Abstract

Objectives

To explore when and how stigma-induced identity threat is experienced by adults with hearing loss (HL) and their family members (affiliate stigma) from the perspectives of adults with HL, their family members, and hearing care professionals.

Design

Qualitative descriptive methodology with semi-structured interviews.

Study sample

Adults with acquired HL (n = 20), their nominated family members (n = 20), and hearing care professionals (n = 25).

Results

All groups of participants believed that both HL and hearing aids were associated with stigma for adults with HL. Two themes were identified, specifically: (1) an association between HL and hearing aids and the stereotypes of ageing, disability, and difference; and (2) varied views on the existence and experience of stigma for adults with HL. Hearing care professionals focused on the stigma of hearing aids more than HL, whereas adult participants focused on stigma of HL. Family member data indicated that they experienced little affiliate stigma.

Conclusions

Stigma-induced identity threat related to HL and, to a lesser extent, hearing aids exists for adults with HL. Shared perceptions that associate HL and hearing aids with ageing stereotypes were reported to contribute to the identity threat, as were some situational cues and personal characteristics.

Introduction

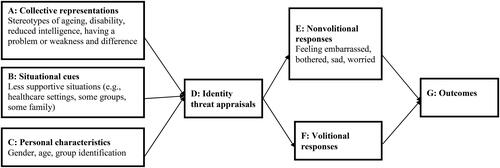

The existing body of research has shown that adults with hearing loss (HL) may experience stigma, which can lead to negative perceptions of hearing loss and hearing aids (HAs) that impacts adherence to treatments and can lead to social segregation (da Silva et al. Citation2023; Wallhagen Citation2010). Goffman (Citation1963) identified two types of stigma: (1) discreditable stigma, in which people whose stigmatised attribute is occasionally apparent (e.g. a person with HL) and (2) discredited stigma, in which people with an obvious stigmatised attribute are readily identifiable (e.g. person wearing visible HAs). Expanding upon Goffman’s model, Major and O'Brien (Citation2005) recognised that stigma is context-specific and resides in the social context of the person. They proposed an identity threat model, illustrating how the presence of a stigmatised attribute (e.g. HL) can potentially threaten a person’s social identity in specific social contexts or situations. The model emphasises how stigma effects are mediated through the person’s perceptions of others (collective representations), understanding of social contexts (situational cues), and their motives (personal characteristics). Stressors from these resources affect whether the individual with stigma (e.g. HL) appraises a situation as a threat to their social identity (identity threat appraisal). Responses can be involuntary, like anxiety (non-volitional responses) or voluntary, like withdrawing from the situation (volitional responses). How this process plays out is associated with outcomes such as changes to self-esteem and health (Outcomes).

There is a small body of previous research that has qualitatively explored both HL and HA stigma experienced by older adults with acquired HL and their families. David and Werner (Citation2016) undertook a scoping review on stigma for HL and HAs from 1982 to 2014 and identified two studies that included qualitative interviews of older adults and their significant others. These two studies both identified stigma related to HL and HAs as being associated with ageing (Kelly-Campbell and Plexico Citation2012; Wallhagen Citation2010). One study also described how the negative reactions of others, including ageism, altered the adults with HL’s perception of themselves (Wallhagen Citation2010). Participants in this study also expressed very negative views about the appearance of HAs.

Barker, Leighton, and Ferguson (Citation2017) reviewed 12 qualitative studies on the psychosocial experiences of adults with HL and their communication partners. “Stigma and identity” was a theme affecting both groups. Although stigma experiences were not explored in detail in many of the studies, adults with HL reported being treated differently because of their HL and/or HAs and communication partners reported feeling the effects of this as well (Barker, Leighton, and Ferguson Citation2017). The impact of stigma on close communication partners is sometimes referred to as affiliate stigma (Mak and Cheung Citation2008). In the review by Barker and colleagues, stigma was largely described as residing in the person with HL, and occasionally also with the communication partner. A criticism of such research is that it lacks consideration of stigma as a social process as per Goffman’s (Citation1963) definition (Ruusuvuori et al. Citation2019).

In contrast, Lash and Helme (Citation2020) examined HL stigma in the context of the social process of communication. Five themes of stigma experiences were identified in their qualitative interviews: feelings of sorry or pity, not being worth others’ time, being labelled as ‘not normal’, having limited capabilities and intelligence, and HL being different from other disabilities. Distinctions were not made between the experiences of those with congenital versus acquired HL so it is difficult to ascertain the relevance of the findings for older adults with acquired HL, who are the focus of the current research study. A recent study by Burnham et al. (Citation2023) explored beliefs, behaviours, and barriers to hearing care among adults with HL in the US who identified as Hispanic or Latino. The majority of their participants associated HL with ageing/genetics and believed in a stigmatised perspective within their community, discouraging any open conversations about HL. Scharp and Barker (Citation2021) also explored the stigma in 30 adults who used HAs and identified two discourses compete to illuminate the meanings of HL, including the Discourse of Hearing Loss as a Relational Reality and the Discourse of Hearing Loss as a Personal Short-coming.

