Abstract

Objective

Hearing aid use is lowest in 0–3-year-olds with hearing loss, placing spoken language development at risk. Existing interventions lack effectiveness and are typically not based on a theoretically driven, comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing infant hearing aid use. The present study is the first to address this gap in understanding.

Design and Study Sample

A 55-item online survey based on the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) was completed by 56 parents of 0–3-year-old hearing aid users.

Results

Participants reported a wide range of barriers across TDF domains, which were associated with parent-reported hearing aid use and more pronounced in parents of lower hearing aid users. The most strongly reported domains across participants were “emotion” (e.g. feelings of worry when using hearing aids), “beliefs about capabilities” (e.g. belief in ability to use hearing aids consistently), and “environmental context and resources” (e.g. child removing hearing aids).

Conclusions

Parents report a wider range of barriers to infant hearing aid use than existing investigations suggest and current interventions address. Interventions would benefit from: (i) targeting a wider range of TDF domains in their design; and (ii) implementing the present TDF survey to identify and target family-specific barriers to infant hearing aid use.

Introduction

Permanent hearing loss is present from birth in around 1 to 2 per 1000 children and poses significant risk to spoken language development. Early amplification with hearing aids alongside high-quality linguistic input, mitigates against this risk by increasing access to speech sounds, audiologic cues, and caregiver interaction, crucial for spoken language development during the first years of life (Kuhl Citation2004; Sininger, Doyle, and Moore Citation1999). Although the implementation of newborn hearing screening programmes – an initiative to enable early diagnosis and amplification – has made the early provision of hearing aids a possibility across several countries (Bussé et al. Citation2021), hearing aids need to be worn consistently for the full benefits of early audiologic intervention to be maximised (McCreery, Walker, Spratford, Bentler et al. Citation2015). Yet, hearing aid use is at its lowest and most variable in children under 3 years of age (Visram et al. Citation2021; Walker et al. Citation2015). Inconsistent hearing aid use during this critical period for language development (Dupoux et al. Citation2001) has significant implications for later spoken language outcomes (Tomblin et al. Citation2015). As a result, there have been increasing calls from researchers and practitioners for interventions to support parents to increase their child’s hearing aid use during infancy and toddlerhood (McCreery, Walker, and Spratford Citation2015; Visram et al. Citation2021). However, few interventions currently exist and the empirical evidence to support their effectiveness is limited (Ambrose et al. Citation2020; Muñoz et al. Citation2021).

To develop effective interventions, a theoretically informed understanding of the potential drivers of consistent infant hearing aid use is needed to ensure that future intervention efforts address the full range of factors that might influence parents consistently implementing their child’s hearing aid use during infancy and toddlerhood (Michie, Atkins, and West Citation2014). The use of theory to inform behaviour change interventions strengthens their uptake and effectiveness (Michie, Atkins, and West Citation2014), and is recommended by the UK Medical Research Council (Skivington et al. Citation2021) and the UK’s Department of Health and Social Care (GOV.UK. Citation2023). Broadly speaking, behaviour change theories provide explicit statements of the structural and psychological processes that determine behaviour (in the present study, implementing infant hearing aid use consistently or not). Adopting a theory-driven approach provides a means to systematically and comprehensively identify specific determinants that are hypothesised to regulate behaviour and behaviour change (Atkins, Francis, Islam, O’Connor, et al. Citation2017). There are several models of behaviour change; however, the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) is one of the most widely used as it synthesises 128 theoretical constructs from 33 behaviour change models, clustered into 14 domains that explain the potential determinants of behaviour (Atkins, Francis, Islam, O’Connor, et al. 2017; Cane, O'Connor, and Michie Citation2012; Cowdell and Dyson Citation2019). In short, the TDF provides an integrative framework to systematically and comprehensively explore factors underlying infant hearing aid use that limits the risk of omitting important behavioural determinants.

Although research into potential factors influencing the implementation of infant hearing aid use exists (e.g. Muñoz et al. Citation2015; Muñoz et al. Citation2016), investigations have yet to take a theory-driven approach. Current knowledge may therefore only tap into a limited range of the barriers to, and facilitators of, infant hearing aid use. Indeed, findings from a recent systematic review utilising the TDF suggest existing research – particularly quantitative studies – tended to measure the same or similar constructs (e.g. skills in practical hearing aid management; Kelly et al. under review). Specifically, the majority of quantitative studies used the same or similar measurement tools (e.g. Muñoz et al. Citation2015; Muñoz et al. Citation2016), which largely focus on a subset of determinants of infant hearing aid use. Indeed, qualitative studies (i.e. studies that are more participant led as opposed to constrained by specific measurement tools) tend to identify a different range of factors, suggesting that how barriers to infant hearing aid use are studied (i.e. methodological approach to data collection) is associated with the type of factors reported (Kelly et al. under review). Developing behaviour change interventions without a systematic and comprehensive account of the full range of potential behavioural determinants may not only limit their effectiveness, but also inhibit engagement and uptake with the intervention itself (Michie, Atkins, and West Citation2014). Therefore, the aim of the present study was to: (i) use the TDF to explore factors that might prevent consistent infant hearing aid use; and (ii) explore whether specific TDF domains might be associated with infant hearing aid use. This study forms part of a wider project (Consistent Hearing aid Use in Babies [CHerUB]; Kelly Citation2023) that (i) aims to triangulate findings from 3 methodologically different studies that utilise the TDF to investigate drivers of consistent hearing aid use in 0–3-year-olds (including the present study), to then (ii) develop a tailorable intervention to support parents to increase their child’s hearing aid use during infancy and toddlerhood. We hope that this programme of research will facilitate the development of behaviour change interventions that can be tailored to the specific barriers families face when it comes to consistently implementing their child’s hearing aid use during these early years. Indeed, the present research speaks directly to several key principles outlined in the international consensus statement on best practices in family-centred early intervention for children who are deaf or hard of hearing (recently updated; Moeller et al. Citation2024). Particularly in relation to: (i) the early, timely, and equitable provision of supports; (ii) individualised family support that considers the wider family unit, their cultures and communities, and barriers beyond the individual, recognising that hearing aid use is a dynamic and changing process that requires intervention approaches tailored to family needs; and (iii) early and consistent access to language and communication.

