The complexity of adventure tourism and its related fields

This issue of the Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism presents six research articles that deal with various aspects of adventure tourism. Adventure tourism is both a blurred concept and a multifaceted field where new activities appear unceasingly. This complexity led Rantala, Rokenes, and Valkonen (Citation2016) to argue that adventure tourism is more like a category than a concept.

One may distinguish between adventure tourism as activities and as modes of experience. In an attempt to depict adventure experience modes in tourism, Jacobsen (Citation2001) refers to Simmel (Citation1971), who argued that an adventure has a much more sharply delineated beginning and end than have other forms of experiences. The most general form of adventure, according to Simmel, “is its dropping out of the continuity of life” (Simmel, Citation1971, p. 187). Simmel’s supposition thus underscores the common binary division between everyday life as the ordinary and tourism as the extraordinary (Urry, Citation1990).

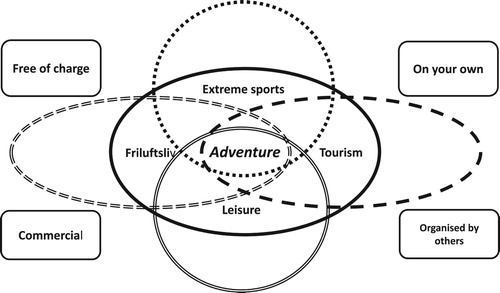

Most of what has been termed adventure tourism in present-day publications is located in an intersection of outdoor recreation (friluftsliv), (extreme) sports, and (serious) leisure, indicated in . In particular, the articles in this issue represent sport tourism; active participation in some outdoor activities (e.g. Beedie, Citation2003; Cloutier, Citation2003; Gammon & Robinson, Citation1997; Garms, Fredman, & Mose, Citation2017). However, also tourism undergoes changes. One trend is the “performance turn” (Ek, Larsen, Hornskov, & Mansfeldt, Citation2008), in which consumption by doing gradually is replacing or adding to the “consumption” of “undisturbed natural beauty” by a romantic gaze (Urry, Citation1990). Search for unique experiences through activities in the nature seems to boosts adventure travel segments while also contributing to growth in international leisure travel (Lee, Tseng, & Jan, Citation2015). Moreover, this same trend may include a desire to design one’s own agenda to attain the sought experiences (Ek et al., Citation2008). The latter change may lead to visitors that are more demanding and an increase in self-organised activities. In this issue, such changes are depicted in Rantala et al.’s (2018) article.

Figure 1. Adventure tourism as an intersection between tourism, serious leisure, extreme sports, and friluftsliv, and related to the contextual dimensions of commercialisation and remoteness.

Adventure tourism as activities appear as more or less “soft” or “hard” (Beard, Swarbrooke, Leckie, & Pomfret, Citation2012), differentiated by levels of potential risks, skills and exertion. “Soft” adventure are activities suitable for almost everyone, including families with kids. One example is glacier walks commodified for tourists to avoid accidents in an otherwise extremely dangerous context (Furunes & Mykletun, Citation2012). In turn, “hard” adventures ask for a certain physical and moral courage, as well as skills and competences, because such tours imply higher levels of potential risks, and often overlaps with extreme sports activities (). (Brymer & Gray, Citation2009, p. 136) define extreme sport as “outdoor leisure activities where the most likely outcome of a mismanaged mistake or accident is death” In this issue, Berbeka’s (2018) article describes activities that qualifies as extreme sports, while “hard” and “soft” adventures are an important aspect of Rantala et al.’s (2018) contribution in this issue.

Adventure tourism that overlaps with (extreme) sports call for specialised competence, often available by attending training programmes, which in turn requires the participant to invest time, effort, and money. This may be conceived as serious leisure (), a “systematic pursuit of an amateur, hobbyist, or volunteer activity that is sufficiently substantial and interesting for the participant to find a career there in the acquisition and expression of its special skills and knowledge” (Stebbins, Citation1992, p. 3). Ski tourism as skilled serious leisure (cf. Jacobsen, Denstadli, & Rideng, Citation2009) is evident in the articles of Berbeka (2018), and of Demiroglu, Dannevig, and Aall (2018) in this issue. However, as illustrated in the article by Rantala et al. (2018) in this issue, adventure tourist guides may have to change their ways of working because an increasing number of their tour participants lacks competence for the planned activities. This probably reflects that an increasing number of participants approach adventure activities as a more casual leisure undertaking, characterised as an “immediately, intrinsically rewarding, relatively short-lived pleasurable activity requiring little or no special training to enjoy it” (Stebbins, Citation1997, p. 18).

