Abstract

Objective

With our aging population, an increasing number of older adults with hearing loss have cognitive decline. Hearing care practitioners have an important role in supporting healthy aging and should be knowledgeable about cognitive decline and associated management strategies to maximize successful hearing intervention.

Methods

A review of current research and expert opinion.

Results

This article outlines the association between hearing loss and cognitive decline/dementia, hypothesized mechanisms underlying this, and considers current research into the effects of hearing intervention on cognitive decline. Cognition into old age, cognitive impairment, dementia, and how to recognize cognitive decline that is not part of normal aging are described. Screening of older asymptomatic adults for cognitive decline and practical suggestions for the delivery of person-centered hearing care are discussed. Holistic management goals, personhood, and person-centered care in hearing care management are considered for older adults with normal cognitive aging through to dementia. A case study illustrates important skills and potential management methods. Prevention strategies for managing hearing and cognitive health and function through to older age, and strategies to maximize successful hearing aid use are provided.

Conclusion

This article provides evidence-based recommendations for hearing care professionals supporting older clients to maximize well-being through the cognitive trajectory.

1. Introduction

The process of ageing entails a series of losses and gains in physical, cognitive, psychological, and social abilities. To age well, individuals must adapt to, and compensate for, the changes which may impact speech understanding, a critical part of communication. Declines in speech understanding in difficult listening conditions with increasing age are associated with both normal and elevated hearing threshold levels and with age-related changes in parts of the brain critical to speech understanding (e.g. Peelle et al. Citation2011). Speech understanding involves several complex parallel and sequential processing steps in both hemispheres of the brain, rather than one isolated computation, with neural pathways from the auditory brainstem connected to widely distributed bilateral networks in the temporal and frontal cortices (e.g. Friederici, Citation2012). When listening situations become complex and acoustics are degraded and the signal to noise ratio is unfavourable, multiple neural systems not traditionally regarded as part of the language network are recruited to support speech understanding, including the superior prefrontal and parietal regions (e.g. Alain et al. Citation2018). These parts of the brain are integral to executive function, a set of cognitive skills including adaptable thinking, planning, self-monitoring, self-control, organisation, selective attention and working memory (Diamond, Citation2013). The use of additional cognitive resources for speech understanding may have cognitive and behavioural consequences including loss of resources for other cognitive tasks, listening fatigue, loss of motivation to engage, and withdrawal (Peelle and Wingfield, Citation2016, Pichora-Fuller et al. Citation2016).

1.1. Cognitive ageing

Cognitive ageing is a multidimensional and multidirectional process with enormous inter-individual differences (Baltes, Citation1987). The interaction of various dimensions of physical, mental, emotional, and psychosocial development results in a range of individual trajectories of gains and losses as well as stability throughout life (Wu et al. Citation2020). Individuals vary greatly in the extent, rate, and pattern of age-related cognitive changes experienced (Park et al. Citation2002; Wu et al. Citation2020). Typically, deterioration is observed in cognitive functions such as processing speed, executive functions, and episodic and working memory with ageing (Park et al. Citation2002; Salthouse, Citation2019), though performance levels for other cognitive functions such as language, semantics knowledge, abstract reasoning, and visuospatial ability are usually maintained with increasing age (Park et al. Citation2002; Salthouse, Citation2019). Importantly, there is high variability in cognitive performance in old age; often performance differences between people of the same age are greater than those between people from different age cohorts (Smith and Baltes, Citation1996). Individual variability demands a client-centered approach to management, keeping in mind the key features of brain ageing when working with older adults. Key messages about brain ageing, adapted from the Institute of Medicine, 2015 (The Gerontological Society of America, Citation2020) are:

The brain ages, just like other parts of the body.

Cognitive ageing is not a disease. It is a natural, lifelong process that occurs in every individual.

Cognitive ageing is different for every individual.

Some cognitive functions improve with age (e.g. wisdom learned from experience).

Actions can be taken by individuals to help maintain cognitive health.

1.2. Cognitive impairment and dementia

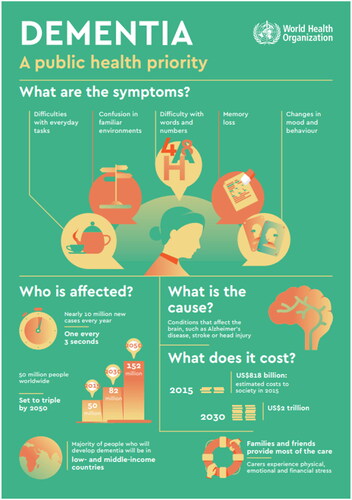

While most people continue to be able to independently manage their daily activities of living as they age, cognitive complaints or difficulties are also common (Tucker-Drob and Salthouse, Citation2011). Typical age-related cognitive changes include a general slowing in information processing speed, reduced working memory capacity, greater effort required for learning new information and for recalling episodes after some delay, and difficulties when processing parallel or interfering information that requires dividing or switching attention (Park et al. Citation2002; Salthouse, Citation2019; Schaie, Citation2005). Many older adults are particularly concerned about memory loss in terms of their own cognitive decline and are equally fearful of both developing dementia and having to care for someone else with dementia (Anderson et al. Citation2009). Dementia is a growing public health concern, as more than 55 million people live with dementia worldwide, and this number is expected to triple by 2050 (Alzheimer’s Association, Citation2021). The prevalence of dementia exponentially increases with age, with rising longevity resulting in an increasing number of affected people. It is estimated that after the age 65 years, dementia risk doubles every five years, with about 10% of the population over the age of 65 years and up to 35% over the age of 85 years affected (Alzheimer’s Association, Citation2021). More of the population is affected by mild cognitive impairment (MCI; 15 − 23% over the age of 65 years (Petersen et al. Citation2018). As dementia tends to be under-recognized/under-diagnosed, hearing care practitioners (HCPs) need to enquire about subjective cognitive complaints and become familiar with symptoms and risk factors associated with cognitive decline and dementia (Mosnier et al. Citation2018).

