Abstract

Past research suggests that diverting young people away from the criminal justice system and into mental health services can reduce subsequent reoffending, but the impact of such programs on the rates of timely mental health service contact are largely unknown. In this study, we examined a sample of 523 young people who were deemed eligible for mental health diversion between 2008 and 2015. Around half (47%) of these young people were granted diversion by a Magistrate. Overall, the levels of timely mental health service contact after court finalization, even for those who were granted diversion, appeared low given that the purpose of diversion is to facilitate such contact for all those diverted. Specifically, only 22% of those who were granted community-based diversion and 62% of individuals granted inpatient-based diversion had mental health service contact within 7 days of court finalization. Rates of health contact were much lower for those who were not granted either type of diversion (8% and 23%, respectively). Diversion was associated with a significant reduction in reoffending rates, but the impact of early mental health service contact was less clear. There is a need to understand the reasons why many young people are not accessing appropriate mental health services following diversion in order to improve outcomes and fully realize the intended benefits of mental health court diversion.

Introduction

Mental health courts and mental health court diversion and liaison services have been developed in some form in most developed jurisdictions internationally with the aim of addressing the high rates of mental illness among those in contact with the criminal justice system (e.g., Davidson et al., Citation2016; Davidson et al., Citation2017). While less well established than those aimed at adults, court diversion services for young people with mental health problems have also been developed in many settings. In both populations, there has been a focus on examining rates of reoffending and repeat justice contact following diversion (e.g., Fox et al., Citation2021), with some adult studies demonstrating increased community mental health treatment engagement (Boothroyd et al., Citation2003; Broner et al., Citation2004; Herinckx et al., Citation2005). Among young people eligible for mental health court diversion in New South Wales (NSW), the largest state in Australia, those who were granted diversion were found to be less likely to reoffend than those not diverted (Gaskin et al., Citation2022). Many other international studies have similarly focused on the impact mental health diversion at court has on recidivism for young people (e.g., Cuellar et al., Citation2006; Heretick & Russell, Citation2013), but the impact on rates of mental health service contact or health outcomes are less well understood. Studies from the United States have suggested that mental health court diversion for young people may be associated with an increase in referrals and access to mental health treatment services (e.g., Barrett et al., Citation2022; Colwell et al., Citation2012). However, to our knowledge, no studies to date have further investigated the relationship between court diversion and the patterns of subsequent contact with mental health services for young people. While the legislation and processes to facilitate diversion at court are commonly in place in many jurisdictions, the intervention relies to a large extent on diverted individuals actually having contact with mental health services, as an essential step toward delivering effective mental health outcomes.

Given that mental health court diversion services around the world differ substantially in term of policy frameworks, legal provisions, and practice, examining the impact of diversion on mental health service contact in local contexts is crucial for local service development. In NSW, young people who have been charged with an offense at local (Children’s) court level may be granted a mental health diversion. Eligible young people are identified through assessments conducted by the NSW Adolescent Court and Community Team (ACCT), part of Justice Health NSW, a publicly funded health service. This service functions across NSW’s busiest Children’s Courts and takes referrals for eligibility assessment from numerous sources, including the Children’s Legal Service, Juvenile Justice (now called Youth Justice), Legal Aid, the Aboriginal Legal Service, a Magistrate, Family and Community Services, the police, family member or carers, or the young person themselves. Upon referral and after consent is obtained from the young person’s legal representative, the young person is assessed by a mental health clinician from the ACCT to determine eligibility for diversion. The outcome of the ACCT assessment is presented in court by a typed report and considered by the Magistrate who decides whether or not to grant diversion. Diversion can be community-based (section 32; s 32) or inpatient-based (section 33; s 33) under the Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act 1990 (now supported under sections 14 and 19 respectively of the Mental Health and Cognitive Impairment Forensic Provisions Act 2020). The ACCT clinician identifies the type of formal diversion they believe is appropriate for the young person (i.e., s 32 or s 33) and the Magistrate makes the final decision on which diversion to grant, if any. For the ACCT service, mental health court diversion aims to 1) provide a path toward treatment rather than punishment, and 2) reduce reoffending and other negative outcomes for individuals and the broader community (AIC, Citation2011).

In this study, data from a cohort of young people who were deemed eligible for diversion by the NSW ACCT between 2008 and 2015 were analyzed to describe the patterns of post-diversion mental health service contact. Factors associated with receiving mental health service contact, and associations between health service contact and reoffending, were examined.

Method

Sample, data sources, and initial record linkage procedure

The total sample used in this study is the same as that described in Gaskin et al. (Citation2022). Specifically, it consisted of 1,492 young people who had been referred to and assessed by mental health clinicians working within the ACCT in New South Wales on at least one occasion between January 11, 2008, and December 18, 2015. To investigate our research questions, we linked five unique health and justice administrative databases.

