Abstract

Objective

Hearing loss in the older adult population is a significant global health issue. Hearing aids can provide an effective means to address hearing loss and improve quality of life. Despite this, the uptake and continued use of hearing aids is low, with non-use of hearing aids representing a significant problem for effective audiological rehabilitation. The aim of this study was to investigate the reasons for the non-use of hearing aids.

Design and study sample

A cross-sectional survey was used to investigate the reasons given for the non-use of hearing aids by people with hearing loss (n = 332) and family members (n = 313) of people with hearing loss in Australia, the UK, and USA.

Results

Survey results showed that hearing aid non-users generally cited external factors as reasons for non-use, whereas family members reported non-use due to attitudinal barriers. Past users of hearing aids and family members of past users both identified devices factors as barriers to use.

Conclusions

Differences in reasons for non-use may provide further insight for researchers and clinicians and help inform future clinical practice in addressing the low uptake and use of hearing aids by people with hearing loss and the role of family members in audiological rehabilitation.

Introduction

Hearing loss is a significant global health issue that greatly affects older populations. It is estimated that more than 42% of people with a hearing loss are over the age of 60 (WHO Citation2021). The prevalence of a hearing loss of a moderate degree or more increases exponentially with age; ∼15% of people in their 60s have a hearing loss, increasing to 58% for people aged in their 90s (WHO Citation2021). Hearing loss can have a significant impact on quality of life and social-emotional well-being (Timmer et al. Citation2023). The potential effects of unaddressed hearing loss in adults are well-reported in the literature; in older adults it has been associated with depression, social isolation, loneliness, and cognitive decline (Arlinger Citation2003). The use of amplification, such as hearing aids, is an effective form of aural rehabilitation and can improve a person’s health-related quality of life (Ferguson et al. Citation2017). Evidence also suggests that the use of hearing aids may help attenuate cognitive decline (Amieva et al. Citation2015). Despite this, the majority of people with a hearing loss who could benefit from amplification do not use hearing aids (Knudsen et al. Citation2010).

The uptake and use of hearing aids by people with a hearing loss is low. In the USA it is estimated that only 14.2% of adults, aged over 50 with a hearing loss of 25 dB HL or greater, use hearing aids (Chien and Lin Citation2012). In an Australian context, an older study by Chia et al. (Citation2007) found that only 25.5% of people with hearing loss regularly used their hearing aids. A large-scale Welsh study (Dillon et al. Citation2020) showed ∼18% of adult hearing aid owners do not use their devices; a slight decrease from 21% over a 15-year period. Aazh et al. (Citation2015) reported that of people fitted with hearing aids under the UK National Health Service (NHS), 29% used their hearing aids for <4 h per day. New patients were also more likely to be non-regular hearing aid users (40%) compared to existing patients (11%) (Aazh et al. Citation2015). Moreover, for people diagnosed with a hearing loss and deemed to be hearing aid candidates, it takes, on average, a further 8.9 years before they then adopt the use of hearing aids (Simpson et al. Citation2019). These studies highlight the dual problem of both uptake and continued use of hearing aids.

The aforementioned figures are concerning when considering the prevalence of hearing loss in the older adult population and the burden of disease associated with this. The general population worldwide is ageing; and with this comes increased pressure on public health systems (Beard, Officer, and Cassels Citation2016). Given the prevalence of hearing loss in older adults, combined with the numerous social and health issues related to this, it is prudent to investigate the ways in which this impact can be ameliorated. Hearing aids have been identified as an effective way of addressing hearing loss (Ferguson et al. Citation2017), however with the low rates of hearing aid use worldwide, it is important to investigate the reasons for the non-use of hearing aids.

A large body of research has investigated the predictors of help-seeking for hearing loss, hearing aid uptake, and satisfaction; however, the specific reasons why people choose not to use or stop using hearing aids have received less attention. The reasons for non-use are important from a clinical perspective; while predictors may give clinicians an indication of successful hearing aid candidates, factors for non-use may provide opportunities for greater support and counselling to address these issues and increase uptake and use. Current explanations for the non-use of hearing aids are varied, with no single factor identified as the primary underlying cause. Reported reasons for non-use include difficulty in noisy situations, no perceived need or benefit, poor fit and comfort, management difficulties, cosmetic concerns, the influence of others’ experiences with hearing aids, and cost (Aazh et al. Citation2015; Gopinath et al. Citation2011; McCormack and Fortnum Citation2013). Non-regular hearing aid users, as well as those who have discontinued use, gave similar reasons for non-use (Bertoli et al. Citation2009; Gopinath et al. Citation2011).

It is suggested that one reason that people with self-reported hearing loss who do not own hearing aids are the associated cost restrictions (Jorgensen and Novak Citation2020). Conversely, those who report limited hearing difficulties are unlikely to cite cost as the main reason for the non-use of hearing aids (Jorgensen and Novak Citation2020). This is supported by Desjardins and Sotelo (Citation2021) who found that in a Hispanic population of hearing aid non-users, over half of the respondents stated a willingness to use hearing aids to treat their hearing loss, with 75% of this group reporting prohibitive cost as the primary reason for not obtaining hearing aids. For those who were unwilling to use hearing aids, the main reason for non-use was a perceived lack of need (Desjardins and Sotelo Citation2021).

