ABSTRACT

Collaboration is important for fostering tourism in a region and the creation of a shared collaborative identity facilitates this process. This paper explains the role of individual identities in the process of creating a shared tourism collaborative identity in a post-communist environment. To this end, it uses multi-grounded theory to analyse 37 individual interviews and 1 focus group interview conducted in 2 tourist destinations in Estonia. In the constantly evolving post-communist tourism environment, collaborative identity creation relates to self-construction at the individual, interpersonal, and group levels. This study shows that the place, occupational, cultural, and environmental identities in a given place shape and form shared tourism collaborative identities; however, a collaborative platform is required for shared collaborative identity creation. Specifically, during the shared collaborative identity creation, stakeholders bring their own identities to the process through the platform, on which individual and collective identities interact. The platform magnifies or weakens the perceptions of the shared collaborative identity. As collaboration broadens, the platform shifts from a small group to bigger groups. Nonetheless, during this the shared tourism collaborative identity creation is vulnerable, as stakeholders may perceive threats to their individual identities.

Introduction

The development of tourist regions requires collaboration between diverse stakeholders with different social and cultural backgrounds (Bramwell & Lane, Citation2000). The shared collaborative identities are created during collaborative processes (Öberg, Citation2016). According to Beech and Huxham (Citation2003), identity forms through interactions in complex cycles, wherein individuals distinguish between their own identities and the identities of others. Through the connections that individuals have in different relationships (Nunkoo & Gursoy, Citation2012; Stryker, Citation1968) and the choices of individuals embedded in the social structure (Stets & Biga, Citation2003), individual identities shape collaborative identities.

Collaborative identities are not always easily perceivable. The formalisation of collaboration helps one perceive a shared collaborative identity and might thus enhance the sustainability of collaboration (Öberg, Citation2016; Stets & Biga, Citation2003). Regardless of the formality level, the collaborative relationships between stakeholders can be facilitated on a collaborative platform that could be regarded “as organisations or programs with dedicate competences and resources for facilitating the creation, adaptation and success of multiple or ongoing collaborative projects or networks” (Ansell & Gash, Citation2018, p. 16). Thus collaborative platforms could have an important role in collaborative identity creation.

Diversity of stakeholders in tourism (Bramwell & Lane, Citation2000) renders the creation of shared collaborative identities a challenge. Tourism development can also affect the identities of local stakeholders (Segrestin, Citation2005). When stakeholders do not identify with the aims of regional tourism (Palmer et al., Citation2013) and perceive their identities to be under threat (Mason & Cheyne, Citation2000), separatism may occur that hinders collaboration (Kelliher et al., Citation2018).

Thus shared collaborative identity is one of the key determinants of collaboration success. Öberg (Citation2016) studied how different collective identities influence each other and collaborative identity. However, it is not known how various individual identities of tourism stakeholders form the shared collaborative identity. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to explain how individual identities relate to shared collaborative identities and the role of collaboration platform in this process. The paper answers the following research questions: (1) how individual identities relate with the shared collaboration identity and (2) how the shared collaboration identity is perceived by the stakeholders and facilitated in a post-communist tourism environment?

While established tourist regions are successful in capitalising on their tourism potential, post-communist regions lag (Cottrell & Raadik-Cottrell, Citation2015) because of insufficient collaboration due to low trust levels between stakeholders (Czakon & Czernek, Citation2016; Strzelecka & Wicks, Citation2015). Decades of centrally planned economy inhibited the development of local identities (Bożętka, Citation2013; Czernek et al., Citation2017). During and after the post-communist transition, some communities performed better in finding a clear development path than others (Annist, Citation2011). This makes fostering collaboration a challenging task because in post-communist environments, the differences in the individual identities of residents could be more accentuated than in regions with stable development.

This study was conducted in the Pärnu and Lahemaa regions in Estonia. The Pärnu region is known for its coastline and spa hotels, being one of the main tourist hotspots in Estonia. Lahemaa National Park (LNP) situated close to Tallinn, the capital of Estonia is the oldest and biggest national park in Estonia. These regions were selected to study the creation of shared collaborative identity because of differences in their size, imagery, and collaboration history.

Individuals find meaning and define themselves through their relationships with others and through their social identities. Social identity theory (SIT) distinguishes between individual, interpersonal, and collective self-creation. Individuals have multiple selves and part of a person’s concept of self stems from the different groups to which that person relates to. A certain group to which an individual belongs, and which manifests that individual’s self-perception is considered an ingroup for that person. The other groups to which the individuals can compare themselves to but does not identify with are outgroups. This creates an “us” & “them” effect (Islam, Citation2014; Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). In tourism research, SIT has been used for explaining the relationship between residents’ place-based social identity and their support for tourism (Wang et al., Citation2014), how tourism creates a place identity (Liu & Cheng, Citation2016), and the relationship between the mental stages experienced by event visitors (Chiang et al., Citation2017).

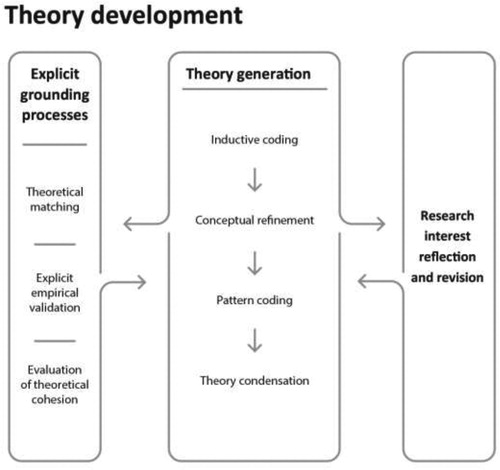

This study draws on SIT and uses multi-grounded theory (MGT) (Cronholm & Goldkuhl, Citation2010) to explain shared collaborative identity creation. The grounded theory (GT) (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967) is widely used in different scientific fields where new in-depth insights are necessary. It is a widespread approach for empirically based theory development where categories are inductively generated from empirical qualitative data. The main weakness of GT is the reluctance to use existing theories, which can lead to a knowledge loss. MGT is an alternative approach to GT that allows to synthesise existing theories and new data with theoretical, empirical, and internal grounding and develop or complement a theory bypassing the weakness of GT (Cronholm & Goldkuhl, Citation2010).

Literature review

Collaboration in tourism

Collaboration “occurs when a group of autonomous stakeholders of a problem domain engage in an interactive process using shared rules, norms and structures to act or decide on issues related to that domain” (Wood & Gray, Citation1991, p. 146). Tourism collaboration is related with embeddedness where non-economic institutions influence economic activities (Granovetter, Citation1985). Czernek-Marszałek (Citation2020) showed that when entrepreneurs are socially embedded, entrepreneurial and personal relationships overlap which helped to achieve collaboration success.

Networks are considered highly important in tourism context (Ness et al., Citation2018). Through collaboration, stakeholders form a network where nodes (e.g. groups and individuals) and ties (e.g. communication, agreements, and relationships) (Wasserman & Faust, Citation1994) connect different actors. Actors relate to each other via different ties: similarities (membership, attitude, or location); social relations (friendship or acquaintance); interactions (trade) and flows (recourses or information) (Borgatti et al., Citation2009), and thereby influence networking with their position, decisions, behaviour, or attitudes (Fyall et al., Citation2012). Both, strong and weak ties between the actors are valuable for networking (Houghton et al., Citation2009). Stakeholder relationships are also influenced by interdependence (Czakon & Czernek, Citation2016).

