Abstract

Structured risk assessment is a widely accepted and recommended approach to establishing an individual’s level of risk for future adverse outcomes, such as violence or victimization, and to guide professionals in effectively managing that risk. A precondition for achieving these outcomes is that the risk assessment procedures are properly implemented and carried out as intended. Although research into the implementation of risk assessment instruments is slowly increasing, most publications do not provide detailed information on the steps that were taken during the implementation process. To help bridge the gap between research and practice, this paper describes step by step the implementation process of the Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability: Adolescent Version in a Dutch secure youth care service. The process was guided by the eight steps suggested in the guidebook for the implementation of risk assessment in juvenile justice by Vincent, Guy, and Grisso. Without pretending to offer the best or most ideal approach, this illustration of a risk assessment implementation process may serve as inspiration for other agencies and service providers who wish to integrate structured risk assessment into their practice.

Forensic treatment and rehabilitation settings often use structured risk assessment to gain insight into their patients’ level of risk for adverse outcomes, such as substance abuse or victimization, and, ultimately, to reduce those risks (Viljoen & Vincent, Citation2020). Although using risk assessment instruments in itself will not diminish risk, it is considered an essential first step in the process (Viljoen et al., Citation2018). That is, the information obtained from the risk assessment can aid professionals in matching the individual to the appropriate services, which, in turn, may decrease the risk of reexperiencing adverse outcomes (Bonta & Andrews, Citation2017). For this process to have the anticipated effect, risk assessment instruments should be implemented as intended (Nonstad & Webster, Citation2011). Müller-Isberner et al. (Citation2017, p. 465) stated that positive outcomes can only be achieved when “both the implementation process and the practice are effective”. Similarly, others have expressed concerns that even psychometrically sound instruments will fail to produce favorable outcomes if they are not properly implemented (Desmarais, Citation2017; Schlager, Citation2009).

Indeed, research has shown that agencies with better implementation quality (e.g., adherence to the risk assessment administration procedure) had significantly better results in terms of service allocation and risk management, such as fewer unnecessary restrictive placements and lower levels of supervision (Vincent, Guy, Gershenson, & McCabe, Citation2012; Vincent et al., Citation2016). In turn, research has shown that improved risk management is associated with reduced reoffending (Peterson-Badali et al., Citation2015). Thus, the quality of risk assessment implementation potentially mediates the effectiveness of risk assessment instruments in reducing recidivism. Hence, as Gottfredson and Moriarty (Citation2006, p. 195) stated: “risk assessment implementation is an area in which the nexus between research and practice must be taken seriously”. This paper aims to help bridge this gap by providing a practical example of a risk assessment implementation process.

Key ingredients for implementation

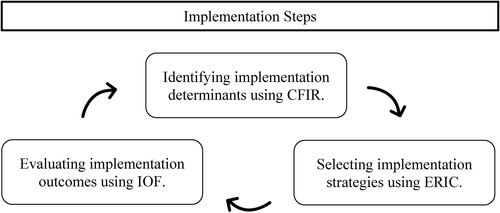

Most contemporary risk assessment instruments, so-called fourth-generation instruments, include user instructions on how to administer the instrument and how to use it for case management planning (Viljoen et al., Citation2018). Still, there is often limited guidance on how to effectively integrate the instrument into an organization and an organization’s decision-making process. This task has been recognized as daunting, for example, due to staff resistance or insufficient resources (Nonstad & Webster, Citation2011; Schlager, Citation2009). Fortunately, risk assessment implementation initiatives can draw from implementation science, a field that studies methods to promote the uptake of evidence-based practices into routine practice with the goal to improve services (Eccles & Mittman, Citation2006). In this field, three elements are identified as central to an implementation initiative: (1) factors that affect the implementation (implementation determinants); (2) strategies to deliver the implementation (implementation strategies); and (3) results of the implementation process (implementation outcomes; Peters et al., Citation2013).

These elements, or ‘ingredients’ (see ), can be applied to the implementation of risk assessment instruments. For example, Levin et al. (Citation2016) conducted a systematic review on the element of implementation determinants in structured risk assessment. Their review gave insight into the barriers and facilitators that are reported in risk assessment implementation papers and the ones that are neglected. In addition to assessing implementation determinants, several risk assessment publications have addressed implementation strategies, often framed as “lessons learned” (see for example Haque, Citation2016, Lantta et al., Citation2015, or Wright & Webster, Citation2011). Lastly, in 2020, Viljoen and Vincent provided an overview of the (scarce) risk assessment implementation research on the most commonly used implementation outcomes, while advocating for the use of these outcomes to monitor implementation success.

Figure 1. Key ingredients of a risk assessment implementation.

Note. CFIR = Consolidated framework of implementation research (Damschroder et al., Citation2009), ERIC = Expert recommendations for implementing change (Powell et al., Citation2015), IOF: Implementation outcomes framework (Proctor et al., Citation2011). Adapted from Risk assessment with the START:AV in Dutch secure youth care. From implementation to field evaluation, by De Beuf (Citation2022), p. 161.

Although these three ingredients (i.e., determinants, strategies, and outcomes) are important to address in an implementation process, they do not inform on how the implementation process should be structured and which sequence of implementation steps is recommended. There is a need for systematic descriptions of implementation processes to support the implementation of risk assessment instruments in clinical practice (Lantta, Citation2016).

The risk assessment implementation process

In the implementation literature, there exist many frameworks that provide practical guidance in the steps that need to be taken during an implementation process (Meyers et al., Citation2012). Few of them have been used to describe a risk assessment implementation process. One example is an implementation process described by Vojt et al. (Citation2013) who applied a four-step model for health-care organizational change (Golden, Citation2006) to implement risk assessment in a Scottish high secure psychiatric hospital. In a second implementation paper, Lantta et al. (Citation2015) used the Ottawa Model of Research Use (OMRU; Logan & Graham, Citation1998) to guide a risk assessment implementation in a Finnish forensic hospital. The OMRU is a six-step approach to implement innovations in clinical practice. Although these models are useful for some general guidance in the implementation process, they are not designed specifically for risk assessment implementations.

To date, there is only one implementation process model available that is specifically designed for risk assessment: the guidebook for implementation of risk assessment in juvenile justice by Vincent, Guy, and Grisso (Citation2012). This guidebook is developed based on experiences with and research into the implementation of various adolescent risk assessment instruments in American youth probation services, as well as extensive consultation with juvenile justice experts. In this guide, the implementation process is divided into eight implementation steps: (1) getting ready; (2) establishing buy-in; (3) selecting the instrument; (4) preparing policies and documents; (5) risk assessment training; (6) pilot implementation; (7) full implementation; and (8) efforts for sustainability. The guide also includes templates, evidence-based recommendations, and case examples of implementation initiatives. Currently, it is the most comprehensive implementation guide available that provides step-by-step guidance on how to integrate a risk assessment instrument in practice. It was, therefore, decided that this model would guide the risk assessment implementation initiative discussed in this paper.

The current paper

This paper includes a practice-based example of a risk assessment implementation process based on the abovementioned steps. Although Vincent et al.’s guidebook was originally developed for juvenile justice agencies, this article will demonstrate that it can be applied to implementation initiatives within secure residential youth care. More specifically, it was used to implement the Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability: Adolescent Version (START:AV; Viljoen et al., Citation2014) in a Dutch secure youth care service.

