ABSTRACT

The Norwegian Trekking Association (DNT) promotes outdoor activities all over Norway. It marks trails and operates 550 cabins, maintained by extensive voluntary efforts, throughout the country. Based on a case study of one area in Norway in which DNT operates, we discuss the prerequisites for the DNT system to be sustained and the challenges it faces with new tourism patterns. Two main conditions are paramount for the DNT system to develop. First, a large overlap between the core values of DNT and its guests is required. Second, the transfer of norms and conduct inherent in the system is conditioned by social encounters in real time and places, bodily experiences, and facilitated by face-to-face communication between fellow trekkers. Guests who are unfamiliar with the DNT system’s core values and code of conduct may threaten the system; increased attention to promoting the core values in informational material and mentors who guide newcomers may counteract these threats.

Introduction

The Norwegian Trekking Association (DNT) promotes outdoor activities and operates cabins all over Norway that can be used by members and non-members for a fee. Guests share cabin facilities (DNT, Citation2020d), and many cabins are unstaffed; payment is made through an honour system with no sanctions for non-compliance with the rules. Volunteers maintain the cabins and trails. After operating for 150 years, the system has proven its sustainability. Economic losses are negligible, and the number of volunteers exceeds demand. In this paper, we ask what the prerequisites are for the continued functioning of the DNT system and what challenges have emerged with new tourism patterns. Our results derive from a qualitative case study of a local DNT branch complemented by document studies and interviews with DNT at the national level.

Our focus is interesting from several angles. The DNT system facilitates outdoor recreation by offering reasonable accommodation to trekkers in most areas of Norway, which is a valuable service. DNT can also contribute to sustainable tourism. With cabin facilities offered throughout Norway, the need to build more private cabins or second homes may decreaseFootnote1 (Aamaas & Andrew, Citation2020). Building cabins that are more environmentally friendly and used in more sustainable ways may also reduce environmental impacts. Meanwhile, providing a network of cabins and footpaths throughout the country may encourage more domestic tourism, ultimately reducing greenhouse gas emissions (Aamaas & Andrew, Citation2020). Participating in outdoor recreation is also a potential pathway to greater environmental responsibility (Høyem, Citation2020). Hence, the DNT system constitutes a promising opportunity to provide green leisure solutions and encourage environmental responsibility. It is important to understand the conditions and challenges of this system to identify factors that may contribute to its maintenance and growth.

DNT is part of a Scandinavian cultural context, with societies characterised by high interpersonal trust (Skirbekk & Grimen, Citation2012). In Norway, outdoor recreation and free movement in nature are considered legal rights that should be accessible to all (Flemsæter et al., Citation2015). Using and owning cabins is central to many Norwegians’ lives; second homes comprise one-third of residential buildings in Norway, and half the population claims to own or have direct access to a cabin (Abram, Citation2012). Traditionally, these cabins were modest and built for a simple lifestyle, with no running water, water closets or luxury items (Abram, Citation2012; Kaltenborn & Clout, Citation1998). Although this trend has shifted with increased wealth (Nordbø et al., Citation2014; Tangeland et al., Citation2013), some authors identify a concurrent rise in demand for authentic experiences involving simple outdoor recreation (Engeset & Elvekrok, Citation2015; Svarstad, Citation2010; Varley & Semple, Citation2015).

DNT’s modest cabins promote nature-friendly outdoor activities. As such, an important question is whether outdoor recreation trends where tourists demand more comfort could threaten the DNT model – or if the system can survive with its traditional structure.

Many authors have addressed Norwegian cabin culture and characteristics of Scandinavian culture. However, few have specifically discussed the DNT system, and these have mostly focussed on the organisation’s history (Lyngø & Schiøtz, Citation1993) and impacts on trekking practices and national identity in Norway (Ween & Abram, Citation2012). The impact of changing tourism patterns on the DNT system has only been covered partially, presupposing that DNT and destination marketing organisations in Norway should accommodate tourists’ demands for luxury and adventure experiences (Nordbø et al., Citation2014). In contrast, we address practices, norms and codes of conduct in DNT cabins to reveal the conditions for their functioning and factors that may challenge the cabin system. Moreover, considering the potential contribution to sustainability from DNT’s model, and the need for more knowledge on sustainable nature-based tourism (Fredman & Margaryan, Citation2020), we argue that the question of how the organisation can adapt to changing tourism patterns while maintaining its current structures constitutes an important knowledge gap.

This research has been conducted in collaboration with DNT Ringerike, a local branch of DNT. We employ social practice theory to analyse the results and identify prerequisites for the system’s functioning.

Context

DNT’s material structures

DNT is the largest outdoor recreation organisation in Norway, with over 300 000 members. It has an extensive cabin network across the country, with 550 staffed lodges, self-service cabins and no-service cabins as of 2020. The staffed lodges serve meals, and many have showers and electricity. The self-service cabins are equipped with everything trekkers need for their stay, including firewood, gas, kitchen utensils, table linen and bedding; they include food for purchase, reducing the need for visitors to bring provisions. Some have solar-powered lighting, but most have no electricity. Finally, other than food, the no-service cabins offer the same facilities as the self-service cabins.

Self-service and no-service cabins are unstaffed. Guests register what they owe for their stay and pay afterwards. DNT also marks a 20 000 km network of trails and 4000 km of cross-country skiing tracks (DNT, Citation2020b). The cabin facilities and trails are maintained by the extensive voluntary efforts of 57 local trekking associations (DNT, Citation2020c).

Volunteer members of the local DNT branches perform maintenance work by replenishing firewood, gas and linen supplies and cleaning the cabins occasionally. DNT has few problems finding volunteers. Many cabins are maintained by the same people for years; especially, elderly members do “an impressive amount of work” to maintain the cabin facilities (personal communication, DNT staff member at national level). The Swedish Trekking Association (STF) provides an interesting contrast to DNT. It has an objective similar to the one of DNT, stating that its aim is to make the Swedish mountain landscape more accessible to all. It has around 238 000 members and over 200 accommodations including many cabins similar to those of DNT (Svenska Turistföreningen, Citation2017). However, in contrast to the Norwegian system, most of these cabins have cabin hosts who manage the accommodations, clean, distribute beds and take payments from the guests.