Lockey, Jennings, and Shaw (Citation2010) suggest that successful hearing aid use is not due to device and audiological factors alone, but rather is influenced by an individual’s ability to participate in daily life and how much this participation is affected or limited by hearing loss. Help-seeking behaviour for the treatment of hearing loss is influenced by the severity of the impairment and the presence of social pressure, as well as attitudes towards hearing aids and willingness to use them (Duijvestijn et al. Citation2003). Positive attitudes towards hearing aids appear to have a positive association with use (Hickson et al. Citation2014; Meyer et al. Citation2014). However, the relationship between attitude and the initial uptake of hearing aids is less clear (Knudsen et al. Citation2010). The main conclusion of the Knudsen et al. (Citation2010) study was that self-reported hearing loss is an influencing factor in the success of auditory rehabilitation. More recent research has supported the finding that self-reported hearing loss is a significant predictor of the uptake of hearing aids (Hickson et al. Citation2014; Jorgensen and Novak Citation2020). Hickson et al. (Citation2014) also identified that the perceived benefit of hearing aids and the ability to manage them were both associated with successful hearing aid use.

The attitudes and opinions of family members have a strong influence on people with hearing loss (Meyer et al. Citation2014). A significant finding of the study by Hickson et al. (Citation2014) was the influence of family members and primary communication partners with positive support from family members identified as a key factor in the success of hearing aid use. People with hearing loss are more likely to be successful hearing aid users when their family members have a positive attitude towards hearing aids (Ekberg et al. Citation2023). The reverse is also true: people with hearing loss who perceive family members to have a negative opinion towards aural rehabilitation are unlikely to become long-term hearing aid users (Meyer et al. Citation2014).

Patient-centred care is considered the gold standard of care in the health professions. Davis et al. (Citation2016) report a trend emphasising the psychosocial aspects of audiological rehabilitation, taking into consideration the needs and goals of the client and their family rather than focusing only on audiological aspects of care. A major facet of this is the inclusion of the family as key to decision making and intervention for chronic health conditions. When considering hearing loss, it is often significant others that encourage people to seek help for their hearing loss and thus have an influence on the outcome of these interventions (Ekberg et al. Citation2014; Hickson et al. Citation2014; Meyer et al. Citation2014). Family members, particularly main communication partners, can also suffer third-party disability as the result of a person’s hearing loss (Davis et al. Citation2016). As such, significant insight as to why people with hearing loss do not use hearing aids may be gained by asking those closest to them. The perspective of the family and primary communication partners in the non-use of hearing aids is a topic that has not yet been comprehensively addressed in the literature.

The influence of family members on the uptake and use of hearing aids appears to be limited to the initial stages of the rehabilitation journey (Nixon et al. Citation2021). Family members are known to have a significant role in help-seeking behaviours and initial uptake of hearing aids; however, this influence does not appear to impact the long-term use of hearing aids (Nixon et al. Citation2021). Interestingly, Rolfe and Gardner (Citation2016) reported differing views on the role of family members in the hearing journey. Some people with hearing loss felt that greater family support may have been beneficial, whereas other participants found discussions about their hearing loss with a family member a demotivating factor in help-seeking. In a study by Ekberg et al. (Citation2014), it was found that family members of people with hearing loss typically reported the extent and severity of hearing difficulties being far greater than those reported by the person experiencing them. Furthermore, when amplification options were discussed, family members showed more enthusiasm for the person to obtain hearing aids than the person with the hearing loss. Before aural rehabilitation, family members were almost unanimously in favour of a hearing aid fitting for their family member with hearing loss (Stark and Hickson Citation2004). These findings highlight the effect of hearing loss on family members, but also the influence that they may exert on a person with hearing loss. This presents a potential source of information as to why auditory rehabilitation options, such as hearing aids are so under-utilised.

A considerable volume of research to date has investigated the low uptake of hearing aids, help-seeking behaviours and successful hearing aid use, the influence of family members, and the significance of family and patient-centred care. The interaction, however, between these various elements has not been investigated in great detail. The rationale for the current study is to address the gap in the literature examining why people with hearing loss do not use hearing aids as well as the influence and opinions of family members regarding the issue of non-use of hearing aids. Given the importance of greater uptake and use of aural rehabilitation and also considering the lack of research regarding the views of family members on hearing care, the aim of this study was to investigate the following:

What are the reasons given for the non-use of hearing aids by people with hearing loss? Furthermore, do these reasons differ between hearing aid non-users and past users who have since rejected the use of hearing aids?

What reasons do family members give regarding the non-use of hearing aids by a person with hearing loss in their immediate social circle?

