Abstract

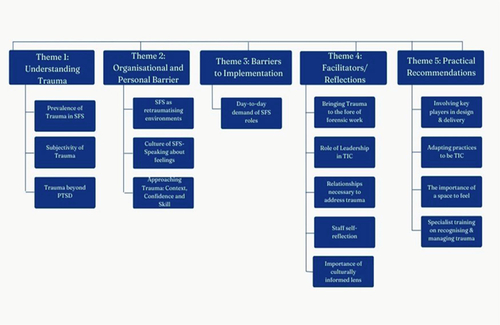

The prevalence of trauma within secure forensic populations is widely acknowledged, yet the implementation of trauma-informed care (TIC) in secure forensic settings (SFS) remains in its infancy. This qualitative study delves into the perceptions and experiences of healthcare professionals (HCPs) adopting a TIC framework in SFS, examining associated barriers and facilitators. 15 participants engaged in semi-structured interviews, and results underwent thematic analysis, yielding five overarching themes and 15 sub-themes. Themes identified include: 1) understanding the TIC experience in SFS, 2) organizational and personal barriers in TIC implementation, 3) facilitators and reflections on TIC benefits, 4) barriers to specific TIC practices, and 5) practical recommendations. Participants emphasized the prevalent nature of trauma in SFS and underscored the perceived advantages of creating spaces for reflection and emotional well-being. Interviewees explored the impact of organizational culture, the demands of frontline roles and training accessibility. Practice implications highlight the need to involve key stakeholders (staff and SUs) in decision making and in assessing the feasibility of implementing TIC. SFS should prioritize TIC by addressing training needs, allocating time for TIC in supervision, providing specialist support for trauma-informed clinical work, and ensuring dedicated spaces for reflection. While the study highlights the power of incorporating HCP perspectives, limitations arise from findings drawn from a single forensic service, emphasizing the importance of further replication. This research contributes valuable insights into advancing trauma-informed care practices within secure forensic settings.

Trauma has been repeatedly linked to increased risk of mental health (MH) difficulties along with poor prognosis (McKay et al., Citation2021). Trauma may be the outcome of “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotion, or spiritual well-being” (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, Citation2014, p. 7). This encompasses both Type I trauma, involving single, discrete traumatic incidents like accidents or assaults, and Type II trauma, characterized by prolonged or repeated exposure to events such as abuse or neglect within interpersonal relationships. Research has demonstrated the link between trauma exposure and complex/severe MH difficulties, including mood and anxiety disorders (Sareen et al., Citation2012), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Bianchini et al., Citation2022), increased polysubstance use (Brockie et al., Citation2015), and psychotic disorders (Trotta et al., Citation2015); as well as longer/recurrent hospitalization in MH institutions (Edwards et al., Citation2003; Reddy & Spaulding, Citation2010). Trauma is elevated in forensic populations (Folk et al., Citation2021; Ranu et al., Citation2022), and has been identified as a risk factor for engaging in violent behavior in general and MH populations (Mancke et al., Citation2018), and increased risk of admission to secure forensic settings (SFS) (Karatzias et al., Citation2019).

Health care professionals (HCPs) working with service users (SU) who have experienced elevated levels of trauma face greater risk of burnout, compassion fatigue, and PTSD (Blau et al., Citation2013; Jacobowitz et al., Citation2015). Vicarious trauma (VT), the experience of symptoms akin to PTSD among professionals who work in caring or healthcare roles (Chouliara et al., Citation2009), is also higher among individuals working in forensic/correctional settings, due to witnessing scenes of violence, patient distress, and seclusion (Frost & Scott, Citation2022; Isobel & Thomas, Citation2022).

There is growing interest in the implementation of Trauma Informed Care (TIC) among both researchers and clinicians, particularly in SFS. TIC is an established framework used in correctional settings and MH services aimed at recognizing the effects of trauma and mitigating its negative effects to both SUs and HCPs, by reducing risk of re-victimisation and re-triggering of trauma (Covington, Citation2022; Harris & Fallot, Citation2001). The principles that comprise TIC are safety, trustworthiness and transparency, peer-support and mutual self-help, collaboration and mutuality, and empowerment, voice, and choice (SAMHSA, Citation2014). TIC approaches aim to promote the development of empowering and compassionate environments where SUs’ experiences are considered by all staff (clinical and non-clinical).

TIC has been systematically reviewed and explored as a model in various settings such as in psychological interventions (Han et al., Citation2021), inpatient settings (Muskett, Citation2014) and SFS (Maguire & Taylor, Citation2019). TIC approaches have been associated with greater treatment engagement and improved outcomes, such as decreased inpatient hospitalization and recidivism among forensic SUs (Azeem et al., Citation2011; Miller & Najavits, Citation2012). Studies have further identified enhanced collaboration and coordination among staff, as well as improved staff satisfaction and organizational commitment following the implementation of TIC practices (Muskett, Citation2014).

Research on staff experiences of TIC is limited. Vaswani and Paul (Citation2019), reported prison staff members’ lack of confidence and perceived skill in talking about trauma. Similarly, O'Dwyer et al. (Citation2021), highlighted challenges to TIC in psychiatric inpatient settings, including a sense of inadequacy and fear of criticism when responding to trauma, which was associated with supervision avoidance. In general MH settings, with SUs with traumatic experiences, Truesdale et al. (Citation2019) demonstrated the presence of organizational and interpersonal barriers in implementing TIC, such as lack of training and funding, and time constraints. These studies acknowledge that TIC is a crucial component of support for SUs with trauma (Truesdale et al., Citation2019). Considering the high levels of trauma in SFS, and benefits associated with TIC, qualitatively examining the perspectives of HCPs working in SFS would offer important and novel insights that could aid the development of clinical practice and policy.