In summary, qualitative research to date has explored the stigma experiences of adults with congenital and acquired HL and, to a lesser extent, the affiliate stigma experienced by their significant others. Evidence of stigma and affiliate stigma related to HL and HAs has been reported, typically with stigma considered as a belief or attitude held by the individual rather than as a social process. Further, previous research has not yet considered the stigma of HL and HAs within a theoretical framework. The aim of the current research was to, for the first time, use a comprehensive framework of the social process of stigma (i.e. the Major and O'Brien (Citation2005) model) to explore HL and HA stigma experienced by older adults (i.e. those with acquired mild to moderate HL) and their families. This study is one part of a larger program of research described in the special issue that aimed to develop a comprehensive understanding of the stigma-induced identity threat model as conceptualised by Major and O'Brien (Citation2005) using a range of methods (qualitative interviews, self-report surveys, Ecological Momentary Assessment and Conversation Analysis) (see details in Ekberg & Hickson, this issue). This paper reports results from qualitative interviews with adults with HL, their family members, and, for the first time, Hearing Care Professionals (HCPs) who regularly work with adults with HL and their families. The research question was: when and how is stigma-induced identity threat experienced by older adults with HL and their families in daily life?

Materials and methods

Participants

Maximum variation sampling was used to recruit three participant groups, including 20 dyads adults with HL and their family members as well as 25 HCPs.

Inclusion criteria for adults were: aged 50 years or older, self-reporting HL, having a family member available for participation, living in the community not in residential care, and proficiency in English. The adult participants with HL were 7 females and 13 males ranging in age from 53 to 88 years who had self-reported hearing difficulties (12 wore hearing aids regularly while eight did not). Their HL ranged from normal hearing in the better ear to moderately-severe, with a mean of 36.4 dB HL (SD = 16) across four frequencies (500, 1000, 2000, 4000 Hz).

Inclusion criteria for family members were: 18+ years old, had a close relationship to the adult with HL, living in the community not in residential care, and proficiency in English. Family members were 16 females and 4 males aged 18–82 years nominated by the adult with HL. Eight family members had HL themselves.

Inclusion criteria for HCPs were: experience working with adults with HL and their families within the last 12 months and proficiency in English. The 25 HCPs were 19 audiologists and 6 audiometrists; 19 females and 6 males with an average of 10.7 years experience working with adults with HL and their families.

Materials

Separate interview topic guides (see Supplementary Materials of Ekberg & Hickson, this issue) were developed for adults with HL, family members, joint interviews, and HCPs to specifically address the aims of this study. Each interview started with a grand tour question (Leech Citation2002), asking the participants to share their experiences of having hearing difficulties, or of having a family member with hearing difficulties, or of working with adult clients with HL and their families. Then the interviewer used appropriate probes to continue the in-depth interview. We did not include direct questions in the interview guides about stigma or affiliate stigma to ensure that we did not influence participants to focus on that topic; instead, questions explored communication and hearing difficulties as well as help-seeking and rehabilitation related to HL and HAs, with participants free to raise issues relating to stigma unprompted. If stigma came up in the interview, the interviewer asked more questions to probe the stigma topic. If the participants did not mention anything related to the stigma towards the end of the interview, the interviewer asked a question directly about it.

Procedure

Participants were recruited throughout Australia through advertising through community organisations and social media platforms (e.g. LinkedIn), word-of-mouth and The University of Queensland Communication Research and Ageing Mind Initiative Registries.

After completing several questionnaires about HL and HA stigma and group identification, adults with HL and family members were interviewed both individually and together in a joint interview. Interviews with adults with HL and family members were conducted face-to-face (at their home or at the university), and HCP interviews were either face-to-face or via Zoom/telephone during a COVID-19 lockdown.

Interviews were conducted by a member of the research team who is a qualified audiologist and trained in qualitative interviews. The duration of interviews for people with HL ranged from 13 to 65 minutes (Mean = 30, SD = 13), for family members from 15 to 50 minutes (Mean = 25, SD = 8.5), for joint interviews from 10 to 39 minutes (Mean = 20, SD = 8), and for HCPs from 20 to 73 minutes (M = 41, SD = 14). Participants received a gift voucher to thank them for their time upon study completion. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim using a professional transcription service. More details are available in the Introduction to the special issue (Ekberg and Hickson Citation2023).

Data analysis

Interviews were analysed using Braun and Clarke (Citation2021) inductive reflexive thematic analysis, following the six steps of thematic analysis:

Data familiarisation. One researcher analysed interview data of HCPs and family members, and another analysed adults’ and joint interview data. Both read the transcripts, made notes of initial insights, and used Microsoft Word and NVivo for the analysis (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 12).

Systematic data coding. Initial codes were generated related to the research question, and these were sorted into categories and subcategories. Analysis trustworthiness was ensured in regular team meetings for peer-checking, addressing coding discrepancies until they reached consensus.

Generating initial themes. Two members of the research team generated the themes and met the team to discuss the categories within each theme.

Developing and reviewing themes. From this step on, the team met several times to discuss and agree on the themes from the data for each participant group.

Refining, defining, and naming themes. Three authors further defined themes and theme names during the drafting of the manuscript. Subsequently, they used deductive analysis (Boyatzis Citation1998) to map the findings in the context of the Major and O’Brien model (2005).