Dementia, an umbrella term for symptoms associated with progressive, multifactorial and irreversible changes in brain function, is not a part of the normal ageing process. Different types of dementia include, for example, Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, and Lewy Body dementia, each with a disparate group of symptoms (Alzheimer’s Association, Citation2021). Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia and contributes to 60–70% of cases (WHO, Citation2023). While in MCI, impairment may affect one or more cognitive domains but does not interfere with the capacity for independent everyday activities, dementia interferes with independent living, affecting instrumental activities of daily living such as paying bills or managing medications (APA, Citation2013). There is always evidence of significant cognitive decline from a previously attained level of cognitive performance. Dementia also involves not just memory impairment but the impairment of several higher-order cognitive functions (e.g. learning, language, executive function, complex attention, perceptual-motor, and social cognition). Symptoms may also include personality changes and behavioural and emotional problems impacting social functioning (APA, Citation2013).

People with MCI are considered a high-risk group for dementia, and emerging evidence and new diagnostic procedures indicate this also applies to individuals with subjective cognitive decline (SCD), a pre-clinical condition of subjectively experienced persistent decline in cognitive capacity despite normal performance on cognitive tests (Jessen et al. Citation2020). Although SCD is non-specific and can be present with different medical conditions, epidemiological data show that MCI and dementia risk is increased in individuals with SCD (Jessen et al. Citation2020). Self-reported hearing loss has recently been found to be associated with SCD (Jessen et al. Citation2020).

1.3. The association between hearing loss and cognitive decline

The interplay between age-related changes in auditory and cognitive processing during listening and speech understanding has received considerable attention over the past few decades. Epidemiological evidence suggests an association between hearing loss (e.g. 4-frequency pure tone average of 20 dB HL) and poorer executive function affecting working memory in particular and a faster rate of cognitive decline in people with hearing loss (e.g. Taljaard et al. Citation2016). There are also suggestions that central auditory dysfunction is a prodromal feature of dementia (e.g. Tuwaig et al. Citation2017). The recent 2017 and 2020 Lancet Commission reports on dementia prevention have subsequently identified hearing loss as the largest potentially modifiable risk factor for dementia at the population level (Livingston et al. Citation2017, Citation2020), with hearing loss from mid-life increasing that risk. The mechanisms underlying the association between hearing loss and dementia remain unknown, however, there are several mechanistic theories.

Since Baltes and Lindenberger (Citation1997) originally suggested a link between hearing loss and cognitive decline, three main hypotheses have been proposed. The first hypothesis suggests that there is a common neuropathic pathology for both hearing loss and dementia that affects the cochlea and ascending auditory pathway (causing hearing loss) and the cortex (causing dementia). In contrast, the information degradation theory hypothesises that with increased cognitive load due to perceptual difficulties, cognitive resources are diverted towards speech processing rather than working memory and other tasks, leading to decreased performance in other cognitive functions (Baltes and Lindenberger, Citation1997; Peelle and Wingfield, Citation2016). The sensory deprivation theory hypothesises that cognitive decline is caused by reduced environmental stimulation due to hearing loss and subsequent psychological sequalae such as social isolation, depression, and loneliness, known risk factors for dementia (Fulton et al. Citation2015), and that such deprivation could lead to cortical re-allocation, deafferentation and atrophy to support speech perception processing. In line with this, a fourth and more recent hypothesis is that altered cortical brain activity due to hearing loss causes irreversible molecular degenerative damage, (i.e. neurofibrillary changes related to tau pathology in the medial temporal lobe structures; Griffiths et al. Citation2020). It is likely that no one mechanism alone accounts for the link between hearing loss and dementia.

1.4. The effects of hearing interventions on cognitive outcomes for older adults

Given the evidence emerging regarding the association between hearing loss and cognitive decline/dementia, there has been increasing interest in determining whether hearing interventions could impact cognitive function in terms of delaying the onset of dementia, minimising cognitive decline, or even reversing cognitive changes in the brain due to hearing loss. While a recent systematic review concluded that there is still controversy about the effects of hearing aid use on cognition (Sanders et al. Citation2021), a prior meta-analysis investigating the effects of hearing aid use on cognitive decline suggested a significant positive effect of hearing aid use (Taljaard et al. Citation2016). Similarly, the reviews and meta-analyses conducted by the Lancet Commissions (Livingston et al. Citation2020; Livingston et al. Citation2017) have suggested that given the long follow-up times of 9–17 years in the prospective studies included, hearing aid use is more likely to be protective of cognition, rather than that people who are developing dementia are less likely to use hearing aids. In both meta-analyses, three cohort studies met the inclusion criteria of following cognitively healthy people at baseline, having at least a 5-year follow-up period, measuring hearing loss behaviourally, having incident dementia as an outcome, and adjusting for age and cardiovascular risk factors as potential confounding factors.

The data on the effects of hearing aids on cognition are mixed, with significant heterogeneity and methodological limitations. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are difficult to implement methodologically, due to the ethical challenges of withholding hearing intervention for long time periods from the control group with hearing loss or with a high risk of cognitive impairment, however, results of the first RCT on the effect of hearing aid use on cognition have recently been reported (Lin et al.et al. Citation2023). These were equivocal, with a primary outcome of no significant effect on global cognitive performance, and a secondary sensitivity analysis showing a significant reduction in the rate of cognitive decline for hearing aid users from a group of participants with more cognitive decline risk factors. Progress has also been limited by a lack of interdisciplinary collaborations among auditory and cognitive scientists (Lin and Albert, Citation2014). The current World Health Organisation guidelines for risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia state that ‘there is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of hearing aids to reduce the risk of cognitive decline and/or dementia’, rating the quality of the evidence as ‘very low’ (WHO, Citation2019b). However, they also strongly recommend “screening, followed by provision of hearing aids should be offered to older people for timely identification and management of hearing loss” (WHO, Citation2019a, Citation2021).

