Abstract

Objective

To assess the benefits of the Ida Institute’s Why improve my hearing? Telecare Tool used before the initial hearing assessment appointment.

Design

A prospective, single-blind randomised clinical trial with two arms: (i) Why improve my hearing? Telecare Tool intervention, and (ii) standard care control.

Study sample

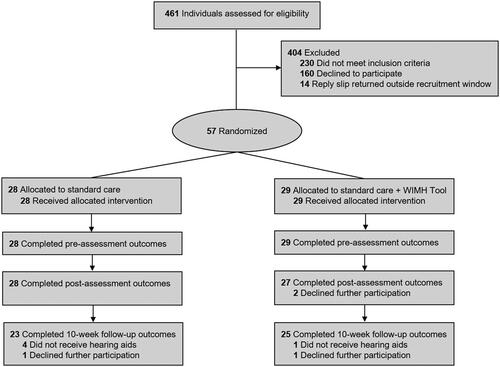

Adults with hearing loss were recruited from two Audiology Services within the United Kingdom’s publicly-funded National Health Service. Of 461 individuals assessed for eligibility, 57 were eligible to participate.

Results

Measure of Audiologic Rehabilitation Self-efficacy for Hearing Aids (primary outcome) scores did not differ between groups from baseline to post-assessment (Mean change [Δ]= −2.28; 95% confidence interval [CI]= −6.70, 2.15, p= .307) and 10-weeks follow-up (Mean Δ= −2.69; 95% CI= −9.52, 4.15, p = .434). However, Short Form Patient Activation Measure scores significantly improved in the intervention group compared to the control group from baseline to post-assessment (Mean Δ= −6.06, 95% CI= −11.31, −0.82, p = .024, ES= .61) and 10-weeks follow-up (Mean Δ= −9.87, 95% CI= −15.34, −4.40, p = .001, ES= −.97).

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that while a patient-centred telecare intervention completed before management decisions may not improve an individual’s self-efficacy to manage their hearing loss, it can lead to improvements in readiness.

Introduction

Adult aural rehabilitation typically involves an initial hearing assessment followed by the fitting of hearing aids (i.e. sensory management). Hearing aids have been shown to effectively improve listening abilities and quality of life in adults with hearing loss (Ferguson et al. Citation2017). Nevertheless, hearing aid take-up and adherence is low; it is estimated that two out of three adults who would benefit from hearing aids do not access them (Chia et al. Citation2007; Davis et al. Citation2007; Hartley et al. Citation2010). In addition, up to 24% of individuals with mild to moderate hearing loss who take-up hearing aids do not use them (Ferguson et al. Citation2017). Reasons for hearing aid non-use and suboptimal-use include poor attitudes towards and acceptance of hearing loss, low self-reported activity limitations and participation restrictions, reduced self-efficacy to manage hearing loss and use hearing aids, as well as a lack of financial and social support (Knudsen et al. Citation2010; Meyer and Hickson Citation2012; McCormack and Fortnum Citation2013; Bennett et al. Citation2018). Given that the factors influencing hearing aid take-up and adherence are diverse and multifaceted, it has been argued that a holistic, patient-centred approach to hearing healthcare should be adopted, as opposed to one that focuses solely on sensory management (Boothroyd Citation2007). As such, it is advocated that additional strategies, such as patient education, auditory-cognitive training, and counselling are also necessary to help individuals successfully manage their hearing loss (Boothroyd Citation2007; Davis et al. Citation2016; Ferguson et al. Citation2019).

For the individual, understanding their own motivations as to why it is important for them to seek help for and manage their hearing loss is one key strategy that can improve hearing aid take-up and adherence (Ridgeway, Hickson, and Lind Citation2015). Such an approach can be facilitated by motivational interviewing, which has been shown to be an effective, patient-centred method of counselling in the treatment and management of chronic health conditions (e.g. diabetes, asthma), as well as smoking cessation and drug abstinence (Rubak et al. Citation2005). According to Rubak et al. (Citation2005), motivational interviewing aims to elicit health behaviour change, particularly in patients who may be reluctant or ambivalent, through the identification of a patient’s intrinsic goals and encouraging them to consider the benefits and/or costs of engaging in the target behaviour. Importantly, motivational interviewing moves away from a practitioner-centred (or “paternalistic”) mode of care, facilitating collaboration between the healthcare provider and patient in treatment and management decisions. In the context of audiology, motivational interviewing has been successfully applied in adults living with hearing loss to facilitate patient-centred counselling and rehabilitation (Beck and Harvey Citation2009; Aazh Citation2015; Solheim et al. Citation2018). Furthermore, motivational interviewing is recognised by professional bodies as key to the provision of patient-centred care in the adult aural rehabilitation process (British Society of Audiology Citation2016; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Citation2018).

Despite these endorsements, patient-centred communication rarely occurs in audiology appointments (Grenness et al. Citation2015), which may be compounded by the absence of a “gold standard” approach to the implementation of patient-centeredness in audiological practice (Grenness et al. Citation2014). To address this, the Ida Institute developed an online Telecare platform to help people living with hearing loss better prepare for their audiology appointments. One of the included Telecare Tools is Why Improve My Hearing? (WIMH) that aims to promote readiness to address hearing loss and hearing aid self-efficacy before patients' first appointment. The WIMH Tool is derived from the Ida Institute’s Motivation Tools, which are intended to formally guide the audiologist to open a patient-centred dialogue during clinical appointments, so that they can provide more effective support that will encourage their patients to take action to manage their hearing loss successfully (Clark Citation2010). The Tools are based on the theoretical principles underlying the transtheoretical model of health behaviour change (Prochaska and DiClemente Citation1986), which posits six stages of health behaviour change: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance, and relapse. The transtheoretical model has been shown to have good construct, concurrent, and predictive validity in adults seeking help for their hearing loss for the first time (Laplante-Lévesque, Hickson, and Worrall Citation2013). Namely, Laplante-Lévesque, Hickson, and Worrall (Citation2013) assessed uptake and adherence of two hearing loss interventions (i.e. hearing aids and a communication program), showing that the majority of participants were initially in the action stage, with those in advanced stages of change being more likely to take-up and report greater success with their chosen intervention. Even so, Laplante-Lévesque, Hickson, and Worrall (Citation2013) also found that the stages of change did not predict adherence to the hearing intervention selected.