The initial data linkage for this project included the ACCT database and the Reoffending Database (ROD, NSW Bureau of Crime and Statistics and Research). In brief, a third-party linkage agency (the Centre for Health Record Linkage, CHeReL) linked the two databases by matching individuals using probabilistic linkage methods relying on available identifying variables such as name, sex, and date of birth. In total, 98.5% (n = 1,469) of individuals in the ACCT database were matched to the ROD data. A linked de-identified database, including unique project specific person numbers (PPNs), was then used by the research team for subsequent analyses.

Diversion

The ACCT database consists of demographic, clinical and assessment-related, referral, and legal information that is collected by ACCT mental health clinicians. This includes information such as age, sex, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background, primary health concern (e.g., mental health, drug/alcohol, or comorbidity of both), residential area and socio-economic status of residence rating (classified by the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas [SEIFA] quartiles, ABS, Citation2011), referral agency, and principal index offense. As in Gaskin et al. (Citation2022), principal index offense was considered violent when it fell in one of the following categories: homicide and related offenses (with the exception of driving causing death); acts intended to cause injury; sexual assault and related offenses (with the exception of child pornography and non-assaultive sexual offenses); aggravated robbery; abduction and kidnapping, deprivation of liberty and false imprisonment; or riot and affray.

At the time of ACCT data collection, there were two types of formal mental health diversion in NSW, as defined by the Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act 1990 (NSW).Footnote1 Community-based diversion under s 32 resulted in the defendant being discharged to the care of a responsible person (e.g., psychiatrist, other doctor, case manager, etc.), with or without conditions (e.g., compliance with a mental health treatment plan). Inpatient-based diversion under s 33 required the person to be transferred to a declared mental health facility for further assessment to be undertaken with a view to determining suitability for inpatient treatment.

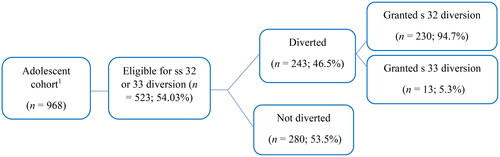

Of the 1,469 individuals from the original ACCT database sample who were successfully matched to the ROD, 968 individuals were identified as having had court contact for an offense that occurred prior to the individual’s most recent ACCT contact and an ACCT contact that occurred on or after the earliest court date for that court contact event. Of this group, 523 (54.0%) were determined to be eligible for formal diversion by ACCT clinicians and formed the cohort for analysis. The linked ACCT and ROD data for the sample was then examined to identify which of the 523 individuals deemed eligible for formal mental health diversion were actually granted diversion by the Magistrate under ss 32 or 33 of the Act. As in Gaskin et al. (Citation2022), outcomes in the ROD dataset were preferred if there were discrepancies between the ACCT and ROD datasets. Just under half (n = 243, 46.5%) of these 523 eligible young people were granted a diversion by the Magistrate.

Reoffending outcomes

The ROD dataset included information on all finalized criminal court contacts between January 4, 1994, and August 31, 2019. Reoffending was thus determined by identifying any finalized charges recorded in the ROD for offenses that occurred on or after the finalization date for the index court contact event that resulted in diversion.

Mental health contact outcomes

Next, three health datasets were linked to the cohort using the same methodology as described earlier. Two datasets, the NSW Admitted Patient Data Collection (APDC), the NSW Mental Health Ambulatory Data Collection (MH-AMB) were used to determine inpatient and outpatient/community mental health service contacts. Both datasets included data beginning in 2001 and thus covering the full time period of relevance to the study (i.e., 2008–2015). Though the legislation does not mandate health contact to occur within a certain time period, we have examined the period up to one week from the court finalization date on the basis that this provides a reasonable indication of timely contact. Specifically, we examined health contacts that took place on the same day as the individual’s court finalization date, within 3 days of this date, and within 7 days of this date. In the case of multiple health contacts within the time period, the earliest contact was used within each database.

The APDC records all admitted patient services provided by NSW public hospitals, public psychiatric hospitals, public multi-purpose services, private hospitals, and private day procedures centers. This dataset includes information about a patient’s time in hospital (called an episode of care), including demographic information, diagnoses, procedures, and administrative information. Reporting to the APDC is a requirement for all public and private hospitals.

The MH-AMB consists of data relating to the assessment, treatment, rehabilitation, or care of non-admitted patients with mental illness and includes publicly funded services such as community mental health team contact, mental health day programs, psychiatric outpatient clinics, and outreach services. In this study, we examined only clinical contacts (i.e., excluding purely administrative events), which included activities such as assessment, counseling and education, care conferences, day program activities, psychoeducation, medication-related activities, psychotherapy, clinical review, and skills training. Privately funded (including Commonwealth-funded) services are not included.