1.5. How to recognise cognitive decline in clients with hearing loss that is not part of the normal ageing process

HCPs are trusted healthcare providers to older people and are in a unique position to observe and recognise cognitive as well as functional change. Audiology appointments are often longer than physicians’ appointments, with conversations frequently around activities of daily life. Thus, HCPs are potential gatekeepers who can identify cognitive impairment, initiate early diagnostic evaluation, and refer for supportive services. With an ageing population, an increasing number of audiology clients will present with cognitive impairment and may require modification and adaptation of clinical practice. Therefore, HCPs should know and be able to recognise warning signs and early symptoms of cognitive impairment and be able to differentiate these from those of normal cognitive ageing. However, a non-physician HCP cannot diagnose cognitive problems in older adults (Maslow and Fortinsky, Citation2018).

Paying attention to client behaviour and interaction through active listening and observation is important in identifying cognitive problems that may not be part of normal ageing (Maslow and Fortinsky, Citation2018). This may help to identify functional difficulties, behaviour changes, or family concerns that might indicate a cognitive problem. HCPs should notice whether a client is capable of following instructions, appears lost or unreasonable in the conversation, or is repeating the same phrases or questions. The WHO infographic (2019a) illustrates the course of normal cognitive ageing and common symptoms of pathological change in dementia and may assist with recognising such problems.

We highly recommend combining observations with taking notes in client records for follow-up. Many audiology clinics use an intake form to gather client information. This should include an item on potential cognitive problems. The following screening question could be used: “During the past 12 months, have you experienced confusion or memory loss that is happening more often or is getting worse?” (The Gerontological Society of America, Citation2020). The use of screening questions may have limited effectiveness due to a lack of client insight into their own condition, which is common in dementia (McDaniel, Edland, and Heyman, Citation1995). However, when provided, we recommend such information should be used to open a conversation about the interdependency of cognition and hearing as well as any cognitive difficulties a client may be experiencing (e.g. “On the intake form we asked about your memory; this is because cognition and hearing are closely linked to each other; if it is hard to hear information then it will also be hard to remember it …”).

It can be difficult to determine whether some behaviours and psychosocial consequences are due to hearing loss or cognitive decline, as many of these are the same (Kricos, Citation2009; Weinstein, Citation1986). It is very important to explicitly ask about, and then follow-up, with a client and their care partners on any reported cognitive problems or concerns (e.g. “Do you have problems with memory or orientation, such as not knowing where you are or what day it is?”). Elaboration on such problems should be encouraged by asking for specific examples or situations or by reflecting on observed or reported difficulties (e.g. “You mentioned a couple of times that you are sometimes forgetful. Could you give me examples of the type of situations in which this occurs?”). To validate our understanding of the problem and to avoid misinterpretation it is helpful to use the client’s own words (e.g. "You are saying that …"). Taking the perspective of the client supports building rapport, as does the provision of clear and straightforward recommendations. Such a recommendation could be: “I am hearing that you are concerned about (use client’s words, e.g. your memory/your ability to think). I think it is very important to get reassurance and a check-up from an expert. Just as you can have a check-up for your heart function, you can also have your brain health checked. The expert will be able to give you information about how to improve your cognitive abilities. There is a lot you can do – including getting your hearing loss treated.” Providing an example of a potentially more familiar physical health problem and its typical check-up procedure can help facilitate the conversation about a potential cognitive problem and build compliance towards its management.

1.6. Should we use screening tests to identify cognitive status in older asymptomatic adults?

The universal hearing screening of older adults and routine screening of cognitive status in general and by audiologists is controversial. While the United States Preventative Services Task Force (Owens et al. Citation2020) states that the evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for cognitive impairment, the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit recommends screening for cognitive status in primary care. Reviews of the current evidence on screening for cognitive impairment, including for MCI and mild-to-moderate dementia in community-dwelling adults, and for asymptomatic adults 65 years or older residing in independent living facilities, have concluded that there is currently insufficient evidence and capacity for efficient universal cognitive screening. The United States Preventative Services Task Force (Patnode et al. Citation2020), and the Canadian Task Force on Preventative Health Care therefore do not currently recommend cognitive screening in asymptomatic adults. Issues to consider for audiologists contemplating cognitive screening include having adequate training and expertise to apply the required consent procedures and administer the assessments, the challenges of correctly interpreting and appropriately communicating the results without excessively alarming the client, interpreting unremarkable screening results (e.g. false reassurance) and the potential harms of this for the client, and knowing what to do with the information after this. Best practice would require an established and appropriate referral pathway offering management and care for those identified by screening as being cognitively impaired (Maslow and Fortinsky, Citation2018). Further, most cognitive screening instruments do not take hearing loss into consideration in delivering task instructions or with memory items. Cognitive capacity may therefore be underestimated in people who cannot hear instructions well, with consequent poorer performance (e.g. Dupuis et al. Citation2015).

A further challenge of cognitive screening is that screening tests generally have a poor ability to identify MCI and only a moderately high ability to identify dementia (e.g. Mini Mental State Examination, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; Tsoi et al. Citation2015). High numbers of false positives are reported except in the highest-risk populations (Tsoi et al. Citation2015). Given the potential loss of autonomy with a positive screen result, some people may refuse to be screened. The effects of false positives can also include significant psychological distress and invasive and expensive follow-up testing. Lastly, cost-benefit considerations must be considered for all screening tests (including hearing screening tests).

The current recommendations have been made considering the above issues but could change in future with a growing ageing population and the development of new screening tools (e.g. based on biomarkers). For example, a recent evaluation of the costs and cost-effectiveness of interventions for some potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia recently found that hearing aid provision was cost-effective for improving health and quality of life, reducing dementia risk, and saving costs (Mukadam et al. Citation2020).