Existing evidence suggests that the Ida Institute’s Motivation Tools can be successfully incorporated into an audiology clinic structure (Ferguson et al. Citation2016; Ekberg and Barr Citation2020). Furthermore, compared to a standard care control group, Ferguson et al. (Citation2016) showed that first-time hearing aid users who used the Motivation Tools at the initial assessment appointment reported greater self-efficacy, reduced anxiety levels, and higher levels of shared decision-making. However, no significant group-differences were found for patients’ readiness to manage their hearing loss. A potential explanation for this latter finding is that the Motivation Tools were only assessed in patients who had already opted to receive hearing aids. Additionally, it has been shown that motivation, in terms of intention and action self-efficacy, to use hearing aids is high in adults who have already attended their first hearing assessment appointment (Sawyer et al. Citation2019). As such, the extent to which the Tools influence patient outcomes before initial attendance at an audiology clinic, and before decisions concerning hearing loss management have been made remains to be investigated.

The WIMH Tool specifically aims to encourage patients with hearing loss to reflect on their individual needs and perceived abilities before they come to clinic for the first-time so they can have more informed patient-centred discussions with their audiologist. Consequently, the objective of the current study was to examine the benefits of the WIMH Tool in adults with hearing loss who have not yet received hearing healthcare. A registered randomised controlled clinical trial assessed whether using the Tool before the initial hearing assessment appointment improves hearing aid self-efficacy and readiness to manage hearing loss. Based on the intended purpose of the Tool, as well as our previous feasibility study in first-time hearing aid users assessing the Motivation Tools (Ferguson et al. Citation2016), it was hypothesised that self-efficacy (primary measure) would improve in individuals using the Tool compared to a standard care control group. While our previous research found no group-differences for readiness (Ferguson et al. Citation2016), we speculate that this may have arisen because patients had already opted to receive hearing aids. Furthermore, given that self-efficacy and readiness have both been shown to be associated with hearing aid outcomes, such as use, benefit and satisfaction (Meyer and Hickson Citation2012; Meyer et al. Citation2014; Ferguson, Woolley, and Munro Citation2016; Bennett et al. Citation2018), we also evaluated the impact of the Tool 10-weeks post hearing aid fitting. In addition, in clinical trials accompanying qualitative studies can yield rich data that help the researcher to interpret the quantitative results, as well as explain the relevance of the trial findings to different audiences (O’Cathain et al. Citation2014). On this basis, to provide an in-depth understanding of user perspectives of implementing the WIMH Tool in audiological practice, an accompanying semi-structured interview study was completed with a sub-sample of patients and audiologists (Heffernan, Ferguson, and Maidment submitted).

Materials & methods

This study is reported in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidance (Moher et al. Citation2012).

Study population

Participants were recruited via Adult Audiology Services at Nottingham University Hospitals (NUH) National Health Service (NHS) Trust and Chesterfield Royal Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom (UK). Eligibility criteria were: (i) adults aged ≥18 years, (ii) good understanding of English, and (iii) had not previously worn hearing aids. Exclusion criteria were those who were unable to: (i) access the Internet and email via any compatible device, or (ii) complete questionnaires due to age-related problems (e.g. cognitive decline, dementia) confirmed from self- or familial-report.

Study design

The design was a prospective, two-centre, single-blind clinical randomised controlled clinical trial (RCT) with two arms: (i) the intervention group received the WIMH Tool plus standard clinical care, including hearing aids and counselling where appropriate, and (ii) the control group received standard clinical care only. Within the publicly-funded UK NHS, standard care consists of an initial, one-hour hearing assessment appointment. This appointment typically includes recording the patient’s medical history, pure-tone audiometry (air and bone conduction), and assessment of self-reported hearing and communication difficulties, such as via the Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) (Dillon, James, and Ginis Citation1997). The assessment results are discussed, and suitable management options considered, including hearing aids, non-technological based interventions (e.g. lipreading), and assistive listening devices (e.g. television streamer). If alternative options to hearing aids are decided, supplementary written information may be provided (e.g. leaflets directing patients to seek assistance from other services). The patient is then discharged from the audiology service and receives no further care, although they can return if, for example, their hearing deteriorates. If the patient decides to receive hearing aids, a one-hour fitting appointment is arranged. During the fitting appointment, hearing aids are fitted and verified using real-ear measurements (REMs), alongside counselling regarding their use and acclimatisation.

All patients referred to Nottingham and Chesterfield Adult Audiology Services for an initial hearing assessment by their family doctor across a seven-month period were posted a study information pack containing a reply sheet to return via post if they wished to participate. On receipt of this, the research coordinator confirmed eligibility via telephone and obtained informed consent. Post-consent, participants were allocated to one of the two groups. Allocation was undertaken by an independent researcher based in the NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre, who was not involved in any other aspect of the study, and randomly assigned eligible participants using Online Minimisation and Randomisation for Clinical Trials (OxMaR) software (O’Callaghan Citation2014). The randomisation schedule was stratified according to gender (male/female) and age (younger: <70 years; older: ≥70 years). Participants were assigned a unique identification number, so that study investigators responsible for data collection and analysis were blinded to treatment allocation.

Following randomisation, the research coordinator emailed the participant a web-link to complete the pre-assessment questionnaires via a secure online portal, which took approximately 45 minutes to complete. For both groups, the pre-assessment questionnaires were completed at least one day prior to the initial assessment appointment (M = 4.61; SD = 4.39). Participants assigned to the intervention group were also instructed to complete the WIMH Tool, which was returned at least one day prior to the initial hearing assessment appointment (M = 3.21; SD = 3.38).

During the initial hearing assessment, those assigned to the intervention group discussed their completed WIMH Tool with an audiologist. It was decided by the study team that the Tool should be discussed immediately after the pure-tone audiometry test results were discussed. Following the hearing assessment appointment, the research coordinator sent participants the online post-assessment questionnaires, which were completed within approximately four days (M = 4.21; SD = 4.50). For participants who opted to receive hearing aids, a hearing aid fitting appointment was arranged approximately four weeks later (M = 3.64; SD = 2.42) and online follow-up questionnaires were completed approximately 10-weeks (M = 10.69; SD = .91) post-fitting.

At the end of the trial, all participants were fully debriefed and informed that they could access all Telecare Tools via the Ida Institute's website. A sub-sample of participants in the intervention group (N = 10) and trained audiologists (N = 5) also completed a one-to-one, semi-structured interview to examine their perceptions of and experiences with the WIMH Tool. This qualitative study is reported separately in an accompanying paper (Heffernan, Ferguson, and Maidment Citation2022).

