Abstract

Objective: To develop an intervention for the implementation of an ICF-based e-intake tool in clinical oto-audiology practice.

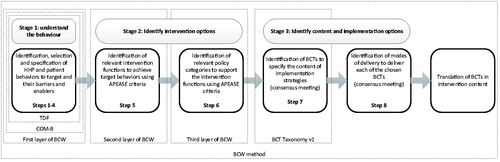

Design: Intervention design study using the eight-stepped Behaviour Change Wheel. Hearing health professionals’ (HHPs) and patients’ barriers to and enablers of the use of the tool were identified in our previous study (steps 1–4). Following these steps, relevant intervention functions and policy categories were selected to address the reported barriers and enablers (steps 5–6); and behaviour change techniques and delivery modes were chosen for the selected intervention functions (steps 7–8).

Results: For HHPs, the intervention functions education, training, enablement, modelling, persuasion and environmental restructuring were selected (step 5). Guidelines, service provision, and changes in the environment were identified as appropriate policy categories (step 6). These were linked to nine behaviour change techniques (e.g. information on health consequences), delivered through educational/training materials and workshops, and environmental factors (steps 7–8). For patients, the intervention functions education and enablement were selected, supported through service provision (steps 5–6). These were linked to three behaviour change techniques (e.g. environmental factors), delivered through their incorporation into the tool (steps 7–8).

Conclusions: A multifaceted intervention was proposed to support the successful implementation of the intake tool.

Introduction

Over the last years, a paradigm shift has been observed towards providing more patient-centred care by treating the patient from a biopsychosocial perspective rather than from a biomedical perspective (i.e. just treating the patient’s disorder or disease). The need for such a biopsychosocial approach has also been recognised in ear and hearing health care, as has the need for a standardised reference system to facilitate this (Kricos Citation2000, Boothroyd Citation2007, Danermark et al. Citation2010, Blazer, Domnitz, and Liverman Citation2016). The World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) provides such a reference system or model (WHO Citation2001). The classification system can be used to describe health conditions in all their complexity in a standardised way. According to the ICF, functioning reflects the interplay between an individual’s body structures and functions, activities, participation, and the contextual factors around this individual. To facilitate the application of the ICF in ear and hearing health care, the Comprehensive and Brief ICF Core Sets for Hearing Loss (CSHL) were developed (Danermark et al. Citation2010). These represent shortlists of ICF categories that cover the most relevant areas of functioning of adults with hearing loss for use in clinical encounters and research (Danermark et al. Citation2010).

Capturing functioning information is particularly important during the early stages of assessment and diagnosis. This way, the design of a personalised treatment plan can be facilitated (Meyer et al. Citation2016, Vas, Akeroyd, and Hall Citation2017). The Brief CSHL provides a minimal standard for organising and documenting hearing-related functioning information and can be taken as a starting point for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and other services (Danermark et al. Citation2013, van Leeuwen et al. Citation2017, van Leeuwen et al. Citation2018). However, the CSHL do define “what to assess”, but do not indicate “how to assess”. Therefore, to allow application of the Brief CSHL in intake practice, operationalisation of the ICF categories into a practicable form is required first, followed by the design of an intervention to actually implement the CSHL.

Patients’ self-report is recommended as the most appropriate measure for capturing functioning information (FDA Citation2009, Macefield et al. Citation2014). We have developed an intake tool through operationalising the categories of the Brief CSHL into a digital Patient Reported Outcome Measure (PROM), which we have named the “ICF-based e-intake tool”. The development process comprised a mixed methodology study including qualitative content assessments, in which all stakeholders’ views (i.e. patient representatives, hearing health professionals, researchers; van Leeuwen et al., under review) were incorporated. The goal of the intake tool is to screen adults with ear and/or hearing problems in order to be able to identify potential functioning problems and relevant influencing contextual factors. With such information, patients’ care plans can be tailored to their specific problems and needs. The intended use is that adult patients complete the questionnaire part of the intake tool prior to their intake, after which the responses become available for both the patient and the health care professional. By making the intake tool an integral part of clinical care, we aim to facilitate communication between health care professionals and patients and shared treatment planning (Greenhalgh et al. Citation2018). It is envisaged that use of the tool would optimise the individual patient’s care and treatment outcomes. Nevertheless, it is known that the actual integration and use of PROMs in clinical practice (i.e. implementation into routine care) often is challenging and suboptimal (Boyce Browne, and Greenhalgh Citation2014, Kyte et al. Citation2015, Swinkels et al. Citation2015, Hanbury Citation2017).

Implementing a new tool into clinical practice involves changes in established practices. Specifically, human behaviour change is an essential element of implementation processes (Michie, van Stralen, and West Citation2011). For example, the potential effect of the use of PROMs on health outcomes is crucially mediated by the modification of the behaviour of both patients and health care professionals (Greenhalgh, Long, and Flynn Citation2005, Valderas, Alonso, and Guyatt Citation2008). The field of implementation science and theories of behaviour change can inform the implementation of PROMs and can ensure that potential challenges are anticipated and can be addressed (Noonan et al. Citation2017). In order for the implementation of any (intake) tool to become successful, a carefully developed theory-based (behaviour change) intervention is needed (Greenhalgh, Long, and Flynn Citation2005, Noonan et al. Citation2017). Despite this knowledge, prior studies on the implementation of PROMs often lacked a careful assessment of barriers to and enablers of change and had insufficient methodological rigour (Boyce Browne, and Greenhalgh Citation2014, Noonan et al. Citation2017).

As recommended by the Medical Research Council, behaviour change interventions should be evidence-based and draw on relevant and coherent theoretical frameworks (Campbell et al. Citation2000, Craig et al. Citation2008). The Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) is such a framework, and is recommended when undertaking theoretically-informed research in the context of hearing health care (Coulson et al. Citation2016). The process of intervention development using the BCW is outlined in detail (Michie, van Stralen, and West Citation2011), and has been applied successfully in different contexts (e.g. implementing international sexual counselling guidelines in clinical cardiac rehabilitation, Mc Sharry, Murphy, and Byrne Citation2016); improving screening for people with mental illness, Mangurian et al. Citation2017). In audiology research, Barker and colleagues (Barker, Atkins, and de Lusignan Citation2016, Barker, Lusignan, and Deborah Citation2018) successfully used the BCW to develop an intervention to improve hearing-aid use in adult auditory rehabilitation.

