ABSTRACT

This study’s purpose is to conceptualise the relationship between resilience and sustainability from a learning perspective. It asks how a community’s first reactions to a crisis can indicate the possible future development of a destination’s sustainability, and examines the resilience properties of elasticity, hysteresis and malleability in relation to single- and multiple-loop learning. Empirically, this study explores public discussions about tourism in northern Norway immediately before, and during the first months of, the COVID-19 crisis. Such discussions are investigated through a qualitative content analysis of articles from the regional newspaper. The findings identify a variety of perspectives among the participants to the discussions reported in the newspaper, including the coexistence of different views on tourism and sustainability and on responses to a crisis. This study frames the discussions in terms of elastic, hysteretic and malleable reactions, and illustrates three learning paths towards alternative weak and strong sustainable futures in a conceptual model. The originality of this study concerns a conceptualisation of the resilience – sustainability relationship as a set of learning paths that emphasises the dynamic and non-deterministic aspects of tourism development, aiming to evoke a sense of both responsibility and empowerment.

Introduction

Public discussions during a crisis that severely affects the tourism sector can indicate the sustainability and the resilience of a community, in general, and in relation to destination development. A crisis’s effect on tourism can reveal the power relations and values underlying destination development (Hall, Citation2003, Citation2010; Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2020; Mair & Reid, Citation2007). These values can relate to different interpretations of sustainability (Davies, Citation2013) and can vary from a position usually associated with weak sustainability, which prioritises the economy, efficiency and effectiveness, to a less anthropocentric and more farsighted position of strong sustainability (Hunter, Citation1997; Morandín-Ahuerma et al., Citation2019). Power relations can determine the different priorities given to the sustainability dimensions represented by the triple-bottom-line (economic benefits, socio-cultural wellbeing, environmental conservation and protection) (Smith & Stirling, Citation2010). Crisis discussions within a community reflect the power relations and values influencing the understanding and practice of sustainability. Such discussions will naturally include comments regarding resilience (i.e. the ability to cope with change, recover from crises and adapt to new circumstances).

The premise of this study was that an investigation of the public discussions in the first stage of a crisis can be particularly useful for uncovering multiple ways of understanding the potentially controversial issues of sustainability and tourism development. The first reactions to a crisis are usually collective shock and a general and overwhelming emotional discomfort, which can lessen existing power relations (Faulkner, Citation2001; Quarantelli & Dynes, Citation1977; Wang, Citation2008). Adopting terminology from the change management literature, this phase can be described as a process of unfreezing and unlearning, through which the forces that tend to maintain the status quo are reshaped in order to face the new situation (Nystrom & Starbuck, Citation1984). The subsequent phase is characterised by knowledge acquisition and diffusion, and by behavioural changes as the implementation of coping and recovery strategies and actions (Wang, Citation2008). In this second phase, different forms and degrees of affiliation between individuals and organisations can occur based on old or new power relations (Prati et al., Citation2012). Thus, it is primarily in the initial period of a crisis, before possibilities for affiliation emerge and different power relations are configured, those different ways of understanding sustainability and tourism can be easily observed.

This study explored public discussions occurring during the initial phase of a crisis from a learning perspective, with the aim of contributing to the conceptualisation of the relationship between sustainability and resilience. Commenting on resilient destinations, some scholars observed that the capacity to learn from changes is essential (Amore et al., Citation2018; Hall et al., Citation2017; Hartman, Citation2018). Learning is among the requirements for truly responsible and sustainable tourism. It implies awareness and information, which are among the requirements for the development of an agenda and the implementation of strategies and actions for sustainable tourism (Mihalič, Citation2016). Focusing on the resilience–sustainability relationship, this study adopted the concepts of elasticity, hysteresis, malleability and single- and multiple-loop learning, asking: how can a community’s first reactions to a crisis indicate the possible future development of a destination’s sustainability? The exploration of this question contributed to the conceptualisation of the resilience–sustainability relationship in terms of learning paths.

This article begins by presenting the concept of resilience and its relationship to that of sustainability. This relationship is then framed with reference to the resilience properties, and their meanings in terms of the different types of learning relevant to sustainability. This theoretical framework was used to investigate the reactions to the COVID-19 crisis in northern Norway. This was done by analysing the articles published in the regional newspaper immediately before, and a few months after, the outbreak. To develop a more comprehensive understanding of the context, triangulation was used and relied on two recent reports relevant to sustainability. This article concludes by highlighting the findings of the case study and the theoretical contributions concerning the resilience–sustainability relationship, together with the study’s limitations and some directions for future research.

Resilience and sustainability

A destination’s resilience is crucially important for its sustainability. Originally used to describe the stability of materials and their resistance to shocks, in recent decades, the concept of resilience has come to denote the ability of a feature (environment, community or ecosystem) to return to its original form (Holling, Citation1973). Since the 1970s, several scholars have applied the resilience concept to tourism from various perspectives, such as adaptive or socio-ecological systems thinking (e.g. Biggs, Citation2011; Butler, Citation2017; Cheer & Lew, Citation2017; Cochrane, Citation2010; Porter & Davoudi, Citation2012). One broadly adopted perspective recognised three main approaches to tourism resilience: an engineering one, focused on the capacity to return to a steady-state; an ecological one, focused on adaptations to a new equilibrium; and a synoptic one, characterised by constant adaptation (Lew, Citation2014). In general, tourism resilience means the capacity of a business, destination or community to adapt, reorganise and evolve as a result of changing circumstances (Dahles & Susilowati, Citation2015; Hall et al., Citation2017; Lew, Citation2014). Resilience is considered a crucial factor for enhancing sustainability in tourism, both at the business and the community level (Sheppard, Citation2022). Amore and colleagues (Citation2018) elaborate a framework according to which destination resilience can be understood as a multi-level web of interactions among tourism and regime actors (government, banks, etc.), resident and non-resident population. Such interactions are relevant not only to resilience but also to a truly inclusive form of sustainability (Amore et al., Citation2018; Hall et al., Citation2017).

