisory capacity. All patients attending for a hearing-aid fitting who were able to read and understand the participant information and consent form were eligible for inclusion with no exclusion criteria by age, gender, hearing loss, or type of hearing-aid fitting. Departments were asked to schedule first time fitting appointments where possible. Patients and audiologists were supplied with participant information at least a week prior to data collection. Written consent was obtained from both parties by a researcher immediately prior to the fitting consultation. The five participating departments covered a wide geographical area of England including central, south west, north, and east England. All ten audiologists and patients gave written consent to take part. However, one audiologist later withdrew consent and the BCT data from that fitting is therefore not included in subsequent analyses. Participant and consultation information is included in .

Table 1. Demographic information about participants, and details regarding consultation type and length.

The study received NHS ethical approval from the NRES committee Yorkshire and the Humber – Leeds West, and from the University of Surrey Ethics Committee (REC reference 14/YH/1252). Data collection took place in April and May 2015.

A single hearing-aid fitting consultation was recorded in the room in which the audiologist normally worked with only the audiologist, patient, and any accompanying others present. Participants were asked to carry out their normal activity during the standard 30–60 minute appointment. Video recording was used to capture verbal communication and non-verbal behaviour such as demonstration. The video recorder (JVC Everio GZ MG330HEK) was preset in the consultation room as unobtrusively as possible so that both the audiologist and patient were in frame throughout the consultation.

The video recordings were transcribed in a two-stage process to minimize errors. The recordings were first transcribed and reviewed and then reviewed again while watching the recording to allow correction of any errors. Two researchers (FB and EM; both experienced audiologists who had undertaken training in coding using the BCTTv1) had access to the anonymized transcripts to allow initial independent coding. The BCTTv1 was used as a coding framework for a deductive thematic analysis (Boyatzis, Citation1998). Thematic analysis is a widely used qualitative data analysis method, the purpose of which is to identify patterns within a set of data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The BCTTv1 groups the 93 individual BCTs into 16 hierarchical clusters. shows the how the clusters and BCTs are organized within the taxonomy with their numerical code for easy reference. The full list of BCTs and their definitions is available as an appendix on the IJA website.

Table 2. The 16 clusters and 93 individual behaviour change techniques of the taxonomy (Michie et al, Citation2013).

The whole consultation was coded, using NVivo, to document the range of BCTs employed using definitions given in the BCTTv1. Each researcher coded the transcripts independently using the principles described in the BCTTv1 online training (see http://www.bct-taxonomy.com) which included coding the minimum amount of text necessary to indicate a code. Where insufficient detail was given, the excerpt was not coded to avoid assumptions being made. Before comparing coding, the percentage agreement for the presence of a code was recorded (Boyatzis, Citation1998; p. 155). The coders then compared their independent coding. Differences were resolved by discussion where necessary and final codes were only applied where both reviewers agreed that a code was applicable.

For codes relating to giving information about the natural consequences of behaviour, following advice from the Centre for Behaviour Change at University College London, hearing health consequences were defined as those that impacted largely on the person with the hearing loss alone, such as hearing their own voice or the collateral effect on other symptoms such as tinnitus. Social and environmental consequences were defined as those that impacted on how the person interacted with or perceived the wider world around them. Consequences were categorized as positive, neutral, or negative in tone.

The primary outcome was the range and nature of BCTs employed during the consultation. We also included a count of the frequency of BCT use and calculated averages across consultations as a secondary outcome.

Results

The inter-rater percentage agreement on the presence of a code following independent coding was 83%, which represents a good level of agreement (Boyatzis, Citation1998; p. 155). Across the five services and nine audiologists, 11 BCTs from seven clusters were employed, as shown in . All the consultations included at least one example from each cluster. All the audiologists, regardless of gender, level of experience, and whether they were working in an AQP or non-AQP service (see for definition) carried out some form of goal-setting, gave information about practical social support that would be available following the fitting and the natural consequences of hearing-aid use, gave instruction on how to use the hearing-aid accompanied by a demonstration and practice, and provided additional equipment to support hearing-aid use.

Table 3. Use of behaviour change techniques (BCTs) across nine hearing-aid fittings.

