Abstract

Pro re nata (PRN, as-needed) medication is commonly used in forensic psychiatric inpatient care, but little is known about the participation of patients in its prescription and administration. This study describes patient participation in PRN medication treatment in forensic psychiatric inpatient care. Data were collected during interviews with 34 inpatients and 19 registered nurses in a Finnish forensic psychiatric hospital. The data underwent inductive content analysis. We found that patient participation in PRN was related to patients’ individual needs and health conditions, and the use of PRN involved private decisions made in the social context of the ward. PRN was an integrated part of daily care, and it involved three stakeholders, namely patients, nurses, and physicians; however, the role of patients in this collaboration was undefined. The administration events for PRN were multiform, and depended on the level of agreement between patients and nurses on the need for PRN. In the future, more attention should be paid to how to motivate patients and provide them with equal opportunities to be involved in the planning of PRN, and to optimize shared decision making so that the expertise of both patients and nurses is utilized in the administration and evaluation of PRN.

The participation of patients in the prescription and administration of their pro re nata (PRN, as-needed) medication has been emphasized in psychiatric care (Baker et al., Citation2007). In addition to being an ethical right (Lindberg et al., Citation2019), involving patients in decisions on their medication can support their adherence to treatment (NICE, Citation2009; Torrecilla-Olavarrieta et al., Citation2020) and help them to learn how to safely and effectively use PRN, based on their individual medication needs, to improve their quality of life. However, forensic psychiatric patients are particularly vulnerable when it comes to participation due to their poor mental health status and the involuntary nature of treatment (Selvin et al., Citation2016, Citation2021). In addition, patient participation has been threatened by power imbalances between patients and staff (Hörberg & Dahlberg, Citation2015; Söderberg et al., Citation2020) and paternalistic treatment cultures (Haines et al., Citation2018; Selvin et al., Citation2016). Forensic inpatients have reported their willingness to participate (Selvin et al., Citation2016) and provide opinions on their care (Marklund et al., Citation2020). Nonetheless, patients’ participation has been found to be limited (Eidhammer et al., Citation2014; Haines et al., Citation2018; Söderberg et al., Citation2020), and patients have rated patient participation as the lowest-quality aspect of their care (Schröder et al., Citation2016).

PRN is part of pharmacological care and is used in addition to regular medication (Vaismoradi et al., Citation2018). It has been reported that 70–90% of patients in psychiatric hospitals receive psychotropic PRN (Baker et al., Citation2008; Martin et al., Citation2017). It is also prevalent in forensic psychiatric care; in one study, 37% of patients received sedative PRN over a two-week period (Haw & Wolstencroft, Citation2014), and another found that 54% used PRN for psychiatric reasons for over a year (Hipp et al., Citation2020). Studies suggest that the most commonly used psychotropic PRN medications are benzodiazepines and antipsychotics (Hales & Gudjonsson, Citation2004; Haw & Wolstencroft, Citation2014), particularly for agitation (Haw & Wolstencroft, Citation2014), anxiety, and psychotic symptoms (Hipp et al., Citation2020). In addition, patients use PRN to alleviate acute physical symptoms (Hipp et al., Citation2020; Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network, Citation2018).

Ideally, the patient is considered to be an active and equal individual (Nilsson et al., Citation2019; Thórarinsdóttir & Kristjánsson, Citation2014) and an agent in their own care and decision making (Jørgensen & Rendtorff, Citation2018). Patient participation also means that patients are involved in the planning of PRN prescriptions (Baker et al., Citation2007) and in alternative methods useful to them in times of crisis (Papapietro, Citation2019). Further, it includes that PRN is used for patients’ individual needs (Usher et al., Citation2009), and that patients’ views on the need and time for their use are considered. This requires respectful, two-way communication and information sharing between patients and staff (Vaismoradi et al., Citation2020). It has been suggested that the participation of forensic patients can be promoted by encouraging patients to make decisions to the extent possible in restricted contexts (Söderberg et al., Citation2020). PRN can provide such opportunity because each administration of medication is preceded by decision making involving both the patient and staff (Barr et al., Citation2018).

In mental health care, both patients and nurses can, and do, initiate PRN (Barr et al., Citation2018), but the decision of whether PRN is administered significantly depends on nurses (Jimu & Doyle, Citation2019). Patients and staff may disagree about the need for PRN (Barr et al., Citation2018) and the feasibility of its non-pharmacological alternatives (Martin et al., Citation2018). Patients have reported incidents of staff making decisions without their input (Cleary et al., Citation2012). However, PRN practices may differ between forensic and acute mental health care facilities. For example, fewer patients have been prescribed psychotropic PRN in forensic care (Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network, 2018). In a study by Barr et al. (Citation2018), nurses reported that PRN is mostly patient initiated in forensic care, in contrast to acute care. In addition, nurses working in acute care have had more experiences of ineffective PRN, and they are more confident in using alternative interventions. Previous studies in forensic care have focused on PRN medication (Barr et al., Citation2018) or patient participation (Magnusson et al., Citation2020; Selvin et al., Citation2016, Citation2021; Söderberg et al., Citation2020), but research on patient participation in PRN in forensic psychiatric settings is lacking.

In this study, PRN is understood to be medication used as needed for any physical or psychiatric reason. This study aimed to describe patients’ and nurses’ perceptions on participation in PRN medication in forensic psychiatric inpatient care. This knowledge can improve our understanding of PRN practices so that we can promote patient participation in these settings.