The current study aimed to explore the experiences and perceptions of HCPs working in SFS across disciplines on the barriers and facilitators encountered in the implementation of TIC. We involved different professional backgrounds and varying levels of training and management level. It aimed to explore staff members’ perceptions of trauma, their experiences of the use of training, supervision, and reflective practice as factors promoting TIC, and elicit specific future recommendations. These recommendations could inform strategies for refining and enhancing TIC practices to better address the challenges identified by HCPs; using the staff ‘voice’ to create practical clinical change (Morrow et al., Citation2016).

Methods

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Bath Research Ethics Committee (PREC: 22-003 M). Additionally, local approval was granted by the current NHS Trust. Information was stored and processed in line with General Data Protection Regulation.

Participants

Recruitment was conducted via purposive sampling. Participants were informed of the study by the distribution of emails to staff accounts, and the dispersion of information leaflets that were left in shared staff spaces. Inclusion criteria were being over 18, employed as HCPs within the service in inpatient low or medium SFS or community services, being fluent in English and having capacity for informed consent. Individuals working within SFS with no clinical interaction with SUs were excluded.

Sample size

The optimal range of participants for a sample as defined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2019) was between 10-15 participants; 17 participants were interviewed, with two excluded due to poor audio quality ().

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants.

Materials

Interview protocol

The semi-structured interview used was piloted and adjusted following participant feedback, comprising of 15 open questions regarding: 1. Participant awareness and implementation of TIC principles; 2. Facilitators and barriers experienced to implement TIC principles; and 3. Recommendations for policy and clinical practice.

Procedure

Data collection

All participants received study information and provided written and verbal informed consent, before taking part in the study. A risk management plan was developed due to the sensitive nature of the topic. Participation in the study was voluntary, and participants could remove themselves from the study at any point. Interviews were conducted online or face-to-face within the service, depending on participants’ availability. In total, 10 remote and seven in-person interviews were conducted, between April-June 2021. Interview duration was between 30 min to 1-h. Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim for analysis, and anonymised to protect participant identity. Participants were provided with a debrief sheet that outlined the key aims of the study, how information would be used and details on how to seek support at the potential experience of distress.

Data analysis

Interviews were analyzed using TA (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). Data management was supported by NVivo (NVivo, Citation2021). Interviews were analyzed using the 6-stage Thematic Analysis framework as described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2019); this process involves becoming familiar with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing the themes (in this case with the input of other coders for reliability measures), defining the themes, and writing them up. The interview protocol and data analysis were primarily conducted by the lead author. A second and third coder was invited to code all interviews to ensure the reliability of the process.

After a process of familiarization, a coding framework was developed based on the interview topic guide and simultaneous coding of the first seven interview transcripts by implementing an inductive approach. This was agreed by two authors (DS and EM). The initial coding framework developed, was applied to the remaining data set, and then reformulated by a team discussion between coders (DS, EM and LK).

To enhance TA, saliency analysis was included (Buetow, Citation2010). Saliency analysis aided the researcher to identify recurring codes, as well as acknowledge non-recurrent, but equally significant codes which were useful to address the aims of the study. After the final organization of the codes, semantic themes were developed.

Finally, themes were reviewed/re-organised multiple times, with consultation with the second and third coders. Themes were labeled appropriately with the scope to best describe their content (codes; Boyatzis, Citation1998). Thematic maps were developed to further enhance the researcher’s understanding and organization ().

Results

Participant information

Participants were between 25 years to 65 years (M = 42.00 SD = 41.93). 26.66%(n = 4) were trainees and assistant psychologists. 86.67% (n = 13) reported that they have daily contact with SUs, and only 13.33% (n = 2) have stated that they currently have infrequent contact with SUs. HCP’s participating in this study included Psychologists, Assistant Psychologists, Trainee Psychologists, Psychiatrists, Mental Health Nurses, Social-workers, Occupational-therapists, Art-therapists, Ward-managers, and the staff from the Senior Management team (SMT) (see ). 40% of participants worked across both low and medium, s, 33% worked in medium and 26.7% in low SFS. and had received varying levels of training in TIC (). The average length of time working within the current service (SFS) was an average of 11.26 years.

Qualitative analysis

Five major themes and 15 subthemes () emerged during the thematic analysis.

Theme 1: Understanding experience of trauma in SFS

The first theme concerned participants’ understanding of the role of trauma and issues raised in defining trauma.

Theme 1a. Trauma is highly prevalent in forensic settings

All participants described that trauma is highly prevalent in SFS, and eight participants recognized that most SUs have a history of trauma.

“Lots of our clients, come from very disadvantaged backgrounds with lots of health experiences and traumatic experiences” (P06)

“Almost half of them or more have gone through trauma in the past” (P08)

Four participants with nursing and psychiatry backgrounds expressed the belief that trauma is at the root of difficulties, even when unrecognized:

“A lot of traumas in the background that we might be missing… we see someone who’s got schizophrenia, someone who’s committed a crime… but we’re not really going deeper and trying to understand how they got to where they are” (P09)

“Knowing what they witness (on the wards) I say they could have been traumatised, I focused on the patient, but I forgot (how it impacts) my staff” (P05)

“Vicarious trauma of listening to peoples’ experiences can be really difficult” (P07)

Theme 1b. Subjectivity of what constitutes trauma

Four participants raised the issue concerning the subjectivity of the definition of trauma and especially the role of cross-cultural norms of what constitutes a traumatic event.

