Abstract

Objective

To explore the perceived benefit and likely implementation of approaches used by audiologists to address their adult clients’ psychosocial needs related to hearing loss.

Design

Adults with hearing loss and audiologists completed separate, but related, surveys to rate their perceived benefit and also their likely use of 66 clinical approaches (divided over seven themes) that aim to address psychosocial needs related to hearing loss.

Study sample

A sample of 52 Australian adults with hearing loss, and an international sample of 19 audiologists.

Results

Overall, participants rated all of the approaches highly on both benefit and likelihood of use; the highest ranked theme was Providing Emotional Support. Cohort comparisons showed that audiologists ranked the approaches significantly higher than did adults with hearing loss. Overall, participants ranked the themes higher on benefit than on the likelihood to use scales.

Conclusions

Adults with hearing loss and audiologists recognise the importance of approaches that address the psychosocial impacts of hearing loss in audiological rehabilitation. However, both groups placed slightly greater value on the internal-based approaches (the clients own emotional response, empowerment, and responsibility), and slightly less emphasis on the external-based approaches (being supported by communication partners, support groups or other health professionals).

Introduction

Hearing loss is an important and growing global public health concern (Mathers, Smith, and Concha Citation2000; Wilson et al. Citation2017). The negative impacts of the condition can concern a range of life domains. Vas and colleagues (2017) have identified the following three domains of hearing loss, as reported by adults with hearing loss and their communication partners: 1) hearing and communication, 2) behaviour and social interaction, and 3) emotions, identity, and psychological well-being. The combined effects of the latter two are often termed “psychosocial”, describing the emotional, psychological, or environmental factors that influence a persons’ physical, mental and functional wellness. Psychosocial impacts of hearing loss include feelings of isolation, loneliness, inferiority, embarrassment, and perceived reliance on significant others (Barker, Leighton, and Ferguson Citation2017; Heffernan et al. Citation2016; Pronk et al. Citation2011; Vas, Akeroyd, and Hall Citation2017; Veiga, Alexandre, and Esteves Citation2015), and may include symptoms of anxiety or depression (Jayakody et al. Citation2018; Keidser and Seeto Citation2017; Lawrence et al. Citation2018). Low levels of psychosocial well-being can be distressing for individuals and can have a detrimental effect on a wide range of physical and mental functions including sleep (Cacioppo et al. Citation2002), immune responses (Hawkley and Cacioppo Citation2003), cardiovascular disease (McDade, Hawkley, and Cacioppo Citation2006), dietary habits (Locher et al. Citation2005), physical activity (Kharicha et al. Citation2007), depression (Kawachi and Berkman Citation2001), cognitive decline and dementia (Cacioppo and Hawkley Citation2009; Gow et al. Citation2007; Wilson et al. Citation2007), and increased mortality (Shiovitz-Ezra and Ayalon Citation2010). In addition, poor psychosocial well-being may negatively impact a client’s utilisation of and success with healthcare (Howell, Kern, and Lyubomirsky Citation2007), including, audiology services (Laird et al. Citation2020).

Clinical guidelines emphasise that audiologists should play a role in addressing the impact of hearing loss on psychosocial function (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Citation2004; Audiology Australia Citation2013; British Society of Audiology Citation2016) even though the guidelines provide no specific applicable instruction. Our recent international study (n = 65 audiologists) identified 93 different approaches that can be employed by audiologists to address their clients’ psychosocial needs associated with hearing loss (Bennett et al. Citation2020a). Despite these encouraging findings, other data suggest that psychosocial support is rarely provided in audiology clinical practices (Bennett et al. Citation2020b; Ekberg, Grenness, and Hickson Citation2014; Grenness, Hickson, Laplante-Levesque, et al. Citation2015). Moreover, there is little point in audiologists using techniques or offering psychosocial support if the clients do not see the benefit and/or are not likely to accept or act upon them. The aim of the current study was to understand this mismatch between approaches identified and their use by examining the utilisation and perceived benefit of the clinical approaches identified in our earlier study. We achieved this by surveying adults with hearing loss and audiologists, to explore the perceived benefit and likely use of clinical approaches applied in the audiology setting to address the psychosocial impacts of hearing loss. We analysed this separately for the two participant groups, in order to explore any differences in their views.

Methods

This study is the second part of a two-part project using concept mapping techniques to explore the clinical approaches taken by audiologists to address their adult clients’ psychosocial needs related to hearing loss. Concept mapping methodology is an established participatory mixed methods approach that combines qualitative techniques to data collection with subsequent quantitative analyses. These produce visual maps of how people view a particular topic (Trochim and Kane Citation2005). Participants generate data for analysis by engaging in three activities: a) brainstorming, b) grouping, and c) rating. In part one of this project, 65 audiologists from different countries were recruited and asked to complete the brainstorming and grouping activities. They generated a list of 93 approaches they said were used by audiologists to address their clients’ psychosocial needs associated with hearing loss, and which were subsequently grouped across seven themes (Bennett et al. Citation2020a). In part two of this project (reported here) the audiologists who participated in part one were included, as well as a new sample of adults with hearing loss, so that both groups could complete the rating activity.

Synopsis: Adults with hearing loss and audiologists participated. Via an electronic survey, both participant groups rated the perceived benefit of and perceived likelihood of use of the approaches identified earlier by the audiologists, to address patients’ psychosocial needs arising from their hearing loss.