Behaviour Change Wheel

The BCW synthesises 19 theoretical frameworks of behaviour change and is based on a model of human behaviour, the COM-B model (Michie, van Stralen, and West Citation2011). The COM-B model presents human behaviour (B) as resulting from the interaction between physical and psychological capabilities (C), opportunities provided by the physical and social environment (O), and reflective and automatic motivation (M) (Michie, van Stralen, and West Citation2011). The COM-B model is surrounded by nine general intervention functions, and seven policy categories that can support the delivery of the intervention functions (see ). The BCW is used to link influences on behaviour, identified by the COM-B, to potential intervention functions and policy categories.

Figure 1. The Behaviour Change Wheel. Reprinted from The Behaviour Change Wheel: a guide to designing interventions. By Michie, S., Atkins, L., and West, R. (2014). London: Silverback Publishing. Copyright [2014] by Michie, S, Atkins L., and West, R. Reprinted with permission.

![Figure 1. The Behaviour Change Wheel. Reprinted from The Behaviour Change Wheel: a guide to designing interventions. By Michie, S., Atkins, L., and West, R. (2014). London: Silverback Publishing. Copyright [2014] by Michie, S, Atkins L., and West, R. Reprinted with permission.](/cms/asset/916a0e54-43b5-47ec-991c-0caf42c09992/iija_a_1691746_f0001_c.jpg)

In addition to the framework, the BCW provides a systematic eight-stepped process for designing behaviour change interventions. This process covers 3 main stages: 1) understand the behaviour (steps 1–4), 2) identify intervention options (steps 5–6), and 3) identify content and implementation options of the intervention (steps 7-8; Michie, Atkins, and West Citation2014). In a previous study, we performed the first stage of the BCW method, which is briefly described below.

Previous study (stage 1)

Steps 1 to 3 covered the identification, selection and specification of the behaviour(s) to target, respectively. The target behaviour was defined as: “use of the intake tool by patients and hearing health professionals (HHPs)”. Our specification of the target behaviours is provided in .

Table 1. Specification of the selected target behaviours.

Step 4 covered the identification of what needs to change in order to achieve the target behaviour and the specific enablers of and barriers to that behaviour. We used the COM-B model and Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to identify and categorise barriers to and enablers of the use of the intake tool. The TDF specifies the C, O, and M components as theoretical domains of behaviour related to implementation (Atkins et al. Citation2017). These include for example knowledge, skills, beliefs about own capabilities, and emotion (Cane, O'Connor, and Michie Citation2012). Focus groups and interviews with HHPs (N = 20) and patients (N = 18) were performed. The characteristics of the study population, procedures and results are described in detail in a separate publication (See van Leeuwen et al. Citation2018). Two important HHP barriers that were identified included expected lack of time to use the tool (O); and fear of being held responsible for addressing any emerging problems that would be outside the expertise of the HHP (M). Important enablers that were identified included: the integration of the intake tool in the electronic patient record (O); the opportunity for the patient to be better prepared for the intake visit (M); and provision of a complete picture of the patient’s functioning via the intake tool (M). Identified patients’ barriers included fear of losing personal contact with the HHP (M); and fear that use of the intake tool might negatively affect conversations with the HHP (M). Identified enablers included sufficient knowledge on the aim and relevance of the intake tool (C); better self-preparation for the intake (M); and a more focussed intake procedure (M). In both HHPs and patients, various factors relating to the design of the intake tool were reported to enable its use (O).

Aim of current study

The aim of the current study was to develop an intervention for the implementation of the ICF-based e-intake tool in clinical oto-audiology practice. Based on the results of stage 1 (van Leeuwen et al. Citation2018, see introduction), the current study focussed on stages 2 and 3 of the BCW method.

Materials and methods

shows the eight-stepped process of the BCW method for intervention development. The steps of stages 2 and 3, which were the focus of the current study, are explained below.

Figure 2. The stages and specific steps of the BCW method, related to the layers of the BCW. APEASE criteria: optimal affordability, practicability, effectiveness, acceptability, side effects and equity. TDF: Theoretical Domains Framework; COM-B: capability, opportunity, motivation-behaviour model; BCW: behaviour change wheel.

Stage 2: Identify intervention options (steps 5-6)

Step 5 concerns the identification of intervention functions, that is, the general categories through which behaviour may change (i.e. from not using an intake tool into using an intake tool). Step 6 concerns the identification of policy categories to support the delivery of the intervention functions (Michie, Atkins, and West Citation2014). These steps are described in more detail below.

Step 5: Identification of intervention functions

Based on the results of the study addressing Stage 1 covering the barriers and enablers reported by the HHPs and patients (van Leeuwen et al. Citation2018), LvL started creating a list of possible intervention functions that would address each of them (step 5). Intervention functions were also selected from published decision grids in the BCW guide. These grids provide evidence and theory-based guidance on which intervention function might be used to address particular COM-B components and TDF domains (Michie, Atkins, and West Citation2014). In addition, the criteria “affordability”, “practicability”, “effectiveness/cost-effectiveness”, “acceptability”, “side effects/safety” and “equity” (i.e. APEASE criteria) were included. In this step, supporting evidence found in the literature on intervention functions was used to select the most context-appropriate intervention function(s) for each barrier and enabler (Michie, Atkins, and West Citation2014). Ideally, intervention function(s) are chosen which are optimal on all these criteria.

Step 6: Identification of policy categories

Policy categories were identified by linking them to the intervention functions chosen in step 5. The identification of appropriate policy categories was based on the BCW decision grid that specifies which policy categories may support the delivery of the selected intervention functions. Then, again the APEASE criteria and available evidence in the literature on potential successful policies were used in the selection process.