The overall aim of this paper is to provide other agencies and organizations with a detailed step-by-step illustration of the implementation process. Referring to , this paper will report on the “implementation steps” and does not intend to evaluate the other implementation elements (i.e., determinants, strategies, outcomes). These issues have been discussed elsewhere. For those who are interested, provides an overview of publications on these implementation elements specifically for the START:AV risk assessment instrument and its counterpart for adults (the START; Webster et al., Citation2006).

Table 1. List of publications on the implementation of the START or START:AV and the implementation elements they address.

Background

START:AV at a Dutch secure youth care service

In 2014, a Dutch secure youth care service decided to include evidence-based risk assessment in their routine practice. The START:AV was deemed an appropriate risk assessment instrument because of its emphasis on dynamic risk and protective factors which are particularly informative in a treatment setting. Moreover, the short-term nature of the instrument, with a recommended reassessment interval of three to six months, matched the setting’s four-month treatment cycle. Additionally, the START:AV addresses a wide spectrum of risk domains. That is, risk is assessed for violence to others, nonviolent reoffending, substance abuse, unauthorized absence, suicide, self-harm, victimization, and self-neglect. All these adverse outcomes are prevalent among adolescents admitted to Dutch residential youth care (Vermaes et al., Citation2014).

Setting and population

At the time of the implementation, in 2017, the service was one of 14 secure youth care facilities in the Netherlands. Secure youth care is a civil law measure issued by a juvenile judge for adolescents for whom less restrictive youth care has proven ineffective in addressing the youth’s needs and safety (Child & Youth Act, 2015). The service had 98 beds in three high-secure units and six medium secure units. About 140 new adolescents were admitted in 2017 and in total 219 youth received care (Baanders, Citation2018). The gender ratio was 48% boys to 52% girls and the average age was 15.6 years. The majority (90%) had multiple psychiatric diagnoses, with on average three diagnoses. When evaluating lifetime history of adverse outcomes among 129 newly admitted adolescents, it was found that 62% had used violence against others, 53% had engaged in nonviolent delinquent behavior, 64% had misused substances, and a large majority (85%) was familiar with truancy and/or running away from home. Many engaged in harmful behavior toward themselves: 25% had engaged in suicidal behavior, 35% in non-suicidal self-harm, 61% showed behavior that was considered health neglect. Victimization was also common in this sample: 82% had been victimized. The most common types of victimization were emotional and relational abuse (both 43%), but sexual abuse was also prevalent (40%) as well as neglect (28%) and physical abuse (26%).

The START:AV implementation process

The implementation process started early 2014 and in 2016, the risk assessment instrument was fully implemented. The follow-up of the implementation continued (at least) until 2021. In accordance with the implementation guidebook for risk assessment by Vincent, Guy, and Grisso (Citation2012), the implementation plan was organized in eight steps. Below, each step is described, followed by a summary of how the step was operationalized in the present setting.

Step 1: Getting ready

Implementation is more than providing training to staff: it starts with creating an optimal environment in which the risk assessment can operate effectively (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012). Since the preparation phase can have an important impact on subsequent steps, it is recommended to allocate sufficient time and resources in this phase.

Achieving system readiness

A first step in introducing a new evidence-based practice is to get support from different levels in the organization (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso Citation2012). At an administrative level, support is needed from those who are responsible for the service’s policy and regulations. At the management level, there should be readiness among directors and supervisors who will oversee the administration of the new instrument. At the staff level, readiness is needed among those who will administer the risk assessment instrument and who will be most affected by the new procedures.

The present setting

To enhance readiness within the organization, the risk assessment initiative was presented at the start of the implementation during a symposium organized for all employees working at the service. To increase and maintain interest in the project, updates about the project were regularly communicated via a digital newsletter.

Building leadership

Vincent et al. (Citation2012) suggest organizing two leadership committees: a steering committee and an implementation committee. The steering committee is responsible for the overarching decision-making and is the driving force behind the initiative. It should consist of representatives from all major stakeholders. For secure youth care services, this could be the board members of the service, a juvenile judge, a representative of the regional child welfare agencies, a representative of the municipalities that are financing the placements, a representative of staff who will administer the risk assessment, as well as a (risk assessment) expert who provides input based on knowledge and prior experiences. The second committee, the implementation committee, is responsible for the practical decision-making (e.g., selecting a risk assessment instrument). Their central task is to guide the implementation process, including the development and follow-up of the implementation plan. The implementation committee preferably consists of one or more high-ranking employees, an implementation coordinator, a prospective user of the risk assessment instrument, a risk assessment expert, and, if present, an in-house researcher. There can be overlap between the members of the implementation committee and the steering committee.

The present setting

Although there was no formal steering committee appointed, an informal constellation of leadership was available whenever the implementation initiative needed leadership, representation, and advocacy. This group consisted of a member of the board of directors, the general director, the director of treatment, and a university partner specialized in risk assessment. Chaired by the general director, they initiated the project and were in charge until the implementation committee was formed. The implementation committee consisted of an implementation coordinator, the director of treatment, a representative of the treatment coordinators who would administer the START:AV, and the service’s in-house researcher. Depending on the implementation phase, the risk assessment expert and representatives of other disciplines (e.g., middle management, group care workers) were asked to attend meetings and provide input. The overall decision-making approach of the implementation committee was as follows: (1) the implementation coordinator drafted a proposal (e.g., for protocols, templates) and presented this to the implementation committee, (2) the implementation committee provided feedback, (3) implementation coordinator adjusted the proposal accordingly and presented it at the monthly meeting of the treatment department, (4) feedback from the treatment coordinators was incorporated in the final version of the proposal, (5) the proposal was presented and approved in the next meeting of the implementation committee.

Identifying an implementation coordinator

Having someone who takes responsibility for the implementation process and adherence to the implementation plan is an important facilitator of implementation success (Damschroder et al., Citation2009). The implementation coordinator serves as contact person for all questions regarding the risk assessment practice, both from within and outside the organization. The appointment of an implementation coordinator is particularly relevant in the first years of the implementation. In their guidebook, Vincent et al. (Citation2012) included examples of job descriptions for the hiring of an implementation coordinator.

The present setting

In May 2014, an implementation coordinator was hired by the service. The coordinator had a background in forensic psychology and had been trained in the administration of several risk assessment instruments. In preparation of the implementation project, she completed the START:AV advanced training under the supervision of the original authors (Viljoen et al., Citation2014). This training included in-depth feedback on two training cases, in addition to the general START:AV workshop. A START:AV train-the-trainer course was not available.

The responsibilities of the implementation coordinator included: preparing the implementation plan, translating the START:AV into Dutch, developing training modules for different stakeholders (e.g., a two-day training for START:AV users), providing training, monitoring the implementation process, creating buy-in among internal and external stakeholders, developing protocols and templates, developing a digital START:AV format, establishing a START:AV database, monitoring the administration of the START:AV, assessing adherence to the user guide, providing coaching and booster sessions, etc. The implementation coordinator was appointed for 32 hours a week which was reduced to 10 hours a week after two years. In the remaining hours, she conducted doctoral research on the implementation project and the instrument (see De Beuf, Citation2022).

Creating an implementation plan

An implementation plan is a strategic plan that breaks down the process into smaller steps and describes what should be done when and by whom. It helps to monitor the process and, as a working plan, it can be adjusted and optimized according to the implementation progress (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012).

