ABSTRACT

While there is a growing interest in immersive experiences and visitor immersion within the tourism industry, there is still a deficiency of empirical research focusing on how visitors become immersed. This study explores the subjective nature of the immersion process by focusing on the moderating role of individual responses and the influence of antecedent factors in the process. Empirical evidence for the purpose of this study was collected through a combination of field observations and group interviews with guests visiting an Escape Room in Norway. Six individual responses that appeared to moderate the individual visitors’ immersion process were identified in the study; including affective, behavioral, and cognitive responses. Findings further indicated that these responses were influenced by personal, external and social antecedents, as well as by the visitors’ own appraisal of the core features of the experience product. The findings presented in this article shed light on the individual nature of the immersion process and the factors that moderate the visitors’ progression towards a state of immersion.

Introduction

Experiences have been a key research topic among tourism scholars since the 1960s. This has resulted in the development of a variety of experience concepts that are frequently cited in the tourism literature. Examples include peak experiences (Maslow, Citation1964), extraordinary experiences (Arnould & Price, Citation1993) and flow (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1990). These are experience types that are highly regarded in the tourism industry, as they provide visitors with powerful experiences that have the potential to become lifelong memories (Arnould & Price, Citation1993). While several scholars have argued for the interconnectedness of these concepts (see for example Privette (Citation1983) and Schouten, McAlexander, and Koenig (Citation2007)), few studies have examined the individual components shared by these types of experience. According to Arnould and Price (Citation1993), what they have in common, in addition to being personally transformative and hedonistic, is that they involve some degree of immersion and a feeling of loss of self. A better understanding of immersion can therefore give us a deeper understanding of one of the core components of these coveted experience types. A more thorough understanding of immersion can also have important practical implications as immersion has been linked to emotional engagement (Brown & Cairns, Citation2004; Jennett et al., Citation2008), which is one of the key components of memorable experiences (Johnston & Clark, Citation2001; Kim, Citation2014). Memorable experiences can, in turn, be crucial to the long term profitability of tourism providers (Campos, Mendes, Do Valle, & Scott, Citation2016) as memorable experiences are known to have favorable effects on re-visitation intentions as well as positive word of mouth (Kim, Ritchie, & Tung, Citation2010; Slåtten, Krogh, & Connolley, Citation2011). Experience providers in the tourism industry can hence use immersion as a strategic tool to facilitate memorable experiences for their visitors. To be able to facilitate immersive experiences it is however fundamental to understand the immersion process – the process through which consumers become immersed. In this study, we are therefore going to focus on the immersion process in an effort to expand on the existing knowledge of the factors that influence it.

Literature review

What is immersion?

Experiences can be understood as a subjective, individual phenomenon resulting from a series of complex psychological processes within the individual (Larsen, Citation2007). Immersion is a part of the total visitor experience and is hence a subjective phenomenon experienced inside the mind of the individual. Within the tourism and consumer behavior literature, immersion is commonly understood as a fleeting psychological state in which the consumer becomes so involved in the present experience that they become completely engrossed in it, losing their awareness of time and their own self-consciousness (Hansen & Mossberg, Citation2013). Immersion has been defined as “the feeling of being fully absorbed, surrendered to, or consumed by an activity, to the point of forgetting one’s self and one’s surroundings” (Mainemelis, Citation2001, p. 557), and has been described as the deepest form of involvement (Brown & Cairns, Citation2004).

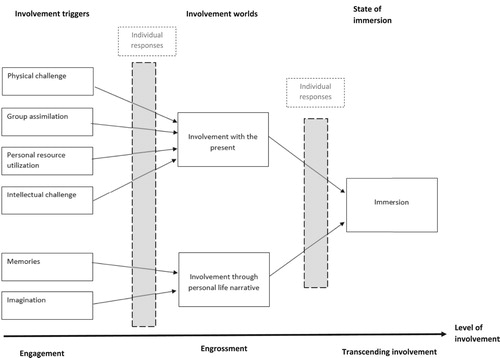

In the literature, several different types of immersion have been described, including challenge-based immersion (Ermi & Mäyrä, Citation2005), imaginative immersion (ibid.) and “immersion as being” (Hansen, Citation2014). Findings from Blumenthal and Jensen (Citation2019) however, indicate that rather than being different types of immersion, they represent different paths or “involvement worlds” leading to the same psychological state of immersion. This is also apparent through the way in which these different “types” of immersion is described. Challenge-based immersion is for example described as “the feeling of immersion that is at its most powerful when one is able to achieve a satisfying balance of challenges and abilities” (Ermi & Mäyrä, Citation2005, p. 7). Alluring more to how the consumer becomes immersed and the factors that can trigger immersion, rather than a certain type of immersion.

The nature of the immersion process

Only a limited number of studies focusing on the immersion process have been published to date and our understanding of the process is therefore limited. In the computer game and consumer behavior literature the process has been described as progressive and sequential (Brown & Cairns, Citation2004), or as either cyclical or immediate, depending on the consumer’s prior experience with the activity or context (Carù & Cova, Citation2005). Within the context of tourism however, the process has been found to be more dynamic, with visitors fluctuating in and out of different levels of involvement during the course of the experience (Blumenthal & Jensen, Citation2019; Hansen & Mossberg, Citation2013). Which could be an indication of contextual differences.

