Abstract

A pragmatic solution for the provision of care for prisoners with serious mental illness, who are often subject to delays in hospital transfer, is the creation of specialist prison units. This paper analyses the development of a prison unit in England for prisoners with ‘serious mental illness’. The unit was developed within over-lapping health and justice contexts, including expectations, pressures and priorities, which impacted on the outcomes expected and achieved. The methodology included attendance at Steering group meetings, analysis of a minimum dataset, and interviews with key stakeholders. A number of key sites of contestation are analyzed including: admission criteria; aims; activities; staffing; the physical environment; and discharge.

Introduction

The North East of England prison mental health unit (entitled the ‘Integrated Support Unit’ and hereafter the ISU) opened in October 2017. It represents a unique development across the prison system in England and Wales. The ISU provides a service for male remand and sentenced prisoners (adult and young offenders) with serious or severe mental illnessFootnote1 (SMI) across the region (excluding high security prisoners based upon level of security). It is located on one wing within a North East Reception Prison (this prison experienced a major change of function in 2017 to become the first ‘Reception Prison’ under the Transforming Rehabilitation agenda: Ministry of Justice, Citation2013; HM Inspectorate of Prisons,Footnote2 2017; IMB, 2018), and has the capacity to take 11 patients (single cell), plus two prisoner peer workers (sharing a cell). It is staffed by mental health staff Monday-Friday 8am-8pm and Saturday-Sunday 8am-4pm; and prison officers 24/7 and represents a significant collaboration between a North East of England NHS Mental Health Foundation Trust (hereafter the NE-MH Trust) and the North East Prison Service. The development is funded by the Northern Region Offender Health Commissioner, NHS England.

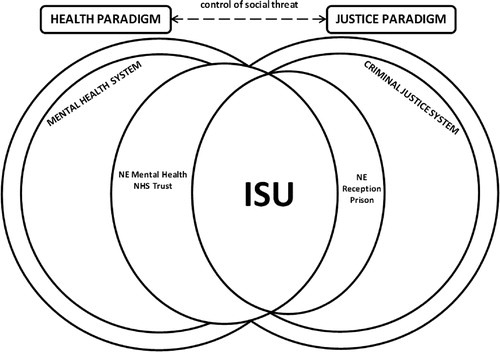

This article is based on findings from Phase 1 of a two-phase realist-informed research project, where the difference an intervention makes for those involved is understood and explained within its particular context (Pawson & Tilley, Citation1997). Phase 1 aimed to support development and delivery of the ISU.Footnote3 The research project is divided into four parts: Process Review; Staffing; the Minimum Dataset; and the Physical Environment. This article analyses the findings of this first phase review of process and provides an understanding of the context(s) within which the ISU, as an intervention, generates particular outcomes for particular prisoners. The ISU as a micro-level initiative exists and operates within the UK’s multi-scalar systems of confinement and care (Cassidy et al., Citation2020). This means that impact is both complex and emergent (Byrne, Citation2005, Citation2013; Williams & Dyer, Citation2017). The ISU, therefore, needs to be explored in the context of the supra-level health and justice paradigms, the macro-level healthcare and criminal justice systems, and the meso-level NE-MH Trust and the North East Reception Prison. The article begins with a review of the wider context – the prevalence of serious mental illness within the prison population and the challenges this presents. This is followed by a summary of national policy and practice, before discussion of existing research exploring specialist prison units. The rest of the paper is then dedicated to the process review of the unit, which following an outline of the methodology and description of the setting and population, focuses on six key themes - the unit’s purpose and aims, admission criteria, interventions and activity, transfer or discharge pathways, staffing, and the physical environment.

Background

Prisoners with serious mental illness: prevalence and challenges

Within social control debates including ‘criminalisation or medicalisation’ and the ‘mental health, welfare and tutelage’ complex, Brooker and Ullmann (Citation2008) argue that prison has become a ‘catch-all’ social and mental healthcare service, and a breeding ground for poor mental health. There has been growing recognition of the scale of mental health need in prisons in western countries (Daniel, Citation2007; Fazel et al., Citation2017), and notably in the USA. Lamb and Weinberger (Citation2005) comment upon a ‘profound paradigm or model shift in the care of persons with severe mental illness’, where psychiatric inpatient care in the USA is now provided in jails and prisons. Ford (Citation2015), writing of Cook County jail in Chicago, reports that a third of those incarcerated suffer psychological disorders, intimating that the country’s largest psychiatric institution is a jail.

In England and Wales, the prevalence of mental health problems amongst prisoners is much higher than that found within the general population (Brooker & Gojkovic, Citation2009). In a seminal psychiatric morbidity study in prisoners conducted on behalf of the Department of Health, Singleton and colleagues identified that over 90% of the current prison population had some type of diagnosable mental illness, personality disorder and/or substance misuse problem (Singleton et al., Citation1998). Bebbington et al. (Citation2017) found that of their sample of prisoners, 12% met criteria for psychosis; 53.8% for depressive disorders; 26.8% for anxiety disorders; 33.1% were dependent on alcohol and 57.1% on illegal drugs; 34.2% had some form of personality disorder; and 69.1% had two disorders or more. In the year before imprisonment, 25.3% had used mental health services. According to the Prison Reform Trust (Citation2018) over 16% of men said they had received treatment for a mental health problem in the year before custody, and 15% of men in prison reported symptoms indicative of psychosis (compared with 4% of the general public). The House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts (Citation2017) identified record numbers of suicides and incidents of self-harm in English prisons. In 2016–17 the prison population stood at 84,674; there were 120 self-inflicted deaths and 40,161 incidents of self-harm in prisons in England and Wales (see also Towl & Crighton, Citation2017).

Mentally ill prisoners pose challenges to the organization and delivery of appropriate healthcare within the prison setting, and more widely in the health economy (Cassidy et al., Citation2020; Crichton & Nathan, 2015; Walsh & Freshwater, Citation2009). At the same time, a number of contextual issues have compounded the problems in meeting such high levels of complex need. For example, between 1997 and 2007 prisoner numbers increased by 30% but prison officer numbers failed to keep pace with this growth in the prison population (House of Commons Justice Committee, Citation2009).Footnote4 For those prisoners requiring transfer to a psychiatric hospital, there is a shortage of both high and medium security beds in the NHS – with only 24 transfers from a prison to a high security bed in 2013, and a correspondingly high waiting list for ‘medium secure’ beds (Sloan & Allison, Citation2014).

National policy and practice

Prisoners in England and Wales can be transferred to a secure hospital under powers in the Mental Health Act, Citation1983 (as amended in 2007) when mental health needs require inpatient care, and the government’s target is that prisoners should wait no longer than 14 days for transfer (Department of Health, Citation2011). Yet, in 2016–2017, 24% of transfers took longer than 14 days (House of Commons Library, Citation2018; Parliamentary Questions, Citation2017).

There is a range of literature highlighting the issues impacting upon the timely transfer of prisoners to psychiatric hospital (for example: Coid, Citation1988; Grounds, Citation1991; Dell et al., Citation1993; Robertson et al., Citation1994; Hargreaves, Citation1997; Isherwood & Parrott, Citation2002; McKenzie & Sales, Citation2008; Shaw et al., Citation2008; Bradley, Citation2009; Sharpe et al., Citation2016), many of which are both long-standing and ongoing. Problems reported by these publications include: breakdown in communication; administrative difficulties; lack of availability of beds at appropriate levels of secure care; delays in establishing the responsible commissioner; security; diagnostic and financial disputes; lack of awareness of procedures around transfers; differing organizational cultures; and negative attitudes toward and perceptions of mentally disordered offenders.

Delays in transfer increase reliance on prisons to care for and manage those with severe mental disorders, potentially resulting in adverse events including suicide and self-harm amongst waiting prisoners, and their location in prison Segregation Units (Brooke et al., Citation1996; Coid et al., Citation2006; Rutherford & Taylor, Citation2004; Skegg & Cox, Citation1991). Shaw et al. (Citation2008) also reported a relatively high number of adjudications (part of the prison disciplinary system) and behavioral problems leading to heightened observation levels for this group, causing concern for prison management and prison officers in terms of the need to respond to disturbed behaviors.

