ABSTRACT

The research output during the last two decades suggests that events and festivals are of major importance for society both internationally and in a Nordic context. Existing literature, primarily published in a Nordic context, is reviewed and organized according to three broad areas: The event and festival consumer, the event or festival as organization and the effects and interrelationships of events and festivals with society. We discuss the contribution which Nordic research has made to the Nordic School and to international event and festival research and suggest a future research agenda focusing on methods, context and theories.

Current state of event and festival research in a Nordic context

The spring of 2020 put an abrupt halt to the expanding event and festival sector in the Nordics and around the world. The COVID-19 crisis meant that major culture, sport and business events were cancelled or reshaped in order to meet government regulations aiming at decreasing the spread of COVID-19 (Stoksvik, Citation2020). The absence of events and festivals during these months has made the importance of events and festivals for individuals, companies, associations, destinations and society excruciatingly evident. Therefore, this is a good moment in time to both recapitulate existing knowledge and to look forward, proposing a future research agenda.

This article reviews the field of event and festival research published in SJHT during the journal’s first two decades. The aim is to provide answers to (1) which are the important areas of event and festival research in terms of methods, contexts and theories; (2) is there a “Nordic School of Events and Festival research” in spite of strong ties to international event research and (3) what might a future research agenda look like. Several reviews and syntheses of the field of event and festival research have been undertaken (Getz & Page, Citation2016; Mair & Weber, Citation2019; Mair & Whitford, Citation2013), but none focused on the Nordic research community.

Here, events and festivals are conceived of as unique and planned occurrences organized around one or more themes and limited in time and space (Jaeger & Mykletun, Citation2009). For the purpose of this review, articles are categorized and reviewed in relation to (1) the consumer, event visitors or participants applying an individual perspective; (2) the event organization, mainly from a structural or management point of view; or (3) events in society, on the role, effects and integration of events and festivals in society (Armbrecht et al., Citation2019).

Frequency of event and festival articles during the two first decades of SJHT

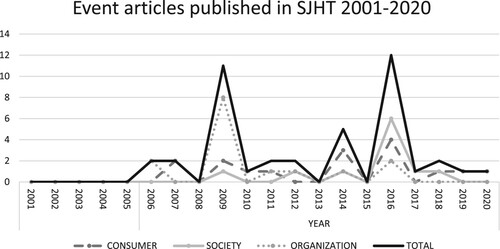

The publication of research on events and festivals in SJHT started in 2006 with two articles related to organizational issues. From 2001 to 2020, the journal has published 42 articles related to events, represented by 15 articles on consumers, 12 articles on topics related to organization and 15 articles focusing on events in society.

illustrates the distribution of publications in the three different categories and the effects from three special issues related to event studies. Volume 9 in 2009 contained a double-issue (2–3) devoted to the theme “Festival Management”, including 11 event-related articles, which left a clear mark on the publication history. Organizational perspectives dominated this special issue, which later also was published by Taylor & Francis in the form of an edited book (Andersson et al., Citation2014).

The second peak appeared in 2014 with the special issue “Advances in Event Management and Practise” in Volume 14 (3), containing seven articles, one discussion paper and an editorial. Whereas the first special issue had a Nordic focus, the second special issue was international with predominantly non-Nordic authors. The themes covered included “Green tourism”, “The effect of Web 2.0” as well as “Food events”. However, there was a dominant focus on consumer behaviour.

The third peak was produced by a special issue on “Event Impact” in 2016 (Volume 16: 2) with seven articles dominated by the theme events in society. The value of consumer experiences also attracted interest, which affected the number of articles within the field of event consumers and consumer behaviour. This special issue was also published by Taylor & Francis as an edited book (Armbrecht & Andersson, Citation2017).