The study was approved by the UK NHS Health Research Authority, South Central - Oxford C Research Ethics Committee and Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust Research and Innovation department. The trial was registered on 30 October 2017 on the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ISRCTN11296341).

Study interventions

The Why improve My Hearing (WIMH) telecare tool

The Tool (https://apps.idainstitute.com/apps/wimh_en) encourages an individual to reflect on how improved hearing and communication would affect their everyday life before their initial assessment appointment at audiology. First, the individual is asked to select an image, or upload their own, that depicts a situation where they experience hearing difficulty (e.g. busy restaurant, family gathering). Second, they are asked “How important is it for you to improve your hearing?”, which aims to help the individual assess their readiness to address their hearing loss in the prespecified situation by selecting a number on an unmarked visual analogue scale between one (not important) and 10 (of highest importance). Third, the Tool asks, “What would happen if you get a hearing aid to improve your hearing right now?”. Based on discussions with the developers of the WIMH Tool at the Ida Institute, this question aims to promote self-efficacy through imaginal experience (Maddux Citation2009), whereby the patient generates personal efficacy beliefs by visualising themselves using a hearing aid to improve their hearing in the listening situation they have selected. This process can be repeated for additional situations. On completion, the Tool can be printed by the user and/or submitted to a specified email address.

Hearing aids

For patients who opted to receive hearing aids, Oticon Zest or Phonak Nathos devices were programmed using the NAL-NL2 algorithm and verified by REMs in accordance with local protocols and national guidelines (British Society of Audiology Citation2011). Hearing aids were fitted with either custom earmolds or open-fit slim tubes.

Study measures

Audiological measures

During the initial hearing assessment appointment, pure-tone air conduction thresholds were measured at octave frequencies (.25–8 kHz) for each ear, and bone-conduction thresholds as required (.5–4 kHz), following the procedures recommended by the British Society of Audiology (Citation2011).

Outcome measures

Patient-reported outcome measures were completed online before (pre-assessment) and immediately after (post-assessment) the initial hearing assessment appointment, as well as 10-weeks post-hearing aid fitting (follow-up), unless otherwise specified.

Self-efficacy

Measure of Audiologic Rehabilitation Self-efficacy for Hearing Aids (MARS-HA) (West and Smith Citation2007). A 24-item measure of self-efficacy for hearing aids with four subscales: basic handling (e.g. I can insert a battery into a hearing aid with ease), advanced handling (e.g. I can identify the different components of my hearing aid), adjustment (e.g. I could get used to the sound quality of hearing aids), and aided listening skills (e.g. I could understand a one-on-one conversation in a noisy place if I wore hearing aids). Respondents indicated how certain they were that they could perform the tasks described on an 11-point scale (0%= Cannot do this, 100%= Certain I can do this). This measure served as the primary outcome in the trial.

Readiness

Short Form Patient Activation Measure (PAM) (Hibbard et al. 2005). A 13-item questionnaire assessing knowledge, skills, and confidence of patients to manage their health or chronic condition. Respondents indicated how much each statement applied to them on a four-point scale (0= Disagree strongly, 3= Agree strongly). Summed raw scores were converted into a continuous activation score between 0 (no activation) and 100 (high activation). An improvement in four points is considered a minimal clinically important difference (Hibbard and Tusler Citation2007; Fowles et al. Citation2009; Hibbard Citation2009). Activation scores can also be categorised in accordance with one of four Activation Levels, each of which map onto aspects of readiness for change specified in the transtheoretical model (Prochaska and DiClemente Citation1986): (i) Disengaged, may not yet believe that the patient role is important (≤47.0); (ii) Lacks confidence and knowledge to take action (47.1–55.1); (iii) Beginning to take action (55.2–67.0); and (iv) Adopted new behaviours but may have difficulty maintaining them in times of stress or change (≥67.1). This measure was administered in its original, validated, and licenced form, which has been used previously as an outcome of readiness in the assessment of multiple health-related interventions, including hearing loss (Ferguson et al. Citation2016; Kearns et al. Citation2020).

Stages of Readiness questionnaire (Babeu, Kricos, and Lesner Citation2004). A single item measure of readiness to obtain and use hearing aids that is scored on a five-point scale (1= I am not ready for hearing aids at this time, 5= I am comfortable with the idea of wearing hearing aids), which correspond to stages of change specified in the transtheoretical model (Prochaska and DiClemente Citation1986). Completed at pre- and post-assessment only.

Disability (activity limitations) and handicap (participation restrictions)

Glasgow Hearing Aid Benefit Profile (GHABP) (Gatehouse Citation1999). Assessed hearing disability (activity limitations) and handicap (participation restrictions) (part I), as well as hearing aid use, benefit, residual disability, and satisfaction (part II) across four pre-defined situations. Each subscale is accompanied by a five-point scale, and the mean score across the situations is converted into a percentage. Part I was completed at pre- and post-assessment. Part II was completed at the 10-week follow-up. In this study, we opted to only administer the pre-defined situations, given that the questionnaire was self-administered. In addition, this shortened version of the original questionnaire has been used when investigating proposed norms (Whitmer, Howell, and Akeroyd Citation2014).

Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE) (Ventry and Weinstein Citation1982). A 25-item questionnaire assessing the emotional (13 items) and social/situational (12 items) impact of hearing loss on older people, scored using a three-point scale (4= Yes; 2= Sometimes; 0= No), with higher scores indicating greater handicap (participation restrictions). At pre- and post-assessment, participants responded unaided, whereas at the 10-week follow-up they responded aided.

Social Participation Restrictions Questionnaire (SPaRQ) (Heffernan et al. Citation2019). A 19-item questionnaire assessing social behaviours (9-items) and social perceptions (10-items) in adults with hearing loss. Each item is measured on an 11-point response scale (0= Completely disagree, 10= Completely agree) with higher scores indicating greater participation restrictions. It is recommended that for the social perceptions subscale, items six and seven should be re-scored post-hoc so that they have a seven-point scale, with a maximum score of 92. In addition, a total score should only be calculated for each subscale, but not for the SPaRQ as a whole, as each subscale measures a distinct and unidimensional aspect of participation restrictions.