Specialist prison units

One potential pragmatic response to the issues facing prisons managing prisoners with SMI is the development of specialist units. A brief review of the international literature identified publications relating to a small number of specialist prison units: one located in England (Samele et al., Citation2016) and another in Ireland (Giblin et al., Citation2012; WHO, Citation2011), both of which admit prisoners with physical and mental health problems; two in the USA, which admit prisoners with mental health problems only (Cloyes, Citation2007; Kupers et al., Citation2009; O’Connor et al., Citation2002); and one in the Netherlands, which admits male remand and sentenced prisoners with mental illness or serious behavioral disorders (Blaauw et al., Citation2000; Council of Europe, Citation1993, Citation2015; Tak, Citation2008). A number of key themes emerged from this literature. Firstly, the units aimed to provide treatment to prisoners rather than simply manage a pathway into hospital. Secondly, the admission criteria ranged from challenging behavior, repetitive self-harm, ‘mentally unwell’, to SMI – some also included the need to demonstrate motivation to engage and likelihood of benefit. Thirdly, whilst treatment or interventions provided were not reported for the England or Ireland units, in the US units there were specific structured approaches and treatments including an ‘Assertive Community Treatment’ approach and a ‘positive psychology’ approach, as well as psycho-education and cognitive behavior treatment (Cloyes, Citation2007; Kupers et al., Citation2009; O’Connor et al., Citation2002).

Each of the units referred to above measure their success against their specific aims and therefore outcomes depended on what each set out to achieve. Consequently, each was able to report some success (with the exception of the unit in England, which did not report).

The differing challenges reported by each unit were also dependent on these aims. However, some of these were relevant to the development of the ISU, including establishing clear admission criteria, intra and inter-agency staff issues and conflicts, hiring a strong manager with both clinical and administrative experience to lead and direct the programme, delays along the pathway especially discharge and transfer, the cost of running the unit, and the physical environment because units were not purpose built.

The process review of the ISU

The process review of the ISU examined the processes and procedures, issues and debates involved with the development and initial delivery of the ISU in order to understand the multiple and overlapping contexts within which particular causal mechanisms leading to particular outcome configurations may be uncovered and understood (Dalkin et al., Citation2015; Manzano, Citation2016; Pawson, Citation2013; Pawson & Manzano-Santaella, Citation2012; Pawson & Tilley, Citation1997, Citation2004; Tilley, Citation2000).

Methodology and methods

The methodology included developing a deep understanding of the ISU and the contexts within which it began to operate. Data collected included was both qualitative (notes taken during Steering Group meetings, meeting minutes, documents, and semi-structured interviews) and quantitative (ISU minimum dataset). Data analysis included iterative thematic analysis to identify themes and sub-themes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013, Citation2016; Nowell et al., Citation2017), and descriptive statistics and frequency distributions to confirm and provide additional context within which to interpret themes.

Qualitative information was collected over 24 months (November 2016-November 2018) including the manual recording of information during attendance at 13 Steering Group meetingsFootnote5, Steering Group meeting minutes, and thirty-five documents produced during the development phase of the ISU, which were presented to the Steering Group.

A number of key issues began to emerge during Steering Group meetings, and were repeatedly discussed and returned to regardless of the formal agenda. These issues were manually noted by the researcher and cross-checked during subsequent meetings. During data analysis meeting notes, formal minutes and documents presented to the Steering Group were manually coded for potential themes using the first of the broad set of systematic steps outlined by Lorelli et al. (2017) i.e. familiarity with the data, generating initial codes, and the search for themes. These potential themes and related sub-themes were further explored during 16 semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders (a mix of Steering Group members and others identified as key to understanding the ISU development and initial delivery) including the Independent Monitoring Board, Prison Senior Management, Academic Experts, ISU based Prisoner Cleaners, Northern Region Offender Health Commissioners, senior managers in the NE-MH Trust, Forensic Psychiatric Hospital Inpatient managers, NE-MH Trust Prison Mental Health Teams, the ISU Prison Officer Team and the ISU Mental Health Team. Information during interviews was manually recorded and subsequently coded in order to review, refine and confirm final themes and sub-themes as outlined in Lorelli et al, (2017) final steps, i.e. reviewing themes, and defining and naming themes.

An anonymised version of the ISU Minimum Dataset (MDS), from October 2017 to April 2018 (inclusive), was made available to the research team for analysis. The MDS is a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet developed specifically and in collaboration with ISU staff and managers to record data for administrative and research purposes. The aims are to capture key prisoner characteristics, assist the ISU to demonstrate interventions delivered to prisoners on the Unit, gather data to illustrate any changes in ISU prisoners’ mental health status and general level of functioning during their time on the Unit, capture contractual data required by NE-MH Trust, to provide data to help the research team to identify successes and challenges, and to be as practical and speedy to complete as possible. It contains 83 categories spread across six domains including criminal justice and socio-demographic, referral, referral outcome, admission, ISU activity, and transfer information. The MDS is completed by ISU staff for every prisoner referred to the Unit. Completion requires staff to either select from a list of pre-defined responses, or enter text or numbers in a standardized format for each category. Descriptive statistics and frequency distribution analyses were undertaken in order to provide additional context within which to understand the themes and sub-themes identified.

Ethics approval was granted by HM Prisons and Probation Service (27/11/2017, Research project 2017 - 260).

Results

It was clear from the outset that the development of the ISU was a complex undertaking. The ISU would be unique across the prison estate in England and Wales, consequently no ‘blueprint’ or specific previous learning existed (existing examples described earlier in this paper are drawn from other countries with differential contexts, and the English prison unit is both led by primary care and admits prisoners with physical and mental health problems). In addition, the development required two separate systems (justice and health) to collaborate in order to co-produce a solution to an identified problem. All those involved with the development of the ISU agreed on this ‘problem’, i.e. there were too many severely mentally unwell prisoners waiting long periods of time for transfer to hospital, but the ‘solution’ to this problem was the focus of some debate. The following sections outline the ISU setting, and results from analysis of the MDS and the thematic findings from the research exploring the development and initial delivery of the ISU ‘solution’.

The ISU setting

The background to the initial development of the ISU is described in a paper submitted to a North of England Strategic Partnership Board by the NE-MH Trust in 2016. This paper presented an overview of the current issues relating to delayed mental health transfers across the North East region’s prisons and perspectives from key stakeholders including senior managers from both health and prison services. The main issues reported in this paper (NE-MH Trust, Citation2016) focused on questions around criminal justice sentencing and the role of Criminal Justice Liaison and Diversion services. A number of conclusions were reported including: prisons should not be considered as places of safety; the current system does not support the care of SMI prisoners in prison; there is a lack of available secure mental health beds nationally, which prevents effective and timely transfer of prisoners; there is no equivalence of care for SMI people in prison as compared to those within the community; and there is a need to consider new ways of working, of enhancing MH services in prison to minimize risk and improve care. The recommendation to the North of England Strategic Partnership Board specified:

This report recommends that [the NE-MH Trust] with key stakeholders, develop a proposal for a new model of care to improve the assessment, care and treatment options for those prisoners presenting with serious mental illness within [a North East Prison]. It will also consider access to short term local secure mental health beds within clearly managed and audited pathways and will clearly outline key risks and mitigation of risk. (NE-MH Trust, Citation2016, p.5)

The issues and recommendation described in this paper (NE-MH Trust, Citation2016) provided the impetus for the development of ISU. The ISU began to accept referrals in October 2017. It operates within one wing in one Reception Prison in the North East of England. There are 12 cells, 11 for patients, one to a cell, and one cell for two prisoners specifically selected to work on the unit as cleaners and peer workers.

Three mental health staffing models were considered including: a 24 hour/7 days per week mental health service; a core prison weekday delivery of mental health service with no weekend cover; and the one finally selected which includes delivery of mental health services Monday-Friday (08.00 hrs-20.00 hrs) and on a weekend (08.00 hrs-16.00 hrs).