Are there differences in the reasons given for the non-use of hearing aids by these two separate groups (i.e. family members and people with hearing loss)?

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional survey design was used for this study. The data for this study come from the second phase of a research project by Timmer et al. (Citation2022), whereby an online survey was used to investigate several variables, including help-seeking in relation to hearing loss, the use of hearing aids, attitudes to hearing loss and hearing aids, as well as questions relating to the experience of stigma and hearing loss. The research was approved by the University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (n: 2019001869).

Participants

Participants in this study were recruited from three countries, Australia, the UK, and the USA, via the online survey sample platform, Qualtrics (https://www.qualtrics.com). Two separate, unlinked participant groups were recruited from each country: people with hearing loss and family members of people with hearing loss. For the purposes of this study, family members were considered to be anyone with a close relationship to a person with hearing loss (e.g. spouse, family member, close friend, colleague). Across the three countries, a total of 332 people with hearing loss and 313 family members of people with hearing loss were included in the study. This sample size was chosen as regression analysis requires 10 participants per independent variable (Peduzzi et al. Citation1995). Up to 10 potential variables were identified, requiring 100 individuals with hearing loss and 100 family members from each of the three countries (i.e. 600 participants in total for the entire study). Participants were recruited from three different countries to identify if any cultural differences in the experience of hearing aid use were present.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants with hearing loss met the following inclusion criteria:

over 50 years of age

self-reported hearing loss

proficient in reading English

People with cochlear implants were excluded from the study.

For participants in the family member group, inclusion criteria stipulated that they were:

over 18 years of age

had a family member or friend over the age of 50 with a hearing loss

proficient in reading English

Individuals in this group who also had a hearing loss were ineligible to participate. Participants who had a family member with a cochlear implant were also excluded.

Procedures

Participants were recruited using random sampling via Qualtrics Online Sample. Qualtrics provides a sample group of potential participants, representative of a given population, all of whom have expressed interest in participating in online research. Surveys were emailed to potential participants by Qualtrics based on their existing database of users. The survey was conducted online to gain a wide data set and ensure international representation. Survey participants in all three countries accessed the participant information sheet, consent form, and online survey through the Qualtrics online survey platform using their own personal electronic device. Participants were required to first answer screening questions based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine their candidacy for the survey. Access to the survey was only granted after participants selected the “yes” checkbox of the online consent statement, thereby providing informed consent to participate in the study.

The key findings from qualitative interviews in the first phase of the study by Timmer et al. (Citation2022) were used to design the current survey. The survey included single forced choice and multiple choice questions assessing various aspects of hearing, including hearing health, use of hearing aids, and reasons for non-use. The exact wording of questions about the reasons for the non-use of hearing aids are included in Supplementary Appendix A. Attitudes towards hearing aids and hearing loss were measured using a Likert scale with responses from −5 to −1 considered as a negative attitude, 0 a neutral response, and 1–5 signifying a positive attitude. General demographic information, such as age, employment status, cultural background, hearing status, and hearing aid use was also collected.

Analysis

Descriptive data analysis was used to examine responses from participants in both survey groups. Summary statistics, including frequencies, means, and ranges were used to report demographic data. Frequencies and percentages were used to present responses to individual survey questions.

Results

People with hearing loss

The 332 respondents who met the inclusion criteria for people with hearing loss were divided into three groups: hearing aid users, past users of hearing aids, and people who have never used hearing aids, labelled non-users. Past users of hearing aids were defined as those individuals who self-identified as having worn hearing aids in the past but were now not wearing them anymore. The survey did not ask past users to report the length of time they had previously used hearing aids. shows the demographic characteristics of each of the three groups as well as the self-reported hearing status of respondents. The ages of respondents in the three groups ranged from 50 to 85 years, with people in the hearing aid user group being on average 10 years older than the non-user group.

Table 1. Demographic information and hearing status of respondents with hearing loss.

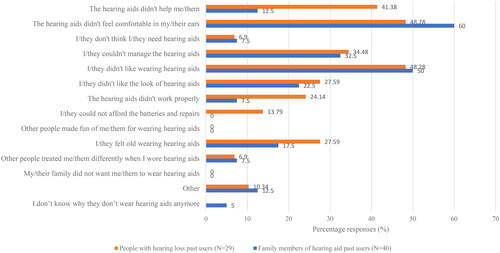

For the past user group (n = 29), device related issues were the largest contributing factor to non-use with 48.28% (n = 14) reporting that “the hearing aids didn’t feel comfortable in my ears” as well as 48.28% (n = 14) stating “I didn’t like wearing hearing aids”. A further 41.38% (n = 12) reported that the hearing aids did not help them.