Materials and methods

Study design

We used a cross-sectional qualitative approach to gather information on the perceptions of patient participation in PRN (Dicicco-Bloom & Crabtree, Citation2006). We interviewed patients and nurses in a Finnish forensic psychiatric hospital in November and December 2019 and analyzed the data using inductive content analysis. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist was used to report the study (Tong et al., Citation2007).

Research environment

We recruited participants from one of Finland’s two state-run forensic psychiatric hospitals, which has 284 beds for adult patients. In the hospital, physicians are responsible for medication, and registered nurses are licensed to administrate it. All patients are involuntarily admitted based on the Mental Health Act (Citation1990), which provides three reasons for hospitalization in forensic care:

a sentence has been waived due to decreased criminal responsibility (53% of patients in the study hospital at the end of 2019),

there are high safety risks or other reasons why treatment in a municipal hospital would be inappropriate (44%), or

for a court-ordered mental state examination (3%).

Data collection

To collect the data using semi-structured interviews, we developed an interview guide (Kallio et al., Citation2016) based on the earlier literature (Hipp et al., Citation2018). The themes concerned patients’ knowledge about PRN, their role in the planning of PRN, patients’ and nurses’ decision making in PRN, and features of PRN administration. The guide was similar for patients and staff, but we adapted expressions and points of view for both groups. It was tested in the first patient and staff interviews, but no changes were needed, and these interviews were included in the data.

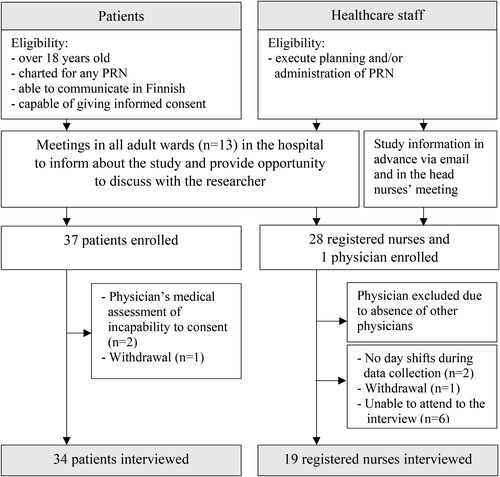

We worked with the hospital administration team and used purposive sampling to recruit participants who had experiences of PRN treatment in a forensic care setting (Palinkas et al., Citation2015). This included face-to-face meetings and electronic information letters. The recruitment process () provided all eligible individuals an equal opportunity to participate. We enrolled 53 participants: 34 patients () and 19 registered nurses (). Only one physician volunteered to take part, so we decided to focus on the patients and nurses.

Table 1. Self-reported background information of the patients (n = 34).

Table 2. Self-reported background information of the registered nurses (n = 19).

Individual interviews held in quiet rooms on the wards enabled patients to discuss sensitive topics in confidence (Baillie, Citation2019). Due to the hospital’s security protocol, a nurse or pharmacist was present but did not participate in the interviews.

We chose to conduct group interviews with the staff to enable participants’ interaction (Baillie, Citation2019). The researcher (K.H.) worked with a head nurse and organized the groups based on nurses’ work shifts and to comprise participants from different wards to decrease interruptions in their daily work. Altogether, five group interviews with 3–5 participants were held. In addition, we conducted one pair interview because of cancelations.

All the interviews were audiotaped. The patient interviews totaled 12 hours and 29 minutes and the nurse interviews 7 hours and 4 minutes. One researcher (K.H.) conducted all the interviews and made field notes (Phillippi & Lauderdale, Citation2018). The interviewer had no previous relationship with the participants.

Data analysis

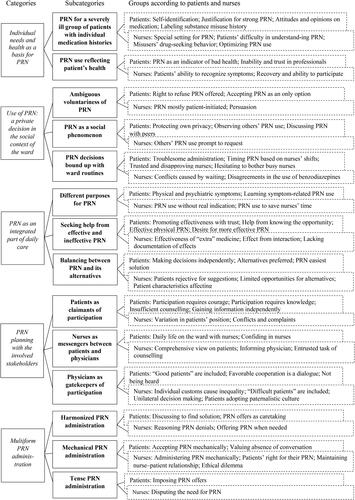

We used inductive content analysis to describe patient participation in PRN in a structured format (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008; Lindgren et al., Citation2020). The interviews were transcribed verbatim (412 pages) by one researcher (K.H.). The transcripts and field notes were read several times to get an understanding of the entire data. Then, the data were entered into QSR International’s NVivo 12 software. The meaning units in the patient data, which were words, sentences, and clauses, were inductively identified and grouped, and then combined into subcategories and abstracted again into main categories, based on their similarities and differences (). Subcategories and categories were inductively named, based on their content. We used a similar process (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008; Lindgren et al., Citation2020) with the staff interviews so that new categories could emerge. However, all meaning units from the staff interviews could be placed in the same categories as the patient data. The content analysis was conducted up to the subcategory stage by one researcher (K.H.). Then, both authors discussed the categories until a consensus was reached.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Committee on Research Ethics of the University of Eastern Finland and the hospital board. Participants were informed about the study aim, the voluntary nature of participation, and confidentiality. Written, informed consent was obtained from participants (WMA Declaration of Helsinki, Citation2013).