LvL created the preliminary list of intervention functions (step 5) and policy categories (step 6) and presented these to a team of six experts. Each member of the team had ample experience on one or more areas of relevance: clinical ear and hearing practice, evidence-based implementation, or the ICF. Further expert characteristics are provided in . The lists were discussed during the expert group discussion and it was agreed which of the intervention functions and policy categories would be most applicable to the oto-audiology setting. Discussions were held until consensus on all intervention functions and policy categories was reached. The definitions of the available intervention functions and policy categories are presented in Supplemental Materials 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 2. Characteristics of the expert group.

Stage 3: Identify content and implementation options (steps 7–8)

Stage 3 aims to specify intervention content in terms of behaviour change techniques (BCT) (step 7) and to identify the mode of delivery for the intervention (step 8). Stage 3 took place in the consensus meeting with the expert team.

Step 7: Identification of BCTs

The purpose of this step was to link BCTs to the selected intervention functions (step 5). BCTs are the smallest, active components of an implementation intervention to change behaviour (Michie, Atkins, and West Citation2014). A taxonomy of 93 techniques has been developed (BCTTv1; Michie et al. Citation2013). From this taxonomy, the BCW method identifies the most frequently used BCTs for each intervention function (Michie, Atkins, and West Citation2014). The definitions of these are provided in Supplemental Material 4. This list was used as a reference in the current study to identify the BCTs that could specify the content of the selected intervention functions. The APEASE criteria, literature on the BCTs, and experience from the expert team members informed the selection of the BCTs considered most appropriate to support successful implementation of the tool.

Step 8: Identification of delivery mode

In step 8, the most optimal modes to deliver each of the chosen techniques (step 7) were identified (i.e. face-to-face, over distance), given careful consideration to the context in which the intake tool will be implemented. In this step, the clinical experience of the audiologist and ENT surgeon members of the expert team was particularly useful for applying the APEASE criteria to select specific modes of delivery.

Intervention content

Lastly, the BCTs were translated into intervention content during the final part of the group discussion. To optimise the completeness of the reporting of the intervention, the template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist was used (Hoffmann et al. Citation2014). The checklist contains 10 items for describing an intervention protocol: the name of the intervention (item 1), the rationale (item 2), materials and procedures (items 3–4), intervention provider characteristics (item 5), modes of delivery (item 6), location (item 7), frequency of the intervention delivery (item 8), tailoring (item 9), and fidelity of the implementation intervention (item 11).

Ethics

The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Amsterdam UMC, location VU University Medical Centre (VUmc), Amsterdam; the Netherlands. Data collection was carried out between November 2016 and February 2017.

Results

and show the results of the entire BCW process for HHPs and patients, respectively. All identified enablers and barriers for HHPs are presented in column 3 of . The identified enablers and barriers for patients are presented in column 2 of . The tables also show the capability, opportunity, and motivational-components (column 1), and TDF-domains (column 4 for HHPs and column 3 for patients) that the barriers and enablers were linked to. The results of stages 2 and 3 are explained below.

Table 3. Intervention content targeting HHPs’ barriers (A) and enablers (B) towards using the intake tool.

Table 4. Intervention content targeting patients’ barriers (A) and enablers (B) towards using the intake tool.

The key supporting articles that were used to inform the selection of intervention functions, policy categories, and BCTs, are provided in Supplemental Material 1.

Stage 2

Step 5: Intervention functions

Education, persuasion, training, environmental restructuring, enablement and modelling were identified as the most appropriate intervention functions for HHPs (see , column 5). The use of the APEASE criteria to select the most relevant intervention functions is shown in Supplemental Material 2. Education, such as information about the content of the intake tool and how to use it, persuasion (such as persuasive communication) and training (such as role play) were selected for overcoming the HHPs’ perceived barriers relating to the negative consequences of the intake tool, their own professional identity and their self-efficacy. Modelling was selected as an option to demonstrate how to use the intake tool. Enablement was selected to, for example, help HHPs to interpret the results of the intake tool. In addition, environmental restructuring was selected to incorporate specific design features and functionalities in the intake tool that adhere to the HHPs’ preferences (e.g. integration into electronic patient record and provision of summaries of the results). This with the aim to make the data of the intake tool easily accessible and actionable.

For patients, education, persuasion, enablement and factors relating to environmental restructuring were selected as the most appropriate intervention functions (see , column 4). Education was selected to facilitate knowledge about the purpose and relevance of the intake tool and to provide instructions on how to fill out the intake tool. Persuasive communication techniques were selected for reinforcing patients’ motivational beliefs about the positive consequences of using the intake tool. Enablement and environmental restructuring were selected to enable the preferred administration of the intake tool, and to adapt the design and functionalities of the intake tool to the patients’ preferences (e.g. ensure easy accessibility to the digital questionnaire).

Step 6: Policy categories

The use of the APEASE criteria to select the most relevant policy categories is shown in Supplemental Material 3. For HHPs, three policy categories were selected: guidelines, environmental/social planning and service provision (see , column 6). “Guidelines” were selected as a means to provide HHPs with educational and instructional intervention functions. The categories “service provision” and “environmental planning” were selected as the most appropriate for training and modelling skills that would enable the practical use of the intake tool.

For patients, only the category service provision was considered an appropriate policy category (see , column 5). This is because the use of the intake tool can be considered as provision of a service. It was envisaged that all identified intervention functions for patients would be incorporated into the intake tool itself and thus are presented to the patient when the intake tool is provided to them.

Stage 3

Step 7: Behaviour change techniques

The BCTs per selected intervention function (step 5), the use of the APEASE criteria, and consensus to select the most appropriate BCTs are shown in Supplemental Material 4. The linking of the selected BCTs to the reported barriers and enablers and intervention functions is shown in column 7 of (HHPs) and column 6 of (patients). To illustrate, the BCTs that were mapped to the barriers in the knowledge and skills domain of HHPs included the provision of information on health consequences (e.g. provide information on the relevance of the patient’s view and the ICF), modelling/demonstration of behaviour and behavioural rehearsal of relevant skills (e.g. how to use the intake tool).