The present setting

The implementation plan was developed by the implementation coordinator in the first months of the project and included a rationale for the new practice as well as the expected implementation steps. The implementation tasks were divided into three major domains: preparation, execution, and evaluation. The implementation plan itself was not adjusted during the process. Instead, project adjustments were communicated via the meeting minutes of the implementation committee. After each meeting, the minutes were distributed to the committee members and addressed in the monthly meeting of the treatment coordinators. Furthermore, progress was periodically (i.e., in 2016, 2018, and 2019) assessed and described in comprehensive evaluation reports.

Preparing a data system

Data monitoring is essential to an implementation process as it provides feedback on the implementation progress (Peters et al., Citation2013). Together with an in-house researcher and/or risk assessment expert, the implementation committee can decide which data to gather and how (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012). Preferably, the risk assessment is embedded in the service’s digital data system or electronic client records to facilitate data-tracking.

The present setting

The implementation of the START:AV coincided with the development of a new electronic patient file. The implementation coordinator participated in meetings concerning this new system and advocated to incorporate a START:AV module in the digital platform. However, due to software restrictions, the interface was inconvenient and the START:AV module was quickly abandoned. Staff preferred using the MS Word forms. One year later, the development of an online START:AV form was outsourced to a nonprofit organization that hosted an internet-based questionnaire platform widely used by mental health and youth care providers in the Netherlands and Belgium. The development of this online START:AV was agreed upon by the original START:AV authors and documented in a written contract.

Step 2: Establishing stakeholder and staff buy-in

When introducing risk assessment in a clinical setting, it is essential to involve internal and external stakeholders and obtain their support for the new practice (Levin et al., Citation2016). It is important to identify key stakeholders and keep them informed throughout the process (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012).

The present setting

Secure youth care services have multiple external stakeholders such as municipalities, juvenile judges, child protection services, etc. Representatives of municipalities were informed through information brochures, presentations by the service’s account manager who visited the municipalities, and/or presentations by the implementation coordinator during visits organized at the service. Legal stakeholders (e.g., family lawyers, juvenile judges) were invited for a symposium about risk assessment and the START:AV, however, it proved difficult to reach them, in particular the juvenile judges. Due to a low response to the invitations, the symposium was canceled. This lack of engagement from legal stakeholders may be partially explained by them not being represented in the steering committee, as recommended by Vincent et al. (Citation2012). Having representatives of the legal professions taking part in the implementation process probably would have increased buy-in and participation. Nevertheless, whenever juvenile judges visited the organization, the implementation coordinator gave a presentation on the START:AV. Child protection services are also external stakeholders of the service. They are, for example, responsible for informing the court on the progress of the adolescent. They may use the information from the START:AV risk assessment to substantiate requests to end or prolong the mandated treatment. Child protection services were informed about the risk assessment through their communication with treatment coordinators who served as their contact person within the service. In general, information about the START:AV and its role within the service was available to all stakeholders and the interested public via the service’s website.

The internal stakeholders are group care workers (i.e., special trained social workers), treatment coordinators, and other professionals working with the youth such as teachers, therapists, drugs and family counselors, nurses, and managers. Some stakeholders were represented in the implementation committee, others were involved ad hoc. The implementation coordinator regularly communicated with them about the project via emails, newsletters and visits/presentations. For example, shortly before the full implementation, the implementation coordinator visited all treatment units to inform group care workers about the upcoming changes. Treatment coordinators, as future administrators of the instrument, were informed about the implementation process during their monthly meetings. They were involved in the majority of decisions since it would greatly influence their practice. Vincent et al. (Citation2012) focus on staff as internal stakeholders, however, other authors have addressed the importance (and typical absence) of service users as stakeholders in implementation initiatives (Levin et al., Citation2016). In the current setting, the adolescents were briefly informed about the risk assessment procedure during the admission interview. During meetings in which their treatment progress was discussed, they were informed about the findings on the START:AV. To involve the adolescents more in their risk assessment, a self-appraisal form was developed based on the START:AV. The aim of this worksheet was to stimulate discussion between the care providers and the youth about their risk and protective factors and gauge a youth’s insight into their risk for adverse outcomes. It was not used as a formal risk assessment.

Step 3: Selecting and preparing a risk assessment instrument

There are several criteria to consider when selecting a risk assessment instrument. Most importantly, it must meet the needs of the setting and be relevant to the service’s assessment question (e.g., population, risk outcomes; Heilbrun et al., Citation2021). Other considerations are: feasibility (e.g., difficulty, duration), availability of a user guide, the inclusion of evidence-based risk factors, associated costs, demonstrated adequate reliability and validity, availability of training, and whether the instrument comes with an interview script (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012).

The present setting

The risk assessment instrument was selected early in the implementation process by the informal steering committee. In what follows, the motivations for choosing the START:AV are discussed. Criteria 1 until 5 reflect the organization’s own arguments to select the START:AV as the most appropriate instrument based on the needs of the service and its population. The remaining criteria are additional considerations mentioned in the guidebook (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012).

Structured professional judgment instrument: There are two main approaches to structured risk assessment: the structured professional judgment (SPJ) approach and the actuarial approach (Douglas & Otto, Citation2021). A key difference between the approaches is how the final risk level is reached. Briefly, actuarial instruments rely on a fixed formula of risk factors to calculate a total score. Using group-level data, this score can be translated into a probability that an adverse outcome will occur. SPJ instruments leave more room for discretion of the professional. The administrators are not bound by an algorithm, instead, they decide how to weigh and combine the risk factors to reach a final judgment about the level of risk (Nicholls et al., Citation2016). For the present setting, an SPJ instrument was considered the most appropriate, because of this flexibility to individualize the assessment and reach an individualized risk outcome.

Multiple adverse outcomes: One of the assets of the START:AV is the assessment of multiple risk domains. It does not only include the risk of harm to others (i.e., violence, nonviolent offenses) but also the risk of harm to themselves (i.e., self-harm, suicide, victimization, health neglect, unauthorized absences, and substance abuse). As mentioned earlier, these outcomes are relevant to a secure youth care population.

Vulnerabilities and strengths: The START:AV is one of few instruments that has an equal number of risk and protective factors, therefore, providing a balanced picture of the adolescent. There is growing evidence for the relevance of assessing the protective factors in an adolescent’s life. Such factors (e.g., relationships with prosocial adults, commitment to school) have been empirically linked to lower risks and less recidivism (Shepherd et al., Citation2018).

Short-term risk assessment: Treatment within the service was evaluated every four months, therefore, the short-term approach of the START:AV aligned with the service’s cycle.

Intervention planning: The ultimate goal of the START:AV is to guide interventions (Viljoen et al., Citation2014). The user guide, therefore, elaborates on case formulation, scenario planning, intervention planning, and progress evaluation. This is particularly valuable for a treatment setting such as the present service, in which each treatment plan is tailored to the needs and strengths of a specific adolescent.

Feasibility: According to the user guide, the START:AV can be administered by mental health and legal professionals who are experienced in working with youth (e.g., case managers, psychologists, social workers, probation officers). Before using the START:AV in practice, the user guide should be closely studied and a minimum of three practice cases should be completed (Viljoen et al., Citation2014). The authors also strongly recommend completing a START:AV training (as was done here), but it is not mandatory. Information for the risk assessment is gathered through file review, interviews with the adolescent and their caregivers, observations in multiple contexts (e.g., home, school), psychological and psychiatric assessments, etc. Within the present service, this information was mostly readily available to the administrators. For new administrators with limited experience with the items and scoring criteria, the assessment (using the comprehensive rating sheet) was time-consuming, however, with increased experience and familiarity, the completion time decreased (De Beuf et al., Citation2019).