1.7. Proactive hearing care is integral to well-being

The increase in life expectancy coupled with the rising prevalence of age-related hearing loss underscores the importance of hearing care throughout the lifespan, its relevance to integrated care, and the promotion of the importance of ageing well. The UN Decade of Healthy Ageing plan (WHO, Citation2020) proposed preventative care should begin in middle age, not older age, and should continue across the life-course. Given the associations between hearing loss and other age-related health conditions, a proactive health promotion approach to ageing well from middle age, rather than a reactive approach after hearing loss has already caused significant disability, could help to prevent many of the negative consequences of hearing loss in later life. This approach could be adopted with the goal of educating clients and the wider public about the comorbidities of hearing loss and the potential to reduce the risk of modifiable age-related health problems.

1.8. Person-centered care and care partners/significant others

The principles of cognitive rehabilitation underscore that person-centered goal-oriented interventions should be aimed at optimising functional ability, mitigating residual disability and maximising engagement and social participation (Clare et al. Citation2019). Caring for people with dementia entails working with family members, care partners and SOs; key to person-/family-centered, integrated care. Including care partners/family members, educating, sharing information, instructing on technology use, asking for their opinion of a hearing problem and any other changes they have observed in their interactions with the client, can provide a better picture of the client’s functional disabilities and the chances of rehabilitation success. While the person with cognitive impairment must be prioritised, we believe it is equally important to validate concerns expressed by family members. Client, medical and gerontology associations provide a range of quality resources about dementia, assistance for making medical decisions, care pathways, and care partner support. lists desirable minimal competencies for HCPs working with people who may have some degree of cognitive impairment.

Table 1. Minimum HCP competencies for working with people who may have some degree of cognitive impairment.

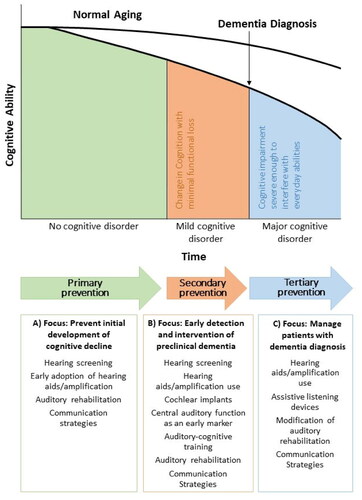

2. Hearing management: a multifaceted approach

Communication can be cognitively demanding for older adults with sensory loss and cognitive issues, and the management of these individuals can pose challenges. Using a preventative public health model to proactively manage people with co-morbid cognitive and hearing loss is consistent with the recommendations of the Lancet Commission (Livingston et al. Citation2020). Prevention includes an array of interventions designed to minimise threats to health at different stages of the hearing loss journey. Social engagement and the use of hearing technologies to contribute to cognitive reserve can be protective, hence social prescribing should be incorporated into our list of recommendations for people with sensory loss and cognitive decline. shows hearing healthcare intervention options by cognitive capacity and preventive hearing healthcare intervention strategies. Primary prevention is aimed at implementing health intervention measures early to forestall the onset of a condition or adverse effects. Secondary prevention is focused on early detection and reducing the impacts of an existing condition to halt or slow its progress, and to encourage strategies to prevent further deterioration. Tertiary prevention entails providing supportive and rehabilitative services to mitigate or prevent a condition from deteriorating further and negatively impacting the quality of life and/or quality of death. Intervention options must be informed by auditory and cognitive status. When remembering things, thinking clearly, and communicating with others become more difficult, the involvement of family members becomes increasingly more important. Considering the threat of third-party disability, incorporating family members, and providing them with non-technological strategies (e.g. education, counselling, and communication training) to help people with co-existing sensory and cognitive decline to stay connected and maintain social relationships, is critical (WHO, 2021d). Throughout the client journey, we must ensure that recommended interventions compensate for impoverished auditory input by reducing listening effort and associated demands on attention, memory, and executive function (Peelle and Wingfield, Citation2016).

Figure 1. Infographic: Dementia, a public health priority, (WHO, Citation2019a).

Figure 2. Intervention options in audiology by cognition trajectory from normal ageing to dementia by a Public Health Prevention Approach; adapted from Powell et al. 2021).

When successful hearing aid use is no longer a realistic option due to either visual/manual dexterity or cognitive issues, alternative technological strategies or non-technology-driven alternatives should be considered to meet auditory and cognitive needs (Pichora-Fuller et al. Citation2013). Personal amplifiers may then provide advantages in terms of signal-to-noise, ease of use, availability, and low cost. We must also set realistic management goals/expectations which should include promoting safety at home. We believe underscoring the importance of hearing aid use at home to ensure the audibility of warning signals such as a smoke alarm, doorbell, or telephone and to ensure sensory stimulation, is a critical contribution we can make on inter-professional teams.

3. Client-centred management goals for people with cognitive decline

Audibility is integral to effective communication and essential to brain health, and when impaired can negatively impact the management goals for people with hearing loss, both with and without cognitive impairment. details management goals for older adults with hearing loss (Jennings et al. Citation2017). It is critical that hearing status is monitored regularly and that hearing intervention goals are revisited as cognitive capacity changes, either with normal ageing or cognitive decline distinct from normal ageing.

Table 2. Selected non-pharmacologic management goals for older adults with hearing loss; adapted from (Jennings et al. Citation2017).

When working with people with any cognitive decline, especially those with dementia, as part of our person-/family-centered approach we must always emphasise the interplay between psychosocial factors, individual factors, the social context, and how we communicate. We must individualise care focusing on the strengths, needs, and lifestyle of our clients from the perspective of the client and their SO/care partner (Dawes et al. Citation2022), taking into account the disability of the latter due to the client’s cognitive impairment (third-party disability; Scarinci, Worrall, and Hickson, Citation2009), building our recommendations into daily routines. Our role as communication specialists is to promote effective and empathetic communication, adapting how we communicate according to our clients’ needs. For example, as cognitive decline progresses, the physical and emotional needs and feelings of our clients remain, but how we communicate with them and how they communicate their needs may change (Kitwood, Citation1991). Verbal modes of communication may give way to more non-verbal modes, though a decrease in verbal communication does not equal a decrease in feeling.