Materials and methods

To ensure complete and detailed reporting, the present research is reported in line with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines (Von Elm et al. Citation2007) and specifically follows the checklist for observational cross-sectional studies.

Study design and setting

The present research is an exploratory, cross-sectional, survey of parents of children under 36 months of age who use hearing aids. The study was conducted online using the survey hosting platform Qualtrics, and recruitment and data collection took place between May 2022 and January 2023. Ethical approval to conduct the study was granted by the Proportionate University Research Ethics Committee (UREC), University of Manchester (reference 2022-14201-23294).

Participants

To be eligible to take part in the present research, participants needed to be a parent or legal guardian of a child: (i) aged between 0 and 36 months (inclusive); (ii) with permanent hearing loss (of any type, laterality, and severity); and (iii) fitted with at least one hearing aid (non-surgical e.g. behind the ear [BTE] hearing aid, bone conduction hearing device on a soft band). Participants were recruited across the United Kingdom (UK) using opportunity sampling, predominantly via professionals and organisations who disseminated a web link to potential participants via text, email, post, or relevant social media platforms. Professionals and organisations who facilitated recruitment included the authors’ professional networks (namely Teachers of the Deaf), a large national charity for childhood deafness in the UK (The National Deaf Children’s Society, NDCS), professional bodies and associations (e.g. The British Association of Teachers of the Deaf, BATOD), and relevant forums (e.g. the UK Heads of Sensory Services forum). Additionally, the web link was disseminated via a research project-specific website and related social media channels. Participants who were interested in taking part followed the web link, which took them to an online participant information sheet and electronic consent form. After providing consent, participants completed the anonymous sociodemographic survey and the barriers to infant hearing aid use TDF survey (detailed below) before receiving a debrief about the study. Participants were given the option to provide their email address to receive a £10 retail voucher as compensation for their time.

Data measurement

Sociodemographic and clinical measurements

Participants reported a range of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics using a self-report survey. Questions generally pertained to information about the parent (e.g. socioeconomic measures, age, experience of hearing loss/deafness) and their child who uses hearing aids (e.g. degree of hearing loss, hearing device(s) used, parent-reported daily hours of hearing aid use). Open-ended data were also collected to ascertain advice or instructions received about how often the participant’s child should be wearing their hearing aid(s) each day (i.e. a measure of what consistent hearing aid use meant per family) and by whom, as well as an open-ended question for additional comments to explore potential barriers not identified by the TDF survey.

Development of the Theoretical Domains Framework survey

We developed a survey to measure parent-reported barriers to infant hearing aid use based on the TDF in two steps. Step one involved using established guidelines and extant literature to develop an initial draft of the survey. In step two, parents of infant hearing aid users and professionals who support families to implement their child’s hearing aid use provided feedback on the survey, which was incorporated into the final version.

Step one: initial development using extant literature

The generic TDF survey template reported by Huijg and colleagues (Huijg, Gebhardt, Dusseldorp, et al. Citation2014; Huijg, Gebhardt, Crone, et al. Citation2014) formed the basis of the present survey, which is worded in such a way to allow tailoring to different actions, targets, contexts, and times of interest (i.e. parents consistently implementing their child’s hearing aid use). To adapt the generic TDF survey for use in the present research, we altered the phrasing of the generic template survey items, so they were more appropriate to the present research. For example, the generic item, “I know how to [action] in [context, time] with [target],” became, “I know how to use hearing aids with my child” in the present survey. However, we did not include items for the TDF domain “reinforcement” from the generic TDF survey for two reasons. First, Huijg et al. (Citation2014) reported problems with the psychometric properties of the "reinforcement" domain in that the specific items tended to overlap too heavily with the “beliefs about consequences” domain. For example, the original reinforcement item, “I feel like I am making a difference” was judged as actually measuring the “beliefs about consequences” TDF domain. Consequently, a later iteration of the TDF survey by the authors collapsed items purportedly measuring reinforcement into the “beliefs about consequences” domain (Huijg, Gebhardt, Dusseldorp, et al. Citation2014). Second, the reinforcement items in the TDF template were deemed inappropriate for the present behaviour and context (e.g. “I get financial reimbursement for [action], [context, time] with [target],” given that payment for hearing aid use is not currently on the agenda. Further, acceptability of financial incentives for health-related behaviour change is polarised, and may be particularly complex when comes to particular incentive targets, such as medication adherence (Hoskins et al. Citation2019). Low acceptability of incentivisation would likely place intervention uptake at risk (Giles et al. Citation2016). Consequently, given that reinforcement items tended to measure “beliefs about consequences” that were already explicitly represented in the present survey and that items were also inappropriate for the present study, the "reinforcement" domain was omitted from this iteration of the TDF survey.

Step two: parent and professional involvement

We involved both parents and professionals in the development of the survey through consultation by asking four parents of infant hearing aid users and four professionals who work with families to support infant hearing aid use (two Qualified Teachers of the Deaf and two paediatric Audiologists) to review and feedback on the initial survey. These stakeholders provided feedback around the general acceptability and comprehension of the survey, the appropriateness and completeness of the survey items and domains, and whether there were any additions they would like to see in the final version. Feedback from stakeholders was incorporated into the final iteration of the TDF survey. For example, the survey developed in step one asked, “Other parents who have a child using hearing aids are a source of help and support for me around using hearing aids with my child” under the “social influences” domain. Parent and professional feedback suggested that we extend this idea further by also asking, “Meeting a deaf adult(s) using hearing aids has helped me when it comes to using hearing aids with my child.” The TDF survey used in the present study is therefore evidence driven and refined to the present context and target behaviour (i.e. implementing consistent infant hearing aid use) based on stakeholder input.