Nordic and international research in events and festivals

The first four articles published 2006–2008 were written by Nordic researchers. Furthermore, the special issue “Festival Management” (Volume 9: 2–3) showcases the “Nordic School of Event Research” and 11 articles but one were written by Nordic researchers. Thus, one article in 2009 and another in 2010 establishes SJHT as an outlet for international research on events. Since then, the share of international event researchers has grown steadily even if Nordic research has continued to be the major source except for Volume 14 and Volume 17. Swedish and Norwegian researchers account for 23 of the 42 articles (55%), respectively. However, Volume 12 SJHT has attracted international event researchers, especially from Europe, possibly due to its inclusion in citation indices.

Research on event and festival consumers

Event consumers, in the role of spectators, co-creators of experiences, and in participatory roles, are at the core of event research (Getz & Andersson, Citation2010; Getz & Robinson, Citation2014; Gyimóthy, Citation2009; Heldt & Mortazavi, Citation2016; Meretse et al., Citation2016).

Larsen (Citation2007) explains experiences as expectancies and perceptions of events that are constructed in the individuals’ memory, forming the basis for new preferences and expectancies. This cognitive approach to experience highlights the central role of the experiencing subject in constructing meaning in the experiences. Studying an Icelandic horse event, Helgadóttir and Dashper (Citation2016) showed how the duality of context and individual result in insider–outsider experiences as, language, symbolism, myths of origin and markers of identity (e.g. nationality) enhance the visitor experience of belonging to either of the two groups. Selstad (Citation2007) discusses the interactive roles of event participants undertaking creative and experience-seeking activities in events in search of authenticity and cultural difference.

Pettersson and Getz (Citation2009) studied the spatial and temporal nature of event experiences. They conclude that visitors group together and that experiential “hot spots” with elements of surprise exist in the event area. Positive experiences are more important than negative ones in terms of overall satisfaction. Geus et al. (Citation2016) expanded the experience concept and developed an 18-item Event Experience Scale to map participants’ event experiences. Experience was defined as “an interaction between an individual and the event environment (both physical and social), modified by the level of engagement or involvement” (p. 277). Their study identified four experience dimensions: (1) affective engagement; (2) cognitive engagement; (3) physical engagement and (4) experiencing newness.

Getz and Robinson (Citation2014) show that food events are an important part of the destination experience. Folgado-Fernández et al. (Citation2017) show that gastronomic experiences have positive effects on visitors’ loyalty to and image of a destination. Lepp and Gibson (Citation2011) show how media-based experiences of the FIFA World Cup in South Africa changed US students’ perception of the destination with respect to risk, knowledge and conception of level of development and travel motivations.

Meretse et al. (Citation2016) developed the participants’ event experience concept into the concept of psycho-social benefits, defined as “ … the ultimate value that people place on what they believe they have gained from observation or participation in activities and interaction with settings provided by festivals” (p. 208). Based on a survey at the Stavanger Gladmat festival, they identify six psycho-social benefit factors: (1) meeting the performers; (2) tradition and celebration; (3) buying and tasting; (4) food enjoyment and atmosphere; (5) networking and socializing; and (6) personal pride and identity.

Getz and Andersson (Citation2010) propose that involved event consumers develop event-specific careers and change preferences regarding (1) motivations; (2) travel styles; (3) spatial patterns; (4) temporal patterns; (5) event choices and (6) destination choices. This model of the Event Travel Career Trajectory was supported by data from a survey of half-marathon amateur participants. In a recent study, the authors develop our understanding of why and how specialized and diversified event portfolios develop among amateur athletes (Andersson & Getz, Citation2020).

Several studies examine motivations for event and festival attendance. Gyimóthy (Citation2009) found three types of motives to attend the Extremsportveko in Voss: (1) the sport itself; (2) the event and (3) to attain intrinsic goals, such as identity construction by consuming “fetish” items. Tkaczynski and Toh (Citation2014) identified four types of attendance motivation for an Australian multi-cultural event: (1) culture; (2) escape; (3) people and (4) enjoyment. Finally, Dragin-Jensen et al. (Citation2018) explored the effect of spatial distance on motivations at a rock music festival. They show (1) socializing; (2) entertainment: interest in the event’s theme; and (3) geographical location of the event affect participants’ motivation.