DNT’s values

DNT was founded in 1868 by Thomas Heftye to make it “easy and cheap for many to come and see the largesse and beauty of our country” (DNT, Citation2020a). This continues to be DNT’s objective; its mission is to promote “simple, active and nature-friendly outdoor activities and to safeguard the natural and cultural foundation for such activities” (DNT, Citation2020e). The DNT mission statement is intricately connected to the Norwegian concept of friluftsliv (lit. “open-air life”, outdoor recreation),promoting simple, versatile and environmentally friendly activities (DNT, Citation2020e).

Although not explicit in DNT’s mission statement, frugality is an element of friluftsliv. Guests are asked to use such resources as firewood sparingly. At one cabin, Fønhuskoia, a sign on the wall quotes Mikkjel Fønhus, the writer for whom the cabin is named: “Frugality is a virtue”. This hints at how guests should behave. The names of the DNT cabins connote frugality and a simple lifestyle. The cabins in our field study area were termed koie, a term signifying a “primitive (timber) cabin (used by hunters and loggers)” (Det Norske Akademis Ordbok, Citation2020c); DNT Ringerike’s cabins are in an area where extensive logging and timber rafting took place over hundreds of years (Bygdeutvalget, Citation2008).

Thomas Heftye stated that his vision was to create a system that made it both affordable and accessible for many to enjoy friluftsliv. When linked to a perception of Norwegian nationalism as promoting equality (Gullestad, Citation1990), friluftsliv also signifies that, in nature, people meet on equal terms regardless of background (Ween & Abram, Citation2012). The Queen of Norway has stayed at DNT cabins on her many trekking and skiing trips. In a local newspaper interview, a guide who was promoting a tour in one of the Norwegian mountain areas commented, “We can hardly complain about the standard. If it is good enough for Norwegian Queen Sonja and Danish Queen Margrete, it is probably good enough for us commoners as well” (Hamar Arbeidsblad, Citation2012).

Finally, the appearance and maintenance of the cabins is largely the guests’ responsibility. Hence, DNT’s central values also encompass trust.

DNT’s relationship with Norwegian national identity, values and traditions

Ween and Abram (Citation2012) argue that, from its foundation in 1868, DNT and Norwegian nation building and national identity have been mutually influential. By incorporating every remote natural area into the national space, the DNT network of trails and lodges gives Norwegians a sense of living in a communal, national landscape. DNT also played a role in naming uninhabited mountain areas, often giving names connected to a mythological past (Ween & Abram, Citation2012).

Dugnad is a tradition of communal voluntary work that is widespread in Norwegian society (Myhre, Citation2020) and plays a significant role in the DNT system. Norway and the Scandinavian countries are also characterised by high levels of interpersonal and institutional trust (Skirbekk & Grimen, Citation2012), which may also underlie DNT’s honour system for payment and use.

Since its establishment, DNT has played an important role in cementing the concept of friluftsliv as integral to Norwegians’ national identity. The Norwegian Ministry of the Environment (Citation2000–Citation2001) defines friluftsliv as “residency and physical activity in open air during leisure time with the aim of providing change of scenery and nature experiences”. Traditionally, the concept has been linked to an ideal of meaningful experiences of nature through slow movement, such as hiking and cross-country skiing (Varley & Semple, Citation2015). This concept is not unique to Norway and has been described as a “taken-for-granted” ideology across the Nordic countries (Gurholt & Haukeland, Citation2019, p. 177).

In the Nordic model of friluftliv, nature and the outdoors are a common good that should be “easily and equally accessed and open to all” (Flemsæter et al., Citation2015, p. 343). Participation in friluftsliv can serve as a pathway to greater environmental awareness and sustainability (Høyem, Citation2020). At its core, it traditionally centres simple and low-impact outdoor recreation, encouraging participants to learn the skills and knowledge necessary to navigate challenging natural environments and promoting reflection on the relationship between humans and nature (Høyem, Citation2020; Ween & Abram, Citation2012).

The ideal of using simple, traditional skills and technologies to subsist in nature can be seen in the Norwegian cultural concept of hytteliv (lit. “cabin life”). Second homes (cabins or hytter) in rural areas, usually in the mountains or by the sea, are widespread in Norway and the Nordic countries (Müller, Citation2020). Traditionally, they have been built to a relatively simple standard of living (without facilities like electricity or running water), and their simplicity and the skills and labour required to stay in them add to their appeal (Abram, Citation2012; Kaltenborn & Clout, Citation1998). As the British anthropologist Pauline Garvey (Citation2008, p. 203) discovered to her puzzlement, in Norwegian hytteliv, “the more crude and uncomfortable an experience the more authentic it is”.

DNT has played a key role in facilitating Norwegian friluftsliv through its material structures and legal and political advocacy (Ween & Abram, Citation2012). The organisation supported the 1957 Norwegian Outdoor Recreation Act (Ween & Abram, Citation2012), which states, “any person is entitled to access to and passage through uncultivated land at all times of year, provided that consideration and due care is shown” (Norwegian Government, Citation1957). This right of free access to natural landscapes distinguishes Norway from many other countries.

Change and tensions in Norwegian outdoor recreation

The traditional structures and concepts shaping Norwegian outdoor recreation are changing. Tensions from the demographic changes and rising affluence in Norway, increased international tourism and changing priorities among domestic and international tourists are evident.

Internationally, the demand for nature-based tourism has risen substantially, and Norway has sought to attract such tourism (Elmahdy et al., Citation2017; Stensland et al., Citation2018). However, increasingly affluent domestic and international user groups prioritise such factors as luxury, comfort and adventure/thrill-seeking over the simple and stoic “slow adventure” idealised in traditional concepts of friluftsliv (Nordbø et al., Citation2014; Tangeland et al., Citation2013). Nevertheless, tourism that is more in line with friluftsliv, motivated by a desire to break from modernity by connecting with nature and experiencing “authentic” rural life, has also risen in appeal (Engeset & Elvekrok, Citation2015; Svarstad, Citation2010; Varley & Semple, Citation2015), and has been shown to be particularly popular among environmentalists (Wolf-Watz et al., Citation2011).