The final TDF survey

The final TDF survey can be seen in Supplementary Materials A and comprises 55 items measuring 13 TDF domains: “knowledge,” “skills", “social/professional role and identity,” “beliefs about capabilities,” “optimism,” “beliefs about consequences,” “intentions,” “goals,” “memory, attention and decision processes,” “environmental context and resources,” “social influences,” “emotion,” and “behavioural regulation”. For a brief overview of definitions for each TDF domain measured, see . For a more detailed account, see Atkins et al. (2017). Participants were asked to respond to each item using a 5-point Likert scale to indicate the extent to which they agreed with each statement ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Not all TDF domains had an equal number of items; therefore, we used the mean domain score to aid comparison between domains. Lower mean domain scores indicated that the domain was more of a barrier to infant hearing aid use.

Table 1. Definitions of the domains of the TDF.

Internal reliability of the TDF survey

shows the internal reliability of items for each TDF domain (i.e. Cronbach’s alpha) alongside 95% confidence intervals. Overall, internal reliability was high and in the acceptable range or above for 10 of the 13 TDF domains (77%). However, the “emotion” and “social influences” domains of the TDF survey were in the poor acceptability range, and “optimism” had unacceptable reliability. For the “emotion” domain, item 3 (“getting my child to use hearing aids as often as advised makes me feel positive/good”) appeared to be the main cause of reliability issues, as it did not correlate with other items in the domain (r = −0.09, −0.02, −0.10 for items 1, 2, and 4 respectively), nor with the total domain score (r = −0.02), and removing the item increased reliability closer to the acceptable range (a = 0.60; Kline Citation1999). Regarding the “optimism” domain, item 1 (“when I feel unsure that I can get my child to use hearing aids as often as I’ve been advised to, I usually feel like things will work out okay in the end”) and item 2 (“making sure my child uses hearing aids as often as advised makes me feel optimistic/hopeful about my child’s future”) were not correlated (r = −0.08) and seemingly did not tap into a similar construct. Similarly, items from the “social influences” domain tended to correlate with one another in the weak range (average r = 0.15), with no single item being particularly responsible for the low Cronbach’s alpha. Consequently, the “optimism” and “social influences” domains should be interpreted with caution in the present research and will need to be revised in future iterations of the barriers to infant hearing aid use TDF survey.

Table 2. Reliabilities.

Quantitative variables

Calculating TDF domain scores

Each domain score was calculated by first reverse coding any negatively worded items so that lower scores indicated more of a barrier to infant hearing aid use, before calculating the mean participant score for items in each domain.

Adjusted parent-reported hearing aid use

To maximise the benefits of hearing aids, they are ideally worn as often as possible during infant waking hours. However, given that there are differences in infant waking hours (depending on several factors including age, developmental stage, individual variation) it is important that reports of hearing aid use are adjusted for waking hours. Therefore, parent-reported hearing aid use (i.e. the number of hours participants reported their child wore their hearing aids on a day-to-day basis) was adjusted by the number of hours that the parent reported that their child was typically awake (i.e. total hearing aid use divided by total waking hours multiplied by 100).

Statistical methods

All analyses were conducted in JASP (v0.16.1.0; JASP Team Citation2022). Given the preliminary and exploratory nature of the present research, we prioritised measures of the magnitude of effect and associated 95% confidence intervals (Scheel et al. Citation2021; Szucs and Ioannidis Citation2017). We report the mean score for each TDF domain (analysis 1) and the Pearson’s r correlations between each domain of the TDF and adjusted parent-reported hearing aid use (analysis 2). Mean scores for each individual item of the TDF survey can be found in Supplementary Materials B. Although testing for statistical significance was not the aim of the present study, we considered any confidence interval that did not overlap the null to be statistically significant (Payton, Greenstone, and Schenker Citation2003).

Subgroup analysis

To investigate whether parent reported barriers differ between those reporting higher vs. lower hearing aid use, we conducted a subgroup analysis. Subgroups were determined by computing a median split based on adjusted hearing aid use, where participants reporting use below the median of 87% (of waking hours) were classified as “lower” hearing aid users and those reporting above or equal to the median were classified as “higher” users. Mean adjusted hearing aid use was 54% and 96% in the “lower” and “higher” groups, respectively. We then conducted multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with higher vs. lower adjusted hearing aid use as the independent variable, and the 13 TDF domains as the dependent variables, before examining pairwise comparisons of each TDF domain (adjusted for multiple comparisons).

Results

Participants

Full details of participant characteristics and demographic information are shown in . A total of 56 questionnaires were completed. All participants met the inclusion criteria and were retained for analysis. Participants were predominantly mothers (95%; n = 53) of infants aged 4 to 36 months (M = 18 months). As reported by parents, most infants had moderate hearing loss (i.e. 41 – 70 dB HL) in the better ear (43%; n = 24) and were using bilateral behind-the-ear hearing aids (79%; n = 44). According to parent report, infants were using their hearing aids on average 75% of their waking hours. In relation to what consistent hearing aid use meant per family, 94% of participants (n = 53) reported that they were advised or instructed by their Audiologist or Teacher of the Deaf (i.e. provider of early support) that their child should be wearing their hearing aid(s) all waking hours or as much as possible each day (n = 41 and 12 respectively). Two of the remaining participants were given the target of achieving 10 hours and 8 hours per day respectively (reported awake hours were 12 and 10 respectively). The final participant responded stating “As my baby does not like using her hearing aid, we try to wear it little and often” (reported awake hours was 10).

