Abstract

In order to gain insight in empathic deficits in juveniles with severe antisocial problems and psychopathic traits, self-reported psychopathic traits and trait empathy were assessed in 416 detained male juveniles. State empathy was assessed by self-reported empathic and autonomic nervous system (ANS) responses to sad film clips. Psychopathic traits were significantly negatively correlated with empathy, although not with ANS responses. Individuals reporting no empathy showed significantly less heart rate withdrawal compared to individuals reporting higher empathy. This implies that physiological responses may be helpful in identifying juveniles with severely impaired empathic functioning, even in a severely antisocial sample.

Introduction

Antisocial and criminal behavior of children and juveniles is a considerable problem within many Western countries, resulting in both material and immaterial damage to society and individual victims (Lodewijks & van Domburgh, Citation2012). The offenders themselves are also negatively affected if they do not receive appropriate and timely assistance (Lodewijks & van Domburgh, Citation2012). Therefore, it is important to gain insight into the underlying mechanisms of antisocial and delinquent behavior. One of the important characteristics that have been related to antisocial and delinquent behavior is psychopathic traits (Flight & Forth, Citation2007; Vaughn, Howard, & DeLisi, Citation2008). Psychopathic traits consist of three dimensions: the Grandiose-manipulative (interpersonal) dimension, the Daring-impulsive (behavioral) dimension, and the Callous-unemotional (affective) dimension (Dong, Wu, & Waldman, Citation2014; Salekin & Lynam, Citation2010). Adolescents displaying high psychopathic traits, and specifically those displaying callous-unemotional (CU-) traits, show deficits in empathy (Jones, Happé, Gilbert, Burnett, & Viding, Citation2010).

Juveniles displaying psychopathic traits usually score low on trait empathy (e.g., Jones et al., Citation2010). However, in severely antisocial samples, self-reports of trait empathy may have important limitations, which hampers adequate assessment of empathic functioning in this group. First, self-report questionnaires are thought to be flawed by socially desirable answers. This could be especially prevalent in individuals with high psychopathic traits, who are known to be more manipulative (Andershed, Kerr, Stattin, & Levander, Citation2002). In this respect, some authors even concluded that it seems unlikely that self-report is a bona fide barometer of whether affect has been evoked (Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous & Warden, Citation2008). Second, it could be difficult for juveniles to judge one’s own emotions and cognitions and put these into words, especially in the case of aggressive tendencies (Quiggle, Garber, Panak, & Dodge, Citation1992). Moreover, by focusing on trait empathy uniquely, we risk different kinds of bias, such as recall bias of actual situations. Finally, it is highly likely that different triggers elicit different empathic responses, making a combined judgment for “overall empathy” quite demanding. Consequently, trait measures may not always give an accurate assessment of a person’s empathic abilities.

Measuring state empathy may increase the accuracy of assessing empathic functioning. By making use of a specific emotional trigger, it is possible to assess the empathic response during actual emotion eliciting situations. To bring this about, several studies have used a film clip paradigm (Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous & Warden, Citation2008; Bos, Jentgens, Beckers, & Kindt, Citation2013; de Wied, Goudena, & Matthys, Citation2005; de Wied, van Boxtel, Matthys, & Meeus, Citation2012; de Wied, van Boxtel, Posthumus, Goudena, & Matthys, Citation2009; Fernández et al., Citation2012; Kreibig, Wilhelm, Roth, & Gross, Citation2007; Pfabigan et al., Citation2015). Film clips were shown to be able to elicit specific emotions, as demonstrated by self-reported state empathic responses (Fernández et al., Citation2012; Gross & Levenson, Citation1995; Hewig et al., Citation2005). However, as is the case with trait empathy, assessment of state empathic functioning solely through self-report may be hampered by social desirability or a limited ability of self-insight. Therefore, several researchers in the field of empathy advise to add more objective measures of empathic response to the use of self-report, such as physiological measures (e.g., Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous & Warden, Citation2008; de Wied et al., Citation2012).

Seeing another in an emotional state, especially distress, generates corresponding responses of the autonomic nervous system (ANS). Current findings in typically developing individuals show that exposure to film clips eliciting sadness is generally associated with heart rate (HR) deceleration, further referred to as withdrawal response (Eisenberg & Fabes, Citation1990; Kreibig et al., Citation2007). In clinical samples of children and adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders (DBD) and/or CU-traits, several studies showed less HR withdrawal in response to an emotional film clip compared to individuals without CU-traits and controls (Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous & Warden, Citation2008; de Wied et al., Citation2009, Citation2012). In order to better disentangle what causes physiological differences, Marsh, Beauchaine, and Williams (Citation2008) advise to include independent indicators of sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) activity rather than using a sole measure, such as HR, which is influenced concurrently by both autonomic branches (Berntson, Cacioppo, Quigley, & Fabro, Citation1994; Cacioppo, Uchino, & Berntson, Citation1994).

Activation of the SNS results in an increased HR, and promotes activation such as flight and fight responses. The PNS on the other hand is activated during resting periods and decreases HR. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA; a measure of PNS activity) is considered a biomarker for emotion regulation (Beauchaine, Citation2015). Problems with emotion regulation and the severity of externalizing symptoms have been associated with lower responses in the PNS (Blandon, Calkins, Keane, & O'Brien, Citation2008; Calkins, Graziano, & Keane, Citation2007; Fortunato, Gatzke-Kopp, & Ram, Citation2013; Willemen, Schuengel, & Koot, Citation2009). A greater decrease in RSA, a sign of more adaptive parasympathetic activity, predicts more adaptive emotion regulation (Gentzler, Santucci, Kovacs, & Fox, Citation2009). This could make RSA an interesting measure when it comes to empathic responding. Results regarding PNS responses to empathy elicitation in clinical subjects are however rather inconsistent, involving both increases and decreases in PNS responses, or no differences between DBD groups and controls (Beauchaine, Gatzke-Kopp, & Mead, Citation2007; Marsh et al., Citation2008; Pang & Beauchaine, Citation2013; Zahn-Waxler, Cole, Welsh, & Fox, Citation1995). Only Marsh et al. (Citation2008) studied SNS reactivity in relation to empathy and found no differences between a DBD group and controls.