Kinnunen et al. (Citation2019) identify three types of personal music preferences at Finnish rhythm music festivals. (1) The hedonistic dance crowd who love fun; (2) the loyal heavy tribe who will participate in future festivals; and (3) the highly educated omnivores who see festivals’ values as important for them. Music preferences may indicate which referential group that best reflects the festivalgoer’s own identity.

Gration and Raciti (Citation2014) studied participants’ personal values in relation to perceptions of the landscape at Woodford Folk Festival, Australia. They show that the participants’ personal values, as measured by the List of Values scale, relate to their perceptions of landscape and social-scape, linking personal values and the participants’ festival experiences.

In summary, a majority of articles addressed event participants’ experiences, both empirically and conceptually. Different types of events were studied and participants’ experiences varied accordingly, reflecting the diversity of the event sector. However, general experience categories, as identified by Geus et al. (Citation2016) may apply across events.

Four studies address the consumer motivations for participating in events. General motivational dimensions across events seem to be (1) culture, theme; (2) social aspects, socializing; (3) hedonic enjoyment; and (4) loyalty. However, other motivations seemed to be event specific. One study addressed preferences as drivers; one applied the concept of personal values; and one study focused on the benefits participants bring home from the event.

Research on event and festival organizations

Event Management has received considerable attention within network and stakeholder theory, institutional theory and economic exchange theory. Andersson and Getz (Citation2009) studied the role of ownership for event business models in terms of governance, structure and content. Three types of ownership are identified: public, non-profit and private and differences regarding decision styles, volunteer involvement and service quality were identified. Studying the Gladmat (food) festival in Norway, Einarsen and Mykletun (Citation2009) conclude that its success depends upon its embedment in a strong network of food and meal-producing institutions and organizations, restaurants and outstanding chefs, which, in turn, depends upon a tradition of food production in the area.

Karlsen and Stenbacka Nordström (Citation2009) explored the stakeholder cooperation at three festivals, which cooperate with multiple stakeholders assuming multiple roles, sometimes entering symbiosis and the festivals engage in long-stretched, “loose” and global networks. Mossberg and Getz (Citation2006) analysed how events within stakeholder constellations in Sweden and Canada co-brand themselves with names of cities, geographical areas or sponsors in their festival name. In Sweden, stakeholder involvement in the branding process was low, while in Canada it ranged from low to high. Luonila et al. (Citation2016) studied how festival managers conceptualize word-of-mouth (WOM) and reputation, affecting the establishment of a festival’s position among stakeholders and competitors. The article conceptualizes reputation and WOM within a cultural branding framework, providing an understanding of how festival reputation creates culturally meaningful messages. Nordvall (Citation2016), studying the failure to establish a Christmas Market in Åre, Sweden, explains the failure by a dysfunctional permanent organization: No working organization was established to ensure survival, and adequate goals were not guiding the production and continuous development over time.

Mykletun (Citation2009) uses resource dependency theory as frame of reference to analyse the role of seven different capitals (natural, human, social, cultural, physical, financial and administrative capital) as success factors for a festival. Jaeger and Mykletun (Citation2009) use environmental theory to describe a population of events categorized according to their focus on either music, arts, sports, markets or other themes. The latter constitute the largest category, in which each event is built around a unique theme. Live music and food sales are found at most festivals, and all festivals have more than one main activity.

Two articles discuss innovation. Studying the Roskilde festival, Denmark, Hjalager (Citation2009) demonstrates how festivals can apply an innovation systems approach. Festival organizers maintain long-term, dense and multi-faceted relations. Industries use the event as a testing ground for new products, nurturing spin-offs. Drawing upon data from three Swedish festivals, Larson (Citation2009) concludes that innovation occurs in complex networks involving many actors with various interests. The networks are often dynamic, and innovation often occurs in new partnerships. The processes are difficult to plan and may be processes originating from improvisation. However, they may also become institutionalized and embedded in the routines of the partnership.

