abstract

Background: Participation of parents during their adolescent’s detention is important for achieving positive treatment outcomes for youths and their families. To improve parental participation, insight in facilitating or hindering factors is necessary. To this end, we studied the perspectives of parents of adolescents detained in two juvenile justice institutions in the Netherlands.

Methods: Data were collected from 19 purposefully selected parents through semi-structured interviewing. The interviews were transcribed verbatim and imported into ATLAS.ti where data were coded and analyzed.

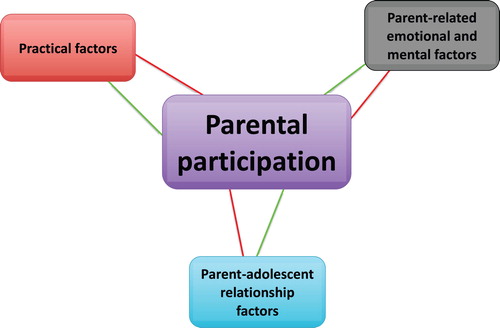

Results: Parental participation is influenced by a variety of factors that could be categorized based on the following themes: (1) practical facilitating or obstructing factors; (2) parent-related emotional and mental factors; and (3) factors concerning issues of the parent-adolescent relationship.

Discussion: Insight into the factors which facilitate and obstruct participation might help JJI staff understand differences in parental participation. This may enable them to tailor solutions which would improve parental participation during their adolescent’s detention.

Introduction

The involvement of parents during their adolescent’s detention is important for achieving positive child and family outcomes concerning both mental health issues as well as behavioral aspects (Burke, Mulvey, Schubert, & Garbin, Citation2014; Latimer, Citation2001; Monahan, Goldweber, & Cauffman, Citation2011; Woolfenden, Williams, & Peat, Citation2002). For example, parental participation is likely to result in better insight in the nature of the youth’s problems, which would result in better treatment for the adolescent and a smoother transition back into the community (Garfinkel, Citation2010).

Until recently in the Netherlands, youth detention centers, called Juvenile Justice Institutions (JJIs), were unable to reach satisfying levels of parental involvement (Sectordirectie Justitiële Jeugdinrichtingen, Citation2011; Simons et al., Citation2016, Citation2017; Vlaardingerbroek, Citation2011). This struggle is not surprising, as JJIs originally were not focused on collaborating with parents. JJIs traditionally were oriented toward reducing criminal behavior and protecting society by providing individual treatment to adolescents.

Realizing the importance of involving families during adolescents’ detention to ensure successful reintegration, JJIs in the Netherlands began to implement some family-oriented activities in their usual care program (Stuurgroep YOUTURN, Citation2009). Although this integration of family-oriented activities introduced a paradigm shift and was (in theory) a good start to involving parents, the program did not contain a wide range of options for parental participation, and the objectives were neither well-translated nor well-implemented. This failure to put plans into practice resulted in poorly embedded parental participation (Hendriksen-Favier, Place, & Van Wezep, Citation2010). In a new effort to improve this situation, the Netherlands Government issued a national position paper in 2011 encouraging JJIs to improve parental participation (Sectordirectie Justitiële Jeugdinrichtingen, Citation2011).

However, this article only contained broad outlines which every JJI needed to detail for implication in everyday practice. Additionally, youths are placed in JJIs after ruling of a juvenile judge, under the suspicion of, or after conviction for, criminal behavior. Accordingly, placement is mandatory in which neither youths nor parents have a say, and parents are forced to deal with a situation where their adolescent is detained after (possibly) having committed a crime (Janssens, Citation2016). Consequently, welcoming parents to a place where their adolescent is being held against both the parents’ and the youth’s wills, is somewhat paradoxical and thus challenging for JJIs. To provide JJIs with clear guidelines on how to improve parental involvement and participation during the detention of a juvenile, the Academic Workplace Forensic Care for Youth (in Dutch: AWFZJ, www.awrj.nl) took up the challenge to develop a program for Family-centered Care in JJIs (Mos, Breuk, Simons, & Rigter, Citation2014; Simons et al., Citation2017).

In order to improve the participation of parents during their adolescent’s detention, we must understand which factors promote or hinder their participation. One important but under-researched source of information concerns the parents’ own views of these factors. Knowledge of parents’ perspectives might help JJI staff to apply better-suited strategies to convince parents to participate during the detention period. According to our knowledge, such qualitative research among parents, especially in JJIs, is scarce. Furthermore, factors that have previously been described in literature usually stem from other forms of residential treatment centers focused on, for example, mental retardation, psychiatric disorders, or younger children (Baker & Blacher, Citation2002; Knecht & Hargrave, Citation2002; Schwartz & Tsumi, Citation2003; Sharrock, Dollard, Armstrong, & Rohrer, Citation2013). We will elaborate on these factors below, on which we will build our qualitative study.

The factors described in the literature could be categorized into three types of factors: (1) personal or situational factors; (2) child or youth factors; and (3) facility factors. Regarding the first category, long distance between home and the facility has been shown to hinder parents’ visits (Baker & Blacher, Citation2002; Kruzich, Jivanjee, Robinson, & Friesen, Citation2003; Lyman & Campbell, Citation1996; Sharrock et al., Citation2013), while living closer to the facility was an expedient for visiting (Baker, Blacher, & Pfeiffer, Citation1996; Robinson, Kruzich, Friesen, Jivanjee, & Pullman, Citation2005). Related to travel distance, transportation also seems to influence parental participation. Specifically, participation is shown to be negatively influenced by a lack of transportation availability and by the expense of transportation (Garfinkel, Citation2010; Kruzich et al., Citation2003; Sharrock et al., Citation2013).

