Abstract

The risk of patients committing violence implies major challenges throughout the care process in forensic psychiatry and brings risk assessments to the fore. The aim was to explore nurses’ experiences of risk assessments for their care planning and risk management in forensic psychiatry. Data were collected through focus groups with 15 nurses. The qualitative content analysis followed a deductive approach guided by the person-centered philosophy. When exploring nurses’ reasoning on risk assessment, units related to person-centered principles were identified. The findings showed that nurses made great efforts to confirm the unique person behind the patient, even when challenged by patients’ life histories of violence. They also regarded therapeutic alliance as crucial, although this needed to be balanced between caring and restricting actions. A fruitful strategy to preserve therapeutic alliance may be to increase the use of a structured focus on protective factors in treatment plans towards promoting recovery-oriented policies and practices.

Introduction

We conducted a qualitative study, exploring mental health nurses’ experiences of risk assessments and their use for care planning in forensic psychiatry. In addition, we wanted to elucidate whether the person-centered approach, now well-integrated into care in general, could be identified in mental health nurses’ reflections on risk assessments, a research area where knowledge is still scarce (McCormack, Karlsson, Dewing, & Lerdal, Citation2010; McCormack & McCance, Citation2006). We used three central concepts within the person-centered approach as the main analytical tool by which data were interpreted; “Person”, “Relation”, and “Agreements” (Ekman et al., Citation2011). The concept of “Person” deals with confirming the person behind the patient by listening to his/her personal story. This means acquiring knowledge about the person; relating to them as a capable human being, with physical and intellectual abilities, as well as having personal and interpersonal assets such as joy, motivation and desires (Robeyns, Citation2006). The concept of “Relation”, or partnership, deals with the mutual respect for the knowledge and experience of the patient and the carer, seeing the patient as an equally important participator in all aspects of care, treatment and rehabilitation (Slater, Citation2006). This concept aligns well with Peplaus’ theory of interpersonal relations (Peplau, Citation1997) and its framework for understanding patients’ dilemmas within the domain of professional nursing practice. According to the person-centered approach, the patient’s story is crucial and should be structured and documented in conjunction with the patient. The mutual agreement between patient and care-giver is secured in a care plan in the patient records (Ekman et al., Citation2011). The concept of “Agreement” deals with the dialog and shared decision-making process that takes place between the patient and the care-team (Ekman et al., Citation2011).

Forensic psychiatric care is challenged by the complexity of the patient’s psychiatric status, the legal aspects of the treatment, the protection of society, and the risk of the patients committing violence in the future (Munthe, Radovic, & Anckarsäter, Citation2010). Confirming the patient as an autonomous person, in line with the person-centered approach, can therefore meet specific challenges, particularly in relation to the patient’s complex mental health needs and because the care is provided under involuntary conditions (Radovic & Höglund, Citation2014). Nurses are at the forefront of meeting these inconsistent demands; that is to say, balancing between violence risk while at the same time inviting the patient to be engaged in and have influence on their care (Hinsby & Baker, Citation2004; Urheim, Rypdal, Palmstierna, & Mykletun, Citation2011). Nurses thereby need to take on an essential role, not only in supporting patients to gain insight into their criminal behavior and in helping them to understand how this can affect their future lives (Rask & Levander, Citation2001), but also in being sensitive to those patients who might not have the immediate capability to be engaged in changing their behavior (Nussbaum, Citation2011). The planning of the patient’s reintegration into society is therefore of great importance, including nurse-patient cooperation in the assessment of needs and care-planning (Gustafsson, Holm, & Flensner, Citation2012).

Assessment of risk for future violence is an important feature in this reintegration process, as it is a specialized element of forensic psychiatric care (Doyle & Dolan, Citation2002). It is based on structured instruments such as the Historical Clinical Risk management (HCR-20) instrument (Douglas, Hart, Webster, & Belfrage, Citation2013), which aims to identify historical, clinical, and contextual risk factors for future violent behavior, which in turn highlight possible future risk situations. However, acknowledgement from patients about such risk factors, as well as obtaining their agreement with the results of the assessment and interventions, is not always sought or achieved. On the contrary, there are instances when agreement is sought and achieved, such as when risk assessment is conducted in order to support the managing of a person who may not be engaged in a collaborative process.