Staffing includes a Unit Manager with learning disability expertiseFootnote6, three psychiatric nurse Clinical Team Leads, one Support Worker (plus one currently advertised), 0.5 of a Speech and Language Therapist, 0.2 of a Consultant Psychiatrist, and 2-3 Prison Officers. The number and ‘dedicated statusFootnote7’ of prison officers was one of the main contentions arising from the process review and is discussed in more detail below. In one document which provides an outline of the aims of the ISU and possible patient pathways and limitations, it states that two ‘dedicated’ officers will be attached to the unit:

It is proposed that this service will provide a dedicated place within the prison to care and treat men presenting with serious mental illness. This service will not prevent delays in appropriate transfer to mental health beds and the model supports short term transfer to [NE Mental Health NHS Trust] low secure beds on [name of ward] for a maximum of 16 weeks. The service will be supported by two dedicated prison officers. (NE-MH Trust, Citation2017a, p.1)

The admission criteria evolved over time, initially including those with a diagnosis of Personality Disorder, the most recent criteria makes no specific mention of Personality Disorder:

[Access criteria includes] acute and/or severe and complex mental health problem that requires an enhanced level of input from specialist mental health professionals that cannot be provided elsewhere within the prison. Such patients may lack capacity, insight and refuse medical treatment or disengage from mental health services in prison. This is a ‘high risk’ group of patients that can lead to devastating consequences including an exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms/behaviours, self-neglect, violence against others, and increased self-harm and suicide. (NE-MH Trust, Citation2017b, p.2)

Multiple documents describe or model the potential ‘pathway’ into, through and out of the ISU, including a ‘patient pathway flow diagram’ (NE-MH Trust, Citation2017c). The Patient Pathway Flow Diagram does reflect some of the complexity expected. It includes multiple potential pathways or bifurcations where a patient may go down one path or another depending on decisions made by the professionals involved, which could then lead to a variety of outcome locations including transfer out of prison to secure hospital inpatient services, transfer back onto a ‘normal’ prison residential wing with Prison Mental Health Team follow-up, discharge from prison mental health services, and release from prison and urgent Mental Health Act assessment or community mental health service follow-up. There is also some suggestion of feedback loops or iterations between the review of ISU interventions and treatments and the delivery of interventions and treatments.

The potential prisoner experience including interventions and treatments available, are also modeled in a ‘patient journey document’ (NE-MH Trust, Citation2017d). Details include allocation of a key worker and a jointly agreed individual care and treatment plan which might include health promotion and education; structured one-to-one sessions; other clinics for example primary care GP or substance misuse; medication review; group work such as Understanding Emotions or Hearing Voices; and activities including Occupational Therapy; movies; quizzes & crafts; exercise; and reading and newspapers.

In terms of the wider (meso) context referred to in the original Strategic Partnership Board paper (NE-MH Trust, Citation2016) no mention is made of challenging the use of prisons as a place of safety for those with SMI or the reasons why prison is still being used despite investment in Criminal Justice Liaison and Diversion schemes. No additional hospital beds are being proposed and the MH Enhanced Service paper (NE-MH Trust, Citation2017e) acknowledges that this service will not prevent delays in transfer to hospital. The development of the ISU is an acknowledgment that the current system does not support care of SMI prisoners and offers a potentially new way of working. Whether this provides equivalent care compared with those in the community or resolves the problems around delays in transfer are issues some respondents commented upon during the process review interviews.

Results of the MDS analysis

The ISU began operating in October 2017. A total of 53 referrals were received up to and including April 2018. All referrals were for male prisoners, with an average age of 34 years (youngest 18 years and oldest 61 years). The majority, 38 (71.7%), were classified as White-British. Thirty-One (58.5%) referrals were remand prisoners, 20 (37.7%) were sentenced prisoners and 2 (3.8%) were immigration detainees. Prisoners were imprisoned for a wide range of offenses or alleged offenses with ‘violence against the person’, ‘sexual offenses’ and ‘other’ being the most common offenses (each equating to 15.1% of referrals). The majority, 51 (96.2%), were referred from one of the North-East region prisons and housed on main location at the time of referral (n-34, 66.6%). Of those remaining, 10 (19.6%) were on a Vulnerable Prisoner wing and 5 (9.8%) were in a Segregation Unit. A range of working diagnoses were given by referring organizations, with ‘Schizophrenia or other Delusional Disorder’ being the most common (n-30, 56.6%). Of the 53 referrals made, 48 (90.6%) were accepted for admission. The reasons for the rejection of five referrals included a lack of engagement or willingness to engage with treatment, lack of beds available on the ISU and for one, transfer to a psychiatric hospital inpatient bed.

Diagnosis for those admitted to the ISU is made by a Consultant Psychiatrist and discussed at a weekly meeting with other members of staff on the unit. The most common primary diagnosis category recorded in the MDS for the 48 people admitted was ‘schizophrenia or other delusional disorder’ (n-25, 52.1%), slightly lower than the working diagnoses given by the referring prisons. The remaining diagnoses were spread between the MDS categories ‘Anxiety/Phobia/Panic Disorder/OCD/PTSD’, Bipolar Affective Disorder, Depressive Illness, Personality Disorder and Learning Disability. Co-morbid substance misuse was relatively common. Twenty patients (41.7%) had identified or suspected alcohol misuse, 17 (35.4%) psychoactive substance misuse, 13 (27.1%) non-prescription drug misuse, and 8 (16.7%) misuse of prescribed medication.

At the point of analysis 37 patients (77.1%) had been prescribed psychiatric medication while on the ISU, of which 29 (78.4%) were fully compliant, 6 (16.2%) were partially compliant and 2 (5.4%) were minimally or not at all compliant. The majority of patients, 37 (77.1%) had engaged fully or partially in formal therapeutic group activities and 39 (81.3%) in the wider social regime. Thirty seven patients had been discharged from the ISU. The average length of stay was 43 days (longest 137 days and the shortest 1 day). Discharge included 17 (45.9%) patients transferred back into the prison system and 15 (40.5%) to a psychiatric hospital, 4 (10.8%) released from custody and 1 (2.7%) patient died by suicide.

Results of the identification of themes and Sub-themes

The following issues were coded during initial analysis and refined and confirmed during interviews with 16 key stakeholders. The six final interlinked themes and sub-themes themes included:

Theme: The purpose and aims of the ISU – Sub-theme: what will ‘success’ look like;

Theme: Admission criteria – Sub-themes: who is or should the ISU be focusing on, who is not or should not be admitted including exclusion criteria, and what are the facilitators and barriers to referral and admission;

Theme: Interventions and activity on the ISU – Sub-themes: what formal, clinical interventions can and should be available, what a wider therapeutic environment and regime can and should be provided;

Theme: Transfer or discharge pathways out of the ISU – Sub-themes: what should the outcome of admission be, where should people end up, and what are the facilitators and barriers to transfer and discharge;

Theme: ISU staffing – Sub-themes: how many and who is and should be working on or into the unit and why, and current issues and pressures on and around staffing;

Theme: The physical environment – Sub-themes: impact on patients and staff, and what improvements or changes have and have not been possible.

These six themes and sub-themes are discussed below in more detail, along with relevant contextual data from the MDS analysis and the review of documents.

