Abstract

Objectives

The lived experience of tinnitus has biopsychosocial characteristics which are influenced by sociocultural factors. The main purpose of this study is to investigate how tinnitus affects people in their everyday life in China. A deductive qualitative analysis examined whether an a priori Western-centric conceptual framework could extend to an Asian context.

Design

A large-scale prospective survey collected patient-reported problems associated with tinnitus in 485 adults attending four major ENT clinics in Eastern and Southern mainland China.

Results

The evidence suggests that patients in China express a narrower range of problem domains associated with the lived experience of tinnitus. While 13 tinnitus-related problem domains were confirmed, culture-specific adaptations included the addition uncomfortable (a novel concept not previously reported), and the potential exclusion of concepts such as intrusiveness, loss of control, loss of peace and loss of sense of self.

Conclusions

The sociocultural context of patients across China plays an important role in defining the vocabulary used to describe the patient-centred impacts of tinnitus. Possible explanatory factors include cultural differences in the meaning and relevance of certain concepts relating to self and in help-seeking behaviour, low health literacy and a different lexicon in Chinese compared to English to describe tinnitus-related problems.

Introduction

As audiological research becomes more transnational and “connected health” enables delivery of services to remote communities (Chung et al. Citation2014; Glista et al. Citation2021), cross-cultural awareness becomes increasingly relevant and important. For Audiology, cross-cultural awareness refers to how people view hearing loss including perceptions about aetiology, psychological impacts, activity limitations and wider relationships within society (Germundsson et al. Citation2018). Cross-cultural similarities and differences have global clinical implications because condition-specific characteristics that are constant across countries could benefit from the same approaches to assessment and management, while important differences highlight what clinical approaches need to be tailored to the cultural context.

A systematic review recently indicated that about 5–43% of the world’s population experience tinnitus (McCormack et al. Citation2016), and in China, hearing-related conditions contribute to one of the top three causes of years lived with disability (Zhou et al. Citation2019). Audiology is a relatively new and rapidly developing field in China with most hearing healthcare services developed in the past 30 years (Chung et al. Citation2014). This provides a context for the growing interest in evidence-based clinical practice. However, tinnitus remains challenging to manage in all countries because those conditions tend to be idiopathic, chronic and not amenable to a singularly effective medical management approach (Baguley, McFerran, and Hall Citation2013).

An international group of experts recently worked together to articulate a common definition of tinnitus, namely “the conscious awareness of a tonal or composite noise for which there is no identifiable corresponding external acoustic source” (De Ridder et al. Citation2021, 16). For some individuals, this can be “associated with emotional distress, cognitive dysfunction, and/or autonomic arousal, leading to behavioural changes and functional disability” (De Ridder et al. Citation2021, 16). Notwithstanding the difficulties in achieving a global consensus on what tinnitus is, three further challenges to transnational tinnitus research can be summarised as follows; (i) The lived experience of tinnitus from a patient’s perspective is under-investigated and the limited work to date is Western-centric; (ii) Patient-reported questionnaires measuring tinnitus originate largely from the USA and Europe and so may have inadequate cross-cultural equivalence if simply translated into other languages and finally, (iii) Different notions of tinnitus-related complaints would suggest that management interventions developed in one country may not transfer effectively into the healthcare system of another country. This may be especially true for psychologically informed strategies that address negative thoughts, feelings and behaviours about tinnitus (c.f. Germundsson et al. Citation2018).

The first challenge acknowledges that tinnitus is not a physical disease, but rather it is a symptom that has different perceptual, functional and emotional characteristics from person to person (Baguley, McFerran, and Hall Citation2013). In 2018, a comprehensive narrative synthesis of the literature evaluated symptoms assessed in 16,381 patients, and the findings defined 42 discrete complaints spanning negative (perceptual) attributes of the tinnitus sound, physical health problems, functional difficulties, emotional complaints associated with tinnitus-related distress, negative thoughts about tinnitus, general mood states and quality of life (Hall, Fackrell et al. Citation2018). Many of these complaints were solicited by open format questions, such as “Why is tinnitus a problem to you?”. Researchers have highlighted the value of open-ended questions in identifying additional elements relating to life effects that are not so well captured by conventional questionnaires (Manchaiah, Andersson, et al. Citation2022). However, such important qualitative data contributed only 4.6% (n = 748 patients) to the review (Hall et al. Citation2018), and all three of these studies were UK based (Tyler and Baker Citation1983; Sanchez and Stephens Citation1997; Manchaiah et al. Citation2018; Manchaiah, Nisha, et al. Citation2022).