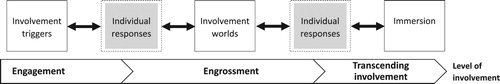

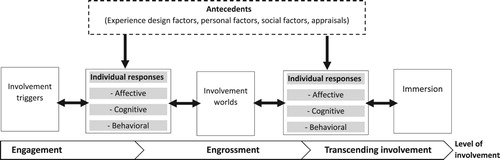

Several studies have identified involvement as the driving force behind the immersion process (Blumenthal & Jensen, Citation2019; Brown & Cairns, Citation2004; Hansen & Mossberg, Citation2013). Blumenthal and Jensen (Citation2019) suggest that the immersion process begins with the visitors’ initial involvement being triggered by “involvement triggers” during the “engagement” phase in the immersion process. These involvement triggers are factors, such as memories, group assimilation, and challenges (physical or intellectual), that have the ability to trigger internal responses within the visitors, leading them to a higher level of involvement. In the second phase of the immersion process, during the “engrossment” phase, the visitors’ attention become more focused towards one of the two identified involvement worlds (involvement with the present or involvement through personal life narrative), leading them further down the path towards a state of immersion (see ). Both the involvement triggers and the involvement worlds arise from the visitors’ interactions with the experiencescape, but their effect on visitor involvement seemed to be moderated by how the individual visitors respond to them. While the authors point to the important role of individual responses in the immersion process, their model seems to assume a simple stimuli – response correlation (Mehrabian & Russell, Citation1974). Where visitors are exposed to a stimulus and then have a response to that stimulus, without considering the different types of responses the visitors might have, and which factors beyond the given stimuli might influence the visitors’ responses. The aim of the present study is therefore to develop and extend Blumenthal and Jensen’s (Citation2019) model by applying it to a new experience context and (A) investigating the type of individual responses that influence the immersion process and (B) explore the antecedent factors that influence these responses.

Figure 1. Blumenthal and Jensen’s model of the immersion process (Blumenthal & Jensen, Citation2019, p. 168).

Methods

This study was designed as a single case study (Yin, Citation2003). This design was chosen, as case studies are considered particularly appropriate to the study of a phenomenon of which our understanding is limited and where current perspectives conflict with one another (Eisenhardt, Citation1989). Following the recommendations of Eisenhardt (Citation1989), the study set out with two broad research questions and employed a purposive case sampling strategy based on a set of pre-defined criteria (Creswell, Citation2013; Flyvbjerg, Citation2004). As the study was dependent on a case context that has the potential to facilitate immersive experiences. It was determined that the selected experience product should, in line with previous research on the facilitators of immersion, offer opportunities for active participation (Hansen & Mossberg, Citation2013) and be offered inside an experiencescape that could be perceived by visitors as safe, themed and enclaved (Carù & Cova, Citation2007). Additionally, the selected experience product should be offered within the context of a managed visitor attraction and offer contrasting conditions to the original case used by Blumenthal and Jensen (Citation2019).

Based on the above-mentioned criteria an escape room was selected as the case context for this study. An escape room is an experience product were visitors are locked inside a room and have to find a way to “escape” the room by solving a number of puzzles with the help of clues and hints hidden inside the room (Dilek & Dilek, Citation2018). The specific room chosen for this study was offered by Escape Reality Trondheim AS and was called “The Heist”. It was designed to look like the study of a rich aristocrat and visitors would enter the room in groups. Once the door was locked, a 2-minute film would begin to play. The film would introduce visitors to the backstory of the room and present them with their mission, which was to locate and steal a large diamond and get out of the room before the antagonist’s security guards storms the room (after 60 min). They were informed that they could contact the game master and ask for a limited number of hints during these 60 min. The activity is driven by the participants as individuals and as a group and is controlled by the physical environment as well as by a set of rules (of the game), in addition to limited personal interactions with the staff. This experience product was chosen as it offered contrasting conditions to the original case in terms of activity structure (unstructured rather than structured), the role of the employees (visitor steered rather than employee steered), experience foundation (fictional rather than historical basis) and group familiarity (pre-formed groups rather than groups formed by the organizers). As each group process was treated as a unique case performing within the same experience environment, the methodological design chosen for this study could also be described as an embedded multiple case study (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, Citation2014; Yin, Citation2003).

Since this study seeks to further develop and extend on Blumenthal and Jensen’s (Citation2019) immersion process model, it set out with a number of a priori constructs that shaped the initial design of the study (Eisenhardt, Citation1989). The most important constructs were immersion and involvement, which were both explicitly measured in the interview protocol. In line with previous research on immersion (Blumenthal & Jensen, Citation2019; Brown & Cairns, Citation2004; Hansen & Mossberg, Citation2013), involvement was used as an indicator of visitor progression/ recession through the immersion process. Involvement was here understood as what Abuhamdeh and Csikszentmihalyi (Citation2012, p. 258) describe as attentional involvement, which “represents the degree to which one’s attention is devoted to the activity at hand”. This understanding of involvement was used as attentional involvement has previously been linked to immersion in the literature, where it has been described as a requisite to access the experience and to experience activity engagement (Hansen & Mossberg, Citation2013).

Data collection

Data was collected through a combination of semi-structured group interviews and field observations. Field observations were conducted via a live stream of the participants inside the escape room, using the facility’s existing camera and microphone fixtures. During the observations, the researcher focused mainly on interactions between the visitors and different elements in the experiencescape (including other visitors), and the visitors’ responses to these interactions. Responses were sought after in body language, facial expressions, and verbal cues. These observations served two purposes: triangulate findings from the interviews and enable the researcher to guide the interviews towards incidents that appeared to lead to strong responses in the informants. Nine group interviews and observations with a total of 41 participants were conducted for the purpose of this study. The groups varied in size, age, gender composition and purpose of visit (see for descriptive informant data), and the interviews lasted approximately 60 min with the exception of groups 6 and 7, which lasted approx. 15 min due to time constraints. These interviews were nonetheless included as they offered a variation in terms of purpose of visit (team building) which were considered relevant to include.