Over the last few decades, forensic psychiatric care has undergone a change; from its former ethos of placing a focus strictly on risks, to the inclusion of protective factors, supported by the belief that both factors could be useful and motivational for patients and staff (de Vogel, de Vries Robbé, de Ruiter, & Bouman, Citation2011; de Vogel, de Ruiter, Bouman, & de Vries Robbé, Citation2011). An instrument called the Structured Assessment of Protective Factors for Violence Risk (SAPROF) (de Vogel, de Ruiter, Bouman, & de Vries Robbé, Citation2009) identifies and measures the presence of protective factors and thereby offers the potential of obtaining a more comprehensive understanding of the patient’s needs, taking into consideration both protective and risk factors. SAPROF (de Vogel, et al., Citation2011) was implemented in addition to HCR-20, in a forensic psychiatric clinic in the south of (Sweden), and has been used routinely since 2012 in combination with traditional risk assessments.

Previous research on risk assessments in mental health care has focused on the predictive validity of risk assessment tools (Doyle & Dolan, Citation2002), as well as on instruments that promote increased patient involvement in risk assessment and the integration of protective factors/patients’ strengths, such as the START instrument (Nicholls, Brink, Desmarais, Webster, & Martin, Citation2006; Webster, Martin, Brink, Nicholls, & Desmarais, Citation2009). However, there is a growing interest in health professionals’ experiences in their use of these instruments.

The impact of person-centered care has proved to be successful when considering higher quality of care in terms of earlier hospital discharge and cost savings (Hansson et al., Citation2016), e.g., after chronic heart failure (Dudas, Schaufelberger, & Swedberg, Citation2012; Dudas et al., Citation2013) and in orthopedic care (Olsson, Hansson, & Ekman, Citation2016). This has led to a mounting interest at both governmental and policy-making levels for this approach, advocating its implementation in a broader sense (Ekman, Hedman, Swedberg, & Wallengren, Citation2015). The ambition of enabling patients to be more involved in their own care-planning and treatment (McCormack & McCance, Citation2006), and in health promotion (Bandura, Citation2004) through improved relationships and dialog with the health-care team, is in line with a person-centered approach. Although Livingston, Nijdam-Jones, and Brink (Citation2012) also found that this approach was compatible within forensic psychiatric care according to patients and service providers, the evidence is scarce and needs to be further investigated.

Nurses have the overall responsibility for caring, which includes supporting and maintaining optimal health and strengthening personal resources. Risk assessments may provide opportunities to enhance the nurse-patient interaction (Rask & Levander, Citation2001), and the patient’s participation, but it can also be regarded as a vulnerable action, with the potential to have a negative influence on caring relationships, rehabilitation, and length of stay. To date, this issue has only been considered from the wider perspective of policy implementation and funding implications. There is a lack of knowledge considering the impact of the focus on risk assessments in forensic psychiatry from the perspective of mental health nurses. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore mental health nurses’ experiences of risk assessments within their care planning and management of risks for violence by forensic patients.

Methods

Recruitment and participants

A purposive sampling strategy was used for the recruitment of participants, from the forensic psychiatric clinics in two regions in (Sweden). The recruitment process was supported by the managers of the wards. A preliminary request for participation, along with written information about the aims and conditions for participating, was distributed to all registered nurses in order to achieve a wide range with regard to their professional experience, age and level of education. The inclusion criteria for participating nurses were set as: having a minimum of one -year of work experience of performing assessments of patients’ risk of violence; and working during the daytime. Nurses working in out-patient settings were excluded. The nurses who were interested in participating received detailed written information, sent by e-mail. The forensic psychiatric clinics in the south region consisted of seven wards, of which three were represented in two focus groups. The wards that were not represented either had no nurses employed who met the inclusion criteria, or lacked interest in participating. In the western region, all five wards were represented in one focus group. Finally, fifteen nurses (six men, nine women) participated.

Data collection

Using focus groups is a particularly suitable method when exploring experiences and attitudes. The interactions between the participants are essential and the group discussions can encourage the participants to widen their views (Kitzinger, Citation1995). The nurses were given the opportunity to freely describe their experiences of risk assessments and risk management, guided by two open-ended questions that were further elaborated when needed; “what is your experiences of risk assessments? Could you give examples of when risk assessments can be useful for your care planning?”

The focus group interviews were conducted by two researchers; one moderated the discussions, and the other made notes of the group interactions to capture nonverbal communication (Kitzinger, Citation1995). The focus group interviews took place in a secluded environment, chosen by the participants and adjacent to their workplaces. The focus groups were audio-recorded and then transcribed verbatim. The focus groups lasted approximately 70–90 min.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, Citation2013). The study was approved by the research ethics committee at the Ethics Committee of (Lund) (registration number: 2013/329). All study participants were provided with both verbal and written information about the study. They were informed that their participation was voluntary, and that they could withdraw at any time, without providing any explanation and without any consequences for their work situation. In addition, the participants were assured that the data would be kept confidential and that their names would be replaced with a code. It was explained that data would only be presented at the group level without the possibility of identifying any individual informant. All participants gave their informed consent to join the study.