Since then, Watts et al. (Citation2018) have confirmed many of the same patient reported complaints, again in a UK sample. However, several new concepts also emerged from their qualitative study, notably the loss of sense of self, loss of control and feeling deficient due to tinnitus, as well as an explicit desire for knowledge. The participants contributing to this study were 678 first appointment interviews in a specialist private (tertiary) clinic based in London. This group would more likely comprise high income individuals with high expectations about life satisfaction, and so how representative are these concepts to other groups or societies remains uncertain.

In the context of tinnitus, symptoms are largely influenced by environmental, personal and social factors such as lifestyle, family support and wider societal norms and cultural beliefs. These are encapsulated within the biopsychosocial model of health (World Health Organization Citation2001; Gurung Citation2014). It is notable that from the 84 studies that contributed to Hall et al.’s (Citation2018) narrative synthesis, only one was conducted in China (Meng et al. Citation2016) and this examined tinnitus through a Western lens by developing a Mandarin version of the Tinnitus Questionnaire (Hallam, Jakes, and Hinchcliffe Citation1988). This leads into the second challenge regarding tinnitus assessment. There are numerous questionnaires for measuring tinnitus symptom severity for diagnostic and outcome measurement, all of which largely originate from North America and Western Europe. Questionnaires are popular in clinical practice in China because the large number of tinnitus patients attending otology outpatient clinics makes it challenging to implement time-consuming history-taking and other individualised assessments (Chen et al. Citation2021). Here there is a general preference for translating existing English-language questionnaires. For example, the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI, Newman, Jacobson, and Spitzer Citation1996) has been translated into Mandarin (Meng et al. Citation2012; Wu et al. Citation2018), while the Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI, Meikle et al. Citation2012) has been translated into Cantonese (Kam et al. Citation2018) and Mandarin (Wang et al. Citation2020; Xin et al. Citation2023). It should be noted that different questionnaires emphasise different tinnitus problem domains. For example, THI asks about problems with function, emotion and catastrophising, while the TFI asks about problems with intrusiveness, sense of control, cognition, sleep, auditory, relaxation, quality of life and emotional impact of tinnitus. No matter how good the translation however, these tools are appropriate for assessing tinnitus in the Chinese population only if they have good content validity (Terwee et al. Citation2018). This means that the questionnaire items are relevant for construct of tinnitus in Chinese culture and that all of the key concepts are covered by the items. Until we better understand the lived experience of tinnitus in China, including the most common tinnitus-related complaints, it is uncertain whether these Western-developed questionnaires are well-suited for applications in China, and elsewhere.

The main purpose of this study is to investigate how tinnitus affects people in their everyday life in China. A deductive approach to qualitative data analysis used 18 prior domains of tinnitus-associated problems (c.f. Watts et al. Citation2018) as preconceived categories in order to extend the Western-centric conceptual framework into an Asian context. The work is reported according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (O'Brien et al. Citation2014). Findings will add new insight into cross-cultural comparisons in the construct of tinnitus, with important implications for patient assessment and management, as well as for transnational research.

Materials and methods

This study was a prospective survey collecting patient-reported symptoms of tinnitus in patients attending four major ENT clinics in Eastern mainland China between 2018 and 2019. Clinical centres received local ethical approvals to conduct the study according to the same study protocol, and all patients gave informed consent to participate.

Eligible participants were men and women aged ≥18 years, attending a consultation in the ENT clinic, with tinnitus as a primary complaint. Participants were required to have a sufficient command of Chinese Mandarin to give written informed consent and to read, understand and complete written questions. Patients were not reimbursed for their participation.

The study endpoint was pre-defined as 12 months from study opening or when 680 patients had been recruited, whichever came first. The target of 680 was not based on any calculation of statistical power to detect a primary hypothesis, but rather it was a pragmatic decision based on the convenience sample size of one of the studies reported above (Watts et al. Citation2018).

The questionnaire comprised items taken from the Tinnitus and Hyperacusis Initial Interview Form (Jastreboff Citation2011) and reported by Watts et al. (Citation2018). All items were translated into Chinese language by a bilingual speaker who was fluent in both languages (the last author). Supplementary Appendix 1 reports the questionnaire in its original English language form and in its translated version into Chinese Mandarin.

The main question of interest was the open question (Q1) in which the clinician asked patients to describe the main reason(s) why their tinnitus is a problem, in one sentence. In Chinese this question translated to: “请用一句话告诉我为什么您的耳鸣是一个问题”. Patients were free to give any response, and the clinician audio recorded the exact wording of patients’ responses for later data verification, if required. Audio recordings were transcribed into written text by the local clinical team.