Moreover, the Nordic traditions and practices of friluftsliv () overlap in part the field of adventure tourism, in particular the concept of slow adventure. Varley and Semple (Citation2015) defines slow adventures as “explorations of and reconnections with this ground: feeling, sensing and investing in place, community, belonging, sociality, and tradition over time and in nature”. The “ground” refers here to a lost contact with the past due to an accelerated pace of development, leading to a sense of nostalgia. The term “slow” with the term “adventure” maybe appear “odd” in present-day as adventure is typically associated with speed, rush and thrill (Buckley, Citation2012; Cater, Citation2006), however, it fits well as a reaction to the dominant borderline experience logic of the commodified “fast adventures” (Varley & Semple, Citation2015). Friluftsliv is a blurred concept that may include sports, households’ food supply, recreation/holidaymaking, and various experiences of nature (Emmelin, Fredman, Sandell, Jensen, & Eriksson, Citation2005; Tordsson, Citation2005). However, friluftsliv, in contrast to “fast adventure”, also refers to a philosophy and a lifestyle based on experiences of the freedom in our original home – the nature – and the spiritual connectedness with the landscape, creating involvement and engagement with nature (Gelter, Citation2000). It may be conceived of as overskuddsliv i naturen, a self-expression in nature with or without survival activities to cover basic needs (food, clothing, etc.). Friluftsliv is in this context defined as experiences of and interactions with eco-systems, and togetherness and quality time with fellow humans surrounded by nature. The participants undertake activities with simple tools and equipment, and few technical means of transport. The equipment that is used is not supposed to take human engagement out of the experience but to enhance the experience through the opportunity to be closer to nature. Guidance enhances the novice participants’ experiences (Faarlund, Citation2003; Mathisen, Citation2017), which may become richer with increased distances from the urban ways of life. “Friluftsliv could be a trans-modern way to reconnect with nature and provide basic experiences of interconnectedness with a more-than-human world” (Gelter, Citation2000, p. 1). Thus, Beery (Citation2013) report associations between being an active participant in friluftsliv and reporting higher levels of stronger environmental connectedness. However, the association did not apply for the young age group, and Beery interpret this as an effect of urbanised lifestyle in contrast to being socialised to friluftsliv through activities in nature. According Brymer and Gray (Citation2009), this close connectedness to nature is frequently found among extreme sport athletes. Instead of struggling or fighting with nature, extreme sports is more like dancing with nature as a challenging partner. In this issue, the Andersen and Rolland's article (2018) deals with friluftsliv and training of guides for such activities, and they emphasise the value of having guides increasing the visitors’ insight (Walle, Citation1997) in their tutoring.

Furthermore, operators may run adventure tourism for commercial purposes and market them as “experience” or “activity” products (Keskitalo & Schilar, Citation2017). According to Varley and Semple (Citation2015), these are mainly “fast adventures” where they promise exciting experiences and adrenaline kicks. Alternatively, the tourists may go on their own, being self-managed, which fits nicely into the “slow adventure” philosophy. However, the self-managed tour may also be exciting and create a rush feeling, and a guided tour may serve as “slow adventure”. The adventure activity may take place anywhere in natural areas from being close to the urban surroundings to remote and thinly populated areas where the participants are on their own. Again, these variabilities underscore the complexity of the adventure tourism concept. In the present issue, all articles deal with commercialised adventure activities, except the article by Andersen and Rolland who researched training guides for friluftsliv. The article by Large and Schilar (2018) combines data from both a commercial and a non-commercial setting and discusses the similarities between them. Berbeka’s (2018); Large and Schilar’s (2018); and Andersen and Rolland’s (2018) articles report research conducted in remote areas, while the others have their data more related to more or less populated areas.