The third database was the Emergency Department Data Collection (EDDC), which was used to identify emergency mental health contacts occurring within 7 days of court finalization. The EDDC provides information regarding presentations to the Emergency Departments (EDs) of NSW public hospitals, with 184 participating hospitals in 2016/17. This information includes dates and times of presentation and discharge, reason for presentation, and the outcome of the presentation (e.g., admission, discharge, or death). Linked ED data are available from January 2005 onwards, thus covering the relevant time period for the current study. Diagnoses in the EDDC are recorded by medical, nursing, or clerical personnel at the point of care; diagnostic codes for mental health (i.e., F01-99) and self-harm (i.e., X60-84) were included for the current study.

Of the 523 individuals determined to be eligible for diversion by the ACCT clinicians, 439 (83.9%) were identified in the APDC records and 361 (69.0%) were identified in the EDDC records. Data from all 523 individuals were linked to the MH-AMB dataset. Inpatient health contacts where Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network was the service provider were excluded, except where otherwise specified, on the basis that these contacts occurred in a prison setting and could not be reasonably regarded as healthcare provided following diversion away from the justice system. Health contacts outside of these datasets are unknown and could include services such as private outpatient psychiatric care and primary care mental health interventions.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using SPSS version 27. Descriptive analyses were conducted to summarize the basic sociodemographic, clinical, referral, and criminological variables for the sample of adolescents eligible for formal mental health diversion. Binary logistic regression analyses were then conducted to examine whether these characteristics, including having been granted diversion, were associated with the likelihood of an individual having health contact within 7 days of their court finalization date. Finally, univariable Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were used to investigate whether being granted diversion followed by health contact was associated with reoffending across the sample.

Ethical approval

Approval for this study was obtained from the NSW Justice Health & Forensic Mental Health Network (File No. G338/14), the Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council of NSW (No.1152/15), and the NSW Population & Health Services Research Ethics Committee (Reference HREC/15/CIHS/33).

Results

Sample characteristics

presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the 523 adolescents who were deemed eligible for formal mental health diversion (i.e., ss 32 or 33) by ACCT clinicians. The sample consisted of individuals who were mostly male (70.7%), younger (66.9% between 11–16 years), and resided in urban areas (92.9%). Around half (43.4%) were of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander background. One-quarter were from areas of the highest disadvantage (24.7%) and approximately 15% lived in areas of least disadvantage (classified by SEIFA quartiles, ABS, Citation2011).

Table 1. Characteristics of cohort members deemed eligible for mental health court diversion (i.e., ss 32 or 33, n = 523).

The young people were most commonly referred to the ACCT by the Children’s Legal Service (58.7%), a subset of Legal Aid NSW. Juvenile Justice (now called Youth Justice) referred an additional 17.2% of young people and the Aboriginal Legal Service referred nearly 12%. Primary mental health problems were identified for two-thirds of young people (63.3%), while one-third had comorbid mental health and substance use problems (33.3%). ‘Acts intended to cause injury’ was the most common principal index offense category (40.2%), followed by offenses against justice procedures, government security, and government operations (19.7%), unlawful entry/burglary or break and enter (9.2%), and public order offenses (8.0%). Over a third of principal index offenses were violent in nature (35.2%).

Of the 523 individuals deemed eligible for diversion, 243 (46.5%) were diverted by the Magistrate and 280 (53.5%) were not diverted (). Some participants (n = 17) were deemed eligible for both inpatient- and community-based diversions. Of the 487 individuals deemed eligible by the ACCT for community-based diversion (i.e., s 32), 230 were granted diversion (47.2%). Of the 53 people deemed eligible by the ACCT for inpatient-based diversion (i.e., s 33), 13 were granted diversion (24.5%).

Mental health contact after being deemed eligible for diversion

Main analyses

A summary of the number of adolescents deemed eligible for ss 32 or 33 and their subsequent health contacts (on the same day, within 3 days, or within 7 days) is presented in . Of those who were granted diversion, of either type, 7.0% (n = 17) received mental health service contact on the same day as their court finalization date, 15.6% (n = 38) within 3 days and just under a quarter (24.3%; n = 59) received health contact within 7 days. Of those not granted diversion, only 7.9% (n = 22) had any mental health service contact within 7 days of their court finalization date.

Table 2. Patterns of mental health service contact (inpatient or community) following court finalization amongst those deemed eligible for mental health court diversion.

Similar patterns were observed when the 230 individuals who were granted a community-based s 32 diversion were considered specifically (). When only considering those who were granted the more infrequent inpatient-based s 33 diversion, the proportions of young people having contact with mental health services was increased, with 53.8% (n = 7) having health contact on the same day as their court finalization date.

presents associations between sociodemographic and criminological characteristics and the odds of an individual receiving health contact within 7 days of their court finalization date. Reassuringly, being granted diversion of either type was significantly associated with receiving health service contact. Individuals who received either diversion (ss 32 or 32) were more than 3.7 times more likely to receive health contact within 7 days than individuals who were not granted diversion (95% CI 2.23–6.36). Only one other factor was significantly associated with the odds of health service contact; adolescents whose primary index offense was violent were nearly 1.7 times more likely to receive health contact within 7 days than those whose primary index offense was nonviolent (95% CI 1.04–2.73). Finally, it is worth noting that females were 1.6 times more likely than males to receive health contact within seven days, though this factor did not reach significance (95% CI 0.99–2.67).

