Abstract

Objective

Patient and public involvement (PPI) in research improves relevance to end users and improves processes including recruitment participants. PPI in our research has gone from being non-existent to ubiquitous over a few years. We provide critical reflections on the benefits and challenges of PPI.

Design

Case studies are reported according to a modified GRIP2 framework; the aims, methodology, impact of PPI and critical reflections on each case and our experiences with PPI in general.

Study sample

We report five UK projects that included PPI from teenagers, families, people living with dementia, autistic people, and people from South Asian and d/Deaf communities.

Results

Our experience has progressed from understanding the rationale to grappling methodologies and integrating PPI in our research. PPI took place at all stages of research, although commonly involved input to design including recruitment and development of study materials. Methodologies varied between projects, including PPI co-investigators, advisory panels and online surveys.

Conclusion

On-going challenges include addressing social exclusion from research for people that lack digital access following increasing on-line PPI and involvement from underserved communities. PPI was initially motivated by funders; however the benefits have driven widespread PPI, ensuring our research is relevant to people living with hearing loss.

Introduction

Patient and public involvement in research (PPI; sometimes also referred to as consumer and community involvement, patient and public voice, lay involvement, service user involvement and other terms) refers to “research being carried out ‘with’ or ‘by’ members of the public rather than ‘to’, ‘about’ or ‘for’ them” (National Insitute of Health Research Citation2021). PPI is different to research participation in that, rather than patients and the public being passive “subjects” of research, PPI offers an active collaborative partnership between members of the public and researchers that influences and shapes research. “Members of the public” may include people with lived experience of the health condition being researched, carers or family members, people from a demographic of interest, or patient advocates from charity organisations. PPI is also distinct from engagement, which is information dissemination to raise awareness and create interest among the public in research. PPI may take place at any phase in the research cycle, with lay people identifying research priorities, being co-investigators or advisors for a research project, helping develop study materials (e.g. participant information sheets), collecting and analysing data (e.g. interviews with research participants) and disseminating research outcomes. As an aside, one example of research priority setting is the work of the UK James Lind Alliance (JLA; https://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/). The JLA is a not-for-profit organisation supported by the National Institute for Health Research that works with patients, carers and clinicians to identify and prioritise unanswered questions or evidence gaps so that research funders are aware of the issues that are of most importance to health service users.

Funding organisations such as the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) in the UK, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) in Australia, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the USA are increasingly requiring PPI in the planning and running of health research. The rationale for PPI is that by testing the assumptions that researchers make about their research, involving patients and the public improves relevance of the research to end users (Gasson et al. Citation2015) as well as improving research processes such as recruitment and retention of research participants (Crocker et al. Citation2018; Ennis and Wykes Citation2013). There is also an ethical motivation to involve those who are the focus of research (and who indirectly fund much of the research) in the planning and conduct of research. Researchers may benefit from the acquisition of skills and knowledge as a result of working with people with “lived experience” of health conditions who have different perspectives to those of the researchers (Staley Citation2017).

A further potential benefit of PPI is to promote participation in research by communities that have traditionally not been involved in research (National Institute for Health Research Citation2019). People from deprived communities are more likely to experience poorer health outcomes, but they are also less likely to be involved in discussions and decisions about addressing health inequalities (Marmot Citation2020). People from minority ethnic and deprived communities report less confidence that they will be treated with dignity and respect as research participants (Hunn Citation2021). Participants in UK health research (for example, the UK Biobank, an in-depth resource of genetic and health information from 500,000 adults (Fry et al. Citation2017)) tend to be affluent and white. Inclusive PPI is a process that may help build relationships with community groups, develop research that addresses the needs of under-served communities and foster representative participation in research.

Several good quality resources exist to support hearing researchers who wish to include PPI in their research (for example, https://www.nihr.ac.uk/health-and-care-professionals/engagement-and-participation-in-research/). Few examples of PPI in hearing research have been described in detail in the literature. Boddy et al. (Citation2020) reflected on how a PPI group was set up within a local UK National Health Service audiology department, and how the group influenced the department’s research and service improvement. In this manuscript we aim to outline the importance of PPI in hearing research. Five case studies (Supplementary Appendix 1: Case study summary) within our centre in the Northwest of England have been selected to highlight a diverse range of approaches to involving lay people in hearing research, and the opportunities and benefits of each. PPI contributors included paediatric, teenage and adult populations, families, people living with dementia, autistic people, people with hearing loss and people from South Asian and d/Deaf communities. We offer our critical reflections to provide insight into some of the challenges of PPI and suggest potential solutions.

Case studies

Pharmacogenetics to avoid loss of hearing – PALOH

Gentamicin is an antibiotic prescribed to babies with early-onset sepsis and should be administered in the “golden-hour” after diagnosis. Around 1 in 500 babies carry a genetic variant which predisposes to profound hearing loss following therapeutic doses of gentamicin (McDermott et al. Citation2022). The Pharmacogenetics to Avoid Loss of Hearing (PALOH) study developed a rapid bedside genetic test to identify babies at risk of gentamicin-induced hearing loss (McDermott et al. Citation2021). The aim of the project was to assess implementation of this test in two Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICUs). There were several challenges; admission to NICU is a uniquely stressful time for parents. It was paramount that parents’ views were included from the outset. We sought parents’ input on: (i) design and delivery of the study; (ii) how to navigate ethical issues such as recruitment of parents; (iii) development of understandable study materials; (iv) dissemination of study findings.