Other previously identified barriers all consist of parental burdens. For example, lack of childcare for other children, competing demands or constraints on time (e.g., work), parents’ own emotional problems, and medical concerns all have been found to negatively influence parental participation (Burke et al., Citation2014; Garfinkel, Citation2010; Lyman & Campbell, Citation1996; Sharrock et al., Citation2013). Additionally, parents might be less willing to participate because of disappointingly negative previous experiences with service providers (Garfinkel, Citation2010; Knecht & Hargrave, Citation2002). With regard to the influence of marital status, previous research has reached contradictory findings. For example, while Baker, Blacher, and Pfeiffer (Citation1993; Baker et al., Citation1996) showed that intact marriages facilitate visiting, and Robinson et al. (Citation2005) found that single parenthood obstructs it, Kruzich et al. (Citation2003) concluded that parents’ marital status is of no influence on involvement.

With regard to the second category, “child or youth factors”, previous studies have shown that facilitating factors for parental involvement are higher IQs and lower ages of the parents’ children (Baker & Blacher, Citation2002; Baker et al., Citation1993; Kruzich et al., Citation2003; Robinson et al., Citation2005). Research on other child or youth factors is less conclusive about their influence. Some studies found that high levels of their child’s mental problems hinder parental participation (Baker & Blacher, Citation2002; Baker et al., Citation1993; Schwartz & Tsumi, Citation2003), while Kruzich et al. (Citation2003) concluded that the severity of the child’s mental health problems are not related to parents’ involvement. Another contradictory finding concerns ethnicity. Kruzich et al. showed that the child’s ethnic background is not influential, while Baker et al. (Citation1993) have concluded that parents of children with white ethnic backgrounds are more involved, and others found that parents of African American and Hispanic ethnic youths are less involved (Monahan et al., Citation2011). A third contradiction in finding concerns duration of the child’s stay. While Baker and Blacher (Citation2002) and Schwartz and Tsumi (Citation2003) have shown that longer duration of stays obstruct parental involvement, Baker et al. concluded that the duration of the child’s stay is not related to parental involvement.

As for the third category, “facility factors”, the flexibility of the system, availability of staff, responsiveness to cultural values, and staff members’ attitudes and behaviors can either facilitate or hinder parental participation (Burke et al., Citation2014; Garfinkel, Citation2010; Knecht & Hargrave, Citation2002; Kruzich et al., Citation2003; McNown Johnson, Citation1999). Other facility factors have been shown to negatively influence parental participation, i.e., a high staff turnover and restrictive policies (Degner, Henriksen, & Oscarsson, Citation2007; Kruzich et al., Citation2003).

The effect of hindering and protective factors, respectively, appears to be cumulative (Kruzich et al., Citation2003). On one hand, the more barriers parents experienced during their child’s residential treatment, the less contact they had with their child and the less the parents participated. On the other hand, the more support parents experienced from the facility, the more contact they had with their child and the more they participated in educational and treatment planning (Kruzich et al., Citation2003).

Knowledge about factors promoting or hindering parents to participate during their child’s out-of-home care stems predominantly from other forms of residential treatment centers (e.g., psychiatric hospitals, centers for people with intellectual disabilities, group homes, or out-of-home treatment facilities). This is quite different from a forensic setting such as the JJI, where adolescents are placed involuntarily because of (suspected) criminal behavior. Placement of a youth into a JJI is always preceded by the ruling of a juvenile judge. Hence, the setting of a JJI differs from that of other forms of residential treatment in regard to population, length of stay, and legal framework (Simons et al., Citation2018). Therefore, whether the same factors apply to parents whose adolescents are detained in a JJI after being suspect of, or convicted for, criminal behavior, is of interest for study.

Hence, our study aims to investigate which factors influence parental participation during their adolescent’s detention by interviewing parents themselves. The responses of these parents will reveal the unique perspectives of parents, which will be informative for policy-making and the training of staff working in JJIs. Qualitative research is particularly suitable for obtaining parents’ own views and for shedding light on what is behind the previously described contradictory findings. By considering factors that parents deem influential to their participation, JJI staff will be able to better respond to parents’ needs. This has the potential to help improve parental participation during their adolescent’s detention, which might contribute to improved treatment outcomes.

Methods

This study is part of a larger study on Family-centered Care in JJIs, the full design of which, including the current study, has recently been published (Simons et al., Citation2016). That published paper offers a detailed explanation of the setting of our study, which was carried out in the two JJIs in the Netherlands which participated in the Academic Workplace Forensic Care for Youth.

The current study took place with five short-term detention groups, where male adolescents reside for a maximum period of 90 days, awaiting the final ruling of the juvenile judge. Female adolescents were not placed in the two JJIs participating in the Academic Workplace Forensic Care for Youth. Consequently, only parents of male adolescents were able to participate in our study. Two groups in the JJIs recently took the first steps toward implementing the Family-centered Care program (Mos et al., Citation2014; Simons et al., Citation2017) and the three other groups worked according to the JJI’s usual care. Because the JJIs are required to fill free slots in the living groups upon the arrival of new adolescents, the assignment of adolescents to the groups is without bias (Simons et al., Citation2016).

Recruitment

Parents received a flyer with information about the current study in the information leaflets from the JJI. As part of the practice-based nature of our study, we established exclusion criteria for our qualitative study in close collaboration with the psychologists assigned to the living groups of the youths. The psychologists based their advice on their clinical judgment, bearing in mind preventing the risk of overload for the parents or parents that required a specialized approach, which made them unsuited for participation in our study. Parents were included unless they met the exclusion criteria. Based on the advice of the psychologists, criteria for excluding parents were if: (a) their adolescent left the short-term detention group within two weeks; (b) their adolescent was only temporary transferred to this JJI after an incident in a different JJI; (c) parents or their adolescent had severe mental health problems (i.e., psychosis, acute suicidal behaviors, severe mental retardation, autism) as assessed by the JJI’s psychologist overseeing the adolescent’s treatment; and (d) their adolescent was suspected of having committed a sexual offense.

