Abstract

Objective: Supporting audiologists to work ethically with industry requires theory-building research. This study sought to answer: How do audiologists view their relationship with industry in terms of ethical implications? What do audiologists do when faced with ethical tensions? How do social and systemic structures influence these views and actions?

Design: A constructivist grounded theory study was conducted using semi-structured interviews of clinicians, students and faculty.

Study sample: A purposive sample of 19 Canadian and American audiologists was recruited with representation across clinical, academic, educational and industry work settings. Theoretical sampling of grey literature occurred alongside audiologist sampling. Interpretations were informed by the concepts of ethical tensions as ethical uncertainty, dilemmas and distress.

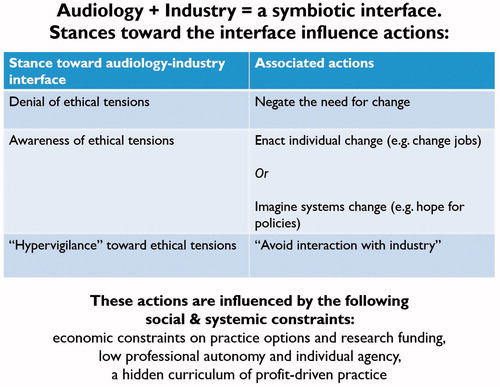

Results: Findings identified the audiology–industry relationship as symbiotic but not wholly positive. A range of responses included denying ethical tensions to avoiding any industry interactions altogether. Several of our participants who had experienced ethical distress quit their jobs to resolve the distress. Systemic influences included the economy, professional autonomy and the hidden curriculum.

Conclusions: In direct response to our findings, the authors suggest a move to include virtues-based practice, an explicit curriculum for learning ethical industry relations, theoretically-aligned ethics education approaches and systemic and structural change.

Introduction

Educating and supporting audiologists to work ethically in relation to industry – i.e. hearing device manufacturers including their funding, products and personnel – is necessary yet daunting. While other professions such as medicine, pharmacy and physiotherapy have been the subject of study and discussion (e.g. Stark, Citation2016), the issue is both urgently important and particularly opportune for study within audiology. As an academic field, audiology is frequently partnered with and supported by industry on the premise that research and development can be optimised through academia–industry collaboration (Chau, Moghimi, and Popovic Citation2013; Crukley et al. Citation2012). As a regulated health profession in our Canadian jurisdiction, audiology is one of only two health professions permitted to exercise the controlled act of prescribing hearing devices (Government of Ontario Citation1991). These two contextual factors mean that hearing devices represent not only a tool for helping people hear, but also a very real source of funding for research and income for dispensing audiologists. This reality raises ethical, educational and research questions.

Background

Conflict of interest presents as one of the most explicit ethical issues at the audiology–industry interface (Crukley et al. Citation2012; Windmill, Cunningham, and Preminger Citation2004; Ng, Bartlett, and Lucy Citation2010, Citation2013). In the research realm, audiology researchers face opportunities and pressures to conduct scientific research to inform hearing device development and outcome measurement within a climate of limited public funding. Researchers may find themselves dependent on industry funding, yet under-prepared to navigate the complexities of such a relationship and the transparency appropriate therein (Crukley et al. Citation2012). In the clinical realm, clinicians may find themselves enrolled in incentive programmes designed by their industry-tied employers. While the profession has codes of ethics and regulatory bodies, and universities and research hospitals offer conflict of interest and research (mis)conduct policies, ethical challenges arising in everyday practice persist for audiologists (American Academy of Audiology Citation2011; American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Citation2010; Phelan, Wright, and Gibson Citation2014; Windmill et al. Citation2010). These everyday ethics issues may stem from, but also extend beyond, conflicts of interest and associated guidelines, and they require further consideration.

To examine these ethical issues, this article will use the umbrella term of ethical tensions to refer to any ambiguity about what is right and what should be done. More specifically, under the umbrella of ethical tensions, are the concepts of ethical uncertainty, ethical distress and ethical dilemmas. Individuals experience ethical uncertainty when unsure of whether or not a situation is in fact ethically problematic, and if so, what theories or principles apply. They face ethical distress when unable to enact their own moral principles (personal beliefs about right and wrong) due to systemic constraints or barriers (Pauly, Varcoe, and Storch Citation2012). Ethical dilemmas present at least two mutually exclusive possible courses of action, with their own unique benefits and/or drawbacks. It is important to consider that more than one ethical tension can be experienced in any given situation and at both individual (micro) and systemic (macro) levels (Durocher et al. Citation2016). It is demoralising when an individual lacks a clear language for articulating their ethical concerns and the systemic constraints are not clearly understood or perceived as controllable (Durocher et al. Citation2016; Pauly, Varcoe, and Storch Citation2012). Over a prolonged period of time, negotiating ethical tensions can manifest as emotional distress, physiological stress, compassion fatigue and burnout, disengagement from patients and attrition (Pauly, Varcoe, and Storch Citation2012). This is especially concerning at present as workforce shortages are looming in audiology (Windmill and Freeman Citation2013) and working conditions may lead to a deteriorating moral climate (Simpson et al. Citation2018). Audiology is certainly not alone in its experience of ethical tensions (Bushby et al. Citation2015; Durocher et al. Citation2016; Jameton Citation1985; Kinsella, Bossers, and Ferreira Citation2008; Opacich Citation1997; Storch and Rodney Citation2009).

In addition to concern for clinicians’ ethical tensions, ultimately, we must be concerned about the effects of ethics issues on patients and the public. For example, there are signs of growing public distrust in audiologists as well as audiology as a profession (DeChillo Citation2012; Consumer Reports Citation2014; CBC Marketplace Citation2013). And beyond distrust, patients may actually be harmed if audiologists possess only a surface-level understanding of ethics, and as a result have difficulty identifying ethical tensions in their practice. For example, the self-perception and well-being of patients and research participants can be influenced by language and messaging that implicitly or explicitly construct disability, impairment and the associated physical, social and cultural implications (Phelan, Wright, and Gibson Citation2014). Patients are exposed to messages about their disability in audiology clinics, research laboratories (e.g. in study recruitment documents) or through product promotional material engagement. These influences, while seemingly subtle, can have far-reaching effects on how patients view their audiologists, themselves, and their impairment and disability in the broader societal context (Phelan, Wright, and Gibson Citation2014).