The interviews were conducted directly after the participants exited the escape room to ensure that the informants still had the experience fresh in their memory. (The interview guide is attached in Appendix 2). Despite the focus of this study being on the individual and their responses, the decision was made to conduct the interviews as group interviews, as we were dependent on interviewing several informants from the same group to make the influence of individual differences stand out more clearly. To keep the focus on the individual experience of the participants, each participant was asked to draw an experience line chart (Blumenthal & Jensen, Citation2019; Hansen, Citation2014), indicating how involved they felt during the course of the experience. Each participant was then asked to go through their individual line chart, explaining what had happened during the experience, during which the researcher probed them about their responses to these incidents (see Appendix 3 for examples from the participants’ experience line charts.) After the initial run-through of each participant’s individual line chart, a shared discussion about the experience was initiated, during which the informants commented on each other’s line charts. This approach facilitated a discussion about individual differences among group members in terms of their interpretation, and experience of, the incidents that occurred during their time in the room, as well as potential reasons for these differences.

Data analysis

Data from the interviews and the observations were analyzed using the constant comparative method characteristic of the grounded theory approach, progressing, through the stages of open, axial and selective coding in a circular process (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990). This approach was chosen as it enables new theoretical constructs to emerge from the data, which was key to the present study where the goal was to explore the role of individual responses and antecedent factors in the immersion process. As previously mentioned, the study set out with a number of a priori constructs, but to ensure a proper grounding of the theory in the data, these constructs were treated as tentative and were only included in the analysis if they were found in the data.

During the initial stages of the open coding, field notes and the transcribed interviews were coded on a line-by-line basis in a circular process. Each group was coded separately before across group comparisons commenced. Through the axial coding, individual codes derived from the open coding were grouped together and categorized into a hierarchy of abstraction. The axial coding subsided when the sub-categories had reached an abstraction level where the essence of the categories was captured without important precisions being lost. As the aim of this study was to explore the role of individual responses and antecedents, the first step in the selective coding process was to determine whether individual responses also seemed to play a moderating role in the immersion process in the present case context. This was achieved by analyzing the relationship between the identified categories and comparing them to the involvement levels and stages identified in Blumenthal and Jensen’s (Citation2019) previously developed immersion process model.

In line with the previous findings of Blumenthal and Jensen (Citation2019), these initial findings pointed to individual responses as an important moderator in the immersion process. In the second phase of the selective coding, the sub-categories identified as individual responses were therefore analyzed in more detail, focusing specifically on how these factors influenced the immersion process and their relationship to the remainder of the categories identified in this study. While presented here sequentially, the coding process was circular, as emergent codes and categories were constantly compared to existing ones, in line with the principals of grounded theory analysis (Blaikie, Citation2000).

Findings

By analyzing the relationship between the categories identified in this study and comparing them to the involvement levels and stages identified in Blumenthal and Jensen’s (Citation2019) previously developed immersion process model, we were able to create a context-specific immersion process model (see ).

This model illustrates not only the stages and involvement levels identified in the present study but also the moderating role played by individual responses in the process. Similarly, to the findings of Blumenthal and Jensen (Citation2019) we were able to identify three distinct phases in the immersion process: involvement triggers, involvement worlds and the state of immersion. Each of these stages was connected to an increasingly higher level of involvement (engagement, engrossment and transcending involvement), with a gradual transition between them. Our findings furthermore showed that the participants’ immersion process was not sequential. Instead, visitors fluctuated dynamically in and out of different levels of involvement throughout the duration of the experience. A visitor could, for example, go from engagement to engrossment and then back to engagement again, as the visitors did not automatically progress into “transcending involvement”. (See Appendix 3 for illustrative examples from the participants’ experience line charts.) This fluctuation between different levels of involvement and between different stages in the immersion process seemed to largely be caused by the visitors’ individual responses to the different involvement triggers and involvement worlds they were exposed to. This finding prompted a more thorough investigation of the role of individual responses in the immersion process.

Individual responses and their influence on the immersion process

After establishing the role of individual responses as an important moderating factor in the immersion process also in the present experience context, we turned our focus towards the main focus of this study: the role of individual responses in the immersion process.