?>The purpose and aims of the ISU

Thirty-five documents relating to the development phase of the ISU were presented for discussion to the Steering Group, including updates and new iterations. In particular, various versions of the purpose of the ISU including aims and objectives are described in different documents. Some related to ‘pathway’, as in the document produced by the NHS Mental Health Trust:

[To] design a service delivery model and pathway to support the transfer and remission of mentally disordered offenders to and from secure hospitals. (NE-MH Trust, Citation2017f, p.4);

and others to ‘recovery’ and treatment, as in the following document:

The purpose of the unit is to help people who need extra support by assessing and treating their mental health needs. (NE-MH Trust, Citation2017g, p.1)

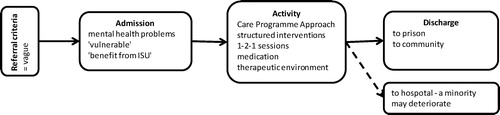

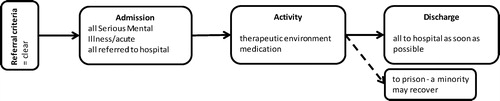

The variation in statements about ISU aims – should the main aim be to support prisoners during the hospital transfer process (see ),or to treat prisoners in order that they become well enough to be transferred back to the general prison population (see )

Figure 1. PATHWAY: Aim to support/manage people in a safe environment and stabilize prior to hospital transfer.

– will impact on all areas of ISU practice and process including admission criteria, activity on the unit and regime, staffing, the physical environment, and outcomes including discharge and transfer.

Issues concerning the aims of a prison based unit for SMI prisoners are highlighted in the review of evidence above, and were also discussed during the stakeholder interviews. In relation to understanding the aim(s) and therefore the purpose or focus of the ISU and what ‘success’ would look like, comments from those interviewed underlined the complexities: should the aim be ‘pathway’ (a shorthand for supporting prisoners with SMI referred to hospital); or should it be ‘recovery’ (a shorthand for treating prisoners with mental health problems until they are well enough to be transferred back into prison). The majority of those interviewed suggested that ‘success’ for the ISU would mean achieving both of these outcomes, for example:

It should provide interim support for people with complex needs… so a bit of both treatment and pathway. (interview Prison Mental Health Team staff-3, May 2018).

Success would be patients in an environment where they feel safe and where they can be monitored and treated, and experience a smooth pathway to hospital, or back onto a prison wing. (interview NHS Trust Senior Management, Feb., 2018).

I suppose it has different functions…it’s not a ward as such, but it’s a little bit more of a protective environment for people who are perhaps a bit more vulnerable because of their mental health needs. So perhaps people who are acutely ill who need a period of observation. That’s skilled observation rather than just by prison officers. Or people who are waiting to be transferred out to hospital. So it’s a little bit more of an appropriate environment for those type of people. (interview Prison Mental Health Team staff-1, May 2018).

Some of those interviewed referred to the ISU as a ‘half-way house’, for example halfway between a hospital ward and a Community Mental Health Team, or a stepping-stone halfway between prison and hospital. Although all stressed it is not a hospital and should not become an alternative to hospital admission for those that require this:

If a patient has been identified as needing a secure bed then they should have access to that secure bed within a reasonable amount of time, not held at another [prison] location such as the ISU. It’s unreasonable to think that a prison – or unit within a prison – is able to deliver care and treatment as effectively as a secure unit. (interview Forensic Psychiatric Hospital Inpatient manager, Jan. 2018)

Of the thirty seven patients discharged from the ISU the most common destination was transfer back into the prison system (45.9%), followed by transfer to a psychiatric hospital (40.5%).

Evidence, including admission criteria (discussed below) and service aims, suggests that prisoners being targeted by the ISU are not all the same and are not “a single, easily identifiable group” (Peay Citation1994). The meso-level ISU context must therefore be sufficiently flexible to accommodate a broad variety of people and at least three potential outcome destinations (hospital, prison, or release). The following section explores the theme of admission criteria in more detail.

?>Admission criteria

Of the patients referred to the ISU from October 2017 to April 2018, 58.5% were remand prisoners and ‘Schizophrenia or other Delusional Disorder’ was the most common working diagnosis. 90.6% of the referred patients were accepted for admission, with reasons for rejection including lack of willingness to engage with treatment and lack of beds available on the ISU.

Comments from those interviewed about who the ISU should focus on admitting to the unit ranged between the need to target prisoners with psychosis waiting for an acute hospital bed in order to offer a meaningful regime for severely mentally unwell people, to the need for an inclusive admission criterion whereby each referral would be assessed on a case by case basis with decisions made by the multidisciplinary ISU team dependant on the needs of the individual and potential impact of the ISU service rather than diagnosis or possible transfer destination.

Descriptions in policy documents about who the ISU will focus on have varied: from prisoners with ‘serious mental illness’ (NE-MH Trust, Citation2016, p. 4-5); to ‘acute and/or severe and complex mental health needs’ (NE-MH Trust, Citation2017f, p.4). During interview with a member of the ISU team, responsible for admissions in practice, criteria had evolved to include:

[A]n identified Mental Health problem – Serious Mental Illness, Learning Disability, Autism, and Personality Disorder….[and in one example provided, could include those who are]… emotionally unstable with no serious mental illness noted by the referrer…. (interview ISU Mental Health Team, April 2018).

Issues around admission criteria are important and along with service aims and objectives discussed above will impact on the activities and outcomes experienced by those admitted and on the longer-term success and operation of the unit:

…I have had experience of visiting ISU-type units and finding them populated to some extent by prisoners who are difficult to manage such as bullies, bullied or exhibiting behaviour that cannot be managed on a wing. They are not necessarily mentally ill. (interview Academic Expert, Feb. 2018)

I am concerned that the ISU continues as this model and does not become a Seg by default [prison Segregation Units, often referred to as ‘the Seg’, are used as a disciplinary tool or for those who are ‘at risk’ from others or from themselves]… nurses and Prison Officers could move on and things change very quickly in the prisons. (interview Prison Mental Health Team staff-1, May 2018).

Current ISU admission criteria appear vague. While as noted by the ISU Mental Health Team during a research visit to the unit, this may help with management of referrals, it is not clear what those responsible for making referrals understand by the admission criteria. During interview Prison Mental Health Team staff in other prisons (expected to be the main source of referrals) argued they did have some understanding of the aims and referral criteria, and all those interviewed had made successful referrals, for example:

The referral process is very helpful, with the mailbox… I had an instant response. The ISU staff knew the patient and gave instant feedback… very helpful, smooth. The patient was transferred within the hour…. I am confident I could ring for a chat about referrals. (interview Prison Mental Health Team staff-3, May 2018).

[ISU staff member name] definitely came to visit… we were also sent the referral pathway and a load of other information by email… (interview Prison Mental Health Team staff-2, May 2018).

However, this interviewee also asked during interview for an explanation of the referral criteria, which does suggest some lack of clarity. Some of those interviewed were also unclear if the ISU staff had visited their prison to talk with Prison Mental Health Team staff about the ISU aims and objectives, referral criteria and process. Others were waiting for information, such as patient information leaflets to pass on to those prisoners referred and waiting for admission to the ISU. Given the central role Prison Mental Health Teams were expected to play in relation to referrals, staff talked about the importance of developing relationships between Prison Mental Health Teams and ISU staff. A small number of Prison Mental Health Team staff had visited the ISU to meet staff and better understand the unit, which they described as very helpful.

Possible evidence relating to the lack of understanding of referral criteria and process became apparent with the smaller than expected number of referrals received by the ISU during the initial months of operation October 2017-April 2018. Given the reasons why the ISU was established (including the high numbers of prisoners reported across the region waiting long periods for transfer to hospital) it was unclear why the ISU had not been overwhelmed with referrals. During October 2017-April 2018 the ISU had admitted 48 patients (from 53 referrals) and reported a consistently minimal waiting list of between 4-5 prisoners at any one time. Prison Mental Health Team staff were asked about this during interview. Some suggested the ISU was a relatively new service and that as it became established use would increase. However all Prison Mental Health Team staff interviewed commented they would only consider referral to the ISU if they were unable to ‘manage’ the patient within their own establishment, for example:

…so we are resilient and I do think that we manage people quite well here… In fact, where we can, we just transfer somebody [to hospital]. You know if someone has been assessed as suitable for transfer to hospital but they’re settled in this establishment and they’re doing OK here, we wouldn’t refer or transfer somebody [to the ISU] just for the sake of it. We’d keep them here because that’s more conducive to somebody’s mental wellbeing. (interview Prison Mental Health Team staff-1, May 2018).