Avoiding interaction with industry altogether is infeasible in audiology and likely detrimental given the enriched knowledge generation opportunities when clinicians, researchers and industry members interact (Chau, Moghimi, and Popovic Citation2013; Crukley et al. Citation2012). From the broader rehabilitation research world, Chau, Moghimi, and Popovic (Citation2013) suggest that a synergistic knowledge and product creation opportunity exists in the mutual collaboration of patients, practitioners, researchers and technological developers. This collaboration, however, must be carried out in a thoughtful and informed manner in order to ensure benefit and avoid harm such as abuse of power or the presentation of false promises to patients or clinicians (Chau, Moghimi, and Popovic Citation2013; Phelan, Wright, and Gibson Citation2014).

Despite the pervasiveness of industry relations in audiology, there is scant empirical and theoretical literature in audiology on the topic of ethics in general, and specifically with respect to industry. A 2014 systematic review revealed just 27 articles published in a 20-year period (1980–2010) on the topic of ethics in audiology (Naude and Bornman Citation2014). Further, the review found that most of these articles were largely philosophical, suggesting a need for investigation of the direct effects of psychosocial, economic, sociological, legal, cultural, religious and organisational factors to be considered in future research into ethics and audiology. The reviewed articles focussed on issues in private practice, business ethics and malpractice. Articles addressed neither the perspective of the patient, nor academia–industry relations (instead of focussing on general ethics issues from the perspective of audiologists). A more recent paper by Canadian scholars (Coolen, Caissie, and Aiken Citation2012) included perspectives of both audiologists and patients, and found that patient perspectives differed from audiologists in terms of what are considered to be ethical or unethical clinician–industry relations. For example, a scenario in which audiologists would be given lunch during an industry “lunch and learn”, patients were more likely to rate this as ethically problematic (Coolen, Caissie, and Aiken Citation2012). These findings differ from those of prior studies (Tyler et al. Citation2002; Hawkins, Hamill, and Kukula Citation2006) on which the Coolen et al. survey was based, wherein audiologists did perceive conflicts of interest and ethical issues rather similarly to consumers/patients. However, audiologists’ lack of sensitivity to less obvious conflicts of interest prompted the authors of this study to suggest more ethics education in audiology (Hawkins, Hamill, and Kukula Citation2006). This suggests a need for audiology to critically attend to ethical sensitivity and education related to both a) recognising ethical tensions in practice and b) enacting the knowledge and tools to negotiate arising ethical tensions.

As an early step towards these goals, we require deeper understanding of audiologist’s perspectives and approaches in relation to industry to enable the field to set a research, education and workplace-support/professional development agenda in relation to ethical industry relations. This study, therefore, used a constructivist grounded theory research approach to ask: How do audiologists view their relationship with industry in terms of ethical implications? What do audiologists do when faced with ethical tensions? How do social and systemic structures influence these views and actions?

Methodology

Constructivist grounded theory was selected as our methodology because it is most appropriate when little is known on the specific research topic, when the topic of interest involves social experiences or processes, and/or when interested in tacit thoughts and processes that can be made at least partially explicit. Further, a constructivist (as opposed to post-positivist) approach to grounded theory supports making connections with extant theory and the researchers’ and participants’ experiential knowledge, to enhance theoretical understanding (Charmaz Citation2006; Meston and Ng Citation2012; Ng, Lingard, and Kennedy Citation2013). The University of Toronto research ethics board reviewed and approved the study protocol.

Sampling and recruitment

A purposive sample of 19 North American audiologists was recruited as follows. Each team member, other than the first author, e-mailed research ethics board-approved recruitment text to their listservs and networks inviting interested individuals to contact the first author should they wish to participate in an interview. Sampling began purposively for maximum variation, which means even representation of audiologists’ clinical practice settings (private practice and hospital-based), academic settings (universities and academic hospitals), industry settings (hearing aid and implantable devices) and student representatives (purely clinical and clinical plus research). Following the maximum variation stage, theoretical sampling occurred (Charmaz, Citation2006; Meston and Ng, Citation2012; Ng, Lingard, and Kennedy Citation2013). Theoretical sampling is another form of purposive sampling, which aims to further refine the theory under development by seeking additional and contrasting cases, individuals, or other data sources that may fill gaps in understanding (Charmaz, Citation2006; Meston and Ng, Citation2012; Ng, Lingard, and Kennedy Citation2013). In this study, theoretical sampling manifested as initial analysis of the first few interviews revealed useful insight from audiologists who have worked across settings/roles (e.g. academia versus industry versus clinical practice). Then, sampling specifically aimed to recruit participants who had or currently worked in multiple roles. Initial analysis also pointed towards the theoretical sampling of document data sources like codes of ethics and ethics education modules from popular online sources, in order to gain a broader sense of how ethics and industry are discussed in the field at large, beyond this study’s participants. Data collection continued until sufficient information was gained to declare theoretical sufficiency. Theoretical sufficiency is constructivist grounded theory’s preferred term over saturation; it represents the point in grounded theory analysis at which sufficient data has been collected and analysis has progressed far enough to make justifiable theoretical claims (Charmaz Citation2006; Meston and Ng Citation2012; Ng, Lingard, and Kennedy Citation2013; Dey Citation1999).

Data collection

Data collection entailed semi-structured interviews probing participants on their views of industry and experiences with ethical tensions in relation to it. The following broad topic guide and associated probes guided each interview:

What participants think about their, and their profession’s, relations(hip) with the hearing device industry (e.g. Tell me about your interactions with the hearing device industry? What do you think about your/the profession’s current relationship with the hearing device industry?)

What participants had experienced and how they had learned about working with industry (e.g. Tell me about any education courses/workshops/programmes that have influenced how you work with industry, or how you perceive industry? Could you give me some examples of how you currently interact with industry? Any cautions or concerns to share? Any positive experiences you would like to share?

Views on the ethical implications of the audiology–industry interface or any ethical tensions that had arisen in practice at this interface.

Audiologists’ perceived guiding framework or touchstone to ensure their practice was ethical in relation to industry.