Availability of a user guide: The START:AV is accompanied by a comprehensive user guide that covers both the administration of the instrument as well as suggestions for its application to intervention planning (Viljoen et al., Citation2014). For the purpose of this implementation, the START:AV user guide and rating sheets were translated in Dutch (Viljoen et al., Citation2014, Citation2016). The implementation coordinator took the lead in the translation and two other translators, both risk assessment experts who are proficient in Dutch and English (Dr. de Ruiter and Dr. de Vogel), gave meticulously feedback on the translation. Back translation was deemed unfeasible given the size of the user guide. The translated version is recognized by the original authors as the official Dutch START:AV user guide. In addition to the user guide, the authors published a knowledge guide that details the empirical foundation of the instrument (Viljoen et al., Citation2016).

Availability of an interview script: Although the START:AV user guide does not include an interview script, example questions are provided for each item and adverse outcome. The implementation coordinator created a script based on these example questions and the service’s existing intake interview. Additionally, the implementation coordinator and university partner designed a ‘Cultural Identity Interview’ to aid practitioners in the conversation about culture and cultural connectedness, which is an optional START:AV item. The interview questions, included as appendix in the Dutch user guide, ask about the cultural identity of the youth and their caretakers, and how the adolescent’s situation is understood from a cultural perspective. The questions are based on the Cultural Interview developed by transcultural psychiatrist Hans Rohlof et al. (Citation2002).

Information on reliability and validity: At the time of the instrument selection, there were promising findings with respect to the reliability and validity of the START:AV pilot version. The psychometric properties of the START:AV within the present setting were evaluated at a later stage (see De Beuf, de Ruiter, et al., Citation2021; De Beuf, de Vogel, et al., Citation2021).

Availability of training: The original authors offered (online) workshops in the use of the START:AV as well as the advanced training mentioned earlier. With permission from the authors, the implementation coordinator developed a Dutch START:AV training.

Costs: Initial costs of adopting the START:AV included the purchase of user guides (including assessment forms) and the training of the implementation coordinator. More extensive implementation costs included the hiring of the implementation coordinator, hiring the risk assessment expert to give a workshop for treatment coordinators, paying START:AV administrators extra hours for taking part in an interrater reliability check, as well as the printing and publishing of START:AV information brochures and Dutch user guide. There is no insight into the total cost of the implementation.

Step 4: Preparing policies and essential documents

Implementing a risk assessment instrument means developing and introducing policies and forms that facilitate the integration of risk assessment into routine practice. Vincent, Guy, and Grisso (Citation2012) indicated that this is the most labor-intensive step in the implementation process and perhaps the most important step for an agency to reap the benefits of the new practice. In this step, the risk assessment practice is integrated into the standard practices of the organization. Integration can be enhanced by designing a protocol with guidelines for the assessment process, for translation to risk management, and for risk communication.

Developing a protocol on the administration and application of the Instrument

According to Vincent, Guy, and Grisso (Citation2012), this protocol should include: (1) user qualifications and training, (2) guidelines on instrument administration, (3) guidelines on risk communication, (4) recommendations for intervention planning, (5) a reassessment plan, and (6) a quality assurance plan.

The present setting

A protocol for the use of the START:AV within the present service detailed the arrangements about the what, who, when, and how of the START:AV administration. Additionally, the protocol included the list with potential interview questions, recommendations on how to support staff in the administration process, the adherence assessment form (see Step 6), risk formulation examples, as well as suggestions for increased integration. Because the START:AV protocol focused primarily on internal procedures, it did not include information on how to communicate the risk findings to external stakeholders. Recommendations for intervention planning based on the findings of the START:AV were not part of this protocol since they were included in the organization’s treatment manual. This manual (“Safe in Connection”) described the organization’s treatment approach and provided, amongst others, instructions on how to link the START:AV items to overarching treatment goals (e.g., strengthening adaptive coping strategies) and more concrete treatment targets (e.g., I discuss whether I have felt vulnerable today and how I dealt with it).

Prepare a computerized version of the START:AV

The risk assessment is preferably integrated into the electronic patient file to enhance efficiency and facilitate data monitoring (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012). There are two possible approaches: (1) use software offered by the developers of the risk assessment instrument (when available), or (2) develop your own software.

The present setting

As mentioned earlier, the START:AV was included in an online Dutch questionnaire platform. The service’s electronic patient file (EPF) system was linked to this software platform and completed START:AVs could be accessed through the EPF. For research purposes, data could be exported to Excel.

Communicating risk assessment information to stakeholders

Vincent, Guy, and Grisso (Citation2012) recommend adopting a standard template for communicating risk assessment information to judges, municipalities, and other stakeholders such as (child protection) caseworkers. Preferably, this document is developed with the input from these stakeholders to ensure it holds the information they need.

The present setting

Risk communication to external stakeholders was not actively included in the implementation process as the organization’s focus was mostly on the internal processes. That is, the risk assessment was mostly considered to serve the ongoing treatment, albeit it was also used to substantiate requests for discharge or treatment prolongment. There was no separate risk communication template because the risk formulation was incorporated in the treatment plan (in the section ‘dynamic risk profile’). Whenever the youth’s case was discussed in civil court (e.g., for prolongment of stay), the treatment plan was shared with the judge and the agencies involved (e.g., child welfare). The ‘dynamic risk profile’ included a summary of the final risk judgments (low, moderate, high) for each adverse outcome as well as a narrative of the key and critical items that were hypothesized to influence these risks. Furthermore, the dynamic risk profile described the time period and context in which the risk assessment was valid. In this setting, the standard was four months and the context was “as if the adolescent is about to be discharged into the community”, in accordance with the instruction for assessing risk in secured residential settings described in the user guide (Viljoen et al., Citation2014, p. 57). The treatment coordinators were instructed to specify the adverse outcomes in the risk formulation. For example, when describing a high risk of unauthorized absences, the expected behavior is specified (e.g., truancy, running away from home). Treatment coordinators were instructed to communicate the risk findings in a way that it would be easily understood by adolescents and their family. In practice, however, there was variability in the quality of the risk formulations.

Assigning supervision levels based on risk information

It is recommended that adolescents with higher risk levels receive more intensive interventions than adolescents with low risks. For the latter, no or low levels of supervision would suffice (see Risk-Need-Responsivity model; Bonta & Andrews, Citation2017). The service’s policy should specify how the risk level will be used for allocating supervision and interventions (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012).

The present setting

The level of supervision was included in the adolescent’s treatment plan (e.g., accompanied vs. unaccompanied leave) and, as recommended in the organization’s START:AV protocol, decisions about the level of security and supervision should be guided by the START:AV findings (i.e., matched with the adolescent’s risks and needs). In practice, however, it was not always possible to adhere to this guideline because of, for instance, the unavailability of beds or waitlists for therapy.