Stakeholders may have different reasons for collaborating, such as business development (Öberg, Citation2016), access to resources that are otherwise unavailable (Czakon & Czernek, Citation2016), and socialising with others (Pilving et al., Citation2019).

Previous literature on collaboration problems in post-communist environments has scrutinized determinants of collaborative success, the role of trust and conflicts between stakeholders. Czakon and Czernek (Citation2016) found that it is difficult to develop calculative, capability-based, and intention-based trust, and showed the importance of third party-legitimisation in the tourism network in the stakeholders’ decision to enter network coopetition. Several studies (Czernek, Citation2013; Czernek et al., Citation2017; Roberts & Simpson, Citation2000) have addressed economic, socio-cultural, demographic, legal, political, and spatial factors, and trust as determinants of collaboration success. Conflict over tourism development often arises between interested parties because of their different aims, and better-quality collaboration helps to reduce the number of conflicts (Kapera, Citation2018). Some studies (Strzelecka et al., Citation2017; Strzelecka & Wicks, Citation2015) have demonstrated how residents’ perceptions of place identity and bonding with the nature affect the perceptions of being empowered through tourism.

High seasonality, under which stakeholders often simultaneously have several different occupations to sustain their living throughout the year (Pilving et al., Citation2019), renders the Estonian tourism environment complex from the stakeholder perspective. This can influence stakeholders’ self-efficacy and entrepreneurial abilities. Thus involvement in collaborative activities and the development of social networks (Hallak et al., Citation2012) may enhance entrepreneurial success (Bredvold & Skalen, Citation2016). In the countryside, tourism collaboration projects funded by the EU through LEADER local action groups have helped to bring together different actors, formal and informal tourism networks, and local governance entities (Pilving et al., Citation2019; Strzelecka & Wicks, Citation2015). However, the success of these initiatives depends on the competences of their leaders (Czernek, Citation2013).

The role of identity in tourism collaboration

Stets and Biga (Citation2003) define identity as “a set of meanings attached to the self that serves as a standard or reference that guides behaviour in situations” (p. 401). Identity is a complex evolutionary phenomenon, constituted by individuals and collectives, and it relates to the past, present, and future (Hall, Citation1996). It is concurrently persistent and fragile, exists at several levels, can be described from individual, group, cultural, and spatial perspectives (Bożętka, Citation2013), and binds the individual to his or her surroundings (Nunkoo & Gursoy, Citation2012). Individual identity relates to one’s personality and sense of self, together with connections to the social world that influence individual awareness and self-perception (Haj-Yehia & Erez, Citation2018).

An individual’s public self consists of evaluations of oneself and of relevant others and includes self-cognitions that reflect relationships with others. The individual self-concept is based on individual perceptions of salient interpersonal relationships. Individual’s social selves can exist: (i) through interpersonal relationships with other individuals and (ii) through interpersonal collective relationships. A collective identity develops when an individual has a sense of belonging to a certain group and when the group identity becomes part of that individual’s identity. A social group consists of more than two people who share the same identity and relate to different outgroups in the same way (Brewer & Gardner, Citation1996).

According to SIT, individual social selves are derived from interpersonal relationships (Brewer & Gardner, Citation1996) inside a relatively small group of people with common views (Prentice et al., Citation1994). Individuals can simultaneously have different identities depending on their positions in society and the social networks to which they belong (Stryker & Burke, Citation2000). A better understanding of the changes in the identities of individuals helps one comprehend decision making in different social situations (Stets & Biga, Citation2003), such as shared collaborative identity creation.

Several studies have addressed the interaction between individual and organisational identities in the process of identity construction for better collaboration (Daskalaki, Citation2010; Kohlamäki et al., Citation2016; Tomlinson, Citation2008). Identities are constantly changing, but sometimes this change will stop for some period. Then the identities will become deeply rooted and are difficult to change (Beech & Huxham, Citation2003).

Tourism plays an important role in local identities (Light, Citation2001) and can hasten regional cultural, social, and landscape changes (Bożętka, Citation2013). However, identities can also construct, hinder, and influence tourism (Ballesteros & Ramirez, Citation2011; Palmer, Citation1999). In tourism context, local identity can be under threat by internal (growth of the heritage industry) and external factors (cultural change and devaluation of place meaning) (Bożętka, Citation2013). Palmer et al. (Citation2013) added that tourism marketing through images could be controversial with resident's identity.

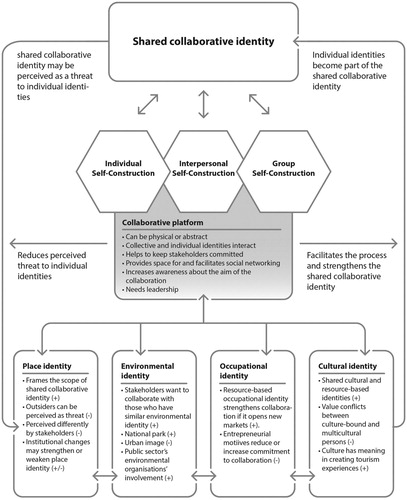

The concepts of place, occupational, environmental, and cultural identities () have been considered relevant to shared collaborative identity creation.

Table 1. Overview of different identity conceptualisations.

Individual agendas for taking part in collaboration are rather based on a person’s identity than on the identity of the collaboration. The pre-collaboration history of stakeholders hinders the perceptions of collaborative identity (Öberg, Citation2016). In situations where certain control mechanisms (compromising the independence of groups or individuals) are created, shared identity construction can easily be dismissed and a more sporadic identity formation processes can take over (Bożętka, Citation2013). However, social activities in a group can help create a shared collaborative identity when stakeholders interpret things similarly (Weick, Citation1993). Especially, if the members of a certain group consider their leader highly prototypical, they identify well with that group (Hogg et al., Citation2004).

Changes in identities in post-communist Estonia

Estonia has undergone several major socio-economic changes (e.g. a communist regime, regaining independence, opening to western markets, and attaining a membership of the European Union) in recent decades, and these have shaped local identities. After the collapse of the command economy, tourism became an important vehicle of regional development and a means of earning income (Jaakson, Citation1996; Unwin, Citation1996; Worthington, Citation2001). When Estonia became a member of the European Union (2004), new investments precipitated the growth of tourism (Jarvis & Kallas, Citation2008).

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in Estonia, cooperatives and associations were the connecting structures, which helped to form national identity and feeling of belonging at the community and personal level. During the Soviet regime, this system collapsed, and new form of collaboration – collective farming – emerged in the rural areas. However, because of the scarcity of everyday supplies, an informal network of consumer acquaintances developed alongside the collective farms. After the collapse of the communist regime, the network of acquaintances quickly became obsolete, which created a gap in the collaborative relationships. The previous system disappeared, and new one was not yet established. In the 1990s, the rural areas in Estonia began to decline in the newly formed social hierarchy and acquired a negative image in society. This hindered the creation of new collaborations and external help was needed. During that time, several development programs started, which aimed to activate residents of rural communities. These programs were more successful in regions where residents had stronger place identity. The deprivation of some community groups, their fragmentation, inability to stand up for themselves, and the dwindling of social space are processes that have not been prevented by various formally inclusive schemes developed to build a community in the rural areas (Annist, Citation2011).