The questionnaire included 13 additional closed questions which could either be administered by the clinician, or self-completed by the patient. Questions were focussed on demographic information (age, gender), tinnitus characteristics (laterality, onset, fluctuating, percentage awareness and annoyance), previous tinnitus treatments (if yes, how many) and current hearing aid use. Patients were also asked to rate severity over the past month by allocating a score from 0 (not a problem at all) to 10 (very big problem). This rating question was asked separately for tinnitus, hearing and ability to tolerate the loudness of everyday sounds.

To ensure data integrity, the data corresponding to the first 10 consented patients at each centre was evaluated by the first author. Guidance was provided to ensure that all four centres asked the question using the same wording and recorded answers using consistent response options. All responses were transferred into a single excel spreadsheet for coding and analysis. The closed questions were analysed using descriptive statistics. The responses to the open question (Q1) were evaluated using directed content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). For this qualitative data analysis, the patients’ responses were translated into English because only the first author on the team had experience in content analysis, and she was not a Chinese speaker. A second independent coder was enlisted from the study team that published Watts et al. (Citation2018). This enabled consistency in coding approach and ensured that any problem domain common to the two studies achieved conceptual equivalence (ie described the same kind of reported problems). The two coders worked on the first half of the data (265 patients) by independently reading and re-reading the responses to familiarise themselves with the dataset and then by extracting all meaningful units of information (problem codes) from each response. Problem codes comprised a whole or part sentence as long as it pertained to one topic and contained sufficient information to describe why tinnitus was perceived as a problem. Overall, 410 distinct problem codes were generated through this process. The two coders then compared their problem codes and any coding discrepancies were discussed and resolved. Finally, these problem codes were independently categorised according to the 18 predetermined problem domains (Watts et al. Citation2018). Again, the two coders compared their categorisation and any discrepancies were discussed and resolved. The two coders could not agree on the conceptual distinction between emotional reactions and emotional consequences and so these two categories were combined,1 thus reducing the conceptual framework to 17 categories. Fifty-four problem codes did not readily fit into the predetermined categories (eg “我感觉很不舒服, feel very uncomfortable”, “就没以前睡的那么舒适了, not as comfortable as before”. This led to the addition of a new problem domain labelled uncomfortable. Across the two coders, there was 83% agreement (221 out of 265 responses2) and so because of such high agreement, the first author continued to code the remainder of the dataset alone. All coding was reviewed by the last author.

There is good evidence that data saturation was reached. In the second wave of data coding, all problem codes fit into the categories that had already been supported by the first wave of data coding with the exception of one problem code (mentioned by only one patient) that fit into Watt et al.’s problem domain feeling deficient due to tinnitus (ie a person’s feeling they are somehow less perfect or damaged because they have tinnitus, Hoare personal communication).

Results

Participants

In total, 512 patients gave informed consent, but five patients were excluded because they were below 18 years of age. There were minimal missing responses (0.02%) to the closed questions. A further 22 patients were excluded from the qualitative analysis (n = 3 due to missing data, n = 4 due to being unable to describe a problem, and n = 15 describing a problem that was unrelated to tinnitus or contained no meaningful information).

The closed background questions helped to understand the general clinical characteristics of the patient sample (). Of the included 507 patients, the mean age was 45.7 years (SD = 14.7) and just over a half were women (59%, n = 297/507). Fifty-five percent reported unilateral tinnitus (n = 280/507), 39% reported bilateral tinnitus (n = 200/507), and a further 5% reported perceiving tinnitus inside the head (n = 27/507). Just under half reported fluctuating3 tinnitus (39%, n = 200/507) and just over half reported sudden onset tinnitus (56%, n = 283/507).

Table 1. Summary of patient responses across the four recruitment centres.

The overall mean problem rating for tinnitus was 6.32 (SD = 2.50). The problem ratings confirmed that tinnitus was the primary complaint for the majority of patients, compared to hearing loss (M = 3.08, SD = 3.31) or reduced sound tolerance (M = 3.26, SD = 3.29) [F(1.84, 917.63) = 201.25, p < .001]. As expected, tinnitus awareness and annoyance were positively correlated with the perceived size of the tinnitus problem [r(503) = .39, p < .001 and r(501) = .50, p < .001, respectively].

Less than 2% of the sample were hearing aid users (n = 8/507), but over 60% had previously sought treatment for their tinnitus (n = 308/507). Of those, most had tried one or two treatments (n = 274).