Participants

Australian adults with hearing loss were recruited from a hearing clinic in Perth, Western Australia. All clients on the clinic database who were aged 18 years or older, who had indicated a willingness to be contacted for research purposes (indicated by opting in on the client information form at their most recent appointment at the clinic), and who had attended the clinic in the past three years were identified as potential participants. No inclusion or exclusion criteria were placed on demographic factors, hearing sensitivity, or duration or use of hearing amplification devices, to ensure a heterogeneous mix. A pool of 200 of these individuals were selected using a random number generator in Microsoft Excel and were sent an email inviting them to complete the survey. Fifty-two (response rate of 26%), agreed to take part in this second part of the study.

All audiologists (n = 65) who had participated in our previous study (Bennett et al. Citation2020a) were invited to participate in this second study via email. These individuals were based in Australia, Canada, China, Ireland, UK, USA, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. Nineteen audiologists agreed to participate in this rating activity (response rate 29.2%).

Participant characteristics are described in .

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Survey development

The audiologists in Bennett et al. (Citation2020a) generated a list of 93 clinical approaches that they perceived audiologists to be using to address the psychosocial needs of adults with hearing loss. Following the use of concept mapping techniques, these approaches were grouped into the following seven themes, or types of approaches: (1) Including Communication Partners, (2) Promoting Client Responsibility, (3) Use of Strategies and Training to Personalise the Rehabilitation Program, (4) Facilitating Peer and Other Professional Support, (5) Improving Social Engagement with Technology, (6) Providing Emotional Support, and (7) Client Empowerment.

Since we anticipated that having participants rate all 93 approaches for perceived benefit and likelihood of use could be too burdensome, we decided to reduce the number by merging items that described similar approaches. Approaches were only merged if they were from within the same theme, not from different themes. For example, the statement “Listening to the client – sometimes they just need to talk” was merged with “Giving the client time to talk, and listening to what they say” to become Q1. The audiologist gives the client time to talk, and listens to what they say. No new statements were added to the list of approaches.

We anticipated that some of the participating adults with hearing loss may not have been as familiar with the approaches as the audiologists who generated the original list. Thus, some statements were rephrased for ease of understanding, and a description/explanation for some items was included. For example, a definition was provided for the term “hearing therapy” as in the following example: Q29. The audiologist refers clients to hearing therapy (a counselling and support service for people living with hearing loss). The final survey included 66 items across the seven themes (see Supplementary Appendix 1 for the complete survey).

The survey included two response scales evaluating (i) perceived benefit and (ii) perceived likelihood of using each approach on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Extremely Unlikely to 5 = Extremely Likely). Participant groups were asked the same two questions, with the wording of the perceived likelihood of use question slightly altered to reflect whether they were an adult with a hearing loss (receiving psychosocial services) or an audiologist (recommending/delivering psychosocial approaches).

Perceived benefit of each item was measured by asking participants “How likely is it that each of the approaches will help people with a hearing loss improve their social and emotional well-being?”

Perceived likelihood of use was measured by asking:

People with hearing loss: “How likely are you to accept each of the approaches below? If your Audiologist used these approaches with you, or if they recommended these approaches to you, how likely are you to take up the advice and follow through with it?”

Audiologists: “How likely are you to use each of the approaches below? As an audiologist, how likely are you to implement or recommend each of the below approaches to your clients?”

Prior to data collection the survey was pilot tested on five audiologists and five older adults with hearing loss (all recruited from the Perth-based partner clinic) in order to ensure that the survey was appropriate and acceptable for the intended population. Pilot testing was completed using a printed version of the survey. Pilot participants were asked to provide the research team with feedback on how long the survey took to complete and how easy/difficult the wording was to understand. All ten participants indicated that the survey was acceptable, easy to understand, and took between 7 to 20 minutes to complete. No changes to the survey were recommended.

Procedure

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Human Research Ethics Office of The University of Western Australia.

Potential participants were sent an email about the study that included a link to the online survey. The survey was completed within Qualtrics, and in order to reduce the likelihood of participant fatigue/burden, participants had the option to complete the survey over different sessions. Participants were given six weeks to complete the survey. Due to a lower response rate, a reminder email was sent to the audiologist cohort at five weeks if the survey had not yet been completed. No reminders were sent to the adults with hearing loss participant group.

Data analysis

Data were stored and analysed using Microsoft Excel and SPSS Statistics, version 21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Participant’s item scores were averaged within each theme, creating a theme score (continuous data). All data were inspected for outliers (i.e. visual inspection of boxplots) and tests of normality and skewness (i.e. Shapiro–Wilk test of normality and Q-Q plots) were conducted. No outliers were detected and data were not normally distributed. Means and Standard Deviations (SDs) for each of the themes and individual items were tabulated for the two participant groups separately (i.e. distinguishing between adults with hearing loss and audiologists).

It was deemed necessary to first examine the reliability of the grouping structure, as there were fewer items in the survey here than approaches identified in the initial study (66 versus 93). This was achieved by determining the internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for each of the 7 item groups belonging to the themes, separately for each participant group and each rating question. These are shown in Supplementary Appendix 2. There was high internal consistency reliability for all themes and for both rating questions. Specifically, all of the alpha values were >0.6 (i.e. acceptable reliability), with 20 of the 28 scores being >0.8 (i.e. very good reliability; Gliem and Gliem Citation2003).

Data were analysed in three ways. First, the differences in mean rating scores (for perceived benefit and likelihood of use separately) were compared between the participant groups. Levene’s test of homogeneity revealed variances not homogenous within the dataset (<0.05) and as such Mann–Whitney U tests were used. Second, the rank order of the themes were examined (with the participant groups combined), in order to determine which theme, if any, were ranked higher than others in terms of perceived benefit, or likelihood of use. Levene’s test of homogeneity revealed that variances were homogenous (>0.05) and as such Welch’s t-tests were used. Third, the differences in mean rating scores between the perceived benefit and likelihood of use were compared (with the participant groups evaluated separately). Levene’s test of homogeneity revealed that variances were homogenous (>0.05) and as such Welch’s t-tests were used. Due to the large number of t-tests we applied a Bonferroni corrected p value, calculated by dividing 0.05 by the number of t-tests performed within each analysis.