Although related, the concepts of resilience and sustainability are distinct. Often, the way sustainability is understood concerns a balance between the economy, socio-cultural wellbeing and the environment (WCED, Citation1987). For instance, this is illustrated in the model proposed by Mihalič (Citation2016), with the three sustainability pillars being the supporting columns of a building representing sustainable tourism. Some scholars have noted that the idea of a balance between different interests is inspired by a normative perspective and does not acknowledge the tensions between the three sustainability dimensions (Cheer & Lew, Citation2017; Lew et al., Citation2016). An example of such tension is the environmental paradox of tourism relying on, but at the same time negatively affecting, the natural environment (Hunter & Green, Citation1995; Williams & Ponsford, Citation2009). According to such a critical position, while resilience concerns change, sustainability is about seeking a stable state.

Some scholars have commented on the distinction between resilience and sustainability, referring to resilience as a necessary condition for sustainability. This position can be found both in the tourism sustainability and risk management literature. Espiner et al. (Citation2017) discussed resilience in tourism as a “buffer” facilitating sustainability. The resilience–sustainability relationship can be visualised as three concentric circles, with the sustainability of a destination in the centre, surrounded by various environmental pressures. Resilience is the intervening circle that absorbs external stresses and supports sustainability. This conceptualisation of resilience is similar to that discussed by Saunders and Becker (Citation2015) in their investigation of risk management. Here, the relationship between the two concepts was illustrated by three concentric circles, with resilience as the intervening circle, representing the “passage” from risk management, focused on short-term solutions to sustainability. The latter is described emphasising long-term adaptability and “future generations” stance. These conceptualisations of the resilience–sustainability relationship suggest that destinations can only be sustainable if they are resilient. However, being resilient neither implies being sustainable nor indicates whether the sustainability towards which a destination is moving is weak or strong.

Some contributions from the tourism literature comment on the link between resilience and sustainability with an emphasis on learning and in relation to the role of local communities. The residents of a tourism destination can occupy various positions and are important stakeholders whose views on sustainability can and should be integrated through the adoption of participatory planning approaches (Amore et al., Citation2018). Several scholars discuss communities and tourism planning in relation to transformational changes towards sustainability and highlight the importance of the communities’ involvement, participation and willingness to learn (e.g. Hall et al., Citation2017; Kato, Citation2018; Šegota et al., Citation2017). With this in mind, the next section describes this study’s theoretical framework concerning resilience and learning for strong/weak sustainability.

Properties of resilience and learning for sustainability

Resilience is inherently linked to learning. Such link is evident in the case of disasters: a community resilience indicates the capacity of its members to face the challenging situation of a crisis, and learn how to adapt (Kato, Citation2018). The link between resilience and learning is also commented on in relation to tourism policies. Policy learning is related by Hall (Citation2011) to single- and multiple-loop learning to indicate different orders of change, from incremental routinised or instrumental changes (single-loop) to conceptual changes and paradigm shifts (multiple-loop) towards sustainability. Similar to such reflections on community resilience and policy development, this study elaborates on resilience and learning. The focus is on the resilience characteristics of elasticity, hysteresis and malleability, and the possibility to link such characteristics to the resilience approaches adopted in tourism (engineering, ecological, synoptic), single- and multiple-loop learning and sustainability. The investigation of such possibility allows to elaborate on resilience and learning as important requirements and premises for sustainable tourism (Espiner et al., Citation2017; Mihalič, Citation2016; Saunders & Becker, Citation2015).

The resilience characteristics – elasticity, hysteresis and malleability (Westman, Citation1978) – can be used to analyse the different responses of a community to disturbances and what implications they may have for learning for sustainability. In the natural sciences, the elasticity of a system refers to the rapidity of its restoration to a stable state after a disturbance. An elastic system is a system that responds to shocks by searching for stability and equilibrium (Westman, Citation1978). Transferred to social sciences, this perspective assumes that resilient social systems bounce back to the initial state they were in before the shock occurred (Saunders & Becker, Citation2015). Elasticity can be related to a type of learning that various scholars, such as educationalist Donald Schön and organisational scholar Chris Argyris, discussed adopting the term single-loop learning (Argyris & Schön, Citation1978; Visser, Citation2007). This type of learning aims to correct errors in routines and do things better by modifying behaviours, sometimes in a fragmented way (Scott & Gough, Citation2003; Sterling, Citation2010).

Single-loop learning, in relation to elasticity, relates to the engineering approach in risk management (Faulkner, Citation2001; Lew, Citation2014; Manyena, Citation2006) and has some limitations in terms of sustainability. Such limitations concern the unnecessary sustainability of the original state to which a system returns and the implicit conflict between the elasticity concept and the idea of sustainability as a journey (NRC, Citation1999; Wals & Rodela, Citation2014). Other criticisms concern the time horizon and fragmentary aspects, since learning that is limited to behavioural responses tends to be episodic and to have a short-term horizon (Simon & Pauchant, Citation2000). This is hardly reconcilable with the future generations thinking of sustainability. It has been noted that the actions deriving from such an approach tend to be minimal and aimed at achieving easy gains (Sidiropoulos, Citation2014; Sterling, Citation2010). Essentially, this is a “business as usual” approach, according to which the post-crisis target is a return to what is perceived as normality. Considering the probability of increasingly frequent acute crises due to climate change and pandemics (Prideaux et al., Citation2020), the single-loop learning paths characterised by elastic reactions can easily lead to unsustainable or very weak sustainable futures.