The ideal of the Norwegian outdoors as “easily and freely accessible by all” has been problematised. The widespread discourse of friluftsliv as an egalitarian practice and common good conceals its historical alignment with the priorities of urban elites (Gurholt, Citation2008; Gurholt & Haukeland, Citation2019). However, rising affluence in Norway has made both friluftsliv and hytteliv accessible to a broader population and driven an expectation for higher living standards and a higher level of comfort and convenience in cabins (Abram, Citation2012; Vittersø, Citation2007). Still, the traditional view of friluftsliv continues to be sanctioned by government entities and officials (Flemsæter et al., Citation2015), as well as used as a basis for educating Norwegian nature guides (Andersen & Rolland, Citation2018). This is arguably more sustainable and focussed on participants’ environmental responsibility (Høyem, Citation2020; Varley & Semple, Citation2015).

Norwegian tourism organisations have been criticised for clinging to the old form of outdoor recreation at the expense of offering luxury and adventure experiences (Nordbø et al., Citation2014). This highlights tensions between the Norwegian government’s goals of growth in the tourism industry and increasing sustainability and environmental responsibility. As a primary actor shaping Norwegian outdoor recreation, DNT’s work is affected by these tensions.

Analytical framework

We focus on the prerequisites for the current functioning of the DNT system and the challenges emerging from new tourism patterns, considering the interactions among guests using the DNT cabins, the norms and rules set up by DNT and the system’s underlying values. In this regard, it is important to understand why and how guests adhere to the rules and norms. This guides our choice of analytical framework, leaning on elements from social practice theory, social learning theory and theories of social norms.

Shaping practices

Social practice theory responds to one-directional understandings of human action in economics and sociology (Reckwitz, Citation2002; Strengers, Citation2013). In economic theory, individual action results from preferences and such factors as prices and income, while in sociology, social structures often control individual action. Rather than focussing on individuals or social groups, social practice theory considers practices as they unfold in everyday life (Shove & Walker, Citation2010; Spaargaren, Citation2003). The main elements that constitute practices are debatable, but most scholars agree that three main aspects – meanings, skills and material factors – structure practices (Shove et al., Citation2012).

Social practice theory focusses on how everyday practices are shaped by interactions between individuals and the structures they relate to. According to Sewell (Citation1992), structures come in two forms. First, cultural schemes or frameworks of meaning (e.g. norms, values and codes of conduct) influence how people think, act and feel. Second, “real” structures (e.g. material objects, knowledge, and natural resources; regulations, laws and formalised procedures) affect practices. This theory has gained attention in several research domains, such as studies of energy savings, renewable energy technologies and mobility and consumption (Cass & Faulconbridge, Citation2016; Shove & Walker, Citation2010; Warde, Citation2005; Winther, Citation2008).

We use the framework for analyses of practices developed by Westskog et al. (Citation2011) to operationalise practices in our context. Here, practices are conditioned by human and nonhuman factors on various levels (society, group, individual). The factors are material, skills and knowledge and norms and values (Strengers, Citation2013). A configuration of all factors on all levels constitutes a person’s “field of rationality”.

Changes in factors may modify practices. Moreover, a field of rationality comprises a modus operandi or logic that individuals relate to in their recreational activities.

The importance of social learning and social norms

Wilhite (Citation2014) draws attention to the importance of bodily experience in initiating and sustaining practices. Based on Mauss (Citation1936/Citation1973), Wilhite argues that our lived experiences form practices, which are created in the interaction between internal forces – dispositions that are established though socialisation and experience – and the external forces constituted by the context. This view also provides a link to social learning theory. Learning is not only about acquiring knowledge but also relates to the interactions between our cognition and bodily experiences. Hence, learning occurs through participation in practices that may involve others (Lave, Citation1993; Wilhite, Citation2014).

Linked to the insights of social learning theory is the question of why people choose to follow norms even without fear of sanctions (e.g. Cialdini et al., Citation1990; Larimer et al., Citation2020; Schultz, Citation1999). Cialdini et al. (Citation1990) categorise norms as descriptive or injunctive. Descriptive norms relate to what is commonly done, whereas injunctive norms refer to what is commonly approved and socially sanctioned (see Cialdini et al., Citation1991). Even without sanctions, descriptive norms have a powerful behavioural impact (Cialdini, Citation2007; Simpson & Willer, Citation2015): Internalised moral schemes of self-discipline (Foucault, Citation1980; Pylypa, Citation1998) may create feelings of guilt if the rules are not followed, representing a form of internalised sanction.

Face-to-face communication among group members greatly increases the willingness to adhere to group norms (Balliet, Citation2010; Ostrom, Citation2000). Communication allows group members to create a common understanding of what is expected and coordinate these expectations (Simpson & Willer, Citation2015). However, the willingness to cooperate may be negatively affected by changes in institutions and their logics. Gneezy and Rustichini (Citation2000) show that, if the underlying assumptions guiding actions are changed, the moral motivation for adhering to the group’s rules might be supplanted, for instance, by a market logic involving calculations of personal financial cost and benefit from using the system. This is often referred to as “crowding out of moral motivation” (Frey, Citation1997).

Methods

This study of the DNT system was part of a large project on sharing involving case studies of four sharing systems – car sharing, sharing in neighbourhoods, community-supported agriculture and cabin sharing. Practice theory was the main theoretical framework. We investigated sharers’ practices in the different sharing systems, studying the skills and knowledge of sharers, relevant norms and values and material conditions of importance for sharers and the sharing system. Finally, we addressed sharers’ interactions with others.

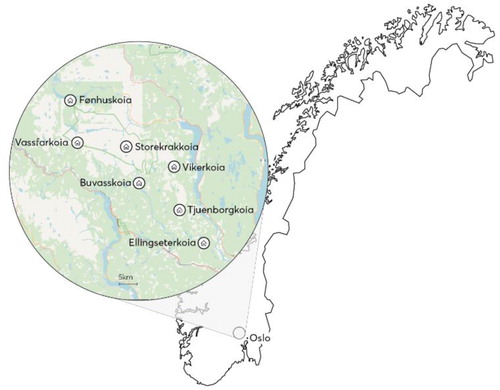

Here, we have collaborated with a local DNT branch, DNT Ringerike, which owns and maintains nine cabins. Seven cabins located between the town of Hønefoss and forest and mountain area Vassfaret to the north were selected for our study ().