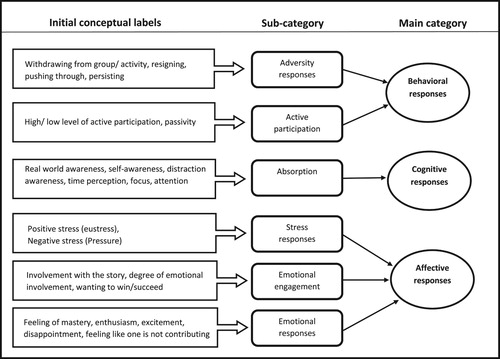

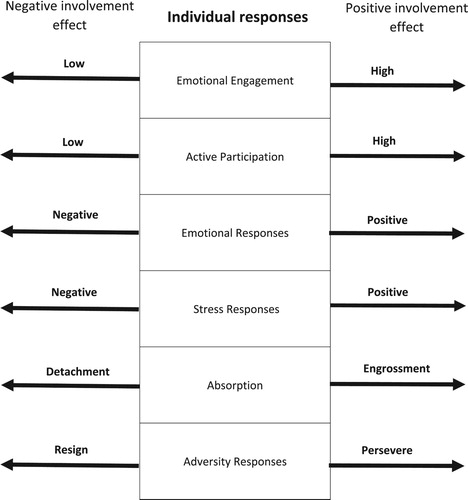

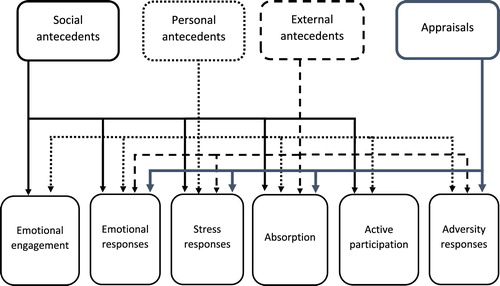

Six individual response categories were identified in our analysis as influential to the immersion process: (R1) “emotional responses”, (R2) “emotional engagement”, (R3) “stress responses”, (R4) “absorption”, (R5) “active participation” and (R6) “adversity responses” (See ). In line with Holbrook and Hirschman’s (Citation1982) experiential approach to the consumer response system, these six response categories could be classified into three different response types. Emotional engagement, emotional responses, and stress responses can all be classified as affective responses, as these were responses that were emotional in nature and involved the visitors’ feelings. Absorption, on the other hand, is a cognitive response, as it was largely subconscious, and involved the visitors’ cognitive system – their focus and attention. Lastly, active participation and adversity responses can be described as conative or behavioral responses as they included the visitors’ intentions as well as actual behavior. Each of the six response categories is presented in detail in the following section.

R1 Emotional Responses

The category “emotional responses” contained emotional responses of both positive and negative valence recorded among the informants. Positive emotional responses consisted of excitement, enthusiasm, joy, and feeling of mastery, while negative emotional responses included disappointment, frustration, and feelings of inadequacy.

Participant 25 [Birthday party]: “I love this type of intellectual tasks … And you get such a feeling of mastery when you manage to solve them!”

R2 Emotional Engagement

The response category “emotional engagement” contained codes pertaining to how emotionally engaged the visitors felt with the experience itself and with the story being presented to them in the escape room. The responses recorded in this category could be placed on a dimensional scale ranging from a high level of emotional engagement to low emotional engagement.

Participant 1 [Friend group]: “I wanted to succeed, I wanted to win … . If she [the game master] had come in a few minutes too early and not allowed us to continue I would have been pissed”.

R3 Stress Responses

“Stress responses” was another influential response category identified in this study. All the informants reported experiencing at least some level of stress during the course of experience. This was not surprising, given that time pressure is an integral part of the design of escape rooms. Experience design features such as sound, video and the pacing of the activity are all used to induce a certain level of stress in the participants. How the informants responded to this stress however varied widely. Some informants reported having a positive response to the stress, stating that the stress gave them a rush, leading them to become more focused and involved with the experience. Others, however, responded negatively to the stress, perceiving it as uncomfortable pressure negatively influenced their level of involvement with the experience.

Participant 20 [Birthday party]: “So, it was kind of a steady rising curve and then, in the end, it got a bit … Stress! And then it got very high, the level of involvement. We have to finish it!”

R4 Absorption

The category labeled “absorption” contained internal responses indicative of the informants’ level of absorption into the experience, and included indicators such as level of real-world awareness, self-awareness, focus and attention, time perception accuracy and awareness of distractions. The responses recorded in this category ranged from engrossment (positive involvement effect) on one end of the scale, to detachment (negative involvement effect) on the other end. Low real-world awareness, low self-awareness, low distraction awareness and inaccuracy of time perception paired with high levels of focus and attention was indicative of engrossment or even immersion into the experience. While high self-awareness, high real-world awareness, time perception accuracy and awareness of distractions, together with low focus and attention was indicative of a low degree of absorption or even detachment from the experience.

Participant 21 [Birthday party]: “I think I am very task-focused, because I practically forget it [distractions]. I didn’t notice any of those sounds. I think I just tune in and just step into it and just focus”.

R5 Active Participation

The individual response category labeled “active participation” denoted the degree to which the informants responded by participating actively in the experience or by becoming more passive. A strong connection was found in the analysis between active participation and increased involvement, while passivity and low levels of active participation had a similarly strong connection to decreases in involvement.

Participant 33 [Company group 1]: “And that was why it went down here in the end, because I felt I got pretty passive inside the second room. Because then it kind of became this pressure and I chose to withdraw a bit, so my own involvement goes a bit down there”.

R6 Adversity Responses

The final response category identified in the present study was “adversity responses”, which contained the visitors’ responses to the adversity they were faced with during the experience. Did it cause them to resign, withdraw from the activity/group or did it encourage them to push through and persevere? Unsurprisingly, pushing through had a positive effect on involvement, while giving up or withdrawing from the activity/group had a negative effect.

Participant 13 [Childhood friend group]: [While discussing a big drop in his level of involvement] “ … and there wasn’t enough flashlights and stuff, so then I kind of resigned. I went and did the bonus puzzle instead. So I kind of withdrew from the group and became my own thing”.

The finding that it was the valence of the visitors’ responses that influence whether their responses had a positive or negative effect on their immersion process raised another important question. What are the underlying antecedent factors that influence the valence of the visitors’ individual responses?