Results

Patients and nurses discussed similar content from their own particular viewpoints (). This content focused on five main categories: (1) Patient participation in PRN in forensic psychiatric inpatient care was based on the patients’ individual needs and health conditions; (2) the use of PRN was described as a private decision in the social context of the ward; (3) PRN was seen as an integrated part of care, and the planning of PRN included reviewing patient’s individual needs and discussing pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods for meeting those needs; (4) planning was carried out between three stakeholders—patients, nurses, and physicians—but their roles were undefined; and (5) PRN administration was multiform and depended on the level of agreement between the patients and nurses.

Individual needs and health as a basis for PRN

PRN for a severely ill group of patients with individual medication histories. Both patients and nurses saw forensic psychiatric patients as a unique group when it came to participation in PRN. Patients identified themselves as severely ill forensic patients who needed the strongest medications. One patient described this group as “the most difficult patients in Finland.” One nurse added that “our patients have special needs with PRN.” Nurses also thought patients’ illnesses made it difficult for them to participate in PRN decisions and to even understand the meaning of PRN. Patient participation was connected to medication history. Patients had favorite drugs and those they disliked, or they were either keen or avoidant toward medication in general. Some patients with a history of substance misuse avoided PRN because they associated it with addictive behavior. Nurses connected such history to drug-seeking behavior and saw requests as a habit, and patients could feel stigmatized as misusers. Nurses described trying to optimize PRN use to match medication needs by encouraging drug-avoidant patients and inhibiting drug-seeking patients.

It goes like the physician has prescribed it. If it can be taken three times, then the patient will ask for it three times. (Nurse 10)

I decline the medication; I don’t fancy using it. I think there’re other means than seeking as-needed. (Patient 8)

I guess people pop something as if it’s a kind of a habit. That’s when they seek at least Burana (ibuprofen) or paracetamol and whatever is available. (Nurse 2)

PRN use reflecting patient’s health. Both patients and nurses described PRN use as an indicator of the patient’s health and wellbeing. PRN was particularly used during acute phases. To patients, a professional’s suggestion to take PRN could be a sign of their deteriorating health. Patients suggested that nurses could perceive PRN requests as indicators of bad health. However, to nurses, a patient seeking PRN could demonstrate the patient’s capability of self-treatment. Patients expressed feeling incapable of evaluating their PRN needs when in poor mental health, and trusted professionals to make the decisions. Nurses stated that patients’ abilities to participate increase as they recover.

Surely when someone is in as bad shape as I was then, they aren’t able to request any medication, and the physician just has to order something. (Patient 5)

Use of PRN: a private decision in the social context of the ward

Ambiguous voluntariness of PRN. Patients and nurses found that patient participation in PRN had special features compared to regular medication, as taking PRN is inherently voluntary. However, in situations where a patient was exhibiting severe symptoms and was a risk to themselves or others, the voluntariness of PRN became ostensible. In those situations, nurses had tried to convince the patient to take PRN, and patients had accepted PRN because they felt they had no option or because they thought refusing would have negative consequences on their treatment.

Someone is in extremely bad psychiatric condition and then staff say, “you should take this” and then a big gang gathers, starting with the physician. And there is only one patient. The patient’s experience can be that the medicine was almost forced on them, even if they finally took it themselves. (Nurse 1)

You get out of that situation when you take that medicine … [If you keep refusing it] you’ll get a bad reputation as a patient … and the nurses take a more stringent approach. (Patient 27)

PRN as a social phenomenon. Although PRN was perceived as a private matter, participants said that it has a social nature that influence patients’ decision making. Patients wanted to protect their privacy and did not want other patients to know about their PRN use. The ward, as a public place, could even be a barrier to requesting medication. However, patients observed others’ PRN use there. From the perspective of the nurses, PRN had a strong social element on the ward as patients could be prompted to seek PRN when they saw someone else receive it. In addition, patients discussed and were well informed about their peers’ PRN use.

If you start to discuss it there in the corridor, there are other patients. It’s a little bit that kind of an issue anyway that you don’t want to start talking about it. (Patient 6)

Their peers guide them in what kind of medicines are worth taking and what symptoms to whine about to get those particular as-needed medicines. (Nurse 14)

PRN decisions bound up with ward routines. In addition to individual needs and timing, participants connected PRN decisions to ward routines. Some patients desisted from requesting PRN because they found the administration of them on the ward too troublesome. Patients got frustrated when nurses took too long to double-check PRN administration, and nurses said that this could lead to conflict. Patients timed their PRN requests; they avoided night shifts when a nurse would be called from another ward to double-check the administration. Patients also observed the staff; they avoided seeking PRN from nurses they assumed were disapproving, or hesitated to bother busy nurses. Nurses indicated that most of the conflicts during shared decision making on PRN were due to different views about hospital policies on medication. Particularly, patients preferred benzodiazepines, but professionals avoided their use.

They get upset as they think they should get it right away. They may even erupt and say, “then I won’t take it at all”. And they don’t and then you have to negotiate. (Nurse 8)

I barely go to get it, if that one nurse is present, but if some of the nice nurses are there it’s easier to go and get as-needed. (Patient 20)

I requested it (benzodiazepines) just for kicks. Nothing came out of it; I knew that I wouldn’t get it. (Patient 33)

Patients are keen to say, “give me that red liquid (diazepam)”. But we’d rather give them something else, and then there is this discussion and they say, “why didn’t you bring it when other nurses bring this and that”. (Nurse 1)

PRN as an integrated part of daily care

Different purposes of PRN. The patients and nurses who were interviewed considered PRN as a means to alleviate both physical and psychiatric symptoms and said that PRN was mostly patient initiated. Patients had individual opinions regarding which symptoms warranted medication, and they had learned symptom-related PRN treatment during rehabilitation. However, the nurses said that patients also requested PRN out of habit, out of boredom, or to make contact with the staff. Participants thought that PRN was, and should be, based on patients’ preferences, but they also illustrated staff-oriented practices, such as using PRN to save time.