Results

shows the mean scores (SDs) for each theme’s rating scale and for each participant group, along with statistical comparisons between groups (the individual item rating scores are presented in Supplementary Appendix 1). Overall, both participant groups rated all approaches relatively positively (i.e. all mean scores ≥3) on perceived benefit and perceived likelihood of use. Audiologists ranked the approaches significantly higher on perceived benefit than did adults with hearing loss for two of the seven themes: Providing Emotional Support (p = 0.002) and Client Empowerment (p < 0.001). There was no statistically significant difference between groups on the perceived likelihood of use rating scale.

Table 2. Theme mean (SD) scores, by participant type, and comparison between the participant groups means using Mann–Whitney test with Bonferroni corrected p values below 0.007 indicating statistical significance.

Although visual inspection of the mean ratings for each of the themes appear to suggest a rank order, there was no statistically significant difference between the mean ratings when compared between themes (Supplementary Appendices 3 and 4), with the exception of two themes. The two themes Providing Emotional Support, and Promoting Client Responsibility were ranked significantly higher than the other themes by participants on both rating scales, perceived benefit and likelihood of use (Supplementary Appendices 3 and 4).

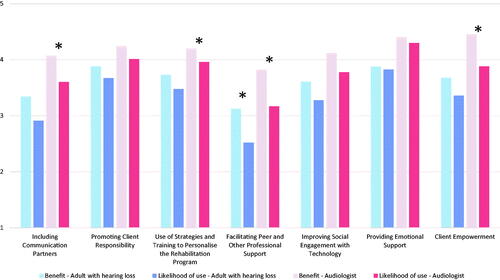

We observed the overall trend that both for the adults with hearing loss and the audiologists’ perceived benefit was generally rated higher than likelihood of use (), but these differed only statistically significantly for four themes for the audiologists, and one for the adults with hearing loss. For the adults with hearing loss participant group, the theme Facilitating Peer and Other Professional Support was rated to be of higher perceived benefit than likelihood of use (p < 0.005). For the audiologist participant group, the seven themes Communication Partners, Use of Strategies and Training to Personalise the Rehabilitation Program, Client Empowerment, and Facilitating Peer and Other Professional Support were rated to be of higher benefit than likelihood of use (p < 0.004). Although it can be debated if the two constructs (perceived benefit and likelihood of use) may be compared directly (see Limitations), we speculate that the differences may indicate that particular strategies that may be viewed as rather beneficial may not be viewed as put into clinical practice easily. For the audiologists, this would then particularly hold for the themes Use of Strategies and Training to Personalise the Rehabilitation Program, Client Empowerment, and Facilitating Peer Support and Other Professional Support’. These results may point towards important needs of the audiologist, i.e. they may highlight the strategies for which audiologists require more support in order for them to put the strategies that they do find important, into their daily practice.

Figure 1. Comparison perceived benefit against perceived likelihood of use for participant mean rating scores for each theme (participant groups analysed separately). Significant differences denoted by *, calculated using independent t-tests with Bonferroni corrected p values below 0.007 indicating significance.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore how audiologists and patients perceived the benefit and likelihood of use of clinical approaches aimed to address the psychosocial needs of adults with hearing loss. The approaches were synthesised in a previous study among the same group of audiologists. Overall, both adults with hearing loss and audiologists rated the benefit and the likelihood of use of all approaches relatively positively (i.e. scores ≥ 3). This finding suggests that both adults with hearing loss and audiologists report value of clinical approaches to address the psychosocial impacts of hearing loss in the audiology setting.

When the types of themes are examined more closely, it becomes apparent that participants (i.e. both audiologists and adults with hearing loss) seem to report greater value on the internal-based approaches (the client’s own emotional response, empowerment, and responsibility), and less emphasis on the external-based approaches (being supported by communication partners, support groups or other health professionals). This is despite the importance of an individual’s social environment and social support in relation to audiological rehabilitative success being evidenced in the literature (Ekberg et al. Citation2015; Hickson et al. Citation2014, Citation2016; Singh, Lau, and Pichora-Fuller Citation2015; Singh et al. Citation2016; Singh and Launer Citation2016; Southall et al. Citation2019). It is possible that the stigma associated with hearing loss fuels individual’s belief’s that they must “do it alone”. As described in the general health literature, the experience of chronic illness is a dynamic state within which the associated physical and psychological distress is exacerbated both by the health condition itself and by the stress imposed by society as a result of how it views the health condition (Joachim and Acorn Citation2016). The literature is abundant with stories of persons with hearing loss describing their journey of hearing loss and (re)habilitation as one of solace, including feeling alone in social situations due to emotional withdrawal (Heffernan et al. Citation2016), rejecting hearing devices due to living a solitary life (Guerra-Zúñiga et al. Citation2014), having to navigate the hearing healthcare system on their own (Laplante-Lévesque et al. Citation2012b), feeling powerless and frustrated when audiological needs are not met (Linssen et al. Citation2013), and having to navigate their unmet needs in the workplace (Jennings and Shaw Citation2008).