Defining adventure tourism

Having discussed how adventure tourism relates to its overlapping fields, we will now turn to defining the category of adventure tourism itself. Taken from the Adventure Travel Trade Association (ATTA), adventure tourism is seen as “a trip (travelling outside a person’s normal environment for more than 24 h and not more than one consecutive year) that includes at least two of the following three elements: physical activity, natural environment, and cultural immersion” (Adventure tourism development index, Citation2016). The report lists 34 different types of activities, ranging from demanding out-door activities in wild nature to visiting friends and family, visiting a historical site, and participating in a volunteer tourism programme. Based on this definition it claims that adventure tourism is growing faster than the growth in tourism in general and faster than cruise tourism, another fast expanding business. According to its statistics, the ten most popular adventure tourism countries are Iceland, Germany, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, Canada, Australia, Finland, Austria, and Denmark. ATTA assumes that the growth will continue, especially because of increased demands for adventures from the Asian population. However, political changes will cause some shifts in the flow of tourists, and decline in democracies around the world may increase the risk of unfair treatment and lack of home country support in certain cases of trouble (Citation20 Adventure Travel Trends to Watch in, Citation2018).

The above documented growth of the business and ranking of countries reflects ATTA’s measurement methods as well as its wide definition of adventure tourism. By including cultural immersion in the definition, the field is wider than when applying a traditional definition. No doubt the cultural features of a place will somehow influence the performance and experience of adventure tourism activities. For instance, cultural contexts are clearly implicit in the contributions of Sigurðardóttir and of Andersen and Rolland in this issue. However, one may ask if the combination of activity and culture alone qualifies as adventure tourism, which the ATTA definition implies. Sung, Morrison, and O’Leary (Citation1997) propose a narrower definition with emphasis on active participation in nature. To them, adventure tourism is “A trip or travel with the specific purpose of activity participation to explore a new experience, often involving perceived risk or controlled danger associated with personal challenges, in a natural environment or exotic outdoor setting”. They further underline that concepts such as activity, motivation, risk, performance, experience, and environment applies when defining adventure travel. Activity close to nature is also underlined by Addison (Citation1999), while Carter (Citation2000) argues that adventure is fundamentally about active recreation participation and it demands new metaphors based more on “being, doing, touching and seeing” rather than just seeing. Interestingly, ATTA concludes its trend study by stating that adventure tourism providers should “ … maintain focus on delivering the experiences with heart, which truly connect travellers to nature and people in the destinations they visit” (Citation20 Adventure Travel Trends to Watch in, Citation2018, p. 40), thus reminding us that nature and people should be in the centre of the adventure tourism. Activities in nature and relationship to the environment are the empirical setting for all six articles included in this issue.

Beard et al. (Citation2012, p. 9) argue that the core of adventure includes several important and inter-related components: “uncertain outcomes, danger and risk, challenge, anticipated rewards, novelty, stimulation and excitement, escapism and separation, exploration and discovery, absorption and focus as well as contrasting emotions”. Carpenter and Priest (Citation1989) underscored uncertainty as a specific feature of the adventure experience paradigm, underlining its central position within adventure activities. Any of these elements separately will not be an adventure, while adventure is highly likely if all elements present. The components match with “fast adventure” (Varley & Semple, Citation2015). Although activity is required, Beard et al. (Citation2012) also argue that an adventure as such is mainly a “state of mind” and “approach” of the participant. This may be considered as one cornerstone of understanding the increasing popularity of adventure tourism – adventure is about engaging, exciting, and testing participant abilities. It is pushing personal boundaries, which is a part of discovering one’s true self. After following adventure activities for a long time, Buckley (Citation2012) concludes that the experience of “rush feeling” is the ultimate benefit of an adventure tourist. The concept of rush refers to “the simultaneous experience of thrill and flow associated with the successful performance of an adventure activity at a high level of skill” (Buckley, Citation2012, p. 963). Here the concept of “thrill” is understood as “a purely adrenalin based physiological response”, and the concept of “flow” applies to “any form of skilled activity where the exponent’s mental focus coincides fully with their physical practice, so that they are ‘intensely absorbed’” (Buckley, Citation2012, p. 963). In this issue, the article by Large and Schilar (2018) mainly focuses on adventure as a state of mind, and their research includes the experience of the subjects involved. Perceptions and experiences are also a central part of Andersen and Rolland’s contribution (2018), and Berbeka’s (2018) article in this issue deals with tourists’ experiences, motives and values.

Drivers for adventure tourism

Motivation has been a central topic in the adventure tourism research since the 1980ies. Rantala et al. (Citation2016) reviewed adventure tourism literature and found 640 articles especially relevant to the topic. They report that the most frequently studied themes were novelty, emotion and thrill, and that recent research has focused on the idea of an inner journey as a central perspective. Cheng, Edwards, Darcy, and Redfern (Citation2016) reviewed adventure tourism literature and found 114 publications based on five different theoretical frameworks, including the risk paradigm, the insight paradigm, the notion of flow, the notion of play, and finally the feeling of rush, while tourists’ experience were one of three major research areas.