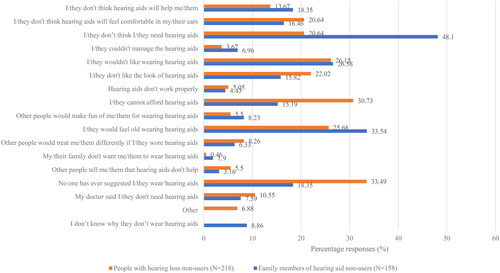

The most common reason for non-use given by the non-user group (n = 218) was that “no one has ever suggested that I wear hearing aids” (33.49%; n = 73). Of the respondents citing this reason, the majority have had their hearing tested (60.27%), most self-reported their hearing level to be “fair” (67.12%), and the length of hearing difficulty was predominantly between 1 and 5 years (56.16%). The general attitude towards hearing aids of this subgroup of non-users was positive (57.53%); this is higher than the positive attitude of all hearing aid non-users (48.62%).

Of the non-user group, 30.73% (n = 67) reported that they were unable to afford hearing aids. Of these respondents, 53.73% (n = 36) were from the USA. Further reasons for non-use given by non-users included “I wouldn’t like wearing hearing aids” (26.15%; n = 57) and “I would feel old wearing hearing aids” (25.68%; n = 56).

Overall, people with hearing loss had a generally positive attitude towards hearing aids; hearing aid users (83.53%), past users (55.17%), and non-users (48.62%). The highest number of negative attitudes were reported by the past user group (34.48%), followed by non-users (23.39%) and hearing aid users (11.76%). Neutral attitudes reported were 4.71% for hearing aid users, 10.34% for past users, and 27.98% for non-users.

Family members of people with hearing loss

The family member group consisted of 313 respondents, the majority of which were female, with ages ranging from 18 to 92 years. shows demographic data for this survey group, as well as their reported ratings of their family member’s hearing status. The majority of respondents rated their family member’s hearing as “fair” or worse and of 1–5 years duration. Just over half (50.48%) of the respondents stated that their family member had never used a hearing aid.

Table 2. Family member group demographic information and their reported hearing rating of their family member.

Of the 40 people who had a family member who is a past hearing aid user, the most common reason given for no longer using hearing aids was that” the hearing aids didn’t feel comfortable in their ears “(60.00%; n = 24), followed by “they didn’t like wearing hearing aids” (50.00%; n = 20), and “they couldn’t manage the hearing aid” (32.50%; n = 13).

For family members of hearing aid non-users (n = 158), the foremost reason for non-use reported was that “they don’t think they need a hearing aid” (48.10%; n = 76). Further reasons were “they would feel old wearing hearing aids” (33.54%; n = 53) and “they wouldn’t like wearing a hearing aid” (26.58%; n = 42).

The attitude of family members to hearing aids was overwhelmingly positive (80.19%). Negative attitudes were low (6.07%), as were neutral attitudes (13.74%).

Comparison between people with hearing loss and family member groups

shows the reasons for the non-use of hearing aids as reported by people with hearing loss who are past hearing aid users and family members of past users. compares the reasons for non-use as given by people with hearing loss who are non-users and family members of non-users. The exact wording and response options for questions relating to the reasons for non-use are given in Supplementary Appendix A.

Discussion

The current study examined the reasons for the non-use of hearing aids as reported by people with hearing loss and family members of people with hearing loss, and compared the reasons given by past users of hearing aids, non-users of hearing aids, and family members. It should be noted that the people with hearing loss group and family member group do not consist of people known to each other, and as such do not form a dyad. People with hearing loss, whether past users or non-users generally cited reasons for the non-use relating to device issues or other external factors that affected the use of hearing aids, such as no recommendation to use hearing aids or cost concerns. Reasons for non-use given by past users and family members of past users also showed agreement; both groups clearly identified lack of comfort and dislike of wearing hearing aids as the two key reasons for non-use. Differences were more apparent in the reasons for non-use as reported by non-users and family members of non-users. Family member perspectives identified attitudinal barriers to non-use. In contrast, people with hearing loss who have never used hearing aids cited reasons for non-use primarily associated with external factors.

That hearing aids had not been suggested was cited as the most common reason for non-use by people with hearing loss. This is an interesting finding and not one that has been examined in depth in the literature to date, with the exception of a small number of studies. Meyer et al. (Citation2014) reported a significant number of non-users who had consulted a health professional regarding their hearing status, were not recommended hearing aids. Data from consumer surveys in the USA, UK, and Australia also align with this finding (Anovum Citation2018, Citation2021; Jorgensen and Novak Citation2020). For US non-users who had consulted a hearing health professional (e.g. an audiologist), only 39% reported being diagnosed with hearing loss, and of these people, only 53% were recommended hearing aids (Jorgensen and Novak Citation2020). Studies from the UK and Australia show similar findings; results consistently reveal that only half of non-users report an audiologist recommending the use of hearing aids (Anovum Citation2018, Citation2021). One interpretation of this finding may be that audiologists are softening their recommendations to pursue amplification to the point that clients chose not to purchase hearing aids, despite having a hearing loss (Jorgensen and Novak Citation2020). This may be tempered by the fact that these same consumer studies also report significant numbers of GPs, and particularly ENTs recommending that no further action be taken regarding a person’s hearing loss (Anovum Citation2018, Citation2021). Many respondents also stated that they were told to wait until their hearing deteriorated further before taking any action (Anovum Citation2018).