The high regard for clinical approaches relating to Providing Emotional Support by both participant groups emphasises the important role that audiologists play in helping their clients adjust to the psychosocial impacts of their hearing loss (Beck and Kulzer Citation2018), and suggests that audiologists’ might need to prioritise their efforts accordingly. Although research involving both adults with hearing loss and audiologists has echoed the importance of providing emotional support during audiology consultations (Bennett et al. Citation2020c; Heffernan et al. Citation2016; Laird et al. Citation2020; Meibos, Muñoz, and Twohig Citation2019), clinical observations suggest that emotional support is infrequently delivered (Bennett et al. Citation2020b; Ekberg, Grenness, and Hickson Citation2014; Grenness, Hickson, Laplante-Levesque, et al. Citation2015). A recent survey of audiologists’ knowledge, beliefs and practices suggests that the key barriers to the provision of emotional support are lack of skill, confidence, time, and uncertainty about scope of practice, and the lack of evidence for their value (Bennett et al. Citation2020c). Similar results were reported by van Leeuwen et al. (Citation2018). Counselling and emotional support skills have not previously been included and/or formalised in audiology training programs in Australia, and as such practicing clinical audiologists require upskilling in this area.

Two other highly rated themes were Promoting Client Responsibility (describing the process of making the client aware that rehabilitation outcomes are largely dependent on their active involvement and commitment to the rehabilitation process) and Client Empowerment (describing the process of helping clients discover personal strengths and capacities to take control of their lives). These themes tap into the concept of self-management. Health outcomes are improved when clients understand the importance of managing their own disorder (Schillinger et al. Citation2002), including the management of hearing loss (Convery et al. Citation2019; Linssen et al. Citation2013). Factors that influence hearing aid adoption and use include empowering the client (facilitated through conveying information in a way that matches the client’s health literacy), supporting the client’s responsibility and choices, employing shared decision making strategies, and encouraging skill development (Convery et al. Citation2019; Ferguson et al. Citation2016; Laplante-Lévesque, Hickson, and Worrall Citation2010; Laplante-Lévesque et al. Citation2012a; Poost-Foroosh et al. Citation2011). Audiologists often provide information and encourage skill development, but are less likely to engage the client in shared decision making or collaborative problem-solving (Barker, de Lusignan, and Cooke Citation2016). A number of clinical tools to help audiologists facilitate shared decision making and collaborative problem-solving have been developed (Hickson et al. Citation2016; Laplante-Lévesque, Hickson, and Worrall Citation2010; Pryce et al. Citation2018; van Leeuwen et al. Citation2020). However, many of these have not found their way to being clinically implemented and/or widely used. Some research suggests that audiologists value both audiometric results and clinical experience over client preferences to inform clinical decision making (Boisvert et al. Citation2017). This might be different if audiologists were trained to use a standardised tool or decision aid, assisting them in carrying out shared decision making, and addressing psychosocial concerns (van Leeuwen et al. Citation2018; Citation2019).

An important consideration when interpreting the results of the current study is that participants would have had varying degrees of familiarity with the individual approaches listed on the survey, which may have biased their rating scores. For example, a participant is unlikely to highly rate an approach of which they are unfamiliar. This phenomenon has been highlighted in the literature relating to group audiologic rehabilitation. In their chapter on the implementation of group audiological rehabilitation, Preminger and Nesbitt (Citation2014) described the importance of including both emotion- and problem-focussed coping strategy training; however, in marketing these classes they focussed only on the problem-focussed coping strategies by calling these “communication classes” because they believed that potential attendees would not understand the benefit of emotion-focussed coping strategies. Preminger and Nesbitt (Citation2014) noted specific comments from class attendees who reported that the benefit of the class was due to more than learning communication strategies, and described learning emotion-focussed coping strategies such as “not stressing” and “being more relaxed and not so bothered about the deafness”. Participants’ perceptions regarding cost/benefit of attendance improved after they were familiar with the sessions and the gains that were to be made by attending. This may also be true for participating audiologists in this study. The relatively low ranking approach relating to use of photographs to support client counselling is based on the photovoice approach, wherein clients’ share personal photos with their audiologist to facilitate communication, understand needs, and enhance audiological counselling (Saunders et al. Citation2019). Although photovoice is a well-regarded approach in psychology and social work, its concept is new to audiological practice and it is likely that few of the participants had any firsthand experience with this approach, thus potentially biasing their rating scores.

There is mounting evidence for the benefits of utilising family centred care (FCC) in audiology practices, that is, considering the needs of both clients and family members in any clinical exchange. The benefits of FCC include increased hearing aid adoption (Laplante-Levesque, Hickson, and Worrall Citation2010), a decrease in self-perceived hearing handicap when family members attend group audiologic rehabilitation classes (Preminger Citation2003), improved successful hearing aid use (Hickson et al. Citation2013), and hearing aid satisfaction (Singh, Lau, and Pichora-Fuller Citation2015). However, family member involvement is only occasionally observed in clinical practice (Ekberg et al. Citation2015). A recent study involving interviews of audiology clinical staff explored the barriers to implementing FCC approaches in audiology practice (Ekberg et al. Citation2020). Participants described barriers to include: insufficient knowledge regarding the principles of FCC; inadequate skills in how to initiate family member attendance; inconsistent training, confidence and resources to support the implementation of FCC; and organisational culture not supporting FCC (Ekberg et al. Citation2020). The results of the present study support these findings as participants placed greater importance on the perceived benefit of Including Communication Partners, than on their likelihood to use these approaches.