The characteristics of hysteresis and malleability can be linked to more sustainable learning paths. Hysteresis concerns the degree to which the pattern of recovery is not a reversal of the situation: the after-shock system “retains a memory” of the initial state, but simultaneously accommodates a certain degree of change (Rios et al., Citation2017; Westman, Citation1978). Malleability is the ease with which a system becomes permanently altered (Westman, Citation1978). Both hysteresis and malleability allow systems to adapt to possible shocks and evolve. With regard to destinations, these definitions suggest that hysteresis and malleability can be referred to as learning from past experience and learning to reinvent a destination’s institutions (Holladay & Powell, Citation2013; Keck & Sakdapolrak, Citation2013).

Hysteretic and malleable resilience relates to the multiple-loop learning type (Argyris & Schön, Citation1978; Medema et al., Citation2014). These types of learning focus on “doing better things”, questioning assumptions, learning to learn, and engaging in contextual learning (Sidiropoulos, Citation2014). The latter aspect highlights the social dimension of change towards sustainability (Nguyen et al., Citation2016; Schianetz et al., Citation2007; Tosey et al., Citation2012). Scholars from various disciplines, including tourism, education and organisational studies, have argued that sustainability issues require multiple-loop learning, since this can lead to more radical change and completely new worldviews (Barth & Michelsen, Citation2013; Koutsouris, Citation2009; Medema et al., Citation2014; Siebenhüner & Arnold, Citation2007; Sterling, Citation2010). To indicate the possibility of seeing the world in radically different ways, some scholars have used the term deep learning. This refers to transformational learning and includes cognitive advances and emotional, moral, social and spiritual growth (O’Brien & Sarkis, Citation2014; Sterling, Citation2010). Multiple-loop learning is very relevant to strong sustainability: it is far from “business as usual” thinking and in line with the central role of innovation in sustainability (Prayag, Citation2018). Learning paths characterised by hysteretic and malleable responses to the crisis can lead to sustainable futures.

Methods

To explore how a community’s first reactions to a crisis might indicate the possible future development of a destination’s sustainability, this study investigated the case of northern Norway and the COVID-19 crisis. In this area, there is only one regional newspaper, and this was chosen as the main source of the data for investigating the case. The media plays a central role in framing issues and is an important arena for sense-making in relation to challenging topics and debates (Hellgren et al., Citation2002). As a consequence, media texts can be considered cultural fora (i.e. sites where “current societal debates and representations are played out”; Fürsich, Citation2009, p. 245).

The dataset included 75 articles by journalists and readers from the newspaper section “Northern Norwegian Debate”. This section presents critical perspectives on issues particularly relevant to the region’s communities. The articles were selected using the search words “tourism” and “hospitality” for the period 1 December 2019–31 May 2020. This period began approximately three months before the introduction of the COVID-19 travel restrictions, which coincided with the tourism peak season, and ended at the beginning of the usual off-peak summer season. All articles were included in the dataset: 38 articles were published before the introduction of travel restrictions, and 37 after. shows the type of actors authoring the articles: the most represented categories are residents (with no specific affiliation), politicians and journalists, followed by tourism actors at different levels and academics. It can be noted that such sample includes different types of stakeholders, and, based on the aforementioned considerations about resilience (Amore et al., Citation2018; Hall, Citation2003; Hall et al., Citation2017), this diversity is useful to gain some insights on the variety of the existing perspectives.

Table 1. The affiliation reported on the articles of the dataset.

A discourse analysis of the data was conducted using qualitative content analysis. Different from a critical discourse analysis of the power and knowledge formation, usually emerging in the second phase of a crisis, the performed analysis aimed to unpack the meaning of the ideas expressed by the writers (Gee, Citation2011; Hannam & Knox, Citation2005). This analysis did not aim to quantify the investigated phenomenon, but to interpret it based on the theoretical concepts of resilience and learning. Using NVivo software, codes and subcodes were linked to the texts (Skjott Linneberg & Korsgaard, Citation2019). shows the study’s deductive conceptual approach and three-step text coding process (Mayring, Citation2015; Saldaña, Citation2015).

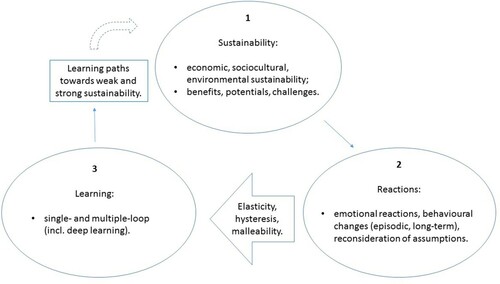

The analysis initially focused on how sustainability in tourism was discussed (circle 1). All the articles were reviewed and the identified themes were coded according to the sustainability dimensions (economic, socio-cultural and environmental) and the related benefits, potentials and challenges. The articles published after the COVID-19 outbreak were coded to indicate the different types of reactions (emotional reactions, behavioural changes and reconsideration of assumptions; circle 2). These articles were also analysed by applying subcodes indicative of the different resilience characteristics (elasticity, hysteresis and malleability) and learning types (single- or multiple-loop; arrow and circle 3). The texts labelled with subcodes were then interpreted in terms of learning paths towards weak and strong sustainability. For example, reactions consisting in discussions about the opportunity to think radically differently were linked to malleability and multiple-loop learning. The dotted-line arrow in illustrates the passage along the learning paths to the future sustainable development of the destination. To continue with the example, multiple-loop learning was linked to strong sustainability in those cases when the observed discussion was in line with a tourism development that considered the sustainability dimensions to a greater extent than what was observed for the pre-crisis phase.