The situation is even more complex because younger and older generation identify themselves differently with the relation of the turbulent past (Martínez, Citation2018). During the transformation period in towns, events oriented to build nationality were replaced by wider cultural consumption. At the same time, in the rural environment, there were very few opportunities to create and express local identity through local culture. Even more general local identity did not have a clear positive cultural expression. Local officials tried to find places and features of local significance that would direct tourists towards them, but these were mainly natural attractions. In this environment, the level of perception of a pervasive identity varies greatly from community to community (Annist, Citation2011). Consequently, the process of shared tourism collaboration identity creation in the post-communist regions is influenced by several complex aspects.

Methodology and data

Study areas

LNP is situated in northern Estonia, having a population of 3600 (2016) permanent residents. It was founded in 1971 to protect natural resources and cultural heritage. LNP is a popular natural holiday destination (Ausmeel et al., Citation2016), receiving 180,000 visitors each year (Karoles-Viia, Citation2018). Most tourism enterprises are micro-businesses that offer accommodation, food, or outdoor tourism services. Tourism is coordinated by local municipalities, the State Environmental Board, the State Forest Management Centre, and local initiatives. The region is characterised by natural landscapes, local maritime scenery, and a manor culture.

Broader issues of concern in the LNP are discussed within the Lahemaa Collaboration Assembly, which connects community members, local entrepreneurs, local municipalities, the Environmental Board, and the State Forest Management Centre. However, the Assembly does not focus strictly on tourism. The collaboration network Lahemaa Tourism Association provides collaborative platform in the form of different stakeholder gatherings and develops the shared collaborative identity.

The town of Pärnu and the surrounding rural area (in this study, they are considered one region) are situated in western Estonia and have a population of 83,000 (2016) residents (Statistics Estonia [ST], Citation2018b). Tourism in the area started in the nineteenth century, when the town of Pärnu was developed as a health resort. A modern sanatorium network was established after the Second World War, attracting visitors from across the Soviet Union. While at the time, summer house establishments attracted visits to the countryside (Kask, Citation2008), the region is still a popular summer holiday destination, with 778,000 accommodated visitors each year (2018) (Statistics Estonia [ST], Citation2020). The region includes several large spa hotels, while most tourism enterprises in the area are micro-businesses that offer accommodation, food, and outdoor activities. The region receives the second highest number of visitors in Estonia (Statistics Estonia [ST], Citation2018a) and is predominantly associated with spa and beach vacation.

In the Pärnu region, tourism collaboration between stakeholders is encouraged by local tourism organisation Visit Pärnu. Some large spa hotels from Pärnu town are members of non-profits Estonian Spa Association and Estonian Hotel and Restaurant Association that represent their members’ interests. In the countryside of the Pärnu region, collaborative activities are fostered by small local collaboration initiatives, Estonian Rural Tourism Association, and local LEADER action groups. Further, in the countryside of the Pärnu region a tourism network called Romantic Coastline (RC) has formed. The shared collaborative identity of this collaboration includes a trademark, café, and common imagery. The network engages local rural tourism enterprises, municipalities, and non-profits. The collaboration platform exists in the form of workshops, events, joint marketing, and festival network.

Data

Selective sampling under certain conditions (Flick, Citation2014) was used to find representative participants for the individual interviews in Pärnu region and focus group interview in the LNP region. Through official tourism information channels, a list of all tourism stakeholders in the study areas was created, together with information on their locations, tourism activities, and years active. The interviewees and focus group participants were required to operate in the tourism sector for longer and shorter periods, and to reflect the entire study region.

Semi-structured interviews were carried out between April 2017 and 2018 (sessions lasted from 45 min to 2 h). 37 individual interviews were conducted in the Pärnu region. In LNP, a focus group (with nine members) was conducted (). Majority of the interviewees were women over 40 years of age. Among the interviewees in the Pärnu region, there were five male and in the LNP two male entrepreneurs. All interviewees were residents of the study areas and lived there since birth or have returned to home communities after some time away. Almost all participants have additional occupations to tourism entrepreneurship in the fields of education, local municipality, LEADER local action group or some other local organisation. Majority of the interviewees are active in their home community.

Table 2. Overview of interviewees.

As Pärnu region is large and consists of many different communities and destinations, individual interviews were chosen for data collection. LNP is compact and stakeholders have better connections; there, the focus group interview was used. The interview questions covered a wide range of issues related to tourism environments; development; collaboration and networking; individual behaviour in different collaboration situations; feeling of belonging to certain collaboration, region, or community; relations with different regional destinations; place attachment; and cultural, environmental, and occupational meanings.

Conceptual and methodological approach

This study applies MGT as a methodological approach. Previously, MGT has been used for studying complex issues such as business process theory (Lind & Goldkuhl, Citation2006) and social media marketing typology (Coursaris et al., Citation2013). In the multi-grounding process, emerging theories are related to empirical data and pre-existing theories (). MGT allows to constantly refine the research aim and questions during the research process. Lind and Goldkuhl (Citation2006) show that the research design can constantly change during the research because of the interplay between interim empirical and theoretical statements and different discoveries with repeated theoretical matching and empirical validation.

Figure 1. Working structure of the MGT (Cronholm & Goldkuhl, Citation2010).

An example of the analysis process is shown in Appendix 1 (not all codes are included in the annex as it would be too voluminous). Research process in the MGT framework consists of four steps (). First, all data from the two study areas were transcribed and inductively coded. This phase is similar to open coding in GT. Data were coded as close to the text as possible, without any pre-conceptions to prevent the loss of emerging ideas and concepts. The primary categorisation of codes was done without any predetermined theoretical categorisations. In this phase, different meanings, themes, relationships, and connections (e.g. related to different identities, collaboration, socialisation, and levels of formality) started to emerge.

During the second analysis phase, conceptual refinement, all empirical statements and concepts from the first phase were challenged, critically examined, and assessed before the next categorisation (Appendix 1). During this phase, comparisons were also drawn between the codes, categories, and research notes taken during the interviews and different research stages.

In the third analysis phase (pattern coding), the assessed empirical statements (concepts after the inductive coding and conceptual refinement phases in Appendix 1 were compared to the existing theoretical concepts (, main categories in Appendix 1) and a new set of categories (interim categories in Appendix 1) was created. During this phase, the SIT concepts, such as individual, interpersonal, and group self-construction, as well as the place, environmental, occupational, and cultural identity concepts previously addressed in tourism research () were related to the codes and categories that emerged in the previous stages. In this phase, the different meanings related to individual and shared collaborative identities and the collaboration platform emerged.

Theory condensation is the final analysis phase of the MGT. It involved verifying the empirical, theoretical, and internal validity of emerging theoretical patterns and statements and comparing emerging and existing theoretical statements.

Strengths and weaknesses of MGT

MGT is a fairly novel methodological approach. So, there is still very little discussion regarding the actual advantages and disadvantages of its application. Some studies suggest that the main benefit of MGT relies upon its rigorousness and systematic approach; and that MGT allows to explain complex phenomena explicitly based on multiple sources of evidence (e.g. not only empirical data). Problematic aspects include, for instance, working with a too wide research question, or too widely described level of detail of MGT, which may not offer enough methodological support (Cronholm & Goldkuhl Citation2010; Goldkuhl & Cronholm, Citation2018).

Results

Place, environmental, occupational, and cultural identities of stakeholders

Place identity

summarizes the findings of this study – the aspects that influence place, environmental, occupational, and cultural identities, and how the individual identities relate to and facilitate the creation of the shared collaborative identity through collaborative platform.

Figure 2. The process of shared collaborative identity creation in a post-communist tourism environment.