Our empirical material derives from observations at DNT cabins, document studies, interviews with guests and in-depth interviews with members of DNT Ringerike. A mapping survey was carried out among the DNT Ringerike members. The study follows the ethical guidelines of the Norwegian Centre for Research Data, which approved the method of data collection for this study.

Observations

The cabins were visited during summer, autumn and winter holidays. The number of guest nights over one year ranged from 34 in Ellingseter cabin, inaugurated half a year ahead of the fieldwork, to 640 in Fønhuskoia cabin.

We made observations of guests’ behaviour during their stay or after their departure. When at cabins where other guests were present, the researchers participated in the expected routines, creating an overlap between the guest and researcher roles and allowing access to social relations embedded in the practices (Rosen, Citation1991). Active researcher involvement in what is supposed to be observed may alter the guests’ behaviour, and it is context dependent, as the researchers’ position and behaviour may be difficult to replicate; however, using multiple data sources may mitigate these weaknesses (Aase & Fossåskaret, Citation2014).

Many cabins did not have guests when we visited, and our observations took place after the visits. We considered whether guests had readied firewood for the next visitors, made the beds, swept or washed the floors or replaced the candles. We also looked at how the cabins were maintained and how those responsible for the cabins communicated with the guests through notices posted on walls or tables. We made detailed notes of observations.

Document studies

We registered entries in guestbooks and protocols at the cabins. Registration in the guest protocols is mandatory. Guests must give their name, membership information, dates of arrival and departure, their previous and next destination, and what they are paying for their stay. We limited our registration of the written records to one year prior to our visit. In the guestbooks, people often gave their views about the cabin and wrote about what they did and where they trekked. Many gave recommendations for measures needed to keep the cabins in order. We summarised the main points from the written material following the main categories of the interview guide (see below). We used newspaper articles, DNT’s website and relevant documents from other local DNT branches for document studies.

Survey

A digital questionnaire was sent by e-mail to all 1036 members of DNT Ringerike. Ninety-three responded (37 men, 56 women), representing a response rate of 9 percent. We cannot draw general conclusions from such a low response rate, and we only refer to the survey cautiously.

The survey questions focussed on motivations for visiting the DNT cabins and information about the use patterns. We were also interested in gaining an overview of perceived barriers to and benefits of using the cabins, forming a basis for the in-depth interviews with DNT Ringerike members.

Interviews and possible weaknesses of our research

We conducted interviews with guests at the cabins we visited and in-depth interviews with DNT Ringerike members after the cabin visits. We asked guests about their practices, if they diverged from rules set by DNT and why, their views on sharing the cabins with others and the DNT system in general. We interviewed two individual guests and two families. The interviewees were all told who we were (researchers) and the purpose of our visit.

In the survey questionnaire, respondents were asked if they would be willing to participate in in-depth interviews, and 16 agreed (11 men, 5 women). The age distribution of the informants is shown in .

Table 1. Age distribution of in-depth interviewees.

The authors each carried out eight interviews, conducted at a hotel in Hønefoss or at informants’ homes. The informants included members with no responsibilities within the DNT system and koiesjefer (cabin managers), who were responsible for specific cabins.

The interviews were semi-structured, allowing respondents to broach issues that concerned them. Inspired by practice theory (Shove & Walker, Citation2010), an interview guide was developed covering the following main topics. We addressed informants’ practices at cabins; relations to friends, relatives and other guests with respect to using the DNT cabins; and perceived benefits and challenges of using DNT cabins (including the DNT rules). We also addressed what informants considered to be a good life and how that related to hiking and using DNT cabins. Finally, we addressed consumption habits to gather comparative data for the larger research project.

The interviews were recorded, and detailed notes were made on the main interview guide topics. As Aléx and Hammarström (Citation2008) argue, every interview and observation situation is context dependent and influenced by the interviewer’s subjective experience. Reflecting on the interview, the interviewers’ position and the interview situation is paramount. In our case, the two researchers conducting the observations and interviews are long-term members of DNT and have visited many cabins. These researchers discussed and reflected on the interviews, including their own positionality. Further, as we used different data sources (interviews, observations, survey and document studies), we may ensure a higher robustness of our results.

Perceived threats to the DNT system were addressed in the interviews, and document studies. We did not interview foreign trekkers, which might be a weakness since we address possible threats posed by newcomers and foreigners lacking knowledge of the code of conduct, norms and values. This is somewhat mitigated by using a variety of data sources and interviewing members of DNT Ringerike from other cultural contexts. Further, our survey had a low response rate. Hence, we could only use these results cautiously. Finally, our main focus is on cabins that are unstaffed and practices unfolding in these types of cabins. We have carried out an in-depth case study of one local DNT branch complemented by document studies and interviews with DNT at the national level. The local branch is organised in a similar way as other DNT branches throughout Norway. However, they only have unstaffed cabins with no supply of food. This type of cabin comprises nearly half of all DNT cabins making our study highly representative for the DNT system in general and for unstaffed cabins in particular.

We had one interview with DNT at the national level and three meetings with DNT Ringerike about how DNT’s organisation, the extent of voluntary work, perspectives on guests’ practices and challenges to the system. We made detailed notes in all cases. Our material was sorted according to the main themes given in the interview guide to facilitate analysis of the material and the results.

Results

In the Context section, we have presented the material structures of the DNT system, which are important to the social practice framework, as well as its cultural schemes, interpreted as its values and rules of conduct. In this section, we explore how these values contrast with guests’ practices and expressed values, including those of new trekker groups.

Trekkers’ practices and social norms regulating cabin practices

Daily maintenance of self-service cabins presupposes that guests clean after use, leave trekking boots outside and replenish the firewood. Furthermore, guests are expected to pay for their stay and food taken from cabin stocks. They are informed of their duties in the cabins’ notices (usually in Norwegian and English) and information on websites and in pamphlets. This information underlines trust, where everyone “contributes to the functioning of this unique system” (noticeboard in Storekrakkoia, Vassfaret). Some ignore the rules, but most behave according to expectations, and financial losses are low (personal communication, national-level DNT staff).

Our field visits and interviews revealed that guests have established a code of conduct that slightly diverges from the DNT rules. Although the notices state that guests should wash the floors (vask in Norwegian implies the use of soap and water), they tend to sweep instead. One informant (female, German, age group 30–44) commented,

When I leave the cabin, I tidy it up. If I am the last one to leave, I also sweep the floor.