The case study of Mr. Smith highlights how recognising and managing incipient sensory impairment and maximising the client’s ability to function despite a potential neuro-cognitive impairment, is our imperative. It is our responsibility to ensure that each person with whom we work has access to hearing care services regardless of their level of cognitive function.

4. Case study

Mr. Smith was 80 years of age. He arrived 30 minutes late for his appointment at the audiology clinic for an initial hearing test. Dr Jones noted that while she was walking him to her office and talking with him at the same time, he was having difficulty following the conversation. When taking the case history, Dr. Jones noted that Mr. Smith misheard her and was slow in processing what she was saying and to respond. Mr. Smith often asked Dr Jones to repeat her question and appeared distracted by some of the posters hanging on the walls and annoyed by the sound of the air conditioner. Given his apparent difficulty understanding, Dr. Jones asked him if he would like to see a personal amplifier and perhaps even try it out. He was receptive, and after seeing the device, agreed to wear it for the remainder of the session. It was immediately clear that Mr. Smith was benefitting from the improved audibility. He became more focused, his misunderstandings were fewer, and his response time was quicker. He told Dr Jones it was much easier to understand what she was saying. She then knew that Mr. Smith had some level of hearing loss.

When asking questions, Dr. Jones offered Mr. Smith options, as offering choices seemed to facilitate more accurate responses. She found eye contact helpful, as direct gaze helped to capture and focus his attention and to preserve the quality of the social interaction. She also noted that it was important to prompt or cue him when she was speaking, and to validate him, as at times he was frustrated by his occasional confusion.

After 45 minutes Dr. Jones suggested ending the appointment, asking if he would like to continue the session or come back for another appointment with his wife. Dr. Jones asked if Mr. Smith would like to make the appointment or if it was preferable to contact his wife directly. The receptionist then spoke to his wife, who agreed to accompany her husband. Mr. Smith was given an appointment letter to share with his wife regarding the next session (see ).

Table 3. Format of appointment letter (modified from Dawes et al. Citation2022 Jul-Aug 01).

Mr. Smith displayed several behaviours unique to people with either age-related hearing loss and/or cognitive decline. Sensing possible cognitive decline, Dr. Jones adopted communication strategies which facilitated rapport building and trust. In accordance with the Values, Individualised, Perspective and Social (VIPS) framework for individualised and person-centered care, Dr. Jones was person-centered, prioritising respect and personal choice (Clare et al. Citation2019). She also posed simple, answerable questions (e.g. yes/no questions) and asked questions one at a time, giving time for Mr. Smith to process and respond (e.g. would you like to see the amplifier; can I put the amplifier on for you to try it?). She was patient and attentive to his behaviour, allowing adequate time for a response before proceeding to the next question. If Mr. Smith appeared anxious, Dr. Jones was reassuring, praising him before moving on. Dr. Jones included Mr. Smith in decisions, including those regarding treatment and future care. She communicated effectively and empathetically, validating his immediate needs/feelings and connecting with his reality. When she noted that he seemed fatigued and that he might perceive the hearing test as a bit confusing, she asked if he would like to return with his wife for this. It is imperative that family members should work collaboratively with the client and clinician to choose personally relevant and meaningful goals (Clare et al. Citation2019).

5. Case study: next steps

When Mr. Smith returned to the clinic with his wife, he admitted that sometimes he had a hard time understanding his wife and their grandchildren, and that at the end of the day he tuned out, as he was tired from working so hard to listen and communicate. Mrs. Smith indicated that Mr. Smith seemed to be disengaging more over time in large groups because of difficulty following the conversation. Mrs. Smith also reported that Mr. Smith had fallen twice within the past month.

Dr. Jones explained that older adults with hearing loss are often less aware of auditory cues in their environment, may pay less attention to balance maintenance while straining to understand others, and may have difficulty with the increased cognitive demands required when walking and talking at the same time.

Given the potential for fatigue to impact the validity of test results, pure tone and speech testing was abbreviated to obtain the most essential information about Mr. Smith’s hearing status (i.e. his degree of functional hearing disability). While not having a diagnosis of cognitive impairment, adaptations to the testing protocol were necessary. Dr. Jones tailored the testing to Mr. Smith’s individual needs and abbreviated the testing, prioritising gathering the most important results for developing a rehabilitation plan. Pulsed tones, which may be easier to detect, were used. The pacing of tonal presentations was slowed, as reaction time in response to tonal stimuli appeared slow (Bott et al. Citation2019). Sound-field speech understanding in quiet and noise (presented at a conversational level) was conducted by obtaining answers to simple questions/commands (e.g. please point to your nose; what is your favourite colour, etc.). Test results confirmed the presence of some difficulty with speech understanding at a conversational level.

Respecting Mr. Smith’s need for autonomy, Dr. Jones asked if Mrs. Smith could join him when she shared the test results. While active involvement in clinical decisions helps clients retain independence, when memory and judgement seem impaired it is critical that HCPs include a family member when sharing test results and next steps. At any stage of cognitive decline, the capacity to understand information, and to remember it for long enough to evaluate it and to make decisions is often a challenge. Dr. Jones again offered Mr. Smith the personal amplifier used at the initial appointment to optimise audibility and help reduce any cognitively related listening fatigue.

Dr. Jones informed the couple about the nature of the hearing loss Mr. Smith had. She explained that he was having difficulty understanding some sounds which are visible on the lips and underscored the importance of facing Mr. Smith when speaking with him. She confirmed their report of difficulty with understanding in noise, explaining this was typical of most people who develop hearing loss as they get older. She was reassuring, making sure Mr. Smith felt safe and respected while sharing the findings. Mr. Smith asked if he could use something like the personal amplifier, but smaller. Dr. Jones confirmed that there were many options for managing his hearing/processing and communicative challenges.