Table 3. Participant characteristics and demographic information.

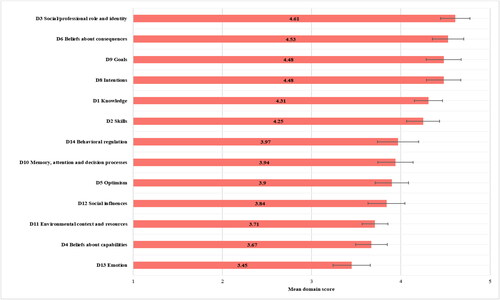

Analysis 1: Which domains of the TDF represent parent reported barriers to infant hearing aid use?

displays the mean reported score for each domain of the TDF measured alongside 95% confidence intervals. Scores for each domain can range from 0 to 5, with lower scores indicating more of a barrier to hearing aid use. Parents endorsed “emotion” related factors (e.g. feeling negative emotions when using hearing aids, such as stress, M = 3.45, SD = 0.80, 95% CI = 3.24 to 3.66), as the TDF domain that most impacted hearing aid use. The next most strongly reported TDF domain was “beliefs about capabilities” (e.g. perceived ability to use hearing aids consistently, such as confidence and control, M = 3.67, SD = 0.68, 95% CI = 3.49 to 3.85), followed by “environmental context and resources” (e.g. environmental circumstances impacting consistent hearing aid use, such as time and support, M = 3.71, SD = 0.55, 95% CI = 3.57 to 3.85), “social influences” (e.g. interpersonal processes, such as the attitudes and influence of others, M = 3.84, SD = 0.79, 95% CI = 3.63 to 4.05), “optimism” (e.g. the confidence that things will work out for the best, M = 3.90, SD = 0.74, 95% CI = 3.71 to 4.09), “memory, attention and decision processes” (e.g. remembering to put their child's hearing aids on, M = 3.94, SD = 0.75, 95% CI = 3.74 to 4.14), and “behavioural regulation” (e.g. having a plan for when to put their child's hearing aids on, M = 3.97, SD = 0.88, 95% CI = 3.74 to 4.20). Finally, the domains of the TDF that were reported as less of a barrier included “social/professional role and identity” (e.g. belief it is part of their parental role to use hearing aids consistently, M = 4.61, SD = 0.63, 95% CI = 4.44 to 4.78), “beliefs about consequences” (e.g. belief that consistent hearing aid use will benefit their child, M = 4.53, SD = 0.67, 95% CI = 4.35 to 4.71), “intentions” (e.g. consciously deciding to use hearing aids consistently, M = 4.48, SD = 0.74, 95% CI = 4.29 to 4.67), “knowledge” (e.g. why and how to use hearing aids, M = 4.48, SD = 0.75, 95% CI = 4.28 to 4.68), and “skills” (e.g. having the ability to use hearing aids, M = 4.25, SD = 0.71, 95% CI = 4.06 to 4.44).

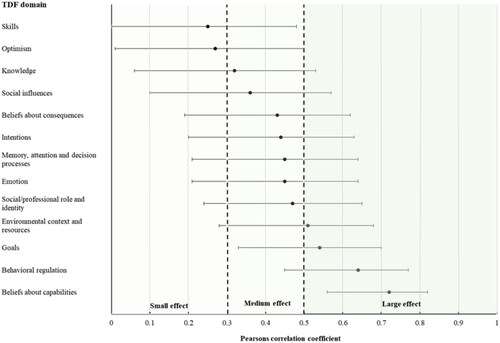

Analysis 2: Which TDF domains are more strongly associated with infant hearing aid use?

shows Pearson correlation coefficients alongside 95% confidence intervals describing the relationship between each of the TDF domains measured and parent-reported hearing aid use adjusted for child waking hours. All TDF domains were positively associated with infant hearing aid use in that lower TDF domain scores (i.e. more barriers to hearing aid use) were associated with lower hearing aid use, with differences only in magnitude of effect. The strongest associations were large-sized relationships between hearing aid use and “beliefs about capabilities” (e.g. “I am confident that I can use hearing aids with my child”) r = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.56 to 0.82, “behavioural regulation” (e.g. “I have a clear plan for when to put my child’s hearing aids on”) r = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.45 to 0.77, “goals” (e.g. “Getting my child to use hearing aids as often as advised is high on my list of priorities”) r = 0.54, 95% CI = 0.33 to 0.70, and “environmental context and resources” (e.g. “I can count on the professionals who provide services related to my child’s hearing loss to support me when things are difficult or when I need help”) r = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.28 to 0.68.

Figure 2. Correlations and 95% Confidence Intervals Between Adjusted Hearing Aid Use and TDF Domains.

Medium-sized relationships were found between “social/professional role and identity” (e.g. “Getting my child to use hearing aids as often as advised is an important part of my role as a parent”) r = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.24 to 0.65, “emotion” (e.g. “I have negative emotions when using hearing aids with my child”) r = 0.45, 95% CI = 0.21 to 0.64, “memory, attention and decision processes” (e.g. “Putting on (and switching on) my child’s hearing aids is something I do automatically without thinking”) r = 0.45, 95% CI = 0.21 to 0.64, “intentions” (e.g. “I will definitely make sure my child uses their hearing aids as often as advised”) r = 0.44, 95% CI = 0.20 to 0.63, “beliefs about consequences” (e.g. “I believe my child benefits/will benefit from using hearing aids”) r = 0.43, 95% CI = 0.19 to 0.62, “social influences” (e.g. “People who are important to me think that I should use hearing aids with my child as often as advised”) r = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.10 to 0.57′, “knowledge” (e.g. “I know how to use hearing aids with my child”) r = 0.32, 95% CI = 0.06 to 0.50, and hearing aid use. Finally, there were small relationships between, “optimism” (e.g. “Making sure my child uses hearing aids as often as advised makes me feel optimistic/hopeful about my child’s future”) r = 0.27, 95% CI = 0.01 to 0.50, and “skills” (e.g. “I have the skills to use hearing aids with my child”) r = 0.25, 95% CI = 0.00 to 0.48, and hearing aid use.