Methods used for PPI

PPI representatives (parents with experience of children in NICU and/or experience of hearing loss) were recruited through PPI networks (through Vocal, a not-for-profit PPI organisation hosted by the Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust; https://www.wearevocal.org/), via social media and posters displayed in NICU family rooms, Children’s Outpatients, and Audiology departments. PPI representatives were consulted on the initial study proposal, which helped secure funding. Two representatives continued as co-applicants on the study team and stakeholder committee.

With the help of the PPI co-applicants and Vocal, a Parent Advisory Group (PAG) was established. Parents who expressed interest were given an induction pack with information on PPI, background to the study, signposting to training and support, and ground rules for involvement that had been co-developed with our PPI co-applicants. The PAG met for four half-day workshops, at 6-monthly intervals. Six to eight participants attended each meeting with opportunities to engage remotely for parents unable to travel. Sessions were designed to be as inclusive as possible, allowing parents to bring their children along and speak about their experiences in a relaxed environment. The group was led by Vocal and the PALOH Project Manager and sessions were co-designed with one of the parent co-applicants. Between meetings, engagement was maintained via email and a closed Facebook group. One of the PAG members joined the study team at the Research Ethics Committee (REC) meeting where she shared her experience with the REC.

Impact of PPI

The design of the study

The PAG developed a feedback “postcard” for parents to complete in their own time, resulting in feedback from parents in addition to those interviewed for the qualitative study arm. The language in this postcard and the interview was co-written by the PAG.

The consenting and testing process

The PAG critiqued the testing procedure, leading to changes in procedure, guidelines, and equipment design. Parents fed back that the need for rapid clinical information in an acutely stressful situation meant that they would prefer NOT to be approached about the study, but to agree to presumed consent in this context, with the opportunity to withdraw that consent at a later point. This feedback was very powerful in persuading the ethics committee that this was the preferred consent model in this study.

Patient materials

The PAG advised on wording of patient-facing study documents, to make information easily understandable.

Inclusion criteria and follow-up

The PAG influenced the inclusion criteria for the trial along with guidelines for follow-up of babies via the clinical genetics service. Parents felt that it would be appropriate to include all babies admitted to the NICU for inclusion in the study (as this was a presumed consent model). This would ensure that no baby missed the opportunity to participate and additionally avoid gentamicin induced toxicity.

Dissemination

Several members of the PAG were involved in the dissemination strategy and have given interviews for local media, been involved in podcasts and contributed to the maintenance of the study’s Twitter feed. One parent with her child appeared on a TV report after publication of the research findings (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eELuv69pRnk). Some members have presented their experiences of PPI at a local Hearing Health conference. The two PPI co-applicants were named authors on the major study publication emanating from the study, reflecting their contribution to the success of the work (McDermott, Mahaveer et al. Citation2022). We are publishing a paper with parental interviews and responses collected on postcards which detail parental experiences more fully.

Critical reflections

PPI was invaluable, leading to a better experience for participants and ensuring that the genetic testing procedures were acceptable to parents. Parent representation at the ethics committee meeting was helpful in navigating the issues around consent for genetic analysis in an acute setting and helped ethical approval for the first emergency genetic test in the UK. Strategies for recruitment to the PAG and stakeholder committee could have been improved to increase attendance and introduce more diversity. All PAG members were female and of white British ethnicity which may have limited generalisability of the advice. Strategies should extend accessibility to underserved communities and increase recruitment of fathers.

The hearing in teenagers (HIT) study: understanding the effects of noise exposure on hearing in teenagers

Noise exposure is the main cause of preventable hearing loss and an estimated 1.1 billion young people globally could be at risk of noise-induced hearing loss (World Health Organization Citation2015). Auditory deficits that are not detectable by conventional hearing tests may pose an additional burden (Plack et al. Citation2016). The Hearing in Teenagers (HIT) study is investigating the subclinical effects of noise exposure in 220 teenagers, following them over three years from age 16/17 years. Success of the HIT study hinges on recruitment and retention. Of the 220 teenagers who attend the test centre for an initial 3-h test session, at least 60% must return three years later for follow-up. The study must be sufficiently rewarding and engaging that participants are motivated to travel for their final session, since many local teenagers will reside elsewhere by age 19. The aims for PPI were to: (i) obtain advice on recruitment, (ii) identify ways to improve the experience of participation, and (iii) ensure that messaging and data-collection methods were appropriate for diverse groups.

Methods used for PPI

HIT researchers were assisted by Vocal, which arranged and chaired a 2-h Zoom session with five teenagers aged 15–17, recruited from Vocal’s youth advisory group. Researchers gave a short presentation on the study and a demonstration of hearing in noise. The teenagers advised via preference polls, verbal suggestions, and group discussion. Researchers welcomed spontaneous input but also set aside two discussion periods in which advice was sought on the most pressing research design and participation challenges (Supplementary Appendix 2: Questions and discussion points).

Impact of PPI

Structure and format

The teenagers advised against online data collection, noting that some homes lack access to computers, WiFi, and quiet environments.

Recruitment avenues

The teenagers offered advice on online and offline advertising to teenagers, including peer-to-peer recruitment.

Compensation

The teenagers judged some elements of compensation adequate and recommended augmenting others. They suggested that more attention be paid to the "intangible" costs to participants: not just time spent in the lab, but also travel costs and the inconvenience of ongoing participation.