One article addresses event safety. Studying safety management planning and practice at the Gladmat (food) festival in Stavanger, Norway, Mykletun (Citation2011) shows how a risk analysis identifies various hazards. A management plan initiated by the festival in collaboration with the police showed how to encounter each hazard in cooperation with the fire brigade, ambulance and the hospital. It was communicated through the festival organization, discussed every day at the staff morning meetings and used in evaluation exercises at the end of the event.

In sum, twelve articles address organizational issues and nine of them illustrate the importance of connections to external networks and stakeholders, which is a theoretical aspect and empirical finding applying across most of the organizational studies. One article reports on safety, one on ownership, one on branding, two on innovations and five on various forms for cooperation in networks and with stakeholders.

Research on events and festivals in society

This stream of research focuses on the role, effects and integration of events and festivals in geographical, societal and political contexts, economic development and short-term impacts, policy implications of events, and destination marketing, branding and image. Åkerlund and Müller (Citation2012) discuss to what extent co-creation has enhanced the image of the city of Umeå, which was the European Capital of Culture 2014. Richards and Marques (Citation2016) analyse the bidding process and its impacts on the local community using an extended evaluation framework for a city’s bid for European Capital of Culture. Six articles measure the economic impacts of events and festivals on communities. Kwiatkowski et al. (Citation2018) focus on visitor expenditure connected to visitor profiles in Germany. Several papers have also argued that the value of events needs to be understood from a broader perspective (Andersson & Armbrecht, Citation2014; Andersson et al., Citation2012, Citation2016; Dwyer et al., Citation2016).

Adapting, applying and refining valuation techniques from other research areas has contributed to a better understanding of the value of events to society from a welfare perspective. The methodological development of costs and benefits assessments of events has shifted the focus to value rather than financial impacts (Dwyer et al., Citation2016). Heldt and Mortazavi (Citation2016) have contributed to this methodological development, applying stated choice experiments and the travel cost method to understand current and future impacts of events. Another methodological contribution is made by (Havlíková, Citation2016) in comparing different scale measures (Q methodology and Likert scaling) in the context of residents’ perceptions of festival impacts.

In exploring societal impacts of events and festivals, three articles have proposed models that go beyond the measurement of financial impacts. Pasanen et al. (Citation2009) proposed an evaluation tool including both economic and socio-cultural impacts, empirically tested on Finnish events and Colombo (Citation2016) conceptualized the Cultural Impact Perception model (CIP) to measure cultural effects of events on communities. On a similar note, Jepson et al. (Citation2014) propose the use of the Motivation-Opportunity-Ability (MOA) model to understand how community engagement and participation could be facilitated in event and festival management.

The role of the media in influencing public perceptions of socio-cultural impacts is discussed and tested by Robertson and Rogers (Citation2009). They conclude that it is important to measure and understand this role in connection with festival image, brand narrative and stakeholder collaboration. Ulvnes and Solberg (Citation2016) emphasize the role of the media connected to future travel behaviour.

Müller and Pettersson (Citation2006) describe the roles and conflicts that may arise when events staged by indigenous people are commodified and turned into consumable experiences as compared to non-staged culture, which is difficult to experience.

In sum, most of these articles focus on the assessment or evaluation of event impacts from a quantitative perspective, often within a cost–benefit framework. There are both empirical and conceptual papers proposing evaluation models for different types of impacts and from different perspectives. Two articles have a destination management perspective examining the bidding process and co-creation of destination image, two articles focus on the role of the media, while one paper explores the use of indigenous cultures in a festival context.

Is there a Nordic school of event and festival research?

There are specific foci in all three categories, which suggest a profile of a Nordic School of event and festival research. Research on event consumers (14 articles) is characterized by quantitative studies (10), using surveys (11). The foci have been on event consumer motivation (6), and the event consumer experience (4), drawing on the state-of-the-art knowledge of experiences published in SJHT (cf. another review article in this issue).

Research on event organizations (12 articles) applies a wider spectrum of theories, but Stakeholder and network theory (6) has been the dominant perspectives, thereby possibly reflecting a Nordic view of event organizations being integrated parts of a society. However, there are also studies applying theories of, for example, brand identity, authenticity, innovation systems and risk management. From a methodological perspective, this theme is dominated by qualitative (9), case study-approaches using predominantly interviews (10), observations (7) and document analysis (6).