For patients, all barriers and enablers relating to skills, knowledge, and motivational beliefs were addressed by the BCT information provision (e.g. inform the patient on the relevance and purpose of the intake tool; emphasise that the intake tool could help facilitate a more targeted intake process). Barriers and enablers identified in the environmental context were linked to the BCT adding objects to the physical environment (e.g. providing a digital questionnaire to be filled in at home).

Step 8: Modes of delivery

For HHPs, the following modes of delivery for the BCTs were selected: face-to-face group workshops given by an opinion leader, a digital/printed manual, design features and supporting instruments incorporated in the intake tool. HHPs’ schedules are usually already quite full, including consultations with patients, administrative tasks, and team meetings to discuss patient cases, and department policy and regulations. In recognition of the limited time that audiologists and ENT surgeons have, and based on the experience of the ENT surgeon and audiologist expert team members, offering a kick-off workshop that could be fit in their schedules once was considered best.

For patients, it was decided to provide all BCTs through service delivery via the intake tool. Important aspects include clear information provision on the intake tool’s purpose, and instructions on how to use the tool (inserted in written format in the introductory text sent along with the intake tool itself). Provision of a customer service phone-number in case of technical or other problems was also selected.

Intervention content

The chosen BCTs were translated into concrete intervention content which is listed in the last columns of and . gives an overview of the different intervention components and their content targeted at HHPs. gives this overview for the patients. The completed TIDieR checklist is shown in Supplemental Material 5.

Table 5. Intervention content targeted at HHPs.

Table 6. Intervention content targeted at patients.

Discussion

This paper describes the development of an intervention to facilitate the successful implementation of an ICF-based e-intake tool in clinical oto-audiology practice. Intervention content was identified using the BCW method and was based on HHP’s and patient’s earlier identified barriers to and enablers of using the intake tool in clinical practice (van Leeuwen et al. Citation2018). The current study stepwise identified different intervention functions, policy categories, and BCTs, that are considered appropriate and adequate to tackle the barriers to and promote enablers of using the intake tool in the oto-audiology practice.

The proposed intervention was built on the experience of a diverse group of researchers and health care professionals. Below, the intervention is further explained and related to the existing literature that was used to motivate the choices made in the BCW process, followed by a discussion of the project’s strengths and limitations, implications for research and practice, and possible future directions.

Intervention content targeted at HHPs

Educational material and training

Educational interventions promote ownership and correct use of PROMs by HHPs (Antunes et al. Citation2014, Horppu et al. Citation2018). Several studies indicate that the best way to impact change is by demonstrating the value of a PROM to potential users (i.e. health care professionals) (Hatfield and Ogles Citation2004, Snyder et al. Citation2012, Locklear et al. Citation2014, Santana et al. Citation2015). Based on these studies and on our own results, we therefore suggest that the organisation of a workshop in which the use of the intake tool is demonstrated would be an appropriate intervention. In this workshop, case studies could be used to demonstrate the mapping of patient information collected through the intake tool. It is expected that discussions among the attendants (HHPs) could help them to understand how this information could aid their clinical reasoning, and enable them to analyse and change their attitudes (Appleby and Tempest Citation2006, Haverman et al. Citation2014). Specifically, the use of role play to learn skills needed to use the intake tool in practice could be helpful, as this has shown to be an effective way to use and discuss PROM scores with patients (Haverman et al. Citation2014, Santana et al. Citation2015). Moreover, a group workshop may increase the chances of creating a “social norm” (Michie, van Stralen, and West Citation2011). Social reinforcement by colleagues may act as mediator, e.g. by assisting one another, to reach (sustained) behaviour change. Moreover, professional group’s perceptions of their professional boundaries may effectively be socialised through education and training (Nancarrow and Borthwick Citation2005, Greenhalgh et al. Citation2018). In previous studies in other health care fields, it was shown that the provision of audit and feedback could positively influenced users’ beliefs and attitudes towards the use of the PROM, and as such add to the effective implementation of PROMs in clinical practice (Ivers et al. Citation2012, Antunes et al. Citation2014, Santana et al. Citation2015, Colquhoun et al. Citation2017).

In the expert team’s discussion about the delivery mode of the workshop, it was emphasised that the workshop would need to be brief and fit into the existing clinical schedules of the HHPs. Haverman et al. (Citation2014) found that adequate time-management determined the chances of HHPs actually attending the workshop, and thereby the successfulness of the implementation.

Local opinion leaders

To address HHPs’ scepticism and other negative attitudes to the intake tool, we proposed that opinion leaders in the HHPs own discipline (audiology and ENT) could give the workshop and promote the intake tool. Opinion leaders are people who are seen as credible, likable and trustworthy (Flodgren et al. Citation2011). Senior audiology or otology staff members could serve as such opinion leaders. Because of their influence, it is thought that they may be able to help and persuade their colleagues to use the intake tool. The effectiveness of using opinion leaders is supported by a high-quality review (Flodgren et al. Citation2011), which revealed that including opinion leaders to be part of an intervention is comparable to the distribution of educational materials, audit and feedback, and multifaceted interventions involving educational outreach in increasing compliance. Moreover, persistence and regular encouragement by an opinion leader have been shown to be necessary to ensure that the implementation becomes successful (Antunes et al. Citation2014).

Environmental factors

HHPs identified the limited time per patient as an important barrier to using the intake tool in clinical practice. Whilst this barrier may not be easily changeable, a number of other intervention options may be used to overcome this barrier. One is the provision of sufficient support and opportunities to use the intake tool. A key strategy which was reported is the use of an ePROM, which is preferably integrated in the existing electronic medical record (EMR) system. Patients’ results would then immediately be added to a patient’s record, ready for the HHP to review. To facilitate this, a comprehensive IT infrastructure would be needed, including: (1) technical devices for data collection and output, (2) appropriate software solutions and network facilities for data transmission, storage, and back-up, (3) technical support, and (4) updates (Wintner et al. Citation2016). In addition, issues of data security and patient confidentiality should be secured. These organisational-related issues would need to be addressed during the actual implementation process.