Additional incentives

The teenagers suggested emphasising the non-monetary benefits of participation, including hands-on research experience (for science students especially) and providing participants with letters detailing study involvement for participants’ CVs.

Messaging

In both recruitment and data-collection materials, the teenagers recommended that descriptions of noisy activities focus less on "nightlife" like gigs and nightclubs, as these are irrelevant to many teenagers for cultural, religious and personal reasons.

Critical reflections

This was our first experience of PPI with teenagers and PPI via video-conference. A sample of five teenagers yielded useful insights. A larger group may have been counterproductive, discouraging the more reticent contributors. Two researchers were essential: one to speak, the other to take notes and draw out responses that might otherwise be missed. Visual and auditory demonstrations were useful for communicating technical aspects of the study. It was challenging to provide an appropriate level of information; we needed to avoid overload but provide an adequate overview. Similarly, we had to be clear on the questions we needed answered, but also to provide opportunity for other insights (for example, impracticality of home data collection). Overall, we found that PPI was time consuming but worthwhile. Based on informal feedback from study participants, changes following PPI advice (e.g. around recruitment) had facilitated participation.

Sensecog: promoting health for eyes, ears and mind

SENSECog was a five‐year European research programme investigating the impact of age-related hearing and/or vision problems on mental well-being for older Europeans. The project involved: epidemiological modelling of the interplay of hearing, vision and cognitive impairment (Maharani et al. 2020a, 2020b; Maharani, Dawes, Nazroo, Tampubolon, and Pendleton 2018; Maharani et al. 2020c; Maharani, Dawes, Nazroo, Tampubolon, Pendleton, et al. 2018; Maharani et al. Citation2017); development and validation of cognitive assessments for people with hearing/vision impairment (Dawes et al. Citation2019; Wolski et al. Citation2019); evaluation of a home-based hearing and vision intervention for improving quality of life for people with dementia (Leroi et al. Citation2020; Leroi, Wolski, and Hann Citation2019; Regan et al. Citation2017). The translational focus of the project meant that PPI was vital in ensuring outputs would improve outcomes for older Europeans. We sought to (i) use the views of people with lived experience to shape the research and make it more relevant for people with dementia; and (ii) ensure meaningful involvement by research awareness training for PPI contributors (based on Enhancing the Quality of User Involved Care Planning (EQUIP) program: https://www.nice.org.uk/sharedlearning/enhancing-the-quality-of-service-user-involved-care-planning-in-mental-health-services-equip) and support arrangements (e.g. written materials in large print) according to individual need (Miah, Parsons, et al. Citation2020).

Methods used for PPI

PPI groups of seven to nine people with experiences of sensory loss and dementia were established in Manchester (UK), Nice (France), Nicosia (Cyprus) and Athens (Greece). Group members were recruited by written advertising (i.e. emails describing the project and the role of PPI) through local organisations working with older people with dementia and/or hearing/vision impairment (e.g. memory clinics, charity organisations and support groups). Groups met every 3 months in locations convenient to group members (e.g. community centres). Groups were provided with the skills and knowledge to support their involvement in the project via research awareness training (Miah, Dawes, et al. Citation2020) relevant to the topic of the meeting delivered immediately prior to meetings. Training included information about the research process, quantitative and qualitative research, health economics and research ethics. Groups were supported by a local coordinator who was a member of the researcher team. Coordinators communicated with the central PPI coordinator in Manchester who assisted with set-up of local groups, training local coordinators in PPI, and co-ordination of PPI across sites. Local coordinators arranged group meetings, liaised with researchers, developed activities to support involvement, and provided group members with quarterly newsletters reporting project progress.

At the first group meeting, coordinators completed a support needs form with each group member and arranged individual strategies to facilitate involvement. Coordinators monitored the on-going requirements of each group member and adapted strategies accordingly. For example, people with vision problems were provided with materials in large font black print on yellow paper. Groups identified and planned PPI activities at the start of the project, subsequently published as a PPI protocol (for example, identifying the impacts of hearing/vision impairment that should be taken into account in health economic modelling of the benefits of hearing/vision interventions) (Miah et al. Citation2018). Using a template, groups were provided with written feedback from researchers. The template included sections describing the issue that PPI was sought for, a summary of PPI advice, actions taken/not taken to address that advice with accompanying explanations. Research output reported the role and impact of PPI (Miah, Parsons, et al. Citation2020), in line with recommended reporting of PPI (Staniszewska et al. Citation2017).

Impact of PPI

Researchers and PPI contributors

Researchers reported increased awareness of “real world” impacts of dementia. PPI contributors felt they made an important contribution to improving outcomes for people with dementia via their PPI role.

Study information and recruitment materials

Wording of study information and recruitment materials was amended in line with PPI feedback to ensure that they were understandable.

Intervention development

Development of a home-based sensory intervention for people with dementia, content and layout of a computerised memory test, interpretation of results, and prioritisation of clinical recommendations were informed by PPI (Miah, Parsons, et al. Citation2020). As an example, the intervention included development of a dementia-friendly leaflet about hearing aid use. Following PPI, the size of the leaflet was increased, with larger font, simplified wording and more white space to make it easier to read. As a further example, PPI on a computerised memory test resulted in simplification of instructions, increased text size and additional reminders on how to proceed through the test.

Dissemination of results

PPI contributors spoke about their experiences at local conferences.

