Abstract

Indigenous individuals are vastly over-represented among people incarcerated in Canada. We collected extensive clinical information and outcome data from Review Board (RB) files and obtained lifetime criminal records for 1800 individuals found Not Criminally Responsible on Account of Mental Disorder (NCRMD) in BC (n = 222), ON (n = 484), and QC (n = 1094). Indigenous and non-Indigenous people were compared on (a) socio-demographic, clinical, and criminal histories; (b) index offenses; (c) processing by the RB; and (d) recidivism. Compared to published rates of the disproportionate incarceration of Indigenous people in prisons in Canada (30%), just 3.9% of people in custody with an NCRMD finding were identified as Indigenous. Compared to non-Indigenous people, Indigenous people had higher rates of substance use disorders, personality disorders, and lower rates of mood disorders at verdict and came from low population density neighborhoods but high population density homes. Indigenous individuals were detained in custody longer and remained under supervision longer than non-Indigenous individuals but recidivated at similar rates. Criminal histories, mental health characteristics, and index offenses of Indigenous people found NCRMD were similar to non-Indigenous people found NCRMD. Further research is required to determine if seriously mentally ill Indigenous people who come into contact with the justice system are considered for the NCRMD defense similarly to non-Indigenous people and to explore why Indigenous individuals receive more restrictive dispositions, yet time to reoffending is similar.

Introduction

IndigenousFootnote1 people comprise a small proportion of the Canadian population; yet they are found in large numbers across the criminal justice system (Department of Justice Canada, Citation2019a, Citation2019c). Clark (Citation2019) concluded that Indigenous adults represented 26% of individuals admitted to provincial/territorial prisons (i.e., people with sentences of 2 years less a day) and 25% of the federal prison population (people with sentences >2 years) in 2014/2015. As such, Indigenous people’s representation was 9 times higher in prison populations compared to their representation within the adult general population (3%) (Clark, Citation2019). Data show this trend has continued and in fact the disparity between Indigenous individuals and non-Indigenous individuals has only grown. Overall, in the past decade alone, the total Indigenous correctional population has grown by 40.8% (community and custody combined). For example, there has been a 22.5% increase in the number of Indigenous people in Canadian federal custody since 2012, while the federal prison population overall has decreased by 16.5% (Office of the Correctional Investigator, Citation2022). In 2022, the Office of the Correctional Investigator reported that Indigenous people, representing about 5% of Canada’s adult population, had surpassed 30% of the federally incarcerated population. Particularly staggering, the proportion of Indigenous women now approaches 50% of all female federally incarcerated women in Canada (Office of the Correctional Investigator, Citation2022).

The disproportionate incarceration of Indigenous people reflects Canada’s long-standing and pervasive history of colonialism, assimilation, and marginalization of Indigenous people which did immeasurable harm to multiple generations of Indigenous people (Clark, Citation2019; Government of Canada, Citation2010; Marshall & Gallant, Citation2012). Briefly, colonialism refers to a complex, systematic, and widespread government- and church- sanctioned genocide of Indigenous people, Indigenous identity, and the Indigenous way of life (Clark, Citation2019). In particular, the residential school system and the Sixties Scoop alike removed Indigenous children from their families, communities, and culture. The residential school system was intended to remove children from their families, traditions, and cultures in order to oppress and assimilate them into the dominant culture and “kill the Indian in the child” (p. 7). These objectives were based on the assumption that Indigenous cultures and spiritual beliefs were inferior (Hanson et al., Citation2020). Children as young as four were removed from their homes and placed in government sponsored, mostly Christian-run schools. Residential schools are widely acknowledged to have resulted in thousands of children suffering neglect (e.g., starvation, lack of access to medical care) and abuse (e.g., electrocution, physical and sexual assaults), the ripples of which continue, reflected in deep and pervasive mental health and psychosocial problems (Government of Canada, Citation2010; Hanson et al., Citation2020; Marshall & Gallant, Citation2012). Although the devastating impact of residential schools began to be realized in the 1950s and 1960s and they started to get phased out, the last residential school in Canada did not close until 1996. Moreover, the practice of extinguishing the Indigenous way of life and removing children from their families very much persisted. Specifically, the Sixties Scoop refers to a non-explicit government policy to remove Indigenous children from their families and generally place them into middle-class Euro-Canadian families (Sixties Scoop, n.d. (ubc.ca)). Indigenous children comprised just 1% of children placed in care in British Columbia in 1951 (N = 29); by 1964, the proportion had grown to 34% (N = 1,466).

The residential school system and the broader history of colonialism across Canada has repeatedly been demonstrated to be directly associated with a plethora of social determinants of health and risk factors associated with poor mental health and criminal justice involvement among Indigenous people. These include high rates of substance use needs; disconnection from cultures and languages and family/social support; physical, emotional, and sexual victimization and violence; poverty, homelessness, poor housing and food insecurity. These are reflected in widespread trauma and intergenerational loss—and all of these factors are associated with disproportionate justice system involvement for Indigenous people (House of Commons Canada, Citation2018; National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG), Citation2019; Office of the Correctional Investigator, Citation2013). Moreover, these circumstances are not unique to Canada. Ogilvie et al. (Citation2022) for instance, reported that people in Australia Indigenous people were overrepresented in both the health and criminal justice systems and had higher rates across diverse adverse outcomes (e.g., entered the systems at a younger age, were more likely to be convicted, and more often received a supervised or a custodial sentence).

Contrary to the perception that the societal-wide effects of colonialism are in Canada’s distant past, many people who were directly affected-- and their immediate families and descendants-- now carry the intergenerational trauma and wide-ranging mental, physical, social, and economic burdens of that trauma (Hanson et al., Citation2020; House of Commons Canada, Citation2018; MMIWG, Citation2019). The relevance and importance of considering the historical context of Indigenous experiences and subsequent contact with the justice system was recognized in the landmark Gladue (Citation1999) case (Department of Justice Canada, Citation2019c; R v Gladue, Citation1999). In the Canadian criminal justice system, judges must now consider the individual circumstances of the accused in determining a fair and fit sentence. Gladue principles are a way to ensure judges consider the unique circumstances and experiences of Indigenous people. These unique circumstances include the challenges of colonialism that an Indigenous accused, their family, and community faced, and continue to affect them today (https://aboriginal.legalaid.bc.ca/). The courts have also determined that those principles are also relevant to Review Boards (Department of Justice Canada, Citation2019c). In Ontario, the Sim (Citation2005) case was the first to conclude that Gladue principles apply to Review Board hearings regarding people found Not Criminally Responsible on Account of Mental Disorder (NCRMD). This became further entrenched in law in 2012, follow the Ipeelee case, in which the Supreme Court continued to move toward an integration of the social, economic, and political circumstances as a central consideration in determining criminal responsibility and appropriate dispositions (Department of Justice Canada, Citation2019c).