“Trauma comes in all forms. Yes, and what I perceive as traumatic, someone else may not at all and vice versa” (P12)

“But she did not see it as a rape because in their culture there is no such thing as you can be raped by your husband, you can be raped by a stranger but not my husband” (P06)

Theme 1c. Trauma beyond PTSD?

Six participants also negotiated how we perceive and define trauma in the context of training, using a medical model. It was highlighted that adverse experiences or interpersonal, often chronic or early life, trauma (complex) is at times neglected. This was distinguished from “Criterion A” traumatic events (e.g. horrific, life-threatening incidents) as defined in the context of PTSD.

“With this population it tends to be… rather than an acute trauma… like when we look at the DSM and the criteria for PTSD, they might not meet that, but they had a lot significant, early life traumas, like attachment-based trauma” (P11)

“People who have experienced wars, that they have an experience people like dead bodies and those kinds of things is different from maybe somebody, who has gone through like domestic abuse even though the person hasn’t experienced any death”. (P08)

Two participants expressed the worry that this distinction adopted by diagnostic models lead to minimizing of these traumatic experience:

“I think sometimes it almost gets lost because there’s so many difficult things that we don’t see it as one significant event in the same way that we do as like PTSD” (P12)

“And because we think trauma has to be horrific major events, when it isn’t it’s minimised.” (P13)

Theme 2: Organizational and personal barriers

Many participants recounted their perceived organizational and personal facets that would potentially act as a barrier to TIC practices.

Theme 2a. Organizational- forensic settings as re-traumatising environments

Eight participants, predominantly from psychology (50%), described the challenge of thinking about trauma and using TIC in a SFS, such as the use of restrictive practices, high levels of security and seclusion.

“The higher levels of security you have the harder it’s going to be… restraining them and put them in seclusion and all those things. It’s kind of the anti-trauma informed care” (P01)

“There is no doubt that being in secure mental health services is traumatising. Even if you don’t end up in the seclusion, you’re locked away. It would strange people that have mental health conditions and some of them might be aggressive.” (P10)

Two participants focused on the physical characteristics of the wards, such as the ward atmosphere.

“It’s a very loud, very noisy ward, medium secure ward and sometimes that noise and chaos and arguing between different patients … for someone who experienced lots of trauma or witnessed domestic violence might be retraumatizing” (P06)

Theme 2b. Culture of forensic settings-speaking about feelings

Five HCPs reflected on aspects of the culture of SFS that is not in harmony with TIC approaches. Despite recognizing the need for reflective spaces, HCPs shared that there is no time for feelings when working in SFS, highlighting the need to be “tough”, a culture of machismo, and practices that can be perceived as punitive when responding to challenging behavior. This was linked by some to the focus on the index offense among professionals, which can make it difficult for staff to separate the person from their actions. Overall, this organizational culture was described as impacting empathic practice but also causing conflict in teams.

“In a forensic setting where there still exists a bit of machismo, or you know we are tough we can handle it” (P01)

“So, then people tend to focus on that and uh, they’re a bad person and all they focus on the difficult, challenging behaviours that we have here, which is drug use, absconding, violence, it’s a barrier to thinking about trauma…. You are told you are being too soft” (P15)

Within this culture, four participants identified a reluctance by staff to talk about their own feelings, perceiving it as “weakness or vulnerability” and feeling embarrassed.

“Most of the time people feel embarrassed, like they failed because at doing their job because they’re struggling… that this is our job we just have to don’t get on with it there’s no time for feelings it’s that’s kind of airy fairy… how can we let service users do it if we can’t do it as professionals” (P01)

Finally, five described their perceived divide between the medical or diagnosis focused and legal contexts of forensics and TIC approaches, suggesting that it limits how much space exists to explore the impact of trauma. They explained that different professions have their unique trainings (e.g., medical), which might go against the ethos of a TIC approach.

“Some consultants aren’t willing to accept thinking in a different way and it’s hard to challenge…during a ward round a patient will come in and consultant will say well your diagnosis is this and this means that your mental illnesses X and this is the medication you’re taking… there’s no space to even think about what’s happened to a person” (P01)

“You very rarely see people who have just have a psychotic illness… Often is a much bigger picture of bad kind of adversity and trauma that needs to be thought about more” (P10)

Theme 2c. Approaching trauma: Context, confidence, and skill

Eight participants reflected on staff reluctance to address trauma as a barrier to adopting TIC. One reason involved the worry that touching upon the topic of trauma in the forensic context could be retraumatising or un-containing to patients.

“Sometime is not the right time. It’s not the right setting. Being in a situation that might be perceived as triggering or traumatising, like being in hospital, being locked up, and like experience similar things that has happened in childhood” (P10)

“If you’re in a place that’s kind of difficult for you to be in, this potentially is a triggering environment, that’s probably not the best place to process your trauma” (P11)

Three participants, all of which were assistants or trainee psychologists, highlighted that this difficulty was compounded by their own lack of confidence due to their experience of limited training.

“On a personal level perhaps sometimes thinking, you know questioning myself, “am I doing this right” “is it how it’s supposed to be” you know, “do I know enough” you know I'm not an expert in this area…” (P07)

Theme 3. Barriers in the implementation of TIC practices (reflection, supervision)

Subtheme 3a: Day to day demands of SFS roles leaves no time for training

A prominent barrier to the implementation of TIC, identified by 10 HCPs, was the day-to-day demands of the work of frontline staff, which impacted the time and space allocated to discussing feelings and reflecting, or attend training. A link was made with their highly demanding roles and caseloads, understaffing, and time constraints.