Critical reflections

PPI was obtained at all stages of the research in this project – except in the formulation of the programme proposal. PPI should ideally inform conception of a research program and setting research agendas to ensure research priorities reflect patient/public perspectives. Not including PPI from conception entails a risk that the premise and aims of the project may be flawed and/or inappropriate. PPI was not included in the formative stage because of (i) the short timescale for the grant submission, (ii) lack of resources to support PPI and (iii) the funding call did not require PPI as part of the proposal. We approached local organisations to recruit group members but received few responses and were not effective in involving a diverse range of participants (no responses from anyone from a Black, Asian and minority ethnic or underserved community). Our approach was to contact community organisations identified by Vocal via email. A more active approach (e.g. arranging to speak with community groups in person) and investment of resources in building collaborative relationships may facilitate involvement of diverse communities. Lack of diversity in PPI may have limited the advice that PPI groups offered. Efforts to support involvement of people with cognitive and/or sensory impairments to shape this multi-national research project and make it more relevant for people with dementia were successful, based on documented changes following PPI.

The SPAACE project: speech perception by autistic adults in complex environments

Autistic people have long reported difficulties with speech perception, especially complex and noisy listening environments (Grandin Citation1992), yet there are no systematically described qualitative data on their experiences. The SPAACE project gathered data on autistic people’s speech-perception experiences, including difficulties, impacts, and coping strategies. Methods included semi-structured interviews plus a larger-scale online survey. The role played by autistic collaborators was initially expected to be around generation of research questions and advice on recruitment, data collection, and dissemination. However, we found that all parties would benefit from more substantial involvement, and the SPAACE project evolved into co-produced research, with shared power, duties and learning from start to finish. Our autistic collaborators designed, recruited, analysed, co-authored, and presented as members of the research team. Note that the autistic advisors on the SPAACE project preferred identity-first language (“autistic person”) rather than person-first language (“person with autism”). Identity-first language frames autism as an identity rather than a disorder. We used the preferred terminology here.

Methods used for PPI

The team was composed of two hearing researchers, two autism researchers, and two autistic researchers. Face-to-face or video-conference meetings were the primary means of communication, supplemented by email and text messaging. The approach resembles that of any research team, except that we found we needed to communicate using non-specialist terms rather than using hearing research jargon. We provided a written glossary to explain hearing terminology. Our autistic collaborators displayed great patience in explaining which of our assumptions about the autistic community were mistaken, and how to avoid the pitfalls that make research “autism-unfriendly” (e.g. ambiguous language or implied meanings that are not readily apparent to autistic people). Our autistic collaborators presented our work to other members of the autistic community, garnering further feedback on our research methods.

Impact of PPI

The inception of the project

The project research questions were generated following a research-priority-setting exercise with autistic collaborators.

Study design

Our autistic collaborators directed us to a mixed-methods approach, including a large on-line quantitative sample to increase the diversity of our autistic participants.

Recruitment and data-collection

Our autistic collaborators developed recruitment materials and used their community networks to recruit participants. Our collaborators developed autism-friendly wording for interview and survey materials to make meanings clear.

Data analysis and dissemination

With support and training, autistic team members analysed qualitative and quantitative data. Their perspectives were especially important for the qualitative analyses, to prevent “overshadowing” of autistic voices by those of neurotypical researchers (Milton Citation2012; i.e. neurotypical researchers imposing their interpretations on research findings that may differ from those of autistic people). Autistic collaborators co-authored manuscripts (Sturrock et al. Citation2022) and co-presented talks to researchers, clinicians, and the autistic community.

Critical reflections

Successful co-production depended on the individuals involved: their capabilities, interests, and willingness to devote time and effort to the project. Co-production required flexibility, negotiation, mutual support, and creativity. The experience provided valuable research skills to our autistic collaborators and an education in co-production and autistic perspectives to the hearing scientists. We now believe that co-production is essential for any autism study. If willing PPI collaborators are found, devote time to exploring their capabilities and interests, as one would with any collaborator. Recognise that support and training may be required, but that this training could yield PPI collaborators with both technical competence and “expertise by experience”.

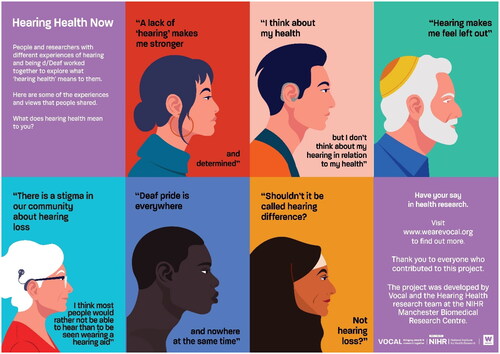

Hearing health now – promoting awareness of research involvement

Hearing Health Now was a patient-public involvement and engagement (PPIE) project co-produced with community groups and researchers. To address inequalities in health outcomes and involvement in research, a key priority for the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is to increase involvement of communities that have historically not been involved with research. The project aimed to provide opportunities for people from local communities who had little or no involvement with research to consider what the concept of “hearing health” meant to them and to develop content to share these ideas with researchers as well as their communities. The rationale was that before people can become actively involved in research there is a need for researchers to understand and engage with the scope and complexity of experience covered by hearing research. The project was led by Vocal and developed with researchers, people with hearing loss, people from South Asian communities and people from the d/Deaf community.