Subgroup analysis: Do parents who report higher vs. lower infant hearing aid use report differences in barriers to consistent hearing aid use?

A subgroup analysis was conducted to explore variation in barriers based on amount of hearing aid use (adjusted for child waking hours) by comparing “higher” vs. “lower” hearing aid users on parental mean TDF domain responses (see “Subgroup analysis” section of the “Materials and methods” section for details). Overall, parents who reported lower hearing aid use also tended to report stronger barriers to infant hearing use when compared to parents who reported higher hearing aid use. Specifically, there were significant differences in the medium-sized effect size range between higher and lower hearing aid users on domains of the TDF (F(1, 54) = 3.08, p < 0.05, n2 = 0.05, 95% CI = 0.00 to 0.20). Large and statistically significant effect size differences were evident between higher and lower hearing aid users on “beliefs about capabilities” (n2 = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.19 to 0.54), “behavioural regulation” (n2 = 0.25, 95% CI = 0.07 to 0.42), and “environmental context and resources” (n2 = 0.20, 95% CI = 0.04 to 0.37). Medium-sized and statistically significant differences were evident on “emotion” (n2 = 0.13, 95% CI = 0.01 to 0.30), “goals” (n2 = 0.12, 95% CI = 0.01 to 0.29), and “social influences” (n2 = 0.11, 95% CI = 0.01 to 0.27), with medium-sized non-significant differences on “memory, attention and decision processes” (n2 = 0.11, 95% CI = 0.00 to 0.27), “beliefs about consequences” (n2 = 0.09, 95% CI = 0.00 to 0.25), “intentions” (n2 = 0.07, 95% CI = 0.00 to 0.22), “skills” (n2 = 0.07, 95% CI = 0.00 to 0.23), and “knowledge” (n2 = 0.06, 95% CI = 0.00 to 0.20). Finally, small-sized and non-significant differences were evident on “social/professional role and identity” (n2 = 0.05, 95% CI = 0.00 to 0.19), and “optimism” (n2 = 0.04, 95% CI = 0.00 to 0.17).

Discussion

The present study is the first to take a theory-driven approach to investigate the potential factors that influence parents consistently implementing their child’s hearing aid use during infancy and toddlerhood. To that end, we aimed to quantify potential parent-reported barriers to hearing aid use in children under 3 years of age using the TDF, and to explore whether specific TDF domains were associated with parent-reported infant hearing aid use. Findings advance existing understanding by identifying a wider range of barriers than previously reported, within a theoretical framework that limits the risk of omitting important behavioural determinants when exploring potential drivers of consistent infant hearing aid use. Specifically, participants reported a wide range of barriers across the TDF domains; however, the most strongly reported domains were “emotion” (e.g. feelings of worry or stress when using hearing aids), “beliefs about capabilities” (e.g. belief in ability to use hearing aids consistently), and “environmental context and resources” (e.g. child taking their hearing aids out). Moreover, after comparing “lower” vs. “higher” hearing aid users, we found that parents of lower users reported most TDF domains more strongly than parents of higher hearing aid users. Finally, 10 out of the 13 TDF domains measured correlated with parent-reported hearing aid use in the medium-sized range or above, with “beliefs about capabilities,” “behavioural regulation,” “goals,” and “environmental context and resources” all within the large effect size range. Taken together, parents report a wider range of barriers to infant hearing aid use than previously reported, which are associated with infant hearing aid use, and more pronounced in parents of lower hearing aid users (relative to higher users). However, specific domains of the TDF were found to be more strongly reported, and more closely tied to infant hearing aid use, such as the emotional impact of implementing infant hearing aid use, the environmental and contextual factors associated with infant hearing aid use, and parents’ beliefs in their capability to consistently implement their child’s hearing aid use.

Existing research into factors influencing infant hearing aid use tends to use the same or similar measurement tools that tap into a subset of TDF domains, namely “environmental context and resources,” “knowledge,” and “skills” (Muñoz et al. Citation2015; Muñoz et al. Citation2016; Kelly et al., under review). Although the present study found that “environmental context and resources” was one of the most strongly reported domains, findings also revealed that, not only were “knowledge” and “skills” perceived by parents to be the least impactful, they were also amongst the weakest correlates of parent-reported hearing aid use. Certainly, knowledge and skills (e.g. knowing how hearing aids can benefit their child and having the skills to use hearing aids with their child, respectively) are important to achieving consistent infant hearing aid use; however, the present research suggests a wider range of domains more strongly influences hearing aid use during infancy and toddlerhood. Consequently, interventions that focus on a narrow subset of domains, especially knowledge and skills, may be less likely to be effective and well-received by parents.

Currently, the few existing interventions that aim to increase infant hearing aid use do indeed tend to focus on a subset of domains with considerable focus on knowledge and skills. For example, Munoz et al. (Citation2021) tested the effect of a 6-week guided video intervention, which demonstrated limited efficacy that may – at least in part – be explained by the majority of the intervention videos largely targeting knowledge and skills around: (i) practical management (i.e. procedural knowledge such as how to change the batteries etc.); (ii) the technology (e.g. hearing aid programming); and (iii) knowledge about the benefits of hearing aid use and the challenges to expect. Furthermore, the strategies used to facilitate behaviour change (i.e. behaviour change techniques) tended to be limited to increasing knowledge through information-giving, which might not be active enough to successfully change behaviour (Arlinghaus and Johnston Citation2018).