Notably, self-reported and physiological responses to empathy elicitation do not necessarily point in the same direction (i.e., they can be concordant or discordant). A study in adult male offenders showed that, while participants showed a diminished withdrawal response on physiological measures during a task, only individuals with higher scores of psychopathic traits gave seemingly normal self-reported empathic responses (Pfabigan et al., Citation2015). The authors argue that psychopaths could appear similarly empathic as controls due to these self-reported responses, resulting in successful misleading and manipulation of others. On the other hand, this could also indicate diminished interoceptive awareness (Gao, Raine, & Schug, Citation2012; Nentjes, Meijer, Bernstein, Arntz, & Medendorp, Citation2013). In children and adolescents, conduct disordered individuals with and without CU-traits did not differ on self-reported empathy, while the group with CU-traits demonstrated diminished withdrawal responses, thus also showing discordant responses (Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous & Warden, Citation2008). However, studies with concordant findings (i.e., self-report and physiological responses seem to point in the same direction) have also been reported (de Wied et al., Citation2009, Citation2012). As differences between participants only seemed to become apparent when ANS measures and levels of psychopathic traits or CU-traits were taken into account, the addition of these measures could be quite important when assessing empathic abilities in antisocial samples.

To our knowledge, no empathy studies in detained adolescents and young adults have been performed using a film clip paradigm, let alone assessing concordance or discordance of self-reported and physiological empathic responses. Therefore, with the current study it was aimed to gain insight into state empathic functioning by using both self-reported and physiological responses in reaction to emotion eliciting film clips in detained juveniles with various levels of psychopathic traits. Individuals with psychopathic traits in general seem to be particularly insensitive for signals of sadness and fear in others (Blair, Citation1999, Citation2007; Blair, Budhani, Colledge, & Scott, Citation2005; Blair, Colledge, Murray, & Mitchell, Citation2001; Blair & Coles, Citation2000; Sommer et al., Citation2006; Stevens, Charman, & Blair, Citation2001). Researchers have argued that measuring empathic reactions to elicitation of the emotion sadness may be more relevant to empathic responding than other emotions in individuals with (high) CU-traits (de Wied et al., Citation2012). Hence, in this study the focus was on empathic responses to the emotion sadness.

First, in order to check whether previous findings regarding the relationship of diminished empathy and psychopathic traits can indeed be corroborated in our sample, questionnaires on psychopathic traits and trait empathy will be correlated. It is expected that individuals with higher scores of psychopathic traits—and especially CU-traits—will report less trait empathy. Second, questionnaires on psychopathic traits and self-reported state empathy in response to emotion eliciting film clips will be correlated. Again, it is expected that higher scores of psychopathic traits and CU-traits will be associated with less reported state empathy. Furthermore, it is hypothesized that individuals with higher scores of psychopathic traits will demonstrate less HR withdrawal (reflected in less HR deceleration) when watching empathy eliciting film clips (conform Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous & Warden, Citation2008; de Wied et al., Citation2012; de Wied et al., Citation2009). Although the varying results with regard to PNS and SNS response to empathy elicitation in the literature (Beauchaine et al., Citation2007; Marsh et al., Citation2008; Pang & Beauchaine, Citation2013; Zahn-Waxler et al., Citation1995) do not warrant a clear hypothesis regarding the direction of this association, it was expected that differences would be found mostly at the level of PNS activity due to its link to emotion regulation (Beauchaine, Citation2015). However, as the balance between both branches determines ANS activity it is reasonable to include a measure of SNS activity, especially since independent activation or coactivation of the two branches has been found (Berntson, Norman, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, Citation2008; Berntson & Cacioppo, Citation2007). Finally, to examine whether self-reported responses correspond with physiological responses, we evaluated concordance or discordance of state empathic self-reported and physiological responding to the empathy eliciting film clips.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from six different residential youth care institutions (five juvenile justice institutions and one residential care institution) in the Netherlands, to which they were referred because of severe behavioral problems or serious offenses. Admission to a closed facility was compulsory for all juveniles, either by penal law (juvenile justice institutions) or civil law (residential care institution). All participants (and when under the age of 18 also parents/caregivers) signed an informed consent document. Exclusion criteria were inability to sign informed consent, insufficient command of the Dutch language, cardiac problems that would interfere with the measurement of heart rate (HR) or heart rate variability (HRV) (e.g., arrhythmia and asthma), and inability to understand instructions and questionnaires, which was brought to our attention by institution staff. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee at the University of Amsterdam, and performed in accordance with the ethical standards described in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Data were collected between February 2014 and April 2016, in collaboration with the department of Developmental Psychology of the University of Amsterdam.

Of the 799 approached juveniles, 354 did not participate in the study. Of this group, the majority refused participation (57.6%), it was impossible to schedule an appointment (31.1%), parents/caregivers did not or could not provide informed consent (6.5%), command of the Dutch language was insufficient (1.7%), or participation was discouraged by institution staff (0.8%). For 2.3% the reason of refusal was unclear. Due to the small number of participating girls (N = 29), and possible sex differences in empathy, girls were excluded from analyses for the current paper (see e.g., Broidy, Cauffman, Espelage, Mazerolle, & Piquero, Citation2003). Participants included a total of 416 detained male juveniles, ranging from 14–24 years of age (mean age: 18.58, SD 1.70). With regard to socioeconomic status (SES), 24.8% of the sample had a low, 62.7% a middle, and 3.6% a high SES. For 8.9% of the participants SES could not be determined. Concerning level of education, the majority of participants (66.1%) completed vocational education or higher secondary education, 31.7% competed only primary school or lower secondary education, 1% received a bachelor or master degree, and 1% completed no education. For 0.2% level of education could not be determined. Participants were mainly of non-western descent, defined as one or both parents being born in a non-western country (67.3%). Other participants were of Dutch (26.2%) and other western descent (3.4%). For 3.1% of the participants no information on birth place of one or both of the parents was available.

