Abstract

Objective

To estimate the prevalence of severe dual sensory loss (DSL) among older persons (aged ≥65 years) in the Swedish population, to identify the diagnoses that cause severe DSL, and to identify rehabilitation services in which the participants have been involved.

Design

A cross-sectional design was applied. Medical records from Audiological, Low Vision, and Vision clinics from two Swedish counties were used.

Study sample

1257 adults, aged ≥65 years with severe hearing loss (HL) (≥70 dB HL) were included, whereof 101 had decimal visual acuity ≤0.3.

Results

Based on the population size in the two counties (≥65 years, n = 127,638), the prevalence of severe DSL was approximately 0.08% in the population. Within the group having DSL (n = 101), 61% were women and 71% were aged ≥85 years. Common diagnoses were cataract and/or age-related macular degeneration (AMD) in combination with HL. The rehabilitation services offered were mainly hearing aids and various magnifiers.

Conclusions

The study confirmed previous results, indicating that the prevalence of severe DSL increases with age and that sensorineural HL and cataract, AMD or glaucoma coexist. The identified rehabilitation services mainly focussed on either vision loss or HL but not on severe DSL as a complex health condition.

Introduction

The number of individuals aged 65 years or older will increase substantially in the next few years worldwide (WHO Citation2015). In Europe, estimates predict that the number of older people will double in the next 50 years from 87.5 million in 2010 to 152.6 million in 2060 (European Commission Citation2014). According to Statistics Sweden (2019), people aged 65 years and older comprise approximately 20% of the 10 million people living in Sweden in Citation2019. With increasing age, the risk for the individual to develop more than one health condition also increases. In a review by Marengoni et al. (Citation2011), multi-morbid conditions were reported to affect greater than half of the older population. Two common age-related health conditions are vision loss (VL) and hearing loss (HL) (WHO Citation2015). In the current article, decimal notation for visual acuity is applied. The usage of decimal notation is dominant when describing visual acuity in the Western World (Hyvärinen and Jacob Citation2011). Globally, 252.6 million people have low vision, (visual acuity of 0.3 or lower at distance in the better eye) and approximately 80% of these persons are ≥50 years old (Bourne et al. 2017). According to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), VL at distance is defined as moderate when the visual acuity in the better eye is less than 0.33, severe at <0.1 and as blindness when the visual acuity is less than 0.05 (WHO Citation2018). The most common diagnoses for VL are cataract, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy. The prevalence of all these increases with age (Klein and Klein Citation2013; Flaxman et al. Citation2017). The WHO (Citation2012) estimates that more than 100 million adults aged 65 years and older experience moderate to profound hearing loss in the better ear based on pure tone average (≥41 dB HL). The hearing loss (HL) can be sensorineural, conductive, or a combination of the two (WHO Citation2006). According to Hoff et al. (Citation2020) sensorineural hearing loss, specifically of cochlear origin, is the most common hearing loss for adults 70 years of age and older. HL is commonly categorised according to the degree of the loss in the better ear based on pure tone average: mild (20–40 dB), moderate (41–70 dB), severe (71–94 dB), and profound (≥95 dB) (Martin et al. Citation2001). As shown in the study by Chia et al. (Citation2006), a correlation exists between HL and two vision diagnoses, cataract and AMD, in older persons. Age has proven to be a risk factor for the coexistence of HL and cataract, AMD or glaucoma (Kim et al. Citation2019). Guthrie et al. (Citation2016) also confirmed that older persons with dual sensory loss (DSL) were more likely to be diagnosed with cataract or glaucoma than individuals without DSL. Research has also identified a higher risk of multi-morbidity for individuals who have DSL (Davidson and Guthrie Citation2019).

Dual sensory loss

Two senses, vision and hearing, work synergistically to perceive information about the world around us (Kolarik et al. Citation2016). When one of the senses is deficient, the other sense becomes more important for the individual. Persons with DSL can have difficulties to compensate for the loss of one sense, with the other, because both senses are deficient (Smith, Bennett, and Wilson Citation2008; Davidson and Guthrie Citation2019). Persons with DSL therefore usually use the tactile sense to receive environmental information and to navigate their surroundings (Arnold and Heiron Citation2002).

The definition of DSL varies between studies (Wittich and Simcock Citation2019). Some studies use criteria based on objective standardised measurements for VL and HL, others use subjective outcomes, and some studies mix standardised measurements with subjective outcomes. Another factor that affects the definition of DSL is that the vision and hearing loss may be categorised from mild to severe forms (Schneider et al. Citation2011). Schneider and colleagues, furthermore argue that subjective outcomes, such as self-reported questionnaires, are more commonly used to define DSL than to use objective measurements. Due to the diverse criteria used to define DSL, comparisons of the results from different studies are difficult. However, researchers tend to agree that the prevalence of DSL increases with age (Jee et al. Citation2005; Schneider et al. Citation2011; Wittich, Watanabe, and Gagne Citation2012; WFDB Citation2018; Wittich and Simcock Citation2019). Considering the aging population in Western countries, the number of people with DSL will naturally increase (Davidson and Guthrie Citation2019).