An accused person deemed NCRMD has been found to have committed the act; thus, it is not an acquittal but rather a unique third option. where the accused was so ill as to not have understood the nature and quality of their actions or omissions, but the public may still require protection from future dangerous behavior (Criminal Code, R.S.C., Citation1985, c. C-46, s. 16(1)). The mandate of the Review Board is therefore unique from the principles and philosophies that guide the larger criminal justice system. Rather than being intended to deter and punish, the RB is required to make disposition determinations that reflect the risk the individual represents to the safety of the public and the therapeutic needs of the person (Criminal Code, R.S.C., Citation1985, c. C-46; Winko v. British Columbia (Forensic Psychiatric Institute), Citation1999). It is important to be mindful that while the intention is not to punish, an NCRMD finding is far from being a “get out of jail free card” (Martin et al., Citation2022). Martin et al. (Citation2022) demonstrated that people found NCRMD are 3.8 times (95% CI 3.4–4.3) more likely to be detained in custody than people convicted of similar offenses and 2.9 times (95% CI 2.6–3.1) and 4.8 times (95% CI 4.5–5.3) less likely to be released from supervision and from custody, respectively.

We agree with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that we need to do more to address historical trauma, racism, and poverty. Colonialism has left a legacy of higher rates of addiction and mental health issues (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Citation2015). Nelson and Wilson (Citation2017) contend that we need to understand colonialism fully in order to understand mental illness in Indigenous people and this is why Gladue should be included in Review Board processes. If Gladue principles are not included, then the Review Boards are not “recognizing and understanding the impact of colonialism and its contribution to over-incarceration” (McCleery, Citation2021, p. 189). Reflecting Gladue, decision makers like the courts and RBs ought to take historic and current discrimination into account; the expectation would be that an accused of Indigenous descent should have a similar, if not greater probability of being assessed, and found NCRMD, not less.

Despite challenges, research suggests the Canadian forensic system is quite successful at meeting its mandate to foster recovery and community reintegration, while prioritizing public safety. Salem et al. (Citation2015) examined people released on a conditional discharge from forensic hospitals with and without supportive housing in Québec. Using survival analyses the authors demonstrated that people with supportive housing were significantly more likely to be referred to a hospital (1.4 times) and 2.5 times less likely to redivate than people without supportive housing. Of particular importance, people in supportive housing were significantly less likely to perpetrate an offense against a person (3 times) than people released to independent living (Salem et al., Citation2015). Research has also demonstrated that people released from forensic services are significantly less likely to reoffend than people who are convicted of the same types of offenses and incarcerated (Charette et al., Citation2015). In sum, research suggests that a person living with severe mental illness may be more likely to achieve better mental health and criminogenic outcomes, and to present less risk of harm to the community, if they are processed through the forensic system than if they are processed through the prison system in Canada.

Given the objective of the NCRMD legislation is to protect the rights of people with severe mental disorders and mounting evidence that the forensic system is able to achieve superior outcomes with mentally ill individuals with criminal justice involvement, both with respect to the quality of life of the individual and the safety of the public, it is important to examine the extent to which “access to” and “processing within” the forensic system in Canada is equitable. This seems particularly relevant to Indigenous people in Canada given that Indigenous people are incarcerated at much higher rates than non-Indigenous people, and also because they experience harsher circumstances while in custody and worse outcomes post-release (e.g., Clark, Citation2019; Office of the Correctional Investigator, Citation2022).

There is very little research examining the extent to which Indigenous individuals are represented among NCRMD accused (people raising the “insanity” defense) and the processing (e.g., duration of time in custody) and outcomes (e.g., recidvidsm) of Indigenous persons found not criminally responsible. Thus, we had four objectives: (1) Estimate what proportion of the NCRMD population in Canada is Indigenous and compare Indigenous and non-Indigenous persons found NCRMD with respect to: (1) socio-demographic characteristics, mental health histories, and criminal histories; (2) Examine the characteristics of the index offense; (3) Evaluate how Indigenous vs. non-Indigenous persons found NCRMD are managed by the RB system; and (4) Compare and contrast the rates of recidivism between the two groups.

Methods

Design and indigenous research considerations

This study drew upon data from the National Trajectory Project, a retrospective longitudinal file-based study. A comprehensive description of the methods for the full study was published (Crocker et al., Citation2015b) and additional information is available at ntp-ptn.org. This study received ethics and operational approvals from all involved institutions and settings. Given the data was collected more than a decade ago, no Indigenous community partnered research was completed, as this was not common practice at the time. To address this limitation, an Indigenous coauthor (N.M.) was invited to participate on this article to ensure that an Indigenous perspective was included. In our current and future research projects, we ensure that Indigenous people are copartners in research involving Indigenous participants.

Setting and participants

We collected data from the forensic mental health services of Canada’s three most populous provinces. Participants were all people who were found NCRMD in Québec, Ontario, and BC between May, 2000, and April, 2005, and followed until December 2008. Given the large number of NCRMD findings in Québec, a random sample of NCRMD verdicts between May 1, 2001, and April 30, 2005, stratified by judicial districts, was selected (n = 1089). The Ontario sample was comprised of all adults with an NCRMD verdict between January 1, 2002, and April 30, 2005 (n = 483). The BC sample comprised all NCRMD accused registered between May 1, 2001 and April 30, 2005 (n = 222). The Winko decision, which could have influenced the characteristics of people found NCRMD and RB decisions about absolute discharges (Desmarais & Hucker, Citation2005) was used to determine our start date for sampling. The study end date allowed for a minimum of a three year follow-up for all cases, up to a maximum of eight years. The data was collected almost exclusively from the Review Board offices’ records.