Procedure

Juveniles were assessed individually in a test room inside the institution. Experimenters were trained with regard to electrode placement and procedures of the tasks, and remained in the room for the entire period of testing. They followed a detailed written protocol including verbal instructions. Electrodes were placed on the juveniles’ chest and back, and then connected to the VU-AMS device. Participants were instructed to sit still, and asked not to touch the electrodes. During the next 10 min, participants were asked to complete questionnaires on the computer to allow them to acclimate to the setting. During this period ANS parameters were measured as a natural baseline (acclimation period). After that, HR, HRV/RSA, and pre-ejection period (PEP) were measured while juveniles completed tasks on the computer. These tasks consisted of a baseline measure during a 5-min resting protocol (conform Scarpa, Haden, & Tanaka, Citation2010), and the viewing of two film clips, interspersed with 1-min baselines. In case of having problems with sitting still, a gentle reminder was provided. After completion of the ANS measurements, participants were disconnected from the VU-AMS device, and were asked whether they felt an altered/depressed mood, in which case mood elevation could be used if necessary. Then they continued with questionnaires and tasks on the computer for the remainder of the session. The tasks were part of a more extended test session which will not be described here. The total session lasted approximately 90 min. The participants were compensated for their time with a €5 stipend.

Methods

Psychopathic traits

Trait empathy; Index of Empathy for Children and Adolescents (IECA)

The Index of Empathy for Children and Adolescents (IECA; Bryant, Citation1982) is a 22-item measure of emotional responsiveness of children and adolescents. Reported internal consistency coefficients range from 0.68–0.79 (4th and 7th graders, respectively; Bryant, Citation1982). Moderate to high correlations with other empathy measures were found (r = 0.42–0.77, seventh grade), demonstrating convergent validity. Seven items identified and translated into Dutch by de Wied et al. (Citation2007) as assessing empathic sadness were used in the current study to measure trait empathy. The empathic sadness factor showed good reliability in children (3rd and 8th graders; de Wied et al., Citation2007). Items assess affective empathy for children the age of six and over, e.g., “Seeing a boy who is crying makes me feel like crying.” Each item is scored on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Possible scores range from 7–28. The accumulated item score is a total score of affective empathy, with higher IECA scores indicating higher empathy related to sadness. In the current study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient was 0.83.

Emotion evocation Task

This task was conducted using two sadness film clips that have previously been shown to evoke empathic responses and differ in emotional intensity:

The first film clip by de Wied et al. (Citation2012) was assembled from a Dutch documentary film. The protagonist is a boy (Mohammed) who plays soccer in the Ajax youth team. When the trainer tells him that he failed at selection, Mohammed starts to cry. The entire clip was 148 sec. The target episode (37 sec) consisted of the part where the emotion was most intensely displayed by the story character (conform de Wied et al., Citation2012). Several studies revealed that the film clip indeed evokes the targeted emotion sadness and responses of the ANS (de Wied et al., Citation2009, Citation2012). The second clip was drawn from the film “The Champ” (Lovell & Zeffirelli, Citation1979). Selection of this film was based on criteria recommended by Rottenberg, Ray, and Gross (Citation2007), and the clip was edited following detailed frame editing instructions (Appendix; Rottenberg et al., Citation2007). This clip is used in different studies and appears to evoke the highest degree of sadness in subjects in comparison with other emotional clips (Gross & Levenson, Citation1995), and results in ANS reactivity (Marsh et al., Citation2008). In this clip “The Champ” sustains injuries after a beating in the ring. He dies as a result of the injuries, while his son witnesses this. The entire clip was 95 sec and the target episode were emotion was most intense was 43 sec.

Each film clip was preceded by 1 min of an aquatic video (Coral Sea Dreaming, Small World Music, Inc.) to assess baseline ANS. Piferi, Kline, Younger, and Lawler (Citation2000) have shown that watching this relaxing video is more effective in decreasing cardiovascular activity than simply sitting quietly, and better able to achieve recovery to resting state following a task. Subsequently, a text on the screen was displayed, which served as an introduction to the emotional film clips, and then the emotional film clips were presented. The order of the film clips was counterbalanced to ensure that any between-condition differences could only be attributed to differences in the presented film clip. The total emotion evocation task lasted 7 min. The sound of the film clips was presented binaurally through headphones (Sennheiser HD201). For stimuli presentation and self-reports following the film clips, E-prime version 2.0 was used on a DELL Latitude E5550 type laptop.

State empathy

State empathy was measured right after watching two film clips. After each clip, the participants were asked how the boy felt during the film clip (to measure cognitive empathy), and were then asked the same question regarding their own experienced emotions (to measure affective empathy). Participants could indicate this by rating four emotions “happy,” “angry,” “afraid,” and “sad” on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much/a lot). This resulted in 8 scores for each film clip. Participants were then asked if they had seen the film clip before (yes/no). Only responses for the emotion sadness were used. A response was labeled as an empathic response (1/empathic) if the participant both reported correct emotion recognition as well as a correct affective response for sadness (conform de Wied et al., Citation2012), meaning a score of 3 or higher for the emotion sadness. In case of incorrect emotion recognition, or an incorrect affective response, the response was labeled as a non-empathic response (0/non-empathic), as no matching of emotions took place. Both the continuous and dichotomized measures were used in the analyses.

Physiological measures

Activity of the ANS was measured using the VU-Ambulatory Monitoring System (AMS; Klaver, De Geus, & De Vries, 1994). Data were analyzed with VU-AMS software (VU-DAMS version 3.9) and data analysis support was offered by the VU-AMS department of VU University. Three electrodes (H985SG micropore ECG electrodes) were placed on the chest to measure participant’s heart rate during the task (electrocardiogram (ECG), at 1000 Hz). Four additional electrodes were placed on chest and back for assessment of thoracic impedance cardiography (ICG, at 250 Hz). Placement of the electrodes was done according to the VU-AMS manual (http://www.vu-ams.nl/support/instruction-manual/). Aside from heart rate, this resulted in measures for sympathetic (PEP) and parasympathetic (RSA) branches of the ANS.