The conducted analysis involved some challenges, since this type of analysis tends to draw upon the researcher’s own knowledge and beliefs about the investigated phenomenon (Hannam & Knox, Citation2005). The subjectivity of the researcher and his/her interpretive position when conducting textual analysis is sometimes regarded as a form of “reading”, rather than an objective investigation of data (Fürsich, Citation2009). Thus, the method’s validity and credibility depend on the reflexivity of the researcher. Another possible limitation of analysing media texts concerns the position of the people authoring these texts – in particular, the accuracy of their representations of the phenomenon discussed and their possible rhetoric supporting specific interests (Philo, Citation2007).

Two strategies were adopted to overcome these limitations. As mentioned, the newspaper section selected as the source of relevant articles included articles authored by different actors (). In addition, two reports were used to triangulate the findings. One report concerned a survey conducted by the DMO and the municipality of the main city in the region, Tromsø (Ryeng, Citation2019). This survey was conducted from October to November 2018 and had 561 respondents. Its main focus was the local community’s perspective on tourism development. The second report was by an architectural studio based on three workshops (April 2020) that focused on young people’s visions of their own and the region’s future (NODA, Citation2020). Both surveys were used to gain a better understanding of the context and how issues relevant to sustainability were discussed in the main regional town and surroundings before the crisis (Ryeng, Citation2019) and during the first weeks of the crisis (NODA, Citation2020).

With regard to reflexivity, the researcher was aware of her critical position regarding the recent increase in tourism and its impact on the natural environment. This was the motivation for the researcher, who is a long-time resident of Tromsø, to respond to the aforementioned 2018 survey and write one of the newspaper articles included in the dataset (marked with an asterisk in the findings section).

Findings

The next sections present the main findings from the articles, which are identified with the publication date. The results from the aforementioned 2018 survey and the 2020 workshops were used to confirm and, sometimes, supplement the data from the newspaper. The presentation of the pre-crisis findings provides the reader with a picture of how sustainability and tourism were discussed before the COVID-19 outbreak: the main themes and their relationship to sustainability, the points of agreement and conflict regarding such themes and the discussed initiatives for improvement. The findings for the first weeks of the crisis are presented according to the changes observable in the public discussions. Such changes are presented in relation to the reactions to the crisis and linked to the resilience characteristics and learning for sustainability. Such discussion was the basis for the development of a model () to illustrate the resilience–sustainability relationship.

The setting: pre-crisis discussions

The findings suggested that the economic and socio-cultural benefits of tourism tended to be discussed in positive terms and included long-term thinking about future generations. The analysis of the articles showed that an understanding of tourism as a means of creating job opportunities in the region was quite widespread (e.g. 06/12, 19/12, 04/03). Tourism job opportunities are sometimes related to the regional challenges typical of peripheral areas. For example, in an article by a local politician, the region was described in terms of “emigration, poverty and depopulation” (03/12). The 2018 survey reported several of the same themes observed in pre-crisis articles about the benefits of tourism: 66% of the respondents considered tourism to be very important, especially for job opportunities, economic development and the stability of the local community (Ryeng, Citation2019). A critical view of the economic benefits of tourism was observed in an article raising concerns about the uneven distribution of the wealth deriving from such activities (05/12).

The newspaper articles showed that the presence of tourists and the resulting changed profile of Tromsø were considered in very different terms. For example, one article presented such change as a welcome shift towards more modern and lively society, with more opportunities for both tourists and residents (25/02). This positive view of tourism was confirmed by some of the results of the 2018 survey, stating that tourism was a source of local pride for 72% of the respondents (Ryeng, Citation2019).

A diametrically opposite perspective was presented by other articles, which expressed concern about the town’s “loss of identity” (21/02) and its “touristification” (06/03). This aspect was also observed in the 2018 survey: 19% of the respondents were very worried about tourism decreasing the local residents’ quality of life (Ryeng, Citation2019). The articles and the report suggested conflicting views regarding areal use. Conflicts between the residents and the tourists were commented on in relation to free camping and litter left close to houses, and unregulated and illegal fishing and hunting (e.g. 05/12, 14/02; Ryeng, Citation2019). One article claimed that the ticket system to access the North Cape plateau area was an “illegal fee” that directly conflicted with the local outdoor lifestyle (21/12). Conflicts about the use of natural areas were evident in two articles commenting on the coexistence of various economic activities (whale watching, fishing and oil exploration) and environmental protection (09/12, 27/01). Some concern about pollution was observed in the results of the 2018 survey, regarding cruises and charter flights (Ryeng, Citation2019), as well as in some articles. For example, a politician asked rhetorically: “Is it right that we encourage tourists from far away to come and contribute to aviation emissions?” (22/02).

shows the identified themes, highlighting the discussed benefits, potentials and compatibility between the sustainability dimensions (WCED, Citation1987) and also the challenges and conflicts. The table presents in italics the initiatives reported in the articles as possible practical actions for improvement. These were quite similar to the initiatives identified by the 2018 survey: better infrastructure and transport systems, broader and better cultural offerings, the development of new products and attractions, greater collaboration between sectors and a marked green profile (Ryeng, Citation2019).

Table 2. Themes and initiatives were discussed in the articles before the COVID-19 crisis.