Some talked in more detail about ‘manageable’ and ‘unmanageable’ prisoners, and the complex relationship between the Prison Segregation Unit, prison healthcare, and the ISU. In some circumstances, they argued, especially where there is a ‘risk to others’ such as ‘making weapons’ and ‘fire-setting’, and where multiple prison staff need to be present before a prisoner is ‘unlocked’, there has to be an assessment of the appropriateness of referral to the ISU despite high levels of mental health need.

Discussions about admission criteria also led some respondents to question fundamental issues to do with the admission of the mentally ill to prison, the functional interdependence of the criminal justice and mental health systems, and the need for a unit such as the ISU including:

…people with Serious Mental Illness are ending up in prison – how did [name] even get in the dock… why was the police officer not concerned’? What about the Appropriate Adult during police interview, solicitor, and role of Liaison and Diversion? (interview Northern Region Offender Health Commissioners, May 2018)

?>Interventions and activity on the ISU

Analysis of MDS data suggested that a majority of patients (n-37, 77.1%) were engaged fully or partially in ISU group activities and in the general social life of the unit (n-39, 81.3%). During the initial delivery period the ISU began to develop a regular weekday schedule including a staff and prisoner unit meeting each morning followed by housekeeping duties and cleaning cells; then gym, library and in-door gardening sessions (the small outside space available to the unit required work to make it safe and useable, which had not been carried out and was therefore not routinely accessed by patients). After lunch there were structured ‘psycho-educational’ programmes which according to staff “depended on the needs of patients” and included for example ‘Hearing Voices’ group sessions. However all prisoners were invited to attend these sessions regardless of symptomatology. The ISU health staff commented that they were not using a Care Programme Approach (CPA) framework (DH, Citation1999) which would support individualized care planning as it “does not fit with the prison environment” and a lack of access to the NE-MH Trust IT system was proving to be challenging. Psycho-educational sessions were carried out in the ground floor central communal area of the ISU, a very public, open space. A ground floor room, which it had been envisaged would be the place where group sessions would be held, had no heating and had not therefore been used for groups or therapy, with the exception of art sessions. The rooms and space available upstairs did not appear to be used at all.

Interviewees reflected on the activities and interventions on the ISU, including those that had started to happen or those that could or should be happening. The importance of a general therapeutic environment was acknowledged by all of those interviewed, including staff attitudes, relationships and interaction with patients, time out of cell, and meaningful communal and social activities – together making the unit ‘significantly different to normal prison location’:

The regime is very different on this wing. More like a hospital – time out of cell, doors unlocked most of the time… The ISU is respite from main population – staff are angels – they understand – don’t just send people to the Seg. They treat people with respect, dignity, and understanding. (interview ISU Prisoner Peer Worker 1, Jan. 2018)

There should be…opportunities for prisoners to undertake everyday tasks in a way that reduces isolation and promotes socialisation…creating a positive regime using normal, everyday activities… (interview Academic Expert, Feb. 2018).

There should be a focus on relationships, engagement, activities, therapy… (interview Prison Mental Health Team staff-2, May 2018)

They should provide things like mindfulness, acupuncture…there is good buy-in patients really enjoy it…relaxation techniques…when I visited the unit they were talking about yoga and pilates but these hadn’t started then…the art work in the end room is brilliant…expressive, starts conversations, lads don’t see it as therapy so are more likely to engage…the area in the middle of the unit is great, the lads seemed all relaxed, playing pool with officers really involved. It was relaxed and informal which you don’t get elsewhere in prisons. (interview Prison Mental Health Team -3, May 2018).

The communal lunch, where patients ate together and which had evolved dynamically to become part of the ISU’s routine, was noted by many as a positive example of this general therapeutic environment.

Structured therapeutic activity including formal treatment or intervention programmes and medication were also referred to by many of the health respondents, including the need for specific interventions such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, and Hearing Voices. Others referred to the need for input from other professions not part of or accessed by the ISU at that time, such as an Occupational Therapist, Art Therapist, Psychology and Education:

[T]hey should be doing basic cookery – they do this in hospital. They need an OT. They also have no Higher Assistant Psychologist…. I have been working in the prisons a lot of years so have a good understanding of the jails and all of the jobs and roles… and I have never made a referral to a Speech and Language Therapist… not having an OT or psychologist does not make sense… much of what they do should be driven by OT… the Speech and Language Therapist [0.5 post on the ISU] could have been used for psychology… (interview Prison Mental Health Team staff-3, May 2018).

?>Transfer or discharge pathways out of the ISU

The average length of stay for patients on the ISU was relatively brief at 43 days (median 29 days/maximum 137 days/minimum 1 day). The most common transfer destinations as described above were the North East Reception Prison and the North East Mental Health NHS Trust hospital. Those interviewed acknowledged the complexities and issues involved with the transfer and discharge process including multiple pathways, unexpected release from prison (particularly for those who had been remand into custody), and delays accessing hospital beds and community services.

The existence of a unit like the ISU can mean courts and hospitals think that there is no urgency to transfer a patient to a secure bed as the prisoner is felt to be in a therapeutic environment. (interview Academic Expert, Feb. 2018)

There is a need to think about pathways – what discharge provision and provided by whom? – we need data to measure what happens to people when discharged; what package if released into the community. (interview Independent Monitoring Board, Jan., 2018).

The ISU Mental Health Team reported that “Discharge and transfer has not been as simple as I expected.” (interview ISU Mental Health Team, April 2018). Issues described include: those discharged from the ISU back to prison can be transferred to any prison across England and Wales; planned release into the community means trying to locate a Community Mental Health Team to provide a hand-over; and unexpected release means trying to locate the Crisis Team responsible for the geographic area:

[B]ut Crisis Teams have generally been uncooperative. ISU staff are spending huge amounts of time trying to contact community teams because it is not clear who to contact and teams are being uncooperative… We are second guessing what courts will do at remand hearings. There is the added dimension of geographical issues… anywhere across the North and sometimes nationwide. If they are released from court it is very time consuming to identify community services and to create a pathway. It is causing the team quite a lot of issues at the moment. (interview ISU Mental Health Team, April 2018).

This mirrors concerns raised by some respondents during interview:

I am concerned that people might be released from ISU if on remand with nothing in place. (interview Forensic Psychiatric Hospital Inpatient manager, Jan. 2018)

?>ISU staffing

A number of interviewees queried what had happened to the initial plans to recruit an Occupational Therapist and others were more strongly critical about the lack of Occupational Therapy. During one interview an NHS Trust Senior Manager explained:

We have decided we will ‘skill mix’ the Occupational Therapy post because the men on the unit are so poorly they will benefit more from nursing input than structured Occupational Therapy interventions… (interview NHS Trust Senior Management, Feb., 2018)

Respondents asked for clarification about the role of the Speech and Language Therapist on the ISU and also discussed the need to recruit an Art Therapist, Psychologist and Social Worker:

Social Workers are especially valuable in developing relationships with community teams, and discharge plans and packages for those who are on remand on ISU and might be released at next court hearing. (interview Forensic Psychiatric Hospital Inpatient manager, Jan. 2018).

The need to include wider agencies and services such as Probation and Liaison and Diversion teams was also discussed especially in relation to planning for release into the community.

There was a lot of praise for the health and prison staff working on the ISU by respondents during interviews. There was also recognition of the potential issues around the multi-agency composition of the staff team, and multi-agency working generally, including cultural differences and the importance of team building. One respondent described the resolution of initial issues:

I can see similarities with the culture on the ISU in the early days as similar to that on the DSPD [Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorder prison units]….that there were differences between the healthcare and prison staff and a bit of ‘them and us’. However, this has quickly improved – I think this is down to the recruitment of good staff who had experience of multi-agency working and had a special interest in the ISU. (interview Prison Senior Management, Jan. 2018)

The majority of issues relating to ISU staffing discussed by respondents revolved around commitment and support from the North East Reception Prison within which the unit is based. For example during researcher attendance at Steering Group meetings and regular informal visits to the unit there was a lot of discussion about the number of prison officers that had previously been ‘promised’ by the Prison Governor. This was important as the ISU is impacted by a prison rule which states that a minimum of two officers are required on a wing in order to unlock prisoners from their cells. Three prison officers would mean that the ISU would be able to provide a full daily schedule of activity, in the event that one officer had to leave the unit to escort patients to other parts of the prison. Two officers would mean that during escorts or when only one officer is on the unit all prisoners must be locked in their cells.