Many of the rules are a bit loosely defined, and I like that. When I was new in the DNT system, I used to trek with others who knew that and I learned from them.

Overreliance on the rules was vividly described by the poet Herman Wildenvey. In the poem A rule, published in 1935, two guests arrive at a DNT cabin and are surprised to find a dead man hanging from a beam in the ceiling. They cut him down, put him outside and enjoy the evening with good food and a sip of aquavit. When they leave the next morning, they carry the corpse back into the cabin and hang it up where they found it, in strict compliance with the rule that “You must leave the cabin in the same condition as when you arrived.”

Disputes can arise over how the cabin should be left, as entries from the guestbook at Vassfarkoia in Ringerike show:

If you leave the cabin in the condition in which I found it today, you should be ashamed of yourself. I simply do not bother to clean and tidy up after such guests and I am therefore leaving Vassfarkoia cabin in the same condition as it was when I arrived.

We wanted to set a good example for others to follow, so we boiled and washed the towels and dish clothes, replenished the firewood, removed candle wax from the table, replaced the candles, washed the floor and generally did what we consider common decency.

The importance of transferring the DNT cabin tradition to the next generation was mentioned in several in-depth interviews:

I think it is good for children that we share the cabin with others, so they do not become too selfish. Then they have to let other people come close and accept having to share with them. That is what they must learn. (Male, Norwegian, age group 30–44).

Trekkers’ expressed values

A core value of DNT is expressed in the Norwegian word friluftsliv (Varley & Semple, Citation2015). A Danish trekker vividly expressed the idea:

To a small Dane (that is what I feel like up here), the nature is so overwhelming that I frequently have to stop and just let tears pass my smiling lips. (Guestbook, Vikerkoia)

Thanks for these few days in paradise. Perfect snow conditions, bright sunshine and magnificent landscape. (Guestbook, Vassfarkoia)

Wonderful starry sky at night-time. And a small stripe of the northern lights appeared in the distance. (Guestbook, Fønhuskoia)

I appreciate chatting with strangers I meet on the trail; that never happens on the street in town. (Male, Norwegian, age group 60+)

Most DNT cabins are modest, encouraging frugality. The DNT Ringerike cabins adhere to this tradition, except perhaps Fønhuskoia, which is newly built and has a modern look (but without electricity or tap water). In contrast, Vikerkoia is a modest cabin, built before World War II. Although Fønhuskoia has more visitors, Vikerkoia is praised in the guestbook:

The cabin is warm and cosy. (Guestbook, Vikerkoia)

What a great cabin! 3–4 lovely Easter days at the well-equipped and cosyFootnote2 Vikerkoia. (Guestbook, Vikerkoia)

New trekker groups and challenges to the DNT system

Our results pinpoint some challenges facing the DNT system. Historically, DNT members were mostly urban and upper middle class, nicknamed nikkersadelen (knickerbocker gentry) because of their outfits. Today, they are transforming into a “Gore-Tex gentry.” One of our older interviewees (male, Norwegian, age group 60+) expressed surprise to see a growing number of trekkers in pleasant Norwegian landscapes wearing equipment suited for Antarctic expeditions. He partly blamed the DNT bulletin for this, as it advertises expensive jackets, boots and rucksacks. While he realised that DNT appreciates the advertising revenue, he felt that, to follow the cultural assumptions of equality and frugality, it should avoid advertising expensive equipment. However, DNT also promotes the use of second-hand equipment and arranges swap markets. We participated in such a market arranged by DNT Ringerike during the study.

Norwegians have traditionally been the dominant users of the DNT system; however, foreigners are discovering its benefits. Statistics for the staffed cabins show that 18 percent of guests are foreign trekkers (personal communication, DNT staff at national level). Trekking in the Norwegian mountains has become so popular that the host of one staffed lodge publicly opposed a planned direct airline route between Oslo and Beijing, claiming that a dramatic increase in guests would leave an environmental footprint that was incongruent with the objective of DNT. Foreign trekkers might be unfamiliar with Norwegian culture and the inherent values on which DNT is based. However, our results show that these trekkers also are capable of transferring the associations of Norwegian landscapes with typical Norwegian myths of trolls and Norse gods, to their own mythological context. Some German visitors borrowed a metaphor from Tolkien’s Lord of the Ring: “Die Orks vervolgten uns über die weiten Felder Rohans” (“the Orcs persecuted us over the vast Rohan plains”) (from guest book, Buvasskoia). This entry in the guest book inspired a later guest to follow suit: “As the Terminator said: I’ll be back!”

A challenge posed by foreign trekkers lies in the distinction between the posted rules and practised conduct. The conduct must be learned through experience and communicating with other guests. Foreign guests who adhere to the rules can still violate what is perceived to be correct conduct. For example, a group of German tourists had booked rooms in advance. In the evening, when all the rooms were occupied, a family with small children arrived. According to the code of conduct, even if they booked in advance, adult visitors should surrender their room to families with children or disabled persons and sleep on mattresses in the sitting room. However, the Germans kept their room and ignored the norm, of which they were probably unaware. The incident was criticised by Norwegian guests in the guestbook. Several similar cases show that foreign guests are not socialised into the conduct on which the system is founded.

Trust lies at the core of the DNT system. One Danish trekker wrote, “The fact that this ‘system’ is based on mutual trust is fantastic. I shall bring it home [to Denmark] and write about it” (guestbook, Vikerkoia). DNT Ringerike expressed concerns that such trust might not survive a large influx of non-members and foreign trekkers, and the system could be misused for commercial purposes. They gave an example of an American yoga teacher using one of their cabins to host yoga classes, neither paying for the visitors nor asking for permission to invite a large group.

The flow of tourists to Lofoten in the north of Norway has created challenges for the local DNT branch. Many tourists use the cabins, but some do not pay or tidy properly after their visits. Consequently, locks with keys that cannot be copied have been installed, making it necessary for all visitors to pick up the key and pay at the local DNT office in advance (NRK Nordland, Citation2019). This shows how visitors might take advantage of the system, in this case, reducing the freedom to use the cabins without having to plan in advance.

Discussion: values, practices and social learning

DNT and their guests: common or divergent values?