The interviews confirmed that the shared place identity of tourism stakeholders facilitates their collaboration and frames the scope of the shared collaborative identity. In the LNP, the shared collaborative identity is strongly related to the identity of the national park and to a home community, implying a strong connection between place and environmental identities. The stakeholders have interpersonal relationships and collaboration partners are, in most cases, residents of the national park.

If place identity is strong among tourism stakeholders, the outsiders could be perceived as a threat and left out from the collaborative networks. In the LNP, the broadening of collaboration is limited because tourism stakeholders from outside the LNP that offer services in the park are largely considered as intruders. Highlighted by local entrepreneur:

We do not want to collaborate with guides from abroad.

In border areas and far from regional centres, different tourism stakeholders can perceive place identity differently. This hinders the creation of a shared collaborative identity. An excerpt from the focus group interview (the LNP) highlights:

Stakeholders in the national park constantly argue about where the borders of the park actually are, and this confusion hinders collaboration.

The Pärnu region is much larger, more fragmented, and includes many different communities. Therefore, stakeholders can be confused in peripheral, municipal, and regional border areas where different collaboration networks overlap. For instance, two guesthouses, located close to each other at the periphery of the Pärnu region, are both in the scope of RC and Green Riverland collaboration networks, which have very different identities. The first is related to coastline, while the other relates to an inland bog area. Irrespective of their spatial proximity, the stakeholders of these networks do not collaborate with each other because they identify themselves by different places. An interviewee from the RC network explains:

Our municipality locates on the borderline. Maybe it would be interesting to interview someone else from there on the forest side. They have some connection with the Green Riverland, but I would rather stick here towards the coast.

The size of an area where tourism collaboration takes place impacts the collaboration. In larger regions, stakeholders might not be aware of the activities of other stakeholders, especially when they belong to different social groups. As explained by a tourism entrepreneur in Pärnu region:

I have seen at some events that there are canoeing people there. I did not even know.

These examples demonstrate how individual views regarding the borders of a place, inhabitants of the region, and stemming place identity of the stakeholders, but also the relationships between place, environmental and occupational identities frame the scope for shared collaborative identity in tourism.

The interviewees highlighted that the communist legacy and the impacts of institutional changes have shaped place and cultural identities. For example, EU accession (new investment opportunities through regional development funds, and new clients due to free movement of people in the EU) strengthened the feeling of belonging, as it provided more support to the traditional resource-based occupations and gave stakeholders opportunities to work closer to their homes in low season. However, the recent consolidation of local municipalities and the reform of administrative centres has weakened place identity. Highlighted by the entrepreneur:

The people who live here are active, they are unique, they live in a unique place … they are already volunteering a lot. They have the motivation to do this, and if you take it away what do you voluntarily contribute then … you don’t want to do this all of your life, all the time, and contribute to it, if it’s not yours … it will lose the meaning for you.

Environmental identity

Shared environmental identity strengthens the collaboration between tourism stakeholders. Most of the interviewees highlighted that they want to collaborate with others who share the same views on environmental issues. In the LNP, the status of national park strengthens the environmental identity among stakeholders. An entrepreneur explains:

For some, forest is a living ecosystem, but for others it is a field of trees. This is a worldview conflict. For me it is easier if my collaboration partner shares the same values that I do.

The situation is more multifaceted in Pärnu. The results indicate that the environmental identity of stakeholders is related to their field of operation and their location is not always the dominant factor. Several stakeholders based close to or in the town of Pärnu do not identify their tourism activities with the spa-focused urban image, but rather with natural features of the surrounding countryside. One entrepreneur, who focuses on river tourism close to Pärnu town, explained:

My business is located at the border of Pärnu, which allows me to capitalise on the benefits of rural and urban settings. The town should focus more on new tourism experiences and not only on spa visitors. It is an old Hanseatic town with a lot of nature and a river. I will do everything in my power to promote this view of Pärnu as a sea, river, and fishing destination.

The results indicate that environmental identity plays a more significant role in shared collaborative identity creation when a public sector environmental organisation (e.g. Environmental Board) is involved in collaboration. Some of the interviewees argued that public sector participation introduces more difficulties between collaborative parties. However, others pointed out that, when tourism services are offered in environmentally sensitive regions, the participation of public sector organisations is extremely important to maintain environmental values intact. Argued in the focus group:

It is difficult to collaborate with the Environmental Board because their decision making is slow … The Environmental Board has many concerns related with the increasing visitation in the national park and their strategy is to keep this under control.

Occupational identity

Due to the high seasonality of the tourism sector, many stakeholders have multiple sources of income, such as working for local organisations or engaging in different resource-based activities (fishing, forestry, and agriculture). Therefore, tourism stakeholders may have different occupational identities that they relate to, and that influence the creation of shared collaborative identity. The entrepreneurs who undertook resource-based activities were more open for tourism collaboration. An interviewee from Pärnu region explains:

We developed all these fairs to each municipality where artisans, farmers and fishermen collaborate.

Several stakeholders from the Pärnu region who coordinate the RC collaboration mentioned the time when collective farming ended and end of a golden age of resource-based occupations:

We had two fishing related collective farms and a great factory for smoking fish here. That’s all gone now.

During the communist time everybody had cows in their yard. Last time I saw a cow in our village was almost 15 years ago.

Nowadays, the interviewees claimed that tourism provides them an opportunity to combine different occupations and provides access to a market for selling their resource-based products. As explained by a stakeholder from Pärnu:

Many locals collaborate with local tourism enterprises. For instance, we offer accommodation, but we do not have a store nearby, so we grow ourselves or buy everything from local farmers. My husband is a fisherman, so we also offer smoked fish to our customers. The market where we can sell fish is far from us and tourism allows us to sell locally.

Collaborative tourism development helps local entrepreneurs to focus on one certain activity through which they form their occupational identity. An example explains:

She suddenly started with handicraft in 2013. She had a job in the Pärnu school and this year she quit. Because of the collaboration project she is doing well in the entrepreneurship.

Such stakeholders are primarily motivated to collaborate due to the need to sustain business activities for a certain period. When tourism collaboration is infrequent and based primarily on entrepreneurial motives, collaborative relationships are less sustainable, and perceptions of shared collaborative identity remain weak. Therefore, individual self-identification through different occupations () has differing effects on shared collaborative identity.

Cultural identity

Many stakeholders in the study areas find meaning in their tourism activities through cultural traditions related to a certain place and occupations (e.g. national park, traditional woodwork, fishing, local dialects, and handicrafts). Therefore, place, resource-based occupational and cultural identities are interconnected and enhance tourism collaboration and shared collaborative identity creation. An entrepreneur from Pärnu explains:

National handicraft and local fish dishes are our tradition and history. In addition to handicrafts, it is an excellent combination.

Stakeholders from both study areas highlight the failed efforts of the communist regime to reduce their involvement with the local culture. Nowadays, many stakeholders from both study areas use local culture as tourism experience. Interviewee from Kihnu island (Pärnu region) explains:

People come here to see our culture which is connected to our tourism services.

Strong shared cultural identity could create tensions between culture-bound and multicultural individuals and thereby hinder shared collaborative identity creation. Among the interviewees were individuals with both, cosmopolitan and more local, culture-bound views, but the representatives of both groups mentioned that local cultural values are recognised by their visitors through tourism. Nonetheless, the members of both groups believe that the visitor increase may negatively influence local values which could change their views.