The classical discourse has been between the claims of Ewert (Citation1989) that the concept of risk-taking is the essential motivation for adventure travel activities, that performance in adventure travel is associated with skill level (Ewert, Citation1987; Ewert & Hollenhorst, Citation1994) and linked to the accomplishment of self-imposed and more abstract personal goals (Ewert, Citation1989). Contrary to this, Walle (Citation1997) argues that the search for insight is a leading motivation for participation in outdoor adventures and that personal self-actualization through outdoor adventures does not layin risk and risk-taking, but is an outcome of getting an insight; hence, an adventurer gets fulfilment from the process of getting such insight. However, hard evidence supports the risk arguments: Comparing register data across Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Finland, Slovenia, Belgium, Luxembourg, and The Netherlands; Weber et al. (Citation2018) show that extreme sports creates fatal or serious injuries. Airborne sports had the highest injury severity, followed by climbing, skating, and contact sports. Especially high falls resulted in a significant rate of spinal injuries in airborne activities and in climbing accidents. A comprehensive overview of accidents and risks in adventure and extreme sports edited by Mei-Dan and Carmont (Citation2013) mainly support these findings.

Other research has concluded differently. Thus, Mu and Nepal (Citation2016), p. 501) suggest that:

“ … when competence is high and the risk is low, the activity moves toward a condition of exploration and experimentation. Participants generally experience emotional arousal positively. But when risk is viewed as much higher than competence, people feel anxiety and fear turning positive arousal to a negative experience”.

Commercial adventure tourism contains a paradoxical relationship between risk and safety. The tourism industry in general aims at reducing risk perceptions among tourists to increase sales. However, adventure tourism seems to work the opposite way, as risk and uncertainty of outcomes are core components of the adventure that tourists are actively seeking (Dickson & Dolnicar, Citation2004). It creates a certain paradox for tour operators who should deliver two contradictory perceptions: risk and safety. Fletcher (Citation2010) refers to three ways for overcoming this paradox. First, adventure tourism succeeds by creating the illusion of risk, while hiding “real” security from tourists. Second, tour operators hide the “real” risk and clients falsely believe that their adventure is without any risk. Third, adventure tourism rests on a public secrecy, implying that risk and safety exist simultaneously, and tour providers and customers do not acknowledge this contradictory impression related to the concept of adventure.

Stranger (Citation1999) offers a new explanation, suggesting that risk-taking and aesthetics can correlate, for example, in surfing activities, and may be an important motivation for its participants. Thus, “aestheticization facilitates risk-taking in the pursuit of an ecstatic, transcendent experience” and, “the surfing aesthetic involves a postmodern incarnation of the sublime that distorts rational risk assessment” (Stranger, Citation1999, p. 265). In addition, wilderness can provide feeling of aesthetical satisfaction (Ewert & Hollenhorst, Citation1990), and wilderness can imply risk (Mykletun & Mazza, Citation2016). Reviewing research on motivation for adventure tourism, Buckley (Citation2012) found 50 publications about this subject, which identified at least 14 different categories of motivation for adventure activities. Buckley summarised these motivations into three main groups: 1) performance of activity (internal); 2) place in nature (internal/external); and 3) social position (external). In this issue, motivation as a theme appears in the articles of Andersen and Rolland (2018); Demiroglu et al. (2018); Berbeka (2018); and finally Rantala et al. (2018) Risk and safety issues are present in the articles in this issue. Risk is mentioned in Sigurðardóttir’s (2018) article, Demiroglu et al (2018); and a very important concept in the contributions of Berbeka (2018); Large and Schilar (2018); and of Rantala et al (2018). The concept of safety is central in the article of Andersen and Rolland (2018), important in Bereka’s (2018) contribution, and mentioned in the work of Demiroglu et al (2018).

The six empirical contributions in this volume

The contributions within this volume are within the traditional conception of adventure tourism and travel, as none of them focuses explicitly on cultural aspects. Thus, they fit into the definition of Sung, Morrison, and Leary (Citation1997). In the first paper, “Understanding the meanings and interpretations of adventure experiences: the perspectives of multiday hikers”, Joanna Large and Hannelene Schilar (2018) argues for a more critical academic understanding of adventure as a meaningful subjective experience bound up between the ordinary and the extraordinary. They argue that adventure is only meaningful when understood from the perspective of the individual experiencing it. Moreover, they also reflect on relationships between the ordinary and the extraordinary, and how the former is integrated in the latter and defines it during the adventure experience (see also Goolaup & Mossberg, Citation2017). They also question the relevance of the commercial and commodified versus non-commercial non-commodified adventure discourses. Their discussion and conclusions are based on 26 interviews with participants in commercial and non-commercial settings that may be referred to as more on the soft side of the adventure tourism or travel.