Importantly, instead of immediately assuming that participants would be aware of and concerned about ethical tensions, these insights were brought up by participants on their own. However, at times participants did not generate any examples of ethical tensions on their own. In these cases, the interviewer prompted participants to share any stories of compromises, uncertainty, workarounds or critical incidents (Ng, Bartlett, and Lucy Citation2012) from industry related practice.

To enable participation despite geographic distance, interviews took place by phone, for a maximum of 1 h, and were all conducted by SN (for consistency). The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis. Transcripts were entered into NVivo software in order to organise and manage data for analysis (QSR International Pty Ltd. Citation2008).

Data analysis

Analysis began with initial coding, wherein each unit of meaning within the dataset was coded literally to label its meaning (e.g. “incentive program”) (Charmaz Citation2006). Focussed coding occurred next, grouping related codes together into representative conceptual categories (e.g. “business models drive practice in relation to billing processes”) (Charmaz Citation2006). Then theoretical coding related categories to one another in an effort to identify processes and/or to extend extant theory as appropriate (e.g. decision-making blends basic research evidence, clinical experience, patient preference and business models) (Charmaz Citation2006). To ensure rigour, codes were continually compared to one another within and between data sources. Instances of contradiction relative to developing codes, categories and theoretical explanations were deliberately sought. This iterative process of comparison informed theoretical sampling of additional participants or other data sources (e.g. documents).

Theoretical sampling – to reiterate, the process of soliciting more/specific data types/sources to help elaborate and refine the theoretical insights developing from ongoing analysis – led to questioning what current ethics conversations were happening in the field (if any). Therefore, to contextualise the insights developing through our ongoing analysis, a convenience sample of grey literature (non-peer-reviewed contributions such as professional magazine articles) and related literature was gathered. These articles served only to provide broader contextual insight into ethical issues within the field of audiology (beyond our small sample of audiologists). Specifically these grey literature sources offered a view of the field’s way of speaking to (industry) ethics issues and opportunities to confirm or contradict information from the stories of our participants. These data sources were consulted purposively in relation to ongoing interview analysis. Theoretical sufficiency was declared after 19 interviews (see for participant descriptions) had been conducted and analysed and 17 grey literature documents (see for grey literature descriptions) had been collected and reviewed. Theoretical sufficiency was met when there were cogent theoretical explanations relative to the study’s research questions, no new analytic insights were arising, and thus data collection and analysis could stop (Charmaz, Citation2006; Meston and Ng, Citation2012; Ng, Lingard, and Kennedy Citation2013; Dey, Citation1999).

Table 1. Participant profiles.

Table 2. Grey literature sample.

All coding was led by experienced grounded theorist SN. Other members of the research team supported analysis during teleconference meetings, during which SN presented developing codes and categories for group discussion. The research team consisted of two experienced, qualitative researchers – one a registered audiologist and education scientist (SN) and one a registered occupational therapist and ethics researcher (SP), a hearing scientist working within industry (JC), a clinician working in an independent clinician-owned private practice (LP), an audiology faculty member (SA) and a research coordinator (EK). The team was carefully selected to cover the necessary methodological expertise (qualitative researchers who have published on qualitative methodology in reputable peer-reviewed journals and textbooks) (e.g. Phelan and Kinsella Citation2013; Meston and Ng Citation2012; Ng, Lingard, and Kennedy Citation2013), theoretical expertise (professional ethics and health professions education experts) (Durocher et al. Citation2016; Kinsella et al. Citation2015; Ng, Kinsella, et al. Citation2015) as well as broad audiology representation (team members from academia, industry and private practice).

Findings

The findings address the study’s three main research questions and present them in sequence here for clarity. First, this findings section will outline the perceptions of the audiology-industry interface from the perspectives of our participants. Then, it describes what audiologists in our study tend to do with regard to ethical tensions at the audiology-industry interface. Many participants struggled to name ethical tension examples but when prompted to think beyond major ethical infractions and to consider everyday practice uncertainties, their stories then flowed freely and demonstrated a pervasiveness of ethical tensions. This aspect of the study’s findings suggests that while not necessarily sensitised (or, perhaps, desensitised) to what might constitute an ethical issue, audiologists are faced with them constantly. Finally, this findings section explores the perceived influence of social and systemic structures upon audiologists’ attempts at ethical practice at the audiology-industry interface. NB: The “type” of audiologist and participant pseudonyms is indicated before/after each participant quotation and throughout the findings, we mention how the grey literature supported our assertions, when appropriate. While each research question is addressed in sequence, summarises and integrates the findings for each research question and how they interrelate.

Figure 1. Summary of findings. Audiologists’ perspectives, stances, actions and systemic influences re ethical industry relations.

How audiologists “see” the audiology-industry interface and its ethical implications: necessary relationship or relationship by necessity?

A symbiotic interface

All of our participants perceived the relationship between the hearing device industry and the profession of audiology as symbiotic, meaning mutually necessary for existence. For example, a hearing aid manufacturer-based audiologist (pseudonym: Dave) speaks of the industry–clinician relationships as a way to improve understanding and optimise outcomes:

In order for the hearing care professional to get the most out of the solutions, they need to interact with industry so they understand exactly how these solutions work. […] And if I was the patient, I would expect that to be absolutely the case. […] You know, I do expect an industrial-clinician relationship to take place and it’s that cooperation that leads to better outcomes for the patient.

Denial, awareness and hypervigilant stances

Importantly, though viewed as mutually beneficial for meeting the demands of current practice, this did not mean audiologists saw the relationship as wholly positive or ethically neutral. Participants’ perspectives towards industry as it related to ethical practice ranged from denying any potential ethical issues, to generally tolerant awareness of potential issues, to hypervigilance as a result of ethical concerns. Participants mostly spoke in terms of the middle of this continuum (aware and tolerant of potential ethical issues). Although none of our participants placed themselves on the hypervigilant end of this continuum, several shared stories about other audiologists who they viewed as overly cautious towards industry. On the other end of this continuum, a minority of our participants saw nothing negative at the audiology-industry interface, completely denying the potential for ethics-related issues to arise in relation to industry.