If parents did not meet the exclusion criteria, we called them to explain the study and asked them if they were willing to be interviewed. Participation was voluntary, and parents were informed that they could withdraw from the interview whenever they wanted, without having to give a reason. If parents agreed to take part, we scheduled an interview at home or in the JJI, as chosen by the parents. Additionally, we followed the respondents’ preference regarding individual interviews or interviews with mothers and fathers simultaneously if this made parents more willing to participate. After the interview, parents were thanked for contributing to the study by a small gift such as a mug filled with chocolates and a personal “thank you” note.

Participants

We aimed to include a heterogeneous group of parents and/or caregivers (from here on referred to as parents) to obtain a broad spectrum of perspectives of parents whose adolescents were placed in JJIs. As parents were excluded if their son stayed less than two weeks in the short-term detention group, all parents already had some experience with the JJI. In total, we interviewed 19 parents in 14 interviews; six mothers, two fathers, one sister who was responsible for parenting her brother, and five pairs of mothers and fathers together (of which one couple were foster parents). In two interviews, a daughter or daughter-in-law of the respondent served as an interpreter for non-Dutch speaking parents. At the beginning of the interview, the parents filled out a short questionnaire about demographic background variables. For demographic characteristics of the respondents, see . One father did not fill out the demographic questionnaire, so his data are listed as missing.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the interviewed parents.

Procedure

The interviews were carried out by three students enrolled in their last year of the Bachelor’s program in Social Work or Applied Psychology, under supervision of a Ph.D. candidate who is a licensed psychologist. Each interviewer received substantial training in qualitative interviewing techniques and additional training was provided on issues related detention and safety. The supervising Ph.D. candidate either accompanied a student during an interview, or was available for support via telephone. After each interview, evaluation meetings were scheduled. Additionally, the interviewers registered reflective notes after each interview and again when they had transcribed the interviews verbatim. Because of this verbatim transcription, the quotes as used in our “Results” section contain the literal wordings as used by the parents. This ensures that the quotes represent the voices of parents and avoids the risk of interpretation bias. Since not all parents were native Dutch speakers, sentences were sometimes not completely fluently. When translating the quotes to English, we have opted for the same strategy and stayed as close as possible to the original sentences as verbalized by the parents.

The interviews lasted between 60 and 90 minutes and were audio-recorded, for which parents were asked for verbal permission. Parents were informed that the recording could be stopped during the interview on request. Respondents of two interviews did not want their interview to be audiotaped. With parents’ consent, the interviewers wrote down the answers of these respondents as comprehensively as possible.

The interviews were semi-structured, using a topic list. This list was drafted following deductive and inductive strategies. Deductively, we first reviewed literature on factors influencing parental participation in out-of-home facilities as discussed in the introduction. Additionally, the four categories of parental participation as distinguished by the Family-centered Care program (Mos et al., Citation2014; Simons et al., Citation2017) were also added to the topic list. Then, more inductively, we noted the experiences of JJI staff and of parents in the pilot phase of our study (Simons et al., Citation2016). These notes gave input to designing the topic list. Moreover, the topic list was supplemented after a try-out interview with a representative of the Dutch parent association for children with developmental disorders and educational or behavioral problems, whose son had previously been detained. Finally, purely inductively, if new themes arose in the interviews, they were used to supplement the topic list. The main themes of the final topic list are summarized in . Although the topics follow a thematically logical order, the topic list was employed with flexibility, guided by the answers of the parents (Silverman, Citation2010).

Table 2. Main themes of the topic list for interviewing parents including the follow-up topics.

The verbatim-transcribed interviews were imported into ATLAS.ti. For coding and analyzing our data, we used inductive and deductive strategies as widely recommended in qualitative research (Boeije, Citation2012; Flick, Citation2018; Lucassen & Olde Hartman, Citation2007; Miles, Huberman, & Saldana, Citation2014; Peters & Wester, Citation2007). We used a code tree, which represented the themes in the topic list and which was supplemented with new themes arising from the interviews. The first author and the students worked in a cyclical process. The first phase of open coding, in which interview fragments were linked to codes, was followed by a second phase of axial coding. In this axial coding phase, codes were further interpreted and reorganized based on the interview fragments they referred to. In this phase, codes were split, merged, and combined into more abstract central themes. Code families were constructed for further analysis. In the final phase of selective coding, we found more general patterns in the data using theoretical interpretation (Boeije, Citation2010). This analytic process enabled us to explain which factors parents believe to influence their participation.

Ethics

The medical ethical board of the Leiden University Medical Center reviewed our study. The board ruled that our study falls outside the realm of the WMO (Dutch Medical Research in Human Subjects Act) and that it conforms to Dutch law, including ethical standards.

Results

When asking parents about factors influencing their participation during their adolescent’s detention in the JJI, three themes emerged: (1) practical factors, (2) parent-related emotional and mental factors, and (3) factors concerning issues of the parent-adolescent relationship; see .

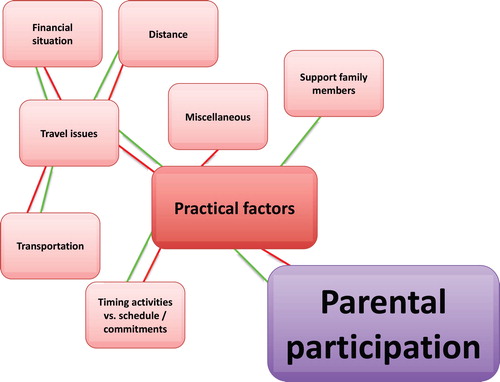

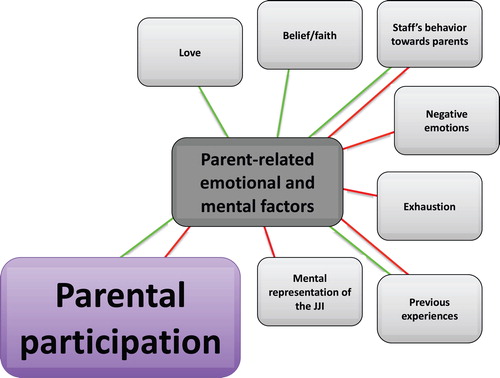

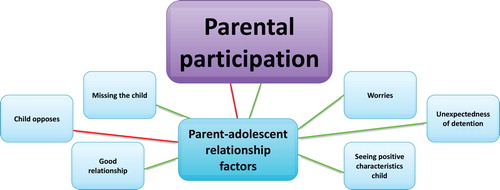

Each domain contained both facilitating and obstructing factors. Facilitating factors contribute to parental participation, whereas obstructing factors hinder it. These factors are summarized in a figure for each theme after which the detailed results will be presented.Footnote1 In the figures, the green lines represent a facilitating effect on parental participation, and the red lines symbolize an obstructing effect.