Because DSL is defined differently in various studies, the global prevalence is difficult to estimate. In an American clinical study using objective criteria for DSL (VL 0.5; HL 40 dB), the prevalence for DSL in older people was estimated to be 3% but increased to approximately 12% when only the oldest age group (85+ years) was considered (Schneck et al. Citation2012). Jee et al. (Citation2005) used the same objective criteria for DSL as Schneck et al. (Citation2012) and found, in a clinical study from Sydney, Australia that 12.2% of the 49 persons (65+ years) who had experienced difficulties managing activities at home and were assessed for care services had DSL. For older persons living in residential care facilities or individuals who received home care in Canada and the Netherlands, the prevalence of DSL was found to be 20% (Roets-Merken et al. Citation2014; Davidson and Guthrie Citation2019). A Swedish register-study used mixed outcomes to define DSL (Turunen-Taheri et al. Citation2017). The definition of VL was based on a question posed to the participants about their vision (“Visual impairment is considered to exist when the patient cannot read the text on the TV or in the newspaper even with glasses” P. 280), and the definition of HL was based on standardised measurements (70 dB for HL). The study concluded that the prevalence of DSL among 1479 persons aged 66 years or older was approximately 28% (Turunen-Taheri et al. Citation2017). When using subjective criteria to define DSL, such as self-reported answers to questions, the estimated prevalence of the population (60+ years) in China have been found to be as high as 57% (Heine, Gong, and Browning Citation2019).

Research on how DSL may affect older persons is mainly reported from high income countries. DSL affects many aspects of the older person’s life (Guthrie et al. Citation2016), such as communication in terms of both receiving and conveying information (Jaiswal et al. Citation2018; Davidson and Guthrie Citation2019). Older persons with DSL commonly experience loneliness and social isolation (Schneider et al. Citation2011; Guthrie et al. Citation2016; Jaiswal et al. Citation2018; Davidson and Guthrie Citation2019). Persons with DSL also have an increased risk of falling accidents (Lieberman, Friger, and Lieberman Citation2004; Gopinath et al. Citation2016; Guthrie et al. Citation2016), and the risk of mortality has been described as higher among persons with DSL, even after controlling for age (Gopinath et al. Citation2013; Fisher et al. Citation2014). Health care professionals possess knowledge about the HL or the VL, but not about DSL as a combined and complex health condition (Wittich, Watanabe, and Gagne Citation2012).

In Sweden, health care and rehabilitation services for persons aged 65 years and older with DSL are divided between the Audiological clinic, the Vision clinic and the Low Vision clinic (LVC) (The National Board of Health and Welfare Citation2012). According to the Swedish health care act, all citizen should have access to rehabilitation services (The Swedish Health Care Act Citation2017). The services that are offered and costs are subsidised for all citizens but might differ depending on the region in Sweden in which the person lives. The medical services for lens replacement, eye surgery, eye injections, and medications, among others, are provided at the Vision clinic. The person is mainly required to have a visual acuity in the better eye of 0.3 or lower at distance to receive services at the LVC. The LVC generally provides training in writing, reading and orientation and mobility. The LVC also provides psychosocial support and different assistive devices. The Audiological clinic provides medical and rehabilitation services related to HL, assistive devices such as hearing aids and alert systems, cochlear implants (CI) and psychosocial support (The National Board of Health and Welfare Citation2012).

According to the global report by World Federation of the Deafblind (WFDB Citation2018), increased knowledge about DSL is needed so that national governments become aware of the complexity of DSL and could develop the health care that is provided to individuals with DSL. It is also significant to possess knowledge about prevalence for DSL to be able to plan, allocate resources, educate, and prepare professionals on how to meet the needs of individuals with DSL (Wittich and Simcock Citation2019). Knowledge about the prevalence of DSL among older people in Sweden based on objective vision and hearing criteria is lacking. In addition, few studies have examined the most common diagnoses resulting in DSL and what types of rehabilitation services that are provided to the target group. It is important to improve our knowledge of these aspects because the number of older people will increase significantly worldwide (WHO Citation2015) and most likely cause increased numbers of older persons having DSL.

The aims of the current study were to:

estimate the prevalence of severe DSL in the Swedish population (i.e. adults aged ≥65 years),

identify the diagnoses of VL and HL that causes severe DSL in two Swedish counties, and

identify what types of rehabilitation services have been offered to the target group in a subset of the sample.

Materials and methods

Study design

The current study was a cross-sectional study. Three sources were used to ensure that potential participants in the two counties were identified: medical records, an inquiry to non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and an analysis of The Swedish National Quality Register for severe to profound hearing loss in adults.

Participants

The inclusion criteria for the study were adults aged ≥65 years who resided in county 1 (Värmland) or county 2 (Örebro) and fulfilled the objective standardised measurements for both moderate VL and severe HL (i.e. decimal visual acuity ≤0.3 for distance in the best eye with best correction, and a pure tone average [PTA4] for the frequencies 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz, ≥70 dB HL in the better ear). Despite that the criteria for VL and HL differ concerning moderate VL and severe HL in the current study, the definition severe DSL have been applied here. This matter is because the above criteria can be interpreted as severe due to the combination of losses in these two senses are significant. Two exclusion criteria were used: the absence of visual acuity for distance and reduced visual field (VF), if the visual acuity was ≥0.4. The exclusion criteria for VF were chosen because of the lack of a reliable measurement for VF in the medical records. The degree of HL was based on European Concerted Action Project on Genetic Hearing Impairment (HEAR) (Martin et al. Citation2001), and the degree of vision loss was based on the definition reported by the WHO (WHO Citation2018).