The patient samples were broadly comparable across centres. The only differences were in a larger proportion of women than men recruited at the clinical centre in Shanghai [χ2 (3, N = 507) = 9.84, p = .02] and a greater proportion of patients at the clinical centre in Nangjing who had received previous tinnitus treatments due to the local referral system [χ2 (3, N = 507) = 21.63, p < .001]. These differences are not expected to bias the main findings.

Reported tinnitus-related problems

Of the 485 patients contributing to the directed content analysis, 252 reported only one tinnitus-related problem, 185 reported two problems, 42 reported three problems and 6 reported four problems.

The 772 problem codes were classified according to the 17 predetermined categories, plus the novel category uncomfortable (see ). Supporting evidence was found for 13 of the predetermined categories (ie Annoyance, Constant awareness, Effect on listening, Effect on sleep and alertness, Emotional reactions and consequences, Fear, Feeling deficient due to tinnitus, Inability to concentrate, Need for knowledge, Loss of quiet, Physical effects of tinnitus, Reduced quality of life and Unpleasantness of percept). The most commonly reported complaint was the effect of tinnitus on sleep and alertness (n = 201/485, 41% of patients). The nature of the perceived impacts of tinnitus included difficulties “falling asleep”, reduced “amount of sleep” and reduced “quality of sleep”. Emotional reactions and consequences were also frequently described (n = 144/485, 30% of patients). Many patients did not expand on further details but merely stated that tinnitus affected their “emotions” or “mood”. Those responses which did convey more specific details described feeling “disturbed”, “anxious”, “nervous”, “upset”, “depressed” and “stressed”. They also included utterances that were coded as annoyance, mostly those using the descriptors “annoyed/annoying” or “irritated/irritating”. The category feeling deficient due to tinnitus had only one supporting problem code (“While others will not be able to hear it, I can, making me feel different, I feel that I have a disease”.). No supporting evidence was found for the remaining 4 of the predetermined categories (ie intrusiveness, loss of control, loss of peace and loss of sense of self).

Table 2. Domains of tinnitus-reported complaints and illustrative examples as translated from the original Chinese.

Regarding the novel category, the term uncomfortable was mentioned in all utterances (eg “feel uncomfortable”, “it is very uncomfortable”). In most cases, uncomfortable indicated a physical feeling like being unwell or feeling strange. However, there is no straightforward translation from Chinese into English since this word can be used in Chinese to describe a range of experiences associated with oneself as well as the external environment. A couple of patients described specific uncomfortable situations (ie “uncomfortable when eating” and “my ear feels uncomfortable”).

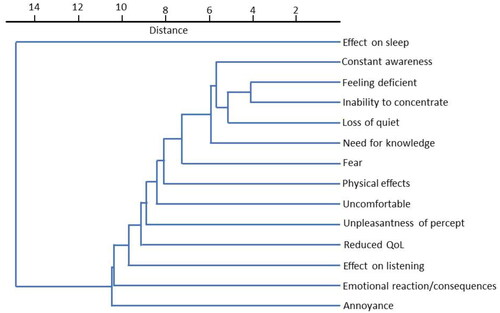

Cluster analysis confirmed the independence of the 14 problem domains (). The smaller the Euclidean distance between categories, the more common it was for the problem domains to be reported together by the same patient. Feeling deficient due to tinnitus and inability to concentrate were reported together, but only by one patient. Next most commonly were reported together were inability to concentrate and loss of quiet. Effect on sleep and annoyance were least often reported together.

Discussion

The present large-scale study tested whether a Western-centric conceptual framework of tinnitus-related problems could be extended to the Asian context. From a clinical sample of 485 patients across Eastern mainland China, 14 distinct tinnitus-related problem domains were identified. Results partially confirm the framework proposed by Watts et al. (Citation2018) but suggest refinements through the addition of a novel concept uncomfortable, and the potential exclusion of intrusiveness, loss of control, loss of peace and loss of sense of self. Overall, the evidence suggests that patients in China express a narrower range of problem domains associated with the lived experience of tinnitus. Three possible explanations for this are considered, namely: (i) cultural differences in the meaning and relevance of certain concepts and in help-seeking behaviour, (ii) low health literacy in the sample of patients or (iii) reduced lexicon in Chinese compared to English to describe tinnitus.

Cross-cultural differences

A widely held belief is that people living in Asia inhibit personal autonomy more so than their counterparts in individualistic (ie WEIRD) societies. This stereotypical notion has some truth since the Confucian perspective promotes a communal understanding of the self. Therefore ideas that stem from an individualistic perception of self (eg loss of control, loss of sense of self) may not be conceptually equivalent across cultures. For example, in order to experience a loss of control, individuals need to have a sense of agency and personal responsibility for applying adaptive coping strategies. Based on our sample of patients in China, responses indicate that individuals are more likely to express their concerns about the physical, emotional and functional impacts of tinnitus, than about self-management. This may be influenced by the medical system in China which leads many patients to expect a medical cure, rather than being expected to play a more active role in the clinical management process.