Other important intervention options to limit HHPs’ burden included easing the process of reviewing and interpreting the patient’s scores. It is proposed to do this by applying a system using alerting flags to highlight identified problems in functioning, an easy to read (graphical) summary format, and providing HHPs with concrete actions they could take as a follow-up. These strategies would require the definition of relevant cut-off scores, and the provision of a referral decision tree that can guide HHPs with their actions. These efforts would need to be considered during the next steps of the development process of the intake tool.

As already addressed in our previous study, audiologists generally had a more positive attitude towards implementing the intake tool as compared to the ENT surgeons (van Leeuwen et al. Citation2018). Audiologists generally seemed more willing to change their practice in order to use the intake tool. This suggests that a “lighter version” of the workshop, including less verbal persuasion about the potential benefit of the tool, may be considered appropriate for the audiologists.

Intervention content targeted at patients

Education and instructions

It is proposed that patients should be provided with information on the purpose of, relevance of, and privacy issues regarding the intake tool. Other studies have indicated that this is an important approach (e.g. Wintner et al. Citation2016). Educational and instructional material in an information letter could be sent along with the invitation for the appointment at the outpatient clinic. This letter would contain information about the purpose and expected patient-benefits of the intake tool, the online questionnaire and a direct link to the questionnaire. The extensiveness of information and instructions provided should be balanced with the length of the questionnaire however, as a long questionnaire was reported as a barrier to use the intake tool.

Environmental factors

Most of the practical intervention components that we formulated are consistent with documented recommendations to limit patient burden (Greenhalgh Citation2009, Locklear Citation2014, Aaronson et al. Citation2015). These include: reaching patients where it is convenient for them (at their own private area; i.e. at home) without any time constraints; providing a simple accessibility and user interface in case of administering the e-intake tool (easy log in and navigation); and restricting the number of questions (maximum of 15 minutes completion time). In our previous study (van Leeuwen et al. Citation2018), most patients reported to prefer an ePROM, but availability of a paper-pencil version could serve as back-up for those patients who would otherwise decline assessment (e.g. older people without computer experience).

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study is that we used a systematic, theory-driven and evidence-based method to develop an intervention to facilitate the implementation and use of the intake tool into clinical oto-audiology practice. Other strengths are the inclusion of both the patients’ and the HHPs’ perspectives and the incorporation of barriers and enablers for the selection of intervention options and content. Studies have shown that early engagement of stakeholders may reduce barriers and ensure commitment to implementation (Haverman Citation2014, Connell et al. Citation2015, Kwan et al. Citation2016). This also holds for patient involvement (Aaronson Citation2015). Moreover, it is known that more useful results are obtained if research teams develop and evaluate an intervention for implementation simultaneously at multiple levels (e.g. patient, provider, care team workflow, medical record system) rather than treat them as separate interventions (Emmons et al. Citation2012, Stover and Basch Citation2016). Lastly, the BCW method resulted in a multifaceted intervention, the latter of which has been shown more effective than single interventions (Boaz et al. Citation2015).

The current study also has some limitations that deserve discussion. One limitation is the current lack of exemplary studies using the BCW method in audiology to draw on. Moreover, literature on effective interventions for the implementation of PROMs and ICF-based instruments into clinical practice is scarce too. The consensus reached in the expert team was driven by expert-based knowledge of a few experts only. Another consideration is that this study did not explicitly focus on the wider organisational, i.e. hospital level or socio-political level. Whereas we did take into account the practical organisation of collecting data in patient records (which requires technology support as part of the hospital’s structure and policy; Haverman Citation2014), we did not focus on other potentially important factors on the socio-political level, such as reimbursement.

Implications for research and practice

Up to now, only a small number of studies utilised theoretical models or frameworks to understand and act upon the factors influencing patients’ or health care professionals’ behaviour in using PROMs (e.g. Haverman Citation2014). We identified only one study that used a model for implementing the ICF, in which Appleby and Tempest (Citation2006) used change management theory to implement the ICF framework in occupational therapy service delivery. They identified similar intervention components to be successful: using opinion leaders (process helpers and solution givers) to lead the developments, and the adoption of an interactive facilitation style (group activities). To our knowledge, our study is the first to provide an example on how to apply the BCW method to develop an intervention for a new tool in clinical oto-audiology practice. Although the importance of behaviour change interventions for implementing evidence-based practice is increasingly recognised (Moodie et al. Citation2011, Boisvert et al. Citation2017), the use of a systematic approach as described in this paper has been published only by one other research group (Barker, Atkins, and de Lusignan Citation2016, Barker, Lusignan, and Deborah Citation2018). Our use of a systematic approach and description of intervention content using standard terminology contribute to the science of implementation intervention development within audiology, but possible also in other fields.

It should be noted that implementation studies like the current one are largely built on the experience of a diverse group of health care professionals and researchers making decisions starting from their own areas of expertise. Although the BCW provides a step-by-step process and we used expertise of experienced health care professionals and researchers, subjectivity is a feature of the method in every stage. The intervention was designed specific to the cultural and professional context in which the HHPs included in our study are working. Therefore, the intervention may not be considered generalisable in the classic scientific meaning of the word. Nonetheless, our intention was to describe the considerations and choices made to come to the intervention as well as possible, and as such help researchers, health care professionals, and service managers in other contexts decide what of our work they can transfer to their own contexts.

The applicability of the intake tool in its current form, and in our context still has to be proven in practice, which we plan to address in a field-test study. Based on the results, possible adjustments will be made before final implementation. In addition, commitment of HHPs to use the intake tool in practice is expected to rise with proof of relevance and effectiveness.