Table 3. Binary logistic regression analysis (univariate) of associations between sociodemographic characteristics and odds of receiving health contact within 7 days of court finalization, n = 523.

Inpatient treatment vs. community treatment

We also examined summary statistics regarding whether the health contact occurred in an inpatient (i.e., APDC dataset) or community (i.e., MH-AMB dataset) setting. For those granted a community-based s 32 diversion (n = 230), five were admitted to hospital (2.2%) and 47 had health contact within the community (20.4%) within one week of their court finalization. Interestingly, those not granted s 32 diversions (n = 257) had a similar rate of hospital admissions (2.7%, n = 7), but a lower rate of community health contact (6.2%, n = 16) within one week of court finalization. Unsurprisingly, those granted inpatient-based s 33 diversions were more likely to experience hospital admission than community-based health contact. Of those granted s 33 diversion (n = 13), eight (61.5%) were admitted to hospital and fewer than five had community-based health contact within one week. Conversely, those who were not granted s 33 diversion (n = 40) had a higher rate of health contact in the community (20.0%) than hospital admissions (7.5%).

Inpatient treatment Details of diverted young people

s 32 Diversions. Those granted s 32 community-based diversions were sometimes, though rarely, admitted to hospital. Of those who were granted s 32 diversion and admitted to hospital within 7 days (n = 5), the average length of stay was 2.4 days (SD = 2.9, median = 1.0, range = 1 day to 6 days). Diagnostic codes related to mental illness included borderline personality disorder, psychotic disorders, and self-injurious poisoning. Diagnostic codes not directly related to mental illness included gastritis and neck injury. s 33 Diversions. Those who were granted s 33 diversion and admitted to hospital within 7 days (n = 8) had an average length of stay of 12.3 days (SD = 10.3, median = 11.0, range = 1 day to 31 days. All eight young people had primary diagnostic codes directly related to a psychotic disorder, including unspecified or ‘other’ schizophrenia, acute and transient psychotic disorder, unspecified psychosis, or other psychotic disorder not due to a substance or known physiological condition. Seven of the eight young people stayed in the psychiatric unit, and five were detained on an involuntary basis.

Community treatment Details of diverted young people.Footnote2

s 32 Diversions. Of those granted s 32 diversion who had mental health treatment in the community within one week of their court finalization (n = 47), the average duration of clinical contact was 62.6 min (SD = 62.4, median = 45.0, range = 5 min to 240 min). Most were seen face-to-face (n = 31; 66.0%) and the most common service provider types were non-clinical psychologist (n = 13; 27.7%), clinical psychologist (n = 7; 14.9%), and social worker (n = 7; 14.9%). The remainder were seen by other provider types including a registered nurse, clinical nurse specialist, psychiatric registrar, occupational therapist, clinical nurse consultant, health education officer, consultant psychiatrist, or general health provider.Footnote3 Over a third of the participants were not allocated a diagnosis (n = 17), but those who were had diagnoses including schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety disorder, conduct disorder, eating disorder, adjustment disorder, intentional self-harm, and suicidal ideation.

Emergency department mental health contactFootnote4

s 32 Diversions. We also examined emergency department mental health contact among those deemed eligible for diversion (see Table A in supplementary materials). Of those granted s 32 diversions, six individuals presented to ED within a week of their court finalization date. Diagnoses included unspecified anxiety disorder, conduct disorder, mental and behavioral disorder due to multiple drug use and use of other psychoactive substances (acute intoxication), and unspecified psychosis not due to a substance or known physiological condition.

Mental health contact within the criminal justice system

In post hoc analyses, the number of mental health service contacts recorded as being delivered by the health service responsible for care in youth custody (i.e., Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network) were determined. Of the 243 individuals who were granted diversion, 23 (9.5%) received such contact on the same day or within 3 days of their court finalization, with an additional person receiving custody-based mental health service contact within 7 days (total 9.8%). Of the 280 individuals who were not granted either type of diversion, 22 (7.9%) received custody-based contact on the same day, 24 (8.6%) within 3 days, and 29 (10.4%) within 7 days of their court finalization. These delays may be due to mental health services being part-time in most youth justice centers. Though such mental health service contacts cannot be regarded as diversion away from the justice system, they still indicate receipt of mental health service contact, albeit in custody.