In their individualised parent education intervention, Ambrose and colleagues broaden the main domains targeted to include “beliefs about capabilities” (e.g. highlighting positive aspects of the child’s hearing aid use) and “beliefs about consequences” (e.g. video examples of a child with a similar hearing loss to illustrate the clarity of child speech that may be expected with consistent hearing aid use), in addition to “knowledge” and “skills” (Ambrose et al. Citation2020). However, the authors still only target a limited subset of the domains identified in the present study. Ambrose et al. do on the other hand, employ a wider range of behaviour change techniques that go beyond information-giving, such as tailoring specific strategies to individual families, modelling skills during intervention sessions, and providing a simulation of their child’s unaided hearing. Although findings were promising, particularly around acceptability, the single-group design and small sample size (3 participants), limits the generalisability of their conclusions. In sum, no intervention to date (to our knowledge) has used a theory informed framework to develop their intervention, meaning all potential determinants of behaviour are not considered. Moreover, without systematic use of behaviour change theory, strategies to facilitate behaviour change (e.g. modelling/demonstration of the behaviour) are often limited to those the researcher(s) intuitively perceive to be the best option and might not necessarily be the most theoretically informed or evidence-based strategies (i.e. best suited to addressing the determinants of behaviour that need to be targeted to bring about the desired behaviour change).

Implications for intervention development

The present findings suggest that future interventions would benefit from targeting a considerably wider range of TDF domains, with particular attention paid to “emotion,” “beliefs about capabilities,” “behavioural regulation,” “goals,” and “environmental context and resources”. Furthermore, future intervention development might also consider using a wider range of behaviour change techniques (i.e. intervention strategies) that go beyond information provision by continuing to draw on the principles of behaviour change theory. One such theoretical framework that might be particularly beneficial is the widely used Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW; Michie et al. Citation2014), which is a synthesis of 19 behaviour change frameworks, providing theoretically grounded core rules and principles to follow to develop an intervention. The BCW proposes intervention development starts by gaining a detailed understanding of the determinants of the target behaviour (e.g. the present research) to increase the likelihood the intervention targets the full range of barriers that families face. The framework provides a systematic method to then guide the selection of specific behaviour change techniques best suited to targeting the behavioural determinants identified using the TDF, consequently limiting the use of intuitive selection of what may be perceived to be the most effective approach.

The behaviour change techniques within the BCW framework also make explicit the exact behavioural adaptions required, increasing the chance that families are able to make the necessary behavioural adaptions. For example, in Munoz et al.’s guided video intervention (Muñoz et al. Citation2021), participants were advised to “get into a routine” to overcome some of the barriers to infant hearing aid use. However, this instruction lacked behavioural specificity (i.e. how exactly families can get into a routine), and therefore assumes the user will have the knowledge, motivation, and intention to set-up new routines. Drawing on the BCW allows for the selection of behaviour change techniques that help to make the exact behavioural adaptions required to get into a new routine explicit, such as “action planning” (e.g. planning to put child’s hearing aids on every morning before brushing their teeth) and “self-monitoring” (e.g. keeping a hearing aid use log or a daily record of whether they put their child’s hearing aids on within 10 minutes of the child waking up i.e. habit tracking).

Finally, the adaptation of the present TDF survey into a theory-driven assessment tool could also be beneficial as a component of intervention design. For example, an intervention consisting of a range of modules designed to specifically target the wide range of determinants of infant hearing use could be made tailorable to the individual needs of a family by: (i) initially identifying the family-specific barriers to infant hearing aid use via an assessment tool based on the TDF; and then (ii) assigning the appropriate modules to target the unique combination of barriers. Indeed, tailored interventions to meet individual needs is an effective approach to intervention development (Ryan and Lauver Citation2002), with preliminary evidence of high acceptability in relation to interventions designed to increase infant hearing aid use (Ambrose et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, an individualised approach fits within the values and principles outlined in the recently updated international consensus statement on best practices in family-centred early intervention for children who are deaf or hard of hearing (Moeller et al. Citation2024), specifically in relation to the provision of support that is responsive to family-identified needs and concerns, and the individual differences, strengths, and needs of children and families.

Strengths and limitations

The present research has three main strengths. First, to our knowledge, the present study is the first to explore barriers to infant hearing aid use using a theoretically driven framework. This approach has provided a more systematic and comprehensive investigation of the potential determinants of consistent parental implementation of infant hearing aid use compared to previous research and has revealed important insights in relation to the domains to target in future intervention efforts. Second, we developed a quantitative, theory-driven measurement tool with parents of infant hearing aid users and professionals who work with this demographic, which we hope will: (i) further the study of barriers to infant hearing aid use; and (ii) provide the basis for a clinical/early intervention tool to assess and target family-specific barriers. Third, some of the existing literature investigating potential factors influencing hearing aid use with young children includes parents of children within a wide age range. For example, Desjardin (Citation2005) included children aged 5 to 64 months. Investigating factors across a wide age range could be problematic, given that factors affecting hearing aid use during infancy and toddlerhood are likely to differ from those affecting hearing aid use in older children. For example, for hearing families where the child’s hearing loss is identified early (i.e. through a newborn hearing screening programme), infancy and toddlerhood are a particularly emotional time for parents (Schmulian and Lind Citation2020), when they will have less experience with hearing aids, during a time when developmental changes are most rapid. Further, young children are dependent on their parents to establish hearing aid use compared to older children who have the potential for more autonomy. Consequently, the present findings are more generalisable to a specific population that is most vulnerable in terms of the risks of inconsistent hearing aid use to spoken language outcomes (i.e. during the time most critical for spoken language development).