Data preparation

R-peak time series (ECG signal), Q-onset (ensemble averaged ECG), B-point, dZ/dt-min peaks, and X-points (ensemble averaged ICG) were detected by automated detection algorithms in the software. Heart rate (in beats per minute) was derived from the R-peak time series. Vagal rebound was assessed by HRV in the respiratory frequency range, extracted from the ECG and the respiratory signal (de Geus, Willemsen, Klaver, & van Doornen, Citation1995). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) is defined as the longest heart period during expiration minus the shortest heart period during inspiration. RSA was computed on a breath-to-breath basis. When no difference in shortest and longest beats could be detected, RSA was set to be zero for that breath. RSA (reactivity) values were set as missing whenever >50% of respiration data was identified as irregular. In the assessment of RSA it is advised to correct for the effect of respiration rate (see, e.g., Grossman & Taylor, Citation2007) and smoking (Prätzlich et al., Citation2018). RSA was transformed logarithmically (Lg RSA) due to a skewed distribution which became closer to a normal distribution after transformation. Sympathetic nervous system activity (PEP) was derived from combined ICG and ECG recording. PEP is defined as the time period between the onset of the left ventricular depolarization (Q-wave onset in ECG) and the opening of the aortic valve (B-point in ICG). In the assessment of physiological measures body movement was not controlled for, however all data were inspected manually for abnormalities and artifacts removed from data analysis. Reactivity to the emotional film clips was calculated by creating change scores in HR, RSA, and PEP from baseline to film clip (conform de Wied et al., Citation2012). Baseline averages (during 1-min baselines preceding the film clip) were subtracted from task averages (target scenes of film clips), negative values were associated with withdrawal (deceleration).

For questionnaires, frequency analyses showed a couple of items had missing data (% of total items that had 1 or more non-systematically missing values). For items with non-systematically missing data values were imputed via multiple imputations using the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method (Schafer, Citation1997). Each item with missing values was imputed 35 times, after which the median value of all 35 estimates per item was entered. Subsequently, the normal distribution of each variable was examined by visually inspecting histograms and Q–Q plots.

Statistical analyses

To test whether juveniles with higher scores of psychopathic traits report less trait empathy, Pearsons’ r correlations were estimated between trait empathy (IECA) and psychopathic traits (YPI-s).

To confirm whether our emotion evocation task indeed elicited empathic and physiological responses, it was checked whether participants showed emotion recognition as well as an affective response for the portrayed emotion sadness. As for physiological response patterns, one-sample t-tests for HR, RSA and PEP measures were performed with the change scores, to assess whether ANS change scores for both film clips differed significantly from zero.

To test for relations between psychopathic traits, self-reported trait empathy and self-reported empathic and physiological response, Pearson’s r correlations between trait empathy (IECA), state empathy (self-reported affective empathy after watching film clips), and HR, RSA, and PEP change scores were calculated.

Subsequently, to specifically compare self-reported empathic and non-empathic responders to the film clips, the sample was divided into an empathic group and a non-empathic group based on self-reported empathic responses to the film clips. This was undertaken conform methods of de Wied et al. (Citation2012), since the variation in self-reported state empathic responses was low (see Response to emotional film clips in the Results section). Due to the distribution of this measure, dichotomization seemed most ecologically valid. Participants were counted as empathic when both correct emotion recognition of the emotion sadness, as well as a correct affective response, were reported (empathic group). Participants were seen as non-empathic when emotion recognition was intact, but no effective response was reported for the emotion sadness (non-empathic group). T-tests were performed to compare the empathic group and non-empathic group on the total amount of psychopathic traits (YPI-s total score). The same analyses as for overall psychopathic traits were conducted with the affective dimension of the YPI-s. Finally, t-tests were performed to compare the non-empathic and empathic groups on their ANS change scores.

Variables related to general psychopathology or cardiac functioning were identified as potential covariates: age, ethnicity, smoking (mean cigarettes per day), BMI, and respiration rate. Variables that correlated significantly with the dependent variables were added as covariates to regression analyses. Age correlated significantly with the HR change score during film clip Champ (r = 0.11, p = <0.05). Respiration rate correlated significantly with RSA change score for both film clips (r = −0.16, p < 0.01 Mohammed; r = −0.20, p < 0.001 Champ). Smoking was related to PEP change score for film clip Champ (r = 0.11, p < 0.05). No significant effects of the covariates emerged in regression analyses, therefore these results are not reported.

Results

Psychopathic traits and trait empathic responses

displays the mean scores for the psychopathic traits and the trait empathy scores for the total sample. Level of psychopathic traits was negatively correlated with trait empathy (IECA), for the YPI-s total score, as well as the affective dimension and the interpersonal dimension of the YPI-s (see ), indicating that higher scores of psychopathic traits were related to lower trait empathy.

Table 1. Overview of correlations, means, and standard deviations.

Response to emotional film clips

Almost all participants (97.4% Champ; 96.6% Mohammed) correctly identified the targeted emotion sadness in the film clips (indicated by a score of 3 or higher on the emotion sadness). Correct affective responses for state empathy (indicated by a score of 3 or higher on the emotion sadness) were 39.2% for Champ and 21.7% for Mohammed. The average scores of affective empathy were 2.25 for Champ (SD = 1.27) and 1.75 (SD = 1.08) for Mohammed (see ).

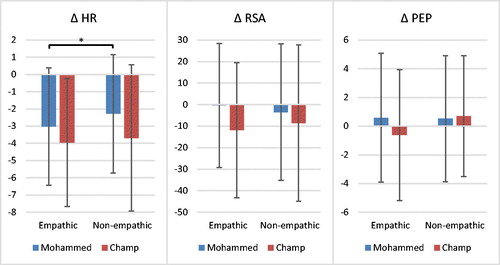

The descriptives for the ANS change scores are displayed in , descriptives for ANS data during the emotion evocation task are displayed in Table A in the Addendum, presented as Mean scores (M) and Standard Deviations (SD). To ascertain whether our stimulus material elicited classic physiological response patterns for ANS measures, one-sample t-tests were performed to assess whether ANS change scores (HR, RSA, PEP) for both film clips differed significantly from zero. For both film clips, participants showed a significant decrease in HR from baseline to film clip (ΔHR Mohammed: t = −15.28, p < 0.001; ΔHR Champ: t = −19.89, p < 0.001). Participants showed a decrease in RSA from baseline to film clip, which was only significant for film clip Champ (ΔRSA Mohammed: t = −1.49, p = 0.138; ΔRSA Champ: t = −6.42, p < 0.001). Finally, participants showed an increase in PEP from baseline to both film clips (ΔPEP Mohammed: t = 2.46, p < 0.05; ΔPEP Champ: t = 2.97, p < 0.01).