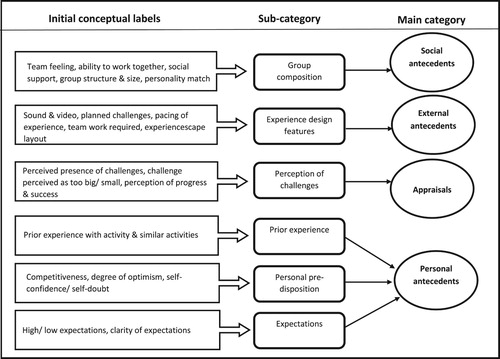

Antecedents and their influence on individual responses in the immersion process

By analyzing the relationship between the individual responses identified in this study and the remainder of the categories that emerged during our analysis, we were able to identify six antecedent factors that were found to influence the visitors’ individual responses: (A1) “group composition”, (A2) “experience design features”, (A3) “prior experience”, (A4) “personal pre-dispositions”, (A5) “expectations” and (A6) “perception of challenges”. The constructs included in each category is shown in . It is important to note that these were factors that were antecedent to the visitors’ responses, not necessarily to the experience itself.

Each of the antecedent factors presented in was found to influence several of the individual responses identified in this study. The relationship between these antecedent factors, the individual responses, and the visitors’ immersion process can be illustrated with an example from one of the groups that were interviewed: Group 7 was faced with an intellectual challenge during the experience. While participant 33 and 34 responded by participating actively in the task of trying to solve the challenge, participant 35 responded with a low level of active participation. The analysis showed that this response was influenced by a combination of her own personal pre-dispositions (insecure and not feeling comfortable in the situation) and the group composition (dominant group members “taking over”). Leading to a temporary decrease in her involvement with the experience and limiting her progression deeper into the immersion process. This example is a simplification as the visitors’ responses were also influenced by previous responses, involvement triggers, etc. that occurred earlier in the experience. In the majority of instances, the visitors’ responses were influenced by more than one antecedent factor. In the following section, the relationship between the individual responses and the antecedent factors that influenced them are described in more detail.

Antecedent factors influencing emotional responses

Our analysis showed that in the context of this case study, the visitors’ emotional responses were influenced by both social, personal and external factors, as well as by the visitors’ own appraisal of the challenges they were faced with. The positive emotional response, feeling of mastery, was for example directly related to the visitors’ perception of the group’s progression & success (perception of challenges). If the visitor felt they were not progressing or succeeding with their task, it lead to a feeling of disappointment. Whether the visitor’s emotional response had a positive or negative valence and how strongly they were felt was also moderated by personal factors, including personal pre-dispositions (competitiveness and self-confidence), the visitors’ prior experience with similar situations/activities and the visitors’ expectations going into the experience. If the visitors lacked prior experience with the activity, it could lead to a feeling of inadequacy and the feeling that they were not contributing to the group. Unclear expectations, on the other hand, could lead to positive emotional responses such as joy, excitement and a positive sense of surprise.

Antecedent factors influencing emotional engagement

Findings indicated that the visitors’ emotional engagement with the experience was influenced by both social and personal factors. Group composition played a key role, as teamwork, the group’s ability to work together and high experienced level of social support within the group were found to influence the visitors’ emotional engagement positively. In terms of personal factors, personal pre-dispositions such as competitiveness and self-confidence were found to have a moderating effect. Low self-confidence, for example, influenced emotional engagement negatively, while competitiveness could have both positive and negative effects depending on the circumstances: facilitating emotional engagement when the visitor felt they were making progress and limiting it when the visitors felt they were not making sufficient progress.

Antecedent factors influencing stress responses

Whether the informants’ stress responses had a positive or negative valence was in the present study found to be moderated by the social antecedent group composition, including group structure, group size, and social support within the group. The visitors’ stress responses were also influenced by their individual perception of the intellectual challenges they were faced with (appraisals). Time pressure, which was an integral feature in the experience design of the escape room, lead to a moderate level of stress. However, when this base level of stress mixed with a low level of social support within the group or a high level of social pressure, the stress tended to become overwhelming leading to a negative stress response in the participants. The analysis also found that personal pre-dispositions, in the form of optimism, had a moderating effect, as informants who described themselves as optimists were less inclined to respond negatively to the stress they experienced than those who did not describe themselves as such.

Antecedent factors influencing absorption

The responses in this category were mainly influenced by the social antecedent group composition and external experience design features such as planned challenges. If the visitor, for example, felt socially safe, received social support from the group and worked well with their fellow visitors, they were more likely to become engrossed in the activity. The participants’ competitiveness (personal pre-disposition) and appraisal of the challenges they were faced with also played an influential role. Their appraisals would facilitate absorption when they felt they were making good progress and that the intellectual challenges were manageable, but hinder it when the challenges were perceived as too big and they felt they were not making sufficient progress.

Antecedent factors influencing active participation

How actively the visitors participated in the experience was mediated by social factors as well as personal factors. Group structure and personality match within the group could hinder or facilitate active participation dependent on if the group had a favorable group composition or not. If the group, for example, contained members that were very dominant, they could push other less dominant members into passivity. Consequently, changes in group dynamics during the experience could have positive involvement effects for some group members if it entailed dominant group members becoming more passive (and less dominant) during the course of the experience. Teamwork was also found to play a key role as lack of teamwork was directly connected to low active involvement and passivity. In terms of personal factors, competitiveness, prior experience, and clear expectations facilitated active participation, while unclear expectations and lack of experience hindered it.

Antecedent factors influencing adversity responses

The visitors’ responses to adversity were largely moderated by their perception of the group’s progress & success (appraisals). Did they feel like they were making some progress or did they feel like they were not making any progress at all? The visitors’ adversity responses were also indirectly affected by experience design features, as time pressure and sound effects could enhance the visitors’ perception of a lack of progress. Personal pre-dispositions in the form of competitiveness were also found to affect the visitors’ ability to persist through adversity, as highly competitive participants seemed more inclined to give up when they felt they were not making sufficient progress than those who did not describe themselves as competitive. Prior experience and expectations also played a role as participants with some prior experience with the activity seemed to be expecting to succeed and therefore resigned more easily when they were met with unexpected adversity.