Reactions to the crisis and new themes of discussion

In accordance with the crisis management literature, the initial reaction of the community to the COVID-19 outbreak could best be described as a shock (Faulkner, Citation2001; Quarantelli & Dynes, Citation1977; Wang, Citation2008; Westman, Citation1978). Some examples of expressions and terms indicative of such emotional reactions were: “very frustrating” (10/03), “scary” (12/03), “this is a cruel—and undesirable—shock therapy for the region” (12/04) and “the whole tourism industry’s back has been broken” (26/03). Some articles suggested that the region is considered particularly vulnerable because of its small population, high numbers of elderly people, and limited health infrastructure (e.g. 03/20, 14/03). In contrast to the pre-crisis situation, the themes concerning tourism as a way to revitalise the region were presented in quite dramatic terms (e.g. 25/04): unemployment, lay-offs and entrepreneurs losing their businesses were the focus of several articles (e.g. 27/03, 10/03). Initiatives reported in relation to this shocking aspect were episodic changes (Simon & Pauchant, Citation2000): recovery strategies and financial help given by the state (e.g. 26/03, 10/03). This type of reaction does not show neither a felt need nor an intention to change tourism when, eventually, the crisis will be over. Thus, these reactions can be qualified as elastic and indicative of linear learning, consisting of minor adjustments in the view of going back to a situation similar to the pre-crisis situation.

Three new themes emerged from the analysis of the articles during the first weeks of the crisis. One was criticism of public authorities concerning some decisions that affected the local community’s safety. An example is the presence of some tourists in the region (14/03). The other new themes concerned the rights of the Sami reindeer herders and the possibility of rethinking tourism. These new themes were partly triggered by the COVID-19 crisis and partly by a ski resort project, the formal processing of which coincided with the first months of the COVID-19 crisis. The articles about this project showed a heated debate. In some articles (e.g. 25/04a, 27/04), a “doing things better” approach was noted. This concerns the construction of the ski resort as a means to establish a more lucrative local tourism sector, which could create job opportunities and enhance welfare. These reactions can be described as referring to hysteretic resilience and can be interpreted in terms of single-loop learning towards a renewed but not radically different tourism. Other articles were more critical of the ski resort project. This is evident in some reactions that can be considered as the premises for a multiple-loop learning path originated by on a fundamental dissent about the mainstream tourism tendency. For example, one article (20/04) commented on the recreational and economic opportunities offered by the pristine nature compared to the type of experiences offered by the planned ski resort, which were considered old-fashioned and not particularly suitable for the local context.

The new theme concerning the traditional uses of the local natural areas by Sami reindeer herders mainly related to the ski resort project (e.g. 25/04, 27/04). These articles tended to be very critical. For example, one article listed and commented on the challenges as follows: “traffic challenges, reindeer grazing, carbon storage, and Sami interests are (…) among the topics ‘pushed under the rug’ and ignored by this strong group of powerful people in Tromsø” (21/05).

With regard to the new theme about the possibility of rethinking tourism, considerations mainly related to criticism of mass tourism and tourist mobility (e.g. 14/04, 01/04). For instance, one article read: “We must decide which tourists we want and what exclusive experiences we will create. Perhaps the management of the coronavirus crisis currently facing the industry will shed light on these challenges?” (26/05). With regard to possible initiatives and improvements, one article mentioned the possibility of building a modern, low-carbon railway network to attract tourists who were willing to pay, suggesting a reconciliation of the economic and environmental dimensions of sustainability (31/03*). These reactions reflected the unfreezing and unlearning processes described in the change management literature (Nystrom & Starbuck, Citation1984). For example, the aforementioned quotations suggested that some community members were critical of mass tourism. This could indicate a “doing better things” approach to tourism development and multiple-loop learning pointing towards a more sustainable future achievable through innovation (Medema et al., Citation2014; Prayag, Citation2018; Sidiropoulos, Citation2014).

Signs of an understanding of strong sustainability were evident in some articles. Comments about reconsidering the values underlying the growth of tourism, in the regional context and globally, related to the crisis as an opportunity to radically change the sector. For example, one article read:

We have allowed companies to ravage nature in many parts of the world for financial gain, and we have even contributed frequent flights to exotic destinations. We have chosen economic growth based on ever-increasing consumption, rather than saving the globe, our common foundation of life. (12/04)

One article argued that the discussions about tourism growth (in particular, the ski resort project) tended to “be based on ‘money talks’, neglecting the fact that nature that can’t talk for itself” (14/04). These comments reflected an alternative worldview (Barth & Michelsen, Citation2013; Davies, Citation2013; Hunter, Citation1997; Medema et al., Citation2014; Morandín-Ahuerma et al., Citation2019; Siebenhüner & Arnold, Citation2007; Sterling, Citation2010).

reports the new themes and initiatives (in italics) that arose from the discussions about tourism during the crisis.

Table 3. New themes and initiatives discussed during the COVID-19 crisis.

Before describing a model for conceptualising the relationship between resilience and sustainability based on the findings, it is worth noting that several discussions during the crisis were provoked by the ski resort project rather than the crisis itself. Presumably, the crisis helped to create an arena in which alternative views were made more explicit. This can be commented on referring to the crisis management literature, and in particular, the different perceptions of crises and the extent to which they are caused by humans (e.g. Quarantelli & Dynes, Citation1977). This article proposes that the COVID-19 crisis was eventually perceived by the local community as inevitable, while the numerous conflicting perspectives regarding alternative areal uses were associated with a situation that some people believed could, and in their opinion should, be changed.

The resilience–sustainability model

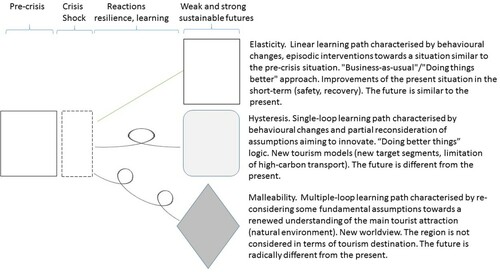

shows a model of the resilience–sustainability relationship as a set of learning paths towards possible weak and strong sustainable futures. The text on the right of the figure reports some examples from the investigated case.