Methods used for PPIE

Following consultation with all the groups, we ran three half day workshops at community venues with (i) people with hearing loss, (ii) people who are d/Deaf and use BSL (British Sign Language), and (iii) South Asian groups. Eleven hearing researchers and over 50 members of the public took part. We worked with a graphic designer with experience of working with people who are d/Deaf. We developed creative activities to elicit people’s views on “hearing health”, such as creating visual representations of their experiences and working in groups to plan activities in subsequent workshops. Workshops covered communication and social aspects of hearing, sound and technology, stigma, and inequalities as well as physical and mental health. The designer developed material to summarise the views from the workshops and participants fed back on the design and content of the material.

Impact of PPIE

Including diverse opinions

People felt that there is a lack of representation of the diversity of their experiences in popular culture and social discourse. The posters and animation which they created with the designer communicated what was important to them (e.g. ) These materials are being used in awareness raising campaigns (e.g. social media campaigns for World Hearing Day) and to highlight opportunities for involvement in hearing research.

Researcher perceptions

This was the first time that researchers had worked with such diverse groups of contributors in relation to hearing health. One researcher commented “What really struck home was how unique each person’s experience was, and to discover what hearing means to each individual.”

Inclusive research:

People felt that everyone should have opportunities to have a say in research and that research environments should be inclusive, such as using accessible settings (e.g. community centres), activities suitable for people who lip read and providing assistive technology such as hearing loops and interpreters for BSL speakers.

Critical reflections

Hearing Health Now enabled researchers and members of the public to engage with each other to discuss and challenge definitions and assumptions around hearing health. Creative methods enabled participants to communicate their experiences. Hearing researchers appreciated the impact of individual experiences of hearing on people’s lives. The project increased researchers’ experience of community engagement and working in partnership with community stakeholders. The project highlighted the importance of inclusive language (i.e. mutually understood terminology for researchers and members of the public). Although “hearing health” was the focus of the project, many people were unsure about what “hearing health” means in practice. “Hearing health” may not yet be meaningful to the public in the way that vision health is accepted, in order words, maintaining good hearing rather than focussing on addressing hearing loss. PPI perspectives on language and terminology may enable better communication and engagement with patients and the public.

Discussion

PPI in the hearing research projects conducted at the Manchester Centre for Audiology and Deafness has been steadily increasing, particularly since the establishment of the NIHR-funded Manchester Biomedical Research Centre in 2017 and other NIHR-funded research that specifies a high degree of PPI at all stages of the research. PPI has similarly increased at other UK hearing research centres (e.g. Boddy et al. Citation2020; Ferguson et al. Citation2018; Henshaw et al. Citation2015; Maidment et al. Citation2020). As in other health research, patients and the public had historically not usually been involved in hearing research.

Our experience included first understanding the rationale for and potential benefits of PPI as well as getting to grips with the practicalities of PPI in hearing research. The case studies described above illustrate how researchers, working with varied populations and study questions, formed creative and productive working alliances with patients and the public. PPI increased researcher engagement with end-users of research, promoting self-reflection in relation to assumptions implicit in research and its utility. Although the initial impetus for PPI was due to funder-mandated requirements, at the point of writing, all our on-going and planned research projects include PPI and researchers value the insights that PPI provides.

One insight from the case studies above is that PPI methodologies, types of input and input at different stages of research may be appropriately different between studies, depending on the stage of research and the population that is the focus of the research. The approach in each study was developed following published guidance (e.g. NIHR Centre for Engagement and Dissemination), local PPI experts (i.e. Vocal) and/or PPI advisors themselves (e.g. via PPI co-investigators). PPI included generating and prioritising research questions, advising on study design, data analysis and dissemination, co-authoring papers, public representatives as grant co-applicants, attending ethics committee meetings and generating further recruitment via direct contact with communities. Most studies included PPI input on study design, recruitment and developing study materials. Fewer studies included PPI in data analysis and dissemination, perhaps because of the additional time and resources that involvement at every stage of research would entail. Studies that do not include PPI in analysis and dissemination may risk not accounting for lay people’s perspectives in interpreting the significance of research findings and effectively communicating these to the public.

The methodology to obtain PPI input varied, including planning meetings, email surveys, teleconferences and creative workshops. During the COVID-19 pandemic, most of our PPI took place in online focus groups (via zoom or similar). Online PPI may limit involvement of people with hearing loss due to reduction in non-verbal cues. We relied on tools including closed captioning, speech recognition and bluetooth connection to hearing devices helped facilitate online working with people with hearing loss. Online PPI may facilitate participation for some people (i.e. people with access to digital technology and high digital skills) but risks exclusion from research for people that lack digital access or skills (Watts Citation2020). PPI should include a variety of involvement options to mitigate against digital exclusion.

Some case studies benefitted from expert PPI advice. However, having expert PPI support was not a necessary precondition for PPI; some studies made use of freely available PPI resources (such as those from the NIHR). Several case studies provided training for PPI representatives to ensure their contribution was meaningful. For example, SENSEcog included training that was tailored to the topic that PPI was being sought for (such as health economic analysis). Researchers may also benefit from PPI training in terms of effective communication, identifying, and responding to accessibility needs (e.g. meeting rooms that are appropriate, providing interpreters, financial support for childcare costs or transport to enable involvement), awareness of unfair power dynamics between researchers and PPI contributors, actively listening to PPI contributors and responding to feedback. Formal training opportunities may be available, but researchers could also obtain similar benefits from freely available online resources (e.g. NIHR Centre for Engagement and Dissemination (CED): https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/centre-for-engagement-and-dissemination-recognition-payments-for-public-contributors/24979). Apart from the SPAACE project (with PPI co-investigators), all PPI contributors were paid for their time and reimbursed costs of involvement (e.g. travel), based on levels recommended by the NIHR Centre for Engagement and Dissemination (CED; https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/centre-for-engagement-and-dissemination-recognition-payments-for-public-contributors/24979). Reimbursement was via cash payment, and PPI was budgeted in research proposals.