Goals and planning

There are nine individual BCTs included in this cluster as shown in . Consultations included some advice or instructions about hearing-aid use that could be coded as ‘goal-setting (behaviour)’. Examples of such goal-setting included:

‘wear it all the time’ – Audiologist 1

‘pop them in first thing in the morning until last thing at night especially when you first get them, just to get used to them’ – Audiologist 2

‘wear it throughout the day every day’ – Audiologist 5

‘to start with wear them for a few hours a day in a quiet situation’ – Audiologist 10

The goal-setting for behaviour (1.1) that did take place was not collaborative and on no occasion was goal-setting (behaviour) linked to goal-setting (outcome). Four audiologists did refer back to situations where the patient had reported difficulty at a previous appointment, or clarified situations where the patient was experiencing difficulty at the start of the fitting consultation. However, the difficulties were not framed as outcome goals:

‘Now, you did an assessment of your hearing and we decided to try a hearing-aid in your left ear just to see if we could make some of those situations you talked about last time just that little bit easier for you.’ – Audiologist 3

There were no examples of problem-solving (1.2) or goal-setting for outcome (1.3) during the fitting consultations in this sample. Five consultations included advice detailed enough to meet the definition for action-planning (1.4) given in BCTTv1; detailed planning of using the hearing aid including at least one of context, frequency, duration, or intensity (see ). The most detailed example was:

‘what I would like you to do is you get up in the morning, you’ve had a wash, you’ve got dressed, put your hearing aid in, try and leave it there all day and then take it out before you go to bed’ – Audiologist 3.

Social support

Within this cluster, advice about the availability of practical social support (code 3.2) was given in all consultations. The BCTTv1 definition for this code is:

‘Advise on, arrange, or provide practical help (e.g. from friends, relatives, colleagues, buddies, or staff) for performance of the behaviour’.

In all cases, information was given about how to access support services for servicing, battery replacement, and repairs. Accessing practical support was left to the discretion of the person with the hearing loss but audiologists advised on how to access it. Usually advice about when to contact support services was quite general:

‘If you have any problems at all, let us know’ – Audiologist 10

Or related to situations where the hearing aid might break or go wrong:

‘basically it’s a clinic so if you need a new tube or your hearing aid fell apart or something wasn’t working’ – Audiologist 3

It was much less common for people to be given specific advice about practical support that might be available if they had problems using the hearing aid in daily life that were not related to how the hearing aid was working:

‘If you find that you are still really struggling in those kind of noisy places, group situations then, erm come back to us’ – Audiologist 9

Nine of the ten patients attended their appointment alone. In the single case where someone did attend with a partner, the partner did not appear to take an active role in the consultation. The potential for practical or emotional social support from the partner was not discussed.

Shaping knowledge, comparison of behavior, and repetition and substitution

These three clusters have been grouped together because all the consultations observed included instruction (code 4.1), demonstration (code 6.1), and behavioural practice (code 8.1) in how to carry out component behaviours necessary for successful hearing-aid use: cleaning and maintaining the hearing aid; changing the battery; using the controls; and inserting and removing the aid from the ear itself. Some of the instruction related to using the hearing aid in daily life. These references were also coded as goal-setting (behaviour) and sometimes presented as graded tasks (code 8.7):

‘to start with wear them for a few hours a day in a quiet situation… then gradually introduce more sounds and wear them for a bit longer’ – Audiologist 10

Natural consequences

All the consultations included verbal information about either the health or social and environmental consequences of hearing-aid use (codes 5.1 and 5.3). Examples are given in .

Table 4. Examples of consequences of hearing-aid use cited by audiologists.

When giving information about consequences of hearing-aid use, all the audiologists emphasized that getting used to the hearing aid would take time. The potential consequences of not using hearing aids were not discussed. Within this cluster no instances of using the BCTs ‘salience of consequences’; ‘monitoring of emotional consequences’; or ‘anticipated regret’ were identified.

Antecedents

All audiologists provided equipment to assist people in carrying out component activities related to using the hearing aid: spare batteries; cleaning equipment. This was coded as ‘12.5 Adding objects to the environment’. Other BCTs included in this cluster were not identified in this sample.