Practical facilitating or obstructing factors

In the interviews, parents came up with much more obstructing than facilitating practical factors. displays a summary of the factors mentioned by parents. The green lines represent a facilitating effect on parental participation, and the red lines symbolize a hindering effect. We will elaborate on each factor below.

Most parents explained that traveling to the JJI costs money and they considered this to impede parents from visiting the JJI because of their financial problems. Some parents felt relieved that they are not facing financial problems themselves, while at the same time understanding how this could be a problem for other parents.

“And perhaps they don’t own a car because they don’t have the money for it. So that would be an obstacle for someone who doesn’t have money. Our son is just lucky that we’re both employed and are able to visit him each week, but there are also many parents, and sometimes I’m concerned about those parents. I think it’s sad that they’re not able to come because, of course they want to see their child every week. So that’s an obstacle for them. And that’s sad for the child. Because of course he’s always longing for that one visit lasting that one hour.” (P4)

Although providing parents compensation for their travel expenses could stimulate a parent to visit the JJI, another parent stated that having to pay the travel costs in advance and having to wait a while for receiving the compensation, combined with the administrative hassle, still did not stimulate her.

Moreover, other related travel issues prevented parents from visiting the JJI as well. For example, half of the parents expressed that not having transportation or not having a driver’s license is problematic for reaching the JJI. At the same time, some parents mentioned that having a car actually facilitate their visits. Public transportation did not seem like a solution for parents who do not own a car, since almost half of the parents experienced that the JJI is not well connected by public transportation.

“Some people don’t have a car. They have to travel by train or with the bus. But the bus doesn’t stop here I think […] So you just need a car.” (P6)

One parent elaborated that especially in the winter when darkness came early, the long walks to reach the bus stop were uncomfortable. On the other hand, a few parents considered support from family members in driving them to the JJI to promote their visits. Another parent explained that she was pleased that the JJI had enough parking spaces and that parking was free of charges. She thought that this stimulated parents to visit the JJI.

To stimulate parents for visiting the JJI, one parent suggested that JJIs provide a shuttle bus and coordinate carpool opportunities among parents.

The long distance from home to the JJI was another practical, travel-related hindering factor that was cited by most parents. That said, two parents stated that no matter how long they had to travel, they would always visit the detained adolescent.

“[He –the youth- said] ‘because in that case you won’t have to come, […] as you need to travel for so long. So I said: ‘Are you crazy or what?’. Yes, he is also worried about us. […] I really don’t care if I have to travel for two hours or not, for him I will do that for sure. Even if he was, say, in another country, I really wouldn’t care.” (P3)

Most parents also identified the mismatch between the timing of the activities in the JJI and their own schedule as a practical hindering factor. Parents often had other commitments such as work, school, or volunteerships. One parent said that having a flexible employer and understanding colleagues helped her adjusting her schedule to that of the JJI. Some parents explained how not being employed actually promoted their participation in the JJI, because they had more time available and no work obligations. Two other parents mentioned being too busy keeping the rest of the family life on track, and about half of the parents thought that having small children at home who need a babysitter made it harder to visit the JJI. With regard to babysitting, two parents explained how the support of family members would be helpful for babysitting younger children. The following practical factors negatively influenced participation, according to parents, each have been mentioned once by a different parent: not having a valid ID card (required to visit the JJI), having physical difficulties, or being divorced and not having a positive relationship with the ex-partner (thus requiring extra planning if parents want to divide activities in the JJI between themselves).

Parent-related emotional and mental factors

displays a summary of the parent-related emotional and mental factors mentioned by parents. Again, the green lines represent a facilitating effect on parental participation, and the red lines symbolize a hindering effect. We will elaborate on each factor below.

Figure 3. Parent-related emotional and mental factors influencing parental participation according to parents.

In most interviews, parents expressed their love for their adolescent and their internal drive to see him. The connection they had with their son and their wish to support him motivated parents to participate during his detention.

“Because he is part of a family, he is family. He absolutely should not think that he is alone. Because he definitely is not. He has got his mother and his sisters.” (P3)

Almost half of the parents explained that having faith in their adolescent and believing that things will be all right in the future helped to motivate them to visit the JJI.

Other than that, parents mainly listed personal factors that negatively influenced their motivation to participate. For example, almost all parents explained how the detention of their adolescent elicited a variety of negative emotions for them. These emotions included anger, shame, and disappointment.

“You felt all of these emotions at the same time. You felt anger, you felt outraged, you felt sad. Actually, you’re living in a daze.” (P4)

Additionally, a few parents described feeling exhausted after all the worries they had about their son or after trying to seek the right help for him. Almost half of the parents explained that their adolescent’s detention was very hard, painful, and stressful for them. One parent even received psychological support for feeling very tense because having a son in detention was too stressful.