This is not the first evidence that calls into question the conceptual uniqueness of tinnitus-related sense of control in China. Two psychometric evaluations of Chinese versions of the TFI have also independently highlighted the same issue. One study reported Confirmatory Factor Analysis results showing low factor loadings for two items from the sense of control subscale (Kam et al. Citation2018). The other study identified a single factor, using Exploratory Factor Analysis, which put together two items from the original sense of control subscale with three items from the original intrusiveness subscale (Wang et al. Citation2020). It is interesting to note that the findings by Kam et al. (Citation2018) also raise a question about the relevance of tinnitus intrusiveness as a concept in China since they also reported low factor loadings for two items from the intrusiveness subscale of the TFI.

Low health literacy

If patients are not aware of the range of tinnitus impacts or of the different management strategies to alleviate tinnitus symptoms, then they may not think to mention these when asked. There is little published research on literacy about tinnitus, but a small body of literature does confirm a shortage of knowledge regarding hearing loss treatment and rehabilitation among Chinese adults. For example, patients’ top three reasons for lack of uptake are feeling that it is unnecessary, not understanding its function and not being able to afford it (He et al. Citation2018). Interestingly, from this population-based survey of 1503 hearing-aid candidates in China, the most common reason for lack of uptake was not understanding hearing-aid function. This result contrasts with the perspective in North America where inconvenience replaced lack of understanding in the top three (Fischer et al. Citation2011).

In China, severity of hearing loss and geographical location also play a role in treatment uptake. Those with severe hearing loss are more likely to wear hearing aids compared with mild hearing loss cases, while urban dwellers tend to cite not needing a hearing aid as the most likely reason, but rural inhabitants were more likely to lack understanding about device function (He et al. Citation2018). In the current study, where patients reported fewer problems with hearing loss and the recruiting clinics were in urban centres, it is reasonable to infer that there is low health literacy about the potential benefits of amplification and sound therapy devices for tinnitus management (c.f. Sereda et al. Citation2018).

Reduced lexicon

According to a recent survey of the international vocabulary used to describe tinnitus, just two phrases were suggested in Chinese language (嗡嗡声 humming, 像机器轰鸣 like the roar of a machine and 像电流声 like an electric current), compared to 70 in English (Baguley et al. Citation2022). This observation highlights large discrepancies in the choice of descriptors, according to language. A good example is intrusiveness where in UK datasets, tinnitus has often been described by patients as “intrusive”, “invasive” or “interfering” (Baguley et al. Citation2022; Watts et al. Citation2018), but for which there is no consistent semantic equivalence in common usage in China. The meaning of “intrusiveness” (a subscale of the TFI) in Chinese is 侵扰 (intrusion) which has a strongly negative connotation. Therefore, the intrusiveness subscale of the TFI has been translated into Chinese as 干扰 (interference) which conveys more moderate undertones (Xiang, Zheng, and Lu Citation2020; Wang et al. Citation2020).

In Chinese language, there are comparatively fewer words to describe personal thoughts and feelings than in English. For example, while inner peace and harmony are low-arousal positive emotions that Chinese people generally value (Tsai, Knutson, and Fung Citation2006), loss of peace does not substantially differ in meaning from loss of quiet. In contrast, in the English language, Watts and colleagues made a clear distinction between loss of peace (destruction of the sensation of inner peace, feeling prevented from finding inner peace, or denied peace of mind) and loss of quiet (feeling it is never quiet in one’s head, not being able to listen to silence).

It is also possible that the patients in China have access to less information about tinnitus than their Western counterparts, and this may contribute to their more limited vocabulary. Certainly, there are fewer specialist tinnitus clinics and patient organisations in China than in western countries. In support of this idea, a recent study conducted in the ENT Department, Foshan, China noted that many patients receiving treatment for tinnitus admitted to a lack of knowledge about the condition (Lan, Zhao, and Xiong Citation2022).

A reduced lexicon can perhaps also offer an explanation for the novel category uncomfortable. Uncomfortable is a catch-all term that Chinese people use often to describe a range of different feelings in a range of situations. Specifically, it can describe various health-related issues (such as not feeling right, being tired, feeling cold or hot), and it applies equally to describe internal (physical or mental) sensations of being unwell and to describe an unpleasant (external) environment. Uncomfortable is therefore a natural choice to describe tinnitus in Chinese language because tinnitus is a subjective experience without any objectively measurable symptoms.