Clinical implications

Over the last two decades, research has increasingly attended to the psychosocial component of a biopsychosocial model, investigating the psychosocial issues associated with management of chronic health conditions. The psychosocial impacts of chronic health conditions are documented across a myriad of disciplines. For example clients living with chronic pain under the care of physiotherapists report being more distressed by the resulting psychosocial distress, such as worry, isolation, and anguish, than the chronic pain itself (Ojala et al. Citation2015). Recent studies show that allied health professionals may lack the skills, resources and support to integrate psychosocial support services into their daily clinical practices, including in physiotherapy (Driver et al. Citation2017), speech pathology (Sekhon, Douglas, and Rose Citation2015), and audiology (Bennett et al. Citation2020c; van Leeuwen et al. Citation2018). The current study provides further justification for the incorporation of psychosocial interventions training into audiology programs, and also as continued professional development opportunities for audiologists currently working in the field.

Limitations and future directions

This study has a number of limitations. First, participants self-selected for the study and thus the results may have been impacted by a sampling bias. Second, given that audiologists participating in this study also contributed to the generation of the survey items, it is possible that they may have been biased towards rating their own approaches more highly. Third, the approaches in the survey were generated by audiologists from across the world while the participating adults with hearing loss were recruited only from Australia, and so it is possible that not all participants would have been familiar with all approaches included in the survey. It is likely that participants’ familiarity and unfamiliarity with individual approaches influenced their ratings. This may have been adjusted for with the use of a “not familiar” option in the survey set. Fourth, the Australian sample might limit generalisability to patients of other Western countries. Nonetheless, while the results cannot be generalised to all older adults with hearing loss, the themes capture the shared lived experiences for a diverse group of participants and offer previously unreported perspectives. Fifth, participants were generally relatively positive about the approaches, and also about their “likelihood of use”. It is possible that both participant groups self-selected for this study due to an interest in the topic, thus skewing the results towards the positive. It is noteworthy that our items on likelihood of use for the audiologist may be reflections of their intentions of behaviour, and not behaviour itself. It is common to find an intention-behaviour gap for self-reported behaviours, and as such, use scores may in fact present a relatively positive picture of the actions they really take in their practices to address psychosocial needs (Carrington, Neville, and Whitwell Citation2014). This is likely the case for participating audiologists, as research has elucidated infrequent provision of psychosocial support in the audiology setting (Bennett et al. Citation2020b; Ekberg, Grenness, and Hickson Citation2014; Grenness, Hickson, Laplante-Levesque, et al. Citation2015). Finally, the direct comparisons between the two rating questions perceived benefit and likelihood of use should be considered with caution as these scales have not been psychometrically validated, and they include measurements of two different underlying constructs. Nonetheless, this exploratory study provides preliminary insight into those approaches that adults with hearing loss and audiologists value with respect to addressing the psychosocial needs of adults with hearing loss.

Conclusions

This study suggests that adults with hearing loss and audiologists recognise the importance of approaches that address the psychosocial impacts of hearing loss in audiological rehabilitation. However, they placed greater value on the internal-based approaches (the clients own emotional response, empowerment, and responsibility), and slightly less emphasis on the external-based approaches (being supported by communication partners, support groups or other health professionals).

TIJA-2020-08-0431-File009.docx

Download MS Word (27.7 KB)TIJA-2020-08-0431-File008.docx

Download MS Word (27.8 KB)TIJA-2020-08-0431-File007.docx

Download MS Word (28.2 KB)TIJA-2020-08-0431-File006.docx

Download MS Word (41.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Ear Science Institute Australia for assisting with participant recruitment and participants for their time.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. Barbra Timmer and Gurjit Singh are employed in research capacities by Sonova AG.

The authors thank Sonova AG, Switzerland for providing funding this project.

References

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. 2004. Scope of Practice in Audiology. https://www.asha.org/policy/SP2004-00192/#sec1.4

- Audiology Australia. 2013. Audiology Australia Professional Practice Standards – Part B Clinical Standards. http://www.audiology.asn.au/standards-downloads/Clinical%20Standards%20-%20whole%20document%20July13%201.pdf

- Barker, A. B., P. Leighton, and M. A. Ferguson. 2017. “Coping Together with Hearing Loss: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis of the Psychosocial Experiences of People with Hearing Loss and Their Communication Partners.” International Journal of Audiology 56 (5): 297–305. doi:10.1080/14992027.2017.1286695.

- Barker, F., S. de Lusignan, and D. Cooke. 2016. “Improving Collaborative Behaviour Planning in Adult Auditory Rehabilitation: Development of the I-PLAN Intervention Using the Behaviour Change Wheel.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 52 (6): 489–500.

- Beck, K., and J. Kulzer. 2018. “Teaching Counseling Microskills to Audiology Students: Recommendations from Professional Counseling Educators.” Seminars in Hearing 39 (01): 91–106.

- Bennett, R. J., C. Barr, J. Montano, R. H. Eikelboom, G. H. Saunders, M. Pronk, and J.E. Preminger, et al. 2020. “Identifying the Approaches used by Audiologists to Address the Psychosocial Needs of their Adult Clients.” International Journal of Audiology 1–11. doi:10.1080/14992027.2020.1817995

- Bennett, R. J., C. J. Meyer, B. Ryan, and R. H. Eikelboom. 2020b. “How Do Audiologists Respond to Symptoms of Mental Illness in the Audiological Setting? Three Case Vignettes.” Ear and Hearing. doi:10.1097/AUD.0000000000000887.

- Bennett, R. J., C. J. Meyer, B. Ryan, C. Barr, E. Laird, and R. H. Eikelboom. 2020c. “Knowledge, Beliefs and Practices of Australian Audiologists in Addressing the Psychological Needs of Adults with Hearing Loss.” American Journal of Audiology 29 (2): 129–142. doi:10.1044/2019_AJA-19-00087

- Boisvert, I., J. Clemesha, E. Lundmark, E. Crome, C. Barr, and C. M. McMahon. 2017. “Decision-Making in Audiology: Balancing Evidence-Based Practice and Patient-Centered Care.” Trends in Hearing 21. doi:10.1177/2331216517706397

- British Society of Audiology. 2016. Practice Guidance: Common Principles of Rehabilitation for Adults in Audiological Services. Bathgate, UK: British Society of Audiology.