“I find it very tough, yes. When I enter the door, and oh, it’s in my head. I cannot continue my live after that, it is hard. I’m completely locked down. I take the whole building home with me that day.” (P6)

Some of the parents in our sample had a negative mental representation of the JJI, which caused some of them to fear entering the JJI. These negative representations were caused by negative stories they had heard about the JJI, media that portrayed JJIs negatively, movies about prisons, or a negative feeling they got from passing by prisons in the Netherlands. Additionally, the concept of visiting their son in detention could be very confronting for parents. Although all these negative emotions or ideas about the JJI did not stop parents in our sample from wanting to visit the JJI, it did make visiting more difficult, because parents had to overcome their first tendency to avoid it.

“It is easier not to go. Because when you do go, you’re faced with what your child has done. And that can be painful. And it is painful indeed. But then at some point, you’re able to process what has happened. I haven’t processed it yet but I’m working on it. Together with my son.” (P9)

Even though a few parents sometimes felt fed up with their adolescent, all parents in our sample continued to support him.

“But I have always said: ‘Okay, it is not okay what you have done, but no matter what, I will always have your back. After all, you are my child; you will continue to be my child’.” (P9)

Beside negative emotions elicited by their son’s detention, one parent described also feeling relieved about the situation at the same time:

“But I think that our situation was quite different, because we were actually experiencing lots of parenting stress. And now we’re glad to be able to catch our breaths […] and calm down. For us it’s just some time to find rest. And sitting peacefully in your room and not having to think all the time: ‘Well, how is he behaving, what is he doing, why isn’t he home yet?’. So actually for us, it’s a little bit of a relief that he’s over there.” (P5)

Previous experiences further influenced parents’ motivation for participation. For example, more than half of the parents described negative encounters with service providers, such as child welfare agencies, other youth care institutions, or previous therapists. These parents were disappointed in the previous service providers, which gave them pause when dealing with JJI staff.

“When things outside are going a little bit wrong with institutions and they don’t communicate well with each other, as a mom, you start to feel a bit desperate. Then there’s too much to handle.” (P9)

Although these negative experiences might hinder parents to participate in activities in the JJI, half of these parents emphasized that they were willing to give JJI staff a chance and that the previous negative experiences did not stop them from wanting to be involved during their son’s detention. One parent specified that after years of disappointment with service providers, she hoped that finally someone would be able to provide the right help for her son. Two other parents spoke up about how positive previous experiences with service providers stimulated them to collaborate with JJI staff and to participate in activities, but one of these parents explained that there would always be some degree of mistrust against the JJI.

“We have had previous experiences with youth care, also for my son. They communicated very well with me and I had faith in the service provider. I dared to join the discussion. […] I trust the JJI enough to share some things, but there’s a reason why I did not want this conversation to be recorded. A certain degree of insecurity and mistrust continues to prevail.” (P10)

Another parent mentioned distrust of the effects of detention. He stated that people learn nothing from the experience. As he had been imprisoned as well, he did not feel the need to see that world anymore. Consequently, he was less motivated to participate during his son’s detention. Other parents explained in which ways they would not like staff to behave, because they assumed that it would cause parents to refrain from participation. For example, one parent mentioned not wanting to be criticized for parenting efforts, and two others were not pleased when the JJI canceled a visit or changed the visiting hour at the last minute.

Factors concerning issues of the parent-adolescent relationship

Regarding parent-adolescent relationship factors, parents mentioned more factors facilitating their participation (green lines) instead of hindering it (red lines); see .

Figure 4. Factors concerning issues of the parent–adolescent relationship influencing parental participation according to parents.

In general, most parents described that having a good relationship with their adolescent motivated them to participate with the JJI. More than half of the parents explained that missing their son stimulated them to participate because this meant more contact with their son.

“My family unfortunately isn’t complete at this moment. And we are all very much sorry about this. It’s very difficult. It’s such a big loss not having him around.” (P10)

Some parents specified that not only they missed the youth, but also siblings wanted to spend time with their brother. One parent however stressed that every visit caused her and her son to miss each other more. This led her to consider decreasing her visits to avoid this feeling.

Another reason for collaborating with the JJI mentioned by almost half of the parents was worry for their adolescent. For example, one parent explained that because of her son’s psychopathology, she was more worried about him and wanted to make sure that he was doing all right. Therefore, she participated more in the JJI because this provided her with the opportunity to observe her son, help him, and advise JJI staff on how to deal with her son.

“I picked up the signal [that the boy was not feeling fine]. And when I called [JJI staff]: ‘No, he is doing completely fine’. And I do know certain things, sometimes you do have those kinds of contacts and you know your son. So I think: ‘No, he is not doing fine. He is trying to stand strong’.” (P1)

In half of the interviews, parents described how kind, loving, and gentle their son was.

“He is, believe it or not, he is really […] extremely helpful. If he sees that you’re in pain, and that you’re crying, he feels you. I’m almost getting tears in my eyes now. He will come to you, tells me: ‘darling, are you okay? […] Okay wipe your tears and we’ll do something fun’. He’ll take you to the city. He wants to comfort you. He helps in the kitchen, he helps in housekeeping.” (P8)

They elaborated that their son could get into trouble because he was such a helpful person. Some parents explained that their son needed to learn to better assess whether he should help someone or whether or not he should get involved. Seeing these positive characteristics of their adolescent motivated these parents to visit the JJI for activities with their son.

“It’s just a very bad decision of him. But it doesn’t make him a bad person.” (P4)

For half of the parents the arrest of their adolescent was unexpected. This appeared to stimulate parents’ interest in participation, because it helped some of the parents ascribe the cause of their son’s offense to the bad influence of his peers.

“And the shock of course, because you think ‘heh?!’ You think you know your son and then all of a sudden he is doing this. And then you think ‘How can this happen?’. You then ask yourself as a parent ‘Did I miss something? Where did I fall short?’. Because I think, yeah, I’m at home a lot, we have always had a good relationship as well. But well, I’m of course not the only one who’s telling him things, and he meets other boys and he is pretty easy to influence.” (P4)

Some parents described that if their adolescent expressed regrets for his criminal behavior, they were more willing to participate during his detention. Two parents explained that their son was not able to foresee all the consequences of breaking the law. Moreover, two parents suggested that the severity of the crime might influence parents’ motivation for participation as well. A few parents describe how their support might be less in the case of multiple arrests of their adolescent.