Individuals identified as Indigenous

Our study was file based, thus, we were not able to ask individuals about their self-identification as Indigenous or otherwise. Thus, two indicators of ethnicity were used: First, if it was mentioned in the file, by a judge or a clinician, at any point in time, that the individual was of Indigenous descent, we identified the person as Indigenous. Using this strategy, 2.9% of the sample (n = 53) was identified as Indigenous. Second, the files included home addresses. These addresses were geo-located and, using 2006 Census subdivision types from Statistics Canada, we were able to determine if individuals were living on a reserve at the time of the index offense or during their follow up. The median proportion of Indigenous people in census tracts identified as a reserve was 98%. In our sample, 20 individuals were living on a reserve at the time of the index offense, and 13 individuals at least at one point during their follow up. Combining these two non-exclusive indicators, we identified a total of 70 individuals as Indigenous (3.9%).

Procedures

For each individual found NCRMD we identified an index offense; for people with multiple NCRMD findings we used the earliest NCRMD finding in the sampling period. Review Board files were used to collect data from five years prior to the index verdict and then coded forward until December 31, 2008. The RB files generally contained the psychiatrist’s initial assessment to inform the court regarding the NCRMD finding as well as any expert reports (psychiatrist and larger interdisciplinary care team reports) submitted to the RB for the annual disposition hearings. They also held the disposition determination and rationale from the RB. In British Columbia, RB files dated prior to November 2001 had been destroyed; thus, the 7 cases from May 2000 until October 31, 2001, were accessed from files obtained at the British Columbia Forensic Psychiatric Hospital. The hospital files generally contain the same reports and documents found in the BC RB files. Research assistants completed these 7 cases last and were instructed to code only from the file content that would have been generally found in RB files, to maintain comparability with the other BC cases and the other provinces.

Measures and sources of information

Study protocol

An extensive purpose-built study protocol that captured five categories of information was developed for the larger National Trajectory Project (see Crocker et al., Citation2014; Citation2015b; Wilson et al., Citation2016). We utilized two primary sources of information, the RB files (which contained the expert reports to the courts and the RBs as well as the records of the RB’s decisions and rationale) and the person’s criminal record. Socio-demographic traits (e.g., age, sex, marital status, housing), clinical characteristics (e.g., psychiatric symptoms at the time of the offense; diagnosis at verdict and at each subsequent hearing), processing (e.g., RB disposition and rationale) and contextual variables (e.g., date of verdict, admission to hospital, first conditional discharge, re-hospitalizations, absolute discharge) and details of risk assessments were coded from the RB files. Criminal history (e.g., offenses leading to the index NCRMD verdict, past convictions, or NCRMD verdicts) and recidivism were collected from national criminal records, we also coded prior NCRMD verdicts from RB files given those findings are not consistently available in criminal justice records.

Neighborhood characteristics

We examined three characteristics of the neighborhood where the individual lived at the time of the index offense. Neighborhoods were first characterized by their deprivation according to the two dimensions of the Pampalon index: Material and social deprivation (Pampalon et al., Citation2009; Pampalon & Raymond, Citation2003). These indexes are the result of a principal component analysis based on indicators from the Canadian census, leading to two dimensions (see Pampalon et al., Citation2009 for details). Material deprivation is based on income, level of education, and employment. Social deprivation is based on percentage of people living alone, percentage living in single-parent homes, and percentage who reside in divorced-separated homes. The deprivation indexes are on a z-score scale, 0 is the average Canadian level, 1 is one standard deviation over the average (more deprivation) and −1 is one standard deviation under the average (less deprivation). Our final neighborhood characteristic at the index offense was a measure of rurality/urbanicity examining population density by dividing the population of the Forward Sortation Area from Statistics Canada (Citation2006) census by the surface area (inhabitants/km2; Statistics Canada, Citation2006).

Criminal history, index offense, and recidivism

We obtained lifetime criminal records through the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), which receives data from all police services across the country. This provided both lifetime criminal history and recidivism data. Descriptions of the offenses were coded using the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey violation codes. A severity score was assigned to each offense using the Crime Severity Index, which is based on average sentence lengths in Canada (Wallace et al., Citation2009). Administrative data pertaining to outcomes (custody, supervision, recidivism) was available until December 31, 2008 (M = 5.72 years, SD = 1.48) (Crocker et al., Citation2015a). Additional details about offenses were obtained from clinical documents (e.g., relationship to victim) in the RB files.

Analyses

Weights were used to ensure the regional representativeness of the Québec sample (Crocker et al., Citation2015b). We conducted survival analysis to examine the duration of time people were in hospital, under the supervision of the RB, and time to any reoffending. Courts and RB dispositions were used to estimate the time each individual spent in detention or on conditional discharge up to absolute discharge or end of observation, whichever came first. Survival curves were examined using the Kaplan–Meier method and Cox proportional hazard regression models (Cox, Citation1972). Survival curves and proportional hazard models were performed using R, version 3.0.2 and the survival package (R Development Core Team, Citation2010). Given the large sample size, p-values could easily become small even though the observed group differences are not clinically or practically significant (Hojat & Xu, Citation2004; Stamatis, Citation2003). For this reason, we report effect sizes, such as the number of standard deviations between the mean for group A and the mean for group B. An effect size of 0.5 to 0.8 or greater is usually considered large. A correlation value of φ = 0.1 is considered to be a small effect, 0.3 a medium effect, and 0.5 a large effect.

Results

Indigenous representation among people found NCRMD

Of the total sample of 1800 people found NCRMD over the study period, just 3.9% were identified as Indigenous. Consistent with the population distribution in Canada, Indigenous representation differed across the three provinces; Québec had the lowest proportion (1.9%), BC had the highest (9.5%) and in Ontario, Indigenous people comprised 6.1% of people found NCRMD.

Characteristics of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people found NCRMD

Socio-demographics

Indigenous people found NCRMD were substantially younger at the time of the index offense than non-Indigenous people. Substantially fewer Indigenous individuals as compared to non-Indigenous individuals had completed a high school diploma. There was no difference in the representation of women among the Indigenous and non-Indigenous samples. Indigenous people found NCRMD were no more or less likely to be in a romantic relationship than non-Indigenous people found NCRMD ().