Finally, research on events in society (15 articles) is characterized by a wider perspective and understanding of value and impacts in society. Methodological approaches, from e.g. cost–benefit analysis (5), have been introduced in order to describe impacts on all members of a society and to discuss social, environmental and economic sustainability issues. This understanding is dominated by a quantitative approach (8) using surveys (10), but there are also prominent conceptual developments (3) to understand events in society.

Important themes, characterizing the Nordic festival and event research, are event consumer motivations and experiences (predominantly quantitative approaches), event organizations from a stakeholder and network perspective (qualitative) and event value and impacts (quantitative).

In reviews of research directions of event and festival research internationally, the most dominant wider themes are marketing, events and destinations, and management (Mair & Weber, Citation2019; Park & Park, Citation2017). Even if a comparison is difficult on the aggregate level, the Nordic research has contributed to the marketing theme (motivations and experiences), events and destinations (value and impacts) and the management theme (stakeholder and network theory) in different ways.

The synthesis highlights the contribution of the “Nordic School” to event and festival research, and also potential gaps for future research in terms of methodology, conceptualization and theory.

The future of event and festival research

To reflect on how Nordic research on events and festivals will develop is fun, interesting and not least speculative. In any way, such an agenda will not be exhaustive. We would wrap up this review article by reflecting on two types of future development that may go on parallel: a centrifugal “expanding universe” on the one hand and a centripetal focusing development on the other hand.

We support Mair and Weber (Citation2019) and call for interdisciplinary research, less single-case empirical studies, and conceptual and theoretically driven research to address the challenges discussed above. The expanding universe already includes many academic disciplines. It should delve deeper into consumers’ well-being, event experiences, short- and long-term benefits’ and the “dark sides” of events, employing positive psychology, sociology, anthropology and (auto)ethnography.

Participatory sport events have been growing in the Nordic, some of which prosper and prove to be sustainable, while others fail and close. What are success factors among surviving and sustainable events? Future research should search for common drivers of event participation in terms of e.g. hedonic and eudemonic experiences. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a unique opportunity to explore the importance of events for our personal well-being and for the social fabric of societies. Understanding these will contribute to sustainable existence of events through a better understanding of the event participant. As often is the case in real life, more emphasis should be put on managerial failures. There is a lot to be learnt from previous mistakes, and how they can be avoided (e.g. Nordvall, Citation2016). The recent COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the importance of understanding failure, crisis, innovation and recovery. Physical events and festivals have been virtually non-existent during this crisis in 2020. From an organizational perspective, the importance of innovations to survive and recover should be in focus. How can organizations learn and implement new (digital) offerings to create value for consumers and society?

It is also time to revisit earlier research and look at the long-term development of events and festivals. Some studies on events and festivals are dated and the first generations of participants (i.e. respondents) are 20 years older by now. How has the event design changed to accommodate for new participants while remaining attractive for those who have attended for many years? Themes are key elements in events – what changes can be observed? How has a changing population, with respect to age and ethnicity, influenced the event production? These 20 years of “festivalisation” create opportunities to study stability and change on the levels of the consumption and organization. Human resource management and organization theory will support knowledge development of the event organization. Ecology, sociology, logistics as well as economics, statistics, and IT related sciences and methods could help to expand our knowledge of event impacts on society and sustainability, for instance, the relations between events and tourism, environment, transportation and residents’ well-being’.