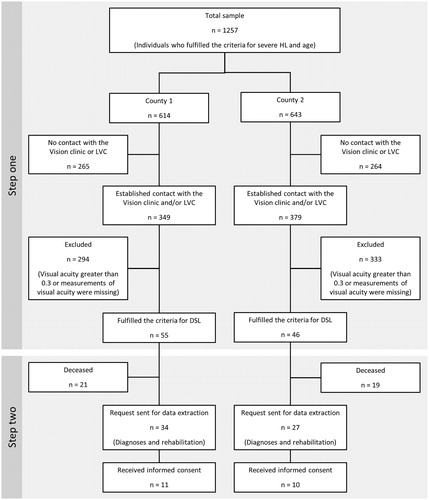

The national Swedish population and the populations in counties 1 and 2 are illustrated in . The two counties were chosen because they are two representative mid-sized counties in Sweden. They are also representative concerning HL prevalence in Sweden. According to the National association for HL (National association for hearing loss (HRF) Citation2017) the prevalence of HL (≥16 years old) in Swedish counties varies between 14.5% and 24.9% in different counties. For the two chosen counties the prevalence for persons with HL were 17.7% and 19.1% respectively. According to Statistics Sweden (Citation2019), data from 2016 illustrate similar population sizes and distributions of age and gender in the two counties.

Table 1. Demographic information for the Swedish population and study population stratified by age and gender.

Procedure

Medical records from 2008 to 2016 obtained from the Audiological, Low Vision, and Vision clinics in the two counties comprised the primary source of information. Data were also subsequently collected from two other sources to identify all persons with DSL according to the inclusion criteria: an inquiry concerning DSL (questions about the vision and hearing of the residents) to members of the NGO in vision and hearing, and an analysis of The Swedish National Quality Register for severe to profound hearing loss in adults. In Sweden, more than 100 national quality registers provide detailed, individual health care information of different types. These registers represent an important resource for population-based research. One of these registers is the Swedish Quality Register of Otorhinolaryngology (Emilsson et al. Citation2015). A sub-register to the Otorhinolaryngology register is the Swedish National Quality Register for severe to profound hearing loss in adults (≥19 years). This register is considered representative of the Swedish population with severe HL. The register contains demographics, health and rehabilitation information, as well as data related to quality of life (The Swedish National Quality Register for Severe to Profound Hearing Loss in Adults Citation2019).

The data were collected in two steps, as shown in . In the first step, data about the prevalence of severe DSL were collected in the two counties. No adjustment for age and gender was conducted. Based on this information, the national prevalence of severe DSL was then determined. The data were collected in May 2017, and the procedure started with searches of medical records from the Audiological clinic in the two counties for participants who fulfilled the criteria of age and HL. In addition, searches for participants in the National Quality Register for severe to profound hearing loss in adults were conducted and resulted in the identification of ten additional individuals who fulfilled the inclusion criteria related to age and HL. In total, 1257 individuals fulfilled the criteria for age and severe HL. The medical records of all these 1257 individuals from the Vision and Low Vision clinics were then manually analysed by two persons from the research team. The most recent recorded distance for visual acuity in the timeframe analysed was used to determine if the person fulfilled the inclusion criteria for DSL. In addition, approximately 600 inquiries concerning DSL were sent by mail to members of the NGOs in the two counties. Of these 600 inquiries, 109 responded, but no additional individuals who fulfilled the inclusion criteria for severe DSL were identified.

Step two in the data collection process focussed on extracting registry data from the medical records of the 101 persons in the two counties who fulfilled the criteria for DSL. The extracted data concerned vision and hearing diagnoses and what rehabilitation services the participant had received. The data collection started in October 2018 and ended in January 2019. A request to access the medical records was sent by mail to subjects identified in the first step, who at this later time point was still alive (n = 61). Informed consent was received from 21 of these subjects, and information about their vision and hearing losses, diagnoses and rehabilitation interventions was extracted from their medical records. One experienced audiologist extracted the data from the medical records of the Audiological clinic and data from the medical records of the Vision and Low Vision clinics were collected by the first author who has expertise in ophthalmology.

Data analyses

According to Statistics Sweden (Citation2019), there were 1,976,797 individuals in Sweden 65 years or older in 2016. Based on the same statistics, county one held 65,305 individuals and county two 62,333 individuals 65 years and older (). The estimation of the prevalence of severe DSL in the two counties were based on the total amount of people with severe DSL in our sample divided with the total population ≥65 years old in the two counties. Based on this information an estimation of the national prevalence of severe DSL was then established by multiplying the percentages with DSL in our sample with the total amount of individuals 65 years and older in Sweden. Prevalence for severe DSL was also estimated in the study sample based on persons with severe HL identified through medical records from the Audiological clinic and The National Quality Register for severe to profound hearing loss in adults. To identify the diagnoses that cause severe DSL, and what types of rehabilitation services the participants had received, categorisation of extracted registry data from the medical records was made.

Table 2. Prevalence of DSL in persons aged 65 or older in counties 1 and 2.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association Citation2018), and the study received ethical approval from the Regional Ethics Committee in Uppsala, Sweden (dnr:2016/046). According to the ethical approval, informed consent was needed from the participants to extract data from their medical records concerning diagnoses and rehabilitation services.

Results

Prevalence

The prevalence of severe DSL in the two counties is illustrated in . The age and gender distributions were quite similar. The mean age of participants residing in county 1 was 87 years (SD = 7) and in county two it was 89 years (SD = 7.4). More women (64%) than men (36%) had severe DSL in county 1. A similar trend was observed for county 2, where 59% of women and 41% of men had severe DSL. However, when analysing potential gender differences in the prevalence of DSL between men and women with DSL (n = 101) or without DSL (n = 127,638) by means of chi square test, no statistical significant differences were found. Based on the search of the medical records from the Audiological clinic and the National Quality Register for severe to profound hearing loss, 1257 individuals had severe HL. One hundred one of these individuals also fulfilled the current criteria for VL. Based on this information, approximately 8% of the persons with severe HL in this sample also had severe DSL.