It is well-reported in the literature that people who have consulted a health care professional about their hearing loss have likely been experiencing the loss for some time, and by the time of consultation, the hearing loss is likely affecting their quality of life (Knudsen et al. Citation2010; Meyer et al. Citation2014). Respondents in the current study fit this profile, on average describing their hearing as fair and between one to five years in duration. It should be remembered that the results of this study are based on self-report by people with hearing loss, therefore the interactions that have occurred between client and healthcare professional are based on the respondent’s memory, interpretation, and perception of the interaction; this may not be representative of how clinicians perceive the interactions and their recommendations to clients. Barker et al. (Citation2020) report that there may be a disconnect between the perspectives of the patient and clinician experience in the hearing aid journey, particularly in terms of the use, management, and adapting to having hearing aids. The results from the current study could suggest that a disconnect may also exist in earlier stages, that is at the uptake point, of the aural rehabilitation journey. Clinicians may feel they are giving appropriate recommendations for hearing aids to people with hearing loss, but perhaps this advice is not being acknowledged by these clients.

When considering the predominant view of non-users in the current study, that hearing aid use has not been suggested, an alternative explanation may be attributed to the denial of hearing loss. People experiencing denial are unlikely to accept, acknowledge, or admit that they have a hearing loss. Rawool (Citation2018) examined the impact of denial on people with hearing loss and how this can result in the rejection of treatment. Non-users may be experiencing denial regarding their hearing loss and as such, may not acknowledge or may even reject the recommendations of audiologists regarding amplification. This introduces obstacles and barriers to successful aural rehabilitation (Rawool Citation2018). The possible presence of denial may be highlighted by the difference in reasons given by non-users and family members of non-users. In contrast to people with hearing loss, family members described reasons associated with attitudes and beliefs to explain the non-use of hearing aids.

The foremost reason given by family members was that the person with hearing loss does not think they need hearing aids. This can be seen as a form of denial of hearing loss by attempting to minimise the problem (Rawool Citation2018). Family members are often the first people to notice a deterioration in hearing of somebody close to them (Barker, Leighton, and Ferguson Citation2017). This can cause strain on the relationship with the person with hearing loss if that person is not yet aware of their hearing loss or is unwilling to admit to it (Barker, Leighton, and Ferguson Citation2017). Rather than consciously associating the non-use of hearing aids with hearing loss denial, family members may attribute this behaviour to disinterest or selfishness on the part of the person with the hearing loss (Rawool Citation2018). Ekberg et al. (Citation2014) suggest, however, that many family members do explicitly identify these behaviours as denial. It is common for family members to experience frustration with the situation and believe the person with impaired hearing is deliberately using “selective hearing” (Barker, Leighton, and Ferguson Citation2017; Rawool Citation2018). Family members may feel helpless or experience strain within the relationship until the person with the hearing loss is able to accept and address the situation (Barker, Leighton, and Ferguson Citation2017).

The suggestion of a disconnect between patient and provider experience and the possibility of denial of hearing loss perhaps interact when considering the perspectives of family members. This study shows a disparity in reasons for the non-use of hearing aids, with family members rationalising the non-use of hearing aids to beliefs that hearing aids aren’t needed. These reasons are at odds with those given by people with hearing loss, both in terms of how family members view the hearing status of the person with hearing loss and their assessment of how that person is behaving regarding the hearing loss. Ekberg et al. (Citation2014) found that during some audiology appointments, disagreement was displayed between a person with hearing loss and their family member’s account of the hearing difficulties. People with hearing loss had a tendency to minimise the effects and impact of the hearing loss compared to a family member’s account of the situation (Ekberg et al. Citation2014). The authors also found family members were generally in support of hearing aid uptake and were likely to agree with audiologist recommendations for hearing aids. This is a particularly interesting point to note in light of the current study’s finding that people with hearing loss report that hearing aids have never been suggested. The findings of the present study align with those reported by Ekberg et al. (Citation2014) in that the reasons for non-use appear to encompass elements of both disconnect and denial and show inconsistency in the experiences reported by people with hearing loss and family members.

Kelly-Campbell and Plexico (Citation2012) highlight that the experience of hearing loss is perceived very differently by the person with the hearing loss as compared to a primary communication partner, such as a family member. The authors recommend that clinical interventions for aural rehabilitation should consider the perspectives of both the client and their significant other (Kelly-Campbell and Plexico Citation2012). Nixon et al. (Citation2021) also support the notion that increased family support in the initial stages of the hearing aid journey is beneficial.