Table 1. Characteristics of people found NCRMD who were and were not identified as Indigenous.

Neighborhood characteristics

As can be seen in , Indigenous people lived in closer proximity to other Indigenous people than did their non-Indigenous counterparts. Specifically, in the neighborhoods of Indigenous people found NCRMD, 16.71% of people were Indigenous whereas just 1.98% of people in the neighborhoods of Non-Indigenous people were Indigenous.

Material deprivation was higher for Indigenous accused than non-Indigenous accused. Social deprivation was higher among non-Indigenous people; this reflects the fact that they were more likely to live alone while Indigenous people more often resided in high density homes (i.e., more people residing together). Compared to non-Indigenous people, Indigenous people came from low population density neighborhoods. Mental health resources availability (e.g., distance from a hospital, number of mental health resources in a 15 minute driving radius) was lower for Indigenous people ().

Criminal history

We examined criminal history in terms of (a) Any prior convictions or NCRMD findings combined, (b) Any prior convictions, and (c) Any prior NCRMD findings. We further reported each for any offenses, general offenses, and offenses against the person; for each category we also report offenses again persons vs. “other” offenses. About half of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people had a prior criminal conviction and/or NCRMD finding; prior NCRMD findings were rare for both groups. Indigenous people were younger at their first conviction/NCRMD finding compared to Non-Indigenous people but there was no difference in median number of prior convictions/NCRMD findings ().

Characteristics of the index offenses of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people found NCRMD

Most severe index offense

Overall, about two-thirds of both Indigenous (62.0%) and non-Indigenous (65.1%) people had been found NCRMD for offenses against persons. We also found no difference in the severity of the most severe index offense according to the Crime Severity Index. Furthermore, few differences were evident in the type of most severe index offenses of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people found NCRMD (). That being said, there may be evidence of a trend for Indigenous, compared to the non-Indigenous individuals, to have been found NCRMD for more serious offenses (homicide = 8.5% and 6.8%, respectively; assaults (including sexual assaults) = 35.2% and 28.6%, respectively). Other crimes against persons were more common among non-Indigenous (29.7%) than among Indigenous (18.3%) individuals. Property offenses accounted for about 1/5 of the most serious index offenses for both Indigenous (19.7%) and non-Indigenous individuals (16.8%); the proportion with “other” offenses was nearly identical (18.3%, 18.2%, respectively).

Table 2. Comparing the index offense, mental state at the time of the offense, and diagnosis at verdict of people found NCRMD who were and were not identified as Indigenous.

Victim of the most severe index offense

For crimes against persons, we examined the relationship between the accused and the victim of the most severe index offense (). There was little evidence of any differences between the people who Indigenous and non-Indigenous people had offended against. Both groups tended to know their victims (Indigenous = 75.0%; non-Indigenous = 77.4%). Strangers comprised approximately one-quarter of victims for both Indigenous (25.0%) and non-Indigenous (22.6%) accused. Family members were the most likely victims of both Indigenous (40.0%) and non-Indigenous (33.4%) people.

Mental state at time of the index offense

We found few differences in the mental state of the accused at the time of the index offense as a function of their ethnicity (). There was one exception, Indigenous people (34.3%) were more likely to report having experienced hallucinations at the time of the index offence χ2(1) = 9.57; phi = 0.07; p = 0.002 than were non-Indigenous people (19.2%).

Diagnosis at verdict

Indigenous accused (11.6%) were less likely to be diagnosed with mood disorders than non-Indigenous accused (23.6%), and more likely to be diagnosed with comorbid substance use disorders, personality disorders, and “other” diagnoses ().

Processing of Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals found NCRMD

Total duration of time under supervision of the Review Board

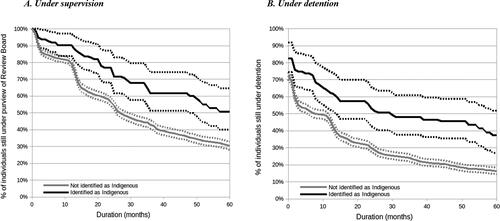

Indigenous individuals (Mdn = 5.3 years) were 1.82 times less likely to be released from the supervision of the RB than non-Indigenous individuals (Mdn = 2.21 years; Exp(b) = 0.56, SE = 0.17, Z = −3.69, p < 0.001; ). This includes time in custody and/or on conditional discharges (i.e., any time before absolute discharge). At 6 months post-verdict, just 8% of Indigenous individuals had received an absolute discharge, compared to 26% of the non-Indigenous sample. By the end of year 5, less than 30% of non-Indigenous NCRMD people remained under the supervision of the RB compared to nearly 50% of Indigenous people.

Duration of time in hospital

Indigenous individuals were 1.81 times less likely to be released from custodial dispositions than non-Indigenous individuals (Exp(b) = 0.55, SE = 0.15, Z = −4.05, p < 0.001). Indigenous individual (Mdn = 2.45 years) spent more time in hospital than non-Indigenous individual (Mdn = 0.62 years). It is noteworthy that this difference appeared to remain quite stable across the entire 5-year follow-up period ().

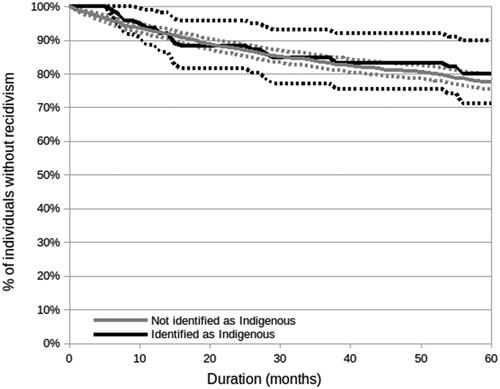

Recidivism among Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals found NCRMD

There was no difference in time to recidivism between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people (Exp(b) = 0.94, SE = 0.26, Z = −0.24, p = 0.811) (). A couple of additional observations are noteworthy. First, the rate of recidivism was low for the entire sample. Second, the rate of reoffending was nearly identical for the entire 5-year follow-up period. Finally, it is important to be mindful this does not include rehospitalization data and the sample is too small to look at types of offenses (e.g., crimes against persons vs. general).