“The nursing staff particularly are the ones that find it hardest to access training because of course they’re on shift” (P02)

“It’s so busy that we very rarely have the time to just take an hour out and think about what’s going on, on the ward or in our practice” (P07) or “to even sit down to reflect” (P08)

A few participants described challenges in implementing, attending and making use of trauma-informed care practices. This included supervision turning into case management.

“They’ll see supervision as okay have you done all your HCR-20s have you done all these… a head of nursing is trying… to get people to think a bit more broadly about supervision, but there’s quite a lot of resistance there” (P01)

” Supervision is often focused on tasks, and I think the social work tasks are quite practical and sometimes that takes up quite a lot of time, there isn’t always that much time for exploring things related to trauma with patients” (P14)

When discussing reflective practice, some participants described that it is an emotionally challenging experience.

“There have been times where I wanted to bring things up in reflective practise, but it didn’t feel like the right moment or a safe place… so it gets uncomfortable…sometimes I just feel very anxious to bring things up.” (P03)

Five other participants reflected on the worry that reflection will lead to blame or judgment:

“Blame as well, I don’t know my personal reflection it may end up being quite self-critical" (P12)

Theme 4: Facilitators/reflection- how to keep trauma in mind

Theme 4a. Having trauma in the forefront of forensic work

Eleven participants across disciplines emphasized the importance of bringing trauma to the forefront of forensic practice, including implementing mandatory training on TIC in a practical format.

“How do you get staff trained and ensure that it’s actually being implemented effectively” (P09)

“I'd love to make it mandatory to have a course on TIC. Keeping it practical showing, using a video, people trying to develop an understanding is vital. it’s got to be at the core values. (P13)

However, several participants emphasized the role of “keeping trauma in mind” daily beyond training, as a necessary part of the culture.

“People can do all the training days but unless they start to see it in action on a day-to-day basis and have a weekly space where they can talk about it… It seems to me that that’s the only way we can continue to really embed and implement the thinking process” (P01)

“It’s having a culture on a day-to-day basis within, you know, going on each day about how you maintain that and would take the dialogue about that and not have a culture of just reacting to things” (P14)

Five participants emphasized that this shift should take place through an integration of trauma-informed approaches with the medical and legal practices in SFS. One participant from a psychiatric background reflected positively on implementing trauma-informed interventions beyond the main diagnosis.

“It really is such a shift of understanding from the people who are giving out the diagnosis and giving out the medication and not to say that those things don’t have a place which they do but it’s also how that fits in with understanding what someone’s been through so that’s a sticking point” (P01)

“I think we recognise it in that patient a bit more, rather than just treating, in that case, is clearly a mental disorder like schizophrenia, whereas the other patient was clearly PTSD, with schizophrenia we are still implementing therapies that we use in PTSD, and is having a good effect on him, which I wouldn’t necessary done before” (P12)

Theme 4b. Role of leadership in TIC

Participants with higher level of seniority (management/consultant level) advocated that the change in the service should be led from the top down, creating a culture that offers opportunities for and evaluates using TIC as a framework.

“Yeah, I think organizationally there has to be the backing of senior managers” (P02)

“Everyone is on board and it a top-down sort of implementation where you know managers… are fully on board and encouraging people to get this implemented but otherwise without that I think it will be very difficult” (P09)

Theme 4c. Relationships as necessary to address trauma

On an interpersonal level, four participants indicated that they feel a relationship based on trust is necessary prior to addressing trauma in their therapeutic work with clients.

“Get to build a relationship with them where they may comfortably discuss with you, because I supposed to go back to your previous question that people feeling comfortable or having a therapeutic relationship or alliance with people, I think is it’s really key, so if you don’t have, that’s the real challenge to me.” (P10)

Theme 4d. Staff self-reflection

Eight participants described the importance of staff self-reflection. Participants from psychology backgrounds described an awareness and appreciation for reflection, while those from a nursing background additionally discussed the difficulty of incorporating reflection into their busy days. Participants reflected on the benefits of using supervision and reflective practice: a chance to reflect about the impact on their own wellbeing, and the reduction in staff stress levels and burnout when working with trauma.

“I think it’s really important because I think by reflecting on it, that’s how you learn, and it also reduces the likeliness of, I guess you becoming burnt out or stressed or traumatized through the things that we kind of deal with, whether it’s second hand or first-hand experiences” (P15)

What you’re hearing and what you’re absorbing every day is really challenging. And I think to have a space to talk that out and to examine how it’s impacted you is really important (P11)

Ten participants across disciplines described that self-reflection is necessary to support patients from a trauma-informed perspective, including exploring individual biases and triggers, but also allowing alternative viewpoints and improving their practice through supervision.

“But before dealing with that I have to deal with myself first, the impact on me and then from there I can help my team, I can help my patient” (P05)

“I have my own biases and judgement that I bring into my work and its good practise to reflect and maybe think of a different approach” (P03)

Theme 4e. Importance of culturally informed formulation

Three participants reflected on the importance of formulating through the lens of culture and the interaction between the individual and the broader system.

“You’ve got the client and they’ve got their family system and the cultural system and all of the different systems that they grew up in. And then our staff have the same and those systems overlap and interlink… So, thinking trauma-informed care from a broader lens of not just the individual but about the ward environment, how it impacts the staff and the people working with the patients” (P10)

Theme 5: Practical recommendations

Theme 5a. Involving key players in design and delivery

Seven participants with greater contact with SUs, suggested that it is essential to involve the “key players” when designing and implementing TIC; including involving SUs and frontline staff in making decisions.