The results of this study showed that, overall, people with hearing loss indicated a positive attitude towards hearing aids, however, this level was less in the non-user group as compared to the hearing aid user and past user groups. Family members showed a very positive attitude towards hearing aids. A positive attitude towards hearing aids was found to be a significant factor in hearing aid adoption by Meyer et al. (Citation2014). It was also reported that people were also less likely to pursue hearing aids if they perceived family members to have a negative attitude, indicating that social support from family members could have a significant impact on a person’s decision to pursue amplification (Meyer et al. Citation2014). Conversely, a review by Knudsen et al. (Citation2010) did not find conclusive evidence of the effect of attitude towards hearing aids on the uptake of devices. In the current study, despite respondents in both survey groups displaying mostly positive attitudes towards hearing aids, the large number of non-users and past users in this study support the finding of Knudsen et al. (Citation2010) that attitudes about hearing aids are inconclusive when considering initial uptake and use.

Cost has been cited as a barrier to hearing aid ownership (Desjardins and Sotelo Citation2021; McCormack and Fortnum Citation2013) and was found to be the second-most cited reason for non-use of hearing aids by the non-user group in this study. McCormack and Fortnum (Citation2013) reported that financial concerns were cited in half of the studies they reviewed which investigated why people fitted with hearing aids do not wear them. In the current study, those citing cost as a reason for the non-use of hearing aids were predominantly from the USA, where access to subsidised hearing care is limited (Chien and Lin Citation2012). However, access to fully or partially subsidised hearing aids through national health programs or insurance does not appear to significantly increase the uptake of hearing aids. Jorgensen and Novak (Citation2020) compared hearing aid adoption rate data from both MarkeTrak 10 and EuroTrak surveys and found that despite most EuroTrak respondents having access to low or no-cost hearing aids, the uptake rate was only 7% higher than in the USA, where the cost of amplification is not supported by the health system. This suggests that although cost is regularly reported as a barrier to hearing aid use, it is unlikely to be the predominant reason.

It is possible that a lack of awareness and information about funding sources may be a factor. A recent review of the Hearing Services Program in Australia found that more than 60% of people who are eligible for services through the program are not utilising these benefits (Australian Government Department of Health Citation2021). Additionally, in an Australian context, 46% of non-owners did not know if any part of a hearing aid purchase would be funded by either government health services or health insurance (Anovum Citation2021). This is also supported by the most recent EuroTrak UK survey, whereby cost was identified as a top reason for non-ownership of hearing aids (Anovum Citation2018). Less than 30% of non-users believed that a third party (e.g. health insurance or the NHS) would cover any part of the cost associated with obtaining hearing aids (Anovum Citation2018). When considering UK respondents who were hearing aid users, 75% had obtained devices free of charge through the NHS (Anovum Citation2018). This may indicate that prospective hearing aid users are not aware of funding options and therefore believe the cost of hearing aids to be prohibitive. A study by Fuentes-López et al. (Citation2017) found that the use of hearing aids was significantly higher in older adults who were aware of a national health program providing access to hearing aids. The study also found that, for those people who were unaware of the healthcare benefits available, income level was significantly associated with hearing aid use.

The reasons given by people with hearing loss who no longer use hearing aids (i.e. past users), and family members of past users were in agreement and generally align with reasons widely reported in the literature. Both groups clearly identified discomfort with wearing hearing aids as the foremost reason for non-use, followed by a dislike of wearing hearing aids. Past users also did not think hearing aids were of benefit. These results are generally consistent with those in the literature. A review by McCormack and Fortnum (Citation2013) reported similar results, with hearing aid value, comfort, and fit reasons cited as the most important reasons for discontinuing the use of hearing aids. Bertoli et al. (Citation2009) found that dissatisfaction with the device and management difficulties were significant factors in people no longer using hearing aids. In the current study, issues managing the hearing aids were cited as a major reason for non-use by family members.

A strength of this study is the inclusion in the survey design of both people with hearing loss and family members of people with hearing loss. Furthermore, the study had a substantial sample size of hearing aid non-users and family members of non-users from three different countries. In contrast, a limitation of this study is the small sample size of the past user groups as reported by both people with hearing loss and family members. Past users were also not asked to report the length of time they had used hearing aids. It is possible that the level of experience a past user had with hearing aids, for example, a 2-week trial vs. regular use for a year or more, may influence the reasons given for non-use. The use of the self-report survey design also poses some limitations in terms of bias and does not allow for in-depth exploration of the reasons for the non-use of hearing aids that were identified. It should also be considered that the wording of the questions and response options may have restricted family members from selecting certain responses. Although one response option was “I do not know why they don’t wear hearing aids,” family members as a third party may not feel they have enough insight and contact with the person with hearing loss to accurately report as to the reasons for the non-use of hearing aids. A further limitation stems from the fact that the two survey groups, people with hearing loss and family members of people with hearing loss, were not associated. The results comparing the reasons given by people with hearing loss and family members, therefore, should be interpreted with caution as the groups were not related in this survey. Different observations or conclusions may be drawn if the results were taken from a dyad of people with hearing loss and family members of these same people.