Other behaviours

All of the consultations sampled also included real ear measurement of the hearing-aid fitting. This involves matching the frequency response of the hearing aid to a target derived from the patient’s audiometric hearing test. None of the audiologists sampled made arrangements to review the fitting face-to-face. Four of the nine arranged a time to follow-up by telephone. The other five audiologists explained that the patient could contact the department if they were experiencing difficulties.

In summary, individual BCTs employed could be clustered within the themes: goals and planning; social support; shaping knowledge; natural consequences; comparison of behaviour; repetition/substitution; and antecedents. All audiologists provided written information on how to operate the hearing aid, how to insert and remove it and how to look after it. Audiologists demonstrated these behaviours and provided opportunities to practice them. They also ensured the aids were comfortable to wear physically and acoustically. These BCTs address only some of the reported needs of people trying hearing aids in terms of reported reasons for non-use. There are therefore opportunities to incorporate additional BCTs into the hearing-aid fitting consultation that might support long term hearing-aid use on the part of people with hearing loss.

Discussion

This study aimed to record and analyse the range and nature of BCTs employed by audiologists during hearing-aid fitting consultations to encourage long term hearing-aid use on the part of their patients. The study revealed that audiologists used BCTs to give information, instruction, and practice in the physical manipulation of the hearing aid(s) but that there may be opportunities to widen the nature of information given and the range of BCTs employed to promote and support long term hearing-aid use.

The results of this observational study support previous findings from observational studies and patient interviews that collaborative behaviours such as goal-setting, action-planning, and problem-solving are not embedded in routine practice in hearing healthcare (Laplante-Levésque et al, Citation2012; Kelly et al, Citation2013; Grenness et al, Citation2015a,Citationb). Previous research has been focused on pre-fitting hearing assessment consultations or post-fitting training and counselling (Knudsen et al, Citation2010). This study extends those findings to include hearing-aid fitting consultations. When they were set, behavioural goals for using the hearing aid(s) were specified by the audiologist and were not specific, measureable, achievable, relevant, or time-bound (SMART) as recommended by goal-setting theorists (Locke & Latham, Citation2006).

If goal-setting for behaviour or outcome had taken place during prior consultations, this was not referred to during the fittings with reference to using the hearing aid to attain those goals. The broad behavioural goal of using a hearing aid was only tenuously related back to individual reported difficulty or outcome goals so that goal-setting was not results-oriented. This is reported to make goal-setting more effective in promoting behaviour change (Siegert & Levack, Citation2015). The findings of this study suggest that the behaviour of the person with the hearing loss is only acknowledged in so far as they need to be able to physically manipulate and look after the hearing aid. Opportunities therefore exist for audiologists to engage their patients in collaborative problem-solving or goal-setting regarding behaviour and outcome. Collaborating to develop a plan for when, how, how often, and where a behaviour will be carried out has been shown to influence behaviour in a number of other contexts, including improving adherence to treatment in long term conditions (Mead & Bower, Citation2002) and is thought to be helpful in promoting habit formation (Lally & Gardner, Citation2013). In future, audiologists could incorporate features that have been shown to be important in improving the effectiveness of goal-setting such as making goals SMARTR: specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-bound, and results-orientated (Locke & Latham, Citation2006; Siegert & Levack, Citation2015).

The active involvement of communication partners in supporting people with hearing loss is thought to be an important determinant of successful hearing-aid use (Ng & Loke, Citation2015; Hickson et al, Citation2014). This is the subject of previous and on-going research (Stark & Hickson, Citation2004; Kramer et al, Citation2005; Knudsen et al, Citation2010, Citation2012; Meyer et al, Citation2014; Ekberg et al, Citation2015). Although practical support was offered to all patients, this related solely to support available from hearing services. The provision of social and emotional support outside the direct practical help available from hearing services was not discussed. The low level of involvement of significant others seen in this study supports the need for the on-going work in this area such as that being carried out by Meyer et al into the support for and potential barriers to the involvement of significant others in hearing healthcare (Meyer et al, Citation2015).