I’ve made kind of a symptom management template. Then I know when I need to go to get medicine. (Patient 27)

Seeking help from effective and ineffective PRNs. Nurses indicated that patients found PRN effective because it was “something extra”. Its effectiveness was also based on the patients’ trust in the medication and the interaction during administration. Patients felt that sometimes just knowing there was the option of taking PRN eased their symptoms. Patients frequently found PRN for physical needs more helpful than psychotropic PRN. Some patients had discontinued ineffective PRN, but others kept resorting to it. According to nurses, patients rarely reported effectiveness, and their views were often undocumented.

At least I want to believe it. When I strongly believe it, it has kind of a placebo effect (laughed), because I don’t think medicine really has any effect. (Patient 33)

It’s hard to say if it really helps or if it is the other person’s presence and kind of understanding that helps more than the medicine. (Nurse 17)

Balancing between PRN and its alternatives. Patients’ decisions on whether to request PRN was associated with non-pharmacological alternatives. They preferred alternatives and found them effective, but PRN was easier. Often, when they requested PRN, they had already made their decision and could be less open to considering alternatives. Nurses said that lacking staff resources and patient restrictions, such as seclusion, limited the use of alternatives. Their decision making was also related to patient characteristics; nurses felt that they were more likely to propose alternatives to patients who were known to be capable, female patients, and patients who repeatedly used PRN.

I can go play or listen to music or something like that, but sometimes you just don’t have the energy. Then I take the as-needed right away because I know it helps. (Patient 5)

If during a handover with nurses, for example, a patient comes to ask for as-needed, I just give it to them quite quickly. That way I can continue with my current task. (Nurse 6)

PRN planning with the involved stakeholders

Patients as claimants of participation. Both nurses and patients described that the role of patients in PRN planning was dependent on the patient’s motivation and courage, and the patient was seen as a claimant in the process. Some patients had excluded themselves from the planning and, due to lack of motivation or confidence, found it easier to adopt an outsider’s role in their own care. Others wished that professionals would invite them to participate, or they wished for a more active role. When feeling unheard, patients had resorted to aggressive behavior, withdrawn their cooperation, or written complaints about care. The participants agreed that patients need sufficient information on medication to participate, but that in practice, patient counseling is insufficient and unsystematic. Furthermore, patients perceived that they received biased information that was deliberately selected by the staff to support the staff’s preferences. Thus, patients actively sought information, especially from the internet, but this required motivation and information acquisition skills.

I’ve always said to each physician and nurse that I’ve had here that I trust their decisions. I trust they know their profession. (Patient 30)

I haven’t been asked at any time what I would want. (Patient 13)

It would be good to know a little bit about their short-term effects and what different medicines there are to choose from. I don’t really know. Due to my laziness, I haven’t sorted it out. (Patient 32)

Nurses as messengers between patients and physicians. Nurses felt that they had a comprehensive view of the patients’ situations due to their close relationships with the patients and the time spent together, but during physician appointments, patients often tried to hide their symptoms. This positioned nurses as two-way messengers between patients and physicians: they informed physicians about the patients’ needs and explained the physicians’ decisions to the patients. The nurses also stated that, although physicians are responsible for patient education on medication, it was effectively entrusted to nurses.

Observations of patients’ conditions come more from nursing staff, and we convey them to the physician. The physician, of course, then makes their evaluations and decisions based on what we have said. (Nurse 7)

Physicians as gatekeepers of participation. Physicians were described as gatekeepers as they either engaged with patients in the planning of PRN prescriptions or made decisions without consultation. In the worst cases, patients were not even informed about PRN decisions. Physicians’ various individual work practices created a sense of inequality. Patients felt that physicians were more willing to engage with “good patients” (Patient 11) who were reliable and compliant. In contrast, nurses found that “difficult patients” (Nurse 16) with strong preferences were more likely to pursue and obtain involvement. As a solution to inequality, nurses suggested systematically scheduled meetings with all three stakeholders. Patients and nurses described favorable cooperation as there was equal dialogue that valued the patients’ expertise. When cooperation failed, decision making became unilateral: either the physicians fulfilled the patients’ wishes too easily or the patients lacked the power to influence decisions. Nurses also suggested that some patients had assimilated to a paternalistic treatment culture, resulting in them expecting the professionals to make all the decisions about their care.

It is common that particular patients get physicians’ appointments more often. They take that attention. The kind of silent ones don’t, and it might be that their medication hasn’t been reviewed for a long time. (Nurse 11)

The physician is responsible, based on human legislation. I think patients should be listened to more because the patients empirically experience the medication, know how it effects them and its pros and cons. (Patient 9)

Patients aren’t taken seriously … I don’t know. Patients are patients and professionals are professionals, even if we’re just all humans. (Patient 18)

Multiform PRN administration

According to participants, PRN administration events varied because of the different levels of agreement in the opinions of patients and nurses on the need for PRN and how these opinions were expressed.