There are limitations to the present research that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, although the TDF survey used in the present research was developed based on established guidelines and surveys that have demonstrated psychometric validity (Atkins, Francis, Islam, O’Connor, et al. Citation2017; Huijg, Gebhardt, Crone, et al. Citation2014), and developed with parent and professional feedback, the tool has not been formally psychometrically validated. Indeed, 3 of the 13 domains had low internal reliability suggesting that future iterations of the survey should address reliability issues in these domains. Second, the present research was exploratory in nature, and represents an early first step in understanding potential factors influencing infant hearing aid use within a more systematic and theoretically informed framework. We were therefore unable to report any confirmatory findings. Nor were we able to investigate child and family characteristics known to impact hearing aid use that might moderate the relationship between TDF domains and infant hearing aid use (e.g. child’s degree of hearing loss, parents’ education level; Salamatmanesh et al. Citation2022). For example, different socioeconomic groups might experience different patterns and/or magnitudes of TDF domains that could influence hearing aid use in differential ways. Investigation into the potential impact of factors in relation to child and family characteristics would strengthen knowledge in this field. Finally, there are some inherent limitations to our sample. Specifically, the sample size was relatively small, which inhibited definitive conclusions. Furthermore, parent-reported hearing aid use was relatively high. Although we conducted subgroup analyses to explore whether barriers differed between higher and lower hearing aid users, future research could benefit from including parents of infants with a wider range of hearing aid use.

Conclusions

This is the first study to systematically and comprehensively explore factors associated with consistent hearing aid use in children under 3 years of age, using a theory-informed survey, developed in consultation with parents of infant hearing aid users and professionals working with this population. Parents are faced with a wide range of barriers to infant hearing aid use that: (i) fall across almost all domains of the TDF; and (ii) are more strongly reported by parents of infants with lower daily hours of hearing aid use (adjusted for waking hours) than those with higher hours of use. Further, barriers are wider ranging than existing research reports and current interventions address. Consequently, interventions would benefit from expanding beyond the narrow subset of domains typically targeted (e.g. knowledge and skills), to explicitly assess and target a wider range of TDF domains, particularly barriers around “emotion,” “beliefs about capabilities,” “behavioural regulation,” “goals,” and “environmental context and resources”. Moreover, the survey developed in the present study has the potential to be used to identify family-specific barriers to consistent infant hearing aid use, which in turn would allow for tailored intervention approaches that better suit specific needs.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (27.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (44.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ambrose, S. E., M. Appenzeller, S. Al-Salim, and A. P. Kaiser. 2020. “Effects of an Intervention Designed to Increase Toddlers’ Hearing Aid Use.” Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 25 (1):55–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enz032.

- Arlinghaus, K. R., and C. A. Johnston. 2018. “Advocating for Behavior Change With Education.” American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 12 (2): 113–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827617745479.

- Atkins, L., J. Francis, R. Islam, D. O'Connor, A. Patey, N. Ivers, R. Foy, E. M. Duncan, H. Colquhoun, J. M. Grimshaw, et al. 2017. “A Guide to Using the Theoretical Domains Framework of Behaviour Change to Investigate Implementation Problems.” Implementation Science: IS 12 (1):77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9.

- Bussé, A. M. L., A. R. Mackey, G. Carr, H. L. J. Hoeve, I. M. Uhlén, A. Goedegebure, and H. J. Simonsz. 2021. “Assessment of Hearing Screening Programmes Across 47 Countries Or Regions I: Provision of Newborn Hearing Screening.” International Journal of Audiology 60 (11): 841–848. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2021.1897170.

- Cane, J., D. O'Connor, and S. Michie. 2012. “Validation of the Theoretical Domains Framework for Use in Behaviour Change and Implementation Research.” Implementation Science: IS 7 (1):37. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-37.

- Cowdell, F., and J. Dyson. 2019. “How is the Theoretical Domains Framework Applied to Developing Health Behaviour Interventions? A Systematic Search and Narrative Synthesis.” BMC Public Health 19 (1):1180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7442-5.

- Desjardin, J. L. 2005. “Maternal Perceptions of Self-Efficacy and Involvement in the Auditory Development of Young Children with Prelingual Deafness.” Journal of Early Intervention 27 (3): 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/105381510502700306.

- Dupoux, E., E. L. Newport, D. Bavelier, and H. J. Neville. 2001. “Critical Thinking about Critical Periods: Perspectives on a Critical Period for Language Acquisition.”

- Giles, E. L., F. Becker, L. Ternent, F. F. Sniehotta, E. McColl, and J. Adams. 2016. “Acceptability of Financial Incentives for Health Behaviours: A Discrete Choice Experiment.” PLoS One 11 (6): e0157403. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157403.

- GOV.UK. 2023. DHSC’s areas of research interest [Internet]. [cited 2023 Mar 28]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/department-of-health-areas-of-research-interest/department-of-health-areas-of-research-interest

- Hoskins, K., C. M. Ulrich, J. Shinnick, and A. M. Buttenheim. 2019. “Acceptability of Financial Incentives for Health-Related Behavior Change: An Updated Systematic Review.” Preventive Medicine 126: 105762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105762.

- Huijg, J. M., W. A. Gebhardt, E. Dusseldorp, M. W. Verheijden, N. van der Zouwe, B. J. C. Middelkoop, and M. R. Crone. 2014. “Measuring Determinants of Implementation Behavior: Psychometric Properties of a Questionnaire Based on the Theoretical Domains Framework.” Implementation Science: IS 9 (1): 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-9-33.

- Huijg, J. M., W. A. Gebhardt, M. R. Crone, E. Dusseldorp, and J. Presseau. 2014. “Discriminant Content Validity of a Theoretical Domains Framework Questionnaire for Use in Implementation Research.” Implementation Science: IS 9 (1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-9-11.