“We need a forum for people to share, like webinars for people to listen… Maybe experts by experience, people that have gone through trauma”

“So, for example if I made changes to a policy about supervision or who needs to attend reflective practice, I might suggest changes which actually sound good on paper but not possible to do for practical reasons… therefore the discussion (with nursing staff) needs to take place (P06)

One suggestion involved psychological professionals supporting staff members from other disciplines, especially nursing staff, to integrate TIC skills:

“Rather than psychologists doing lots of 1:1 work and group work, if psychologists could supervise nursing staff and social workers. So that they kind of, support them to develop that psychological and trauma-informed mindset.”

Theme 5b. Adapting specific forensic practices to be TIC

One specific recommendation made by six participants across backgrounds concerned the adaptation of processes in SFS to be more trauma informed. This included reviewing processes/policies such as seclusion (n = 4) and ward rounds (n = 3).

"I know it’s been done before but focusing on the ward round process… just in terms of trying to think about those spaces…any sort of area where re-traumatization could happen (P01)

“I think it’s important having a section in our seclusion reviews, in our most restrictive practises” (P13)

One participant raised the worry that focusing a trauma removes a person’s accountability for their actions:

“I do worry that the more you focus on trauma you take away personal responsibility in the moment for people’s actions or behaviour… It is a balancing act. But I think at the moment we are far too on the side not focusing on enough (on trauma)” (P10)

Theme 5c. Space to feel

Six participants recommended the establishment of physical and psychological spaces for staff and SUs. Regarding physical spaces, a few participants recommended creating a friendlier ward environment for SUs. Participants also suggested a dedicated physical space for staff to talk about potential incidents on the wards, such as a “TIC room” which staff could use to decompress when required. This idea has been subsequently rolled out in the service and had success in practice with the staff. It was also emphasized that protected and regular time should be allocated to staff across disciplines to reflect. Three participants suggested one-to-one psychological support should be offered when necessary.

So, what I recommend is for us to be given enough time to sit down because reflection needs bit of time for you to sit down. (P08)

Absolutely having a regular time to meet, to be open and discuss concerns is vital because it’s about that relationship. If it’s my boss or someone of my staff, I'd like to think there is that openness. (P13)

"Looking into offering one-to-one support available for people” (P01, P03, P08)

Six participants recommended bringing external staff or staff specializing in offering reflective practice or working with trauma.

“Somebody else comes in from like a different perspective who doesn’t know the service or the client and brings a new perspective and sometimes that makes me really ask questions” (P03)

“' I feel that people who would deliver reflective space yet need to be trained have an awareness of where they’re going with it” (P04)

Theme 5d. Specialist training on recognizing and managing trauma

Five staff highlighted the need for additional training on recognizing and managing trauma in SFS.

“I think it would be really useful if the wider MDT, some specialties that we work with may not have as much experience in trauma. So, if they could have more training or more understanding” (P10)

Discussion

Our study exploring HCPs’ perceptions of working from a trauma-informed perspective in SFS, identified five main themes: understanding experience of TIC in SFS, organizational and personal barriers, barriers in the implementation of TIC practices (reflection/supervision), facilitators/reflections-how to keep trauma in mind and practical recommendations.

In defining and acknowledging the high prevalence of trauma, participants highlighted the subjectivity and cross-cultural relevance of what is traumatic (Lemelson et al., Citation2007). Certain topics arose as crosscutting across themes: the potential clash between a medicolegal approach and TIC; the presence of an organizational culture in SFS that might be perceived as punitive by patients; the high demands but perceived limited support to frontline staff; and the absence but need for a space to feel and reflect on trauma.

One prominent idea centered around the inherent differences of a trauma-informed approach vs the medical model, which was noted by participants across medical and therapy disciplines. This began with the concern that the focus is on type I trauma (single event, such as a serious accident), leaving type II trauma (chronic and often interpersonal exposure) (Terr, Citation1991) neglected. This is especially relevant to the complex and severe mental health difficulties observed in SFS, as we know that complex trauma is associated with more severe changes in emotion regulation and interpersonal relationships. Similarly, this focus excludes the acknowledgment of the impact of marginalization, racism, or the collective memory of ethnic violence (Blanch et al., Citation2012). In our sample the perception arose that an over-emphasis on diagnosis and one’s index offense acted as a barrier to both offering adequate support to SUs and to developing an accurate formulation of factors predicting therapeutic outcomes. Past studies have noted the challenge posted to TIC (Sweeney et al., Citation2018), by resistance to moving beyond the biological basis of behavior (Moskowitz, Citation2011). Overall, results point to the necessity for an individualized biopsychosocial and culturally sensitive approach to conceptualizing the impact of different forms of trauma.