Based on the population size of older persons in the two counties (Statistics Sweden Citation2019) and the results from the present study where 101 individuals were identified as having DSL, the prevalence of severe DSL is estimated to be 0.08% among older individuals in the two counties. Nationally, in Sweden, 1,976,797 individuals are aged 65 years or older. Based on the findings that approximately 0.08% of persons aged 65 years or older in the two included counties have severe DSL, approximately 1581 individuals in Sweden could have severe DSL, according to the present criteria for DSL.

Diagnoses

Of the 21 individuals who fulfilled the criteria for severe DSL and who provided informed consent for the extraction of their data, 13 were women and 8 were men. The age ranged between 76 and 96 years (M: 86, SD: 6.2). Because of the low number of participants, the results are only presented in age groups and not as regional affiliations. The most common diagnoses were sensorineural HL, AMD and cataract, and approximately 62% (n = 13) of the participants had three or more vision diagnoses in combination with their HL. Approximately 86% (n = 18) had severe HL (70–95 dB), and 43% (n = 9) had a degree of VL lower than 0.1 ().

Table 3. Diagnoses of vision and hearing loss in 21 individuals residing in both counties.

Other documented vision diagnoses included retinal detachment, posterior vitreous detachment and other diseases in the vitreous humour.

Rehabilitation services

As shown in , all 21 individuals were registered patients at the Audiological and the Vision clinics, and 86% of the participants were in contact with the LVC. Audiologists, ophthalmologists, nurses, opticians and occupational therapists were the most common health care professionals from which the participants had received rehabilitation services. also illustrates rehabilitation services that the participants had been offered from the Audiological clinic and from the LVC. The rehabilitation services that were provided from the Vision clinic focussed on medical interventions (i.e. eye injections for treating wet AMD, eye surgery, measuring eye pressure, and pharmaceuticals) and are therefore not presented in .

Table 4. Description of the health care professionals involved and rehabilitation services offered to each age group of persons with DSL.

The documentation in the medical records provided by the social workers was not available in four cases because of professional secrecy. In the other three cases, the social worker had provided assistance with applying for services from authorities, i.e. travel services instead of public transportation. One of the participants had received recurrent psychosocial counselling with the social worker.

One person had received group rehabilitation focussing on DSL. The other 20 persons were involved in specific rehabilitation services provided by the LVC, the Vision clinic or the Audiological clinic, and the rehabilitation had a uni-sensor focus.

The alert systems that were provided from the Audiological clinic included optic signals, acoustics signals or both. Less than half (42%) of the participants had been offered vibro-tactile signals/systems for the doorbell and telephone. Concerning the smoke alarm, two persons had received vibro-tactile alert systems and one person had been provided with both optic signals and amplified audio signals. Other devices were streamers to the hearing aids, conversation amplifiers and FM systems. Half of those individuals who were registered at the LVC had received environmental modifications in the home environment (tactile mark-ups with good contrast mainly to the stove nobs in the kitchen, adaptation to improve light, etc.). Other rehabilitation services provided by the LVC were assistive technologies, such as an audio player, voice recorder, software magnifier and screen reader to make the computer accessible. Furthermore, three persons (17%) of the individuals who had contact with the LVC had declined specific rehabilitation services from the clinic, even though they had indicated that they needed training on how to use magnifying devices, new refraction for the eye glasses and information about methods to improve lighting in the home environment.

The professionals at the LVC documented in the medical records that a person had both a VL and HL to a greater extent (78%) in comparison to the professionals at the Audiological clinic and the Vision clinic (≤50%).

Discussion

Prevalence

The estimate of the national prevalence for severe DSL in Sweden in persons aged 65 years and older based on the criteria for severe DSL in the present study was approximately eight in 10,000 persons (0.08%). The prevalence is somewhat higher in the present study compared to results from a Canadian study by Wittich, Watanabe, and Gagne (Citation2012). They found the prevalence of DSL, in all ages, to be 0.015%. Possible reasons for this matter might be that they included persons in all ages and that the criteria for DSL differed between the studies. In contrast to the results from the current study, another Swedish study investigating 2319 individuals with severe HL, they estimated the prevalence of DSL among persons 66 years or older (1479 individuals) to be 28% (Turunen-Taheri et al. Citation2017). However, the authors used only subjective outcomes to define VL. In the present study, of the population with severe HL (n = 1257), merely 8% also fulfilled the criteria for severe DSL. The research team discussed whether to use the most common diagnoses for VL in older people as an inclusion criterion, similar to the Canadian study (Wittich, Watanabe, and Gagne Citation2012). However, because the LVC provides rehabilitation services and mainly uses the WHO category for moderate VL to offer their services to persons with VL, the specific medical criteria were chosen. If the common diagnoses for VL had been used as a criterion for VL in the present study, the prevalence would have been higher. On the other hand, the range of visual acuity of the individuals would have been broader and the majority would likely had fallen into the WHO category of “no vision loss” or “mild vision loss” (WHO Citation2018). One possible reason for the discrepancy in the criteria of DSL used between countries is that the health care services are organised differently and differences in how people access the services. These matters might have impacted the possibility of reaching a consensus on how to define DSL among the research community.