Hearing aid outcomes

Expected Consequences of Hearing aid Ownership (ECHO) (Cox and Alexander Citation2000). A 15-item questionnaire assessing hearing aid expectations in terms of positive effect, service and cost, negative features, and personal image. Question 14 (The cost of my hearing aids(s) will be reasonable) was omitted since hearing aids are provided free of charge by the UK NHS. Each item is scored using a seven-point scale, from Not at all (one-point) to Tremendously (seven-points), where a high score indicates high expectations. Questions two, four, seven and 13 are reversed scored prior to calculating the total and mean scores for each subscale. Completed at pre- and post-assessment only.

Audiology Outpatient Survey (AOS) (Ferguson et al. Citation2016). Consisting of nine items used to routinely evaluate the patient’s experience of patient-centred care within NHS Adult Audiology Services (Supplementary Materials). Answers were given on a three-point scale (0% = No, 50% = Yes, to some extent, 100% = Yes, definitely). Completed immediately post-assessment only.

Satisfaction with Amplification in Daily Life (SADL) (Cox and Alexander Citation1999). A 15-item measure of satisfaction with hearing aids in terms of positive effect, service and cost, negative features, and personal image. Question 14 (Does the cost of your hearing aids(s) seem reasonable to you?) was omitted, since hearing aids were provided free of charge. Each item is scored using a seven-point scale, from Not at all (one-point) to Tremendously (seven-points), where a high score indicates high satisfaction. Questions two, four, seven and 13 are reversed scored prior to calculating the total and mean scores for each subscale. Completed at the 10-week follow-up only.

Sample size and data analysis

To detect a 10% change in MARS-HA overall scores (i.e. the smallest possible change) with a two-tailed alpha (α) of .05 and a power (1−β) of .80, we estimated that 50 participants (n = 25 in each arm) would be needed to detect a significant difference between groups. In accordance with the CONSORT guidance (Moher et al. Citation2012), significance testing of baseline differences between groups were not performed. Furthermore, no interim analyses were undertaken. Intention-to-treat analyses, using the last observation carried forward, were conducted to assess change over time for primary and secondary outcome measures completed at pre-assessment, post-assessment, and 10-week follow-up.

For each outcome measure, univariate generalised linear model (GLM) analyses were performed with group as the fixed factor. Change score (or change from baseline) was the dependent variable, where a single measurement was created for each participant by subtracting the post-intervention or 10-week follow-up measurement from the pre-assessment (i.e. baseline) measurement. For outcome measures obtained at the post-assessment (AOS) and 10-week follow-up (GHABP part II, SADL) only, the difference between groups was examined using independent t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests. Effect sizes (ES) (Cohen Citation1988) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for within-group and between-group differences are reported, where ES are classed as small (0.2), moderate (0.5), and large (0.8), and positive or negative sign indicating whether the effect increases or decreases the mean, respectively. Bonferroni correction to account for multiple comparisons was applied for each outcome measure and adjusted p-values reported. Significance was set to p ≤ .05.

Deviation from published trial registration

We had pre-specified that hearing aid use, as measured via datalogging, would also be collected at the 10-week follow-up. However, to reduce patient burden, outcomes across all time-points were administered remotely online.

Results

Study population

Eligible participants were recruited and randomised between 8 November 2017 and 11 June 2018. In total, 461 individuals were assessed for eligibility, with 57 being willing and eligible to take part. Four-hundred and four patients (87.6%) did not wish to take part in the trial for the following reasons: 160 declined to participate, citing that they were not interested in taking part in research (n = 55), lacked time (n = 73), experienced ill-health (n = 25), or were not confident using the Internet (n = 7). A further 230 (49%) patients were excluded for the following reasons: they did not understand English (n = 1), were currently using hearing aids (n = 48), had no access to the Internet and/or email (n = 118), were unable to provide informed consent (n = 3), or the reply slip was received after patients had attended their initial hearing assessment appointment (n = 60). Demographic and clinical characteristics did not statistically differ between the control and intervention groups (p ≥ .118) (). Overall, the mean age was 67.73 years (SD = 9.46), 19 (33.3%) were female, 38 (66.7%) were employed, and most rated their computer skill level as “competent” (n = 44, 77.2%) on a validated scale (Henshaw et al. Citation2012).

Table 1. Mean baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by group.

Attrition

provides a CONSORT flow diagram showing progression of participants through each phase of the trial. As shown, all participants completed the pre-assessment outcomes and all participants randomised to the intervention group returned the WIMH Tool prior to their hearing assessment appointment. After the initial hearing assessment, two participants in the intervention group did not complete the post-assessment outcomes, citing that they no longer had time to continue participation in the trial. A further seven participants did not complete the 10-week follow-up outcomes, of which five participants opted not to receive hearing aids (intervention group: n = 1; control group: n = 4) due to a combination of audiological and motivational factors. The proportion of participants who opted to receive hearing aids did not differ statistically between groups (p= .148). Two participants (intervention group: n = 1; control group: n = 1) declined to participate further (no reason given). In addition, due to an unforeseen technical issue, data for eight participants (intervention group: n = 4; control group: n = 4) were unavailable for the Stages of Readiness questionnaire at both pre- and post-assessment.

Change in patient-reported outcome measures

Pre- to post-assessment

MARS-HA (i.e. self-efficacy) scores improved in the WIMH Tool intervention group compared to the standard care control group (), although group-differences were not statistically significant (p ≥ .076). However, PAM (i.e. readiness) scores improved significantly in the intervention group compared to the standard care control group by an average of 6.06% (95% CI = .82–11.31; p = .024; ES = .61). Scores on the GHABP disability (i.e. activity limitations) subscale significantly decreased (i.e. improved) in the control group but increased (i.e. worsened) in the intervention group; average difference in change of 8.93% (95% CI = −15.44 to −2.42, p = .008; ES = −0.73). Similarly, HHIE social/situational subscale scores significantly decreased (i.e. improved) in the control group compared to the intervention group by an average of 2.94 (95% CI = −5.86 to −.02, p = .049; ES = −.53). For all remaining outcome measures, there were no significant differences between groups (p ≥ .064) (). In addition, AOS responses for each question did not differ significantly between groups (p ≥ .756) (Supplementary Materials).

Table 2. Mean change from pre- to post-assessment and difference between control and WIMH Telecare Tool intervention groups for all outcome measures.

Pre-assessment to 10-weeks follow-up

For MARS-HA scores, group-differences were not statistically significant (p ≥ .180) (). By comparison, PAM scores improved significantly in the intervention compared to the standard care control group by an average of 9.87% (95% CI = −15.34 to −4.40; p = .001; ES = −.97). For all remaining outcome measures, there were no significant differences between groups (p ≥ .116).