Harmonized PRN administration, referring to mutual discussion about symptoms and possible solutions, was seen as optimal, which resulted in a consensus about the need for medication. Patients valued nurses showing kindness and respecting their opinions. Patients also accepted being denied PRN if nurses provided a medical explanation. Participants suggested that if patients were incapable of initiating PRN, it was acceptable for nurses to offer PRN if they saw that a patient’s health was deteriorating. Patients thus saw an offer of PRN as favorable caretaking in such situations.

We talk and discuss and then consider whether to take medication to help or what. (Patient 29)

Mechanical PRN administration occurred when communication was scarce: nurses administered PRN at patients’ requests without expressing their own opinions, or patients automatically accepted PRN. Sometimes patients’ views were not sought, especially if they were too unwell to interact. Nurses sometimes doubted the need for medication, but they limited shared decision making due to patients’ disinclination, to avoid conflicts, or to maintain a therapeutic nurse-patient relationship. Furthermore, they maintained that patients have the right to receive PRN prescribed to them or reasoned that patients’ subjective experiences should not be questioned. Patients valued limited interaction, but nurses perceived an ethical dilemma in administering PRN mechanically against their professional judgment.

They don’t say that this is as-needed, they just give it, but well, I was in poor condition there. (Patient 9)

It can have long-lasting effects on the connection with the patient if you basically show the patient that you don’t believe them. (Nurse 3)

It’s nice that they don’t ask many questions like “what’s going on with you?” They just kind of give you the medication. I’m happy that we don’t have to start a debate. (Patient 33)

Tense PRN administration occurred when patients and nurses disagreed on the need for medication, and one of them was determined that it should be administered. Nurses were more likely to question the need for PRN if they felt it was used too often. Sometimes, patients did not accept being denied PRN, and conflict and aggressive behavior could ensue. Tense PRN events also included nurses’ PRN offers that patients perceived as imposing.

If you start to ask them questions and discuss, you can get a punch. (Nurse 17)

I have always said that I take it when I want, not when others say. (Patient 16)

Discussion

This study produced new knowledge on how forensic psychiatric patients may be active in their PRN in ways that are invisible to professionals, challenges in considering both patients’ and nurses’ views during PRN events, and the perceived effectiveness of PRN. While patient participation in PRN planning has been highlighted from the viewpoint of prescribers of PRN (Baker et al., Citation2007), in this study, the planning of PRN was multidimensional. Patient participation in planning included discussing individual needs, possible interventions and counseling on their use. Patient participation did not just occur during interactions between patients and professionals. Patients played an active role as they observed the ward environment, learned PRN procedures, gained information, and made decisions on whether to request medication or use other methods. This is an important finding as forensic psychiatric patients have often been reported to have a more or less passive role in their treatment (Haines et al., Citation2018; Selvin et al., Citation2016). However, patients struggled to actively cooperate and establish their role in planning their PRN care with professionals. As supported by earlier literature, participation was linked to patients’ knowledge (Mikesell et al., Citation2016), ability, and motivation (Selvin et al., Citation2016). Some patients chose to refuse participation and trusted staff to make the decisions, which is in line with an earlier study (Fumagalli et al., Citation2015). One worrying finding is that some patients who wanted to participate felt sidelined. Furthermore, purposive patients could be labeled as “difficult” or excluded from decision making to save time. This suggests a value–action gap (Bidabadi et al., Citation2019) in an environment where patient participation has been identified as a principle. Patient participation in the planning of PRN was described as an unreached ideal.

Previous studies have reported on complex decision making for nurses (Jimu & Doyle, Citation2019; Usher et al., Citation2009), but this study also provides new information on patients’ decision making. Our results indicate that patients’ PRN decisions were not just related to acute symptoms. They were also associated with the actions of the staff and fellow patients, hospital routines and policies, and what patients expected staff to observe from their PRN use. Further, this study adds knowledge on shared decision making in PRN administration. Interestingly, while forensic psychiatric patients were noticed to have impaired symptom recognition and understanding of the meaning of as-needed medication, the responsibility of PRN use was ceded to them. PRN was mostly initiated by patients, which was in line with an earlier study interviewing forensic nurses (Barr et al., Citation2018) but contrary to medication chart analyses from acute psychiatric care (Curtis et al., Citation2007; Richardson et al., Citation2015; Stewart et al., Citation2012). Based on our results, PRN was usually administered in agreement. However, this was more due to a lack of shared decision making rather than actual consensus. Nurses seemed to have a perception of optimal PRN use, but this was not achieved in the current practice, which was strongly based on patients’ wishes. Nurses limited their interaction with patients during administration events to avoid conflicts and maintain the perception of mutual trust. Thus, the decision making of PRN administration was linked not only to its indication but more broadly to a therapeutic relationship (Moreno-Poyato et al., Citation2016). The finding also reflects the prominent role of risk assessment in forensic psychiatric nurses’ decision making and their awareness that disagreements in PRN administrations may lead to violent behavior (Radisic & Kolla, Citation2019). Participants supported the patients’ right to have their medication. The ethical dilemma that nurses face of balancing patients’ and professionals’ preferences is an important area for future research.