This study focussed on short-term objectives for implementation and introducing the intake tool in clinical practice. Longer term-objectives, i.e. optimising its use in clinical practice, will likely be successful only if ongoing training and interactive sessions with HHPs are provided to cement the changes. This also would include facilitating reflections on their progress and feedback to promote further learning and development (Appleby and Tempest Citation2006).

Future research

The actual translation of the proposed intervention into content in the manual, workshop, and design and functionalities of the intake tool itself is currently ongoing and involves further engagement and collaboration with relevant stakeholders (e.g. feedback of patients and HHPs, and organisational support). This also includes the field-test study, which must be carried out before actual implementation. Then, after implementation, the effectiveness of the intervention will need to be determined in future research.

Conclusion

A multifaceted intervention was proposed to facilitate the implementation of an ICF-based e-intake tool by HHPs and patients in clinical oto-audiology practice. For HHPs, provision of educational/training materials and workshops delivered by opinion leaders are recommended, to enhance HHPs’ knowledge, awareness, skills, and self-efficacy. In addition, adjustments in the environment and design of the intake tool are needed to facilitate practical use. For patients, various design features need to be adopted to facilitate adequate use. Also a concise information letter sent along with the intake tool is recommended, to clarify the goals and relevance, and to address concerns regarding the intake tool’s impact on the relationship with the HHP. The first steps towards the implementation of the intake tool have been taken, and now need to be further worked out to an integrated implementation plan. In addition, the intake tool should be further developed such that it would fit HHPs’ and patients’ preferences (including the definition of cut-offs, referral, and treatment decision trees).

Author contributions

The work presented in this manuscript was a collaboration between all authors. LvL, MP and SK analysed the data. All authors participated in the interpretation of the data. LvL had the leading role in the writing process. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the current version to be submitted to the International Journal of Audiology.

TIJA-2018-07-0215-File010.docx

Download MS Word (36.6 KB)TIJA-2018-07-0215-File009.docx

Download MS Word (35.7 KB)TIJA-2018-07-0215-File008.docx

Download MS Word (28.1 KB)TIJA-2018-07-0215-File007.docx

Download MS Word (30.7 KB)TIJA-2018-07-0215-File006.docx

Download MS Word (24.6 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aaronson, N., A. Choucair, T. Elliott, J. Greenhalgh, M. Halyard, et al. 2015. “Isoqol.” User’s Guide to Implementing Patient-Reported Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice, version: January 2015. Accessed 9 July 2018. http://www.isoqol.org/UserFiles/2015UsersGuide-Version2.pdf.

- Antunes, B., R. Harding, and I. J. Higginson, and EUROIMPACT 2014. “Implementing Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Palliative Care Clinical Practice: A Systematic Review of Facilitators and Barriers.” Palliative Medicine 28 (2): 158–175. doi:10.1177/0269216313491619.

- Appleby, H., and S. Tempest. 2006. “Using Change Management Theory to Implement the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in Clinical Practice.” British Journal of Occupational Therapy 69 (10): 477–480. doi:10.1177/030802260606901007.

- Atkins, L., J. Francis, R. Islam, D. O'Connor, A. Patey, N. Ivers, R. Foy, et al. 2017. “A Guide to Using the Theoretical Domains Framework of Behaviour Change to Investigate Implementation Problems.” Implementation Science 12 (1): 77. doi:10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9.

- Barker, F., L. Atkins, and S. de Lusignan. 2016. “Applying the COM-B Behaviour Model and Behaviour Change Wheel to Develop an Intervention to Improve Hearing-Aid Use in Adult Auditory Rehabilitation.” International Journal of Audiology 55 (sup3): S90–S98. doi:10.3109/14992027.2015.1120894.

- Barker, F., S. Lusignan, and C. Deborah. 2018. “Improving Collaborative Behaviour Planning in Adult Auditory Rehabilitation: Development of the I-PLAN Intervention Using the Behaviour Change Wheel.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 52 (6): 489–500. doi:10.1007/s12160-016-9843-3.

- Blazer, D., S. Domnitz, and C. Liverman. 2016. “Hearing Health Care Services: Improving Access and Quality.” In Hearing Health Care for Adults: Priorities for Improving Access and Affordability, edited by E.a.M. National Academies of Science, 75–148. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK385310/.

- Boaz, A., S. Hanney, T. Jones, and B. Soper. 2015. “Does the Engagement of Clinicians and Organisations in Research Improve Healthcare Performance: A Three-Stage Review.” BMJ Open 5 (12): e009415. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009415.

- Boisvert, I., J. Clemesha, E. Lundmark, E. Crome, C. Barr, and C. M. McMahon. 2017. “Decision-Making in Audiology: Balancing Evidence-Based Practice and Patient-Centered Care.” Trends in Hearing 21: 2331216517706397. doi:10.1177/2331216517706397.

- Boothroyd, A. 2007. “Adult Aural Rehabilitation: What Is It and Does It work?” Trends in Amplification 11 (2): 63–71. doi:10.1177/1084713807301073.

- Boyce, M. B., J. P. Browne, and J. Greenhalgh. 2014. “The Experiences of Professionals with Using Information from Patient-Reported Outcome Measures to Improve the Quality of Healthcare: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Research.” BMJ Quality and Safety 23 (6): 508–518. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002524.

- Campbell, M., R. Fitzpatrick, A. Haines, A. L. Kinmonth, P. Sandercock, D. Spiegelhalter, P. Tyrer, et al. 2000. “Framework for Design and Evaluation of Complex Interventions to Improve Health.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 321 (7262): 694–696. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7262.694.

- Cane, J., D. O'Connor, and S. Michie. 2012. “Validation of the Theoretical Domains Framework for Use in Behaviour Change and Implementation Research.” Implementation Science 7: 37. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-7-37.

- Colquhoun, H. L., K. Carroll, K. W. Eva, J. M. Grimshaw, N. Ivers, S. Michie, A. Sales, et al. 2017. “Advancing the Literature on Designing Audit and Feedback Interventions: identifying Theory-Informed Hypotheses.” Implementation Science 12 (1): 117. doi:10.1186/s13012-017-0646-0.