- Cacioppo, J. T., and L. C. Hawkley. 2009. “Perceived Social Isolation and Cognition.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 13 (10): 447–454. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005.

- Cacioppo, J. T., L. C. Hawkley, G. G. Berntson, J. M. Ernst, A. C. Gibbs, R. Stickgold, and J. A. Hobson. 2002. “Do Lonely Days Invade the Nights? Potential Social Modulation of Sleep Efficiency.” Psychological Science 13 (4): 384–387. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00469.

- Carrington, M. J., B. A. Neville, and G. J. Whitwell. 2014. “Lost in Translation: Exploring the Ethical Consumer Intention–Behavior Gap.” Journal of Business Research 67 (1): 2759–2767. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.09.022.

- Convery, E., G. Keidser, L. Hickson, and C. Meyer. 2019. “The Relationship Between Hearing Loss Self-Management and Hearing Aid Benefit and Satisfaction.” American Journal of Audiology 28 (2): 274–284. doi:10.1044/2018_AJA-18-0130.

- Driver, C., B. Kean, F. Oprescu, and G. P. Lovell. 2017. “Knowledge, Behaviors, Attitudes and Beliefs of Physiotherapists Towards the Use of Psychological Interventions in Physiotherapy Practice: A Systematic Review.” Disability and Rehabilitation 39 (22): 2237–2249. doi:10.1080/09638288.2016.1223176.

- Ekberg, K., C. Grenness, and L. Hickson. 2014. “Addressing Patients' Psychosocial Concerns regarding Hearing Aids within Audiology Appointments for Older Adults.” American Journal of Audiology 23 (3): 337–350. doi:10.1044/2014_AJA-14-0011.

- Ekberg, K., C. Meyer, N. Scarinci, C. Grenness, and L. Hickson. 2015. “Family Member Involvement in Audiology Appointments with Older People with Hearing Impairment.” International Journal of Audiology 54 (2): 70–76. doi:10.3109/14992027.2014.948218

- Ekberg, K., S. Schuetz, B. Timmer, and L. Hickson. 2020. “Identifying Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing Family-Centred Care in Adult Audiology Practices: A COM-B Interview Study Exploring Staff Perspectives.” International Journal of Audiology 59 (6): 464–411. doi:10.1080/14992027.2020.1745305

- Ferguson, M. A., M. Brandreth, W. Brassington, P. Leighton, and H. Wharrad. 2016. “A Randomized Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Benefits of a Multimedia Educational Programme for First-Time Hearing Aid Users.” Ear and Hearing 27 (2): 123–136.

- Gliem, J. A., and R. R. Gliem. 2003. “Calculating, Interpreting, and Reporting Cronbach’s Alpha Reliability Coefficient for Likert-Type Scales.” Paper presented at the Ohio State University Conference, Ohio, USA. https://scholarworkos.iupui.edu/handle/1805/344

- Gow, A. J., A. Pattie, M. C. Whiteman, L. J. Whalley, and I. J. Deary. 2007. “Social Support and Successful Aging: Investigating the Relationships Between Lifetime Cognitive Change and Life Satisfaction.” Journal of Individual Differences 28 (3): 103–115. doi:10.1027/1614-0001.28.3.103.

- Grenness, C., L. Hickson, A. Laplante-Levesque, C. Meyer, and B. Davidson. 2015. “The Nature of Communication Throughout Diagnosis and Management Planning in Initial Audiologic Rehabilitation Consultations.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 26 (1): 36–50. doi:10.3766/jaaa.26.1.5.

- Grenness, C., L. Hickson, A. Laplante-Lévesque, C. Meyer, and B. Davidson. 2015. “The Nature of Communication Throughout Diagnosis and Management Planning in Initial Audiologic Rehabilitation Consultations.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 26 (1): 36–50. doi:10.3766/jaaa.26.1.5.

- Guerra-Zúñiga, M., F. Cardemil-Morales, N. Albertz-Arévalo, and M. Rahal-Espejo. 2014. “Explanations for the Non-Use of Hearing Aids in a Group of Older Adults. A Qualitative Study.” Acta Otorrinolaringologica (English Edition) 65 (1): 8–14. doi:10.1016/j.otoeng.2014.02.013.

- Hawkley, L. C., and J. T. Cacioppo. 2003. “Loneliness and Pathways to Disease.” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 17 (1): 98–105. doi:10.1016/S0889-1591(02)00073-9.

- Heffernan, E., N. S. Coulson, H. Henshaw, J. G. Barry, and M. A. Ferguson. 2016. “Understanding the Psychosocial Experiences of Adults with Mild-Moderate Hearing Loss: An Application of Leventhal’s Self-Regulatory Model.” International Journal of Audiology 55 (sup3): S3–S12. doi:10.3109/14992027.2015.1117663.

- Hickson, L., C. Lind, J. Preminger, B. Brose, R. Hauff, and J. Montano. 2016. “Family-Centered Audiology Care: Making Decisions and Setting Goals Together.” Hearing Review 23 (11): 14–19.

- Hickson, L., C. Meyer, K. Lovelock, M. Lampert, and A. Khan. 2013. “Factors Influencing Success with Hearing Aids in Older Adults.” International Journal of Audiology 49 (8): 586–595.