Table 3. Mean change from pre-assessment to 10-weeks follow-up and between control and WIMH Telecare Tool intervention groups for all outcome measures.

Post-assessment to 10-weeks follow-up

For all outcome measures, there were no significant differences between groups (p≥ .142) (see Supplementary Materials). In addition, the GHABP part II and SADL scores did not differ significantly between groups (p≥ .775) (see Supplementary Materials).

Discussion

This trial evaluated the extent to which an online telehealth intervention can influence patient’s self-efficacy and readiness when used before initial attendance at an audiology clinic, and before aural rehabilitation decisions have been made. In addition, given that self-efficacy and readiness have been shown to be associated with hearing aid use, benefit, and satisfaction (Meyer and Hickson Citation2012; Meyer et al. Citation2014; Ferguson, Woolley, and Munro Citation2016; Bennett et al. Citation2018), we also assessed the impact of the intervention 10-weeks post-fitting.

Against our initial hypotheses, changes in self-efficacy (primary outcome) did not differ between groups. Self-efficacy is a domain-specific construct that refers to one’s belief in one’s ability to execute a particular course of action (West and Smith Citation2007; Smith et al. Citation2011; Jennings, Cheesman, and Laplante-Lévesque Citation2014). In our previous study assessing the Ida Institute’s Motivation Tools, of which the WIMH Tool is a derivative, self-efficacy was shown to improve following the intervention compared to the control group when measured at the initial hearing assessment appointment (Ferguson et al. Citation2016). There are several potential explanations for why the latter study found differences in self-efficacy, whereas the current study did not. Firstly, three separate Motivation Tools were assessed by Ferguson et al. (Citation2016): (i) The Line consists of two questions (How important is it for you to improve your hearing right now? and How much do you believe in your ability to use a hearing aid?) that aim to help patients assess readiness to improve their hearing and self-efficacy for hearing aids, respectively; (ii) The Box requires the patient to consider the benefits and costs of taking no action versus taking action; and (iii) The Circle provides a visual representation of patients’ readiness to receive hearing care recommendations. It could be speculated that self-efficacy may have improved in Ferguson et al.'s (Citation2016) study because a combination of Tools was employed that address multiple routes to self-efficacy (e.g. imaginal and vicarious experiences). Secondly, we have argued that the WIMH Tool aims to promote self-efficacy through imaginal experience (Maddux Citation2009), whereby the patient is required to visualise themselves using a hearing aid to improve their hearing. Subsequently, self-efficacy was assessed using the validated MARS-HA (West and Smith Citation2007), which encompasses basic handling, advanced handling, adjustment, and aided listening skills. In comparison, Ferguson et al. (Citation2016) required patients to reflect on and discuss with an audiologist their perceived ability to use a hearing aid, assessing self-efficacy via a single item from the Hearing Health Care Intervention Readiness questionnaire (Weinstein Citation2012). As such, there may be key differences in how self-efficacy was conceptualised and/or measured between studies.

A further alternative explanation for why the current trial showed no group-differences in self-efficacy could be attributed to the characteristics of the study sample. Namely, all participants had the necessary skills and knowledge to use digital technologies, given that this was a prerequisite to taking part in the trial. In support, it has been shown that greater digital competency in first-time hearing aid users predicts superior practical hearing aid handling skills, as well as knowledge of hearing aids and communication, which may arise due to greater self-efficacy (Maidment et al. Citation2016).

In addition to self-efficacy, we also measured patients’ readiness to manage hearing loss. While our previous research assessing the Motivation Tools found no group-differences in this domain (Ferguson et al. Citation2016), outcomes in this earlier study were assessed in patients who had already agreed to accept hearing aids. Furthermore, motivation to use hearing aids has also been shown to be high in adults who have already attended their first hearing assessment appointment (Sawyer et al. Citation2019). Therefore, in the current trial we evaluated whether the WIMH Tool would increase readiness for change when used before participants had attended the clinic for the first time and before management decisions had been made. We found that, in the intervention group, patients’ readiness significantly improved from pre-assessment to both post-assessment and 10-weeks follow-up, with moderate and large clinical effect sizes, respectively. A potential explanation for improved readiness can be derived from the accompanying semi-structured interview study, which qualitatively examined the experiences of patients and audiologists towards using the WIMH Tool in audiological practice (Heffernan, Ferguson, and Maidment Citation2022). Both patients and audiologists reported that the Tool helped patients to take an active role in the decision-making processes during the appointment. In addition, patients reported that the Tool helped them to realise and accept before they cam to the clinic that they had a hearing difficulty that might benefit from intervention.

Furthermore, although not hypothesised, self-reported activity limitations and participation restrictions increased (i.e. worsened) from pre- to post-assessment for the intervention group but reduced (i.e. improved) for the standard care control group. It is possible that greater awareness of hearing difficulties due to completing the Tool likely led to increased readiness to change in patients in the intervention group. In support, greater activity limitations and participation restrictions have been shown to be associated with being in a more advanced stage of readiness (Laplante-Lévesque, Hickson, and Worrall Citation2013; Ferguson et al. Citation2016), as well as increasing the likelihood that an individual will seek help for their hearing loss and take-up hearing aids (Knudsen et al. Citation2010; Meyer and Hickson Citation2012; McCormack and Fortnum Citation2013). Thus, our findings are consistent with previous literature showing that perceived readiness to take action and improve hearing difficulties is associated with hearing intervention outcomes (Laplante-Lévesque, Hickson, and Worrall Citation2012; Citation2013; Ridgeway, Hickson, and Lind Citation2015).