A general observation was that PPI was helpful for participant recruitment and retention, particularly in projects that focussed on populations with needs that may present challenges for research participation. In the case studies above, such populations included teenagers, autistic people, people with dementia, and parents with experience of having a child in a new-born intensive care unit. However, we currently lack data to support the researchers’ impressions that PPI facilitated participation of people with specific needs. Reviews conclude that PPI does foster recruitment to research studies in general (Crocker et al. Citation2018; Ennis and Wykes Citation2013). One would imagine that including a PPI perspective may be particularly critical to facilitate participation of populations with specific needs which the researchers may not understand and address. The case studies above illustrate how simple changes to research planning may have a critical impact. These simple changes may not be obvious to researchers until they have been pointed out by lay people.

The case studies highlighted examples of under-served populations that are pertinent for hearing research, including under-involvement of fathers in paediatric hearing research (PALOH). Under-involvement of low socio-economic and minority ethnic communities in research was a focus of Hearing Health Now. These communities tend to have higher rates of hearing loss with lower rates of hearing aid use, as well as lower rates of participation in research (Dawes et al. Citation2014; Marmot Citation2020; Taylor et al. Citation2021). Hearing loss and associated stigma may also be particularly problematic for some ethnic groups (Manchaiah et al. Citation2015). Although researchers felt PPI had facilitated participation, diversity and representativeness of participants in research remains an on-going challenge. For example, SENSEcog researchers attempted to engage with local communities to invite research involvement but found that contacting local community organisations via email was not successful. The difficulty in achieving diversity in a PPI panel was also reflected on by Boddy et al. (Citation2020). For other studies it was impossible to monitor diversity and inclusiveness of either PPI or research participation because information on people’s background was not recorded. Recording information about people’s background helps to focus attention on boosting involvement of people from populations that health interventions are intended for (for example, by using the NIHR Health Inequalities Assessment Toolkit https://www.hiat.org.uk/). Increasing availability of resources and training to increase cultural competencies and inclusive approaches to PPI (e.g. https://www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Being-Inclusive-Health-Research.pdf) may be useful in giving researchers the tools to boost inclusiveness of their research. As there are long-standing cultural and systemic barriers to Black, Asian, minority ethnic and other underserved community’s involvement in research, equitable and inclusive involvement is a long-term goal that requires commitment at all levels. The Hearing Health Now project was about engagement with underserved communities including people from South Asian communities and people from the d/Deaf community. Alongside training for researchers, much on-going active involvement is required on behalf of the research community to build constructive relationships with underserved communities.

Some researchers may resist devoting resources to PPI that they feel could be devoted to other uses. Some frameworks exist to report PPI in research (e.g. GRIPP2, Public Involvement Impact Assessment Framework (Public Involvement Impact Assessment Framework (PiiAF)), Citation2022; Staniszewska et al. Citation2017)), but these have their limitations and do not always capture the benefits and impacts of PPI. It can be difficult to quantify the benefits from PPI, since these are often complex and intangible. PPI input to research studies is usually not carried out in controlled ways that allow the impact of PPI to be dis-entangled. It is therefore challenging to present robust cost-effectiveness evidence for PPI. If future data could be accumulated, PPI might be justified purely based on cost-effectiveness. However, the benefits of PPI go beyond the material. As emphasised in the introduction, there is an ethical imperative in insuring that the end users of research are involved in its planning and conduct. This is particularly the case in terms of promoting the needs of under-served communities and fostering inclusive and representative participation in hearing research.

Conclusions

Over the past few years, PPI in our hearing research has gone from being non-existent to ubiquitous. The introduction of PPI was initiated primarily by funding requirements. Widespread adoption and increasing depth and quality of PPI reflects its perceived utility by researchers. PPI is particularly pertinent for research that is translational, focussed on health services and includes communities that present special challenges to research participation. Increasing availability of good quality resources (e.g. NIHR CED) facilitates PPI. We therefore encourage all hearing researchers to actively engage in PPI at all stages of their research, and routinely report PPI impacts in the outputs from the research, so that the benefits of PPI can be fully realised and monitored. The benefits of PPI have driven increasing use of PPI in improving our hearing research, ensuring that the research is grounded in the reality of people’s lives, that the research incorporates the experience of socially excluded communities, and that participants become co-creators of the research about them.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (938.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to dedicate this publication to our late friend and colleague Suzanne Parsons, social scientist, health services researcher and patient and public involvement manager and advocate for patients. PPI co-authors participated in discussion meetings on the scope and focus of the paper and the choice of case studies. PPI co-authors contributed to writing case studies and provided input and approval for drafts of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Boddy, L., R. Allen, R. Parker, M. E. O'Hara, and A. V. Gosling. 2020. “PANDA: A Case-Study Examining a Successful Audiology and Otology Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement Research Group.” Patient Experience Journal 7 (3):230–241. doi:10.35680/2372-0247.1431.

- Crocker, J. C., I. Ricci-Cabello, A. Parker, J. A. Hirst, A. Chant, S. Petit-Zeman, D. Evans, and S. Rees. 2018. “Impact of Patient and Public Involvement on Enrolment and Retention in Clinical Trials: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 363:k4738. doi:10.1136/bmj.k4738.