Dr. Jones emphasised that whatever interventions were chosen, the focus would be on aspects of communication, social relationships, and engagement most relevant to the Smiths’ shared needs and directed at maximising quality of life (Dawes et al. Citation2022). She emphasised that the hearing intervention goal would be to optimise audibility to make communication with others easier and less effortful and to facilitate physician-client communication for effective clinical management. Dr. Jones presented a brief overview of hearing-related intervention options, including hearing aids in combination with communication strategies training and self-management modifications of challenging environments to ensure optimal communication outcomes. She related each option to social engagement, safety in the home, and the importance of reducing stress or challenges when communicating. She encouraged Mr. Smith to return to his primary physician given his falls history and said she would like to send a summary of findings and recommendations to them. The Smiths scheduled a return appointment within two weeks, hopefully after he had seen his personal physician.

6. Optimising the hearing technology use experience

Success with hearing aids and assistive listening devices depends on many factors ranging from the readiness of clients to embrace technology use to the effectiveness of counselling regarding self-management. A systematic review of facilitators and barriers to hearing aid use among people with dementia conducted by Hooper et al. (Citation2022) provides a helpful checklist for audiologists who work with people with any degree of cognitive decline due to normal ageing or neuropathology, suggesting determinants of success with hearing aids are multifaceted and must be individualised, given the variability in behaviours of people with cognitive decline (see ). Age, degree of hearing loss, and cognitive capacity do not seem to influence outcomes with hearing technology. Factors enumerated as integral to hearing aid use/non-use among older community-living adults included handling skills and fit, rehabilitation about how to use hearing aids in real-life situations to improve function in areas meaningful to clients, psychosocial influences such as SO support, experiencing positive consequences from hearing aid use, and having habitual routines around storage and use. Most noteworthy is the importance of participation of family members in each step of the process of obtaining and using hearing technology. HCPs should be able to identify whether clients have the capacity to make unassisted decisions about hearing loss interventions and/or to manage any technology independently. Hooper and colleagues emphasised that social support systems and needs may change over time with changes in cognitive status. It is therefore important for clinicians to closely monitor clients to adapt processes to facilitate the continued use of hearing aids and assistive listening devices. While the Hearing Aid Skills and Knowledge Inventory (HASKI) is lengthy, some items could be helpful to share with care partners to facilitate success with hearing aids (Bennett, Meyer, Eikelboom, & Atlas, Citation2018).

Table 4. Evidence-based suggestions for optimising hearing aid use (adapted from Hooper, et al. Citation2022).

7. Communication strategies and environmental manipulation training

Communication skills training for clients with sensory loss and cognitive challenges and their communication partner can help to optimise outcomes with all forms of hearing assistance technology (e.g. Hickson, Worrall, and Scarinci, Citation2007). Strategies for optimising the physical environment for relationship building, supporting engagement in meaningful activities, and reducing participation and activity limitations are critical, as they can help compensate for peripheral auditory distortions and the cognitive challenges accompanying dementia. It is especially important when working with people with co-morbid sensory loss and cognitive impairment to focus on what people can do rather than what they cannot do, minimise environmental distractions, reduce background noise, maintain eye contact to promote focus of attention, use actions when speaking to illustrate the meaning of spoken information, use short and simple sentences, and to be positive, flexible, and encouraging. See for examples of strategies to reduce communication challenges in appointments for older adults with hearing loss (both with and without cognitive impairment).

Table 5. Strategies which can reduce the communication challenges attending appointments with older adults with hearing loss, with and without/cognitive impairment.

Familial support is vital, and we must ensure that care partners are provided with support to help reduce caregiving burden and stress. Hearing interventions may facilitate improvements in quality of life and in communicative behaviour. We must remember that while available evidence suggests that amplification technologies can support daily function in people with cognitive decline, research is ongoing as to whether management of hearing loss with amplification can affect the course of cognitive decline. There is no definitive evidence for hearing loss as a cause of cognitive decline, and also no high-quality evidence regarding whether hearing interventions could significantly impact cognition in older adults with or without cognitive decline. Setting realistic expectations from auditory interventions and underscoring that they are not curative is crucial.

8. Conclusion

The overall goal of working with older adults should be to assist with maintaining functional ability that enables well-being from mid-life to older age. Educating clients about the potential to reduce their risk of age-related health problems and about how to maintain their function by addressing identified potentially modifiable risk factors early and by remaining socially engaged to optimise cognitive reserve is essential.

An increasing number of clients will have cognitive decline not associated with normal ageing, so HCPs should be knowledgeable partners and effective communicators in raising awareness of the association between hearing loss and cognitive decline, in noticing individual changes and needs, and in providing individualised hearing solutions, auditory rehabilitation and person-centered care. HCPs have an important role to play in supporting clients to live an active and socially engaged life that supports their well-being and quality of life into old age. With the rising prevalence of dementia and other age-related disease, it is increasingly important for HCPs to develop a network of inter-disciplinary professionals to refer to and with whom to collaborate on holistic client rehabilitation management.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).s

References

- Alain, C., Y. Du, L. J. Bernstein, T. Barten, and K. Banai. 2018. “Listening under difficult conditions: An activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis.” Human Brain Mapping 39 (7):2695–2709. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.24031

- Alzheimer’s Association 2021. “2021 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures.”

- Alzheimer’s Association 2021. “Global dementia cases forecasted to triple by 2050.”

- Anderson, L. A., K. L. Day, R. L. Beard, P. S. Reed, and B. Wu. 2009. “The public’s perceptions about cognitive health and Alzheimer’s disease among the US population: a national review.” The Gerontologist 49 Suppl 1 (S1):S3–S11. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnp088

- APA 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, V.A.: American Psychiatric Association.

- Baltes, P. 1987. “Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline.” Developmental Psychology 23 (5):611–626. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0012-1649.23.5.611.