Combining interview data and survey studies results in the article “The softening of adventure tourism in Finnish Lapland”, Outi Rantala, Ville Hallikainen, Heli Ilola, and Seija Tuulentie (2018) demonstrate a “softening” of adventure tourism – a change in Finish adventure tourism practices. The context studied is commercial adventure tourism in Finish Lapland. The survey respondents were adventure tourists and interviewees were commercial tourism providers. Such “softening” also includes a demand for more differentiation of activities due to inadequate competencies and skills among the tourists, which in turn raised new demands on the providers’ competencies and flexibility. The wider range of competencies includes detection of participants’ skills and consequent differentiation of activities before and during the activities. On top of the hard adventure skills, tourists also expect more of the soft skills from their guides, including interpretation of local nature and culture, ability to encourage reflection, and talent for creating good social atmosphere. These change processes extend beyond the guides and includes more or all providers and staff at the destination. Consequently, according to the authors, the “soft” end of this artic adventure tourism product might blurred and possibly impair the magic of the artic adventures. On the other hand, such “softening” may be conceived of as a democratisation of the commercial adventure tourism.

In the article “Friluftsliv: a way of enhancing experiences and learning in adventure tourism?” the authors Sigmund Andersen and Carsten Gade Rolland (2018) defend the role of the principles of friluftsliv in adventure experience production. They researched the methods used by nature guides when they escort tourists into an adventurous experiencescape and it represents a unique integration of principles of friluftsliv with some aspects of tourism theories and practices. From the field of friluftsliv, the nature guide in part applies the pedagogic methods of experiential learning and the role of a “friluftsliv conveyer”, while from the field of tourism, the nature guide acts in line with the methods and theories of experience production, interpretation and transformative guiding. The role of the nature guide has developed from being a safe pathfinder to a diverse and complicated set of roles such as teacher, environmental ambassador, psychologist, and entertainer. In addition, the professional nature guide displays a broad understanding of how to enhance the guests’ experiences into learning and a closer relationship with nature, thus adding a higher quality and value to their commercial product. Key components in their work were safety and hard skill learning, facilitation of a sense of social belonging, experience and learning, and nature awareness. The study is informed by data from interviews with four groups of nature guides after ski expeditions of six days with 4–5 guests on the Svalbard glaciers.

Ingibjörg Sigurðardóttir (2018) provides an important and still somewhat rare dimension in adventure tourism research in the article “Wellness and equestrian tourism - New kind of an adventure?”. This contribution aims at revealing to what extent operators in equestrian tourism in Iceland focus their product development and marketing towards adventure or health and whether a combination of slow adventure, wellness, and outdoor recreation is a realistic option for innovation within equestrian tourism. The findings rest on content analysis of webpages and open-ended interviews with equestrian tourism operators. The author concludes that the adventure concept is important in equestrian tourism in Iceland and mainly with a focus on hazardous adventures. The health and well-being concepts are not frequently mentioned, but operators are aware of existing resources that could be used for innovation of equestrian tourism businesses towards slow adventures and wellness. The author concludes that opportunities for combining equestrian tourism, slow adventures, wellness, and outdoor activities in these products are present. However, use of these opportunities requires a re-thinking of the connectivity of the wellness and adventure tourism concepts and support of various kinds would facilitate such innovations.

Snow business and snow activities are natural adventure tourism activities in a Nordic context. Two of the articles address such issues. Jadwiga Berbeka’s (2018) article, “The value of remote arctic destinations for backcountry skiers”, point to the fact that expeditions to remote areas of the Arctic for backcountry skiing appear as an unexplored phenomenon. A survey to participants of expeditions to East Greenland and the West Fjords in Iceland (purposive sampling) and in-depth interviews with operators informed the empirical part of the study. The author identifies three groups of benefits or values as perceived by the participants: the beauty, wilderness, and remoteness of the area; ski touring with focus on unspoiled powder and independent trails; and relationships to other participants. Push factors such as challenge and internal locus of control were important motivational dimensions. The participants are willing to pay a 300€ per day on average for this type of expedition. Good guides that are professional, empathic, and oriented towards the experiences of their clients are key elements in the success of a tour operator’s business. The group participants should be as equal as possible regarding skills and motivations, making the ability to select participants for a group and flexibility additional skill requirements to the guides. Financial status and competence in relation to mountains and skiing are crucial determinants of participation, and the market segment is strongly involved in adventure ski tourism.