The present study further identified a core role of organizational culture in working with trauma and adopting a trauma informed perspective. For example, the study identified a sense of an underlying ‘macho’ culture being present in SFS, characterized by some as involving using restrictive practices in a punitive manner, and attitudes toward SUs to appear “tough and strong” and avoid any signs of vulnerability. Even though this phenomenon was reported by a small number of participants, it is consistent with previous research conducted in a prison setting (Markham, Citation2022; Vaswani and Paul (Citation2019); Wooldredge, Citation2020). This culture partially reflects the aforementioned dominance of medical and legal models (Wooldredge, Citation2020), and clearly opposes the trauma-informed principles of being empathetic (Knight, Citation2015), collaborative and empowering, which when correctly implemented minimizes seclusions and restraints through collaboration and coordination among staff (Azeem et al., Citation2011)

Such an organizational culture may be interdependent with the limited time devoted for frontline staff’s reflection, and the belief of emotions as an indicator of weakness and vulnerability. SFS are environments characterized by elevated levels of vicarious trauma and emotional intensity, often associated with the experience of desensitization, as described in our study, and the activation of survival strategies, including avoidance, detachment, and not reflecting (Addo, Citation2006), making the need for a holding space paramount. Staff avoidance may be reinforced by the high workloads (Goldstein et al., Citation2018), and limited opportunities and challenges in making use of reflective practice and supervision as central processes to TIC (O'Dwyer et al., Citation2021). Connecting this to the sometimes disproportionately restrictive stance identified among staff, staff members working in challenging environments over extended periods have been found to resort to previous working practices (more punitive) and less TIC approaches (Baker et al., Citation2018).

The expression of worry and perceived lack of skills to support traumatized SUs, mostly identified among participants at lower levels of seniority, extends past findings on MH professionals lack of confidence to address trauma in general MH (Copperman & Knowles, Citation2006) and prison settings (Vaswani and Paul (Citation2019)), particularly when these are characterized by lack of trust (Sweeney et al., Citation2018). Insight on the role of trauma was emphasized in facilitators and recommendations, echoing previous studies which showed its role in shaping a safer environment (Farro et al., Citation2011) and in minimizing re-traumatisation among both staff and SUs (Elliot et al., Citation2005; Gatz et al., Citation2007).

Finally, some participants highlighted the role of creating rapport and offering an individualized and culturally sensitive approach to explore the subjective experience of trauma. Relationships are central for survivors of trauma to feel safety and trust, and experience different ways of relating (Van der Kolk, Citation2014) that can have a reparatory function, in contrast to previously betraying or unsafe environments (Sweeney et al., Citation2018). Indeed, Western psychiatric diagnosis may fail to capture the variability of trauma responses, such as unique idioms of distress and ideas of illness from different cultural context (Patel & Hall, Citation2021). The opportunity for reflection on cultural biases and the safe exploration of cultural identity have been suggested as central tenets to trauma-informed interventions (Blanch et al., Citation2012), and should be adopted across processes of assessment, formulation and rehabilitation.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide a platform for SFS staff to voice their perceived barriers and facilitators in employing TIC, and their recommendations, demonstrating this study’s novelty. The wide recognition of trauma’s prevalence among SUs and staff highlights the relevance of this study to SFS. A major strength of the present study lies in including HCP from different disciplines and backgrounds, but also varying levels of security, length of service and seniority, adding to this study’s generalizability. The study was also initially piloted, to ascertain comprehension and make necessary adjustments. A reliability measure was included, with two coders coding all interviews, forming and reviewing themes and subthemes through multiple discussions in the research team.

However, certain study limitations need to be considered. Despite attempts to include HCPs from different disciplines, nursing professionals, who have 24-hour direct contact with SUs who have experienced trauma, were underrepresented. Although an important limitation, this reflects the time constraints faced by nursing staff highlighted in this study. Participants were drawn from a single forensic service, limiting finding generalizability. Furthermore, as the rolling out of TIC has been an endeavor of recent years in the service, quantifying the level of TIC training participants had received was a challenge. As such, our results can be better conceptualized as participants’ perceptions and beliefs about the current challenges of working with trauma and barriers in the actual or potential implementation of TIC, rather than an evaluation of an intervention. Finally, as our study took place closely to the time of the covid-19 pandemic, staff perceptions around organizational responses to incidents, training availability, and their own wellbeing could have been impacted by the additional restrictions and heightened levels of stress during this period.

Practice implications

Multiple participants stressed that TIC should be put at the forefront of SFS and emphasized the service’s key organizational role in promoting TIC in a top-down fashion, followed by specific recommendations on potential adaptations, in line with previous organizational recommendations for correctional and mental health settings in the seminal work of Covington (Citation2022) and Harris and Fallot (Citation2001). These recommendations would contribute to an improved working environment and higher workforce sustainability in SFS (Oates et al., Citation2020). The need for 1) appropriate training, 2) supervision, 3) space for reflection identified, in keeping with previous research in SFS (Oates et al., Citation2020), offers 3 concrete areas of implementation. In line with these recommendations, the following implications arise for the implementation of TIC in SFS:

Involve trauma specialists and experts by experience in the co-production and delivery of training in line with the TIC principle of peer support (SAMHSA, Citation2014).

Managers should collaboratively explore the individual training and support needs of frontline staff, from the onset of staff’s induction (Hummer et al., Citation2010). Effective orientation programmes have previously included topics such as trauma, substance misuse, peer support and empowerment, and therapeutic safety and boundaries (Azeem et al., Citation2011). Staff capacity to attend training should be evaluated and opportunities created, and feedback should be sought on the accessibility and benefits of training. This would also support staff retention in SFS (Oates et al., Citation2020), creating more sustainable working environments.

Establish space to think about trauma in daily processes relevant to general MH settings (team meetings, ward rounds, supervision) and offer 1:1 psychological support when relevant to staff members.

Review and continuously evaluate the processes and policies specific to SFS (seclusion, seclusion reviews, CCTV, patient restriction) to ensure their implementation in a manner that promotes respect, fairness and dignity (Covington, Citation2022).