- Dawes, P., H. Fortnum, D. R. Moore, R. Emsley, P. Norman, K. J. Cruickshanks, A. C. Davis, et al. 2014. “Hearing in Middle Age: A Population Snapshot of 40-69 Year Olds in the UK.” Ear and Hearing 35 (3):e44–e51. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000010.

- Dawes, P., A. Pye, D. Reeves, W. K. Yeung, S. Sheikh, C. Thodi, A. P. Charalambous, K. Gallant, Z. Nasreddine, and I. Leroi. 2019. “Protocol for the Development of Versions of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for People with Hearing or Vision Impairment.” BMJ Open 9 (3):e026246. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026246.

- Ennis, L., and T. Wykes. 2013. “Impact of Patient Involvement in Mental Health Research: Longitudinal Study.” The British Journal of Psychiatry 203 (5):381–386. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119818.

- Ferguson, M., P. Leighton, M. Brandreth, and H. Wharrad. 2018. “Development of a Multimedia Educational Programme for First-Time Hearing Aid Users: A Participatory Design.” International Journal of Audiology 57 (8):600–609. doi:10.1080/14992027.2018.1457803.

- Fry, A., T. J. Littlejohns, C. Sudlow, N. Doherty, L. Adamska, T. Sprosen, R. Collins, and N. E. Allen. 2017. “Comparison of Sociodemographic and Health-Related Characteristics of UK Biobank Participants with Those of the General Population.” American Journal of Epidemiology 186 (9):1026–1034. doi:10.1093/aje/kwx246.

- Gasson, S., J. Bliss, M. Jamal-Hanjani, M. Krebs, C. Swanton, and M. Wilcox. 2015. “The Value of Patient and Public Involvement in Trial Design and Development.” Clinical Oncology 27 (12):747–749. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2015.06.020.

- Grandin, T. 1992. Sensory, Visual Thinking and Communication Problems. The Hague, Netherlands: IAAE Congress.

- Henshaw, H., L. Sharkey, D. Crowe, and M. Ferguson. 2015. “Research Priorities for Mild-to-Moderate Hearing Loss in Adults.” The Lancet 386 (10009):2140–2141. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01048-X.

- Hunn, A. 2021. “Survey of the General Public: Attitudes towards Health Research.” https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/www.hra.nhs.uk/media/documents/survey-general-public-attitudes-towards-health-research.pdf

- Leroi, I., Z. Simkin, E. Hooper, L. Wolski, H. Abrams, C. J. Armitage, E. Camacho, et al. 2020. “Impact of an Intervention to Support Hearing and Vision in Dementia: the SENSE‐Cog Field Trial.” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 35 (4):348–357. doi:10.1002/gps.5231.

- Leroi, I., L. Wolski, and M. Hann. 2019. “Support Care Needs of People with Dementia and Hearing and Vision Impairment: A European Perspective.” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 100 (12):e203. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2019.10.126.

- Maharani, A., P. Dawes, J. Nazroo, G. Tampubolon, and N. Pendleton. 2020a. “Associations Between Self-Reported Sensory Impairment and Risk of Cognitive Decline and Impairment in the Health and Retirement Study Cohort.” The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 75 (6):1230–1242. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbz043.

- Maharani, A., P. Dawes, J. Nazroo, G. Tampubolon, and N. Pendleton. 2020b. “Healthcare System Performance and Socioeconomic Inequalities in Hearing and Visual Impairments in 17 European Countries.” European Journal of Public Health 31 (1):79–86. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckaa155.

- Maharani, A., P. Dawes, J. Nazroo, G. Tampubolon, and N. Pendleton. 2020c. “Trajectories of Recall Memory as Predictive of Hearing Impairment: A Longitudinal Cohort Study.” PloS One 15 (6):e0234623. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0234623.

- Maharani, A., P. Dawes, J. Nazroo, G. Tampubolon, and N. Pendleton. 2018. “Visual and Hearing Impairments Are Associated with Cognitive Decline in Older People.” Age and Ageing 47 (4):575–581. doi:10.1093/ageing/afy061.

- Maharani, A., P. Dawes, J. Nazroo, G. Tampubolon, N. Pendleton, G. Bertelsen, S. Cosh, A. Cougnard‐Grégoire, and C. Delcourt. 2018. “Longitudinal Relationship between Hearing Aid Use and Cognitive Function in Older Americans.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 66 (6):1130–1136. doi:10.1111/jgs.15363.

- Maharani, A., N. Pendleton, G. Tampubolon, J. Nazroo, and P. Dawes. 2017. “Sensory Impairments and Cognitive Ageing among Older Europeans: A Longitudinal Analysis.” Alzheimer’s & Dementia 13 (7S_Part_11) doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2017.07.176.

- Maidment, D. W., N. S. Coulson, H. Wharrad, M. Taylor, and M. A. Ferguson. 2020. “The Development of an mHealth Educational Intervention for First-Time Hearing Aid Users: Combining Theoretical and Ecologically Valid Approaches.” International Journal of Audiology 59 (7):492–500. doi:10.1080/14992027.2020.1755063.

- Manchaiah, V., B. Danermark, T. Ahmadi, D. Tomé, F. Zhao, Q. Li, R. Krishna, and P. Germundsson. 2015. “Social Representation of “Hearing Loss”: Cross-Cultural Exploratory Study in India, Iran, Portugal, and the UK.” Clinical Interventions in Aging 10:1857–1872. doi:10.2147/CIA.S91076.