Associations between mental health contact and reoffending

presents associations between diversion status, mental health service contact, and reoffending outcomes. Over three-quarters (81.6%) of the 523 young people who were deemed eligible for diversion were charged with another offense by the end of the follow-up period (i.e., through August 31, 2019; range = 0 days to 2814 days [7.7 years], M = 9.5 months, SD = 13.3 months). Those who were not granted formal diversion had greater odds of reoffending (HR = 1.33, 95% CI 1.10–1.61). Reoffending incidence rates for adolescents who had health contacts (same day, within 3 days, or within 7 days) were all apparently lower than for adolescents who did not receive any health contact. In particular, very early health care contact (i.e., within 3 days) may be associated with reduced reoffending (HR = 1.32, 95% CI = 0.95–1.84). However, these associations were not statistically significant.

Table 4. Univariable Cox proportional hazards regression showing associations between health contact and any reoffending for those eligible for ss 32 or 33.

Discussion

In a sample of 523 young people who mental health court clinicians deemed eligible for mental health diversion in NSW between 2008 and 2015, around half (47%) were granted diversion by a Magistrate. Overall, the levels of timely mental health service contact after court finalization, even for those who were granted diversion, appeared low given that the purpose of diversion is to facilitate such contact for all those diverted. Specifically, only 22% of those who were granted community-based diversion and 62% of individuals granted inpatient-based diversion had mental health service contact within 7 days of court finalization. As expected, rates of health contact were much lower for those who were not granted either type of diversion (8% and 23%, respectively). Diversion was associated with a significant reduction in reoffending rates, but the impact of early mental health service contact was less clear.

Patterns of post-diversion health service contact

While mental health service contact rates were higher for those young people granted diversion at court, less than a quarter of those granted community-based diversion and two-thirds of those granted inpatient-based diversion received health contact within one week. Given one purpose of mental health court diversion is to facilitate timely mental health service contact, these rates are lower than might be expected and raise questions about persistent barriers to mental healthcare access that might be experienced by young people in contact with the criminal justice system.

Comparable previous research in this area is limited, partly due to jurisdictional differences regarding legal and service provisions. Some past research in a similar setting suggested that diversion increases referrals to community services for young people (e.g., Colwell et al., Citation2012), though no actual rates of health contact were reported. A study of diverted adults with psychosis in NSW showed that 91% received health service contact at some point during the study, but whether the contact was timely in relation to court finalization was not reported (Albalawi et al., Citation2019). We are not aware of any other comparable studies that have investigated actual health service contact rates in a group of young people in a similar court diversion scheme.

When the type of mental health service contact was examined, young people who were granted inpatient-based diversion had much higher rates of admissions to hospital and presentations to emergency departments within one week of court finalization than those who were granted community-based diversion. Rates of health contact in the community within this time period were similar for the two types of diversion. These results suggest that the type of diversion granted does impact the type of health service accessed as expected but, across the board, rates of health contact were still lower than what would be expected if diversion was functioning as intended.

Among those admitted to hospital, average stays were longer for those granted inpatient-based diversion than for those granted for community-based diversion, suggesting a more intensive level of treatment needed for the former group. Conversely, clinical contact in community treatment settings was, on average, longer for those granted community-based diversion than inpatient-based diversion. Those admitted to hospital with diagnoses of mental illness were primarily diagnosed with psychotic disorder, while those who presented to an ED tended to have a diagnosis of conduct, psychotic, or substance use disorder. Young people treated in the community had a broader range of diagnoses recorded, with diagnoses not recorded at all in many cases. These diagnostic differences across healthcare settings are largely in line with what would be expected in relation to the different types of diversion. Those young people presenting to emergency departments may represent a group poorly served by court diversion and mental health services.

Past criticisms of youth diversion have raised concerns relevant to the current study findings (Gotsis & Donnelly, Citation2008; Richardson & McSherry, Citation2010). In 2012, the NSW Law Reform Commission suggested that diversion was not always effectively used by Magistrates, who were concerned about a lack of accountability for diverted individuals. The NSW Law Reform Commission also highlighted the lack of therapeutic programs and services necessary for a successful diversion program (NSW Law Reform Commission, Citation2012). Those young people granted mental health diversion at court are clearly in need of timely access to appropriate health care treatment, hence our decision to examine health contacts within one-week of diversion, although it should be acknowledged that this timeframe is an arbitrary one. It is also important to note that there are often prolonged waiting times for many young people trying to access mental health services in the community and this experience is therefore not unique to those granted diversion. Long waiting times for both public and private mental health services have been reported across Australia (Iskra et al., Citation2018; Mulraney et al., Citation2021; The Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 2023). For example, the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) in one NSW local health district has reported that the anticipated wait time for an initial assessment is up to two weeks (HNE Kids Health, 2023). As such, a lack of well-funded and available services may help explain the inadequate levels of timely health service contact found in the current study amongst those diverted. In addition to appropriately resourcing community mental health services, further research should be undertaken to identify other barriers that could contribute to young people, diverted at court, not accessing community care in a timely way. These could include concern about stigma, inappropriate service provision, or access and transport issues for young people - all of which could be contributing to the lack of contact identified in the current study regarding mental health court diversion in NSW. It is also important to note that the current study findings do not point to any specific causes of the low rate of timely contact with mental health services following diversion and that further research is needed to identify targets for service improvement.