The gender distribution of persons with severe DSL was 61% for women and 39% for men. However, this difference was not statistically significant. This result is not in line with some previous studies where DSL is reported more prevalent among women than men (Wittich, Watanabe, and Gagne Citation2012; Roets-Merken et al. Citation2014; WFDB Citation2018; Davidson and Guthrie Citation2019). However, in two studies, an opposite distribution was reported (Fisher et al. Citation2014; Hong et al. Citation2016). Based on the information from Statistics Sweden, the distribution of men and women aged 65 years or above in the two counties were not equal. Women outnumbered men by nearly 10,000 individuals. Our results indicate that 71% of those identified with DSL were 85 years or older. Therefore, a possible explanation could be that gender itself is not an important factor for the development of DSL. Arguably, an interpretation of our result could be that more women reach older age in comparison to men, and because DSL increases with age, more women will develop this health condition. Because of the differences between research studies, more research is needed to conclusively determine whether gender differences exist in DSL.

In the present study, the majority of the participants with severe DSL (71%) were identified in the oldest age group (85+ years). In contrast, 7% of the individuals were identified as having DSL in the youngest group (65–74 years). This finding is similar to the results reported by Davidson and Guthrie (Citation2019), who found that 63% of their participants were aged 85 years and older and that approximately 8% were aged between 65 and 74 years. Because the global population is aging (WHO Citation2015) and an older age also increases the likelihood of developing DSL, the numbers of people with DSL are expected to increase in the future.

Diagnoses

The results for the diagnoses causing DSL and rehabilitation efforts should be interpreted with caution due to the low number of participants in this part of the study.

The most common diagnosis of HL was a sensorineural HL. These findings are consistent with the study by Hickson and Scarinci (Citation2007), who concluded that sensorineural HL is the most common type of age-related HL. For VL, the most common diagnoses were AMD, cataract and glaucoma, and the frequency of AMD and cataract increased with age. Based on these results, all the participants in the oldest age group had both AMD and cataract, compared to just over half of the participants in the younger age group. These results are consistent with the results reported by Klein and Klein (Citation2013), who found that these three diagnoses were the most common age-related eye diagnoses and that the frequencies of the diagnoses increased with age. Kim et al. (Citation2019) have also shown that age is a factor contributing to the coexistence of HL and AMD, cataract or glaucoma. One weakness of the present study was the lack of a reliable measurement for VF in the medical records. This limitation is probably one of the reasons why so few of the included persons had diagnoses that affected the visual field. In a Canadian study investigating 564 individuals, only 10% were included based on their reduced visual field (Wittich, Watanabe, and Gagne Citation2012). Thus, in the present study, the vast majority of older persons with severe DSL should be included.

Rehabilitation services

The results illustrate that the rehabilitation services were distinctively divided between the different clinics and that the focus was either on the HL or on the VL. Furthermore, technical solutions were mainly provided. All participants had received one or two hearing aids. This finding is not surprising because the primary rehabilitation intervention for persons with HL is hearing aids (Saunders and Echt Citation2007; Bainbridge and Wallhagen Citation2014). Cochlear implants may be suitable when hearing aids no longer provide communication benefits for the individual. Two participants in the present study had received CIs and three persons had been offered CI. Research studies have showed that a CI may successfully restore the communication capacity and improve the quality of life and the cognitive function for the users (e.g. Tang et al. Citation2017; Mosnier et al. Citation2018; Sorrentino et al. 2020). Furthermore, the tactile sense becomes more important when both the hearing and the vision are affected (Arnold and Heiron Citation2002). Therefore, a positive outcome is that 42% of the individuals had been provided with vibro-tactile alert systems for the doorbell and telephone, but many persons still lack these systems and probably would benefit from them.

A correlation has been established between DSL and poor mental health among older adults (Heine and Browning Citation2014; Cosh et al. Citation2018; Heine, Gong, and Browning Citation2019). Consequently, more than one of the participants in the present study had likely received counselling from a social worker. According to Fraser, Southall, and Wittich (Citation2019), the majority of the health care professionals, other than social workers, often serve as counsellors to their clients with DSL. The counselling mainly concerns the person´s emotional and mental health. However, the professionals claimed that they also served as a “navigator” to guide the person through the health care system to maximise the access to health care services from multiple sources (Fraser, Southall, and Wittich Citation2019). In the present study, no documentation on this matter was identified in the medical records.

When extracting data from the medical records, health care professionals from the Audiological clinic and the Vision clinic to a lesser extent documented that the patient, beyond their HL or VL, had DSL compared to professionals from the LVC. In a study by Dullard and Saunders (Citation2016), the authors concluded that a standard procedure did not exist among the health care professionals to document whether their clients had VL or HL, respectively. As shown in the study by Wittich, Watanabe, and Gagne (Citation2012), health care professionals mainly have knowledge about VL or HL, but not about DSL. This fact might explain why professionals do not mention DSL in the documentation.

In the present study, one of 21 individuals had engaged in specific group rehabilitation with a focus on DSL. Because DSL is a complex health condition (Saunders and Echt Citation2007; Davidson and Guthrie Citation2019) that affects all aspects of the person’s life (Guthrie et al. Citation2016), the health care professionals must provide services that fulfil the individual needs of each patient (Smith, Bennett, and Wilson Citation2008; WFDB Citation2018). Jaiswal et al. (Citation2018) emphasises the importance of developing specific rehabilitation services for persons with DSL to increase their participation and quality of life. However, in a narrative review by Simcock and Wittich (Citation2019) it emerged that older persons with DSL had an increased risk of not being noticed in health care and therefore not got the care they need. Saunders and Echt (Citation2007) claim that research in the field of rehabilitation for older persons with DSL is lacking. According to a study by Wittich et al. (Citation2016), health care professionals desire increased collaboration between the disciplines to improve intervention strategies. The National Board of Health and Welfare (Citation2012) in Sweden also addresses the importance of collaborations between practitioners in different disciplines to ensure the successful development of rehabilitation services for persons with DSL. If the rehabilitation services (i.e. hearing or vision settings) that are offered to older adults with DSL do not consider the needs of and the complexity of DSL, the risk of insufficient rehabilitation and poor health for the target group may increase.