O. Cenk Demiroglu, Halvor Dannevig, and Carlo Aall (2018) contribute with yet another dimension of adventure tourism and travel: that of climate change. While climate change will interact with adventure tourism in many ways, the article “Climate change acknowledgement and responses of summer (glacier) ski visitors in Norway” focus on the interaction of climate change and the highly weather-dependent ski tourism business. Climate changes will threaten the sustainability of skiing areas, which has created some research attention towards impact and adaptation studies regarding ski areas, resorts, and destinations, whereas research on the demand side of the issue is relatively limited. This article addresses the relationship of climate change to summer skiing, which is one niche segment of ski tourism. To what extent are summer skiing tourists aware of this threat to their favourite skiing activity, and how do they perceive the present and expected future changes in the skiing conditions? Summer skiing in Norway is possible at three downhill skiing centres providing nice slopes on snow on the surface of glaciers, namely at Vesljuvbreen, Tystigbreen, and Botnabrea. The operational seasons vary from May to July and as late as October. A comprehensive survey to 224 subjects at these centres revealed a high climate change awareness but limited climate friendliness. A strong emphasis on the immediate climate impacts on summer skiing creates a tendency towards spatial and temporal ski activity substitution within Norway, especially among the older skiers. Glaciers are among the most warming exposed systems, and consequently, summer skiers in Norway directly witnesses the impacts of climate change, which in return contributes to their literacy and sensitivity on the issue. The skiers did not favour artificially produced snow, which is an advantage for the energy consumption of these skiing facilities. In spite of the ongoing changes, the skiers tended to be loyal to their favourite resorts instead of travelling to remote summer skiing areas.

Final comments

The cases included in this volume present adventure tourism research from the northern hemisphere, mainly the Nordic countries including Greenland. They are all within the traditional definition of adventure tourism as stated by Sung et al (1987), and they apply mainly theoretical frameworks as discussed above. Both qualitative and quantitative data are applied, and some of the articles combines these strategies to optimise their insight in the study area. The contexts of the studies vary greatly as do the themes they focus on. Hence, it is difficult to draw general conclusions about the learning outcomes of these articles. Each article has unique contributions and together they enlighten some of the challenges, successes and rich varieties of resources of adventure tourism in the Nordic countries including Greenland.

Interestingly in this context, the English mountaineer Cecil Slingsby published early in the twentieth century “Norway, the Northern Playground: Sketches of climbing and mountain exploration in Norway between 1872 and 1903” (Citation1904). On this fabulous playground across Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden and Finland, the right of free non-motorised access to uncultivated land opens up for extensive use of the nature for adventure travel and tourism purposes. Together, these vast areas offer unique varieties in landscapes. They are used for various types of adventure tourism, and researchers should respond by exploring the inner journeys, the experiences and their relation to nature, the possible interaction with locals, how operators and others treat them, and how adventurers create their own journeys. In particular, there is a need for a better understanding of the relationship between adventure tourism and benefits for health and wellbeing that is gained through involvement with nature. Along similar lines, the caring for the nature and the feeling of being at one with the natural world or connected through a life enhancing energy, call for researchers’ attention. Complementary to this, research on operators’ challenges and successes, ways of providing the good excursions should be researched, and in particular, how the operators and the destinations adapt to customers’ demands on individualised experiences and the “softening” of the adventures. Yet another challenge come with “over-tourism” in some uncultivated Nordic landscapes through increased use of privately owned land for commercial purposes other than the land owners’. “The Northern playground” is thus an appropriate place for research on a multitude of intriguing themes that remain to be explored.

References

- 20 Adventure Travel Trends to Watch in. (2018). Retrieved from https://cdn1.adventuretravel.biz/research/2018-Travel-Trends.pdf

- Addison, G. (1999). Adventure tourism and ecotourism. In J. C. Miles & S. Priest (Eds.), Adventure programming (2nd ed. pp. 415–430). Regent Court: Venture Publishing.