Note that most individual participants held multiple perspectives towards the audiology-industry interface. That is, findings do not firmly categorise any one participant into denial, awareness, and hypervigilance as a fixed view. Indeed, while participants may more strongly lean towards one position on the continuum, they also frequently contradicted their own positions within their interviews. This variability within participants speaks to the complexity and subjectivity of the topic matter. In light of the perception of the audiology-industry interface as symbiotic, and the range of perspectives towards the interface and its ethical implications, next the findings explain what audiologists tend to do – how they act/respond – in relation to industry.

How audiologists respond to the question of ethics at the audiology-industry interface: from denial to avoidance

Denial, change and avoidance

In describing their actions or responses in relation to ethical issues or tensions at the audiology-industry interface, our participants: negated/deflected a need for system-wide change, enacted individual change or workarounds to practice ethically, or imagined a more ethical system. They also spoke of others who would avoid interaction with industry altogether. These categories of (re)actions to the overall ethical question of practicing at the audiology-industry interface were related to the previously described views towards the ethics of the audiology-industry interface as follows: audiologists who were described as hypervigilant also tended to avoid industry altogether. When speaking in terms of tolerant awareness of potential ethical tensions, audiologists also imagined/hoped for systems change, though some gave examples of enacting individual change when they experienced ethical distress (e.g. quitting their jobs!). The minority of participants who denied any potential ethical issues due to industry also negated any perceived call for change or need for caution.

relates the findings in response to our first research question (participants’ views towards ethical practice in relation to the audiology-industry interface) and our second research question (participants’ responses or actions in relation to ethical tensions in relation to industry).

Table 3. How audiologists view and respond to potential ethics issues at the audiology-industry interface.

Evidence, transparency and patient values

Importantly, when our participants were asked to describe their guiding framework, if any, for enacting ethical practice in relation to the audiology-industry interface, the common themes of evidence, transparency and patient values arose across participants. One participant, a multi-practice manager (pseudonym: Elliot), summarised all three of these themes in his response:

One example would be ‘fit to target’1 […] Targets are important. […another] guiding thing I use is the needs of the patients. The other thing is clarity. I always try to be as transparent as possible.

While participants noted the ability to use research evidence, especially evidence-based practice (EBP), as a defence against any potential conflict of interest, they also noted that evidence alone – while reassuring – was insufficient to guide practice. For instance, one participant, who worked within the hearing aid industry, noted that research evidence will always be insufficient when making decisions about which device to prescribe for a particular patient, and thus other factors must inevitably play a role (e.g. customer service from different companies, clinicians’ experience, and patients’ own preferences). Interestingly none of our participants mentioned ethical guidelines or formal principles as a guiding framework for ethical practice, despite the easily accessible grey literature reviewed focussing on such guidelines and principles ().

How audiologists’ ethical practice in relation to industry is shaped by social and systemic forces: the economy, autonomy and the hidden curriculum

The economy

The dynamic landscape of practice, particularly the economy and its influences on the job market and profession business models, was seen to be divided between public and private interests. Economic concern also influenced the academic research funding climate and shaped the views and actions of faculty researchers towards industry. While faculty note the potential for innovation and advancement of intellectual contributions that arise from collaborating with industry, they do also acknowledge the funding incentives. As one faculty member admitted, “that’s where the money is”.

Limited autonomy and individual agency

Given individual financial needs, participants also experienced some ethical distress as a result of constraints upon perceived individual agency – the capacity to act autonomously – relative to the professions’ climate and structure. Yet not all experience this as distress in relation to industry; some view industry as necessary and helpful given the distress caused by the larger funding issues for audiology services. As audiology jobs have decreased in Canadian hospitals (where the focus may be more diagnostic), and moved more into the increasingly commercialised private sector (where the focus is on hearing aid dispensing), opportunities to control how one practices and to earn a decent living have changed. Industry support thus becomes very necessary to private practice and while this leads to increased reliance on industry it also sets up greater autonomy from physicians. As a faculty member with former private practice (pseudonym: Isabel) experience noted:

Most of us actually need to work in private practice because there are less and less positions in public settings. We are seeing cuts, and even recently here in our general hospital, there were some cuts in audiology positions, and even those that have been work[ing] for 15 years are losing their job[s]. In the beginning people were saying oh, that’s too bad, but I’m thinking maybe it’s good for us. In the beginning of audiology, we were working essentially in the health setting, meaning the hospital setting, and we had to work under supervision [of physicians].

Learning from the hidden curriculum

Our student participants were particularly vulnerable to the structural constraints of audiology as their new field of work. For example, one clinical student (pseudonym: Hanna) expressed the following:

The primary concern of private practice in general is profit, it’s not public interest that is what it gets down to. So I feel uncomfortable about that. And my supervisor […] says that she doesn’t think any audiologists really like to work in private practice and I don’t really know if that’s true, but in any case I think she feels uncomfortable with it too. And she does have sales pressure, they give her a report every month of all the clinics in the area and how many hearing aid sales they have made.

This example highlights a pervasive finding from our data. Learning about audiology–industry relations occurs through a hidden curriculum, not simply from formal education processes, or the adoption of codes of ethics or decision-making guides. The hidden curriculum refers to informal yet important lessons transmitted through the norms, values, and beliefs of those within the field (Hafferty and Franks Citation1994). Our grey literature review showed that most of the formal writing on the topic in the field focussed upon ethical principles and guidelines, and not on everyday ethical tension relating to industry. Grey literature that did focus on ethical tensions tended to focus on broad (not industry-specific) ethical tensions and more specifically, ethical dilemmas as opposed to uncertainty or distress.

Interestingly one of our participants, an industry leader, who held a stance of denial about potential ethical issues at the audiology-industry interface, stated that we cannot educate or regulate ethics. Instead he suggested that we should view ethics as personal and not as business of public systems. This view was not represented by other participants in our study or by our review of the grey literature. Instead, more commonly, participants recognised the imperfect realities of their current professional climate, framed industry relationships as symbiotic and focussed on the positives for patients and practitioners that derive from these relationships.