- Baltes, P., and U. Lindenberger. 1997. “Emergence of a powerful connection between sensory and cognitive functions across the adult life span: a new window to the study of cognitive aging?” Psychology and Aging 12 (1):12–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.12.1.12

- Bennett, R. J., C. J. Meyer, R. H. Eikelboom, and M. D. Atlas. 2018. “Evaluating hearing aid management: development of the hearing aid skills and knowledge inventory (HASKI).” American Journal of Audiology 27 (3):333–348. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_AJA-18-0050

- Bott, A., C. Meyer, L. Hickson, and N. A. Pachana. 2019. “Can adults living with dementia complete pure-tone audiometry? A systematic review.” International Journal of Audiology 58 (4):185–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2018.1550687

- Clare, L., A. Kudlicka, J. R. Oyebode, R. W. Jones, A. Bayer, I. Leroi, M. Kopelman, I. A. James, A. Culverwell, J. Pool, et al. 2019. “Goal-oriented cognitive rehabilitation for early-stage Alzheimer’s and related dementias: the GREAT RCT.” Health Technology Assessment 23 (10):1–242. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta23100

- Dawes, P., J. Littlejohn, A. Bott, S. Brennan, S. Burrow, T. Hopper, and E. Scanlan. 2022 Jul-Aug 01. “Hearing assessment and rehabilitation for people living with dementia.” Ear and Hearing 43 (4):1089–1102. https://doi.org/10.1097/aud.0000000000001174

- Diamond, A. 2013. “Executive functions.” Annual Review of Psychology 64 (1):135–168. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750

- Dupuis, K., M. K. Pichora-Fuller, A. L. Chasteen, V. Marchuk, G. Singh, and S. L. Smith. 2015. “Effects of hearing and vision impairments on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment.” Neuropsychology, Development, and Cognition. Section B, Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition 22 (4):413–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825585.2014.968084

- Friederici, A. D. 2012. “The cortical language circuit: from auditory perception to sentence comprehension.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 16 (5):262–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.04.001

- Fulton, S. E., J. J. Lister, A. L. H. Bush, J. D. Edwards, and R. Andel. 2015. “Mechanisms of the hearing–cognition relationship.” Seminars in Hearing 36 (3):140–149. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1555117

- Griffiths, T. D., M. Lad, S. Kumar, E. Holmes, B. McMurray, E. A. Maguire, A. J. Billig, and W. Sedley. 2020. “How can hearing loss cause dementia?” Neuron 108 (3):401–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2020.08.003

- Hickson, L., L. Worrall, and N. Scarinci. 2007. “A randomized controlled trial evaluating the Active Communication Education Program for older people with hearing impairment.” Ear and Hearing 28 (2):212–230. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e31803126c8

- Hooper, E., L. J. Brown, H. Cross, P. Dawes, I. Leroi, and C. J. Armitage. 2022. “Systematic review of factors associated with hearing aid use in people living in the community with dementia and age-related hearing loss.” Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 23 (10):1669–1675.e16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2022.07.011

- Jennings, L. A., A. Palimaru, M. G. Corona, X. E. Cagigas, K. D. Ramirez, T. Zhao, R. D. Hays, N. S. Wenger, and D. B. Reuben. 2017. “Patient and caregiver goals for dementia care.” Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation 26 (3):685–693. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1471-7

- Jessen, F., R. E. Amariglio, R. F. Buckley, W. M. van der Flier, Y. Han, J. L. Molinuevo, L. Rabin, D. M. Rentz, O. Rodriguez-Gomez, A. J. Saykin, et al. 2020. “The characterisation of subjective cognitive decline.” The Lancet. Neurology 19 (3):271–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30368-0

- Kitwood, T.M. 1991. Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first. Open University Press, Buckingham.

- Kricos, P. B. 2009. “Providing hearing rehabilitation to people with dementia presents unique challenges.” The Hearing Journal 62 (11):39–40. 42–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HJ.0000364275.44847.95

- Lin, F., and M. Albert. 2014. “Hearing loss and dementia – who is listening?” Aging & Mental Health 18 (6):671–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.915924

- Lin, F., J. R. Pike, M. S. Albert, M. Arnold, S. Burgard, T. Chisholm, D. Couper, J. A. Deal, A. M. Goman, N. W. Glynn, et al. 2023. “Hearing intervention versus health education control to reduce cognitive decline in older adults with hearing loss in the USA (ACHIEVE): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial.” The Lancet 402 (10404):786–797. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01406-X

- Livingston, G., J. Huntley, A. Sommerlad, D. Ames, C. Ballard, S. Banerjee, C. Brayne, A. Burns, J. Cohen-Mansfield, C. Cooper, et al. 2020. “Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission.” The Lancet 396 (10248):413–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6

- Livingston, G., A. Sommerlad, V. Orgeta, S. G. Costafreda, J. Huntley, D. Ames, C. Ballard, S. Banerjee, A. Burns, J. Cohen-Mansfield, et al. 2017. “Dementia prevention, intervention, and care.” The Lancet 390 (10113):2673–2734. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6

- Maslow, K., and R. Fortinsky. 2018. “Nonphysician care providers can help to increase detection of cognitive impairment and encourage diagnostic evaluation for dementia in community and residential care settings.” The Gerontologist 58 (suppl_1):S20–S31. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx171

- McDaniel, K. D., S. D. Edland, and A. Heyman. 1995. “Relationship between level of insight and severity of dementia in Alzheimer disease. CERAD Clinical Investigators. Consortium to establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease.” Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders 9 (2):101–104. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002093-199509020-00007

- Mosnier, I., A. Vanier, D. Bonnard, G. Lina-Granade, E. Truy, P. Bordure, B. Godey, M. Marx, E. Lescanne, F. Venail, et al. 2018. “Long-term cognitive prognosis of profoundly deaf older adults after hearing rehabilitation using cochlear implants.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 66 (8):1553–1561. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15445