Psychopathic traits and state empathic and physiological responses

Trait empathy (IECA) was significantly correlated with self-reported state empathic responses (obtained after viewing film clips), for both film clip Mohammed and Champ, suggesting that lower scores on the IECA were associated with reports of less sadness in response to watching a sadness film clip (see ). For both the YPI-s total score as well as the affective dimension and the behavioral dimension of the YPI-s, a negative relation with empathic self-report (state) was observed, indicating that participants with higher scores of psychopathic traits reported less sadness after watching an emotional film clip (see ).

With regard to HR reactivity, no significant correlations were observed between change scores on both film clips and psychopathic traits (YPI-s total score and affective dimension), or trait empathy (IECA). For state empathy, only for the film clip Mohammed, the level of self-reported empathic sadness was correlated with the HR change score (see ), indicating that individuals with lower self-reported empathic sadness showed less HR withdrawal in response to film clip Mohammed. This pattern was not significant for film clip Champ. No significant correlations were observed between PNS and SNS change scores (RSA and PEP respectively), psychopathic traits, trait empathy, and state empathy (see ).

Differences between empathic and non-empathic responders

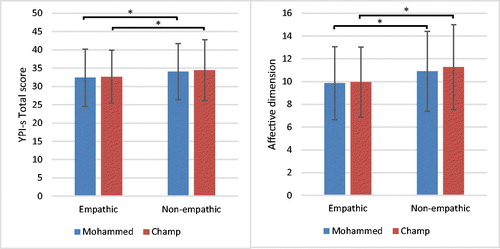

T-tests revealed that the non-empathic and empathic group, on both film clips, differed significantly on their scores of psychopathic traits (see ; ). The non-empathic groups scored significantly higher than the empathic groups on both the YPI-s total score, as well as the affective dimension of the YPI-s. Only for film clip Mohammed, did the non-empathic group score higher on the behavioral dimension of the YPI-s.

Figure 1. Self-reported psychopathic traits (YPI-s scores) for the empathic and non-empathic groups.

Table 2. Self-reported psychopathic traits (YPI-s scores) and autonomic nervous system (ANS) change scores for empathic and non-empathic groups for the film clips Mohammed and Champ.

Independent t-tests showed that the non-empathic group and the empathic group differed significantly with regard to their HR change score on the film clip Mohammed (see ; ), demonstrating less HR withdrawal for the non-empathic group. The same direction in mean values was observed for film clip Champ: less withdrawal for the non-empathic group, although the results failed to reach significance. Independent t-tests showed that the non-empathic group and the empathic group did not differ with regard to their sympathetic (PEP) and parasympathetic (RSA) reactivity.

Discussion

The main goal of the current study was to gain further insight into empathic functioning of detained juveniles with varying levels of psychopathic traits. Self-reported trait empathy, and self-reported and physiological correlates of state empathy, were studied in a large sample of detained adolescents and young adults in reaction to emotion eliciting film clips. Psychopathic traits were negatively associated with self-reported trait and state empathy. Contrary to our expectations, psychopathic traits and trait empathy were not associated with diminished withdrawal for any of the ANS parameters. For state empathy, only for the film clip Mohammed, the level of self-reported empathic sadness was correlated with HR withdrawal. When subdivided in an empathic and non-empathic group based on their self-reported state empathic responses, the non-empathic group showed significantly less HR withdrawal (i.e., a smaller reduction in HR) as compared to individuals with higher levels of self-reported state empathic sadness. This result was only significant for film clip Mohammed. No significant differences were found between the empathic and non-empathic group with regard to parasympathetic (PNS) and sympathetic (SNS) functioning.

Trait and state empathic responses

Trait empathy was significantly correlated with self-reported state empathic responses, but not with ANS responses. When comparing trait and state self-reported empathic responses, these measures show a medium strong positive association. This is in line with expectations, indicating that state and trait empathy are indeed part of the same construct. However, it also supports our surmise that trait and state empathy cannot be regarded as the same, for then an even stronger association would be expected. With respect to self-reported state empathy and ANS functioning, it was found that lower self-reported empathic sadness (i.e., lower empathic response) was related to a smaller HR withdrawal response, although this effect was only significant for one of the film clips (Mohammed). Other ANS parameters showed no significant associations with self-reported state empathy. Conform results of de Wied et al. (Citation2009), and in contrast to findings of Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous and Warden (Citation2008), our results showed concordance of self-report and physiological correlates. Based on these concordant results, there are no strong indications that self-report state empathy is an insufficiently valid measure of state empathy.

In the present study, empathic response to two different sad emotion elicitations differed. As might be expected, youths showed more self-reported and physiological empathic response to a stimulus with a higher emotional intensity (the death of a father) vs. a milder stimulus (failing soccer selection). As practically all participants correctly identified the targeted emotion sadness in both film clips, demonstrating cognitive empathy, it is not likely that differences in emotion recognition resulted in these observed differences in measures of affective empathy. However, decreased physiological response was only observed during the mild emotion elicitation. It seems the mild film clip evoked a more subtle empathic response, while film clip Champ—through providing a stronger stimulus—evoked greater HR withdrawal even in otherwise self-reported non-empathic individuals. As such, trait empathy may rather represent an overall picture someone has of himself, while state empathy offers extra information reflecting how an individual responds to a specific situation. We argue that use of state empathic responding could be more relevant, as this is able to provide insight into variations of empathic responding in different situations. Subsequently, this can provide relevant input for intervention tailored to the individual.

Psychopathic traits and trait and state empathy

Overall, it was found that individuals with higher levels of psychopathic traits reported lower levels of both trait and state empathy, as was expected based on previous research (e.g., Dadds et al., Citation2009). Associations were slightly stronger when only considering callous unemotional (CU)-traits (the affective component of psychopathic traits). This is not surprising, as this domain shows most overlap with diminished empathy. Likewise, when juveniles were classified as empathic or non-empathic based on their self-reported state empathic responses, non-empathic participants were found to have significantly more psychopathic traits and more CU-traits in specific. This leads us to conclude that in antisocial detained juveniles, higher levels of psychopathic traits are related to lower reported empathy, both on self-reported trait empathy and in response to the empathy eliciting stimuli. Of course, this is subject to variation, and it remains to be examined if the same is found in real life situations. The use of film clips in the generation of an emotional response, although seeming to be able to elicit the looked after response, remains of course an approximation of reality.