An overview of the relationship between the identified antecedent categories described above and the individual responses are presented in .

Discussion

This study set out with an open, explorative approach based on a single case study and the categories identified in this study are hence data-driven, but context-specific and therefore cannot readily be transferred to a wider experience context. When comparing findings from the present study with existing experience-oriented literature however, a number of conceptual connections emerge, indicating that the findings could hold validity outside the present experience context.

The dynamic nature of the immersion process

Similar to the findings of previous research (Blumenthal & Jensen, Citation2019; Hansen & Mossberg, Citation2013) in the context of tourism, the immersion process was also in the present case context found to be dynamic in nature. With visitors fluctuating in and out of different levels of involvement throughout the process. This fluctuation was found to be influenced by the visitors’ individual responses to the different incidents and occurrences (involvement trigger and involvement world) that arouse during their time in the escape room. Individual responses have also previously been identified as a moderating factor in the immersion process (Blumenthal & Jensen, Citation2019), but previous research has offered limited insights into how these individual responses influence the process and how these responses are influenced by antecedent factors. The present study thereby contribute to expand our understanding of the subjective nature of the immersion process.

Antecedents and immersion in previous research

In the present study, six antecedent factors were found to influence the visitors’ individual responses and as a consequence, the visitors’ level of involvement and progression through the immersion process. These antecedents were categorized into four main categories: social antecedents, external antecedents, personal antecedents, and appraisals. This link between social antecedents and involvement has previously been established by Zatori, Smith, and Puczko (Citation2018) who argued that social aspects, such as group atmosphere, perception of fellow visitors’ company and level of interaction within a group were key dimensions in what they described as “experience involvement”. The role of external antecedents, such as the layout of the experiencescape, as important factors influencing individual responses, has also previously been established in the tourism and service-design literature (Bitner, Citation1992; Mossberg, Citation2007; Pine & Gilmore, Citation1999).

In addition to the social and external antecedents, three personal antecedents were identified in the present study: prior experience, expectations, and personal pre-dispositions. Prior experience has been identified as a facilitating factor in several studies on immersion (Carù & Cova, Citation2005; Hansen & Mossberg, Citation2013; Jennett et al., Citation2008), but exactly how it influences the immersion process is somewhat disputed. On one side, Carù and Cova (Citation2005) argue that having prior experience can fast track consumers into a state of immersion, while inexperienced consumers require a period of familiarization before being able to become immersed. Hansen and Mossberg (Citation2013) however, argued that the novelty of an experience could facilitate immersion, as it heightens the potential for awareness and emotional involvement. In the present study, no connection was found between prior experience and emotional involvement. Instead, lack of experience with the activity was found to influence involvement negatively because it was associated with negative emotions and withdrawal from the activity. The influence of the two remaining personal antecedents is less controversial as both personal pre-dispositions and expectations have been found to moderate tourism experiences in previous studies (Adhikari & Bhattacharya, Citation2015; Walls, Okumus, Wang, & Kwun, Citation2011). The contribution of the present study, however, lays in detailing how different expectations influence individual responses in relation to the immersion process. Pointing to how clear expectations seem to facilitate active participation (which had a positive effect on involvement), while unclear expectations seemed to hinder it. Unclear expectations could however also have a positive effect on involvement, as it could facilitate positive emotional responses such as joy and excitement. The final influential antecedent identified in the present study was the visitors’ perception or appraisal of the core aspects of the experience product (the intellectual challenges). This finding is supported by cognitive appraisal theory, which postulates that an individual’s appraisal of the stimuli they are exposed to influence how they respond to that stimulus, both affectively and behaviorally (Watson & Spence, Citation2007).

Individual responses and immersion in previous research

Out of the six individual response categories identified in this study, three have been positively linked to immersion in previous studies: emotional engagement (Brown & Cairns, Citation2004; Hansen & Mossberg, Citation2013; Jennett et al., Citation2008), active participation (Hansen & Mossberg, Citation2013) and absorption (Brown & Cairns, Citation2004; Carù & Cova, Citation2007; Hansen & Mossberg, Citation2013; Mainemelis, Citation2001). Certain types of emotional responses have also previously been linked to immersion in the existing literature. Carù and Cova (Citation2005) for example, found that negative feelings increased the distance between the consumer and the experience, which they argued hindered participants from becoming immersed. While not focusing on the valence of the emotional response, Hansen (Citation2014) found that high emotional intensity could facilitate immersion. The present study did not go into the intensity of emotions experienced, but lend support to the notion that negative emotions have a negative effect on immersion.

In previous research, adversity has been identified as a factor hindering immersion (Hansen, Citation2014). Findings from the present study, however, suggest that it is not adversity in itself that hinders immersion, it is the visitors’ response to this adversity that can hinder it. Visitors who responded to adversity with resignation and withdrawal did indeed experience a decline in involvement, the opposite was however true for visitors whose response was to persevere and push through, as they experienced an increase in involvement. Our findings thus indicate that adversity can both hinder and facilitate the immersion process dependent on how the visitors respond to the adversity they are faced with.

The only individual response category identified in this study that has not previously been linked to immersion in the existing literature is stress responses. In the present study, positive stress (eustress) was found to facilitate immersion, while negative stress (distress) could hinder it by negatively influencing involvement. The term eustress was first coined by Selye (Citation1974), who considered positive stress to be favorable because it was associated with positive feelings and healthy bodily states. Negative stress (distress), on the other hand, was associated with negative feelings and unhealthy bodily states. While the present study did not focus on bodily states, it was clear that positive stress was connected to more positive emotions than negative stress. The unfavorable effect of negative stress on the immersion process might therefore be explained by the negative connection previously found by Carù and Cova (Citation2005) between negative emotions and the immersion process.