Discussion

This study’s findings identified a prevalent understanding of the audiology–industry relationship as symbiotic but not necessarily positive. Audiologists’ positions on ethical tensions at the audiology-industry interface ranged from denial to tolerant awareness of potential tensions, to (supposed) hypervigilance against any potential ethical infractions. Their responses and approaches to ethical tensions in relation to industry seemed to relate to these stances, ranging from the two extremes: negating or deflecting a call for any systems change to (reportedly) avoiding all interaction with industry, a finding consistent with a similar grounded theory study conducted in psychiatry (Stark et al. Citation2016). Importantly, the hypervigilant stances and avoidant actions were not identified within our participants, but rather reported as existing in others whom our participants had observed.

This discussion section will work on moving from our findings to theoretically aligned recommendations and implications. First, it describes how audiology could move from a narrow application of EBP – the guiding model named by our participants – towards one that also opens space for virtues-based practice. Next, it suggests how to move beyond the current state of a hidden curriculum for ethics education towards a purposeful, explicit curriculum on ethics. And finally, it makes suggestions for what educational approaches would work well for supporting both ethical clinical practice and ethical research practice.

Expanding our conceptions of practice to include values

EBP was the dominant practice model noted by participants as helpful or relevant when asked how they ensure practicing ethically in relation to industry. This finding is unsurprising given audiology’s strengths in striving for EBP (Moodie, Johnson, and Scollie Citation2008). Participants described elements of EBP, including the best available research evidence, their own expertise and patients’ preferences, as a useful touchstone to guide ethical practice. These findings are consistent with studies of medical students (Holloway Citation2015). They also echo a medical student study by suggesting that the reliance on EBP can be helpful at times but naïve at others. What is considered evidence-based, particularly in a field like audiology in which much research is industry-partnered, is ironically subject to the same risks of conflict and bias as is everyday practice (Holloway Citation2015). Further, the way of thinking about practice embedded within EBP tends to be solution-oriented, while issues of everyday ethical tensions rarely have clear-cut solutions. This study’s data and grey literature reiterated what our literature review showed. That is, existing resources and approaches available to guide ethics education in audiology are solution-oriented, including guidelines for ethical practice (e.g. Sininger et al. Citation2003), cases about ethical decision-making (e.g. Irwin Citation2007) and regulation of professionals via formal complaints processes (e.g. CASLPO Citation2009). All of these existing resources seek to prepare individuals to understand ethical codes and principles in order to engage in ethical decision-making. These approaches are consistent with those used in other health professions; yet calls in other health professions suggest that beyond codes, guides and regulation, another form of education is useful, one that focuses on virtue (DuBois et al. Citation2013; Goldie Citation2000).

Virtue-based approaches would focus more on “what you do when no one is watching” – they relate more to identify and embodiment of professional values (Armstrong, Ketz, and Owsen Citation2003; DuBois et al. Citation2013; Grady et al. Citation2008). Approaches to teaching for virtue would not ignore ethical codes, principles and guides. Rather they would position things like codes of ethics as akin to clinical practice guidelines – a starting point but not the end point – with the actual navigation of challenging ethical situations as a form of practice-based learning. In practice, learners would need role modelling and reinforcement; therefore, teachers would need to be sensitive to ethics themselves (Wazana et al. Citation2004). Recognising something as an ethical issue is a necessary first step to ethical deliberation. In a review of physician-investigators and the medical device industry, ethical sensitivity and awareness of conflicts of interest were not always raised by education that provided content and facts (Greenwood, Coleman, and Boozang Citation2012). An ethical “lens” may require education that goes beyond provision of content knowledge in the classroom; it may require an integrated approach with workplace experiences if we wish to engender ethical sensitivity in everyday practice.

Pushing beyond the hidden curriculum of ethics towards an explicit curriculum of ethics

Potentially, a lack of careful attention to explicit ethics education in relation to industry could contribute to a prevalence of ethical uncertainty such as that seen in our study. Recall that in our findings many participants had vague sense of what might constitute an ethical tension and yet stories poured out when it was explained that an ethical tension need not be a serious ethical infraction or specific dilemma, but could include everyday uncertainties. Left to learn from the hidden curriculum, our study showed attitudes of futility and denial in our participants. Hidden curriculum entails educationally impactful cultural values, beliefs and norms of a professional field that are learned through experience and have great impact on professional identity and practice despite being unofficial parts of a curriculum (Hafferty and Castellani Citation2009; Hafferty and Franks Citation1994). The finding of a lack of sensitivity to potential ethical tensions by participants (not being able to share examples of ethical tensions) aligns with the survey results of Coolen, Caissie, and Aiken (Citation2012) wherein audiologists saw fewer scenarios about industry interactions as ethically problematic than patients did. Stories of being pressured by employers to sell more hearing aids, but feeling uncomfortable about this pressure, were sometimes dismissed as insignificant, minor and mundane. Yet despite on the one hand seeing such issues as so “normal” and not deemed ethically-important, on the other hand participants spoke of deliberate perspective-shifting or everyday workarounds to minimise potential discomfort or harm. Those who felt ethically questionable sales pressure were faced with ethical distress within their roles (they could not enact their moral position), some eventually resolving this distress by changing jobs altogether (e.g. our participant “Francine”). In this study, a small number of participants took a complete denial stance towards ethical tensions; it seems implausible that one could actually avoid any and all ethical tension in any practice. Thus it may behove audiology to look to education approaches that could raise one’s sensitivity to ethical tensions.