Discussion

Under-representation of Indigenous individuals among people found NCRMD

Indigenous people are considerably over-represented across the Canadian criminal justice system (Department of Justice Canada, Citation2019a, Citation2019c; Office of the Correctional Investigator, Citation2022; Zinger, Citation2020); in stark contrast, our results suggest that they are comparatively unlikely to be found NCRMD. Québec was unique in that the proportion of Indigenous people in the general population was nearly identical (1.9%) to the proportion in prisons (2% in both provincial and federal) and the NCRMD population (1.9%). However, in BC and ON just 9.5% and 5.8% of people found NCRMD were Indigenous, compared to Indigenous people comprising 21% and 20% in BC and 9% and 10% in ON provincial and federal prisons, respectively (Malakieh, Citation2020). The low rate of Indigenous accused people found NCRMD may reveal the tip of an iceberg of structural and systemic discrimination (also see Huncar, Citation2017; Rudin, Citation2008).

Indigenous individuals comprise nearly half of all people in the Canadian criminal justice system (Office of the Correctional Investigator, Citation2022). In addition, the rates of mental disorders that give rise to an NCRMD defense are comparable among Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, if not in excess of what we see in the non-Indigenous population (Carrière et al., Citation2018; Kirmayer et al., Citation2000). This is to be expected, particularly given the disproportionate burden of social determinants of health and intergenerational trauma (Allen, Citation2020; Nelson & Wilson, Citation2017). Thus, one would expect to see the proportion of Indigenous people found NCRMD, to a large extent, mirror the proportion of Indigenous people incarcerated. There are several explanations for the low rate of Indigenous people being found NCRMD in ON and BC. It is possible that the bar is higher for Indigenous people to be found NCRMD given that Indigenous people tend to have considerably longer stays in forensic hospitals as they have higher rates of SMI compared to non-Indigenous people found NCRMD. Meaning that legal counsel for an Indigenous accused may be reluctant to raise the NCRMD defense because the accused may spend substantially longer in custody than if they were in fact convicted of the same offense (Hillaby, personal communication, 2017; Martin et al., Citation2022). It may also, or alternatively, be that this reflects under-reporting of Indigenous identity. To clarify, Indigenous individuals were likely under-counted due to poor screening and documentation of ethnicity in the RB and forensic records at the time of the study. Further, a reluctance on the part of Indigenous individuals to self-identify as Indigenous given the power imbalances between care providers and Indigenous clients, and abuses experienced by people in the criminal justice and healthcare systems in Canada, may also have resulted in Indigenous people being mis-identified (Allan & Smylie, Citation2015; Burke et al., Citation2020). There may also be discrimination within the assessment process (e.g., clinicians presented with the same symptoms come to different conclusions as a function of the person being Indigenous or not) and/or in the criminal justice process (e.g., the threshold for the judge to conclude in favor of an NCRMD defense is different for Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals). Prior research in related fields suggests mixed evidence for these hypotheses (Jeffries & Bond,Citation 2012). There may also be differences in presentation in Indigenous people compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts and these may not be captured in current assessment tools (e.g., Day et al., Citation2018; Gower et al., Citation2022). It is noteworthy that McCleery (Citation2021) examined Indigenous people in BC for the years 2015–2016 and found higher rates (15.7%) of NCRMD than in the present study (9.5%) in BC in 2000–2005. Given the timeframe of NCRMD findings in McCleery’s study is more recent, perhaps Indigenous identity is more reliably recorded and/or there is an increasing trend of Indigenous accused raising the defense more often and/or that it is more often successful. Further research is required to address these issues.

Characteristics of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people found NCRMD

We found that Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals shared many characteristics, including being predominantly male, single, often having a mental health service history and having French or English as their primary language. However, several noteworthy differences were also evident, particularly with respect to socio-economic variables and criminal history. Specifically, Indigenous persons were younger than non-Indigenous persons at the time of the NCRMD finding. Further, while the rate of education was low for non-Indigenous persons (only 50% had completed a high school diploma) it was significantly lower for Indigenous persons found NCRMD (31% had a high school diploma). Our findings, taken into consideration against the backdrop of colonialism, intergenerational trauma, discrimination and stigma facing Indigenous individuals in Canada, are a reminder of the importance of individualized, patient-centered and trauma informed care and treatment planning in forensic settings. More specifically, the state of Canada’s justice system and these findings call for culturally-safe care for Indigenous clients. For instance, Indigenous experts (Allan & Smylie, Citation2015) have described the Indigenous Cultural Competency Training Program of the Provincial Health Services Authority of British Columbia (http://www.culturalcompetency.ca) and the Cultural Safety training modules developed by the University of Victoria School of Nursing in British Columbia (http://web2.uvcs.uvic.ca/courses/csafety/mod1/resource.htm) as exemplary.

Indigenous individuals were also more like to reside in low population density neighborhoods but high population density homes. The interpretation according to the measure we used was that this reflected less social deprivation among Indigenous individuals than among non-Indigenous individuals. However, Canadian data consistently demonstrates that rural communities suffer from a lack of (mental) health resources and many predominantly Indigenous communities have higher rates of crime, and of particular concern, violent crime than other communities (Allen, 202; Jeffrey et al., Citation2019). The implications are at minimum twofold. First, it arguably calls into question the utility of our measure of social deprivation for research of this nature. Second, these intersecting social contexts have substantial implications for care planning with Indigenous clients. For instance, our findings also demonstrated that family members are the most common victims of the most serious index offenses leading to an NCRMD finding. As such, clinicians and health leaders have the challenge of simultaneously supporting cultural connectivity and family support (central to mental health recovery and violence risk prevention) while managing the challenges of rural neighborhoods and high rates of family violence in many Indigenous (and non-Indigenous) families. This is likely to require system-wide coordination well beyond forensic services. To be effective, a jurisdiction’s wider criminal justice, mental health, Indigenous, and substance use experts need to coordinate. Interventions that support social cohesion, Indigenous alternatives to justice and comprehensive healing processes have proven successful and cost-effective (e.g., for addressing sexual abuse; family violence; see Justice Canada, n.d., justice.gc.ca).