Contrary to our expectations, no significant correlations between psychopathic traits or CU-traits and ANS parameters were found. Notably, the range of psychopathic traits in our sample was quite small, because scores were relatively low. As it is often thought individuals in forensic settings should score on the higher end of this spectrum, this could be deemed surprising. However, this study is not the first in finding such results, for example Boonmann et al. (Citation2015) recently reported similarly in detained youth, where offending juveniles reported lower levels of psychopathic traits compared to youth from the general population. The authors argue this could be due to juvenile offenders’ reference group: when comparing their own behavior to that of their delinquent peers, their behavior could seem less severe than for individuals without delinquent peers, thus resulting in lower scores. It is not likely that the lower scores make our measure of psychopathic traits unreliable, as the direction of associations with other constructs were conform previous research (Vahl et al., Citation2014). However, as other studies using film clips and ANS factors in the assessment of empathy did demonstrate links between CU-traits and diminished ANS responding (Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous & Warden, Citation2008; de Wied et al., Citation2009, Citation2012), the lack of associations in the current sample may be due to the low variation in psychopathic traits.

However, after dividing our sample into an empathic and non-empathic group based on their state self-report, it was found that juveniles who did not report empathic sadness (vs. juveniles that did report empathic sadness) showed higher psychopathic traits, specifically CU-traits, and less HR withdrawal. While this final result failed to reach significance for film clip Champ, results were nonetheless in the same direction. These results are similar to the two studies performed in DBD samples, where DBD children with CU-traits showed less HR withdrawal compared to controls (Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous & Warden, Citation2008; de Wied et al., Citation2009). As heart rate is influenced both by sympathetic and parasympathetic activity, it was expected that more detailed information could be revealed by examining the two branches of the ANS separately. Given the status of RSA as a biomarker for emotion regulation (Beauchaine, Citation2015), differences were mainly expected in the area of PNS activity. However, no significant associations between these parameters and psychopathic traits were found, nor did the empathic and non-empathic group differ on PNS and SNS parameters. This is conform several previous studies that have investigated the different branches of the ANS, where no differences were found between DBD participants and controls for either sympathetic (PEP; Marsh et al., Citation2008) and parasympathetic reactivity (RSA; Marsh et al., Citation2008; Zahn-Waxler et al., Citation1995). More research is needed to disentangle the mechanisms of the different branches of the ANS in empathic functioning in antisocial juveniles.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge this is the first study with such high inclusion numbers in a sample of detained adolescents and young adults. Furthermore, few studies on empathy have focused on state empathic functioning, and even fewer studies investigated (both branches of) ANS reactivity. However, some limitations to the study should be noted. First, short versions of the instruments intended to measure psychopathic traits and trait empathy were used for this study, possibly leading to a limitation in variance. This was decided to minimize burden on participants and to create a test battery that could be easily implemented without taking too much extra time. However, relationships were in the expected directions consistent with previous research findings.

Second, the adopted measure of self-reported state empathy was perhaps too simplistic. The variation in scores of empathic responders was low due to limited range in possible scores on the 5-point scale and the large amount of self-reported non-empathic response to the film clips. This may have hampered the correlational analyses. It is possible that this limitation could be overcome in future research by applying a more extensive measure of self-reported state empathy. However, a low score on empathic response is also in line with what would be expected in this group of detained juveniles. Furthermore, detained juveniles are often found to have a low IQ (e.g., Hayes & Reilly, Citation2013), therefore a simple operationalization may not be particularly sophisticated, yet may be appropriate for such samples. Finally, multiple tests per research question had to be performed, therefore, results should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions and clinical implications

The current study confirms the negative correlation between psychopathic traits and trait and state empathy in detained juveniles. Moreover, detained juveniles reporting less state empathy actually show less HR withdrawal (i.e., less physiological reactivity) to an empathy invoking stimulus and higher psychopathic traits. However, this was not related to trait empathy. This implies that physiological responses to empathy-inducing stimuli may be helpful in identifying those juveniles with severely impaired empathic functioning and high psychopathic traits, even in a severely antisocial sample. This may be important for the indication for treatment focused on increasing empathic functioning. Research has shown that severity of a subsequent committed crime was lower when there was a focus on emotion recognition during treatment (Hubble, Bowen, Moore, & van Goozen, Citation2015). Possibly even greater improvement could be achieved when for example biofeedback is added to enhance empathic response. However, further research is needed to determine which of the two components of empathy, trait, or state, is more strongly associated with course of treatment and future (antisocial) behavior. The same goes for questionnaires versus physiological measurements. As more information is gathered on empathic functioning via different or multiple perspectives, this may facilitate treatment focused on strengthening empathic ability.

References

- Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous, X., & Warden, D. (2008). Physiologically-indexed and self-perceived affective empathy in conduct-disordered children high and low on callous-unemotional traits. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 39(4), 503–517. doi:10.1007/s10578-008-0104-y

- Andershed, H. A., Kerr, M., Stattin, H., & Levander, S. (2002). Psychopathic traits in non-referred youths: A new assessment tool. In E. Blaauw & L. Sheridan (Eds.), Psychopaths: current international perspectives (pp. 131–158), The Hague: Elsevier.

- Beauchaine, T. P. (2015). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia: A transdiagnostic biomarker of emotion dysregulation and psychopathology. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 43–47. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.01.017

- Beauchaine, T. P., Gatzke-Kopp, L., & Mead, H. K. (2007). Polyvagal theory and developmental psychopathology: Emotion dysregulation and conduct problems from preschool to adolescence. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 174–184. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.08.008

- Berntson, G. G., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2007). Integrative physiology: Homeostasis, allostasis and the orchestration of systemic physiology. In Handbook of psychophysiology (Vol. 3, pp. 433–452). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Berntson, G. G., Cacioppo, J. T., Quigley, K. S., & Fabro, V. T. (1994). Autonomic space and psychophysiological response. Psychophysiology, 31(1), 44–61. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb01024.x

- Berntson, G. G., Norman, G. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2008). Cardiac autonomic balance versus cardiac regulatory capacity. Psychophysiology, 45(4), 643–652. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00652.x