- Adventure tourism development index. (2016). Retrieved from https://cdn.adventuretravel.biz/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/ATDI16-web.pdf

- Beard, C., Swarbrooke, J., Leckie, S., & Pomfret, G. (2012). Adventure tourism: The new frontier. UK: Routledge.

- Beedie, P. (2003). Adventure tourism. In S. Hudson (Ed.), Sport and adventure tourism (pp. 203–239). New York and London: Routledge.

- Beery, T. H. (2013). Nordic in nature: Friluftsliv and environmental connectedness. Environmental Education Research, 2013, 19(1), 94–117. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2012.688799

- Brymer, E., & Gray, T. (2009). Dancing with nature: Rhythm and harmony in extreme sport participation. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 9(2), 135–149. doi: 10.1080/14729670903116912

- Buckley, R. (2012). Rush as a key motivation in skilled adventure tourism: Resolving the risk recreation paradox. Tourism Management, 33, 961–970. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2011.10.002

- Carpenter, G., & Priest, S. (1989). The adventure experience paradigm and non-outdoor leisure pursuits. Leisure Studies, 8, 65–75. doi: 10.1080/02614368900390061

- Carter, C. (2000). Can I play too? Inclusion and exclusion in adventure tourism. The North West Geographer, 3, 49–59.

- Cater, C. I. (2006). Playing with risk? Participant perceptions of risk and management implications in adventure tourism. Tourism Management, 27, 317–325. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2004.10.005

- Cheng, M., Edwards, D., Darcy, S., & Redfern, K. (2016). A thri-method approach to a review of adventure tourism literature: Bibliometric analysis, content analysis, and a qualitative systematic literature review. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 1–24. Published online 2016. Downloaded 08.08.2018. doi: 10.1177/1096348016640588

- Cloutier, R. (2003). The business of adventure tourism. In S. Hudson (Ed.), Sport and adventure tourism (pp. 241–272). New York and London: Routledge.

- Dickson, T., & Dolnicar, S. (2004). No risk, no fun - the role of perceived risk in adventure tourism. CD Proceedings of the 13th International Research Conference of the Council of Australian University Tourism and Hospitality Education (CAUTHE 2004). RIS ID 10187. Retrieved from https://ro.uow.edu.au/commpapers/246/

- Ek, R., Larsen, J., Hornskov, S. B., & Mansfeldt, O. K. (2008). A dynamic framework of tourist experiences: Space-time and performances in the experience economy. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 8(2), 122–140. doi: 10.1080/15022250802110091

- Emmelin, L., Fredman, P., Sandell, K., with Jensen, E. L., & Eriksson, L. (2005). Planering och förvaltning för friluftsliv: En forskningsöversikt (planning and management of outdoor recreation: A research overview). Stockholm: Naturvårdsverket.

- Ewert, A. (1987). Recreation in the outdoor setting: A focus on adventure-based recreational experiences. Leisure Information Quarterly, 14(1), 5–7.

- Ewert, A. (1989). Outdoor adventure pursuits: Foundation, models and theories. Columbus, OH: Publishing Horizons.

- Ewert, A., & Hollenhorst, S. (1990). Resource allocation: Inequities in wildland recreation. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 61(8), 32–36. doi: 10.1080/07303084.1990.10604598

- Ewert, A., & Hollenhorst, S. (1994). Individual and setting attributes of the adventure recreation experience. Leisure Sciences, 16, 177–191. doi: 10.1080/01490409409513229

- Faarlund, N. (2003). Friluftsliv: Hva – hvorfor – hvordan. Retrieved from www.naturliv.no/faarlund/hva20-20hvorfor20-2hvordan.pdf

- Fletcher, R. (2010). The emperor’s new adventure: Public secrecy and the paradox of adventure tourism. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 39(11), 6–33. doi: 10.1177/0891241609342179

- Furunes, T., & Mykletun, R. J. (2012). Frozen adventure at risk? A 7-year follow-up study of Norwegian glacier tourism. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 12(4), 324–348. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2012.748507

- Gammon, S., & Robinson, T. (1997). Sport and tourism: A conceptual framework. Journal of Sport Tourism, 4(3), 11–18. doi: 10.1080/10295399708718632

- Garms, M., Fredman, P., & Mose, I. (2017). Travel motives of German tourists in the scandinavian mountains: The case of fulufjället national park. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 17(3), 239–258. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2016.1176598

- Gelter, H. (2000). Friluftsliv: The scandinavian philosophy of outdoor life. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 5, 77–92. Retrieved from http://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/302/803