A more focused “centripetal” approach might consist of applying existing knowledge on larger entities such as managed portfolios of events or regional populations of events. Similarly, the consumer’s total event consumption rather than just a specific event could be in focus. This is conceptualized as event constellations (Andersson & Getz, Citation2020) in a forthcoming article in SJHT. The commercial concentration to multinational firms that own and control many events in different countries represents a centripetal development on the business arena. This development may lead to increased business interest and business ideologies. If so, commercialization is likely to increase, in a similar vein as in e.g. elite sports. Therefore, the effects of commercialization on participants’ and locals’ identity, attitudes, behaviour including local attachment and volunteerism, which are essential characteristics of events and festivals, deserve further consideration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Åkerlund, U., & Müller, D. K. (2012). Implementing tourism events: The discourses of Umeå’s bid for European capital of culture 2014. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 12(2), 164–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2011.647418

- Andersson, T. D., & Armbrecht, J. (2014). Use-value of music event experiences: A “Triple Ex” model explaining direct and indirect use-value of events. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(3), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2014.947084

- Andersson, T. D., Armbrecht, J., & Lundberg, E. (2012). Estimating use and non-use values of a music festival. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 12(3), 215–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2012.725276

- Andersson, T. D., Armbrecht, J., & Lundberg, E. (2016). Triple impact assessments of the 2013 European athletics indoor championship in Gothenburg. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(2), 158–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1108863

- Andersson, T., & Getz, D. (2020). Specialization versus diversification in the event portfolios of amateur athletes. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 20(4), 376–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1733653

- Andersson, T. D., & Getz, D. (2009). Festival ownership. Differences between public, nonprofit and private festivals in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 9(2–3), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250903217035

- Andersson, T. D., Getz, D., & Mykletun, R. J. (2014). Festival and event management in Nordic countries. Routledge.

- Armbrecht, J., & Andersson, T. D. (2017). Event impact. Routledge.

- Armbrecht, J., Lundberg, E., & Andersson, T. D. (2019). A research agenda for event management. Edward Elgar.

- Colombo, A. (2016). How to evaluate cultural impacts of events? A model and methodology proposal. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(4), 500–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1114900

- Dragin-Jensen, C., Schnittka, O., Feddersen, A., Kottemann, P., & Rezvani, Z. (2018). They come from near and far: The impact of spatial distance to event location on event attendance motivations. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18(sup1), S87–S100. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2018.1518155

- Dwyer, L., Jago, L., & Forsyth, P. (2016). Economic evaluation of special events: Reconciling economic impact and cost–benefit analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(2), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1116404

- Einarsen, K., & Mykletun, R. J. (2009). Exploring the success of the Gladmatfestival (the Stavanger food festival). Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 9(2–3), 225–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250903031550

- Folgado-Fernández, J. A., Hernández-Mogollón, J. M., & Duarte, P. (2017). Destination image and loyalty development: The impact of tourists’ food experiences at gastronomic events. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 17(1), 92–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2016.1221181

- Getz, D., & Andersson, T. D. (2010). The event-tourist career trajectory: A study of high-involvement amateur distance runners. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 10(4), 468–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2010.524981

- Getz, D., & Page, S. J. (2016). Event studies: Theory, research and policy for planned events. Routledge.

- Getz, D., & Robinson, R. N. S. (2014). Foodies and food events. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(3), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2014.946227

- Geus, S. D., Richards, G., & Toepoel, V. (2016). Conceptualisation and operationalisation of event and festival experiences: Creation of an event experience scale. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(3), 274–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1101933

- Gration, D., & Raciti, M. M. (2014). Exploring the relationship between festivalgoers’ personal values and their perceptions of the non-urban blended festivalscape: An Australian study. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(3), 275–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2014.946226

- Gyimóthy, S. (2009). Casual observers, connoisseurs and experimentalists: A conceptual exploration of niche festival visitors. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 9(2–3), 177–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250903157413

- Havlíková, M. (2016). Likert scale versus Q-table measures – A comparison of host community perceptions of a film festival. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(2), 196–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1114901

- Heldt, T., & Mortazavi, R. (2016). Estimating and comparing demand for a music event using stated choice and actual visitor behaviour data. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(2), 130–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1117986

- Helgadóttir, G., & Dashper, K. (2016). “Dear international guests and friends of the Icelandic horse”: Experience, meaning and belonging at a niche sporting event. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(4), 422–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1112303

- Hjalager, A.-M. (2009). Cultural tourism innovation systems – The Roskilde festival. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 9(2–3), 266–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250903034406