All authors were involved in writing and editing the paper.

Results

Findings from the interviews are presented in terms of the stigma experiences of adults with HL, including those perceived by HCPs and the affiliate stigma experiences of family members of adults with HL. In relation to the stigma experiences of adults with HL, across all interviews with the different participant groups, two themes were identified: (1) an association between HL and HAs and the stereotypes of ageing, disability, and difference; (2) varied views on the existence and experience of stigma for HL and HAs. In relation to affiliate stigma experiences of family members, there was one theme identified: Family members experienced little affiliate stigma. A list of themes, subthemes, and sample quotes from each participant group are presented in a Table in Supplementary Materials. In the example quotations provided in the text and Supplementary Materials, AHL refers to adults with HL, FM to family members, and HCP to hearing care professionals.

Stigma experiences of adults with HL

Theme 1: an association between HL and HAs and the stereotypes of ageing, disability, and difference

All participant groups reported similar stereotypes associated with HL and HAs, including ageing, disability, having a problem, weakness, difference, being less than normal, and reduced intelligence.

Association with ageing/getting old

Ageing was the most prevalent stereotype associated with HL and HAs mentioned by participants. For example, an adult with HL said: “When you get to my age [84], it’s like an old car, isn’t it? Bits keep wearing down and falling off. Hearing’s one of those, and sight” [AHL9]. In regard to HAs, an adult with HL expressed their hesitation about getting HAs as they saw them with a stereotypical connection to old age: “I guess I kind of knew that it [HAs] might help, and same thing also with, ‘Oh, that’s just for old people.’” [AHL17]

One HCP also expressed their belief that adults with HL think: “Well, if I have hearing problem then I'm old” [HCP2]. Another HCP said: A lot of people get, “I’m old now”, that feeling of “it’s finally happened to me. Just put me in the grave because I'm done for”. [HCP7].

However, one adult with HL did not stereotype HAs with ageing, saying: I don’t associate it with age. When I was at school, one of my school mates, he wore hearing aids, the uglier style. And my mum, obviously, she’s worn hearing aids. And so did my brother. So, from an age point-of-view, no. I just see it as doing things that you shouldn’t have done when you were younger has come to bite you on the bum now. Simple as that. [AHL7; joint interview]

Association with having a problem, weakness, and/or disability

The participants expressed their beliefs that HL, and particularly HAs, are associated with having problems, illness, and weakness. An adult with HL, an HCP, and some family members reported HL and HAs were stereotypically linked with being “deaf and dumb.” An adult with HL reported that: “I think, well, if they could see it [HA], then they’d probably think, ‘Oh, well, she’s got a hearing aid.’ … I think some people might think there’s something wrong with you, like you were born that way and you’re not quite right, you’re a little bit disabled a bit.” [AHL11]. A family member also believed that stigma is attached to any disability: “I think absolutely there’s stigma associated with just about any disability of any form; Less than perfect. Society’s pretty cruel with anything that’s less than perfect.” [FM17; joint interview]

Association with being less than normal and/or different from others

Adults with HL and family members reported that HL and HAs are associated with difference and being less than normal. Family members, in particular, expressed their beliefs that adults cover up their HL because they want to look as normal as possible, but using HAs would be a sign of not being normal. A family member said: “I don’t think anybody likes to have anything that stands out, make them look different. So, whether or not it’s hearing aids, or a birthmark, or anything like that, nobody wants to have it standing out” [FM16]. One adult with HL said: “People treat you differently. If you come with a prosthetic limb or something, it’s like that.” [AHL21] Adults with HL reported feeling different when they compared themselves with others “When you get this hearing loss and just put up with it or… But then you’ve got mates who have no hearing problems at all and you’re saying, ‘Oh, what’s wrong with me?’” [AHL8].

Association with reduced intelligence

Some adults with HL associated HL, and to a lesser extent HAs, with lack of intelligence. An adult with HL stated: “they might judge you and think, ‘Oh, well, there’s something wrong with her. She’s probably a little bit lacking in intelligence.’ Not the full quid, as we used to say.” [AHL11]. Similarly, a family member said: “I think I’ve seen examples of where people take a position that assumes that the person with the hearing disability is less intelligent than everyone else” [FM17]. Another family member said people think a person with HL is “stupid” and an “idiot” [FM6]. Another participant mentioned that when people notice HAs they may judge the person and think: “Oh, well, there’s something wrong with her. She’s probably a little bit lacking in intelligence” [AHL11]. However, one HCP believed that in the past adults with HL were judged as not being intelligent, but now people are becoming more and more aware and accepting of HL.

Theme 2: Varied views on the existence and experience of stigma for HL and HAs for adults with HL

Adults with HL focussed on stigma related to HL, and to a lesser extent HAs, whereas HCPs focussed on stigma related to HAs

Most participants in this study reported stigma associated with HL and HAs. Adults with HL often focused on the stigma of HL rather than HAs whereas HCPs mostly focused on the stigma of HAs more so than HL. For example, an adult with HL said: “Once they are aware that you can’t really comprehend or hear what they’re saying, they treat you different. And it’s not always positive, it’s quite often negative…Even people who are familiar with you, my twin brother, he thinks that there’s something wrong with me because I can’t hear him properly. When he can hear perfectly fine. So it’s always there. It’s like you got acne or something.” [AHL21]. In contrast, an HCP said: “There is still that sense of stigma with a hearing aid. Not so much with a hearing loss as much. I don’t think people are so worried about that. They’re more worried about having to have this device that people can see on their ears” [HCP7]. It is important to note that although adults with HL talked broadly about stigma, some reported they did not personally experience stigma linked to HL and HAs.