Data analysis

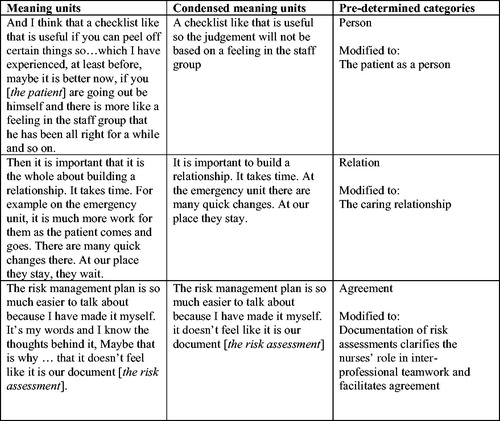

The content of the focus groups was explored using qualitative content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005), to learn whether the nurses’ reasoning on risk assessment and care planning was related to person-centered characteristiques. We used a deductive approach to explore whether the concept and central principles of a person-centered approach, which nowadays is integrated in nurses’ care planning in general, also could be identified in the specific context of forensic psychiatry. Deduction begins with developing predictions of an expected pattern, here, the person-centered concept, that are tested against observations, as well as searching for unknown patterns in the material (Babbie, Citation2010; Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008; Polit & Beck, Citation2017). The analysis proceeded from the three main concepts within person-centered care; Person, Relation, and Agreement, and started by the researchers reading the transcriptions several times to obtain a sense of the whole. Thereafter, meaning units that comprised wordings, or sentences of paragraphs that could be related to the three concepts, were identified. The meaning units were condensed, labeled with a code (), and then categorized into the three pre-determined categories, including several sub-categories. In every step of the analyzing process the content was discussed back and forth between the first and the last researcher until consensus was reached. All four researchers agreed with the final results.

Results

The findings presented below are supported by quotes from the focus groups. Each bold heading represents a deductive category, with sub-categories indicated by italics, as illustrated in .

Table 1. Categories and sub-categories revealed during the analysis.

The patient as a person

The nurses reflected on their opportunity to consider patients in relation to their individual needs and resources. Their experiences of risk assessments encompassed two sub-categories.

Opportunities to confirm the patient as a person

The nurses described how they made daily observations of the patients followed by ongoing intrinsic risk assessments that were related to known risk of rapid mood change among the patients. The HCR-20 instrument served as a checklist and supported the assessments, minimizing the risk of subjective evaluations.

It is not always like that but sometimes it has been like you don’t sit down and think about it, what… happens if he runs off or… how has it been before and so, but you do it in a slapdash way. So then a checklist is good or that kind of instrument to use, I think.

Nevertheless, the instrument was not able to grasp the “whole picture” of the patient. The nurses endeavored to attain comprehensiveness and stressed the importance of focusing on the patient’s resources and their obligation to support these resources throughout the length of stay, which was considered to be a quality indicator of good care.

It can be that the patient is interested in music for example. It is to maintain this resource in the patient so we don’t destroy it … So that he will continue with the music at the Activity house and make discs and so on. At the same time he diverts the psychotic issues that he has. Then it will be higher quality of care.

It was considered to be important to focus on preventive actions instead of merely establishing certain risks. However, establishing risks could at the same time provide crucial information about the patient, which in turn made the nurses pay attention to specific problem areas. The usually long inpatient stay was perceived as a possibility to observe the patients around the clock for a long period of time. This increased the opportunities to identify both risk- and protective factors, and to confirm and consolidate the patients’ resources, which, in turn, supported their protective factors. The protective factors were described as those that met patients’ needs in an appropriate way. The problem-based approach was perceived to be easier to cope with, but placing a focus on resources as potential protective factors was more aligned with the caring process and was therefore considered more often.

So you have to try not to problematize so much, instead focus on the good and the positive. Then it is very easy sometimes, to take the easy way out and just enumerate everything the patient can’t do. But I think that the result will be better if it is reversed.

Barriers to confirming the patient as a person

The nurses placed great importance on the patients’ stories about their former life situations before they were hospitalized, particularly when they planned to promote the patients’ participation in their care. If the patient’s story comprised extensive violence and the committing of crimes, the nurses were concerned that this could have a negative influence on them while they assessed the patient’s risk factors and care decisions, forcing them to be rigid in their assessment and planning practices.

It is very difficult and it happens easily that we just see the negative, and we take away their resources. We just see the problems and then maybe think a little bit square [author’s translation: meaning that the nurses sometimes can be rigid in their thinking about potential ways to resolve issues] rather than…

There were several barriers to establishing a relationship with the patient and in confirming the person behind the patient to acknowledge them as an individual. For example, one barrier was the sheltered environment of the ward, which limited the occurrence of common risk situations with which the patient was normally confronted when not hospitalized. The absence of relatives in the care process was another barrier to getting the “true” picture of the person behind the patient. On the other hand, the patients’ relationships with family members were sometimes complicated. For example, if the family member acted as an accuser (e.g., if they had been molested by the patient and had reported them), their participation in the care could come at great psychological expense, which, in turn, could affect opportunities to provide good care.