The white square on the left of represents the pre-crisis situation. In the investigated case, the pre-crisis situation was characterised by a marked anthropocentric approach. On the one hand, the findings showed some compatibility between economic and socio-cultural sustainability; on the other hand, the discussions about the environment were limited to a recognition of tourism leveraging the attractiveness of the natural landscape, with no identification of possible benefits for the natural environment deriving from tourism. This can be interpreted as a sign of weak sustainability (Morandín-Ahuerma et al., Citation2019).

The white square with the dotted-line represents the shock reactions to the crisis (Faulkner, Citation2001; Nystrom & Starbuck, Citation1984; Wang, Citation2008), which are known to delay other types of reactions. The three lines departing from the shock phase lead to alternative futures, indicated with white and two shades of grey to indicate weak and strong sustainability. These paths are illustrated with lines that differ according to the type of learning involved and are characterised by reactions and initiatives such as those reported in the text (on the right) regarding the investigated case. The first path is characterised by elasticity: it includes behavioural episodic changes that aim to respond to the crisis with initiatives for community safety and recovery. There is no focus on goals that could lead to a future different from the pre-crisis situation.

The second path is a single-loop learning path. It is characterised by hysteretic reactions that reconsider assumptions, such as the desirability of mass tourism and the possibility of developing target-specific market segments through innovation. Multiple-loop learning characterises the third path. Here, the assumptions that are reconsidered are epistemic and involve worldviews that can be related to strong sustainability. An example is a view of nature as a stakeholder with interests that may conflict with those of the local community and humanity as a whole. This third future is illustrated with a different shape to indicate malleability, which is the resilience property concerning systems becoming permanently altered.

The conceptualisation of the resilience–sustainability relationship presented in this model goes beyond the idea of resilience being a necessary condition for sustainability: a “buffer” or a “passage” (Espiner et al., Citation2017; Saunders & Becker, Citation2015). It highlights the role of single- and multiple-loop learning in the resilience concept, adopting the ideas of elasticity, hysteresis and malleability, and links them to weak and strong sustainability as possible alternative futures. As such, it elaborates further on the conceptualisation of awareness and information as requirements for truly responsible and sustainable tourism (Mihalič, Citation2016). More precisely, it emphasises the processual aspect of awareness and information acquisition, and proposes to consider the requirement of learning in dynamic terms, conceptualised as a path. This adds a flexibility dimension to the model of sustainable development proposed by (Mihalič, Citation2016). In addition to further describing the relationship between resilience and sustainability, this model can contribute to raising awareness of the possibility of influencing the future and provoke a sense of both responsibility and empowerment that, eventually, may lead to change.

Conclusions

This study asked how a community’s first reactions to a crisis can indicate the possible future development of a destination’s sustainability. It investigated the case of public tourism-related discussions immediately before and after the COVID-19 outbreak in northern Norway. These discussions were related to the sustainability dimensions, resilience properties and to learning. The findings of the empirical case relative to the pre-crisis discussions showed the coexistence of various perspectives on sustainability and tourism development. The findings concerning the discussions after the COVID-19 outbreak showed some new themes and signs of different types of resilience and learning, which related to weak and, to a lesser extent, strong sustainability. The findings suggested that some of the more critical perspectives on tourism growth were not triggered by the crisis. Presumably, the crisis, although not the main cause of such reflections, contributed to making them more visible, since it created an arena where alternative views could be aired. The crisis, directly and indirectly, therefore revealed both explicit and latent themes, which pointed out multiple ways of understanding sustainable tourism and different paths to alternative futures. This confirms the revealing power of crises commented on by some authors (e.g. Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2020), and highlights the importance of creating arenas where different perspectives on tourism and sustainability can be discussed.

Theoretically, this study argues that the oft-cited journey towards sustainability can be better conceptualised as a set of journeys. Focusing on the community level and viewing such journeys as learning paths has the advantage of placing the focus on the learning processes necessary for understanding and framing issues relevant to the future of destinations. The conceptualisation of the relationship between resilience and sustainability, as a set of alternative paths relying on different learning processes, goes beyond the view of resilience as a necessary condition for sustainability – a “buffer” or “passage”, as presented by Espiner et al. (Citation2017) and Saunders and Becker (Citation2015). It is similar to the considerations about the different orders of change in policy development for sustainability discussed by Hall (Citation2011). Differently from the latter, this study focused on the community members participating in the public debate, regardless of their belonging to organisations responsible for policy development. Also, it focused on the identification of the observable intermediate phases (behavioural changes and critical reviews of assumptions) preceding different types of sustainability (weak/strong). Ideologically, considering sustainability as a set of journeys towards alternative futures may be important for provoking reflections on today’s societal responsibility and empowering change-minded people to act.

To overcome possible limitations of the text analysis, this study triangulated the findings with two reports and made the researcher’s position explicit. Nevertheless, some limitations must be noted and can constitute the basis for future studies. This study was limited by the analysis of discussions presented only in the articles available in one section of the regional newspaper and by the performance of qualitative content analysis. Although the newspaper section in which the articles were published is open to submissions by all readers, it is realistic to suppose that not all submitted papers are published, and this, more or less consciously, might depend on the newspaper’s perspective on the specific topics. Another reason is the potential challenge of communicating in a publishable written form. To gain a broader and deeper understanding of tourism-related discussions, further studies could investigate comments from the posts reported in the online versions of the articles, and consider local newspapers, including the one in the Sami language, and the more accessible “letters from readers” sections. With such a broader database, a critical discourse analysis could be performed to capture possible power mechanisms and relations that might affect sustainability-related decisions about the future of the region. Future studies might also benefit from a research team that includes individuals with different perspectives on sustainability and tourism development, as such diversity might improve the analysis and interpretation of the texts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Amore, A., Prayag, G., & Hall, C. M. (2018). Conceptualizing destination resilience from a multilevel perspective. Tourism Review International, 22(3–4), 235–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3727/154427218X15369305779010

- Argyris, C., & Schön, D. A. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Addison-Wesley.