Collaborative platform

On collaborative platform, collective and individual identities interact, shape the scope of collaboration, and create links through common bonds and identities for themselves and others for individual and collective gain. In Pärnu region, collaborative platforms can be identified as tourism networks that form around local LEADER groups. An example is RC collaboration. The leader of this project explains the role of collaborative platform in collaborative identity creation:

In all the presentations to the locals we talked about identity. We had a lot of fuss about the acceptance of this name because the concept of romance was difficult to explain. But the idea was to get people out of the house with their pies and handicrafts and form a collaboration network.

In LNP, the entity of national park itself can be identified as a collaborative platform. Highlighted by a local stakeholder:

We have one common denominator in all of our collaborative activities, and this is the park itself which relates to everything here.

Collaborative platform provides space for social networking, facilitates the creation, perception, and salience of shared collaborative identity, increases awareness about the aims of collaboration, and helps keep stakeholders committed. It can take material form in terms of tourism facilities (e.g. cafe or hiking trail), study trips, or events that raise the quality of visitor experience, increase competitiveness, and aggregate regional tourism offerings. The important common denominator is that this “place” brings stakeholders together. A stakeholder from the LNP explains:

Ideas must be developed together somehow. Otherwise, there will be such a feeling of scrambling encapsulated alone.

Results show that the shared collaborative identity creation needs a common level that facilitates the processes of interpersonal and group self-construction, so that individual identities become part of the shared collaborative identity. The collaborative platform is that level. Stakeholders from both study regions highlight that, for collaboration in their local communities, they need a place where they can meet friends and where they can socialise and meet people with whom they do not communicate daily. Socialising with others helps them feel as being a part of the collaboration. A stakeholder from the LNP focus group explains:

For collaborative projects, we need something that stakeholders can relate to. In our village, everything is related to our community centre. One day, we have business meetings there and the next day we hold a dance party. This place helps maintain our values and identity, builds trust between us and helps to achieve our collective aims.

Interviewees point out that a common level in collaboration helps them make sense and find better content and meaning for their own activities, also how they relate with others and how group of stakeholders forms during the collaborative activities. Through a collaboration platform individual, interpersonal and group self-construction takes place.

Shared collaborative identity creation

The representative of RC collaboration explains what they try to achieve through collaborative identity:

A visitor starts to travel in this region and sees that there is a sign of that collaboration. The traveller sees that sign here and there, which already has created positive experiences a couple of times. Then the traveller wants to go to the third or fourth place, because there may be something interesting there and through that, a person experiences this diversity offered in collaboration.

Interviewees highlight that when they aim to achieve something collectively with the collaboration, the interpersonal relationships they share with acquaintances help to achieve their aims. Especially, if there is a common understanding about place, occupational, environmental, and cultural meanings which leads to shared collaborative identity creation. This point is illustrated in the individual interviews and focus-group interview by the stakeholders involved in different collaborations:

I mostly collaborate with others who see things here as I do, and this helps us to create this collaborative body together.

I collaborate with them because we have a shared history and a similar understanding of almost everything around here.

We used to work together on a collaboration project, and we are former schoolmates, so we share a lot of history and I trust them.

Interviewees point out that the existence of shared identity helps understand their individual belonging and how they relate with others and with different groups in their local community. Reflections from other community members help individuals understand their place in the world, find meaning in their life, and construct their own identities. The interviewees also discussed how different groups are formed in the community and regions and what gives meaning to those groups. Different activities, such as handicrafts, fishing and surfing, organisational affiliation (public sector organisations and entrepreneurs), and age (younger and older stakeholders form different groups) help individuals to relate with others and share collaborative identity. Explained by a stakeholder from the RC collaboration:

We started from scratch and had to create content and gather what exists here locally. It cannot be said that there was nothing here, but it did not form a whole. I think we formed this whole at least to some extent. We have combined local food, festivals and other events and handicraft as well.

Stakeholders from both study areas highlight that during the shared collaborative identity creation process with the collaboration also starts to widen. Explained by the member of the RC:

We started with only a handful of people. But we contacted personally others as well and soon we included different groups to the collaboration. The peak was reached through the study trips where members of different communities got to know each other, and the collaboration began to raise interest abroad.

Local tourism leader from the LNP adds:

I know that this will be extremely difficult but for proper collaboration we have to unite diverse groups from different municipalities and maybe some outsiders too. With only couple of people, it will be difficult to achieve our aims.

However, when the stakeholders do not identify themselves with a large collaboration then they try to find alternatives. Explained by an entrepreneur form the RC collaboration:

During the years I could not relate properly with the RC and when it started to decelerate, we created a mini version of the RC in our community.

Example from the LNP:

The Lahemaa Collaboration Council is too slow collaboration form and difficult to deal with. We need more focussed, smaller and quicker solutions.

Discussion

The relationship between individual identities and shared collaborative tourism identity

Post-communist environment

In understanding the creation of shared collaborative identity, it is important to consider the changes that have shaped the post-communist tourism environment in Estonia. Bichler and Lösch (Citation2019) highlight the role of institutional support for tourist destinations and the transformation of the institutions responsible for tourism development. Changes in the leadership and decrease in trust levels have a major impact on collaborations. In Estonia, these changes have occurred relatively abruptly and left their mark on both study regions (). A similar situation was noted in Poland, where the underdeveloped society, lack of experience, and financial problems have negatively influenced tourism collaboration (Czernek, Citation2013). In the study regions, communist time and turbulent transition period are part of stakeholder's and local identity. Older interviewees compared recent municipal reform with the merger of collective farms in the communist time. Strzelecka and Wicks (Citation2015) argue that after World War II in Poland many families moved far from home to work in collective farms, which limited their attachment with locals and caused a weak regional identity. In Estonia, the population declined drastically during the WW II and Soviet regime, which reduced people's sense of belonging (Annist, Citation2011).

The stakeholders from LNP pointed out that the new laws that accompanied the creation of the national park in the Soviet time impacted their place attachment and restricted their freedom of action. Nowadays the limitations for the land use are still there but at the other hand the national park as an institution assures that the local culture and nature are preserved (). Communist legacy is part of their regional identity as are the impacts of other major events that happened after restoring independence.

Some stakeholders are accompanied by the fear that shift of the local decision making to bigger municipalities will reduce the home feeling and separate community members. The stakeholders from Pärnu region are more concerned about the disappearance of locality than stakeholders from the LNP.

The results showed that, in Estonia, similarly to Poland, it was easier to start collaborative relationships with an individual than a group of stakeholders, especially when this group consists of strangers. In these conditions, people most likely identify themselves with their friends or acquaintances rather than with larger groups or structures. In the post-communist environment, the aging society can be a barrier to collaboration and younger people are more open minded to establishing collaborations (Czernek, Citation2013). Another hindering factor are the passive entrepreneurs who are not properly embedded in the local social structure which hinders the creation of long-term relationships and economic benefits (Czernek-Marszałek, Citation2020).

The role of individual identities

The results of this study confirm Cohen’s (Citation1985) suggestion that stakeholders who belong to one community form their own identities in the social space of their homes, while outsiders may be perceived as a threat to their identity. Institutional changes in post-communist Estonia manifest through low trust levels towards outsiders but can also influence stakeholder relationships inside a community. Uncertainty about the future reduces the level of belonging to a certain place or community. On one hand, tourism stakeholders want to achieve something in their home community (e.g. jointly owned shop, hiking trail or effective collaboration network) through collaboration and give back to the community, which strengthens their feeling of belonging to a certain place (). Common understanding about the collaboration supports the shared identity creation (Soenen & Moingeon, Citation2002). On the other hand, they fear that their achievements can fall into the wrong hands through collaboration. If stakeholders’ sense that the collaboration shifts away from their “place” and is controlled by others shared identity construction is compromising the independence of groups or individuals (Bożętka, Citation2013), shared collaborative identity creation will not succeed ().