Education approaches for ethical clinical practice

Two sets of educational approaches show promise in raising awareness of and responsiveness to ethical tensions in health professions. The first is arts-based approach that may help develop ethical sensitivity and understanding (Kinsella et al. Citation2015; Kinsella and Bidinosti Citation2016). Because ethical sensitivity involves a more social and relational focus than some other clinical domains, arts-based approaches may be better aligned with ethics education objectives (Kinsella et al. Citation2015; Kinsella and Bidinosti Citation2016). Beyond awareness and sensitivity, education may need to look at how to prepare practitioners to resist and transform the social and political context in which they work. Here, educators could turn to critical consciousness and its associated critical pedagogy (Halman, Baker, and Ng Citation2017). Critical consciousness refers to a reflective awareness of the social world, including issues of power and politics. Its associated critical pedagogy, or the theory and approaches for educating towards critical consciousness, has been used in other sensitive domains of health care practice, such as in efforts to move learners and practitioners towards more just and culturally sensitive practice (Kumagai and Lypson Citation2009). Arguments for critical pedagogical approaches relate to critiques that teaching ethics in a procedural manner alone may create professionals who display appropriate knowledge, skills and attitudes, but who do not deeply embody the values needed to choose ethically sensitive action in the face of challenging systems of practice (DuBois et al. Citation2013; Eckles et al. Citation2005; Hafferty and Franks Citation1994; Kumagai and Lypson Citation2009). Simplistic approaches, like protocols or checklists, to complex social practices and processes may be useful starting points but, if misused, can inadvertently reproduce the very problems they aim to solve (Berg Citation1997). For example, unreflectively adhering to a guideline or checklist built for “the average” patient or problem can lead to insensitive and offensive behaviour towards an individual. For the purposes of ethical audiology–industry relations, reflective, dialogic approaches like critical consciousness and critical pedagogy may help audiologists continually reflect upon their social positions relative to patients and to systems and structures (e.g. the hearing aid industry or the research funding climate).

An important note, being able to speak up or resist systemic ethical concerns requires a sense of agency that perhaps is ambitious for any one or small group of audiologists. As this study showed, changing jobs – as opposed to advocating for change within one’s existing employment – was a common solution some of our participants applied to ethical dilemmas or ethical distress. This will not always be an option for clinicians and systemic mechanisms to support clinicians to uphold their ethical and professional values may be needed. While this discussion focussed on audiology education and on individual change, it must also mention a need for systems to play their part (Simpson et al. Citation2018).

Education approaches for ethical research practice

Finally, this discussion turns to approaches that can support faculty in ethical academic efforts. All “groups” of our participants (audiologists working in clinical practice or in industry, students and faculty) demonstrated a lack of clear ethical sensitivity and knowledge. Social science scholars have long advocated the need for reflexivity in attending to the microethics, or ethically-important moments, of practice (Guillemin and Gillam Citation2004). Microethics refers to ethical orientations to daily research practice, including the seemingly neutral words we choose to use, and actions we take in everyday work. These choices are influenced by underlying and embodied values and identities, which are socially learned and not easily developed through procedural ethics alone. Ethically-important moments are everyday ethical tensions where it may, at first glance, seem like there is a clear-cut right path to take – so much so that the tension may be missed as ethically-important altogether – and yet choosing the seemingly clear-cut right action could still feel wrong or do some harm. Procedural ethics may not pick up on subtle but important moments of practice and research in which the audiologist may be at risk for ethical uncertainty or missteps. Nor are procedural ethics dynamic enough to be applied as an ethically-important moment unfolds in real time. Guillemin and Gillam (Citation2004) argue that the research ethics checklists followed by researchers may be quite divorced from the everyday practice of research and unpredictable ethical moments that may arise in research. Instead, researchers engage in reflexivity: deliberate questioning of the assumptions and power relations underlying practices with a view to acting in the most ethical manner possible (Baker et al. Citation2016; Kinsella et al. Citation2015). An example, with the awareness of the microethics of marketing posters in clinics, audiology researchers could choose sensitive, non-directive approaches to recruiting and consenting participants and sharing research findings. The reflexive awareness that such micro factors could even matter in terms of ethics reduces the likelihood detachment from the ethical purposes of research and fosters transparency and integrity in research practices. The ethical practice of academia–industry collaborations by faculty must be a part of overall education efforts, as they are a part of the hidden curriculum, the socialising process by which audiology students learn to interact with industry (audiology researchers are also faculty who teach core content in audiology training programmes; audiology students often gain experience in research laboratories).

Conclusion

This grounded theory study fills a theoretical and empirical gap about the audiology–industry relationship and its ethical implications. Alignments with qualitative studies done in other professions including psychiatry and undergraduate medical education suggest the potential to build theoretical understanding on this topic over time, across professions (Armstrong, Ketz, and Owsen Citation2003; DuBois et al. Citation2013; Goldie Citation2000; Grady et al. Citation2008). This study’s findings together support assertions to remain cautious about overreliance on structured approaches to thinking about industrial relations, ethical practice and ethics education, and to remain optimistic about approaches to embracing nuanced approaches that recognise and dialogue about the complexities of ethical practice with industry. Based on the stories of audiologists who had changed their places of work as a result of ethical tensions – particularly ethical distress – it may be useful to conduct further research to understand the rationales and experiences of those who have left the profession altogether. In any qualitative study informed by a constructivist paradigm, generalisability is not the goal; rather the intent is to add theoretical insights on social processes, to generate relatable and transferable lessons to readers, and to inspire further inquiry on the matter. That said, further research may wish to sample differently than this study did in order to garner other insights. Based on the workplace and systems factors that shaped audiologists’ practices in this study, future research should explore the potential of practice and education theories that foster adaptive and critically reflective approaches to clinical practice and reasoning at the industry interface (Mylopoulos and Woods Citation2009; Ng et al. Citation2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr. Ryan McCreery for his input into the project, and the participants for generously sharing their time and thoughts with us.

Disclosure statement

Our research team represents the various positions of audiologists including academia, clinical practice, and industry. Author JC works for Starkey Hearing Technologies; other author affiliations can be seen in the author bylines.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 By “fit to target” we are referring to setting hearing aids according to research-based algorithms (e.g. Scollie et al. Citation2005).

References

- American Academy of Audiology. 2011. “Code of ethics: Highlighted changes effective April 2011.” http://www.audiology.org/publications-resources/document-library/code-ethics

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. 2010. “Code of ethics.” doi: 10.1044/policy.ET2010-00309

- Armstrong, M. B., J. E. Ketz, and D. Owsen. 2003. “Ethics Education in Accounting: Moving toward Ethical Motivation and Ethical Behavior.” Journal of Accounting Education 21 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1016/S0748-5751(02)00017-9.

- Baker, L., S. Phelan, R. Snelgrove, L. Varpio, J. Maggi, and S. Ng. 2016. “Recognizing and Responding to Ethically Important Moments in Qualitative Research.” Journal of Graduate Medical Education 8 (4): 607–608. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00384.

- Berg, M. 1997. “Problems and Promises of the Protocol.” Social Science and Medicine 44 (8): 1081–1088. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00235-3.