Matching services and interventions with adolescent’s risks and needs

In addition to addressing the level of risk, interventions should address the adolescent’s criminogenic needs (i.e., factors such as antisocial attitudes that increase risk) and should be compatible with a youth’s abilities and characteristics (e.g., intellectual disability, anxiety). A suggested approach is to create a service referral matrix that systematically matches identified needs with available interventions, taking problem intensity into account (Vincent et al., Citation2012). This can assist in developing individualized treatment plans. A service referral matrix can be developed by taking stock of the service’s interventions and subsequently linking them to different areas of need in the risk assessment (e.g., school, peers, caregivers). This exercise may also reveal whether certain types of interventions are lacking.

The present setting

The implementation coordinator conducted an inventory of the interventions available at the service. Based on this information, a concept for a service matrix was designed, however, the organization’s management decided not to use it for clinical practice. Instead, it was left at the treatment coordinators’ discretion to suggest interventions for adolescent, based on the START:AV items and based on the available services. As mentioned earlier, the START:AV items were linked to overall treatment goals as well as more specific daily targets. Nevertheless, a service matrix would have helped treatment coordinators in this decision-making. It would also have provided useful insight into whether the organization offered sufficient interventions to target the most common risks and needs of the admitted youth. This would have been especially relevant because the range of interventions provided at the service diminished over the years due to budget cuts and this potentially created shortcomings in service provision.

Establishing collaboration between disciplines involved in the treatment process

Professionals from various disciplines (e.g., therapists, social workers, drug counselors) provide information that is relevant to the risk assessment. Therefore, they should be involved in the implementation process and be included in policies and protocols (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012).

The present setting

Early in the process, the implementation coordinator approached all disciplines to inform them about the implementation process and to evaluate whether their current practices could be better tailored to the START:AV. Processes were adjusted for them to report their observations directly into the START:AV form. Especially group care workers were given a central role in documenting observations relevant to the START:AV items. Although the professionals individually provided input in the START:AV, they could discuss and elaborate upon their input during case conferences.

Creating a case management plan

For risk management purposes, it is crucial to include risk information in case management or treatment plans, for example, by describing which criminogenic needs will be addressed. It is also important to include mental health information, obtained from psychological and/or psychiatric assessments. This information is relevant for the risk and protective factors and it provides relevant directions as to how interventions should be provided. That is, interventions should take the adolescent’s abilities and vulnerabilities into account (Bonta & Andrews, Citation2017).

The present setting

The treatment plan was revised to include more risk assessment and management information. The section ‘dynamic risk profile’ was added and the section that detailed the treatment progress (‘treatment evaluation’) now included information on changes in risk and protective factors (when applicable). Furthermore, treatment goals in the plan were now based on the identified needs (i.e., key strengths and critical vulnerabilities).

Ongoing monitoring and reassessment

After the initial risk assessment at intake, repeated evaluations are required to follow up on (changes in) the level of risk and the presence of risk and protective factors. Given that adolescents are rapidly developing, frequent reassessments are necessary. The ‘shelf-life’ of risk assessments may be even shorter in residential settings where youths receive (mandatory) interventions and are also exposed to challenging events (e.g., incidents, use of coercion, availability of substances). Reassessment should be followed by an update of the treatment plan: Are the treatment goals and suggested interventions still relevant or should they be adjusted?

The present setting

Although the START:AV user guide recommends reassessing every three months, the service chose to reevaluate every four months, following the existing treatment cycle.

Step 5: Training

Vincent, Guy, and Grisso (Citation2012) recommended a train-the-trainer model for educating and training staff and stakeholders. In this model, there are at least two master trainers to limit the risk of discontinuance when one trainer falls ill or leaves the organization. Furthermore, research has shown that staff members who are trained by peer master trainers produce more reliable ratings than when trained by an expert (Vincent, Paiva-Salisbury, et al., Citation2012). This approach is suggested for the training of both instrument administrators and stakeholders.

The present setting

There was only one master trainer to provide the START:AV training. This choice made the implementation, and especially its sustainability, vulnerable. If that person was on leave or resigned, there was no back-up.

Training for START:AV administrators

Webster et al. (Citation2006) suggested that all clinical staff on the team should be trained in the use of the START to facilitate a multidisciplinary approach to risk assessment. Training should be divided into themes (risk assessment, risk management) with sufficient time between the training sessions to practice. Education on risk assessment should include theory, practice, and research findings, and learning effectiveness can be maximized by using case examples in interactive workshops with hands-on practice (Webster et al., Citation2006).

The present setting

The START:AV administrator training was organized for treatment coordinators and consisted of three parts:

Training part 1 (workshop): The first training included a general introduction to risk assessment and risk management, background information on the START:AV, and the rating guidelines for the items and adverse outcomes. During the training, a practice case was used for the participants to get some hands-on experience with the rating of the items and adverse outcomes. Participants were asked to read the case vignette in advance and make a first attempt at rating the items. This way the participants could familiarize themselves with (parts of) the user guide prior to the training which was reasoned to benefit the training (e.g., more time for more in-depth discussions).

Training part 2 (practice): The second part of the training involved rating two additional training cases that were designed by the implementation coordinator based on real cases. In addition, treatment coordinators practiced the START:AV during a brief interrater reliability study. Each treatment coordinator rated one to four cases, all former patients of the service. The implementation coordinator also rated these cases and provided individualized feedback to each rater. The implementation coordinator documented the most frequent errors and remarks in a feedback document, along with assessment tips and tricks. This document was available to all staff.

Training part 3 (workshop): The third part of the training focused on bridging the gap between risk assessment and risk management. The treatment coordinators learned how to use the instrument for case planning and decision-making. The training followed the risk management approach suggested in the START:AV user guide and included topics such as case formulation with critical vulnerabilities and key strengths, intervention planning, scenario planning, and additional goals for healthy development. In preparation for this training, treatment coordinators completed an intervention plan for one practice case, using the START:AV comprehensive rating form.

Ideally, a risk assessment training also includes training on how to interview adolescents for a risk assessment as well as a training on risk communication (Logan, Citation2013). Neither were part of the current training because of time considerations. While treatment coordinators received booster and coaching sessions at different stages of the implementation, supervised assessments of real cases in their caseload were not part of this initial training.

Training for stakeholders

The training for stakeholders should include the same topics as for administrators, albeit, more succinct and general. Topics should involve: general information on risk assessment and risk management, an overview of the instrument (including benefits and limitations), information on the administration (including instructions relevant to the particular service), and lastly, the role of the stakeholder in the assessment process (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012).

The present setting

In addition to the treatment coordinators, other professionals were involved in the risk assessment process, directly and indirectly. Internal Stakeholders who provided input for the START:AV were informed about the instrument and their role in the assessment process. For group care workers, a specialized workshop was developed that focused on 1) the rationale and application of the START:AV within the service and 2) the meaning of the items and which observations are relevant to document. Annual booster sessions were organized for group care workers. External Stakeholders were informed about the START:AV during visits to the youth care service or via information leaflets. The absence of a formal training for external stakeholders, such as judges or child welfare workers, is a missed opportunity. A better understanding of the research behind risk assessment would equip judges and other stakeholders with a more educated comprehension of the benefits and limitations of risk assessment, especially for their own practice (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012). Such information would likely facilitate a critical review of the risk information that is provided to them and help them formulate questions about the provided risk assessment.

Step 6: Piloting the implementation

It is recommended to run a pilot implementation before the risk assessment is fully implemented (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012). A pilot test can be completed on selected units or with selected administrators. The goal of pilot testing is to identify and fix flaws in the procedure, optimize templates, and start the data monitoring process. The pilot implementation should be evaluated by surveying administrators about the process and the reported challenges should be addressed. Such a pilot evaluation does not only provide valuable feedback, it may also increase staff buy-in. In addition, case audits can be done to assess the local interrater reliability and adherence to the protocol.