In the study areas, people and groups find meaning and identify themselves through several different tourism related occupations and activities. However, local fishermen, artisans, and surfers depend on tourists, and collaboration gives them the opportunity to diversify the local tourism supply and keep visitors longer in the community. Because of the interdependence between stakeholders (Czakon & Czernek, Citation2016) shared collaborative identity is easy to achieve in this context, but the sustainability of this identity is questionable because stakeholders do not usually identify themselves as tourism entrepreneurs but through their occupations ().

The national park status can be important to symbolise local natural values (Haukeland et al., Citation2011). In both study regions, a common understanding about local natural values unites stakeholders. As their environmental identity forms through these values (Stets & Biga, Citation2003), different understandings of natural values may divide local tourism stakeholders into different groups. Even if tourism is beneficial to the members of both groups, they identify themselves differently, which hinders the creation of shared collaborative identity. However, environmental issues can be complex and constantly debated without finding a common ground. The interpretation of things in similar ways (Weick, Citation1993) helps overcome such issues, as does a collaborative platform with the facilitation of public organisations ().

The interviewees relate closely to work, nature and culture, and the processes of the direct individual, interpersonal, and group self-construction are continuously occurring during collaborations. From the tourism viewpoint, cultural identity is the most perceptible of these identities because interviewees use the local culture as tourist experience. As for environmental identity, cultural identity can also divide stakeholders into different groups and thus influence the creation of shared collaborative identity ().

The creation of shared collaborative identity

In Estonia, local identity is considered increasingly important for the revitalisation of rural life especially for developing tourism (Annist, Citation2011). A shared collaborative identity can only be achieved when it relates to the individual identities of stakeholders (). According to SIT, throughout a collaboration process, self-construction is related to the collaborative activities at the personal (individuals), interpersonal (connections with important others), and group levels (social identity). In the process of shared collaboration identity creation, the focus shifts from “I” to “we” (Brewer & Gardner, Citation1996). Stakeholders can identify themselves through a shared collaborative identity, as was the case with the RC. The opposite can also happen which shows the complexity of this phenomena. Öberg (Citation2016) pointed out that company-level and collaboration-level identities can exist in symbiosis where some actors commit more to the collaboration and others to their own enterprises. However, in the collaboration setting they commit to their individual identities as well ().

In tourism, collaboration with others can occur even without direct interpersonal communication, but such actions do not usually lead to shared collaborative identity creation because they remain anonymous and rather transactional than collaborative. Czernek (Citation2013) argues that, in these conditions, trust between the stakeholders is low and stakeholders are not willing to collaborate.

Collaboration activates the creation of collective identity when the most salient components of the self are shared with other group members (Brewer, Citation1991). Cognitive, communicative, organisational, functional, social, cultural, and geographical distances influence collaboration (Czernek-Marszałek, Citation2019). Differences in identity also create distance between local stakeholders and, therefore, influence the creation of a shared collaborative identity ().

European Union funded collaboration projects have received criticism (Shepherd & Ioannides, Citation2020). However, LEADER local action group can help to widen the social circle in a post-communist environment and unite different actor groups (Strzelecka & Wicks, Citation2015). Such a development also took place in Estonia. In the process of shared collaborative identity creation, different identities of the group and of individuals influence each other (Öberg, Citation2016) and group identities can be based on a collective identity or bonds between group members (Prentice et al., Citation1994). Broadening collaboration brings along a shift, where individuals in small groups that share close collaborative relationships start relationships with other groups. During the broadening phase, collaboration is shifting from the interpersonal level to the group level. Not all groups may be directly connected to tourism or to existing social networks, which makes the broadening process a challenge. These social groups also compete over status, prestige, and distinctiveness (Hogg et al., Citation2004) and, in the tourism context, consider how their identity affects others/visitors (Light, Citation2001).

According to SIT, individuals aim to reduce uncertainty about their place in the social world. They like to know their behaviour and the behaviours of others, which reduces uncertainty (Hogg et al., Citation2004). If uncertainty is not reduced during the shift from the interpersonal to the group level, shared collaborative identity creation is vulnerable because stakeholders can perceive threats to their individual identities (). When this happens, the broadening process starts to change into other collaborative formations, where stakeholders feel a lower threat to their identities.

Two persons can be fond of each other because they share a common group identity. When members of a certain group feel sympathy towards each other, the behaviour towards outsiders at the group level can be pre-emptive, thus hindering the creation of shared collaborative identity. Personal attraction based on personal identities and similar interests, attitudes, and values differs from social attraction, where ingroup members are preferred over outgroup members. Here, the entity of a certain group can be so important to a member who belongs to this group that group members are socially attractive to each other despite their dissimilarities. Even when group members do not like each other interpersonally, this type of attraction helps different groups to work together (Brewer & Gardner, Citation1996). This trend is eminent in both study regions.

According to SIT, the significance of social identity is high when individuals consider membership in a certain group to be central to their self-concept and have strong emotional ties with that group. Affiliation to a certain group helps confer self-esteem and sustain social identity (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). This study adds to SIT, in that if the collaborative identity creation at the group level moves away from or is not related with stakeholders’ individual identities, the stakeholders lose interest in creating a shared collaborative identity and try to find alternative ways for collaboration.

Collaborative platform

The entity of the collaborative platform

Previously, in tourism research the discussion on platforms has focused mostly on the concept of innovation platform, which helps stakeholders to innovate and share knowledge through an open discussion (Lalicic, Citation2018). As communication is extremely important in tourism collaboration, digitally supported platforms can help stakeholders interact (Bichler & Lösch, Citation2019; Lindström, Citation2020). The collaborative platform proposed in this study () can have a virtual or physical (e.g. community centres or clubs) presence, the organisational presence or can manifest more abstractly through stakeholder interaction. Sometimes, all these elements are present and, therefore, the collaborative platform is not directly related to the size of a collaboration network or the aim of collaboration but is primarily characterised by the nature of stakeholder relationships ().

The collaborative platform must offer a social networking element to stakeholders, serving as a communication and socialisation tool between stakeholders who work in different tourism fields and sectors, which helps to increase stakeholder's sense of belonging to a collaboration (). This is especially needed when it is difficult to find consensus in collaborative decision making (Bichler & Lösch, Citation2019).

According to Brewer and Gardner (Citation1996), “defining the individual's self-concept derives from comparisons between characteristics shared by in-group members in comparison to relevant outgroups” (p. 85). Awareness among stakeholders on the aims and relevance of collaboration helps create a mutual understanding of what place, occupational, environmental, and cultural identities mean to the different individuals who participate in collaborations. On the collaborative platform, the self and others interact, which starts the shared collaboration identity creation. This process initiates the identity perception at the personal, interpersonal, and group levels ().

Shared collaborative identity creation through the collaborative platform

This study shows that informal collaborative relationships are established between few stakeholders with constantly changing levels of interdependency. The interdependency in tourism collaboration is related with satisfying visitors’ needs because most of the collaborations focus on joint offerings and visitor sharing. This indicates that the formation of a collaboration platform is related to the interdependency level among the collaboration partners and it should evolve through the interplay between formal and informal collaborative actions.