Patients were provided with verbal information about hearing aids particularly to build knowledge and skills about component behaviours that contribute to successful hearing-aid use such as changing the battery, cleaning the hearing aid and inserting and removing it. Information about hearing-aid use often pertained to limitations rather than advantages of aid use. The potential psychoacoustic and psychosocial consequences of not using hearing aids were rarely discussed during fitting appointments. Knowledge about the benefits of a particular behaviour and the consequences of not engaging in the behaviour are both potentially important determinants of whether that behaviour occurs, in terms of psychological capability and its influence on motivation (Michie et al, Citation2014).

The conceptual map in also suggests that patients could benefit from being provided with prompts or cues for hearing-aid use. This BCT was not seen in any of the fitting consultations observed. Providing prompts or reminders to put hearing aids on in a particular context may be a way to influence behaviour, particularly if the aim is to promote habit formation (Lally & Gardner, Citation2013). Forgetting to put hearing aids in is a reported reason for non-use of hearing aids (McCormack & Fortnum, Citation2013). This may be because people lack clear naturally occurring cues for hearing-aid use. The nature of hearing loss, being slow in onset with the level of difficulty fluctuating according to context, means that consistent simple cues may be difficult to identify. This is in contrast to, for example, the behaviour of wearing reading glasses. The cue for this behaviour is not being able to see to read at any given moment. This cue is either present or absent; cannot see to read or can see to read. Because hearing or not hearing is rarely this black and white, prompts to act are harder to identify and apply consistently. The provision of an external cue may therefore be helpful in prompting hearing-aid use and embedding it into the normal routine (Lally & Gardner, Citation2013).

Strengths and limitations

This study aimed to observe and record 10 hearing-aid fittings across a range of geographical areas within England and with audiologists with a range of experience. The figure of 10 audiologists represented a balance between the constraints of data collection and analysis and the wish to obtain a representative sample of variation in behaviour. In the event, one audiologist withdrew consent during the fitting and, in accordance with the protocol, their data were not included in the analysis of behaviour change techniques. However, the uniformity of behaviour across the remaining nine consultations suggests that the loss of this data had minimal impact on the conclusions drawn. The consistency in audiologist behaviours, despite their differing clinical experience, suggests that they may be representative of the way audiologists work in hearing-aid fitting consultations across the NHS in England. However, further study with a larger sample would be necessary to confirm this. This could be further strengthened by a more robust a priori consideration of coding consistency. In this study, coding consistency was only quantitatively assessed retrospectively. Despite the intention to record consultations where people had no previous experience of using a hearing aid, two patients had worn hearing aids before. This occurred due to timetabling issues within the departments concerned. We did not quantitatively assess differences in the range and nature of BCTs in the two types of consultation. However a subjective review by both coders suggested no apparent differences between first fitting consultations and refits, and the decision was made to include the data from the refitting consultations in the analysis. It is possible that a sample composed entirely of first fittings would reveal a different profile of BCT use.

This study only considered the fitting consultation. It is possible that some relevant BCTs may have been employed in previous or subsequent appointments in the patient journey. However, the work of Grenness and others suggests this is unlikely (Laplante-Levésque et al, Citation2012; Kelly et al, Citation2013; Grenness et al, Citation2015a,Citationb).

Some people can find the presence of a video camera intrusive and this has been shown to influence the profile of participants consenting to take part in video studies (Coleman, Citation2000). However there is no evidence that the presence of a camera has a significant influence on clinician or patient behaviour, at least during primary care consultations (Coleman, Citation2000). All participants and patients were advised in the participant information sheet that they could ask for the video recorder to be turned off at any time without prejudicing their care or employment status in any way. All participants and patients could also withdraw from the study at any time without giving a reason and, indeed, one audiologist did so. The researcher was not present during recording of the consultation to allow the appointment to proceed under the most natural possible circumstances.