“Perhaps also the offense committed […]. I don’t know if this – how serious the situation can be. It could be that parents think: ‘Okay, you have done something; we are not going to be around for a while. So you can really think about what you’ve done’. My ex-partner is an example of this.” (P11)

According to some parents, objection by the detained adolescent to parental participation was an obstructing factor. Parents noticed that their son was embarrassed about his living situation, or did not want to trouble their parents with overcoming challenges to visit the JJI.

“He [the son] said: ‘I don’t want you to come here with all these boys and have dinner’. ‘Why? What would they do to us?’ ‘Well, no, some of them eat really gross’. […] Well, on the one hand I think: ‘Who cares, whatever he does or does not think, I’m just coming’. But on the other hand, no, because I don’t want him to be angry, and that he’ll be a bit infuriated about these things. That’s not what I want either. I don’t want him thinking ‘They have seen me here like this’, I don’t want him to feel bad about it. That’s why on the other hand, I don’t want it.” (P3)

One parent elaborated that if the adolescent has to stay longer in the JJI, the resistance of the adolescent would be ignored as the parent deemed it important to participate. Finally, one parent explained she thought it was better to refrain from visiting her son because of the security measures. Adolescents could be confronted with body inspections after a visit. This mother explained that she does not want to put her son through the embarrassment of having to bend over just because she visited him.

Discussion

To increase parental participation, it is important to understand which factors are facilitating or hindering for parents. Most previous research on factors influencing parents’ participation was carried out in residential settings other than JJIs. As the setting of the JJI is different from that of other residential facilities, one cannot simply assume that the same factors play a role. After all, JJIs traditionally have an individual-oriented approach, stays are involuntarily, and they are always part of the judicial system after the ruling of a juvenile judge. Therefore, we interviewed parents whose adolescents were detained to learn about their experiences regarding such factors. While our study shows that the juridical setting of the JJI, compared to other residential settings, brings along different factors that influence parental participation, our study also confirms that several factors play a similar role. For example, as previously found in other residential settings, longer distance to home, lack of transportation, negative previous experiences, parental burdens, and competing demands (Baker & Blacher, Citation2002; De Boer, Cameron, & Frensch, Citation2007; Garfinkel, Citation2010; Herman et al., Citation2011; Knecht & Hargrave, Citation2002; Kruzich et al., Citation2003; Lyman & Campbell, Citation1996; Sharrock et al., Citation2013) also negatively influence parental participation in JJIs.

Our results point out the importance that parents attach to being able to visit their adolescent during detention. This also implies the importance for JJIs to facilitate visits and by extension participation. Particularly in family-centered care programs, this is a basic requirement.

Although JJIs are faced with some static factors that are difficult to influence (e.g., distance from home to the JJI), the dynamic factors offer an opportunity to improve parental participation rates (e.g., staffs’ behavior towards parents). Our results offer suggestions to policy makers and JJI staff members to better involve parents in JJI activities and procedures. Some of these suggestions are in line with outcomes of research in other residential settings. Based on parents’ answers in our study, the suggestions include the following policy recommendations. (1) Offer transportation aid (Nickerson, Brooks, Colby, Rickert, & Salamone, Citation2006) in the form of shuttle bus rides, carpool opportunities, and good connections to public transportation. (2) Offer childcare, or help parents activating their support network to find babysitters (Garfinkel, Citation2010). One other policy suggestion for JJIs follows from a previous study showing that high staff turnover negatively influences parental participation in residential treatment centers (Degner et al., Citation2007). Parents in our study confirmed the importance of continuity of care. Therefore, JJIs are suggested (3) to prevent staff turnover and are invited to reconsider the system where adolescents are transferred between groups and continually switch mentors and psychologists as their stays continue.

For JJI staff, the results of our study offer the following practical recommendations: (4) Notify parents early about JJI activities (Demmitt & Joanning, Citation1998) and (5) be flexible in organizing activities for parents (Sharrock et al., Citation2013). According to Baker and Blacher (Citation2002), one of the biggest disadvantages of a child’s out-of-home placement is losing contact and sharing with the family. In line with that previous finding, parents in our study commonly stated that missing their adolescent was one of the major reasons for visiting the JJI for activities. Thus, the next recommendation (6) is that JJI staff use this knowledge by explicitly offering activities to parents that include spending time with their adolescent.

Our study shows that parents’ sentiments concerning their adolescent’s detention could influence their level of participation. Contrary to previous literature (Baker & Blacher, Citation2002; Baker et al., Citation1993; Kruzich et al., Citation2003; Schwartz & Tsumi, Citation2003), adolescents’ psychopathology caused some parents in our sample to be more motivated to collaborate with JJI staff and to participate in activities, as they were worried about their sons. Additionally, parents in our sample described that having to visit a JJI because their adolescent is detained was confrontational and intense. A JJI in the Netherlands does not have a welcoming atmosphere due to the fence around the building, bars behind the windows, metal detector gates for visitors, doors that lock automatically, and staff wearing mobile alarm systems. Having an adolescent detained in a JJI elicited a variety of emotions among parents, including anger, shame, disappointment, and fear. Anger has been previously been identified as a hindering factor for parental participation (Sharrock et al., Citation2013). Some parents in our study first had to overcome these negative emotions before they were able to enter the facility.

Acknowledging that detention of their adolescent could evoke negative emotions among parents might result in parents feeling better understood by JJI staff. This could help build a working alliance, through which it might be easier for JJI staff to motivate parents to participate. For example, being aware of possible feelings of mistrust or the negative image parents have about the JJIs might stimulate staff to reassure parents and to invite them to see and experience their adolescent’s living environment.