- Blair, R. J. R. (1999). Responsiveness to distress cues in the child with psychopathic tendencies. Personality and Individual Differences, 27(1), 135–145. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00231-1

- Blair, R. J. R. (2007). Empathic dysfunction in psychopathic individuals. In Empathy in mental illness (pp. 3–16). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Blair, R. J. R., Budhani, S., Colledge, E., & Scott, S. (2005). Deafness to fear in boys with psychopathic tendencies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(3), 327–336. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00356.x

- Blair, R. J. R., & Coles, M. (2000). Expression recognition and behavioural problems in early adolescence. Cognitive Development, 15(4), 421–434. doi:10.1016/S0885-2014(01)00039-9

- Blair, R. J. R., Colledge, E., Murray, L., & Mitchell, D. (2001). A selective impairment in the processing of sad and fearful expressions in children with psychopathic tendencies. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29(6), 491–498. doi:10.1023/A:1012225108281

- Blandon, A. Y., Calkins, S. D., Keane, S. P., & O'Brien, M. (2008). Individual differences in trajectories of emotion regulation processes: The effects of maternal depressive symptomatology and children's physiological regulation. Developmental Psychology, 44(4), 1110. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1110

- Boonmann, C., Jansen, L. M., ’t Hart-Kerkhoffs, L. A., Vahl, P., Hillege, S. L., Doreleijers, T. A., & Vermeiren, R. R. (2015). Self-reported psychopathic traits in sexually offending juveniles compared with generally offending juveniles and general population youth. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 59(1), 85–95. doi:10.1177/0306624X13508612

- Bos, M. G., Jentgens, P., Beckers, T., & Kindt, M. (2013). Psychophysiological response patterns to affective film stimuli. PLoS One, 8(4), e62661. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062661

- Broidy, L., Cauffman, E., Espelage, D. L., Mazerolle, P., & Piquero, A. (2003). Sex differences in empathy and its relation to juvenile offending. Violence and Victims, 18(5), 503–516. doi:10.1891/vivi.2003.18.5.503

- Bryant, B. K. (1982). An index of empathy for children and adolescents. Child Development, 53(2), 413–425. doi:10.2307/1128984

- Cacioppo, J. T., Uchino, B. N., & Berntson, G. G. (1994). Individual differences in the autonomic origins of heart rate reactivity: The psychometrics of respiratory sinus arrhythmia and preejection period. Psychophysiology, 31(4), 412–419. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb02449.x

- Calkins, S. D., Graziano, P. A., & Keane, S. P. (2007). Cardiac vagal regulation differentiates among children at risk for behavior problems. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 144–153. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.09.005

- Colins, O. F., Noom, M., & Vanderplasschen, W. (2012). Youth psychopathic traits inventory-short version: A further test of the internal consistency and criterion validity. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 34(4), 476–486. doi:10.1007/s10862-012-9299-0

- Dadds, M. R., Hawes, D. J., Frost, A. D., Vassallo, S., Bunn, P., Hunter, K., & Merz, S. (2009). Learning to ‘talk the talk’: The relationship of psychopathic traits to deficits in empathy across childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(5), 599–606. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02058.x

- de Geus, E. J., Willemsen, G. H., Klaver, C. H., & van Doornen, L. J. (1995). Ambulatory measurement of respiratory sinus arrhythmia and respiration rate. Biological Psychology, 41(3), 205–227. doi:10.1016/0301-0511(95)05137-6

- de Wied, M., Goudena, P. P., & Matthys, W. (2005). Empathy in boys with disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(8), 867–880. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00389.x

- de Wied, M., Maas, C., van Goozen, S., Vermande, M., Engels, R., Meeus, W., … Goudena, P. (2007). Bryant's empathy index. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 23(2), 99–104. doi:10.1027/1015-5759.23.2.99

- de Wied, M., van Boxtel, A., Matthys, W., & Meeus, W. (2012). Verbal, facial and autonomic responses to empathy-eliciting film clips by disruptive male adolescents with high versus low callous-unemotional traits. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(2), 211–223. doi:10.1007/s10802-011-9557-8

- de Wied, M., van Boxtel, A. V., Posthumus, J. A., Goudena, P. P., & Matthys, W. (2009). Facial EMG and heart rate responses to emotion-inducing film clips in boys with disruptive behavior disorders. Psychophysiology, 46(5), 996–1004. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00851.x

- Dong, L., Wu, H., & Waldman, I. D. (2014). Measurement and structural invariance of the antisocial process screening device. Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 598–608. doi:10.1037/a0035139

- Eisenberg, N., & Fabes, R. A. (1990). Empathy: Conceptualization, measurement, and relation to prosocial behavior. Motivation and Emotion, 14(2), 131–149. doi:10.1007/BF00991640

- Fernández, C., Pascual, J. C., Soler, J., Elices, M., Portella, M. J., & Fernández-Abascal, E. (2012). Physiological responses induced by emotion-eliciting films. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 37(2), 73–79. doi:10.1007/s10484-012-9180-7

- Flight, J. I., & Forth, A. E. (2007). Instrumentally violent youths: The roles of psychopathic traits, empathy, and attachment. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(6), 739–751. doi:10.1177/0093854807299462

- Fortunato, C. K., Gatzke-Kopp, L. M., & Ram, N. (2013). Associations between respiratory sinus arrhythmia reactivity and internalizing and externalizing symptoms are emotion specific. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 13(2), 238–251. doi:10.3758/s13415-012-0136-4

- Gao, Y., Raine, A., & Schug, R. A. (2012). Somatic aphasia: Mismatch of body sensations with autonomic stress reactivity in psychopathy. Biological Psychology, 90(3), 228–233. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.03.015

- Gentzler, A. L., Santucci, A. K., Kovacs, M., & Fox, N. A. (2009). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia reactivity predicts emotion regulation and depressive symptoms in at-risk and control children. Biological Psychology, 82(2), 156–163. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.07.002

- Gross, J. J., & Levenson, R. W. (1995). Emotion elicitation using films. Cognition & Emotion, 9(1), 87–108. doi:10.1080/02699939508408966

- Grossman, P., & Taylor, E. W. (2007). Toward understanding respiratory sinus arrhythmia: Relations to cardiac vagal tone, evolution and biobehavioral functions. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 263–285. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.11.014