Strengths and limitations

All citizens in Sweden should have access to rehabilitation service according to the Swedish health care act. The National Quality Register for Severe Hearing Loss is a reliable source including almost all adults with severe HL in Sweden. Due to this matter as well as the sampling strategy adopted in this study, the estimate of the national prevalence is considered reliable, but additional research from other counties in Sweden is important to ensure the accuracy of the estimate. The estimated prevalence is low in the present study, and the probable explanation for this low prevalence is the use of strict objective criteria for severe DSL. Some limitations must be considered when collecting data from medical records. For example, no information was provided about the participants’ experiences with the rehabilitation services from the different clinics. Additionally, there were no data of to what extent the participants actually used the different devices they had received, or the perceived benefits of the devices.

Conclusions

The national estimated prevalence of severe DSL was 0.08% in the Swedish population of people aged 65 years and older, based on a sample from two counties. In the sample of the persons with severe HL, 8% were also estimated to have severe DSL. Based on the results, 71% were aged 85 years or older. The most common identified diagnoses resulting in severe DSL were cataract, AMD or glaucoma in combination with sensorineural HL. The rehabilitation focussed mainly on the HL or the VL, but not on the combination of these two conditions. The participants were mainly provided with different assistive devices and did not receive psychosocial support. DSL is a complex health condition and older persons with DSL have a higher risk of loneliness, isolation and poor mental health. Due to these circumstances, it is important for health care professional to be knowledgeable in DSL in order to provide individual health care for these persons. The results from the present study are important for the development of the Swedish health care and rehabilitation services for older persons with severe DSL. Because of the increasing number of older adults, more persons are likely to develop DSL. Thus, more research is still needed in this area.

Geolocation information

Data was collected from two counties in Sweden, Värmland and Örebro. The two counties are representative mid-sized counties in Sweden.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Claes Möller for initiating the project. The authors also thank the health care clinics that participated in the study and Åsa Skagerstrand, the Chairman of the reference group of The Swedish National Quality Register for severe to profound hearing loss in adults, for providing data. The authors also acknowledge Arvid Björndahl for assisting with the extraction and analysis of the data, the NGOs, Hanna Hagsten and Jonas Birkelöf for assisting with the study, and Niklas Karlsson and Sven Crafoord for consultations in ophthalmology.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arnold, P., and K. Heiron. 2002. “Tactile Memory of Deaf-Blind Adults on Four Tasks.” Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 43 (1): 73–79. doi:10.1111/1467-9450.00270.

- Bainbridge, K. E., and M. I. Wallhagen. 2014. “Hearing Loss in an Aging American Population: Extent, Impact, and Management.” Annual Review of Public Health 35 (1): 139–152. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182510.

- Bourne, R., S. Flaxman, T. Braithwaite, M. Cicinelli, A. Das, J. Jonas, J. Keeffe, et al. 2017. “Magnitude, Temporal Trends, and Projections of the Global Prevalence of Blindness and Distance and near Vision Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The Lancet. Global Health 5 (9): e888–e897. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30293-0.

- Chia, E.-M., P. Mitchell, E. Rochtchina, S. Foran, M. Golding, and J. Wang. 2006. “Association Between Vision and Hearing Impairments and Their Combined Effect on Quality of Life.” Archives of Ophthalmology 124 (10): 1465–1470. doi:10.1001/archopht.124.10.1465.

- Cosh, S., T. Hanno, C. Helmer, G. Bertelsen, C. Delcourt, and H. Schirmer, SENSE-Cog Group 2018. “The Association Amongst Visual, Hearing, and Dual Sensory Loss with Depression and Anxiety over 6 years: The Tromsø Study.” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 33 (4): 598–605. doi:10.1002/gps.4827.

- Davidson, J., and D. Guthrie. 2019. “Older Adults with a Combination of Vision and Hearing Impairment Experience Higher Rates of Cognitive Impairment, Functional Dependence, and Worse Outcomes across a Set of Quality Indicators.” Journal of Aging and Health 31 (1): 85–108. doi:10.1177/0898264317723407.

- Dullard, B., and G. Saunders. 2016. “Documentation of Dual Sensory Impairment in Electronic Medical Records.” The Gerontologist 56 (2): 313–317. doi:10.1093/geront/gnu032.

- Emilsson, L., B. Lindahl, M. Köster, M. Lambe, and J. Ludvigsson. 2015. “Review of 103 Swedish Healthcare Quality Registries.” Journal of Internal Medicine 277 (1): 94–136. doi:10.1111/joim.12303.

- European Commission 2014. “Population Ageing in Europe. Facts, Implications and Policies. 2014.” Accessed 28 April 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/research/social-sciences/pdf/policy_reviews/kina26426enc.pdf

- Fisher, D., C.-M. Li, M. Chiu, C. Themann, H. Petersen, F. Jónasson, P. Jonsson, et al. 2014. “Impairments in Hearing and Vision Impact on Mortality in Older People: The AGES-Reykjavik Study.” Age and Ageing 43 (1): 69–76. doi:10.1093/ageing/aft122.

- Flaxman, S. R., R. R. A. Bourne, S. Resnikoff, P. Ackland, T. Braithwaite, M. V. Cicinelli, A. Das, et al. 2017. “Global Causes of Blindness and Distance Vision Impairment 1990-2020: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The Lancet Global Health 5 (12): e1221–e1234. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30393-5.

- Fraser, S. A., K. E. Southall, and W. Wittich. 2019. “Exploring Professionals’ Experiences in the Rehabilitation of Older Clients with Dual-Sensory Impairment.” Canadian Journal on Aging = La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement 38 (4): 481–492. doi:10.1017/s0714980819000035.

- Gopinath, B., C. M. McMahon, G. Burlutsky, and P. Mitchell. 2016. “Hearing and Vision Impairment and the 5-Year Incidence of Falls in Older Adults.” Age and Ageing 45 (3): 409–414. doi:10.1093/ageing/afw022.

- Gopinath, B., J. Schneider, C. M. McMahon, G. Burlutsky, S. R. Leeder, and P. Mitchell. 2013. “Dual Sensory Impairment in Older Adults Increases the Risk of Mortality: A Population-Based Study.” PLoS One 8 (3): e55054. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055054.

- Guthrie, D. M., A. Declercq, H. Finne-Soveri, B. E. Fries, and J. P. Hirdes. 2016. “The Health and Well-Being of Older Adults with Dual Sensory Impairment (DSI) in Four Countries.” PLoS One 11 (5): e0155073. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155073.

- Heine, C., and C. J. Browning. 2014. “Mental Health and Dual Sensory Loss in Older Adults: A Systematic Review.” Front Aging Neurosci 6: 83. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2014.00083.

- Heine, C., C. H. Gong, and C. Browning. 2019. “Dual Sensory Loss, Mental Health, and Wellbeing of Older Adults Living in China.” Front Public Health 7: 92. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2019.00092.

- Hickson, L., and N. Scarinci. 2007. “Older Adults with Acquired Hearing Impairment: Applying the ICF in Rehabilitation.” Semin Speech Lang 28 (4): 283–290. doi:10.1055/s-2007-986525.

- Hoff, M., T. Tengstrand, A. Sadeghi, I. Skoog, and U. Rosenhall. 2020. ” “Auditory Function and Prevalenc of Specific Ear and Hearing Related Pathologies in the General Population at Age 70.” International Journal of Audiology. doi:10.1080/14992027.2020.1731766.

- Hong, T., P. Mitchell, G. Burlutsky, G. Liew, and J. J. Wang. 2016. “Visual Impairment, Hearing Loss and Cognitive Function in an Older Population: Longitudinal Findings from the Blue Mountains Eye Study.” PLoS One 11 (1): e0147646. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147646.

- Hyvärinen, L., and N. Jacob. 2011. What and How Does This Cild See? Assessment of Visual Functioning for Development and Learning. Helsinki: VISTEST Ldt.

- Jaiswal, A., H. Aldersey, W. Wittich, M. Mirza, and M. Finlayson. 2018. “Participation Experiences of People with Deafblindness or Dual Sensory Loss: A Scoping Review of Global Deafblind Literature.” Plos ONE 13 (9): e0203772. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0203772.

- Jee, J., J. J. Wang, K. A. Rose, R. Lindley, P. Landau, and P. Mitchell. 2005. “Vision and Hearing Impairment in Aged Care Clients.” Ophthalmic Epidemiology 12 (3): 199–205. doi:10.1080/09286580590969707.

- Kim, J. M., S. Y. Kim, H. S. Chin, H. J. Kim, and N. R. Kim, Epidemiologic Survey Committee of the Korean Ophthalmological Society, Obot. 2019. “Relationships Between Hearing Loss and the Prevalences of Cataract, Glaucoma, Diabetic Retinopathy, and Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Korea.” Journal of Clinical Medicine 8 (7): 1078. doi:10.3390/jcm8071078.

- Klein, R., and B. E. Klein. 2013. “The Prevalence of Age-Related Eye Diseases and Visual Impairment in Aging: Current Estimates.” Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 54 (14): ORSF5–ORSF13. doi:10.1167/iovs.13-12789.

- Kolarik, A. J., B. C. Moore, P. Zahorik, S. Cirstea, and S. Pardhan. 2016. “Auditory Distance Perception in Humans: A Review of Cues, Development, Neuronal Bases, and Effects of Sensory Loss.” Attention, Perception & Psychophysics 78 (2): 373–395. doi:10.3758/s13414-015-1015-1.

- Lieberman, D., M. Friger, and D. Lieberman. 2004. “Visual and Hearing Impairment in Elderly Patients Hospitalized for Rehabilitation following Hip Fracture.” Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development 41 (5): 669–674. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2003.11.0168.

- Marengoni, A., S. Angleman, R. Melis, F. Mangialasche, A. Karp, A. Garmen, B. Meinow, and L. Fratiglioni. 2011. “Aging with Multimorbidity: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Ageing Research Reviews 10 (4): 430–439. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003.

- Martin, A., M. Mazzoli, D. Stephens, and A. Read. 2001. Definitions, Protocols and Guidelines in Genetic Hearing Impairment.” London: Whurr.

- Mosnier, I., A. Vanier, D. Bonnard, G. Lina-Granade, E. Truy, P. Bordure, B. Godey, et al. 2018. “Long-Term Cognitive Prognosis of Profoundly Deaf Older Adults after Hearing Rehabilitation Using Cochlear Implants.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 66 (8): 1553–1561. doi:10.1111/jgs.15445.

- National association for hearing loss (HRF). 2017. “Hörselskadade i Siffror 2017.” Accessed 14 April 2020. https://hrf.se/app/uploads/2016/06/Hsk_i_siffror_nov2017_webb.pdf

- Roets-Merken, L. M., S. U. Zuidema, M. J. Vernooij-Dassen, and G. I. Kempen. 2014. “Screening for Hearing, Visual and Dual Sensory Impairment in Older Adults Using Behavioural Cues: A Validation Study.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 51 (11): 1434–1440. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.02.006.

- Saunders, G. H., and K. V. Echt. 2007. “An Overview of Dual Sensory Impairment in Older Adults: Perspectives for Rehabilitation.” Trends in Amplification 11 (4): 243–258. doi:10.1177/1084713807308365.

- Schneck, M. E., L. A. Lott, G. Haegerstrom-Portnoy, and J. A. Brabyn. 2012. “Association Between Hearing and Vision Impairments in Older Adults.” Ophthalmic & Physiological Optics : The Journal of the British College of Ophthalmic Opticians (Optometrists) 32 (1): 45–52. doi:10.1111/j.1475-1313.2011.00876.x.

- Schneider, J. M., B. Gopinath, C. M. McMahon, S. R. Leeder, P. Mitchell, and J. J. Wang. 2011. “Dual Sensory Impairment in Older Age.” Journal of Aging and Health 23 (8): 1309–1324. doi:10.1177/0898264311408418.

- Simcock, P., and W. Wittich. 2019. “Are Older Deafblind People Being Left Behind? A Narrative Review of Literature on Deafblindness Through the Lens of the United Nations Principles for Older People.” Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law 41 (3): 339–357. doi:10.1080/09649069.2019.1627088.

- Smith, S. L., L. W. Bennett, and R. H. Wilson. 2008. “Prevalence and Characteristics of Dual Sensory Impairment (Hearing and Vision) in a Veteran Population.” The Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development 45 (4): 597–609. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2007.02.0023.

- Sorrentino, Tommaso, Giulia Donati, Nader Nassif, Sara Pasini, and Luca O. Redaelli de Zinis. 2020. ” “Cognitive Function and Quality of Life in Older Adult Patients with Cochlear Implants.” International Journal of Audiology 59 (4): 316–322. doi:10.1080/14992027.2019.1696993.

- Statistics Sweden (SCB). 2019. “Folkmängden efter region, civilstånd, ålder och kön. År 1968 - 2018.” Accessed 28 April 2020. http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101A/BefolkningNy/

- Tang, L., C. B. Thompson, J. H. Clark, K. M. Ceh, J. D. Yeagle, and H. W. Francis. 2017. “Rehabilitation and Psychosocial Determinants of Cochlear Implant Outcomes in Older Adults.” Ear and Hearing 38 (6): 663–671. doi:10.1097/aud.0000000000000445.

- The National Board of Health and Welfare. 2012. “Rehabilitering för vuxna med syn- eller hörselnedsättning. Landstingens habiliterings- och rehabiliteringsinsatser [Rehabilitation for adults with vision- and hearing loss. Rehabilitation interventions of regions in Sweden].” Accessed 28 April 2020. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2012-1-25.pdf

- The Swedish Health Care Act. 2017. [Hälso- och sjukvårdslag (2017:30). “8kap. Ansvar att erbjuda hälso- och sjukvård”].Accessed 28 April 2020. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/halso-och-sjukvardslag_sfs-2017-30

- The Swedish National Quality Register for Severe to Profound Hearing Loss in Adults. 2019. “Om registret för grav hörselnedsättning hos vuxna.” Accessed 28 April 2020. https://hnsv.registercentrum.se/for-professionen/om-registret-for-grav-horselnedsattning-hos-vuxna/p/HJ_eQtBr7M

- Turunen-Taheri, S., A. Skagerstrand, S. Hellstrom, and P. I. Carlsson. 2017. “Patients with Severe-to-Profound Hearing Impairment and Simultaneous Severe Vision Impairment: A Quality-of-Life Study.” Acta Oto-Laryngologica 137 (3): 279–285. doi:10.1080/00016489.2016.1229025.

- WHO. 2006. “WHO Primary Ear and Hearing Care Training Resource.” Accessed 28 April 2020. https://www.who.int/pbd/deafness/activities/hearing_care/advanced.pdf?ua=1

- WHO. 2012. “WHO Global Estimates on Prevalence of Hearing Loss Mortality and Burden of Diseases and Prevention of Blindness and Deafness.” Accessed 28 April 2020. https://www.who.int/pbd/deafness/WHO_GE_HL.pdf.

- WHO. 2015. “WHO World Report on Ageing and Health.” Accessed 28 April 2020. https://www.who.int/ageing/publications/world-report-2015/en/

- WHO. 2018. “WHO Blindness and Vision Impairment.” Accessed 28 April 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment

- Wittich, W., J. Jarry, G. Groulx, K. Southall, and J.-P. Gagné. 2016. “Rehabilitation and Research Priorities in Deafblindness for the Next Decade.” Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness 110 (4): 219–231. doi:10.1177/0145482X1611000402.

- Wittich, W., and P. Simcock. 2019. “Aging and Combined Vision and Hearing Loss.” In The Routledge Handbook of Visual Impairment, edited by J. Ravenscroft, 438–456. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Wittich, W., D. H. Watanabe, and J. P. Gagne. 2012. “Sensory and Demographic Characteristics of Deafblindness Rehabilitation Clients in Montréal, Canada.” Ophthalmic & Physiological Optics : The Journal of the British College of Ophthalmic Opticians (Optometrists) 32 (3): 242–251. doi:10.1111/j.1475-1313.2012.00897.x.

- World Federation of the Deafblind. 2018. “At Risk of Exclusion from CRPD and SDGs Implementation: Inequality and Persons with Deafblindness (Initial Global Report 2018)”. Accessed 14 April 2020. http://www.wfdb.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/WFDB-global-report-2018.pdf

- World Medical Association 2018. “WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects.” Accessed 28 April 2020. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/