Future research should therefore examine the different perceptions of people with hearing loss and family members in relation to the non-use of hearing aids, specifically investigating members from the same family unit, linked as a dyad. How these differing views interact, particularly when perceptions of the same situation are reported, may provide further insight and useful information for clinicians in terms of successful aural rehabilitation strategies for all clients. The specific reasons given by these groups should also be explored in greater depth.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aazh, H., D. Prasher, K. Nanchahal, and B. C. J. Moore. 2015. “Hearing-Aid Use and Its Determinants in the UK National Health Service: A Cross-Sectional Study at the Royal Surrey County Hospital.” International Journal of Audiology 54 (3): 152–161. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2014.967367

- Amieva, H., C. Ouvrard, C. Giulioli, C. Meillon, L. Rullier, and J. Dartigues. 2015. “Self-Reported Hearing Loss, Hearing Aids, and Cognitive Decline in Elderly Adults: A 25-Year Study.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 63 (10): 2099–2104. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13649

- Anovum. 2018. Results: EuroTrak UK 2018. https://www.ehima.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/EuroTrak_2018_UK.pdf

- Anovum. 2021. Results: AustraliaTrak 2021. https://www.ehima.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/AustraliaTrak_2021.pdf

- Arlinger, S. 2003. “Negative Consequences of Uncorrected Hearing Loss – A Review.” International Journal of Audiology 42 (sup2): 17–20. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992020309074639

- Australian Government Department of Health. 2021. Review of the Hearing Services Program: Draft Report. https://consultations.health.gov.au/hearing-and-program-support-division/hsp-review-draft-report/user_uploads/review-of-the-hearing-services-program-draft-report-may-2021.pdf

- Barker, A. B., P. Leighton, and M. A. Ferguson. 2017. “Coping Together with Hearing Loss: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis of the Psychosocial Experiences of People with Hearing Loss and Their Communication Partners.” International Journal of Audiology 56 (5): 297–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2017.1286695

- Barker, B. A., K. M. Scharp, S. A. Long, and C. R. Ritter. 2020. “Narratives of Identity: Understanding the Experiences of Adults with Hearing Loss Who Use Hearing Aids.” International Journal of Audiology 59 (3): 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2019.1683626

- Beard, J. R., A. M. Officer, and A. K. Cassels. 2016. “The World Report on Ageing and Health.” The Gerontologist 56 (Suppl 2): S163–S166. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw037

- Bertoli, S., K. Staehelin, E. Zemp, C. Schindler, C. Bodmer, and R. Probst. 2009. “Survey on Hearing Aid Use and Satisfaction in Switzerland and Their Determinants.” International Journal of Audiology 48 (4): 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992020802572627

- Chia, E., J. J. Wang, E. Rochtchina, R. R. Cumming, P. Newall, and P. Mitchell. 2007. “Hearing Impairment and Health-Related Quality of Life: The Blue Mountains Hearing Study.” Ear and Hearing 28 (2): 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e31803126b6

- Chien, W., and F. R. Lin. 2012. “Prevalence of Hearing Aid Use among Older Adults in the United States.” Archives of Internal Medicine 172 (3): 292–293. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1408

- Davis, A., C. M. McMahon, K. M. Pichora-Fuller, S. Russ, F. Lin, B. O. Olusanya, S. Chadha, and K. L. Tremblay. 2016. “Aging and Hearing Health: The Life-Course Approach.” The Gerontologist 56 (Suppl 2): S256–S267. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw033

- Desjardins, J. L., and L. R. Sotelo. 2021. “Self-Reported Reasons for the Non-use of Hearing Aids among Hispanic Adults with Hearing Loss.” American Journal of Audiology 30 (3): 709–716. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_AJA-21-00043

- Dillon, H., J. Day, S. Bant, and K. J. Munro. 2020. “Adoption, Use and Non-use of Hearing Aids: A Robust Estimate Based on Welsh National Survey Statistics.” International Journal of Audiology 59 (8): 567–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2020.1773550

- Duijvestijn, J. A., L. J. C. Anteunis, C. J. Hoek, R. H. S. Van Den Brink, M. N. Chenault, and J. J. Manni. 2003. “Help-Seeking Behaviour of Hearing-Impaired Persons Aged ≥55 Years; Effect of Complaints, Significant Others and Hearing Aid Image.” Acta Oto-Laryngologica 123 (7): 846–850. https://doi.org/10.1080/0001648031000719

- Ekberg, K., B. H. Timmer, A. Francis, and L. Hickson. 2023. “Improving the Implementation of Family-Centred Care in Adult Audiology Appointments: A Feasibility Intervention Study.” International Journal of Audiology 62 (9): 900–912. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2022.2095536

- Ekberg, K., C. Meyer, N. Scarinci, C. Grenness, and L. Hickson. 2014. “Disagreements between Clients and Family Members Regarding Clients’ Hearing and Rehabilitation within Audiology Appointments for Older Adults.” Journal of Interactional Research in Communication Disorders 5 (2): 217–244. https://doi.org/10.1558/jircd.v5i2.217