Future directions

This research has important implications where transnational studies seek to make direct comparisons between participants from different cultures. A number of key concepts related to the lived experience of tinnitus do not have equal relevance in Western and Chinese cultures, yet some of these are assessed by English-language questionnaires that have been translated into Chinese for diagnostic and outcome measurement of tinnitus symptom severity. It is unclear to what extent the existing translations of tinnitus questionnaires into Chinese language have explicitly considered the equivalence, accessibility and acceptability of wording (Kam et al. Citation2018; Meng et al. Citation2012; Wang et al. Citation2020; Wu et al. Citation2018; Xin et al. Citation2023). Importantly, our findings highlight a need to consider potential culturally specific refinements to some of the western-centric items in these tinnitus questionnaires. One proposal is to conduct Qualitative Pre-test Interviews (Buschle, Reiter, and Bethmann Citation2022). This approach shares some similarities with the field testing stage of the translation guide published in this journal (Hall et al. Citation2018), but emphasises exploration of the intended meaning of each questionnaire item and deliberation on potential improvements from the participant’s perspective.

Conclusions

This study contributes to understanding the lived experiences of people with tinnitus in China as an example of an important under-studied population. Western concepts describing tinnitus-related problems such as intrusiveness, loss of control, loss of peace and loss of sense of self may have poor conceptual equivalence in Asian countries, while uncomfortable was introduced to the lexicon. The narrower range of problem domains associated with the lived experience of tinnitus in this Asian country was observed even though the sample most probably comes from the more educated and wealthier levels of society. Notably, Shanghai, Nanjing, Ningbo and Zhuhai are all prosperous cities, with several of the recruiting centres being well-known ENT departments that attract patients from a wide geographical radius. Further research is required to better understand the main constructs of tinnitus in Chinese culture. Collaboration between scholars in Western countries and Asia could be particularly fruitful in this regard especially if there is a co-creation of new knowledge about cross-cultural differences in the lived experience of tinnitus.

Notes

In discussion with another of the authors of the article by Watts et al. (Citation2018).

For the remaining 45 responses, 41 were judged to be better coded using one of the coder’s scheme (23 to the first author and 17 to the second coder), and 4 combined multiple problem domains across coders.

In Chinese language, as in English, fluctuating can refer to variations in tinnitus presence or to variations in tinnitus loudness (or indeed any other perceptual characteristics).

Author contributions

Conception: DAH; Study design: DAH and FZ (especially Chinese translation); Execution: All authors; Acquisition of data: BX, WL, YW, XZ were responsible for data collection, DAH evaluated data integrity; Analysis: DAH (qualitative analysis) and FZ (quantitative analysis); Interpretation: DAH, BX, YW and FZ.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (47.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sandra Smith for assistance with content analysis and Dr Kathryn Fackrell for helpful discussion on the conceptual distinction between emotional reactions and emotional consequences. Interim findings were presented at the 12th Tinnitus Research Initiative conference in Taipei in 2019.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baguley, D., D. McFerran, and D. Hall. 2013. “Tinnitus.” Lancet 382 (9904):1600–1607. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60142-7.

- Baguley, D. M., C. Caimino, A. Gilles, and L. Jacquemin. 2022. “The International Vocabulary of Tinnitus.” Frontiers in Neuroscience 16:887592. doi:10.3389/fnins.2022.887592.

- Buschle, C., H. Reiter, and A. Bethmann. 2022. “The Qualitative Pretest Interview for Questionnaire Development: Outline of Programme and Practice.” Quality & Quantity 56 (2):823–842. doi:10.1007/s11135-021-01156-0.

- Chen, Z., Y. Zheng, Y. Fei, D. Wu, and X. Yang. 2021. “Validation of the Mandarin Tinnitus Evaluation Questionnaire: A Clinician-administered Tool for Tinnitus Management.” Medicine 100 (27):e26490. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000026490.

- Chung, K., B. Y. Ma, M. W. P. Cui, S. F. Wang, and F. Xu. 2014. “A Hearing Report from China.” Audiology Today, May/June, 42–53. https://www.audiology.org/

- De Ridder, D., W. Schlee, S. Vanneste, A. Londero, N. Weisz, T. Kleinjung, G. S. Shekhawat, et al. 2021. “Tinnitus and Tinnitus Disorder: Theoretical and Operational Definitions (an International Multidisciplinary Proposal).” Progress in Brain Research 260:1–25. doi:10.1016/bs.pbr.2020.12.002

- Fischer, M. E., K. J. Cruickshanks, T. L. Wiley, B. E. Klein, R. Klein, and T. S. Tweed. 2011. “Determinants of Hearing Aid Acquisition in Older Adults.” American Journal of Public Health 101 (8):1449–1455. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2010.300078.