Sometimes it is difficult as nursing staff to on the one hand, take advantage of the kind of protection they (the relatives) actually contribute to, that they really are protective factors. Because, sometimes the patient is ready one day, and not the next day … A lot of the patients have complicated relationships with their relatives…

The lack of tools assessing protective factors in a structured way was another barrier in confirming the patients’ resources. The nurses stressed that there was a risk of not paying enough attention to the patients’ resources (mostly used as a synonym for protective factors), which indirectly affected the possibility to confirm the patients as unique individuals.

The caring relationship

The importance of establishing a relationship with patients occurred frequently as a prominent feature. The category resulted in three sub-categories.

Creating a trusting lasting relationship

The often prolonged length of stay, made it possible to create trusting and lasting relationships with patients. Contributing aspects included keeping the patient informed and prepared before meetings, as well as regarding the patient as a team member and a vital person with whom to discuss risk factors and management strategies.

Well, when they can join and be able to decide. When they are able to participate in the team, and they can bring up what they want to do and how they would like it and so on.

Another aspect that was mentioned was that the nurses postponed their recording of the patient’s background until after they had arrived on the ward, in order to create a first encounter with the patient that was as caring and trusting as possible. Creating and maintaining a good relationship was a priority assignment and was particularly important in challenging situations when discussing negative decisions, such as refusing permission or other privileges. Additionally, involving the patient in care planning contributed to the patient’s awareness of the arguments related to the risk assessment.

That’s what I meant, the relationship, since we have built it up so well (the relationship), it will manage the bumps. Sure, they can get grumpy and irritated but it will soon be over.

Balancing between caring and restricting actions challenge the relationship

To be responsible for the treatment and to care for the patient’s well-being, as well as to supervise, and carry out restrictions, is a challenge for the development of a caring relationship.

Then it will be that kind of discussion; are we here to care or to guard? That always appears. We do both. When you have to be between the two, how you proceed, sensitiveness, treatment, relationship.

Talking about the results and consequences of the risk assessments could sometimes damage the development of a caring relationship which was particularly difficult to deal with when the nurse did not have the opportunity to participate in the assessment process. In these cases it was frustrating for the nurses to deliver negative decisions “made by the team” based on identified risk factors which they had not been part of.

The impact of the patients’ reactions

The nurses experienced that some patients were nervous and worried about the consequences of the assessment. Being trustworthy towards the patient was, in this respect, a complicating aspect, because, at the same time, the patients were mostly well aware of their situations and knew why they were in treatment. Reactions varied and were connected to the diagnosis, the patient’s level of awareness of their illness, and the nurses’ treatment of the patient. Patients’ reactions were also linked to not participating:

Why can’t they participate when we are sitting in a room, talking about him? “Why are you talking without my presence?” Things like that can arise.

Documentation of risk assessments clarifies the nurses’ role in inter-professional teamwork and facilitates agreement

Documentation was considered to be useful to highlight the supportive aspects of risk assessments and risk management for caring as well as the importance of nurses’ participation in the team and their opportunity to represent the patients in different situations, such as team meetings.

Documentation as support for argumentation and transparency

Several documents supported the agreements that had been made with the patient. The risk assessments acted both as an argument for when patients applied for privileges in the Administrative Court (these courts deal with forensic psychiatric cases, among others, and thereby have legislative authority to decide how all privileges, including discharges, are enacted) and as a summary that was transferred to the care plan, and making the information that is held about the patient’s risks available to the care professionals and the patient.

The risk management plan acted as a scheme where explicit risk situations were expressly identified together with suggestions of how the patient and staff could deal effectively with them. This plan was constructed primarily by the nurse in collaboration with the patient, based on the information concluded from the risk assessment. It facilitated aspects of care such as reaching the patient in the “difficult” discussions about risk behaviors and how to manage risk situations. The care plan acted as a summary of all of the important aspects concerning the patient’s care process, including both risk and protective factors.

The various documents of agreement placed demands on the nurses to be prepared and well-informed, which in turn was difficult when they were not invited to risk assessment meetings, despite being expected to express and discuss these questions with the patient in an appropriate way. In addition, in order to prepare a useful risk management plan, the nurses needed information from the risk assessment. The risk management plan functioned as a follow-up to the risk assessment. Wards that did not use management plans lacked structure for coping with identified risks, which may have led to risk factors being neglected.