Patients’ experience of participation could also be threatened if they struggled to recognize their symptoms and need for PRN. As forensic psychiatric care involves patients with severe mental illnesses and complex problems (Sampson et al., Citation2016), patients might have acute needs for PRN but also for special support in their pharmacological care from professionals. Even if patients suggested that poor health made them incapable of participating, they could perceive nurses’ offers of PRN as imposing. Patients acknowledged that they were never forced to take PRN, but they had experienced pressure (Szmukler & Appelbaum, Citation2008) and no-option coercion to do so (Tuohimäki, Citation2007). This calls into question the voluntary basis of PRN (Lorem et al., Citation2014), a notion that the participants affirmed, at least in theory. Perceived coercion (Sampogna et al., Citation2019) is an important issue in the topical debate of coercion in mental health (Gooding et al., Citation2020).

Finally, this study produced important new knowledge on how patients perceive the usefulness and effectiveness of PRN. Patients were helped by both the medication and the conversations with nurses and their compassion during PRN events. Thus, PRN provides possibilities for significant encounters (Rytterström et al., Citation2020) during treatment. Further, being aware that they could receive PRN made them feel safe, which sometimes was even more effective than medication. This contradicts the recommendation that PRN prescriptions should be canceled if unused (Wright et al., Citation2012). It is important to discuss with patients how they perceive PRN as part of their care and inquire and document their views on the effectiveness of PRN.

Strengths and limitations

The study limitations involve possible sample biases, the trustworthiness of the data, and the transferability of the findings. We provided all registered nurses and adult patients in the hospital an equal opportunity to participate. It is possible that patients who agreed to take part had stronger views about patient participation or PRN treatment. Some patients might have refused to participate because they knew that a staff member would be present during the interviews. In addition, only including patients capable of providing informed consent might have biased our sample. However, the informants did discuss PRN treatment for patients with low functional levels.

The presence of staff member might have influenced patients’ comfort levels with discussing their perceptions (Tong et al., Citation2007). However, we tried to create a climate that enabled patients to share their experiences as freely as possible. The researcher (K.H.) is an experienced mental health nurse, but she did not have a clinical relationship with the participants or the study hospital. Both authors have expertise in conducting qualitative research. Field notes were made during and after the interviews (Phillippi & Lauderdale, Citation2018).

The relatively large sample provided rich data, and saturation was achieved. Trustworthiness could have been strengthened by participants’ feedback during the analysis. The data were collected in one hospital, but the participants represented 13 wards with different security levels. From the viewpoint of the transferability of our findings, it should be noted that PRN treatment may vary between organizations and countries (Edworthy et al., Citation2016). However, we believe that the findings of this study are generalizable for promoting a shared target of patient participation in forensic psychiatric services.

Implications

The findings of this study suggest courses of action for developing patient participation in PRN in forensic psychiatric inpatient care. First, there is a definite need to continue establishing and promoting a care culture in which patient participation is respected and desirable. This means inviting patients to take part in shared decision-making, respecting expertise that comes with experience, and valuing individual opinions. Second, patient participation could be promoted with a more systematic approach in the planning of PRN, including patient education, counseling, and regular appointments for patients with professionals to review, assess and discuss PRN medication and its alternatives. Third, in forensic psychiatric care, patients’ motivation and ability to participate is associated with their mental health. It is important to find ways to promote patient participation in phases of poor mental health as well. However, health care professionals have an ethical responsibility to evaluate patients’ decisional capacity and to ensure quality care when a patient is incapable of recognizing what is best for them in the current situation. Fourth, based on patients’ and nurses’ descriptions of PRN administrations, having a conversation in an acute situation can be challenging. This highlights the urgency of planning PRN and other preferable methods for acute symptoms in advance. However, it is also important that nurses can competently interact in PRN events so that the expertise of both the patient and the professionals is utilized to ensure the best possible care for the patient.

Conclusions

PRN medication is commonly used in forensic psychiatric inpatient care, and thus the participation of patients in planning and executing PRN is realized daily. Patient participation in planning, decision making, and finding alternatives is needed to ensure individual and contextual PRN care. The optimal administration of PRN for forensic psychiatric patients is based on mutual discussions between patients and nurses, in which patients are heard and informed, regardless of whether PRN medication is administered. The varying opportunities for patients to participate indicate a need for a more systematic approach to promote patient participation throughout the PRN process, which would provide more equal opportunities for patient participation, and relieve patients of having to be proactive about their desire to play an active role in decision making.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Committee on Research Ethics of the University of Eastern Finland and the hospital board. All participants provided written, informed consent after an adequate time for decision making had passed.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and registered nurses for sharing their experiences and the staff members for their contributions to recruitment and data collection.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baillie, L. (2019). Exchanging focus groups for individual interviews when collecting qualitative data. Nurse Researcher. Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7748/nr.2019.e1633

- Baker, J. A., Lovell, K., & Harris, N. (2008). A best-evidence synthesis review of the administration of psychotropic pro re nata (PRN) medication in in-patient mental health settings. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17(9), 1122–1131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02236.x

- Baker, J. A., Lovell, K., Harris, N., & Campbell, M. (2007). Multidisciplinary consensus of best practice for pro re nata (PRN) psychotropic medications within acute mental health settings: A Delphi study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 14(5), 478–484. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01112.x

- Barr, L., Wynaden, D., & Heslop, K. (2018). Nurses’ attitudes towards the use of PRN psychotropic medications in acute and forensic mental health settings. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(1), 168–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12306

- Bidabadi, F. S., Yazdannik, A., & Zargham-Boroujeni, A. (2019). Patient’s dignity in intensive care unit: A critical ethnography. Nursing Ethics, 26(3), 738–752. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733017720826