In both study regions, it is common that small-scale collaborations start to widen. This happens between different stakeholder groups who have different needs and roles (Czernek, Citation2013). The results indicate that informal collaborations between a few people can only grow to a certain point and do not necessarily create the collaborative platform required to form a shared collaborative identity. Collaboration without the collaboration platform indicates low interdependency between partners and, in this context, establishing lasting collaborative relationships is difficult because partners can find it easier to achieve their aims unilaterally (Ansell & Gash, Citation2007).

Usually, the reason for wider collaboration is the implementation of a regional tourism policy with the aim of unifying existing collaboration networks. Now, social selves derive from the membership in larger, more impersonal collectives or social categories and collective social identities do not require personal relationships among group members or a group identity based on common identities (Prentice et al., Citation1994). During this shift, the collaboration platform also changes because the collaboration now involves different groups of different sizes that cannot always relate with other groups because of identity differences ().

Conclusion

This study explained the role of individual identities in the process of shared collaborative identity creation using SIT as theoretical basis and MGT as methodology. In the constantly evolving post-communist tourism environment, shared collaborative identity creation takes place on a collaboration platform, where stakeholders bring their own place, occupational, environmental, and cultural identities to the process.

As collaboration broadens, it shifts from a small group of people with close interpersonal relationships to other communities and regions, which include stakeholders not directly connected to the tourism region. In the shift from the interpersonal to the group level, shared collaborative identity creation is vulnerable, as stakeholders may perceive threats to their individual identities.

This study contributes to SIT by finding that stakeholders in post-communist tourism environment identify themselves with others to whom they share the same personal identities, and this helps to create shared collaborative identity at the group level.

Through shared collaborative identity creation place, environmental and cultural identity are collectively shared on a collaborative platform, where they are salient at an individual and interpersonal level. Occupational identity does not necessarily initiate collective sharing during shared collaborative identity creation but is still important for self-cognition and identifying with others involved in the collaboration. A collaborative platform thus creates common bonds and identities for oneself and others, which are needed for the collaborative identity and to keep stakeholders committed to the collaboration.

Such a platform increases or weakens the perceptions of shared collaborative identity and influences collaboration performance. While the essence of a collaborative platform depends on the collaborative environment, it is crucial to offer a social networking element to stakeholders. For high levels of perceived shared collaborative identity and a well-established collaborative platform, collaboration is more resilient.

This study offers several new insights for tourism collaboration. The findings indicate that identity is a key element to determine the scope of collaboration between different individuals and groups. The differences in identities between partners make collaboration difficult. When stakeholders are not able to identify themselves with a shared collaborative identity, they will start looking for alternative collaborations.

Collaboration without a shared collaborative identity and collaboration platform indicates a low level of interdependency between the stakeholders, which hinders the creation of lasting collaborative relationships. Understanding the idea of the collaboration platform and the importance of shared collaborative identity helps regional tourism managers and policy makers understand how different individuals and groups relate to each other, build stronger stakeholder relationships, build trust and decrease threats, create a synergy between formal and informal collaboration, find proper channels for communication and socialisation with and between stakeholders, give meaning and sense the scope of the collaboration, and most importantly, not make an effort to foster collaboration between incompatible groups.

This study has certain limitations. In addition to the occupational, place, environmental, and cultural identities, other distinct individual identities (gender) can influence the creation of shared collaborative identity. Although, the MGT proved suitable for the study of this phenomenon, other methodologies may open new avenues in the study of shared collaborative identity. Further research could focus on larger, multi-stakeholder tourism areas, where cooperation is more formal. Another research direction refers to the leadership, governance, and managerial aspects related to shared collaborative identity creation.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Estonian University of Life Sciences; and the Doctoral School of Economics and Innovation (Estonian University of Life Sciences ASTRA project Value-chain based bio-economy) for supporting publication of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Annist, A. (2011). Seeking community in post-socialist centralised villages. A study in anthropology of development. Tallinn University.

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2007). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 543–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2018). Collaborative platforms as a governance strategy. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 28(1), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mux030

- Ausmeel, H., Jürgens, K., Kingumets, K., Mets, I., Niinemägi, L., Paulus, A., & Vildak, M. (2016). Lahemaa National Park. Estonia Environmental Board. Retrieved January 08, 2019, from https://www.keskkonnaamet.ee/sites/default/public/Lahemaa_EN.pdf

- Ballesteros, E. R., & Ramirez, H. R. (2011). Identity and community–Reflections on the development of mining heritage tourism in southern Spain. Tourism Management, 28(3), 677–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.03.001

- Beech, N., & Huxham, C. (2003). Cycles of identity formation in interorganizational collaboration. International Studies of Management and Organization, 33(3), 28–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.2003.11043686

- Bichler, B. F., & Lösch, M. (2019). Collaborative governance in tourism: Empirical insights into a community-oriented destination. Sustainability, 11(23), 6673. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236673

- Borgatti, S. P., Mehra, A., Brass, D., & Labianca, G. (2009). Network analysis in the social sciences. Science, 5916(323), 892–895. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1165821

- Bożętka, B. (2013). Wolin island, tourism and conceptions of identity. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 2(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imic.2013.03.001

- Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (2000). Collaboration and partnerships in tourism planning. In B. Bramwell, & B. Lane (Eds.), Tourism collaboration and partnerships: Politics, practice and sustainability (pp. 230–246). Channel View Publications.

- Bredvold, R., & Skalen, P. (2016). Lifestyle entrepreneurs and their identity construction: A study of the tourism industry. Tourism Management, 56, 96–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.03.023

- Brewer, M. B. (1991). The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17(5), 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167291175001

- Brewer, M. B., & Gardner, W. (1996). Who is this “We"? levels of collective identity and self-representations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(1), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.1.83

- Carroll, M. S., & Lee, R. G. (1990). Occupational community and identity among pacific north-western loggers: Implications for adapting to economic changes. In R. G. Lee, D. R. Field, & W. R. Burch (Eds.), Community and forestry: Continuities in the sociology of natural resources (pp. 141–155). Westview Press.

- Cassinger, C., Gyimóthy, S., & Lucarelli, A. (2020). 20 years of Nordic place branding research: A review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1830434

- Chiang, L., Xu, A., Kim, J., Tang, L. R., & Manthiou, A. (2017). Investigating festivals and events as social gatherings: The application of social identity theory. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(6), 779–792. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2016.1233927

- Cohen, A. P. (1985). The symbolic construction of the community. Routledge.