Recent changes have been made in NSW following a revision of the legislation that enables mental health court diversion (i.e., in the Mental Health and Cognitive Impairment Forensic Provisions Act 2020) that aim to address some of these problems. In the updated community-based diversion section (now under s 14 rather than s 32), Magistrates are provided with a list of factors they may take into account, including the seriousness of offense(s), criminal history, alternative sentencing options, whether person has history of diversion orders, and whether there is a proper treatment or support plan (Spohr, Citation2021). Ideally, this treatment or support plan would come with details including the nature and course of treatment, the name of the supervising doctor, and location of the treatment (see also Gotsis & Donnelly, Citation2008, p.18). Additionally, the supervising doctor is now more clearly guided to report any breach of the order to the court and Magistrates have 12 months to call the individual back to court if the order is breached (previously this was 6 months). These updates may encourage Magistrates to grant diversions more frequently and foster the development of treatment and support plans that can be undertaken more rapidly. Future research will need to investigate potential changes in diversion practices and outcomes due to these changes.

However, other recommendations from the 2012 NSW Law Reform Commission report have still not been met. For example, due to funding limitations, the ACCT still cannot operate in all Children’s Courts in NSW, raising concerns about young peoples’ access to be initially deemed eligible for diversion, particularly in regional areas. Additionally, the report recommended that a service for case management and support be developed. The NSW Law Reform Commission suggested this service be available at all Children’s Courts in NSW and stated that, “such a service is essential to the successful diversion of young people with cognitive and mental health impairments from the criminal justice system.” (NSW Law Reform Commission, Citation2012, p.384). However, ten years on, such a service is still not available, though a health-led service would likely help facilitate timely health service contact after diversion. Finally, adequate resourcing to ensure the availability and quality of community services is an ongoing issue and one that needs to be resolved to enable the success of diversionary programs (Bradford, Citation2009; NSW Law Reform Commission, Citation2012; Richardson & McSherry, Citation2010).

Factors associated with timely post-diversion health service contact

Young people who were granted a community-based diversion were more than twice as likely to have mental health service contact within 7 days compared to those who were not granted any diversion. The rate was even greater for those granted an inpatient-based diversion, with timely health contact being 10 times more likely. These results suggest that mental health court diversion does indeed increase access to mental health services. However, given that providing individuals with mental health care outside of the justice system is the primary purpose of diversion, the fact that a significant minority of individuals granted diversion do not experience timely contact with mental health services is of concern.

On further univariable analysis, there were few other factors found to be significantly associated with timely health service contact. Individuals whose principal index offense was violent were more likely to receive timely health service contact than those whose offense was nonviolent. Additionally—though not a significant finding—results suggested that women were more than 1.5 times more likely to have health contact within 7 days than men. A recent analysis of the same adolescent court diversion sample found no association between the principal index offense (i.e., violent vs. nonviolent) or sex and the odds of being granted a diversion (Gaskin et al., Citation2022), suggesting any differences in health contact rates go beyond initial diversion decisions by the magistrate. One possible explanation is that individuals who have committed violent offenses and are subsequently granted diversion may be viewed as a priority for treatment, and therefore are referred with greater urgency to mental health services. Further, those on minor offenses are likely to spend less time on remand in custody, and though less time on remand is generally beneficial, it also reduces the opportunity to be flagged by custodial mental health services for potential mental health diversion at court.

Factors associated with reoffending

Young people who were assessed as eligible for mental health court diversion but were not granted diversion at court, had greater odds of reoffending than those who were successfully diverted, as recently found by Gaskin et al. (Citation2022). However, despite the granting of diversion itself being associated with a reduced rate of reoffending, timely mental health service contact following court finalization was not significantly associated with reduced reoffending. However, though not significant in this analysis, there was some indication that health service contact occurring very early (e.g., within 3 days) may be associated with a reduced rate of subsequent reoffending. Some research suggests an association in adults with psychosis between (early) contact with mental health services after an offense (Adily et al., Citation2020) or after diversion (Albalawi et al., Citation2019; Weatherburn et al., Citation2021) and subsequent reduced reoffending. However, no previous research in young people has addressed this question directly in relation to mental health court diversion. Understanding the role that health service contact plays in the relationship between diversion and reduced reoffending will likely require further research within larger cohorts.