- Bushby, K., J. Chan, S. Druif, K. Ho, and E. A. Kinsella. 2015. “Ethical Tensions in Occupational Therapy Practice: A Scoping Review.” British Journal of Occupational Therapy 78 (4): 212–221. doi:10.1177/0308022614564770.

- CASLPO. 2009. “Complaints.” CASLPO Today 7 (1): 10–17.

- CBC Marketplace. 2013. “Hearing aids: Our insider’s take.” http://www.cbc.ca/marketplace/blog/hearing-aids-our-insiders-take

- Charmaz, K. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Chau, T., S. Moghimi, and M. R. Popovic. 2013. “Knowledge Translation in Rehabilitation Engineering Research and Development: A Knowledge Ecosystem Framework.” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 94 (1): 9–19. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2012.07.032.

- Consumer Reports. 2014. “Hearing aid buying guide.” http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/hearing-aids/buying-guide.htm

- Coolen, J., R. Caissie, and S. Aiken. 2012. “Ethical Dilemmas: Are Audiologists and Hearing Aid Users on the Same Side?” Canadian Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology 36 (2): 94–105.

- Crukley, J., J. A. Dundas, R. McCreery, C. N. Meston, and S. Ng. 2012. “Re-Envisioning Collaboration, Hierarchy, and Transparency in Audiology Education, Practice, and Research.” Seminars in Hearing 33 (2): 196. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1311678.

- DeChillo, S. 2012. “The Hunt for an Affordable Hearing Aid.” The New York Times. http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/10/22/the-hunt-for-an-affordable-hearing-aid/?_php=true&_type=blogs&_r=0

- Dey, I. 1999. Grounding Grounded Theory: Guidelines for Qualitative Inquiry. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- DuBois, J. M., E. M. Kraus, A. Mikulec, S. Cruz-Flores, and E. Bakanas. 2013. “A Humble Task: Restoring Virtue in an Age of Conflicted Interests.” Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges 88 (7): 924–928. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318294fd5b.

- Durocher, E., E. A. Kinsella, L. McCorquodale, and S. Phelan. 2016. “Ethical Tensions Related to Systemic Constraints.” OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health 36 (4): 216–226. doi:10.1177/1539449216665117.

- Eckles, R. E., E. M. Meslin, M. Gaffney, and P. R. Helft. 2005. “Medical Ethics Education: Where Are We? Where Should We Be Going? a Review.” Academic Medicine 80 (12): 1143–1152. doi:10.1097/00001888-200512000-00020.

- Goldie, J. 2000. “Review of Ethics Curricula in Undergraduate Medical Education.” Medical Education 34 (2): 108–119. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00607.x.

- Government of Ontario. 1991. “Regulated Health Professions Act, 1991.” Edited by Ontario. http://www.e-laws.gov.on.ca/html/statutes/english/elaws_statutes_91r18_e.htm

- Grady, C., M. Danis, K. L. Soeken, P. O’Donnell, C. Taylor, A. Farrar, and C. M. Ulrich. 2008. “Does Ethics Education Influence the Moral Action of Practicing Nurses and Social Workers.” American Journal of Bioethics 8 (4): 4–11. doi:10.1080/15265160802166017.

- Greenwood, K., C. H. Coleman, and K. M. Boozang. 2012. “Toward Evidence-Based Conflicts of Interest Training for Physician-Investigators.” The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 40 (3): 500–510. doi:10.1111/j.1748-720X.2012.00682.x.

- Guillemin, M., and L. Gillam. 2004. “Ethics, Reflexivity, and ‘Ethically Important Moments’ in Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 10 (2): 261–280. doi:10.1177/1077800403262360.

- Hafferty, F., and R. Franks. 1994. “The Hidden Curriculum, Ethics Teaching, and the Structure of Medical Education.” Academic Medicine 69 (11): 861–871. doi:10.1097/00001888-199411000-00001.

- Hafferty, F., and B. Castellani. 2009. “The Hidden Curriculum: A Theory of Medical Education.” In Handbook of the Sociology of Medical Education, edited by C. Brosnan and B. S. Turner, 15–35. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Halman, M., L. Baker, and S. Ng. 2017. “Using Critical Consciousness to Inform Health Professions Education.” Perspectives on Medical Education 6 (1): 12–20. doi:10.1007/s40037-016-0324-y.

- Hawkins, D. B., T. Hamill, and J. Kukula. 2006. “Ethical Issues in Hearing.” Audiology Today 18: 22–26.

- Holloway, K. J. 2015. “A Troubled Solution: Medical Student Struggles with Evidence and Industry Bias.” Science and Engineering Ethics 21 (6): 1673–1689. doi:10.1007/s11948-014-9623-z.

- Irwin, D. L. 2007. Ethics for Speech-Language Pathologists and Audiologists: An Illustrative Casebook. Clifton, NY: Thomson Delmar Learning.

- Jameton, A. 1985. “Nursing Practice, the Ethical Issues.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 22 (4): 343. doi:10.1016/0020-7489(85)90057-4.

- Kinsella, E. A., and S. Bidinosti. 2016. “I Now Have a Visual Image in My Mind and it is Something I Will Never Forget’: An Analysis of an Arts-Informed Approach to Health Professions Ethics Education.” Advances in Health Sciences Education 21 (2): 303–322. doi:10.1007/s10459-015-9628-7.

- Kinsella, E. A., S. Phelan, A. Park Lala, and V. Mom. 2015. “An Investigation of Students’ Perceptions of Ethical Practice: Engaging a Reflective Dialogue about Ethics Education in the Health Professions.” Advances in Health Sciences Education 20 (3): 781–801. doi:10.1007/s10459-014-9566-9.

- Kinsella, E. A., A. Bossers, and D. Ferreira. 2008. “Enablers and Challenges to International Practice Education: A Case Study.” Learning in Health and Social Care 7 (2): 79–92. doi:10.1111/j.1473-6861.2008.00178.x. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1473-6861.2008.00178.x/full.

- Kumagai, A. K., and M. L. Lypson. 2009. “Beyond Cultural Competence: Critical Consciousness, Social Justice, and Multicultural Education.” Academic Medicine 84 (6): 782–787. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a42398.