The buy-in from the prison is not what I had hoped for … for example they continue to offer gym sessions to other wings during periods when there are staffing issues but are stopping ISU gym. This is because there may be 80+ on other wings while ISU has only 11, but it is still problematic…. I can tell depending who is on if ISU will lose staff and have a lock-down. [The Prison Governor] has asked for a copy of the spreadsheet we have started to keep on prison staffing and impact on the ISU. We had more lock-downs and impact on ability to run groups in March. (interview ISU Mental Health Team, April 2018).

There were also issues to do with the ‘dedicated’ status of prison officers, i.e. identified to work solely on the ISU. A number of officers had been identified or had requested specifically to work on the unit as they had a particular interest, experience and skills. However the decision was taken by senior prison managers that the ISU and Segregation Unit would ‘share’ officers. Prison managers argued this was a purposeful decision intended to have a positive impact on staff:

Seg and ISU are sharing the same staff. There was some initial concern that ISU might become an annex to the Seg but I am actually finding the opposite. The aim is to share culture from ISU across to Seg. (interview Prison Senior Management, Jan. 2018)

However others argued this is not a good idea and had not had a positive impact:

…that’s not good… the Seg. is completely different – you need completely different hats on…” (interview Prison Mental Health Team staff-2, May 2018).

The Nurses and Prison Officers are excellent…although there are dynamic changes depending on if new staff come on the ISU – some Prison Officers are more ‘discipline’ with a ‘this is my wing’ attitude. Staffing issues are due to staff coming from the Seg. This should not happen. (interview ISU Prisoner Peer Worker 1, Jan. 2018).

The Academic Expert interviewed took a different approach and challenged the need for any Prison Officers on the ISU:

Are discipline officers [Prison Officers] actually needed? Some prison in-patient units do not have discipline officers for example [HM Prison name]. Also Rampton and Ashworth [high security psychiatric hospitals] are staffed by clinicians not discipline staff. So do you need discipline staff based on the ISU all the time? (interview Academic Expert, Feb. 2018)

However it is important to understand that the ISU remains a part of the North East Reception Prison, Rampton and Asworth are able to treat people under the Mental Health Act (Citation1983, amended 2007), and the HM Prison inpatient example given had closed in 2011. Consequently the idea was dismissed by ISU staff, prison and health managers. During interview the Academic Expert also stressed that if Prison Officers are to be part of the ISU then they must be engaged in delivering the regime including healthcare activities which has staff recruitment, retention and training implications. The issue remains however that the prison staff are not ‘dedicated’ staff and the ISU is experiencing ‘lock-downs’ because of lack of the minimum required number of prison staff.

The physical environment

The North East Reception Prison within which the ISU is based was built in 1819. As a very old prison it has a number of issues in relation to the physical environment many of which cannot be changed. Before the ISU began to admit patients the research team was encouraged to provide evidence and advice about things which could be altered such as color, furnishing, and zoning and use of different spaces. All of the key stakeholders interviewed recognized the importance and impact of the physical environment, and the evidence-based improvements to the wing undertaken prior to the ISU opening and which were ongoing at the time of this research.

There were however tensions caused by budget and cost and the inability to afford some of the resources initially discussed such as furnishing and safety changes:

The ISU is gloomy – it needs more pictures to cheer it up. But overall I think it is good compared with rest of the jail, except for the lack of furnishing which was promised. (interview Independent Monitoring Board, Jan., 2018).

The furniture is ordered again now… including soft chairs and beanbags. It is now coming out of [the NE-MH Trust] budget. Heating in the large group room is still not sorted – so the room is not used. I would like to see three of the ground floor cells developed into ‘safe-cells’, but I do not see this happening. Cells still have ligature points –the prison has said this will not be changed… (interview ISU Mental Health Team, April 2018).

Are all cells anti-ligature? Given the patients they have on there they should be. (interview Prison Mental Health Team -2, May 2018).

At the time of this research a number of issues remain unresolved and a cause of frustration including: lack of heating which means the designated group room is not routinely used; lack of furniture so that the designated ‘time-out/quiet room’ is instead used as a storage space; and lack of progress with the outside space.

Conclusion

While it was not within the remit of this phase of the research to evaluate the ISU including its impact or outcomes, the emergent findings point to some tentative recommendations. The purpose of the ISU is to provide short-term treatment, observation and support for prisoners with acute and complex mental health needs until they are transferred to a psychiatric hospital or become well enough to be transferred back into the prison estate. Patients who are able and willing to consent to treatment and engage with the wider therapeutic environment that the unit offers appear more likely to do well. Challenges and opportunities for learning and development were identified in a number of areas, and reflect the issues experienced by other specialist prison units outlined earlier in this paper.

Our recommendations based on current findings include that admission procedures should ensure all potential referrers have a clear understanding of the purpose of the unit and admission criteria. To ensure the unit provides a regional resource, dialogue between unit staff and potential referrers should be regular, easy, and prompt. The staffing profile should include doctors, nurses and nursing assistants, however, consideration should be given to the inclusion of wider professions such as occupational therapists and speech and language therapists. Prison officers have been very important to the success of the ISU, particularly when selected based on their interests, skills and experience. There is a clear need for sufficient dedicated officers to be identified to work on the unit so that the regime can continue uninterrupted and without the need to use officers who would normally work elsewhere in the prison such as the Segregation Unit. Changes in prison personnel can cause substantial disruption to the therapeutic regime that has been implemented on the unit (Cassidy et al, Citation2020). This regime should be configured as a therapeutic environment, including positive relationships and interaction with patients, time out of cell, and meaningful communal and social activities. Treatment interventions should be individualized and needs lead, with group therapy being targeted. Even on a small unit, the location for interventions needs to be appropriate for individual or group sessions. The physical environment should not be overlooked as a key component of the therapeutic regime. The purpose and use of the spaces available should be planned and improvements prioritized.

In terms of planning and developing this type of unit, it is clear that commitment, budgetary responsibility, and a timetable for improvements should be agreed at the outset. Time and resource constraints mean that patient transfer and discharge planning should begin at the point of admission. Processes need to be in place for information sharing and follow-up for those transferred back into the wider prison system. Particular attention should be paid to the development of pathways for planned and unplanned prison release, including establishing links and agreements with mental health community teams and services including Crisis Teams.

The findings presented in this paper underline the complications involved in the evolution and delivery of any complex service, particularly those open to the demands of overlapping or competing contexts such as the ISU; each with their own culture, pressures and priorities ().

The ISU, which constitutes a milieu of its own, is situated within multiple contextual levels including supra-level health and justice paradigms. Some of those interviewed touched on the complex debates around the functional interdependence of the criminal justice and mental health paradigms, and the transcarceral model of social control – the shift in the control of the ‘social threat’ posed by the mentally ill between the health care system and the criminal justice system – or the ‘prisons, the new asylums’ argument (Abramson, Citation1972; Biles & Mulligan, Citation1973; Freeman & Roesch, Citation1989; Penrose, Citation1939; Torrey et al, Citation2010; Weller & Weller, Citation1988). While details in this debate are contested, for example there is no evidence to support arguments of a direct transfer of populations from hospital to prison following the closure of the asylum system in the UK (Fowles, Citation1993) or the USA (Steadman, Monahan, Duffee, Hartstone, & Robbins, Citation1984; Steadman & Morrissey, Citation1987), there is some evidence to support a broader ‘criminalisation’ hypothesis (Brinded, Grant, & Smith, Citation1995) or a ‘continuity of confinement’ argument (Raoult & Harcourt, Citation2017).