- Barth, M., & Michelsen, G. (2013). Learning for change: An educational contribution to sustainability science. Sustainability Science, 8(1), 103–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-012-0181-5

- Biggs, D. (2011). Understanding resilience in a vulnerable industry: The case of reef tourism in Australia. Ecology and Society, 16(1), 30–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03948-160130

- Butler, R. W. (2017). Tourism and resilience. CABI.

- Cheer, J. M., & Lew, A. A. (2017). Sustainable tourism development: Towards resilience in tourism. Interaction, 45(1), 10–15.

- Cochrane, J. (2010). The sphere of tourism resilience. Tourism Recreation Research, 35(2), 173–185. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2010.11081632

- Dahles, H., & Susilowati, T. P. (2015). Business resilience in times of growth and crisis. Annals of Tourism Research, 51, 34–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.01.002

- Davies, G. R. (2013). Appraising weak and strong sustainability: Searching for a middle ground. Consilience, 10(1), 111–124.

- Espiner, S., Orchiston, C., & Higham, J. (2017). Resilience and sustainability: A complementary relationship? Towards a practical conceptual model for the sustainability–resilience nexus in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(10), 1385–1400. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1281929

- Faulkner, B. (2001). Towards a framework for tourism disaster management. Tourism Management, 22(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00048-0

- Fürsich, E. (2009). In defence of textual analysis. Journalism Studies, 10(2), 238–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700802374050

- Gee, J. P. (2011). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method. Routledge.

- Hall, C. M. (2003). Politics and place: An analysis of power in tourism communities. In S. Singh, D. J. Timothy, & R. K. Dowling (Eds.), Tourism in destination communities (pp. 99–114). CABI.

- Hall, C. M. (2010). Politics and tourism: Interdependency and implications in understanding change. In R. W. Butler & W. Suntikul (Eds.), Tourism and political change (pp. 7–18). Goodfellow.

- Hall, C. M. (2011). Policy learning and policy failure in sustainable tourism governance: From first- and second-order to third-order change? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4–5), 649–671. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.555555

- Hall, C. M., Prayag, G., & Amore, A. (2017). Tourism and resilience. Channel View.

- Hannam, K., & Knox, D. (2005). Discourse analysis in tourism research a critical perspective. Tourism Recreation Research, 30(2), 23–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2005.11081470

- Hartman, S. (2018). Resilient tourism destinations? In E. Innerhofer, M. Fontanari, & H. Pechlaner (Eds.), Destination resilience – challenges and opportunities for destination management and governance (pp. 66–75). Routledge.

- Hellgren, B., Löwstedt, J., Puttonen, L., Tienari, J., Vaara, E., & Werr, A. (2002). How issues become (re)constructed in the media: Discursive practices in the AstraZeneca merger. British Journal of Management, 13(2), 123–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00227

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2020). Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 610–623. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757748

- Holladay, P. J., & Powell, R. B. (2013). Resident perceptions of social–ecological resilience and the sustainability of community-based tourism development in the commonwealth of Dominica. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(8), 1188–1211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.776059

- Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 4(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245

- Hunter, C. (1997). Sustainable tourism as an adaptive paradigm. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(4), 850–867. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(97)00036-4

- Hunter, C., & Green, H. (1995). Tourism and the environment: A sustainable relationship? Routledge.

- Kato, K. (2018). Debating sustainability in tourism development: Resilience, traditional knowledge and community: A post-disaster perspective. Tourism Planning & Development, 15(1), 55–67. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2017.1312508

- Keck, M., & Sakdapolrak, P. (2013). What is social resilience? Lessons learned and ways forward. Erdkunde, 67(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3112/erdkunde.2013.01.02

- Koutsouris, A. (2009). Social learning and sustainable tourism development; local quality conventions in tourism: A Greek case study. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17(5), 567–581. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580902855810

- Lew, A. A. (2014). Scale, change and resilience in community tourism planning. Tourism Geographies, 16(1), 14–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2013.864325

- Lew, A. A., Ng, P. T., Ni, C. C., & Wu, T. C. (2016). Community sustainability and resilience: Similarities, differences and indicators. Tourism Geographies, 18(1), 18–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2015.1122664

- Mair, H., & Reid, D. (2007). Tourism and community development vs. tourism for community development: Conceptualizing planning as power, knowledge, and control. Leisure/Loisir, 31(2), 403–425. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2007.9651389

- Manyena, S. B. (2006). The concept of resilience revisited. Disasters, 30(4), 434–450. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0361-3666.2006.00331.x

- Mayring, P. (2015). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical background and procedures. In A. Bikner-Ahsbahs, C. Knipping, & N. Presmeg (Eds.), Approaches to qualitative research in mathematics education (pp. 365–380). Springer.