- Cleary, M., Horsfall, J., Jackson, D., O'Hara-Aarons, M., & Hunt, G. E. (2012). Patients' views and experiences of pro re nata medication in acute mental health settings. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 21(6), 533–539. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00814.x

- Curtis, J., Baker, J. A., & Reid, A. R. (2007). Exploration of therapeutic interventions that accompany the administration of p.r.n. (‘as required’) psychotropic medication within acute mental health settings: a retrospective study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 16(5), 318–326. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2007.00487.x

- Dicicco-Bloom, B., & Crabtree, B. F. (2006). The qualitative research interview. Medical Education, 40(4), 314–321. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x

- Edworthy, R., Sampson, S., & Völlm, B. (2016). Inpatient forensic-psychiatric care: Legal frameworks and service provision in three European countries. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 47, 18–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2016.02.027

- Eidhammer, G., Fluttert, F. A., & Bjørkly, S. (2014). User involvement in structured violence risk management within forensic mental health facilities – a systematic literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23(19/20), 2716–2724. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12571

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Fumagalli, L. P., Radaelli, G., Lettieri, E., Bertele', P., & Masella, C. (2015). Patient empowerment and its neighbours: Clarifying the boundaries and their mutual relationships. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 119(3), 384–394. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.10.017

- Gooding, P., McSherry, B., & Roper, C. (2020). Preventing and reducing “coercion” in mental health services: An international scoping review of English‐language studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 142(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13152

- Haines, A., Perkins, E., Evans, E. A., & McCabe, R. (2018). Multidisciplinary team functioning and decision making within forensic mental health. Mental Health Review (Brighton, England), 23(3), 185–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/MHRJ-01-2018-0001

- Hales, H., & Gudjonsson, G. H. (2004). Effect of ethnic differences on the use of prn (as required) medication on an inner London medium secure unit. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 15(2), 303–313. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940410001702049

- Haw, C., & Wolstencroft, L. (2014). A study of the prescription and administration of sedative PRN medication to older adults at a secure hospital. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(6), 943–951. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610214000179

- Hipp, K., Kuosmanen, L., Repo-Tiihonen, E., Leinonen, M., Louheranta, O., & Kangasniemi, M. (2018). Patient participation in pro re nata medication in psychiatric inpatient settings: An integrative review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(2), 536–554.

- Hipp, K., Repo-Tiihonen, E., Kuosmanen, L., Katajisto, J., & Kangasniemi, M. (2020). PRN medication events in a forensic psychiatric hospital: A document analysis of the prevalence and reasons. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 19(4), 329–340.

- Hörberg, U., & Dahlberg, K. (2015). Caring potentials in the shadows of power, correction, and discipline - Forensic psychiatric care in the light of the work of Michel Foucault. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 10, 28703 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v10.28703

- Jimu, M., & Doyle, L. (2019). The administration of pro re nata medication by mental health nurses: A thematic analysis. Issues Ment Health Nurs, 40(6), 511–517. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2018.1543739

- Jørgensen, K., & Rendtorff, J. D. (2018). Patient participation in mental health care - perspectives of healthcare professionals: An integrative review. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 32(2), 490–501. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12531

- Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network. (2018). 2016 Forensic mental health patient survey report. https://www.justicehealth.nsw.gov.au/publications/2016-forensic-mental-health-patient-report-final-1.pdf

- Kallio, H., Pietilä, A. M., Johnson, M., & Kangasniemi, M. (2016). Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(12), 2954–2965. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13031

- Lindberg, J., Johansson, M., & Broström, L. (2019). Temporising and respect for patient self-determination. Journal of Medical Ethics, 45(3), 161–167. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2018-104851

- Lindgren, B. M., Lundman, B., & Graneheim, U. H. (2020). Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 108, 103632 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103632

- Lorem, G. F., Frafjord, J. S., Steffensen, M., & Wang, C. E. A. (2014). Medication and participation: A qualitative study of patient experiences with antipsychotic drugs. Nurs Ethics, 21(3), 347–358. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733013498528

- Magnusson, E., Axelsson, A. K., & Lindroth, M. (2020). ‘We try’—how nurses work with patient participation in forensic psychiatric care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 34(3), 690–697. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12773

- Marklund, L., Wahlroos, T., Looi, G. E., & Gabrielsson, S. (2020). ‘I know what I need to recover’: Patients' experiences and perceptions of forensic psychiatric inpatient care. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(2), 235–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12667

- Martin, K., Arora, V., Fischler, I., & Tremblay, R. (2017). Descriptive analysis of pro re nata medication use at a Canadian psychiatric hospital. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 26(4), 402–408. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12265

- Martin, K., Ham, E., & Hilton, N. Z. (2018). Staff and patient accounts of PRN medication administration and non-pharmacological interventions for anxiety. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(6), 1834–1841. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12492

- Mental Health Act 1116/1990. (14 December 1990). Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finland. https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/kaannokset/1990/en19901116_20101338.pdf

- Mikesell, L., Bromley, E., Young, A. S., Vona, P., & Zima, B. (2016). Integrating client and clinician perspectives on psychotropic medication decisions: Developing a communication-centered epistemic model of shared decision making for mental health contexts. Health Communication, 31(6), 707–717. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2014.993296