The prevalence of and challenges posed by people with mental health problems in prisons and conversely the challenges faced by prisoners with SMI at the macro-level mental health and criminal justice systems contexts is clearly evidenced by the high levels of complex needs, self-harm and suicide, pressures on prison officers, the prison regime and prison mental health services, and lack of secure psychiatric hospital beds nationally leading to delays in transfers and use of prison Segregation Units. Within this and at a local, meso-level, the NE-MH Trust and Reception Prison face additional challenges including the Mental Health Trusts secure hospital ward dedicated to the transfer of adult male prisoners has only five beds leading to high levels of demand, whilst the Reception Prison has only recently changed its role to focus on remand and short sentenced prisoners leading to high levels of prisoner turnover and a concentration of significant mental health need (HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 2018).

The ISU was developed and began operating as a consequence of but also within these contexts. What outcomes are achieved, for whom, how and why, can only be understood at the micro-level of the unit, where the expectations, pressures and priorities of the health system and the justice system at the meso-macro-supra levels are negotiated in situ.

Disclosure statement

This manuscript has not been published elsewhere and has not been submitted simultaneously for publication elsewhere.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 “Severe mental illness (SMI) refers to people with psychological problems that are often so debilitating that their ability to engage in functional and occupational activities is severely impaired.” (Public Health England, Citation2018).

2 HMIP and IMB reports are not included in the reference list to maintain the anonymity of the prison.

3 Phase 2 will evaluate the impact and outcomes of the unit.

4 There has been a recent drive to recruit new officers following prison disturbances and the publication of the White Paper, ‘Prison Safety and Reform’ (Ministry of Justice, Citation2016).

5 The aim of the Steering Group was to support the initial development and initial delivery of the ISU. Members included the Independent Monitoring Board, Prison Senior Management, Northern Region Offender Health Commissioners, senior managers in the NE-MH Trust, Forensic Psychiatric Hospital Inpatient managers, and Public Health England. The researcher was a Steering Group member providing academic knowledge and expertise.

6 The role of Unit Manager was advertised, interviewed and appointed primarily based on expertise, qualifications and experience in management (including in this instance qualifications in ‘coaching’).

7 I.e. Prison Officers who would work solely on the ISU and who would not work elsewhere in the prison.

References

- Abramson, M. F. (1972). The criminalisation of mentally disordered behaviour: possible side effects of a new mental health law. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 23, 101–105.

- Bebbington, P., Jakobowitz, S., McKenzie, N., Killaspy, H., Iveson, R., Duffield, G., & Kerr, M. (2017). Assessing needs for psychiatric treatment in prisoners: 1. Prevalence of disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(2), 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1311-7

- Biles, D., & Mulligan, G. (1973). Mad or Bad? - The Enduring Dilemma. The British Journal of Criminology, 13(3), 275–279. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a046465

- Blaauw, E., Roesch, R., & Kerkhof, A. (2000). Mental disorders in European prison systems. Arrangements for mentally disordered prisoners in the prison systems of 13 European countries. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 23(5-6), 649–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0160-2527(00)00050-9

- Bradley, K. (2009). Lord Bradley’s review of people with mental health problems or learning disabilities in the criminal justice system. House of Lords.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2016). (Mis)conceptualising themes, thematic analysis, and other problems with Fugard and Potts’ (2015) sample-size tool for thematic analysis. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 19(6), 739–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1195588

- Brinded, P. M. J., Grant, F. E., & Smith, J. E. (1995). The spectre of criminalisation: Remand admissions to the forensic psychiatric institute; British Columbia, 1975–1990. Medicine, Science and Law, 35, 59–64.

- Brooke, D., Taylor, C., Gunn, J., & Maden, A. (1996). Point prevalence of mental disorder in unconvicted male prisoners in England and Wales. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.).), 313(7071), 1524–1527. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.313.7071.1524

- Brooker, C., & Gojkovic, D. (2009). The second national survey of mental health in-reach services in prisons. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 20(S1), S11– S28.

- Brooker, C., & Ullmann, B. (2008). Out of sight, out of mind. The state of mental healthcare in prison. Policy exchange. Clutha House.

- Byrne, D. (2005). Complexity, configurations and cases. Theory Culture & Society, 22, 95–111.

- Byrne, D. (2013). Evaluating complex social interventions in a complex world. Evaluation, 19 (3), 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389013495617

- Cassidy, K., Dyer, W., Biddle, P., Brandon, T., McClelland, N., & Ridley, R. (2020). Making space for mental health care within the penal estate. Health & Place, 62, 102295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102295

- Cloyes, K. G. (2007). Challenges in residential treatment for prisoners with mental illness: A follow-up report. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 21(4), 192–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2007.02.009

- Coid, J., Petruckevitch, A., Bebbington, P., Jenkins, R., Brugha, T., Lewis, G., Farrell, M., & Singleton, N. (2006). Psychiatric morbidity in prisoners and solitary cellular confinement, I: disciplinary segregation. British Journal of Psychiatry, 188(5), 423–431. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.188.5.423

- Coid, J. W. (1988). Mentally abnormal prisoners on remand: I-Rejected or accepted by the NHS? British Medical Journal (Clinical Research ed.).), 296(6639), 1779–1782. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.296.6639.1779

- Council of Europe. (1993). Report to the Dutch Government on the visit to the Netherlands carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 30 August to 8 September 1992. https://rm.coe.int/1680697759

- Council of Europe. (2015). Report to the Government of the Netherlands on the visit to the Caribbean part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 12 to 22 May 2014. https://rm.coe.int/1680697831

- Crichton, J., & Nathan, R. (2015). The NHS must manage the unmet mental health needs in prison. The Health Service Journal, 18th August 2015. The Health Service Journal. https://www.hsj.co.uk/leadership/the-nhs-must-manage-the-unmet-mental-health-needs-in-prison/5087856.article

- Dalkin, S. M., Greenhalgh, J., Jones, D., Cunningham, B., & Lhussier, M. (2015). What’s in a mechanism? Development of a key concept in realist evaluation. Implementation Science, 10(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0237-x

- Daniel, E. A. (2007). Care of the mentally ill in prisons: Challenges and Solutions. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 35(4), 406–410.

- Dell, S., Robertson, G., James, K., & Grounds, A. (1993). Remands and psychiatric assessments in Holloway prison I: The psychotic population. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 163, 634–640. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.163.5.634

- Department of Health. (1999). Effective care co-ordination in mental health services: modernising the care programme approach – A policy booklet. http://www.cpaa.org.uk/uploads/1/2/1/3/12136843/effective_care_coordination_1999.pdf

- Department of Health. (2011). The transfer and remission of adult prisoners under s47 and s48 of the Mental Health Act: A good practice procedure guide. Gov.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-transfer-and-remission-of-adult-prisoners-under-s47-and-s48-of-the-mental-health-act

- Fazel, S., Ramesh, T., & Hawton, K. (2017). Suicide in prisons: an international study of prevalence and contributory factors. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(12), 946–952. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30430-3

- Ford, M. (2015). America’s largest mental hospital is a jail. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/06/americas-largest-mental-hospital-is-a-jail/395012/

- Fowles, A. J. (1993). The mentally abnormal offender in the era of community care. In W. Watson & A. Grounds (Eds.), The mentally disordered offender in an era of community care. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Freeman, R. J., & Roesch, R. (1989). Mental disorder and the criminal justice system: A review. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 12(2-3), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-2527(89)90002-2

- Giblin, Y., Kelly, A., Kelly, E., Kennedy, H. G., & Mohan, D. (2012). Reducing the use of seclusion for mental disorder in a prison: implementing a high support unit in a prison using participant action research. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 6(1), 2–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-6-2

- Grounds, A. (1991). The transfer of sentenced prisoners to hospital 1960-1983: Study in One Special Hospital. The British Journal of Criminology, 31(1), 54–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a048085

- Hargreaves, D. (1997). The transfer of severely mentally ill prisoners from HMP Wakefield: A descriptive study. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 8(1), 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585189708411994

- House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts. (2017). Mental Health in Prisons. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmpubacc/400/400.pdf

- House of Commons Justice Committee. (2009). Role of the Prison Officer. The Stationery Office.