- Marmot, M. 2020. “Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years on.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 368:m693. doi:10.1136/bmj.m693.

- McDermott, J. H., R. Mahood, D. Stoddard, A. Mahaveer, M. A. Turner, R. Corry, J. Garlick, et al. 2021. “Pharmacogenetics to Avoid Loss of Hearing (PALOH) Trial: A Protocol for a Prospective Observational Implementation Trial.” BMJ Open 11 (6):e044457. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044457.

- McDermott, J. H., A. Mahaveer, R. A. James, N. Booth, M. Turner, and K. E. Harvey, & PALOH Study Team. (2022). Rapid point-of-care genotyping to avoid aminoglycoside-induced ototoxicity in neonatal intensive care. JAMA Pediatrics, 176 (5): 486–492. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0187.

- McDermott, J. H., J. Wolf, K. Hoshitsuki, R. Huddart, K. E. Caudle, M. Whirl‐Carrillo, P. S. Steyger, et al. 2022. “Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for the Use of Aminoglycosides Based on MT‐RNR1 Genotype.” Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 111 (2):366–372. doi:10.1002/cpt.2309.

- Miah, J., P. Dawes, I. Leroi, S. Parsons, and B. Starling. 2018. “A Protocol to Evaluate the Impact of Involvement of Older People with Dementia and Age-Related Hearing and/or Vision Impairment in a Multi-Site European Research Study.” Research Involvement and Engagement 4 (1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s40900-018-0128-9.

- Miah, J., P. Dawes, I. Leroi, B. Starling, K. Lovell, O. Price, A. Grundy, and S. Parsons. 2020. “Evaluation of a Research Awareness Training Programme to Support Research Involvement of Older People with Dementia and Their Care Partners.” Health Expectations 23 (5):1177–1190. doi:10.1111/hex.13096.

- Miah, J., S. Parsons, K. Lovell, B. Starling, I. Leroi, and P. Dawes. 2020. “Impact of Involving People with Dementia and Their Care Partners in Research: A Qualitative Study.” BMJ Open, 10 (10):e039321. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039321.

- Milton, D. E. 2012. “On the Ontological Status of Autism: the ‘Double Empathy Problem’.” Disability & Society 27 (6):883–887. doi:10.1080/09687599.2012.710008.

- National Insitute of Health Research. 2021. “Briefing Notes for Researchers - Public Involvement in NHS, Health and Social Care Research.” https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/briefing-notes-for-researchers-public-involvement-in-nhs-health-and-social-care-research/27371#:∼:text=NIHR%20defines%20public%20involvement%20in,that%20influences%20and%20shapes%20research.

- National Institute for Health Research. 2019. “Taking Stock – NIHR Public Involvement and Engagement.” https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/taking-stock-nihr-public-involvement-and-engagement/20566

- Plack, C. J., A. Léger, G. Prendergast, K. Kluk, H. Guest, and K. J. Munro. 2016. “Toward a Diagnostic test for Hidden Hearing Loss.” Trends in Hearing 20:233121651665746. doi:10.1177/2331216516657466.

- Public Involvement Impact Assessment Framework (PiiAF). 2022. https://piiaf.org.uk/

- Regan, J., P. Dawes, A. Pye, C. J. Armitage, M. Hann, I. Himmelsbach, D. Reeves, Z. Simkin, F. Yang, and I. Leroi. 2017. “Improving Hearing and Vision in Dementia: Protocol for a Field Trial of a New Intervention.” BMJ Open 7 (11):e018744. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018744.

- Staley, K. 2017. “‘Changing What Researchers’ Think and Do’: Is This How Involvement Impacts on Research?” Research for All 1 (1):158–167. doi:10.18546/RFA.01.1.13.[Mismatch[Mismatch

- Staniszewska, S., J. Brett, I. Simera, K. Seers, C. Mockford, S. Goodlad, D. G. Altman, et al. 2017. “GRIPP2 Reporting Checklists: Tools to Improve Reporting of Patient and Public Involvement in Research.” Research Involvement and Engagement 3 (1):13. doi:10.1186/s40900-017-0062-2.

- Sturrock, A., H. Guest, G. Hanks, G. Bendo, C. Plack, and E. Gowen. 2022. “Chasing the Conversation: Autistic Experiences of Speech Perception.” Autism and Developmental Language Impairments 7:23969415221077532. doi: 10.1177/2396941522107753.

- Taylor, H., P. Dawes, D. Kapadia, N. Shryane, and P. Norman. 2021. “Investigating Ethnic Inequalities in Hearing aid use in England and Wales: A Cross-Sectional Study.” International Journal of Audiology :1–11. doi:10.1080/14992027.2021.2009131.

- Watts, G. 2020. “COVID-19 and the Digital Divide in the UK.” The Lancet. Digital Health 2 (8):e395–e396. doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30169-2.

- Wolski, L., I. Leroi, J. Regan, P. Dawes, A. P. Charalambous, C. Thodi, J. Prokopiou, et al. 2019. “The Need for Improved Cognitive, Hearing and Vision Assessments for Older People with Cognitive Impairment: A Qualitative Study.” BMC Geriatrics 19 (1):1–12. doi:10.1186/s12877-019-1336-3.

- World Health Organization. 2015. “Hearing Loss Due to Recreational Exposure to Loud Sounds: A Review.” https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/154589/9789241508513_eng.pdf