Some participants also spoke about self-stigma (i.e. the internalising of society’s stigmatising beliefs (Corrigan & Watson, Citation2002)). In a joint interview, a family member reported that stigma is only in “our heads.” [FM10; Joint interview]. Some HCPs also felt there was self-stigma from adults with HL: “I think a lot of the stigma comes from the client themselves. So, they are actually exaggerating the problem or the difficulties. And actually, when they addressed their hearing loss, it’s surprising to see at the follow-up, how they say, ‘Oh I told my colleagues, I told my family about my last visit and they were actually quite supportive.’ So, I think the main barrier, often, is the client themselves and their own stigma towards hearing difficulties” [HCP23].

There were mixed perceptions about whether the stigma for HAs had changed over time. An adult with HL reported that stigma is still being produced by advertisements describing behind-the-ear HAs as “large and ugly” [AHL4] and needing a celebrity to make HAs acceptable. Along similar lines, some family members thought HAs are viewed negatively because of how they looked in the past [big banana HAs] [FM2]. In contrast, several participants reported that stigma has reduced over time, and there is more and more acceptance these days because of other ear-worn devices being used by the general public.

Some adults with HL, family members, and HCPs expressed their opinions about HL and HA stigma for younger people believing that there is more stigma for younger generations. A 73-year-old adult with HL said “Oh, I think that’s just a question of they [younger people with HL] want to appear to be as normal as possible to the opposite sex basically and to their friends. But they don’t want to be considered different.” [AHL12]. In contrast, a few participants believed that young people with HL will experience less discrimination due to their HL. A 62-year-old adult with HL, for example, said “But a younger person with a hearing aid, I’d be surprised if they were discriminated against because they have a hearing aid. They may well be a renowned person in their field, and who’s going to convict them of having a hearing aid in that situation when they’re a leader in their field. So, I don’t assume any discrimination against people with a hearing aid simply because they have one.” [AHL 3]. An 18-year-old child of an adult with HL also said, “I think especially for my generation, it’s not as stigmatised because I grew up with a girl in my class who had hearing aids, and it’s just like, ‘Oh, well something’s happened.’ Obviously, we don’t look at people who have a cast on their hand or a bandage on and go, ‘Oh, they’re a lesser person.’” [FM2].

A HCP also thought young people may think of the more practical side of wearing HAs than its appearance, so they may experience less stigma, saying “And also the fact that younger and younger people are coming in for help shows you that it has changed and that they think about it (hearing aids) in a more practical sense than a cosmetic sense.” [HCP20].

Varying feelings of being embarrassed, bothered, sad, shamed, or worried

Some adults with HL, family members, and HCPs reported feelings of embarrassment, worry, or sadness associated with HL and/or HAs. An adult with HL reported: “I feel embarrassed. And probably, that’s why I don’t ask people all the time for repeats because it’s a constant thing.” [AHL15]. One HCP said: “There are people who consider it’s like a shame to accept that they have a hearing problem.” And: “So, some of them, they are very shy or embarrassed about wearing the hearing device. They think it is too noticeable.” [HCP13]. However, some adults with HL reported not being “embarrassed,” “bothered,” or “worried” by having HL and/or HAs. Similarly, some family members believed that adults with HL generally do not feel shame or embarrassed.

Feeling more comfortable to be with and talk to other adults with HL

Adults with HL in this study explained that they were more “comfortable” with friends and other adults with HL as they understood and were more accepting of HL. An adult with HL also reported that their workplace would not worry them because colleagues were at a similar age and so half of them had HL. Another adult with HL also reported that they had started a support group for adults with HL and how much they enjoyed it, saying: “I think that’s why we all enjoy our hearing impaired groups so much because, we all have difficulties day to day and we all turn them into humour to tell the story to someone else and laugh uproariously” [AHL6].

Varying opinions on family members’ views and actions towards the adult with HL

Adults with HL expressed varied opinions on how their family members view or treat them as a person with HL. Some adults with HL reported their families were “understanding” and helpful in meeting their communication needs. For example, family members may clarify things if the adult with HL does not understand what they are supposed to be doing in group situations; or family members “step in” if the adult does not get what a salesperson is saying when shopping. A family member also reported that she checks if the adult with HL hears the conversation in noisy situations. But some adults with HL reported that their family members did not understand them, had negative views towards HL, were “rude,” or made “snide comments” and fun of HL and/or HAs: “I mean, family drive me crazy sometimes with their expectations and sort of lack of understanding. They’ll walk away from me when they’re talking to me or call out from another room or make snide comments about it, ‘Have you got your hearing aids in?’ That sort of stuff. It’s a bit frustrating as well because often I do, and I just can’t hear” [AHL17]. A couple of adults with HL also talked about families’ frustration and annoyance because of the adults’ HL: “They [family] think it’s a pain in the neck that I can’t hear and it’s frustrating.” [AHL17]