Beyond the emotional effects on parents due to their adolescent’s detention, our study indicates that cognitions influenced parental participation as well. Upon their adolescents being detained, parents seemed to apply cognitive strategies that enhanced their motivation for participation. One strategy was viewing placement in a JJI as an opportunity for their adolescent, i.e., for finally receiving the right treatment. A second strategy was that parents separated behavior from character when thinking of their adolescent. Most parents attributed positive qualities to their sons and half of them were unpleasantly surprised by the detention. Previous research has shown that that parents who had a good relationship with their child prior to detention, were more engaged with their child and were shocked about detention (Church Ii, MacNeil, Martin, & Nelson-Gardell, Citation2009). A third cognitive strategy was that parents externalized the cause of the alleged crime (e.g., negative influence from peers). This calls for providing psycho-education to parents about the multidimensional risk factors for criminal behavior, including the risks during puberty and how to protect the adolescent against those risks.

Besides the many useful suggestions from parents to improve practice resulting from our study, it also had some limitations. The first limitation concerned the possible sampling bias. We were only able to interview the parents who were willing to participate in our study. This might have influenced our findings, as it is generally possible that less motivated parents also were unwilling to participate in the study. These parents might experience other obstructing or facilitating factors for participation. Another limitation concerned the fact that the two JJIs in our study only housed boys. Therefore, our results cannot be generalized to parents who have a detained daughter. We suggest future research to study whether these parents consider similar factors which influence their participation. A third possible limitation concerned the interviews with two parents together. Usually, interviews in qualitative research are conducted with only one parent. However, some parents strongly preferred to be interviewed together. Conversations with two parents might be a reflection of the clinical reality JJI staff encounter when collaborating with parents. Although the interviewers strived to receive answers from both parents equally, the dynamic of the interpersonal relationship between the parents might have influenced their answers. For example, in an interview where one of the parents was the primary caretaker of the adolescent but where the other parent was still involved in his life and upbringing, the first parent tended to be more dominant in answering the questions of the interviewer. Therefore, the interviewer specifically asked about the opinion of the second parent on several occasions during the interview.

A similar limitation applied to the use of family members as interpreters as was the case in two interviews. Since these family members were not professional interpreters and, on some occasions, they were closely involved with parenting the adolescent, there was risk of coloring the answers of parents by the interpreters. However, having a familiar face translating the interviewer’s questions into parents’ native language, and vice versa, actually stimulated parents’ motivation to participate in the study.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our study yields some refreshing implications for practice. Besides the aforementioned recommendations, our results suggest that JJI staff should invest in motivating youths for their parents’ participation in activities. Some parents described that their adolescent did not want them to participate out of embarrassment or out of protective intentions, and how this negatively influenced parents’ motivation to come to the JJI. Hence, we suggest future research to examine what detained youths consider to be the best way to involve their parents and which factors might cause the adolescents to either embrace their parents’ participation or to object to it.

On a final note, not all facilitating or hindering factors play a role for each parent to the same extent. Realizing that the factors potentially have cumulative effects (Kruzich et al., Citation2003), we suggest JJI staff to inventory these factors in individual cases as soon as possible when an adolescent enters detention. Consequently, JJI staff are continuously faced with the challenge of individualizing their strategies to motivate parents for involvement to the specific parent at hand. Keeping an open and respectful conversation with parents about possible hindering factors might contribute to finding solutions to overcome them. Overcoming obstacles for participation could improve parents’ involvement during their adolescent’s detention, which in turn has the potential for optimizing care.

Conclusion

Our study showed that parental participation during adolescent detention in a JJI is influenced by a variety of facilitating and obstructing factors that could be categorized into the following themes: (1) practical factors, (2) parent-related emotional and mental factors, and (3) factors concerning issues of the parent-adolescent relationship. To improve parental participation during their adolescent’s detention, JJI staff could meet with the parents early in the process of detention to assess which factors might influence their participation. Our results indicate that it is important to acknowledge negative emotions among parents potentially evoked by their adolescent’s detention, and JJI staff could offer parents reassurance by inviting them for a tour throughout the facility. Tailored solutions might help motivate parents for participation. Offering flexible opportunities to spend time with their adolescent might increase parent’s motivation. Additionally, the results of our study suggest JJIs to offer transportation aid, support in arranging childcare for other children, and reconsider the system where adolescents are transferred between groups and continually switch mentors and psychologists as their stays continue.

Notes

1 When describing the outcomes we use quantifiers to refer to the number of respondents involved. As a rule of thumb, these quantifiers could be interpreted as follows: “A few” = 2; “Some” = 3-4; “Almost/About half” = 5 or 6; “Half” = 7; “More than half” = 8; “Most” = 9 – 13; “All” = 14.

References

- Baker, B. L., & Blacher, J. (2002). For better or worse? Impact of residential placement on families. Mental Retardation, 40(1), 1–13.

- Baker, B. L., Blacher, J., & Pfeiffer, S. (1993). Family involvement in residential treatment of children with psychiatric disorder and mental retardation. Psychiatric Services, 44(6), 561–566.

- Baker, B. L., Blacher, J., & Pfeiffer, S. I. (1996). Family involvement in residential treatment. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 101(1), 1–14.

- Boeije, H. (2010). Analysis in Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

- Boeije, H. (2012). Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek. Denken en doen. Den Haag: Boom Lemma uitgevers.

- Burke, J. D., Mulvey, E. P., Schubert, C. A., & Garbin, S. R. (2014). The challenge and opportunity of parental involvement in juvenile justice services. Children and Youth Service Review, 39, 39–47.

- Church Ii, W. T., MacNeil, G., Martin, S. S., & Nelson-Gardell, D. (2009). What do you mean my child is in custody? A qualitative study of parental response to the detention of their child. Journal of Family Social Work, 12(1), 9–24. doi:10.1080/10522150802654286

- De Boer, C., Cameron, G., & Frensch, K. (2007). Siege and response: Reception and benefits of residential children's mental health services for parents and siblings. Child and Youth Care Forum, 36(1), 11–24.