Characteristics of the index offense

The most compelling differences with respect to the characteristics of the index offense is really a reflection of the system, not the accused. Indigenous accused were more likely than non-Indigenous accused to be diagnosed with comorbid substance use or personality disorders, and “other” disorders, and less likely to be diagnosed with mood disorders. Further research is required to determine if these findings reflect true differences or if differential diagnosis reflects cultural bias. Research demonstrates that the reports of experts to the court carry considerable influence on the likelihood that the accused will or will not be found NCRMD (Whittemore, Citation1999). It is possible that biased assessments may be reflected in differential diagnoses. They may also reduce the likelihood of successful NCRMD defenses among seriously mentally ill Indigenous people who come into contact with the criminal justice system which would indicate a serious gap in the Canadian criminal justice system’s responsibility to be fair (Department of Justice Canada, Citation2019b; Lawrence & Verdun-Jones, Citation2015). Forensic evaluators should endeavor to develop specific cultural competency to ensure their assessments are unbiased (American Psychological Association, Citation2017; American Psychological Association, Citation2013).

Processing and recidivism

We found that Indigenous individuals received more restrictive dispositions than non-Indigenous individuals in terms of total duration under supervision, time in hospital, and time under community supervision. These are bivariate analyses only and should not necessarily be interpreted as discrimination; this might be affected by other factors, including the type and or severity of the index offense or the mental state of the participant at the time of the assessment for the RB. This is nonetheless striking given that we have already demonstrated that on average people found NCRMD spend longer in custody and under supervision than if they been convicted of the same offence (Martin et al., Citation2022). McCleery (Citation2021) also concluded that Indigenous people found NCRMD were detained at much higher levels than non-Indigenous people found NCRMD. We also found that the rate of reoffending was nearly identical for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people across the entire 5-year follow-up period. It is important to acknowledge that the rate of recidivism was low for the entire NTP sample (Charette et al., Citation2015; Martin et al., Citation2022; for a comparison see Office of the Correctional Investigator, Citation2020). Additional research with longer follow-up periods taking into consideration risk assessments is required to determine if Indigenous people who are truly higher risk are being detained in hospital and under conditional discharge longer. In particular, further studies examining the extent to which risk assessments (e.g., clinician biases using vignettes) and/or measures are reliable and accurate with Indigenous individuals found NCRMD is needed.

Strengths, limitations, and directions for future research

This study has the advantage of spanning the three most populous provinces in Canada, where the NCRMD defense is used most frequently, thereby increasing generalizability. This was a retrospective file-based study; thus, the proportion of people who were identified as Indigenous is likely an under-representation. Most sites did not have a systematic intake assessment that asked patients to self-report ethnicity, an important recommended change in practice. Nonetheless, self-reporting is also problematic given that Indigenous people may have been wary to self-identify as Indigenous for fear of stigma and discrimination within the health and criminal justice systems. We also could not speak to an individual’s risk to reoffend and take that into account in analyses of duration of detention in custody and length of time to absolute discharge. Although using geolocation to determine if a participant was Indigenous works well, using geo-location to determine neighborhood characteristics likely is not as reliable. Indigenous individuals have high rates of mobility, and can have low rates of census or other government data collection involvement which could affect our findings on neighborhood characteristics (see Smylie & Firestone, Citation2015).

Owing to the small number of Indigenous individuals we were also unable to further examine details on index offenses (e.g., sexual, nature of the relationship with the victim). In particular, the small sample of Indigenous persons precluded statistical analysis of processing and recidivism that took into account group differences on relevant factors, such as diagnosis (recognizing that these differences can themselves be explained as potential examples of structural bias, e.g., living on reserves where there are less resources). Further, research suggests that Indigenous people may be reluctant to self-identify in the justice system because they may be treated differently (e.g., longer sentences, reduced chance of parole (Rudin, Citation2008).

Obtaining larger samples will be integral to future research, for instance, to examine other ethnic groups (i.e., beyond “non-Indigenous”). Researchers also need to consider the effect of people living on reserves versus off of reserves both prior to the index offense and post-release/supervision will be an important consideration in future studies. For example, researchers should consider access to resources and social support available to the person in rural vs. urban and reserve vs. non-reserve contexts. An examination of our results suggests that there may be no single variable accounting for discrepancies between Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals but rather there may be many small (effect sizes) adding up to bias. Further, our capacity to measure reoffending is limited to official records, future research should include self-report data. This limitation may be particularly relevant given that marginalized individuals are more likely to come to the attention of police. It is also important to be mindful this does not include rehospitalizations. There is also a need for research examining whether forensic systems with culturally safe care and that provide Indigenous-specific interventions might yield better outcomes for Indigenous persons.

Conclusion

The Correctional Investigator recently concluded that “The Indigenization of Canada’s prison population is nothing short of a national travesty” (Public Safety Canada, Citation2020, para. 5). The gravity of the situation has been described similarly by the Canadian Department of Justice: “The figures are stark and reflect what may fairly be termed a crisis in the Canadian criminal justice system” (R v Gladue, Citation1999, para. 64). These results add to this body of research suggesting that the challenges confronting our wider criminal justice system may also be deeply embedded in Canadian forensic systems. Further research, that includes Indigenous community partnerships, should assess reasons why Indigenous Canadians are proportionately under-represented among people being found NCRMD in Canada given the rates of criminal justice involvement and evaluate the extent to which culturally-safe assessments and care are being provided.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by consecutive grants #6356-2004 from Fonds de recherche Québec—Santé (FRQ-S) and by the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC). Dr Crocker received consecutive salary awards from, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and FRQ-S, as well as a William Dawson Scholar award from McGill University while conducting this research. Dr Nicholls is grateful for the support of the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and the CIHR for consecutive salary awards and her CIHR Foundation Grant. Dr. Yanick Charette acknowledges the support of the FRQ-S for his research scholar grant. This research was undertaken in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs Program to Dr Crocker.

This study would not have been possible without the full collaboration of the Québec, British Columbia, and Ontario Review Boards, and their respective registrars and chairs. We are especially grateful to Me [attorney] Mathieu Proulx, Bernd Walter, and Justice Douglas H Carruthers and Justice Richard Schneider, the Québec, British Columbia, and consecutive Ontario RB chairs, respectively.