Nevertheless, the WIMH Tool did not confer benefits for hearing aid outcomes (e.g. benefit, satisfaction, residual disability) assessed 10-weeks post hearing aid fitting, which replicates our previous study of the Motivation Tools (Ferguson et al. Citation2016). While self-reported activity limitations and participation restrictions reduced for both groups from pre- and post-assessment to 10-weeks follow-up, these outcomes did not differ statistically between groups at each time point. A possible explanation for why no differences were found between groups for these outcomes is that the WIMH Tool is primarily designed to prepare patients prior to their initial appointment. That is, the WIMH Tool specifically assists patients in coming to accept and understand their hearing difficulties, which increases their readiness and motivation to take-up hearing aids. Further support for this comes from our accompanying semi-structured interview study, whereby patients and audiologists reported that the Tool improved patients’ preparation for the assessment appointment, enriched patient-audiologist interactions during the appointment, and increased patient readiness to manage their hearing loss (Heffernan, Ferguson, and Maidment Citation2022). However, the audiologists interviewed also reported that the Tool may have an indirect or minimal influence on longer-term hearing aid outcomes, such as use, benefit and satisfaction, as other factors relating to the patient (e.g. motivation) and the audiologist (e.g. how hearing aids are fitted and subsequent counselling) may exert a greater influence. Although not discussed during the interviews, additional factors, such as social support and positive attitudes to hearing aids, have also been shown to have an impact on hearing aid outcomes (Knudsen et al. Citation2010; Hickson et al. Citation2014). Even so, it has been argued that it may be more appropriate to evaluate patient-centred interventions, such as the WIMH Tool, based on proximal outcomes, including the patient feeling respected, understood, and/or involved during clinical appointments, which have their own merits (Epstein and Street Citation2011).

Limitations, generalisability, and future research

Although the study investigators were blinded to participants’ treatment allocation, patients could not be blinded to the intervention. This could be addressed by including an active control group, such as the completion of an online exercise unrelated to hearing loss. In addition, the generalisability of our findings may also be restricted. For example, since the WIMH Tool and self-reported outcome measures were all delivered online, participants required internet access to participate in the study. Consequently, the sample’s likely higher level of digital competency may not be truly representative of a typical hearing loss population. In future studies, potential sampling biases attributed to digital competency could be addressed through the provision of an “offline” version of the Tool. Even so, internet use in older adults continues to rise, increasing from 42% in 2011 to 71% in 2019 (Office for National Statistics Citation2019), and this increase in use has become even more marked since the COVID-19 pandemic (Saunders and Roughley Citation2020; Swanepoel and Hall Citation2020; Ferguson et al. Citation2021). Thus, it is anticipated that, over time, digital competency will become less of a concern when assessing hearing interventions delivered via telehealth platforms in this population.

Additionally, the WIMH Tool was delivered exclusively within the publicly-funded UK NHS. As a result, the extent to which the impact of the Tool generalises to other hearing healthcare systems that incur out-of-pocket costs to the patient should be evaluated. It should also be noted that, while participants in the current study had not yet attended their first audiology appointment, they all required an onward referral from their family docotr, or General Practitioner. Consequently, all participants had already engaged in some help-seeking and, therefore, may have been ready to take action to manage their hearing loss. Future research could address this potential confound through the identification of individuals who have yet to seek help for their hearing loss and are in earlier stages of readiness, such as via a remotely delivered hearing screening test. In a recent study assessing help-seeking behaviour in people failing a smartphone application-based hearing screening test, a combination of factors, including beliefs about hearing loss, age, and stage of change, were all found to influence the likelihood individuals will seek further audiological care (Schönborn et al. Citation2020).

Conclusions

This is the first study to assess the clinical effectiveness of a remotely delivered, online telecare intervention before initial attendance at an audiology clinic, and before hearing loss management decisions have been made. Overall, our results suggest that, when used prior to a hearing assessment appointment, the WIMH Tool does not improve hearing aid self-efficacy, the primary outcome in this study, or hearing aid outcomes up to 10-weeks post-fitting. Despite this, the Tool appears to have the potential to improve patient readiness, helping patients who are ambivalent or reluctant to accept that they have hearing difficulties that require intervention and/or present with lower readiness to change.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (25.7 KB)Acknowledgments

This trial was prospectively registered in the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN11296341. The data that support the findings of this study are openly available online in Loughborough University’s Research Repository, https://repository.lboro.ac.uk/s/036fb36413a4bbfff084. The authors would like to thank the Ida Institute for funding this study. We would also like to thank Daljit Mehton for coordinating the study, Krysta Siliris for randomly allocating participants, Naomi Russell for training audiologists to use the WIMH Tool, and the patients and audiologists at Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust and Chesterfield Royal Hospital NHS Foundation Trust who took part in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aazh, H. 2015. “Feasibility of Conducting a Randomized Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Effect of Motivational Interviewing on Hearing-Aid Use.” International Journal of Audiology 2: 1–9.

- Babeu, L. A., P. B. Kricos, and S. A. Lesner. 2004. “Application of the Stages-of-Change Model in Audiology.” The Journal of the Academy of Rehabilitative Audiology 37: 41–56.

- Beck, D. L., and M. A. Harvey. 2009. “Creating Successful Professional-Patient Relationships.” Audiology Today 21: 36–47.

- Bennett, R. J., A. Laplante-Lévesque, C. J. Meyer, and R. H. Eikelboom. 2018. “Exploring Hearing Aid Problems: Perspectives of Hearing Aid Owners and Clinicians.” Ear and Hearing 39 (1): 172–187. doi:10.1097/AUD.0000000000000477.

- Boothroyd, A. 2007. “Adult Aural Rehabilitation: What Is It and Does It Work?” Trends in Amplification 11 (2): 63–71. doi:10.1177/1084713807301073.

- British Society of Audiology. 2011. “Recommended Procedure: Pure-Tone Air-Conduction and Bone-Conduction Threshold Audiometry With and Without Masking.” Retrieved from http://www.thebsa.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/BSA_RP_PTA_FINAL_24Sept11_MinorAmend06Feb12.pdf

- British Society of Audiology. 2016. “Practice Guidance: Common Principles of Rehabilitation for Adults in Audiology Services.” http://www.thebsa.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Practice-Guidance-Common-Principles-of-Rehabilitation-for-Adults-in-Audiology-Services-2016.pdf

- Chia, Ee-Munn, Jie Jin Wang, Elena Rochtchina, Robert R. Cumming, Philip Newall, and Paul Mitchell. 2007. “Hearing Impairment and Health-Related Quality of Life: The Blue Mountains Hearing Study.” Ear and Hearing 28 (2): 187–195. doi:10.1097/AUD.0b013e31803126b6.

- Clark, J. 2010. “The Geometry of Patient Motivation: Circles, Lines, and Boxes.” Audiology Today 22: 32–40.

- Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

- Cox, R. M., and G. C. Alexander. 1999. “Measuring Satisfaction With Amplification in Daily Life: The SADL Scale.” Ear and Hearing 20 (4): 306–320. doi:10.1097/00003446-199908000-00004.

- Cox, R. M., and G. C. Alexander. 2000. “Expectations About Hearing Aids and Their Relationship to Fitting Outcome.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 11 (7): 368–382.