- Hickson, L., C. Meyer, K. Lovelock, M. Lampert, and A. Khan. 2014. “Factors Associated with Success with Hearing Aids in Older Adults.” International Journal of Audiology 53 (sup1): S18–S27. doi:10.3109/14992027.2013.860488.

- Howell, R. T., M. L. Kern, and S. Lyubomirsky. 2007. “Health Benefits: Meta-Analytically Determining the Impact of Well-Being on Objective Health Outcomes.” Health Psychology Review 1 (1): 83–136. doi:10.1080/17437190701492486.

- Jayakody, D. M., O. P. Almeida, C. P. Speelman, R. J. Bennett, T. C. Moyle, J. M. Yiannos, and P. L. Friedland. 2018. “Association Between Speech and High-Frequency Hearing Loss and Depression, Anxiety and Stress in Older Adults.” Maturitas 110: 86–91. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.02.002.

- Jennings, M. B., and L. Shaw. 2008. “Impact of Hearing Loss in the Workplace: Raising Questions about Partnerships with Professionals.” Work (Reading, Mass.) 30 (3): 289–295.

- Joachim, G. L., and S. Acorn. 2016. “Living with Chronic Illness: The Interface of Stigma and Normalization.” Canadian Journal of Nursing Research Archive 32 (3): 37–48.

- Kawachi, I., and L. F. Berkman. 2001. “Social Ties and Mental Health.” Journal of Urban Health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 78 (3): 458–467. doi:10.1093/jurban/78.3.458.

- Keidser, G., and M. Seeto. 2017. “The Influence of Social Interaction and Physical Health on the Association Between Hearing and Depression with Age and Gender.” Trends in Hearing 21. doi:10.1177/2331216517706395.

- Kharicha, K.,. S. Iliffe, D. Harari, C. Swift, G. Gillmann, and A. E. Stuck. 2007. “Health Risk Appraisal in Older People 1: Are Older People Living Alone an ‘at-Risk’group?” Brittish Journal of General Practice 57 (537): 271–276.

- Laird, E. C., R. J. Bennett, C. M. Barr, and C. A. Bryant. 2020. “Experiences of Hearing Loss and Audiological Rehabilitation for Older Adults With Comorbid Psychological Symptoms: A Qualitative Study.” American Journal of Audiology, 1–16. doi:10.1044/2020_AJA-19-00123

- Laplante-Lévesque, A., L. Hickson, and L. Worrall. 2010. “A Qualitative Study of Shared Decision Making in Rehabilitative Audiology.” Journal of the Academy of Rehabilitative Audiology 43: 27–43.

- Laplante-Levesque, A., L. Hickson, and L. Worrall. 2010. “Factors Influencing Rehabilitation Decisions of Adults with Acquired Hearing Impairment.” Internatinal Journal of Audiology 49 (7): 497–507. doi:10.3109/14992021003645902

- Laplante-Lévesque, A., L. D. Jensen, P. Dawes, and C. Nielsen. 2012a. “Optimal Hearing Aid Use: Focus Groups with Hearing Aid Clients and Audiologists.” Ear and Hearing 34 (2): 193–202.

- Laplante-Lévesque, A., L. V. Knudsen, J. E. Preminger, L. Jones, C. Nielsen, M. Öberg, T. Lunner, L. Hickson, G. Naylor, and S. E. Kramer. 2012b. “Hearing Help-Seeking and Rehabilitation: Perspectives of Adults with Hearing Impairment.” International Journal of Audiology 51 (2): 93–102. doi:10.3109/14992027.2011.606284.

- Lawrence, B. J., D. M. Jayakody, R. H. Eikelboom, R. J. Bennett, N. Gasson, and P. L. Friedland. 2018. “Age-Related Hearing Loss and Depression in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The Gerontologist 60 (3): e137–e154. doi:10.1093/geront/gnz009.

- Linssen, A. M., M. A. Joore, R. K. Minten, Y. D. van Leeuwen, and L. J. Anteunis. 2013. “Qualitative Interviews on the Beliefs and Feelings of Adults Towards Their Ownership, but Non-Use of Hearing Aids.” International Journal of Audiology 52 (10): 670–677. doi:10.3109/14992027.2013.808382.

- Locher, J. L., C. S. Ritchie, D. L. Roth, P. S. Baker, E. V. Bodner, and R. M. Allman. 2005. “Social Isolation, Support, and Capital and Nutritional Risk in an Older Sample: ethnic and Gender Differences.” Social Science & Medicine 60 (4): 747–761. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.023

- Mathers, C., A. Smith, and M. Concha. 2000. “Global Burden of Hearing Loss in the Year 2000.” Global Burden of Disease 18 (4): 1–30.

- McDade, T. W., L. C. Hawkley, and J. T. Cacioppo. 2006. “Psychosocial and Behavioral Predictors of Inflammation in Middle-Aged and Older Adults: The Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study.” Psychosomatic Medicine 68 (3): 376–381. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000221371.43607.64.

- Meibos, A., K. Muñoz, and M. Twohig. 2019. “Counseling Competencies in Audiology: A Modified Delphi Study.” American Journal of Audiology 28 (2): 285–299. doi:10.1044/2018_AJA-18-0141.

- Ojala, T., A. Häkkinen, J. Karppinen, K. Sipilä, T. Suutama, and A. Piirainen. 2015. “Chronic Pain Affects the Whole Person – A Phenomenological Study.” Disability and Rehabilitation 37 (4): 363–371. doi:10.3109/09638288.2014.923522.

- Poost-Foroosh, L., M. B. Jennings, L. Shaw, C. N. Meston, and M. F. Cheesman. 2011. “Factors in Client-Clinician Interaction That Influence Hearing Aid Adoption.” Trends in Amplification 15 (3): 127–139. doi:10.1177/1084713811430217.