Conclusions

This observational study of audiologist behaviour in hearing-aid fittings has identified opportunities to use additional BCTs that might influence hearing-aid use on the part of people with hearing loss who are being fitted with hearing aids. The challenge for audiologists and researchers is to evaluate the effect on hearing-aid use and hearing health-related outcomes of: collaborating with patients to develop a behavioural plan for hearing-aid use that includes goal-setting, action-planning, and problem-solving; involving significant others or communication partners; providing information on the benefits of hearing-aid use or the consequences of non-use; and giving advice about using prompts or cues for hearing-aid use. There is support for using such BCTs in the context of other long term conditions. These gaps present potential initial targets for researchers seeking to improve hearing-aid use amongst adults with acquired hearing loss.

| Abbreviations | ||

| AQP | = | Any qualified provider |

| BCT | = | Behaviour change technique |

| BCTTv1 | = | Behaviour change technique taxonomy (version 1) |

| SMS | = | Self-management support |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participating patients and carers, departments, and individual clinicians who took part in this research.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barker F., Mackenzie E., Elliott L., Jones S. & de Lusignan S. 2014. Interventions to improve hearing aid use in adult auditory rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, CD010342. [Epub ahear of print]. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010342.pub2.

- Barker F., Munro K.J. & de Lusignan S. 2015. Supporting living well with hearing loss: A Delphi review of self-management support. Int J Audiol, 54, 691–699.

- Barker F., Atkins L. & de Lusignan S. 2016. Applying the COM-B behaviour model and Behaviour Change Wheel to develop an intervention to improve hearing aid use in adult auditory rehabilitation. Int J Audiol, [Epub ahear of print]. DOI: 10.3109/14992027.2015.1120894.

- Boyatzis R.E. 1998. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. London: Sage.

- Braun V. & Clarke V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol, 3, 77–101.

- Brooks D.N. & Johnson D.L. 1981. Pre-issue assessment and counselling as a component of hearing-aid provision. Br J Audiol, 15, 13–19.

- Caldwell K. & Atwal A. 2005. Non-participant observation: Using video tapes to collect data in nursing research. Nurse Res, 13, 42–54.

- Chisolm T.H., Johnson C.E., Danhauer J.L., Portz L.J., Abrams H.B. et al. 2007. A systematic review of health-related quality of life and hearing aids: Final report of the American Academy of Audiology Task Force On the Health-Related Quality of Life Benefits of Amplification in Adults. J Am Acad Audiol, 18, 151–183.

- Coleman T. 2000. Using video-recorded consultations for research in primary care: Advantages and limitations. Family Practice, 17, 422–427.

- Coulson N.S., Ferguson M.A., Henshaw H. & Heffernan E. 2016. Applying theories of health behaviour and change to hearing health research: Time for a new approach. Int J Audiol, [Epub ahear of print]. DOI: 10.3109/14992027.2016.1161851.

- Ekberg K., Meyer C., Scarinci N., Grenness C. & Hickson L. 2015. Family member involvement in audiology appointments with older people with hearing impairment. Int J Audiol, 54, 70–76.

- Ferguson M., Brandreth M., Brassington W., Leighton P. & Wharrad H. 2015. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the benefits of a multimedia educational program for first-time hearing aid users. Ear Hear, Nov 12 [Epub ahear of print].

- Gopinath B., Schneider J., Hartley D., Teber E., McMahon C.M. et al. 2011. Incidence and predictors of hearing aid use and ownership among older adults with hearing loss. Ann Epidemiol, 21, 497–506.

- Grenness C., Hickson L., Laplante-Levésque A. & Davidson B. 2014. Patient-centred audiological rehabilitation: Perspectives of older adults who own hearing aids. Int J Audiol, 53, S68–S75.

- Grenness C., Hickson L., Laplante-Levésque A., Meyer C. & Davidson B. 2015a. Communication patterns in audiologic rehabilitation history-taking: audiologists, patients, and their companions. Ear Hear, 36, 191–204.

- Grenness C., Hickson L., Laplante-Levésque A., Meyer C. & Davidson B. 2015b. The nature of communication throughout diagnosis and management planning in initial audiologic rehabilitation consultations. J Am Acad Audiol, 26, 36–50.

- Hickson L., Meyer C., Lovelock K., Lampert M. & Khan A. 2014. Factors associated with success with hearing aids in older adults. Int J Audiol, 53, S18–S27.

- Hickson L., Worrall L. & Scarinci N. 2007. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the active communication education program for older people with hearing impairment. Ear Hear, 28, 212–230.

- Kelly T.B., Tolson D., Day T., McColgan G., Kroll T. et al. 2013. Older people's views on what they need to successfully adjust to life with a hearing aid. Health Soc Care Community, 21, 293–302.