While the individual responses identified in this study were largely supported by existing literature, the contextual limitations of their applicability must not be ignored. Stress responses might for example not be as relevant to the immersion process in a low-stress experience context such as a museum visit. Similarly, other experience contexts might expose new influential individual responses that were not identified in the present study. The list of individual response sub-categories presented here is therefore neither definitive nor exhaustive. On a higher level of abstraction however, our findings indicate that cognitive, affective and behavioral responses all play an influential role in the immersion process, suggesting that the immersion process, while being a subjective cognitive process, also activates affective and behavioral responses in the consumer. More research is however needed to determine the relative importance of these different types of responses in the immersion process.

Conclusion

The main contribution of the present paper is the identification and categorization of individual responses and antecedent factors that influence the immersion process, which provides insights into the subjective nature of the immersion process. By incorporating these findings into the immersion process model proposed by Blumenthal and Jensen (Citation2019), a more inclusive, holistic model of the immersion process emerge (see ). This extended model illustrates how affective, cognitive and behavioral responses moderate the visitors’ progression through the different phases in the immersion process, from involvement triggers to involvement worlds and from involvement worlds to immersion. The model also illustrates the role of antecedent factors in influencing these individual responses, demonstrating that the visitors’ personal, social and external factors, as well as their appraisal of the core aspects of the experience, all have the potential to influence their responses. The findings of this paper hence contribute to expand our understanding of the immersion process and the factors that influence it.

Limitations and future research

Although the findings presented here are grounded in the data and developed on the basis of clear methodological procedures, they are based on a single case study and must therefore be interpreted with caution. It is however promising that the existing literature lends support to some of the key findings of this study, adding confidence to the reliability of the findings. More empirical research is however needed to determine the transferability of these findings to a wider experience context. One limitation of this study is that it is based on a case context where the activity is informant steered and where the informants have limited contact with employees. Findings from this study might therefore not be transferable to context with high levels of employee interactions.

Another limitation in the present study is that it is largely based on the informants’ retrospective self-reported levels of involvement and immersion, as these states were not measured in real-time. Other, real-time measures of immersion (such as eye-tracking) were considered but were evaluated as less appropriate for this study as they were more intrusive, and therefore considered to be more likely to interfere with the visitors’ experience. A further potential limitation of this study is that the interviews were conducted in groups. Enabling informants to potentially influence each other’s answers. Steps were however taken to reduce this limitation, mainly by triangulating interview data with field notes from the observations and asking informants to draw individual line charts at the very beginning of the interview. The interviews were furthermore conducted directly after the experience had ended, which could be a limitation as it gave the informants little time to reflect on their experience. This was however considered necessary, as we wanted to interview the participants while they still had the experience fresh in their memory.

Practical implications

Experiences are subjective and arise out of a series of complex psychological processes within the individual (Larsen, Citation2007). Tourism providers, therefore, cannot create experiences for their customers; they can only facilitate them by designing experiencescapes and circumstances with which visitors can interact to create their own experiences (Campos et al., Citation2016; Jantzen, Citation2013). Insights into the factors that facilitate individual responses favorable to the immersion process are therefore valuable to experience designers, as these insights can enable them to design experiencescapes and circumstances that are favorable to visitor immersion. While some of the influential antecedent factors identified in this study are outside the control of the experience provider (personal pre-dispositions, the visitor’s prior experience), others can, to some extent be influenced by the experience provider. The antecedent “experience design features” (planned challenges, sound & video, layout of the experiencescape, etc.) which was found to influence individual responses is a great example, as it is largely controlled by the experience provider. Experience providers can also to some extent influence the social antecedent group composition by for example imposing minimum/ maximum group sizes and encouraging teamwork and communication within the group. The experience provider also has some influence on the visitors’ expectations towards their experience product, which they can seek to influence through advertisements, online marketing, and other communication efforts. Applying the new insights generated from this study to the design of tourism experience products can thereby enable tourism providers to create experience products that facilitate visitor immersion to a greater extent.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express her deepest gratitude towards Escape Reality Trondheim for allowing me to use one of their escape rooms as a case for this article. The author would also like to thank the informants who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

ORCID

Veronica Blumenthal http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4439-9776

References

- Abuhamdeh, S., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2012). Attentional involvement and intrinsic motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 36(3), 257–267. doi: 10.1007/s11031-011-9252-7

- Adhikari, A., & Bhattacharya, S. (2015). Appraisal of literature on customer experience in tourism sector: Review and framework. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(4), 1–26. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2015.1082538

- Arnould, E., & Price, L. (1993). River magic: Extraordinary experience and the extended service encounter. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(1), 24. doi: 10.1086/209331

- Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), 57–71. doi:10.2307/1252042 doi: 10.1177/002224299205600205

- Blaikie, N. (2000). Designing social research: The logic of anticipation. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Blumenthal, V., & Jensen, Ø. (2019). Consumer immersion in the experiencescape of managed visitor attractions: The nature of the immersion process and the role of involvement. Tourism Management Perspectives, 30, 159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2019.02.008

- Brown, E., & Cairns, P. (2004). A grounded investigation of game immersion. Paper presented at the CHI ‘04 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vienna.

- Campos, A. C., Mendes, J., Do Valle, P. O., & Scott, N. (2016). Co-creation experiences: Attention and memorability. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 1–28. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2015.1118424

- Carù, A., & Cova, B. (2005). The impact of service elements on the artistic experience: The case of classical music concerts. International Journal of Arts Management, 7(2), 39–54.