Adults with HL also reported sometimes family members “forget,” “overlook,” or “ignore” their HL and sometimes “patronise” them. One adult believed that her partner had no understanding of HL because “it’s not happening to him”. She also said: “No matter how much you might try and get the message across even to family, there’s resistance. And as far as I’m concerned, that resistance for him and most people is stigma.” [AHL6]

Varying opinions on how the general public views and/or treats adults with HL and/or HAs

Adults with HL had varied opinions on how the public views and treats them. HCPs believe that most adults with HL and/or HAs generally feel the public view them negatively and treat them differently and there can be workplace and job impacts from wearing HAs. Family members typically thought the public was more accepting of people with HL and/or HAs.

Some adults with HL thought HAs are “an accepted fact” and some adults reported the public was understanding and tried to help to meet the communication needs of adults with HL. However, some were unsure about the perceptions of others and thought people may not like to change their communication to help; and others reported a “negative undercurrent” about HL and HAs. Adults with HL in this study also reported that the general public sometimes make rude comments or jokes, excluding adults with HL, and treating/judging them negatively. One adult with HL said “But what I find a lot in meetings and things like that, is that when we were doing engineering, is they just exclude you. They would never direct a question at you, because they figured you didn’t hear what they were saying. You get that a lot.” [AHL21]

In addition, in the joint interviews, some participants reported that healthcare professionals (e.g. nurses, radiologists, and GPs) and healthcare receptionists did not understand and had negative views towards HL. These behaviours of HCPs and receptionists made adults with HL feel they were being treated negatively as different to other people. For example, a family member who had HL shared an experience with a nurse shouting into his ear. He also reported that a doctor refused to talk to him when he asked the doctor to slow down; and the doctor shouted when they repeated their request. His wife believed that stigma was behind the way those doctors acted towards him.

There were both positive and negative attitudes reported about healthcare receptionists. A family member who had HL reported that she felt “so embarrassed” at a hospital reception when she asked for repetition and the receptionist “bellowed it out” so everybody in the waiting room turned around and looked straight at her. However, an adult with HL reported a “great” experience with an X-ray receptionist who was very “positive” and spoke straight to the adult very clearly. Given the different experiences in healthcare services, a family member suggested that “they [people who work in healthcare] should be taught to have a little bit more understanding and empathy before they go into practice” [FM4; joint interview].

On the other hand, some adults with HL reported that the general public was sometimes polite to them and treated them respectfully or with empathy. They also reported that others (outside of the family unit) such as bosses, university colleagues, and friends did not treat them differently.

Most adults with HL and family members are positive about the appearance of modern HAs, but HCPs do not think so

Most adults with HL and family members thought modern HAs were small, discrete, and invisible, and were not concerned with their appearance. In contrast, HCPs spoke more about their views that adults with HL think HAs are big, bulky, and ugly like old HAs were. HCPs thought adults with HL do not want to wear HAs because of the bulky size of HAs, especially, adults who had parents or grandparents who wore big HAs in the past. However, one HCP told clients that HL is more noticeable than HAs. One HCP also reported that HAs are manufactured to be discrete because of stigma, while another HCP was neutral towards HAs appearance.

However, a few adults with HL and family members thought HAs could be smaller still. In the joint interviews, the daughter of an adult with HL expressed her desire for more fashionable HAs. An adult with HL also believed that moving towards smaller HAs would remove the stigma but another adult with HL disagreed: “I don’t think that’s a good move at all … to me that [smaller HAs] feeds stigma” [AHL4].

Participants had different views on how gender might influence reactions to HAs. Some male adults with HL believed that women would be more concerned with the “appearance factor” [AHL10], whereas men would be more concerned with their “macho image” [AHL10]. An adult with HL who said, “I’m not quite what I ought to be as a man because I wear hearing aids” [AHL10] believed that women may feel they would be “out of fashion” with HAs; and HAs may also draw attention. A couple of the male adults with HL also believed that younger people/women with HL are more concerned about appearance than older adults and men.

The perspectives of HCPs regarding the influence of gender on the perception of HAs were diverse. While some HCPs believed that men exhibited higher levels of self-consciousness and were more likely to resist wearing HAs, others held the view that women tended to place greater emphasis on the cosmetics and wanted hair to cover HAs:

I've had a couple of people recently that really think that they stand out and they don’t at all, so they’re refusing to wear them, and this is men, not women. [HCP5]

The women seem to be more hung up about cosmetics, definitely, and about how they look, and, “Can I cover it with my hair?” And ‘I'll just have to let my hair grow. [HCP12]

Acceptability of HAs compared to glasses and other ear-worn devices

Finally, the participants compared HAs with glasses or other ear-worn devices. While some HCPs believed that HAs are not “the same as glasses” [HCP7], other HCPs believed that wearing ear-worn things has become a norm. Some participants thought glasses are more accepted than HAs. In a joint interview, however, one adult with HL said, “If you wear glasses you can wear hearing aids. It’s not more of a problem,” but their family member disagreed and said, “we know it is [a problem].” [AHL10; joint interview]

HCPs believed that HAs could be a fashion item like glasses. While a HCP thought HAs would not have “bling” to match glasses or earrings because of stigma of HAs in Australia, another HCP believed that, in the future, HAs might become like glasses and be made to make a statement, instead of being unobtrusive.