If you recieve a risk assessment [conducted by another member of the care team], well, [it says] “This is what we concluded. These are the risk factors and protective factors we have identified,” then you don’t really… well [you wonder], what did they meant by this, and what were they thinking here? And the patients maybe don’t have a clue at all. I think it is better when it is close to you and when I have been participating and involved in writing the document, more or less. Or at least been participating in the discussion.

When nurses were not directly involved in the risk assessments and had only the concluding remarks to relay to the patient, this created gaps in their knowledge, prevented them from identifying potential risks, and disrupted their ability to promote the patient’s participation in their care decisions.

Documentation supports team communication

Documented agreements were also discussed in relation to partnership/teamwork in terms of increasing the feeling of being a part of the team. Situations were described where risk assessments were conducted with all involved staff members present; the physician, psychologist, social worker, physiotherapist, and nurse, which provided an opportunity to consider different opinions and views, and putting the caring aspects into broader focus. Various observations were discussed and considered by the team which supported a common understanding and respect for each other’s competences and skills. Another aspect of increased participation was that risk factors in general became more highlighted on an everyday basis. In that way, taking part in team discussions supported the nurses’ possibility to argue for and explain to patients about their care situations.

It has had an impact on the way we manage the care, through our involvement in the risk assessments, in a different manner than before. From the beginning when I started here, the risk assessment was always something that the doctor did in his office.

On the contrary, feelings of not being a part of the risk assessment process reduced nurses’ level of experience and an insecurity relating to the relevance of care aspects, but also produced a sense of being left outside, resulting in a lack of being given important information. In this situation, risk assessments came to be regarded as less important documents for the nurses.

Discussion

This study explored the nurses’ experiences of risk assessments in the forensic psychiatric care process. A crucial finding was the importance that the nurses placed on confirming the patient as a unique person. However, the ambition of confirming the patient as a unique person could sometimes conflict with certain provocative facts from the patient’s history that were challenging for the nurse to overlook. Similarly, Mezey, Kavuma, Turton, Demetriou, and Wright (Citation2010) found that the stigma of past offending behavior was perceived as hindering the recovery of patients who were detained in a medium-secure unit. This indicates the dual task in caring; confirming the person behind the criminal offender, and at the same time being aware of the risk of potential violent behavior. In our study, the influence of historical factors had a strong impact on the assessed risk of future violence, which the nurses tried to balance by emphasizing the need to increase patients’ resources. The same was found by Mezey et al. (Citation2010), where the nurses were challenged by the tension between a need to establish elements of restriction related to the risk assessment, and the autonomy and self-management of the patient.

It is clear from this and other studies (e.g., Olsson & Schön, Citation2016) that the assessment of the patients’ behavior is a constant ongoing process among the nurses in order to create and evaluate individual care actions. In this process, it seems as though the accessibility of an assessment tool facilitates the nurses’ ability to structure the judgment and to avoid relying on “gut feeling.” Godin (Citation2004) found, among community mental health nurses, that, in addition to an assessment tool, their assessments also relied on “professional intuition.” Doyle and Dolan (Citation2002), on the other hand, emphasized the need to provide nurses with supportive decision-making methods related to risk assessment and management.

Another key finding indicates that risk assessments seem to be useful in order to obtain information covering historical, as well as clinical factors, which is important for providing a more comprehensive picture of the patient. According to the principles of person-centeredness, relatives or other persons who know the patient well can contribute with valuable input (Leplege et al., Citation2007) to maintain a balanced picture of the patient, comprising both individual characteristics and criminal-related features. The nurses in our study stressed that the risk of excluding families from being part of the assessment was a hindrance to getting a “true” picture of the patient. The risk of not getting relatives involved in the patients’ rehabilitation has also been recognized by Gustafsson and colleagues (2012), who stress that a well-informed social network is essential for an effective admission.

In line with the increased interest in incorporating and combining risk assessments with protective factors over the last decade (de Vries Robbé, de Vogel, Douglas, & Nijman, Citation2015), the present study found that placing a stronger focus on seeing the patients’ resources as protective factors indicated a more optimistic and motivating direction in care, where the use of SAPROF tended to facilitate the nurses’ perceptions of the patients’ resources.

Establishing a partnership between care provider and patient (Ekman et al., Citation2011) is crucial in the concept of person-centered care, as well as having a therapeutic alliance, as described by Mead and Bower (Citation2000). In our study, the nurses stressed the importance of developing a relationship with the patient as a basis for patient-participation and shared decision-making. Although the relationship could be challenged when revealing undesirable information or adverse events, it was mostly protected by the alliance between the nurse and the patient. This finding is in line with those of Bressington, Stewart, Beer, and MacInnes (Citation2011), who concluded that the users of forensic mental health services perceived that their satisfaction with care was strongly associated with the quality of the therapeutic alliance. In addition, Eidhammer, Fluttert, and Bjørkly (Citation2014) highlight the importance of developing a good alliance between nurses and patients to achieve successful risk management.