- Moreno-Poyato, A. R., Montesó-Curto, P., Delgado-Hito, P., Suárez-Pérez, R., Aceña-Domínguez, R., Carreras-Salvador, R., Leyva-Moral, J. M., Lluch-Canut, T., & Roldán-Merino, J. F. (2016). The therapeutic relationship in inpatient psychiatric care: A narrative review of the perspective of nurses and patients. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 30(6), 782–787. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2016.03.001

- NICE – National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2009). Medicines adherence: Involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence. Clinical guideline [CG76]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg76

- Nilsson, M., From, I., & Lindwall, L. (2019). The significance of patient participation in nursing care–a concept analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 33(1), 244–251. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12609

- Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 42(5), 533–544. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

- Papapietro, D. J. (2019). Involving forensic patients in treatment planning increases cooperation and may reduce violence risk. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 47(1), 35–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.29158/JAAPL.003815-19.

- Phillippi, J., & Lauderdale, J. (2018). A guide to field notes for qualitative research: Context and conversation. Qualitative Health Research, 28(3), 381–388. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317697102

- Radisic, R., & Kolla, N. J. (2019). Right to appeal, non-treatment, and violence among forensic and civil inpatients awaiting incapacity appeal decisions in Ontario. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 752 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00752

- Richardson, M., Brennan, G., James, K., Lavelle, M., Renwick, L., Stewart, D., & Bowers, L. (2015). Describing the precursors to and management of medication nonadherence on acute psychiatric wards. Gen Hosp Psychiatry, 37(6), 606–612. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.06.017

- Rytterström, P., Rydenlund, K., & Ranheim, A. (2020). The meaning of significant encounters in forensic care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. Advance Online Publication, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12889

- Sampogna, G., Luciano, M., Del Vecchio, V., Pocai, B., Palummo, C., Fico, G., Giallonardo, V., De Rosa, C., & Fiorillo, A. (2019). Perceived coercion among patients admitted in psychiatric wards: Italian results of the EUNOMIA study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 316–316. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00316

- Sampson, S., Edworthy, R., Völlm, B., & Bulten, E. (2016). Long-term forensic mental health services: An exploratory comparison of 18 European countries. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 15(4), 333–351. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2016.1221484

- Schröder, A., Lorentzen, K., Riiskjaer, E., & Lundqvist, L.-O. (2016). Patients’ views of the quality of Danish forensic psychiatric inpatient care. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 27(4), 551–568. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2016.1148188

- Selvin, M., Almqvist, K., Kjellin, L., & Schröder, A. (2016). The concept of patient participation in forensic psychiatric care: The patient perspective. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 12(2), 57–63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/JFN.0000000000000107

- Selvin, M., Almqvist, K., Kjellin, L., & Schröder, A. (2021). Patient participation in forensic psychiatric care: Mental health professionals' perspective. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30(2), 461–468. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12806

- Söderberg, A., Wallinius, M., & Hörberg, U. (2020). An interview study of professional carers' experiences of supporting patient participation in a maximum security forensic psychiatric setting. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 41(3), 201–210. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2019.1658833

- Stewart, D., Robson, D., Chaplin, R., Quirk, A., & Bowers, L. (2012). Behavioural antecedents to pro re nata psychotropic medication administration on acute psychiatric wards. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 21(6), 540–549. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00834.x

- Szmukler, G., & Appelbaum, P. S. (2008). Treatment pressures, leverage, coercion, and compulsion in mental health care. Journal of Mental Health, 17(3), 233–244. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230802052203

- Thórarinsdóttir, K., & Kristjánsson, K. (2014). Patients’ perspectives on person-centred participation in healthcare: A framework analysis. Nursing Ethics, 21(2), 129–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733013490593

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care : journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Torrecilla-Olavarrieta, R., Pérez-Revuelta, J., García-Spínola, E., López Martín, Á., Mongil-SanJuan, J. M., Rodríguez-Gómez, C., Villagrán-Moreno, J. M., & González-Saiz, F. (2020). Satisfaction with antipsychotics as a medication: the role of therapeutic alliance and patient-perceived participation in decision making in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorder. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, Aug 13, 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13651501.2020.1804942.

- Tuohimäki, C. (2007). The use of coercion in the Finnish civil psychiatric inpatients: a part of the Nordic project Paternalism and Autonomy [Doctoral dissertation, University of Oulu]. Acta Universitatis Ouluensis. http://urn.fi/urn:isbn:9789514285424

- Usher, K., Baker, J. A., Holmes, C., & Stocks, B. (2009). Clinical decision-making for 'as needed' medications in mental health care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(5), 981–991. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04957.x

- Vaismoradi, M., Amaniyan, S., & Jordan, S. (2018). Patient safety and pro re nata prescription and administration: A systematic review. Pharmacy, 6(3), 95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy6030095

- Vaismoradi, M., Jordan, S., Vizcaya-Moreno, F., Friedl, I., & Glarcher, M. (2020). PRN medicines optimization and nurse education. Pharmacy, 8(4), 201. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8040201

- WMA Declaration of Helsinki. ( 2013). Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. The World Medical Association. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/

- Wright, S., Stewart, D., & Bowers, L. (2012). Psychotropic PRN medication in inpatient psychiatric care: A literature review. Report from the Conflict and Containment Reduction Research Programme. London: Institute of Psychiatry at the Maudsley. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/ioppn/depts/hspr/archive/mhn/projects/PRN-Medication-Review.pdf