- Meston, C. N., and S. Ng. 2012. “A Grounded Theory Primer for Audiology.” Seminars in Hearing 33 (2): 135–146. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1311674.

- Moodie, S., A. Johnson, and S. Scollie. 2008. “Evidence-Based Practice and Canadian Audiology.” Canadian Hearing Report 3 (1): 12–14.

- Mylopoulos, M., and N. N. Woods. 2009. “Having Our Cake and Eating it Too: Seeking the Best of Both Worlds in Expertise Research.” Medical Education 43 (5): 406–413. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03307.x.

- Naude, A. M., and J. Bornman. 2014. “A Systematic Review of Ethics Knowledge in Audiology (1980–2010).” American Journal of Audiology 23: 151–158. doi:10.1044/2014_AJA-13-0057.

- Ng, S., L. Lingard, and T. J. Kennedy. 2013. “Qualitative Research in Medical Education: Methodologies and Methods.” In Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory and Practice. 2nd ed. edited by T. Swanwick, 371–384. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Ng, S., D. J. Bartlett, and S. D. Lucy. 2010. “Introducing the Comprehensive Professional Behaviours Development Log–Audiology (CPBDL-A): Rationale, Development and Applications.” Canadian Hearing Report 5 (4): 35–43.

- Ng, S., D. J. Bartlett, and S. D. Lucy. 2012. “Reflection as a Tool for Audiology Student and Novice Practitioner Learning, Development, and Self-Care.” Seminars in Hearing 33 (2): 163–176. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1311676.

- Ng, S., D. J. Bartlett, and S. D. Lucy. 2013. “Exploring the Utility of Measures of Critical Thinking Dispositions and Professional Behavior Development in an Audiology Education Program.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 24 (5): 354–364. doi:10.3766/jaaa.24.5.3.

- Ng, S., E. A. Kinsella, F. Friesen, and B. Hodges. 2015. “Reclaiming a Theoretical Orientation to Reflection in Medical Education Research: A Critical Narrative Review.” Medical Education 49 (5): 461–475. doi:10.1111/medu.12680.

- Ng, S., L. Lingard, K. Hibbert, S. Regan, S. Phelan, R. Stooke, C. N. Meston, C. Schryer, M. Manamperi, and F. Friesen. 2015. “Supporting Children with Disabilities at School: Implications for the Advocate Role in Professional Practice and Education.” Disability and Rehabilitation 37: 2282–2290. doi:10.3109/09638288.2015.1021021.

- Opacich, K. J. 1997. “Moral Tension and Obligations of Occupational Therapy Practitioners Providing Home Care.” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 51 (6): 430–435. doi:10.5014/ajot.51.6.430.

- Pauly, B. M., C. Varcoe, and J. Storch. 2012. “Framing the Issues: Moral Distress in Health Care.” HEC Forum : An Interdisciplinary Journal on Hospitals’ Ethical and Legal Issues 24 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1007/s10730-012-9176-y.

- Phelan, S., E. A. Kinsella. 2013. “Picture This … Safety, Dignity, and Voice–Ethical Research with Children: Practical Considerations for the Reflexive Researcher.” Qualitative Inquiry 19 (2): 81–90. doi:10.1177/1077800412462987.

- Phelan, S., V. Wright, and B. E. Gibson. 2014. “Representations of Disability and Normality in Rehabilitation Technology Promotional Materials.” Disability and Rehabilitation 36: 2072–2079. doi:10.3109/09638288.2014.891055.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. 2008. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software, Version 8. Melbourne, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd.

- Tyler, R. S., A. J. Parkinson, B. S. Wilson, S. Witt, J. P. Preece, and W. Noble. 2002. “Patients Utilizing a Hearing Aid and a Cochlear Implant: Speech Perception and Localization.” Ear and Hearing 23 (2): 98–105. doi:10.1097/00003446-200204000-00003. http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-0036209033&partnerID=40&md5=9ca26369175f005f07baa93031403d99.

- Scollie, S., R. Seewald, L. Cornelisse, S. Moodie, M. Bagatto, D. Laurnagaray, S. Beaulac, and J. Pumford. 2005. “The Desired Sensation Level Multistage Input/Output Algorithm.” Trends in Amplification 9 (4): 159–197. doi:10.1177/108471380500900403.

- Simpson, A., K. Phillips, D. Wong, S. Clarke, and M. Thornton. 2018. “Factors Influencing Audiologists’ Perception of Moral Climate in the Workplace.” International Journal of Audiology 57 (5): 385–394. doi:10.1080/14992027.2018.1426892.

- Sininger, Y., R. Marsh, B. Walden, and L. A. Wilber. 2003. “Guidelines for Ethical Practice in Research for Audiologists.” Audiology Today 15 (6): 14–17.

- Stark, T. J., A. K. Brownell, N. P. Brager, A. Berg, R. Balderston, and J. M. Lockyer. 2016. “Exploring Perceptions of Early-Career Psychiatrists about Their Relationships with the Pharmaceutical Industry.” Academic Psychiatry 40 (2): 249–254. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0403-0.

- Storch, J., and P. Rodney. 2009. Leadership for Ethical Policy and Practice. Canadian Health Services Research Foundation. Ottawa, Canada.

- Wazana, A., A. Granich, F. Primeau, N. H. Bhanji, and M. Jalbert. 2004. “Using the Literature in Developing McGill’s Guidelines for Interactions between Residents and the Pharmaceutical Industry.” Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges 79 (11): 1033–1040. doi:10.1097/00001888-200411000-00004.

- Windmill, I. A., D. R. Cunningham, and J. E. Preminger. 2004. “The University of Louisville: The.” American Journal of Audiology 13 (2): 110–117. doi:10.1044/1059-0889(2004/015).

- Windmill, I. A., B. A. Freeman, J. Jerger, and J. M. Scott. 2010. “Guiding Principles for the Interaction between Academic Programs in Audiology and Industry.” Audiology Today, 22 (2): 47–57.

- Windmill, I. A., and B. A. Freeman. 2013. “Demand for Audiology Services: 30-Yr Projections and Impact on Academic Programs.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 24 (5): 407–416. doi:10.3766/jaaa.24.5.7.