Strengths and limitations

While the current study is the first to examine the pattern and correlates of mental health service contact in young people deemed eligible for court diversion, there are a number of relative strengths and limitations that should be noted. First, the study relied on the linkage of administrative data sources and while this minimizes sampling and information biases, the research is limited by the quality and quantity of the available data. For example, the relatively low levels of mental health service contact for those granted community diversion (s 32) may be partially explained by health contacts occurring outside of the investigated databases. For example, an individual who was granted a community-based diversion and saw a private psychiatrist (community or outpatient-based), general practitioner, or NGO would not be detected in the MH-AMB dataset (Albalawi et al., Citation2019). However, because inpatient-based diversions to declared public mental health units should result in recorded hospital admissions (or at least assessments for such admissions) in almost all cases and all such contact should be recorded in the APDC, the findings still raise concern about levels of timely health contact for those with identified mental health need. We also lacked access to other relevant variables beyond those routinely captured in the datasets, preventing us for investigating the reasons underlying magistrate and clinician decision-making in detail. Second, we defined timely health service contact as within one week to identify reasonable prompt contact. Young people failing to attend appointments or administrative delays could affect the rates of health contact within this time period, for example if individuals granted community-based diversions were on waitlists or still waiting for paperwork to be processed before receiving community health services. However, those granted inpatient-based diversions should have more immediate health contact upon court finalization without such delays. Third, although the current study utilizes data collected over 8 years from a cohort of all young people deemed eligible for mental health court diversion, the sample size and individual cells sizes were insufficient to robustly test a number of key hypotheses. Limited statistical power hindered our ability to draw definite conclusions, particularly regarding the association between mental health service contacts and reoffending. Future studies should aim to use larger sample sizes to investigate health contacts in court diversion for young people. Replication with more recent data would also allow for the observation of potential changes in the rates of granted diversions or timely health contacts over time, as well as the impact of changes in mental health legislation or other policies/practices. Finally, the current study setting and context in NSW may not be readily generalizable to other jurisdictions, highlighting the importance of future similar research being conducted elsewhere.

Conclusions and implications

Though previous studies have investigated mental health court diversion processes and reoffending outcomes in young people, this is the first study to examine mental health service contact patterns in young people deemed eligible for mental health court diversion. Young people who were granted mental health court diversion were more likely to have subsequent mental health service contact—at both inpatient and community levels—than those who were not diverted, providing some evidence that the diversion program works as intended. However, timely mental health service contact following court finalization did not occur for a significant proportion of those deemed eligible for mental health court diversion, including those actually granted diversion by the magistrate. If the mental health and reoffending benefits of diversion for young people are to be realized, then the proportion receiving timely care needs to be much higher. The findings of the current study also indicated that there may be some groups of young people who are less likely to receive timely care than others (e.g., those charged with nonviolent rather than violent offenses). The results from this study support the need for properly funded and readily accessible community mental health services for diverted young people. For example, the implementation of a health-led case management service as proposed in the 2012 NSW Law Reform Commission report could improve health service contact rates. Future work should also investigate whether the recent legislative changes have improved the rates of diversion, quantity and quality of treatment plans, and mental health service contacts among diverted young people.

Authors’ contributions

CM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original draft preparation; SS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing—Reviewing and Editing; CG: Conceptualization, Writing—Reviewing and Editing; JK: Conceptualization, Writing—Reviewing and Editing; TL: Conceptualization, Writing—Reviewing and Editing; KD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Reviewing and Editing, Supervision, Funding Acquisition.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committees [see “Ethics Approval” section in manuscript for more details] and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.6 KB)Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network (JHFMHN) for their funding and in-kind support for the researchers employed by them, record linkage, data management, and analysis.

Complete of interest

The authors declare there is no Complete of Interest at this study.

Disclosure statement

We have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 A new act (Mental Health and Cognitive Impairment Forensic Provisions Act 2020) is now in place.

2 Fewer than five individuals granted a s 33 diversion had mental health treatment in the community within one week of court finalisation; due to small group size, we have not included a more detailed description of contact.

3 Data missing for four participants. Note that while this reflects the service provider listed first in the MH-AMB database, there were sometimes multiple types of service providers involved in clinical activities.

4 Fewer than five individuals granted a s 33 diversion had emergency department mental health contact within one week of court finalisation; due to small group size, we have not included a more detailed description of contact.

References

- ABS. (2011). Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2011. Australian Bureau of Statistics. https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/seifa2011?opendocument&navpos=260

- Adily, A., Albalawi, O., Kariminia, A., Wand, H., Chowdhury, N. Z., Allnutt, S., Schofield, P., Sara, G., Ogloff, J. R. P., O'Driscoll, C., Greenberg, D. M., Grant, L., & Butler, T. (2020). Association Between Early Contact With Mental Health Services After an Offense and Reoffending in Individuals Diagnosed With Psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(11), 1137–1146. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1255

- AIC. (2011). Court-based mental health diversion programs. Australian Insitute of Criminology. https://www.aic.gov.au/publications/rip/rip20

- Albalawi, O., Chowdhury, N. Z., Wand, H., Allnutt, S., Greenberg, D., Adily, A., Kariminia, A., Schofield, P., Sara, G., Hanson, S., O'Driscoll, C., & Butler, T. (2019). Court diversion for those with psychosis and its impact on re-offending rates: Results from a longitudinal data-linkage study. BJPsych Open, 5(1), e9. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.71