Affiliate stigma experiences of family members of adults with HL

Theme 1: Family members experienced little affiliate stigma

Family members generally did not report affiliate stigma and reported that they did not feel “embarrassed,” “uncomfortable,” or “bothered” because of their family members’ HL and/or HAs: “What their opinions are doesn’t bother me, so as long as [partner with HL] can hear and enjoy what’s going on around him” [FM16]; and “… it doesn’t bother me again, what other people think” [FM12]. While one family member was positive towards HAs and described them as “a good idea”, the other family member described HAs as “necessary evils” that people would wear when hearing is “bad enough.”

A family member also reported that he was aware of the stigma attached to HAs but he did not experience that stigma himself: “You don’t really feel that [wife with HL] feels a great deal of stigma, but I don’t feel any” [FM17]. One family member, however, was neutral about her mother’s HAs: “It wasn’t any of the negative connotations that come with people who have hearing aids. It was just pretty normal for me” and “I have no real difference or feelings towards them [HAs] as I would with someone wearing a tee shirt” [FM1].

One HCP thought affiliate stigma could be a barrier for getting HAs: “Maybe that person [family member] wouldn’t want to be seen with someone [adult] with hearing aids … It probably comes back to stigma as well [HCP12].

Discussion

This qualitative study explored the stigma and affiliate stigma experiences related to HL and HAs from the perspectives of older adults with HL, their family members, and HCPs. Adults with HL described varied experiences. Some reported feelings of embarrassment, bother, sadness or worry associated with having HL and, to a lesser extent wearing HAs; others did not experience these negative feelings. HCPs on the other hand focused on the discredited stigma of HAs (Goffman Citation1963), and felt this was a major concern for adults with HL because other people would react negatively to the visible signs of HL. However, adults with HL and family members were generally positive about the appearance of HAs.

For the family members of the older adults with HL, there was little evidence of affiliate stigma related to HL or HAs. While no hearing-related study has reported affiliate stigma for families of adults with HL to date, it has been reported among families of adults with other health conditions such as intellectual disability (Mitter, Ali, and Scior Citation2019), dementia (Su and Chang Citation2020), and mental health problems (Shi et al. Citation2019; Wang et al. Citation2023). This may be because such conditions have more severe impacts on functioning than mild-to-moderate HL and people with those conditions require greater support from their families. Affiliate stigma is further explored with a more diverse range of participants in phase 2 of this research (see Meyer et al, this issue).

In this section, findings are discussed in relation to the factors that appear to affect the stigma-induced identity threat related to HL and/or HAs for adults with HL (see ) (Major and O'Brien Citation2005). The threat an individual experiences is dynamic and, at any given point in time, is influenced by what they perceive are the collective representations of HL and HAs, the situation they are in, and their personal characteristics.

Figure 1. Finding from this study of the perceptions of adults with HL, family members and HCPs about the stigma experiences of adults with HL mapped on to the Major and O’Brien identity-threat model of stigma.

Collective representations

Based on their experiences, most of the adults with HL, family members and HCPs in the current study perceived that HL and HAs were associated with stereotypes of ageing, disability, reduced intelligence, having a problem or weakness, and difference. The most predominant negative stereotype reported was ageing. This understanding is in accordance with the findings of studies over many years that have reported similar attributions to HL and HAs (David and Werner Citation2016; David, Zoizner, and Werner Citation2018; Gleitman, Goldstein, and Binnie Citation1993; Hindhede Citation2012; Kochkin Citation1993; Scharp and Barker Citation2021). Interesting comparisons can be made with the qualitative findings of Lash and Helme (Citation2020). In their participant group who were, on average, younger than those in the present study and had greater degrees of HL with congenital onset, ageing stereotypes were not described but associations with reduced intelligence, not being normal and differences were reported. Thus, both groups of participants reported negative perceptions linked to HL and HAs, but the association with ageing may be specific to older adults.

The finding that adults with HL and family members held generally positive views about the appearance of modern HAs and believed that the public also held such views, is in stark contrast to previous qualitative studies (Kelly-Campbell and Plexico Citation2012; Wallhagen Citation2010). The change is likely related to the decreased size of hearing aids in the 10+ years since these studies were conducted; certainly, participants in the current study made a clear distinction between the HAs of the past and modern HAs. They reported anger about advertisements describing behind-the-ear HAs as large and ugly, as they believed that this type of advertisement causes HA stigma. Interestingly most HCPs still thought the bulky size of HAs was an issue for adults with HL.

Situational cues

Adults with HL reported several situations in which they were more or less likely to experience stigma-induced identity threat. They reported feeling more comfortable and enjoying situations with others who also had HL and one participant had even started a support group of adults with HL. Humour in the group was considered particularly beneficial and this aspect of coping with stigma is further explored in Ekberg et al. (this issue).