Interrater reliability and adherence assessments

The interrater reliability of local administrators can be assessed with practice cases or real cases. This exercise does not only provide insight into the local reliability, it also helps identifying administrators whose ratings differ consistently from others and who may benefit from additional training or coaching (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012). Furthermore, a case audit of completed assessments can inform about adherence. That is, the extent to which the risk assessments were completed according to the instructions in the user guide. Arguably, sufficient adherence is a precondition for a risk assessment instrument to reach its full potential, and providing feedback on the level of adherence is an important quality improvement strategy (De Beuf, de Vogel, et al., Citation2020). It is recommended to appoint a staff member who is responsible for these quality checks and who can periodically review case files (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012).

The present setting

Two interrater reliability checks were completed: one as part of the training (involving two practice cases; see earlier) and one as part of the pilot implementation with real cases.

The pilot implementation was conducted on two units with the aim of evaluating the administration process and the adjusted documents (e.g., the new treatment plan and the template for reporting on treatment progress) for five adolescents. The duration of each assessment was tracked and staff who participated in the pilot were asked about their experiences with the START:AV and the new documents in a two-page questionnaire. Findings of the pilot implementation were discussed with the implementation committee and treatment coordinators. An action plan was designed to address the feedback before fully implementing the START:AV.

Additionally, adherence to the user guide was assessed by a measure specifically developed for this: the START:AV Adherence Rating Scale (STARS; De Beuf et al., Citation2018). The first adherence check was completed when the START:AV was already fully implemented in the setting. Findings showed that the adherence rates differed for various parts of the START:AV: Sections that involved more argumentation showed poorer adherence than, for example, sections that involved the mere rating of items. The adherence results were used to inform the content of a START:AV booster session for treatment coordinators and, following this session, significantly better adherence results were found for those who participated (see De Beuf, de Vogel, et al., Citation2020).

Step 7: Full implementation

When the pilot implementation demonstrates sufficient quality and feasibility of the risk assessment procedures, the instrument can be fully implemented. When the risk assessment instrument is being used for the first time within a particular population, it is recommended to locally validate the instrument (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012). A validation study give an indication of the instrument’s predictive accuracy for the population of interest.

The present setting

The START:AV implementation took place at once for all units, since adolescents frequently transition from one unit to the other and each unit should offer the same approach. That said, the new practice was only implemented for newly admitted adolescents. Due to this decision, some teams did not use the START:AV until six months into the full implementation. As recommended by Vincent and colleagues, a validation study of the START:AV was conducted within this secure youth care setting. The results are published elsewhere (De Beuf, de Ruiter, et al., Citation2021).

Step 8: Sustainability

Once the instrument has been introduced within the service, continuing efforts are needed to maintain the integrity of the risk assessment practice. Enduring change can be made by promoting sustainability on multiple levels, ongoing data monitoring, organizing booster sessions, and regular interrater reliability checks (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012).

Promote sustainability at multiple levels

On a staff level, it is encouraged to continue to seek feedback, given the continuous pressure of a heavy workload. Based on periodic checks, the administration process can be fine-tuned. On an organizational level, it is recommended to reevaluate the usefulness of the instrument every few years, including an update of the literature. Outcome data can also provide valuable feedback on the efficiency of the risk assessment and management practices.

The present setting

A START:AV user survey was completed on several occasions and various implementation outcomes such as feasibility and acceptability were assessed (see De Beuf et al., Citation2019). Most staff members perceived the START:AV, especially the final risk judgments and strengths and vulnerabilities, as useful for treatment. Despite this, satisfaction with the instrument seemed to decrease over time, which was likely due to an increased workload that accompanied the new practice. In the first year, the completion rate was acceptable: 73% of required assessments were completed, however, there was some variability among the administrators (e.g., ranging from 29% to 100%). The measurement of these implementation outcomes provided valuable information and helped identifying areas for improvement. The implementation committee meetings continued, albeit at a lower frequency, to discuss issues that arose during the post-implementation phase.

Ongoing data monitoring

Vincent et al. (Citation2012) recommend involving a research department or university partner to assist with data monitoring. A research project can be linked to the implementation and instrument validation as well as to outcome monitoring (e.g., number of interventions received, level of supervision assigned). The research results cannot only improve practice, they can also increase commitment of staff when adequately communicated within the organization.

The present setting

As mentioned earlier, a doctoral research project in collaboration with Maastricht University was initiated. Implementation determinants and implementation outcomes were assessed, as well as the instrument’s interrater reliability and predictive validity. The project did not include outcome monitoring (e.g., number of incidents, treatment duration). Because multiple significant changes took place at the same time of the implementation, such as a new treatment approach and new legislation (new Child & Youth Act, 2015), it would have been challenging, if not impossible, to isolate the effect of the START:AV. Nevertheless, the in-house researcher published annual internal reports on the population in which she compared the averaged ratings of cohorts on the START:AV strengths, vulnerabilities, and adverse outcomes.

Organizing booster sessions

Booster training is crucial to avoid rater’s drift (i.e., deviation from scoring instructions over time; Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012). It is therefore advised to organize booster sessions, in the beginning at least every six months. A booster session ideally involves rating and discussing a practice case, followed by the practicing the risk formulation and risk management plan. In addition to formal training or coaching, it is recommended to identify ‘champions’ or ‘key users’ who can coach less-experienced staff on a daily basis (Webster et al., Citation2006).

The present setting

Booster sessions for treatment coordinators were organized, albeit, on an irregular basis (i.e., every two year). Individual coaching also took place: a case from the caseload was rated by a treatment coordinator and the implementation coordinator independently and the ratings were discussed in a one-on-one session. This was organized once prior to the departure of the implementation coordinator/master trainer. Once this opportunity of booster sessions was no longer available, it was recommended to treatment coordinators to organize a similar annual peer-review session amongst themselves. In addition, quality checks were completed once or twice a year to assess how well administrators adhered to the instructions in the user guide. For group care workers, the implementation coordinator attended a team meeting once a year to refresh their understanding of the START:AV and respond to issues they encountered. This frequency was decided based on feasibility and in agreement with the team managers.

Ongoing assessment of interrater reliability and adherence

As illustrated earlier, data on interrater reliability can be gathered through different initiatives. For example, data can be gathered during a booster session in which administrators independently rate a practice case (Vincent, Guy, & Grisso, Citation2012). Another possibility is to organize coaching sessions with individual administrators in which both the master trainer and the staff member rate a case from the real caseload. This approach provides input for both coaching and reliability checks.

The present setting

The interrater reliability study demonstrated that the reliability of the START:AV items was poor, both for strengths and vulnerabilities, and was lower than previously reported in non‐field studies (De Beuf, de Ruiter, et al., Citation2021). This finding is consistent with the majority of research on risk assessment in applied settings which has repeatedly shown that the interrater reliability is lower in field studies (Edens & Kelley, Citation2017). Nevertheless, moderate to good interrater reliability was found for the final risk judgments of most adverse outcomes, except for unauthorized absences which showed poor interrater reliability. This is an encouraging findings since the final risk judgments are the most important outcomes of the START:AV. When assessing prior history of adverse outcomes, the interrater reliability was moderate to good for most adverse outcomes, and with respect to recent history, the interrater reliability of the adverse outcomes was moderate. For a detailed discussion on the findings, see De Beuf, de Ruiter, et al., (Citation2021).