- Medema, W., Wals, A., & Adamowski, J. (2014). Multi-loop social learning for sustainable land and water governance: Towards a research agenda on the potential of virtual learning platforms. NJAS: Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 69(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2014.03.003

- Mihalič, T. (2016). Sustainable-responsible tourism discourse – towards ‘responsustable’ tourism. Journal of Cleaner Production, 111(PartB), 461–470. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.12.062

- Morandín-Ahuerma, I., Contreras-Hernández, A., Ayala-Ortiz, D. A., & Pérez-Maqueo, O. (2019). Socio–ecosystemic sustainability. Sustainability, 11(12), 3354. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123354

- National Research Council (NRC). (1999). Our common journey: A transition toward sustainability. Ekistics; Reviews. on the Problems and Science of Human Settlements, 66(1), 82–101.

- Nguyen, D., Imamura, F., & Iuchi, K. (2016). Disaster management in coastal tourism destinations: The case for transactive planning and social learning. International Review for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development, 4(2), 3–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14246/irspsd.4.2_3

- NODA (Nord Norsk Design- og Arkitetktursenter). (2020). Nye stemmer: en perspektivmelding fra landsdelesn unge voksne [New voices: a message from the young adults of the region]. Intern report.

- Nystrom, P. C., & Starbuck, W. (1984). To avoid organizational crises, unlearn. Organizational Dynamics, 12(4), 53–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2708289

- O’Brien, W., & Sarkis, J. (2014). The potential of community-based sustainability projects for deep learning initiatives. Journal of Cleaner Production, 62, 48–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.07.001

- Philo, G. (2007). Can discourse analysis successfully explain the content of media and journalistic practice?. Journalism Studies, 8(2), 175–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700601148804

- Porter, L., & Davoudi, S. (2012). The politics of resilience for planning: A cautionary note. Planning Theory & Practice, 13(2), 329–333.

- Prati, G., Catufi, V., & Pietrantoni, L. (2012). Emotional and behavioural reactions to tremors of the Umbria-Marche earthquake. Disasters, 36(3), 439–451. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7717.2011.01264.x

- Prayag, G. (2018). Symbiotic relationship or not? Understanding resilience and crisis management in tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 25, 133–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.11.012

- Prideaux, B., Thompson, M., & Pabel, A. (2020). Lessons from COVID-19 can prepare global tourism for the economic transformation needed to combat climate change. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 667–678. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1762117

- Quarantelli, E. L., & Dynes, R. (1977). Response to social crisis and disaster. Annual Review of Sociology, 3(1), 23–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.03.080177.000323

- Rios, L. A., Rachinskii, D., & Cross, R. (2017). A model of hysteresis arising from social interaction within a firm. Journal of Physics: IOP: Conference Series, 811(1), 012011. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/811/1/012011

- Ryeng, A. (2019). Innbyggerundersøkelsen [Residents’ survey] 2469 Reiselivsutivkling. Intern report.

- Saldaña, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage.

- Saunders, W. S. A., & Becker, J. S. (2015). A discussion of resilience and sustainability: Land use planning recovery from the Canterbury earthquake sequence, New Zealand. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 14(1), 73–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.01.013

- Schianetz, K., Kavanagh, L., & Lockington, D. (2007). The learning tourism destination: The potential of a learning organisation approach for improving the sustainability of tourism destinations. Tourism Management, 28(6), 1485–1496. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.01.012

- Scott, W., & Gough, S. (2003). Rethinking relationships between education and capacity-building: Remodelling the learning process. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 2(4), 213–220. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15330150390241409

- Šegota, T., Mihalič, T., & Kuščer, K. (2017). The impact of residents’ informedness and involvement on their perceptions of tourism impacts: The case of Bled. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6(3), 196–206. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.03.007

- Sheppard, V. (2022). Linking resilience thinking and sustainability pillars to ecotourism principles. In D. A. Fennell (Ed.), Routledge handbook of ecotourism (pp. 53–69). Routledge.

- Sidiropoulos, E. (2014). Education for sustainability in business education programs: A question of value. Journal of Cleaner Production, 85, 472–487. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.10.040

- Siebenhüner, B., & Arnold, M. (2007). Organizational learning to manage sustainable development. Business Strategy and the Environment, 16(5), 339–353. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.579

- Simon, L., & Pauchant, T. C. (2000). Developing the three levels of learning in crisis management: A case study of the Hagersville tire fire. Review of Business-Saint Johns University, 21(3), 6–11.

- Skjott Linneberg, M., & Korsgaard, S. (2019). Coding qualitative data: A synthesis guiding the novice. Qualitative Research Journal, 19(3), 259–270. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-12-2018-0012

- Smith, A., & Stirling, A. (2010). The politics of social-ecological resilience and sustainable socio-technical transitions. Ecology and Society, 15(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03218-150111

- Sterling, S. (2010). Learning for resilience, or the resilient learner? Towards a necessary reconciliation in a paradigm of sustainable education Environmental Education Research, 16(5-6), 511–528. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2010.505427

- Tosey, P., Visser, M., & Saunders, M. N. (2012). The origins and conceptualizations of ‘triple-loop’ learning: A critical review. Management Learning, 43(3), 291–307. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507611426239

- Visser, M. (2007). Deutero-learning in organizations: A review and a reformulation. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 659–667. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.24351883

- Wals, A. E., & Rodela, R. (2014). Social learning towards sustainability: Problematic, perspectives and promise. NJAS: Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 69(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2014.04.001

- Wang, J. (2008). Developing organizational learning capacity in crisis management. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 10(3), 425–445. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422308316464

- Westman, W. E. (1978). Measuring the inertia and resilience of ecosystems. BioScience, 28(11), 705–710. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1307321

- Williams, P. W., & Ponsford, I. F. (2009). Confronting tourism’s environmental paradox: Transitioning for sustainable tourism. Futures, 41(6), 396–404. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2008.11.019

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). (1987). Our common future. Oxford University Press.