Less supportive situations were identified by participants as occurring in healthcare settings. Some adults with HL and family members reported that health care professionals and healthcare receptionists treated adults with HL negatively by shouting and not slowing down speech. The negative views of receptionists were not a rare experience as one adult with HL described the positive attitude of a healthcare receptionist as “unusual” because he frequently experienced negative attitudes from health receptionists. Given that older adults often access healthcare services, the perceived negative views of receptionists and HCPs about people with HL is concerning.

Adults with HL gave varying reports about the nature of situations that included family. While some adults with HL in the current study reported that their family members displayed understanding towards HL and tried to meet their communication needs, other adults with HL reported having families with negative views who made fun of HL and HAs. Since the family members in this research reported little affiliate stigma it may be that they do not always understand or have empathy for the feelings being experienced by the adult with HL. Varying levels of family support for adults with HL has been reported in many previous studies in which a lack of support has also been identified as a barrier to seeking help for HL and for wearing HAs (Hickson et al. Citation2014; Meyer et al. Citation2014).

Personal characteristics

There were some reports of personal characteristics (gender, age, and group identification) that participants thought could impact the level of experience of stigma. For gender, some men talked about their perspective that women experienced more stigma related to HAs, although they conceded that wearing HAs could negatively affect their “macho image”. Similar views about the stigma of HAs being more relevant to women were expressed by participants in the study by Kelly-Campbell and Plexico (Citation2012).

Age is another personal characteristic that participants in the current study thought influenced the experience of stigma in different ways. Some participants believed there was more stigma for HL and HAs among younger generations whereas others felt it was less. Cienkowski and Pimentel (Citation2001) compared attitudes about HAs in three participant groups: young adults with normal hearing (mean age 20 years), older HAs user adults (mean age 73 years), and older adults with HL who do not use HAs (mean age 69 years). The researchers reported that more than half of the young adults were concerned to be seen wearing HAs, and more than one-third thought they would be embarrassed to wear HAs. Older adult non-users were more likely than the other two groups to associate HAs with being old (Cienkowski and Pimentel Citation2001).

Lastly, group identification may be relevant to stigma-induced identity threat. This relates to the reports of adults with HL of feeling more comfortable when they were in support groups or workplaces with other people with HL. Group identification is a sense of belonging to a social group and a sense of commonality with group members (Cruwys et al. Citation2014). Furthermore, Sani et al. (Citation2015) reported that this sense helps to support healthier behaviours (reduced smoking and drinking, increased exercise and healthy eating). It may be that adults with HL are more likely to seek help for HL and adopt HAs if they identify with others with HL.

Implications of the research

The mismatch between the perspectives of adults with HL and HCPs about HL and HA stigma is a finding with important clinical implications. Adults with HL report the discreditable stigma associated with HL most often, whereas HCPs believe it is the discredited stigma of wearing HAs that is the main issue for adults with HL. This perspective of HCPs may lead them to focus on the appearance of HAs in clinical appointments, whereas time and effort would be better spent on discussing the HL itself and any concerns that a client may have about that. In the present study older adults with HL and their families expressed overall very positive views of modern HAs.

Another implication of this research is that family and those who work in healthcare settings could be more supportive of adults with mild-to-moderate HL. Family members, receptionists, and health care professionals would benefit from education about how best to meet the communication needs of adults with HL without making them feel embarrassed or sad.

Conclusions

Adults with HL reported a range of stigma experiences but family members reported very little affiliate stigma. Negative stereotypes associating HL and HAs with ageing and disability affected the experiences of the adults with HL. HL stigma rather than HA stigma was the major concern for adults with HL and their families, whereas HCPs believed that HA stigma was the more important issue for them. The paper that follows in the special issue by Scarinci et al. (this issue) will examine whether adults with HL and family members exhibit volitional responses associated with the stigma of HL and HAs.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (44.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barker, A. B., P. A. Leighton, and M. A. Ferguson. 2017. “Coping Together with Hearing Loss: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis of the Psychosocial Experiences of People with Hearing Loss and Their Communication Partners.” International Journal of Audiology 56 (5): 297–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2017.1286695.

- Boyatzis, R. E. 1998. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2021. “One Size Fits All? What Counts as Quality Practice in (Reflexive) Thematic Analysis?” Qualitative Research in Psychology 18 (3): 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238.

- Burnham, R., Y. Gamero, S. Misurelli, M. M. Pinzon, and M. Lor. 2023. “Understanding Attitudes, Beliefs, Behaviors, and Barriers to Hearing Loss Care Among Hispanic Adults and Caregivers.” Hispanic Health Care International : The Official Journal of the National Association of Hispanic Nurses 21 (3):150–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/15404153221137671.

- Cienkowski, K., and V. Pimentel. 2001. “The Hearing Aid ‘Effect’ Revisited in Young Adults.” British Journal of Audiology 35 (5): 289–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/00305364.2001.11745247.

- Corrigan, P. W., and A. C. Watson. 2002. “The Paradox of Self-Stigma and Mental Illness.” Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 9 (1):35–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.9.1.35.

- Cruwys, T., S. A. Haslam, G. A. Dingle, C. Haslam, and J. Jetten. 2014. “Depression and Social Identity: An Integrative Review.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 18 (3): 215–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314523839.