- Davis, Adrian, Catherine M. McMahon, Kathleen M. Pichora-Fuller, Shirley Russ, Frank Lin, Bolajoko O. Olusanya, Shelly Chadha, et al. 2016. “Aging and Hearing Health: The Life-Course Approach.” The Gerontologist 56 (Suppl 2): S256–S267. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw033.

- Davis, A., P. Smith, M. Ferguson, D. Stephens, and I. Gianopoulos. 2007. “Acceptability, Benefit and Costs of Early Screening for Hearing Disability: A Study of Potential Screening Tests and Models.” Health Technology Assessment 11 (42): 1–294. doi:10.3310/hta11420.

- Dillon, H., A. James, and J. Ginis. 1997. “Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) and Its Relationship to Several Other Measures of Benefit and Satisfaction Provided by Hearing Aids.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 8 (1): 27–43.

- Ekberg, K., and C. Barr. 2020. “Identifying Clients’ Readiness for Hearing Rehabilitation Within Initial Audiology Appointments: A Pilot Intervention Study.” International Journal of Audiology 59 (8): 606–614. doi:10.1080/14992027.2020.1737885.

- Epstein, R. M., and R. L. Street. 2011. “The Values and Value of Patient-Centered Care.” The Annals of Family Medicine 9: 100–103.

- Ferguson, Melanie A., Pádraig T. Kitterick, Lee Yee Chong, Mark Edmondson-Jones, Fiona Barker, and Derek J. Hoare. 2017. “Hearing Aids for Mild to Moderate Hearing Loss in Adults.” The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 9: CD012023. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012023.pub2.

- Ferguson, M. A., D. Maidment, H. Henshaw, and E. Heffernan. 2019. “Evidence-Based Interventions for Adult Auditory Rehabilitation: That Was Then, This is Now.” Seminars in Hearing 40 (1): 68–84.

- Ferguson, M. A., D. W. Maidment, R. Gomez, N. C. Coulson, and H. Wharrad. 2021. “The Feasibility of an m-Health Educational Programme (m2Hear) to Improve Outcomes in First-Time Hearing Aid Users.” International Journal of Audiology 60 (sup1): S30–S41.

- Ferguson, M. A., D. W. Maidment, N. Russell, M. Gregory, and N. R. Nicholson. 2016. “Motivational Engagement in First-Time Hearing Aid Users: A Feasibility Study.” International Journal of Audiology 3: S34–S41.

- Ferguson, M. A., A. Woolley, and K. J. Munro. 2016. “The Impact of Self-Efficacy, Expectations and Readiness on Hearing Aid Outcomes.” International Journal of Audiology 55 (sup3): S34–S41. doi:10.1080/14992027.2016.1177214.

- Fowles, Jinnet Briggs, Paul Terry, Min Xi, Judith Hibbard, Christine Taddy Bloom, and Lisa Harvey. 2009. “Measuring Self-Management of Patients’ and Employees’ Health: Further Validation of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) Based on Its Relation to Employee Characteristics.” Patient Education and Counseling 77 (1): 116–122. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.02.018.

- Gatehouse, S. 1999. “Glasgow Hearing Aid Benefit Profile: Derivation and Validation of Client-Centred Outcome Measures for Hearing Aid Services.” The Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 10: 80–103.

- Grenness, C., L. Hickson, A. Laplante-Levesque, and B. Davidson. 2014. “Patient-Centred Care: A Review for Rehabilitative Audiologists.” International Journal of Audiology 52: 1–8.

- Grenness, C., L. Hickson, A. Laplante-Lévesque, C. Meyer, and B. Davidson. 2015. “The Nature of Communication Throughout Diagnosis and Management Planning in Initial Audiologic Rehabilitation Consultations.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 26 (1): 36–50. doi:10.3766/jaaa.26.1.5.

- Hartley, D., E. Rochtchina, P. Newall, M. Golding, and P. Mitchell. 2010. “Use of Hearing Aids and Assistive Listening Devices in an Older Austrailian Population.” Journal of the Academy of Audiology 21: 642–653.

- Heffernan, E., M. A. Ferguson, and D. W. Maidment. 2022. “Assessing the Impact of a Pre-Hearing Assessment Why Improve My Hearing? Telecare Tool on Adult Aural Rehabilitation: A Semi-Structured Interview Study.” International Journal of Audiology. doi:10.1080/14992027.2022.2041740

- Heffernan, E., D. W. Maidment, J. G. Barry, and M. A. Ferguson. 2019. “Refinement and Validation of the Social Participation Restrictions Questionnaire: An Application of Rasch Analysis and Traditional Psychometric Analysis Techniques.” Ear and Hearing 40 (2): 328–339. doi:10.1097/AUD.0000000000000618.

- Henshaw, H.,. D. Clark, S. Kang, and M. A. Ferguson. 2012. “Computer Skills and Internet Use in Adults Aged 50–74 Years: Influence of Hearing Difficulties.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 14 (4): e113. doi:10.2196/jmir.2036.

- Hibbard, J. H. 2009. “Using Systematic Measurement to Target Consumer Activation Strategies.” Medical Care Research and Review : MCRR 66 (1 Suppl): 9S–27S. doi:10.1177/1077558708326969.

- Hibbard, J. H., E. R. Mahoney, J. Stockard, and M. Tusler. 2005. “Development and Testing of a Short Form of the Patient Activation Measure.” Health Services Research 40 (6p1): 1918–1930. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00438.x.

- Hibbard, J. H., and M. Tusler. 2007. “Assessing Activation Stage and Employing a “Next Steps” Approach to Supporting Patient Self-Management.” The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management 30 (1): 2–8. doi:10.1097/00004479-200701000-00002.

- Hickson, L., C. Meyer, K. Lovelock, M. Lampert, and A. Khan. 2014. “Factors Associated with Success with Hearing Aids in Older Adults.” International Journal of Audiology 53 (sup1): S18–S27. doi:10.3109/14992027.2013.860488.

- Jennings, M. B., M. F. Cheesman, and A. Laplante-Lévesque. 2014. “Psychometric Properties of the Self-Efficacy for Situational Communication Management Questionnaire (SESMQ).” Ear and Hearing 35 (2): 221–229. doi:10.1097/01.aud.0000441081.64281.b9.