- Germundsson, P., V. Manchaiah, P. Ratinaud, A. Tympas, and B. Danermark. 2018. “Patterns in the Social Representation of “Hearing Loss” across Countries: How Do Demographic Factors Influence This Representation?” International Journal of Audiology 57 (12):931–938. doi:10.1080/14992027.2018.1516894.

- Glista, D., M. Ferguson, K. Muñoz, and E. Davies-Venn. 2021. “Connected Hearing Healthcare: Shifting from Theory to Practice.” International Journal of Audiology 60 (Sup1):S1–S3. doi:10.1080/14992027.2021.1896794.

- Gurung, R. A. R. 2014. Health Psychology: A Cultural Approach. Belmont: Wadsworth.

- Hall, D. A., K. Fackrell, A. B. Li, R. Thavayogan, S. Smith, V. Kennedy, C. Tinoco, et al. 2018. “A Narrative Synthesis of Research Evidence for Tinnitus-related Complaints as Reported by Patients and Their Significant Others.” Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 16 (1):61. doi:10.1186/s12955-018-0888-9.

- Hall, D. A., S. Zaragoza Domingo, L. Z. Hamdache, V. Manchaiah, S. Thammaiah, C. Evans, and L. N. Wong. 2018. “A Good Practice Guide for Translating and Adapting Hearing-related Questionnaires for Different Languages and Cultures.” International Journal of Audiology 57 (3):161–175. doi:10.1080/14992027.2017.1393565.

- Hallam, R. S., S. C. Jakes, and R. Hinchcliffe. 1988. “Cognitive Variables in Tinnitus Annoyance.” The British Journal of Clinical Psychology 27 (3):213–222. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8260.1988.tb00778.x.

- He, P., X. Wen, X. Hu, R. Gong, Y. Luo, C. Guo, G. Chen, and X. Zheng. 2018. “Hearing Aid Acquisition in Chinese Older Adults with Hearing Loss.” American Journal of Public Health 108 (2):241–247. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.304165.

- Hsieh, H. F., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9):1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Jastreboff, P. J. 2011. “Tinnitus Retraining Therapy.” In Textbook of Tinnitus, edited by A. R. Møller, B. Langguth, D. De Ridder, and T. Kleinjung, 575–596. New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-145-5_73.

- Kam, A. C. S., E. K. S. Leung, P. Y. B. Chan, and M. C. F. Tong. 2018. “Cross-cultural Adaptation and Psychometric Properties of the Chinese Tinnitus Functional Index.” International Journal of Audiology 57 (2):91–97. doi:10.1080/14992027.2017.1375162.

- Lan, T., F. Zhao, and B. Xiong. 2022. “The Acceptability and Influencing Factors of an Internet-based Tinnitus Multivariate Integrated Sound Therapy for Patients with Tinnitus.” Ear, Nose, & Throat Journal 101 (10):680–689. doi:10.1177/0145561320973768.

- Manchaiah, V., G. Andersson, M. A. Fagelson, R. L. Boyd, and E. W. Beukes. 2022. “Use of Open-ended Questionnaires to Examine the Effects of Tinnitus and Its Relation to Patient-reported Outcome Measures.” International Journal of Audiology 61 (7):592–599. doi:10.1080/14992027.2021.1995790.

- Manchaiah, V., E. W. Beukes, S. Granberg, N. Durisala, D. M. Baguley, P. M. Allen, and G. Andersson. 2018. “Problems and Life Effects Experienced by Tinnitus Research Study Volunteers: An Exploratory Study Using the ICF Classification.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 29 (10):936–947. doi:10.3766/jaaa.17094.

- Manchaiah, V., K. V. Nisha, P. Prabhu, S. Granberg, E. Karlsson, G. Andersson, and E. W. Beukes. 2022. “Examining the Consequences of Tinnitus Using the Multidimensional Perspective.” Acta Oto-Laryngologica 142 (1):67–72. doi:10.1080/00016489.2021.2019307.

- McCormack, A., M. Edmondson-Jones, S. Somerset, and D. Hall. 2016. “A Systematic Review of the Reporting of Tinnitus Prevalence and Severity.” Hearing Research 337:70–79. doi:10.1016/j.heares.2016.05.009.

- Meikle, M. B., J. A. Henry, S. E. Griest, B. J. Stewart, H. B. Abrams, R. McArdle, P. J. Myers, et al. 2012. “The Tinnitus Functional Index: Development of a New Clinical Measure for Chronic, Intrusive Tinnitus.” Ear and Hearing 33 (2):153–176. doi:10.1097/AUD.0b013e31822f67c0.