From our results, it seems that DNT and many of their guests meet on common ground when it comes to underlying values. A central concept for Norwegian and Scandinavian outdoor recreation is the term friluftsliv, signifying meaningful experiences of nature (Varley & Semple, Citation2015). This is often linked to values of frugality and equality (Flemsæter et al., Citation2015; Høyem, Citation2020; Ween & Abram, Citation2012), which were central for DNT and trekkers in our study. DNT’s cabins are often simple, and the frugal lifestyle the organisation promotes is highly appreciated by guests. As in Kaltenborn and Clout’s (Citation1998) study of second homes in Norway, it is clear that the cabins’ simplicity and the necessary work when visiting are important parts of their appeal.

The freedom of movement in nature, safeguarded by Norway’s Outdoor Recreation Act, allowed many of our informants to escape daily routines. DNT supports such freedom by allowing guests to visit cabins whenever they like and facilitating visits through marked trails. Hence, there is significant overlap between the values that underlie the DNT system and those expressed by our informants in interviews, guestbooks and survey. DNT promotes frugality, equality and freedom of movement, all core parts of the Norwegian national identity (Ween & Abram, Citation2012) and values embraced by guests. Trust is also a core value, and guests are found to be worthy of the trust DNT shows them. As Putnam (Citation2000) argues, shared culture – in our case between DNT and guests, but also evident among Norwegians in general – is an important condition for trust.

Learning through participation in practices

There is a difference between rules and norms in DNT cabins. The conduct is often learned through face-to-face interaction with other visitors, not primarily through the written rules. Wilhite (Citation2014) points to the importance of social learning to explain how practices are sustained and spread. Leaning on Lave (Citation1993), Wilhite (Citation2014) argues, “learning … is a process which involves the acquisition of practical knowledge through a combination of cognitive processes and bodily processes” (p. 27). Participation in practices with peers and learning from their experiences bring social learning, with practices passed on from parents to children and between friends. Based on other studies (Winther & Wilhite, Citation2015), Wilhite (Citation2014) argues that social learning influences people’s decisions on how to act more than does advice or requirements from experts – or in our case, the displayed cabin rules. Our findings show how cabin practices are learned through interactions with friends and family at DNT cabins and transferred from established practices at private cabins. Further, these embodied experiences with peers influence guests’ practices more than the written rules do.

Trust is a hallmark of the DNT system. A key characteristic is the lack of sanctions for flouting the rules. If guests decide to ignore the bill, they can simply leave the cabin without a trace of their visit. Likewise, visitors can leave the cleaning to the next guests. However, there are few free riders. This can be explained via Cialdini et al.’s (Citation1990) notion of descriptive norms: Cabin guests will avoid violating rules even without sanctions. Because moral schemes are internalised in people’s subconsciousness, violating rules could invoke a sense of guilt (Foucault, Citation1980; Pylypa, Citation1998),which is itself the sanction. Without trust, the DNT system guests appreciate would collapse.

Newcomers with different logics

Following social practice theory (Strengers, Citation2013), the main elements conditioning practices are material structures, skills and knowledge, and norms and values. As we have seen in this study, all these factors are important for understanding trekkers’ cabin practices. First, skills about and experience of how the DNT system functions is an important factor influencing the compliance with rules and the code of conduct. These skills are learnt through interactions between cognition and bodily experience related to the material context and influenced by exposure to peers’ practices (Mauss, Citation1936/Citation1973; Wilhite, Citation2014). Our findings show that social learning (Wilhite, Citation2014) is an important mechanism through which knowledge of how to use the DNT system is transferred between members. Further, as we have seen the cultural schemes (values) (Sewell, Citation1992) are largely shared between DNT and its guests easing the operation of the system.

Hence, the logics/modus operandi of the DNT system and guest practices are largely aligned (Strengers, Citation2013; Westskog et al., Citation2011). This may partly explain the system’s success and endurance over more than 150 years.

The logic of a system where the values, skills and knowledge and material contributors overlap with those of the users may evidence a shift in balance when some of the factors constituting social practices change (Strengers, Citation2013; Westskog et al., Citation2011). Guests lacking acquaintance with the system and not being exposed its code of conduct through bodily experience and social learning from peers, may behave according to a different logic threatening the functioning of the system. As pointed out by Frey (Citation1997) and Gneezy and Rustichini (Citation2000), moral motivations for action depend on the logics of a system being shared among its users.

As seen in some places in Norway (e.g. Lofoten), we might expect that such a divergence could threaten the system in several ways. If guests do not clean the cabins, the next guests may think that they should only leave the cabin “as they found it”, and the cabins will be less attractive to visit. If guests do not pay for their visits, the system cannot continue. If stricter rules and new practices need to be introduced, this will increase costs. Without social learning through lived experiences with the system and being taught by peers (Mauss, Citation1936/Citation1973; Wilhite, Citation2014), as well as adherence to the values underlying the system, the conditions supporting the DNT system’s operations will disappear.

Concluding remarks: will the DNT system survive?

In this study, we addressed the conditions supporting the DNT system through a focus on trekkers’ cabin practices. The study was carried out as an in-depth case study of one local DNT branch complemented by document studies and interviews with DNT at the national level. This local DNT branch is organised similarly to most DNT branches and runs cabins which are unstaffed; a cabin type that is the most common in the DNT system and our main focus.

We sought to indicate what factors may challenge the system and its survival. Although the premise of this article is to examine how DNT can retain its current systems in light of new tourism patterns, this is not to say that nothing about the current DNT system warrants critical examination. DNT as an organisation has been criticised for being resistant to change (Nordbø et al., Citation2014). The global challenges of climate change and environmental degradation require all institutions, particularly those working in the tourism field, to examine their operations and make changes toward sustainability. We argue that this should be an underlying principle for any changes to the DNT system. Retaining the emphasis on frugality and meaningful nature experiences which currently underpins DNT’s approach to nature-based tourism, while making this kind of tourism accessible to a wider user group, is in line with this goal.

Our study indicated two main conditions that are paramount for systems like DNT’s to develop. First, there must be overlap between the DNT system’s and guests’ values. As demonstrated, the values constituting friluftsliv, such as frugality, equality, freedom and trust, are crucial to both guests and DNT. Second, the transfer of conduct is essential; norms are communicated via social encounters in real time in real places, bodily experiences and face-to-face interaction between trekkers. Experienced trekkers meet newcomers in cabins and on trails and emblematise appropriate conduct. This result is in line with research on social learning and the importance of face-to-face communication for cooperation in communal activity (Balliet, Citation2010; Ostrom, Citation2000; Wilhite, Citation2014).