- Connell, L. A., N. E. McMahon, J. Redfern, C. L. Watkins, and J. J. Eng. 2015. “Development of a Behaviour Change Intervention to Increase Upper Limb Exercise in Stroke rehabilitation.” Implementation Science 10: 34. doi:10.1186/s13012-015-0223-3.

- Coulson, N. S., M. A. Ferguson, H. Henshaw, and E. Heffernan. 2016. “Applying Theories of Health Behaviour and Change to Hearing Health Research: Time for a New Approach.” International Journal of Audiology 55 (sup3): S99–s104. doi:10.3109/14992027.2016.1161851.

- Craig, P., P. Dieppe, S. Macintyre, S. Michie, I. Nazareth, and M. Petticrew. 2008. “Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: The New Medical Research Council guidance.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 337: a1655. doi:10.1136/bmj.a1655.

- Danermark, B., S. Granberg, S. E. Kramer, M. Selb, and C. Moller. 2013. “The Creation of a Comprehensive and a Brief Core Set for Hearing Loss Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.” American Journal of Audiology 22 (2): 323–328. doi:10.1044/1059-0889(2013/12-0052).

- Danermark, B., A. Cieza, J.-P. Gangé, F. Gimigliano, S. Granberg, L. Hickson, S. E. Kramer, et al. 2010. “International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health Core Sets for Hearing Loss: A Discussion Paper and Invitation.” International Journal of Audiology 49 (4): 256–262. doi:10.3109/14992020903410110.

- Emmons, K. M., B. Weiner, M. E. Fernandez, and S. P. Tu. 2012. “Systems Antecedents for Dissemination and Implementation: A Review and Analysis of measures.” Health Education and Behavior 39 (1): 87–105. doi:10.1177/1090198111409748.

- Flodgren, G., E. Parmelli, G. Doumit, M. Gattellari, M. A. O'Brien, J. Grimshaw, M. P. Eccles. 2011. “Local Opinion Leaders: Effects on Professional Practice and Health Care Outcomes.” The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: Cd000125. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000125.pub4.

- Greenhalgh, J. 2009. “The Applications of PROs in Clinical Practice: What Are They, Do They Work, and Why?” Quality of Life Research 18 (1): 115–123. doi:10.1007/s11136-008-9430-6.

- Greenhalgh, J., A. F. Long, and R. Flynn. 2005. “The Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Routine Clinical Practice: Lack of Impact or Lack of theory?” Social Science and Medicine 60 (4): 833–843. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.022.

- Greenhalgh, J., K. Gooding, E. Gibbons, S. Dalkin, J. Wright, J. Valderas, N. Black, et al. 2018. “How Do Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) Support Clinician-Patient Communication and Patient Care? A Realist Synthesis.” Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes 2: 42. doi:10.1186/s41687-018-0061-6.

- Hanbury, A. 2017. “Identifying Barriers to the Implementation of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Using a Theory-Based Approach.” European Journal for Person Centered Healthcare 5 (1): 35–44. doi:10.5750/ejpch.v5i1.1202.

- Hatfield, D. R., and B. M. Ogles. 2004. “The Use of Outcome Measures by Psychologists in Clinical Practice.” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 35 (5): 485. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.35.5.485.

- Haverman, L., H. A. van Oers, P. F. Limperg, C. T. Hijmans, S. A. Schepers, S. M. Sint Nicolaas, Chris M. Verhaak, et al. 2014. “Implementation of Electronic Patient Reported Outcomes in Pediatric Daily Clinical Practice: The KLIK Experience.” Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology 2 (1): 50–67. doi:10.1037/cpp0000043.

- Hoffmann, T. C., Glasziou, P. P., Milne, R., Moher, D., et al. 2014. “Better Reporting of Interventions: Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) Checklist and Guide.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 348: g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687

- Horppu, R., K. P. Martimo, E. MacEachen, T. Lallukka, and E. Viikari-Juntura. 2018. “Application of the Theoretical Domains Framework and the Behaviour Change Wheel to Understand Physicians' Behaviors and Behavior Change in Using Temporary Work Modifications for Return to Work: A Qualitative Study.” Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 28 (1): 135–146. doi:10.1007/s10926-017-9706-1.

- Ivers, N., G. Jamtvedt, S. Flottorp, J. M. Young, J. Odgaard-Jensen, S. D. French, M. A. O'Brien, M. Johansen, J. Grimshaw, A. D. Oxman. 2012. “Audit and Feedback: Effects on Professional Practice and Healthcare Outcomes.” The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: Cd000259. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3.

- Kricos, P.B. 2000. “The Influence of Nonaudiological Variables on Audiological Rehabilitation Outcomes.” Ear and Hearing 21 (Supplement): 7s–14s. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2016.01.150141.

- Kwan, B. M., M. R. Sills, D. Graham, M. K. Hamer, D. L. Fairclough, K. E. Hammermeister, A. Kaiser, et al. 2016. “Stakeholder Engagement in a Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measure Implementation: A Report from the SAFTINet Practice-Based Research Network (PBRN).” The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 29 (1): 102–115. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2016.01.150141.

- Kyte, D. G., M. Calvert, P. J. van der Wees, R. ten Hove, S. Tolan, and J. C. Hill. 2015. “An Introduction to Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) in Physiotherapy.” Physiotherapy 101 (2): 119–125. doi:10.1016/j.physio.2014.11.003.

- Locklear, T. M. B., J. H. Willig, K. Staman, N. Bhavsar, K. Wienfut., et al. 2014. Strategies for overcoming barriers to the implementation of Patient-Reported Outcomes Measures – An NIH Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory Patient Reported Outcomes Core White Paper. Accessed 9 July 2018. https://www.nihcollaboratory.org/Products/Strategies-for-Overcoming-Barriers-to-PROs.pdf.