- Preminger, J. E. 2003. “Should Significant Others Be Encouraged to Join Adult Group Audiologic Rehabilitation Classes?” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 14 (10): 545–555. doi:10.3766/jaaa.14.10.3.

- Preminger, J., and L. Nesbitt. 2014. “Group Audiologic Rehabilitation for Adults: Justification and Implementation.” In Adult Audiologic Rehabilitation, edited by J. J. Montano and J. B. Spitzer, 307–327. 2nd ed. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

- Pronk, M., D. J. H. Deeg, C. Smits, T. G. van Tilburg, D. J. Kuik, J. M. Festen, and S. E. Kramer. 2011. “Prospective Effects of Hearing Status on Loneliness and Depression in Older Adults- Identification of Subgroups.” International Journal of Audiology 50 (12): 887–896. doi:10.3109/14992027.2011.599871.

- Pryce, H., M. -A. Durand, A. Hall, R. Shaw, B. -A. Culhane, S. Swift, J. Straus, E. Marks, M. Ward, and K. Chilvers. 2018. “The Development of a Decision Aid for Tinnitus.” International Journal of Audiology 57 (9): 714–719. doi:10.1080/14992027.2018.1468093.

- Saunders, G. H., L. K. Dillard, M. T. Frederick, and S. C. Silverman. 2019. “Examining the Utility of Photovoice as an Audiological Counseling Tool.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 30 (5): 406–416. doi:10.3766/jaaa.18034.

- Schillinger, D., K. Grumbach, J. Piette, F. Wang, D. Osmond, C. Daher, J. Palacios, G. D. Sullivan, A. B. Bindman. 2002. “Association of Health Literacy with Diabetes Outcomes.” JAMA 288 (4): 475–482. doi:10.1001/jama.288.4.475

- Sekhon, J. K., J. Douglas, and M. L. Rose. 2015. “Current Australian Speech-Language Pathology Practice in Addressing Psychological Well-Being in People with Aphasia after Stroke.” International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 17 (3): 252–262. doi:10.3109/17549507.2015.1024170.

- Shiovitz-Ezra, S., and L. Ayalon. 2010. “Situational versus Chronic Loneliness as Risk Factors for All-Cause Mortality.” International Psychogeriatrics 22 (3): 455–462. doi:10.1017/S1041610209991426.

- Singh, G., and S. Launer. 2016. “Social Context and Hearing Aid Adoption.” Trends in Hearing 20. doi:10.1177/2331216516673833.

- Singh, G., L. Hickson, K. English, S. Scherpiet, U. Lemke, B. Timmer, and S. Launer. 2016. “Family-Centered Adult Audiologic Care: A Phonak Position Statement.” Hearing Review 23 (4): 16.

- Singh, G., S.-T. Lau, and M. K. Pichora-Fuller. 2015. “Social Support Predicts Hearing Aid Satisfaction.” Ear and Hearing 36 (6): 664–676. doi:10.1097/AUD.0000000000000182

- Southall, K., M. B. Jennings, J.-P. Gagné, and J. Young. 2019. “Reported Benefits of Peer Support Group Involvement by Adults with Hearing Loss.” International Journal of Audiology 58 (1): 29–36. doi:10.1080/14992027.2018.1519604.

- Trochim, W., and M. Kane. 2005. “Concept Mapping: An Introduction to Structured Conceptualization in Health Care.” International Journal for Quality in Health Care : Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care 17 (3): 187–191. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzi038.

- van Leeuwen, L. M., M. Pronk, P. Merkus, S. T. Goverts, J. R. Anema, and S. E. Kramer. 2019. “Developing an Intervention to Implement an ICF-Based e-Intake Tool in Clinical Otology and Audiology Practice.” International Journal of Audiology 59 (4): 282–300.

- van Leeuwen, L. M., M. Pronk, P. Merkus, S. T. Goverts, J. R. Anema, and S. E. Kramer. 2018. “Barriers to and Enablers of the Implementation of an ICF-Based Intake Tool in Clinical Otology and Audiology Practice-A Qualitative Pre-Implementation Study .” PLoS One 13 (12): e0208797. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208797.

- van Leeuwen, L. M., M. Pronk, P. Merkus, S. T. Goverts, C. B. Terwee, and S. E. Kramer. 2020. “Operationalization of the Brief ICF Core Set for Hearing Loss: An ICF-Based e-Intake Tool in Clinical Otology and Audiology Practice.” Ear and Hearing. doi:10.1097/AUD.0000000000000867.

- Vas, V., M. A. Akeroyd, and D. A. Hall. 2017. “A Data-Driven Synthesis of Research Evidence for Domains of Hearing Loss, as Reported by Adults with Hearing Loss and Their Communication Partners.” Trends in Hearing 21. doi:10.1177/2331216517734088

- Veiga, S. M., J. D. Alexandre, and F. Esteves. 2015. “Living with Hearing Loss: Psychosocial Impact and the Role of Social Support.” Journal of Otolaryngology-ENT Research 2 (5): 00036.

- Wilson, B. S., D. L. Tucci, M. H. Merson, and G. M. O'Donoghue. 2017. “Global Hearing Health Care: New Findings and Perspectives.” The Lancet 390 (10111): 2503–2515. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31073-5

- Wilson, R. S., K. R. Krueger, S. E. Arnold, J. A. Schneider, J. F. Kelly, L. L. Barnes, Y. Tang, and D. A. Bennett. 2007. “Loneliness and Risk of Alzheimer disease.” Arch Gen Psychiatry 64 (2): 234–240. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.234.