Establish protected spaces with dedicated time and specialist external facilitation to discuss working with trauma and complexity. An emphasis should be placed on the confidential and non-judgmental nature of these spaces.

For instance, following the recommendations of this study, the specific service implemented a range of the aforementioned changes, including a TIC group to reflect on current initiatives and further incorporate TIC principles. A physical space to “de-compress” has been established in the service, and a revision of protocols took place to ensure TIC principles are considered. In addition, reflective practice is being rolled out at a ward level, and wellbeing discussions have been incorporated as a supervision component for staff.

Future research

Future research should consider replicating this study across different services in the UK with the aim to generalize the present findings. The field would also benefit from a more in-depth qualitative analysis of cultural factors, including the cross-cultural sensitivity of working with trauma, but also the described “macho” culture of SFS, using approaches with a higher degree of reflexivity, such as ethnography. As a next step, future research should extend the current study by providing SUs with an opportunity to offer their unique insights on their experience of trauma-informed interventions, including the acceptability of individual interventions but also of forensic processes, to ensure the representation of lived experience.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge participating staff members of SFS for their contribution.

Conflict of interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- Addo, M. A. (2006). The unseen abyss: registered nurses’ experience in working with sex offenders-a hermeneutic phenomenological study. United Kingdom: University of Aberdeen.

- Azeem, M. W., Aujla, A., Rammerth, M., Binsfeld, G., & Jones, R. B. (2011). Effectiveness of six core strategies based on trauma-informed care in reducing seclusions and restraints at a child and adolescent psychiatric hospital. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing: Official Publication of the Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nurses, Inc, 24(1), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00262.x

- Baker, C. N., Brown, S. M., Wilcox, P., Verlenden, J. M., Black, C. L., & Grant, B. J. E. (2018). The implementation and effect of trauma-informed care within residential youth services in rural Canada: A mixed methods case study. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 10(6), 666–674. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000327

- Bianchini, V., Paoletti, G., Ortenzi, R., Lagrotteria, B., Roncone, R., Cofini, V., & Nicolò, G. (2022). The prevalence of PTSD in a forensic psychiatric setting: The impact of traumatic lifetime experiences. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 843730. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.843730

- Blanch, A., Filson, B., Penney, D., & Cave, C. (2012). Engaging women in trauma-informed peer support: A guidebook. National Center for Trauma-Informed Care.

- Blau, G., Tatum, D. S., & Ward Goldberg, C. (2013). Exploring correlates of burnout dimensions in a sample of psychiatric rehabilitation practitioners: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 36(3), 166–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000007

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage Publications.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Brockie, T. N., Dana-Sacco, G., Wallen, G. R., Wilcox, H. C., & Campbell, J. C. (2015). The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to PTSD, depression, poly-drug use and suicide attempt in reservation-based native American adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55, 411–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-015-9721-3

- Buetow, S. (2010). Thematic analysis and its reconceptualization as ‘saliency analysis’. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 15(2), 123–125. https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2009.009081

- Chouliara, Z., Hutchison, C., & Karatzias, T. (2009). Vicarious traumatisation in practitioners who work with adult survivors of sexual violence and child sexual abuse: Literature review and directions for future research. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 9(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140802656479

- Copperman, J., & Knowles, K. (2006). Developing women only and gender sensitive practices in inpatient wards—Current issues and challenges. The Journal of Adult Protection, 8(2), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/14668203200600010

- Covington, S. (2022). Creating a trauma‐informed justice system for women. In The Wiley handbook on what works with girls and women in conflict with the law: A critical review of theory, practice, and policy (pp. 172–184).

- Edwards, V. J., Holden, G. W., Felitti, V. J., & Anda, R. F. (2003). Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: Results from the adverse childhood experiences study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(8), 1453–1460. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1453

- Elliott, D. E., Bjelajac, P., Fallot, R. D., Markoff, L. S., & Reed, B. G. (2005). Trauma-informed or trauma-denied: Principles and implementation of trauma-informed services for women. Journal of Community Psychology, 33(4), 461–477. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20063

- Farro, S. A., Clark, C., & Hopkins Eyles, C. (2011). Assessing trauma-informed care readiness in behavioral health: An organizational case study. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 7(4), 228–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/15504263.2011.620429

- Folk, J. B., Kemp, K., Yurasek, A., Barr-Walker, J., & Tolou-Shams, M. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences among justice-involved youth: Data-driven recommendations for action using the sequential intercept model. The American Psychologist, 76(2), 268–283. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000769

- Frost, L., & Scott, H. (2022). What is known about the secondary traumatization of staff working with offending populations? A review of the literature. Traumatology, 28(1), 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000268

- Gatz, M., Brounstein, P., & Noether, C. (2007). Findings from a national evaluation of services to improve outcomes for women with co-occurring disorders and a history of trauma. Journal of Community Psychology, 35(7), 819–822. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20183

- Goldstein, E., Murray-García, J., Sciolla, A. F., & Topitzes, J. (2018). Medical students’ perspectives on trauma-informed care training. The Permanente Journal, 22(1), 17–126. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/17-126

- Han, H.-R., Miller, H. N., Nkimbeng, M., Budhathoki, C., Mikhael, T., Rivers, E., Gray, J., Trimble, K., Chow, S., & Wilson, P. (2021). Trauma informed interventions: A systematic review. PLoS One, 16(6), e0252747. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747

- Harris, M., & Fallot, R. D. (2001). Envisioning a trauma-informed service system: A vital paradigm shift. New Directions for Mental Health Services, 89(89), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.23320018903