- Meng, Z., Z. Chen, K. Xu, G. Li, Y. Tao, and J. S. Kwong. 2016. “Psychometric Properties of a Mandarin Version of the Tinnitus Questionnaire.” International Journal of Audiology 55 (6):366–374. doi:10.3109/14992027.2016.1146414.

- Meng, Z., Y. Zheng, S. Liu, K. Wang, X. Kong, Y. Tao, K. Xu, and G. Liu. 2012. “Reliability and Validity of Chinese (Mandarin) Tinnitus Handicap Inventory.” Clinical and Experimental Otorhinolaryngology 5 (1):10–16. doi:10.3342/ceo.2012.5.1.10.

- Newman, C. W., G. P. Jacobson, and J. B. Spitzer. 1996. “Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory.” Archives of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery 122 (2):143–148. doi:10.1001/archotol.1996.01890140029007.

- O'Brien, B. C., I. B. Harris, T. J. Beckman, D. A. Reed, and D. A. Cook. 2014. “Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research: A Synthesis of Recommendations.” Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges 89 (9):1245–1251. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388.

- Sanchez, L., and D. Stephens. 1997. “A Tinnitus Problem Questionnaire in a Clinic Population.” Ear and Hearing 18 (3):210–217. doi:10.1097/00003446-199706000-00004.

- Sereda, M., J. Xia, A. El Refaie, D. A. Hall, and D. J. Hoare. 2018. “Sound Therapy (Using Amplification Devices and/or Sound Generators) for Tinnitus.” The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 12 (12):CD013094. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013094.pub2.

- Terwee, C. B., C. A. C. Prinsen, A. Chiarotto, M. J. Westerman, D. L. Patrick, J. Alonso, L. M. Bouter, H. C. W. de Vet, and L. B. Mokkink. 2018. “COSMIN Methodology for Evaluating the Content Validity of Patient Reported Outcome Measures: A Delphi Study.” Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation 27 (5):1159–1170. doi:10.1007/s11136-018-1829-0.

- Tsai, J. L., B. Knutson, and H. H. Fung. 2006. “Cultural Variation in Affect Valuation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90 (2):288–307. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.2.288.

- Tyler, R. S., and L. J. Baker. 1983. “Difficulties Experienced by Tinnitus Sufferers.” The Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders 48 (2):150–154. doi:10.1044/jshd.4802.150.

- Wang, X., R. Zeng, H. Zhuang, Q. Sun, Z. Yang, C. Sun, and G. Xiong. 2020. “Chinese Validation and Clinical Application of the Tinnitus Functional Index.” Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 18 (1):272. doi:10.1186/s12955-020-01514-w.

- Watts, E. J., F. Fackrell, S. Smith, J. Sheldrake, H. Haider, and D. J. Hoare. 2018. “Why Is Tinnitus a Problem? A Qualitative Analysis of Problems Reported by Tinnitus Patients.” Trends in Hearing 22:2331216518812250. doi:10.1177/2331216518812250.

- World Health Organization. 2001. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: WHO. http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/.

- Wu, D., Y. Zheng, Z. Chen, Y. Ma, and T. Lu. 2018. “Further Validation of the Chinese (Mandarin) Tinnitus Handicap Inventory: Comparison between Patient-reported and Clinician-interviewed Outcomes.” International Journal of Audiology 57 (6):440–448. doi:10.1080/14992027.2018.1431404.

- Xiang, T., Y. Zheng, and T. Lu. 2020. “Validation of the Chinese Version of the Auditory Subscale of the Tinnitus Functional Index.” Lin Chuang er bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai ke za Zhi = Journal of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology, Head, and Neck Surgery 34 (7):603–605;609. doi:10.13201/j.issn.2096-7993.2020.07.006.

- Xin, Y., R. Tyler, Z. M. Yao, N. Zhou, S. Xiong, L. Y. Tao, F. R. Ma, and T. Pan. 2023. “Tinnitus Assessment: Chinese Version of the Tinnitus Primary Function Questionnaire.” World Journal of Otorhinolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery 9 (1):27–34. doi:10.1002/wjo2.60.

- Zhou, M., H. Wang, X. Zeng, P. Yin, J. Zhu, W. Chen, X. Li, L. Wang, L. Wang, Y. Liu, et al. 2019. “Mortality, Morbidity, and Risk Factors in China and Its Provinces, 1990-2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017.” Lancet 394 (10204):1145–1158. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30427-1.