- Degner, J., Henriksen, A., & Oscarsson, L. (2007). Youths in coercive residential care: Perception of parents and social network involvement in treatment programs. Therapeutic Communities, 28(4), 413–429.

- Demmitt, A. D., & Joanning, H. (1998). A parent-based description of residential treatment. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 9(1), 47–66. doi:10.1300/J085V09N01_04

- Flick, U. (2018). The Sage handbook of qualitative data collection. London: Sage Publications Ltd. doi:10.4135/9781526416070

- Garfinkel, L. (2010). Improving family involvement for juvenile offenders with emotional/behavioral disorders and related disabilities. Behavioral Disorders, 36(1), 52–60.

- Hendriksen-Favier, A., Place, C., & Van Wezep, M. (2010). Procesevaluatie van YOUTURN: introomprogramma en stabilisatie- en motivatieperiode. Fasen 1 en 2 van de basismethodiek in justitiële jeugdinrichtingen. Utrecht: Trimbos-instituut.

- Herman, K. C., Borden, L. A., Hsu, C., Schultz, T. R., Strawsine Carney, M., Brooks, C. M., & Reinke, W. M. (2011). Enhancing family engagement in interventions for mental health problems in youth. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 28(2), 102–119. doi:10.1080/0886571X.2011.569434

- Janssens, J. M. A. M. (2016). Transitie en transformatie in de jeugdzorg. In S. Begeer, L. Boendemaker, H. Colpin, M. Geeraerts, H. Koomen, N. Lambregts-Rommelse, K. Van Leeuwen, R. Lindauer, G. Overbeek, P. Prinzie, G. Smid, B. Soenens, & G. Stevens (Eds.), Kind en adolescent. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum, onderdeel van Springer Media BV.

- Knecht, K. M. S., & Hargrave, M. C. (2002). Familyworks: Integrating family in residential treatment. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 20(2), 25–35. doi:10.1300/J007v20n02_03

- Kruzich, J. M., Jivanjee, P., Robinson, A., & Friesen, B. J. (2003). Family caregivers' perceptions of barriers to and supports of participation in their children's out-of-home treatment. Psychiatric Services, 54(11), 1513–1518.

- Latimer, J. (2001). A meta-analytic examination of youth delinquency, family treatment, and recidivism. Canadian Journal of Criminology, 43, 237–253.

- Lucassen, P. L. B. J., & Olde Hartman, T. C. (2007). Kwalitatief onderzoek. Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

- Lyman, R. D., & Campbell, N. R. (1996). Treating children and adolescents in residential and inpatient settings Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- McNown Johnson, M. (1999). Multiple dimensions of family-centered practice in residential group care: Implications regarding the roles of stakeholders. Child & Youth Care Forum, 28(2), 123–141.

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Monahan, K. C., Goldweber, A., & Cauffman, E. (2011). The effects of visitation on incarcerated juvenile offenders: How contact with the outside impacts adjustment on the inside. Law and Human Behavior, 35(2), 143–151.

- Mos, K., Breuk, R., Simons, I., & Rigter, H. (2014). Gezinsgericht werken in Justitiële Jeugdinrichtingen op afdelingen voor kort verblijf. Zutphen: Academische Werkplaats Forensische Zorg voor Jeugd.

- Nickerson, A. B., Brooks, J. L., Colby, S. A., Rickert, J. M., & Salamone, F. J. (2006). Family involvement in residential treatment: Staff, parent, and adolescent perspectives. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15(6), 681–964.

- Peters, V., & Wester, F. (2007). How qualitative data analysis software may support the qualitative analysis process. Quality & Quantity, 41(5), 635–659.

- Robinson, A. D., Kruzich, J. M., Friesen, B. J., Jivanjee, P., & Pullman, M. D. (2005). Preserving family bonds: Examining parent perspectives in the light of practice standards for out-of-home treatment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75(4), 632–643. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.75.4.632

- Schwartz, C., & Tsumi, A. (2003). Parental involvement in the residential care of persons with intellectual disability: The impact of parents' and residents' characteristics and the process of relocation. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 16(4), 285–293. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3148.2003.00162.x

- Sectordirectie Justitiële Jeugdinrichtingen. (2011). Visie op Ouderparticipatie in Justitiële Jeugdinrichtingen. Den Haag: Dienst Justitiële Inrichtingen, Ministerie van Veiligheid en Justitie.

- Sharrock, P., Dollard, N., Armstrong, M., & Rohrer, L. (2013). Provider perspectives on involving families in children’s residential psychiatric care. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 30(1), 40–54.

- Simons, I., Mulder, E., Rigter, H., Breuk, R., Van der Vaart, W., & Vermeiren, R. (2016). Family-centered care in juvenile justice institutions: A mixed methods study protocol. JMIR Research Protocols, 5(3), e177. doi:10.2196/resprot.5938

- Simons, I., Mulder, E., Breuk, R., Mos, K., Rigter, H., Van Domburgh, L., & Vermeiren, R. (2017). A program of family-centered care for adolescents in short-term stay groups of juvenile justice institutions. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 11(61). doi:10.1186/s13034-017-0203-2

- Simons, I., Mulder, E., Breuk, R., Rigter, H., Van Domburgh, L., & Vermeiren, R. (2018). Determinants of parental participation in family-centered care in juvenile justice institutions. Child & Family Social Work, 1–10. doi:10.1111/cfs.12581

- Silverman, D. (2010). Doing qualitative research. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Stuurgroep YOUTURN. (2009). YOUTURN Basishandleiding. Den Haag: Dienst Justitiële Inrichtingen.

- Vlaardingerbroek, P. (2011). De justitiële jeugdinrichting en de ouders. Den Haag: Boom Lemma uitgevers.

- Woolfenden, S. R., Williams, K., & Peat, J. K. (2002). Family and parenting interventions for conduct disorder and delinquency: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 86(4), 251–256.