- Kearns, Rachael, Ben Harris-Roxas, Julie McDonald, Hyun Jung Song, Sarah Dennis, and Mark Harris. 2020. “Implementing the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) in Clinical Settings for Patients with Chronic Conditions: A Scoping Review.” Integrated Healthcare Journal 2 (1): e000032. doi:10.1136/ihj-2019-000032.

- Knudsen, L. V., M. Öberg, C. Nielsen, G. Naylor, and S. E. Kramer. 2010. “Factors Influencing Help Seeking, Hearing Aid Uptake, Hearing Aid Use and Satisfaction With Hearing Aids: A Review of the Literature.” Trends in Amplification 14 (3): 127–154. doi:10.1177/1084713810385712.

- Laplante-Lévesque, A., L. Hickson, and L. Worrall. 2012. “What Makes Adults with Hearing Impairment Take up Hearing Aids or Communication Programs and Achieve Successful Outcomes?” Ear and Hearing 33 (1): 79–93. doi:10.1097/AUD.0b013e31822c26dc.

- Laplante-Lévesque, A., L. Hickson, and L. Worrall. 2013. “Stages of Change in Adults With Acquired Hearing Impairment Seeking Help for the First Time: Application of the Transtheoretical Model in Audiologic Rehabilitation.” Ear and Hearing 34 (4): 447–457. doi:10.1097/AUD.0b013e3182772c49.

- Maddux, J. 2009. “Self-Efficacy: The Power of Believing You Can.” In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology, edited by C. R. Snyder and S. J. Lopez. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Maidment, D. W., W. Brassington, H. Wharrad, and M. A. Ferguson. 2016. “Internet Competency Predicts Practical Hearing Aid Knowledge and Skills in First-Time Hearing Aid Users.” American Journal of Audiology 25 (3S): 303–307.

- McCormack, A., and H. Fortnum. 2013. “Why Do People Fitted with Hearing Aids Not Wear Them?” International Journal of Audiology 52 (5): 360–368. doi:10.3109/14992027.2013.769066.

- Meyer, C., and L. Hickson. 2012. “What Factors Influence Help-Seeking for Hearing Impairment and Hearing Aid Adoption in Older Adults?” International Journal of Audiology 51 (2): 66–74. doi:10.3109/14992027.2011.611178.

- Meyer, C., L. Hickson, K. Lovelock, M. Lampert, and A. Khan. 2014. “An Investigation of Factors That Influence Help-Seeking for Hearing Impairments in Older Adults.” International Journal of Audiology 53 (sup1): S3–S17. doi:10.3109/14992027.2013.839888.

- Moher, David, Sally Hopewell, Kenneth F. Schulz, Victor Montori, Peter C. Gøtzsche, P. J. Devereaux, Diana Elbourne, et al. 2012. “CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: updated Guidelines for Reporting Parallel Group Randomised Trials.” International Journal of Surgery (London, England) 10 (1): 28–55. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2011.10.001.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2018. “Hearing Loss in Adults: Assessment and Management.” https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-cgwave0833/documents

- O’Callaghan, C. A. 2014. “OxMaR: Open Source Free Software for Online Minimization and Randomization for Clinical Trials.” PloS One. 9 (10): e110761. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0110761.

- O’Cathain, Alicia, Jackie Goode, Sarah J. Drabble, Kate J. Thomas, Anne Rudolph, and Jenny Hewison. 2014. “Getting Added Value from Using Qualitative Research With Randomized Controlled Trials: A Qualitative Interview Study.” Trials 15 (1): 215. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-15-215.

- Office for National Statistics 2019. “Internet Users, UK: 2019.” https://www.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/itandinternetindustry/bulletins/internetusers/2018

- Prochaska, J. O., and C. C. DiClemente. 1986. Toward a Comprehensive Model of Change Treating Addictive Behaviors. New York: Springer.

- Ridgeway, J., L. Hickson, and C. Lind. 2015. “Autonomous Motivation is Associated With Hearing Aid Adoption.” International Journal of Audiology 54: 478–484.

- Rubak, S., A. Sandbaek, T. Lauritzen, and B. Christensen. 2005. “Motivational Interviewing: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” British Journal of General Practice 55: 305–312.

- Saunders, G. H., and A. Roughley. 2021. “Audiology in the Time of COVID-19: Practices and Opinions of Audiologists in the UK.” International Journal of Audiology. 60 (4): 255–262. doi:10.1080/14992027.14992020.11814432.

- Sawyer, C. S., K. J. Munro, P. Dawes, M. P. O'Driscoll, and C. J. Armitage. 2019. “Beyond Motivation: identifying Targets for Intervention to Increase Hearing Aid Use in Adults.” International Journal of Audiology 58 (1): 53–58.

- Schönborn, Danielle, Faheema Mahomed Asmail, Karina C. De Sousa, Ariane Laplante-Lévesque, David R. Moore, Cas Smits, De Wet Swanepoel, et al. 2020. “Characteristics and Help-Seeking Behavior of People Failing a Smart Device Self-Test for Hearing.” American Journal of Audiology 29 (3): 365–374. doi:10.1044/2020_AJA-19-00098.

- Smith, S.,. K. Pichora-Fuller, K. Watts, and C. La More. 2011. “Development of the Listening Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (LSEQ).” International Journal of Audiology 46: 759–771.

- Solheim, J., C. Gay, A. Lerdal, L. Hickson, and K. J. Kvaerner. 2018. “An Evaluation of Motivational Interviewing for Increasing Hearing Aid Use: A Pilot Study.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 29: 696–705.

- Swanepoel, D. W., and J. W. Hall. 2020. “Making Audiology Work during COVID-19 and beyond.” The Hearing Journal 73 (6): 20, 22, 23, 24–24. doi:10.1097/01.HJ.0000669852.90548.75.

- Ventry, I. M., and B. E. Weinstein. 1982. “The Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly: A New Tool.” Ear and Hearing 3 (3): 128–134. doi:10.1097/00003446-198205000-00006.

- Weinstein, B. E. 2012. Geriatric Audiology. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc.

- West, R., and S. L. Smith. 2007. “Development of a Hearing Aid Self-Efficacy Questionnaire.” International Journal of Audiology 46 (12): 759–771. doi:10.1080/14992020701545898.

- Whitmer, W. M., P. Howell, and M. A. Akeroyd. 2014. “Proposed Norms for the Glasgow Hearing-Aid Benefit Profile (GHABP) Questionnaire.” International Journal of Audiology 53 (5): 345–351. doi:10.3109/14992027.2013.876110.