- Mukadam, N., R. Anderson, M. Knapp, R. Wittenberg, M. Karagiannidou, S. G. Costafreda, M. Tutton, C. Alessi, and G. Livingston. 2020. “Effective interventions for potentially modifiable risk factors for late-onset dementia: a costs and cost-effectiveness modelling study.” The Lancet. Healthy Longevity 1 (1):e13–e20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(20)30004-0

- Owens, D., Davidson, K.W., Krist, A.H., Barry, M.J., Cabana, M., Caughey, A.B., Doubeni, C.A., Epling, J.W., Kubik, M., and C.S. Landefeld. 2020. Screening for cognitive impairment in older adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 323 (8): 757–763. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.0435

- Park, D. C., G. Lautenschlager, T. Hedden, N. S. Davidson, A. D. Smith, and P. K. Smith. 2002. “Models of visuospatial and verbal memory across the adult life span.” Psychology and Aging 17 (2):299–320. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.17.2.299

- Patnode, C., L. Perdue, R. Rossom, M. Rushkin, N. Redmond, R. Thomas, and J. Lin. 2020. “Screening for cognitive impairment in older adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services task force.” JAMA 323 (8):764–785. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.22258

- Peelle, J., V. Troiani, M. Grossman, and A. Wingfield. 2011. “Hearing loss in older adults affects neural systems supporting speech comprehension.” The Journal of Neuroscience 31 (35):12638–12643. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2559-11.2011

- Peelle, J. E., and A. Wingfield. 2016. “The neural consequences of age-related hearing loss.” Trends in Neurosciences 39 (7):486–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2016.05.001

- Petersen, R. C., O. Lopez, M. J. Armstrong, T. S. D. Getchius, M. Ganguli, D. Gloss, G. S. Gronseth, D. Marson, T. Pringsheim, G. S. Day, et al. 2018. “Practice guideline update summary: mild cognitive impairment: report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation subcommittee of the american academy of neurology.” Neurology 90 (3):126–135. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000004826

- Pichora-Fuller, M. K., K. Dupuis, M. Reed, and U. Lemke. 2013. “Helping older people with cognitive decline communicate: Hearing aids as part of a broader rehabilitation approach.” Paper presented at the Seminars in Hearing.

- Pichora-Fuller, M. K., S. E. Kramer, M. A. Eckert, B. Edwards, B. W. Y. Hornsby, L. E. Humes, U. Lemke, T. Lunner, M. Matthen, C. L. Mackersie, et al. 2016. “Hearing impairment and cognitive energy: the framework for understanding effortful listening (FUEL).” Ear and Hearing 37 Suppl 1 (1):5S–27S. https://doi.org/10.1097/aud.0000000000000312

- Powell, D.S., Oh, E.S., Lin, F.R., and J.A Deal. 2021. Hearing impairment and cognition in an aging world. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology. 22(4):387–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10162-021-00799-y

- Salthouse, T. 2019. “Trajectories of normal cognitive aging.” Psychology and Aging 34 (1):17–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000288

- Sanders, M. E., E. Kant, A. L. Smit, and I. Stegeman. 2021. “The effect of hearing aids on cognitive function: a systematic review.” PloS One 16 (12):e0261207. https://doi.org/10.4081/audiores.2011.e11

- Scarinci, N., L. Worrall, and L. Hickson. 2009. “The ICF and third-party disability: its application to spouses of older people with hearing impairment.” Disability and Rehabilitation 31 (25):2088–2100. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638280902927028

- Schaie, K. W. 2005. “What can we learn from longitudinal studies of adult development?” Research in Human Development 2 (3):133–158. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427617rhd0203_4

- Smith, J., and P. B. Baltes. 1996. “Altern aus psychologischer Perspektive: Trends und profile im hohen Alter [A psychological perspective on aging: Trends and profiles in very old age].” Die Berliner Altersstudie 221–250. Washington DC: Akademie-Verlag.

- Taljaard, D. S., M. Olaithe, C. G. Brennan‐Jones, R. H. Eikelboom, and R. S. Bucks. 2016. “The relationship between hearing impairment and cognitive function: a meta‐analysis in adults.” Clinical Otolaryngology : 41 (6):718–729. https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.12607

- The Gerontological Society of America 2020. “The GSA KAER toolkit for primary care teams – Supporting conversations about brain health, timely detection of cognitive impairment, and accurate diagnosis of dementia.”

- Tsoi, K., J. Chan, H. Hirai, S. Wong, and T. Kwok. 2015. “Cognitive tests to detect dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” JAMA Internal Medicine 175 (9):1450–1458. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2152

- Tucker-Drob, E. M., and T. A. Salthouse. 2011. In Cognitive Aging. In The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of individual differences, pp 242. Malden, USA: Wiley.

- Tuwaig, M., M. Savard, B. Jutras, J. Poirier, D. L. Collins, P. Rosa-Neto, D. Fontaine, and J. C. S. Breitner 2017. “Deficit in central auditory processing as a biomarker of pre-clinical Alzheimer’s disease.” Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 60 (4):1589–1600. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-170545

- Weinstein, B. E. 1986. “Hearing Loss and Senile Dementia in the Institutionalized Elderly.” Clinical Gerontologist 4 (3):3–15. https://doi.org/10.1300/J018v04n03_02

- WHO 2019a. Integrated care for older people (ICOPE): guidance for person-centred assessment and pathways in primary care Retrieved 11 April 2022, from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-FWC-ALC-19.1

- WHO 2019b. Risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia: WHO guidelines (1–96. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- WHO 2020. “Decade of Healthy Ageing Plan of Action.”

- WHO 2023. Dementia. Key facts. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia#:∼:text=Key%20facts,injuries%20that%20affect%20the%20brain.

- WHO 2021. Hearing screening: considerations for implementation, from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/344797

- Wu, Z., A. Phyo, T. Al-Harbi, R. Woods, and J. Ryan. 2020. “Distinct cognitive trajectories in late life and associated predictors and outcomes: a systematic review.” Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease Reports 4 (1):459–478. https://doi.org/10.3233/ADR-200232