- Barrett, J. G., Flores, M., Lee, E., Mullin, B., Greenbaum, C., Pruett, E. A., & Cook, B. L. (2022). Diversion as a pathway to improving service utilization among at-risk youth. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 28(2), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000325

- Boothroyd, R. A., Poythress, N. G., McGaha, A., & Petrila, J. (2003). The Broward Mental Health Court: Process, outcomes, and service utilization. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 26(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-2527(02)00203-0

- Bradford, D. S. (2009). An evaluation of the NSW court liason services. N. B. o. C. S. a. Research. https://www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au/Publications/General-Series/r58_cls.pdf

- Broner, N., Lattimore, P. K., Cowell, A. J., & Schlenger, W. E. (2004). Effects of diversion on adults with co-occurring mental illness and substance use: Outcomes from a national multi-site study. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 22(4), 519–541. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.605

- Colwell, B., Villarreal, S. F., & Espinosa, E. M. (2012). Preliminary Outcomes of a Pre-Adjudication Diversion Initiative for Juvenile Justice Involved Youth with Mental Health Needs In Texas. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 39(4), 447–460. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854811433571

- Cuellar, A. E., McReynolds, L. S., & Wasserman, G. A. (2006). A cure for crime: Can mental health treatment diversion reduce crime among youth? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management: [the Journal of the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management], 25(1), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20162

- Davidson, F., Heffernan, E., Greenberg, D., Butler, T., & Burgess, P. (2016). A Critical Review of Mental Health Court Liaison Services in Australia: A first national survey. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 23(6), 908–921. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2016.1155509

- Davidson, F., Heffernan, E., Greenberg, D., Waterworth, R., & Burgess, P. (2017). Mental Health and Criminal Charges: Variation in Diversion Pathways in Australia. Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law: An Interdisciplinary Journal of the Australian and New Zealand Association of Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 24(6), 888–898. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2017.1327305

- Fox, B., Miley, L. N., Kortright, K. E., & Wetsman, R. J. (2021). Assessing the Effect of Mental Health Courts on Adult and Juvenile Recidivism: A Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 46(4), 644–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-021-09629-6

- Gaskin, C., Singh, S., Soon, Y.-L., Korobanova, D., Hawes, D., Lloyd, T., Kasinathan, J., & Dean, K. (2022). Youth mental health diversion at court: Barriers to diversion and impact on reoffending. Crime & Delinquency, 0(0), 001112872211227. https://doi.org/10.1177/00111287221122755

- Gotsis, T., & Donnelly, H. (2008). Diverting mentally disordered offenders in the NSW Local Court. Judicial Commission of New South Wales. http://www.judcom.nsw.gov.au/monograph31/monograph31.pdf

- Heretick, D. M. L., & Russell, J. A. (2013). The Impact of Juvenile Mental Health Court on Recidivism Among Youth. Journal of Juvenile Justice, 3(1), 1–14.

- Herinckx, H. A., Swart, S. C., Ama, S. M., Dolezal, C. D., & King, S. (2005). Rearrest and linkage to mental health services among clients of the Clark County Mental Health Court Program. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 56(7), 853–857. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.56.7.853

- HNE Kids Health (2023). Child and adolescent mental health services. HNE Kids Health. https://www.hnekidshealth.nsw.gov.au/facilities/community_based_services/new_england/mental-health

- Iskra, W., Deane, F. P., Wahlin, T., & Davis, E. L. (2018). Barriers to services for young people. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12, 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12281

- Mulraney, M., Lee, C., Freed, G., Sawyer, M., Coghill, D., Sciberras, E., Efron, D., & Hiscock, H. (2021). How long and how much? Wait times and costs for initial private child mental health appointments. J Paediatr Child Health, 57, 526–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.15253

- NSW Law Reform Commission. (2012). People with cognitive and mental health impariments in the criminal justice system - Diversion. https://www.lawreform.justice.nsw.gov.au/Documents/Publications/Reports/Report-135.pdf

- Richardson, E., & McSherry, B. (2010). Diversion down under—Programs for offenders with mental illnesses in Australia. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 33(4), 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2010.06.007

- Spohr, T. (2021). The new mental health legislation: The Mental Halth and Cognitive Impairment Forensic Provisions Act 2020 (NSW) - An outline of the changes. https://www.legalaid.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/53077/The-new-Mental-Health-legislation-Thomas-Spohr.pdf

- The Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (2023, March). The NSW mental healthcare system on the brink: Evidence from the frontline. Report - Clinicians Global Impression Survey. https://mhcc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/NSW-Mentalhealth-system-on-the-brink.-Evidence-from-the-frontline.pdf

- Weatherburn, D., Albalawi, O., Chowdhury, N., Wand, H., Adily, A., Allnutt, S., & Butler, T. (2021). Does mental health treatment reduce recidivism among offenders with a psychotic illness? Journal of Criminology, 54(2), 239–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004865821996426