- da Silva, J. C., C. M. de Araujo, D. Lüders, R. S. Santos, A. B. M. de Lacerda, M. R. José, and A. C. Guarinello. 2023. “The Self-Stigma of Hearing Loss in Adults and Older Adults: A Systematic Review.” Ear and Hearing 44 (6): 1301–1310. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000001398.

- David, D., and P. Werner. 2016. “Stigma Regarding Hearing Loss and Hearing Aids: A Scoping Review.” Stigma and Health 1 (2): 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000022.

- David, D., G. Zoizner, and P. Werner. 2018. “Self-Stigma and Age-Related Hearing Loss: A Qualitative Study of Stigma Formation and Dimensions.” American Journal of Audiology 27 (1): 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_AJA-17-0050.

- Ekberg, K., and L. Hickson. 2023. “To tell or Not to Tell? Exploring the Social Process of Stigma for Adults with Hearing Loss and Their Families: Introduction to the Special Issue.” International Journal of Audiology: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2023.2293651.

- Gleitman, R., D. Goldstein, and C. Binnie. 1993. “Stigma of Hearing Loss Affects Hearing Aid Purchase Decisions.” Hearing Instruments 44 (6): 16–20.

- Goffman, E. 1963. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Har-mondsworth: Penguin Books Limited.

- Hickson, L., C. Meyer, K. Lovelock, M. Lampert, and A. Khan. 2014. “Factors Associated with Success with Hearing Aids in Older Adults.” International Journal of Audiology 53 (suppl 1): S18–S27. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2013.860488.

- Hindhede, A. L. 2012. “Negotiating Hearing Disability and Hearing Disabled Identities.” Health 16 (2): 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459311403946.

- Kelly-Campbell, R., and L. Plexico. 2012. “Couples’ Experiences of Living with Hearing Impairment.” Asia Pacific Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing 15 (2): 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1179/jslh.2012.15.2.145.

- Kochkin, S. 1993. “MarkeTrak III: Why 20 Million in US Don’t Use Hearing Aids for Their Hearing Loss-Part 1.” Hearing Journal 46: 20–20.

- Lash, B. N., and D. W. Helme. 2020. “Managing Hearing Loss Stigma: Experiences of and Responses to Stigmatizing Attitudes & Behaviors.” Southern Communication Journal 85 (5): 302–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/1041794X.2020.1820562.

- Leech, B. L. 2002. “Asking Questions: Techniques for Semistructured Interviews.” Political Science & Politics 35 (04): 665–668. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096502001129.

- Major, B., and L. T. O'Brien. 2005. “The Social Psychology of Stigma.” Annual Review of Psychology 56 (1): 393–421. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137.

- Mak, W. W., and R. Y. Cheung. 2008. “Affiliate Stigma Among Caregivers of People with Intellectual Disability or Mental Illness.” Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 21 (6): 532–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2008.00426.x.

- Meyer, C., L. Hickson, K. Lovelock, M. Lampert, and A. Khan. 2014. “An Investigation of Factors that Influence Help-Seeking for Hearing Impairment in Older Adults.” International Journal of Audiology 53 (Suppl 1): S3–S17. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2013.839888.

- Mitter, N., A. Ali, and K. Scior. 2019. “Stigma Experienced by Families of Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities and Autism: A Systematic Review.” Research in Developmental Disabilities 89: 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2019.03.001.

- Ruusuvuori, J., T. Aaltonen, I. Koskela, J. Ranta, E. Lonka, I. Salmenlinna, and M. Laakso. 2019. “Studies on Stigma Regarding Hearing Impairment and Hearing Aid Use Among Adults of Working Age: A Scoping Review.” Disability and Rehabilitation 43 (3): 436–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1622798.

- Sani, F., V. Madhok, M. Norbury, P. Dugard, and J. R. Wakefield. 2015. “Greater Number of Group Identifications is Associated with Healthier Behaviour: Evidence from a Scottish Community Sample.” British Journal of Health Psychology 20 (3): 466–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12119.

- Scharp, K. M., and B. A. Barker. 2021. “I Have to Social Norm This”: Making Meaning of Hearing Loss from the Perspective of Adults Who Use Hearing Aids.” Health Communication 36 (6): 774–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1712523.

- Shi, Y., Y. Shao, H. Li, S. Wang, J. Ying, M. Zhang, Y. Li, Z. Xing, and J. Sun. 2019. “Correlates of Affiliate Stigma Among Family Caregivers of People with Mental Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis.” Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 26 (1-2): 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12505.

- Su, J.-A., and C.-C. Chang. 2020. “Association between Family Caregiver Burden and Affiliate Stigma in the Families of People with Dementia.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (8): 2772. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082772.

- Wallhagen, M. I. 2010. “The Stigma of Hearing Loss.” The Gerontologist 50 (1): 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnp107.

- Wang, Y.-Z., X.-D. Meng, T.-M. Zhang, X. Weng, M. Li, W. Luo, Y. Huang, G. Thornicroft, and M.-S. Ran. 2023. “Affiliate Stigma and Caregiving Burden Among Family Caregivers of Persons with Schizophrenia in Rural China.” The International Journal of Social Psychiatry 69 (4): 1024–1032. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640231152206.