DNT and its guests have historically desired a simple, frugal cabin life. This remains the core of the DNT standard. International trends toward nature-based tourism have led to an increased interest in DNT and its services. One could ask whether increased affluence among tourists, both nationally and internationally (Nordbø et al., Citation2014; Tangeland et al., Citation2013), would lead to a demand for more luxury and private cabin use; however, our results are in line with several studies highlighting a rise in demand for “authentic” nature-based experiences (Engeset & Elvekrok, Citation2015; Svarstad, Citation2010; Varley & Semple, Citation2015). This may boost interest in the services of organisations like DNT and secure their continued existence. By promoting core values in information about the system, DNT could attract visitors who share those values and increase the likelihood of following the code of conduct.

Guests lacking familiarity with the DNT system and its code of conduct may still threaten its current structure. It is vital that new members and guests share the system’s core values and interact face to face to ensure social learning of cabin practices. DNT’s guided tours could function as an arena for this. Following Wilhite’s (Citation2014) argument that demonstrations of practices are key for social learning, having mentors to guide newcomers at cabins could be another approach. We argue that the continued existence of DNT’s current system can be ensured by focussing on attracting guests whose values align with DNT’s core values and ensuring that visitors acquire the skills, knowledge and experience to use the facilities in compliance with established norms.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. We would also like to thank all the interviewees for sharing their thoughts with us, the Norwegian Trekking Association for providing information regarding its organisation and DNT Ringerike for providing practical details related to our fieldwork and information regarding its activities and cabins. We are grateful to Karina Standal, Marianne Aasen and Tanja Winther for insightful comments on earlier drafts and our colleagues in the Sharing Economy: Motivations, Barriers and Effects project for their support and valuable input. The work with this paper is funded by the Norwegian Research Council, projects no. 264472 and no. 295704, and Vestregionen whose support is highly appreciated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 There are approximately 450 000 privately owned cabins in Norway (Teigen, Citation2017).

2 Translated here and in the previous quotation from the Norwegian words koselig/hyggelig, denoting a warm and comfortable feeling.

References

- Aamaas, B., & Andrew, R. (2020). Estimating effects on emissions of sharing (Report 2020:03). CICERO.

- Aase, T. H., & Fossåskaret, E. (2014). Skapte virkeligheter. Om produksjon og tolkning av kvalitative data. Scandinavian University Press.

- Abram, S. (2012). “The normal cabin’s revenge”: Building Norwegian (holiday) home cultures. Home Cultures, 9(3), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174212X13414983522071

- Aléx, L., & Hammarström, A. (2008). Shift in power during an interview situation: Methodological reflections inspired by Foucault and Bourdieu. Nursing Inquiry, 15(2), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1800.2008.00398.x

- Andersen, S., & Rolland, C. G. (2018). Educated in friluftsliv – Working in tourism: A study exploring principles of friluftsliv in nature guiding. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18(4), 362–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2018.1522727

- Balliet, D. (2010). Communication and cooperation in social dilemmas: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 54(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002709352443

- Bygdeutvalget. (2008). Vassfaret og brøtningen. Hedalen.no. http://www.hedalen.no/OPPSLAG/2008/april/22/br.pdf

- Cass, N., & Faulconbridge, J. (2016). Commuting practices: New insights into modal shift from theories of social practice. Transport Policy, 45, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2015.08.002

- Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Descriptive social norms as underappreciated sources of social control. Psychometrika, 72(2), 263–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-006-1560-6

- Cialdini, R. B., Kallgren, C. A., & Reno, R. R. (1991). A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 24, pp. 201–234). Academic Press.

- Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(6), 1015–1026. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.1015

- Det Norske Akademis Ordbok. (2020c). Koie. https://www.naob.no/ordbok/koie

- DNT. (2020a). 150 år med Turglede. https://www.dnt.no/historikk/

- DNT. (2020b). Merkede stier og ruter. https://www.dnt.no/ruter/

- DNT. (2020c). Organisasjonen. https://www.dnt.no/organisasjonen/

- DNT. (2020d). Velkommen til våre hytter. https://www.dnt.no/om-hyttene

- DNT. (2020e). Visjon, verdier og strategi. https://www.dnt.no/visjon/

- Elmahdy, Y. M., Haukeland, J. V., & Fredman, P. (2017). Tourism megatrends, a literature review focused on nature-based tourism (MINA Fagrapport #42). MINA, NMBU.

- Engeset, M. G., & Elvekrok, I. (2015). Authentic concepts: Effects on tourist satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 54(4), 456–466. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514522876

- Flemsæter, F., Setten, G., & Brown, K. M. (2015). Morality, mobility and citizenship: Legitimising mobile subjectivities in a contested outdoors. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 64, 342–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.06.017

- Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings 1972–1977. Harvester.

- Fredman, P., & Margaryan, L. (2020). 20 years of Nordic nature-based tourism research: A review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1823247

- Frey, B. S. (1997). Not just for the money. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Garvey, P. (2008). The Norwegian country cabin and functionalism: A tale of two modernities. Social Anthropology, 16(2), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8676.2008.00029.x

- Gneezy, U., & Rustichini, A. (2000). A fine is a price. The Journal of Legal Studies, 29(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1086/468061

- Gullestad, M. (1990). Naturen i norsk kultur. Foreløpige refleksjoner. In T. Deichman-Sørensen & I. Frønes (Eds.), Kulturanalyse (pp. 82–96). Ad Notam Gyldendal.

- Gurholt, K. P. (2008). Norwegian friluftsliv and ideals of becoming an ‘educated man’. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 8(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729670802097619

- Gurholt, K. P., & Haukeland, P. I. (2019). Scandinavian friluftsliv (outdoor life) and the Nordic model: Passions and paradoxes. In M. B. Tin, F. Telseth, J. O. Tangen, & R. Giulianotti (Eds.), The Nordic model and physical culture (pp. 165–181). Routledge.