- Carù, A., & Cova, B. (2007). Consumer immersion in an experiential context. In A. Carù & B. Cova (Eds.), Consuming experience (pp. 34–47). London: Routledge.

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: HarperPerennial.

- Dilek, S. E., & Dilek, N. K. (2018). Real-life escape rooms as a new recreational attraction: The case of Turkey. Anatolia, 29(4), 495–506. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2018.1439760

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. doi:10.2307/258557 doi: 10.5465/amr.1989.4308385

- Ermi, L., & Mäyrä, F. (2005). Fundamental components of the gameplay experience: Analysing immersion. Paper presented at the Digital Games Research Conference 2005, Changing Views: Worlds in Play, Vancouver.

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2004). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Sosiologisk tidsskrift, 12(2), 117–229.

- Hansen, A. H. (2014). Memorable moments: Consumer immersion in nature-based tourist experiences (no. 51-2014). Bodø Graduate School of Business, University of Nordland, Bodø.

- Hansen, A. H., & Mossberg, L. (2013). Consumer immersion: A key to extraordinary experiences. In J. Sundbo & F. Sørensen (Eds.), Handbook on the experience economy (pp. 209–227). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 132–140. doi: 10.1086/208906

- Jantzen, C. (2013). Experiencing and experiences: A psychological framework. In J. Sundbo & F. Sørensen (Eds.), Handbook on the experience economy (pp. 209–227). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Jennett, C., Cox, A. L., Cairns, P., Dhoparee, S., Epps, A., Tijs, T., & Walton, A. (2008). Measuring and defining the experience of immersion in games. International Journal of Human - Computer Studies, 66(9), 641–661. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2008.04.004

- Johnston, R., & Clark, G. (2001). Service operations management. Harlow: Financial Times Prentice Hall.

- Kim, J.-H. (2014). The antecedents of memorable tourism experiences: The development of a scale to measure the destination attributes associated with memorable experiences. Tourism Management, 44(C), 34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2014.02.007

- Kim, J.-H., Ritchie, J. R. B., & Tung, V. W. S. (2010). The effect of memorable experience on behavioral intentions in tourism: A structural equation modeling approach. Tourism Analysis, 15(6), 637–648. doi: 10.3727/108354210X12904412049776

- Larsen, S. (2007). Aspects of a psychology of the tourist experience. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(1), 7–18. doi: 10.1080/15022250701226014

- Mainemelis, C. (2001). When the muse takes it all: A model for the experience of timelessness in organization. Academy of Management Review, 26(4), 548–565. doi: 10.5465/amr.2001.5393891

- Maslow, A. H. (1964). Religions, values, and peak-experiences. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

- Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

- Mossberg, L. (2007). A marketing approach to the tourist experience. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(1), 59–74. doi: 10.1080/15022250701231915

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: Work is theatre & every business a stage. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Privette, G. (1983). Peak experience, peak performance, and flow: A comparative analysis of positive human experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(6), 1361–1368. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.45.6.1361

- Schouten, J., McAlexander, J., & Koenig, H. (2007). Transcendent customer experience and brand community. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35(3), 357–368. doi: 10.1007/s11747-007-0034-4

- Selye, H. (1974). Stress without distress. New York: New American Library.

- Slåtten, T., Krogh, C., & Connolley, S. (2011). Make it memorable: Customer experiences in winter amusement parks. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 5(1), 80–91. doi: 10.1108/17506181111111780

- Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Walls, A. R., Okumus, F., Wang, Y., & Kwun, D. J.-W. (2011). An epistemological view of consumer experiences. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(1), 10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.03.008

- Watson, L., & Spence, M. T. (2007). Causes and consequences of emotions on consumer behaviour: A review and integrative cognitive appraisal theory. European Journal of Marketing, 41(5/6), 487–511. doi: 10.1108/03090560710737570

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Zatori, A., Smith, M. K., & Puczko, L. (2018). Experience-involvement, memorability and authenticity: The service provider’s effect on tourist experience. Tourism Management, 67, 111–126. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.12.013

Appendices

Appendix 1. Descriptive informant data.

Appendix 2

Interview guide: Case study of Escape Reality Trondheim*

*The interviews for this study were conducted in Norwegian and this is a translated version of the original interview guide used in the study.

1. Opening question

Please take an experience line chart and draw a curve of how involved you felt during the course of this experience. From when the employee started their instructions before you entered the room until you were out of the escape room again after your time had ended. When you are done, please walk me through the curve and explain what was going on.

2. Topics to be covered

Context

(Purpose of visit, expectations, group type)

Interactions: Fellow visitors

(Type & influence: working together/ individually, dependency, team feeling)

Interactions: Personnel

(Type, influence)

Interactions: Physical environment

(Type, influence)

Interactions: Products/object

(Type, influence)

Internal focus: thoughts/feelings

(Type, influence)

Safety

(Social/personal/ valuables)

Time & place perception

(Awareness of time, distractions and “the real world”)

Prior knowledge/ interest/experience

(With activity, with similar activities, with experience context)

Challenge & mastery

(Perception of challenge, perception of group performance, level of focus, degree of active participation, level of involvement)

3. Closing question

Immersion is a state where you become so involved with what you are doing right here, right now that you completely forget everything else that is going on around you, including time, place and your own self-consciousness.

On a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 is the lowest. How immersed did you feel during the course of this experience? Please write down the number on your experience line charts.

Appendix 3

Examples of the informants’ Experience Line Charts

Experience line chart – Participant 3

Experience line chart – Participant 2

Experience line chart – Participant 10