- JASP Team 2022. JASP (Version 0.16.1)[Computer software] [Internet]. https://jasp-stats.org/

- Kelly, C. CHerUB (Consistent Hearing aid Use in Babies) [Internet]. [cited 2023 Nov 28]. https://www.cherubproject.co.uk/

- Kelly, C., C. J. Armitage, S. Rudman, I. Almufarrij, A. S. Visram, and K. J. Munro. “Consistent Hearing aid Use in Babies (CHerUB): A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Barriers and Facilitators Using the Theoretical Domains Framework.” Under review.

- Kline, P. 1999. The Handbook of Psychological Testing. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Kuhl, P. K. 2004. “Early Language Acquisition: Cracking the Speech Code.” Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 5 (11):831–843. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1533.

- McCreery, R. W., E. A. Walker, and M. Spratford. 2015. “Understanding Limited Use of Amplification in Infants and Children Who Are Hard of Hearing.” Perspect Hear Hear Disord Child 25 (1): 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1044/hhdc25.1.15.

- McCreery, R. W., E. A. Walker, M. Spratford, R. Bentler, L. Holte, P. Roush, J. Oleson, J. Van Buren, and M. P. Moeller. 2015. “Longitudinal Predictors of Aided Speech Audibility in Infants and Children.” Ear and Hearing 36 (Suppl 1): 24S–37S. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000211.

- Michie, S., L. Atkins, and R. West. 2014. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. London: Silverback Publishing.

- Moeller, M. P., E. Gale, A. Szarkowski, T. Smith, B. C. Birdsey, S. T. F. Moodie, G. Carr, A. Stredler-Brown, C. Yoshinaga-Itano, D. Holzinger, et al. 2024. “Family-Centered Early Intervention Deaf/Hard of Hearing (FCEI-DHH): Introduction.” Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 29 (SI):SI3–SI7. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enad035.

- Muñoz, K., G. G. San Miguel, T. S. Barrett, C. Kasin, K. Baughman, B. Reynolds, et al. 2021. “eHealth Parent Education for Hearing Aid Management: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial.” Int J Audiol 60 (sup1): S42–S8. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2021.1886354.

- Muñoz, K., S. E. P. Rusk, L. Nelson, E. Preston, K. R. White, T. S. Barrett, and M. P. Twohig. 2016. “Pediatric Hearing Aid Management: Parent-Reported Needs for Learning Support.” Ear and Hearing 37 (6): 703–709. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000338.

- Muñoz, K., W. A. Olson, M. P. Twohig, E. Preston, K. Blaiser, and K. R. White. 2015. “Pediatric Hearing Aid Use: Parent-Reported Challenges.” Ear and Hearing 36 (2): 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000111.

- Payton, M. E., M. H. Greenstone, and N. Schenker. 2003. “Overlapping Confidence Intervals or Standard Error Intervals: What Do They Mean in Terms of Statistical Significance?” Journal of Insect Science (Online) 3 (1): 34. https://doi.org/10.1093/jis/3.1.34.

- Ryan, P., and D. R. Lauver. 2002. “The Efficacy of Tailored Interventions.” Journal of Nursing Scholarship 34 (4): 331–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00331.x.

- Salamatmanesh, M., L. Sikora, S. Bahraini, M. MacAskill, J. Lagace, T. Ramsay, and E. M. Fitzpatrick. 2022. “Paediatric Hearing Aid Use: A Systematic Review.” International Journal of Audiology 61 (1): 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2021.1962014.

- Scheel, A. M., L. Tiokhin, P. M. Isager, and D. Lakens. 2021. “Why Hypothesis Testers Should Spend Less Time Testing Hypotheses.” Perspectives on Psychological Science: a Journal of the Association for Psychological Science 16 (4): 744–755. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620966795.

- Schmulian, D., and C. Lind. 2020. “Parental Experiences of the Diagnosis of Permanent Childhood Hearing Loss: A Phenomenological Study.” International Journal of Audiology 59 (1): 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2019.1670364.

- Sininger, Y. S., K. J. Doyle, and J. K. Moore. 1999. “The Case for Early Identification of Hearing Loss in Children: Auditory System Development, Experimental Auditory Deprivation, and Development of Speech Perception and Hearing.” Pediatric Clinics of North America 46 (1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70077-8.

- Skivington, K., L. Matthews, S. A. Simpson, P. Craig, J. Baird, J. M. Blazeby, K. A. Boyd, N. Craig, D. P. French, E. McIntosh, et al. 2021. “A New Framework for Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: Update of Medical Research Council Guidance.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.)374: n2061. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2061.

- Szucs, D., and J. P. Ioannidis. 2017. “When Null Hypothesis Significance Testing is Unsuitable For Research: A Reassessment.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 11: 390. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00390.

- Tomblin, J. B., M. Harrison, S. E. Ambrose, E. A. Walker, J. J. Oleson, and M. P. Moeller. 2015. “Language Outcomes in Young Children with Mild to Severe Hearing Loss.” Ear and Hearing 36 (Suppl):76S–91S. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000219.

- Visram, A. S., A. J. Roughley, C. L. Hudson, S. C. Purdy, and K. J. Munro. 2021. “Longitudinal Changes in Hearing Aid Use and Hearing Aid Management Challenges in Infants.” Ear and Hearing 42 (4): 961–972. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000986.

- Von Elm, E., D. G. Altman, M. Egger, S. J. Pocock, P. C. Gøtzsche, and J. P. Vandenbroucke. 2007. “The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies.” Annals of Internal Medicine 147 (8): 573–577. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010.

- Walker, E. A., R. W. McCreery, M. Spratford, J. J. Oleson, J. Van Buren, R. Bentler, P. Roush, and M. P. Moeller. 2015. “Trends and Predictors of Longitudinal Hearing Aid Use for Children Who Are Hard of Hearing.” Ear and Hearing 36 (Suppl 1): 38S–47S. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000208.