- Macefield, R. C., M. Jacobs, I. J. Korfage, J. Nicklin, R. N. Whistance, S. T. Brookes, M. A. G. Sprangers, et al. 2014. “Developing Core Outcomes Sets: Methods for Identifying and Including Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs).” Trials 15 (1): 49. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-15-49.

- Mangurian, C., G. C. Niu, D. Schillinger, J. W. Newcomer, J. Dilley, and M. A. Handley. 2017. “Utilization of the Behavior Change Wheel Framework to Develop a Model to Improve Cardiometabolic Screening for People with Severe Mental Illness.” Implementation Science 12 (1): 134. doi:10.1186/s13012-017-0663-z.

- Mc Sharry, J., P. Murphy, and M. Byrne. 2016. “Implementing International Sexual Counselling Guidelines in Hospital Cardiac Rehabilitation: Development of the CHARMS Intervention Using the Behaviour Change Wheel.” Implementation Science 11 (1): 134. doi:10.1186/s13012-016-0493-4.

- Meyer, C., C. Grenness, N. Scarinci, and L. Hickson. 2016. “What Is the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health and Why Is It Relevant to Audiology?” Seminars in Hearing 37: 163–186. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1584412.

- Michie, S., L. Atkins, and R. West. 2014. The Behaviour Change Wheel. A Guide to Designing Interventions. London: Silverback Publishing.

- Michie, S., M. M. van Stralen, and R. West. 2011. “The Behaviour Change Wheel: A New Method for Characterising and Designing Behaviour Change interventions.” Implementation Science 6: 42. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-42.

- Michie, S., M. Richardson, M. Johnston, C. Abraham, J. Francis, W. Hardeman, M. P. Eccles, et al. 2013. “The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 46 (1): 81–95. doi:10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6.

- Moodie, S. T., A. Kothari, M. P. Bagatto, R. Seewald, L. T. Miller, and S. D. Scollie. 2011. “Knowledge Translation in Audiology: Promoting the Clinical Application of Best evidence.” Trends in Amplification 15 (1): 5–22. doi:10.1177/1084713811420740.

- Nancarrow, S. A., and A. M. Borthwick. 2005. “Dynamic Professional Boundaries in the Healthcare Workforce.” Sociology of Health and Illness 27 (7): 897–919. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2005.00463.x.

- Noonan, V. K., A. Lyddiatt, P. Ware, S. B. Jaglal, R. J. Riopelle, C.O. Bingham, S. Figueiredo, et al. 2017. “Montreal Accord on Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) Use series – Paper 3: Patient-Reported Outcomes Can Facilitate Shared Decision-Making and Guide Self-Management.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 89: 125–135. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.04.017.

- Santana, M. J., L. Haverman, K. Absolom, E. Takeuchi, D. Feeny, M. Grootenhuis, G. Velikova, et al. 2015. “Training Clinicians in How to Use Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Routine Clinical Practice.” Quality of Life Research 24 (7): 1707–1718. doi:10.1007/s11136-014-0903-5.

- Snyder, C. F., N. K. Aaronson, A. K. Choucair, T. E. Elliott, J. Greenhalgh, M. Y. Halyard, R. Hess, et al. 2012. “Implementing Patient-Reported Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice: A Review of the Options and Considerations.” Quality of Life Research 21 (8): 1305–1314. doi:10.1007/s11136-011-0054-x.

- Stover, A. M., and E. M. Basch. 2016. “Using Patient-Reported Outcome Measures as Quality Indicators in Routine Cancer Care.” Cancer 122 (3): 355–357. doi:10.1002/cncr.29768.

- Swinkels, R. A. H. M., G. M. Meerhoff, J.W. H. Custers, R. P. S. van Peppen, A. J. H. M. Beurskens, and H. Wittink. 2015. “Using Outcome Measures in Daily Practice: Development and Evaluation of an Implementation Strategy for Physiotherapists in The Netherlands.” Physiotherapy Canada 67 (4): 357–364. doi:10.3138/ptc.2014-28.

- US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Center for Biologics Evalation and Research (CBER) and Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH). 2009. Guidance for Industry: Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Accessed 9 December 2018. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm193282.pdf.

- Valderas, J. M., J. Alonso, and G. H. Guyatt. 2008. “Measuring Patient-Reported Outcomes: Moving from Clinical Trials into Clinical Practice.” Medical Journal of Australia 189 (2): 93–94.

- van Leeuwen, L. M., M. Pronk, P. Merkus, S. T. Goverts, C. B. Terwee, et al. “Operationalization of the Brief ICF Core Set for Hearing Loss: An ICF-Based e-Intake Tool in Clinical Otology and Audiology Practice.” [under Review]

- van Leeuwen, L. M., M. Pronk, P. Merkus, S. T. Goverts, J. R. Anema, and S. E. Kramer. 2018. “Barriers to and Enablers of the Implementation of an ICF-Based Intake Tool in Clinical Otology and Audiology Practice – a Qualitative Pre-Implementation Study.” PLoS One 13 (12): e0208797. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208797.

- van Leeuwen, L. M., P. Merkus, M. Pronk, M. van der Torn, M. Maré, S. T. Goverts, S. E. Kramer, et al. 2017. “Overlap and Nonoverlap between the ICF Core Sets for Hearing Loss and Otology and Audiology Intake Documentation.” Ear and Hearing 38 (1): 103–116. doi:10.1097/AUD.0000000000000358.

- Vas, V., M. A. Akeroyd, and D. A. Hall. 2017. “A Data-Driven Synthesis of Research Evidence for Domains of Hearing Loss, as Reported by Adults with Hearing Loss and Their Communication Partners.” Trends in Hearing 21: 2331216517734088. doi:10.1177/2331216517734088.

- Wintner, L. M., M. Sztankay, N. Aaronson, A. Bottomley, J. M. Giesinger, M. Groenvold, M. A. Petersen, et al. 2016. “The Use of EORTC Measures in Daily Clinical practice-A Synopsis of a Newly Developed manual.” European Journal of Cancer 68: 73–81. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2016.08.024.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2001. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization.