Abstract

Objective

Rehabilitation options for conductive and mixed hearing loss are continually expanding, but without standard outcome measures comparison between different treatments is difficult. To meaningfully inform clinicians and patients core outcome sets (COS), determined via a recognised methodology, are needed. Following our previous work that identified hearing, physical, economic and psychosocial as core areas of a future COS, the AURONET group reviewed hearing outcome measures used in existing literature and assigned them into different domains within the hearing core area.

Design

Scoping review.

Study Sample

Literature including hearing outcome measurements for the treatment of conductive and/or mixed hearing loss.

Results

The literature search identified 1434 studies, with 278 subsequently selected for inclusion. A total of 837 hearing outcome measures were reported and grouped into nine domains. The largest domain constituted pure-tone threshold measurements accounting for 65% of the total outcome measures extracted, followed by the domains of speech testing (20%) and questionnaires (9%). Studies of hearing implants more commonly included speech tests or hearing questionnaires compared with studies of middle ear surgery.

Conclusions

A wide range of outcome measures are currently used, highlighting the importance of developing a COS to inform individual practice and reporting in trials/research.

Introduction

Treatment options for people with a mixed or conductive hearing loss are rapidly increasing, and now include hearing aids, middle ear surgery, bone-conducting hearing implants or a combination of these. However, while the number of potential treatments has expanded, there is a growing recognition that the evidence to support the potential benefits of many of these treatments is of “moderate” to “very low quality” (Ernst, Todt, and Wagner Citation2016; Mandavia et al. Citation2017; Verhaert, Desloovere, and Wouters Citation2013). Part of the difficulty in assessing the evidence for such treatments is the huge range of outcome measures used by clinicians and researchers. Currently, more than 200 different outcome measures related to hearing loss in adults have been identified in the literature, with only 20% of these reported twice or more (Granberg et al. Citation2014). Similarly, more than 130 different questionnaires have been used to examine hearing loss in adults in the past 50 years (Akeroyd et al. Citation2015). This suggests a plethora of tests being used, with some inevitable overlap and duplication. Furthermore, the reliability, validity and sensitivity of many of these outcome measures have not been determined, making it difficult to compare the relative success of different treatments. In turn, this has led to confusion for clinicians, patients and other stakeholders (e.g., third party payers) alike, and an inability to truly determine if some treatments are more successful or suitable than others.

To address some of these issues, the AURONET group was formed as an international network with an aim to develop patient centred core outcome sets (COS) for mixed/conductive hearing loss (Tysome et al. Citation2015). COS are defined as an agreed minimum set of outcome measures and are recommendations of what should be measured and reported in all trials in a specific area. The use of COS does not restrict researchers from using other additional outcome measures, but there is an expectation that the core outcome measures will always be collected and reported as a minimum. This approach has several advantages such as reducing heterogeneity, increasing statistical power in meta-analyses and reducing the risk of reporting bias, since trial reports will always include presentation of their findings of the COS (Williamson et al. Citation2012).

It is increasingly considered that COS need to reflect meaningful characteristics for health service users, and not just their clinicians (Wright et al. Citation2010). Studies in a range of different health care areas have identified outcomes which patients have described as important to them, but which have not been incorporated into research or COS (Mease et al. Citation2008; Serrano-Aguilar et al. Citation2009). To help address this disparity, a COS methodology, which incorporates the involvement of patients and other stakeholders was developed by the OMERACT (Outcome Measures for Rheumatology Clinical Trials) group (Tugwell et al. Citation2007). De Wit et al. (Citation2013) reported that rheumatology patients involved in the OMERACT process felt outcome measures regarding fatigue, sleep disturbances and flares were important, but these were largely absent in existing rheumatology COS. This then served as an impetus for new programmes of research and new COS which reflected domains that were important for patients, as well as clinicians. We adopted the OMERACT methodology, which has been used by a wide range of groups working on COS across diverse health care areas, including dentistry (Bassi et al. Citation2013), gastroenterology (Cooney et al. Citation2007) and chronic pain (Taylor et al. Citation2016).

We previously defined the core areas (hearing, physical, economic and psychosocial) and established the specific type of hearing loss for which a core set of outcome measures was to be established (conductive and mixed) (Tysome et al. Citation2015). This study aims to identify the outcome measures published in the hearing core area through a scoping review, which are then grouped into domains. This has already been performed for the physical core area, (Johansson et al. Citation2018), with similar work in progress for psychosocial and economic core areas.

Involvement of relevant stakeholders (patients, clinicians, scientists) will later define which domains are most important in each core area through an international focus group. This will determine the candidate outcome measures to include in the core set, using the OMERACT filters: truth, discrimination and feasibility, as well as identifying any gaps where there is a need to develop new instruments as outcome measurements. This will culminate in a final core set of outcome measures which can be used as a guide for individual practices and serve as a standard of reporting in clinical trials (Boers et al. Citation2014; Gagnier et al. Citation2017).

The objective of this review is to identify the currently used outcome measurements relevant to the core area hearing for adults with conductive and/or mixed hearing loss following any intervention such as middle ear surgery, bone-conduction hearing implants and middle ear implants.

The identified outcome measures are thereafter grouped into domains and will form the basis for the next stage of the process. Ultimately, our goal is to determine and develop a patient centred COS for mixed/conductive hearing loss for the first time.

Methods

This review was prospectively registered in the PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews (CRD42016039703) (Tysome et al. Citation2016) and adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines (Moher et al. Citation2015) (Supporting Information 1).

The AURONET group received a grant to support the meetings from Oticon Fonden (Denmark). This article represents a scoping review of previously published articles, and no patient identifiable details are included.

Eligibility criteria

Articles published between 2006 and 2016 were included which reported an outcome measure from a treatment of mixed and/or conductive hearing loss. This period was chosen as it was likely to contain the vast majority of outcome measures published. This included randomised clinical trials, comparative and observational studies, case-control studies and case series for adults (16+ years). Studies with outcome measures from adults and children were included only when the data for adults was reported separately. In this instance only, the adult data were included, but the results for the children were not. Articles were excluded if there were less than four participants, they were not written in English or they were reviews.

Search strategy

Both qualitative and quantitative studies were sought, and no study design limits imposed on the search. MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycInfo, Science Direct and the ISI Web of Science were searched for articles published between 2006 and 2016. Grey literature (e.g. literature not formally published in books or articles) was not included in this review. The Search strategy can be seen in full in Supporting Information 2 and was developed with the assistance of a Health Sciences Librarian (Lauren P Cantwell, MSLIS) who has expertise in scoping review searching.

Data management and extraction

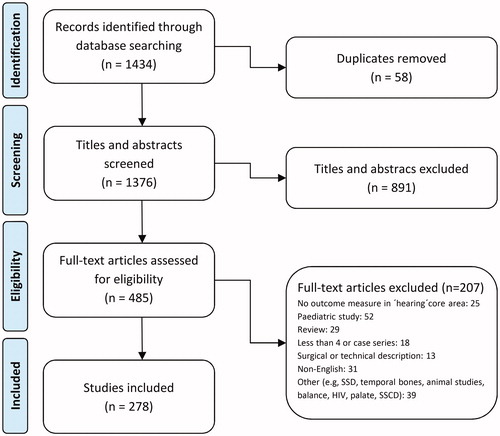

An initial list of 1434 articles was generated by the search. These articles were then divided equally between pairs of authors for screening. Each author initially screened the list of references independently of the other before comparing with their partner, and any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Authors then examined the full text of each article (again independently of their partner) to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis, before again comparing with their partner. Reasons for article exclusions and any disagreements were recorded and where any disagreement remained, this was resolved by consultation with the wider group of authors in order to minimise the risk of any bias. The selection process is shown in the flow chart (). We did not analyse the quality of any study or outcome measure, but rather sought to examine the range of outcome measures with respect to the hearing core area which are in current use.

Once eligible articles had been identified, all data were extracted and entered into a database (FileMaker 15 Pro Advanced, version 15.0.04.400, FileMaker, Inc, Santa Clara) by author “AO”. This included (where explicitly provided): the type of study; type of hearing loss and any interventions and/or devices were recorded. All outcome measures which were hearing/audiological were identified and recorded in the database, including questionnaires.

Each identified outcome measure in the hearing core area was assigned a domain during a consensus meeting of the authors in Nijmegen, 2017. The first author was then responsible for separating, analysing and summarising the data items related to hearing outcomes after these domains had been identified. As described above, the other authors catalogued and classified outcomes, examined data, wrote and edited portions of this manuscript and contributed their expertise to design of the review. The primary result of the analysis was a list of outcome measures which were Hearing or Auditory related. Questionnaires containing hearing outcome measures were reviewed in detail and the audiological outcome measures extracted. These questionnaires often overlapped with outcomes measures in the psychosocial domain, and so appear in the analysis for both hearing and psychosocial core areas.

Results

The literature search identified a total of 1434 titles. Following an initial screen, 485 publications were included for further consideration. After reviewing the full-text articles and removing those which did not meet the inclusion criteria, 278 articles contained hearing outcome measures and so were included in this data set (, Supporting Information 3). There were 837 hearing outcomes reported in total.

The single most common disorder investigated by the papers included in this review was some kind of Ossicular problem and/or Otosclerosis (n = 115). The other main disorders focussed on were Chronic Ear Disease (n = 68), Cholesteatoma (n = 51), Hearing Loss (any configuration; n = 46) and Atresia (n = 31). The majority of interventions to treat these conditions were some kind of middle ear surgery (60%) or the placement of a hearing implant (37%; ).

Table 1. List of the interventions performed or devices used for the treatment of mixed and conductive hearing loss.

Where the type of study had been recorded or was clearly identifiable, the majority were described as “retrospective” (n = 132). Of these, a greater proportion investigated some kind of middle ear surgery, with only about a fifth of the articles examininga hearing implant (). There were fewer “prospective” studies (n = 65). These were more evenly divided between investigations of hearing implants and middle ear surgery (). Finally, the identified hearing outcome measures were grouped into nine domains ().

Table 2. List of the study type and main outcome measures (excluding hearing threshold outcome measures) for the treatment of mixed and conductive hearing loss detailed by study type (Hearing Implant or Ear Surgery).

Table 3. List of domains within the hearing core area and the hearing outcome measures recorded within each and its frequency of use.

Of the articles included in this review, 146 contained only hearing outcome measurements, whilst the remaining 132 papers contained a variety of outcome measures spanning more than 1 core domain (e.g. containing economic, psycho-social or physical outcome measurements).

Less than 10% of the studies omitted measurements of hearing threshold (n = 26), and these were nearly all studies of hearing implants (n = 23). Instead the majority of these implant investigations used a questionnaire (n = 10), speech or speech in noise testing (n = 5), or both a questionnaire and some kind of speech test (n = 5). The 3 other hearing implant studies in this category used electrophysiological tests (n = 2) or a binaural test as their hearing outcomes. A further 3 studies of surgical interventions reported measures of immittance (n = 2), a binaural measurement (n = 1) or a performance measurement (n = 1) as their hearing outcomes rather than any measure of hearing threshold.

Outcomes measurements used within the domain of ‘hearing threshold’

Measures of “hearing threshold” were the most common type of hearing outcome measurement recorded, with 540 occurrences (). Eight tests accounted for 97% of all reported hearing threshold domain outcome measurement: air-bone gap (n = 168), pure tone average (n = 120), bone conduction thresholds (n = 79), air conduction thresholds (n = 74), functional gain (n = 35), soundfield thresholds (n = 26), soundfield aided thresholds (n = 12) and air conduction gain (n = 11); ().

Outcome measurements within the domain of “speech testing”

Tests using speech material were the second most commonly reported hearing outcome measure (n = 171; ). The majority of studies which used any kind of speech test were those investigating some kind of hearing implant (). The speech tests used encompassed a wide range of variables, such as the language and the type of speech material used (sentences, words, phonemes), whether the presentation levels were fixed or adaptive, testing in quiet or in noise, aided or unaided, etc. Despite this, studies reported their results in two main ways: The most commonly reported outcome measurements were Discrimination Scores or Recognition Scores, where the number of words, phonemes or sentences correctly repeated is expressed as a percentage. These were reported in 56% of studies (n = 96; ). The second most commonly reported measure was some kind of Speech Reception Thresholds (SRT), which is typically the level at which 50% of the speech material is repeated correctly. Although different levels, signals and signal-to-noise ratios were used, this type of measurement was used in 43% of the studies (n = 74). A Speech Recognition Index was used in just one study.

A minority of studies tested speech perception in the presence of background noise (n = 29). For example, the Hearing In Noise Test (HINT) which measures an SRT for sentences in quiet and noise, was used just four times. All of these studies were an investigation of some kind of hearing implant and were not used in any studies of middle ear surgery.

Outcome measurements related to questionnaires

Questionnaires were the third most commonly used outcome measurement (n = 74; ). The majority of the studies which used questionnaires were of some kind of hearing implant (n = 66) with only 11% of studies of middle ear surgery using a validated hearing questionnaire (). Of the 14 validated or named questionnaires used, the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB; n = 23) and the Speech, Spatial and Qualities Hearing Scale (SSQ; n = 10) were most frequently used (). These encompass questions regarding speech, speech in noise, and sound quality, as well as other hearing/listening situations, and therefore span across several domains. An additional 18 studies reported non-validated “in-house” questionnaires. (nearly a quarter of all the questionnaires used), with each reported only once. Of these, 13 (72%) were studies of hearing implants, and 5 (28%) were studies of middle ear surgery ().

Other domains

Measures in the domains of immittance testing, binaural processing, electrophysiology, tinnitus, device output and performance were less commonly reported and accounted for just 6% (n = 52) of all outcome measures identified in this review (). As mentioned above, <1% of the total outcome measures solely reported one of these outcomes without also recording an outcome measure of hearing threshold, speech testing or a questionnaire.

The domain of immittance contains objective outcome measurements of middle ear function; tympanometry (n = 10), ear-canal reflectance (n = 4) and umbo velocity (n = 2) and the related measurement of acoustic reflexes (n = 3). The measurements of ear-canal reflectance and umbo velocity were only ever used in studies of middle ear surgery. The outcome measurements of tympanometry and acoustic reflexes were used in both studies of middle ear surgery (n = 8) and middle ear implants (n = 5). It is perhaps unsurprising that they were not used in studies of bone conduction hearing devices, as these bypass the middle ear to stimulate the cochlear directly.

In the domain of Binaural processing, 70% of the reported outcomes used some kind of sound localisation test. But in a similar fashion to the range of variables identified in the domain of speech testing, comparison between studies in the binaural domain is again hampered by the use of different stimulus types, stimulus levels, test procedure, etc. The majority of the studies with binaural processing outcome measurements were reporting on an intervention with a hearing implant (n = 7), with only three studies of middle ear surgery reporting an outcome measurement in this domain (). Two of the 10 studies of binaural processing did not include any measure of hearing threshold, speech testing or a hearing questionnaire. One of these was a study looking at a hearing implant, the other was examining middle ear surgery.

For the domain of electrophysiology, the majority of studies were investigating a hearing implant (n = 7; 70%). The different tests reported reflected different stages of the auditory pathway , from the outer hair cells (OAE measurements, n = 1) to the brainstem (ABR; n = 3, Compound Action Potentials; n = 1 and ASSR, n = 1) and the cortex (Cortical Auditory Evoked Potentials, n = 3). One study investigating middle ear effusion reported measuring Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials. alongside tympanometry and pure tone audiometry as hearing outcome measures. However, two of the studies in this domain did not report any measure of pure tone behavioural testing, speech testing or hearing questionnaire.

In the domain of Tinnitus, all but one study used a measure of hearing threshold, speech testing and/or a hearing questionnaire, as well as a tinnitus outcome measure. A verbal report from the patient (n = 7) was the most frequently used tinnitus specific outcome measure. One study used a visual analogue 10 point scale corresponding to different severities of their tinnitus, and another single study used a six point scale and asked participants to rate any tinnitus. Only two of the studies which had any kind of tinnitus outcome measurement were implant studies, with most interventions relating to some kind of middle ear surgery (n = 7).

Discussion

This review aimed to identify which outcome measures are currently used to evaluate treatments for conductive or mixed hearing loss, and to group them into domains. No single outcome measurement was reported in all studies, howevernearly all studies reported some kind of measure of hearing threshold. The data suggest that the two main types of interventions used for this type of hearing loss often have a different profile of additional outcome measures, with hearing implant studies more commonly reporting speech testing (especially speech in noise testing) and questionnaires as outcome measures compared with studies of middle ear surgery.

Due to the sensorineural component in a mixed hearing loss, a different pattern of complaints and results is possible in comparison with a pure conductive loss. Where the loss is conductive, once sound reaches the cochlea it will be processed normally. However, for a mixed loss, the consequences of damage to the outer hair cells result in broader auditory filters and a loss in auditory resolution and speech clarity, especially in noise). This may explain why speech in noise tests were more likely to be included in studies of hearing implants (where patients may have a mixed loss) and were not used at all in studies of surgical interventions for conductive losses where such changes were not anticipated. Importantly, matching of the output of hearing devices to a prescribed target for audibility assessment is very rarely performed. Recently, efforts have been made to address this lack of fitting to a target on an individual basis, but these initiatives will require time to reach a broader clinical and research usage (Hodgetts and Scollie Citation2017). Consequently, there is currently a considerable uncertainty about the underlying audibility for the conductive and mixed hearing loss groups following treatment. Therefore, in the final stage of the Auronet process (determining a core set of outcome measures) our aim is to ensure that interventions first maximise audibility and then decide if different interventions and/or different pathologies indicate the need for different or additional core outcome measures.

Audiometry-based measurements (e.g., air-bone gap) dominated the reported outcomes in this review, consisting of around to two-thirds of all outcomes extracted (). Indeed, only 26 studies included a hearing outcome measurement without also including some kind of hearing threshold. Whilst international test standards ensure audiometry-based tests give reliable and objective information, the detection of tones in quiet alone is a poor indicator of the overall impact of an individual’s hearing loss. For example, the ability to hear and understand complex real-world signals, such as speech, particularly in the presence of background noise is widely reported to be a crucial factor for adults seeking help with hearing loss (Gatehouse Citation1999; Kochkin Citation2000). Our review shows that the domain of “speech testing” was the second largest group of outcome measures. However, the majority of these were tests performed in quiet, with very few studies testing speech perception in the presence of background noise. For example, the Hearing In Noise Test (HINT) which measures an SRT for sentences in quiet and noise, was used just four times (0.5% of all outcomes) and only in studies relating to a hearing implant.

Similarly, it is estimated that 65–90% of patients with Otosclerosis experience tinnitus as well as hearing loss (Skarżyński et al. Citation2018), and many studies have shown the negative impact that tinnitus may have on quality of life (Watts et al. Citation2018). However, despite Ossicular problems and/or Otosclerosis being the single most reported condition in our review, no standardised outcome measurement of tinnitus (e.g., validated questionnaire or measurement such as acuphenometry) was used as an outcome measure and the presence of any tinnitus itself was only reported in 1% of the total papers (although it is important to remember that the search criteria did not explicitly include “tinnitus”). Where the literature search identified standardised measures of tinnitus, the nature of the measurement has been examined. When these measurements were more related to psychosocial aspects of mixed and/or conductive hearing loss (e.g., Tinnitus Handicap Inventory) they were placed in the “Psychosocial” core area, rather than the Hearing core area. However, it is important to note that some measures of tinnitus containing hearing outcome measures are available for use, and so would have been included in this paper if they had been used. For example, the Tinnitus Functional Index contains a subscale examining auditory difficulties attributed to the presence of tinnitus (Meikle et al. Citation2012). The further steps of the AURONET process which engage the input of a broad range of stakeholders will enable us to determine whether aspects of hearing which relate to tinnitus are considered to be important, despite not having been commonly included as hearing outcome measures at the present time.

In summary, the predominance of audiometry-based outcome measurements may have led to a comparative paucity of other outcome measurement being used. A COS containing a broader range of outcome measurements with greater face validity to “real-world” situations would enhance the present evidence base, as well as moving away from a predominately clinician-centred approach, to a more patient-centred one.

Efforts at consensus in this field have been initiated previously. For example, in 1995, the Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium of the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) published guidelines on minimal reporting standards for evaluating hearing outcome measurements for conductive hearing loss (Monsell Citation1995). These were superseded with new guidelines published in 2012 which suggested a minimum of two core outcome measures (word recognition score and average pure tone threshold) were reported for clinical trials losses (Gurgel et al. Citation2012). Whilst these guidelines have been criticised for over simplification (Maier et al. Citation2018), our findings suggest that only a small proportion of studies actually conform to this suggested minimum COS. Despite this, the need and appetite for the use of COS within hearing loss research is still present as shown by reports from different consensus groups (Maier et al. Citation2018), editorial comments (Hall Citation2018) and registration with COS bodies such as COMET (http://www.comet-initiative.org).

The challenge therefore is twofold. First, the most important domains for all stakeholders need to be agreed, and outcome measures fulfilling the OMERACT criteria identified for each of these domains. Second, these findings need to be communicated to all involved in the field, along with the importance and benefits of adopting them. The success of OMERACT in the field of rheumatology and the use of the OMERACT model in other fields of healthcare suggest that it is possible to arrive at a consensus for COS which allow comparison across disciplines (Audiology, Otolaryngology) and borders. Crucially, these need to be relevant to patients, clinicians and other stakeholders.

Therefore, the next step of the AURONET group is to use these results as a basis for stakeholder interviews (including patients and communication partners, clinicians, industry and healthcare managers) to determine which of the domains in the hearing core area are most important to include in the core set. If no suitable measures are found to exist, the development of new outcomes measures (which will again fulfil the OMERACT criteria) will need to be undertaken. Ultimately this process will identify a core set of outcome measures which will reflect the needs of all stakeholders and fulfil the OMERACT requirements.

TIJA-2019-01-0033-File007.docx

Download MS Word (58.4 KB)TIJA-2019-01-0033-File006.docx

Download MS Word (13.7 KB)TIJA-2019-01-0033-File005.docx

Download MS Word (31 KB)Acknowledgments

The AURONET group received a grant to support the meetings from Oticon Foundation (Denmark). The authors wish to acknowledge the research librarian Lauren P. Cantwell, (MSLIS) for work in developing and executing the literature search.

Disclosure statement

MJ and RS are salaried employees of Oticon Medical.

References

- Akeroyd, M. A., K. Wright-Whyte, J. A. Holman, and W. M. Whitmer. 2015. “A Comprehensive Survey of Hearing Questionnaires: How Many Are There, What Do They Measure, and How Have They Been Validated?” Trials 16 (S1): P26–P26. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-16-S1-P26.

- Bassi, F., A. B. Carr, T. L. Chang, E. Estafanous, N. R. Garrett, R. P. Happonen, S. Koka, et al. 2013. “Oral Rehabilitation Outcomes Network-Oronet.” International Journal of Prosthodontics 26 (4): 319–322. doi:10.11607/ijp.3400.

- Boers, M., J. R. Kirwan, G. Wells, D. Beaton, L. Gossec, M. A. D'agostino, P. G. Conaghan, et al. 2014. “Developing Core Outcome Measurement Sets for Clinical Trials: Omeract Filter 2.0.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 67 (7): 745–753. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.013.

- Cooney, R. M., B. F. Warren, D. G. Altman, M. T. Abreu, and S. P. Travis. 2007. “Outcome Measurement in Clinical Trials for Ulcerative Colitis: Towards Standardisation.” Trials 8: 17. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-8-17.

- De Wit, M., T. Abma, M. Koelewijn-Van Loon, S. Collins, and J. Kirwan. 2013. “Involving Patient Research Partners Has a Significant Impact on Outcomes Research: A Responsive Evaluation of the International Omeract Conferences.” BMJ Open 3 (5): e002241. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002241.

- Ernst, A., I. Todt, and J. Wagner. 2016. “Safety and Effectiveness of the Vibrant Soundbridge in Treating Conductive and Mixed Hearing Loss: A Systematic Review.” The Laryngoscope 126 (6): 1451–1457. doi:10.1002/lary.25670.

- Gagnier, J. J., M. J. Page, H. Huang, A. P. Verhagen, and R. Buchbinder. 2017. “Creation of a Core Outcome Set for Clinical Trials of People with Shoulder Pain: A Study protocol.” Trials 18 (1): 336. doi:10.1186/s13063-017-2054-9.

- Gatehouse, S. 1999. “Glasgow Hearing Aid Benefit Profile: Derivation and Validation of a Client-Centered Outcome Measure for Hearing Aid Services.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 10 (2): 80–103.

- Granberg, S., J. Dahlstrom, C. Moller, K. Kahari, and B. Danermark. 2014. “The ICF Core Sets for Hearing loss-researcher perspective. Part I: Systematic review of outcome measures identified in audiological research.” International Journal of Audiology, 53 (2): 65–76. doi:10.3109/14992027.2013.851799.

- Gurgel, R. K., R. K. Jackler, R. A. Dobie, and G. R. Popelka. 2012. “A New Standardized Format for Reporting Hearing Outcome in Clinical Trials.” Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 147 (5): 803–807. doi:10.1177/0194599812458401.

- Hall, D. 2018. Developing outcome measures for research ENT & Audiology news 26, no 6.

- Hodgetts, W. E., and S. D. Scollie. 2017. “Dsl Prescriptive Targets for Bone Conduction Devices: Adaptation and Comparison to Clinical Fittings.” International Journal of Audiology 56 (7): 521–530. doi:10.1080/14992027.2017.1302605.

- Johansson, M. L., J. R. Tysome, P. Hill-Feltham, W. E. Hodgetts, A. Ostevik, B. J. Mckinnon, P. Monksfield, R. Sockalingam, and T. Wright. 2018. “Physical Outcome Measures for Conductive and Mixed Hearing Loss Treatment: A Systematic Review.” Clinical Otolaryngology 43 (5): 1226–1234. doi:10.1111/coa.13131.

- Kochkin, S. 2000. “Marketrak v: “Why my Hearing Aids Are in the Drawer” the Consumers' Perspective.” The Hearing Journal 53 (2): 343639–343641. doi:10.1097/00025572-200002000-00004.

- Maier, H., U. Baumann, W. D. Baumgartner, D. Beutner, M. D. Caversaccio, T. Keintzel, M. Kompis, et al. 2018. “Minimal Reporting Standards for Active Middle Ear Hearing Implants.” Audiology & Neuro-Otology 23 (2): 105–115. doi:10.1159/000490878.

- Mandavia, R., A. W. Carter, N. Haram, E. Mossialos, and A. G. M. Schilder. 2017. “An Evaluation of the Quality of Evidence Available to Inform Current Bone Conducting Hearing Device National Policy.” Clinical Otolaryngology 42 (5): 1000–1024. doi:10.1111/coa.12831.

- Mease, P. J., L. M. Arnold, L. J. Crofford, D. A. Williams, I. J. Russell, L. Humphrey, L. Abetz, and S. A. Martin. 2008. “Identifying the Clinical Domains of Fibromyalgia: Contributions from Clinician and Patient Delphi Exercises.” Arthritis and Rheumatism 59 (7): 952–960. doi:10.1002/art.23826.

- Meikle, M. B., J. A. Henry, S. E. Griest, B. J. Stewart, H. B. Abrams, R. Mcardle, P. J. Myers, et al. 2012. “The Tinnitus Functional Index: Development of a New Clinical Measure for Chronic, Intrusive tinnitus.” Ear and Hearing 33 (2): 153–176. doi:10.1097/AUD.0b013e31822f67c0.

- Moher, D., L. Shamseer, M. Clarke, D. Ghersi, A. Liberati, M. Petticrew, P. Shekelle, and L. A. Stewart and P.-P. Group. 2015. “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (Prisma-p) 2015 Statement.” Systematic Reviews 4: 1. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

- Monsell, E. M. 1995. “New and Revised Reporting Guidelines from the Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium. American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, Inc.” Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 113 (3): 176–178. doi:10.1016/S0194-5998(95)70100-1.

- Serrano-Aguilar, P., M. M. Trujillo-Martin, J. M. Ramos-Goni, V. Mahtani-Chugani, L. Perestelo-Perez, and M. Posada-De La Paz. 2009. “Patient Involvement in Health Research: A Contribution to a Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Treatments for Degenerative Ataxias.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 69 (6): 920–925. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.005.

- Skarżyński, Henryk, Elżbieta Gos, Beata Dziendziel, Danuta Raj-Koziak, Elżbieta A. Włodarczyk, and Piotr H. Skarżyński. 2018. “Clinically Important Change in Tinnitus Sensation after Stapedotomy.” Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 16 (1): 208. doi:10.1186/s12955-018-1037-1.

- Taylor, A. M., K. Phillips, K. V. Patel, D. C. Turk, R. H. Dworkin, D. Beaton, D. J. Clauw, et al. 2016. “Assessment of Physical Function and Participation in Chronic Pain Clinical Trials: IMMPACT/OMERACT recommendations.” Pain 157 (9): 1836–1850. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000577.

- Tugwell, P., M. Boers, P. Brooks, L. Simon, V. Strand, and L. Idzerda. 2007. “Omeract: An International Initiative to Improve Outcome Measurement in Rheumatology.” Trials 8: 38. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-8-38.

- Tysome, J. R., Hill-Feltham, P. W. E. Hodgetts, B. J. Mckinnon, P. Monksfield, S. Kedia, R. Sockalingam, M. L.. and Johansson. S. A. 2016. “Systematic Review of Outcome Measures for Conductive and Mixed Hearing Loss.” In PROSPERO: International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42016039703

- Tysome, J. R., P. Hill-Feltham, W. E. Hodgetts, B. J. Mckinnon, P. Monksfield, R. Sockalingham, M. L. Johansson, and A. F. Snik. 2015. “The Auditory Rehabilitation Outcomes Network: An International Initiative to Develop Core Sets of Patient-Centred Outcome Measures to Assess Interventions for Hearing Loss.” Clinical otolaryngology 40 (6): 512–515. doi:10.1111/coa.12559.

- Verhaert, N., C. Desloovere, and J. Wouters. 2013. “Acoustic Hearing Implants for Mixed Hearing Loss: A Systematic Review.” Otology & Neurotology 34 (7): 1201–1209. doi:10.1097/MAO.0b013e31829ce7d2.

- Watts, E. J., K. Fackrell, S. Smith, J. Sheldrake, H. Haider, and D. J. Hoare. 2018. “Why is Tinnitus a Problem? a Qualitative Analysis of Problems Reported by Tinnitus Patients.” Trends in Hearing 22: 2331216518812250. doi:10.1177/2331216518812250.

- Williamson, P. R., D. G. Altman, J. M. Blazeby, M. Clarke, D. Devane, E. Gargon, and P. Tugwell. 2012. “Developing Core Outcome Sets for Clinical Trials: Issues to consider.” Trials 13: 132. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-13-132.

- Wright, M. T., B. Roche, H. Von Unger, M. Block, and B. Gardner. 2010. “A Call for an International Collaboration on Participatory Research for Health.” Health Promotion International 25 (1): 115–122. doi:10.1093/heapro/dap043.