With respect to adherence, the implementation coordinator conducted quality checks twice a year on a randomly selected set of START:AV assessments. That is, per evaluator, four START:AVs were checked for adherence using the STARS. The results were communicated with the treatment coordinators and their supervisor, accompanied by general advice on how to improve adherence. The treatment coordinators with the lowest scores also received individualized feedback.

Reflections on the implementation process

When the implementation coordinator started this implementation process, she was well-educated in forensic risk assessment but had limited understanding of change processes and the implementation literature. Yet, with the guidance of the implementation steps of Vincent, Guy, and Grisso (Citation2012), she managed to structure and coordinate the project into an implementation that was successful in various ways. It was successful in terms of adoption, because, by 2021, all treatment coordinators in the service used the START:AV. Moreover, the practice became seemingly well-integrated since over 90% of the required risk assessments were completed. The implementation also seemed sustainable given that this percentage was maintained throughout the years (i.e., 95% in 2018, 95% in 2019, and 93% in 2020; De Beuf, Citation2021). However, in terms of satisfaction with the instrument and opinions about feasibility, the attitudes of the treatment coordinators fluctuated. The decrease in positive attitudes mentioned earlier was followed by an improvement in attitudes toward the instrument (De Beuf, de Ruiter, et al., Citation2021). This could be explained by the different stages people move through in a change process (e.g., Kubler-Ross change curve; Belyh, Citation2015) or simply by changes in staff over the years (see De Beuf et al., Citation2019).

That said, the experiences with the implementation steps of Vincent and colleagues were positive. All steps were adhered to in the implementation process, albeit, at times overlapping or interwoven. The largest discrepancy with the model is that the risk assessment instrument was selected prior to Step 1 and prior to the hiring of the implementation coordinator. At the time, the future administrators of the instrument (i.e., the treatment coordinators) were involved in the decision and the rationale for the selection was regularly restated, therefore, buy-in for the START:AV was maintained throughout the implementation. Beside this difference, the order of implementation steps as suggested by Vincent and colleagues was perceived as useful and appropriate. There have been no deliberate attempts to change the suggested sequence. The pace with which the setting moved through the different steps did, however, impede the implementation. Step 4 (prepare documents) and 5 (training) overlapped at a certain point, meaning that treatment coordinators received their first training before the protocols and adjusted documents were ready. Adding the pilot implementation phase to this, the treatment coordinators who did not participate in the pilot phase experienced a long interval between being trained and being able to apply the risk assessment instrument in practice. For some users, this interval was over one year. The timing of the steps in this particular implementation was therefore perceived as a barrier to the implementation (for more details on this and other barriers, see De Beuf, de Ruiter, et al., Citation2020).

Although the recommended steps were followed closely, the present implementation deviates from Vincent and colleagues in several ways. A main difference is the institution’s choice to have only one master trainer. Whereas the guidebook recommends at least two master trainers who are preferably peers, the present setting had one expert trainer (the implementation coordinator) who was the only one who could provide START:AV training to new staff and provide booster sessions to trained staff. This set-up made the continuation of the training vulnerable. For example, when the implementation coordinator left the institution, there was no one who could assign these responsibilities. Overall, having one person responsible for training and monitoring of the implementation creates a vulnerability for sustainability. Further into the implementation, it may be better to arrange processes in way that the position of the implementation coordinator becomes redundant and monitoring processes become part of other routine outcome monitoring.

The situation of the current implementation differed in other aspects from the guidebook. These differences have been mentioned throughout the paper: no official steering committee, the lack of engagement of judges and other external partners, no back-translation of the START:AV materials, no risk communication plan for extern stakeholders, no use of a service matrix, and no assessment of effectiveness outcomes of the risk assessment. They can be considered as limitations of the current risk assessment implementation.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to provide a step-by-step illustration of a risk assessment implementation process, using the implementation of the START:AV in a Dutch secure youth care service as example. The focus was therefore on the process itself rather than on implementation determinants, strategies, or outcomes. The implementation process was based on the eight steps suggested by Vincent, Guy, and Grisso (Citation2012). This guide was selected for its comprehensiveness and relevance to risk assessment and because it is based on research as well as experience with risk assessment implementation. This paper demonstrates that the steps in this guidebook are not only relevant to risk assessment implementation in juvenile justice, but are also applicable to implementations in residential youth care.

Author note

I confirm that that there are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report. This manuscript is written in memory of Dr. Jodi Viljoen.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Baanders, A. N. (2018). Doelgroeponderzoek. Een beschrijving van doelgroep en behandelresultaat in de periode 2012–2017 [Target population study. A description of target population and treatment results for the period 2012–2017] [Unpublished report]. OG Heldring Institution.

- Belyh, A. (2015). Understanding the Kubler-Ross change curve. Cleverism. https://www.cleverism.com/understanding-kubler-ross-change-curve/

- Bonta, J., & Andrews, D. A. (2017). The psychology of criminal conduct (6th ed.). Routledge.

- Child and Youth Act, § 6.1.2. (2015). https://wetten.overheid.nl/jci1.3:c:BWBR0034925&hoofdstuk=6¶graaf=6.1&artikel=6.1.2&z=2020-07-01&g=2020-07-01

- Crocker, A. G., Braithwaite, E., Laferrière, D., Gagnon, D., Venegas, C., & Jenkins, T. (2011). START changing practice: Implementing a risk assessment and management tool in a civil psychiatric setting. The International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 10(1), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2011.553146

- Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science : IS, 4, 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

- De Beuf, T. L. F., de Ruiter, C., & de Vogel, V. (2020). Staff perceptions on the implementation of structured risk assessment: Identifying barriers and facilitators in a residential youth care setting. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 19(3), 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2020.1756994

- De Beuf, T. L. F., de Ruiter, C., Edens, J. F., & de Vogel, V. (2021). Taking ‘the boss’ into the real world: Field interrater reliability of the START:AV. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 39(1), 123–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2503

- De Beuf, T. L. F., de Vogel, V., Broers, N. J., & de Ruiter, C. (2021). Prospective field validation of the START:AV in a Dutch secure youth care sample. Assessment. Advance Online Publication, https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911211063228

- De Beuf, T. L. F., de Vogel, V., & de Ruiter, C. (2019). Implementing the START:AV in a Dutch residential youth facility: Outcomes of success. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 5(2), 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000193

- De Beuf, T. L. F., de Vogel, V., & de Ruiter, C. (2020). Adherence to structured risk assessment: Development and preliminary evaluation of an adherence scale for the START:AV. Journal of Forensic Psychology: Research and Practice, 20(5), 413–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/24732850.2020.1756676

- De Beuf, T. L. F. (2021, June 16). START:AV in The Netherlands: In secure residential youth care. In T. L. F. De Beuf (Chair), Implementation of the START:AV across Europe [Symposium]. Virtual annual conference of the International Association of Forensic Mental Health Services.

- De Beuf, T. L. F. (2022). Risk assessment with the START:AV in Dutch secure youth care. From implementation to field evaluation [dissertation]. Maastricht University. https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20220404td

- De Beuf, T. L. F., Gradussen, M. J. A., de Vogel, V., & de Ruiter, C. (2018). START:AV Adherence Rating Scale (STARS). OG Heldringstichting.