Another finding was related to the balance between caring and necessary restriction actions, related to the risk assessment; making the patient feel well-informed and able to participate, and at the same time denying their requests, e.g., permission to leave the premises. This importance of relationship is confirmed by Mezey et al. (Citation2010), who found that feelings of being respected, valued and being cared-for emerged as being crucial factors for recovery. This mirrors the dual mission of forensic psychiatric treatment to restore mental health and to rehabilitate the patients towards discharge, and at the same time consider the aspects that may concern public safety (Adshead, Citation2014).

Team-based care, that which includes the patient, is emphasized as being important in relation to person-centeredness and recovery (Hansson et al., Citation2016) to be able to respond to the individual person’s different kinds of needs and life goals (Brummel-Smith, Butler, & Frieder, Citation2016). In our study, the nurses sometimes had to act as messengers of decisions and arguments, which were obstructed by the nurses’ alienation in respect to risk assessments. The importance of teamwork has been emphasized by Coffey and Jenkins (Citation2002), as well as by Doyle and Dolan (Citation2002), as they describe the mental health nurse as “a major source of clinical information that needs to be considered by the nurse and the team as a whole when assessing risks” (Doyle & Dolan, Citation2002, p. 650).

According to our study, the risk assessments clarified the nurses’ role within the inter-professional teamwork. In addition, the risk management plan facilitated the follow-up of the caring actions taken based on the risk assessment, which made it easier to talk to the patient about risk behavior. Woods (Citation2013) emphasized the importance of linking risk assessments to risk management plans to be able to evaluate and re-evaluate the assessment by following up the management plan.

The concept of agreement was also shown to support nurses’ participation in the risk assessment, and promoted their feeling of being “part of the team.” They were able to represent their specific area of expertise and increased their ability to manage risks in care situations. Conversely, when they did not take part, the nurses tended to experience a feeling that the assessments were less important. Similarly, Raven (Citation1999) reported the benefits of managing risk assessment and risk management in the team, leading to feelings of support and value, but also of shared responsibilities among the professionals.

Limitations

The deductive approach provided the opportunity to explore whether an expected pattern, such as the person-centered care approach, could be detected in the focus groups with the nurses about their experiences of risk assessments. It could be argued that forcing data into predefined categories instead of searching for patterns according to the inductive approach is a potential limitation. However, we found that by using the central principles of person-centeredness as a matrix in the deductive analysis, we were able to see whether there was a relationship between the nurses’ reflections on caring on more general circumstances and the principles of person-centeredness in particular (Babbie, Citation2010). The pre-understanding of the first researcher’s former experience of mental health nursing means that she is positively familiar with the context, but this might also have a negative impact on the analysis due to her preconceptions. In addition, to strengthen the analysis, the participants may have been invited to offer feedback on the analysis in a form of member checking. However, to ensure the credibility and relevance of the results, the data were analyzed by two researchers, as advocated by Graneheim and Lundman (Citation2004).

Relevance for clinical practice

The present study offers new insight into the usefulness of risk assessments from the nurses’ perspective in forensic psychiatry. Furthermore, it relates the nurses’ risk assessments to a person-centered approach, detecting its central concepts in the nurses’ reasoning on care planning. The person-centeredness approach seemed to be as well integrated and suitable in forensic psychiatric care as demonstrated previously in other care contexts. However, although risk assessments are considered to be a central process in forensic psychiatric treatment, the importance of involving nurses in that process is lacking and needs to be further developed. The nurses in this study were concerned about damaging the therapeutic alliance, which has a strong clinical relevance. A suggestion to assist nurses with this dilemma would be to emphasize the importance of involving patients and family members in the process, and to stipulate this in practice and policy documents. Another strategy may be to place a more structured focus on protective factors at the management level. This may balance the impact that historical facts have on the treatment plan in a recovery-oriented organization.

The nurses in our study, located within two different forensic psychiatric clinics in separate parts of (Sweden), showed similarities in their reasoning in relation to promoting person-centeredness, irrespective of the different procedures relating to risk assessments. This makes the findings transferable for use in other forensic psychiatric settings.

Conclusion

The potential of using risk assessments to enhance the nurse-patient interaction and patients’ participation in forensic care has so far been neglected in research. This is surprising, as the adoption of a person-centered and holistic approach in care in general should include the person’s disabilities and failings as well as their strengths and resources. It is therefore reassuring that this study demonstrates that the mental health nurses in forensic psychiatry in these two settings found that the risk assessments offered an opportunity to confirm the patient as a person, to establish a trusting relationship, and to support the nursing perspective in the inter-professional team-work environment.