- Ferguson, M. A., P. T. Kitterick, L. Y. Chong, M. Edmondson‐Jones, F. Barker, and D. J. Hoare. 2017. “Hearing Aids for Mild to Moderate Hearing Loss in Adults.” The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 9 (9): CD012023. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012023.pub2

- Fuentes-López, E., A. Fuente, F. Cardemil, G. Valdivia, and C. Albala. 2017. “Prevalence and Associated Factors of Hearing Aid Use among Older Adults in Chile.” International Journal of Audiology 56 (11): 810–818. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2017.1337937

- Gopinath, B., J. Schneider, D. Hartley, E. Teber, C. M. McMahon, S. R. Leeder, and P. Mitchell. 2011. “Incidence and Predictors of Hearing Aid Use and Ownership among Older Adults with Hearing Loss.” Annals of Epidemiology 21 (7): 497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.03.005

- Hickson, L., C. Meyer, K. Lovelock, M. Lampert, and A. Khan. 2014. “Factors Associated with Success with Hearing Aids in Older Adults.” International Journal of Audiology 53 Suppl 1 (sup1): S18–S27. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2013.860488

- Jorgensen, L., and M. Novak. 2020. “Factors Influencing Hearing Aid Adoption.” Seminars in Hearing 41 (1): 6–20. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1701242

- Kelly-Campbell, R., and L. Plexico. 2012. “Couples’ Experiences of Living with Hearing Impairment.” Asia Pacific Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing 15 (2): 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1179/jslh.2012.15.2.145

- Knudsen, L. V., M. Oberg, C. Nielsen, G. Naylor, and S. E. Kramer. 2010. “Factors Influencing Help Seeking, Hearing Aid Uptake, Hearing Aid Use and Satisfaction with Hearing Aids: A Review of the Literature.” Trends in Amplification 14 (3): 127–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/1084713810385712

- Lockey, K., M. B. Jennings, and L. Shaw. 2010. “Exploring Hearing Aid Use in Older Women through Narratives.” International Journal of Audiology 49 (8): 542–549. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992021003685817

- McCormack, A., and H. Fortnum. 2013. “Why Do People Fitted with Hearing Aids not Wear Them?” International Journal of Audiology 52 (5): 360–368. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2013.769066

- Meyer, C., L. Hickson, K. Lovelock, M. Lampert, and A. Khan. 2014. “An Investigation of Factors That Influence Help-Seeking for Hearing Impairment in Older Adults.” International Journal of Audiology 53 Suppl 1 (sup1): S3–S17. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2013.839888

- Nixon, G., J. Sarant, D. Tomlin, and R. Dowell. 2021. “Hearing Aid Uptake, Benefit, and Use: The Impact of Hearing, Cognition, and Personal Factors.” Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 64 (2): 651–663. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_JSLHR-20-00014

- Peduzzi, P., J. Concato, A. R. Feinstein, and T. R. Holford. 1995. “Importance of Events per Independent Variable in Proportional Hazards Regression Analysis II. Accuracy and Precision of Regression Estimates.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 48 (12): 1503–1510. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(95)00048-8

- Rawool, V. 2018. “Denial by Patients of Hearing Loss and Their Rejection of Hearing Health Care: A Review.” Journal of Hearing Science 8 (3): 9–23. https://doi.org/10.17430/906204

- Rolfe, C., and B. Gardner. 2016. “Experiences of Hearing Loss and Views towards Interventions to Promote Uptake of Rehabilitation Support among UK Adults.” International Journal of Audiology 55 (11): 666–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2016.1200146

- Simpson, A. N., L. J. Matthews, C. Cassarly, and J. R. Dubno. 2019. “Time from Hearing Aid Candidacy to Hearing Aid Adoption: A Longitudinal Cohort Study.” Ear and Hearing 40 (3): 468–476. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000641

- Stark, P., and L. Hickson. 2004. “Outcomes of Hearing Aid Fitting for Older People with Hearing Impairment and Their Significant Others.” International Journal of Audiology 43 (7): 390–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992020400050050

- Timmer, B. H. B., R. J. Bennett, J. Montano, L. Hickson, B. Weinstein, J. Wild, M. Ferguson, J. A. Holman, V. LeBeau, and L. Dyre. 2023. “Social-Emotional Well-Being and Adult Hearing Loss: Clinical Recommendations.” International Journal of Audiology 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2023.2190864

- Timmer, B., L. Hickson, K. Ekberg, N. Scarinci, C. Meyer, M. Waite, A. Francis, and M. Nickbakht. 2022. “Capturing the Stigma Experiences of Adults with Hearing Impairment, Their Family Members and Hearing Care Professionals [Paper Presentation].” Australian College of Audiology (ACAud) Conference, Melbourne, Australia, May 9–12.

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2021. World Report on Hearing. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/world-report-on-hearing