- Desmarais, S. L. (2017). Commentary: Risk assessment in the age of evidence-based practice and policy. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 16(1), 18–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2016.1266422

- Douglas, K. S. & Otto, R. K. (Eds.). (2021). Handbook of violence risk assessment (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Doyle, M., Lewis, G., & Brisbane, M. (2008). Implementing the Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START) in a forensic mental health service. Psychiatric Bulletin, 32, 406–408. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.108.019794

- Eccles, M. P., & Mittman, B. S. (2006). Welcome to implementation science [Editorial]. Implementation Science, 1, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-1-1

- Edens, J. F., & Kelley, S. E. (2017). “Meet the new boss. Same as the old boss”: A commentary on Williams, Wormith, Bonta, and Sitarenios (2017). International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 16, 23–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2016.1268221

- Golden, B. (2006). Transforming healthcare organizations. Healthcare Quarterly (Toronto, Ont.), 10, 10–14. https://doi.org/10.12927/hcq.18490

- Gottfredson, S. D., & Moriarty, L. J. (2006). Statistical risk assessment: Old problems and new applications. Crime & Delinquency, 52(1), 178–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128705281748

- Haque, Q. (2016). Implementation of violence risk assessment instruments in mental healthcare settings. In J. P. Singh, S. Bjorkly, & S. Fazel (Eds.), International perspectives on violence risk assessment (pp. 40–52). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199386291.001.0001

- Heilbrun, K., Yasuhara, K., Shah, S., & Locklair, B. (2021). Approaches to violence risk assessment. Overview, critical analysis, and future directions. In K. S. Douglas, & R. K. Otto (Eds.), Handbook of violence risk assessment (2nd ed., pp. 3–27). Routledge.

- Kroppan, E., Nesset, M. B., Nonstad, K., & Pedersen, T. W. (2011). Implementation of the Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START) in a forensic high-secure unit. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 10(1), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2011.552368

- Kroppan, E., Nonstad, K., Iversen, R. B., & Søndenaa, E. (2017). Implementation of the Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability over two phases. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 10, 321–326. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S133514

- Lantta, T., Daffern, M., Kontio, R., & Välimäki, M. (2015). Implementing the dynamic appraisal of situational aggression in mental health units. Clinical Nurse Specialist CNS, 29(4), 230–243. https://doi.org/10.1097/NUR.0000000000000140

- Lantta, T. (2016). Evidence-based violence risk assessment in psychiatric inpatient care: An implementation study [dissertation]. University of Turku. https://www.utupub.fi/handle/10024/125695

- Levin, S. K., Nilsen, P., Bendtsen, P., & Bulow, P. (2016). Structured risk assessment instruments: A systematic review of implementation determinants. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 23(4), 602–628. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2015.1084661

- Levin, S. K., Nilsen, P., Bendtsen, P., & Bülow, P. (2018). Staff perceptions of facilitators and barriers to the use of a short- term risk assessment instrument in forensic psychiatry. Journal of Forensic Psychology Research and Practice, 18(3), 199–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/24732850.2018.1466260

- Logan, C. (2013). Risk assessment: Specialist interviewing skills for forensic practitioners. In C. Logan & L. Johnstone (Eds.), Managing clinical risk: A guide to effective practice (pp. 259–292). Routledge.

- Logan, J., & Graham, I. (1998). Toward a comprehensive interdisciplinary model of health care research use. Science Communication, 20(2), 227–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547098020002004

- Meyers, D. C., Durlak, J. A., & Wandersman, A. (2012). The quality implementation framework: a synthesis of critical steps in the implementation process. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(3–4), 462–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9522-x

- Müller-Isberner, R., Born, P., Eucker, S., & Eusterschulte, B. (2017). Implementation of evidence-based practices in forensic mental health services. In R. Roesch & A. N. Cook (Eds.), Handbook of forensic mental health services (pp. 443–469). Routledge.

- Nicholls, T. L., Petersen, K. L., & Pritchard, M. M. (2016). Comparing preferences for actuarial versus structured professional judgment violence risk assessment measures across five continents: To what extent is practice keeping pace with science? In J. P. Singh, S. Bjørkly & S. Fazel (Eds.), International perspectives on violence risk assessment (pp.127–149). Oxford University Press.

- Nonstad, K., & Webster, C. D. (2011). How to fail the implementation of a risk assessment scheme or any other new procedure in your organization. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(1), 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01076.x

- Peters, D. H., Tran, N. T., & Adam, T. (2013). Implementation research in health. A practical guide. Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization.

- Peterson-Badali, M., Skilling, T., & Haqanee, Z. (2015). Implementation of risk assessment in case management for youth in the justice system. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 42, 304–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854814549595

- Powell, B. J., Waltz, T. J., Chinman, M. J., Damschroder, L. J., Smith, J. L., Matthieu, M. M., Proctor, E. K., & Kirchner, J. E. (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science : IS, 10, 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1

- Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., Griffey, R., & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38(2), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

- Rohlof, H., Levy, N., Sassen, L., & Helmich, S. (2002). The cultural interview. https://rohlof.nl/transcultural-psychiatry/the-cultural-interview/?lang=en

- Schlager, M. D. (2009). The organizational politics of implementing risk assessment instruments in community corrections. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 25(4), 412–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986209344555

- Shepherd, S. M., Strand, S., Viljoen, J. L., & Daffern, M. (2018). Evaluating the utility of ‘strength’ items when assessing the risk of young offenders. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 29(4), 597–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2018.1425474

- Sher, M. A., & Gralton, E. (2014). Implementation of the START:AV in a secure adolescent service. Journal of Forensic Practice, 16, 184–193. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFP-04-2013-0021

- Vermaes, I., Konijn, C., Jambroes, T., & Nijhof, K. (2014). Statische en dynamische kenmerken van jeugdigen in JeugdzorgPlus: Een systematische review [Static and dynamic characteristics of youth in secured residential care: A systematic review]. Orthopedagogiek: Onderzoek En Praktijk, 53(6), 278–292.

- Viljoen, J. L., Cochrane, D. M., & Jonnson, M. R. (2018). Do risk assessment tools help manage and reduce risk of reoffending? A systematic review. Law and Human Behavior, 42(3), 181–214. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000280

- Viljoen, J. L., & Vincent, G. M. (2020). Risk assessments for violence and reoffending: Implementation and impact on risk management. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, e12378. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12378

- Viljoen, J. L., Nicholls, T. L., Cruise, K. R., Desmarais, S. L., & Webster, C. D. with contributions by Douglas-Beneteau, J. (2014). J. Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability: Adolescent Version (START:AV) – User guide. Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute.

- Viljoen, J. L., Nicholls, T. L., Cruise, K. R., Desmarais, S. L., & Webster, C. D. Douglas-Beneteau, J. (2016). START:AV handleiding, short-term assessment of risk and treatability: Adolescenten versie (Tamara L. F. De Beuf, Corine de Ruiter, Vivienne de Vogel, Eds. and Trans.). [Dutch translation]

- Viljoen, J. L., Nicholls, T. L., Cruise, K. R., Douglas-Beneteau, J., Desmarais, S. L., Barone, C. C., Petersen, K., Morin, S., & Webster, C. D. (2016). START:AV knowledge guide. A research compendium on the START:AV Strength and Vulnerability items. Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute. http://www.sfu.ca/psyc/faculty/viljoen/STARTGuide.pdf