- Knudsen L.V., Laplante-Levésque A., Jones L., Preminger J.E., Nielsen C. et al. 2012. Conducting qualitative research in audiology: A tutorial. Int J Audiol, 51, 83–92.

- Knudsen L.V., Öberg M., Nielsen C., Naylor G. & Kramer S.E. 2010. Factors influencing help seeking, hearing aid uptake, hearing aid use and satisfaction with hearing aids: A review of the literature. Trends Amplif, 14, 127–154.

- Kramer S.E., Allessie G.H., Dondorp A.W., Zekveld A.A. & Kapteyn T.S. 2005. A home education program for older adults with hearing impairment and their significant others: a randomized trial evaluating short- and long-term effects. Int J Audiol, 44, 255–264.

- Lally P. & Gardner B. 2013. Promoting habit formation. Health Psychol Rev, 7, S137–S158.

- Laplante-Levésque A., Knudsen L.V., Preminger J.E., Jones L., Nielsen C. et al. 2012. Hearing help-seeking and rehabilitation: Perspectives of adults with hearing impairment. Int J Audiol, 51, 93–102.

- Leeman J., Baernholdt M. & Sandelowski M. 2007. Developing a theory-based taxonomy of methods for implementing change in practice. J Adv Nurs, 58, 191–200.

- Locke E.A. & Latham G.P. 2006. New directions in goal-setting theory. Curr Dir Psychol, 15, 265–268.

- McCormack A. & Fortnum H. 2013. Why do people fitted with hearing aids not wear them? Int J Audiol, 52, 360–368.

- Mead N. & Bower P. 2002. Patient-centred consultations and outcomes in primary care: A review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns, 48, 51–61.

- Meyer C., Hickson L., Lovelock K., Lampert M. & Khan A. 2014. An investigation of factors that influence help-seeking for hearing impairment in older adults. Int J Audiol, 53, S3–S17.

- Meyer C., Scarinci N., Ryan B. & Hickson L. 2015. “This is a partnership between all of: Audiologists' perceptions of family member involvement in hearing rehabilitation”. Am J Audiol, 24, 536–548.

- Michie S., Atkins L. & West R. 2014. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. London: Silverback.

- Michie S., Richardson M., Johnston M., Abraham C., Francis J. et al. 2013. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med, 46, 81–95.

- Michie S., West R., Campbell R., Brown J. & Gainforth H. 2014. ABC of Behaviour Change Theories. London: Silverback.

- Michie S., Johnston M., Abraham C., Lawton R., Parker D. et al. 2005. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: A consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care, 14, 26–33.

- Michie S., Ashford S., Sniehotta F.F., Dombrowski S.U., Bishop A. et al. 2011. A refined taxonomy of behaviour change techniques to help people change their physical activity and healthy eating behaviours: The CALO-RE taxonomy. Psychol Health, 26, 1479–1498.

- Mulrow C.D., Aguilar C., Endicott J.E., Velez R., Tuley M.R. et al. 1990. Association between hearing impairment and the quality of life of elderly individuals. J Am Geriatr Soc, 38, 45–50.

- Ng J.H. & Loke A.Y. 2015. Determinants of hearing-aid adoption and use among the elderly: A systematic review. Int J Audiol, 54, 291–300.

- Norman M., George C.R. & McCarthy D. 1994. The effect of pre-fitting counselling on the outcome of hearing aid fittings. Scand Audiol, 23, 257–263.

- Pearson M.L., Mattke S., Shaw R., Ridgely M.S. & Wiseman S.H. 2007. Patient Self-Management Support Programs. Rockville, USA: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Siegert R.J. and Levack W.M.M. (eds.) 2015. Rehabilitation Goal Setting: Theory, Practice and Evidence. Florida: CRC Press.

- Stark P. & Hickson L. 2004. Outcomes of hearing aid fitting for older people with hearing impairment and their significant others. Int J Audiol, 43, 390–398.

- Thoren E.S., Öberg M., Wänström G., Andersson G. & Lunner T. 2014. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the effects of online rehabilitative intervention for adult hearing-aid users. Int J Audiol, 53, 452–461.