- Hayes, M. J., & Reilly, G. O. (2013). Psychiatric disorder, IQ, and emotional intelligence among adolescent detainees: A comparative study. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 18(1), 30–47. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8333.2011.02027.x

- Hewig, J., Hagemann, D., Seifert, J., Gollwitzer, M., Naumann, E., & Bartussek, D. (2005). Brief report. Cognition & Emotion, 19(7), 1095–1109. doi:10.1080/02699930541000084

- Hubble, K., Bowen, K. L., Moore, S. C., & van Goozen, S. H. (2015). Improving negative emotion recognition in young offenders reduces subsequent crime. PLoS One, 10(6), e0132035. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132035

- Jones, A. P., Happé, F. G., Gilbert, F., Burnett, S., & Viding, E. (2010). Feeling, caring, knowing: Different types of empathy deficit in boys with psychopathic tendencies and autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(11), 1188–1197. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02280.x

- Klaver, C., De Geus, E., & De Vries, J. (1994). Ambulatory monitoring system. In F. J. Maarse (Ed.), Computers in psychology 5, Applications, methods, and instrumentation (pp. 254–268). Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger.

- Kreibig, S. D., Wilhelm, F. H., Roth, W. T., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Cardiovascular, electrodermal, and respiratory response patterns to fear- and sadness-inducing films. Psychophysiology, 44(5), 787–806. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00550.x

- Lodewijks, H. P. B., & van Domburgh, L. (2012). Inleiding en overzicht van risicotaxatie-instrumenten voor jeugdigen in Nederland. In H. P. B. Lodewijks, & L. van Domburgh (Eds.), Instrumenten voor risicotaxatie kinderen en jeugdigen (pp. 11–20). Amsterdam, Nederland: Pearson.

- Lovell, D. P., & Zeffirelli, F. D. (1979). The champ [Motion picture]. United States: MGM/Pathe Home Video.

- Marsh, P., Beauchaine, T. P., & Williams, B. (2008). Dissociation of sad facial expressions and autonomic nervous system responding in boys with disruptive behavior disorders. Psychophysiology, 45(1), 100–110. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00603.x

- Nentjes, L., Meijer, E., Bernstein, D., Arntz, A., & Medendorp, W. (2013). Brief communication: Investigating the relationship between psychopathy and interoceptive awareness. Journal of Personality Disorders, 27(5), 617–624. doi:10.1521/pedi_2013_27_105

- Pang, K. C., & Beauchaine, T. P. (2013). Longitudinal patterns of autonomic nervous system responding to emotion evocation among children with conduct problems and/or depression. Developmental Psychobiology, 55(7), 698–706. doi:10.1002/dev.21065

- Pfabigan, D. M., Seidel, E. M., Wucherer, A. M., Keckeis, K., Derntl, B., & Lamm, C. (2015). Affective empathy differs in male violent offenders with high- and low-trait psychopathy. Journal of Personality Disorders, 29(1), 42–61. doi:10.1521/pedi_2014_28_145

- Piferi, R. L., Kline, K. A., Younger, J., & Lawler, K. A. (2000). An alternative approach for achieving cardiovascular baseline: Viewing an aquatic video. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 37(2), 207–217. doi:10.1016/S0167-8760(00)00102-1

- Prätzlich, M., Oldenhof, H., Steppan, M., Ackermann, K., Baker, R., Batchelor, M., … Dikeos, D. (2018). Resting autonomic nervous system activity is unrelated to antisocial behaviour dimensions in adolescents: Cross-sectional findings from a European multi-centre study. Journal of Criminal Justice. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2018.01.004

- Quiggle, N. L., Garber, J., Panak, W. F., & Dodge, K. A. (1992). Social information processing in aggressive and depressed children. Child Development, 63(6), 1305–1320. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01696.x

- Rottenberg, J., Ray, R. D., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Emotional Elicitation Using Films. In J. A. Coan & J. J. B. Allen (Eds.), The handbook of emotion elicitation and assessment. London: Oxford University Press.

- Salekin, R. T., & Lynam, D. R. (2010). Handbook of Child and Adolescent Psychopathy. New York City, NY: Guilford Press.

- Scarpa, A., Haden, S. C., & Tanaka, A. (2010). Being hot-tempered: Autonomic, emotional, and behavioral distinctions between childhood reactive and proactive aggression. Biological Psychology, 84(3), 488–496. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.11.006

- Schafer, J. L. (1997). Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- Sommer, M., Hajak, G., Döhnel, K., Schwerdtner, J., Meinhardt, J., & Müller, J. L. (2006). Integration of emotion and cognition in patients with psychopathy. Progress in Brain Research, 156, 457–466. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(06)56025-X

- Stevens, D., Charman, T., & Blair, R. (2001). Recognition of emotion in facial expressions and vocal tones in children with psychopathic tendencies. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 162(2), 201–211. doi:10.1080/00221320109597961

- Vahl, P., Colins, O. F., Lodewijks, H. P., Markus, M. T., Doreleijers, T. A., & Vermeiren, R. R. (2014). Psychopathic-like traits in detained adolescents: Clinical usefulness of self-report. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 23(8), 691–699. doi:10.1007/s00787-013-0497-4

- van Baardewijk, Y., Andershed, H., Stegge, H., Nilsson, K. W., Scholte, E., & Vermeiren, R. (2010). Development and tests of short versions of the youth psychopathic traits inventory and the youth psychopathic traits inventory-child version. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 122–128. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000017

- Vaughn, M. G., Howard, M. O., & DeLisi, M. (2008). Psychopathic personality traits and delinquent careers: An empirical examination. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 31(5), 407–416. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2008.08.001

- Willemen, A. M., Schuengel, C., & Koot, H. M. (2009). Physiological regulation of stress in referred adolescents: The role of the parent–adolescent relationship. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(4), 482–490. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01982.x

- Zahn-Waxler, C., Cole, P. M., Welsh, J. D., & Fox, N. A. (1995). Psychophysiological correlates of empathy and prosocial behaviors in preschool children with behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology, 7(01), 27–48. doi:10.1017/S0954579400006325

Appendix

Table A.1. Descriptive statistics for autonomic nervous system (ANS) measures for the different conditions of the emotion evocation task.