To enhance our knowledge and understanding of the influence and usefulness of risk assessment and risk management, further research should be encouraged in this area. Currently, the researchers are planning to conduct research with forensic psychiatric inpatients as informants, aiming to explore their experiences of risk assessments. Another research aim is to explore the attitudes of decision-makers and leaders towards the development of person-centeredness in their organizations in the development of forensic psychiatric care.

References

- Adshead, G. (2014). Three faces of justice: Competing ethical paradigms in forensic psychiatry. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 19(1), 1–12. doi:10.1111/lcrp.12021

- Bandura, A. (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior, 31(2), 143–164. doi:10.1177/1090198104263660

- Babbie, E. R. (2010). The practice of social research (12th ed.). Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning.

- Bressington, D., Stewart, B., Beer, D., & MacInnes, D. (2011). Levels of service user satisfaction in secure settings – A survey of the association between perceived social climate, perceived therapeutic relationship and satisfaction with forensic services. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48(11), 1349–1356. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.05.011

- Brummel-Smith, K., Butler, D., & Frieder, M. (2016). Person-centered care: A definition and essential elements. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64(1), 15–18.

- Coffey, M., & Jenkins, E. (2002). Power and control: Forensic community mental health nurses’ perceptions of team-working, legal sanction and compliance. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 9(5), 521–529. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2850.2002.00490.x

- de Vogel, V., de Ruiter, C., Bouman, Y., & de Vries Robbé, M. (2009). SAPROF. Guidelines for the assessment of protective factors for violence risk. (English version). Utrecht: Forum Educatief.

- de Vogel, V., de Vries Robbé, M., de Ruiter, C., & Bouman, Y. (2011). Assessing Protective Factors in Forensic Psychiatric Practice: Introducing the SAPROF. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 10(3), 171–177. doi:10.1080/14999013.2011.600230

- de Vogel, V., de Ruiter, C., Bouman, Y., & de Vries Robbé, M. (2011). SAPROF. Riktlinjer för bedömning av skyddsfaktorer mot våldsrisk (Swedish translation of the SAPROF guidelines by Märta Wallinius, Staffan Anderberg and Helena Jersak). Utrecht: Forum Educatief.

- de Vries Robbé, M., de Vogel, V., Douglas, K. S., & Nijman, H. L. I. (2015). Changes in dynamic risk and protective factors for violence during inpatient forensic psychiatric treatment predicting reductions in postdischarge community recidivism. Law and Human Behavior, 39(1), 53–61. doi:10.1037/lhb0000089

- Douglas, K. S., Hart, S. D., Webster, C. D., & Belfrage, H. (2013). HCR-20 (Version 3): Assessing s. Burnaby, BC, Canada: Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute, Simon Fraser University.

- Doyle, M., & Dolan, M. (2002). Violence risk assessment: Combining actuarial and clinical information to structure clinical judgements for the formulation and management of risk. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 9(6), 649–657. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2850.2002.00535.x

- Dudas, K., Schaufelberger, M., & Swedberg, K. (2012). Effects of person-centred care in patients with chronic heart failure: The PCC-HF study. European Heart Journal, 33(9), 1112–1119. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr306

- Dudas, K., Olsson, L.-E., Wolf, A., Swedberg, K., Taft, C., Schaufelberger, M., & Ekman, I. (2013). Uncertainty in illness among patients with chronic heart failure is less in person-centred care than in usual care. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 12(6), 521–528. doi:10.1177/1474515112472270

- Eidhammer, G., Fluttert, F., & Bjørkly, S. (2014). User involvement in structured violence risk management within forensic mental health facilities – A systematic literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23(19-20), 2716–2724. doi:10.1111/jocn.12571

- Ekman, I., Swedberg, K., Taft, C., Lindseth, A., Norberg, A., Brink, E., … Sunnerhagen, K. S. (2011). Person-centered care – Ready for prime time. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 10(4), 248–251. doi:10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2011.06.008

- Ekman, I., Hedman, H., Swedberg, K., & Wallengren, C. (2015). Commentary: Swedish initiative on person centred care. BMJ, 350, h160. doi:10.1136/bmj.h160

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- Godin, P. (2004). You don’t tick boxes on a form’: A study of how community mental health nurses assess and manage risk. Health, Risk & Society, 6(4), 347–360. doi:10.1080/13698570412331323234

- Gustafsson, E., Holm, M., & Flensner, G. (2012). Rehabilitation between institutional and non-institutional forensic psychiatric care: Important influences on the transition process. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19(8), 729–737. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01852.x