- House of Commons Library. (2018). Mental health in prisons. Debate Pack: Number CDP-2017-0266, (8 January 2018). http://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CDP-2017-0266/CDP-2017-0266.pdf

- Isherwood, S., & Parrott, J. (2002). Audit of transfers under the Mental Health Act from prison – the impact of organisational change. Psychiatric Bulletin, 26(10), 368–370. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.26.10.368

- Kupers, T. A., Dronet, T., Winter, M., Austin, J., Kelly, L., Cartier, W., Morris, T. J., Hanlon, S. F., Sparkman, E. L., Kumar, P., Vincent, N. C., Norris, J., Nagel, K., & McBride, J. (2009). Beyond supermax administrative segregation: Mississippi’s experience rethinking prison classification and creating alternative mental health programs. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36(10), 1037–1050. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854809341938

- Lamb, R. H., & Weinberger, L. E. (2005). The shift of psychiatric inpatient care from hospital to jails and prisons. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 33(4), 529–534.

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 160940691773384. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Manzano, A. (2016). The craft of interviewing in realist evaluation. Evaluation, 22(3), 342–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389016638615

- McKenzie, N., & Sales, B. (2008). New procedures to cut delays in transfer for mentally ill prisoners to hospital. Psychiatric Bulletin, 32(1), 20–22. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.107.015958

- Mental Health Act. (1983). As amended 2007). Legislation.Gov.UK. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2007/12/contents.

- Ministry of Justice. (2013). Transforming rehabilitation: A strategy for reform. The Stationary Office.

- Ministry of Justice. (2016). Prison safety and reform. The Stationary Office.

- North East of England NHS Mental Health Foundation Trust (NE-MH Trust).. (2016). Delayed mental health transfers (September 2016). in North East of England NHS Mental Health Foundation Trust (2017) ‘Options appraisal for the development of an enhanced care mental health care service within [Reception Prison in the North east of England]’ (MH Enhanced Service – [Reception Prison in the North east of England], January 6 2017).

- North East of England NHS Mental Health Foundation Trust (NE-MH Trust). (2017a). Mental Health Enhanced Care and Observation Unit/Area - Operational Processes (January 2017).

- North East of England NHS Mental Health Foundation Trust (NE-MH Trust). (2017b). Admission Criteria draft 3 (February 2017).

- North East of England NHS Mental Health Foundation Trust (NE-MH Trust). (2017c). The Patient Pathway Flow Diagram (November, 2017).

- North East of England NHS Mental Health Foundation Trust (NE-MH Trust). (2017d). The Patient Journey document (November, 2017).

- North East of England NHS Mental Health Foundation Trust (NE-MH Trust). (2017e). Options appraisal for the development of an enhanced care mental health care service within [Reception Prison in the North east of England]. (MH Enhanced Service – [Reception Prison in the North east of England], January 6 2017).

- North East of England NHS Mental Health Foundation Trust (NE-MH Trust). (2017f). Project Proposal (Feb. 2017).

- North East of England NHS Mental Health Foundation Trust (NE-MH Trust). (2017g). HMP Information About The Unit (Dec. 2017).

- O’Connor, F. W., Lovell, D., & Brown, L. (2002). Implementing a Residential Treatment for Prison Inmates with Mental Illness. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 16, 232–238.

- Parliamentary Questions. (2017). Prisoners: Mental Illness: Written question – 110003. Parliamentary Business. https://www.parliament.uk/business/publications/written-questions-answers-statements/written-question/Commons/2017-10-26/110003

- Pawson, R. (2013). The science of evaluation: A realist manifesto. Sage.

- Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic evaluation. Sage.

- Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (2004). Realist evaluation. Sage.

- Pawson, R., & Manzano-Santaella, A. (2012). A realist diagnostic workshop. Evaluation, 18(2), 176–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389012440912

- Peay, J. (1994). Mentally disordered offenders. In M. Maguire, R. Morgan & R. Reiner (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of criminology (pp. 1119–1160). Clarendon Press.

- Penrose, L. S. (1939). Mental disease and crime: Outline of a comparative study of European statistics. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 18(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1939.tb00704.x

- Prison Reform Trust. (2018). Mental Healthcare in Prisons. http://www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk/WhatWeDo/ProjectsResearch/Mentalhealth

- Public Health England. (2018). Severe mental illness (SMI) and physical health inequalities. Gov.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/severe-mental-illness-smi-physical-health-inequalities

- Raoult, S., & Harcourt, B. E. (2017). The mirror image of asylums and prisons: A study of institutionalization trends in France (1850–2010). Punishment & Society, 19(2), 155–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474516660696

- Robertson, G., Dell, S., James, K., & Grounds, A. (1994). Psychotic men remanded in custody to Brixton prison. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 164(1), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.164.1.55

- Rutherford, H., & Taylor, P. J. (2004). The transfer of women offenders with mental disorder from prison to hospital. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 15(1), 108–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940310001641272

- Samele, C., Forrester, A., Urquia, N., & Hopkin, G. (2016). Key successes and challenges in providing mental health care in an urban male remand prison: a qualitative study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(4), 589–596. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1170-2

- Sharpe, R., Völlm, B., Akhtar, A., Puri, R., & Bickle, A. (2016). Transfers from prison to hospital under Sections 47 and 48 of the Mental Health Act between 2011 and 2014. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 27(4), 459–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2016.1172660

- Shaw, J., Senior, J., Hayes, A., Roberts, A., Evans, G., Rennie, C., James, C., Mnyamana, M., Senti, J., Trwoga, S., Whittaker, I., Taylor, P., Maslin, L., de Viggiani, N., Jones, G. (2008). An Evaluation of the Department of Health’s ‘Procedure for the Transfer of Prisoners to and from Hospital under sections 47 and 48 of the Mental Health Act 1983’ Initiative. October 2008. NHS National R&D Programme on Forensic Mental Health.

- Singleton, N., Meltzer, H., Gatward, R., Coid, J., & Deasy, D. (1998). Psychiatric morbidity among prisoners: Summary report. Office for National Statistics.

- Skegg, K., & Cox, B. (1991). Impact of psychiatric services on prison suicide. The Lancet, 338(8780), 1436–1439. https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(91)92732-H

- Sloan, A., Allison, E. (2014). We are recreating Bedlam: the crisis in prison mental health services. The Guardian Newspaper. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/may/24/we-are-recreating-bedlam-mental-health-prisons-crisis

- Steadman, H. J., Monahan, J., Duffee, B., Hartstone, E., & Robbins, P. C. (1984). The impact of state mental hospital deinstitutionalisation on United States prison populations, 1968-1978. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 75, 474–490.

- Steadman, H. J., & Morrissey, J. P. (1987). The impact of deinstitutionalisation on the criminal justice system: Implications for understanding changing modes of social control. In J. Lowman, R. J. Menzies, & T. S. Palys (Eds.), Transcarceration: Essays in the sociology of social control (pp. 227–248). Aldershot: Gower.

- Tak, P. J. P. (2008). The Dutch criminal justice system. Wolf Legal Publishers.

- Tilley, N. (2000). Presented at the Founding Conference of the Danish Evaluation Society, Realistic Evaluation: An Overview., September 2000.

- Torrey, E. F., Kennard, A. D., Eslinger, D., Lamb, R., & Pavle, J. (2010). More mentally ill persons are in jails and prisons than hospitals: A survey of the states. Treatment Advocacy Centre and National Sheriffs Association.

- Towl, G., & Crighton, D. (2017). Suicide in prisons: Prisoners’ lives matter. Waterside Press.

- Walsh, E., & Freshwater, D. (2009). Developing the mental health awareness of prison staff in England and Wales. Journal of Correctional Health Care: The Official Journal of the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, 15(4), 302–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078345809341532

- Weller, M. P. I., & Weller, B. G. A. (1988). Crime and mental illness. Medicine, Science and the Law, 28(1), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/002580248802800111