- Cottrell, S., & Raadik-Cottrell, J. (2015). Editorial: The state of tourism in the Baltics [special issue]. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 15(4), 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1081798

- Coursaris, C. K., Van Osch, W., & Balogh, B. A. (2013). A social media Marketing typology: Classifying brand Facebook page messages for strategic consumer engagement. ECIS 2013 Completed Research, 46, https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2013_cr/46

- Cronholm, S., & Goldkuhl, G. (2010). Adding theoretical grounding to grounded theory: Toward multi-grounded theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 9(2), 187–205. 10.1177/160940691000900205

- Czakon, W., & Czernek, K. (2016). The role of trust-building mechanisms in entering into network coopetition: The case of tourism networks in Poland. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.05.010

- Czernek-Marszałek, K. (2019). Distance dimensions and their impact on business cooperation in a tourist destination. Research Papers of Wroclaw University of Economics, 63(7), https://doi.org/10.15611/pn.2019.7.17

- Czernek-Marszałek, K. (2020). Social embeddedness and its benefits for cooperation in a tourism destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 15, Article 100401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2019.100401

- Czernek, K. (2013). Determinants of cooperation in a tourist region. Annals of Tourism Research, 40, 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.09.003

- Czernek, K., Czakon, W., & Marzsalek, P. (2017). Trust and formal contracts: Complements or substitutes? A study of tourism collaboration in Poland. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6(4), 318–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.07.001

- Daskalaki, M. (2010). Building “bonds” and “bridges”: Linking tie evolution and network identity in the creative industries. Organization Studies, 31(12), 1649–1666. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840610380805

- Davis, A. (2016). Experiential places or places of experience? Place identity and place attachment as mechanisms for creating festival environment. Tourism Management, 55, 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.01.006

- Doorne, S., Ateljevic, I., & Bai, Z. (2003). Representing identities through tourism: Encounters of ethnic minorities in Dali, Yunnan province, People’s Republic of China. International Journal of Tourism Research, 5(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.404

- Flick, U. (2014). An introduction to qualitative research (5th ed.). Sage.

- Fyall, A., Garrod, B., & Wang, Y. (2012). Destination collaboration: A critical review of theoretical approaches to a multi-dimensional phenomenon. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 1(1-2), 10–26. 10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.10.002

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Aldine.

- Goldkuhl, G., & Cronholm, S. (2018). Multi-grounded theory: An update. The International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918795540

- Granovetter, M. S. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91, 481–510. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2780199

- Haj-Yehia, K., & Erez, M. (2018). The impact of the ERASMUS program on cultural identity: A case study of an Arab Muslim female student from Israel. Women’s Studies International Forum, 70, 32–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2018.08.001

- Hall, S. (1996). Introduction: Who needs identity? In S. Hall, & P. du Gay (Eds.), Questions of cultural identity (pp. 1–17). Sage.

- Hallak, R., Brown, G., & Lindsay, N. J. (2012). The place identity-performance relationship among tourism entrepreneurs: A structural equation modelling analysis. Tourism Management, 33(1), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.02.013

- Hauge, ÅL. (2007). Identity and place: A critical comparison of three identity theories. Architectural Science Review, 50(1), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.3763/asre.2007.5007

- Haukeland, J. V., Daugstad, K., & Vistad, O. I. (2011). Harmony or conflict? A focus group study on traditional use and tourism development in and around Rondane and Jotunheimen National Parks in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(1), 13–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2011.632597

- Hogg, M. A., Abrams, D., Otten, S., & Hinkle, S. (2004). The social identity perspective: Intergroup relations, self-conception, and small groups. Small Group Research, 35(3), 246–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496404263424

- Houghton, S., Smith, A., & Hood, J. (2009). The influence of social capital on strategic choice: An examination of the effects of external and internal networks relationships on strategic complexity. Journal of Business Research, 62(12), 1255–1261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.01.002

- Islam, G. (2014). Social identity theory. In T. Teo (Ed.), Encyclopedia of critical psychology (pp. 1781–1783). Springer.

- Jaakson, R. (1996). Tourism in transition in post-soviet Estonia. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(3), 617–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(95)00113-1

- Jaeger, K., & Mykletun, R. J. (2009). The festivalscape of finnmark. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 9(2-3), 327–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250903119520

- Jarvis, J., & Kallas, P. (2008). Estonian tourism and the accession effect: The impact of European Union membership on the contemporary development patterns of the Estonian tourism industry. Tourism Geographies. An International Journal of Tourism Space, Place and Environment, 10(4), 474–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680802434080

- Kapera, I. (2018). Sustainable tourism development efforts by local governments in Poland. Sustainable Cities and Society, 40, 581–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.05.001

- Karoles-Viia, K. (2018). Külastajaseire riigimetsa majandamise keskuses [Visitor monitoring in the national forest management]. Retrieved February 18, 2019, from http://pk.emu.ee/userfiles/instituudid/pk/file/PKI/loodusturismikonv/KERLI_KAROLES_VIIA_RMK_Külastajaseire_%2013_03_2018_7.pdf

- Kask, T. (2008). The development of Pärnu Resort. Retrieved December 18, 2018, from http://resort175.weebly.com/resort.html

- Kelliher, F., Reinla, L., Johnson, T. G., & Joppe, M. (2018). The role of trust in building rural tourism micro firm network engagement: A multi-case study. Tourism Management, 68, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.02.014

- Kohlamäki, M., Thorgren, S., & Wincent, J. (2016). Organizational identity and behaviours in strategic networks. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 31(1), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-07-2014-0141

- Lalicic, L. (2018). Open innovation platforms in tourism: How do stakeholders engage and reach consensus? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(6), 2517–2536. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2016-0233

- Larsen, J. (2006). Picturing Bornholm: Producing and consuming a tourist place through picturing practices. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 6(2), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250600658853

- Light, D. (2001). “Facing the future”: Tourism and identity-building in post-socialist Romania. Political Geography, 20(8), 1053–1074. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-6298(01)00044-0

- Lind, M., & Goldkuhl, G. (2006). How to develop a multi-grounded theory: The evolution of a business process theory. Australasian Journal of Information Systems, 13(2), https://doi.org/10.3127/ajis.v13i2.41

- Lindström, K. N. (2020). Ambivalence in the evolution of a community-based tourism sharing concept: A public governance approach. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 20(3), 302–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1786455

- Liu, Y., & Cheng, J. (2016). Place identity: How tourism changes our destination. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 8(2), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijps.v8n2p76

- Martínez, F. (2018). Remains of the Soviet past in Estonia: An anthropology of forgetting, repair and urban traces. UCL Press.

- Mason, P., & Cheyne, J. (2000). Residents’ attitudes to proposed tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(2), 391–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00084-5

- Medina, K. L. (2003). Commoditizing culture. Tourism and Maya identity. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(2), 353–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00099-3

- Ness, H., Fuglsang, L., & Eid, D. (2018). Editorial: Networks, dynamics, and innovation in the tourism industry. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18(3), 225–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2018.1522719

- Nunkoo, R., & Gursoy, D. (2012). Residents’ support for tourism: An identity perspective. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(1), 243–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.05.006

- Öberg, C. (2016). What creates a collaboration level identity? Journal of Business Research, 69(9), 3220–3230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.02.027

- Palmer, C. (1999). Tourism and the symbols of identity. Tourism Management, 20(3), 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00120-4

- Palmer, A., Koenig-Lewis, N., & Jones, L. E. M. (2013). The effects of residents’ social identity and involvement on their advocacy of incoming tourism. Tourism Management, 38, 142–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.02.019

- Petrzelka, P., Krannich, R. S., & Brehm, J. M. (2006). Identification with resource-based occupations and desire for tourism: Are the two necessarily inconsistent? Society and Natural Resources, 19(8), 693–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920600801108

- Pilving, T., Kull, T., Suškevics, M., & Viira, A. H. (2019). The tourism partnership life cycle in Estonia: Striving towards sustainable multisectoral rural tourism collaboration. Tourism Management Perspectives, 31, 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.05.001

- Prentice, D., Miller, D., & Lightdale, J. (1994). Asymmetries in attachments to groups and to their members: Distinguishing between common-identity and common-bond groups. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(5), 484–493. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167294205005

- Pritchard, A., & Morgan, N. (2001). Culture, identity and tourism representation: Marketing Cymru or Wales? Tourism Management, 22(2), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00047-9