- Hansson, E., Ekman, I., Swedberg, K., Wolf, A., Dudas, K., Ehlers, L., & Olsson, L.-E. (2016). Person-centred care for patients with chronic heart failure – A cost-utility analysis. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 15(4), 276–284. doi:10.1177/1474515114567035

- Hinsby, K., & Baker, M. (2004). Patient and nurse accounts of violent incidents in a Medium Secure Unit. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 11(3), 341–347. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2004.00736.x

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

- Kitzinger, J. (1995). Qualitative research – Introducing focus groups. BMJ, 311(7000), 299–302. doi:10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299

- Leplege, A., Gzil, F., Cammelli, M., Lefeve, C., Pachoud, B., & Ville, I. (2007). Person-centredness: Conceptual and historical perspectives. Disability and Rehabilitation, 29(20-21), 1555–1565. doi:10.1080/09638280701618661

- Livingston, J. D., Nijdam-Jones, A., & Brink, J. (2012). A tale of two cultures: Examining patient-centered care in a forensic mental health hospital. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 23(3), 345–360. doi:10.1080/14789949.2012.668214

- McCormack, B., Karlsson, B., Dewing, J., & Lerdal, A. (2010). Exploring person-centredness: A qualitative meta-synthesis of four studies. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 24(3), 620–634. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00814.x

- McCormack, B., & McCance, T. (2006). Development of a framework for person-centred nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 56(5), 472–479. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04042.x

- Mead, N., & Bower, P. (2000). Patient-centredness: A conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Social Science & Medicine, 51, 1087–1110. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00098-8

- Mezey, G. C., Kavuma, M., Turton, P., Demetriou, A., & Wright, C. (2010). Perceptions, experiences and meanings of recovery in forensic psychiatric patients. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 21(5), 683–696. doi:10.1080/14789949.2010.489953

- Munthe, C., Radovic, S., & Anckarsäter, H. (2010). Ethical issues in forensic psychiatric research on mentally disordered offenders. Bioethics, 24(1), 35–44. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2009.01773.x

- Nicholls, T. L., Brink, J., Desmarais, S. L., Webster, C. D., & Martin, M.-L. (2006). The Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START). A prospective validation study in a forensic psychiatric sample. Assessment, 13(3), 313–327. doi:10.11177/1073191106290559

- Nussbaum, M. (2011). Creating capabilities: The human development approach. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Olsson, A.-E., Hansson, E., & Ekman, I. (2016). Evaluation of person-centred care after hip replacement-A controlled before and after study on the effects of fear of movement and self-efficacy compared to standard care. BMC Nursing, 15(1), 53. doi:10.1186/s12912-016-0173-3

- Olsson, H., & Schön, U.-K. (2016). Reducing violence in forensic care – How does it resemble the domains of a recovery-oriented care?. Journal of Mental Health, 25(6), 506–511. doi:10.3109/09638237.2016.1139075

- Peplau, H. E. (1997). Peplau’s theory of interpersonal relations. Nursing Science Quarterly, 10(4), 162–167. doi:10.1177/089431849701000407

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2017). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (10 ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkin.

- Radovic, S., & Höglund, P. (2014). Explanations for violent behaviour – An interview study among forensic in-patients. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 37(2), 142–148. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2013.11.011

- Rask, M., & Levander, S. (2001). Interventions in the nurse-patient relationship in forensic psychiatric nursing care: A Swedish survey. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 8(4), 323–333. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2850.2001.00395.x

- Raven, J. (1999). Managing the unmanageable: Risk assessment and risk management in contemporary professional practice. Journal of Nursing Management, 7, 201–206. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2834.1999.00131.x

- Robeyns, I. (2006). The capability approach in practice. Journal of Political Philosophy, 14(3), 351–376. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9760.2006.00263.x

- Slater, L. (2006). Person-centredness: A concept analysis. Contemporary Nurse, 23(1), 135–144. doi:10.5172/conu.2006.23.1.135

- Urheim, R., Rypdal, K., Palmstierna, T., & Mykletun, A. (2011). Patient autonomy versus risk management: A case study of change in a high security forensic psychiatric ward. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 10(1), 41–51. doi:10.1080/14999013.2010.550983

- Webster, C. D., Martin, M.-L., Brink, J., Nicholls, T. L., & Desmarais, S. L. (2009). Manual for the Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START). Version 1.1. Hamilton, ON: Forensic Psychiatric Services Commission.

- Woods, P. (2013). Risk assessment and management approaches on mental health units. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 20, 807–813. doi:10.1111/jpm.12022

- World Medical Association. (2013). WMA declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Retrieved from: https://www.wma.net/what-we-do/medical-ethics/declaration-of-helsinki/