- Hummer, V., Dollard, N., Robst, J., & Armstrong, M. (2010). Innovations in implementation of trauma-informed care practices in youth residential treatment: A curriculum for organizational change. Child Welfare, 89(2), 79–95. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45400455

- Isobel, S., & Thomas, M. (2022). Vicarious trauma and nursing: An integrative review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 31(2), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12953

- Jacobowitz, W., Moran, C., Best, C., & Mensah, L. (2015). Post-traumatic stress, trauma-informed care, and compassion fatigue in psychiatric hospital staff: A correlational study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36(11), 890–899. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2015.1055020

- Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., Pitcairn, J., Thomson, L., Mahoney, A., & Hyland, P. (2019). Childhood adversity and psychosis in detained inpatients from medium to high secured units: Results from the Scottish census survey. Child Abuse & Neglect, 96, 104094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104094

- Knight, C. (2015). Trauma-informed social work practice: Practice considerations and challenges. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43, 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-014-0481-6

- Lemelson, R., Kirmayer, L. J., & Barad, M. (2007). Trauma in context: Integrating biological, clinical, and cultural perspectives. In Understanding trauma: Integrating biological, clinical, and cultural perspectives (pp. 451–474). Cambridge University Press.

- Maguire, D., & Taylor, J. (2019). A systematic review on implementing education and training on trauma-informed care to nurses in forensic mental health settings. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 15(4), 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1097/JFN.0000000000000262

- Mancke, F., Herpertz, S. C., & Bertsch, K. (2018). Correlates of aggression in personality disorders: An update. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(8), 53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-018-0929-4

- Markham, S. (2022). Totalitarian approaches to risk and the banality of harm in secure and forensic psychiatric settings in England and Wales. Ethics, Medicine and Public Health, 23, 100776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemep.2022.100776

- McKay, M. T., Cannon, M., Chambers, D., Conroy, R. M., Coughlan, H., Dodd, P., Healy, C., O'Donnell, L., & Clarke, M. C. (2021). Childhood trauma and adult mental disorder: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of Longitudinal Cohort Studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 143(3), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13268

- Miller, N. A., & Najavits, L. M. (2012). Creating trauma-informed correctional care: A balance of goals and environment. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3(1), 17246. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.17246

- Morrow, K. J., Gustavson, A. M., & Jones, J. (2016). Speaking up behaviours (safety voices) of Healthcare Workers: A metasynthesis of qualitative research studies. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 64, 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.09.014

- Moskowitz, S. (2011). Primary maternal preoccupation disrupted by trauma and loss: Early years of the project. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 10(2-3), 229–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2011.600117

- Muskett, C. (2014). Trauma-informed care in inpatient mental health settings: A review of the literature. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 23(1), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12012

- NVivo. NVivo. (2021). Qualitative data analysis software. www.qsrinternational.com. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Oates, J., Topping, A., Ezhova, I., Wadey, E., & Marie Rafferty, A. (2020). An integrative review of nursing staff experiences in high secure forensic mental health settings: Implications for recruitment and retention strategies. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(11), 2897–2908. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14521

- O'Dwyer, C., Tarzia, L., Fernbacher, S., & Hegarty, K. (2021). Health professionals’ experiences of providing trauma-informed care in acute psychiatric inpatient settings: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 22(5), 1057–1067. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838020903064

- Patel, A. R., & Hall, B. J. (2021). Beyond the DSM-5 diagnoses: A cross-cultural approach to assessing trauma reactions. Focus, 19(2), 197–203. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20200049

- Ranu, J., Kalebic, N., Melendez-Torres, G. J., & Taylor, P. J. (2022). Association between adverse childhood experiences and a combination of psychosis and violence among adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 24(5), 2997–3013. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380221122818

- Reddy, L. F., & Spaulding, W. D. (2010). Understanding adverse experiences in the psychiatric institution: The importance of child abuse histories in iatrogenic trauma. Psychological Services, 7(4), 242–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020316

- Sareen, J., Henriksen, C. A., Bolton, S.-L., Afifi, T. O., Stein, M. B., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2012). Adverse childhood experiences in relation to mood and anxiety disorders in a population-based sample of active military personnel. Psychological Medicine, 43(1), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/s003329171200102x

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioralbehavioural health services: Treatment improvement protocol (TIP) series. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207201/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK207201.pdf

- Sweeney, A., Filson, B., Kennedy, A., Collinson, L., & Gillard, S. (2018). A paradigm shift: Relationships in trauma-informed mental health services. BJPsych Advances, 24(5), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2018.29

- Terr, L. C. (1991). Childhood traumas: An outline and overview. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1176/foc.1.3.322

- Trotta, A., Murray, R. M., & Fisher, H. L. (2015). The impact of childhood adversity on the persistence of psychotic symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 45(12), 2481–2498. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715000574

- Truesdale, M., Brown, M., Taggart, L., Bradley, A., Paterson, D., Sirisena, C., Walley, R., & Karatzias, T. (2019). Trauma‐informed care: A qualitative study exploring the views and experiences of professionals in specialist health services for adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities: JARID, 32(6), 1437–1445. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12634

- Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York, 3.

- Vaswani, N., & Paul, S. (2019). ‘It’s knowing the right things to say and do’: Challenges and opportunities for trauma‐informed practice in the prison context. The Howard Journal of Crime and Justice, 58(4), 513–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/hojo.12344

- Wooldredge, J. (2020). Prison culture, management, and in-prison violence. Annual Review of Criminology, 3(1), 165–188. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-011419-041359