The authors sincerely thank Erika Jansman-Hart and Dr Cathy Wilson, Ontario and British Columbia coordinators, respectively, as well as our dedicated research assistants who spent an innumerable number of hours coding RB files and Royal Canadian Mounted Police criminal records: Erika Braithwaite, Dominique Laferrière, Catherine Patenaude, Jean-François Morin, Florence Bonneau, Marlène David, Amanda Stevens, Christian Richter, Duncan Greig, Nancy Monteiro and Fiona Dyshniku. Finally, we are grateful to the reviewers who offered exceptionally detailed and constructive critiques to assist us in strengthening this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Consistent with government reports, this paper uses the term “Indigenous” and it is intended to be a more contemporary terminology for the term “Aboriginal.” As per the Constitution Act of 1982, “Aboriginal” people includes First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people of Canada (e.g., Clark, Citation2019).

References

- Allan, B., & Smylie, J. (2015). First Peoples, second class treatment: The role of racism in the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples in Canada. The Wellesley Institute.

- Allen, M. (2020). Crime reported by police serving areas where the majority of the population is Indigenous, 2018. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2020001/article/00013-eng.htm.

- American Psychological Association. (2013). Speciality guidelines for forensic psychology. American Psychologist. Retrieved 2023, February 5, from forensic-psychology.pdf (apa.org)

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Multicultural guidelines: An ecological approach to context, identity, and intersectionality. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/about/policy/multicultural-guidelines.pdf

- Burke, M., Moschella, M., & Radnofsky, C. (2020). Dying Indigenous woman films video of nurses taunting her at Canadian hospital. Retrieved 2023, February 5, from nbcnews.com.

- Carrière, G., Bougie, E., & Kohen, D. (2018). Acute care hospitalizations for mental and behavioural disorders among First Nations people [Data set]. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2018006/article/54971-eng.htm.

- Charette, Y., Crocker, A. G., Seto, M. C., Salem, L., Nicholls, T. L., & Caulet, M. (2015). The national trajectory project of individuals found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder in Canada. Part 4: Criminal recidivism. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 60(3), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371506000307

- Clark, S. (2019). Overrepresentation of Indigenous People in the Canadian Criminal Justice System: Causes and Responses. Research and Statistics Division, Department of Justice Canada.

- Cox, D. R. (1972). Regression models and life-tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 34(2), 187–202. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0035-9246%281972%2934%3A2%3C187%3ARMAL%3E2.0.CO%3B2-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1972.tb00899.x

- Criminal Code, R.S.C. (1985). c. C-46. https://www.laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-46/page-8.html#h-115891.

- Crocker, A. G., Charette, Y., Seto, M. C., Nicholls, T. L., Côté, G., & Caulet, M. (2015a). The national trajectory project of individuals found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder in Canada. Part 3: Trajectories and outcomes through the forensic system. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 60(3), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371506000306

- Crocker, A. G., Nicholls, T. L., Charette, Y., & Seto, M. C. (2014). Dynamic and static factors associated with custody dispositions: The National Trajectory Project of individuals found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder in Canada. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 32(5), 577–595. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2133

- Crocker, A. G., Nicholls, T. L., Seto, M. C., Charette, Y., Côté, G., & Caulet, M. (2015b). The National Trajectory Project of individuals found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder in Canada. Part 2: The people behind the label. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 60(3), 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371506000305

- Day, A., Tamatea, A. J., Casey, S., & Geia, L. (2018). Assessing violence risk with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander offenders: Considerations for forensic practice. Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law, 25(3), 452–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2018.1467804

- Department of Justice Canada. (2019a). Indigenous overrepresentation in the criminal justice system. Government of Canada. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/jr/jf-pf/2019/docs/may01.pdf.

- Department of Justice Canada. (2019b). On the review of Canada’s criminal justice system. Government of Canada. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/tcjs-tsjp/fr-rf/docs/fr.pdf.

- Department of Justice Canada. (2019c). Spotlight on Gladue: Challenges, experiences, and possibilities in Canada’s criminal justice system. Government of Canada. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/jr/gladue/p2.html.

- Desmarais, S., & Hucker, S. (2005). Multi-site follow-up study of mentally disordered accused: An examination of individuals found not criminally responsible and unfit to stand trial. Research and Statistics Divisions, Department of Justice Canada. p. 40.

- Gladue, R. v. (1999). CanLII 679 (SCC), [1999] 1 SCR 688. https://canlii.ca/t/1fqp2.

- Government of Canada. (2010). Highlights from the report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal peoples. Government of Canada. https://rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100014597/1572547985018.

- Gower, M., Morgan, F., & Saunders, J. (2022). Aboriginality and violence: Gender and cultural differences on the level of service/risk, need, responsivity (LS/RNR) and violence risk scale (VRS). Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 29, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2021.2006098

- Hanson, E., Gamez, D., & Manuel, A. (2020, September). The Residential School System. Indigenous Foundations. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/residential-school-system-2020/

- Hojat, M., & Xu, G. (2004). A visitor’s guide to effect sizes: Statistical significance versus practical (clinical) importance of research findings. Advances in Health Sciences Education : Theory and Practice, 9(3), 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:AHSE.0000038173.00909.f6

- House of Commons Canada. (2018). A call to action: Reconciliation with Indigenous women in the federal justice and correctional systems. Report of the Standing Committee on the Status of Women. https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/FEWO/Reports/RP9991306/feworp13/feworp13-e.pdf

- Huncar, A. (2017). Indigenous women nearly 10 times more likely to be street checked by Edmonton police, new data shows. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/street-checks-edmonton-police-aboriginal-black-carding-1.4178843

- Jeffries, S., & Bond, C. E. W. (2012). The impact of indigenous status on adult sentencing: A review of the statistical research literature from the United States, Canada, and Australia. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice, 10(3), 223–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377938.2012.700830.