- Jaeger, K., & Mykletun, R. J. (2009). The festivalscape of Finnmark. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 9(2–3), 327–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250903119520

- Jepson, A., Clarke, A., & Ragsdell, G. (2014). Investigating the application of the motivation–opportunity–ability model to reveal factors which facilitate or inhibit inclusive engagement within local community festivals. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(3), 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2014.946230

- Karlsen, S., & Stenbacka Nordström, C. (2009). Festivals in the Barents region: Exploring festival-stakeholder cooperation. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 9(2–3), 130–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250903157447

- Kinnunen, M., Luonila, M., & Honkanen, A. (2019). Segmentation of music festival attendees. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 19(3), 278–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2018.1519459

- Kwiatkowski, G., Diedering, M., & Oklevik, O. (2018). Profile, patterns of spending and economic impact of event visitors: Evidence from Warnemünder Woche in Germany. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18(1), 56–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2017.1282886

- Larsen, S. (2007). Aspects of a psychology of the tourist experience. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250701226014

- Larson, M. (2009). Festival innovation: Complex and dynamic network interaction. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 9(2–3), 288–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250903175506

- Lepp, A., & Gibson, H. (2011). Tourism and world cup football amidst perceptions of risk: The case of South Africa. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(3), 286–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2011.593361

- Luonila, M., Suomi, K., & Johansson, M. (2016). Creating a stir: The role of word of mouth in reputation management in the context of festivals. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(4), 461–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1113646

- Mair, J., & Weber, K. (2019). Event and festival research: A review and research directions. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 10(3), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEFM-10-2019-080

- Mair, J., & Whitford, M. (2013). An exploration of events research: Event topics, themes and emerging trends. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 4(1), 6–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/17582951311307485

- Meretse, A. R., Mykletun, R. J., & Einarsen, K. (2016). Participants’ benefits from visiting a food festival – The case of the Stavanger food festival (Gladmatfestivalen). Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(2), 208–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1108865

- Mossberg, L., & Getz, D. (2006). Stakeholder influences on the ownership and management of festival brands. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 6(4), 308–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250601003273

- Müller, D. K., & Pettersson, R. (2006). Sámi heritage at the winter festival in Jokkmokk, Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 6(1), 54–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250600560489

- Mykletun, R. J. (2009). Celebration of extreme playfulness: Ekstremsportveko at Voss. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 9(2–3), 146–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250903119512

- Mykletun, R. J. (2011). Festival safety – Lessons learned from the Stavanger food festival (the Gladmatfestival). Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(3), 342–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2011.593363

- Nordvall, A. (2016). Organizing periodic events: A case study of a failed Christmas market. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(4), 442–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1113142

- Park, S. B., & Park, K. (2017). Thematic trends in event management research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(3), 848–861. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2015-0521

- Pasanen, K., Taskinen, H., & Mikkonen, J. (2009). Impacts of cultural events in Eastern Finland – Development of a Finnish event evaluation tool. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 9(2–3), 112–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250903119546

- Pettersson, R., & Getz, D. (2009). Event experiences in time and space: A study of visitors to the 2007 world Alpine Ski championships in Åre, Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 9(2–3), 308–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250903119504

- Richards, G., & Marques, L. (2016). Bidding for success? Impacts of the European capital of culture bid. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(2), 180–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1118407

- Robertson, M., & Rogers, P. (2009). Festivals, cooperative stakeholders and the role of the media: A case analysis of newspaper media. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 9(2–3), 206–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250903217019

- Selstad, L. (2007). The social anthropology of the tourist experience. Exploring the “middle role”. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250701256771

- Stoksvik, M. (2020, July 16). Festivaler over hele landet har fått ny smittvennlig drakt. NRK. https://www.nrk.no

- Tkaczynski, A., & Toh, Z. H. (2014). Segmentation of visitors attending a multicultural festival: An Australian scoping study. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(3), 296–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2014.946231

- Ulvnes, A. M., & Solberg, H. A. (2016). Can major sport events attract tourists? A study of media information and explicit memory. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(2), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2016.1157966