- Hamar Arbeidsblad. (2012). Helgetur i dronningens skispor. https://www.h-a.no/kultur/reise/helgetur-i-dronningens-skispor

- Høyem, J. (2020). Outdoor recreation and environmentally responsible behavior. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 31, 100317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2020.100317

- Kaltenborn, B. P., & Clout, H. D. (1998). The alternate home – Motives of recreation home use. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography, 52(3), 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291959808552393

- Lave, J. (1993). The practice of learning. In S. Chaiklin & J. Lave (Eds.), Understanding practice: Perspectives on activity and context (pp. 3–32). Cambridge University Press.

- Larimer, M. E., Parker, M., Lostutter, T., Rhew, I., Eakins, D., Lynch, A., & Duran, B. (2020). Perceived descriptive norms for alcohol use among tribal college students: Relation to self-reported alcohol use, consequences, and risk for alcohol use disorder. Addictive Behaviors, 102, 106158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106158

- Lyngø, I. J., & Schiøtz, A. (1993). Tarvelig, men gjestfritt: Den Norske Turistforening gjennom 125 år. DNT.

- Mauss, M. (1973). Techniques of the body. Economy and Society, 2(1), 70–88. (Original work published 1936) https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147300000003

- Ministry of the Environment. (2000–2001). Friluftsliv – Ein veg til høgare livskvalitet (St.meld. nr. 39). Miljøverndepartementet.

- Müller, D. K. (2020). 20 years of Nordic second-home tourism research: A review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1823244

- Myhre, K. K. (2020). COVID-19, dugnad and productive incompleteness: Volunteer labour and crisis loans in Norway. Social Anthropology, 28(2), 326–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8676.12814

- Nordbø, I., Engilbertsson, H. O., & Vale, L. S. R. (2014). Market myopia in the development of hiking destinations: The case of Norwegian DMOs. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 23(4), 380–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2013.827608

- Norwegian Government. (1957). Outdoor recreation act. https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/outdoor-recreation-act/id172932/

- NRK Nordland. (2019). Turlag i Lofoten så seg lei av «hyttesnyltere» og ga opp tillitsordning (NRK Nordland 9 juli 2019). https://www.nrk.no/nordland/turlag-i-lofoten-sa-seg-lei-av-_hyttesnyltere_-og-ga-opp-tillitsordning-1.14620561

- Ostrom, E. (2000). Collective action and the evolution of social norms. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(3), 137–158. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.14.3.137

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster.

- Pylypa, J. (1998). Power and bodily practice: Applying the work of Foucault to an anthropology of the body. Arizona Anthropologist, 13, 21–36.

- Reckwitz, A. (2002). Toward a theory of social practices: A development in culturalist theorizing. European Journal of Social Theory, 5(2), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310222225432

- Rosen, M. (1991). Coming to terms with the field: Understanding and doing organizational ethnography. Journal of Management Studies, 28(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1991.tb00268.x

- Schultz, P. W. (1999). Changing behavior with normative feedback interventions: A field experiment on curbside recycling. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 21(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp2101_3

- Sewell, W. H. (1992). A theory of structure: Duality, agency, and transformation. The American Journal of Sociology, 98(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1086/229967

- Shove, E., Pantzar, M., & Watson, M. (2012). The dynamics of social practice: Everyday life and how it changes. SAGE.

- Shove, E., & Walker, G. (2010). Governing transitions in the sustainability of everyday life. Research Policy, 39(4), 471–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.019

- Simpson, B., & Willer, R. (2015). Beyond altruism: Sociological foundations of cooperation and prosocial behavior. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112242

- Skirbekk, H., & Grimen, H. (2012). Tillit i Norge. Res Publica.

- Spaargaren, G. (2003). Sustainable consumption: A theoretical and environmental policy perspective. Society and Natural Resources, 16(8), 687–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920309192

- Stensland, S., Fossgard, K., Hansen, B. B., Fredman, P., Morken, I.-B., Thyrrestrup, G., & Haukeland, J. V. (2018). Naturbaserte reiselivsbedrifter i Norge. Statusoversikt, resultater og metode fra en nasjonal spørreundersøkelse (MINA Fagrapport No. 52). MINA, NMBU.

- Strengers, Y. (2013). Smart energy technologies in everyday life. Smart utopia? Palgrave Macmillan.

- Svarstad, H. (2010). Why hiking? Rationality and reflexivity within three categories of meaning construction. Journal of Leisure Research, 42(1), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2010.11950196

- Svenska Turistföreningen. (2017). STF – Årsberättelse med hållbarhetsredovisning 2017. https://www.svenskaturistforeningen.se/om-stf/arsberattelser

- Tangeland, T., Aas, Ø., & Odden, A. (2013). The socio-demographic influence on participation in outdoor recreation activities – Implications for the Norwegian domestic market for nature-based tourism. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 13(3), 190–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2013.819171

- Teigen, H. (2017). Frå nytte til den moderne hytte. Syn og Segn, 3, 2017. https://www.synogsegn.no/artiklar/2017/utgåve-3-17/håvard-teigen/

- Varley, P., & Semple, T. (2015). Nordic slow adventure: Explorations in time and nature. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 15(1–2), 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1028142

- Vittersø, G. (2007). Norwegian cabin life in transition. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(3), 266–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250701300223

- Warde, A. (2005). Consumption and theories of practice. Journal of Consumer Culture, 5(2), 131–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540505053090

- Ween, G., & Abram, S. (2012). The Norwegian trekking association: Trekking as constituting the nation. Landscape Research, 37(2), 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2011.651112

- Westskog, H., Winther, T., & Strumse, E. (2011). Addressing fields of rationality – A policy for reducing household energy consumption? In M. A. I. Galarraga, & M. Gonzalez (Eds.), The handbook of sustainable use of energy (pp. 452–469). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Wilhite, H. (2014). Insights from social practice and social learning theory for sustainable energy consumption. Flux, N° 96(2), 24–30. https://doi.org/10.3917/flux.096.0024

- Winther, T. (2008). The impact of electricity. Development, desires and dilemmas. Berghahn Books.

- Winther, T., & Wilhite, H. (2015). An analysis of the household energy rebound effect from a practice perspective: Spatial and temporal dimensions. Energy Efficiency, 8(3), 595–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-014-9311-5

- Wolf-Watz, D., Sandell, K., & Fredman, P. (2011). Environmentalism and tourism preferences: A study of outdoor recreationists in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(2), 190–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2011.583066