- Jeffrey, N., Johnson, A., Richardson, C., Dawson, M., Campbell, M., Bader, D., Fairbairn, J., Straatman, A. L., Poon, J., & Jaffe, P. (2019). Domestic violence and homicide in rural, remote, and northern communities: Understanding risk and keeping women safe. Domestic Homicide (7). Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative. ISBN 978-1-988412-34-4Brief_7.pdf (cdhpi.ca)

- Justice Canada. (n.d.). 10. Impact of Alternatives to the Criminal Justice System – Part I: Literature Review (continued) – A Review of Research on Criminal Victimization and First Nations, Métis and Inuit Peoples 1990 to 2001; Hollow Water First Nation – Community Holistic Circle Healing Program – Compendium Annex: Detailed Practice Descriptions (justice.gc.ca)

- Kirmayer, L. J., Brass, G. M., & Tait, C. L. (2000). The mental health of aboriginal peoples: Transformations of identity and community. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 45(7), 607–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370004500702

- Lawrence, M. S., & Verdun-Jones, S. (2015). Delusions of justice: Results of qualitative research on the management in British Columbia of cases involving allegations of substance-induced psychosis. Criminal Law Quarterly, 62(4), 475–503.

- Malakieh, J. (2020). Adult and youth correctional statistics in Canada, 2018/2019 [Data set]. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2020001/article/00016-eng.htm.

- Marshall, T., & Gallant, D. (2012). Residential schools in Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/residential-schools.

- Martin, S., Charette, Y., Leclerc, C., Seto, M. C., Nicholls, T. L., & Crocker, A. G. (2022). Not a “get out of jail free card”: Comparing the legal supervision of persons found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder and convicted offenders. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 775480. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.775480

- McCleery, K. (2021). "Resort to the Easy Answer": Gladue and the Treatment of Indigenous NCRMD Accused by the British Columbia Review Board, U.B.C. Law Review, 54(1), 151–202.

- National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG). (2019). Reclaiming power and place. The final report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. Volume 1a. https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Final_Report_Vol_1a-1.pdf

- Nelson, S. E., & Wilson, K. (2017). The mental health of Indigenous people in Canada: A critical review of research. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 176, 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.021

- Office of the Correctional Investigator. (2013). Backgrounder Aboriginal offenders – A critical situation. http://www.oci-bec.gc.ca/cnt/rpt/oth-aut/oth-aut20121022info-eng.aspx

- Office of the Correctional Investigator. (2020). Indigenous people in federal custody surpasses 30% Correctional Investigator issues statement and challenge. Government of Canada. https://www.oci-bec.gc.ca/cnt/comm/press/press20200121-eng.aspx.

- Office of the Correctional Investigator. (2022). Annual report of the Office of the Correctional Investigator 2021–2022.

- Ogilvie, J. M., Allard, T., Thompson, C., Dennison, S., Little, S. B., Lockwood, K., Kisely, S., Putland, E., & Stewart, A. (2022). Psychiatric disorders and offending in an Australian birth cohort: Overrepresentation in the health and criminal justice systems for Indigenous Australians. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 56(12), 1587–1601. 00048674211063814. https://doi.org/10.1177/00048674211063814

- Pampalon, R., & Raymond, G. (2003). Indice de défavorisation matérielle et sociale: Son application au secteur de la santé et du bien-être. Santé, Société et Solidarité, 2(1), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.3406/oss.2003.932

- Pampalon, R., Hamel, D., Gamache, P., & Raymond, G. (2009). A deprivation index for health planning in Canada. Chronic Diseases in Canada, 29(4), 178–191. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.29.4.05

- Public Safety Canada. (2020). Indigenous people in federal custody surpasses 30% correctional investigator issues statement and challenge. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-safety-canada/news/2020/01/indigenous-people-in-federal-custody-surpasses-30-correctional-investigator-issues-statement-and-challenge.html.

- R Development Core Team. (2010). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org.

- Rudin, J. (2008). Aboriginal Over-representation and R. v. Gladue: Where We Were, Where We Are and Where We Might Be Going. The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference 40. (2008). https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr/vol40/iss1/22

- Salem, L., Crocker, A. G., Charette, Y., Seto, M. C., Nicholls, T. L., & Côté, G. (2015). Supportive housing and forensic patient outcomes. Law and Human Behavior, 39(3), 311–320. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000112

- Sim, R. v. (2005). (D.R.), 203 O.A.C. 128 (CA)

- Sixties Scoop. (n.d.). Retrieved 2023, February 4, from https://indigenousfoundations.web.arts.ubc.ca/credits.

- Smylie, J., & Firestone, M. (2015). Back to the basics: Identifying and addressing underlying challenges in achieving high quality and relevant health statistics for Indigenous populations in Canada. Statistical Journal of the IAOS, 31(1), 67–87. https://doi.org/10.3233/SJI-150864

- Stamatis, D. H. (2003). Six stigma and beyond: Statistics and probability. CRC Press.

- Statistics Canada. (2006). 2006 Census of Population, Catalogue (no. 94-575-XCB2006001) [Data set]. Statistics Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/dp-pd/prof/rel/Rp-eng.cfm?LANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=1&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=1&GC=0&GID=0&GK=0&GRP=1&PID=89108&PRID=0&PTYPE=89103&S=0&SHOWALL=No&SUB=0&Temporal=2006&THEME=66&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Retrieved from http://trc.ca/assets/pdf/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

- Wallace, M., Turner, J., Matarazzo, A., & Babyak, C. (2009). Measuring crime in Canada: Introducing the crime severity index and improvements to the uniform crime reporting survey (Publication n 85-004-X). Canadian Centre from Justice Statistics, Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/85-004-x/85-004-x2009001-eng.pdf?st=sd4yUW0h.

- Whittemore, K. E. (1999). [Releasing the mentally disordered offender: Disposition decisions for individuals found unfit to stand trial and not criminally responsible]. (Publication No. NQ51935) [Doctoral dissertation]. Simon Fraser University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Wilson, C. M., Nicholls, T. L., Charette, Y., Seto, M. C., & Crocker, A. G. (2016). Factors associated with review board dispositions following re‐hospitalization among discharged persons found not criminally responsible. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 34(2–3), 278–294. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2162

- Winko v. British Columbia (Forensic Psychiatric Institute). (1999). 2 S.C.R. 625, 1999 CanLII 694 (S.C.C.).

- Zinger, I. (2020). Indigenous people in federal custody surpasses 30%. Correctional investigator issues statement and challenge. https://www.oci-bec.gc.ca/cnt/comm/press/press20200121-eng.aspx