- Goolaup, S., & Mossberg, L. (2017). Exploring the concept of extraordinary related to food tourists’ nature-based experience. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 17(1), 27–43. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2016.1218150

- Gyimothy, S., & Mykletun, R. J. (2004). Play in adventure tourism: The case of Arctic trekking. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(4), 855–878. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2004.03.005

- Jacobsen, J. K. S. (2001). Nomadic tourism and fleeting place encounters: Exploring different aspects of sightseeing. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 1, 99–112. doi: 10.1080/150222501317244029

- Jacobsen, J. K. S., Denstadli, J. M., & Rideng, A. (2009). Skiers’ sense of snow: Tourist skills and winter holiday attribute preferences. Tourism Analysis, 13(5–6), 605–614. doi:10.3727/108354208788160478

- Keskitalo, E. C. H., & Schilar, H. (2017). Co-constructing “northern” tourism representations among tourism companies, DMOs and tourists. An example from jukkasjärvi, sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 17(4), 406–422. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2016.1230517

- Lee, T. H., Tseng, C. H., & Jan, F. H. (2015). Risk-taking attitude and behavior of adventure recreationists: A review. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality, 4(149), 1–3. doi: 10.4172/2167-0269.1000149

- Mathisen, L. (2017). Storytelling: A way for winter adventure guides to manage emotional labour. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 54, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2017.1411827

- Mei-Dan, O., & Carmont, M. R. (2013). Adventure and extreme sports injuries. London, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4471-4363-5

- Mu, Y., & Nepal, S. (2016). High mountain adventure tourism: Trekkers’ perceptions of risk and death in Mt. Everest region, Nepal, Asia pacific. Journal of Tourism Research, 21(5), 500–511. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2015.1062787

- Mykletun, R. J., & Mazza, L. (2016). Psychosocial benefits from participating in an adventure expedition race. Journal of Sport, Business and Management, 6(5), 542–564. doi: 10.1108/SBM-09-2016-0047

- Rantala, O., Rokenes, A., & Valkonen, J. (2016). Is adventure tourism a coherent concept? A review of research approaches on adventure tourism. Annals of Leisure Research. doi: 10.1080/11745398.2016.1250647

- Simmel, G. (1971). [1911]. The adventurer. In D. N. Levine (Ed.), On individuality and social forms (pp. 187–198). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Slingsby, W. C. (1904). Norway, the Northern playground: Sketches of climbing and mountain exploration in Norway between 1872 and 1903. Edinburgh, UK: D. Douglas.

- Stebbins, R. A. (1992). Amateurs, professionals, and serious leisure. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Stebbins, R. A. (1997). Casual leisure: A conceptual statement. Leisure Studies, 16(1), 17–25. doi: 10.1080/026143697375485

- Stranger, M. (1999). The aesthetics of risk: A study of surfing. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 34(3), 265–276. doi: 10.1177/101269099034003003

- Sung, H. H., Morrison, A. M., & O’Leary, J. T. (1997). Definition of adventure travel: Conceptual framework for empirical application from the providers’ perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 1(2), 47–67. Retrieved from https://www.hotel-online.com/Trends/AsiaPacificJournal/AdventureTravel.html doi: 10.1080/10941669708721975

- Sung, H. H., Morrison, A. M., & O’Leary, J. T. (1997). Definition of adventure travel: Conceptual framework for empirical application from the providers’ perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 1(2), 47–68. Retrieved from https://www.hotel-online.com/Trends/AsiaPacificJournal/AdventureTravel.html. doi: 10.1080/10941669708721975

- Tordsson, B. (2005). Hvad er friluftsliv godt for (what is the meaning of outdoor life). In S. Andkjær (Ed.), Friluftsliv under forandring (changing outdoor life) (pp. 11–31). Slagelse: Bavnebanke.

- Urry, J. (1990). The tourist gaze. London: Sage.

- Varley, P., & Semple, T. (2015). Nordic slow adventure: Explorations in time and nature. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 15(1–2), 73–90. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2015.1028142

- Walle, A. H. (1997). Pursuing risk or insight: Marketing adventures. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(2), 265–282. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(97)80001-1

- Weber, C. D., Horst, C., Nguyen, A. R., Lefering, R., Pape, H.-C., & Hildebrand, F. (2018). Evaluation of severe and fatal injuries in extreme and contact sports: An international multicenter analysis. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery, 138, 963–970. doi: 10.1007/s00402-018-2935-8